ABSTRACT

The value of experienced headteachers’ acquired knowledge has been highlighted by both practitioners and within the academic literature. Very few empirical studies, however, address headteachers’ professional knowledge concerning their schools as organizations. This article engages with this research gap by examining school leaders’ declarative and informal knowledge of primary school organizations, and how these might assist in efforts to improve aspects of professional culture in education. The article draws from a wider mixed methods project, in partnership with a local council and network of schools in England, drawing on qualitative data from interviews with 10 career headteachers selected for their record of school turnaround, mentoring responsibilities with other headteachers, or exemplary record of forming professional cultures. The article analyses how these headteachers articulated their conceptions of the primary school environment and communicated an understanding of their role in forming effective organizations. The article discusses how headteachers’ organizational knowledge might best be considered. It presents a framework of five thematic categories through which to conceptualize this knowledge in terms of orientation toward organizational structures and professional relationships.

Introduction

When considering the elementary school as an organization – defined as ‘a group of people who work together in an organized way for a shared purpose’ (Cambridge Dictionary, Citationn.d.) – several tensions and dilemmas immediately present themselves. The problem invites us to consider the needs, actions, and interactions of individuals within this professional network, the resulting impact on their ability to carry out their respective roles, and the degree of collective success of the institution in fulfilling its stated purpose. Multiple groups of people – including parents, staff, teaching assistants, the children themselves, and external partners – may be considered as part of the organization, working together to achieve the various outcomes that a school may strive for. The question of how we should conceptualize schools as organizations, therefore, is a complex one with multiple facets and elements of consideration. It is also a question with real-world implications for headteachers, such as how they may best direct their time, and how training of new leaders might be improved.

In the United Kingdom, practicing headteachers have critiqued the existing training in this regard as ‘held in stasis by a research gap’ (Sparkes & Thompson, Citation2020, p. 100). Day et al. (Citation2000) have put forth the view that previous research has largely focused on raising pupil standards, rather than examining school leaders’ behavioral effects on the school as an organization of adults working toward a common goal, whether formally employed, voluntary, or involved through association. Studies considering schools through the lens of organizational theory have highlighted the role of ideological conflicts and differing interpretations of the multiple tasks, goals, and theories of childhood that surface while working in education, alongside conceiving of the school itself as an intricately structured and complex organization (Berg & Wallin, Citation1982). Applying such a theory to the educational setting invites exploration of these elements as they relate to teacher professionalism, staff wellbeing, and the organizational knowledge gained by headteachers over the course of their careers, as well as the impact of this knowledge on leaders’ behavior. Such an approach, which emphasizes the strength of relationships within the school organization, draws from conceiving of the headteacher as an actor within a network (see Latour, Citation1988); it is concerned more with tracing what such actors mobilize, rather than the leaders themselves or their followers (Grint, Citation1997). Thus, the focus lies with the professional culture itself rather than individuals within it, and on the degree to which organizations achieve a level of efficacy as a function of staff fulfillment and the minimizing of conflicts, both ideological and logistical.

Existing findings relating to school climate confirm its wide-ranging impact not only to staff, but also to students. Not only have findings linked positive school climates to student achievement (Bossert, Citation1988; Brookover et al., Citation1978; Hoy et al., Citation1990, Citation1991, Citation1996; Jarl et al., Citation2021; MacNeil et al., Citation2009; Moos, Citation1979), but have also directly related student satisfaction to schools where relationships are perceived as high-quality, or the site is seen as one of psychological safety (Baker, Citation1998; Baker et al., Citation2003). Furthermore, schools with dynamic, open and healthy climates inspire greater commitment from staff (Hoy et al., Citation1990, Citation1991; Tarter et al., Citation1989), and facilitate the professional development of newly qualified teachers (Flores, Citation2004; Williams et al., Citation2001).

What, then, might constitute key knowledge for the effective leadership of elementary school organizations? The project that this article draws data from, Organizational Health in the Primary School: A Framework for New Headteachers, aimed to elicit and codify the acquired professional knowledge of experienced headteachers regarding their schools as organizations. It examined some of the gaps in our understanding of elementary schools as understood through the lens of organizational theory, offering perspective on how we may begin to understand schools as professional environments. This may inform efforts to cultivate a sense of what matters within such organizations, to attend to them more effectively and with a greater sense of purpose. The starting point for this endeavor is the consultation of school leadership experts on their professional knowledge of elementary schools as organizations, and to codify their responses. This article reports findings relating to the question of what declarative and informal knowledge these leaders have of their schools’ professional cultures.

Conceptual framework

Barker and Rees (Citation2020) have argued for research efforts to comprehensively codify the knowledge acquired and developed by school leaders. Yet answers to the question of what kinds of professional knowledge headteachers develop over the course of their careers may be informed by a number of theoretical frameworks, which may be of greater or lesser appropriacy depending on the lens used by researchers. Where headteacher knowledge is concerned, three conceptual scaffolds are of potential relevance.

Managerial knowledge

In the United Kingdom, periods of extensive policy reform have resulted in headteachers’ adoption of a strategic and institutional pragmatism, and prevailing views increasingly conceptualize the headteacher role as a managerial one (Moore et al., Citation2002). With increasing scrutiny of performance metrics and high-stakes accountability measures in place, it is common to find an emphasis in headteacher training on risk management, safeguarding, legal pitfalls and knowledge of human resources (Holligan et al., Citation2007). Yet it remains unclear what, in practice, the managerial responsibility for the functioning of a school system entails, an aspect that has been relatively under-explored in educational organization theory (Connolly et al., Citation2019); the focus more typically lies with the accountability of individuals for the functioning of the particular system for which they are responsible (Ball, Citation2008; Moeller, Citation2008).

Pedagogical and curriculum knowledge

Developing knowledge of learning, both as it relates to particular subjects (content knowledge), of effective teaching (pedagogical knowledge) and of effective teaching within particular subjects (pedagogical content knowledge, or PCK), has been a powerful vector for school improvement in recent years (see, for example, Gaffney & Faragher, Citation2010; Magnusson et al., Citation1999; Myhill et al., Citation2021; Shulman, Citation1986). For headteachers, the development of such knowledge enables effective coaching of individual staff members and enhances the training of the body of professionals as a whole (Timperley, Citation2011). Furthermore, it furnishes professional teams with a language and conceptual framework through which to improve teaching and learning.

Stein and Nelson (Citation2003) have applied this framework to the work of headteachers, positing the construct of ‘leadership content knowledge’ relating to how pupils learn and knowledge of the curriculum. Others have sought to develop a literature on the practice of instructional leadership, and may focus on headteachers’ ability to inspire a greater focus on the ‘craft’ of teaching. Despite drawing on a tradition of research and thinking in the area, the focus on leadership of and for learning is a relatively new area of scholarship (Timperley & Robertson, Citation2011). Both aforementioned frameworks ultimately have limited application to the corresponding professional knowledge of career headteachers, however, and fall short of providing an appropriate taxonomy for the knowledge relating to leaders’ approach to forming professional cultures.

Organizational knowledge

The final conceptual framework relates to highly specialized knowledge, acquired over time and unique to experts. It necessitates an inductive approach to data collection from an appropriate sample of experienced headteachers. Broad knowledge types, such as the distinction between declarative and procedural knowledge, have received focus from cognitive scientists since the 1970s (Anderson, Citation1980). In the domain of school leadership research, however, the type of declarative or procedural knowledge required is often generic and rarely specified, with the most comprehensive research relating to pedagogical knowledge (Timperley, Citation2011) rather than knowledge of schools as organizations (Lock, Citation2020; Sparkes & Thompson, Citation2020). Arts et al. (Citation2006) suggest that professionals gain such expert organizational knowledge after more than 10 years of specialized experience, highlighting the requirement for a targeted approach to capture this knowledge.

A design that attends to the expert knowledge of experienced headteachers’ knowledge of organizational culture thus constitutes a powerful opportunity to address this gap. One useful framework outlines types of expert knowledge as falling into five main categories (Bereiter & Scardamalia, Citation1993), here adapted for the domain of school organizational theory in .

Table 1. Types of expert knowledge (adapted from Bereiter & Scardamalia, Citation1993).

The qualitative data that this article draws from offered numerous examples of these five overlapping types of expert knowledge relating to headteachers’ approaches. The value of school leaders’ informal workplace learning has been highlighted both by headteachers and in the academic literature (Barker, Citation2005; Earley & Evans, Citation2004; Elmore, Citation2004; Zhang & Brundrett, Citation2010). Studies therefore highlight the role of mentoring and contextualized support for new headteachers, emphasizing elements of organizational socialization in building an effective knowledge base for leadership:

School leaders’ preference for leadership knowledge stems from long-time practice […] the majority of their learning in the workplace is informal, and involves a combination of learning from colleagues and learning from personal experience, often both together. (Zhang & Brundrett, Citation2010, p. 156)

Similarly, the value of declarative knowledge has been highlighted by Chi and Ohlsson (Citation2005) who conclude that building a complex body of explicit knowledge over time moves along multiple dimensions of change. These include a larger size of the knowledge base, more organized hierarchies of content, denser connectedness, increased consistency, greater detail and complexity, a higher level of abstraction, and a more developed vantage point. A degree of crossover can be expected between headteachers’ declarative and informal (perhaps best considered as explicit and implicit) knowledge of school organizations, since the degree of reflection and ability to articulate such knowledge likely varies between practitioners. These are the two types of professional knowledge that are the focus of the present article.

Findings concerning school leaders’ declarative knowledge include knowledge of their own local contexts – understanding the needs of stakeholders, for example, allows middle leaders to more effectively ‘translate’ improvement strategies for their schools (Nehez et al., Citation2022). Knowledge of a school’s improvement history, and the resulting ability to effectively communicate it to staff, may be a powerful vector for enabling team members to personally connect with it (Liljenberg & Blossing, Citation2021). Research has also highlighted key professional knowledge that headteachers often lack, for example, knowledge of effective goal-setting for clarity and cohesion (Lindberg, Citation2014), a deficit that is typically associated with ineffective school organizations (Jarl et al., Citation2021).

Day et al. (Citation2000) note exemplary headteachers’ personal knowledge of staff, pupils and parents, and their knowledge of the principles of relationship-centered leadership and of change management. Other studies have highlighted headteachers’ knowledge and utility of the school structure. For example, the role of elementary headteachers is highlighted by Zhang et al. (Citation2011) in engaging students and teachers as agential learners in school cultures oriented toward collective learning. This study argues for a principle- versus procedure-based approach, but also suggests that headteachers’ ability to implement cultural change effectively at every level of the school is achieved through establishing specific organizational routines and partnerships.

Research findings relating to informal knowledge reflect the potential depth and insight it can provide into the dynamics of school organizational culture. Fernandez (Citation2000) encourages us to recognize that the role of the principal has increasingly become grounded on influence and persuasion rather than control and management. Thus, knowledge of schools as an emotional environment, particularly in relation to knowing appropriate and reasonable expectations for organizational climate, may also constitute relevant organizational knowledge (Day et al., Citation1998). This may include, for example, the awareness that team members have limited memory, and tend to distort the recall of events according to their current psychological needs – or that the desire for acceptance within a group often makes team members susceptible to following the majority in exchange for group membership (Kilmann, Citation1984). Knowledge relevant to cultural leadership – for example of how to model knowledge-sharing individuals and teams (Zeinabadi, Citation2020) – takes a variety of informal modes. Yuen and Cheng (Citation2000) emphasize the knowledge involved in inspiring, supporting and enabling staff. Zhang and Brundrett (Citation2010) highlight knowledge of coaching, mentoring and the individual being coached – for many headteachers, this extends to teaching staff and other leaders (Day et al., Citation2000).

Methodology

The qualitative data reported here draws from the Organizational Health in the Primary School research project, created with partners from the Devon Schools’ Leadership Service and Tarka Learning Partnership. The wider project used an explanatory sequential design involving a short quantitative elicitation and semi-structured interviews, followed by reflective coaching conversations with some of the headteachers as part of their own professional development. This article draws on one of the two major qualitative code categories in addressing its research question, reporting specifically on insights from the interviews for headteachers’ explicit and implicit knowledge of schools as professional organizations.

Semi-structured interviews were used for the benefit offered through the clarification or probing of points raised, while retaining a number of core questions that all participants responded to. These included an elicitation of the headteachers’ experiences as a headteacher, the nature of the school environment, their understanding of their role within the school, their understanding of effective and ineffective school organizations, the impacts and needs of different stakeholders, and the implications of this understanding for their own practice. It also involved a reflection on the results of the quantitative element of the wider study, which emphasized the role of communication in schools and the reasons for this.

Sample and ethics

The headteacher sample comprised 10 headteachers (6 M, 4F), whose collective experience in the headteacher role surpasses 150 years (mean = 15.7 years) in British primary schools. Of these, two had held responsibilities as National Leaders of Education (NLEs), five had been appointed as Professional Partners to mentor other headteachers in the county, five held additional responsibilities as Executive Headteachers or CEOs within Multi Academy Trusts (MATs), and two had experience working as inspectors for the local authority and national Office for Standards in Education (OFSTED). Five of the participants were recruited following their appointment to the Devon Schools’ Leadership Service. Snowball sampling through one of the NLEs sourced the other five, who were recommended following inspection for their approaches to forming professional cultures and repeated record of school turnaround. BERA ethical guidelines (2011) were adhered to throughout the study, and ethical approval was gained from the University of Exeter (D2021–023). Written consent forms were signed by all participating headteachers, who received a copy of the research proposal as well as a letter describing the nature and purpose of the study.

Data collection

Including the pilot interview, a total of 11 virtual semi-structured interviews were conducted and recorded over Zoom with the headteachers over the course of 2021–22, with the last interview occurring in January 2022. Prior to this, headteachers had submitted a short ranking task where they considered an existing framework relating to organizational health in schools (see Miles, Citation1969). This served to elicit responses to some of the existing vocabulary and consideration of key constructs ahead of the interviews. The interviews lasted approximately 60 minutes, with the shortest being 50 minutes and the longest being 90. This totaled 14 hours and 48 minutes of audio data.

Data analysis

This article reports results from the inductive thematic analysis (see Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) used to codify the headteachers’ responses. The 11 interviews were analyzed through stages of open, axial and selective coding using the qualitative data analysis platform NVivo. Statements relating to the research questions were identified, labeled with a temporary thematic code, and then revised and categorized as the dataset developed (Saldaña, Citation2016). The codes represent both direct statements about schools and the subtext of statements in which the school organization is referred to implicitly. Together, these aim to capture the headteachers’ declarative and informal knowledge of schools. The analysis generated a total of 880 data points. A summary of the final thematic codes and their definitions is shown in .

Table 2. Summary of code definitions.

Strengths and limitations

The research design yielded a rich dataset of insights about the expertise and practice of a unique group of headteachers within the United Kingdom. The high proportion of headteachers with mentoring and coaching responsibilities in the sample assists in the elicitation of professional knowledge focused upon in the study. This richness, and its potential value, is one major strength. This is heightened when considered in relation to the research gap, and the wider needs of the educational community that the study addresses. The process of returning to transcripts and contextualizing findings through the post-interview coaching conversations with headteachers served to heighten theoretical sensitivity in the interpretation of findings (see Charmaz & Thornberg, Citation2021).

One wider limitation of self-report data and of qualitative analysis more generally relates to the interpretive nature of the research. Much of the data collection occurred against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, which restricted access to schools and problematized observation of the headteachers within the data collection window. While this may have offered a chance to view or challenge the findings, these circumstances also offered some benefits: headteachers described greater space and a different vantage point to reflect on and evaluate their practice and ‘what matters’ in reading their professional cultures following the first major lockdowns. Furthermore, the focus of the research lies with their expert conceptions of their organizations, which are arguably most appropriately accessed through the semi-structed interviews conducted, with limited benefit through alternative methods for the domain of interest.

Findings

The five themes discussed in this section were built up from findings across the dataset, with references spanning across the 11 interviews to generate robust categories of codes. This section of the article outlines each of the themes in further detail. For each, an overview of each theme precedes a table summarizing the distribution of references across sub-codes. Following this, a more detailed description of each sub-code is presented with supporting quotation. Overall, the findings suggest that the headteachers gained a rich and comprehensive understanding of the school environments they had served over the course of their careers.

Indicators of organizational culture

The headteachers attended closely to a particular set of cultural indicators that they worked with to achieve their desired outcomes. The numerical dominance of references relating to this code category demonstrates that many statements within the interviews either explicitly or implicitly referred to actions taken to either form a desired culture or, conversely, to understand or counteract one deemed dysfunctional. The prominence of this code category speaks to the intentionality with which the headteachers sought to form their desired professional cultures, and to establish their own professional and organizational identities in contrast to school cultures that they had observed to be negative or ineffective through their experiences as experts.

Collectively, the sub-codes show how the headteachers attuned closely to the organizational climate within the school, and that many of the desired cultural outcomes were mirrored by equally undesirable ones (see ). In many cases, headteachers found it helpful to articulate cultural indicators with reference to the professional environments they sought to avoid, or pitfalls observed in schools across their careers. The headteachers described the culture of schools in terms of everyday interactions and subtle details, ‘all of those little sort of nuances that you perhaps wouldn’t necessarily notice’. Dysfunction was identified over time and after ‘slotting all of the jigsaw pieces together’ and knowing the ‘telltale signs’ where a school might be ‘starting to tip’.

Table 3. Indicators of organizational culture sub-codes and definitions.

Headteachers unanimously referred to the quality of relationships within the school environment as a key indicator of school culture. They therefore approached the task of forming effective professional relationships intentionally, and in a variety of ways. This was discussed as the most immediate indicator of the school climate: ‘ The first thing I would be looking for is the interactions between the staff to see what the kind of culture is there; are these people able to talk to each other in an effective way?’ Other participants described that much of the role of headship entailed ‘just making sure that those relationships are right’, and that professional relationships served as a vector to other desirable outcomes:

You’ve got to develop the relationships to have the right communication […] you’re talking and communicating it at an informal level with people and you know them and you know how people are feeling.

Over a third of the references within the ‘Quality of Relationships’ sub-code referred to the crucial role of trust in schools. The headteachers described this as underpinning even very basic organizational processes, which were described as ‘nothing without trust […] if you haven’t created that trust and you haven’t got those relationships, you can communicate all you want, but it’s never going to work’. Eight of the headteachers referred to the importance of psychological safety within the professional environment. This was particularly salient in underperforming or dysfunctional schools, where teachers may be ‘frightened to open their classrooms up to their colleagues’, hindering collaboration efforts. They also described the issues caused by a climate of fear, where entire teams ‘didn’t know who was going to get scrutinized next’. The headteachers linked trust and psychological safety to teachers’ confidence, but also to the practicalities of leading more responsively in schools. As one headteacher put it, ‘if they feel safe and they trust you, you can get away with faster change’ both in terms of professional learning and shifting strategic priorities.

Almost all of the interviews emphasized the role of a sense of aspiration within the school environment, and described the benefits of a professional culture of improvement. Headteachers emphasized that the lack of a learning culture in failing schools typically gave rise to a sense of complacency. This was described as a collective ‘reticence and acceptance that actually children could do no better’, because ‘everything’s so set and so structured, people are feeling safe for the wrong reasons’. For two of the headteachers, lack of aspiration was characterized by the absence of shared responsibility in schools. They described schools in which staff worked in ‘silos’ with ‘closed doors’, and developed an ‘almost tribal’ view of one another. In schools where staff ‘weren’t working together’ and ‘people weren’t taking responsibility for anything […] things were just drifting’, this was understood to have a tangible effect on the school’s functioning. Conversely, shared responsibility and ‘leading upwards’ was described as a positive sign within the school organization. Seven of the headteachers framed teaching as a leadership role in which staff were ‘leading their classes, leading the other people that they’re working with’ and creating a self-sustaining culture or direction for the organization.

Similarly, the importance of achieving clarity within the school organization was emphasized by the headteachers. Three of the headteachers described the importance of articulating goals carefully and repeatedly to create ‘clarity around what everyone’s trying to achieve, and general consensus around that’, and ‘having to be really explicit about it’. One headteacher described how their investigations into disillusionment within schools usually centered around issues of ambiguity: ‘When you got to the nub of it, it was always about not knowing what the goals were, what we were doing’. One headteacher emphasized that the normalization of a lack of clarity was a common feature of the Requires Improvement schools they had visited, in which staff ‘almost accept it and are not aware until that layer is lifted, and they become conscious of something different’.

The headteachers understood the importance of clarity in relation to the professional culture of effectiveness in schools, linking it to performance and the motivation of the team. The issue of ‘buy in’ from staff regarding change was raised by five of the headteachers, a problem that manifested over time. If, after accepting a change, staff were ‘still not really sure why, they’ll do it, but it, over time that will create a lethargy to it’. Clarity in terms of vision and values was viewed as a necessary precursor to coaching, mentoring, and formal processes to those who resisted change. Headteachers used this clarity of vision to ‘set your expectations about what you expect from all of those people’. Yet headteachers viewed disagreement and staff input on decisions as constructive and even reassuring. One described the importance of ‘creative discussion and actually being passionate about things’. Even ‘pretty fiery’ disagreement worked as a ‘check and balance’ mechanism that was valued in shouldering the ‘weight of responsibility to do the right thing, to make the right decisions’. Furthermore, appreciating the diversity of different professional strengths was understood to enhance effective practice in schools. The headteachers strove to balance the shared experience of a change with the freedom for individual teachers to ‘breathe and move, and lead and adapt’.

Nine of the headteachers contributed statements to the sub-code relating to disaffection within schools, and the controversial topic of staff fulfillment and wellbeing. Staff motivation was generally regarded as very important. Complacency and lack of challenge, however, was described by some of the headteachers as symptomatic of problems. Outcomes for pupils were described as ‘intrinsically linked’ to the needs of staff, and could be understood as ‘a function of the staff performing and achieving’. The headteachers understood that a crucial part of their role was to make decisions to put ‘the best provision and quality in place’ so that ‘everyone else does their job’. Removing barriers that might ‘get in the way of people being able to focus on the job’ served to ‘enable’, ‘keep developing’ and ‘empower’ staff to perform.

The nature of cultural leadership in schools

Part of the headteachers’ conceptualization of the elementary school as an organization relates to their understanding of their own role as a school leader. The headteachers described organizational culture in schools as a set of knowledge and skills acquired beyond the most immediate and pressing qualities demanded of a headteacher, and articulated change in terms of time and capacity:

When you take on a failing school, I mean, you don’t have a lot of time to fix it. I mean, you just don’t, is it, yeah, it’s not, it’s a, it’s a very interesting experience […] you get to a point just like learning to drive, you get to a point, they will say, you know, you really learn to drive after you pass your test. So it’s a little bit like that, you know, you get this, I’m doing all these things very, very quickly. And the challenge, isn’t it, is to then sustain that kind of moving forward. That’s where it gets more interesting, to be honest with you.

. provides a breakdown of the distribution of the different sub-codes.

Table 4. Nature of cultural leadership sub-codes and definitions.

Seven of the headteachers referred to their leadership role in terms their own professional identity, particularly in terms of adopting a stance and setting the tone for the professional culture of the school. The headteachers stated that a school’s culture often ‘comes down to the personality at the top’ since ‘so much of this role is about personality and our own morals, and what’s driving us’. They understood that without articulating their own beliefs and values as educators, they ‘couldn’t move’ the staff or parents within the school organization – instead ‘you set out your stall and say very clearly, this is where the school’s going’. Identities arose such as being ‘a very hard worker, and an enthusiastic worker’, displaying ‘absolute authenticity’, and their personal feeling that the school ‘should reflect what the local community want’. In one school with a particularly strong professional culture, the headteacher was very intentional about communicating their values:

I’ve made that very explicit to the staff. I value collaborative working. That’s why we work the way we work, and I value it for these reasons […] the school in terms of its culture now actively celebrates, you know, people come to the school to work because of the way we work in a sort of collaborative way.

Nine of the headteachers described organizational change as a long-term investment, where their stances and resulting interactions manifested in their desired professional culture forming over time. The headteachers drew on various metaphors and analogies to frame their role as that of an ‘architect’ and the school as a ‘juggernaut’, where it ‘takes a long time to turn that ship where you want it to go’ in terms of the strategic ‘bigger picture’. One headteacher described their interactions with stakeholders within the school as ‘filling people’s piggybanks before you take out’. This metaphor captured their everyday actions to invest slowly through positive interaction in readiness for any potential challenging conversations or increasing responsibilities in the future. Another headteacher referred to playing ‘the long game’ with stakeholders who may resist change. The importance of consistently pushing the desired cultural shift was articulated as analogous to a football coach’s sustained success with a team: ‘You can win one title, but to do it year after year is really difficult’. Two of the headteachers understood their role in driving cultural change as highly individualized, where ‘interactions at whatever level’ determined continuous change, amounting to a ‘significant era in time […] whether the next person can take that and move it on in the same way, I‘m not so sure’.

Related to the headteachers’ investments over time is their closer reading of the timing of their actions, and to ‘adopt different approaches as is needed for different situations’. While one headteacher characterized poor leadership as ‘reactive’, collectively the headteachers described a reflexive approach to their roles. The distinction to be made here relates strongly to the element of intentionality and responsiveness in dialogue with the cultural ‘whole picture’ and making the ‘right choices at the right time […] to adapt to whatever’s thrown at you and not be so rigid’. This included an intuitive approach to ‘spinning the right plates at the right time’, knowing when it might be appropriate to bring out ‘the performer in the headteacher’, as well as ‘knowing when to turn over rocks and when not to’. While creating clarity in terms of expectations, vision and strategy was generally emphasized in the interviews. One headteacher referred to allowing for elements of ambiguity when navigating new changes: ‘We have lots of fog here around things that we want to be foggy – you know, sometimes you need the fog’.

Six of the headteachers referred to a key aspect of the school leader’s role as that of shouldering responsibility. Statements made by these headteachers related to the breadth of the role, the individual toll it can take, and the requirement for containment. This responsibility meant that school leadership could at times be ‘an incredibly lonely job’. They described working to prevent pressure getting ‘passed down the chain’ from leadership to staff to children, and the challenge of trying to ‘know everything and be in control all the time, to have all the answers and to try to exude that kind of confidence’. One headteacher articulated this as wanting to ‘protect everybody from the, I don’t know, the dangers or the risks … ‘cause I just think it does, that has an adverse effect on everybody as well’.

The headteachers who acted as mentors for other heads described them ‘burning out […] because they’re trying to do everything’. The breadth of responsibility and ‘Jack of all Trades’ nature of the role was highlighted, particularly in smaller schools: ‘The amount of time I spend up a ladder changing light bulbs, cleaning toilets, sweeping the floor, you have to do everything, you have to turn your hand to absolutely anything and everything’. One element of self-regulatory knowledge offered by one headteacher related to the importance of leaders seeking their own help when struggling with ‘the weight of everything’ and to learn to ‘place honesty on the table […] on a professional level and a personal level, just opening up, making yourself vulnerable’.

The expert headteachers were unanimous in conceiving their role as entailing the support and motivation of their teams. It was important to each of the headteachers that staff and stakeholders felt seen and understood by the school leadership. Losing touch with staff was linked to retaining the right team members: ‘Heads become detached from their staff; and then as soon as the staff feel that, then you’re losing, and those who become disaffected and can often drift and leave’. Practices for addressing this included many of the more pastoral elements of leadership in a school setting as well as daily interaction, and resulted in a variety of practices such as scheduled career conversations, informal greetings, and recognition practices utilized by the headteachers as they strove to ‘create the optimal conditions’ for working within the school. This related to the headteachers’ conception of their own role entailing ‘knocking down the barriers’ to staff doing the job of teaching effectively and by ensuring ‘that these teachers have everything that they need, and that goes from glue sticks to intellectual professional stimulation’. Furthermore, it included elements of containment as it related to empathizing with the experience of teaching, part of the role being to gatekeep and remain grounded by realistic expectations from staff.

Understanding schools in context

A theme which retains a high degree of significance despite fewer references relates to the headteachers’ understanding each elementary school relative to its context (see ). This includes the wider educational landscape, the community that the school is situated within, and the history of the school itself. Much of the headteachers’ knowledge related to such factors, and actions taken were directly influenced by this knowledge.

Table 5. Schools in context sub-codes and definitions.

All of the headteachers made reference to the larger cultural context of education in the UK when articulating their knowledge of leadership in elementary school organizations. This is because the professional cultures of schools are affected by the commercial interests influencing education (such as training and resource providers), the way teaching as a profession is portrayed by the media – particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic – the policies formed at higher levels of the education system, and the frameworks and practices utilized by inspection bodies.

The deficits in current and past models of training available to headteachers were outlined. Three of the headteachers described the ‘on the job’ nature of acquiring of such knowledge as this article has sought to codify, since their main training and success had been as a teacher in the classroom: ‘I had success as a teacher; it didn’t mean that I was going to be a successful head teacher’. The cultivation of professional relationships was identified as another shortfall, as well as how to ‘read’ the school organization itself.

Commercial interests affecting education also surfaced. These related to the discernment involved in selecting in-service teacher that translated to meaningful change, rather than ‘making a fast buck for some organization’. Headteachers also articulated the pervasive fear that standards inspectors would hold individuals ‘liable, rather than accountable’. The effects of the scrutiny and pressure in the media meant that certain types of training appealed more to teaching staff who had become risk-averse and fearful of new learning. The headteachers expressed self-awareness around aspects of leadership and management that, similarly, appeal more to many school leaders: ‘We create things to make us feel safe in this, in the education structure; and we don’t think about what impacts that has’.

Similarly, the role of the local communities served by schools was referred to in five of the interviews. This included both attuning to the character of the community and activating stakeholders within it as headteachers sought to improve the professional cultures of the school. Understanding the community involved learning its desires and needs, and appreciating its uniqueness as well as any shortfalls or deficits. In this sample of headteachers, these included the lack of diversity and experience in some local communities, as well as high deprivation and low aspiration in certain areas. Including community stakeholders in forming and enacting the vision was a common action taken among the headteachers interviewed, with the perceived benefit that ‘it brings together the whole community and we’re working together as one, we have this one vision’. It also meant that the wider community could ‘be proud of the school their younger children go to [and staff could] feel part of something a bit more’. One headteacher described this process in greater detail:

We brought in the whole community to speak to them about what the vision for their community, for their children, for their school was […] having a real insight and input into the final vision results means that they really do buy into it, they’re passionate about that vision. They want to take it forward. They want to make it work.

Six headteachers referred to the recent history of individual school organizations as influencing their professional cultures. Participants understood that part of the role of the headteacher was to ‘set a climate and expectations and shape the journey of the school, which will be different at different points in time’. This included the difficulty of inheriting a certain school reputation and the impact of this on how the scope of leadership was perceived – ‘it’s very hard to shake off that, that reputation, that you’re not 100% focused on school improvement’. The headteachers also described the difficulties raised by legacy hires in times of difficult change:

That needed different people coming in, because you actually had to choose those people to get that compliance and actually, if you weren’t going to be compliant, then you needed to go… that’s very different to where we are now.

Four headteachers also discussed how the size of the school (and therefore the size of the staff team, and the scope and frequency of interactions that were possible) affects the demands and remit of the headteacher. In larger schools, this necessarily entailed ‘a mind shift to being strategic and allowing other people to do things’, since it was not feasible to assume personal management over every child.

Appreciating schools as human environments

A sizable cluster of codes pertains to the headteachers’ knowledge of people, and how to work constructively with them to achieve the desired outcomes. presents an overview of the theme relating to school organizations as human environments.

Table 6. Schools as human environments sub-codes and definitions.

Individual diversity was discussed by the headteachers in terms of professional strengths and ways of working as well as in terms of individual effects on the professional culture. In terms of headteacher knowledge, this holds a variety of implications relating to hiring, monitoring, planning for and conducting meetings, and everyday interaction with both staff and parents. Headteachers described the ‘broad spectrum’ of personalities found within a school including staff members, parents, admin and support staff, and articulated the need to be a ‘chameleon’ or a ‘social butterfly’, in order to ‘switch on and off how I behave in different situations’.

Headteachers highlighted the advantage of a range of individual strengths within staff teams. This diversity of value and different views was seen as advantageous by the headteachers, and was expected. However, knowledge of different interpersonal needs had implications for facilitating engagement with these teachers, and ways of ‘valuing the way people work’. For example, in terms of digesting new information in staff meetings, one headteacher was conscious of allowing time for staff to form insights and opinions on new directions. Knowing that ‘not everybody thinks that way, some people need time to consider’, they therefore sought to share information ahead of meetings. In a similar way, another headteacher was aware that gathering all staff in the same room meant that ‘you’ve got some very big voices and some big characters who might dominate’, and took action to give other voices a chance to be heard through small group discussion first. Another described a desire not to ‘squish’ professional strengths through their leadership practices, linking the enablement of teachers’ individual differences to their sense of ownership in the role: ‘People have to be trusted and have that ownership and want to be doing it happy, you know, on board to a point’.

The headteachers demonstrated an intimate knowledge of how individual team members affected the professional culture of the school. This was expressed in terms of interdependency – ‘no school can function without any other team member in it’ – as well as the dangers associated with hiring the wrong individual:

It’s really interesting, a whole school community can be affected by one person; and I don’t think anybody realized until that person wasn’t here.

We recruited inexperienced teachers for the experienced teachers that we lost, and that was a huge cultural drain on the school.

One change of person [had a particular set of issues] and it created a very toxic atmosphere.

The headteachers expressed detailed knowledge of team members’ needs, for example that some individuals within the school benefited from ‘more intimate communication’ or that ‘just need to touch base more often’, while others needed more in terms of permission, confidence-building, or to be kept in the loop around strategic changes to feel in control of their classrooms.

Seven of the headteachers described the role of ideological and cultural aspects that affect school organizations in different ways. These headteachers described the importance of forming a ‘sense of identity’ for the school by ensuring that all parties were ‘signed up to the philosophy’ rather than ‘just going through the motions of being part of it’. Three of the headteachers discussed entering schools where an ‘ingrained’ set of attitudes had to be ‘shifted’. Once this was achieved, and the new desired culture had been formed, it too was described as ‘embedded’, taking hold in a similar way:

The culture in the school is it’s so clear and so established now I do think there are elements of you kind of have to buy into it, otherwise it’s quite difficult place to work.

One headteacher described the interim stage as ‘a period where people just trust the decisions being made and then you open up enough so that they feel within that they’ve got that flexibility, and they have that responsibility and ownership in it’. Others discussed the importance of constructive ideological conflict in the school, and the importance of expecting and encouraging differences of opinion: ‘Conflict is normal, difficult conversations are normal, and we shouldn’t be so scared about having them’.

Six of the headteachers described the managerial obstacles unique to school organizations. One statement, relating to the previous code category, alluded to the difficulties of working in an environment where individuals held different ideological conceptions of education and childhood:

Everyone has their own idea, depends which book you’ve read, depends who you follow, depends on your own experiences, and it does mean you get lots of chefs.

This element of differing ideologies meant that staff could be expected to interpret and implement things differently in their classrooms:

People are then going to translate that, aren’t they, through their own sets of values and their own skills and what they think is important in a classroom, they will, we all do that.

One headteacher described the difficulty of moving support staff from an ‘entrenched’ view of their hourly ‘job’s worth’ value and corresponding effort levels, while another discussed the inherent difficulties of establishing what may be affecting culture in a school, and the need to gather a wide range of evidence to figure out events and underlying causes.

Headteachers described the nature of the job of teaching, describing the role as creating ‘mini control freaks’ who can often exhibit a ‘superhero fallacy’. This was understood to have an impact on the nature of school leadership, creating line managers that could be ‘neurotic’ after starting their careers in charge of their own classrooms:

If you’re in a classroom you probably may have come into the profession because you actually quite like your own company; there’s a number of things like that, when actually you need a different set of skills to work with a team of people.

School leaders with a background in teaching may be prone to imposing their own views and practices on others – ‘they micromanage, because they were a really strong class teacher and they want that teaching across the school’ – or may be led by a particularly strong moral obligation – ‘we want the best for every child and we know the way we’re going to, to get them there’. Such insights provide clues into the crucial role of self-reflection and self-regulatory knowledge in successful school leadership.

Headteachers commented on requirement to manage of pressure and remain sensitive to workload capacity in school organizations. This applied both to the role of teaching and to school leadership. The headteachers understood the effort necessary ‘to keep all those plates spinning’, and had witnessed that in environments where support was lacking that staff were ‘sinking under the weight of what’s being asked of them’. Yet, workload was generally understood in terms of balance, and a potential pitfall for school cultures:

In some schools that, where I’ve gone into […] that wellbeing agenda is being taken too far, and it’s almost become a sense of, a reason for complacency.

Similarly, the landscape of education demanded elements of cohesiveness and quality teaching:

You need everybody going in the same direction because the stakes are so high, the needs of the children are so high.

Headteachers described ‘trying to balance [that tension] up’ by ensuring that the ‘balance of work’ was on what makes a difference to the children rather than elements of the role that had less impact. Professional wellbeing was therefore conceptualized in terms of ‘achieving what you set out to do’, ‘making a difference’, and ‘working hard for the children’. To balance the high and ‘honest expectation’ of staff, the importance of school leaders creating psychological safety was highlighted:

It needs not to be unrealistic, it needs to be couched in an understanding that we’re all human, we make mistakes, and that you create that safe zone for those staff where they can explore things and make mistakes.

Headteachers highlighted the importance of ‘reading the room’ and empathizing with staff, even when they may be acting unreasonably: ‘You don’t know what they’ve come in from’; ‘You always get the end of term tiredness anyway don’t you, where people get a bit grumpy’.

A final sub-code captures statements relating to the headteachers’ use of emotional intelligence to successfully interact with others within the school organization, and how they utilized their understanding of people’s needs. This knowledge arose in eight of the interviews and underpinned the headteachers’ recognition practices, ‘keeping everybody so that they feel part of the organization’, as well as their everyday communication and management styles. Headteachers described their conscious efforts to ‘to keep everybody topped up’. This understanding of morale as a fluctuating, transient state that would rise and fall necessitated a balance of challenge and support – ‘if one of those two is out of kilter, the other is less effective’. It also required knowledge of navigating conflict by validating emotions and opinions. Knowledge of individual needs fed into how they onboarded new staff and parents, targeting and recognizing individual contributions to the school, and being aware of the potential risk associated with each message that is shared:

Every bit of communication has a potential to, to come back and bite you in the bum […] it’s such a brutal thing in some ways, that you can put a lot of time and a lot of thought into it and think you’ve got it right. But some people still read that in the wrong way. They’ll still hear it in a wrong way. And then you’ve still got to do that kind of reparation work.

Complexity and opportunity in school organizations

The final category of codes relates to the uniqueness and complexity of schools as organizations. The headteachers articulated the difficulty of their role in relation to the shapelessness and obscurity of school structures. They offered insights both into what these complications looked like, and the necessary requirements of leaders to meet these unique complexities ().

Table 7. Complexity and opportunity sub-codes and definitions.

The headteachers outlined features of elementary schools that made them unique as professional organizations. Elements of ambiguity make them difficult to navigate, both in terms of ascertaining the nature of a problem – ‘you can see that things aren’t right, but it’s unpicking why’ – to the complicated allocation of responsibility in many schools. References were made to how roles were often less clearly defined, and how ‘the lines are really blurred’ within a school structure. Community members may, for example, work as staff while also having a child in the school. Furthermore, one role may entail multiple disparate responsibilities. Depending on the size of the school, jobs could become ‘a bit muddled and muddied, and everybody does a bit of this, that, and the other’, and that, ultimately, ‘everybody’s a leader in a school’. Indeed, this sense of nested leadership within the notion of ‘teachers as leaders’ was linked to a critique of the training available in this regard:

Pretty much every teacher will have at least one or two adults in their classroom which they are responsible for leading, and you don’t really get training on that.

Headteachers discussed interdependency in the school. They articulated how teaching depended on a functional network not only of subject leadership and community relationships, but also through the teams of office, kitchen, premises and cleaning management, and ensuring that such systems were serving one another well. Related to this, once challenge described by two headteachers involved the damaging role of hearsay, and the perceptions of different siloed teams within the schools of one another.

Complex networks among different stakeholders meant that headteachers had to work as a conduit for multiple groups within the school, requiring proficiency in communicating with multiple groups. Successful leadership therefore entailed the ability to ‘simplify the messaging and get it out and overcommunicate it and keep it consistent’. However, the challenge of effective communication was also outlined; often ‘people hear different things from the same message’, and ‘when you communicate something you have the potential to divide people’. Furthermore, the transience of messages was a further challenge, since the situation ‘shifts and changes all the time, so as soon as you put that communication out, it’s almost out of date; that’s the frustration’. Despite such challenges, the shapelessness of the school organization simultaneously offered opportunity, flexibility and the chance to adapt for some headteachers. The school day, for example, could begin earlier or later depending on how this might address existing issues and potential benefits, and listening to staff.

Due to this shapelessness and obscurity, all of the headteachers offered insights as to how to meet the complex nature of elementary schools by outlining the organizing requirements of leaders to meet these needs. Creating clarity and achieving the right balance of communication were seen as crucial, particularly in the face of constant change:

The problem with schools is that you just layer the next thing on top, and you never ever tell your staff to get rid of anything; and then people become overwhelmed and confused and they just become tokenistic

For some headteachers, the creation of an electronic handbook was a particularly useful way to capture expectations and best practices within their schools. Clarity also involved explaining the rationale behind decisions:

When I think about the big things that we’ve implemented, we’ve been able to do that by really getting people on board with the “why” we’re doing it rather than the “how” we’re going to do it.

The headteachers described the importance of establishing systems and processes within the school organization to follow up on decisions taken and to form culture. Due to the amount and speed of work in a school, ‘deadlines, action points, all of those things need to be documented so that you’ve got a paper trail of what’s going on because people are busy’ – agreed actions may otherwise fall through the cracks. Relationships and culture were discussed by one headteacher as an outcome ‘that partly comes from a pile of structures of communication that are very, very clear’.

Strategic elements of school leadership were highlighted, since the constantly shifting landscape of education meant that ‘if you’re not reading what’s going on outside of wider than this, you’re already behind’. Shifts in direction required heads ‘to take a step back and plan for [handling change] in a much greater way’. Because of this imperative, headteachers saw a need to allocate time to consider their strategy, prioritizing ‘getting into that space where you’re leading not doing […] you need to set up those structures to make that happen’. Several headteachers reflected on their targeted approach to everyday interactions with parents and staff – ‘Which gate do I need to stand on?’. One headteacher described their approach to strategic change management:

I’ll drip into conversations way before it’s even written down […] you choose key people … I have key players within school that I sell to first and then they sell out […] sideline conversations with dripping and change; none of them formal, I’ll run down the corridor and go, ‘Do you know what, we should do this’, then I’ll walk on and leave that person thinking.

Here, an ongoing series of conversations provided opportunities for ‘bringing language in as well that you want to use’ so that, when a more formal change occurs, they had already ‘sown the seed’ and created a sense of ownership among stakeholders. The inherent risk of implementing continuous change meant that ‘part of being open to learn is being open to fail’ and that, once again, once again, the role of trust and empowering teachers through an appreciation of professional diversity was emphasized. Parents were often referred to as a barometer of the school’s cultural effectiveness and any deficits in terms of clarity, and were referred to as ‘the first to tell you when your communication’s wrong, and you pick up on that very quickly’. They were also described as an indicator of when deeper dysfunction may be starting to appear:

Parents then pick up on the children not feeling quite right or coming home a little bit unhappy. The staff then start to pick up on parents having their niggles.

Discussion

This article has been informed by the research question ‘What might constitute key organizational knowledge for the effective leadership of elementary schools?’. It has outlined the headteachers’ declarative and implicit knowledge regarding the context, role of leadership, environment, structural parameters, and the indicators of professional culture that the expert participants attended to. Their reflections on such knowledge, formed over the course of their careers, offers a helpful starting point for considering what such key professional knowledge might look like for forming and maintaining professional cultures in schools.

The five key themes can be understood in terms of three relationship-oriented themes, Indicators of organizational culture, The nature of cultural leadership, and Appreciating schools as human environments, which illuminate how the headteachers thought about their own influence and purpose within the school organization as well as the influence of other actors within the network. The remaining two themes are structure-oriented, in that they are concerned with the ways in which the organization is made up of differing elements. These themes focus on the headteachers’ conceptualization and assessment of the elementary school organization itself – Understanding schools in context, and Complexity and opportunity in school organizations. This distinction between the relational and the technical or system elements of organizational theory have already been highlighted in theory and research (see Blossing & Liljenberg, Citation2019; Dalin, Citation1994; Nelson et al., Citation2008; Sergiovanni, Citation2004). It has been established that knowledge and skills in both areas are required of school leaders, who must attend to the personal and relational needs of their teams while building streamlined structures (Garza et al., Citation2014; Liljenberg & Blossing, Citation2021; Moos et al., Citation2011). The present study has looked at the knowledge gleaned by the selected headteachers in understanding the structures of their school organizations, and the actions taken within their network to shape professional culture over time by fostering productive daily interactions in line with their vision for their schools.

Although this study was not designed to explore the prevalence of relational or structure-oriented organizational leadership, the numerical dominance of codes in the relationship-oriented categories may suggest that the headteachers had gained more knowledge in this area over their careers. This assertion is reflected in some studies (for example, Hult et al., Citation2016; Törnsén, Citation2009) which found a predominance toward social and relational aspects of school leadership. Others, however, have indicated that headteachers primarily attend to formal aspects such as work routines (Blossing & Liljenberg, Citation2019). In this study, focus lay with eliciting acquired knowledge from a sample of experienced headteachers, many of whom held mentoring responsibilities for others. It is plausible that the predominance of statements concerning social and relational aspects of school organizations made up a greater proportion of acquired knowledge for these headteachers; it also reflects what is currently neglected in formal headteacher training or in the ongoing pressures created for headteachers by neoliberal policies and results-oriented accountability in England (see Alexander, Citation2008, Citation2010; Hall et al., Citation2017; Moore et al., Citation2002). For the headteachers in this study, much of the complexity of the school organization was understood to lie with the nature of working with children and within education, where political agendas, ongoing research findings, media representation, and theories of childhood collided in a busy environment.

As a relationship-oriented theme that focuses on the actions of the headteacher themselves, The nature of cultural leadership highlights the reflexivity, self-regulation, and long-term investment entailed in forming professional culture. The headteachers understood their own influence in setting the tone for the values and ethos of the professional environment, and in supporting and motivating teachers. They understood that, through their actions, they could activate powerful mechanisms within their team networks. What is most salient about the statements made by the headteachers included in this study is how they understood and placed value in intentional, often targeted, everyday interaction over time. Indicators of organizational culture is a theme that captures some of the resulting impacts on the relationships that characterize professional climates within schools, and may serve as a potentially useful set of constructs for the development of grounded measurement tools or feedback frameworks.

As a theme concerned with the fundamental character of work within a school, the theme Appreciating schools as human environments offers insight into some of the informal knowledge utilized by headteachers, and highlights in particular the value placed on diverse professional strengths and viewpoints, while outlining some of the challenges they can present. For example, the relationship between trust and school effectiveness has previously been highlighted (Ståhlkrantz & Rapp, Citation2022; Visone, Citation2022; Zeinabadi, Citation2020). Yet, as Gobby et al. (Citation2022) point out, organizing a professional culture that is supportive of teacher agency can produce tensions for leaders, who must enact a performative managerialism that seeks greater control of teachers whilst enacting decision-making that promotes professional trust and teacher autonomy. For the headteachers in the sample, the fine line between accountability and professional autonomy was mediated by the needs of the school organization at different points in its journey. Trust and autonomy were understood as ways to enhance practice and achieve the best from staff at all levels, but which had to be tempered by accountability measures as part of a ‘challenge and support’ counterbalance that served the purposes of professional development for teachers, or which yielded greater clarity or cohesion across the staff team at appropriate points in time.

The two structure-oriented themes – Understanding schools in context and Complexity and opportunity – provide more generalized insights about the nature of elementary schools as organizations. The headteachers in the study found ways to marshal organizational structures in line with their goals, identifying opportunities within the flexible parameters and scope of their schools. They offer clues as to the way different elements such as an institution’s history, size, professional demographics, and the wider educational climate can impact on organizational elements of school culture. These themes highlight the uniqueness of schools as professional environments, and problematize the simple transference of ideas from other sectors. Previous studies have found that knowledge of local cultures enables choice of right strategies (Angelides & Ainscow, Citation2000), and that middle leaders are particularly well-placed to translate initiatives for their school contexts (Nehez et al., Citation2022). This finding links to a common thread throughout the interviews relating to the idea of developing teachers as cultural leaders. The headteachers conceptualized the school structure as one in which classrooms constituted spaces where teachers not only led the learning of children, but also provided direction to support staff and parents. In wider conversations around the leadership of teachers, their ‘sphere of influence’ outside the classroom is often considered in relation to pedagogical or subject leadership (Gul et al., Citation2022), or in terms of research engagement (Reid et al., Citation2022) rather than in terms of structural actors within an organization’s professional culture. Yet, teachers can also act as a figurehead with educational responsibility for part of the community, directing both adults and children connected to their classroom:

They’re all leaders. But their leadership role may be within a smaller sphere […] you have a team around the children and the teacher is part of that team and is leading that team, but there’s a group of other adults who are all involved. And the teacher knows they have to manage there, and lead their work as well.

The framing of the teaching role as involving leadership within the classroom has further implications for the training of teachers and wider discourses around education. Indeed, despite the potential of school and classroom culture to be transformative, policy has paid little attention to the cultural and communal significance of primary schools (Alexander, Citation2010), and many teachers do not typically view or position themselves as leaders (Meredith, Citation2007).

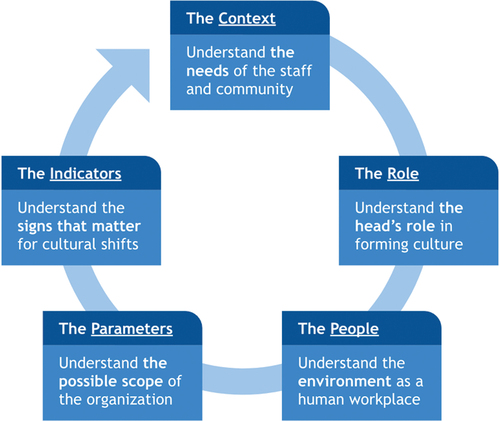

The study has highlighted five areas of significance for practitioners’ reading and understanding their own elementary school organizations. Each of these five areas can be considered active and constantly shifting in response to internal and external forces. As noted by the headteachers, shifting circumstances in one area – for example, a new hire, changing local demographics, or the implementation of an initiative – can alter the status quo in others. School leaders must therefore attend to their them in an iterative manner as their organization progresses. The five themes captured by the study can be used to construct a practical framework (see ) for practitioners to approach the analysis of their own school organizational culture. Social and relational aspects, such as the interpersonal dynamics within the environment, the indicators affecting culture, and the orientation of the headteachers’ role interact with structural elements such as the parameters of the school organization and the context. The codes identified as indicators of professional culture may be particularly useful for practicing headteachers as barometers of organizational health. Furthermore, the five themes can scaffold and contextualize informal knowledge for more effective socialization and coaching of new headteachers or middle leaders within schools. They also provide new avenues for future research to explore and build upon.

Conclusion

In a climate of education characterized by high-stakes accountability and resistance from schools (Clarke, Citation2023), a focus on student attainment as a key metric of success has been more prevalent than, and has unintended consequences for, our understanding of the complex network of factors affecting schools’ long-term success as organizations (Gobby et al., Citation2022; Moore et al., Citation2002). The forms and application of knowledge explored in this article may help to balance our understanding of the complex interplays of factors affecting schools. The findings relating to organizational factors in schools are significant, and no doubt play a role in wider educational debates, given the widespread recognition of the importance of working conditions in fostering school and teacher development (Department for Education [DfE], Citation2018; Flores, Citation2004; Madigan & Kim, Citation2021; Williams et al., Citation2001). In developing our understanding of schools as organizations, there also lies the potential to increase the collective success of practitioners in education in reaching the shared goals of their schools. This includes a better understanding of the impacts affecting school structures, and encourages acknowledgment of the importance of the relationship-oriented elements of school leadership.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Richard D’Souza

Richard D’Souza is an Associate Supervisor and PhD Research Student at the University of Exeter’s School of Education. His research areas are educational leadership, the assessment of creativity in childhood, and links between marginalization and youth violence.

References

- Alexander, R. (2008). Essays on pedagogy. Routledge.

- Alexander, R. (Ed). (2010). Children, their world, their education: Final report and recommendations of the Cambridge primary review. Routledge.

- Anderson, J. R. (1980). Cognitive psychology and its implications. W. H. Freeman.

- Angelides, P., & Ainscow, M. (2000). Making sense of the role of culture in school improvement. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 11(2), 145–163. https://doi.org/10.1076/0924-3453(200006)11:2;1-Q;FT145

- Arts, J. A. R., Gijselaers, W. H., & Boshuizen, H. P. A. (2006). Understanding managerial problem-solving, knowledge use and information processing: Investigating stages from school to the workplace. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 31(4), 387–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2006.05.005

- Baker, J. A. (1998). The social context of school satisfaction among urban, low-income, African-American students. School Psychology Quarterly, 13(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088970

- Baker, J. A., Dilly, L. J., Aupperlee, J. L., & Patil, S. A. (2003). The developmental context of school satisfaction: Schools as psychologically healthy environments. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(2), 206–221. https://doi.org/10.1521/scpq.18.2.206.21861

- Ball, S. J. (2008). The education debate. Policy Press.

- Barker, B. (2005). Transforming schools: Illusion or reality? School Leadership & Management, 25(2), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430500036215

- Barker, J., & Rees, T. (2020). Developing school leadership. In S. Lock (Ed.), The ResearchEd guide to leadership: An evidence -informed guide for teachers (pp. 45–58). John Catt Educational Ltd.

- Bereiter, C., & Scardamalia, M. (1993). Surpassing ourselves: An inquiry into the nature and implications of expertise. Open Court.

- Berg, G., & Wallin, E. (1982). Research into the school as an organization. II: The school as a complex organization. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 26(4), 161–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/0031383820260401

- Blossing, U., & Liljenberg, M. (2019). School leaders’ relational and management work orientation. International Journal of Educational Management, 33(2), 276–286. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-07-2017-0185

- Bossert, S. T. (1988). School effects. In N. J. Boyan (Ed.), Handbook of research on educational administration (pp. 341–352). Longman.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 2. 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brookover, W. B., Schweitzer, J. H., Schneider, J. M., Beady, C. H., Flood, P. K., & Wesienbaker, J. M. (1978). Schools, social systems and student achievement. American Educational Research Journal, 15(2), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312015002301

- Cambridge Dictionary. (n.d.). Organization. Dictionary.Cambridge.org Dictionary. Retrieved April 1, 2023, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/organization.

- Charmaz, K., & Thornberg, R. (2021). The pursuit of quality in grounded theory. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 305–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1780357

- Chi, M. T. H., & Ohlsson, S. (2005). Complex declarative thinking. In K. J. Holyoak & R. G. Morrison (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of thinking and reasoning (pp. 371–399). Cambridge University Press.

- Clarke, V. (2023). School leaders’ union could take Ofsted to court after Ruth Perry’s death. BBC. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-65140375.

- Connolly, M., James, C., & Fertig, M. (2019). The difference between educational management and educational leadership and the importance of educational responsibility. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 47(4), 504–519. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143217745880

- Dalin, P. (1994). School development: Theory book 2. Liber Utbildning.

- Day, C., Hall, C., & Whitaker, P. (1998). Developing leadership in primary schools. Paul Chapman Publishing Ltd.

- Day, C., Harris, A., Hadfield, M., Tolley, H., & Beresford, J. (2000). Leading schools in times of change. Open University Press.

- Department for Education. (2018). Factors affecting teacher retention: Qualitative investigation research report. Retrieved September 23, 2023, from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/686947/Factors_affecting_teacher_retention_-_qualitative_investigation.pdf.

- Earley, P., & Evans, J. (2004). Making a difference? Leadership development for head teachers and deputies – ascertaining the impact of the national college for school leadership. Educational Management Administration and Leadership, 32(3), 325–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143204044420

- Elmore, R. (2004). School reform from the inside out: Policy, practice, and performance. Harvard Education Press.

- Fernandez, A. (2000). Leadership in an Era of change: Breaking down the barriers of the culture of teaching. In C. Day, A. Fernandez, T. E. Hauge, & J. Møller (Eds.), The life and work of teachers: International perspectives in changing times (pp. 239–255). Falmer Press.

- Flores, M. A. (2004). The impact of school culture and leadership on new teachers’ learning in the workplace. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 7(4), 297–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360312042000226918

- Gaffney, M., & Faragher, R. (2010). Sustaining improvement in numeracy: Developing pedagogical content knowledge and leadership capabilities in Tandem. Mathematics Teacher Education & Development, 12(2), 72–83.

- Garza Jr, E., Drysdale, L., Gurr, D., Jacobson, S., Merchant, B., & Helene Ärlestig, D. (2014). Leadership for school success: Lessons from effective principals. International Journal of Educational Management, 28(7), 798–811. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-08-2013-0125

- Gobby, B., Wilkinson, J., Keddie, A., Blackmore, J., Eacott, S., MacDonald, K., & Niesche, R. (2022). Managerial, professional and collective school autonomies: Using material semiotics to examine the multiple realities of school autonomy. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2022.2108507

- Grint, K. (1997). Leadership: Classical, contemporary, and critical approaches. Oxford University Press.