ABSTRACT

The development of STEM teacher leadership identity empowers K–12 teachers to make changes to improve teaching and learning. Identity development might not be productively supported in all school settings, however. Hence, external professional development programs should offer opportunities to supplement this identity development. We construct and propose a Can’t-to-Becoming-to-Being model to describe STEM teacher leadership identity development as a progression of stages from weak to strong identity. Using interview data over two points in time with 127 STEM teacher leaders, we illustrate four stages of development: Can’t, Can, Should, and Being. We also elucidate the conditions that teachers identify as catalyzing or inhibiting identity development, with attention to the impacts of teacher leaders’ participation in professional development programs. Our findings indicate that the Can’t-to-Becoming-to-Being model is useful for describing how teachers may develop STEM teacher leadership identity and may provide researchers a tool for exploring this process. Professional developers might consider the catalysts (and inhibitors) we identify as a means of strengthening teacher leadership identities in the design and implementation of professional learning. External spaces separate from school communities may offer teacher leaders opportunities to try out provisional selves and provide additional motivation to propel participants to Being teacher leaders.

Introduction

The ways K–12 teachers experience their workplace and engage in professional activities are tied to their sense of satisfaction and willingness to persist in the profession. Teacher satisfaction and persistence are at historic lows (Bailey et al., Citation2021; Hanita et al., Citation2021); the field needs ways to help reverse these disconcerting trends. Teacher leadership – when teachers engage in activities beyond the classroom level to improve teaching and learning – has been pointed to as a means for creating more empowering and validating experiences that improve satisfaction and increase persistence (Barth, Citation2001; Dauksas & White, Citation2010; Reid et al., Citation2022). However, it is likely that the extent to which teachers identify as leaders mediates the positive impacts of their leadership work on their senses of satisfaction and persistence: The more teachers perceive themselves to be functioning as leaders and the more they are supported in leadership efforts, the more they are likely to feel the sense of empowerment that leads to greater professional satisfaction (Angelle & Schmid, Citation2007; Gul et al., Citation2019).

Teachers envision goals for their professional work and for their career trajectories (Hammerness, Citation2008). Often those visions, and their sense of professional satisfaction, are challenged by aspects of their working environment, including their school environment (e.g. agency in classroom decisions as well as professional learning Calvert, Citation2016; Moore, Citation2012). Teacher leadership provides a mechanism for teachers to overcome the challenges of their school workplace and feel a sense of agency and responsibility for their professional learning (Calvert, Citation2016). Therefore, the development of a teacher leader identity can be part of this process of surmounting barriers to creating a productive school culture, while simultaneously meeting teachers’ professional goals. However, while there is research examining the relationship between teacher leader identity development and internal school factors (e.g. amount of involvement in decision-making/school governance; Gonzales, Citation2004), there is little research exploring how external factors – for instance, outside-of-school professional learning projects – might intercede in that relationship. Further, teachers need to actualize their identities as leaders, and the catalysts for shifts from not seeing themselves as teacher leaders to adopting a teacher leader identity are under-specified, including the role of external professional learning projects. Research has focused on identities at specific points in time, rather than studying the shifts and trajectories in teacher leadership identities.

This study looks at data collected over two time points (two years apart) in the professional learning experiences of teachers participating in Noyce Master Teacher projects funded by the National Science Foundation across the United States. Noyce projects have the explicit goal of developing the participants into teacher leaders or supporting their leadership efforts (AAAS, Citation2021). Interviews were conducted at two junctures, with 127 Master Teaching Fellows (MTFs) at the first time point and 94 MTFs (out of the original 127) at the second time point. The goal of this work is to map out the terrain of the complex interactions between the MTFs’ teacher leader identities, their school culture, and the experiences in which they engaged in the Noyce projects. Specifically, we aim to understand how teacher leader identities are transformed and the conditions that contribute to a shifting teacher leader identity.

Literature review

Professional identity

Caza and Creary (Citation2016) suggested that identities are interwoven with ‘the various meanings that are attached to a person by themself and others’ (p. 261, citing Gecas, Citation1982). They extended this general definition to the more-specific construct of professional identity by indicating that this is the image an individual has of oneself within one’s chosen occupation, which includes how they ‘define themselves in their professional capacity’ (p. 261, citing Schein, Citation1978). Caza and Creary suggested that one’s professional identity is substantively a reflection of the way one thinks others perceive oneself in the professional milieu. Most significantly, they noted that one’s professional identity impacts how one behaves in one’s workplace (p. 263).

Our view of professional identity is informed by positioning theory (Harré, Citation2015; McVee et al., Citation2018). As Van Langenhove and Harré (Citation1999) explained it, ‘The act of positioning … refers to the assignment of fluid “parts” or “roles” to speakers in the discursive construction of personal stories that make a person’s actions intelligible and relatively determinate as social acts’(p. 17). Regularities or patterns in the assignment of these parts or roles become what an individual perceives to be one’s professional identity. Relevant to the analysis in this study, it is significant that positioning theory foregrounds discursive actions and the stories that they generate as critical to understanding the evolution of professional identity. Darragh (Citation2015, Citation2016) expanded on this framework by adopting the view that identity is performative. Of particular significance to this study is Darragh’s notion that researchers can track changes in performance over time to trace an individual’s identity development (Citation2015, p. 87).

Our perspective on professional identity is also influenced by Markus and Nurius’s (Citation1986) notion of possible selves and Ibarra’s (Citation1999) subsequent proposal of provisional selves. Markus and Nurius explained: ‘Possible selves are the ideal selves that we would very much like to become. They are also the selves we could become, and the selves we are afraid of becoming’ (p. 954). Importantly, in keeping with other ideas on which we have drawn, Markus and Nurius indicate that, while possible selves are within the purviews of individuals, ‘they are also distinctly social’ in origin (p. 954). Ibarra recognized that one limitation of the possible selves framework is that Markus and Nurius did not specify the processes by which possible selves are constructed and experimented upon. Ibarra described two mechanisms to fill in this gap: role prototyping, using role models to discern appropriate attitudes and actions relative to a possible self, and identity matching, comparing and contrasting the nature of role models with oneself to determine the most viable possibilities (pp. 12–13).

Connections of professional identity with teacher leadership

Poekert (Citation2012), in examining the relationship between teacher leadership and professional development, commented on the thinking of Danielson and Bowman: ‘Both authors agreed that working with colleagues is profoundly different from working with students (Danielson, Citation2007) and that learning to function as leader requires “nothing less than a profound identity shift for contemporary classroom teachers” (Bowman, Citation2004, p. 187)’ (p. 174). Poekart was asserting that having a teacher identity is not the same as having a teacher-leader identity, and that the change from teacher to teacher-leader identity requires a significant change in one’s professional identity. This paper will describe specific aspects of that change.

Frost (Citation2012) explored how teacher leadership and professional development can facilitate system change. He connected teachers’ ability to support one another in functioning as leaders with the promotion of one another’s confidence, a process ‘in which the essential message is: “people like us can solve problems like this”’ (p. 219). He suggested that this support included the related ‘idea that “we ought to do something about this”’ (p. 219). The two elements Frost identified can be captured as (a) the belief that I can be a teacher leader and (b) the sense that I should act as a teacher leader.

Collay (Citation2006) noted that changes in professional identity related to becoming teacher leaders was associated with ‘persistent tensions as they [teacher leaders] struggle with perceived authority’ (p. 134). Later, citing Zinn’s (Citation1997) work, Collay outlined three categories of supports and barriers influencing a teacher leader’s identity: (a) conditions within the educational context, (b) conditions outside the educational context, and (c) internal factors (p. 142). Importantly, related to outside contexts, Collay suggested that it is composed of ‘primarily the encouragement of family and friends’ (p. 142). A critical aspect of this study is to look more closely at conditions outside the educational context in relation to the role of the Noyce programs in teacher-leader identity development.

Factors affecting teacher leader identity development

As noted above, Collay (Citation2006) associated persistent tensions with teacher-leader identity development. Beech et al. (Citation2012) elaborated on this connection, by specifically recognizing tensions associated with three forms of identity development (or identity work). Two are relevant to this study: (a) enacting aspirational identities and (b) production of hybrid identities (p. 45). The tension from aspirational identities comes from the visible desire in the person for change. This tension has implications for teachers who are envisioning possible (aspirational) selves as teacher leaders and, in so doing, are anticipating the changes through which they will have to go to realize those possible selves. Beech et al. recognized that hybrid identities require different positionings at different times with the same people (p. 46), and these shifts are at the core of this tension. Since teacher leaders often find themselves in hybrid positions (Margolis, Citation2012), this tension becomes ingrained in their work.

Huggins et al. (Citation2017) also identified tensions associated with teacher leader identities. They indicated that professional developers must support teacher leaders in addressing these tensions, and one means for doing this is to appropriate the three modes of belonging described by Wenger (Citation1998): engagement, imagination, and alignment. Huggins et al. (Citation2017) noted that, beyond positioning participating teachers as leaders, the professional development programs had to also involve the teachers in joint enterprises with shared goals to encourage engagement, allow the teachers opportunities for deeper reflection to promote the imagining of new meanings and leadership practices, and provide pathways for teachers to align leadership approaches developed in the program with leadership efforts in their schools (pp. 31 and 43).

Sinha and Hanuscin (Citation2017) associated teacher leader identity development with the amount of alignment between individual’s (a) leadership views, (b) leadership practices, and (c) identities (conceptualized as a combination of social roles and role identities). Their case study of three teacher leaders led to the proposal of three assertions related to the teacher leaders’ identity development: ‘teachers widen leadership views as they develop as teacher leaders; teachers expand their scope of leadership practices as they develop as leaders; and teacher leadership trajectories depends on the priorities of the teacher and her/his context’ (p. 367). It is important to note that the case studies from which these findings were generated seemed to be embedded in single communities of practice (CoP) even though the authors did not use this lens. Wenner and Campbell (Citation2018) constructed a teacher-leader-identity framework that delineates thin and thick teacher leadership identity; a critical condition determining the thickness of teachers’ leader identity is the way in which they enact their identity across different CoPs. Those with thick identities enact them in similar ways across different CoPs, perhaps due to an alignment of their beliefs and views with the ways in which they participate in these CoPs.

Summarizing the literature reviewed, it is clear that systemic tensions and professional alignments are critical driving factors in teacher-leader identity development. These tensions and alignments relate to several categories of factors as identified by Zinn (Citation1997) and Collay (Citation2006). The specific nature of these tensions and alignments was described by Sinha and Hanuscin (Citation2017), who showed how they arise within a single CoP, and by Wenner and Campbell (Citation2018), who explained how they occur across CoPs. Our study involves teachers operating across multiple CoPs, including ones (the Noyce programs) that are external to the school system. Thus, our study contributes to the progression in the literature on teacher-leader identity development.

Conceptual framework

Together, Wenner and Campbell’s (Citation2018) notion of thin and thick teacher leadership and Sinha and Hanuscin’s (Citation2017) ideas concerning the relationship between views, practices, and identities provide useful frameworks for understanding teacher leadership within the context of one or more CoPs. However, Wenner and Campbell do not address the factors that catalyze changes in leadership identities; Sinha and Hanuscin (Citation2017) focus on identity changes catalyzed by evolution in beliefs or practices. Furthermore, Wenner and Campbell (Citation2018) suggest their framework, while an improvement over past models, is not positioned to guide professional development that can support teacher leaders’ professional learning. Thus, we expand on these frameworks by introducing consideration of CoPs external to school environments to incorporate professional learning into identity development.

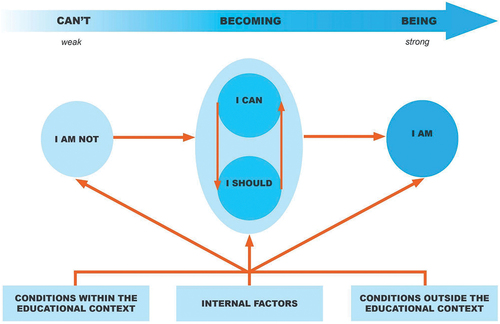

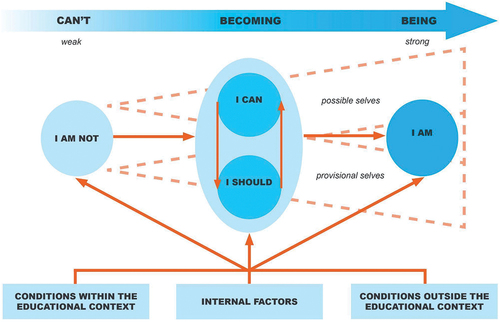

We propose viewing teacher leadership identity as developing from a stage of non-identity or weak identity (‘I am not a teacher leader’ or ‘I can’t lead in this space’) to a stage of strong identity (‘I am a teacher leader in this space’) by advancing through an intermediate stage of becoming a teacher leader that involves the interplay between saying ‘I can lead’ and ‘I should lead’. We frame teacher leadership identity development as a progression from Can’t-to-Becoming-to-Being teacher leaders.

Can’t stage: non- or weak identity

Teacher leaders in the Can’t stage are characterized by those who feel they are not ready to lead in a particular space or are restricted by their professional environment. We aim to identify this array of possibilities for restricted leadership, which may include a teacher leader’s internal sense of competency or external factors such as the lack of resources or support within one’s environment. Teacher leaders in this stage do not envision a possible self in which they are able to lead in their current context.

Becoming stage

Teacher leaders in the Becoming stage are developing the belief in/capacity to envision who they would like to be as leaders (possible selves) and ways in which they can test the potentialities of their leadership roles (provisional selves). Teacher leaders in the Becoming stage position themselves and/or are positioned as teacher leaders through recognition of their ability to lead – and/or by viewing themselves as someone who should lead. Thus, this stage involves two components: having a sense that one can lead and having a sense that one should lead. Note that these components are not necessarily linear. Whereas some teacher leaders may develop a sense of competence to lead before a strong sense of obligation, others may begin with a sense of obligation to lead and then develop a sense of competence toward fulfilling that obligation.

Can component

In relation to the Can component, teacher leaders may recognize their ability to lead, but this recognition may be context specific (‘I can lead in certain settings but not others’). Furthermore, with this component, teacher leaders are likely to at least partially view their own knowledge, efforts, and skills (competencies) as valued, valuable, or effective. However, they may also view themselves as deficient in some of their leadership-related competencies.

Should component

Regarding the Should component, an obligation to lead can be born from myriad factors, including conditions within their educational context or school system, conditions outside of their school system, and internal factors such as their beliefs, motivations, and values. Although school systems may provide structures for leadership (e.g. leadership positions such as instructional coach) to compel teachers to lead, it is not these structures that provide the underlying motivation to engage in leadership – it is the individual’s own commitment to the professional work of supporting peers, ensuring equitable learning for all students, improving the school as a whole, etc., that generates the drive to lead. Additionally, it should be noted that the Should component does not mean that teacher leaders are acting as teacher leaders at all times in every context. The Should component implies that, although teacher leaders in the Becoming stage may feel compelled to lead, they may also prioritize their leadership efforts based on their own understanding of their capabilities and the needs and goals of their education systems.

Being stage: strong identity

Teacher leaders in the Being stage have a strong teacher leadership stance, or ‘way of thinking and being’ that prioritizes student needs and spurs colleagues to improve their teaching (Hunzicker, Citation2017, p. 1; Smulyan, Citation2016). Teachers operating in this stage have attained some ideal or close to ideal version of their possible selves. They have goals for who they want to become as a leader and this creates a strong sense of responsibility to function in a leadership capacity. Further, teachers in the Being stage would have a stronger sense of their leadership being context independent: They will believe they can and should lead in various ways and in various environments. Like the Should component, teacher leaders in the Being stage do not act as teacher leaders in every context. Rather, they use their understanding of their school system and their own capabilities and interests to identify leadership efforts that they can best support.

Catalysts and inhibitors of identity change

In we use boxes and arrows to represent multiple personal, contextual, and external factors that can either catalyze or inhibit movement of teacher leaders along the Can’t-to-Becoming-to-Being progression. These factors are organized into three categories as suggested by Zinn’s (Citation1997) sets of supports and barriers to teacher leadership: conditions within a teacher leader’s educational context, conditions outside the teacher leader’s educational context, and internal factors. Conditions within a teacher leader’s educational context include relationships with peers and administrators, formal leadership roles, and resources. Conditions outside the teacher leader’s typical educational context can include relationships with friends and family, but for this study we highlight external communities of practice – the Noyce projects in this case – as a key potential catalyst for change. Several internal factors, or dispositions (e.g. beliefs, values, attitudes), may catalyze or restrict movement along this progression, including a teacher leader’s self-efficacy. Such internal factors are critical to understanding where a teacher leader is in the Can’t-to-Becoming-to-Being progression. For instance, a teacher leader who is active in teacher leadership efforts may not have an internal recognition of their own ability to lead that reflects their achievements, and is thus not necessarily operating at the Being stage. A focus of this paper is to more clearly elucidate differences between stages along the Can’t-to-Becoming-to-Being progression, as well as identify factors catalyzing or inhibiting this progression.

Purpose and research questions

Although our hypothesized framework in the Can’t-to-Becoming-to-Being progression is grounded in research literature about professional identities and identity development, literature that directly investigates STEM teacher leaders’ development through a particular progression appears scarce. The field needs models for STEM teacher leadership identity development as a step toward understanding how to support such growth. The goal of our study was to explore how this model accounts for STEM teacher leaders’ identity development descriptions, including catalyzing or inhibiting factors.

How does the Can’t-to-Becoming-to-Being model capture STEM teacher leadership identity development?

What are the catalysts and inhibitors associated with STEM teacher leaders’ identity development, including the impacts of their participation in an external professional development program?

Methods

This phenomenological study is part of a larger project built around a multiple case study approach to understanding nine professional development projects that developed and/or supported STEM teacher leaders. The nine projects, all funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Robert Noyce Teacher Scholarship Program’s Track 3 Master Teaching Fellowships, all used cohort models and included foci on increasing participants’ content knowledge, pedagogical knowledge, leadership expertise, and leadership activities (Yow et al., Citation2021). One of the original project’s research interests was the impact of professional learning models used in Noyce projects on professional identity development of the MTFs. The current study derives from this focus, exploring the phenomenon of STEM teacher leadership identity development.

Context and data collection

The teacher leaders each participated in a Noyce MTFs project, which required them to engage in project activities and remain in a high-need district for five years; at the time of this study, some of the Noyce projects had concluded, and while all MTFs remained in education, some had shifted out of the classroom to engage in wider leadership efforts, such as math/science district coach. This study utilizes data from seven of the nine Noyce projects involved in the Multi-site (pseudonym) Project; key characteristics of those projects are found in . Pseudonyms indicate each project’s geographic region and content focus (math, STEM, or math and science [M&S]). The research team (including faculty, postdocs, graduate students, and undergraduate students) for the Multi-site Project collected and analyzed interview and survey data across three school years (2018/19–2020/21), during which three of the Noyce projects were still active and four were completed. All participants reported on in this article provided consent to participate in the project and to have the results of data collection shared publicly. This study was approved by University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s institutional review board under IRB#: 20180218105 EX.

Table 1. STEM teacher leader program details.

For this study we analyzed interview data from 127 MTFs in 2018–19 (year 1) and 94 MTFs in 2020–21 (year 3). Interviews lasted 45–60 minutes and were conducted in person (some in year 1) or via Zoom (some in year 1, all in year 3). The interviews were recorded and subsequently transcribed via automatic transcription software. The 2018–19 interviews used a common protocol that partially evolved after interviewing all of the MTFs from one project; the 2020–21 interviews had a similar common protocol with additional questions that built upon participants’ responses from the first set of interviews. Interview questions asked MTFs to describe their professional trajectories, experiences with Noyce, school contexts, professional identities, teaching (year 1 only), leadership opportunities, and equity in the context of education (year 3 only). An example interview question for each of these concepts can be found in Appendix A. Questions about professional identity focused on how participants saw themselves as teacher leaders, how others saw them as teacher leaders, and changes in this positioning.

Data analysis

The Multi-site Project iteratively developed a codebook to analyze the interviews. Codes were both structural (stemming from the Multi-site Project’s research questions and interview protocol) and grounded in relevant leadership and identity theories (DeCuir-Gunby et al., Citation2011; Miles et al., Citation2014). The main codes were sorted into categories (the concepts listed in Appendix A); sub-codes helped to define and delineate the main codes. See Appendix B for the final codebook. In both years 1 and 3, researchers from across all the collaborative sites coded some transcripts independently and then met to reconcile the codes, achieving 100% agreement. Subsequent coding was done in teams of two to four researchers, who each independently coded, then met to reconcile codes as teams to achieve 100% agreement. When appropriate, the smaller research teams brought issues they encountered to the full research team during monthly meetings to clarify code definitions and applications.

There were three professional identity codes that encompassed the development of leadership identities: Becoming (statements about possible selves and MTFs’ perceptions of themselves as leaders), Agenting (actions MTFs planned or took that demonstrated them functioning as leaders), and Re-acting/Responding (changes in identity or leadership activities; how MTFs navigated barriers to desired leadership activities). Throughout our coding and analysis process, we did our best to interpret MTFs’ identities as they perceived themselves, rather than try to label MTFs as we saw them. For example, we coded transcripts in deliberately selected groups of two to four people, some of whom were familiar with the MTFs and some who were not. Thus, those familiar with the MTFs and projects added contextual knowledge, while those who were not challenged preconceived assumptions about MTFs, thus ensuring that interpretations focused on what the MTFs said in interviews, rather than how MTFs may be perceived by members of the research team. To further address researcher bias, we sought out disconfirming evidence when research members presented hypotheses for making sense of teacher leaders’ identities.

Excerpts labeled with the professional identity codes were extracted and summarized for each MTF to describe their leadership identity development, with particular attention paid to: who MTFs were becoming as teacher leaders and what or who helped them get there; catalysts and inhibitors in their leadership; and influence of internal (school) and external (Noyce) contexts. We also re-read all transcripts to look for influential factors on leadership identities not already captured by the professional identity codes, such as the impact of professional networks or the influence of colleagues. MTFs statements about their general affect, self-efficacy, confidence, or dispositions toward leadership were not always clearly connected to a specific environment (their school in general, a school committee, or Noyce). Hence, we sometimes describe an MTF as having evidence of operating in a particular stage more generally, rather than ascribing their progression to a specific educational context. Further, we approached the applicability of the conceptual framework to describe leadership identity trajectories with skepticism, taking an open-minded researcher stance seeking to determine whether the data could appropriately be represented by the conceptual framework.

Findings

Our goal is to describe the development of STEM teacher leaders’ professional identities, as well as to describe the catalysts and inhibitors associated with their development. First, we discuss the ways in which MTFs operated in these stages of identity: (a) Can’t: I Am Not a Leader, (b) Becoming: I Can Lead and I Should Lead, and (c) Being: I Am a Leader; we present vignettes of MTFs in each of these stages. Second, we highlight the personal, contextual, and external factors that catalyzed or inhibited MTFs’ transitions from one stage to another. We especially consider the ways in which the Noyce projects functioned as an external factor. Note that our goal was not to definitively characterize MTFs’ identities – identities are fluid – but to understand the nature of these stages and how shifts in identity manifest.

Can’t: I am not a leader

Given that the MTFs had applied to participate in a teacher leadership project, few MTFs operated in the Can’t stage. However, some participants interviewed in year 1 demonstrated evidence of operating in a stage of Can’t due to internal factors, but progressed to the Can component by their second interview in year 3. For example, by year 3, MidwestSTEM01 still felt ‘scared’ to assume formal leadership roles, but saw the value in the more ‘fluid and relaxed’ ways in which they could and chose to lead informally. Thus, some MTFs operated in the Can’t stage due to internal factors, but most transitioned to operating in the Can component in the right school contexts.

For the remainder of this section, we focus on the experiences of one MTF who felt that they could not lead in their school environment to showcase the nuanced ways in which they were hindered from progressing to the Can component within their school community. SoutheastMath01, an elementary school teacher, said their participation in conferences made them feel like ‘more of a professional’, and Noyce helped them feel secure in their abilities as a mathematics teacher. Thus, within the context of Noyce, SoutheastMath01 felt they were developing the efficacy and competence to be in the Can component.

SoutheastMath01’s experiences in Noyce were at odds with their experiences at their school. They described how the Noyce program went against the thought process in their school community. While several teachers at their school could have qualified for the Noyce program, they ‘didn’t want anything to do with it because they felt like what they were doing was fine. They didn’t want change’. In contrast, the people SoutheastMath01 met in Noyce wanted ‘to move forward in their personal learning so that they could get better, [be a better] teacher and a better professional’. When SoutheastMath01 tried to integrate what they learned from Noyce into their school community, they faced significant resistance:

The other math teachers at my school had been teaching the same way for—they’d been there 20 years. And so when I tried to come in and I brought in a tech [anonymized] from [Noyce Project] and [state professional STEM Organization] to come help me introduce some technology to the kids, they were not very receptive … They weren’t interested in learning anything new.

Administration turnover only compounded the barriers that SoutheastMath01 faced; they mentioned that administrators were replaced about every two years, making it difficult for SoutheastMath01 to build relationships. When SoutheastMath01 did continue to try to make changes, administrators removed them from teaching mathematics. SoutheastMath01 explained: ‘I was trying to do something different and so I no longer am part of the math curriculum’. They did attempt to change their position to focus teacher leadership efforts elsewhere, but at the time there were no such positions available, and so they decided to stay where they were.

SoutheastMath01 summarized: ‘Once I got into the [Noyce] program, I really did hope that I would be able to have more influence than just my one classroom. But that never occurred’. SoutheastMath01’s efforts to influence mathematics education beyond their own classroom were blocked; their efforts to enact the possible selves that Noyce had supported them in envisioning were stifled. They were ‘willing to try to make changes, to be a continuing learner’ and were even willing to move to a different position at one point. As such, when faced with significant opposition to their leadership, SoutheastMath01 described feeling ‘very defeated’ and tried to change things until they were ultimately moved out of math by administrators. We characterize SoutheastMath01’s identity within their school community as existing in the Can’t stage, because they ultimately felt defeated and ceased to pursue their leadership agenda.

Becoming: I can lead

In the Can component of the Becoming stage, MTFs’ conception of possible selves within their professional identities expanded to include seeing themselves as teacher leaders, at least in certain contexts. Several MTFs moved or changed roles to support their possible selves since, like SoutheastMath01, they found certain school cultures unconducive to teacher leadership. SoutheastMath02’s ‘stagnant’ school culture led them to change schools. They described it as ‘refreshing’ to work with a new school in which people challenged themselves to grow and immediately began taking on leadership roles. Positioning, self-efficacy, and beliefs about leadership all proved to be critical in transitioning MTFs’ identities toward the Can component. Positioning by others supported several MTFs in gaining the self-efficacy to lead. WesternSTEM01 reflected on how their school featured administrators who listen and where collaboration is valued; this support led to them learning from others in their early years as a teacher and later serving as a mentor for new teachers in their building. When MTFs exhibited a flexible belief toward leadership roles, this flexibility indicated movement toward a stronger teacher leader identity. For instance, MidwestMath01 preferred to lead by example as an informal leader, saying, ‘you don’t have to have a leadership title to be a leader’, and that a teacher leader should be someone ‘others look up to in and out of the classroom’. Other MTFs preferred informal leadership roles due to the discomfort they associated with formal roles. This discomfort was caused by (a) a belief that their colleagues were not interested in their leadership vision, (b) a concern with always having to be ‘the one that stands up’ or who ‘has to have my voice heard all the time’ (MidwestSTEM02), and (c) a sense that ‘formal [leadership] is pushing me past my comfort zone’ (SoutheastM&S01).

For the remainder of this section we focus on the experiences of MidwestSTEM03, an elementary teacher who developed a passion for and expertise in teaching science through a STEM-focused Noyce project. Through their experiences, MidwestSTEM03 recognized a need for more science time in their building, yet they did not feel ready to actively advocate for this time. This led to them believing they were not yet a teacher leader, stating ‘I’m getting there. I don’t feel like I am one yet’. MidwestSTEM03 described a teacher leader as someone who could advocate: ‘Somebody who isn’t necessarily afraid to stand up in a meeting and say, “No, it’s not right to only give kids 45 minutes of science when you feel like it”.’ Partly as a result of the support of Noyce, MidwestSTEM03 overcame their reservations and planned to advocate for science by identifying allies:

I’ve kind of been picking other advocates that agree or feel the same way. So then that way, when it’s time for me to stand up and approach the faculty, I have people there beside me, so that it’s not such a terrifying experience. (Year 1 Interview)

MidwestSTEM03’s relationships with peers and administrators allowed them to advocate for science more strongly by year 3 of their time in Noyce, demonstrating a transition from a Can’t stage to Can component of leadership. In particular, MidwestSTEM03 asked their superintendent for a science classroom. Their superintendent responded positively, creating a science specialist position that MidwestSTEM03 obtained. MidwestSTEM03 felt ‘uniquely qualified’ for this position because of Noyce”:I just happened to be uniquely qualified because of my STEM Program through [Noyce] that when I applied and interviewed it, it worked out” (Year 3 Interview).

Becoming: I should lead

MTFs’ growing confidence in their ability to lead and greater alignment of their conceptions of themselves as teacher leaders was often coupled with an internally driven sense of duty to lead. For some MTFs, this obligation manifested through their years of experience. For instance, SoutheastM&S02 and EasternSTEM01 both served as teachers for over 25 years and used this experience to assume a supportive, elder position: SoutheastM&S02 referred to themselves as a ‘patriarch’ in their school, while EasternSTEM01 described themselves as a ‘grandmother’. In contrast, MidwestSTEM04 found that others approached them with leadership opportunities because a younger leader was needed in their school context. MidwestSTEM04 elaborated that they ‘would be the only one who would do it. A lot of them are retirement-age or have small children’. The master’s degree MidwestSTEM04 earned through Noyce also played a role in others seeing MidwestSTEM04 as a leader, and they developed a sense of obligation to lead: ‘I think they know that I’m educated, so they want my opinion’. Similarly, MidwestMath02 began to see themselves as a teacher leader due to the leadership opportunities provided by Noyce, and through these opportunities developed a strong sense of obligation based on their desire to be ‘worthy’, which created a responsibility to ‘pay it forward’:

I think I’ve just had a lot of opportunities. I feel like part of being given those opportunities – part of making myself worthy of having been given those opportunities is to pass along some of the things that I have learned…I’ve been really lucky to have a lot of these opportunities, so I feel I should pay it forward.

Relatedly, Noyce broadened MTFs’ perspectives of teacher leadership and the education systems. Together, MTFs’ expanding views and encouragement toward action enabled some MTFs to move beyond thinking that they can lead to thinking that they should or have a responsibility to lead. For example, WesternSTEM02 described how their discussions with like-minded, respected teacher leaders in Noyce supported them to ‘see the bigger picture’ of education. As a result, they felt a sense of responsibility to take on more challenges. SoutheastMath03 had a similar experience through Noyce. Their project reviewed Common Core Standards with teachers from across K–12 grade bands. As an instructional coach, they endeavored to provide a similar experience for the teachers with whom they worked. SoutheastMath03 felt incredibly motivated by Noyce and working with teachers to understand Common Core, saying ‘it was probably one of the best things that happened to my career’. This notion of learning from expert teachers outside of their grade-level was also discussed by other MTFs as an invaluable experience: ‘And I think having all of those voices at the same table adds innovation and a level of problem solving that we would miss out on if it was just one group and not the other’ (WesternSTEM03, Year 3).

Similar to MidwestSTEM03, some MTFs credited Noyce and movement into a formal leadership role with supporting their motivations to lead. For instance, WesternSTEM04 saw themselves as an advocate for students because they worked with English language learners (ELL) in STEM settings, but when they became the department head for English language development at their school, they felt even more empowered as an advocate for students. Their new role enabled them to interact with administration and take on new responsibilities regarding student advocacy. WesternSTEM04 identified Noyce as a key factor in developing their confidence, specifically benefiting from conversations about ‘voice and advocacy’ with their peers in Noyce. This example additionally illustrates that multiple interrelated motivations may be at play in engendering a sense of obligation to lead: WesternSTEM04 had an internal drive to support ELLs, was supported by Noyce in seeking formal teacher leadership, and was provided a position in their school.

Being: I am a leader

MTFs with strong teacher leader identities clearly articulated their knowledge and skills as teacher leaders in supporting students and colleagues, the dispositions they believed made them effective, their motivations for leadership, and portrayed a strong sense of agency in their leadership. Several MTFs in this stage persevered through significant contextual challenges to both support student success and motivate colleagues to transform their educational practice. MidwestMath03 described having to ‘fight the cultural tide’ when they were first hired, to improve the mathematics department culture (toward prioritizing student learning), and they recounted numerous times that they worked directly with the school board to improve and professionalize the mathematics curriculum and provide more opportunities for students. MidwestMath03 described an internal factor – resiliency—that played a major role in their leadership identity: MidwestMath03 overcame many challenges in their life (including growing up in a single parent household) to excel academically and as a teacher (e.g. becoming a state teacher of the year).

MTFs’ internal motivations and dispositions, such as MidwestMath03’s resilience, were often complemented by the external motivation and validation that Noyce provided. MidwestMath03 expressed this complementarity through shared experiences with other MTFs in response to a question asking MidwestMath03 to identify those who have had the greatest positive influence on their perspective of mathematics:

[Noyce project leaders] have been instrumental in the opportunities I’ve been afforded and a lot of the fanfare that I enjoy has a lot to do with stuff they’ve done. But that first experience this summer, where they paired us up with roommates… I mean isolationism in teaching is not something that’s surprising. It happens to a lot of teachers in a lot of places, but to be a mathematics teacher, a STEM teacher in a rural community … to be in such a remote area and to find people that are just like you, to know that there are other people out there that have the same passion and drive and vision, but also the same struggles…we [MidwestMath03 and three other MTFs] were viewed as the best mathematicians in the class. And so that alone was also a big feather in the cap, you know, validation. (Year 1 Interview)

In some instances, however, instead of complementing the internal nature of an MTF in relation to teacher leadership, Noyce transformed their nature, such as WesternMath01’s nature:

And, brave. I think it’s made me braver because … I’m the person that’s in the corner in the party that if you don’t notice me, that’s just totally fine with me. So, this [Noyce] has made me feel a bit more out there, which has been very hard, but also very rewarding. (Year 1 Interview)

Noyce challenged and supported WesternMath01 to move past the limitations that their introverted nature was placing on their possible leadership selves. Like MidwestMath03, some of this empowerment manifested because of the validation they felt and the professional network they established through Noyce: ‘I think it’s given me a lot of clout. I think it’s also given me a lot of connections’. Crucially, this empowerment also supported WesternMath01’s retention within the teaching profession: ‘I think without my exposure to other people from other places through Noyce, again, I don’t think I would’ve stayed in teaching’. Notably, MTFs in the Being stage experienced professional satisfaction through alignment of ideal self and possible selves, which, in turn, supported MTFs’ retention in the classroom and as a leader. For instance, when asked what their ideal teacher leader position looked like, SoutheastMath04 said ‘I’m pretty much in it right now’ and described how their experiences in Noyce inspired them to ‘move math forward’ and kept them from retiring – ‘I’m in it to make a difference. That’s what drives me’.

MTFs who primarily operated in the Being stage believed they could act as leaders in multiple contexts. Before Noyce, some MTFs believed they could lead inside their school environments, but questioned if they could lead in broader spheres of influence outside of their schools. For example, SoutheastMath04 was challenged by Noyce to lead in increasingly larger spheres of influence. Through their coach role they supported around 40 teachers; once they moved into a math specialist role they described being able to ‘work in whole regions of the state of [anonymized]’. The experiences of Noyce that allowed the MTFs to expand their spheres of influence may have produced a more generalized sense of themselves as teacher leaders. MidwestMath04 provides evidence for this conjecture:

I think that Noyce really pushed me to think about leadership roles and how to kind of be the person that jumps out in the forefront and ‘I’m gonna try this, I’m gonna do this’. Like I see myself as one of the innovators on campus … But then I feel like [as] those [different leadership] opportunities grew for me, I became more comfortable with seeking them out and volunteering for them after being able to do some of those things through Noyce. (Year 3 Interview)

Some MTFs in the Being stage further described having an internal sense of legitimacy to lead, rather than relying on others to grant them leadership authority, and thus felt agency to try on provisional selves in their context to enact changes. Some developed this sense of agency through Noyce. For example, during their first year of Noyce participation MidwestMath05 explained that, even with 17 years of experience, they were the ‘youngest math teacher in the school’, and as such, they didn’t feel their opinions carried weight with the other math teachers. However, Noyce helped MidwestMath05 feel ‘validated as a teacher leader’ and they began to more confidently express their leadership views. By year 3, MidwestMath05 said, ‘I have given myself the permission or authority to make those professional decisions in my classroom and try and pass that authority off to my peers’.

Catalysts and inhibitors for change

Participants identified multiple catalysts and inhibitors of their STEM teacher leadership identity. In we summarize these findings, based on a count of how many participants identified each catalyst or inhibitor. The catalysts and inhibitors spanned the categories of supports and barriers described by Zinn (Citation1997): conditions within the educational context, conditions outside the educational context, and internal factors. Note that although some factors are easily categorized using Zinn’s framework (e.g. resistant colleagues refer to conditions within the educational context), others were less readily categorized (e.g. Noyce provided a network of colleagues for MTFs outside of their typical educational context, but also impacted internal factors such as their confidence or sense of obligation to lead).

Table 2. What were the catalysts or inhibitors for teacher identity development identified by MTFs?.

Some of these factors were identified as supportive (such as involvement in professional organizations, internal drive to grow, prior professional development participation); others were challenges (unsupportive district/school/administrators/colleagues, impact of COVID and other crises); and still others were mixed (leadership positioning as formal vs informal, and involvement in graduate school/advanced degrees). When participants discussed Noyce, they typically described Noyce as a catalyst for change. The second most frequently cited factor was the negative impact of districts and schools that were resistant to changes that the teacher leaders sought to enact, and lack of valuing teacher leaders’ contributions. Whether school contexts were conducive to MTFs seeing themselves as teacher leaders played a significant role as to whether they were operating in the Can’t stage or Can component. Nonetheless, most of the MTFs with appropriate internal qualities (e.g. resilience) or the proper kind of support from Noyce were still able to strengthen their teacher leadership identities.

Some MTFs saw formal leadership titles as making them more of a teacher leader in the eyes of others (or their own eyes). Formal titles can provide credibility that a person is indeed a leader, which pushed some MTFs further along in the Can component or Being stage. For instance, SoutheastM&S03 was comfortable with both formal and informal leadership roles and saw their formal leadership title of department chair as providing them with the authority to do what they needed to do. However, one issue that was identified in this area was the existence of role ambiguity (Ziegert & Dust, Citation2021) related to formal leadership roles. When asked if the nature of their work as a teacher leader was clearly defined, WesternMath02 stated, ‘There is a job description, but nobody adheres to it because there’s this mushy area’. Later, WesternMath02 clearly tied this ‘mushiness’ to the whims of the administrator overseeing their teacher leader work: ‘So, even though there is a job description, it’s how she [administrator] feels on any given day as to whether I get to do something or whether I don’t get to do something’.

MTFs also cited internal catalysts for change, particularly feeling driven to always be learning and growing as a teacher and leader. For instance, SoutheastM&S04 had an internal drive to grow: ‘You can’t always be stagnant, like you can’t be at one place … we’re always continuously growing and learning ourselves’. Noyce fed into this growth mind-set and provided structured and sustained professional learning opportunities. WesternSTEM05 discussed the desire to challenge themselves as a key reason they sought out opportunities provided by Noyce, and the growth supported by Noyce led MidwestMath06 to being positioned as an expert and leader in many education-related technologies after the pandemic began.

All of the Noyce projects recruited MTFs in cohorts and involved graduate coursework, along with expectations to engage in leadership activities (e.g. attending/presenting at conferences, engaging in educational research). Several features played a role in the MTFs recognizing Noyce as a catalyst for their leadership development; quantifies the extent to which certain features of Noyce were identified by the MTFs.

Table 3. How did Noyce function as a catalyst for change?.

The professional community created by the structure of Noyce cohorts was the most significant catalyst for leadership identity development. Many of the teachers (across rural and urban settings) discussed prior feelings of professional isolation, and that Noyce let them ‘meet other people that are headed in the same direction and want the same thing’ (SoutheastMath02). The Noyce cohorts provided a network of colleagues who reinforced one another’s leadership identities. WesternSTEM04 engaged in action research as part of Noyce, which ultimately helped them feel they had ‘voice and advocacy’ to have a broad impact on their school. EasternSTEM02 discussed how they grew as a leader through helping to design and implement courses for pre-service teachers: ‘I thought that with my knowledge I might be able to help … the colleges teach teachers what it is they need to know, trying to improve that program, so that’s kind of what I decided would be my niche’. Several MTFs shifted into higher education positions after their Noyce programs ended, citing their desire to have a bigger impact by preparing the next generation of teachers.

The expectation for MTFs to attend and present at national conferences enhanced their leadership identities; SoutheastMath01 attributed this to being made to ‘feel like a professional’, and SoutheastMath05 noted that presenting at a conference ‘pushed me out of my comfort zone’. Engaging in challenging coursework also led MTFs to view themselves as knowledgeable and well-positioned; SoutheastMath06 stated that, ‘People would respect what I had to say because I did have that knowledge’. Similarly, MidwestSTEM05 felt that completing a master’s degree as part of the Noyce program validated them as leaders, giving them the confidence that their opinion was ‘valid, or worthy’.

Overall, participation in a Noyce program was the most salient factor in catalyzing MTFs’ leadership identities; other catalysts included prior professional development, leadership positioning, and internal motivation for professional growth. Conversely, school systems were the most-often-cited factor inhibiting their leadership development.

Discussion

Critical to strengthening the scholarship around teacher leadership is the development of an understanding of the process of becoming/being a teacher leader (Poekert et al., Citation2016; Smylie & Eckert, Citation2018). It is incumbent on those trying to conceptualize such a framework to consider the factors that intercede in this developmental process – either to support or to inhibit it. Among the factors that have been identified are (1) egalitarianism, which often inhibits teacher leadership (Carver, Citation2016); (2) hierarchical vs. distributed leadership (Bush & Glover, Citation2014; Lumby, Citation2013); (3) lack of understanding of different teacher leadership opportunities, including formal vs. informal roles (Fairman & Mackenzie, Citation2015; Jacobs et al., Citation2016); and (4) the related organizational issues of role ambiguity and role conflict (Bowling et al., Citation2017).

Complicating factors such as these is the issue that transitioning from teacher to teacher leader represents a profound identity shift (Bowman, Citation2004; Poekert, Citation2012). This would suggest that there are additional factors at work in determining how it unfolds – or whether it happens at all. In our literature review, we traced a conceptual path from Zinn’s (Citation1997) and Collay’s (Citation2006) three categories of factors that influence teacher-leader identity development, to Sinha and Hanuscin’s (Citation2017) framework that emphasized alignment between an individual’s views, practices, and identities in impacting this development, and, finally, to the model of Wenner and Campbell (Citation2018), which focused on alignment between the activities within a teacher leader’s different communities of practice. The model presented in this paper seeks to build on that conceptual lineage, but adding to those previous efforts’ consideration of (a) movement from Can’t to Can to Should in the overall shift from not being to being a teacher leader and (b) the influence of an external (to school systems) CoP on these different movements. In this section, we use the Findings to expand on this model, thus addressing our two research questions.

Consideration of Research Question 1:

How does the Can’t-to-Becoming-to-Being model capture STEM teacher leadership identity development?

The Can’t-to-Becoming-to-Being model paints a broad picture of how teacher leaders’ identities shift within the multiple contexts and communities of practice (CoPs) in which they operate. Crucially, our model foregrounds the interplay between both external/social factors (e.g. nature of different CoPs) and internal/cognitive factors (e.g. self-efficacy) in the development of teacher leadership. Here we elaborate on the nature of the stages based on insights from our findings.

Some MTFs in the Can’t stage did not yet identify themselves as efficacious or competent enough to lead, while others did not have adequate resources or support to achieve their desired leadership goals. Hence, MTFs who did not feel they could lead occupied two (potentially overlapping) categories: (1) perceived inability to lead due to external influences and/or (2) perceived inability to lead due to internal factors. MTFs in the first category felt that their school system prevented them from displaying their competence—i.e. they expected negative outcomes from their actions (i.e. had inhibitory outcome expectancies; Barth et al., Citationunder review; Williams, Citation2010) – or generally exhibited an external locus of control related to leadership efforts. By-and-large MTFs in the second category progressed to a sense of being able to lead, at least in certain contexts, through their participation in Noyce. Additionally, individuals in the Can’t stage may not see alignment among their views of who teacher leaders are and the opportunities for leadership that are afforded to them.

In the shift from Can’t to Can, teacher leaders’ self-efficacy was integral to the MTFs’ sense of identity and capacity to function as leaders. Friedman and Kass (Citation2002) describe teacher leader self-efficacy as having two components: a teacher’s self-efficacy as a classroom teacher and a teacher’s self-efficacy as a professional member of an organization. They argue that teachers are more likely to be leaders in the classroom, but members (not leaders) in the ‘colleague/administration’ circle (p. 685). Participation in external communities of practice, such as Noyce, could expand teacher leaders’ views on how to function in the colleague/administration circle both through imagining new possible selves and developing the self-efficacy to experiment with provisional selves. External CoPs also may act as supportive networks that allow Becoming teacher leaders to be resilient in the face of internal uncertainties and external challenges as they experiment with provisional selves.

Similarly, shifts toward Should and Being were often prompted by intertwining internal and external factors. We found that MTFs were inspired or driven toward a newfound or reinvigorated sense of responsibility through developing expertise in less familiar areas and engaging in experiences with like-minded peers and program leaders who supported them in seeing the bigger picture (e.g. developing systems thinking). Through Noyce, teacher leaders’ conceptions of school systems and possible selves simultaneously expanded, encouraging teacher leaders to try out newer provisional selves closer to their ideal role or to flexibly adapt their current role to better align with their ideal self. Thus, our model continues to highlight the interplay of internal and external factors toward identity shifts, but also foregrounds the importance of alignment between ideal self and possible self, as well as the importance of a sense of responsibility in the transition to a strong identity.

Recognizing the distinction between self-efficacy being central to the shift to Can and sense of responsibility being critical to the shift to Should represents an evolution in our model resulting from the data analysis. Lauermann and Karabenick (Citation2013) realized the importance of this distinction in their study of German and American pre- and in-service teachers. They asserted that ‘the need to distinguish responsibility from self-efficacy, since the belief that “I can” (i.e. teacher self-efficacy) may not necessarily translate to a sense of “I should” (i.e. teacher responsibility)’ (p. 15) is crucial to understanding how teachers engage in the activities of their profession. Our model extends Lauermann and Karabenick’s (Citation2013) notions of ‘can’ and ‘should’ to teacher leadership. highlights the influences of self-efficacy, a sense of responsibility, and alignment of possible and provisional selves within our model.

How might teacher leaders develop a sense of responsibility? As mentioned earlier, engaging with like-minded peers and program leaders supported teacher leaders in developing systems thinking. This stretched the realm of possibility for teacher leaders’ selves beyond what they previously imagined and inspired them to similarly expand their activities in closer alignment with their ideal selves. At the same time, we found that many teacher leaders gained credibility and felt validated as teacher leaders through Noyce experiences, including developing expertise in less familiar areas (e.g. elementary teachers developing STEM content knowledge), which additionally supported teacher leaders in fostering both the self-efficacy and sense of responsibility to take on more ambiguous or newer leadership roles (e.g. MidwestSTEM03). Because our model accounts for internal factors, we noticed the influence of credibility and validation on teacher leaders’ sense of responsibility and transition toward a strong identity. Currently, the role of credibility and validation are considered in conversations about self-efficacy and general leadership (e.g. Galoji et al., Citation2012; Williams Jr et al., Citation2018), but rarely considered in teacher leadership. Thus, we see a need for models, like our Can’t-to-Becoming-to-Being model, that integrate cognitive and social theories to more holistically describe teacher leader identity development.

The role of self-efficacy in leadership identity development has already been given significant attention (e.g. Akman, Citation2021; Kurt, Citation2016); however, the part that one’s sense of responsibility plays in this area has not been adequately considered and needs to be studied more deeply. For instance, how might a sense of parenting (e.g. EasternSTEM01 and SoutheastM&S02) or, alternatively, a sense of youthful energy (e.g. MidwestSTEM04) be leveraged to increase a sense of responsibility related to teacher leadership? Professional development should consider opportunities to engage teacher leaders’ with like-minded peers and to expand teacher leaders’ knowledge, expertise, experiences, and systems thinking. Such opportunities may support teacher leaders in identifying organizationally embedded expectations, which may support teacher leaders in fostering a sense of responsibility both for student learning and leading (Diamond et al., Citation2004).

Consideration of Research Question 2:

What are the catalysts and inhibitors associated with STEM teacher leaders’ identity development, including the impacts of their participation in an external professional development program?

Zinn’s (Citation1997) and Collay’s (Citation2006) categories of factors affecting teacher-leader identity development minimally addressed the external-factors component. In contrast, the data we presented in shows that Noyce – an external factor – was the most-mentioned influence on the MTFs’ teacher leader identity. Given that the data was collected in association with the MTFs’ involvement in the various Noyce projects, this is not entirely surprising. What is significant is that Noyce was universally seen as a catalyst for the MTFs’ teacher leader development. Our focus in unpacking the findings related to RQ2 is to consider how Noyce functioned as a catalyst and how understanding that can inform our model.

shows the Can’t to Can shift as largely associated with changes in self-efficacy and the Can’t to Should shift as significantly related to changes in sense of responsibility. Related to the Can’t to Can shift, Noyce supported MTFs’ self-efficacy in multiple ways. By taking advanced coursework, MTFs gained more confidence in their content and pedagogical expertise. Particularly in STEM disciplines, content knowledge – and, to a lesser extent, pedagogical knowledge – is seen as an important currency for earning the respect of one’s peers (Swackhamer et al., Citation2009). The mutual engagement (Wenger, Citation1998) made possible by the Noyce projects as CoPs allowed for the recognition by MTFs that there were other people in the broader educational community who had ‘the same passion and drive and vision, but also the same struggles’, as MidwestMath03 described it. This enhances self-efficacy not only by overcoming the isolation that teachers often experience, but also by allowing the MTFs to become part of an affinity group that understands the profession the way that they do (Goings & Lewis, Citation2020). Finally, because the Noyce projects were run by university faculty members and because their peers were perceived as expert teachers, MTFs saw the Noyce teams as high-status groups whose validation could allow them to overcome challenges to their credibility within their schools systems; MidwestMath05 explicitly discussed the way Noyce provided this validation.

The Mind Tools Content Team (Citation2023) identified several ways that people in an organization can support those with whom they interact in taking responsibility, including: (a) providing clarity to the roles associated with their responsibilities, (b) assisting individuals in seeing the ‘bigger picture’ to which their efforts might contribute, (c) re-engaging individuals by better connecting their responsibilities to their values, and (d) guiding individuals toward an internal locus of control so that they feel more likely their actions will make a difference. There was little evidence in our data that schools and/or districts engaged in actions representative of any of the suggestions. shows that MTFs mentioned districts and/or schools resistant to change and/or not valuing teacher leadership nearly three times as often as they discussed supportive schools and/or administrators and mentioned resistant colleagues as often as they discussed supportive colleagues. Further, WesternMath02 specifically noted how an administrator at their school actually induced role ambiguity – or ‘mushiness’ as they described it – by being inconsistent about teacher leadership expectations. Thus, it appeared that the MTFs’ schools/districts did not significantly engender a sense of responsibility toward teacher leadership.

Comparatively, our data indicates that the Noyce projects did induce formation of a sense of responsibility in the MTFs. For instance, supporting MTFs in attending and presenting at conferences – including national ones – was mentioned 21 times in the interviews and contributed to the MTFs gaining a ‘bigger picture’ of educational issues and responses to those issues. Moreover, MTFs mentioned the clear expectations that Noyce projects set for them to act as leaders, and the provision of specific and clearly defined leadership opportunities, 32 times in the interviews. Related to this second form of catalysis, the Noyce projects assisted the MTFs in expanding their notions of teacher leadership, which likely allowed the MTFs to sense a better connection between their professional values and goals and the leadership activities in which they were able to engage. Finally, at least in one case – MidwestSTEM03—Noyce provided support for the development of an internal locus of control that allowed this MTF to identify advocates and forge alliances to promote the allocation of more time for science in MidwestSTEM03’s elementary school. This support eventually made it possible for MidwestSTEM03 to become the science specialist in that school, something for which the Noyce project made them ‘uniquely qualified’.

Our data suggested a general means by which the Noyce projects, as external CoPs, supported the MTFs teacher leader identity development: by assisting MTFs in imagining new possible selves and experimenting with new provisional selves, as well as by facilitating the convergence of these possible/provisional selves with the MTFs’ ideal professional self. We suggest that there are certain features of entities like the Noyce projects that can allow them to provide such support: (a) existing external to the established CoP (schools), therefore allowing them to assist community members in seeing the system in which the established CoP exists differently; (b) provide new role prototypes (Ibarra, Citation1999) and more models of these prototypes through engagement with teacher leaders in a variety of contexts and by aiding community members in seeing themselves differently; (c) offer support when the inevitable struggles of experimenting with provisional selves occur, and guide community members in overcoming those struggles; and (d) carry the status of a CoP that can confer credibility and validate the capabilities of individual’s exploring these new selves.

The Noyce projects were all – implicitly or explicitly – designed to offer these features, although there was mixed success across the projects in this vein. Our data demonstrate these features were manifest in certain cases. For example, Noyce allowed MidwestSTEM03 to see themselves as someone who could be the science specialist in their elementary school (feature 2), as well as advocate for a room in that school dedicated to science instruction and properly equipped for science explorations (feature 1). In the case of WesternMath01, Noyce supported them in overcoming their introversion, allowing them to take on a broader range of leadership roles (feature 2), and also aided WesternMath01 when they struggled with moving outside of their comfort zone in enacting these roles (feature 3). And MidwestMath05 explicitly stated that Noyce ‘validated [them] as a teacher leader’ to the point of giving themself the ‘authority to make those professional decisions in my classroom and try and pass that authority off to my peers’ (feature 4).

Huggins et al. (Citation2017) noted that professional learning could support teacher-leader identity development through the utilization of Wenger’s (Citation1998) three modes of belonging. Our discussion demonstrates how the Noyce projects employed engagement and imagination in engendering belonging; what the data did not make visible was any examples of the involvement of alignment in building belonging – specifically, alignment between the Noyce CoPs and the MTFs’ school CoPs. Given the external nature of the Noyce CoPs and the fact that Noyce projects often worked with multiple schools at the same time, this may present a particular challenge. Future research should explore whether this finding is replicable and whether there are projects that have found a way to address this challenge.

Conclusion

The Can’t-to-Becoming-to-Being model provides a comprehensive view of professional identity; the model builds on Sinha and Hanuscin’s (Citation2017) and Wenner and Campbell’s (Citation2018) frameworks, but additionally illuminates the role of specific internal factors – self-efficacy, credibility, validation, a sense of responsibility to lead, and alignment of possible and ideal selves – on identity shifts, as observed in interview data with over 100 MTFs. Research literature in education has predominantly focused on social views of leadership, but we see a need to incorporate the psychological and cognitive views of leadership studied in other disciplines. Our model also illustrates the role of conditions inside and outside of educational systems in catalyzing or inhibiting identity shifts. Notably, Noyce played an important role in catalyzing identity shifts that might not have occurred in schools without a supportive external CoP. A more nuanced understanding of teacher leadership identity development can support researchers and professional developers to more systematically create and nurture professional development and professional networks to positively influence teacher leadership trajectories.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (110.6 KB)Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all of the Master Teaching Fellows who patiently participated in interviews with us and shared their experiences. We would also like to thank the individuals who assisted with data analysis (listed alphabetically): Steve Barth, Allison Hardee, Emily McMillon, Leilani Pai, Maciej Piwowarczyk, Jill Schaefer, Lillian Sims, Dakota White, Weiqi Zhao. We thank Lindsay Augustyn for their artistic contributions to the design of . .

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2023.2292161.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Kelsey Quaisley

Kelsey Quaisley, PhD (she/they), is a postdoctoral scholar in the Department of Mathematics at Oregon State University. Both her research and teaching interests include the preparation and support of equitable instructors of mathematics at the tertiary, secondary, and primary levels. Her research aims to understand the stories and identities of students, instructors, and institutional leaders in shaping each other’s experiences and learning.

Wendy M. Smith

Wendy M. Smith, PhD (they/she), is a research professor in the Department of Mathematics and the director of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln’s Center for Science, Mathematics, and Computer Education. Smith researches institutional change and how to transform education systems to advance equitable STEM teaching and learning.

Brett Criswell

Brett Criswell, received his PhD in Curriculum & Instruction with a Science Education emphasis from Penn State University in 2009. He is currently an associate professor in the Department of Secondary Education at West Chester University. Dr. Criswell’s teaching focuses on general and science education courses for teacher candidates at the elementary, middle, and secondary levels. His main research areas are understanding how video analysis and reflection can support teacher preparation and the way in which STEM teacher leaders are developed and function within school systems.

Rachel Funk

Rachel Funk, PhD (she/her), is a research scientist for the Center for Science, Mathematics, and Computer Education at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. Her research interests include STEM teacher leadership, equitable teaching practices, and models for engaging students as partners in education.

Anna Hutchinson

Anna Hutchinson, EdD, is an adjunct instructor in the Department of Biological SciencesCollege of Education, Criminal Justice, and Human Services at the University of Cincinnati. Her research focus includes STEM teacher leader development influenced by organizational structure, curriculum and instruction evaluation, and program design and implementation for urban education.

References

- AAAS. (2021). Robert Noyce Teacher Scholarship Program. https://www.nsfnoyce.org

- Akman, Y. (2021). The relationships among teacher leadership, teacher self-efficacy and teacher performance. Journal of Theoretical Educational Science, 14(4), 720–744. https://doi.org/10.30831/akukeg.930802

- Angelle, P. S., & Schmid, J. B. (2007). School structure and the identity of teacher leaders: Perspectives of principals and teachers. Journal of School Leadership, 17(6), 771–799. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268460701700604

- Bailey, J., Hanita, M., Khanani, N., & Zhang, X. (2021). Analyzing teacher mobility and retention: Guidance and considerations report 1. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=REL2021080

- Barth, R. S. (2001). Teacher leader. Phi Delta Kappan, 82(6), 443–449. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172170108200607

- Barth, S., Criswell, B., Smith, W. M., & Rushton, G. (Under review). Modeling how professional development interacts with teacher leaders’ outcome expectancies and school environment perceptions. International Journal of Leadership in Education.

- Beech, N., Gilmore, C., Cochrane, E., & Greig, G. (2012). Identity work as a response to tensions: A re-narration in opera rehearsals. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 28(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2011.12.005

- Bowling, N. A., Khazon, S., Alarcon, G. M., Blackmore, C. E., Bragg, C. B., Hoepf, M. R., Barelka, A., Kennedie, K., Wang, Q., & Li, H. (2017). Building better measures of role ambiguity and role conflict: The validation of new role stressor scales. Work & Stress, 31(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2017.1292563

- Bowman, R. F. (2004). Teachers as leaders. The Clearing House, 77(5), 187–189. https://doi.org/10.3200/TCHS.77.5.187-189

- Bush, T., & Glover, D. (2014). School leadership models: What do we know? School Leadership & Management, 34(5), 553–571. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2014.928680

- Calvert, L. (2016). The power of teacher agency. The Learning Professional, 37(2), 51.

- Carver, C. L. (2016). Transforming identities: The transition from teacher to leader during teacher leader preparation. Journal of Research on Leadership Education, 11(2), 158–180. https://doi.org/10.1177/1942775116658635

- Caza, B. B., & Creary, S. (2016). The construction of professional identity. In A. Wilkinson, D. Hislop, & C. Coupland (Eds.), Perspectives on contemporary professional work: Challenges and experiences (pp. 259–286). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Collay, D. M. (2006). Discerning professional identity and becoming bold, socially responsible teacher-leaders. Educational Leadership and Administration: Teaching and Program Development, 18, 131–146.

- Danielson, C. (2007). The many faces of teacher leadership. Educational Leadership, 65(1), 14–19.

- Darragh, L. (2015). Recognising ‘good at mathematics’: Using a performative lens for identity. Mathematics Education Research Journal, 27(1), 83–102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13394-014-0120-0

- Darragh, L. (2016). Identity research in mathematics education. Educational Studies in Mathematics, 93, 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10649-016-9696-5