ABSTRACT

The present systematic literature review is undertaken within the context of concerted efforts aimed at diversifying the knowledge base of female leadership in the educational context. Much of the research in the field has been done in Anglo-American and European contexts. To this effect, the study conducts a systematic literature review to identify published research on female leadership in the Arab world written in English between 2000 and 2022. The findings of the review show a dominance of empirical studies with the majority being qualitative in nature and having a limited level of conceptualization, which poses a challenge to understanding female leadership as a contextual intersubjective phenomenon. This review highlights the importance of the sociocultural factors as a pivotal theme connecting with and affecting the three other themes of the review, the challenges and enablers of female leadership in the Arab world, and leadership perception and persona that women leaders develop. The review concludes with insights for researchers, policymakers and practitioners in the region.

Introduction

Understanding and exploring female educational leadership is part of a larger discourse on inclusiveness, equity, and emancipation, where vulnerable and marginalized groups are given equal opportunities for equitable participation (Shah, Citation2020; Sidani, Citation2005). This discourse of equity and inclusiveness is matched by persistent scholarly efforts and interest to study and analyze female leadership (Haslam & Ryan, Citation2008). Despite the numerous and consistent efforts to promote women’s participation in leadership positions in the Arab region, research continues to show their under-representation (Al-Lamki, Citation1999; Arar, Citation2018b; Arar & Oplatka, Citation2013). This under-representation is a manifestation of a number of contextual factors that impinge on aspirant and practising women leaders.

Leadership in general, and female leadership in particular, is an intersubjective, socially constructed notion (Blackmore, Citation1996; Dimmock & Walker, Citation2000). Therefore, understanding female leadership and the different factors affecting it requires a critical and sociocultural exploration of this construct across different contexts. The present study is specifically situated within the literature delineating gender and leadership as interconnected (Blackmore, Citation1996; Shah, Citation2020). Within the sociocultural conceptualization of female leadership, the present systematic literature review concedes that while female leaders in the Arab region share a number of the commonalities with female leaders in different parts of the world, they do have their own idiosyncratic challenges and experiences that are shaped by the socioeconomic, cultural, and religious contexts which require in-depth exploration and analysis (Arar, Citation2018a; Hammad et al., Citation2022; Sidani, Citation2005).

Developing a contextually relevant knowledge base for educational female leadership becomes particularly pressing in regions that are under-researched such as the Arab world (Hammad & Alazmi, Citation2020; Hammad et al., Citation2022). The under-developed knowledge base of female leadership in the Arab world is concomitant with a domination of Anglo-American theories and knowledge on global conceptions and understandings of female leadership (Hammad & Hallinger, Citation2017; Oplatka & Arar, Citation2017). The aim of this systematic review is to examine the female leadership literature produced in the Arab world during the period of 2000–2022, which in turn will reveal the gap in this field and recommend areas of further empirical research. The general aim of the research was guided by the following research questions:

What are the general trends of the female leadership literature in the Arab world in terms of geographical distribution, authorship trends, study type, research methods, educational context, and publication year?

What are the main themes emerging from the female leadership literature in the Arab world?

The present paper is organized in four sections. The first section provides a literature review of female leadership which will help in understanding the results; the second section provides an overview of the method used in the study; the third section comprises the analysis of the results, and the fourth section discusses the conclusions and recommendations of the study.

Literature review

The present section provides an overarching understanding of female leadership in the Arab world vis a vis the international and regional literature. This section begins by giving an overview of the ‘Arab world’ as a concept and as a context of the study.

Context of the study: the Arab world

The Arab world refers to the 22 countries in the Middle East and North Africa where Arabic is the dominant language, and Islam is the dominant religion. This region is also known for its shared cultural, historical, and religious heritage, and for its connection to the Arab League, a political and cultural organization of Arab countries. The 22 countries that constitute the Arab world are as follows: Algeria, Bahrain, the Comoros Islands, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, Mauritania, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. Consequently, publications addressing female leadership in these countries are included in this systematic review.

Within the scope of female leadership, several countries in the Arab region have been keen on reforming their educational systems and policies toward the inclusion of women in leadership roles (Romanowski & Al-Hassan, Citation2013; Vogel & Alhudithi, Citation2021). However, efforts at levels of legislation and policy development have failed in making educational institutions inclusive of women leadership as women continue to be under-represented in leadership positions (Al-Lamki, Citation1999; Arar, Citation2018a; Arar & Oplatka, Citation2013) as studies show that gender inequality persists (Arar, Citation2018a; Baroudi & Hojeij, Citation2021; Shah, Citation2020) in educational institutions.

While countries in the Arab world share several commonalities that advocate for considering it as a single unit of analysis (Hammad & Alazmi, Citation2020), each of these countries also has their own socioeconomic and cultural contexts that are nuanced from the remaining Arab countries. This is relevant to the argument Salibi (Citation1988) makes that Arabs differ in culture, history, ethnicity, and religion and the need for researchers to remain cognizant of these cultural nuances when studying social phenomena in the Arab world. This idea has also been highlighted by a number of systematic reviews done in the region (Hallinger & Hammad, Citation2019; Hammad et al., Citation2022). Stemming from the idiosyncratic contexts of different Arab countries, it becomes logical to accept that there is no single prototype for all Arab women. Female leaders’ lived experiences and the barriers they report, are relative to a particular part of the Arab world (Romanowski et al., Citation2019; Sidani, Citation2005).

Female leadership: a social phenomenon in the Arab world and the international literature

Understanding female leadership in the Arab world requires situating it within the international discourse of this phenomenon while being cognizant of and sensitive to the idiosyncrasies that distinguish Arab female leaders’ experiences. Interestingly and while leadership continues to be conceptualized in different ways, revealing its complex, intersubjective, and contextual nature (Dimmock & Walker, Citation2000; Hallinger, Citation1995), the role of gender has been less emphasized if not ignored in these conceptualizations (Shah, Citation2020).

According to Blackmore, gender is often not addressed in these leadership theories (1996, p. 103) ‘on the assumption that leadership styles and administrative contexts are gender neutral’, however, gender is a component of the sociocultural context in which leadership is practised (Halford et al., Citation1997; Shah, Citation2006). Gender determines, to a great extent, the socialization of individuals and their socially accepted and normative roles (Blackmore, Citation1996). This in turn affects the manner in which males and females practise leadership, making it one of the contextual prisms used to understand this phenomenon (Fuller, Citation2014). While educational leadership, as a general concept, continues to be under-theorized and under-researched in the Arab world (Hammad & Hallinger, Citation2017; Hammad et al., Citation2022), systematic reviews in the field specifically indicate female leadership as one of the topics that are particularly under-studied in the region (Hammad & Hallinger, Citation2017; Hammad et al., Citation2022; Oplatka & Arar, Citation2017).

Notwithstanding, recent years have witnessed an increased interest in studying female leadership in non-Anglo-American contexts (Shah, Citation2020) and more specifically the Arab world (Arar & Oplatka, Citation2013; Arar & Abu-Rabia-Quederb, Citation2011; Baroudi & Hojeij, Citation2021; Romanowski et al., Citation2019; Vogel & Alhudithi, Citation2021). Despite the diverse scope and purpose of these studies, they concur that female leaders in the Arab world face diverse challenges and barriers when assuming and progressing in leadership positions and are under-represented in leadership positions in educational institutions. This under-representation is a manifestation of the complex sociocultural context of the Arab world, which remains a male dominated context (Abalkhail, Citation2017; Arar & Abu-Rabia-Queder, Citation2011; Vogel & Alhudithi, Citation2021).

Although specific data on the number of women occupying leadership positions in the Arab world are not available, statistics on gender parity in this area maybe an indirect indicator of the situation of women leadership in the Arab world. Global statistics indicate that the Middle East and North Africa regions, where Arab countries are situated, lag behind in achieving gender parity with a score of 62.6% (World Economic Forum, Citation2023). Worryingly, this represents a 0.9 percentage-point decrease in parity since the last assessment in 2006, using a consistent sample of countries. Among the countries in the region, the United Arab Emirates, Israel, and Bahrain have made the most progress toward gender parity, while Morocco, Oman, and Algeria rank the lowest. Even the three most populous countries in the region – Egypt, Algeria, and Morocco – have experienced declines in their parity scores since the last assessment. At the current pace of progress, it is estimated that it will take 152 years to achieve full gender parity in the region and this is not considering the percentage of women occupying leadership positions.

Understanding the relationship between gender and leadership necessitates an understanding of the socially constructed roles for both males and females. In general, women are considered the keepers of the household where they are held responsible for caring and nurturing (Grogan & Shakeshaft, Citation2011; Shah, Citation2020). Men, on the other hand, are the breadwinners, responsible for protecting and providing. Within these socially constructed gendered roles, organizations have traditionally been based on the belief that men are the primary breadwinners and, therefore, hierarchical structures within organizations have been established with women being employed as cheaper labor (Metcalfe, Citation2008; Shah, Citation2020). This explains why many organizations remain gendered due to their work structures being better suited for men’s lifestyles resulting in a masculine domination in organizations. In addition to organizational structures that are not conducive to female leadership, leadership has been consistently perceived as a male function requiring directedness, assertiveness, and authority (Arar, Citation2018b; Shah, Citation2020).

These ‘male’ characteristics do not align with women’s socially constructed roles of nurture, care, and support. In tandem, the prevalence of men in leadership positions has been reinforced by the adoption of neoliberal approaches to education and the accompanying managerial ideologies of competition and efficiency, which promote performative cultures (Gunter, Citation2001). These cultures tend to embrace masculinist traits of leadership, such as individuality and competition, while not valuing feminine leadership styles, such as empathy, collaboration, and supportiveness (Gunter, Citation2001).

Naturally, and because of the different socialization processes women experience and the role conflict they encounter, studies indicate a difference in leadership styles between men and women (Abalkhail, Citation2017; Arar & Oplatka, Citation2013; Brunner & Grogan, Citation2007). These differences stem from their socially constructed roles, where male leadership is characterized by being directive and autocratic (Baroudi & Hojeij, Citation2021; Brunner & Grogan, Citation2007), while women leaders are likely to exhibit a more relational and transformational leadership style compared to men (Baroudi & Hojeij, Citation2021; Vogel & Alhudithi, Citation2021).

However, while these female leadership practices are commendable, there are concerns that female leaders are adopting them to resolve the dilemma they face between their socially normative gender roles and the requirements of ‘successful’ leadership (Arar, Citation2019; Shah, Citation2006) in a performative (Gunter, Citation2001), male-dominated environment (Arar, Citation2019; Shah, Citation2006). This dilemma is best understood within women’s private and public spheres (Arar, Citation2019; Shah, Citation2006). Within their private sphere, women behave according to their gendered roles, however, in the public spheres, female leaders are expected to adopt ‘masculine’ traits of leadership to succeed. In turn, women have been adopting ‘masculine’ leadership in order to be perceived as ‘successful’ and at the same time making sure that they stay in touch with their ‘feminine’ side by adopting feminine leadership (Arar & Abu Rabia Queder, Citation2011; Shah, Citation2020). In the Arab world, this aligns with the argument on the domesticity of women (Arar, Citation2018a) situated within the sociocultural context of the region (Metcalfe, Citation2008; Shah, Citation2020).

Weber (Citation2017) contends that religion is part of the social fabric of societies. With Islam being the predominant religion in the Arab world (Shah, Citation2020; Sidani, Citation2005), it is logical for studies conducted in the region to focus on its effect on female leadership. This is not to suggest that other religions in the region do not affect female leadership. Scholars contend that several notions present in Islam emphasize male leadership. The man in Islam is seen as the head of the family where this is supported by the Shari’a law and specifically the notion of qiwama (taking responsibility). The man is therefore charged with the protection of the honor and chaste ‘sharaf’ of the women (daughters, sisters, wives and cousins) in his family, tribe and hamulla (extended family) (Metcalfe, Citation2008; Shah, Citation2010). Socially, women are expected to maintain their modesty by avoiding contact with men outside of their close relatives (Shah, Citation2010).

In using religion to understand the sociocultural context in which female leadership is enacted, two important points need to be considered. The first is that the extent to which Islam, as a religion, affects social phenomena such as female leadership is dependent on the sociocultural context of the different Arab countries and the degree to which Islamic doctrines are embedded in the legislative context and social norms. For example, in Lebanon, Tunisia, and Syria women are not required to have a Mahram (brother, father, uncle or husband-unmarriageable male) when traveling, and they can work in coeducational institutions. This is an example of how the idiosyncrasies within the Arab region represent an important conceptual prism through which female leadership is analyzed and understood; Arab women do not all have the same experiences and the same barriers (Sidani, Citation2005). The second point is one that calls for caution when attempting to analyze female leadership using Western media stereotypes of Muslim women being oppressed (Sidani, Citation2005) when scholars (e.g. Charrad, Citation2011) argue that Muslim women are no longer ‘nameless’. These arguments sit comfortably within the notion of Said’s (Citation1978) Orientalism and the manner in which the more dominant West views the less dominant East.

These arguments suggest that the conventional post-colonial perspectives on Muslim women should be questioned and that female leaders’ challenges and experiences should be studied comparatively in relation to gender inequalities around the world while being situated in their idiosyncratic contexts.

Method

Our methodology for conducting this review followed the guidelines for systematic research reviews outlined by Hallinger (Citation2013) and Zawacki-Richter et al. (Citation2020). Systematic review methods involve the utilization of a commonly accepted set of procedures, criteria, and standards to identify and analyze a body of research on a particular topic (Hallinger, Citation2013). While our primary focus was on qualitatively identifying the main themes emerging from the literature under investigation, the analysis also involved the use of descriptive statistics to highlight the publication trends found in this literature. In conducting our review, we were guided by prior reviews using similar methods (e.g. Hammad & Hallinger, Citation2017; Hallinger & Chen, Citation2015; Mifsud, Citation2023; Oplatka & Arar, Citation2017). In this part of the paper, we describe the methods used for identifying eligible sources, extracting relevant information and analyzing data.

Identification of eligible sources

In order to locate potential sources, we utilized expansive search methods instead of restricting our search to a specific set of international journals, which is the approach taken by some previous educational leadership and management (EDLM) reviews (e.g. Atari & Outum, Citation2019; Bellibaş & Gümüş, Citation2019; Hammad & Hallinger, Citation2017). The reason behind this was to ensure the inclusion of the highest number of articles possible, since prior EDLM reviews have documented a scarcity of research on female leadership in the Arab region (see Hammad & Hallinger, Citation2017; Hammad et al., Citation2022). Therefore, comprehensive research databases such as Scopus, Web of Science, and ERIC were searched for relevant sources using a set of search terms such as ‘female leadership’, ‘women leadership’, ‘female management’, ‘women management’, ‘women leaders’, ‘female leaders’, in combination with the word ‘Arab’ or the name of one of the Arab countries. Google Scholar was also searched to ensure that we did not miss relevant sources. This procedure yielded 155 sources including research articles, book chapters, dissertations, and conference papers. The sources also included studies conducted in non-educational settings. We refined the dataset identified by selecting sources that met the following set of inclusion/exclusion criteria: (1) articles/book chapters related to at least one Arab country; (2) articles/book chapters focused on female leadership in educational settings, including K-12 and higher education institutions; (3) articles/book chapters that were empirical, conceptual, or research reviews; (4) articles published in refereed journals with a blind peer review system, or book chapters published by well-known publishers; (5) articles/book chapters published between 2000 and 2022; (6) articles/book chapters written exclusively in English. Applying these filters resulted in the exclusion of a number of sources from the dataset, thus bringing the total number of eligible sources to 40, of which 37 research articles and 3 book chapters. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) protocol, adapted from Moher et al. (Citation2009), was employed as a framework to report the results at each stage of the source identification and screening process (see ).

It is important to note that, while Israel is not an Arab country, we decided to include sources addressing female leadership in the Arab sector of Israel since this sector shares a cultural and historical heritage with the rest of the Arab countries. Moreover, including relevant studies from the Arab sector of Israel can contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of female leadership in Arab societies.

While conducting the present review, we remained aware of the importance of establishing the robustness of our findings. Therefore, in addition to applying strict inclusion/exclusion criteria to ensure the inclusion of only relevant, high-quality sources, we subjected the subset of empirical studies identified (n = 34) to a methodological quality assessment using criteria devised by Kmet et al. (Citation2004). Kmet et al.’s (Citation2004) tool is used in systematic reviews to evaluate the quality of individual studies included in the review. The tool has 14 criteria for assessing quantitative studies such as clear research questions, suitable research designs, appropriate analytical procedures, adequate sample size, and clear reporting of results. For evaluating qualitative studies, the tool has 10 criteria, including sufficiently described research objectives, clear study contexts, appropriate study designs, connection to a theoretical framework, and conclusions supported by the results. Although different, both sets of criteria share a common objective: evaluating the ‘internal validity of the studies, or the degree to which the design, conduct, and analyses minimized errors and biases’ (Kmet et al., Citation2004, p. 2). Applying these criteria proved useful as it provided a structured and comprehensive means to evaluate the quality of the studies included in our review. Our selected sample of empirical studies was found to fulfill the specified criteria.

Data extraction and analysis

The studies were scanned to extract essential information needed for the descriptive phase of the analysis, including author name, study title, publication year, authorship trends, country of origin, study type, research methods, and data collection techniques. The obtained data was entered into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and coded to facilitate descriptive analysis. For example, each study type was assigned a specific code (e.g. empirical = 1, conceptual = 2 and review = 3). Similarly, the research methods were coded as follows: Quantitative = 1, qualitative = 2 and mixed = 3. Descriptive statistics were applied using frequencies and percentages to highlight the main patterns and characteristics found in the studies.

In line with similar previous reviews (e.g. Mifsud, Citation2023; Oplatka & Arar, Citation2017; Wang & Gao, Citation2022), the second phase of our analysis was conducted using narrative review to combine and summarize data from multiple studies to gain new insights and understanding. This approach involves organizing and synthesizing the data and findings from individual studies into a coherent and comprehensive narrative that captures the central themes, patterns, and relationships (Popay et al., Citation2006). To this end, two of the researchers read the articles carefully and coded meaningful sections relevant to answering the research questions using different aspects of Collaborative Qualitative Coding (CQA) (Richards & Hemphill, Citation2018) and more specifically combining consensus and split coding (Gibbert et al., Citation2008; Patton, Citation2014). The two coders read and independently coded the same three articles using both open coding used to identify discrete concepts and patterns and axial coding to make the connection between these patterns (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990).

In this consensus coding (Gibbert et al., Citation2008; Patton, Citation2014) the aim was to identify general patterns that were common across the different articles and also to note deviant cases that appear during the coding process. Both researchers kept memos and notes during this coding process, which they shared with each other during their weekly meetings (Patton, Citation2014). After the agreement on and the general patterns and the codes, one of the two coders reviewed all the information agreed upon and developed the preliminary codebook. The codebook included the codes, the memos and notes associated with them and the excerpts which they coded from the different articles. This codebook was then discussed and agreed upon in a team meeting including all three researchers. The team agreed that this code book will serve as a guideline in the coding process, leaving opportunities for the addition, merging of codes and hence resembling aspects of constant comparative method of grounded theory (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990). This codebook was then piloted on one article that was not coded before, the sub-code hamula (and this was expected to be the term hamula was only used in studies conducted in the Arab sector of Israel) was added. After this, both coders began coding articles assigned to them, and this was the stage split coding (Gibbert et al., Citation2008). When both coders have finished coding all the articles one of the coders took all the codes, the excerpts, memos, and notes and developed the themes from the codes keeping the memos, notes, and excerpts next to each group of codes and the theme that it had developed into. These themes along with the codes they comprise and the excerpts that they represent were discussed in one final meeting, including all three researchers. This final meeting was important, and notes were taken regarding the structure, general patterns and how the themes relate to the conceptual framework of the research (Richards & Hemphill, Citation2018). These were in turn included in the findings and discussion section of the manuscript.

Based on the above, our collaborative coding analysis benefited from both consensus and split coding with their respective open discussions (Gibbert et al., Citation2008), the constant comparative method (Corbin & Strauss, Citation1990), attention to intercoder differences. Collectively, these methods have contributed to the trustworthiness and credibility of the narrative analysis.

Findings

This section presents the findings of the descriptive and narrative analyses of the data.

Descriptive analysis

This section provides a quantitative description of the reviewed literature. We believe that, even in a narrative review, outlining the descriptive characteristics of a body of literature can still be valuable as it allows us to sketch a comprehensive and objective picture of this literature and illuminate the prevalence of specific study types, research methods, authorship trends and other aspects. This information can then be used to contextualize the narrative findings and to demonstrate the significance of the results in a broader context.

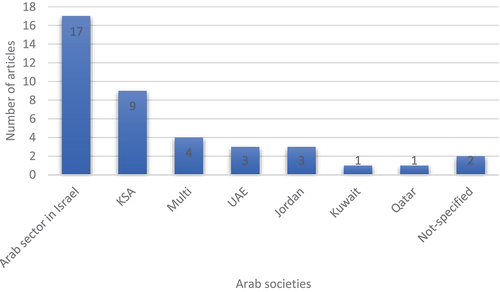

We were interested in exploring the geographical distribution of female leadership studies as it can provide insights into the specific cultural, social, and political contexts in which female leadership is being studied and explored. This helps to contextualize the findings and provide a deeper understanding of the challenges and opportunities faced by female leaders in the region. As shown in , the analysis of the dataset by country reveals that studies from/about the Arab sector in Israel represented 42.5% (n = 17) of the total corpus of female leadership literature. These were followed by Gulf-related studies (40%, n = 14), with Saudi Arabia (n = 9) and the UAE (n = 3) emerging as the most frequently studied contexts in this region. There were three studies from Jordan. Four studies were coded as ‘multi’ since they covered multiple countries, while two studies were general in nature and did not refer to any specific country. This uneven distribution of female leadership literature is consistent with the broader picture of the EDLM scholarship in Arab societies (see Atari & Outum, Citation2019; Hallinger & Hammad, Citation2019).

Another significant feature relates to the authorship trends found in the reviewed female leadership literature. Analyzing authorship trends can provide insights into the representation of female scholars in the field, which can help to assess the progress of gender equity in academia (Winchester & Browning, Citation2015). Our analysis demonstrates that 16 publications were authored by female scholars, 12 by male scholars, and the remaining 12 were coauthored by a mix of male and female scholars. In terms of research collaboration, 23 of the publications (57.5%) had multiple authors, while 17 (42.5%) were single-authored. Additionally, it was noted that among the single-authored publications, there were eight written solely by female scholars.

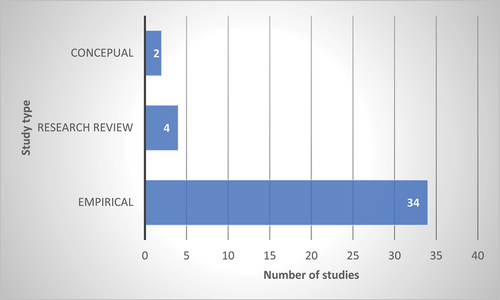

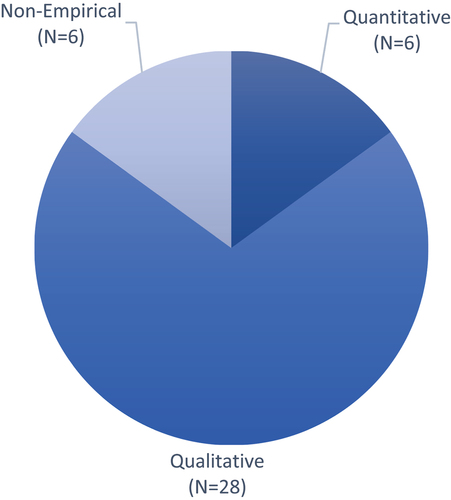

It was also important to examine the composition of Arab female leadership literature according to study type and research methodology as it helps to assess the maturity of the scholarship under investigation (Hallinger & Bryant, Citation2013). Analysis by study type reveals that 80% of the publications (n = 34) were empirical studies. Research reviews made up 10% of the dataset (n = 4), while there were only two conceptual papers (see ). Analysis by research methodology () shows that the majority of studies (70%, n = 28) were qualitative, with interviews being the predominant data collection method (n = 27), followed by quantitative studies at 15% (n = 6). No mixed-methods studies were identified. While the predominance of empirical research resonates with the features reported for the broader EDLM in the Arab region (Hallinger & Hammad, Citation2017), the prevalence of qualitative methods used to study female leadership stands out as a distinctive feature of the literature reviewed in the current study.

Additionally, the educational context studied in the female leadership literature was analyzed to determine the context of the studies. Results showed that more than half of the studies, 52.5% (n = 21), focused on female leadership in K-12 schools, while 35% (n = 14) targeted higher education institutions. The remaining five studies did not specify a particular educational context.

Moreover, analysis of the female leadership literature according to publication date demonstrates a growing interest among scholars in the region to study the topic. Indeed, the vast majority of the publications (82.5%) were published in the second half of the specified time frame (i.e. from 2011 onwards). This aligns with the steady growth of the Arab EDLM knowledge base in recent years (Author, Citation2019).

Emergent themes

Narrative analysis of the articles included in this review resulted in the identification of the four main themes: macro/socio-cultural factors impinging on the female leadership trajectory, challenges/barriers to female leadership, enablers of female career progression, and leadership perceptions, significance, and enactment. These themes are discussed in the section below

Theme 1: Macro/Socio-cultural factors impinging on the female leadership trajectory

Despite the global pressures for more democratic configurations and improvement in human rights accompanied by more tolerant policies, most Arab countries have failed to transform their governmental and political structures into more egalitarian ones, consequently leading to more repression and lack of accountability, with a regressive effect on the potential of female educational leaders. These macro factors trickle down to the organizational processes and practices, with an impact on women accessing leadership positions.

Male domination featured prominently in our analysis. In the words of Arar (Citation2018b), ‘we are still a male-dominated society’ (p. 757), where specific cultural and religious beliefs and values govern and define the feminine role in terms of housekeeping and child-rearing obligations, especially in the early stages, thus posing as a deterrent to Arab women who wish to build a career outside the home. Shapira et al. (Citation2011) argue that women experience social opposition and political pressure even prior to their appointment as principals, an unprofessional opposition disregarding their skills and experience, but rather emanating from a perceived threat by their entry into the public sphere and attaining positions of central authority in the community. Patriarchal society attributes strong local power to the extended family or ‘hamulla’ (a term exclusively appearing in the Arab-Sector Israeli studies), and the local tribes which often interfere with the school's internal politics (Arar, Citation2019). These powerful interest groups attempt to exert pressure on teacher appraisal or layoff, with women educational leaders finding it difficult to resist these pressures (Arar & Oplatka, Citation2016). These tribes and extended families are governed and led exclusively by men and their decisions are binding. While these pressures are exerted on both men and women in their workplaces, the exclusion of women from extended family and tribal meetings and consequently the inability of these women to voice their opinions and concerns augments these pressures for women leaders. Both the internal politics of the tribe and the extended family from which the female principal originates and arising political conflicts among feuding tribes due to a divergence between her ‘tribe’ or ‘hamulla’ and that of the school population also play a major role in a female’s leadership appointment and her eventual leadership practices (Shapira et al., Citation2011). It is the ‘cultural, tribal, and political systems’ that construct female leadership as ‘tribal status, gender and class play a significant role in the field of leadership’ (Al-Oraimi, Citation2013, pp. 24–25). The cultural resistance exerted by the powerful tribes and extended families featured in a number of publications, namely Karam and Afiouni (Citation2014), Abalkhail (Citation2017), Al-Oraimi (Citation2013), Alomair (Citation2015), Arar (Citation2018b) and Shapira et al. (Citation2011), among others.

The role of religion, in this case Islam, was another prominent feature in our analysis. Abalkhail’s (Citation2017) empirical study reveals how the twin discourses of family and Islam, framed within the influential patriarchal assumptions concerning gender roles and lead roles, lead to an archetype of gender inequalities in Saudi higher education. Islam, as the dominant religion in the Arab region, has shaped the relationship between men and women in both private and public domains, with the patriarchal interpretation of Islam about women’s position in society supporting gender inequality. The ideas of ‘qiwama’ and the issue of women’s modesty and morality/chastity ‘sharaf’ are examples of how patriarchal interpretations of Islam are used to validate and warrant the gender order. The notion of qiwama’ where the husband assumes responsibility for the wife in the household is interpreted selectively by Saudi male leaders in such a way that any leadership position (responsibility or ‘qiwama’) assigned to men in the family domain automatically implies their exclusive leadership in public life. The issue of modesty and morality that results in the segregation of physical space and interaction at work positions women as ‘outsiders’ and ‘symbols of purity’ (Abalkhail, Citation2017, p. 178 original emphasis), thus excluding them from organizational opportunities that would aid their climb up the career ladder. The family discourse also plays a vital part in being admitted to leadership positions, as ‘it is who you know and your family name that facilitates the careers of women within organisations’ (Abalkhail, Citation2017, p. 178 original emphasis). Various studies have identified interpretations of Islam, more specifically, male interpretations, as a barrier to leadership for women. Religion itself is not a barrier, ‘yet used as a good cover for masculine practices along with an erroneous interpretation of religious principles’, with religion as a ‘good cover for male chauvinism practices and ‘egoism’ (Ensour et al., Citation2017, p. 1075). Patriarchal customs have thus become embedded within Islamic legal decisions, rulings and judgments due to contemporary interpretations of Islam played out in society (Karam & Afiouni, Citation2014; Romanowski & Al-Hassan, Citation2013). Nevertheless, one may also detect the empowerment of women in Islam with elements of women’s rights embedded in Islamic concepts of social justice, particularly in Islam’s call for education without discrimination for both males and females (Samier, Citation2016).

Within the role of Islam in female leadership, Arar and Shapira (Citation2016) focus on another cultural norm expected of women leaders – the wearing of the ‘hijab’ – another instance where women’s decisions are deeply affected by societal norms and traditions, where ‘head covering was a continuation of the acculturation that they had received’ (p. 857). While the ‘hijab’ provided support for some, in terms of providing cultural protection and a sense of belonging to the society, as well as legitimizing acceptance within traditionally perceived male spheres, this was experienced as a pressure by other women who were thus positioned as outsiders. Within all these macro pressures and cultural norms impinging on females’ rise up the leadership career ladder, there are nations in the Arab world where the State is playing an active role in promoting women’s rights. Al-Oraimi (Citation2013) outlines how the United Arab Emirates (UAE) constitution has been trying to promote women’s rights at distinctive stages, with recent reforms focused on improving women’s capacity to move to a more active public role, reflecting the government’s attempts at fostering more egalitarian environments. Specific initiatives have been taken to promote and develop women’s capacity in educational leadership, such as the establishment of new schools and universities for a women-only population, and the setting up of leadership schools. The government has also initiated a national strategy for women through the General Women’s Union, with empowerment of women in the executive leadership and higher education as the strategy’s top priority. This contributes to the redefinition of gender roles, where the relationship between males and females is no longer based on gender hierarchy, with a shake-up of the masculine image in public and private spheres. This challenge to the patriarchy is still being met by resistance due to inherent power discourses and dangers of tipping the balance in this gradually developing power struggle.

Female teachers encounter resistance as they rise up the career ladder (Arar, Citation2019), further evidence of the patriarchal forces trickling down from the wider macro society to the school micro-culture. Traditional cultural scripts in Muslim society coupled with the local ethnic concept affect Muslim teachers’ conceptions of principalship (Arar & Oplatka, Citation2013). Teacher resistance toward female leaders is a manifestation of teachers’ conceptions of what constitutes principalship; a conception that is fundamentally constructed based on a male dominated conceptualization of leadership. Patriarchal mind-sets ingrained in the Arab world with regard to the perceived difference in male and female abilities put the effectiveness of women’s work as leaders into question, with Arab teachers reportedly exhibiting negative attitudes toward female principals, with both male and female teachers preferring a male principal, as reported in the literature review by Arar and Oplatka (Citation2016). On the other hand, in an earlier empirical study conducted by Arar and Oplatka (Citation2013), despite respondents holding traditional hegemonic beliefs in their perception of an authoritative and hierarchical principal–teacher relationship, this did not reflect their preference for a male principal – a finding that contrasts with studies conducted by Akkary (Citation2014).

Theme 2: Challenges to female leadership

Baroudi and Hojeij (Citation2021) describe how leadership opportunities in the Arab world, even in the education sector, are mostly assigned to men. Females either refrain from taking on leadership roles due to their prioritized family duties as wives and mothers or else due to the exclusive availability in gender-segregated places of work. In their systematic review of Arab female educational leaders’ careers and leadership, Arar and Oplatka (Citation2016) point out that very few Arab women were assigned educational leadership positions before the twenty-first century, with the published empirical studies ‘attempt[ing] to listen to the usually unheard voices of these women, describing their difficulties in attaining their posts’ (p. 100).

The family comes across as the major deterrent preventing females in teaching positions at both compulsory schooling and higher education levels from taking on and eventually succeeding in leadership roles. Family responsibilities, obligations and priorities emerge as the most influential factors in women’s development, namely their roles as wife, mother, and their career (Ensour et al., Citation2017). They encounter difficulties in maintaining a work–life balance (Arar & Oplatka, Citation2016) as they attempt to cope with the pressure of their family role in parallel with their responsibilities as school principals (Arar & Abu-Rabia-Queder, Citation2011). Romanowski and Al-Hassan (Citation2013) explain how the understanding of Arab women is very traditional, with the Arab culture focusing on motherhood and domesticity, more specifically the female reproductive functions, which Arab women feel pressured to conform to due to societal considerations as ‘the upholders of cultural values and traditions’ (p. 3). They further point out that the domestic and maternal views of the women act as gatekeepers not only to a woman’s performance as a leader but also her ability to pursue leadership positions. There are high expectations in Islamic society for the role women play as parents and as children themselves, thus having to take care of their parents and those in need, besides bearing the brunt of childcare responsibilities, household tasks, and marital duties (Almansour & Kempner, Citation2016). The women paid the price of putting their dreams in second priority after their familial obligations, expressing regret and inadequacy at their ability to multi-task, ‘It is never easy to move between these two worlds – home and work’ (Arar, Citation2019, p. 759). A critical review of the literature on women in Saudi higher education (Alomair, Citation2015) also identified family and social pressures; difficulty balancing family and work; fear of responsibility; and gender stereotypes as the main obstacles.

Many of the national legal frameworks embody restrictive Islamic interpretations for women, that, combined with other socio-cultural factors, contribute to the macro-system that disadvantages women in the workplace. Participants in Ensour et al.’s (Citation2017) study stated that ‘equality is actually on paper, as practices are far from what is formally written’ (p. 1068). Karam and Afiouni (Citation2014) argue that the embedded legal and legislative frameworks in the Arab nations are still very restricted with regard to women. Notwithstanding the adoption of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) emphasizing gender equality of all citizens before the law, women still face pervasive and systematic legal forms of discrimination. Consequently, women have to battle constricting constitutional rights and labor laws ‘that ensure rights for men and women workers are contradicted and contravened by family laws that place a woman under the guardianship of a male and require her to obtain the permission of father, husband, or other male guardian to marry, seek employment, start a business, or travel’ (Moghadam, Citation2004 cited in Karam & Afiouni, Citation2014, p. 506). This is exacerbated by the prevailing patriarchal social view that women’s chief responsibilities are as ‘caretakers of the family and children’ (p .511). Maternity leave after the birth of a baby has also been reported as a cause for concern by participants in Ensour et al.’s (Citation2017) study who claim that 6 weeks is not enough for the mother and baby, forcing women to quit jobs, rather than climb the career ladder, to take care of their children. In a nutshell, ‘Social factors cannot be separated from the cultural factors which are all clustered around the male chauvinism in Arab societies, rejection of women’s leadership, a stereotypical depiction of females as incapable, and females’ acceptance of an inferior position’ (Ensour et al., Citation2017, p. 1072). This empirical study focuses on Jordan legislation and legal provisions that consider women as dependents, limiting their freedom of choice and reinforcing the perception of women as secondary breadwinners, with parenting as their exclusive responsibility. Besides having to endure stifling legal frameworks and unsupportive working environments, Karam and Afiouni (Citation2014) report the stigma still attached to a husband whose wife works outside the home, with some women refusing promotion in order to maintain harmony in the family and avoid repercussions with cultural norms.

Women do face a glass ceiling when it comes to accessing opportunities to educational leadership positions, but that glass ceiling is being cracked, with the female leaders consequently serving as role models (Addi-Raccah, Citation2006; Ensour et al., Citation2017). Notwithstanding, those female principals who are ‘glass ceiling breakers’ and have formal responsibility and authority bestowed on them still face hurdles since their gender has a substantial bearing on teachers’ acceptance of their authority in the Arab world. According to A’li and Da’as (Citation2017), ‘The school is found to be an expansion of the public sphere which favours men. Schools do not break the walls separating the educational space and the public space – women are still jailed behind these walls’ (p. 97, emphasis added). Their empirical research revealed a more positive outlook in male and female teachers’ perceptions toward acceptance of a male principal’s authority, with distinctly less positivity of male teachers in a female principal’s regards. This is because Arab communities bestow ‘the power of authority’ to men who are considered to be ‘natural leaders’, with strong women frowned down upon due to jarring with the stereotype. Arar and Shapira (Citation2012) further confirm that men find it hard to accept a woman as their boss. Male teacher participants in Arar & Oplatka’s (Citation2013) study expressed their struggles at being led by a female principal, confessing that ‘it hurts their pride to work under a woman’, as ‘to get orders from a woman is awful’, moreover claiming that ‘an Arab male teacher would not prefer the dominance of a woman … [as] it will send him to psychiatric treatment’ (p. 108). A prejudiced lack of confidence in women’s capabilities to fulfill the principalship role thus exists (Arar & Abramovitz, Citation2013). Female principals even wear traditional clothing once they are appointed to the role, in order to be accepted within the community (Arar & Shapira, Citation2016). Besides implying a connection with the community, this enables them to exert power and influence both within and outwith the school community, especially in interactions with men. In other words, ‘the “hijab” constituted a tool for their protection, action and movement’ (Arar & Shapira, Citation2016, p.863).

Arar and Oplatka (Citation2016) point to other factors that serve as a deterrent to women’s career advancement in school, namely their low self-confidence; gender segregation and discrimination; as well as low participation in secondary education. Women’s low self-esteem contributes to the longevity in their career paths before reaching leadership positions, as well as being older when compared to male counterparts. This is further compounded by a lower sense of self-efficacy despite their superior education and enhanced professional experience. Another major obstacle in Arab schools is the entrenched ‘socio-cultural structuring that bifurcates the society into male and female arenas’ (Arar & Oplatka, Citation2016, p. 102), with women thus forced to retain submissive roles. Moreover, in North African Arab societies such as Morocco, Tunisia, and Libya, in addition to Saudi Arabia as an Arab state, girls’ access to compulsory education is limited due to poor infrastructure and the family’s financial situation.

Besides these entrenched socio-cultural barriers, Arab females in higher education face specific difficulties to attain faculty posts in the world of academia (Arar Citation2018b; Abalkhail, Citation2017; Almansour & Kempner, Citation2016; Alomair, Citation2015). Abalkhail (Citation2017) explores challenges constraining female lecturers from accessing leadership positions in Saudi public universities. Recruitment and promotion policies and processes favor men, while physical gender segregation in the workplace further marginalizes women and reinforces the patriarchal system. Moreover, those who do not hail from privileged family backgrounds have to battle the double-edged inequality of both class and gender – ‘in theory, gender equality exists in university policy but, in practice, men are favoured over women in almost everything, as men are considered the primary income earners and the heads of their households’ (Abalkhail, Citation2017, p. 174). Furthermore, females are disadvantaged with regard to training opportunities due to gender bias and discrimination concerning travel due to ‘traditional non-written, natural order of things socio-cultural values and Sharia law’ (ibid, p. 175, original emphasis). This lack of freedom to travel without a Mahram is highlighted by Almansour and Kempner (Citation2016), who further add the difference in research purpose and perception between male and female academics, giving the former an advantage due to their opportunistic view of publishing primarily for promotion, favoring quantity over quality and the contribution to the public sphere.

Theme 3: Enablers of female career progression

Despite all odds present and deeply ensconced within the Arab patriarchal society, female teachers and academics do succeed to break the norm and go beyond societal expectations to obtain and maintain educational leadership positions. The main attributing factor toward achieving this success is the personal background that shapes these women’s leadership. Access to educational opportunities and potential for empowerment in their early childhood in a supportive family (Arar & Oplatka, Citation2016) provided their initial stepping-stone to success. The mental and moral support (Baroudi, Citation2022; Baroudi & Hojeij, Citation2021) of both their families and husbands, in addition to other male relatives, helped them transcend gender distinctions via the provision of support from childhood through to every career stage, thus fostering coping strategies and tools for participation in the public sphere. Shapira et al. (Citation2010) note how despite different personal backgrounds, all the female principals in her study were driven to further their studies and aspire for leadership positions from childhood. According to Abalkhail (Citation2017), the father as a role model is the leading inspiration in these female leaders’ career choice and success, due to supporting both their education and profession. It is ‘thanks to the male umbrella’ (Arar, Citation2014, p. 424) that these women are able to progress, since they need the sanction of their father, brother, fiancé or husband. Abalkhail’s (Citation2017) participants reported receiving support from their ‘educated’ husbands, who may act as a ‘facilitator’ or ‘great supporter’ (p. 176).

Aspiring for future personal progress is another enabler (Arar, Citation2014), especially when combined with strong character traits such as self-confidence, focus, determination, industriousness, and assiduousness. This expedites the course of defying stereotypes by realizing the potential for leadership positions (Abalkhail, Citation2017). Women who manage to get in the upper leadership circle regard themselves as agents of social justice, as they focus on finding social solutions for educational injustices (Arar, Citation2014).

Abalkhail (Citation2017) argues that government initiatives in relation to female education, namely access to schooling, and higher education, more specifically, has empowered women to move outside their domestic sphere and get a foot on the career ladder. Holding a professional status helps women to benefit from an improved social and financial standing. Having strong professional relationships with the major school community stakeholders, namely teachers, students and parents, enables female principals to enact their leadership practices in a more productive manner (Shapira et al., Citation2010).

Theme 4: Leadership perceptions, significance and enactment

The female leaders’ understanding of leadership, the characteristics they develop and display, and the practices they enact once they have been appointed in senior positions is another theme that was very prominent in the empirical research covered by our systematic literature review.

Women’s personal characteristics and sense of agency, what Arar (Citation2018b) labels as being ‘a superwoman’ (p. 758), constitute their leadership persona. Women are self-determined, possess considerable willpower to succeed, are agentic and persistent, while exploiting all possible opportunities for academic achievement and professional growth and development. Consequently, their leadership styles develop and transform at various career stages. Arar and Abu-Rabia-Queder (Citation2011) explain that at the start of their career, these female principals adopt an authoritarian style that transformed into a more ‘feminine’ one mid-career as they develop relationships with teachers and other stakeholders. As they advance in their career, they consolidate their expertise in ‘performing their managerial role’ (Arar and Abu-Rabia-Queder, Citation2011, p. 423) based on their initial period of dealing with pedagogic challenges and supporting innovation. They express empathy (Arar & Oplatka Citation2018), while behaving according to a stereotypically feminine paradigm exhibiting tolerance, care, intuition, and support (Taleb, Citation2010), what Baroudi and Hojeij (Citation2021) refer to as servant leadership. Arar (Citation2017) notes the development of their emotional dynamics across their leadership career stages. The first stage of transition from teaching to leadership is characterized by emotional suppression to appear strong and demonstrate control. The second ‘establishment’ stage allows them to be calm, assertive, and connected, distancing themselves from vulnerability while working on staff relations. At a more advanced career stage, principals are more compassionate while making a more concrete move toward collective leadership. This transition in leadership style, followed by school reform, is also reported by Shapira et al. (Citation2010), especially in light of their developing professional relationships with teachers and students, which involves the whole school community in decision-making (Arar & Shapira, Citation2012). According to Vogel and Alhudithi (Citation2021), these female principals practise instructional leadership and exercise autonomy in enacting changes to educational processes and pedagogies catering for students’ needs. It is a transformational leadership style (Baroudi, Citation2022), with an emphasis on vision, the development of the individual and idealized influences.

In a study exploring Arab school principals in Israel, ‘pavers of the way’ (p. 315), Arar (Citation2010) utilizes the narrative tools of tropes and epiphanies to demonstrate how they position themselves in relation to both the micro and macro levels in their professional self-construction, to behave like ‘men in skirts’ (Taleb, Citation2010, p. 296). Early leadership opportunities in pursuing compulsory schooling allow one participant to ‘get out of the village’, and further, to feel obliged to ‘behave like men’, turning her not to be ‘the Arab man’s dream’ (Arar, Citation2010, p. 322), having to subsequently fight for her school leadership position and being ‘the first’, accused of ‘stealing it from the men’.

Upon appointment, female school principals regard themselves as agents of social justice, especially those from a marginalized social standing (Arar, Citation2018a), whereby female leaders challenge the existing social order, while encouraging discourse and dialogue as community leaders (Arar & Shapira, Citation2012). They ‘break through prevailing social norms … desiring to bring about change in their society’, seeing themselves as the ‘flag-bearers’ while aspiring to become role models (Arar Citation2018b, p. 319).

However, women leaders as harbingers of reform and social justice agents do not unfold similarly in all Arab states. Al-Oraimi (Citation2013) explores the social standing and status of Emirati women educational leaders in the UAE, arguing how despite being more active in a feminine environment due to a segregated educational system which only enables them to focus on female students, they play leadership roles in the society as a whole by rebuilding new understandings of female leadership in the community. However, they regard themselves as totally reliant on the state for their position, thus unable to develop a sovereign identity, which also restrains them from networking and collective presentation in the public sphere. Women promoting other women dependent on their relative social power within the education system are an issue similarly reported by Addi-Raccah (Citation2006). Where female school leaders had more social power, stemming from their demographic dominance and normative support in the school’s broader social environment, they could challenge gender inequality and promote their female coworkers to positions traditionally perceived as male-type jobs.

Cultural influence on leadership enactment is explored by Al-Suwaihel (Citation2010) among Kuwaiti female leaders constructed on culturally based personal experiences, culturally based professional experiences, and the new cultural experiences acquired as a result. Females managed to deal efficiently with their increasing job demands, being consistent in their private and public personalities, while challenging obstacles to achieve their goals. Professionally, they were educationally accomplished, balanced professional and family experiences, improved their social status, while applying life experiences to the work environment, supporting the principle of the right person for the right job, irrespective of gender. This brought to the fore cultural influences, interactions and reforms that involved female leadership in Kuwait, namely media, globalization, religion, traditional perspectives, and male perceptions.

Discussion

This section provides a synthesis and discussion of the findings from both the descriptive and narrative analyses in light of the existing literature. The section begins with the descriptive analysis.

Our descriptive analysis revealed that the literature on female leadership in the Arab region is relatively thin, indicating that this area of research remains largely underdeveloped, a finding that aligns with previous Arab EDLM reviews (Hammad & Hallinger, Citation2017; Oplatka & Arar, Citation2017). This has been compounded by an imbalance in the geographical distribution of the Arab female leadership scholarship, with the Arab sector of Israel and Saudi Arabia being the most frequently studied contexts. While consistent with the broader trends in Arab EDLM research (Atari & Outum, Citation2019; Hallinger & Hammad, Citation2019), this is problematic as it can limit our ability to draw comprehensive conclusions, thus posing a challenge to developing a more balanced and contextually representative knowledge base of female leadership in the Arab world. Therefore, there is a need for more country-specific studies that can provide insights into the unique challenges and opportunities associated with female leadership in each Arab country. This recommendation aligns with arguments pertaining to the idiosyncrasies present in the Arab world (Hammad et al., Citation2022) and the fallacy of Arabism (Salibi, Citation1988) as a concept uniting all Arab countries at the level of culture, religion, and socioeconomic context.

In contrast to prior Arab EDLM reviews showing the prevalence of quantitative research methods (Hammad & Hallinger, Citation2017; Hammad et al., Citation2022), one promising feature of the female leadership literature is that the majority of the studies were qualitative in nature, reflecting a growing interest among EDLM scholars in understanding the sociocultural aspect of female leadership and providing rich and nuanced insights into the lived experiences of female leaders in the region. However, the finding that most of the studies were empirical in nature is alarming, as it may hinder the development of female leadership into a mature area of inquiry (Hallinger & Bryant, Citation2013). Therefore, there is a need for a more balanced composition of empirical and conceptual literature to build a mature knowledge base that can deepen our understanding of Arab female leadership.

In addition to being mostly empirical in nature, the level of conceptualization in the reviewed studies was limited. Being an intersubjective contextual phenomenon (Blackmore, Citation2013; Grogan & Shakeshaft, Citation2011; Shah, Citation2020), female leadership in the Arab world could be better understood through use of social theory lenses that would provide more criticality to the analysis of the results (Mifsud, Citation2023).

Our narrative analysis reveals that female educational leadership in the Arab world suffers from the regressive effects of the failure of most Arab countries to shift their governmental and political frameworks toward greater equality. This finding, as well as others, can be understood by examining the manner in which sociocultural factors, being a pivotal theme in the review, connect with the remaining three themes of the study: the challenges, leadership perception and persona, and interestingly the enablers of women leadership in the Arab world.

Our systematic review demonstrates that male domination and its subsequent gendered societal roles constitute the main arenas where sociocultural factors exert their normative power over women leadership progression and practice. These findings concur with literature emphasizing how normative roles continue to affect female leadership (Blackmore, Citation1996; Fuller, Citation2014; Grogan & Shakeshaft, Citation2011; Shah, Citation2020). The narrative analysis also reveals that these normative roles in the Arab region are strengthened by patriarchal traditions becoming embedded in Islamic legislations and rules hindering women; creating a double bias of traditions and religion that women have to endure. While this hindrance contradicts research highlighting the role of Islam, as a religion, in empowering women (Samier, Citation2016), it is well situated in studies underlining how religious interpretations are used to reinforce patriarchal discourses and sociocultural norms (El-Saadwai, Citation1997; Mernissi, Citation1991).

The review shows that the patriarchal interpretation of Islam about women’s position in society supports gender inequality, which resonates with a number of studies conducted in Muslim non-Arab contexts (e.g. Shah, Citation2020). While these patriarchal interpretations of Islam represent one aspect of the bias against women leadership in the Arab region, traditions represent the other. The narrative review shows that the male domination gains its power from tribal and/or familial customs and traditions governing a large proportion of the Arab world. Leadership within family, hamulla, and tribe is exclusively male (Abalkhail, Citation2017; Al-Oraimi, Citation2013; Alomair, Citation2015; Arar, Citation2018b; Karam & Afiouni, Citation2014; Shapira et al., Citation2011). This male domination is well situated within the traditional practices and cultural norms of the tribal community existing in the Arabian Peninsula before the rise of Islam but has contributed to the conservative orientation toward women within the Islamic faith (AlAjmi, Citation2001). This conservative orientation toward women is highlighted in our narrative review as one of the main obstacles to women leadership, as the studies reviewed (Arar & Oplatka, Citation2016; Ensour et al., Citation2017; Romanowski & Al-Hassan, Citation2013) reported abundantly on the family obligations and caretaking responsibilities being primarily ‘female’, and males being the leaders of the family and its breadwinners. Similar findings are reported in international literature (Blackmore, Citation1996; Grogan & Shakeshaft, Citation2011; Vella, Citation2022) and Arab literature (e.g. Jamali, Sidani, and Saffiedine, Citation2005).

Moreover, the solidarity that tribal and familial (Hamulla) communities show toward one another was also reported as one of the factors affecting women leadership (Arar & Oplatka, Citation2016). Karam and Afiouni (Citation2014), Abalkhail (Citation2017), Al-Oraimi (Citation2013), Alomair (Citation2015), Arar (Citation2018b) and Shapira et al. (Citation2011). These forms of solidarity have been described by Ibn Khaldun as ‘alasabiyya alqabaliyya’ (Ibn Khaldun, Citation2015) and are particular to the Arab world (AlAjmi, Citation2001). Participants in the studies reviewed (e.g. Arar, Citation2018b; Karam & Afiouni, Citation2014) reported that they had to remain sensitive to the demands of the male members of their own tribe and that of their husbands’. While it could be argued that tribal pressures are exerted on both men and women, women’s absence from any leadership roles in their tribes, or hamulla renders this tribal pressure a form of further submission to a value a system that prioritizes male rights. This is often justified by kinship values which are usually reinforced by religious beliefs (Joseph, Citation1996), thus further propagating the submissive status of women in the society and posing idiosyncratic hindrances to women leadership in this region. This ‘patriarchal social contract’ is still strongly reinforced in the Arab world (Moghadam, Citation2004) and is not necessarily a reflection of the Muslim culture (Effendi, Citation2003; Samier, Citation2016).

The patriarchal dominance featuring Arab societies has widened the gap between women’s private and public spheres, further highlighting the gendered socially constructed roles. Women are expected to be the submissive followers and caregivers in their private spheres and in the public spheres they are in positions requiring them to lead and take action. These different and contrasting roles have created a level of dissension dissention. Our review shows that women exerted effort in order to balance between these two dichotomous roles and this resonates with international literature of women leadership (Blackmore, Citation1996; Grogan & Shakeshaft, Citation2011; Shah, Citation2020) and women leadership in international contexts. Our review (Abalkhail, Citation2017; Al-Oraimi, Citation2013; Alomair, Citation2015; Arar, Citation2018b; Arar & Oplatka, Citation2016; Karam & Afiouni, Citation2014; Shapira et al., Citation2011) reveals that one of the socio-religious notions that is further contributing to the divergence between women’s private and public spheres is qiwama, which states that men are responsible for their women (sisters, daughters, cousins, wives and mothers) and are the leaders of the household. This notion has trickled down to rules and legislations in some Arab countries where women can only travel with a Mahram (Almansour & Kempner, Citation2016; Ensour et al., Citation2017), which may hinder their ability to learn and develop professionally. In tandem, the review also highlights that the effects of socio-religious discourse are evident in hindering the implementation of policies aiming to improve women’s equitable access to the labor market in general and to leadership positions in particular (Abalkhail, Citation2017; Al-Oraimi, Citation2013), as these policies remain ink on paper due to the power of these normative discourses. Our findings concur with studies in women leadership conducted in Muslim non-Arab contexts (Shah, Citation2020).

Within the restrictive socio-cultural and religious context in which women leaders in the Arab world operate, the narrative review highlights a number of enablers that reportedly helped these leaders navigate the challenges they encountered. Careful examination of the ‘enablers’ in light of their context reveals that these enablers are grounded in the male domination. Results of the review reveal male support (father and husband) being a major enabler for women leadership; a finding resonant with a number of studies in other contexts (Samier, Citation2016; Shah, Citation2020; Maheshwari, Citation2021; Maheshwari et al., Citation2023) While male support is indeed an enabler, it is also a manifestation of patriarchal domination; none of the women in the articles reviewed spoke about a female role model, or even their mothers as a source of empowerment. Moreover, we also argue that this male support, especially when it is from the husband, may become a challenge (). The narrative analysis (Karam & Afiouni, Citation2014) highlights the stigma associated with men who allow their women to work and more so whose women hold higher ranking positions than themselves. This finding resonates with studies showing that women have to remain cognizant of advancing in leadership positions, as this might make men ‘unhappy’ and challenges their authority (Shah, Citation2020) which is in sync with the Islamic and socially constructed practice of Qiwama.

Another enabler that the review reveals is the women’s personal attributes, including resilience, agency, focus, and determination. Women in these studies (Arar, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Arar & Shapira, Citation2016) perceive themselves as change agents, which has pushed them toward enduring the barriers in order to excel and progress in their leadership positions. This is consistent with international literature (e.g. Kemp et al., Citation2017). However, while these personal factors may be used as a means for identifying exceptional or successful leaders, in the case of female leadership they represent the bare minimum required from women leaders to succeed in male dominated societies. This corresponds with the argument that women in such contexts need to be superwomen to succeed in leadership (Arar, Citation2019). Being a superwoman comes with an expensive bill of emotional distress as women continue to struggle to reconcile the dissonance between their private and public spheres. It is here that the enabling personal factors that were helping women succeed in their leadership positions become challenges preventing them from further pursuing their leadership careers due to burnout and emotional distress, hence the double-edged arrow in .

The theme of women leadership practice, perception and persona can be best understood using international literature delineating leadership as traditionally a male field, which is further compounded by male domination in Arab societies.

The review indicated that the progression of women leadership in the Arab world is characterized by initial stages where women leaders exhibit more ‘masculine’ qualities, with later stages showing a greater connection to feminine aspects. This progression pattern is similar to that reported in international literature (Grogan & Shakeshaft, Citation2011). In tandem, the narrative review also reveals that the leadership perception that women are developing of successful leadership is mostly associated with leadership being constructed as a ‘male’ social phenomenon. Women in the studies reviewed frequently reported on the need to ‘regulate’ and ‘suppress’ their emotions in order to be perceived as ‘powerful’ and effective leaders (Arar, Citation2017). Once again, this aligns with international literature depicting leadership and management as being primarily masculine (Kaparou & Bush, Citation2007).

Conclusion

The current systematic review was conducted with the aim of understanding female leadership in the Arab region, a context that is relatively under-represented in the global EDLM scholarship. Drawing on a dataset of 40 relevant sources published between 2000 and 2022, the study conducted quantitative and qualitative analyses to explore the status quo of female leadership research in Arab societies and identify the main themes addressed in this research. It is hoped that the findings of this study will provide a foundation for future research on female leadership in the Arab region and similar societies and guide policymakers, researchers, and practitioners in their efforts to promote greater gender equity in educational institutions. In this concluding section, we provide general insights about female leadership in the Arab world, drawing from the findings of our review.

Results indicate that while there are genuine efforts to help improve the participation of women in leadership positions, the status quo still oozes with structural and cultural hindrances preventing women from effectively progressing into leadership positions. While some of these structural and cultural challenges are common to other international contexts, some are unique to the Arab world as these hindrances reflect the double bias women face due the patriarchal interpretation of the Islam in the region and the male dominated cultural and social norms propagating gendered social roles and placing women at an inferior level in leadership compared to men.

Findings from our review have implications for policy, practice, and research. The narrative review showed that in male-dominated societies, female leaders have been embracing a persona of superwomen as being the norm for successful women leadership. It is recommended that future research explores the effect of the dichotomous public and private spheres on women’s emotional health and leadership effectiveness and practices.

Our descriptive analysis, on the other hand, revealed a lack in the use of conceptual tools. The use of these conceptual tools is expected to allow for the development of contextually grounded theories that would contribute to a critical understanding of female leadership in the Arab world, thus responding to existing calls in the literature for a more culturally relevant understanding of female leadership (Shah, Citation2006, Citation2020; Sidani, Citation2005). Therefore, at the research level, there is a need for conceptual papers that can contribute to the theorization of female leadership in the Arab world. This is consistent with literature calling for a more contextually grounded understanding of feminism (e.g. Sidani, Citation2005).

Moreover, providing such a contextual conceptualization is essential to understanding the interplay between female leadership and the culture in which it is enacted. Understanding this interplay is crucial for policy development aiming to improve women's participation and access to leadership positions as it will enable policy-makers to understand the way policies claiming to provide equity and equality for women are [not/mis] implemented and in turn find ways to ensure their implementation when they might run against certain social norms.

At the level of practice, the review shows that the main sources of support for women leaders are males, and there was no indication of any ‘female’ role models or mentors. It is therefore recommended that women leaders in the Arab world are provided with opportunities to connect with senior women leaders in the field and develop a mentoring relationship with them. This recommendation resonates with calls from the international literature indicating the lack of female mentors for women leaders (Blackmore, Citation2013; Moorosi, Citation2012; Torrance, Citation2015). In the same vein, and due to the idiosyncratic challenges and nature of female leadership, leadership preparation programs and in-service programs in the Arab world need to be trailered toward helping women understand and overcome these challenges.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yara Yasser Hilal

Dr Yara-Yasser Hilal is a Lecturer (Assistant Professor) of Educational Leadership Policy studies in the School of Education and Social work at University of Sydney-Australia. She holds a PhD in Education from the University of Leicester, UK, and a Master’s degree in Educational Leadership from McGill University, Canada. She is a member of the British Educational Leadership, Management and Administration Society (BELMAS) and a member of the Lebanese Association of Educational Studies (LAES). She has led and participated in a number of funded research projects in the areas of principal and teacher agency and teacher leadership and knowledge production in the field of educational leadership in the Arab world. Her areas of research include school-based improvement, educational leadership and management, teachers’ and principals’ continuous professional learning, and critical and cultural approaches to leadership. Her international publication outlets include Educational Management, Administration & Leadership (EMAL), International Journal of Leadership in Education; Educational Action Research, and International Journal of Educational Research.

Denise Mifsud