ABSTRACT

This study explores how Complexity Leadership Theory (CLT) can advance the understanding of academic leadership in HE during a time of crisis and uncertainty. A qualitative methodology was applied to address the research question, ‘How do academic leaders in higher education understand leadership during a crisis?’ We used duoethnography to garner data through recorded conversations and other artifacts about our leadership experiences as associate deans for learning and teaching. Drawing from the three CLT leadership strands (operational, entrepreneurial, enabling) for analysis, we show enabling leadership as critical to doing operational and entrepreneurial leadership. Additionally, we demonstrate that enabling leadership, beyond its functional role, is suffused with emotion work and care. Uniquely, our findings suggest the need to extend CLT’s enabling leadership to integrate compassionate leadership for personal wellbeing and to support others during challenging times. Moreover, the study contributes to existing CLT knowledge by providing useful insights to extend the concept of enabling leadership by incorporating ways of thinking and approaching leadership practices relevant to the current higher education context.

Introduction

Dialogue between two associate deans in Higher Education (HE) on leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic identified that many of the challenges represented an amplification of existing experiences of working with complexity, uncertainty and a context of continual change (Howden et al., Citation2021; Watermeyer et al., Citation2022). The paper uses the context of COVID-19 through the lens of Complexity Leadership Theory (CLT) to make sense of leadership applicable to post-pandemic times of crisis. The aim of this paper is to explore how academic leaders in higher education understand leadership during a crisis. We anticipate this will interest researchers and practitioners in HE and wider educational settings.

Academic leaders are scholars who take on managerial or administrative responsibilities. Such roles include leadership within and external to the institution and include positions such as faculty and department heads, leaders of research or teaching, directors of programs, and leading committees and working groups (Grajfoner et al., Citation2022). Academic leadership in higher education is demanding and can include a myriad of complex tasks such as curriculum planning, timetabling, teaching and assessing learning, budget management, resource management, coordination, and collaboration (Parpala & Niinistö-Sivuranta, Citation2022; Quinlan, Citation2014). The pandemic exacerbated the already challenging and complex responsibilities of academic leaders. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic was unparalleled, rendering ‘traditional rules, policies, procedures, and guidelines’ outdated or impractical (Schmidt et al., Citation2022, p. 46). More than usual, leaders in HE had to swiftly make decisions and act to manage extensive educational communities, addressing the increased needs of students and staff, all while considering the broader societal requirements (Dumulescu & Muţiu, Citation2021). Moreover, this rapid decision-making consisted of minimal, ‘if any, available data’ to inform those decisions (Schmidt et al., Citation2022).

The pandemic was a time when new ways of working, learning, and leading emerged; it was a period of intense challenge and a time when academic leadership was highly visible. With that in mind, we sought to explore ways of thinking about and ‘doing’ leadership through this period using the reflexively captured experiences of two associate deans.Footnote1 Our approach was to apply CLT as a conceptual lens, seeking to understand its potential value in explaining academic leadership (Uhl-Bien & Arena, Citation2017) when considering ways of thinking, knowing, and practising.

Notwithstanding the pandemic, turbulence and uncertainty within global HE are known to have substantially increased (Watermeyer et al., Citation2022). This type of environment is commonly referred to using the acronym VUCA – volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous (Lemoine et al., Citation2017; Sarkar, Citation2016). VUCA environments are characterized by rapid change, unpredictability, limited – or lack of – knowledge, extensive interconnected parts (Taskan et al., Citation2022), and wicked problems that evade straightforward solutions (Sempiga & Van Liedekerke, Citation2023). Within HE, LeBlanc (Citation2018) criticizes the hierarchical nature of HE that is also ‘highly regulated and fueled by third-party payers’ whilst emphasizing the need for agility if HE is to survive against the velocity of change (p. 23). Against the backdrop of global challenges and a VUCA environment, questions surrounding the purpose of HE, now and in the future, arise (Gaus et al., Citation2022). Therefore, this paper is relevant to global leaders in HE. The continuous global socio-cultural-political shifts influence practices within Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) and demand leadership that can work with complex challenges.

Change, adaptability and innovation in HE are therefore crucial for competitive advantage and continuous institutional progress in today’s societies (Kucharska & Rebelo, Citation2022). Universities are operating in volatile times with increasing complexities, so they must respond faster than ever before to prepare for the unknowns and ‘remain relevant’ (Macken et al., Citation2021, p. 9). As universities face turmoil, HE leaders must adapt to sustain, thrive, and circumnavigate the real threats of universities becoming irrelevant (Suresh, Citation2015) by taking advantage of potential new opportunities.

Effective leadership across an HEI is perceived as crucial for good functioning, particularly considering the dynamic and complex nature of such organizations and the range of stakeholders involved (Carvalho et al., Citation2022). Regardless of the leadership level, leadership service in HE typically incorporates activities such as a ‘manager, futurist, mentor, and academician’ (Carvalho et al., Citation2022, n.p.). Yet, reflecting the sector in general, leadership in HEIs is in a state of flux brought about by competing demands and issues associated with uncertainty (Mowles et al., Citation2019). This is coupled with continuing drives to influence teams toward greater performance and organizational success (Carvalho et al., Citation2022) whilst advancing multi-faceted missions of learning, research and social responsibility (Grant, Citation2021). To address these notable demands and challenges, regardless of geographical location, HE leaders must adopt an approach that embraces complexity to drive necessary change and implement ‘systemic responses’ (Siemans et al., Citation2018, p. 42). CLT offers a means to explore leadership in practice and understand how leadership can positively influence unpredictable and dynamic HE environments.

The pandemic highlighted the potential impact of crisis and unpredictability on educational leaders and their leadership methods. Regarding crisis, and drawing from Callahan (Citation1994) and Gigliotti (Citation2019), we define this as a time of intense difficulty, trouble or danger involving a situation that poses a significant threat to individuals, communities, organizations, or societies as a whole that requires immediate and decisive action. Characterized by urgency, uncertainty, disruption, risk, and impact, crises can arise from various sources, including natural disasters and public health emergencies, amongst others. Evidence suggests that such complexity and uncertainty are here to stay (Adobor et al., Citation2021; Lemoine et al., Citation2017), so there is a need to explore the ways in which HE leaders from across the globe understand and interact with such volatile environments. This paper seeks to explore this context of leadership in uncertainty, addressing the question ‘How do academic leaders in higher education understand leadership during a crisis?’

Theoretical framework

Leadership theories exist in abundance, and educational leadership is no different; scholars have studied educational contexts through many theoretical lenses. In this research, we use Uhl-Bien and Arena’s (Citation2017) Complexity Leadership Theory (CLT) as an analytical framework. Since its conception (Uhl-Bien et al., Citation2007), the framework has been recognized as valuable across various sectors - for example, in healthcare (Hanson & Ford, Citation2010) and education (Beresford-Dey et al., Citation2024). Set within a recognized highly complex environment, Hanson and Ford (Citation2010) argue that healthcare industry leaders require leadership capabilities congruent with CLT. Such leaders have the capacity to cultivate skills that foster attributes such as ‘interaction and interdependence’, thereby ‘fostering collaboration, innovation, and organizational learning’ (p. 6594). Also, albeit in the primary school system, Beresford-Dey et al. (Citation2024) used mixed methods to explore leadership, whereby the authors reported a need for a culture shift. Consistent with CLT, this shift concerned a realignment from top-down leader-centric leadership to a collective endeavor that balances formal and informal structures resulting in adaptation and knowledge sharing across networks. Through a CLT lens, the authors recognized the potential to consider school leaders as social intrapreneurs rather than entrepreneurial (Beresford-Dey et al., Citation2024). In these two studies, CLT was found to be useful as a framework to examine the challenging nature of leadership functions, the collective nature of leadership, and leadership strategies within contexts with high levels of complexity.

Complex environments such as HEIs consist of interrelated elements that influence a system’s structure; this structure results from the system’s history and its present state alongside other contextual interactions. These interactions require responsive, agile leaders who balance managing conflict with the need for fluid and dynamic change (Tsai et al., Citation2019). Owing to the complex nature of HE, CLT offers an ideal framework to conceptualize leadership in knowledge-producing organizations. We consider CLT as a potentially valuable lens to recognize the continuous shifts within HEIs and their ‘ever-growing spectrum of roles’ and associated leadership duties (Sánchez-Barrioluengo et al., Citation2019, p. 470).

CLT derives from its parent concept, Complexity Theory. Originating in the natural sciences, Complexity Theory embeds change through concepts such as adaptation, evolution, and survival (Hager & Beckett, Citation2022; Morrison, Citation2002). Change in complex systems is characterized by a ‘non-linear suddenness’ where prediction through knowledge of the system or initial conditions cannot be assumed (Stacey, Citation1996, p. 303). Complexity can be understood as a theory of adaptation and change (Hager & Beckett, Citation2022; Morrison, Citation2002; Uhl-Bien & Arena, Citation2017; Uhl-Bien et al., Citation2007) that allows us to explain change within a system alongside behaviors to thrive in turbulent, unpredictable environments. Like other social science scholars, we embrace complexity due to the emphasis on ambiguity, interdependency, non-linearity, uncertainty, and unpredictability (Beresford-Dey et al., Citation2024; Cilliers, Citation2000; Hager & Beckett, Citation2022; Regine & Lewin, Citation2002); properties that are prevalent in knowledge-intensive organizations, such as HEIs.

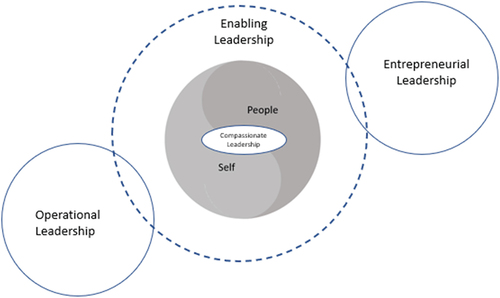

CLT stands aside from some of the traditional leadership texts that focus on the leader’s traits, personal attributes and decision-making approaches (Marion, Citation2008). These early typologies of leadership have often overlooked that leadership goes beyond the actions of individuals. Instead, it is intricately woven into a complex interplay of multiple interacting forces (Schophuizen et al., Citation2022). Similarly, according to Whittaker and Montgomery (Citation2022), conventional academic leadership models primarily rely on managerial and transactional methods. These approaches often reinforce individual success within the existing structures rather than promoting values-based leadership centered on collective institutional or sustainable endeavors. More contemporary leadership models regularly look toward approaches that support collaborative, institution-wide efforts and innovations that prioritize leadership from a community stance. Leadership through a CLT lens is considered a collective endeavor (Howden et al., Citation2021; Gordon & Cleland, Citation2021; Uhl-Bien & Arena, Citation2017; Uhl-Bien et al., Citation2007) and a shift from the top-down traditional and transactional leadership typology. From the non-leader-centric position, Uhl-Bien and Arena (Citation2017) identify three leadership functions within the CLT framework: operational, entrepreneurial, and enabling leadership ().

Figure 1. A simplified diagram of the complexity leadership model adapted from Uhl-Bien and Arena (Citation2017).

In operational leadership, individuals plan and oversee strategies to meet a vision within formal organizational structures. Whilst Uhl-Bien et al. (Citation2007) had originally proposed this strand as administrative leadership, according to Malikhah (Citation2021), operational leadership goes further through the communication processes that become guiding rather than directive, thus inspiring team members and reducing controlling ‘communication patterns’ (p. 4645). However, it is also important to note that operational leadership in higher education aligns with the strategic leadership and management of finances, quality, resources, space, and staff, which is found in many large organizations (Yielder & Codling, Citation2004). In Uhl-Bien and Arena’s (Citation2017) CLT framework, operational leaders play a crucial role in transforming emerging ideas into organizational systems and structures by supporting, aligning, and implementing initiatives.

Entrepreneurial leadership is associated with generating novelty (such as new practices, products and services) through creativity and innovation by driving a collective approach within cohesive teams (Uhl-Bien & Arena, Citation2017). Central to entrepreneurial leadership is leading processes to produce results efficiently by maintaining alertness to capitalize on opportunities and exploit resources from various stakeholders (Leitch & Volery, Citation2017). By embracing entrepreneurial principles and strategies, such as innovation, risk-taking, experimenting, networking, and persistence, HEIs can effectively navigate challenges and take advantage of opportunities to attract international students and enhance research collaborations, thereby sustaining financial stability and academic excellence. Therefore, entrepreneurial leadership has emerged as advantageous for HEIs when facing increasing uncertainty and rapid changes.

Enabling leadership lies between the operational and entrepreneurial roles (Uhl-Bien & Arena, Citation2017); it ‘combines the ambidextrous tasks of exploration and exploitation’ (Schulze & Pinkow, Citation2020, p. 2). Within this interfacing space, leaders intentionally cultivate and amplify creative, adaptive spaces through creating, mobilizing, and brokering networks (Boylan, Citation2016). Enabling leaders work to catalyze this activity by utilizing systemic and collaborative forces to encourage the liberation and dissemination of collective knowledge, thus activating adaptive responses (Beresford-Dey et al., Citation2022). As such, within higher education, enabling leadership is crucial in balancing entrepreneurial and operational leadership to build a resilient and adaptive academic community capable of effectively navigating challenges and change.

In the UK, universities are currently classified as not-for-profit institutions serving households in the UK national accounts (Gravatt, Citation2023; Office of National Statistics, Citation2023), and therefore bear a resemblance to public sector organizations in that, despite the view that HEIs must demonstrate agility and innovation, unlike private sector organizations, they can be hampered by overly bureaucratic systems, thus inhibiting ‘new ways of thinking and operating’ (Uhl-Bien, Citation2021, p. 1401). According to Uhl-Bien and Arena (Citation2017), the concepts of order response and adaptive responses are important features of CLT. Order response is where, in times of complexity, senior leaders and managers respond with order and control, pulling back to ‘equilibrium’ (p. 10), often through accountability. Meanwhile, adaptive responses resist the urge to impose rigid structures and instead leverage the collective intelligence inherent in groups and networks through emergence. Emergence arises when there is a critical mass of diverse components, leading to the formation of clusters and the emergence of novel phenomena beyond individual actions (Beresford-Dey et al., Citation2024). Whilst we cannot disregard the bureaucratic and hierarchical nature of the system in its entirety, for many, interdependence, networking, collaboration, and partnership working are inherent in HE leadership practices (Beresford-Dey et al., Citation2022; Leithwood, Citation2019), thus clearly aligning with CLT. Yet, research connecting HE and CLT remains scarce, and building from our initial reflective work (Beresford-Dey et al., Citation2022) and the value of CLT previously noted in other areas, we aim to explore its value in the context of HE leadership.

Exploring CLT at a time of disruption

The global pandemic of COVID-19 challenged university leaders to respond quickly and carefully to support students and staff as public health measures demanded social distancing. After the initial phases of emergency measures, attention turned to reviewing how learning, teaching and research activities could be sustained with new working, teaching and learning. The early phases of the pandemic were characterized by the oversight of multiple disrupted communities, processes and systems. We identified this as a point in time when there was a heightened challenge to stabilize, innovate and enable, a period that could develop our understanding of academic leadership through the CLT lens.

Methods

The study addressed the question: How do academic leaders in Higher Education understand leadership during a crisis? A duoethnographic approach was used to explore two of us (LM and SH) who were associate deans for learning and teaching during the early part of the pandemic (March – November 2020). Both of us are white British women who had each worked in HE for almost 20 years. When we started collecting data, LM had been associate dean for 18 months, and SH had held two different associate dean roles over five years.

Duoethnography has grown in popularity over recent years (Burleigh & Burm, Citation2022). An extension of autoethnography (Savin-Baden & Howell-Major, Citation2013), duoethnography locates the researchers as the ‘site of the research’ (Breault, Citation2016, p. 778); it is a collaborative research methodology. It consists of two researchers sharing their lived experiences, often resulting in transformation as ‘new interconnections are made’ through blending narratives and ideas (Norris & Sawyer, Citation2012, p. 11). Emergent, organic, and dynamic dialogue enables researchers to better understand their contexts (Norris & Sawyer, Citation2012) and culture and surface ways of thinking and taking action (Savin-Baden & Howell-Major, Citation2013).

This tandem working enables researchers to jointly explore and chronicle assumptions, current issues, and experiences through ‘descriptive narration, stories, and examples’ (Burleigh & Burm, Citation2022, p. 1). The value of duoethnography is that joint reflexivity through discussion, as opposed to undertaking such activities as an individual, may reveal more about the situation or context (Savin-Baden & Howell-Major, Citation2013). Our use of duoethnography emerged from initial peer support work activities. LM and SH critically reflected on issues and actions and supported each other’s reflections on academic leadership of learning and teaching. It soon became clear that what began as an activity for mutual support could hold additional value and enable insights into CLT if formalized as a duoethnographic study.

We recognized the limitations of duoethnography, such as non-corroborated accounts of scenarios and the challenge of distinguishing between recollection and interpretation (Savin-Baden & Howell-Major, Citation2013). To limit the time between lived experiences and reflection-in-action, the reflective dialogue between SH and LM occurred weekly to support timely data generation (Schön, Citation1983). Our colleague (MB-D), who has expertise in qualitative research, educational leadership and complexity leadership, joined the research team post-data generation to bring an outsider view to data analysis and interpretation. MB-D knew the study’s context as an academic in the same institution, but could maintain a helpful distance from the accounts as they did not hold the same position and were not in common groups, teams or departments.

The study was carried out between the end of March and late November 2020, during which period of the pandemic we collected data about our experiences of leadership which comprised of recorded video call conversations (using Microsoft Teams); written reflective posts, gathered asynchronously (also using Teams); and photos and other images that represented our mood, thoughts, challenges and achievements at points in time over each week (for example, ). This approach enabled a longitudinal reflective dialogue to be captured to help deepen our understanding of how our leadership thinking and practices unfolded during the time of disruption, drawing together context, person, place and time.

Image 1. ‘It’s all bit samey!’ – an image capturing similar footwear depicts the repetition of activities during the pandemic (Photograph taken by Howden (Citation2020), published in Howden et al. (Citation2021).

As researcher participants, LM and SH come from different disciplinary and academic backgrounds. Throughout the research, we both held associate deans for learning and teaching positions in schools that deliver health-related degree programs leading to professional registration or postgraduate awards for registered health professionals within one medium-sized, research-intensive institution in Scotland, United Kingdom. As a co-researcher, MB-D brought expertise and did not participate in the data generation (i.e. the reflective dialogue and the collecting/sharing of images) but was integral to the data analysis and interpretation. Ethical approval was granted by the institutional Research Ethics Committee (ref: E2020-117). A particular aspect of the ethical considerations was being conscious that the discussions included reflections on interactions and relations with others (i.e. colleagues, students, and wider stakeholders) and taking care to mitigate any potential to identify these individuals or associated organizations.

The voice recordings were transcribed verbatim and analyzed both manually and using NVivo. We used Ritchie and Spencer’s Framework Analysis (Ritchie & Spencer, Citation1994) to thematically analyze the data, including recordings, images and postings. To enable the ‘sifting, charting and sorting material according to key issues and themes’ (Ritchie & Spencer, Citation1994, p. 177), we used the five-stage systematic process of Framework Analysis, adapted to reflect the way we merged stages three and four, indexing and charting:

Familiarization with data: We all became immersed in the data through individual and group interactions to ensure we gained an in-depth and holistic understanding of its meaning. We listened to the discussions individually, engaged in word-for-word transcription, and read the transcripts multiple times. We also viewed and reflected on the images and written reflections. To enhance our common understanding and explore differences, we spent time with each other exploring our individual familiarization work, including a day together in person.

Identifying a thematic framework: We used CLT and its three leadership strands of operational, entrepreneurial, and enabling to frame the data analysis. We took a pragmatic approach to developing the codes by identifying a series of codes that aligned with one or more CLT strands, as well as using an open approach to coding sections of text which seemed important or recurrent but not immediately or obviously related to the CLT strands, for example, approaches to managing emotions during conversations. After initially working individually, we triangulated our coded material to develop an ‘index’, i.e. a comprehensive set of codes that could be used to systematically match sections of the transcripts to the codes. Coded sections could include relatively large sections of dialogue between LM and SH and related images.

Indexing and charting: As part of an iterative process, we returned to individual work, applying the index to each transcription and annotating the data manually (SH and LM) or through NVivo (MB-D). We then merged our indexes using Microsoft Excel to facilitate an in-depth discussion and reach a common understanding. We reflected on the data together, challenging each other and working together to make sure the analysis reflected a common understanding that was trustworthy and credible. Next, we derived groups of codes based on the subject areas, using an interpretive approach to our analysis that was consistent with narrative methods (Riessman, Citation2008). We frequently returned to the original dataset to verify our groupings and preliminary themes and ensure our interpretation was true to the data.

Mapping and interpretation: Finally, we reviewed the data as a whole again. We mapped out the themes by identifying patterns and connections, taking into account explanations of our interpretations, which enabled us to recognize expected and unexpected themes.

The data analysis stage was characterized by reflexivity, continually self-assessing and reviewing our impact as researchers. Reflexivity is an essential aspect of rigor in the qualitative research process, enabling the identification and challenge of personal presumptions, beliefs and histories and how these might impact the research (Streubert & Carpenter, Citation2011). Given the duoethnographic nature of the research, it was also particularly important to be mindful that SH and LM were interpreting their own data. Reflexivity helps to ensure integrity in the data analysis, contributing to a credible interpretation of the data (Bradbury-Jones, Citation2007). Additionally, throughout the data collection and analysis, we sought dependability and confirmability by ensuring that data collection methods were consistent and audit trails were maintained and transparent – allowing for verification of the research steps alongside using the different artifacts and drawing from the third coauthor for triangulation and member checking.

Findings

In the initial section of the findings, we outline characteristics associated with operational and entrepreneurial leadership - which is evident in the data. However, it is worth noting that these characteristics were less prominent than enabling leadership. As such, we focus on presenting findings related to enabling leadership in detail, elucidating its integration and synthesis with the operational and entrepreneurial functions of CLT.

Sections of conversation are presented as quotations, LM and SH denote the speakers, and images are included where these were triggers for the conversation.

Operational and entrepreneurial leadership

In the early stages of the pandemic, the prevailing leadership function, perhaps unsurprisingly, was operational leadership. At this point, activities were focused on the emergency pivot to online learning, teaching, and working, focusing on students’ progress and support. Leadership activities were dominated by managing day-to-day and week-to-week actions that would meet the immediate and short-term needs of students, staff and program requirements. Three operational characteristics emerged: time and effort of meetings, frequent and unpredictable changes in policy and guidance, and top-down direction. Compared to pre-pandemic working, we noted substantial increases in the time and effort related to online meetings. The move to online meetings necessitated changes in meeting etiquette, increased screen time and less opportunity for informal and opportunistic interactions. The volume of meetings also increased, which included meetings with students and colleagues within each school and across the university and with external colleagues where significant liaison with external examiners, accrediting bodies, regulators, and placement sites was needed. Although such activities might now be viewed as routine for HE academic leads, what set this situation apart was the surge in the volume of these activities and the adaptations required when meeting online. Here, LM noted the increase in operational tasks filling the day, yet, there was a need to think ahead for when the physical campus reopened. This demonstrated the challenge of continuing with the operational tasks whilst considering entrepreneurial approaches to inform and enable the new norm.

LM: I know that one of my strategies is to try to identify what I need to do… preparing an agenda two hours before a meeting. It’s looking at your diary… It means that you don’t miss things, that generally people will not feel that you’re not on the ball and things, but it crowds out your time and doesn’t give you the headspace for that creative, longer-term, innovative thinking that you actually need to do. And I’m finding it really difficult to get that sort of headspace.

In her response, SH noted similar challenges:

SH: That makes sense… I feel the crowding out of the day partly imposed upon me because of deadlines and decision-making. But it’s driven by group meetings because we need to collaborate and be involved… which then takes my … emotional energy and, I suppose parts of my cognitive efforts as well in chairing meetings. And then, going in with the agenda, the updates, the questions … then the action points. Which means it’s a continuous cycle … And then the question is, am I doing the creative or the longer-term visioning - even for the next six months and twelve months? At the moment, I fear it’s suffering because if it’s not happening between seven and nine [in the morning] or seven and ten at night, and for me, that’s not a workable space for thinking, then it starts to happen on a Sunday’.

From the perspectives of our associate dean roles, the ‘top-down’ approaches appeared to be driven by internal and external policy changes and revised or new guidance. These were operationally focused and often transactional, with limited consultation. In the conversations, this perspective was characterized by expressions of feeling passive, being told of change, and decisions made by others, our roles being to implement and interpret.

Entrepreneurial leadership activities emerged through the fast-paced activity to move on-campus teaching online. Creativity and innovation were borne out of necessity, and new approaches to teaching and assessment were developed, in which we facilitated and supported others to develop and implement innovations quickly. Sometimes, such developmental work was being undertaken in an almost invisible way, dwarfed by operational considerations.

Although we have identified operational and entrepreneurial leadership activities, throughout the data, enabling leadership was a function within each of these leadership components due to the overlapping nature of the operational-enabling and entrepreneurial-enabling strands. We now report on the findings for enabling leadership.

Enabling leadership

The prevailing sentiment conveyed by the data suggested that we were navigating a world characterized by enabling leadership during a crisis. The importance of enabling leadership was particularly evident when work was pressured. It advanced new ways of working, notably working from home, which was associated with new or repurposed physical, social, and virtual spaces. Three themes linked to enabling leadership emerged from the data: leader as interface, compassion and empathy in relating to people, and emotion work and self-care.

Leader as an interface

As enabling leaders, we acted as an interface with individuals and teams within our schools, including those involved directly in learning and teaching: module/course leaders, program teams, student advisers, etc. We were also an interface with institutional and external colleagues and teams. When we coded the data with the notion of leader as an interface, this was captured by a set of terms that foreground the relational nature of enabling leadership: relationships, teamwork, team cohesion, networks, connections and communication. While we perceived that we were taking a more command and control approach than would typically feature in our leadership approaches, in fact, the process of coding and reflecting revealed the pervasive presence of working together in partnership with others. What was striking was the extent to which our experiences were broadly similar, and in our conversations, we tended to reinforce and reflect on one another’s experiences.

A leader as an interface emerged as a way to characterize relationships with individuals in our immediate teams. On a personal level, enabling leadership revealed itself as a tension between how we wanted to lead (supportive, collaborative leadership) and what we felt we were doing (directive, operational leadership). In an early conversation, LM comments:

And I’m torn between my desire to really support that person emotionally … But there’s a real, I feel a real tension … They need to be able to put this behind them and get on with the work, which is actually really urgent and a huge piece of work. (LM)

SH then echoes this sentiment:

But it’s another balance between listening, supporting, finding out where they think they are in their contribution and holding back what might be my connected emotion and concern. We have a lot to do before we welcome students back on campus in October.

This exchange captured the complexity of us as leaders, wanting to support individuals yet feeling the pressure to achieve goals. Such sentiments continued to be a feature of many of our conversations, if not the focus. In a later conversation, LM starts the discussion with, ‘I’ve already said to you that quite a lot of that [hard work] is related to people. I think we keep coming back to that’. SH then recognizes the comfort in the familiarity of our close teams, saying, ‘I feel I’m in the middle of it in some ways, moving up and down this helter-skelter, perhaps feeling most comfortable, being with all of my colleagues who are hard at it “doing”, close to the student’s “doing”, supporting them.’ In this context of working through a crisis with a close team of colleagues, the leader as an interface is not just a transactional or task-focused state, but one in which relationships and connections are as important, if not more so, to both leader and those they work with.

Our conversations about working with more senior colleagues in our respective schools or at the institutional level reveal a different perspective of the leader as an interface. In these situations, the discussions shift to being more practically orientated. SH comments, ‘It’s like being inside a fairly large project management system where we’re rolling, we’re rolling with, and we’re rolling out workstreams and activities’. This conversation progressed with less emotive language, and the discussion between us centered on university planning, strategy, and how learning and teaching had become much more of a priority as the pandemic’s impact on students took hold. The conversations take a markedly more practical turn. LM says:

At the moment, the main thing on my mind is the timetabling arrangements, the recommendations about face to face teaching, the different messages that are coming out…

SH’s response continues in this operationally-focused and practical way:

I’m watching the different work streams, the estate, the timetabling, and then the pedagogy, the education piece.

However, while our functional, task-focused roles as an interface for our schools with the wider university come through in the conversations and images (), they are woven through with concern around the pressure and uncertainty that the crisis brought. In an exchange in which laughter from both of us probably conceals genuine concern and stress, LM notes, ‘You hesitate to say anything’s going well in case it all falls apart by this afternoon’, to which SH replies, ‘That’s something like the fragility of the situation?’ The exchange that immediately followed from this was peppered with both using words like ‘anxious’, ‘dislocated’, ‘stressful’, and ‘pressured’ - often multiple times.

Image 2. ‘It’s all so procedural … ’ – an image capturing the task-focused nature of the role (Photograph taken by Howden (Citation2020), published in Howden et al. (Citation2021).

In our discussions of leader as interface within our teams and schools, much of that relation work appeared to link to us trying to support others in their work and feelings. When we considered the interface with the wider university, which for us was mainly working with senior colleagues to implement policy, guidance and directives, the stress and anxiety was ours.

Compassion and empathy in relating to people

Another notable characteristic of enabling leadership was a value related to being available, compassionate, and responsive, supporting the wellbeing of staff and students. This was evident in narratives highlighting compassion and empathy, being open to the uniqueness of individual experiences, being attentive in our role to respond to them as individuals, and being mindful of the context and issues raised. What follows is a conversation after SH had asked LM about the week’s activities and LM having spent time reflecting on a challenging situation that had arisen with a colleague, which left LM feeling quite fatigued.

LM: […] So, I’m pretty drained, if I’m honest.

SH: And how does the COVID context influence this, or does it?

LM: I think it does influence it. […] I think despite how much we’re all used to working together, it would probably be a bit easier if we were all in the room together, and, you know, there’s something around being able to reach out to people when you’re having those emotional or emotive discussions. Sometimes, you want to sit a bit closer to somebody, and sometimes, you just want to touch somebody on the arm. Sometimes, you want to give them a hug. Or sometimes you just want to pass them a tissue because they’re upset, and you can’t do any of that. [in an online meeting]

SH: Every day is starting earlier or interrupting elements over the weekend, and I think that relates to the pace at which decisions need to be made, communications need to happen with groups of people […] I’m trying to get into-and-out-of emotional conversations as well, where people require time and support. So, I’m attempting to do a coaching style conversation where people, one-to-one, and want to spend, need to spend a bit of time at the beginning talking about and describing what’s happening for them, how they’re feeling, and then the main messages they wanted to relay to me. And it feels like, my tension is, that I don’t have enough [space] in the diary […] to do these conversations and trying to stop myself from doing things which are inappropriate. I believe, for example, asking any staff member, ‘Why don’t we touch base at 8 am?’ ‘What about after five?’ is wholly inappropriate in these times of being at home, attempting to work, and to get the best from people who feel supported, cared for and listened to. I don’t see a shortcut to the one-to-one conversation […] It’s another balance between listening, supporting, finding out where they think they are in their contribution and holding back what might be my connected emotion and concern.

Listening to and responding to others is prevalent through the data, whether this was in relation to teams or individuals. It also varied between work concerns and decisions, personal issues and sometimes tensions between these. Although we had experience of managing and supporting others at work, the pandemic was characterized by increased volume and complexity in this area. As the work environment changed in the space it inhabited, other boundaries changed too. We found ourselves responding to others outside normal working hours and in relation to issues and concerns that were not always connected to work. Added to that was the need to be highly sensitive to individual differences to ensure we had meaningful, supportive responses.

The notion of compassionate approaches in our working relationships encompassed the range of people we interacted with. Support for people who we were managing or who were in teams we were leading came through frequently in the conversations. However, there are also regular references to compassion and empathy for senior colleagues, external partners in health and care, and our peers. This is partly engendered in a listening approach.

Emotion work and self-care

Amid the reflections about care and support for others was emotional talk about holding back, as seen in the following conversation. There were accounts of trying not to show, through verbal or non-verbal communication, our own feelings of fear, concern, and uncertainty when in conversations with others, individually or in groups.

LM: so it’s trying not to just be completely subsumed by all the stuff that comes up day to day and have that forward-thinking thing, but then exactly as you’re saying, not actually knowing what the future holds.

SH: … is there a tension or a paradox between aspects of being perceived to be in the leadership role, which is in part about in crafting the vision and the direction amidst uncertainty? … It is fundamentally a complex system, and you can’t, and shouldn’t, I guess, simplify it for people because … they can see that too, but then how do you develop meaningful milestones for people to work to?

LM: It’s true, it is difficult to give, just difficult give people certainty, but equally, and the people we’re working with, they’re intelligent, but you’re right, they are also looking to people like us for direction and for that kind of support, and I suppose it boils down a bit to, you know, on the surface you’re trying to give people that confidence that there are plans, which there are, and that there will be certainty, and there will be support, while internally you’re thinking, ‘Oh my goodness, I am so scared about all of this and so stressed about all of this, I haven’t got a clue what the answers are going to be’, but you can’t convey that to others.

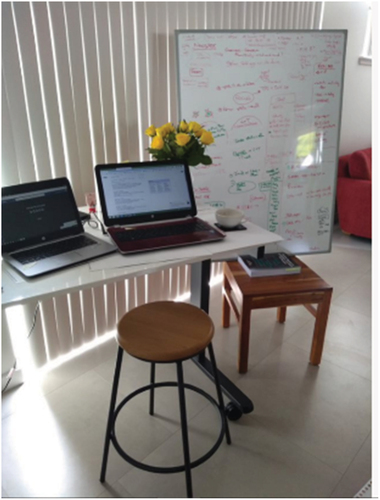

The conversation then moves to the photograph LM had taken that week as a stimulus for the reflection (see ).

Image 3. ‘All boxed up’ – an image capturing aspects of self-care (hand-cream, tissues, disinfectant wipes, and nuts and raisins) (Photograph taken by Martindale (Citation2020), published in Howden et al. (Citation2021).

SH: Yep. How does your box from your photograph and some things in your box, your photo, shows like a whole toolkit of highlighters and laptop and, of course, important disinfectant wipes at this time? How does that connect to the aspects of managing, the elements of your work and your activity?

LM: I think some of it is about actually the relatively small number of things you actually need to carry on your work… so I think the thing about the box for me is something around actually work is, you know, it’s not a building, it’s not an office, your conception of what work is has actually probably fundamentally changed, but it’s also about the balance because there are, I don’t know, you probably can’t see it very well, but there are some nuts and fruit in the box, and there’s like hand cream and stuff, so it’s also about the stuff that actually tries to keep you going through the day as well.

SH: That’s interesting, an interesting point there about, I suppose, aspects of self-care, nutrition, and also, I suppose, organization - it looks organized to me, it says ‘nimble’, it’s mobile…

LM: I quite like having just my box of things, and I know that that’s all I need, and I can actually just get on, and I find it easy to concentrate wherever I have to be sitting.

It seemed that being an enabling leader and experiencing emotional labor often went hand in hand for us in this context. There were instances when the enabling function appeared to be relatively free of feeling strain and emotion, such as in mentions of aiming to ‘distribute the leadership’ (LM) or ‘joint problem-solving’ (SH). However, the combination of personal and professional challenges that most, if not all, staff were facing at this time seemed to provoke us to reflect deeply. This often led to us masking our own emotions when we felt that this would be helpful in a particular context or scenario.

This emotional labor raised questions about how and whether this could be sustained, leading us to consider our own wellbeing. Alongside the discussion of emotion work, there are references to the importance of self-care. This notion of self-care often permeated the visual data that we collected, including and a quote that captured awareness of self-care soon after the start of the pandemic.

Image 4. ‘Hand-in-hand: Self-care and work’ – an image capturing aspects of self-care (flowers, hand cream, and coffee) together with multiple workspaces (Photograph taken by Howden (Citation2020), published in Howden et al. (Citation2021).

This captures my thinking and actions … trying to find order with a whiteboard and making a plan, fueling the day with coffee, interspersed with glances to the flowers to help steady my mind. (SH)

We reflected on strategies used to support self-care, such as having an organized, pleasant workspace and making time to be in nature, exercise, and engage with social (non-work) activities when possible. The data also reflected how we placed value in having the safe space of our recorded discussions and the Teams site to converse with a peer, an additional activity associated with self-care.

Discussion

Although initially unplanned, as a research project during the first pandemic-driven lockdown, which commenced in March 2020 (a second lockdown began in January 2021 ([Scottish Government, Citation2022]), our peer dialogue offered an opportunity to explore HE leadership practice during a time of intense and rapid change. Using the CLT framework to guide the data analysis, we initially focused on identifying themes relating to operational, entrepreneurial and enabling leadership functions. The data aligned well with the characteristics of operational and entrepreneurial leadership.

For many, operational leadership could appear as a typical day in the office, the intensity of this aspect during the COVID-19 pandemic was unprecedented. The demands on operational leaders surged as they had to make quick decisions to maintain organizational continuity and adapt to new and evolving regulations. The pandemic heightened the need for effective communication, online collaboration, and decision-making agility in response to unforeseen challenges. All of which are evident in the data, for example, where SH noted the increase of operational tasks ‘crowded out the day’ where the heightened frequency and intensity of meetings and the swift implementation of policy changes left little room for strategic thinking and planning. This, in turn, posed challenges for integrating entrepreneurial leadership into the process of envisioning and preparing for the emerging normalcy.

As the analysis progressed, it became evident that enabling leadership aligned with the Uhl-Bien and Arena (Citation2017) framework. Our first theme of (i) Leaders as Interface demonstrated this alignment by portraying leaders as the connectors between operational and entrepreneurial leadership through networking and collaborative working efforts (Beresford-Dey et al., Citation2022). Enabling leadership was the area in which the findings were more complex and nuanced, resulting in two further themes – (ii) Compassion and Empathy in Relating to People and (iii) Emotion Work and Self-care.

Hence, in addition to the prior-understood aspects of enabling leadership captured by CLT (Uhl-Bien & Arena, Citation2017), we found a quality of enabling: compassionate leadership, in which emotional labor was integral. Similarly, Tourish (Citation2019) raised doubts about the comprehensiveness of CLT, suggesting that the relational interactions remain largely unexplained; our findings offer a starting point to address this critique.

Compassion is an evolutionary concept that has entered the leadership lexicon. Whilst compassion is not a recent development, the explicit combination of ‘compassion’ and ‘leadership’ in scholarly discourse is a relatively recent phenomenon. In their literature review on compassionate leadership, Ramachandran et al. (Citation2023) observed a limited number of articles published in the 1990s. Subsequently, they also reported that while there has been consistent growth in overall publications on compassionate leadership, the quantity of studies remains low. Compassion can be defined as an emotional experience that an individual has when recognizing and wanting to alleviate the suffering or perceived unmet needs of others (Goetz & Simon-Thomas, Citation2017; Ramachandran et al., Citation2023; Waddington, Citation2018). In terms of leadership, the Center for Compassionate Leadership (Citation2019) identifies compassionate leaders as being ‘on the leading edge of a new age of connection, creativity, and cooperation by acting with kindness, empathy, compassion and concern for others’ (no page). Several components are noted within these definitions, including (1) an awareness of another’s needs, experiences, and suffering, (2) being/feeling moved (3) acting in response to alleviate the suffering. Each of these features are evident at various points within our data - for example, where LM reflected on supporting a ‘person emotionally’ and at other times needing to ‘pass them a tissue’ or ‘give them a hug’, and SH needing to ‘care, listen, and support’ without encroaching on an individual’s personal time.

de Zulueta (Citation2021) extends the understanding of compassion by considering an ‘inward’ flow (self-compassion) alongside the needs of others. Similarly, Nardick (Citation2013) and West (Citation2021) point out the importance of self-compassion alongside showing compassion for others is crucial for successful leadership, with West (Citation2021) highlighting that self-compassion is at the ‘heart of our leadership and working relationships’ (p. 219). From this, it can be proposed that to be compassionate academic leaders in higher education, we need to take time to truly understand and respect the needs of others and ourselves through trusting and supportive relationships alongside maintaining opportunities for reflection – a practice that was found valuable to SH and LM (Howden et al., Citation2021). Alongside the reflective dialogue, our data indicates a practice of self-care, as evidenced by the presence of items such as flowers, strategically placed to support mental wellbeing. Additionally nuts and fruit, paired with disinfectant wipes and hand-cream were observed, reflecting the need to take care of our physical wellbeing.

Higher education educators and leaders encounter various wellbeing challenges (Jayman et al., Citation2022; Kinman, Citation2014), including relentless workload and time pressures, which disrupt the work-life balance, potentially leading to stress and burnout. Additionally, they face emotional demands arising from the intensity of their work, dealing with student and staff issues, interpersonal dynamics, a sense of isolation, poor management, and job insecurity, amongst others (Kolomitro et al., Citation2020; O’Brien & Guiney, Citation2018; Wray & Kinman, Citation2021). The onset of the global pandemic further exacerbated these challenges (Jayman et al., Citation2022; Wray & Kinman, Citation2021), triggering ‘pressures and anxieties’ (Creely et al., Citation2022, p. 1241) as universities pivoted to online learning, necessitating additional investment in staff development, lesson preparation, and efforts to maintain student engagement (Henriksen et al., Citation2020).

While support mechanisms are typically available within institutions, such as peer support networks, counseling, professional development opportunities and flexible working arrangements (Kinman, Citation2014; Savage, Citation2022; Wray & Kinman, Citation2021). Unfortunately, some academics lack access to resources and services or lack knowledge of the resources (Wray & Kinman, Citation2021). Moreover, the stigma surrounding mental health issues in academia may discourage individuals from seeking help or disclosing their struggles, further undermining their wellbeing (Jayman et al., Citation2022). Consequently, this may impact their capacity for compassion.

Pharoah (Citation2018) questions why so many find compassion difficult within the working environment; they suggest this may be due to the organizational culture where there is potentially a perception of weakness surrounding compassionate behaviors leading to a lack of importance on compassionate practices. More specifically, according to Caddell and Wilder (Citation2018), compassion in HEIs is challenging to find, and this is aligned with the competitive nature of the environment. Examples of this competition include marketization such as league tables, national student surveys, and striving for ‘excellence’ alongside increasingly limited resources, amongst others. Against the backdrop of ‘policies, promotion criteria that privilege individual success, and measurement’, they question the affordance of compassion (p. 20). Yet the data suggests compassion is valued, but similar to Pharoah (Citation2018), Caddell and Wilder recognized that institutional culture could harm staff interactions. Thus, there is a need to reframe the cultural narrative and practices through a compassionate lens.

Within our data surrounding compassionate leadership, we identified experiences of emotional labor. For example, suppressing the communication of specific emotions (i.e. fear, anxiety) with others where LM reflects on the need to show confidence and not transmit her internal thoughts of ‘Oh my goodness, I am so scared about all of this and so stressed about all of this, I haven’t got a clue what the answers are going to be’. Pioneered by Hochschild (Citation1983), emotional labor is considered as managing one’s own emotions, the ‘coordination of mind and feeling’ (p. 7), or the ‘bracketing’ of emotions (Heffernan & Bosetti, Citation2020, p. 357) to maintain objectivity and show regulated emotions rather than one’s natural emotions within a given situation. Although the concept and acts of emotional labor are reported in HE in non-crisis times, the pandemic triggered a widespread surge in emotional labor among HE staff (Skallerup Bessette & McGowan, Citation2020). This increase seems to have been notably pronounced for HE leaders who are closely engaged with students and academic staff (Heffernan & Bosetti, Citation2020; Skallerup Bessette & McGowan, Citation2020).

As we emerged from the initial wave of the pandemic, questions arose about how to continue to adapt through enabling leadership, and to build sustainable resilience in HE (Parkin, Citation2020) throughout times of uncertainty. In the context of analysis using CLT, we propose supplementing enabling leadership by considering the need for compassionate leadership practices. The social and emotional connectedness appeared substantive in working with others in sustained and productive ways. We propose that an ethic of care and compassion should be considered an integral element of enabling leadership practices for HE leaders () to create an environment where individuals can flourish throughout periods of change and beyond. When considering practices aligned with engendering social and emotional connectedness, we argue that leaders should create time and space for reflecting on the benefits of compassionate leadership, the risks of sustained emotional labor, and the place of self-care and how that can be supported.

Limitations

This study is not without limitations. First, our data were generated by two of us with responsibilities focused on learning and teaching, and our biographies will have influenced ways of thinking and approaches to practice. We were also from one institution, and given that leadership is contextual (Lakomski & Evers, Citation2022) and influenced by the institution and wider society, this may limit the findings’ transferability. However, the aim was to share insights to CLT when used as a lens to make sense of leadership in HE. Second, it could be argued that the setting of the early stages of the pandemic did not relate well to ‘business as usual’ periods in an HEI. We recognize the extraordinary and traumatic impact of the pandemic, which has ongoing effects. Yet, we are also mindful that some of these challenges prevail in HE. For example, concerns for staff and student wellbeing, managing the pace of technological advancement, and uncertainty are recognizable components of ‘business as usual’ within HE. Finally, there are limitations surrounding duoethnography, as noted previously. We are cognizant of the risk of only seeing or having attention drawn to features of our narratives that concur or align with CLT. However, the use of open coding of text and images, beyond the CLT functions of leadership, resulted in identifying elements such as those related to compassionate leadership.

Implications

To make sense of and adapt to rapidly ever-changing environments, Turner and Baker (Citation2019) report on the need for leaders to think and act with complexity in mind. Our study adopts CLT and seeks to illustrate its potential as a framework for researchers and practitioners to view the three leadership functions as a tool for critical thinking, collaboration, exercising creativity, planning, and strategizing in complex organizations such as HEIs. To augment the effectiveness of CLT, our findings bring to light a discovery emphasizing the role of compassionate leadership. This encompasses aspects such as compassion and empathy toward others, self-awareness, self-care, and the inclusion of emotional labor – all contributing to the practice of enabling leadership. Future research might utilize our evolved framework beyond a global pandemic through longitudinal case studies to further develop our understanding of the role of compassionate leadership. However, this relational feature is a circumstantial phenomenon which brings a level of complexity, and in the same way, any attempts to simplify complexity leadership should be avoided.

In relation to practice and as we navigate beyond the pandemic, the pressing need to persistently adapt through enabling leadership and cultivating sustainable resilience in Higher Education remains. We recommend that current and future leaders understand and cultivate compassionate and empathetic practices within this dynamic and uncertain context. We advocate for including an ethic of care and compassion for the self and others as fundamental elements of enabling leadership practices through holding conversations, actively listening to individuals’ needs and reflecting deeply to engage in a thoughtful and introspective process and provide support during challenging times.

Turning to policy, a compassionate approach means crafting regulations, guidelines, and frameworks that consider the human element. We recommend that compassionate policymaking involves understanding the diverse needs and circumstances of those affected where policies are not only designed to meet organizational or societal goals, but also to consider the impact on individuals and teams, particularly during times of rapid change.

Conclusion

COVID-19 brought unimaginable challenges for academic leaders in higher education (HE) as they responded to complex change at a time of stress and disruption at system and individual levels. There have been examples of effective change, innovation and leadership that have been counterproductive (Uhl-Bien, Citation2021). This research study aimed to explore the usefulness of CLT for academic leadership in HE. Addressing our research question, ‘How do academic leaders in higher education understand leadership during a crisis?’, the context (of the pandemic) provided a unique scenario that illuminated leadership realities at one HEI over a nine-month period (Howden et al., Citation2021; Beresford-Dey et al., Citation2022). While we found the CLT framework to be a valuable tool, what emerged from our findings was the substantial focus on self-care, emotional labor, and care for others. This highlights the quality of interactions and relationships associated with compassionate leadership that can enhance the enabling leadership function to support operational and entrepreneurial activities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marie Beresford-Dey

Marie Beresford-Dey is a Senior Lecturer of Educational Leadership in the Division of Education and Society, School of Humanities, Social Sciences and Law at the University of Dundee. Marie has worked at the University for ten years. She teaches Educational Leadership across various postgraduate programs. Her research interests include educational leadership, complexity leadership theory, environmental sustainability and climate change.

Stella Howden

Stella Howden is an Associate Professor (Learning and Teaching Enhancement) at Heriot-Watt University. Prior to joining Heriot-Watt University, she was Associate Dean (Learning and Teaching), School of Medicine, University of Dundee. She is a Senior Fellow (Advance HE) and is passionate about enabling inclusive and equitable learning/development opportunities in Higher Education (HE) for students and staff. Her scholarship and research interests include curriculum and evaluation, quality enhancement in HE and leadership. She is co-editor of The International Journal of Practice Based Learning in Health and Social Care.

Linda Martindale

Linda Martindale is Professor of Higher Education and Academic Practice, and Dean of the School of Health Sciences, University of Dundee. Linda has worked at the University of Dundee for over 20 years and was previously Associate Dean Learning and Teaching. She has wide experience in online/distance education, as well as expertise in curriculum development, particularly for professional programs. Linda’s research and scholarship interests are in the areas of thresholds concepts, academic leadership, expert teaching in HE and more recently education for sustainable development.

Notes

1. Associate deans are academic members of staff reporting to the Dean of a school, faculty or college within a higher education institution, and part of that unit’s senior leadership team.

References

- Adobor, H., Darbi, W. P. K., & Damoah, O. B. O. (2021). Strategy in the era of “swans”: The role of strategic leadership under uncertainty and unpredictability. Journal of Strategy and Management, ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/JSMA-09-2020-0242

- Beresford-Dey, M., Howden, S., & Martindale, L. (2022). Leading in a complex world: Enabling leadership practices to support innovation, change and resilience. BERA Blog. Retrieved May 29, 2024, from https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog/leading-in-a-complex-world-enabling-leadership-practices-to-support-innovation-change-and-resilience

- Beresford-Dey, M., Ingram, R., & Lakin, L. (2024). Going beyond creativity: Primary headteachers as social intrapreneurs? Educational Management Administration & Leadership. https://doi.org/10.1177/17411432231223628

- Boylan, M. (2016). Enabling adaptive system leadership: Teachers leading professional development. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143216628531

- Bradbury-Jones, C. (2007). Enhancing rigour in qualitative health research: Exploring subjectivity through Peshkin’s I’s. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 59(3), 290–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04306.x

- Breault, R. A. (2016). Emerging issues in duoethnography. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 29(6), 777–794. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2016.1162866

- Burleigh, D., & Burm, S. (2022). Doing duoethnography: Addressing essential methodological questions. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 21, 16094069221140876. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069221140876

- Caddell, M., & Wilder, K. (2018). Seeking compassion in the measured university: Generosity, collegiality and competition in academic practice. Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice, 6(3), 14–23. https://doi.org/10.14297/jpaap.v6i3.384

- Callahan, J. (1994). Defining crisis and emergency. The Crisis, 15(4), 164–171.

- Carvalho, A., Leitão, J., & Alves, H. (2022). Leadership styles and HEI performance: Relationship and moderating factors. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2022.2068188

- Center for Compassionate Leadership. (2019). What is compassionate leadership? Retrieved March 31, 2023, from https://www.centerforcompassionateleadership.org/blog/what-is-compassionate-leadership

- Cilliers, P. (2000). Knowledge, complexity, and understanding. Emergence: Complexity & Organization, 2(4), 7–13. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327000EM0204_03

- Creely, E., Laletas, S., Fernandes, V., Subban, P., & Southcott, J. (2022). University teachers’ well-being during a pandemic: The experiences of five academics. Research Papers in Education, 37(6), 1241–1262. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2021.1941214

- de Zulueta, P. (2021). How do we sustain compassionate healthcare? Compassionate leadership in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinics in Integrated Care, 8, 100071. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intcar.2021.100071

- Dumulescu, D., & Muţiu, A. I. (2021). Academic leadership in the time of COVID-19—Experiences and perspectives [Original research]. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.648344

- Gaus, N., Basri, M., Thamrin, H., & Ritonga, U. (2022). Understanding the nature and practice of leadership in higher education: A phenomenological approach. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 25(5), 685–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2020.1737241

- Gigliotti, R. A. (2019). Crisis leadership in higher education: Theory and practice. Rutgers University Press. https://libezproxy.dundee.ac.uk/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=2275650&authtype=shib&site=ehost-live&scope=site

- Goetz, J. L., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2017). The landscape of compassion: Definitions and scientific approaches. In E. M. Seppala, E. Simon-Thomas, S. L. Brown, M. C. Worline, C. D. Cameron, & J. R. Doty (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of compassion science (pp. 3–16). Oxford University Press.

- Gordon, L., & Cleland, J. A. (2021). Change is never easy: How management theories can help operationalise change in medical education. Medical Education, 55(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14297

- Grajfoner, D., Rojon, C., & Eshraghian, F. (2022). Academic leaders: In-role perceptions and developmental approaches. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 174114322210959. https://doi.org/10.1177/17411432221095957

- Grant, J. (2021). The new power university: The social purpose of higher education in the 21st century. Pearson.

- Gravatt, J. (2023). Are universities really at risk of ending up in the public sector? Retrieved December 6, 2023, from https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2023/03/21/are-universities-really-at-risk-of-ending-up-in-the-public-sector/

- Hager, P., & Beckett, D. (2022). Refurbishing learning via complexity theory: Introduction. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 56(5), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2022.2105696

- Hanson, W. R., & Ford, R. (2010). Complexity leadership in healthcare: Leader network awareness. Procedia – Social & Behavioral Sciences, 2(4), 6587–6596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.04.069

- Heffernan, T. A., & Bosetti, L. (2020). The emotional labour and toll of managerial academia on higher education leaders. Journal of Educational Administration and History, 52(4), 357–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2020.1725741

- Henriksen, D., Creely, E., & Henderson, M. (2020). Folk pedagogies for teacher transitions: Approaches to synchronous online learning in the wake of COVID-19. Journal of Technology & Teacher Education, 28(2), 201–209.

- Hochschild, A. (1983). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling. University of California Press.

- Howden, S., Beresford-Dey, M., & Martindale, L. (2021). Critical reflections on academic leadership during Covid-19: Using Complexity Leadership Theory to understand the transition to remote and blended learning. Journal of Perspectives in Applied Academic Practice. https://doi.org/10.14297/jpaap.v9i2.478

- Jayman, M., Glazzard, J., & Rose, A. (2022). Tipping point: The staff wellbeing crisis in higher education. Policy and Practice Reviews, 7, 7. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.929335

- Kinman, G. (2014). Doing more with less? Work and wellbeing in academics. Somatechnics, 4(2), 219–235. https://doi.org/10.3366/soma.2014.0129

- Kolomitro, K., Kenny, N. A., & Sheffield, S. L.-M. (2020). A call to action: Exploring and responding to educational developers’ workplace burnout and well-being in higher education. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(1), 18–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2019.1705303

- Kucharska, W., & Rebelo, T. (2022). Transformational leadership for researcher’s innovativeness in the context of tacit knowledge and change adaptability. International Journal of Leadership in Education, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2022.2068189

- Lakomski, G., & Evers, C. W. (2022). The importance of context for leadership in education. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 50(2), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/17411432211051850

- LeBlanc, P. J. (2018). Higher education in a VUCA world. Change, the Magazine of Higher Learning, 50(3–4), 23–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2018.1507370

- Leitch, C. M., & Volery, T. (2017). Entrepreneurial leadership: Insights and directions. International Small Business Journal, 35(2), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242616681397

- Leithwood, K. (2019). Characteristics of effective leadership networks: A replication and extension. School Leadership & Management, 39(2), 175–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2018.1470503

- Lemoine, P. A., Hackett, T., & Richardson, M. D. (2017). Global higher education and VUCA – Volatility, uncertainty, complexity, ambiguity. In S. Mukerji & P. Tripathi (Eds.), Handbook of research on administration, policy, and leadership in higher education (pp. 549–568). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-0672-0.ch022

- Macken, C., Hare, J., & Souter, K. (2021). Higher education in the time of disruption. In C. Macken, J. Hare, & K. Souter (Eds.), Seven radical ideas for the future of higher education: An Australian perspective (pp. 1–13). Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-16-4428-3_1

- Malikhah, I. (2021). An effect of planning, organizing, staffing, leading and controlling of operational leadership. Budapest International Research and Critics Institute, 4(3), 4643–4652.

- Marion, R. (2008). Complexity theory for organizations and organizational leadership. In M. Uhl-Bien & R. Marion (Eds.), Complexity leadership: Part 1: Conceptual foundations (Vol. 1, pp. 1–16). Information Age Publishing.

- Morrison, K. (2002). School leadership and complexity theory. Routledge Falmer.

- Mowles, C., Filosof, J., Andrews, R., Flinn, K., James, D., Mason, P., & Culkin, N. (2019). Transformational change in the higher education sector. Advanced HE. Retrieved November 14, 2023, from https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/transformational-change-higher-education-sector

- Nardick, D. L. (2013). How to become a reflective and compassionate leader. The Department Chair, 24(1), 18–19. http://president.central.edu.s3.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Department-Chair-book-review-electronic-copy.pdf

- Norris, J., & Sawyer, R. D. (2012). Toward a dialogic methodology. In D. Lund, R. D. Sawyer, & J. Norris (Eds.), Duoethnography: Dialogic methods for social, health, and educational research (pp. 9–39). Left Coast Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315430058

- O’Brien, T., & Guiney, D. (2018). Staff wellbeing in higher education. Education Support Partnership. https://healthyuniversities.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/staff_wellbeing_he_research.pdf

- Office of National Statistics. (2023). Classification review of universities in the UK. Retrieved December 6, 2023 from https://www.ons.gov.uk/news/statementsandletters/classificationreviewofuniversitiesintheuk

- Parkin, D. (2020). Developing sustainable resilience in higher education. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/developing-sustainable-resilience-higher-education

- Parpala, A., & Niinistö-Sivuranta, S. (2022). Leading teaching during a pandemic in higher education—A case study in a Finnish university. Education Sciences, 12(3), 147. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12030147

- Pharoah, N. (2018). The new world of compassionate leadership. Training Journal, 20–22. https://www.trainingjournal.com/2018/business-and-industry/magazine-excerpt-new-world-compassionate-leadership/

- Quinlan, K. M. (2014). Leadership of teaching for student learning in higher education: What is needed? Higher Education Research & Development, 33(1), 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.864609

- Ramachandran, S., Balasubramanian, S., James, W. F., & Al Masaeid, T. (2023). Whither compassionate leadership? A systematic review. Management Review Quarterly, Advance online publication, 1–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-023-00340-w

- Regine, B., & Lewin, R. (2002). Leading at the edge: How leaders influence complex systems. Emergence, 2(2), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327000EM0202_02

- Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Sage Publications.

- Ritchie, J., & Spencer, L. (1994). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In A. Bryman & R. Burgess (Eds.), Analysing qualitative data (pp. 173–194). Routledge.

- Sánchez-Barrioluengo, M., Uyarra, E., & Kitagawa, F. (2019). Understanding the evolution of the entrepreneurial university. The case of English Higher Education institutions. Higher Education Quarterly, 73(4), 469–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/hequ.12230

- Sarkar, A. (2016). We live in a VUCA world: The importance of responsible leadership. Development & Learning in Organizations: An International Journal, 30(3), 9–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/DLO-07-2015-0062

- Savage, K. (2022). Peer networks: Fostering a sense of belonging. AdvanceHE. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/news-and-views/peer-networks-fostering-sense-belonging

- Savin-Baden, M., & Howell-Major, C. (2013). Qualitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice. Routledge.

- Schmidt, S. W., English, L. M., & Carr-Chellman, A. (2022). Conversations with leaders: Sharing perspectives on the impact of and response to COVID-19 and other crises. New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education, 2022(173–174), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.20451

- Schön, D. A. (1983). Educating the reflective practitioner. Basic Books, Perseus Books Group.

- Schophuizen, M., Kelly, A., Utama, C., Specht, M., & Kalz, M. (2022). Enabling educational innovation through complexity leadership? Perspectives from four Dutch universities. Tertiary Education and Management, 29(4), 471–490. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11233-022-09105-8

- Schulze, J. H., & Pinkow, F. (2020). Leadership for organisational adaptability: How enabling leaders create adaptive space. Administrative Sciences, 10(3), 37. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci10030037

- Scottish Government. (2022). COVID-19 in Scotland. Retrieved November 23, 2023, from https://data.gov.scot/coronavirus-covid-19/

- Sempiga, O., & Van Liedekerke, L. (2023). Investing in sustainable development goals: Opportunities for private and public institutions to solve wicked problems that characterize a VUCA world.

- Siemans, G., Dawson, S., & Eshleman, L. (2018). Complexity: A leader’s framework for understanding and managing change in higher education. Educause Review, 53(22 November 2023), 27–42. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2018/10/complexity-a-leaders-framework-for-understanding-and-managing-change-in-higher-education

- Skallerup Bessette, L., & McGowan, S. (2020). Affective labor and faculty development: COVID-19 and dealing with the emotional fallout. Journal on Centers for Teaching and Learning, 12, 136–148. https://openjournal.lib.miamioh.edu/index.php/jctl/article/view/212/116

- Stacey, R. D. (1996). Complexity & creativity. Berrett-Koehler.

- Streubert, H. J., & Carpenter, D. R. (2011). Qualitative research in nursing: Advancing the humanistic imperative (5th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Suresh, T. (2015). Connecting universities: Future models of higher education. The Economist Intelligence Unit and British Council. https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/new_university_models_jan2015_print.pdf

- Taskan, B., Junça-Silva, A., & Caetano, A. (2022). Clarifying the conceptual map of VUCA: A systematic review. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 30(7), 196–217. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-02-2022-3136

- Tourish, D. (2019). Is complexity leadership theory complex enough? A critical appraisal, some modifications and suggestions for further research. Organization Studies, 40(2), 219–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618789207