Abstract

‘On November 8, the most powerful country in world history, which will set its stamp on what comes next, had an election. The outcome placed total control of the government -- executive, Congress, the Supreme Court -- in the hands of the Republican Party, which has become the most dangerous organization in world history.’

‘Apart from the last phrase, all of this is uncontroversial. The last phrase may seem outlandish, even outrageous. But is it? The facts suggest otherwise. The Party is dedicated to racing as rapidly as possible to destruction of organized human life. There is no historical precedent for such a stand’ (Noam Chomsky, Monday, 14 November 2016)Footnote1

‘[W]e need to think about those two

things together—the rural and the urban—

and we need to think about the ways in

which people do this extraordinary job,.

whether in the countryside or in the vast

informal areas of cities, of making a living,

of sustaining themselves, of getting by to an

extraordinary extent.’ (Timothy Mitchell)Footnote2

‘Donald Trump just spoke in New York City, giving what was—aside from his customary ad libs and an extended section, resembling a wedding speech, that involved thanking and complimenting supporters such as Chris Christie, Ben Carson, and Republican National Committee Chairman Reince Priebus—a fairly standard president-elect address about unity.’ (Trump: “It Is Time for Us to Come Together as One United People”, Ben Mathis-Lilley, The Slatest, 9 November 2016)

What, where, when are we to define and ground some commitments and actions that are central to humanity’s future (and to that of life on the planet)? Trump, in his ‘victory’ speech after the November election, saw some commitments and action emerging in a ‘Time for Us to Come Together’ in unity. Professor Mitchell, more than a year earlier, saw the need for us ‘to think two things together – the rural and the urban’ and about the ways in which ‘people do this extraordinary job, whether in the countryside or in the vast informal areas of cities, of making a living…’. Chomsky saw the fate of humanity as now ‘in the hands of the Republican Party, which has become the most dangerous organization in world history’.

There are, of course, other views, including some recently established academic ones, with a take on what is going on across the planet. What hope do they hold? Not much, it would seem, if one were to judge by the writings of ‘planetary urbanist’ orthodoxies for whom Mitchell’s two ‘things’ seem hardly to exist. What they seem to see are two non-entities: in the form of a non-city condition, one without an outside. Those that might have been effectively opposed to the victors seem, then, to have cut the ground from under their (and our?) feet.

Timothy Mitchell, Professor of Middle Eastern, South Asian and African Studies at Columbia University, thinks differently. Perhaps such a difference is in part a result of the geo-cultural spread of his ‘subject areas’? But is it also a result of his ‘thinking against the concept’ of these two things and bringing them together, across geo-cultural spaces, and grounding them?Footnote3 Not only has he been thinking but he has come to what is at least an interim stand.

A situation of extraordinary continuing turmoil can be seen as characteristic of the now concluded but hardly politically and socially concluded US Election and, almost as evident, as still there behind the apparent new normality of the fundamentally troubled Europe of Brexit and of ‘Invasive’ refugees. Or rather still seen as marginal in terms of diagnosis and appropriate action?

Our approach in recent work is moving towards considering these two events (taking the Brexit-refugee interaction as also one set of events – see Dimitris DalakoglouFootnote4) as just one. What happens when, as in a series of recent editorials, one applies an apparently only tangential subject of investigation to a mainly inadvertent, unintended collection of articles? Can such an experimental approach contribute, for example, to the development of a political/ideological/groundedFootnote5 dimension, actual and potential, necessary for deep-seated transitionFootnote6 rather than tokenistic or regime ‘change’?

What time, what places, what situations are to be taken as a high priority, as ‘central’ to, but in need of grounding, such investigations, and interventions? Where, what, how (who/whom), when, why is ‘the centre’ or, with a more diverse and (necessarily) evaluative approach, are ‘the key centres’ to be comprehended so as to contribute to our understanding and effective action? Are they essentially and increasingly ‘urban’ –that non-city condition without an outside - as some suppose? How, alternatively, it might be asked, if citynessFootnote7 (or some kind of thought-together rurality and urbanity) is still a legitimate and realisable ambition and condition, do people do ‘this extraordinary job’ of making a living, sustaining themselves, getting by ‘to an extraordinary extent’? To expand and refine these questions, what are the meanings (see the titles of the two US papers listed under ‘close-ups’ below) involved in ‘getting by’ and, extending further, in getting on?

These particular emphases inform what might be termed a philosophical and material reading of a wide range of situations, geographic and historical. As the interview in the paper makes clear this is in one sense a think-piece. However, Mitchell’s readings here are based particularly on readings of ‘Middle-Eastern’ and other experience - as his academic title at Columbia University suggests - and he ranges far beyond them. He and authors Abourahme and Jabary-Salamanca are moving ‘against the concepts’ and towards what one might call some kind of sensuous empiricism.

In our ordering of the papers assembled here and the supplementary material included, we refer to five themes and areas of investigations:

Garbage City to Skyscrapers

Trump Triumphantes?

Close-Ups (Norway, Ireland and Spain; New York and Oakland, USA)

Vanities and IconiCities. New York and London)

Garbage and Urbanity/Rurality: Marx Revisited

1. Garbage City to Skyscrapers: ‘against the sovereignty of concepts’

‘Thinking against the sovereignty of the concept’, clearly is a conceptually-related think-piece but Mitchell's approach and that of the authors is sensuosly empirical, closer to the being-ness, potential or already actualised, of objects (almost their subjectivity) rather than to the measured inertness of the objects, concepts and their sovereignty in ‘normal’ social science. The attempt to get beyond that inertness and fixity is hinted at here (inviting the reader’s attention) by the practice, frequent in this journal of deploying the lead photograph in each issue un-captioned and ‘bled’ from margin to margin. In this issue it is the lead photo from the ‘against the sovereignty … ’ article. In its originating text there is a caption that reads: ‘Garbage City. The enduring challenge of self-organized forms of life … , 2010. Garbage City, Cairo … ’ It is to this tension between a generalised symbolic ‘garbage city’ and a particularised ‘Garbage City, Cairo’, that we shall return.

Manhattan’s architects, dressed as their own skyscrapers, perform ‘The Skyline of New York’ at the City’s Beaux Arts Ball in 1931. From left: (half covered) A. Stewart Walker as the Fuller Building, Leonard Schultze as the new Waldorf-Astoria, Ely Jacques Kahn as the Squibb Building, William Van Alen as the Chrysler Building, Ralph Walker as One Wall Street, D. E. Ward as the Metropolitan Tower and Joseph H. Freedlander as the Museum of the City of New York.Footnote8 Public domain (p. 759).

The overall global reach of this issue includes the Middle-East but also, extends, particularly to New York and London in Stephen Graham’s ‘Vanity and violence: On the politics of Skyscrapers’ where he turns from the apparently ‘humanised’ skyline’ of an earlier New York to, eventually (see section four) today's icon-blocked City of London.

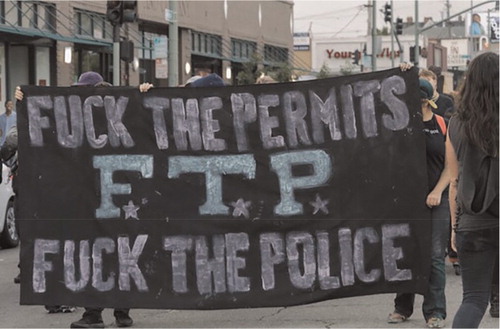

2. Trump triumphantes?

‘Trump … A playing card of a suit ranking above the other three for the duration of a deal or game … ’

‘Trumpery … Of little or no value: trifling, rubbishy, showy but worthless; superficial, delusive.’ (B. Aldiss: ‘The houses … had been given over to trumpery schools of English.Footnote9)

‘Trump…Now especially, beat, surpass, gain an unexpected advantage over (L. H. Tribe: ‘a state's interest in the fetus completely trumps a woman’s liberty’)’

We are not of course, responsible for the names (and their associations) we have inherited. But we are responsible for the words and reasoning that we use. So we must justifiably return, critically, to Trump's victory speech:

‘Ours was not a campaign but rather an incredible and great movement. … It's a movement comprised of Americans from all races, religions backgrounds, and beliefs who want and expect our government to serve our people, and serve the people it will … We are going to fix our inner cities and rebuild our highways, bridges, tunnels, airports, schools, hospitals. We're going to rebuild our infrastructure. Which will become, by the way, second to none. And we will put millions of our people to work as we rebuild it.’ (Trump, ibid)

Trump’s victory speech is revealing. Credible? Was not intense scorn emitted towards Americans from all races, religions, backgrounds, and beliefs, then (apparently) supposed to be legitimised by somewhat tardy outpourings of ‘love’, not so much sycophantic as just plain sick? There were approved lists of conventional urbanistic objects and objectives - inner cities, highways, bridges, tunnels, airports, schools, hospitals, infrastructure - but now magically staged in a transformation scene, a trompe-l'œil (‘an art technique that uses realistic imagery to create the optical illusion that the depicted objects exist in three dimensions.’Footnote10).

Put in the context of Trump’s developing ‘transition’ or rather, perhaps, regime change, The Washington Times’ conclusion on December 1st was: ‘In less than two months, Trump will be the president of the United States. And with Romney’s move, Trump has officially and almost completely cowed the elements of the Republican Party that had shunned the real estate tycoon and reality-television star during the turbulent campaign’.Footnote11 However, only a week later, the Trumpian wheel moved on with the nomination of ExxonMobil chief executive Rex Tillerson.

Overall, then, we proceed, progressing/regressing, according to one’s particular imperial or liberatory take. In Trumpian logic, as can be seen from the passage above, intention is presented as though it has already become action, and action as though it has already been achieved. If so, how? And when? If not, why not?

3. Close-Ups: From Frontiers and Bad Banks to Gentrification and ‘Occupation’

It is time to look at problems in their non-magical state, perhaps threatening to some elites, but not to local people on the ground (also noting the analytic inspiration provided by committed scholars, notably here Neil Smith and Bourdieu), taking up the other four papers and some of their more graphic images, to remind ourselves of the crucial dimension of a struggle for cultural and ethical meaning ignored now and/or probably later to be marginalised, distorted and/or perhaps sometimes to be fêted by Trump’s ‘transitional’ team.

We take in aspects of the European scene - Gothenburg’s urban frontier, the role played by Asset Management Companies (‘bad banks’) in Spain and Ireland (including reference to the USA) - returning to the USA exclusively, in search of meanings, to gentrification in Oakland, California, and to ‘Occupy New York’, but now to be seen in the light or against the darkness of the new regime of President-Elect Trump.

In the European scene (as the Trumpian bug is not confined to the USA but has been simmering elsewhere waiting only for a suitably melodramatic show from the ultra-capitalist homeland), our contributors point to the role played by Asset Management Companies (‘bad banks’) in Spain and Ireland (including reference to the USA), as indicated by Michael Byrne, and with Catharina Thorn and Helena Hodgersson from Gothenburg’s urban frontier (analysis inspired by the work of Neil Smith), turning to the USA exclusively, in search of meanings, to gentrification in Oakland, California, and to ‘Occupy New York’.

‘Displacement’—graffiti in the Gustaf Dalén area during the phase of demolition on Gothenburg’s urban frontier (Photograph: Katarina Despotovic) (p. 666).

The concluding papers return to the USA, both papers taking up questions of meaning, Wall Street by Nils Kumkar (inspired by Bourdieu) and (see below), in an account of resistance to gentrification in Oakland, California, ‘“Gentrification” as a grid of meaning’ by Alex Werth and Eli Marienthal. All four reports now to be seen in the light or against the darkness of the new regime of President-elect Trump.

4. Vanities and IconoCities

We take up further aspects of Stephen Graham’s reference to ‘vanity and violence’ and Mitchell’s discussion of the differing impacts after Egypt’s 2011-2013 revolution on the cities and countryside and moving on (section 5) to an updated account of late-later-latest (so to speak) Marx.

What we seem to need a few months after the US Election is not, of course, just ‘against the sovereignty of the concept’, but also against the ill-founded dreams/proclamations of would-be Emperor Trump and of some key aspects of the troubled and apparent normalities of the world re-discovered and challenged by millennials and others of late, but not necessarily too late…

Stephen Graham notes of London that ‘there are important links between the hypermobility of the world’s corporate and super-rich elites and the often craven efforts to brand new skyscrapers as easily identifiable everyday objects. Here, London’s new range of skyscrapers—nicknamed the ‘Gherkin’, the ‘Shard’, the ‘Cheesegrater’, the ‘Walkie Talkie’ and so on—offer especially powerful examples’.

He continues drawing on Maria Kaika’s work:

Turning to the countryside and Garbage City, Mitchell chooses Egypt in 2011-2013 as the starting point for his conclusion. He argues ‘I think there was this profound sense after the revolutionary period in Egypt from 2011 to 2013, the countryside—what did this mean for the countryside? It was a revolutionary experience in the countryside but how did that connect with what was going on in Tahrir, in the cities? We have a much better sense of the revolutionary life of Alexandria, Port Said and of course Cairo than almost anywhere else even though most people live in those other places … ’.

He continues:

‘[T]the vulnerability of regimes is very differently posed in situations where such a large majority of the population is actually not par-dependent for getting by on a formal economy in any sense.’

6. Garbage and Urbanity/Rurality: Marx Revisited

The previous section has taken up aspects of Stephen Graham’s reference to ‘vanity and violence’, and Mitchell’s discussion of the differing impacts after Egypt’s 2011-2013 revolution in the cities and countryside. It can be argued that it is the Republican elite, liberal opinion and too many excessively crusading and naïve journalists that have been trumped. But, as briefly explored here, the way out involves working with use values, energies, dreams and skills based on and tested in the countryside, 'urban' areas and peripheries. Such actions, such a movement of counter-trumping has to be grounded. Marx’s Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, the exchange-use value distinction, and new confirmation that Marx did go beyond the exclusively capitalistic urban v. rural development model in the last years of his life, suggests valuable lines of analysis and action.Footnote12

A final dialogue: with Nasser Abourahme

‘What is the connection between the insight that we need more thought about how people do this extraordinary job of getting by across the urban-rural divide, on the one hand, and the resurgence of right wing populism in Trump, on the other. The suggestion seems to be that Trump will only intensify the need both to develop skills and our knowledge as to how this is done.’

‘What I have in mind is between seeing this crouching figure as abject (the negative association with inert garbage) or as watching, reflective, tensile, perhaps transformative (associated with the sorting, dynamic exchange to use-value aspect of garbage).’

‘Are you suggesting the informal spaces like Garbage City are a symbol in that they augur something for our common spatial future? Or more that they can become a source of knowledge or skill in imagining and planning a possible future?’

‘I think the tension between the abject and the watching, transformative is apt. There is a pathos in the image, but the figure is also looking back, returning the gaze, and more still is a subject of work (a worker even in the absence of formal work or employment). More important, I think is your point about the dynamic movement from exchange to use value with the garbage.’

Notes

1 ‘Trump in the White House: An Interview With Noam Chomsky’, Monday, 14 November 2016, 00:00. By C.J. Polychroniou, Truthout | Interview).

2 Interview, spring 2015.

3 The notion of grounding was explored in our previous editorial: 'Grounding technical democracy and critical urban studies', City, 20 (4), pp. 517–522. This editorial, completed in mid-December, is in a sense both a sequel to that and a prequel to the next one in that it only touches on some topics and groundings referred to before, particularly negative tendencies (perhaps pertaining to fascism) in the USA and elsewhere and on the major environmental topic, climate change, that is the primary concern of the Chomsky interview quoted as an epigraph here.

4 Dimtris Dalakoglou, 2016, 'Europe’s last frontier: The spatialities of the refugee crisis’, City, 20 (2), pp. 180–185.

5 See our previous editorial.

6 We shall be returning to Adrian Atkinson's earlier seminal accounts of the nature and implications of ‘deep-seated transition'.

7 See Mark Davidson and Kurt Iveson, 2015, ‘Beyond city limits’, City, 19 (5), pp. 646–664.

8 The captions to the photos used in this article are those provided by the authors in their papers.

9 Some definitions selected from the Shorter English Dictionary on Historical Principles, Sixth edition, 2007.

10 Wikipedia.

11 ‘Trump's takeover of the GOP is now complete. With Romney's capitulation, few of note in the party stand opposed to the president-elect'. By Philip Rucker, The Washington Post (accompanied by a note: 'Sunday's Headlines: … - Trump's emerging Cabinet looking more conventional than many expected; Raw emotions persist as Trump prepares for presidency … ').

12 See, particularly G. Stedman Jones, 2016, Karl Marx: Greatness and Illusion, Allen Lane – see the final chapter, ‘Back to the Future’. This will be discussed in issue 20.6.