Abstract

This paper takes as its starting point the forcible closure of an art exhibit at the 2015 Venice Biennale in order to illustrate wider dynamics of rising Islamophobia across Europe today. THE MOSQUE was the Icelandic national contribution to the Biennale, an exhibit that lasted only two weeks before being shut down by the local authorities for ‘public safety reasons’. Presented in its press release as ‘merely a visual analog’ of a mosque, the installation was made ‘real’ as the Venetian Islamic community began using it as a site for gathering and prayers, an all-too-real performance that sparked protests and brought the installation’s closure. The fate of THE MOSQUE is a compelling story that speaks to a series of broader struggles over visibility and invisibility, and over who and what has the right to appear in the landscape of a European city. It speaks to the phantom menace of a fetishized Islam that is haunting Europe today, as nativist and anti-immigrant movements mobilize against perceived threats to imagined urban orders.

1. Machines of spatial disorder

The Venice Biennale is one of the contemporary art world’s most important exhibition spaces. It not only brings to attention the international stars of the moment and serves to launch the careers of new ones, but also provides a stage for artistic practice from around the globe. As such, it has frequently served as a venue for the expression of quite explicitly political concerns, from critiques of authoritarian regimes, to installations challenging various forms of discrimination and inequality. The 56th Biennale taking place from May to November 2015 was hailed by the international media as ‘the most political yet’ (Dagen and Bellert Citation2015; Smith Citation2015). This was both because of the particular mix of exhibitions featured in the national pavilions (including an Armenian pavilion, reflecting on the centenary of the 1915 genocide, as well as that of Iraq, featuring art by exiled artists), but also because its central exhibition, curated by Okwui Enwezor under the heading of ‘All the World’s Futures’, made the iniquities of the contemporary global condition its pivotal theme.

Most of the installations that made up this central exhibit engaged directly with questions of space, territoriality, borders and the transforming geographies of cities under late capitalism, focusing in particular on the challenges of representing the ‘shape-shifting contemporary realities’, as the Biennale catalogue characterized them (Enwezor Citation2015, 18). Enwezor had engaged critically with spatial representations in numerous previous curatorial projects and essays, drawing attention to the possibilities afforded by the Biennale format as a unique ‘place-making device’, and as a ‘machine of spatial order and disorder, proximity and distance, intimacy and alienation’ (Enwezor Citation2008, 114, 127).

Many of the installations at the 2015 Venice Biennale were intended exactly as such ‘machines of spatial order and disorder’, though one exhibit certainly more than any other. Introduced in its press release as ‘a visual analog’ of a functioning mosque (Icelandic Art Center [IAC] Citation2015), THE MOSQUEFootnote1 was the Icelandic national contribution to the Biennale, an exhibit that drew protests even prior to its inauguration, and that lasted only two weeks before being forcibly shut down by the Venetian authorities, citing public health concerns.

The contestations surrounding the exhibit are worthy of critical attention for, in many ways, they reflect many other similar self-styled ‘citizens revolts’ against a purported ‘Islamization’ of European cities that have been the subject of a number of recent studies (Göle Citation2013a, Citation2015). Yet precisely because the Biennale MOSQUE was ‘merely a visual analog’, an art object, the political and popular reactions it provoked are perhaps even more revealing of the ways in which a diffuse fear of anything indicating Muslim presence has become a political obsession—almost, I will argue, a ‘fetish’—in today’s Europe, provoking what anthropologist Michael Fischer (Citation2009) (writing about the Danish Muhammad cartoon controversy a few years back) termed an ‘emotional excess’ (27).

Adopting the notion of the ‘fetish’ to analyse the vicissitudes of this Biennale exhibit can be useful both analytically and politically: to both better understand some of what is happening in European cities today, and to help de-potentiate the workings of this fetish, to help strip away its fatally attractive power in contemporary populist politics. As numerous commentators have noted, today’s European ‘obsession’ with Islam holds exactly such a fetish-like nature, not just in the term’s negative connotations but also in its attraction as an over-arching explanatory category (see, among others, Shyrock Citation2010—and for historical parallels with anti-Semitism, Kalmar and Ramadan Citation2016). Urban scholars in particular have noted how increasingly what are, in fact, broader ‘socio-political conflicts in European cities [are] presented as religious clashes’, with religious categories (and specifically the ‘Muslim’ one) increasingly used both as a descriptive and explanatory category to specify an ‘unbridgeable gap between different urban groups’ (see the review in Oosterbaan Citation2014, 592).

In the use that I want to make of the notion of fetish here, however, I borrow specifically from anthropologist Emmanuel Terray, writing over a decade ago right in the midst of the debates about the headscarf ban in France.Footnote2 What I want to add to Terray’s analysis, however, is a spatial component, trying to understand how the fetish works in and through urban spaces (both real and ‘analog’), and asking whether artistic spatial interventions like the Biennale can (at least temporarily) disrupt its workings and open new moments and spaces of political possibility; whether such spatial interventions can, in some way, disrupt the religious-civilizational rubric through which Europe’s relation to Islam is being scripted today (Göle Citation2013a, Citation2015).

Terray (Citation2004), in the essay he published on New Left Review entitled ‘Headscarf Hysteria’, frames his analysis by drawing upon the work of Hungarian historian Istvan Bibo, writing about the role of the fetish in inter-war politics:

‘When a community fails to find within itself the means or energy to deal with a problem that challenges, if not its existence, then at least its way of being and self-image, it may be tempted to adopt a peculiar defensive ploy. It will substitute a fictional problem, which can be mediated purely through words and symbols, for a real one, which it finds insurmountable. In grappling with the former, the community can convince itself that it has successfully confronted the latter. It experiences a sense of relief and thus feels itself able to carry on as before.’ (118)

The inter-war ‘fictional’ preoccupations that Bibo remarks upon parallel in disturbing ways contemporary European ‘politics of fear’, in both form and content, whether through their imagined confrontations with dangerous Others that threaten Europe’s and Europeans’ ‘very existence’, or in the creation of scapegoats (Wodak Citation2016, 2–4). Intimations of an inherently inimical relation between Europe and Islam are central to such imaginations: as Göle (Citation2006, Citation2013b) has argued, Europe is increasingly being seen as the ‘central site where the confrontation between two different sets of cultural values, two different orientations toward modernity [NB those of Islam and the “West”] is taking place’, with ‘the emergence of Islam in the European publics provoking a two-way relation that [threatens to] transform not only Muslims and Europeans but also the whole European project’ (Göle Citation2006, 145).

The encounter between Europe and Islam, Göle notes, is being resisted in much the same ways as those described by Bibo. As with the anti-Semitism of the inter-war years, a diversity of acts, actors and conflicts are all swept into one explanatory category of unbridgeable ‘Muslim difference’ and ‘civilizational warfare’: from the stereotyping of ‘Muslim refugees’ as roving sexual predators following the events of New Year’s Eve 2015 in Cologne (from whose aggression European women ‘must be protected’), to assertions by far-right parties like the Alternative für Deutschland that ‘Islam has no place in Germany’ (adopted as part of the party’s manifesto and echoed in just slightly more nuanced terms by the Austrian Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPO) that claimed first place in the initial round of the country’s presidential elections in April 2016, and came a very close second in the run-off the subsequent May and December).

As Ruth Wodak and others have argued (Mral, Khosravinik and Wodak Citation2013; Wodak Citation2016) the terms of nativist political rhetoric that inscribe the threat of ‘Islam in Europe’ work in just such all-encompassing, totalizing, ‘civilizational’, fashion. In today’s nativist politics, the reaction to ‘anything Muslim’ is akin to the emotional response provoked by fetish: a call to delimit and secure it, or better yet to remove it (physically—or at least remove it from view), believing that by doing so, the ‘bigger problem’ that it represents—the putative ‘Islamic threat’ to Europe’s very identity—will somehow go away with it, granting that ‘sense of relief’ that Bibo identified. Adopting the notion of fetish in no way intends to trivialize the increasingly violent reactions to Muslim presence across Europe. Rather, I would like to use the events in Venice to attempt to better understand precisely the ‘emotional excesses’ (Fischer Citation2009) provoked by Muslim spaces and bodies, querying what other modes of confrontation can be made possible by urban artistic interventions such as the Biennale one.

In the paragraphs that follow, I provide a description of the exhibit and some of its history, to then go on to consider its particular context: Venice itself. In closing, the fortunes of THE MOSQUE are set alongside broader debates about the politics of Muslim visibility in European cities today.

2. THE MOSQUE: is it, or is it not?

When the exhibit was first officially announced by the Icelandic Art Center and the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Iceland as that country’s contribution to the 2015 Venice Biennale, the press release noted that despite the project’s seemingly straightforward name it ‘would not be a functioning mosque’ (IAC Citation2015). ‘So what is it exactly?’, asked Andrew Russeth, co-editor of ARTNews, in his piece announcing the news of the exhibit a month prior to its opening. Citing the Icelandic Art Center’s press release, Russeth (Citation2015) noted that:

‘THE MOSQUE, as the work is being styled, will “serve as a place of activity for the Venice Muslim Community and will offer an ongoing schedule of educational and cultural programs available to the general public”, according to the organization’s news release, and will include “the physical attributes of Muslim worship—the qibla wall, the mihrab, the minbar, and the large prayer carpet oriented in direction of Mecca—juxtaposed with the existing Catholic architecture of the Church of Santa Maria della Misericordia in a visual analog”.’ (emphasis added)

THE MOSQUE was the work of Swiss artist Christoph Büchel. Prior to the Venice installation, Büchel was already well known for his projects that directly intervened into urban spaces and their uses, such as his transformation of a London gallery into an (apparently) fully functioning community centre (Piccadilly Community Centre Citation2011). Commenting on that previous installation, The Guardian’s Searle (Citation2011) surmised:

‘Büchel is literal-minded. But Piccadilly Community Centre is nevertheless impressively discombobulating. I have no idea how much it cost, and it clearly gives something to locals and other visitors who take it at face value. So what is this? Installation art? Community art? A tableau-vivant? Or a kind of immersive theatre in which we are the unwitting actors? Is it art—or life just tweaked a bit? All of the above.’

THE MOSQUE was similarly ‘discombobulating’ to art critics and visitors alike, a perfect ‘machine of spatial disorder’ to use Enwezor’s (Citation2008) term, a confusing presence in the Venetian landscape. ‘In a tranquil corner of Venice’s Cannareggio district stands a handsome church with an icing sugar-white baroque façade’, opened the piece on the exhibit by The Guardian’s Charlotte Higgins (Citation2015). ‘But … ’—the tranquil scene belies the unexpected, as this deconsecrated church, the Santa Maria della Misericordia, became as part of the Biennale THE MOSQUE—‘the first in this city’s long history’, Higgins noted ().

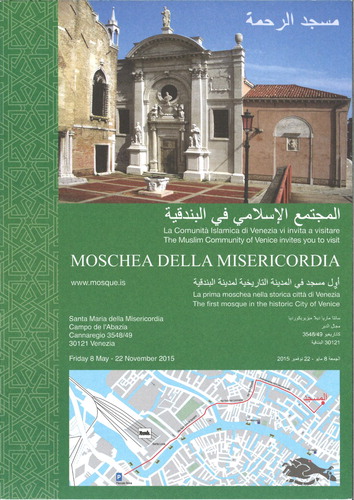

The ‘icing sugar-white’ façade of the exhibit during the time of its operation (8–22 May 2015) indeed displayed no indication whatsoever of that which lay within. Only once inside the main entrance, the glass panels of the interior wooden door announced ‘Centro Culturale Islamico di Venezia—La Moschea della Misericordia’ [Venice Islamic Cultural Centre—the Misericordia Mosque], with an Arabic inscription above. On a little table alongside the door, green flyers, featuring text in Arabic, Italian and English, announced: ‘The Muslim Community of Venice invites you to visit the Moschea della Misericordia’, ‘the first mosque in the historic City of Venice’. The flyer then provided the address (in Arabic and Latin script) and featured a photograph of the façade of the former Church of the Misericordia where the exhibit-mosque was installed, and a map tracing the route to it from the main parking structure and train station (). A web address was also provided: www.mosque.is

Apart from the curious ‘.is’ extension on the website, and the opening dates (8 May–22 November), there was no indication on the flyer that THE MOSQUE was in fact an exhibit associated with the Biennale. Only turning over the flyer, could one notice a very faint stamp in the bottom right corner:

‘Icelandic contribution to the 56th International Art Exhibition—la Biennale di Venezia. THE MOSQUE—Christoph Büchel in collaboration with the Muslim communities of Venice and Iceland. 9 May–22 November 2015’

Once inside, the main nave of the deconsecrated church had been converted into a space resembling that of a mosque prayer hall, with a prayer carpet covering the entire space, and other attributes of a functioning mosque, including a mihrab niche indicating the qibla (direction of Mecca), created in between two former altar spaces, and a minbar from which the imam could address the congregation ( and ).

In a room to the side, there was an information centre with a small bookshop selling Islamic texts and prayer aids, a children’s corner and library, and a space for consulting the information available, in print form and on a computer terminal set up in the back of the room. On the day of my visit (21 May, purely by chance the day before the exhibit’s forced closure), there were a number of curious visitors taking pictures, but also browsing through the library, reading the various flyers on the walls and perusing through the pamphlets placed on the tables, including one produced by the Islamic Community of Venice entitled ‘Che cose’ l’Islam?’ (‘What is Islam?’).

It was hard to tell if any or all of these visitors were Biennale patrons, or had simply come to THE MOSQUE attracted by the media publicity the exhibit had generated. At the same time, there were a number of young men who entered the prayer area; within the installation there was a delineation of a boundary between the (to be) religious and non-religious space, with instructions to visitors to remove their shoes and observe Islamic custom should they wish to enter into what was supposed to be the area of prayer.

It was these instructions and the delimitation of a ‘religious space’ that had particularly incensed local opponents, who lodged a protest with the city authorities within a couple of days of the installation’s opening noting that ‘since this is not a place of worship, rules pertaining to places of worship cannot be enforced’ (Mion and Mantengoli Citation2015, 20). Some particularly incensed local residents made the ‘shoe question’ into a rallying point, forcibly attempting to enter the space in shoes, ‘to see what these people can do to us’, as one woman cited in an article on Italian daily La Repubblica argued, ‘these people […] who consider women as inferior’.Footnote3 ‘They try to impose their rules on a work of art. Which, as such, is not a real mosque. But just try to keep your shoes on and see what happens’ (Berizzi Citation2015, 25).

Needless to say, nothing happened to visitors who wittingly or not violated the shoe rule.Footnote4 Nevertheless, the calls to violate the religious prescriptions of a to-be-Islamic space drew upon a much longer history of contestations in Northern Italy of ‘real’ spaces of Muslim religious practice, most famously the actions of the right-separatist Lega Nord politician (and for a time vice-president of the Italian Senate) Roberto Calderoli who had called for ‘A Pig Day’ to ‘infect’ land granted by municipalities for the possible construction of new mosques (Calderoli brought his own pig to stroll across the terrain of the land granted for the Lodi mosque in 2005) (La Repubblica Citation2007).

3. ‘This is not a piece of art’

‘Viewing the scene, Marco Polo would probably turn over in his grave: Gibrila Bagari, gardener from Burkina Faso, a long-term resident of Marghera [NB a suburb of Venice], is bowed praying, for real, on the green and red carpet in front of the mihrab niche that indicates the direction of Mecca.’ (Berizzi Citation2015, 25)

There are approximately 20,000 Muslims who live and work in Venice and its surroundings, and who for 15 years have been campaigning to have a site for prayer within the city, without having to travel over an hour to reach the nearest mosque on the mainland. The project for THE MOSQUE was thought up by Büchel partially in collaboration with the Islamic Community of Venice and the Association of Muslims in Iceland whose chair Ibrahim Sverrir Agnarsson was to preside over the installation for the duration of the 2015 summer. At the presentation of the initiative, Büchel argued, indeed, that part of his aim was to answer the community’s need for a gathering space but also ‘to bring to the fore Venice’s connections to the East’ (interviewed in Higgins Citation2015).

More will be said on the role of the Venetian context of the installation subsequently; suffice it to say for now that the connections that Büchel wanted to allude to are and have always been part of the myth of Venice as a maritime trading republic whose power at its height stretched across the Adriatic and Mediterranean and that for centuries was Europe’s ‘gate to the Orient’. The city today is a continued testament to that past, whether in the Byzantine-influenced architecture of its key landmarks like St Mark’s Basilica, or countless other material traces and presences that speak to the city’s ties to the Near East and the former Ottoman lands in particular, such as the turbaned figures that still stand watch on the Campo dei Mori, ‘the Moors’ Square’ (Howard Citation2000, Citation2002).

These historical presences were not ones that the opponents of THE MOSQUE wanted to see made visible in Venice’s historical centre, however; ‘a patrimony of European civilization that must be defended’, as flyers hung in protest proclaimed. Led by local politicians from the far-right Fratelli d’Italia party and the Lega Nord (that currently holds the regional governorship in the Veneto region), pickets began outside the installation the day of its opening. ‘This is an unauthorized place of worship—not a work of art. It must be closed immediately’ thundered Sebastiano Costalonga of the Fratelli d’Italia who also requested that the Venice municipality grant the party permission to distribute ‘informational material’ in the square outside of the installation (Mion and Mantengoli Citation2015, 20), ‘to let citizens know what is happening’. Emanuele Prataviera, deputy of the Lega Nord, was similarly dismissive of the idea that THE MOSQUE was ‘just a piece of art’.

‘It is not art […] it is a forgery [un falso artistico]. That in the space of a few days has been transformed into a place of worship. As a non-authorized space, it should have been made disappear within 24 hours.’ (Mion and Mantengoli Citation2015, 20)

While local politicians focused their calls for THE MOSQUE’s closure largely on the legal question of the functioning of an unauthorized place of worship in Venice, self-proclaimed ‘spontaneous citizens’ committees’ took on THE MOSQUE in the streets surrounding the installation through pickets and leafleting. One such leaflet, plastered across the fences of a construction site facing the Santa Maria della Misericordia, proclaimed ():

‘Iceland, as part of the 2015 Venice Biennale, created a mosque in the Church of the Santa Maria della Misericordia, violating and desecrating a symbol of our Christianity, culture and historical memory. Let us all stand up to this offensive and provocative act by a nation that appears to have still remained barbarian! BOYCOTT ALL OF THEIR PRODUCTS AND TOURIST BUSINESS (do not buy any “Made in Island” [sic] products or in the case of fish, those with the label “fished or raised in the North Sea”)’

The flyers featured prominently in their centre what was meant to be an Icelandic flag, with a large X across it—though the flag chosen was mistakenly the British one, drawing curious stares and then laughs from many of the tourists passing by ().

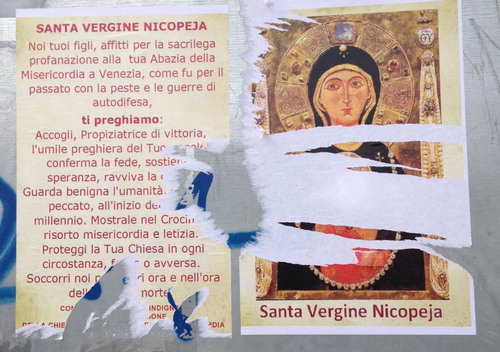

Another set of flyers on the streets surrounding the installation appealed to a different set of imagined historical geographies in contesting THE MOSQUE. These featured the Nicopeja Madonna, the icon of the Santa Vergine Nicopeja that since the 13th century hangs in St Mark’s Basilica, having arrived in Venice from Constantinople as part of the spoils of the Fourth Crusade. As legend has it, Venetians since that time have been particularly devoted to the Madonna, and the icon is said to have protected the city from war and pestilence through the centuries. Alongside a reproduction of the icon, the flyers on the walls of the buildings facing THE MOSQUE invoked:

‘Santa Vergine Nicopeja, we as your children, afflicted by the sacrilegious profanation of your Monastery of the Misericordia in Venice, as in the past for the struggle against pestilence and wars of self-preservation pray to you: take up, o beacon of victory, the humble prayer of your people, confirm their faith, sustain their hope […] Protect Your Church in all adverse circumstances. Come to our assistance in this hour of need’

Again, the appeals to divine protection against the profanation of a Christian space are not new in Veneto and Italian national politics. They are instantly recognizable to the public for they draw upon a by-now consolidated set of identitary discourses, promoted by the Lega Nord but also other right of centre politicians, focused on the threat of a putative creeping Muslim invasion of Italy and Europe, decried as ‘Eurabia’ (see Bialasiewicz Citation2006a, Citation2006b). Many of these appeals have engaged language and geographical imaginations that appear lifted directly from the Crusades, with some pundits infamously prognosticating an ‘Islamic reverse crusade’ threatening to ‘submerge and subjugate Europe’, through a creeping colonization of European cities by the infidel (Fallaci in Bialasiewicz Citation2006a). The question of THE MOSQUE on ‘sacred Venetian soil’ thus served as the spark for the revival of much longer standing political narratives.

When the local authorities decided to shut down the installation on 22 May, it was not formally due to any violation of religious or cultural sensibilities, or even the lack of a proper permit for a place of worship. It was the need to protect the Venetian public—not from ‘pestilence’, but something akin to it—that became the excuse to close down the exhibit. The Venice Procura announced that THE MOSQUE would be shut down for ‘public health reasons’, citing sanitary and fire safety regulations, applying regulations that usually govern ‘real’ places of worship and public gathering spaces (a strategy that has been deployed in initiatives to block the construction of mosques in other European cities—see, among others, Cesari Citation2005, and the edited collection by Göle Citation2015).Footnote5 The collage of photographs in published on the Venetian newspaper, La Nuova, is illustrative of the ways the ‘dangers’ to public health were depicted by the installation’s opponents: showing the teeming prayer space of THE MOSQUE and as a particular offence, in the centre, a pair of socks hanging off (what once was) the holy water font.

The closure of THE MOSQUE was in some ways unique in that the contest over the presence of an Islamic space of worship pertained to an artistic ‘analog’ of a mosque, not the proposed construction or use of a ‘real’ one. Yet even though THE MOSQUE was not ‘real’, it provoked a very real ‘emotional excess’, a very real set of popular and political reactions, becoming a fetish-object of Islamic presence to be eliminated. It became, to use Göle’s (Citation2009) phrasing (referring to another fetishized—and subsequently eliminated—art exhibit, this time in Vienna) ‘a momentbilder of a public constellation’ (295).

4. ‘That most improbable of cities’

‘As is often true of Venice, the real cannot be dissociated from its dramatic presentation.’ (Crouzet-Pavan Citation2002, xiii)

Before engaging some of the wider political implications of this episode, a brief reflection is in order on the Venetian context of these events, for it can serve as a revealing prism through which to consider some of THE MOSQUE’s spatial paradoxes and tensions, including the imagined as well as embodied geographies of the relation between ‘Europe’ and ‘Islam’.

Perhaps it is not by chance that a contestation over what is a ‘material’ space and what is imagined ‘opinion’Footnote6 took place in Venice, that ‘most improbable of cities’ (Martin and Romano Citation2000, 2). As historians of the Venetian empire have argued, the ‘myth of Venice’ has always been that of a city conjured up by the ingénue and hard work of its inhabitants; a city ‘miraculously self-constructed’, that emerged out of the waters of its surrounding lagoon and was made-into-being, island after filled-in island, out of the mud of the swamps (Crouzet-Pavan Citation1992, Citation2002).

This ecological myth of the city that Crouzet-Pavan (Citation1992) describes in her work also relied, however, upon a broader mise en scène that performed and affirmed Venice’s dominant place in the Mediterranean and Adriatic worlds. The material self-construction of the city cannot be dissociated, in fact, from how Venice imagined itself geographically into existence: through figuration in maps and paintings (Cosgrove Citation1982), but also the narratives woven by Venice’s historians, from its earliest days. The first written histories of the city emphasized the Venetian ‘miracle in stone’, the conscious making of ‘a place of order, beauty and urbanity’ (Crouzet-Pavan Citation2000, 41; see also the classic works by Lane Citation1973; Muir Citation1981).

This geographical imagination and material calling-into-being of the city was rendered even more powerful by a narrative of predestination: a unique site designated by Providence as the place where Venice’s glorious destiny would be fulfilled, ‘in a territory designated by God began a history willed by God’ (Crouzet-Pavan Citation2000, 42). As Crouzet-Pavan (Citation1992, 845) notes, the providentialist narrative of divinely ordained place-making continued to resonate not just in the early chronicles of the city from the 13th and 14th centuries, but well into the 15th, where it formed a cornerstone of the major political texts (and even the most routine legislative pronouncements of the city’s councils).

A crucial part of that narrative was the notion of duplicatio, specifying a political and spiritual community re-made (literally, ‘duplicated’) in a new setting (Crouzet-Pavan Citation1992). The power of the story of the duplicatio of Venice was fundamentally tied to, and supported by, another powerful narrative, that of translatio (Fortini Brown Citation1996). The notion of translatio, the symbolic inheritance and ‘transfer’ (‘translation’) of secular and religious power (in the case of Venice, the transfer of ecclesiastical but also temporal power from Byzantium) was sustained specifically by the story of the translatio of the body of St Mark from Alexandria. As the mythical tale recounts, in 829 two intrepid merchants from the Venetian lagoon islands of Malamocco and Torcello stole the relics of the body of St Mark from an Alexandrine church, succeeding in smuggling the body past Arab customs inspectors by covering it with pork. The body was brought to the ducal chapel in the heart of Venice, a chapel that would subsequently become St Mark’s Basilica. As was the case of other similar ‘holy thefts’, the transfer of the relics served to symbolically mark also the capture and transfer of ecclesiastical authority from Rome and the realm of Byzantium alike, with Venice claiming the inheritance of both Western and Eastern Christianity (see Geary Citation1978 on ‘furta sacra’).Footnote7

At the same time, the ‘divinely ordained’ possession of the relics was used to affirm Venice’s power-political claims on the Eastern Mediterranean and the lands and seas of Byzantium—and sanctioned the movement (largely through theft) of other Eastern objects to Venice, many as the spolia of the Fourth Crusade in the 13th century. A predominant part of St Mark’s Basilica is built of such objects, looted from Constantinople and elsewhere, from its marble pillars to the four bronze horses that adorn its entrance (Howard Citation2000, Citation2002). In the accounts of the chronicles of the time, the Basilica was ‘fabricada’ (‘fabricated’, in the literal but also figurative, artistic sense) as a place ‘re-placed’ elsewhere. Indeed, as Fortini Brown (Citation1996) has argued, Venice could in many ways be thought of as ‘an empire of fragments’ appropriated from elsewhere: a city literally re-made and re-placed of transported objects and the spolia of both its military and mercantile campaigns.

Along with the material incorporation of spolia, as was previously mentioned, the figurative arts were crucial in imagining and emplacing the ‘fabricated’ and ‘duplicated’ community of Venice. Denis Cosgrove (Citation1982, Citation2008) has analysed extensively the role of the arts and of a distinct ‘ritual geography’ in making the body politic of Venice, not only in affirming Venice’s geopolitical and economic dominance in the Mediterranean world, but equally importantly in serving to sustain a distinct vision of the city as ‘a perfectly governed, harmonious polity’. Painting in particular ‘acted as a spectacular mirror in which the world of Venice was reflected and enhanced’ (Daniels and Cosgrove Citation1993, 60), with two key figures in this regard being Gentile Bellini (1429–1507) and Canaletto (1697–1768). The arts were crucial not just in representing Venice’s power and vision of political community at home and abroad, however. As Howard (Citation2000) and others have argued, they were also, alongside commerce, the conduit for Venice’s relations and exchanges with the extra-European world, both with the Ottoman lands and with the farther Orient. Bellini himself is a revealing figure in this regard. Considered ‘the official’ painter of Venice, he was nonetheless commissioned by Venice’s sworn enemy and greatest rival, Sultan Mehmed II (‘Mehmed the Conqueror’ 1432–81) to paint his portrait (Campbell, Chong, and Howard Citation2005).

It is important to emphasize the fundamental role that such exchanges and forms of ‘dis-’ and ‘re-placing’ played in the making of the city, also to bring this history to bear on the fate of the Biennale MOSQUE. As Burke (Citation2000) and Howard (Citation2000, Citation2002) among others have argued, Venice would not have been Venice without such exchanges with the Islamic world, both material as well as figurative, reliant as the Venetian Republic was on its sustaining myths of translatio and duplicatio. But these forms of dis- and re-placement also speak to a distinct model of relations that the Republic had with its various ‘others’, others that through both physical and symbolic capture were ‘translated’ and ‘duplicated’ into the city’s spaces. In creating THE MOSQUE, Büchel was (perhaps unknowingly) invoking this very history of direct material incorporation of the Muslim Orient into Venice’s urban landscape. In 2015, however, unlike in centuries past, the (re)creation of a Muslim space provoked a very different reaction.

5. ‘Disturbing place’

In many ways, the fate of the Biennale MOSQUE reflects many similar contests over the building of ‘real’ mosques, in Italy and elsewhere in Europe. Over the past decade, a considerable body of academic work has examined the geographical politics of what has been (somewhat problematically) termed ‘the Islamization of space’ in European cities and, more broadly, the various ways in which Islamic presence in European cities has been subject to negotiation in different local contexts (see, among others, Allievi Citation2009; Cesari Citation2005; Gale Citation2004, Citation2005; Göle Citation2013a, Citation2015; McLoughlin Citation2005). Recent work by geographers and anthropologists on the racialization of spaces has extended this discussion in important ways by considering also the affective geographies generated by ‘Islamic spaces’ and ‘Islamic bodies’ (see especially the special issue edited by Tolia-Kelly and Crang Citation2010; also Astor Citation2014; Haldrup, Koefoed, and Simonsen Citation2006; Ruez Citation2012; Swanton Citation2010). Such studies have been particularly important in drawing out precisely the sort of ‘emotional excesses’ (that both Terray [Citation2004] and Fischer [Citation2009] identified with the fetish) provoked by the appearance of Islamic sites, bodies and objects in the spaces of European cities.

This work adds to other recent analyses that have focused on the ways in which state and local authorities in Europe have increasingly made Islamic spaces of worship the object of punitive regulation, such as the Swiss referendum in 2009 proposing a ban on minarets, voted in by an almost 60% ‘yes’ majority (see Antonsich and Jones Citation2010; Betz Citation2013; Ehrkamp Citation2012; Kallis Citation2013), and a similar ban proposed in Germany in 2016 by the Alternative für Deutschland (Deutsche Welle Citation2016). While no such proposals have yet been enacted at the national level in Italy, the construction of mosques across the country has encountered forceful local opposition for over a decade (see the discussion of the case of Lodi by Saint-Blancat and Schmidt di Friedberg Citation2005). Lombardy (currently governed by the Lega) recently attempted to impose a region-wide ban on mosque construction; the proposed regional law was, however, struck down in February 2016 by the Italian constitutional court, in a unanimous decision. As in other cases across Europe, since the Lega governor could not get away with directly banning places of Islamic worship, the proposed piece of legislation centred on the question of ‘proper’ appearance: it forbade the edification of buildings with ‘bell-towers that were too high’, and buildings that ‘would be in conflict architecturally with the Lombard landscape’ (Milella Citation2016).

On the Venetian mainland in Tessera, right across from Venice’s ‘Marco Polo’ airport, a new mosque is being built and most of the debates in the local and regional press have also focused on its prospected size, appearance and visibility. A comment on the local paper (Artico Citation2015) summed up the popular reaction succinctly: as long as it is an inconspicuous structure, blending into the warehouses and car dealerships that make up this strip of peri-urbanized countryside, ‘no one will complain’. The question of what is to be the consented visibility of the new Venetian mosque reflects reactions in other European cities. As analyses of cases in the UK and Germany have noted, ‘invisible’ Islamic religious spaces that occupy mundane buildings (i.e. what are termed ‘store-front mosques’) have not aroused the sort of reactions that purpose-built mosques have (see, among others, Ehrkamp Citation2012; Kuppinger Citation2011, Citation2014; Oosterbaan Citation2014).

Nonetheless, as Jones (Citation2010) has pointed out in his work, such mundane and invisible (or, as he terms them, ‘contingent’) spaces of worship raise important questions for how we interrogate questions of urban presence and absence, and the possibility for articulating inclusive urban identities. For while keeping spaces of Muslim worship ‘inconspicuous to non-attendees and thus absent in their presence’ (Jones Citation2010) may serve to preclude (perhaps) the sort of reactions that mosques-that-look-like-mosques frequently unleash, keeping such spaces ‘hidden’ also serves to maintain hidden their attendant communities, effectively sorting and segregating them not just out of sight, but also out of access to the public sphere.

Certainly, the relationship between visibility, physical presence in spaces and political inclusion is in no way straightforward: visibility and presence do not necessarily equal recognition, as Staeheli, Mitchell, and Nagel (Citation2009) have suggested. As they argue, ‘spatial strategies to gain visibility’ by marginalized groups do not necessarily ‘ease access to the public sphere or to the public’ (640). Such strategies may, at times, serve to create momentary entry points into the public realm, momentary ‘episodes’ of visibility and of ‘publicity’—that is, the opening up of certain qualities of the public such as ‘inclusiveness’ and ‘the capacities to engage in meaningful action’ (Staeheli, Mitchell, and Nagel Citation2009, 634)—but such episodes often remain precisely that, contingent and momentary.

Commenting on La Nuova newspaper in the days following the closure of the exhibit, Ida Zilio Grandi, Professor of Arabic Studies at Venice’s Ca’Foscari University, drew attention to precisely the lack of visibility—coupled with a lack of knowledge—that, to her mind, was in great part to blame for the reactions of the public to the Biennale initiative:

‘There is very limited knowledge of the Other [here], and no attempt to learn more. And then there is the tendency to confuse “real Muslims”, those who live alongside us and who we encounter daily, shopping at our same supermarkets, with some entirely abstract idea of “Islam” seen as a threat. […] Whether you like it or not, Muslims are also “us”. People forget that there are already Islamic places of worship here, just not visible ones. So the real problem is their emergence.’ (Mantengoli Citation2015)

The question of ‘emergence’ as Zilio Grandi highlights above is a crucial one: when local Islamic associations were first approached by the Icelandic Art Center and Büchel with plans for the initiative, the response was highly positive. A New York Times interview with Mohamed Amin Al Ahdab, President of the Islamic Community of Venice just days before the opening of the initiative summed it up: ‘Sometimes you need to show yourself, to show that you are peaceful and that you want people to see your culture.’ The Times reporter then went on to cite Hamad Mahamed:

‘a local imam who has been involved in the planning and will serve as the mosque’s leader […] “It’s important for us to do this”, Mr. Mahamed said, “to show people what Islam is about, and not what people see in the media.”’ (Kennedy Citation2015)

But how, where and by whom such ‘making visible’ occurs is not inconsequential. In her writings on the condition of the refugee, Hanna Arendt (Citation1943, Citation1958) argued that visibility in the public realm is constituent of full belonging to a political community, with what she describes in The Human Condition as a publicly recognized ‘space of appearance’ being the very foundation of entrance into the political world. At the same time, however, Arendt noted the concurrent necessity of a complementary ‘private’ sphere of ‘invisibility’—a space of ‘mere giveness’ that allows the political subject, the citizen, to be just what she or he ‘is’. The refugee, however, she argued, is both wrongfully invisible—and wrongfully visible at the same time. She/he is at once deprived of the possibility of appearing in public and denied access to the public ‘space of appearances’, while at the same time forcibly thrust into the public in ‘their natural giveness’ (Arendt Citation1951, 302).

A growing body of scholarship on the ‘illegalization’ of migrants in European cities has begun to draw on Arendt’s reflections to highlight what Borren (Citation2008) has referred to as ‘pathologies of in/visibility’. What such studies have remarked is the simultaneous denial of public visibility to migrants, with a forcible drawing of boundaries of who is allowed to appear in public space (physically, but also in the Arendtian political sense)—and at once the forcible ‘making visible’ of migrant bodies as a security and public threat (see, among others, Brambilla Citation2015; De Genova Citation2013).

The forcible ‘making visible’ of Islamic bodies and spaces in European cities today is frequently characterized by just such ‘pathologies of in/visibility’ (Borren Citation2008) or that which Nilüfer Göle (Citation2013b) terms ‘over-visibilization’:

‘we can speak of an “over-visibilization” in two senses. Public attention to Islam propels Muslims and Islamic symbols to the centre of the public space: clichés, images and representations of Islam proliferate in the spotlight. On the other hand, Islamic actors intensify their differences and render themselves more visible as they use the spotlight to gain access to the public space. Overexposure takes place, therefore, in both cases. This “over-visibilization” takes place in opposition to civic impartiality, which is necessary to public life. Far from being an expression of concerned attention or recognition, “over-visibilization” usually represents a manifestation of social disapproval.’ (8)

In the case of THE MOSQUE, it could be argued that the choice to locate the exhibit specifically in the spaces of a deconsecrated church (and not in one of the Biennale’s usual pavilions—or in another less religiously signified space in the city) contributed to an ‘over-exposure’ and ‘over-visibilization’ of the sort identified by Göle. It also contributed in unfortunate ways to feeding the clichéd representations of Islam that Göle identifies, and to precisely the civilizational rubric that nativist politics—not just in Italy—favours, providing an all-too-facile script (‘the invasion of a Christian space’).

The exhibit ‘over-exposed’ the Islamic community in another way as well, as a number of local commentators not inimical to the spirit of the initiative argued, inappropriately using it as ‘a tool of artistic provocation’. Felice Casson, well-known Venetian magistrate and Mayoral candidate for the centre-left at the time of the Biennale, expressed his feelings on the exhibit in these words: ‘Venice is a city that respects everyone but that also demands respect. […] One is free to pray everywhere, even in St. Mark’s Square […] But let’s use some common sense.’Footnote8 The national Catholic newspaper L’Avvenire (Citation2015) was similarly critical of the inappropriate nature of the ‘visibilization’ created by THE MOSQUE. Interviewed by the newspaper about the controversy provoked by the exhibit, Don Gianmatteo Caputo, the Venice Patriarchate’s Superintendent for Cultural Heritage, noted that the installation did more harm than good in facilitating any sort of productive religious or political dialogue, since the discussion it provoked simply ‘muddied the waters’, conflating the ‘legitimate right of the Islamic community of Venice to a space of worship’, with reactions to the exhibit itself. What is more, Don Caputo argued, THE MOSQUE ‘forced into the public eye’ the Islamic community in entirely inappropriate fashion, using it simply as ‘a provocation’ and denoting a profound lack of respect for its religious practice and spaces (L’Avvenire Citation2015).

Could THE MOSQUE have somehow avoided such ‘pathological’ (and, indeed, perhaps also exploitative) over-visibilization? In Biennale curator Enwezor’s (Citation2008, 123) words, politically ‘successful’ artistic interventions are those that are able to somehow:

‘“disturb the spatial coordinates of contemporary dwelling and place, re-articulating the ethical confrontation between the stranger and the neighbor”, making space for a “temporary autonomous zone” [NB as Hakim Bey Citation1991 terms it] of encounters’. (Enwezor Citation2008, 128)

THE MOSQUE, in many ways, did achieve precisely that: ‘making space’ for a ‘confrontation between the stranger and the neighbor’, albeit not the ‘ethical sort of confrontation’ that Enwezor envisioned. The exhibition did create a space of public encounter, albeit not entirely of the emancipatory kind. As Merrifield (Citation2012, 278) has argued on the pages of this very journal, urban ‘spaces of encounter’ are ‘spaces in which social absence and social presence attain a visible structuration’; they are spaces that ‘enable public discourses, public conversations’. As he notes, such spaces of encounter allow ‘people to collectively […] publicly define themselves’.

It could be argued that the Biennale exhibit did just that: the MOSQUE-as-fetish gathered into it a panoply of social, political and cultural anxieties, and in the ‘citizens’ mobilization’ to expel it from the Venetian landscape allowed for the sort of collective and public self-definition that Merrifield writes about—here, against a perceived threatening Other, and a perceived ‘foreign’ threat to an imagined ‘native’ urban order. THE MOSQUE admittedly did open a political ‘conversation’ of sorts, also regarding ‘social absence and social presence’. Nevertheless, the ways in which this was achieved was highly problematic, playing with a forced visibilization of the local Islamic community as an ‘artistic provocation’.

The question remains, then, whether and how (and also where) artistic interventions can contribute to creating other ‘spaces of encounter’, giving voice and ‘giving space’, yet at the same time respectful of not contributing to such over-exposure and over-visibilization. Today’s European cities desperately require such spaces to disrupt the quotidian politics of exclusion that increasingly fetishizes the fear of Muslim presence, quotidian politics that both feeds upon, and feeds into, global geopolitical narratives of difference and danger.

Acknowledgements

The research for this article was supported by a Bronislaw Geremek Fellowship at the Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen in Vienna. I would like to thank my colleagues at the IWM for their critical input into an earlier version of this paper, presented in Vienna in the spring of 2016, as well as CITY's reviewers for their very valuable suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

ORCID

Luiza Bialasiewicz http://orcid.org/0000-0003-0011-9418

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Luiza Bialasiewicz

Luiza Bialasiewicz is Jean Monnet Professor of EU External Relations in the Department of European Studies at the University of Amsterdam.

Notes

1 The original exhibit title was in capital letters, with the subtitle ‘The First Mosque in the Historic City of Venice’ (Icelandic Art Center Citation2015).

2 I would like to thank Andreas Malm for first bringing Terray's work to my attention, in our co-authored piece ‘Bloodlands’ (Malm Citation2012).

3 The appeal to protecting ‘women's rights’ has become an unfortunate part of European nativist politics over the past decade, with what scholars have dubbed a ‘culturalization of citizenship’ that now invokes the protection of gender equality and women's and LGBTQ rights as a mode of exclusion (see, among others, the edited volume by Duyvendak, Geschiere, and Tonkens Citation2016).

4 The Icelandic Art Center (IAC) in Reykjavik, the organization that had commissioned the installation, responded directly to the ‘shoe controversy’: ‘Visitors to THE MOSQUE project are NOT required to remove their shoes nor cover their heads with veils. Inside the exhibition in the Pavilion there is a sign SUGGESTING that visitors remove shoes as a part of the exhibition and the installation, and as a way to respect the cleanliness of the site. Veils are provided for OPTIONAL use by anyone wishing to use them. It is entirely left up to visitors to choose whether to remove or wear their shoes, and whether to try wearing a veil’ (Icelandic Art Center Citation2015; emphasis in original).

5 Under the heading of ‘Important Corrections Regarding Media Coverage of the Icelandic Pavilion at La Biennale di Venezia’, released on 27 May, a week after THE MOSQUE's forcible closure, the IAC disputed claims made on the local and Italian media regarding everything from the process of obtaining the legal permits for the exhibit, to contestations of the fact that the space had indeed been deconsecrated (it was, in 1973, declared ‘fit for profane use’ by the then-Patriarch of Venice). Nevertheless, the main impetus of the rebuttal focused on the nature of what this ‘thing’ was meant to be: ‘THE MOSQUE is an art project initiated by Iceland-based artist Christoph Büchel, who was commissioned by the Icelandic Art Center to take part in the 56th Biennale di Venezia. The installation is a work of art and claims to the contrary are misleading. Opinions about the art are invited and encouraged, and indeed their expression is part and parcel of THE MOSQUE project concept. But opinions are not facts’ (Icelandic Art Center Citation2015; emphasis in original).

6 These were the exact terms of the legal challenge to the closing of the exhibit, see above.

7 Although it was not until the 14th century, as Venice's political and economic power grew, that the full narrative of the translatio became a cornerstone of the political story that the Venetian empire recounted about itself, inscribed in the chronicles of the ruling Doge, Andrea Dondolo (Muir Citation1981, 86–87).

8 Casson was at the same time quite forceful in his support for the need for a ‘proper’ place of worship for the Islamic community in Venice and indeed his electoral list (lista civica) for the Mayoral election (NB Casson lost to the centre-right candidate Luigi Brugnaro in June 2015) included a number of representatives of the local Islamic community (Chiarin Citation2015).

References

- Allievi, S. 2009. Conflicts Over Mosques in Europe: Policy Issues and Trends. London: Alliance Publishing Trust.

- Antonsich, M., and P. I. Jones. 2010. “Mapping the Swiss Referendum on the Minaret ban.” Political Geography 29 (2): 57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.polgeo.2010.01.008

- Arendt, H. 1943. “We Refugees.” Reprinted in Altogether Elsewhere: Writers on Exile, edited by M. Robinson, 110–119. London: Faber & Faber.

- Arendt, H. 1951. The Origins of Totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt Brace.

- Arendt, H. 1958. The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Artico, M. 2015. “Ventimila musulmani: serve la moschea.” La Nuova di Venezia e Mestre, June 17. http://nuovavenezia.gelocal.it/venezia/cronaca/2015/06/17/news/ventimila-musulmani-serve-la-moschea-1.11635604.

- Astor, A. 2014. “Religious Governance and the Accommodation of Islam in Contemporary Spain.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 40 (11): 1716–1735. doi: 10.1080/1369183X.2013.871493

- L’Avvenire. 2015. “Venezia: ‘chiesa-moschea’? ‘Una provocazione’.” L’Avvenire, May 12. https://www.avvenire.it/agora/pagine/venezia-la-chiesamoschea-una-provocazione.

- Berizzi, P. 2015. “Tra i musulmani della chiesa-moschea. ‘Nessuna provocazione, vogliamo solo pregare.” La Repubblica, May 15, p. 25.

- Betz, H. 2013. “Mosques, Minarets, Burqas and Other Essential Threats: The Populist Right’s Campaign Again Islam in Western Europe.” In Right-Wing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discourse, edited by R. Wodak, M. Khosravinik and B. Mral, 71–87. London: Bloomsbury.

- Bey, H. 1991. Temporary Autonomous Zone. Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia.

- Bialasiewicz, L. 2006a. “‘The Death of the West’: Samuel Huntington, Oriana Fallaci and a new ‘Moral’ Geopolitics of Births and Bodies.” Geopolitics 11: 701–724. doi: 10.1080/14650040600890859

- Bialasiewicz, L. 2006b. “Geographies of Production and the Contexts of Politics: dis-Location and new Ecologies of Fear in the Veneto Città Diffusa.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 24 (1): 41–67. doi: 10.1068/d346t

- Borren, M. 2008. “Towards an Arendtian Politics of in/Visibility: On Stateless Refugees and Undocumented Aliens.” Ethical Perspectives: Journal of the European Ethics Network 15 (2): 213–237. doi: 10.2143/EP.15.2.2032368

- Brambilla, C. 2015. “Mobile Euro/African Borderscapes: Migrant Communities and Shifting Urban Margins.” In Borderities and the Politics of Contemporary Mobile Borders, edited by A.-L. Amilhat-Szary and F. Giraut, 138–154. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Burke, P. 2000. “Early Modern Venice as a Center of Information and Communication.” In Venice Reconsidered: The History and Civilization of an Italian City-State, 1297–1797, edited by J. J. Martin and D. Romano, 1–35. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Campbell, C., A. Chong, and D. Howard. 2005. Bellini and the East. London: National Gallery.

- Cesari, J. 2005. “Mosque Conflicts in European Cities: Introduction.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31 (6): 1015–1024. doi: 10.1080/13691830500282626

- Chiarin, M. 2015. “Casson: si puo pregare anche in Piazza San Marco.” La Nuova May 9. http://nuovavenezia.gelocal.it/venezia/cronaca/2015/05/09/news/casson-si-puo-pregare-anche-in-piazza-san-marco-1.11386372.

- Cosgrove, D. 1982. “The Myth and the Stones of Venice: an Historical Geography of a Symbolic Landscape.” Journal of Historical Geography 8 (2): 145–169. doi: 10.1016/0305-7488(82)90004-4

- Cosgrove, D. 2008. Geography and Vision: Seeing, Imagining and Representing the World. London: I. B. Tauris.

- Crouzet-Pavan, E. 1992. ‘Sopra le acque salse’: espaces, pouvoir et société à Venise à la fin du Moyen Âge. Rome: Ecole Française de Rome and the Istituto Storico Italiano per il Medioevo.

- Crouzet-Pavan, E. 2000. “Towards an Ecological Understanding of the Myth of Venice.” In Venice Reconsidered: The History and Civilization of an Italian City-State, 1297–1797, edited by J. J. Martin and Dennis Romano, 39–65. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Crouzet-Pavan, E. 2002. Venice Triumphant: The Horizons of a Myth. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. (original French (1999) Venise triomphante: Les horizons d’un mythe. Paris: Editions Albin Michel).

- Dagen, P., and H. Bellert. 2015. “De l’art, des armes et des larmes a la Biennale de Venise.” Le Monde, May 7. http://www.lemonde.fr/arts/article/2015/05/07/de-l-art-des-armes-et-des-larmes-a-la-biennale-de-venise_4629067_1655012.html.

- Daniels, S., and D. Cosgrove. 1993. “Spectacle and Text: Landscape Metaphors in Cultural Geography.” In Place/Culture/Representation, edited by J. Duncan and D. Ley, 57–76. London: Rouledge.

- De Genova, N. 2013. “Spectacles of Migrant ‘Illegality’: The Scene of Exclusion, the Obscene of Inclusion.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 36 (7): 1180–1198. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2013.783710

- Deutsche Welle. 2016. “German Populists AfD Adopt Anti-Islam Manifesto.” http://www.dw.com/en/german-populists-afd-adopt-anti-islam-manifesto/a-19228284.

- Duyvendak, J. W., P. Geschiere, and E. Tonkens. 2016. The Culturalization of Citizenship: Belonging and Polarization in a Globalizing World. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ehrkamp, P. 2012. “Migrants, Mosques and Minarets: Reworking the Boundaries of Liberal Democracy in Switzerland and Germany.” In Walls, Borders, Boundaries: Spatial and Cultural Practices in Europe, edited by M. Silberman, K. Till, and J. Wards, 153–172. New York: Berghahn.

- Enwezor, O. 2008. “Place-making or in the ‘Wrong Place’: Contemporary Art and the Postcolonial Condition.” In Diaspora, Memory, Place, edited by S. M. Hassan and C. Finley, 106–129. London: Prestel.

- Enwezor, O. 2015. “Introduction.” In All the World’s Futures. Exhibition Catalogue, La Biennale di Venezia, 18–19. Venice: Marsilio Editori.

- Fischer, M. J. 2009. “Iran and the Boomerang Cartoon Wars: Can Public Spheres at Risk Ally with Public Spheres Yet to be Achieved?” Cultural Politics: an International Journal 5 (1): 27–62. doi: 10.2752/175174309X388464

- Fortini Brown, P. 1996. Venice and Antiquity: The Venetian Sense of the Past. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Gale, R. 2004. “The Multicultural City and the Politics of Religious Architecture: Urban Planning, Mosques and Meaning-Making in Birmingham, UK.” Built Environment 30 (1): 30–44. doi: 10.2148/benv.30.1.30.54320

- Gale, R. 2005. “Representing the City: Mosques and the Planning Process in Birmingham.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31 (6): 1161–1179. doi: 10.1080/13691830500282857

- Geary, P. J. 1978. Furta Sacra: Thefts of Relics in the Central Middle Ages. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Göle, N. 2006. “Islam in European Publics: Secularism and Religious Difference.” The Hedgehog Review (Spring/Summer): 140–145.

- Göle, N. 2009. “Turkish Delight in Vienna: Art, Islam, and European Public Culture.” Cultural Politics: an International Journal 5 (3): 277–298. doi: 10.2752/175174309X461084

- Göle, N. 2013a. Musulmans au Quotidien. Une enquête européenne sur les controverses autour de l’islam. Paris: La Découverte.

- Göle, N. 2013b. “Islam’s Disruptive Visibility in the European Public Space.“ Eurozine. http://www.eurozine.com/articles/2013-10-11-gole-en.html.

- Göle, N. 2015. Islam and Public Controversy in Europe. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Haldrup, M., L. Koefoed, and K. Simonsen. 2006. “Practical Orientalism—Bodies, Everyday Life and the Construction of Otherness.” Geografiska Annaler, Series B: Human Geography 88 (2): 173–184. doi: 10.1111/j.0435-3684.2006.00213.x

- Higgins, Charlotte. 2015. “Artist draws controversy turning church into Venice’s first mosque.” The Guardian, May 8. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/may/08/biennale-artist-turning-church-into-venices-first-mosque.

- Howard, D. 2000. Venice and the East: the Impact of the Islamic World on Venetian Architecture, 1100-1500. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Howard, D. 2002, revised edition. The Architectural History of Venice. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Icelandic Art Center. 2015. http://icelandicartcenter.is/news/important-corrections-regarding-media-coverage-of-the-icelandic-pavilion-at-la-biennale-di-venezia/.

- Jones, R. D. 2010. “Islam and the Rural Landscape: Discourses of Absence in West Wales.” Social and Cultural Geography 11 (8): 751–768. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2010.521853

- Kallis, A. 2013. “Breaking Taboos and ‘Mainstreaming the Extreme’: The Debates on Restricting Islamic Symbols in Contemporary Europe.” In Right-Wing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discourse, edited by R. Wodak, M. Khosravinik and B. Mral, 55–70. London: Bloomsbury.

- Kalmar, I., and T. Ramadan. 2016. “Anti-Semitism and Islamophobia.” In The Routledge Handbook of Muslim-Jewish Relations, edited by J. Meri, 351–372. London: Routledge.

- Kennedy, R. 2015. “Mosque Installed at Venice Biennale Tests City’s Tolerance.” New York Times, May 6. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/07/arts/design/mosque-installed-at-venice-biennale-tests-citys-tolerance.html.

- Kuppinger, P. 2011. “Vibrant Mosques: Space, Planning and Informality in Germany.” Built Environment 37 (1): 78–91. doi: 10.2148/benv.37.1.78

- Kuppinger, P. 2014. “Flexible Topographies: Muslim Spaces in a German Cityscape.” Social and Cultural Geography 15 (6): 627–644. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2014.882396

- Lane, F. C. 1973. Venice: A Maritime Republic. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- La Repubblica. 2007. “Bologna, si infiamma lo scontro sulla moschea. Calderoli: ‘Un Maiale-Day contro l’Islam.’” La Repubblica, September 13. http://www.repubblica.it/2007/09/sezioni/politica/calderoli-moschee/calderoli-moschee/calderoli-moschee.html.

- Malm, A. 2012. “Phantom Islam: Scapegoat Fetishism in Europe Before and After Utoya.” In V. Bachmann, L. Bialasiewicz, J. Sidaway, et al., “Bloodlands: Critical Geographical Responses to the 22 July 2011 Events in Norway.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 30: 191–206. doi: 10.1068/d303

- Mantengoli, V. 2015. “Entra nella moschea senza togliersi le scarpe e chiama il 113.” La Nuova, May 10. http://nuovavenezia.gelocal.it/venezia/cronaca/2015/05/10/news/entra-nella-moschea-senza-togliersi-le-scarpe-e-chiama-il-113-1.11393239.

- Martin, J. J., and D. Romano. 2000. “Reconsidering Venice.” In Venice Reconsidered: The History and Civilization of an Italian City-State, 1297–1797, edited by J. J. Martin and D. Romano, 1–35. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- McLoughlin, S. 2005. “Mosques and the Public Space: Conflict and Cooperation in Bradford.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31 (6): 1045–1066. doi: 10.1080/13691830500282832

- Merrifield, A. 2012. “The Politics of the Encounter and the Urbanization of the World.” CITY 16 (3): 269–283. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2012.687869

- Milella, L. 2016. “La consulta boccia Maroni: Stop alla legge anti-moschee.” La Repubblica, February 24. http://www.repubblica.it/politica/2016/02/24/news/consulta_boccia_legge_anti_moschee_maroni-134123640/.

- Mion, C., and V. Mantengoli. 2015. “Chiesa-moschea, esposto in Procura.” La Nuova, May 14, p. 20.

- Mral, B., M. Khosravinik, and R. Wodak, eds. 2013. Right-Wing Populism in Europe: Politics and Discourse. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Muir, E. 1981. Civic Ritual in Renaissance Venice. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Oosterbaan, M. 2014. “Public Religion and Urban Space in Europe.” Social and Cultural Geography 15 (6): 591–602. doi: 10.1080/14649365.2014.922605

- Piccadilly Community Centre. 2011. http://www.piccadillycommunitycentre.org.

- Ruez, D. 2012. “‘Partitioning the Sensible’ at Park 51: Ranciere, Islamophobia and Common Politics.” Antipode 45 (5): 1128–1147.

- Russeth, A. 2015. “Swiss Artist Christoph Büchel, Repping Iceland in Venice, Will Stage Artwork Called ‘THE MOSQUE’ at a Disused Church.” ARTNews, April 30. http://www.artnews.com/2015/04/30/swiss-artist-christoph-buchel-repping-iceland-in-venice-will-install-artwork-called-the-mosque-at-disused-church/.

- Saint-Blancat, C., and O. Schmidt di Friedberg. 2005. “Why are Mosques a Problem? Local Politics and Fear of Islam in Northern Italy.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31: 1083–1104. doi: 10.1080/13691830500282881

- Searle, A. 2011. “Piccadilly Community Centre: Broken Britain Invades Westminster.” The Guardian, May 30. http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/may/30/piccadilly-community-centre-christoph-buchel.

- Shyrock, A. 2010. Islamophobia/Islamophilia: Beyond the Politics of Enemy and Friend. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Smith, R. 2015. “Art for the Planet’s Sake at the Venice Biennale.” New York Times, May 15. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/05/16/arts/design/review-art-for-the-planets-sake-at-the-venice-biennale.html?_r=0.

- Staeheli, L., D. Mitchell, and C. Nagel. 2009. “Making Publics: Immigrants, Regimes of Publicity, and Entry to ‘the Public’.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 27: 633–648. doi: 10.1068/d6208

- Swanton, D. 2010. “Sorting Bodies: Race, Affect and Everyday Multiculture in a Mill Town in Northern England.” Environment and Planning A 42 (10): 2332–2350. doi: 10.1068/a42395

- Terray, E. 2004. “Headscarf Hysteria.” New Left Review 26 (March-April): 118–127.

- Tolia-Kelly, D., and M. Crang. 2010. “Affect, Race and Identities.” Environment and Planning A 42 (10): 2309–2314. doi: 10.1068/a43300

- Wodak, R. 2016. The Politics of Fear: What Right-Wing Populist Discourses Mean. London: Sage.