Abstract

Today, municipal decision-makers, planners, and investors rely on valuation studies of ecosystem services, public health assessments, and real estate projections to promote a consensual view of urban greening interventions such as new parks, greenways, or greenbelts as a public good with widespread benefits for all residents. However, as new green projects often anchor major investment and high-end development, we ask: Does the green city fulfil its promise for inclusive and far-reaching environmental, health, social, and economic benefits or does it create new environmental inequalities and green mirages? Through case examples of diverse urban greening interventions in cities reflecting different urban development trajectories and baseline environmental conditions and needs (Barcelona, Medellin, and New Orleans), we argue that urban greening interventions increasingly create new dynamics of exclusion, polarization, segregation, and invisibilization. Despite claims about the public good, these interventions take place to the detriment of the most socially and racially marginalized urban groups whose land and landscapes are appropriated through the creation of a ‘green gap’ in property markets. In that sense, green amenities become GreenLULUs (Locally Unwanted Land Uses) and socially vulnerable residents and community groups face a green space paradox, whereby they become excluded from new green amenities they long fought for as part of an environmental justice agenda. Thus, as urban greening consolidates urban sustainability and redevelopment strategies by bringing together private and public investors around a tool for marketing cities with global reach, it also negates a deeper reflection on urban segregation, social hierarchies, racial inequalities, and green privilege.

Introduction

Interviewed by The Atlantic Citylab magazine about the future transformation of an old highway bridge into a park on the Anacostia River in Washington DC,Footnote1 Project Director Steve Kratz expressed anguish over the equity impacts of this green project. As his words about the new $45 million 11th Street Bridge Park denote, who are new urban parks really for? Who are the real recipients and beneficiaries of new or restored green amenities in cities? Boston’s Rose Kennedy Greenway and Philadelphia’s Penn Landing projects are illustrative of similar tensions. Indeed, if we look at the model for such projects, New York’s High Line, new parks are targeted to white and socially and economically-privileged residents and tourists (Reichl Citation2016). The High Line, a former elevated railroad restored and transformed into a linear urban park, is now visited by 5 million people each year and often modelled as a best practice in urban design and architecture. Yet between 2003 and 2011, property values near the High Line increased by 103 percent, raising questions about who has access to this green space.Footnote2 Rather than creating an inclusive space, this ‘green’ transformation has intensified the displacement of local businesses and residents. As High Line founder Robert Hammond observed eight years after its opening, ‘We wanted to do it for the neighbourhood … Ultimately we failed.’Footnote3

In this paper, we argue that academic and political discourses promoting the environmental, health, and socio-economic benefits of urban greening—what we call the ‘urban greening orthodoxy’—are generating powerful and seemingly immutable justifications for greening projects such as greenways, parks, or ecological corridors while minimizing their political ramifications and the highly inequitable socio-spatial outcomes that they intensify. In too many cases, the broadly defined ‘urban greening orthodoxy’—which includes the economic, environmental, cultural, and social values of ecosystem services and the socio-economic and health benefits of urban greening projects—advances an a-political, post-political (Swyngedouw Citation2007), and technocratic discourse of urban sustainability and overstates the positive impacts of green development while omitting a deeper consideration of the social and spatial impacts of the new green urban projects.

In that sense, this scholarship fails to consider the broader and deeper question of who has the right to a green city, and how ‘secure’ this right is over the long term. Additionally, and by minimizing the unequal impacts of green development, the presumed benevolence and democracy of this green orthodoxy obscures the ways that new green landscapes avoid questions of distribution and access through immutable (yet poorly evaluated) presumptions of publicness and public space and through participatory processes. Indeed, we question the capacity of this orthodoxy, claimed by communicative planning scholarship (Innes and Booher Citation2004; Healey Citation2005; Shapiro Citation2009) to mitigate these effects, especially so when the unequal impacts of urban greening are obscured and even made invisible in democratic processes. We argue that the urban greening orthodoxy is a powerful agenda setting tool that fails to take asymmetric power dynamics into consideration and therefore effectively limits the capacity of democratic dialogue and engagement to achieve a mutual understanding of the issues at stake and, from this understanding, envision just sustainability planning priorities that account for benefits, drawbacks, and continued access.

In this paper, we posit that, while greening cities as a catalyst for urban change is not new, green urban planning has shifted from the urban parks movement of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and the community-oriented greening that characterized neighbourhood reclamation efforts in the 1970s and 1980s (Jonnes Citation2002; Connolly et al. Citation2014) toward development-oriented greening. The new green paradigm is characterized by its presumed responses to environmental injustices, urban health issues, and climate crises. However, given that it takes place within urban contexts and sites that have been continuously devalued since the mid-20th century, it coincides with a strong movement back to the city and therefore acts as an anchor for major urban reinvestment and high-end redevelopment (Quastel Citation2009) and as re-attraction for privileged residents and visitors (Hutton, Casellas, and Pallares-Barbera Citation2009) at the expense of the most socially fragile and racially excluded residents that have, especially in the United States, remained in cities throughout decades of abandonment. In an age of booming real estate at the global scale, (Sassen Citation2011) we see that when neighbourhoods with depressed or below-market property values benefit from environmental clean-up and/or begin to receive new environmental goods, investors and developers together with municipal actors see an opportunity to finance new real estate projects, especially in areas with strong locational and infrastructural advantages. Once a first wave of daring pioneering gentrifiers moves into an area undergoing clean-up, those real estate actors have the ‘security’ that the area is ripe for further large-scale investment and green development. The unquestioned ubiquity and centrality of public-private partnerships means that cities are themselves central actors in shaping this new paradigm and opening up land for greening.

Extensive examples of municipally sponsored urban greening range in scale and location and include such projects as the recent 365 Bond luxury development along the Superfund Gowanus Canal in New York City. While the Gowanus Canal is still deeply polluted, the newly built 365 Bond condos offer ‘abundant green space and stunning views’ for urban residents.Footnote4 From Europe (cities like Glasgow, Leipzig, or Genoa) to South East Asia (Seoul, Jakarta), and Latin America (Medellin, Bogotá, Mexico City), the new green orthodoxy has a global reach as a combined redevelopment and urban sustainability strategy that brings together private and public investors, builds new flagship and boldly visible green amenities, markets cities as liveable and desirable places, and facilitates new real estate projects. In the process, new enclaves of green urban living are being created—at least for some. In this paper, we ask: For whom is the new green city? Does the green city fulfil its promise for widespread and inclusive health, environmental, social, and economic benefits or does it create and exacerbate environmental inequalities through new dynamics of exclusion silencing, and invisibilization of the most socially vulnerable residents?

Through case examples of green space and green infrastructure planning, we examine the emergence of an urban green paradox and of the diverse manifestations of what has been called GreenLULUs—Green Locally Unwanted Land Uses (Anguelovski Citation2015)—for long-term marginalized urban residents. Existing environmental justice literature defines LULUs in marginalized neighbourhoods as undesired sites such as landfills, incinerators, and other toxic and contaminating industries—mostly because of their disproportionate locational impacts on minorities and lower-income residents (Bullard Citation1990; Bryant and Mohai Citation1992; Lerner Citation2005; Schively Citation2007; Sze Citation2007; Downey and Hawkins Citation2008; Mohai, Pellow, and Roberts Citation2009). We argue here that, despite being framed as a public good for all residents, urban greening interventions increasingly create dynamics of exclusion, polarization, segregation, and invisibilization to the detriment of the most socially and racially marginalized urban groups whose land is appropriated through a ‘green gap’ process and who are being excluded from these benefits. When green amenities become GreenLULUs in urban distressed neighbourhoods (Anguelovski Citation2016), residents and community groups face a green paradox that generates a green mirage for those who are excluded from the benefits. In that regard, ‘green gentrification’ or ‘ecological gentrification’ (Dooling Citation2009; Checker Citation2011), which is the combined process of land revaluation, greening, and displacement, should be of central concern for ameliorating environmental, racial, and social injustices.

In the next section, we engage with the broadly defined urban sustainability literature and urban greening orthodoxy in the fields of public health, urban ecology, real estate economics, and urban planning, focusing specifically on the presumed benefits of urban greening. We then articulate our counter-view that urban greening poses new challenges for environmental equity and justice and democratic practice that are particular to the hegemony of neoliberal development paradigms. Next, we draw from our recent research in Barcelona, Medellin, and New Orleans to provide empirical examples in which we ground our discussion of green gentrification and exclusion. This variety of examples demonstrates the global reach of urban greening and of the green paradox for socially fragile residents. It also shows the extent to which the urban green paradox permeates urban development, planning discourses, and environmental interventions. We conclude with final remarks on the combined challenges of environmental gentrification and environmental injustice for urban planning scholarship and practice.

Urban greening, land re-valuation, and gentrification: questioning dominant narratives around green interventions in cities

Current dominant scholarly and policy narratives around municipal interventions for land (re)development and urban greening—park creation, waterfront restoration, or greenway construction—emphasize the ecological, health, social, and economic benefits of such projects. This well-developed literature, which we call the ‘urban greening orthodoxy,’ is represented by research on the benefits of access to or exposure to natural outdoor environments (NOE) in environmental epidemiology, the ecological and socio-cultural benefits of ecosystem services in urban ecology, and the economic and social benefits of urban greening for local economic investment and property values in real estate economics and, more generally speaking, urban planning.

From a health standpoint, being exposed to green space has been associated with improved physical and mental health outcomes, including chronic stress and depression (Triguero-Mas et al. Citation2015) and lower cardiovascular risks (Gascon et al. Citation2016). For instance, a cohort study on access to and use of green space in Europe has found that the prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and diabetes mellitus are significantly lower among residents using parks than among non-users (Tamosiunas et al. Citation2014). Green spaces have been linked to improved general self-perceived health, especially in women and residents living in lower density areas (Triguero-Mas et al. Citation2015). Exposure to green space is also positively associated with children’s cognitive development (Dadvand et al. Citation2015), with the association being partially mediated by reductions in air pollution. In view of these results, many environmental epidemiologists call for the future city to be green, active, social and healthy (Nieuwenhuijsen Citation2016).

In addition, literature in urban ecology highlights the widespread ecological benefits and ecosystem services from urban green spaces (Elmqvist et al. Citation2015)—from carbon sequestration to the removal of air pollutants to the prevention of carbon emissions (Baró et al. Citation2014) to natural flood prevention and mitigation to cooler temperatures within the city (Gómez-Baggethun and Barton Citation2013). For instance, in Manchester, recent research has identified that a 10% increase in tree canopy may lead to a 3 to 4 degree Celsius reduction in air temperature (Gill et al. Citation2007). The social benefits of ecosystem services also include increased job satisfaction and decreased job stress (Elmqvist et al. Citation2015), environmental learning, tighter social ties, or stronger place attachment (Andersson et al. Citation2015).

From an economic development standpoint, green space and green infrastructure promise economic growth and neighbourhood revitalization through real estate development, business creation (Dooling Citation2009; Quastel Citation2009) and tourism expansion. New green spaces and parks make neighbourhoods more desirable for potential residents and real estate investment, eventually contributing to increases in property values (Immergluck Citation2009; Sander and Polasky Citation2009; Conway et al. Citation2010; Brander and Koetse Citation2011) and thus to green gentrification. Research using hedonic pricing methods reveals that urban green infrastructure positively influence property values (Li, Saphores, and Gillespie Citation2015) and that large urban parks together with the percentage of a green space in a 500 m radius around residential properties contribute to increased housing prices (Czembrowski and Kronenberg Citation2016).

In urban planning, the green orthodoxy traditionally assumes the social and health benefits that individuals experience as well as the environmental and ecosystem benefits through pro-green development narratives and land development agendas and often utilizes democratic engagement to open up new green urban frontiers. Although the green orthodoxy in urban planning presents a seemingly immutable set of goods, this agenda setting occurs within the pervasive development epistemology of advanced capitalism (Brenner and Theodore Citation2002). Thus, the negative repercussions of greening or, more specifically, who will not benefit from the advancement of this agenda, and the role that greening plays in expanding the terrain of how inequality is shaped and exacerbated in the 21st century are all obscured. In other words, both democratic engagement and real estate development often conceal and therefore eclipse the new and unequal green landscape.

In view of the multiple accumulated benefits, urban greening is at the centre of planning utopian visions for new landscapes and, therefore gives cities a form of moral authority or economic imperative to become green(er). Many have developed sustainability plans as a demonstration of their commitment to this moral imperative for the provision or restoration of environmental amenities (Portney Citation2013). In this context, real estate developers and investors together with city planners and policy makers play a key role in producing a green city and, in return, helping to boost a city’s image as liveable and desirable, making it more competitive in the global market (Gibbs and Krueger Citation2007; Tretter Citation2013). That this ‘urban greening orthodoxy’ overlooks or invisibilizes the tensions and contradictions (i.e. Quastel Citation2009) derived from the ensuing inequities that stem from this new spatial development hegemony should, we argue, be of central concern.

The same concerns over the moral authority of greening can be applied to evaluations of communicative approaches to planning for urban sustainability planning. Communication- and dialogue-centered planning approaches are meant to promote participation and inclusion, build consensus on sustainability planning priorities and strategies, and secure durable decisions and plans, while avoiding top-down decisions (Innes and Booher Citation2004; Healey Citation2005; Shapiro Citation2009). Yet, the moral authority ascribed to urban greening and the global reach of the desirability of the green city have the potential to serve as an overriding agenda setting force, with very concerning implications for equitable green city planning. Not unlike the ideal of the ‘public good’ and the presumed diffused benefits of access, greening goals can serve as a means for deemphasizing asymmetric power relations and conflicts over competing resources, which risks recreating unjust outcomes (Flyvbjerg Citation1998; Yiftachel and Huxley Citation2000). In this case, the unjust outcomes arise around the issue of access to the benefits of urban (green) life in the mid- and long-term.

So, who is the green city really for? Recent research on ecological or environmental gentrification has shown that combined strategies of environmental clean-up, land restoration, and green amenity creation are increasingly remaking urban neighbourhoods for wealthier and whiter residents (Dooling Citation2009; Checker Citation2011). Banking on what we can call a ‘green gap,’ planners and investors are increasingly capitalizing on greening to attract more privileged residents with a higher purchasing (or rental) power (Bryson Citation2013; Rosol Citation2013). The green gap emerges when land deemed vacant, underused, or contaminated is identified by developers as a possible area to be ‘greened,’ generating amenities that may allow for higher economic value and profit accumulation. We should not forget that this new green frontier has been systematically devalued through ongoing racial (Omi and Winant Citation2014) and socio-economic processes. For instance, in San Francisco, the brownfield redevelopment and greening of the Hunters Point Shipyard area illustrates a vision for building an area attractive to creative class workers in search of high-end ‘sustainable’ lifestyles and green living in new luxury condos (Dillon Citation2014). Environmental gentrification in circumstances like these creates new types of urban spatial injustices over time (Dikeç Citation2001; Marcuse Citation2009; Soja Citation2009, Citation2010). That is, new patterns of unfair and inequitable distribution and allocation across space of socially valued resources — green amenities — are taking shape within numerous and varied contexts.

In other words, under apolitical and utopian claims that focus only on benefits, green engineering-driven interventions, and improving the biophysical urban environment, municipalities can sponsor and/or finance projects that produce and exacerbate highly inequitable outcomes (Wolch, Byrne, and Newell Citation2014). Many greening projects fail indeed to consider (or choose to simply ignore) residents’ social vulnerabilities to displacement, particularly residents of colour and low-income residents (Pearsall Citation2010; Checker Citation2011). Optimistic visions and discourses about the future green city and seemingly consensual discourses around urban greening projects undermine the possibilities for real politics, through what Swyngedouw qualifies as post-political and post-democratic tendencies (Swyngedouw Citation2007). Ignoring underlying social, economic and environmental vulnerabilities (Mueller and Dooling Citation2011) obfuscates the possibility of building more socially, racially and environmentally just landscapes (Steil and Connolly Citation2009; Connolly CitationForthcoming) rather than eroding them. In sum, while urban greening is increasingly framed as a path toward a technological and ecological utopia, this approach often avoids considering core urban issues at the intersection of racial inequalities, social and racial hierarchies, and environmental privilege (Anguelovski Citation2016).

We seek here to reframe urban greening within the day-to-day of urban planning as a profoundly political project that, despite optimistic and utopian intentions and framing, may generate spatial green segregation and environmental privilege. In the next section, we further develop our argument around the green city as a privileged socio-environmental space and illustrate it through three case examples.

Exclusion and displacement in green infrastructure planning: experiences from Barcelona, medellin and New Orleans

In this section, we present cases from our recent research in cities both in the Global North and South, for which we used a mix of quantitative and qualitative methods, to probe green gentrification and develop our argument around greening as redevelopment strategy, greenlulus, and the green paradox. The methods include regression and spatial analysis (Barcelona), semi-structured interviews and participant observation (Medellin), and planning document and project analysis (New Orleans). The diversity of methodological approaches provides a multi-perspective view of the emerging global trends generating green inequities. We also selected these examples because they represent different greening strategies, trajectories, and intentions in the Global North and South: park and garden creation (Barcelona), green infrastructure, landslide management, and growth control (Medellin), and resilience to climate change and flooding (New Orleans). Our cases demonstrate that the issues we raise are increasingly systemic across all of these greening approaches.

In addition to demonstrating the global reach of the green paradox, inequities produced by such projects seem to violate in a combined and self-reinforcing way the three legs of environmental justice: justice as equitable distribution of environmental goods, justice as recognition of identities and livelihoods, and justice as fair and meaningful participation (Schlosberg Citation2007). We do not claim here that all greening projects will provide new socio-spatial injustices—and many, especially those of smaller scale, vernacular design, and community-centred use are likely not to have such effects (Anguelovski et al. Citation2018). What our inductive approach reveals is that greening as a new urban brand used by larger cities in visible and flagship green projects risks creating new forms of environmental enclaves.

Green displacement and economic growth in Barcelona

The first case example we examine responds to an overarching empirical question: How does municipal park and garden creation contribute to demographic and real estate changes in socially vulnerable neighbourhoods? Here we argue that a shift occurred in greenspace planning away from a democratically controlled set of interventions for residents and toward a centrally controlled mechanism for attracting international capital, especially those in more centrally-located areas of the city. This process potentially intensified existing social vulnerabilities for many residents.

Barcelona is a rich case for examining this question because the city embarked on an aggressive campaign to add public green spaces to lower income and historically industrial areas since the late 1990s. During this time, 18 new municipal parks and gardens were built in the northern half of the city. In order to understand whether the distribution of new environmental amenities became more or less equitable as Barcelona implemented its greening agenda, two studies examined how housing and population trends changed in the area immediately surrounding these parks relative to the larger district in which they are located (Connolly and Anguelovski Citation2018; Anguelovski et al. Citation2018). The findings below report a condensed version of these studies.

The recent history of the discourse around municipal greening programmes in Barcelona might be characterized as progressively apolitical. In the late 1970s, greening was associated with building the public infrastructure of a newly democratic society. The legacy of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship, which ended with his death in 1975, left many Spanish cities with a poor quality-built environment (Sauri, Parés, and Domene Citation2009). While there was a citywide shortage of public parks and gardens (El verd: plantejament i diagnostic verd, 2010), the most socially vulnerable areas of the city had a particularly acute lack of green space. After the first municipal democratic elections of 1979, Barcelona’s City Council decided to prioritize increasing the number of parks and gardens through implementation of new urban plans. During this time, green spaces were primarily designed to provide neighbourhood meeting places and playgrounds for children and elderly residents (Sauri, Parés, and Domene Citation2009).

In 1986, when Barcelona was designated as the home for the 1992 Olympic Games, public green spaces began to be seen as a means for shifting the city toward large-scale redevelopment (Anguelovski Citation2014). The construction of public infrastructure moved during and after this time from an expression of rising democracy to one of democratic capitalism, and slowly capital took over. The City Council negotiated directly with developers that built the necessary infrastructure for the Olympics rather than with neighbourhood groups about the design and placement of green space. By the early 1990s, public parks design and construction was strongly linked to economic development and often used private funds (Montaner Citation2004; Sauri, Parés, and Domene Citation2009; Anguelovski Citation2014). The municipality focused on the last of the large areas of formerly industrial space such as the Poble Nou neighbourhood where a luxury residential project was anchored by the second largest public park in Barcelona. The park was the central component of the project’s sustainability strategy but was widely criticized for being designed as an amenity for the high-end condominiums on its border (Anguelovski Citation2014).

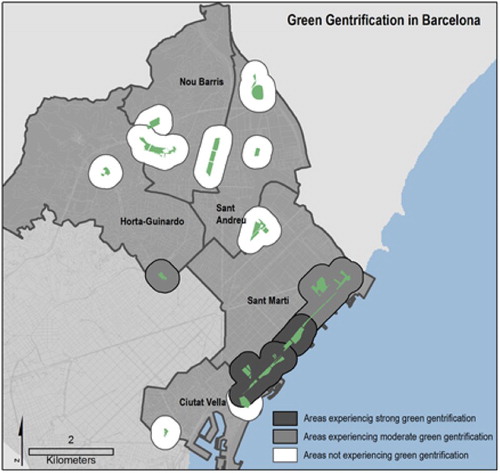

When thinking through the equity impacts of the increasingly development-oriented vision of greening in the new Barcelona economy focused on high human capital industrial growth, there are several groups of people that might be considered vulnerable to displacement. These groups include lower income residents, residents with a lower education level, elderly residents living alone, and low-income residents from countries in the Global South. In order to examine whether greening was potentially creating new social vulnerabilities for these groups, spatial analysis identified whether areas near parks experienced above normal changes by comparing the trends within 500 m of parks to those of the districts in which the parks are located. As well, the statistical significance of these trends was measured by running global ordinary least squares (OLS) regression to specify the model and local geographically weighted regressions (GWR) in order to identify where parks were likely playing a causal role in the changes observed. In order to determine the parks and gardens that appear to be associated with green gentrification, one point was assigned to parks with buffer areas that outpaced their districts and the points were summed to form a composite score from the five indicators identified in .

Table 1 Overall green gentrification indicator scores for parks within the study area of Barcelona.

Using these indicators, our studies found that several parks built in a time of significant urban revitalization associated with the Olympic Games experienced strong green gentrification (4 out of 4 rating). In addition, parks built later around redevelopment schemes experienced moderate green gentrification (3 out 4 rating). All other parks located in the northwestern and central zones of Barcelona did not produce strong indicators of green gentrification trends (1 or 2 out of 4 rating). The GWR findings supported these areas as those where distance to parks was a significant predictor of the given indicator, suggesting that these findings were not random artefacts of other geographic processes. summarizes the results, merging the buffer areas for parks that are close together.

Figure 1 Areas where strong, moderate, and no green gentrification seem to be occurring in Barcelona.

In sum, these results indicate that the impacts of park creation in socially vulnerable neighbourhoods depend on their context of creation, setting, and overall built environment. Parks located in extremely dense distressed neighbourhoods such as the Raval in Ciutat Vella (which also tend to be much smaller parks) or in neighbourhoods with stock associated with late dictatorship or early transition housing projects did not generate green gentrification. In contrast, greening in neighbourhoods with an industrial history and 19th or early 20th century housing stock and with much open vacant space is being capitalized upon by real estate investors and tech firms in a process of ‘green gap’ capture. We also found that more working-class ‘greened’ neighbourhoods such as Nou Barris seemed to see an increase in the proportion of socially-vulnerable residents. While those residents might be living closer to green space, those green spaces are often next to highways and in areas with worse housing conditions. The next steps are to examine how green amenities can be introduced to redeveloping districts with strong development pressures without making them instruments for gentrification.

Social vulnerability in greening, risk reduction, and growth containment initiatives: Medellin, Colombia

The second case example we examine responds to the overall question: How does city rebranding around ‘green’ and ‘resilience’ discourses and initiatives create displacement and exclusion? Here, we argue that containment, resilience, and beautification takes place through processes of land-grabbing and greening of poorer areas and transforming them into utopian landscapes of pleasure and privilege for a few—under discourses of ‘public good’ interventions.

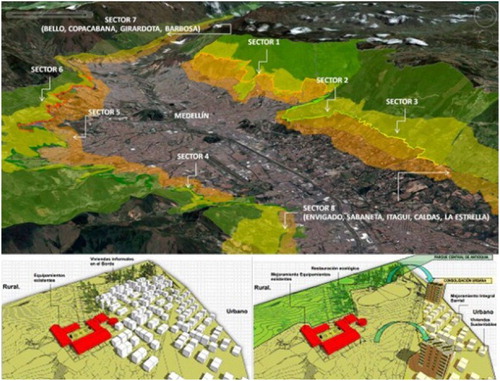

In 2012, the Municipality of Medellin, a city widely recognized for its daring ‘social urbanismFootnote5’ projects as tools for addressing violence and revitalizing self-built settlements, launched a new flagship project, the Metropolitan Green Belt. With a vision of urban growth and landslide risk reduction, the Green Belt is planned to be a 72 km2 green corridor around the city. Possibly affecting 230,000 residents living above an 1800-meter altitude limit, it is divided into a Zone of Protection (with nature reserves and ecosystem protection projects), a Zone of Transition (with new parks and risk mitigation measures for neighbourhoods lacking basic amenities), and a Zone of Consolidation (an area that requires structural housing and infrastructure interventions, including the construction of new social housing) (Agudelo Patiño Citation2013) (See ).

Figure 2 The sectors of Medellin affected by the Green Belt. Source: Empresa de Desarrollo Urbano (EDU).

One of the more acute conflicts that emerged in the context of the Green Belt has been the relocation of thousands of low-income residents from ‘non-recoverable areas’ because of estimated high risk of landslides or flooding. However, according to residents, the municipality is purposely overestimating the number and size of these non-recoverable risk areas to justify housing clearance and green infrastructure construction. Such a controversy reflects the socio-political nature of risk assessments and the conflicts that arise between top-down technical assessments and local knowledge. There are indeed differences between the rational ‘mapping’ of households living in ‘non-recoverable risk areas’ (called the Geological Aptitude Map, a map of geological risks associated with different land types) and residents’ estimates. Urban planning experts, engineers, and architects also consider that the municipality has not conducted adequate studies on risk mitigation (Anguelovski et al. Citation2016).

Personal field interviews conducted in Medellin in 2013 and 2016 also reveal that the municipality has not effectively responded to the concerns of low-income communities about relocation. For instance, in Comuna 8, community members opposed a planned relocation of 6600 residents (out of 14,750 residents) to further away public housing in tall tower-type buildings, many of them located away from jobs, sources of income, and valuable social networks (Personal Interviews 2016). Residents impacted by this green infrastructure perceive a risk of double trauma and displacement—once from the Colombian countryside in the context of the armed conflict and once more from the Comunas to palomeras (high-rise social housing buildings). Furthermore, the number of new units seems so far lower than the number of lost units. By contrast, higher-income neighbourhoods (El Poblado, Cedro Verde, Alto de las Palmas) and gated communities like Alto de Escobero are not being displaced and even further expand their development in areas close to forest reserves that lie beyond the border of the city. This last point illustrates the distributive inequities embedded in the Green Belt planning.

Also, the discourses and images built around the Green Belt indicate a municipal plan to attract outside visitors while dispossessing long-time residents of their green space for the formal recreation and esthetical pleasure of historically more privileged groups (participant observation of community meetings, 2013; interviews, 2016). On the Pan de Azúcar mountain, the municipality has built multiple hiking trails and bike paths that required the use of 10 meter-deep concrete pillars and the construction of stone and concrete-based paths and walls, without considering the existing walking paths built and used by residents (Chu, Anguelovski, and Roberts Citation2017). Here the city seems to have imposed a vision of what is an aesthetically and socially acceptable style of manicured, disciplined, and controlled nature, recreational use, and landscape while failing to recognize the ‘green’ identities and practices of local residents, especially those around ecological preservation and nature-based recreation (interviews 2016). By doing so, the Green Belt has also benefited the construction lobby that contributes to the construction boom in the city (i.e. Camacol). Such an approach confirms many community members’ and experts’ fear that the Green Belt will introduce more social-spatial inequities and that it represents a green mirage for residents whose cosmology and socio-ecological relationship have been invisibilized (Interviews 2016). Municipal councillors and planning experts concur with community concerns, and further argue that such a mega-project may raise land prices, lead to local tax increases, and eventually change the social composition of hillside communities because of increased pressure on land prices.

In addition to losing access to vernacular green spaces around the Pan de Azúcar mountain, low-income residents are losing access to land used for fresh food production, on which their livelihoods often depend. On the bottom part of the Pan de Azúcar, the municipality formerly parcelled out land for urban agriculture, but this land benefits only a few families, those who sell their products in high-end markets rather than within the community itself. This formalized urban agriculture contrasts with, overlooks, flattens, and eliminates existing farming community practices and food networks. It imposes an orderly, formal, and controlled imaginary for urban greening and agriculture while ignoring existing sustainable land uses.

In addition, these interventions reflect poor practices of public engagement and recognition of low-income communities’ development visions by the staff from the municipal company EDU and exacerbate procedural justice concerns. Residents in the Comuna 1, 3, and 8 are particularly vocal about the need for a different type of planning process, one that respects Medellin’s tradition of social urbanism and co-production of neighbourhood territorial redevelopment plans and projects.

In sum, the case of the Medellin Green Belt reveals that the uneven enforcement of land use regulations and evictions in the name of environmental risk management and growth control and in the context of green infrastructure planning results in wealthier formal settlements being given the right to remain in place and at the same time benefit from new green spaces. At the same time, poor informal communities are displaced or relocated, especially so as new real estate investors bank on ‘green gaps’ in the slopes of Medellin and further build the city. Green and resilience discourses and interventions can produce social and physical isolation and distress for vulnerable urban residents and thus contribute to further social vulnerability (Connolly Citation2018). They might also produce newly re-designed and re-created ‘natural’ utopian landscapes of pleasure and recreation for specific groups, while overlooking the importance of social cohesion, political recognition, and livelihood protection for the long-term wellbeing of low-income communities.

Uneven access to a greener and more resilient New Orleans

The third case example responds to the question: How does climate adaptation planning towards living with water in the city omit and invisibilize the most marginalized groups in the city? We argue that, in addition to ignoring community voice via resident participation (an important though somewhat obvious critique), climate adaptation planning can also invisibilize the latently racialized geographies within which it proposes solutions and spatial agendas and thereby exacerbate their claims to space and new amenities and decreased vulnerability.

Much has been written about post-Katrina urban planning (Hartman Citation2006; Kates et al. Citation2006; Peck Citation2006; Ehrenfeucht and Nelson Citation2011; Brand Citation2015), though less of this work focuses on the emergence of the green paradox in the post-Katrina redevelopment landscape. Many Post-Katrina planning efforts, including the city’s own post-Katrina Master Plan, centred on climate adaptation for this low-lying and increasingly vulnerable delta cityFootnote6 and, more recently, on reclaiming water as an asset and urban amenity. Briefly, three major planning efforts (the 2005–2006 Bring New Orleans Back Commission, 2007 City Council / Lambert Plans, and 2007 Unified New Orleans Plan) led up to and informed the city’s Master Plan (adopted in 2010) and its 2015 Comprehensive Zoning Ordinance (CZO). Each of these planning processes focused, to varying extents, on issues of stormwater management, subsidence and flooding from heavy rainfall events. Parallel to these planning processes, two other planning processes (the 2006–2010 Dutch Dialogues and 2011–2013 Urban Water Plan) focused specifically on re-envisioning how the city lives with water.

Based on Dutch stormwater management practices and led largely by a local architecture firm (later joined by local and international water management planners), the Dutch Dialogues and Urban Water Plan proposed wide scale visions for new water infrastructure systems across Orleans, St. Bernard and Jefferson Parishes. Funded by a $2.5 million grant from Louisiana’s Disaster Recovery Community Development Block Grants (CDBG-DR), the final plan includes an analysis of the regional stormwater management problems and identifies stormwater management principles that include slowing and storing stormwater (rather than pumping it out) and living with water (rather than trying to control nature).Footnote7 While city led planning processes all involved citizen participation (to varying extents), substantive citizen participation was not the focus of the Dutch Dialogues nor the Urban Water Plan planning processes. This omission is an important aspect of how these frameworks invisibilize marginalized communities and the potential unequal repercussions of environmental interventions in New Orleans.

To be clear, the push to rethink stormwater management centralizes latent issues of early 20th century development models that have exacerbated subsidence in the city’s lower-lying geographies and a forced-drainage stormwater system that is not only aging and flawed, but also contributes to subsidence and thus increased flooding.Footnote8 The city often receives rainfall at rates faster than its pumps can alleviate street level flooding, which contributes to personal property damage. Yet by pumping water out of the city, this same pumping system contributes to subsidence by prohibiting groundwater from infiltrating soils. In addition to flooding and subsidence, the Urban Water Plan argues that a third problem of wasted water assets results from the city’s pump and drain approach to managing stormwater, resulting in a loss of potential public space and urban amenities.Footnote9

The Urban Water Plan proposes to create smaller scale urban blueways and rain gardens and to redevelop over a large scale the city’s drainage canals and new waterways.Footnote10 As such, the proposals also vary in their scale of investment for new public infrastructure in a city already taxed in terms of its resources. Estimates for implementation range from $2.9 billion for ‘basic’ implementation to $6.2 billion for ‘intensive’ implementation (Fisch Citation2014, 48). Yet while we can think of these typologies and the concept of living with water as an effort to make this delta city’s blue context more visible, it is assumed that by transforming the city’s water and drainage infrastructure into an asset and enhancing the local green infrastructure we will enhance the value of public life while simultaneously improving the city’s ecological functions (See ).

Figure 3 Rendering, Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan. Source: Greater New Orleans Regional Economic Development, Inc.

As a spatial imaginary (Lipsitz Citation2011) and a socio-ecological utopia however, living with water is imposed onto the city through an analysis of the city’s environmental history and context and not its deeply and historically racialized landscapes, all of which have been exacerbated by the neoliberal redevelopment trajectory of the city post-Katrina (Johnson Citation2011; Brand Citation2015) (See ). Thus, the proposals and metrics for success are often abstracted from their possible impacts on lower-income communities of colour. In other words, while the flooding issues in New Orleans do directly impact citizens across race and class, water does not flood into an equal urban landscape.

The living with water framework, which the city has largely adopted in its own 2017 resiliency plan,Footnote11 invisibilizes minority communities through its superficial engagement with the ways in which racial inequality and urban development are (and have always been) geographically linked. While the city’s urban morphology has distinct environmental components, it also has a long history of racial geographic structuring that positions different communities and bodies differently within the post-Katrina recovery context (Brand Citation2012). Superficial commitments to equity or an equality based distributional approach rather than an equity based distributional approach (Brand Citation2015) do not in the short or long run address the everyday realities of racialized inequality that communities of colour live within. It is this context and this type of green mirage that go largely unaddressed in the move to live with water.

Importantly, our recent research (and that of other scholars) is finding that the full-scale adoption of these visions fails to centralize the unequal repercussions of urban green redevelopment (i.e. Birch et al. Citation2016). In a comparative study of New Orleans’s Resiliency Plan and the city’s other post-Katrina greening projects, Birch et al. (Citation2016) argue that the city’s substantial public investments are, coupled with increasing private development, contributing to green gentrification across the city. Despite its own rhetorical commitments to social justice and equity, the city’s own metrics for implementation focus on raising property values in a city, especially those located along the waterfront, that is facing gentrification and real estate speculation (Birch et al. Citation2016), and building new development projects. Environmental planning, despite its language of enhancing the aesthetic assets of the city and mitigating flood damage and the fact that the environmental benefits of these urban greening projects are minimal, contributes to unequal urban greening in a city facing exacerbated housing affordability issues since Katrina and ongoing geographic and environmental racism.

In addition to these critiques, which are necessary to the work of reimagining a more just green landscape, redevelopment visions such as the Urban Water Plan are themselves making a redistributive claim on the state for substantial public investment toward unjust social outcomes that are couched in a language that obfuscates these impacts, selling a vision of a green urban metropolis at the potential expense of everyone’s right to the city (Birch et al. Citation2016; Fisch Citation2014). There is an intentionality in this vision that, like projects uncritically drawing on New York’s High Line as a model, goes dangerously unaddressed. Green equity planning would necessitate dealing with the inequities that underlie the landscapes within which these visions propose a new future. New Orleans, both pre- and post-Katrina, is not unlike other American cities in its latent and ongoing landscapes of deeply racialized and environmental inequality. Without a lens that specifically takes up these issues within a redistributive framework, green plans such as the Urban Water Plan, cannot address the specificity of these contexts and will only serve to further generate ‘green gaps’ that benefit a few.

Concluding remarks

Today, a large ‘urban greening orthodoxy’ scholarship focuses on the numerous health, ecological, social, and cultural benefits of new green amenities while obfuscating the fact that large scale or flagship urban greening strategies are creating new socio-spatial inequalities over the short and long term. It is not disputed that greening provides benefits, but simply based on the mass of its findings and by using seemingly a-political language and discourse around urban sustainability, urban greening projects, and participatory green planning processes, such scholarship overlooks how racial inequalities, social hierarchies, and environmental privilege intersect in new urban greening projects. Building on these scholarly findings, as we have argued throughout this paper, under apparently technical and science- (or engineering-) driven agendas such as ‘greening,’ ‘sustainability,’ ‘resilience,’ or ‘climate adaptation,’ municipalities can champion greening interventions which create new socio-spatial inequities.

In fact, greening is now a successful and productive strategy for urban capital accumulation and for accumulating benefits from ‘green gaps’ while being presented as a public good strategy offering numerous benefits for all under an optimistic and utopian vision for a promising, green, and sustainable future. When public officials, planners, and scholars defend the argument of the ‘public good,’ they indeed often deemphasize asymmetric power dynamics and conflict over resources, which might end up recreating unjust outcomes (Flyvbjerg Citation1998; Yiftachel and Huxley Citation2000). In this case the public good is framed within a green utopia and unjust outcomes arise over access to and benefit from green amenities in the mid- and long-term. Because public problems cannot be solved by reaching toward a single notion of what is good in the eyes of those who have the most power, urbanization cannot be made sustainable through a solitary vision of green nor can more just urban landscapes be made via a vision that obfuscates injustice.

As our case examples reveal, in Barcelona, the creation of parks and gardens in more socially and environmentally-deprived areas seems to have contributed to substantial change in demographic and real estate variables to the detriment of lower-income groups, non-college educated residents, and residents whose nationality is from the Global South. Other newly-greened neighbourhoods seem to have gained residents from these backgrounds, but those neighbourhoods are also further away from the city centre, surrounded (in some cases) by highway networks, with poor housing conditions, and lower-quality or lower-accessibility parks. In Medellin, containment, beautification, and resilience through the greening of poor areas and through modern forms of land grabbing are transforming low-income areas into landscapes of pleasure and into controlled and ordered nature for a few. In the process of green infrastructure construction, many residents of low-income neighbourhoods are being dispossessed of community assets for the ‘greatest public good.’ In contrast to traditional gentrification processes, they are not replaced by wealthy newcomers (at least not yet), but by greenery and by outside visitors (and constructors) who shape it, control it, and benefit from it. Last, in New Orleans, new green infrastructure might contribute to higher property values through the planned expansion of waterfront development. It also includes new ‘privileged’ narratives of bringing back the creative (white) middle class to the city, while overlooking long-term inequities and racialized landscapes in land use development. Such developments risk creating new ecological enclaves of blue and green spaces and related geographies of exclusion.

In this essay, we demonstrate that while green urban planning is often framed as apolitical with win-win benefits for all urban residents, it is in fact increasingly used as a political tool for urban redevelopment and for addressing ‘green gaps’ while benefiting local and global elites. Our cases reveal examples of the lack of planning for equity in municipal neighbourhood sustainability projects and the absence of attention given to distributional, identity-based, and representational equity. The gentrification and social or physical displacement pressures green projects seem to trigger or accelerate in the cases presented here, together with the inability of the planning profession to address such impacts, create a green paradox for EJ organizations who may face tragic circumstances for efforts to make cities more sustainable where they are unable to defend greening projects that they long fought for and increasingly perceive green amenities as GreenLULUs for socially vulnerable residents. As a result, community-based counter movements against inequitable urban redevelopment and greening might be reduced to defensive moves and compromises, especially so in the technocratic decision-making and exclusionary processes embedded in traditional planning practice (Agyeman Citation2013).

Yet, we as scholars of urban planning and geography do not mean to argue that green planners intentionally target low-income neighbourhoods and communities of colour for increasing the profit of developers and for marginalizing vulnerable residents from the benefits of green projects. Our research points to the fact that planners are more likely to neglect the impacts of their plans on the exchange values of real estate and that they are often imprisoned in a logic of competitive urbanism and city (re)branding. That said, it is also true that they are becoming more aware of the impacts of green planning, cannot pretend to ignore what they are, and might even sometimes be contributing to them through plans and decisions they support.

We also defend ourselves from the dangerous argument (and what might be seen as a next logical recommendation and step), which would be to call for the elimination of new or restored green amenities in low-income neighbourhoods or communities of colour. Such decisions would further marginalize residents, concentrate green or sustainability investment in richer neighbourhoods, and eventually build new cycles of abandonment and disinvestment in distressed communities. By developing an argument around GreenLULUs and the paradox furthered by green utopias discourse, we aim at re-politicizing an a- or post-political sustainability discourse and pointing at the fact that green projects do not always—by far—bring win-win outcomes for all in the city. The question and challenge thus becomes: Which regulations, policies, planning schemes, funding mechanisms, and partnerships—and at which levels—can address the unwanted and new unequal impacts of green planning? In short, greening for whom?

This essential question demands a transformation of environmental planning practices, including tighter connections and commitments to public and social housing, funds for community wealth creation projects, community land trusts, and even municipal financing reforms. A transformative and equitable planning practice (Friedmann Citation2000, Citation2011; Sandercock Citation2004; Connolly and Steil Citation2009; Albrechts Citation2010, Citation2013; Fainstein Citation2010; Steele Citation2011; Song Citation2015) would indeed be one that puts race and class at the centre of green planning, considers how structural institutional inequalities have historically permeated the lives of marginalized low-income and minority residents, weighs in on the unintended (or intended?) role of green planning in (re)producing or aggravating race and class inequities in regards to accessing environmental goods, and substantively addresses tensions in order to co-produce new greener, resilient, and equitable urban communities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Isabelle Anguelovski http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6409-5155

James Connolly http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7363-8414

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Isabelle Anguelovski

Isabelle Anguelovski, PhD, Research Professor, Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability, Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals and Institut Hospital del Mar d'Investigacions Mèdiques.

James Connolly

James Connolly, PhD, Research Scientist Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability, Institute for Environmental Science and Technology, Institut de Ciència i Tecnologia Ambientals and Institut Hospital del Mar d'Investigacions Mèdiques. Email: [email protected]

Anna Livia Brand

Anna Livia Brand, PhD, Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture and Environmental Planning, College of Environmental Design, University of California, Berkeley. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 See interview in http://www.citylab.com/cityfixer/2017/02/the-high-lines-next-balancing-act-fair-and-affordable-development/515391/.

5 Social urbanism refers to large municipal investment into Medellin’s poorest and most violent neighborhoods during the 2000s, in an attempt to address violence and marginalization and to innovatively transform the city into a more equitable and livable place for all.

6 City of New Orleans, Plan for the 21st Century, 2010, https://www.nola.gov/city-planning/master-plan/.

7 See Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan, Principles: Adapting to the Flow, http://livingwithwater.com/blog/urban_water_plan/solutions/.

8 See Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan, Problems: http://livingwithwater.com/blog/urban_water_plan/problems/ and System Design and Analysis Reports: https://www.dropbox.com/s/c14h3k4tbvvlocu/GNO%20Urban%20Water%20Plan_Water%20System%20Analysis_13Oct2013.pdf.

9 See Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan, Problems, http://livingwithwater.com/blog/urban_water_plan/problems/water-assets-wasted/.

10 See Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan, Design: http://livingwithwater.com/blog/urban_water_plan/plan/.

11 City of New Orleans, Resilient New Orleans: Strategic Actions to Shape Our City, 2017, http://resilientnola.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Resilient_New_Orleans_Strategy.pdf.

References

- Agudelo Patiño, L. C. 2013. Formulación del Cinturón Verde Metropolitano del Valle de Aburrá. Medellin: Área Metropolitana del Valle de Aburrá and Universidad Nacional, Medellín.

- Agyeman, J. 2013. Introducing Just Sustainabilities. London: Zed Books.

- Albrechts, L. 2010. “More of the Same is not Enough! How Could Strategic Spatial Planning be Instrumental in Dealing with the Challenges Ahead?” Environment and Planning B: Planning and Design 37: 1115–1127. doi: 10.1068/b36068

- Albrechts, L. 2013. “Reframing Strategic Spatial Planning by Using a Coproduction Perspective.” Planning Theory 12: 46–63. doi: 10.1177/1473095212452722

- Andersson, E., M. Tengö, T. McPhearson, and P. Kremer. 2015. “Cultural Ecosystem Services as a Gateway for Improving Urban Sustainability.” Ecosystem Services 12: 165–168. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.08.002

- Anguelovski, I. 2014. Neighborhood as Refuge: Environmental Justice, Community Reconstruction, and Place-Remaking in the City. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Anguelovski, I. 2016. “From Toxic Sites to Parks as (Green) LULUs? New Challenges of Inequity, Privilege, Gentrification, and Exclusion for Urban Environmental Justice.” Journal of Planning Literature, 1–14. doi: 10.1177/0885412215610491

- Anguelovski, I., J. Connolly, L. Masip, and H. Pearsall. 2018. “Assessing Green Gentrification in Historically Disenfranchised Neighborhoods: A Longitudinal and Spatial Analysis of Barcelona.” Urban Geography, 39: 458–491.

- Anguelovski, I., L. Shi, E. Chu, D. Gallagher, K. Goh, Z. Lamb, K. Reeve, and H. Teicher. 2016. “Equity Impacts of Urban Land Use Planning for Climate Adaptation: Critical Perspectives From the Global North and South.” Journal of Planning Education and Research, 36: 333–348. doi: 10.1177/0739456X16645166

- Baró, F., L. Chaparro, E. Gómez-Baggethun, Johannes Langemeyer, David J. Nowak, and Jaume Terradas. 2014. “Contribution of Ecosystem Services to air Quality and Climate Change Mitigation Policies: The Case of Urban Forests in Barcelona, Spain.” Ambio 43: 466–479. doi: 10.1007/s13280-014-0507-x

- Brand, A. L. 2012. “Cacophonous geographies: The symbolic and material landscapes of race.” PhD, MIT, Cambridge.

- Brand, A. L. 2015. “The Politics of Defining and Building Equity in the Twenty-First Century.” Journal of Planning Education and Research 35: 249–264. doi: 10.1177/0739456X15585001

- Brander, L. M., and M. J. Koetse. 2011. “The Value of Urban Open Space: Meta-Analyses of Contingent Valuation and Hedonic Pricing Results.” Journal of Environmental Management 92 (10): 2763–2773. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2011.06.019

- Brenner, N., and N. Theodore. 2002. “Cities and the Geographies of ‘Actually Existing Neoliberalism’.” Antipode 34: 349–379. doi: 10.1111/1467-8330.00246

- Birch, T., M. Nelson, and A. L. Brand. 2016. “Greenways, Blueways, and a Rusty Rainbow: Assessing Resilience, Vulnerability, Equity, and Justice in Post-Katrina New Orleans.” Paper presented at the annual Conference of the American Association of Certified Planners, Portland, OR, November 3–6.

- Bryant, B. I., and P. Mohai. 1992. Race and the Incidence of Environmental Hazards: A Time for Discourse. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Bryson, J. 2013. “The Nature of Gentrification.” Geography Compass 7: 578–587. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12056

- Bullard, R. 1990. Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality. Boulder: Westview Press.

- Checker, M. 2011. “Wiped Out by the “Greenwave”: Environmental Gentrification and the Paradoxical Politics of Urban Sustainability.” City & Society 23: 210–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-744X.2011.01063.x

- Chu, E., I. Anguelovski, and D. Roberts. 2017. “Climate Adaptation as Strategic Urbanism: Assessing Opportunities and Uncertainties for Equity and Inclusive Development in Cities.” Cities (london, England) 60: 378–387.

- Connolly, J. Forthcoming. “From Jacobs to the Just City: A Foundation for Challenging the Green Planning Orthodoxy.” CITY.

- Connolly, J. 2018. “From Systems Thinking to Systemic Action: Social Vulnerability and the Institutional Challenge of Urban Resilience.” City and Community 17 (1). doi: 10.1111/cico.12282

- Connolly, J., and I. Anguelovski. 2018. Green Gentrification in Barcelona. Barcelona: Diputació de Barcelona.

- Connolly, J., and J. Steil. 2009. “Can the Just City be Built From Below: Brownfields, Planning, and Power in the South Bronx.” In Searching for the Just City: Debates in Urban Theory and Practice, edited by P. Marcuse, 1–16. London; New York: Routledge.

- Connolly, J., E. S. Svendsen, D. R. Fisher, and L. K. Campbell. 2014. “Networked Governance and the Management of Ecosystem Services: The Case of Urban Environmental Stewardship in New York City.” Ecosystem Services 10: 187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoser.2014.08.005

- Conway, D., C. Q. Li, J. Wolch, Christopher Kahle, and Michael Jerrett. 2010. “A Spatial Autocorrelation Approach for Examining the Effects of Urban Greenspace on Residential Property Values.” The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 41: 150–169. doi: 10.1007/s11146-008-9159-6

- Czembrowski, P., and J. Kronenberg. 2016. “Hedonic Pricing and Different Urban Green Space Types and Sizes: Insights Into the Discussion on Valuing Ecosystem Services.” Landscape and Urban Planning 146: 11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2015.10.005

- Dadvand, P., M. J. Nieuwenhuijsen, M. Esnaola, Joan Forns, Xavier Basagaña, Mar Alvarez-Pedrerol, Ioar Rivas, et al. 2015. “Green Spaces and Cognitive Development in Primary Schoolchildren.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 112: 7937–7942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1503402112

- Dikeç, M. 2001. “Justice and the Spatial Imagination.” Environment and Planning A 33: 1785–1805. doi: 10.1068/a3467

- Dillon, L. 2014. “Race, Waste, and Space: Brownfield Redevelopment and Environmental Justice at the Hunters Point Shipyard.” Antipode 46: 1205–1221. doi: 10.1111/anti.12009

- Dooling, S. 2009. “Ecological Gentrification: A Research Agenda Exploring Justice in the City.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33: 621–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00860.x

- Downey, L., and B. Hawkins. 2008. “Race, Income, and Environmental Inequality in the United States.” Sociological Perspectives 51: 759–781. doi: 10.1525/sop.2008.51.4.759

- Ehrenfeucht, R., and M. Nelson. 2011. “Planning, Population Loss and Equity in New Orleans After Hurricane Katrina.” Planning, Practice & Research 26: 129–146. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2011.560457

- Elmqvist, T., H. Setälä, S. Handel, S. Van Der Ploeg, J. Aronson, J. N. Blignaut, E. Gómez-Baggethun, et al. 2015. “Benefits of Restoring Ecosystem Services in Urban Areas.” Current Opinion in Environmental Sustainability 14: 101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.cosust.2015.05.001

- Fainstein, S. 2010. The Just City. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Fisch, J. 2014. “Green Infrastructure and the Sustainability Concept: A Case Study of the Greater New Orleans Urban Water Plan.” Master’s thesis, University of New Orleans.

- Flyvbjerg, B. 1998. Rationality and Power: Democracy in Practice. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Friedmann, J. 2000. “The Good City: In Defense of Utopian Thinking.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 24: 460–472. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.00258

- Friedmann, J. 2011. Insurgencies: Essays in Planning Theory. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Gascon, M., M. Triguero-Mas, D. Martínez, Payam Dadvand, David Rojas-Rueda, Antoni Plasència, and Mark J. Nieuwenhuijsen. 2016. “Residential Green Spaces and Mortality: A Systematic Review.” Environment International 86: 60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.10.013

- Gibbs, D. C., and R. Krueger. 2007. “Containing the Contradictions of Rapid Development? New Economic Spaces and Sustainable Urban Development.” In The Sustainable Development Paradox: Urban Politial Economy in the United States and Europe, edited by R. Krueger, and D. C. Gibbs, 95–122. London: Guilford Press.

- Gill, S. E., J. F. Handley, A. R. Ennos, and S. Pauleit. 2007. “Adapting Cities for Climate Change: The Role of the Green Infrastructure.” Built Environment 33 (1): 115–133. doi: 10.2148/benv.33.1.115

- Gómez-Baggethun, E., and D. N. Barton. 2013. “Classifying and Valuing Ecosystem Services for Urban Planning.” Ecological Economics 86: 235–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.08.019

- Hartman, C. W. (2006) There is no Such Thing as a Natural Disaster: Race, Class, and Hurricane Katrina. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Healey, P. 2005. Collaborative Planning: Shaping Places in Fragmented Societies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hutton, T. A., A. Casellas, and M. Pallares-Barbera. 2009. “Public-sector Intervention in Embodying the New Economy in Inner Urban Areas: The Barcelona Experience.” Urban Studies 46: 1137–1155. doi: 10.1177/0042098009103852

- Immergluck, D. 2009. “Large Redevelopment Initiatives, Housing Values and Gentrification: The Case of the Atlanta Beltline.” Urban Studies 46: 1723–1745. doi: 10.1177/0042098009105500

- Innes, J. E., and D. E. Booher. 2004. “Reframing Public Participation: Strategies for the 21st Century.” Planning Theory & Practice 5 (4): 419–436. doi: 10.1080/1464935042000293170

- Johnson, C. 2011. The Neoliberal Deluge: Hurricane Katrina, Late Capitalism, and the Remaking of New Orleans. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press.

- Jonnes, J. 2002. South Bronx Rising: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of an American City. New York: Fordham University Press.

- Kates, R. W., C. E. Colten, S. Laska, and S. P. Leatherman. 2006. “Reconstruction of New Orleans After Hurricane Katrina: A Research Perspective.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 103: 14653–14660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605726103

- Lerner, S. 2005. Sacrifice Zones: The Front Llnes of Toxic Chemical Exposure in the United States. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Li, W., J.-D. M. Saphores, and T. W. Gillespie. 2015. “A Comparison of the Economic Benefits of Urban Green Spaces Estimated with NDVI and with High-Resolution Land Cover Data.” Landscape and Urban Planning 133: 105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.09.013

- Lipsitz, G. 2011. How Racism Takes Place. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Marcuse, P. 2009. Searching for the Just City: Debates in Urban Theory and Practice. London; New York: Routledge.

- Mohai, P., D. Pellow, and J. T. Roberts. 2009. “Environmental Justice.” Annual Review of Environment and Resources 34: 405–430. doi: 10.1146/annurev-environ-082508-094348

- Montaner, J. M. 2004. “La Evolución del Modelo Barcelona (1979–2002).” In Urbanismo en el Siglo XXI: una Visión Crítica: Bilbao, Madrid, Valencia, Barcelona, 1st ed., edited by J. Borja, Z. Muxí, and J. Cenicacelaya, 203–222. Barcelona: Escola Tècnica Superior d’Arquitectura de Barcelona: Edicions UPC.

- Mueller, E., and S. Dooling. 2011. “Sustainability and Vulnerability: Integrating Equity Into Plans for Central City Redevelopment.” Journal of Urbanism: International Research on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 4: 201–222.

- Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. 2016. “Urban and Transport Planning, Environmental Exposures and Health-new Concepts, Methods and Tools to Improve Health in Cities.” Environmental Health 15 (1): S38. doi: 10.1186/s12940-016-0108-1

- Omi, Michael, and Howard Winant. 2014. Racial Formation in the United States. New York: Routledge.

- Pearsall, H. 2010. “From Brown to Green? Assessing Social Vulnerability to Environmental Gentrification in New York City.” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 28: 872–886. doi: 10.1068/c08126

- Peck, J. 2006. “Liberating the City: Between New York and New Orleans.” Urban Geography 27: 681–713. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.27.8.681

- Portney, K. E. 2013. Taking Sustainable Cities Seriously: Economic Development, the Environment, and Quality of Life in American Cities. London: MIT Press.

- Quastel, N. 2009. “Political Ecologies of Gentrification.” Urban Geography 30: 694–725. doi: 10.2747/0272-3638.30.7.694

- Reichl, A. J. 2016. “The High Line and the Ideal of Democratic Public Space.” Urban Geography 37: 904–925. doi: 10.1080/02723638.2016.1152843

- Rosol, M. 2013. “Vancouver’s ‘EcoDensity’ Planning Initiative: A Struggle Over Hegemony?” Urban Studies 50: 2238–2255. doi: 10.1177/0042098013478233

- Sassen, S. 2011. Cities in a World Economy. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Sander, H. A., and S. Polasky. 2009. “The Value of Views and Open Space: Estimates From a Hedonic Pricing Model for Ramsey County, Minnesota, USA.” Land Use Policy 26: 837–845. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2008.10.009

- Sandercock, L. 2004. Cosmopolis II: Mongrel Cities of the 21st Century. New York: Continuum.

- Sauri, D., M. Parés, and E. Domene. 2009. “Changing Conceptions of Sustainability in Barcelona’s Public Parks.” Geographical Review 99: 23–36.

- Schively, C. 2007. “Understanding the NIMBY and LULU Phenomena: Reassessing our Knowledge Base and Informing Future Research.” Journal of Planning Literature 21: 255–266. doi: 10.1177/0885412206295845

- Schlosberg, D. 2007. Defining Environmental Justice: Theories, Movements, and Nature. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press.

- Shapiro, I. 2009. The State of Democratic Theory. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Soja, E. 2009. “The City and Spatial Justice.” Spatial Justice 1: 31–38.

- Soja, E. 2010. Seeking Spatial Justice. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Song, L. K. 2015. “Race, Transformative Planning, and the Just City.” Planning Theory 14: 152–173. doi: 10.1177/1473095213517883

- Steele, W. 2011. “Strategy-making for Sustainability: An Institutional Learning Approach to Transformative Planning Practice.” Planning Theory & Practice 12: 205–221. doi: 10.1080/14649357.2011.580158

- Steil, J., and J. Connolly. 2009. “Can the Just City be Built from Below: Brownfields, Planning, and Power in the South Bronx.” In Searching for the Just City: Debates in Urban Theory and Practice, edited by P. Marcuse, 1–16. New York: Routledge.

- Swyngedouw, E. 2007. “Impossible Sustainability and the Postpolitical Condition.” In The Sustainable Development Paradox: Urban Political Economy in the United States and Europe, edited by R. Krueger, and D. C. Gibbs, 13–40. New York: Guilford Press.

- Sze J. 2007. Noxious New York: The Racial Politics of Urban Health and Environmental Justice, Environmental Justice in America: A New Paradigm. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Tamosiunas, A., R. Grazuleviciene, D. Luksiene, A. Dedele, R. Reklaitiene, M. Baceviciene, J. Vencloviene, et al. 2014. “Accessibility and use of Urban Green Spaces, and Cardiovascular Health: Findings From a Kaunas Cohort Study.” Environmental Health 13 (1): 1–11. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-13-20

- Tretter, E. M. 2013. “Contesting Sustainability: ‘SMART Growth’ and the Redevelopment of Austin's Eastside.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37: 297–310. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01166.x

- Triguero-Mas, M., P. Dadvand, M. Cirach, David Martínez, Antonia Medina, Anna Mompart, Xavier Basagaña, Regina Gražulevičienė, and Mark J. Nieuwenhuijsen. 2015. “Natural Outdoor Environments and Mental and Physical Health: Relationships and Mechanisms.” Environment International 77: 35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.01.012

- Wolch, J. R., J. Byrne, and J. P. Newell. 2014. “Urban Green Space, Public Health, and Environmental Justice: The Challenge of Making Cities ‘Just Green Enough’.” Landscape and Urban Planning 125: 234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.01.017

- Yiftachel, O., and M. Huxley. 2000. “Debating Dominence and Relevance: Notes on the‘Communicative Turn’in Planning Theory.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 24: 907–913. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.00286