Abstract

We need to retheorise urbanism from the perspective of smaller, post-colonial cities in the global South to account for both relational size on a global scale and localised city-specific contexts. Cities like Mangaluru, in south India, cannot be solely understood as mere variations within universal processes, especially when these processes are theorised through big cities in the global North. They must also be explored through detailed analyses that, whilst attuned to global processes, recognise historical and contextual particularities as key for understanding city-specific urbanisms. However, because inhabitants and state officials often frame smaller cities as mere variations—and often as inferior variations—of large ‘Western’ cities, we must interrogate how such universal, global North centred thinking informs the urbanism of such places. Taking a relational and relative understanding of smallness, the article conceptualises Mangaluru as a ‘smaller’ as opposed to just a ‘small’ city. Building on this, it is argued that smaller post-colonial cities in the global South are characterised by 1) niche positioning; 2) a feeling of relative lack; and 3) the dense intimacy of relationships. Furthermore, through an analysis of Mangaluru’s most common framings—as a port, as an education hub, and as a city of vigilante attacks—it shows how these dominant characterisations are exceeded and reworked amidst the unpredictability and flux of urban change.

Key words:

During the first week of what would become 18 months of ethnographic research in the south Indian city of Mangaluru (formerly Mangalore), a local businessman, who liked to tell me many elaborate stories, told me the following rumour,

‘When Indira Gandhi came to Mangalore to open the all-weather port in 1973, she spent her time on the flight buried in reports. As they came towards the city, one aide said to her they were soon to land, and so she looked out of the window. She saw the Netravathi River flowing down from the Ghats, she saw the Arabian Sea, she saw the hill-top airport, but she was confused. She turned to her aide and said, “but there's no city!?”’

We might suppose that a city in the erstwhile Prime Minister's imagination should break the tree line; but Mangalore then, unlike Mangaluru now, was a city hidden from above. Located in the south-west corner of the state of Karnataka on the shoreline of the Arabian Sea, Mangaluru is almost equidistant between Mumbai to the north and the tip of the country to the south—and it is changing fast. The recent boom in high-rise constructions; the setting up of Special Economic Zones; the fledgling arrival of IT and outsourcing companies; the rush to launch new colleges; the first signs of traffic congestion; unaffordable rents; shopping malls; air conditioned cinemas; Dominos and KFC; land grabs; and foreign investors—all this means that even those who fly down from Delhi would now recognize a city. Maybe, at a push, urban scholars might see a city there too? (see )

This article uncovers some aspects of a smaller city's urbanism; aspects of cityness that are usually considered to be the preserve of global metropolises. It is ironic that decade old calls for an urban studies that looks beyond the West (Robinson Citation2002) and for an urban studies that looks beyond the metropolis (Bell and Jayne Citation2006) have, for the most part, failed to cross-influence those who have attempted to follow these leads—notable exceptions include some chapters from Edensor and Jayne’s edited volume ( Citation2012) and Denis and Zérah’s focussed collection ( Citation2017). It seems especially strange as Robinson's ‘ordinary city’ argument and Bell and Jayne's ‘beyond the metropolis’ argument dovetail in that they both identify the problematic privileging of world cities as the sites from which urban theorisation flows. This hierarchical theoretical divide places both smaller and non-Western cities in a state of constant under-development, forever the poor relation of the true sites of urban modernity—the Chicagos, Londons, and New Yorks of the world.

Furthermore, debates in urban studies are often problematically framed as being inspired by either ‘post-colonial’ or ‘marxian’ approaches—something which can be said to be especially true in the Indian context (see: Shatkin Citation2014). The debate around whether to conceptualize the current worldwide process of urbanisation as ‘global urbanism’ (Sheppard, Leitner, and Maringanti Citation2013; Robinson and Roy Citation2015) or ‘planetary urbanization’ (Brenner Citation2013; Brenner and Schmid Citation2015) mirrors this to some degree. However, smaller cities in the global south like Mangalore—maybe precisely because urban theory has continued to theorize ‘over their heads’—suggests at least one way in which this divide can, and indeed should, be bridged.

It is certainly true that urban theory must move away from conceptualizing cities of the global South as mere ‘variations on a universal form’ (Robinson and Roy Citation2015, 1), however, urban theorists must also grapple with questions surrounding city size, because, as the case of Mangaluru shows, the empirical relational inequalities that frame the city as ‘small’ do so, in part, by upholding and deepening the idea that they are ‘mere variations’ (and inferior variations at that). As critical urban scholars we may be politically and analytically adverse to placing smaller cities of the global South in constant relation to the ‘proper’ large cities of the global North, but if our informants’ depictions, state funding streams and dominant imaginations of the city continuously reference this relation of size-based inferiority, then we must explore this. Whilst insightful, it is not enough to only note that there is a distinction between understandings of urbanization as ‘universal’ (cities as variations in form) and understandings of urbanization as ‘global’ (cities constituted by historical difference, yet part of global processes) and to choose to follow the global path, as Roy (Citation2015) has recently done. Rather—as a smaller-city perspective reveals—we must analyse the relation between the two, between the theoretical move to recognize historical difference and the tendencies towards variation centred universalism by the urban dwellers amongst whom we research.

Or, to approach this from the ‘other side’, it can certainly be said that Mangaluru's contemporary changes fit the broadly marxian thesis that urbanization is a planetary process involving concentration, extension and differentiation (Brenner and Schmid Citation2015). However, omnipresent size and southerness serve as a continual reminder that the urban (or the city) remain an empirical object for urban dwellers, planners and officials and, thus, should for its researchers too. Accordingly, whilst the case of Mangaluru does not disprove the argument that ‘the urban is a process, not a universal form … ’ (Brenner and Schmid Citation2015, 165) an analysis of Mangaluru does lead me to contend with the assertion that the urban is not a ‘settlement type or bounded unit’ (165). The smallness of smaller cities reminds us that we cannot discard the city so easily; a smaller city in the post-colonial global south is just the right city to help us understand the relationship between the process and the object: between urbanisation and the city.

How then to ‘size the city'? One method has been to take a certain class or classes of city, and declare these to be ‘small’, ‘medium’, ‘large’, with categorizations based on population the most common. For instance, according to the latest Census of India, Class I settlements have a population above 100,000 people; Class II a population between 50,000 and 99,999; Class III between 20,000 and 49,999; Class IV between 10,000 to 19,999; Class V between 5,000 to 9,999 whilst Class VI settlements have a population below 5,000. As per the 2011 census there were 468 Class I settlements, in which 264.9 million people reside (about 70 percent of the total urban population). 53 of these settlements have a population of more than 1 million. It is clear from even this cursory glance at the Class I categorization that it is far too broad to hold much meaning. In the last census this would have included both Mangalore and Mumbai. It is thus unsurprising that, in India, researchers have developed different categorizations of city size (e.g. Raman et al. Citation2015). However, whilst population of the area of a city is certainly important—not least to fit into central state schemata that open or close possibilities of funding—comparing cities in such absolute ways obscures as much as it reveals for qualitative research. For example, the epistemological framework of the official census is far removed from lived experiences in urban settlements (Sircar Citation2017). Moreover, cities, towns or smaller settlements are always changing size.Footnote1 As such, I choose not to place Mangaluru into a certain class or tier based on a comparative set of criteria.

How then, to measure the city? Or, to start from the particular, how small is Mangaluru? It is certainly smaller than Bengaluru, Mumbai and Mysuru but then it is also certainly bigger than Udupi, Bantwal, and Chikkamagaluru. Bangaloreans will tell you that Mangaluru is small, ‘like a village almost’, but for those from Bantwal, Mangaluru is a city with shopping malls, prestigious colleges and an international airport. It would be wrong to call it a small city, as it would be wrong to refer to it as a big city. Its size relates to its position in the state, national and global hierarchy of cities, an imbricated hierarchy which is highly contextual—put Mangaluru in Hungary and it would be twice as big as the second biggest city, and yet it is only the fourth largest city in the State of Karnataka. City size is best understood relationally and as dependent on particular contexts (Bell and Jayne Citation2009), accordingly, I argue it is not useful to think of Mangaluru as a ‘small city’ but rather a ‘smaller city’—the comparative adjective better capturing the relation-based categorization.

It could well be argued that such a label reflects a bias towards larger cities—why not refer to Mangaluru as a larger city, when it's population of 484,785, makes it the 93rd largest city in India (Government of India Citation2011)? Especially, when, if we count the urban region population of 619,664, the city is pushed up to 83rd largest. Should we also factor in the population density of the surrounding district of Dakshina Kannada, which at 457 people per square kilometre is more than that of the State (319) and the national (382) averages (Government of India Citation2011), making it the second most densely populated district in Karnataka after Bangalore Urban district? To do so, however, would miss that smallness/largeness is about more than just numbers; calling Mangaluru a larger city would miss how smallness is related to its very cityness: ‘the ways in which [city] smallness is bound up with particular ways of acting, self-images, structures of feeling, senses of place, aspirations’ (Bell and Jayne Citation2009, 690).

Mangaluru, like all Indian cities, is also sized and resized by different administrative, cultural, regional, linguistic, jati (caste) and national contexts; imbricated webs of relations, which settled and unsettle the city’s relative sizing as kingdoms rise and fall, states re-organize their internal and external borders and movements succeed or fail. The city, region, district, federal state and national state, as delineated bounded places can overlap and there is no neat dividing line between where the city starts and stops, with the ‘city-region’ stretching way beyond the official administrative bounds. Nevertheless, such official boundaries have real consequences and are also the containers for state-produced statistics, some of which can help understand how the city’s cityness is produced.

Since 1956 Mangaluru has been part of the linguistically defined state of Karnataka (though named the State of Mysore until 1973) (for the state’s creation see: Nair Citation2011). Karnataka (population 64.06 million) has 30 districts, with Mangaluru the administrative headquarters of the district of Dakshina Kannada (population 2.08 million). In the case of Mangaluru, statistics pertaining to land, labour and literacy give a fuller picture at a district level, and reveal that Dakshina KannadaFootnote2 has greater population density, more people in the labour force and higher literacy rates than the Karnataka average (see ). Mangaluru is also the largest city in the ‘cultural region’ of Tulu Nadu—the land of the Tuluvas, a linguistic-cultural group whose members can also be found in Udupi district and Kasaragod district (the latter district in the state of Kerala). Whilst there have been some attempts to make Tulu Nadu a separate federal state since at least the 1940s, for the most part the immediate demands of separatist groups are more modest—such as renaming the airport.

Table 1 Demographic profiles Dakshina Kannada, and Karnataka.

The city is also imbricated in changing jati relations. Some of these relate to feudal landholding patterns, for instance the traditional landowners such as Bunts, Jains and Brahmins remain relatively dominant in the city, both in terms of business and symbolic power (for Bunts see: Rao Citation2010). Meanwhile Dalit (once so called ‘untouchable’) jatis are still over-represented in outdoor and low paid work, and some (such Nalkes, Paravas or slightly higher placed and ‘non-polluting’ Pombadas) perform ‘traditional’ ritual functions as mediums in the widely practised spirit worship (bhuta or nema worship). Trading communities, such as the Gowda Saraswat Brahmins or Muslim Bearys, remain active in commerce, with many members of the latter group overrepresented in the regional trend for circular migration to the Gulf, the saving from which they invest in businesses in the city. Indeed, Gulf cities and Mumbai remain important reference points when discussing Mangaluru. Among the largest Christian jatis, Konkani speaking Catholics are relatively prosperous in comparison to Protestants, most of whom were ‘low-caste’ Billavas before conversion.

Jati relations are dynamic and unstable—for instance Billavas, erstwhile toddy tappers and the largest single jati in the region, are commercially strong and upwardly mobile, whilst members of the Mogaveera fishing community, whilst often still involved in fishing, have also diversified into numerous fields. Meanwhile, Dalit jatis have seen some intergenerational social mobility, mostly through government reservation schemes in education and employment (Pais Citation2004). Of course, there are numerous other jatis and tribes in and around the city, but rather than attempting to create an exhaustive list, it is more pertinent to note that despite changes, jati remains an important part of everyday urban life in Mangaluru. As Kudva's ongoing research into jati and Mangaluru reveals, caste is written into mobility (Citation2015) and labour markets (Citation2013), and, whilst malleable, ‘patterns of constructed difference that reinscribe inequality and underscore lost opportunities … lie at the heart of how the region and the city are generated and thrive’ (Kudva Citation2015, 149).

With the various layers of jati, linguistic community and state formations in mind, in this article I argue that Mangaluru’s cityness is characterised by a pervading presence of smallness found in practices at various scales that speak to (1) the city's niche positioning as a port or education hub; (2) that indicate it lacks a certain urbanity in comparison to larger cities; and (3) that highlight its dense intimacy of relations engendered through proximity. Prior to this, I will first argue that despite smaller cities in India being ‘forgotten’ by both central state policies and academics, they remain important sites for understanding contemporary urbanity.

The twice forgotten city

‘But why did you come to Mangalore? You should have gone to Bangalore if you wanted to research urbanization.’

Lecturer at a local college

Smaller cities have, in part, been side-lined in central state policies. Alongside the neoliberal economic reforms of the last twenty years there has been significant decentralization of power to urban centres, but such decentralization has not always come with the means to substantively influence local development trajectories (Sharma Citation2012). Moreover, the central state has both decreased its level of intervention regarding the reduction of unevenness, and promoted selected metropolitan regions for investment, leaving the sub-national states to compete to capture resources (Chakravorty Citation2000). This shift is reflected in the elitist discourses and practices of urban planning, in which the bigger cities and their elite spaces of consumption are proclaimed as the ‘champions of urbanity’ and the pre-reform attempts at redistribution are forgotten, resulting in a ‘rescaling of the ‘urban’ imagery and … [a] redundancy of smaller cities and towns in the urban planning agenda’ (Banerjee-Guha Citation2013, 26–27). The renewed primacy given to larger cities can be clearly seen in the reorganization of central state funding allocations, leading to ‘a prevailing viewpoint that smaller urban settlements are officially neglected and disadvantaged areas’ (Shaw Citation2013, 50). For instance, the Integrated Development of Small & Medium Towns (IDSMT) program, which was initiated in 1979–80, was subsumed into the much more limited Urban Infrastructure Development Scheme for Small and Medium Towns (UIDSSMT) in 2005 as part of the flagship Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JnNURM), a massive funding program aimed at larger cities and state capitals (Shaw Citation2013, 50).Footnote3

In spite of smaller cities relegation in central state policy priorities, there is a strong policy case for understanding and harnessing the ‘economic dynamism of middle India’ (Harriss-White Citation2016). Dated, yet nevertheless illuminating, statistical analyses from the National Sample Survey (NSS) revealed that smaller cities evidenced proportionally higher rates of poverty than larger cities in the years 1987–2000 (Kundu and Sarangi Citation2005). However, the same set of data also shows that poverty has come down faster, purchasing power is greater and inequalities less severe in smaller and medium towns (Himanshu Citation2006).Footnote4 As Harriss-White (Citation2016) notes, economists who have hailed metros as the driver of India's remarkable economic growth, are perplexed that GDP has accelerated as metro growth has slowed. In turn, she argues that it is the unacknowledged and often disparaged informal economy in India's smaller cities and towns that is one of the drivers of this growth.

In spite of this, research into smaller cities—both from state actors and from academic scholars—has been significantly lacking in comparison to the attention given to larger cities. We should not overstate the size of the lacuna however. There are pockets of literature that, whilst not always explicitly dealing with questions of city size, nevertheless provide fascinating insights into smaller cities—namely some of the early anthropology in newly independent India; development studies in the 1970s; and isolated texts/edited collections associated with the upturn of interest in urban India in the last decades.

Vidyarthi (Citation1978) argues in his review of urban anthropology in India that three types of urban studies have emerged since independence—firstly, those driven by practical government concerns over population increase, housing, employment etc.; secondly, those funded by UNESCO's research into industrialisation in South Asia; and thirdly, those inspired by the Chicago School's cultural approach to urban life. It is from within this last group that a number of studies on smaller cities arose that reveal such places as key sites for exploring the interplay of ‘tradition’ and ‘modernity’. This includes Vidyarthi's (Citation1961) own work on the north Indian ritual centre, Gaya, and the interplay of different types of tradition, and Desai's (Citation1965) study on different types of ‘jointness’ within joint families in the town of Mahuva exploring how migration, not long-term urban living, dissolves jointness. Most interestingly for our case is Chekki's (Citation1974) study of Dharwad (now one of the twin cities of Hubli-Dharwad) in northern Karnataka, which explores whether urbanization in ‘developing nations’ followed a similar trajectory as in the West. He analysed this through the prism of kinship relations among the rural-orientated Lingayats jati, who lay stress on hard work, individual achievement and gender equality, and the Brahmins, whose focus on education and developing a profession opened up more opportunities with ongoing urbanization.

The second group of relevant literature emerged from the dashed hopes of development in the years following decolonisation. In the 1970s, smaller cities were given much international attention across what was then termed the ‘Third World’, with many governments in ‘developing countries’ placing their hope in smaller urban centres as they became dismayed by growing rural-urban economic polarisation and the failure of economic polices built around large-scale industries in select centres. Spurred on by development theorists (e.g. Rondinelli Citation1983), governments in various countries actively sought to develop small cities as means of balancing out unevenly developed regions, bringing about rural development in their hinterlands, and offering an alternative to rural-urban migration to larger cities. It was also argued that smaller urban centres might offer the benefits of economic development whilst maintaining a local sense of identity, thus avoiding the anonymity of the ‘ungovernable’ Third World metropolises (Dix Citation1986). However, this hope for smaller urban places was soon shown to be naïve and often based on unfounded and unresearched assumptions (Southall Citation1988), with one of the harshest critics noting that, ‘[s]mall cities … constitute, in a very real sense, parasitic islands of privilege in a sea of rural poverty and contribute little to the development of their respective hinterlands’ (Schatzberg Citation1979, 186).

Such dashed hopes have further resonance in India, as they chime with the creation of new towns conceived in the first decade of independence. There was an optimism surrounding the planned new towns (see: Koenigsberger Citation1952) and, as Srirupa Roy details (Citation2007, 133–56), these ‘cities of hope’ were promoted as ‘new places’ lived in by ‘new types of people’—the ideal ‘producer patriots’ of the new nation. Roy links these new towns into wider post-colonial state practices of ‘de-centring’—creating and celebrating new, previously insignificant, elsewheres—dream-worlds of the new nation-state that sat in contrast to the undeveloped, backwards country around it. However, by the 1970s these same towns had become sites of residential segregation, labour unrest, crime, corruption and communal riots; it was argued that they had seen too rapid and badly implemented planning, and were thus held up as exemplars of the failure of the nation building project. Outside these new places, smaller cities and towns grew in the decades following independence round pockets of industrial development, in urban corridors or serving rural areas (Heitzman Citation2008).

The third useful collection of studies comes from the recent upturn in urban studies in India, much of which utilizes a spatially sensitive approach. This has for the most part mirrored urban studies in and of the West in focussing on larger cities. The important insights gained from utilising approaches that attempt to understand how (often global) capital flows reorganize urban spaces need not be limited to the usual suspects however, since smaller city urbanisation is not totally dependent upon its relationships with the closest metropolises (Denis, Mukhopadhyay, and Zérah Citation2012). For example, spatial transformation in smaller Indian cities is in part being driven by internal actors, such as local entrepreneurs buying up land and thus pushing urban expansion (Raman Citation2014).

Identity characteristics such as class, jati, community and so on flow into the spaces and times of these smaller cities, possibly in a more pronounced or clearly delineated way than in larger cities. Upwardly mobile jatis in ‘provincial’ cities can reconfigure city spaces, for example by relocating industrial units to their part of town in a way that consolidates jati and neighbourhood affinities (De Neve Citation2006). Indeed, jati, occupation and community clustering is common in smaller cities (Harriss-White Citation2016), including Mangaluru (Kudva Citation2013). This is not to suggest, however, that smaller cities are necessarily less diverse overall; many smaller cities, especially those located at cultural/regional borderlands, exhibit immense diversity (Hasan Citation2011), with multi-ethnic diversity and struggles coming to shape the very understanding of such cities (McDuie-Ra Citation2014). The potential growth of smaller cities in part dovetails with the dream of smart cities. The smart city craze is a global one, yet the newly elected central government's promise of 100 smart cities in India seems unmatched in scale and ambition (Datta Citation2015). Mangaluru was selected for smart city funding during this article’s review process.

The dream of becoming a smart city, the side-lining of smaller cities in policy frameworks, the perceived failure of ‘new towns’ to help drive development, the claim that smaller cities might serve as lens to understand changes in ‘traditional’ structures and the pronounced presence of group characteristics in smaller cities all speak, in different ways, to how the city is imagined by its inhabitants and those who reside elsewhere, to how it is positioned in local, regional, national and global hierarchies and to how everyday rhythms within and surrounding the city are affected by city size. It is to this that I know turn.

Niche positions, relative lack and dense intimacy

‘War, storm and flood have each played their raucous interludes and ruffled the otherwise calm current of commerce that has flown with our twin rivers from the sources of time itself.’

T.W Venn, Mangalore (Citation1945, 128)

‘How is Mangalore educated? The obvious answer is “Really fine.” The accolades and encomiums every visitor offers to its citizens speaks of the educated progress achieved by its people.’

M Rajiva, “How is Mangalore Educated?” (Citation1958, 115)

‘At that time I heard loud noises downstairs. The girls were screaming in confusion. I came outside. All of them were hitting the girls.’

Birthday party attendee, quoted in the Fact Finding Report produced by the Forum Against Atrocities on Women (Citation2012, 2)

In this section, through a dialogue with selected works from both ‘small city’ and ‘non-western’ urban studies, I will argue that smaller cities in the global South are (1) pushed and pulled into niche positions, usually by actors working at different scales; (2) often framed, internally and externally, as having a relative lack of urbanity in comparison to larger and/or Western cities; and (3) characterised by a feeling of dense intimacy. However, undercutting and destabilising these categorisations, I will show through a historicising and contextualizing of Mangaluru's smallness how such niche positioning is often exceeded by local processes that can have very different structuring logics, some of which are unrelated to dominant positionings; relative lack is ironically embraced by those acutely aware of life in other cities, local insecurities and regional pride; and the dense intimacy of relations stretches beyond the frames usually used to conceptualise the city.

Mangaluru’s niche positioning is, in part, the work of imagination. Urban imagination is both individual and collective (Cinar and Bender Citation2007), as well as being fractured internally along jati, religious community, gender and age lines. For instance parts of Indian cities are sometimes imagined as ‘dangerous for women’ (Phadke Citation2013) or as being strongly associated with a certain jati (Kudva Citation2013, 2015). Moreover, the city is imagined in relation to wider society, an imagining that positions the city as, for example, part of a colonial regime, within a large empire, or as an important (or unimportant) city of the nation (King Citation2007).

In such ways, cities are imaginatively positioned vis-à-vis other places. Accordingly, in terms of both inter-city and rural-urban relations it is useful to think about a place's ‘position in relational space/time’, how the horizontal and vertical relational inequalities between different places within shifting global, regional and local hierarchies affect future prospects (Sheppard Citation2002). Imagination is key to this positioning because although the governance of urban places is to some degree structured materially through capitalistic urbanization, certain economic imaginaries bring about particular developmental trajectories (Lorentzen and Van Heur Citation2012). There is a co-development of both material and discursive processes in the joint modification of social relations, with both the ungraspable, messy sum of economic relations and the smooth, coherent narrative that develops around them important in assigning positions and structures of governance that institutionally regulate these positions within the global political economy (Van Heur Citation2012).

Smaller cities are usually imagined as fulfilling niche functions by policy makers, politicians and planners, whilst bigger cities are more often imagined as agglomerations, essentially expanding the horizons of possibility based on size (Van Heur Citation2012). Finding a city's niche is not easy and is often marked by failure. As such, smaller cities (like other cities) rely on the careful creation or maintenance of certain types of images about themselves. For instance, a small town in America can become a ‘temp-town’, living almost exclusively off a biannual furniture market that has both produced local wealth and insecurity as bigger cities attempt to draw their business (Schlichtman Citation2006); smaller cities in Europe attempt re-branding as ‘survival strategies’ (Allingham Citation2009); smaller former industrial cities in the UK embark on (failed) endeavours of ‘cultural regeneration’ (Evans and Foord Citation2006); and, more successfully, a city like Weimar manages to keep itself looming large in the German public imagination through cultural activities (Eckardt Citation2006; ).

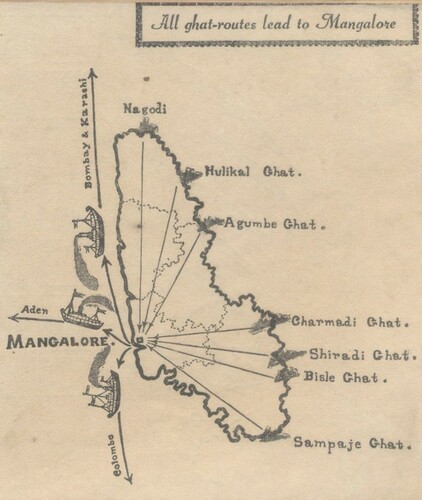

Figure 2 Mangalore’s Connections. Published in ‘Mangalore: A Souvenir’ complied for the Syndicate Bank. 1958.

Currently, especially at the federal and national level, Mangaluru is imagined as a seaport, whose wide hinterland includes heavy industry in its immediate vicinity. Of course, such a positioning was not picked out of thin air. Sea-links have long been at the core of the city's positioning in relation to the regimes within which Mangaluru has been enveloped. The Alupu dynasty, who ruled Tulu Nadu from the second to the fourteenth century—though subservient to the larger Kadambas, Chalukyas, Rashtrakutas, Hoysalas and Vijayanagara Rayas at various times—used Mangalore as a key port, and at a time made it their capital (Kamath Citation1980). Accordingly, in spite of its size, the city was known among traders in the Middle East and Europe for thousands of years (Ghosh Citation1992; N. E. Rao Citation2006; Lambourn Citation2008), and was an important site of struggle between the Kingdom of Mysore and the British.

Once the city was transferred to direct British rule under the Madras Presidency, after the defeat of Tipu Sultan in 1799, the port’s regional importance was diminished in line with a trend for infrastructural neglect in the city (Rai Citation2003). Indeed, despite colonial claims that their rule brought prosperity and peace (Rao Citation2003a), the reality was quite different, with rule marked at first by series of revolts (Rao Citation2003b) and then, once the region was secure, developmental negligence. As such, although there were calls to improve the port and other infrastructures, the city and its surroundings witnessed very little industrialization or development during colonial rule, as the British believed that, due to the wet climate and fertile land, revenue from agriculture was more profitable (Fernandes Citation2006).

With independence, in 1947, came the desire for the sort of development that was denied during colonialism to smaller cities and towns, and this desire for development remains strong. Robinson (Citation2002, 540) has rightly critiqued of developmentalist approaches to cities in the global south, which she argues ‘builds towards a vision of all poor cities as infrastructurally poor and economically stagnant yet (perversely?) expanding in size’. She suggests that developmentalism is so singular in its logic that it fails to consider how other economic processes, including the informal local or translocal ties that make up much of the economic activity in a city like Mangalore, might inform the possibilities for different futures within the context of desire for improvement. As such, to say that there was, and remains, a strong desire for ‘development’ is not to suggest other processes do not inform Mangalore’s cityness, but rather that the logic of development, in both its prior ‘socialist’ nation-state centred and recently market-led city-centred modes, remains crucially important for the way smaller cities are positioned in India; actors at higher scales, and many locals, desperately want to overcome their smaller, poorer city’s supposed ‘lack’ and celebrate what they consider to be signs of such progress.

Locally, arguably the most important realisation of this was the construction of the all-weather New Mangalore Port, which allowed all year-round trade (something restricted in the natural harbour of the old port due to the heavy monsoon). Inaugurated by Indira Gandhi in 1975 the port has positioned Mangaluru's industrial niche with a petrochemical focus in both federal Karnataka state’s and the central state's imagination. It was hoped by the central state that building a new port would help even out the unevenness of colonial trade and urbanization, which was centred around a handful of coastal metropolises (see: Heitzman Citation2008). Tied up with industrialisation from its inception, even opening itself to limited traffic a year early to bring in equipment for the state backed Mangalore Chemicals and Fertilisers, a large proportion of the district's industrial activity is also concentrated close to the port on the road to Udupi and forms part of an envisioned corridor of industrial development stretching up the coast (Government of Karnataka Citation2009; Bhatta Citation2013). The establishment of the highly controversial Mangalore Special Economic Zone (MSEZ) in 2005—the largest of seven formally approved Special Economic Zones in Dakshina Kannada district—furthered industrialization around the port (Cook, Bhatta, and Dinker Citation2013; Mody Citation2014). Backed by a nexus of state and private interests at various scales, MSEZ's formation is in line with such paradigmatic reform-era developments in Indian cities that involve federal state actors more heavily than those operating at the city government level (c.f. Kennedy Citation2013).

However, such a singular positioning is exceeded and destabilised by practices and processes that do not necessarily follow similar logics, and the workings of dense relations that stretch beyond what is usually imagined as the city. For instance, land in the cultural region of Tulu Nadu, of which Mangalore is the largest city, is inhabited by bhutas—spirits or divine beings including cultural heroes, animal spirits, ghosts or anthropomorphic deities, who reside and are worshipped in a number of places including trees, stones and shrines, and are usually tied to a geographic area such as the magane (domain), seeme (region), village, guttu (manor) or family (Gowda Citation2005). During an annual worship (kola or nema) mediums possess the bhutas and sing of paddanas (oral narratives) that detail the history and deeds of the spirits. In doing so they bring ways of knowing and being in the city into dialogue with newer notions of what land is or could be. For example, the bhuta who lives on one piece of land that was notified to be taken for MSEZ refuses to leave, communicating their decision during the kola, resulting in a prolonged battle over the land’s future (Cook, Bhatta, and Dinker Citation2013). Similarly, the sandy peninsular that juts out into the sea to form Mangaluru’s harbour undergoes change brought about biophysical as well as human forces, with the spit’s co-constitution by socio-natural processes allowing both elites and fisherfolk opportunities to forge futures on the land (Kadfak and Oskarsson Citation2017). No one logic of the city completely consumes the other, but rather they exist sometimes independent, sometimes in closer relation, to one another.

It has been argued, in specific relation to the region surrounding Mangalore, that we must examine the relative autonomy of different logics that drive urban change, rather than subsuming all processes under the linearity of capitalist modernity (see: Benjamin Citation2017). This call for a ‘subaltern’ understanding of urbanisation (Denis and Zérah Citation2017), must not lead to a rejection of structuring linear processes however. Different processes exist, and whilst some remain autonomous and non-linear, others interact with linear global processes linked to historical periods of capitalism.

The relationships between different logics of change can also be found in the region’s reputation as an ‘education hub’, with the districts of Dakshina Kannada and Udupi gaining a repute for education above what one would expect from a ‘provincial’ part of the country. Commission agents (who work to bring in students to colleges) can bring potential students from as far as the northern state of Gujarat on the promise of securing them a seat at ‘a college in Mangalore’ and, when I spoke to such students, a number reported that they knew just the name ‘Mangalore’ and not the college itself before arriving in the city. The mushrooming of private colleges in the region follows in the footsteps of the relatively autonomous jati-delineated long-standing business model of education in the district, which in turn dovetailed with the relatively early move in Karnataka towards privately run colleges, even before general policies of ‘liberalisation’ and the Supreme Court Ruling in 1993 that granted legitimacy to private higher education institutes (Agarwal Citation2009; Chakrabarti Citation2010), and that in turn speaks to a global shift towards the privatisation of education.

The history of how jati-delineated colleges came to fill the region, also speaks to how identity is closely marked in smaller cities like Mangaluru. The pioneer for private colleges in the region was local doctor, banker and educationalist TMA Pai, from the Konkani speaking Gowda Saraswat Brahmin community, who set up the Kasturba Medical College (later Manipal University) north of Mangalore in 1953—the first fee-paying self-financing medical college in India. The institution managed to avoid the then existing ban on admission fees by claiming minority status privileges granted by the constitution, arguing that Konkani speakers were a linguistic minority. Though there were some suggestions that they were motivated by the lack of opportunities for Brahmin students to attend medical colleges (Kaul Citation1993) (at the time the district was part of the Madras Presidency and there was a strong anti-Brahmin movement especially around university seats), the linguistic community angle was, according to a former Vice Chancellor I spoke with, just to bypass government rules. There are now numerous colleges in the district with minority status tags, some of which, such as the AJ Institute of Medical Science, utilising the peculiar situation that the most widely spoken local language, Tulu, is a minority language in the mostly Kannada speaking state of Karnataka. These different colleges are not exclusively for the different groups however, and many of them are highly mixed, though there is higher representation of certain groups in certain colleges partly due to (changing) rules around the reservation of places. This claim notwithstanding, more generally it can be said that jati organisations have been able to use private colleges to strengthen their economic, social and political base in Karnataka through private education institutes (Kaul Citation1993).

Such tightness of relations can be observed among the upper strata of society in smaller cities. For instance, in Indian cities, local elites can reproduce and consolidate their position in smaller urban settings by assigning themselves important public positions or residential places in the city (Sharma Citation2003), allowing them a greater range of possibilities to influence the local administrative and political offices. As research from outside India has shown, industrial elites in smaller cities, whilst primarily concerning themselves with advancing policies for their local capital investments, also become involved in parochial politics in ways that go beyond quests for immediate returns (Adamson Citation2008), with ‘social issues’ spilling over into spheres of city life that affect them more directly (Buse Citation2008). However, in well-connected port cities like Mangaluru (see ), tensions between horizontally connected emerging mercantile elites and vertically rooted local traditional elites can keep commonality of elite interest unstable (c.f. Morillo Citation2008).

The dense, jati-marked relationships of the city can also be felt amongst the interactions between the city’s youth. There are a growing number of pubs and bars in the city, but some local younger people, especially women, choose to stay away, not only because they are worried about their ‘reputation’—which does not take long to be muddied in a smaller city—but also about the so-called ‘moral policemen': vigilantes who frequently and brutally act in and around Mangaluru. Acts include: the famous ‘pub attack’ where a group of women who had met in a city centre pub were beaten; an attack on a Muslim boy talking to a Hindu girl at a juice bar; the stoning of a bus full of students from different religions who were going on a trip together; harassment of Muslim owned cafés; and, enforcing parties’ advertised finishing times. With the advent of local WhatsApp groups and the ubiquity for phones with cameras, the widespread shaming of young people found doing ‘immoral’ practices can take just a few minutes. Of course, in spite of the claim of vigilantes that they break up ‘rave parties’ with drugs, most youth will claim rather that the city lacks the sort of excitement that can be found in metropolises. Indeed, especially those who work for outsourcing or IT companies often complain about the limited possibilities for a social life in the city.

As such smallness can be felt in the rhythmic patterns of everyday life, in the routines and vernacular concepts of the quotidian that are engendered by the tight proximity of people and places. For example, being from a smaller city can produce a heightened sense of awareness for and of place among young people, as smallness mixes with a sense of ‘living on the margins’ as teenagers mark out territories in the city as part of their everyday lives (Waitt, Hewitt, and Kraly Citation2006), or everyday gay life in a smaller city can often be imagined as an inauthentic copy of life in ‘gay mecca’ metropolises (Myrdahl Citation2013). Such irony laced pride is maybe most starkly illuminated in some of the internet memes produced by locals, that circulate on social media (see ).

Sizing the city: moving beyond the beyond

Sometimes in moments of day dreaming I anthropomorphize the city, wondering if Mangaluru's smallness engender actions that befit a much bigger city—a sort of over compensation for its size or desire to punch above its weight. For instance, there is a proposal to build a city changing six-lane riverside ring road called the Mangala Corniche, which mimics Mumbai's famous Marine Drive. Then there is the desire to build more and more shopping malls which, though I could get no hard data, seemed to only be used for their supermarkets, food courts and cinemas, with many of the expensive shops sitting empty. There are also plans underfoot to build an 18-hole golf course on the peninsular that forms Mangaluru's natural harbour (Kadfak Citation2018), which will be the city's second golf course if completed. When I think through such acts, I see a small city with a pining for largeness.

Such daydreaming is of course to collapse the multiple types of actors working at different scales and with different intentions into one anthropomorphic entity, but such thinking also points towards how the historical and contextual difference formed through centuries of colonial and imperial rule intersect with the universalizing inferiority-ridden ‘variations on a form’ thinking that pervades in and about the city. Pushed into a niche function as a port with surrounding heavy industry by actors at higher spatial scales, local elites imagine a more diverse city with money to be made from colleges and shopping malls which, even if not full yet, they hope will fill up in the future.

After writing the first draft of this article I was invited by some local activists in Mangaluru to give a talk about my work. After giving them a very similar argument to what I laid out above, I finished by saying that if they wanted to change Mangaluru's trajectory—and they all did—then part of their job is to imagine a future for their city that did not ape London or New York, but that built on Mangaluru's uniqueness whilst avoiding being labelled as ‘anti-development’ (as often activists are in India). One activist stood up and said,

‘I buy your argument to a certain point … but it is not New York or London people here dream of, but Dubai and Singapore. Cities that arose from nothing, from the desert, in just a short space of time. That is what people believe they can turn Mangalore into.’

His comment is a good reminder that the West (or global North) is not the centre of everyone's imagination. Whilst smaller cities are often framed locally as ‘variations of a form’, the starting form is not the same form for everyone. It is not a clear model against which smaller southern cities like Mangaluru measure themselves, but rather a shifting incoherent idea that nevertheless remains powerful. The imagined modern city is a commonly understood (if fuzzy) idea for most of those I spoke with, not because there is one particular city common across all imaginations, but rather because common traits stretch across such cities: one of the most important expressions of which is size.

Such an argument has important implications for how we conceptualise the urban. I argue that in regards to both locals’ reference points of city comparison and the interconnectedness of urban imaginaries, there is no ‘beyond the west’ nor a ‘beyond the metropolis’. There is a ‘burden of difference’ that lies in the conceptual framing of ‘beyond’, a framing that suggests a city is both outside and yet tethered to the West (Chattopadhyay Citation2012) or larger cities. Moreover, the endless quest for difference or pure autonomous logics has stopped urban scholars from making arguments about the city aside from that they are ‘beyond’ whatever monolithic framework they set themselves against. Research in smaller cities in the global south teach us that such places are within a world of cities, and that comparisons with larger and Western cities are unavoidable, but that this does exclude fresh possibilities for understanding urbanisms, nor from making claims about what such places are. As such, I have argued that smaller cities in the global south are placed into niche positions, are framed as lacking aspects of urbanity and exhibit a dense intimacy. I further showed how the city is characterised both by such framings and the various processes, logics and relationships that exceed and thus remould them.

Mangaluru is made and unmade by histories and contexts that are refracted through millennial-old, colonial and post-colonial prisms—processes that predate and originate outside the confines of contemporary global urbanization and yet, when positioned by the city's relational relative smallness, are framed as variations of a model of what a city could and should be. If Indira Gandhi flew into Mangaluru today she would see something more like what she considered to be a city—skyscrapers, industry, pollution—but although the city is no longer hidden beneath the trees, she might, with the top-down view of a plan-making politician, see the city as merely a smaller version of Mumbai, Chennai or Dubai. Hopefully more urban scholars will begin to look below the tree line and continue to explore ways in which smaller cities like Mangaluru—framed as variations of a form, yet with particular contexts and histories—change our thinking about what our cities are and could be.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ian M. Cook

Ian M. Cook is an anthropologist and Research Fellow at the Center for Media, Data and Society at the Central European University, Budapest, Hungary.

Notes

1 With each census in India there are a host of new 'Census Towns' declared: these are settlements that have grown to have a population of more than 5000 with a density of 400 people per square kilometre and with 75 percent of the male workforce not employed in agriculture. To be declared a Census Town means that such settlements have not yet been declared a Statuary Town, i.e. a town with the accompanying relevant municipal structures. In the 2011 in total there were 7,935 towns or cities identified in India, 4,041 of these were Statutory Towns, 3,894 of these Census Towns.

2 Dakshina Kannada’s name derives from the colonial name for the region, Canara, a corruption of Kannada, the name assigned to the coastal region of modern day Karnataka by European traders. Once Canara came completely under British rule following the defeat of Tippu Sultan, it was attached to the Madras Presidency. However, Canara was split into north Canara and south Canara in 1862. North and South Canara were unsurprisingly signalled out for a name change quite early after independence, but rather than give new names that reflected how the regions had been locally known before the colonial period, they were instead transliterated and de-corrupted into Dakshina Kannada and Uttara Kannada (South and North respectively). Many businesses however, including the famous Canara Bank, keep the colonial-era name. In 1997 Dakshina (south) Kannada was bifurcated, with the northern part of the district renamed Udupi, after the largest town there.

3 The JnNURM launched in 2001 promised Rs. 5,00,000 million from 2005–12 for infrastructure and improved urban governance in the 35 cities with more than a million inhabitants, along with all state capitals and other cities important for national development. The UIDSST is only for civic projects, not economic uplifting, and has mostly been used for water supply and has disproportionally gone to the better of states (Shaw Citation2013).

4 These two analyses are based on the NSS that gathered data categorised along settlement size – large towns (more than a million), medium towns (50,000 – million), small towns (less than 50,000).

References

- Adamson, M. R. 2008. “Oil Booms and Boosterism Local Elites, Outside Companies, and the Growth of Ventura, California.” Journal of Urban History 35 (1): 150–177. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144208321873

- Agarwal, P. 2009. Indian Higher Education Envisioning the Future. New Delhi and Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Allingham, P. 2009. “Experiential Strategies for the Survival of Small Cities in Europe.” European Planning Studies 17 (6): 905–923. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09654310902794042

- Banerjee-Guha, S. 2013. “Small Cities and Towns in Contemporary Urban Theory, Policy and Praxis.” In Small Cities and Towns in a Global Era: Emerging Changes and Perspectives, edited by R. N. Sharma, and R. S. Sandhu, 18–35. Jaipur: Rawat Publications.

- Bell, D., and M. Jayne. 2006. Small Cities: Urban Experience Beyond the Metropolis. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bell, D., and M. Jayne. 2009. “Small Cities? Towards a Research Agenda.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 33 (3): 683–699. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2009.00886.x

- Benjamin, S. 2017. “Multilayered Urbanisation of the South Canara Territory.” In Subaltern Urbanisation in India, edited by E. Denis, and M.-H. Zérah, 199–233. New Delhi: Exploring Urban Change in South Asia. Springer.

- Bhatta, R. 2013. “Tradeoffs Between Land Rights and Economic Growth A Case Study of Coastal Karnataka.” Journal of Land and Rural Studies 1 (2): 229–243. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2321024913513387

- Brenner, N. 2013. “Theses on Urbanization.” Public Culture 25 (1 69): 85–114. doi: https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-1890477

- Brenner, N., and C. Schmid. 2015. “Towards a New Epistemology of the Urban?” City 19 (2–3): 151–182. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1014712

- Buse, D. K. 2008. “Encountering and Overcoming Small-City Problems Bremen in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of Urban History 35 (1): 39–52. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0096144208321875

- Chakrabarti, A. 2010. “‘Privatising Social Opportunity: Trends and Implications for Higher Education in India’.” In Democracy, Development, and Decentralisation in India: Continuing Debates, edited by C. Sengupta, and S. Corbridge, 247–282. New Delhi and Abingdon: Routledge.

- Chakravorty, S. 2000. “How Does Structural Reform Affect Regional Development? Resolving Contradictory Theory with Evidence From India.” Economic Geography 76 (4): 367–394. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/144392

- Chattopadhyay, S. 2012. “Urbanism, Colonialism, and Subalternity’.” In Urban Theory Beyond the West: A World of Cities, edited by Tim Edensor, and Mark Jayne, 75–110. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Chekki, D. A. 1974. Modernization and Kin Network. Leiden: Brill.

- Cinar, A., and T. Bender. 2007. Urban Imaginaries Locating the Modern City. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Cook, I. M., R. Bhatta, and V. Dinker. 2013. “The Multiple Displacements of Mangalore Special Economic Zone.” Economic and Political Weekly 48 (33): 40–46.

- Datta, A. 2015. “New Urban Utopias of Postcolonial India ‘Entrepreneurial Urbanization’ in Dholera Smart City, Gujarat.” Dialogues in Human Geography 5 (1): 3–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820614565748

- De Neve, G. 2006. “Economic Liberalisation, Class Restructuring and Social Space in Provincial South India.” In The Meaning of the Local: Politics of Place in Urban India, edited by De Neve G., and H. Donner, 21–43. Abingdon: UCL Press.

- Denis, E., P. Mukhopadhyay, and M.-H. Zérah. 2012. “Subaltern Urbanisation in India.” Economic and Political Weekly 47 (30): 52–62.

- Denis, E., and M.-H. Zérah. 2017. Subaltern Urbanisation in India: An Introduction to the Dynamics of Ordinary Towns. New Delhi: Springer.

- Desai, I. P. 1965. Some Aspects Of Family in Mahuva: A Sociological Study of Jointness in a Small Town. London: Asia Publishing House.

- Dix, G. 1986. “Small Cities in the World System.” Habitat International 10 (1–2): 273–282. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-3975(86)90030-5

- Eckardt, F. 2006. “Urban Myth: The Symbolic Sizing of Weimar, Germany.” In Small Cities: Urban Experience Beyond the Metropolis, edited by D. Bell, and M. Jayne, 121–132. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Edensor, T., and M. Jayne. 2012. Urban Theory Beyond the West: A World of Cities. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Evans, G., and J. Foord. 2006. “Small Cities for a Small Country: Sustaining the Cultural Renaissance?” In Small Cities: Urban Experience Beyond the Metropolis, edited by D. Bell, and M. Jayne, 151–168. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Fernandes, D. 2006. The Tulu World in European Writings. Mangalagangothri: Mangalore University.

- Forum Against Atrocities on Women. 2012. ‘Fact Finding Report’. Mangalore.

- Ghosh, A. 1992. In an Antique Land. New Delhi and Bangalore: Ravi Dayal.

- Government of India. 2011. “Census of India 2011.” Bangalore: Directorate of Census Operations. http://www.census2011.co.in/census/city/451-mangalore.html.

- Government of Karnataka. 2009. Urban Development Policy for Karnataka Draft Report. Bangalore: Urban Development Department.

- Government of Karnataka. 2010. Karnataka at a Glance. Bangalore: Directorate of Economic and Statistics.

- Gowda, C. K. 2005. The Mask and the Message. Mangalagangothri: Madipu Prakashana.

- Harriss-White, B. 2016. “Introduction: The Economic Dynamism of Middle India.” In Middle India and Urban-Rural Development: Four Decades of Change, edited by B. Harriss-White, 1–28. New Delhi: Springer.

- Hasan, D. 2011. “Shillong: The (Un) Making of a North-East Indian City?” In Urban Navigations: Politics, Space and the City in South Asia, edited by J. S. Anjaria, and C. McFarlane, 93–118. New Delhi; New York: Routledge.

- Heitzman, J. 2008. The City in South Asia. London: Routledge.

- Himanshu. 2006. “Urban Poverty in India by Size Class of Towns: Level, Trends and Characteristics.” Conference paper, Mumbai: Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research.

- Kadfak, A. 2018. “Intermediary Politics in a Peri-Urban Village in Mangaluru, India.” Forum for Development Studies: 1–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/08039410.2018.1529700

- Kadfak, A., and P. Oskarsson. 2017. “The Shifting Sands of Land Governance in Peri-Urban Mangaluru, India: Fluctuating Land as an ‘Informality Machine’ Reinforcing Rapid Coastal Transformations.” Contemporary South Asia: 1–16.

- Kamath, S. U. 1980. A Concise History of Karnataka From Pre-Historic Times to the Present. Bangalore: Archana Prakashana.

- Kaul, R. 1993. Caste, Class, and Education: Politics of the Capitation Fee Phenomenon in Karnataka. New Delhi: Sage Publications.

- Kennedy, L. 2013. The Politics of Economic Restructuring in India: Economic Governance and State Spatial Rescaling. London: Routledge.

- King, A. D. 2007. “Boundaries, Networks, and Cities: Playing and Replaying Diasporas and Histories.” In Urban Imaginaries Locating the Modern City, edited by A. Cinar, and T. Bender, xi–xxvi. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Koenigsberger, O. H. 1952. “New Towns in India.” The Town Planning Review 23 (2): 95–132. doi: https://doi.org/10.3828/tpr.23.2.cpn33402758n8446

- Kudva, N. 2013. “Planning Mangalore: Garbage Collection in a Small Indian City.” In Contesting the Indian City, edited by G. Shatkin, 265–292. Chichester: John Wiley.

- Kudva, N. 2015. “Small Cities, Big Issues: Indian Cities in the Debates on Urban Poverty and Inequality.” In Cities and Inequalities in a Global and Neoliberal World, edited by F. Miraftab, 135–152. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kundu, A., and N. Sarangi. 2005. “Issue of Urban Exclusion.” Economic and Political Weekly 40 (33): 3642–3646.

- Lambourn, E. 2008. “India From Aden – Khutba and Muslim Urban Networks in Late Thirteenth-Century India.” In Secondary Cities and Urban Networking in the Indian Ocean Realm, c. 1400-1800, edited by K. R. Hall, 55–97. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Lorentzen, A., and B. Van Heur. 2012. Cultural Political Economy of Small Cities. Abingdon: Routledge.

- McDuie-Ra, D. 2014. “Ethnicity and Place in a ‘Disturbed City’: Ways of Belonging in Imphal, Manipur.” Asian Ethnicity 15 (3): 374–393. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14631369.2014.915488

- Mody, A. 2014. “The Primacy of the Local.” In Power, Policy, and Protest: The Politics of India’s Special Economic Zones, edited by R. Jenkins, L. Kennedy, and P. Mukhopadhyay, 203–238. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

- Morillo, S. 2008. “Autonomy and Subordination: The Cultural Dynamics of Small Cities.” In Secondary Cities and Urban Networking in the Indian Ocean Realm, c. 1400-1800, edited by K. R. Hall, 17–37. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Myrdahl, T. M. 2013. “Ordinary (Small) Cities and LGBQ Lives.” ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 12 (2): 279–304.

- Nair, J. 2011. “The “Composite” State and Its ‘Nation’: Karnataka’s Reunification Revisited.” Economic and Political Weekly 46 (47): 52–62.

- Pais, R. 2004. Scheduled Castes: A Study in Employment and Social Mobility. Mangalore: Mangala Publications.

- Phadke, S. 2013. “Unfriendly Bodies, Hostile Cities.” Economic and Political Weekly 48 (39): 50–59.

- Rai, M. 2003. “Urbanization of Mangalore: A Colonial Experience (1799-1947).” (Unpublished PhD Dissertation). Mangalore University, Mangalagangothri.

- Rajiva, M. 1958. “How Is Mangalore Educated?” In Mangalore: A Survey of the Place and Its People, edited by K. S. H. Bhat, 115–127. Mangalore: Canara Industrial & Banking Syndicate.

- Raman, B. 2014. “Patterns and Practices of Spatial Transformation in Non-Metros.” Economic and Political Weekly 49 (22): 46–54.

- Raman, B., M. Prasad-Aleyamma, R. De Bercegol, E. Denis, and M.-H. Zérah. 2015. “Selected Readings on Small Town Dynamics in India.” Working papers series no. 7; SUBURBIN Working papers series no. 2. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01139006/.

- Rao, S. B. 2003a. “Gazetteers in Colonial Subjectification.” In The Retrieved Acre: Nature and Culture in the World of the Tuluva, edited by S. B. Rao, and C. K. Gowda, 114–129. Mangalagangothri: Prasaranga, Mangalore University.

- Rao, S. B. 2003b. “South Kanara in the 19th Century.” In The Retrieved Acre: Nature and Culture in the World of the Tuluva, edited by S. B. Rao, and C. K. Gowda, 103–113. Mangalagangothri: Prasaranga, Mangalore University.

- Rao, N. E. 2006. Craft Production and Trade in South Kanara: AD 1000-1763. New Delhi: Gyan Books.

- Rao, S. B. 2006. Ordinary Cities: Between Modernity and Development. London and New York: Routledge.

- Rao, S. B. 2010. Bunts in History and Culture. Udupi: Rashtrakavi Govind Pai Samshodhana Kendra.

- Robinson, J. 2002. “Global and World Cities: A View From off the Map.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 26 (3): 531–554. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00397

- Robinson, J., and A. Roy. 2015. “Global Urbanisms and the Nature of Urban Theory.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 40 (1): 181–186.

- Rondinelli, D. A. 1983. “Towns and Small Cities in Developing Countries.” Geographical Review 73 (4): 379–395. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/214328

- Roy, S. 2007. Beyond Belief: India and the Politics of Postcolonial Nationalism. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Roy, A. 2015. “‘Who’s Afraid of Postcolonial Theory?” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40 (1): 200–209. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12274

- Schatzberg, M. G. 1979. “Islands of Privilege: Small Cities in Africa and the Dynamics of Class Formation.” Urban Anthropology 8 (2): 173–190.

- Schlichtman, J. J. 2006. “Temp Town: Temporality as a Place Promotion Niche in the World’s Furniture Capital.” In Small Cities: Urban Experience Beyond the Metropolis, edited by D. Bell, and M. Jayne, 33–44. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Sharma, K. L. 2003. “The Social Organisation of Urban Space: A Case Study of Chanderi, a Small Town in Central India.” Contributions to Indian Sociology 37 (3): 405–427. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/006996670303700301

- Sharma, K. 2012. “‘Rejuvenating India’s Small Towns’.” Economic and Political Weekly 47 (30): 63–68.

- Shatkin, G. 2014. “Contesting the Indian City: Global Visions and the Politics of the Local.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38 (1): 1–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12039

- Shaw, A. 2013. “‘Emerging Perspectives on Small Cities and Towns’.” In Small Cities and Towns in Global Era: Emerging Changes and Perspectives, edited by R. N. Sharma, and R. S. Sandhu, 36–53. Jaipur: Rawat Publications.

- Sheppard, E. 2002. “The Spaces and Times of Globalization: Place, Scale, Networks, and Positionality.” Economic Geography 78 (3): 307–330. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/4140812

- Sheppard, E., H. Leitner, and A. Maringanti. 2013. “Provincializing Global Urbanism: A Manifesto.” Urban Geography 34 (7): 893–900. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2013.807977

- Sircar, S. 2017. “‘Census Towns’ in India and What It Means to Be ‘Urban’: Competing Epistemologies and Potential New Approaches.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 38 (2): 229–244. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/sjtg.12193

- Southall, A. 1988. “Small Urban Centers in Rural Development: What Else Is Development Other Than Helping Your Own Home Town?” African Studies Review 31 (3): 1–15. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/524068

- Van Heur, B. 2012. “Small Cities and the Sociospatial Specificity of Economic Development: A Heuristic Approach.” In Cultural Political Economy of Small Cities, edited by A. Lorentzen, and B. Van Heur, 17–30. London: Routledge.

- Venn, T. W. 1945. Mangalore. British Cochin: T.W. Venn.

- Vidyarthi, L. P. 1961. The Sacred Complex in Hindu Gaya. New York: Asia Publishing House.

- Vidyarthi, L. P. 1978. Rise of Anthropology in India. Vol. I and II. New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company.

- Waitt, G., T. Hewitt, and E. Kraly. 2006. “De-Centring Metropolitan Youth Identities: Boundaries, Difference and Sense of Place.” In Small Cities: Urban Experience Beyond the Metropolis, edited by D. Bell, and M. Jayne, 217–232. Abingdon: Routledge.