Abstract

Within policy and research debates on the smart city, the urban environment has become an arena of contestation. Claims that digitalisation will render the city more resource-efficient are countered by criticism of the tensions between smart and sustainability practices. Little attention has been paid, however, to the role of nature in digitally mediated urban environments. The flora, fauna and habitats of a city are a void in research and policy on digital urbanism. This paper provides one of the first conceptually grounded, empirical studies of ‘digital urban nature’ in practice. Taking the empirical example of Berlin, the paper demonstrates how a single city can spawn a rich variety of digital nature schemes, develops from this a typology to guide future research and analyses two schemes in depth to illustrate the aspirations and limitations of digital technologies targeting urban nature. The empirical findings are interpreted by bringing into dialogue pertinent strands of urban research: first, between smart environments and urban nature to explore ways of representing nature through digital technologies and, second, between digital and urban commons to interpret changes in the collective and individual use of urban nature. The paper reveals that digital platforms and apps are creating new ways of seeing and experiencing nature in the city, but often cling to conventional, anthropocentric notions of urban nature, with sometimes detrimental effects. More broadly, it suggests that exploring practices of digitalisation beyond the remit of conventional smart city policy can enrich scholarship on digitally mediated human-nature relations in the city.

Introduction

Visions and enactments of the smart city target the urban environment as a key beneficiary of digitalisation. Whether corporatist or municipal in origin, smart city strategies invariably promise significant reductions to ambient pollution, energy and resource use (Martin, Evans, and Karvonen Citation2018). Digital technologies are supposed to provide the critical data that will allow traffic to flow more freely, electrical appliances to operate more efficiently and air pollution to be monitored more effectively, at the same time producing a second, digital layer of the urban through data and their representation (Rabari and Storper Citation2015). Research at the interface of human geography and science and technology studies has challenged many of these claims, revealing some of the inherent tensions between smart city and sustainable city discourses or practices (Hollands Citation2008; Gabrys Citation2014; Luque-Ayala, McFarlane, and Marvin Citation2016). This work highlights, for instance, the environmental costs of the economic growth logic underpinning many smart city initiatives and the recruitment of citizens as providers of marketable data on resource use (Shelton and Lodato Citation2019; Martin, Evans, and Karvonen Citation2018). ‘Smart green’ or ‘eco-smart’ aspirations and activities have been subjected to critical appraisal for overestimating the potential for digital technologies to decouple consumption from development (Viitanen and Kingston Citation2014), for failing to question logics of growth (Martin, Evans, and Karvonen Citation2018) and for buying into neoliberal logics of competitiveness (Cardullo and Kitchen Citation2018).

What is largely absent in both policy and research discourses is urban ‘nature’, in the sense of the flora, fauna and habitats of a city. The smart city strategies designed by corporations and city authorities often ignore the ‘natural’ urban environment. The literature on digitally mediated urbanism has shown a similar lack of interest in how technologies are changing human relations with urban ‘nature’. It is as if the non-technical image of urban nature has rendered it unamenable to the high-tech, digitalised city. Smart environmentalism tends to focus on those components that can be technically measured and controlled, such as electricity consumption, air pollution and waste flows. Our paper counters this bias by exploring the relationship of ‘nature’, technologies and data through human use. It draws on recent empirical research on ‘the actual existing smart city’—i.e. enactments of digitalisation in urban practice—as elaborated in articles published in this journal (Hollands Citation2008; Shelton and Lodato Citation2019; Rose Citation2020). The paper positions itself within this body of research that is analysing how ‘smart’ is being interpreted and enacted in particular urban contexts (Luque-Ayala, McFarlane, and Marvin Citation2016; Karvonen, Cugurullo, and Caprotti Citation2019). This work has arisen out of the perceived need to subject some of the claims and counter-claims made of the smart city to grounded empirical scrutiny.

Urban nature is an ideal vehicle for broadening the debate on the digital city even further. The absence of nature in most smart city strategies, we argue, is not due to a lack of examples of urban nature being observed, monitored or managed through online databases, mobile apps and digital platforms. On the contrary, the city of Berlin alone boasts some 20 schemes to ‘digitalise’ urban nature, many of which have existed for years. Although the city is internationally renowned for urban ecology, its Smart City Strategy of 2015 made no reference whatsoever to urban nature (Voigt Citation2017). Understanding why non-human living organisms are peripheral to the smart urbanism discourse can reveal important new facets of myopia and exclusion surrounding the notion of ‘smartness’. Understanding how urban nature is being represented and used with the help of digital technologies can, at the same time, tell us more about the limitations—as well as opportunities—of such interactions, as currently practised.

The aim of the paper is to demonstrate the range of new digital forms of representing and using nature in cities, analyse what difference they are making to human relations with urban nature and explicate their broader significance for research on digitally mediated urbanism. Taking Berlin as an exemplar, the research is guided by three questions. First: what kinds of nature-oriented digital projects can be observed in Berlin? Here the interest lies in identifying and characterising the variety of schemes in the city in terms of the ‘natures’ targeted, technologies applied and users involved. Second: how far, and in what ways, are these projects generating new ways of understanding, representing, using and relating to urban nature? This question explores the degree to which digital technologies and their use are re-defining the relationship between nature, technology and humans. Third: in what ways can attention to urban nature enrich research on digital urbanism? Here the findings from the Berlin case are assessed in terms of how they challenge and advance existing work on the ‘smart’ city in general, and its environmental dimensions in particular.

The paper is structured around five sections. First, a conceptual framework is developed to study digital natures in the city, emerging from dialogues between two sets of relevant literatures. Then the case study of Berlin is presented, comprising an overview and typology of digitally mediated urban nature schemes and profiles of two selected for in-depth analysis. The following two analytical sections interpret the findings in terms of the conceptual framework. Their broader relevance for debates on the smart city is extrapolated in the conclusion.

Digital natures in smart cities

Notwithstanding its exploratory empirical thrust, the paper aspires to generate insight on how digital urban nature activities can be conceptualised with respect to ongoing debates in urban studies. In this section, two interfaces are explored. The first is between literatures on smart environments and on urban nature. This dialogue indicates ways of understanding and representing nature through digital technologies. The second interface is between literatures on digital commons and on urban commons. Here, the purpose is to reveal how technological devices might be expected to change ways of using and relating to urban nature.

Smartening urban nature: meaning and representation

The intersection between smart and sustainable urbanisms has attracted attention in recent research. Alongside critical work questioning the environmental impact and rhetoric of smart city initiatives (Martin, Evans, and Karvonen Citation2018), this field of inquiry commonly focuses on improving environmental protection and rendering metabolic flows more efficient (Yigitcanlar Citation2009). While Karvonen (Citation2011) was early in recognising that biotopes do not feature much in smart city programmes (and their critique), prime issues of concern have been the impact of smart technologies on resource flows, energy and resource efficiency (Viitanen and Kingston Citation2014) as well as ambient pollution (Gabrys Citation2014). In this regard, Derickson (Citation2018) perceives the smart city discourse as an expression of ‘ontologies of systemicity’, reflecting new thinking about how nature and societies are merged in discourses about the Anthropocene. In using the term ‘Anthropocene’ we are mindful of the severe criticism it has received for its universalising notion of the ‘anthropos’, while concealing multi-scalar power relations during capitalist development, colonialism and slavery (Davis et al. Citation2019; Yusoff Citation2019).

Research on urban political ecology looks back on a long tradition of questioning social power relations as well as nature and society as separate realms in urban studies (Heynen, Kaika, and Swyngedouw Citation2006; Brantz and Dümpelmann Citation2011; Gandy Citation2015; Wachsmuth Citation2016). Urban political ecologists generally embrace a holistic understanding of close interdependence between the social and ecological dimensions of urban nature (Gandy Citation2006, 71). From this perspective, nature—in its multiple, socially produced forms—is constitutive of the urban condition (Heynen, Kaika, and Swyngedouw Citation2006, 2–5) and central to the politics of everyday life in cities (Angelo and Wachsmuth Citation2015). Moreover, through human use and design cities have developed very distinctive forms of nature (Pincetl Citation2012). Nature is represented in varying ways that reflect human values, such as ‘useful nature’, ‘beautiful nature’ and ‘sensitive nature’ (Lossau and Winter Citation2011, 338–342). Emphasising the hybrid character of nature/society, consequently, problematises expectations of all-too-easy control over urban nature, as demonstrated in recent work on spontaneous vegetation in the ‘botanical city’ (Gandy and Jasper Citation2020).

The practice of environmental smart city initiatives—just as other ‘smart’ programmes—instead relies on the collation of data in control rooms or command centres making visible various flows and processes in real time (Kitchin, Lauriault, and McArdle Citation2015). Often built on knowledge from private technology firms, automated sensors as well as citizens may produce the data (Tironi and Sánchez Criado Citation2015). Luvisi and Lorenzi (Citation2014) have demonstrated how sensors used to monitor urban ecosystems can create new methods of visualising green infrastructure. However, inputs and information are often subjugated to an overall logic of control for optimising environmental flows and quality as well as reconfiguring practices of everyday life within the city (Gabrys Citation2014). Burton, Karvonen, and Caprotti (Citation2019) have observed how smart discourses may connect to grassroots notions of local circular economies and reducing resource use, so nature may be an entry into thinking differently about the role of human interaction in smart cities. To date, however, most research and practice is concerned with the technical potential for monitoring and controlling urban nature digitally.

Following the hybrid conceptions of nature as socially produced and impacting upon the everyday, it is important for us to overcome simplified notions of urban nature as an object of control. Instead, we want to unveil the various ways in which digital urban projects produce new meanings and representations of nature in the city. The first interface encourages us to ask, in particular, whether digital technologies enhance the hybridity of urban nature or merely reinforce popular understandings of nature in the city. In one of the few studies of digital urban nature, Ricci et al. (Citation2017) use social network analysis to reveal the symbolism people attach to objects of urban nature on social media, using Paris’ Urban Nature Initiative and its digital platform ‘Végétalisons Paris’ as an example. Sharma et al. (Citation2019) argue that citizens gathering data on the natural environment can develop new attachments to nature in their own gardens. While these examples point to various forms of seeing and sensing urban nature through digital technology, critical research on smart urban environments, discussed above, cautions us to consider whose urban natures are being represented through digital platforms, apps etc. (Graham and Zook Citation2013). Scholars are questioning ‘whose knowledges are being produced, by and for whom in deployments of and practices with the technology’ (Ash, Kitchin, and Leszczynski Citation2018, 28). To unpack issues of ownership and control surrounding digital urban nature, as expressed through its use, it is desirable to seek additional analytical purchase: through a dialogue between the literatures on digital and urban commons.

From digital commons to ‘commoning’ the city

The commons have gained traction as a novel way of understanding and transforming the production, use and governance of physical and digital resources. Simply put, commons can be defined as a collectively used resource, whose use is shaped by rules agreed by the community of its users. The classic work of institutional economist Elinor Ostrom (Citation1990) advocates the management of common pool resources being entrusted to local communities and polycentric governance structures. Recently, thinking about the commons has branched out and been enriched by two new fields: the commons in the digital sphere and the realm of urban commons.

In the digital realm, projects such as Wikipedia, Open Street Maps, Creative Commons licences and various other platforms have created a field of knowledge commons based on the principles of open access and community curation (Hess and Ostrom Citation2007). In a smart city context, the notion of ‘urban sharing’ implies new forms of organising and coordinating urban services and resources through digital technology, though such projects have been criticised for their commercial logic (Zvolska et al. Citation2019). ‘Citizen science’ approaches depict a form of collective mobilisation, whereby people are enrolled in gathering, storing and—to some extent—interpreting data in various fields enabled by ICT technologies (Wilson Citation2011; Skarlatidou et al. Citation2019). Critics, however, point out that the ‘illusion of the digital commons’ is all too readily embraced, with many using platforms without either deliberating on their rules or reflecting on issues of data ownership and usage (Ossewaarde and Reijers Citation2017). These critics call for models of ‘commons-based peer production’ to challenge ‘the extractive model of cognitive capitalism’ (Bauwens, Kostakis, and Pazaitis Citation2019) and for an ‘informational right to the city’ (Shaw and Graham Citation2017). A good example is the strategy to engage citizens and foster local democracy through digital platforms in Barcelona (Smith and Martín Citation2020).

This call from the digital sphere resonates with debates about the urban commons that often envisage a more radical perspective on urban futures (Harvey Citation2012). Scholars here highlight the process and practices of creating, or reclaiming, commonly used resources in diverse urban domains, ranging from neighbourhoods and public space (Radywyl and Biggs Citation2013) to urban energy systems (Becker, Naumann, and Moss Citation2017). Closer to our topic, work is emerging that explores how urban gardens and plants can create commons around community-based modes of land use and food provision (Eizenberg Citation2012; Colding et al. Citation2013; Scharf et al. Citation2019). These diverse examples share an emphasis on practices of ‘commoning’ and forming communities for producing, using and distributing resources—and urban space—set against tendencies of enclosure and privatisation (Harvey Citation2012). Here, grassroots approaches to urban commons are seen as alternatives to reliance on state regulation (Berlant Citation2016).

Linking the two fields of digital and urban commons, Cardullo (Citation2019) underlines the importance of stewardship in collective digital projects, differentiating between a sphere of collective action and a sphere of infrastructure and data security. Research on the halted Toronto Sidewalk Labs project run by Google’s owner Alphabet has raised intense controversy about organising a data trust intended to protect personal data from the data-extractive business model of platform providers (Artyuishina Citation2020). This example underlines how control or ownership of data and information is key to digital urban projects. But are these issues of concern reflected in approaches to digital urban nature? What kinds of urban communities are being created around human-nature relations with the help of technological devices? How far are digital technologies mediating novel ways of commoning urban nature through collective use? These are the questions that emerge from a critical juxtaposition of the literature on digital commons and urban commons.

Linking both interfaces addressed—on smart environments/urban nature and on digital commons/urban commons—urban nature turns into a hybrid realm: socially produced but not fully controlled, represented in different forms of knowledge and open to different kinds of use. Therefore, our concern lies in whether and how digital technologies mediate (1) new meanings and (2) new representations of urban nature, and how these link with (3) new uses of urban nature, as well as (4) relations between nature and humans, as core dimensions of empirical analysis. The two interfaces substantiate our exploration of digital urban nature in different and novel ways. Whereas scholarship on smart cities and urban nature can reveal how digital technologies might be generating new understandings and depictions of nature in the city, work on digital and urban commons can help unpack issues of access and control involved in the private or collective use of urban nature mediated by digital technologies.

Digital nature projects in Berlin

Berlin has long been a locus for pioneering research on urban nature. The Berlin School of Urban Ecology, originating in the 1970s, contributed significantly to our appreciation of hidden natures in urban wastelands, streetscapes and cemeteries (Lachmund Citation2013; Winter Citation2015; Kowarik Citation2018). Its advocacy of the distinctiveness of nature in the city has proved instrumental—alongside pressure from social activists—behind enrolling the city government in policies to protect and promote urban nature ever since (Lachmund Citation2013). Yet, when Berlin published its Smart City Strategy in 2015, no reference was made to digitally mediated flora and fauna (SenStadtUm Citation2015). Even when Berlin’s smart city initiative became more inclusive under a red-red-green coalition government in 2016, ‘nature’ was still not included as one of the topics on its interactive project map.Footnote1 Why is this the case, when the city boasts so many projects that explicitly use digital technology to feature urban nature?

Berlin’s digital urban nature projects

An initial exploratory venture into the field resulted in a sample of over 20 digital nature projects that was reduced to a database of 12 meeting the following criteria: being focused on urban nature, involving digital apps, databases or platforms and having a base in Berlin. This database, created from an analysis of project websites, represents the first mapping exercise of digital nature schemes conducted in any city. By categorising these schemes according to their year of origin, initiator, urban nature addressed, aim and modes of digitalisation (see ), important pointers emerge to help explain their absence in the smart city policy discourse.

Table 1: Profiles of digital urban nature projects in Berlin (Source: own compilation)

The database proves that digital urban nature initiatives are not a recent phenomenon in Berlin. Several of the 12 profiled projects are over ten years old. Nine of them were already operative when Berlin passed its Smart City Strategy, oblivious to their existence. As might be expected, whilst the older projects tend to focus on providing information, the recent initiatives are more interactive in their generation and use of data.

What is striking about the initiators of each project is the complete absence of major corporate enterprises that otherwise feature strongly in smart city projects. Berlin’s digital nature projects are largely non-commercial. The majority are led either by local state agencies (e.g. Geoportal Berlin, Stadtbaumkampagne) or by publicly funded research institutes (e.g. Verlust der Nacht, Portal Beee, Füchse & Co., Naturblick). Where companies provide the lead (e.g. I plant a tree, naturtrip.org, Green City Solutions, IPGarten), these are small start-ups with a strong sustainability ethos to promote ecosystem services. This helps explain the invisibility of urban nature in a smart city strategy oriented, rather, towards infrastructure service providers and business opportunities.

The non-marketable thrust of the 12 projects is underlined by their targets and purposes. Some are broad in scope, encompassing urban biodiversity in general (e.g. Umweltkalender, Portal Beee, Naturblick). Others target a type of natural site, such as recreational landscapes (naturtrip.org) or nocturnal habitats (Verlust der Nacht). Most, though, specialise in a particular group of flora or fauna in the city, whether wild animals (Füchse & Co.), trees (I plant a tree, Stadtbaumkampagne) or edible plants (mundraub). Only a few are restricted to simply providing information about urban nature to Berlin’s citizens (Geoportal Berlin, Umweltkalender, naturtrip.org). Most go further, encouraging users to interact with local flora and fauna (Naturblick, mundraub), to contribute their own data via citizen science platforms (Verlust der Nacht, Portal Beee, Füchse & Co.) or to alter the natural environment themselves (I plant a tree, IPGarten).

Diverse aims call for diverse modes of digitalisation. Different technological devices and software are enrolled, depending on whether the activity involves mapping, monitoring, measuring, connecting or simply communicating data about urban nature in Berlin. Websites and digital platforms are used by all 12 projects, with digital maps important to those depicting geodata (e.g. Geoportal Berlin, Stadtbaumkampagne). Several projects have developed customised apps for user information and interaction (e.g. mundraub, Verlust der Nacht). Some of them draw on the camera or microphone functions of a smartphone (e.g. Naturblick), GPS sensors or external sensors (e.g. Green City Solutions) to provide environmental data.

A typology of digital urban nature projects

To make sense of these 12 projects in Berlin, but also to provide guidance for future research elsewhere, an exploratory typology of digital urban nature projects was developed (see ). This typology is designed to demonstrate how the four dimensions to the analytical framework of this paper—the meaning of nature, its representation, its use and relations with nature—find expression in projects of this kind. Bringing to the fore the key functions of digitally mediated nature, the exercise revealed five generic types of digital nature projects prevalent in Berlin: ‘Informative’, ‘Motivational’, ‘Observatory’, ‘Interventionist’ and ‘Collective’.

Table 2: Five types of digitally mediated urban nature projects (Source: own compilation, derived from the database on Berlin)

The ‘Informative’ type of project applies digital tools primarily to inform people about urban nature, using accessible formats like digital calendars, maps or platforms. Other projects do more than merely inform; they seek to raise awareness about nature and encourage direct contact with nature in the city. This ‘Motivational’ type of project treats nature as an urban space that can be discovered and experienced in a novel way. More research-oriented projects that enrol users in the monitoring and reporting of urban nature with digital devices are represented in the type ‘Observatory’. This applies, for instance, to projects using citizen science methods to generate data beyond the academy. The fourth type, ‘Interventionist’, characterises digital projects that empower people to alter the existing natural environment in innovative ways, such as the IPGarten project with its virtual platform enabling users to determine what gets planted in a real garden. The fifth type is inspired by projects advocating digitally mediated forms of community-building around the collective use of urban nature. Projects belonging to this ‘Collective’ type tend to treat urban nature as commons that require stewardship by the community.

The case studies: Naturblick and mundraub

The explanatory capacity of this typology is, by virtue of its origins, limited. For a deeper understanding of the digital mediation of urban nature in Berlin, two projects were selected from the database for closer analysis: the app Naturblick and the initiative mundraub. These two were singled out because each speaks powerfully to the four issues of urban nature addressed in this paper—meanings, representations, uses and relations—yet in different ways. Naturblick is particularly suited to exploring novel ways of understanding and representing urban nature with digital devices, while mundraub addresses, rather, the digitally mediated use of, and relations with, urban nature. The two projects were also chosen for being well established and originating from Berlin. In the absence of documentation on both projects beyond their respective websites and the limited literature, the method of research relied on 11 expert interviews. These were conducted in the summer of 2017 with representatives from local government, administration and NGOs as well as with the developers and users of the projects (see the list of interviewees following the references). The interviews were conducted using partially standardised questions. They were transcribed and coded according to qualitative content analysis around the four analytical dimensions ‘meaning’, ‘representing’, ‘using’ and ‘relations’.

Naturblick

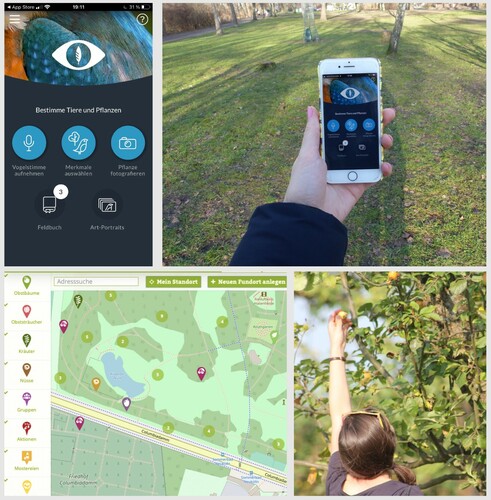

The Naturblick app was launched in 2015 by the Natural History Museum of Berlin and is sponsored by the Federal Ministry of the Environment. It is embedded in an interdisciplinary research project, entitled ‘Discover Urban Nature’ (CitationNaturblick website). Its main function is to help users discover plant and animal life in selected green spaces, combining a wildlife database with GPS tracking. The dual purpose of the app is to raise awareness of nature in the city and provide environmental education in a digital form (Interview A). Any smartphone user can download the app and use its database to identify species of flora and fauna encountered in the city with the help of the phone’s microphone, speaker and camera (see ). The app has a map function that, via a GPS sensor, can guide the user to sites of biodiversity interest. The updated version has a citizen science component, allowing users to report sightings and observations to a Wiki Open Nature Guide. The target audience for the Naturblick app is primarily young adults, who are encouraged through its playful approach to engage more with their natural surroundings. This is in line with concern that, partly because of digitalisation, young urban adults are spending less time experiencing nature than earlier generations (Kowarik Citation2018, 340).

Figure 1: The Naturblick and mundraub apps and their uses. The image on the top left shows the main menu of the Naturblick app (Source: own screenshot). On the top right is a photo of the Naturblick app in use (Source: own photograph). On the bottom left is the mundraub map (Source: own screenshot of https://mundraub.org/map). The image on the bottom right shows the mundraub app in use (Source: https://mundraub.org/press).

Mundraub

Mundraub is a digital platform depicting edible vegetation in the city that was set up in 2009 by a non-profit company, Terra Concordia gUG, based in Berlin. Led by its founder and managed by a small team, mundraub encourages citizens to engage in community-based foraging of fruits, nuts and herbs that grow in public urban space. An online map depicts where to find this ‘edible urban nature’ (Mundraub blog of Citation23 June Citation2015). Registered users can edit the map by setting coloured pins for marking locations or commenting on harvesting activities (see ). In addition, mundraub has a portal for users to form groups, plan activities or exchange their experiences and knowledge. The designers of mundraub aspire to raise awareness of the origins of food and its availability in urban public space but also—more fundamentally—to challenge consumerist society by advocating the collective use of available food that might otherwise rot. In the words of a recent publication, ‘mundraub brings together fruit trees and people, making the food commons of publicly edible plants visible’ (Scharf et al. Citation2019, 5).

Both Naturblick and mundraub are encouraging new ways of seeing and using nature in the city. In the following sections, we analyse how far this is happening, using the two conceptual interfaces presented earlier. First, we assess the extent to which nature in the city is being represented in novel ways through these schemes, drawing on knowledge generated by the literatures on smart environments and urban nature. Second, we consider how far the two projects are generating new uses of nature in the city, framing the analysis in terms of research on digital and urban commons.

Meanings and representations of urban nature

Taking the first analytical lens, we assess how far the digital content and formats of the two projects are transforming the ways urban nature is conceived and represented. At the conjuncture of critical research on smart urban environments and on urban nature we are interested here in establishing whether digital technologies are enhancing the hybridity of nature-society relations or reinforcing popular distinctions and what (and whose) notions of urban nature are being foregrounded through these technologies.

Both the Naturblick app and the mundraub platform were designed to encourage users to take a fresh look at the city around them and the rich biodiversity it harbours. Both assert that nature is, indeed, constitutive of the urban condition. Both aspire to present urban nature in a more accessible and interactive manner than would ever be possible using analogue techniques. Naturblick, for instance, uses a smartphone’s microphone to record birdsong that can then be analysed according to pre-programmed algorithms to identify the type of bird. Mundraub uses a digital platform to enable users to inform each other about the location, availability and ripeness of edible flora in the city. Both projects, further, claim to reveal the unexpected in the city, whether nature on your doorstep (Naturblick) or edible nature on street corners (mundraub). The educational thrust of Naturblick is posited on revealing how much ‘nature’ really does exist in the city. Mundraub is intent on showing how some of this urban nature encountered in public spaces can actually be eaten. Both projects present information for their respective realm—urban biotopes and wild species as well as edible nature—in a central online site or app, yet without the ambition of becoming the authoritative data source in these fields.

Our analysis shows that both digital schemes have developed a strong following in Berlin. To date, the Naturblick app has been downloaded more than 130,000 times and plans are afoot to extend it to cities across Germany (Naturblick press statement of Citation15 April Citation2019). Clearly, the app has proven a popular tool for accessing data about urban nature on-site without having to consult a conventional guidebook (Interview H). As one user stated: ‘what’s practical about the app is that I can integrate it into my daily life. I don’t need to take anything else with me' (Interview C). The low knowledge threshold designed into the app means that it is accessible to people with little understanding of natural species (Interview J). Mundraub, by its own account, represents the largest digital platform for accessing edible nature worldwide. Currently (January 2021), the website records ca. 73,000 users and 53,000 locations of edible plants globally, primarily in Germany (CitationMundraub website). In Berlin, mundraub has over 1500 registered users (there exist many more unregistered users) and maps around 7000 locations of edible nature across the city. Mundraub’s success lies in showing its users that nature can be more than a landscape feature. Cities host ‘wild’ nature that can be eaten, as well as admired (Interview F). Digital tools make it possible, for the first time, to record this edible urban nature on a comprehensive scale and to enable people to inform others in real time about when an individual tree, bush or plant is ripe for harvest (Interviews I and K). In the words of one user: ‘It’s a lot of fun. You enter something on the map and then watch how people take it up’ (Interview E).

Significantly, our interviewees report how the projects are influencing their understanding of nature in Berlin. Naturblick users talk of becoming more aware of the nature they encounter while passing through the city, seeking out promising natural habitats and expanding their knowledge of natural species. In the words of one: ‘The more birdsong you recognise and animals or plants you can identify, the more interdependencies and changes you see around you’ (Interview B). Another relates how the app has made her more alert as she walks through the city (Interview C). This enhanced sensory experience of urban nature is not just visual but also—in the case of Naturblick—acoustic. As one of the designers explains, ‘we are using the microphones and loudspeakers [of a smartphone] to identify species in a completely different way. We can apply algorithms that you could never represent in a handbook’ (Interview A). Mundraub users also report developing heightened sensitivity towards urban nature: in this case to the existence of edible nature in the urban landscape. One describes how mundraub has encouraged them to explore new parts of the city in search of food: ‘I discover places I wouldn’t visit normally, because without mundraub I wouldn’t know there was something interesting to eat there’ (Interview F). Mundraub is mediating new ‘augmented realities’ of urban nature through the senses of taste and smell, as well as sight.

However, a closer look reveals how the conceptualisations of urban nature of both projects are circumscribed by selective framings that draw on conventional and anthropocentric notions of nature. In the case of the Naturblick app, the information provided is structured according to classifications found in conventional nature guidebooks. Curated by the Natural History Museum, Naturblick presents the experts’ view on urban nature. The stewardship of data is the preserve of scientists. The citizen science component recently introduced to the project makes it more interactive than it was originally, but the public is entrusted only with delivering data for predetermined projects to the curators, rather than contributing new angles on nature. Digital technologies are applied to render the common practice of identifying species easier, rather than to explore representations of nature beyond textbook categories. The social-ecological entanglements of urban nature familiar to debates in urban studies do not figure in the app. The hope expressed by Matthew Gandy (Citation2006, 73) that ‘[i]t is perhaps only through an ecologically enriched public realm that new kinds of urban environmental discourse may emerge that begin to leave the conceptual lexicon of the nineteenth-century city behind’ has not been fulfilled by the Naturblick project. Nature is portrayed very much in the positivist tradition of the biological sciences, as an object of observation and control. The socio-natures that have featured so prominently in research on Berlin are absent.

The same applies to the sites where urban nature is envisaged. Naturblick’s map function is restricted to officially designated green spaces only. Although the app aspires to present the city as an unexpected locale for nature, its map does not consider the nature prevalent in urban gardens, roadsides or so-called wastelands. This is a curious, but revealing, omission. It suggests that the design of the app has been strongly framed by old-fashioned notions of ‘beautiful nature’ (Lossau and Winter Citation2011) and where it is to be found. This is particularly surprising given Berlin’s reputation as a site of pioneering research into spontaneous vegetation, described above. The structure and content of the app, in short, uses digital technology to reinforce, rather than question, positivist, anthropocentric representations of urban nature.

In the case of mundraub, the selective framing is of edible nature. Its interactive platform categorises urban nature according to whether it is consumable by humans. Identifying where fruit, nuts and herbs can be found on accessible land is the prime function of its map (see ). In terms of the diverse representations of nature characterised by Julia Lossau and Katharina Winter (Citation2011), mundraub is clearly focused on ‘useful nature’, privileging an anthropocentric perspective. The project’s rhetorical framing around creating awareness for urban nature cannot conceal the underlying motive of deriving human value from a natural resource. In this way, mundraub embraces a social-ecological understanding of urban nature characterised by relations between humans and fruit-bearing trees. The digital technologies are, indeed, instrumental in optimising this relationship, from a user’s perspective. They make it possible to identify edible nature in unusual places. Unlike Naturblick, mundraub is not bound by conventional notions of where nature is to be found in the city. Mundraub’s selective focus, however, blinds it to natures of a non-nutritional value. The harvester’s nature is the only one that counts.

Individual and collective uses of urban nature

This brings us to the second analytical lens—along the interface between digital and urban commons—and the question of how far the two cases studied are changing (collective) uses of, and relations with, urban nature. Commons research, as discussed earlier, highlights the transformative potential of collectively using and controlling resources, creating openings for new relations between people, technologies and cities. Given the mainly non-commercial logic driving all 12 projects of our database, most of which are led by grassroots or public organisations, the expectation is that they will exhibit tendencies favourable to processes of ‘commoning’, as expressed by communities using or distributing ‘nature’ via collective modes of ownership or stewardship.

In the cases of Naturblick and mundraub, we observed how both have used digital technologies to successfully attract a wide range of interested publics, reaching beyond their original target audiences. Naturblick is encouraging not just young people, but anyone with a smartphone to interact more with nature in the city. It is motivating users to conduct walks or spontaneous observations in the city’s parks and forests while providing information at their fingertips. This experience is, despite the recent addition of an interactive component, essentially restricted to the individual. Even though Naturblick users praise the app for ‘opening up and giving people the chance to upload photos and information on places of rich nature’ (Interview C), Naturblick has no explicit ambition to inspire new collective modes of engagement with nature. Implicitly, nature is treated by the app’s designers and users as a commons, in the sense of it being generally available for public enjoyment and enrichment. Given its barrier-free access, the app’s data represents a form of knowledge commons on the city’s flora and fauna. In contrast to many commercial manifestations of the ‘smart’ city, this data can be freely shared and is not subject to commodification. The knowledge on urban nature presented by Naturblick, however, is generated not by means of ‘commons-based peer production’ (Bauwens, Kostakis, and Pazaitis Citation2019), but by experts who control the degree of detail provided, the structure of species classification and the locations included in the digital maps. There is a clear distinction between who curates and who uses the app’s data.

The mundraub platform is also changing the way people experience and use nature in their city. Some users talk of how mundraub has nurtured within them a harvesting instinct: ‘now, whenever I go along the Warschauer [Street], I always look up at the chestnut tree’ (Interview E). Others are attracted by the community spirit engendered via the platform: ‘you bring people together and perhaps they bring even more people in—that’s really cool' (Interview F). The ability of mundraub’s technology to build networks between urban residents sharing information and interests on edible nature is acknowledged by local environmental NGOs (Interview H). These statements resonate with the findings of Landor-Yamagata, Kowarik, and Fischer (Citation2018) that urban foraging in Berlin is generating stronger engagement with nature.

Unlike Naturblick, mundraub explicitly aspires to generate new practices of commoning urban nature. Its designer terms what they have created a ‘food commons on the internet’ (Interview D). Mundraub regards publicly accessible, edible nature as a commons that needs mobilising—with the help of ICTs—to the benefit of humans. It targets the urban poor, in particular, as potential beneficiaries of this readily accessible, free food. Mundraub is using digital technology to enrol users in a new appreciation of the existence and value of the ‘edible city’. More than this, its digitally mediated platform is creating a community of users who are harvesting individually and in groups to develop collective forms of use. This represents a novel form of peer production of an urban commons, in which the users own and control the data. Nuts, fruits and herbs had always been available in the city, but the intervention of a digitally mediated, interactive platform of multiple users transformed these plants into an urban commons sought out and used by an ever-growing community of foragers. Mundraub is a fine example of the ‘collaborative use of idling resources enabled by ICT’ (Zvolska et al. Citation2019, 628). Nevertheless, the purpose and practice of this ‘commoning’ of urban nature is strongly anthropocentric, oriented towards optimising human benefit from a natural resource through digitally mediated mobilisation and exchange. Arguably, mundraub is more about moulding humans than natures.

Although most users ascribe to mundraub’s rules of limited consumption for their own needs, a few have over-used this urban commons for personal gain. Instances of over-harvesting reveal problems around users’ willingness or ability to follow its script on the collective stewardship of nature. Observers report how a whole tree can be harvested overnight, often before the fruit is fully ripe (Interviews E and H). Mundraub’s designer concedes there is a problem when ‘people just turn up, strip the lot and sometimes even break off a whole branch’ (Interview D). When this happens, the suspicion is that the harvest is subsequently being sold for profit rather than consumed by the forager (Interview E). Clandestine commodification of the edible commons flies in the face of mundraub’s aspiration to cultivate a sense of stewardship around publicly accessible food. An officer of Berlin’s Environment Department calls it ‘a bit like the tragedy of the commons that belongs to nobody’ (Interview G). The inability of mundraub to deal with instances of over-exploitation has gained it an ambivalent reputation amongst environmentalist NGOs and the city administration (Interviews H, I and G). Their reluctance to cooperate with the organisation goes some way towards explaining the criticism of over-bureaucracy levelled by mundraub’s founder at the city authorities (Zvolska et al. Citation2019). There are signs, though, that mundraub has recognised the need to address its deficits, for instance by allowing only registered users to set new locations. In a recent project, ‘Edible Pankow’, the district administration has planted an orchard that is maintained by the mundraub community (Pankow district press statement of Citation30 November Citation2016). What these tensions are revealing is that mundraub’s digital platform cannot be programmed to favour the responsible use of nature but has generated both beneficial and exploitative interventions. Mundraub may be generating a new domain of nature-technology-human relations, but it is struggling to ensure this relationship is always benign.

Conclusions

For all the attention paid to urban environments in the smart city debate, astonishingly little consideration has been given to the digital mediation of a city’s flora, fauna and habitats. Urban nature is a void in current smart city research and policy. Our paper has demonstrated that this lack of interest cannot be attributed to a dearth of nature-related digital projects. The example of Berlin, which hosts more than a dozen projects of this kind, suggests that much is happening below the radar of the smart city community. Our empirical analysis revealed these schemes to be highly diverse in terms of the lead actors, the kind of urban nature addressed, the aims pursued and the mode of digitalisation. Why, then, are such digital urban nature projects so invisible in the smart city discourse? One explanation we have produced is the relative insignificance of commercial drivers to these projects. The lead partners identified are either public organisations (local authorities, museums, research institutes), civil society groups or non-profit start-ups. The absence of corporate business in these projects is striking—in marked contrast to smart city partnerships around the world. The data exchanged by the digital urban nature projects is not commodified, even when it is collected or managed privately. A second explanation is that, interestingly, none of the urban nature projects in Berlin refer to themselves as ‘smart’. Since they do not see themselves as part of the smart city agenda, most do not feel excluded from it. This points to a more fundamental issue about the meaning and purpose of ‘smart’. It is not just that urban nature has been overlooked in strategic considerations of digitalising the city, but that the kinds of actors involved, objectives pursued and publics enrolled in digital urban nature schemes are distinctly different from the technical-managerial and commercial-corporatist models that characterise most smart city initiatives. This incompatibility reveals in stark relief how exclusive notions of ‘smart’ can be, in terms of the communities, agendas and interactions they target.

How can a focus on urban nature contribute, then, to a more inclusive understanding of urban digitalisation? One obvious response, emerging from our study, is that urban nature is being mediated by technological devices in practice, even if this is not acknowledged in policy and research on the smart city. Research on the environmental dimensions of smart urbanism, in particular, could benefit from addressing nature alongside the more familiar themes of material flows, atmospheric pollution and energy demand and supply. This would not only fill a thematic gap in existing knowledge, but also inspire new understandings of human-technology relations revealed by relations with living organisms. It would be intriguing to establish how nature is addressed in the smart city initiatives of other cities, what schemes exist that target urban nature and what part they play in the political agenda of urban digitalisation. This paper developed an initial typology of digital urban nature projects in Berlin that could guide studies of this kind elsewhere. Each of the project types identified there reveals particular opportunities, but also risks, in reconfiguring the relationship between nature, technology and humans. Thus, an ‘Informative’ type of project raises concerns about who owns and controls the data, how users are to be enrolled and what data is made publicly available, whilst a ‘Motivational’ project poses additional questions about whose educational ideals it is privileging and whose interests might be excluded. An ‘Observational’ project needs questioning in terms of the way urban nature is categorised and classified, whilst an ‘Interventionist’ project requires careful deliberation over what kinds of urban nature are deemed desirable by whom and for whom. Finally, a ‘Collective’ project may create novel modes of community stewardship, but is liable to abuse, raising questions about the regulation of data and practice through digital portals.

What this paper has argued throughout is that a spotlight on urban nature can advance our understanding of the relationship between digitalisation and urban nature in several ways, although in practice the orientation is often strongly anthropocentric. The examples of Naturblick and mundraub in Berlin indicate that projects using digital technologies to encourage greater awareness of, and interaction with, nature are mediating new ‘augmented realities’ of urban nature. They are providing much easier access to knowledge on nature in the city than analogue techniques could ever achieve, and—thanks to the near-ubiquity of the smartphone—are being applied by a larger number of people than originally anticipated. Users of the digital apps and platforms report seeing nature with greater intensity, in unexpected places and in unfamiliar guises.

Such positive impacts, important though they are, need to be critically appraised in the light of broader issues of representing nature via digital means. The dialogue established between research on smart environments, urban nature and the commons revealed that issues of data ownership and control go largely unreflected in many of the projects studied and, consequently, the social construction of urban nature by the project designers passes unchallenged. As the case of Naturblick reveals, even a favourable context for alternative understandings of urban nature, as in Berlin, is no guarantee that nature-based projects will draw on existing local knowledge. This points to the need for projects of this kind to embrace innovation not merely through the digital technologies they apply, but also from the urban context they address.

Beyond the representation of nature in the city, the projects studied are also influencing the ways people are using urban nature, individually and collectively. Particularly in the case of the mundraub scheme, novel collective forms of usage are emerging that would be inconceivable without the real-time, site-specific data afforded by its interactive platform. Our discussion of digital and urban commons, by highlighting the relationship between digital and analogous communities, has revealed the digitally mediated use of urban nature, however, to be ambivalent. Mundraub has stimulated novel processes of ‘commoning’ an urban resource but is running up against a classic conundrum of common pool resource governance. This draws attention to the unintended consequences of a deliberately unregulated mode of knowledge exchange that, in this case, facilitated the over-exploitation of urban nature by some users.

To wrap up, many of the digital urban nature projects encountered, although widely popular and potentially transformative, are essentially anthropocentric in orientation. They are geared towards enhancing the human experience of urban nature, while concealing social-ecological interdependencies and elusive features of urban nature. The digitally mediated representations and uses of urban nature witnessed in Berlin are opening up new avenues for human enjoyment, but not—as yet—seriously challenging notions of urban environments as objects of human use and control. Ironically, past research on and in Berlin—as well as within the wider community of urban studies—can provide important pointers for more inclusive, holistic and relational understandings of digitally mediated urban nature. These include unfamiliar natures, socio-natures and socio-ecological-digital hybrids. Exploring how these are being constructed and mediated by digital technologies in practice is a promising avenue for future research into rendering the digital city more sustainable.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their thanks to the two anonymous reviewers and the editorial team for their very helpful suggestions for improving the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Timothy Moss

Timothy Moss is a Senior Researcher in the Integrative Research Institute on Transformations of Human-Environment Systems (IRI THESys) at the Humboldt University of Berlin. Email: [email protected]

Friederike Voigt

Friederike Voigt is a landscape planner for the planning consultants gruppe F—Freiraum für alle GmbH in Berlin. Email: [email protected]

Sören Becker

Sören Becker is a Research Associate and Lecturer in the Department of Geography at the University of Bonn. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 https://www.smart-city-berlin.de/en/projects-map/, accessed 9 March 2020.

References

- Angelo, H., and D.Wachsmuth. 2015. “Urbanizing Urban Political Ecology. A Critique of Methodological Cityism.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (1): 16–27. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12105

- Artyuishina, A. 2020. “Is Civic Data Governance the key to Democratic Smart Cities? The Role of the Urban Data Trust in Sidewalk Toronto.” Telematics and Informatics 55: 101456. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2020.101456

- Ash, J., R.Kitchin, and A.Leszczynski. 2018. “Digital Turn, Digital Geographies.” Progress in Human Geography 42 (1): 25–43. doi: 10.1177/0309132516664800

- Bauwens, M., V.Kostakis, and A.Pazaitis. 2019. Peer to Peer. The Commons Manifesto. London: University of Westminster Press.

- Becker, S., M.Naumann, and T.Moss. 2017. “Between Coproduction and Commons: Understanding Initiatives to Reclaim Urban Energy Provision in Berlin and Hamburg.” Urban Research & Practice 10 (1): 63–85. doi: 10.1080/17535069.2016.1156735

- Berlant, L. 2016. “The Commons: Infrastructures for Troubling Times.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 34 (3): 393–419. doi: 10.1177/0263775816645989

- Brantz, D., and S.Dümpelmann, eds. 2011. Greening the City: Urban Landscapes in the Twentieth Century. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- Burton, K., A.Karvonen, and F.Caprotti. 2019. “Smart Goes Green. Digitalising Environmental Agendas in Bristol and Manchester.” In Inside Smart Cities. Place, Politics and Urban Innovation, edited by A.Karvonen, F.Cugurullo, and F.Caprotti, 117–132. London: Routledge.

- Cardullo, P. 2019. “Smart Commons or a ‘Smart Approach’ to the Commons?” In Right to the Smart City, edited by P.Cardullo, C.Di Feliciantonio, and R.Kitchin, 85–98. London: Routledge.

- Cardullo, P., and R.Kitchen. 2018. “Smart Urbanism and Smart Citizenship: The Neoliberal Logic of ‘Citizen-Focuses’ Smart Cities in Europe.” Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space. doi:10.31235/osf.io/xugb5.

- Colding, J., S.Barthel, P.Bendt, R.Snep, W.van der Knaap, and H.Ernstson. 2013. “Urban Green Commons: Insights on Urban Common Property Systems.” Global Environmental Change 23 (5): 1039–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.05.006

- Davis, J., A.Moulton, L.Van Sant, and B.Williams. 2019. “Anthropocene, Capitaloscene, … Plantationoscene? A Manifesto for Ecological Justice in an Age of Global Crisis.” Geography Compass 13 (5): e12438. doi: 10.1111/gec3.12438

- Derickson, K. D. 2017. “Urban Geography III: Anthropocene Urbanism.” Progress in Human Geography 42 (3): 425–435. doi: 10.1177/0309132516686012

- Eizenberg, E. 2012. “Actually Existing Commons: Three Moments of Space of Community Gardens in New York City.” Antipode 44 (3): 764–782. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8330.2011.00892.x

- Gabrys, J. 2014. “Programming Environments: Environmentality and Citizen Sensing in the Smart City.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 32: 30–48. doi: 10.1068/d16812

- Gandy, M. 2006. “Urban Nature and the Ecological Imaginary.” In In the Nature of Cities. Urban Political Ecology and the Politics of Urban Metabolism, edited by N.Heynen, M.Kaika, and E.Swyngedouw, 63–74. London: Routledge.

- Gandy, M. 2015. “From Urban Ecology to Ecological Urbanism: An Ambiguous Trajectory.” Area 47 (2): 150–154. doi: 10.1111/area.12162

- Gandy, M., and S.Jasper, eds. 2020. The Botanical City. Berlin: Jovis.

- Graham, M., and M.Zook. 2013. “Augmented Realities and Uneven Geographies. Exploring the Geolinguistic Contours of the Web.” Environment and Planning A 45 (1): 77–99. doi: 10.1068/a44674

- Harvey, D. 2012. Rebel Cities. From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. New York: Verso.

- Hess, C., and E.Ostrom, eds. 2007. Understanding Knowledge as a Commons. From Theory to Practice. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Heynen, N., M.Kaika, and E.Swyngedouw. 2006. “Urban Political Ecology. Politicizing the Production of Urban Natures.” In In the Nature of Cities. Urban Political Ecology and the Politics of Urban Metabolism, edited by N.Heynen, M.Kaika, and E.Swyngedouw, 1–20. London: Routledge.

- Hollands, R. G. 2008. “Will the Real Smart City Please Stand Up?” City 12 (3): 303–320. doi: 10.1080/13604810802479126

- Karvonen, A. 2011. Politics of Urban Runoff: Nature, Technology, and the Sustainable City. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Karvonen, A., F.Cugurullo, and F.Caprotti. 2019. “Introduction. Situating Smart Cities.” In Inside Smart Cities. Place, Politics and Urban Innovation, edited by A.Karvonen, F.Cugurullo, and F.Caprotti, 1–12. London: Routledge.

- Kitchin, R., T.Lauriault, and G.McArdle. 2015. “Knowing and Governing Cities Through Urban Indicators, City Benchmarking and Real-Time Dashboards.” Regional Studies, Regional Science 2 (1): 6–28. doi: 10.1080/21681376.2014.983149

- Kowarik, I. 2018. “Urban Wilderness: Supply, Demand, and Access.” Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 29: 336–347. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2017.05.017

- Lachmund, J. 2013. Greening Berlin. The Co-Production of Science, Politics, and Urban Nature. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

- Landor-Yamagata, J. L., I.Kowarik, and L. K.Fischer. 2018. “Urban Foraging in Berlin: People, Plants and Practices Within the Metropolitan Green Infrastructure.” Sustainability 10 (6): 1873. doi: 10.3390/su10061873

- Lossau, J., and K.Winter. 2011. “The Social Construction of City Nature: Exploring Temporary Uses of Open Green Space in Berlin.” In Perspectives in Urban Ecology, edited by WilfriedEndlicher, 333–345. Berlin: Springer.

- Luque-Ayala, A., C.McFarlane, and S.Marvin. 2016. “Introduction.” In Smart Urbanism: Utopian Vision or False Dawn?, edited by S.Marvin, A.Luque-Ayala, and C.McFarlane, 1–15. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Luvisi, A., and G.Lorenzi. 2014. “RFID-Plants in the Smart City: Applications and Outlook for Urban Green Management.” Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 13 (4): 630–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2014.07.003

- Martin, C. J., J.Evans, and A.Karvonen. 2018. “Smart and Sustainable? Five Tensions in the Visions and Practices of the Smart-Sustainable City in Europe and North America.” Technological Forecasting & Social Change 133: 269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2018.01.005

- Mundraub Blog of 23 June 2015. https://mundraub.org/blog/janz-berlin-eene-k%C3%BCrsche (accessed 31 March 2020).

- Mundraub Website. http://www.mundraub.org/ (accessed 31 March 2020).

- Naturblick Press Statement of 15 April 2019. https://www.museumfuernaturkunde.berlin/de/presse/pressemitteilungen/naturblick-bietet-digitalen-zugang-zu-natur-jetzt-allen-deutschen-staedten (accessed 9 July 2019).

- Naturblick Website. http://naturblick.naturkundemuseum.berlin/ (accessed 31 March 2020).

- Ossewaarde, M., and W.Reijers. 2017. “The Illusion of the Digital Commons. ‘False Consciousness’ in Online Alternative Economies.” Organization 24 (5): 609–628. doi:10.1177/1350508417713217.

- Ostrom, E. 1990. Governing the Commons. The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pankow District Press Statement of 30 November 2016. Accessed July 9, 2019. https://www.berlin.de/ba-pankow/aktuelles/pressemitteilungen/2016/pressemitteilung.536803.php.

- Pincetl, S. 2012. “Nature, Urban Development and Sustainability – What New Elements Are Needed for a More Comprehensive Understanding?” Cities 29: S32–S37. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2012.06.009

- Rabari, C., and M.Storper. 2015. “The Digital Skin of Cities. Urban Theory and Research in the Age of the Sensored and Metered City, Ubiquitous Computing and Big Data.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 8 (1): 27–42. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsu021

- Radywyl, N., and C.Biggs. 2013. “Reclaiming the Commons for Urban Transformation.” Journal of Cleaner Production 50: 159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.12.020

- Ricci, D., G.Colombo, A.Neunier, and A.Brilli. 2017. Designing Digital Methods to Monitor and Inform Urban Policy. The Case of Paris and Its Urban Nature initiative. Accessed March 13, 2019. https://www.academia.edu/33729733/Digital_Methods_for_Public_Policy_Designing_Digital_Methods_to_monitor_and_inform_Urban_Policy._The_case_of_Paris_and_its_Urban_Nature_initiative.

- Rose, G. 2020. “Actually-Existing Sociality in a Smart City.” City 24 (3–4): 512–529. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2020.1781412

- Scharf, N., T.Wachtel, S. E.Reddy, and I.Säumel. 2019. “Urban Commons for the Edible City. First Insights for Future Sustainable Urban Food Systems from Berlin, Germany.” Sustainability 11 (4): 966. doi: 10.3390/su11040966

- SenStadtUm (Senatsverwaltung für Stadtentwicklung und Umweltschutz). 2015. Smart City-Strategie Berlin. Accessed June 13, 2019. https://www.berlin-partner.de/fileadmin/user_upload/01_chefredaktion/02_pdf/02_navi/21/Strategie_Smart_City_Berlin.pdf.

- Sharma, N., S.Greaves, A.Siddharthan, H. B.Anderson, A.Robinson, L.Colucci-Gray, A. T.Wibowo, et al. 2019. “From Citizen Science to Citizen Action: Analyzing the Potential for a Digital Platform to Cultivate Attachments to Nature.” Journal of Science Communication 18 (1): 1–35. doi: 10.22323/2.18010207

- Shaw, J., and M.Graham. 2017. “An Informational Right to the City? Code, Content, Control, and the Urbanization of Information.” Antipode 49 (4): 907–927. doi: 10.1111/anti.12312

- Shelton, T., and T.Lodato. 2019. “Actually Existing Smart Citizens.” City 23 (1): 35–52. doi: 10.1080/13604813.2019.1575115

- Skarlatidou, A., M.Ponti, J.Sprinks, C.Nold, M.Haklay, and E.Kanjo. 2019. “User Experience of Digital Technologies in Citizen Science.” Journal of Science Communication 18 (1): E1–E8.

- Smith, A., and P. P.Martín. 2020. “Going Beyond the Smart City? Implementing Technopolitical Platforms for Urban Democracy in Madrid and Barcelona.” Journal of Urban Technology 28 (1–2): 311–330. doi: 10.1080/10630732.2020.1786337

- Tironi, M., and T.Sánchez Criado. 2015. “Of Sensors and Sensitivities. Towards a Cosmopolitics of ‘Smart Cities’?” Tecnoscienza 6 (1): 89–108.

- Viitanen, J., and R. Kingston. 2014. “Smart Cities and Green Growth: Outsourcing Democratic and Environmental Resilience to the Global Technology Sector.” Environment and Planning A 46 (4): 803–819. doi: 10.1068/a46242

- Voigt, F. 2017. “Smart City-Nature.” Neue Perspektiven durch die Digitalisierung von Stadtnatur in Berlin. Master’s thesis, Leibniz University Hannover.

- Wachsmuth, D. 2016. “Three Ecologies. Urban Metabolism and the Society-Nature Opposition.” The Sociological Quarterly 53 (4): 506–523. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2012.01247.x

- Wilson, M. W. 2011. “Data Matter(s). Legitimacy, Coding, and Qualifications-of-Life.” Environment and Planning D 29 (5): 857–872. doi: 10.1068/d7910

- Winter, K. 2015. Ansichtssache Stadtnatur. Zwischennutzungen und Naturverständnisse. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Yigitcanlar, T. 2009. “Planning for Smart Urban Ecosytems: Information Technology Applications for Capacity Building in Environmental Decision Making.” Theoretical and Empirical Researches in Urban Management 3 (12): 5–21.

- Yusoff, K. 2019. A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Zvolska, L., M.Lehner, Y. V.Palgan, O.Mont, and A.Plepys. 2019. “Urban Sharing in Smart Cities: The Cases of Berlin and London.” Local Environment 24 (7): 628–645. doi: 10.1080/13549839.2018.1463978

- Interviews

- A: Naturblick Designer, 23 May 2017.

- B: Naturblick User, 19 June 2017.

- C: Naturblick User, 21 June 2017.

- D: Mundraub Designer, 24 May 2017.

- E: Mundraub User, 28 May 2017.

- F: Mundraub User, 6 June 2017.

- G: Officer of Nature Conservation Unit of the Berlin Senate Department for the Environment, Transport and Climate Protection, 19 June 2017.

- H: Representative of the Environmental NGO NABU, 20 June 2017.

- I: Representative of the Environmental NGO Grüne Liga, 12 June 2017.

- J: Officer of the Smart City Unit of the Berlin Senate Department for Economics, Energy and Municipal Enterprises, 8 June 2017.

- K: Researcher at the Urban Lab of the Technical University of Berlin, 27 June 2017.