Abstract

Despite the affluence of its city centre, Edinburgh’s waterfront remains a largely undeveloped patchwork of ex-industrial docklands. The Waterfront Edinburgh project in the early 2000s was an ambitious attempt to regenerate the former Granton Harbour. This paper takes a long-term view of the fate of that project—from grand potential, through stagnation and crisis, and back again to grand potential—to consider anew the use of the rent gap model in a context where gentrification seems to have failed. Threading together the changing fate of this site reveals the imaginary nature of potential and the limits to the state’s power, whilst reminding us that potential land values can (and must) go down as well as up.

Keywords:

Introduction

Kieran was working at a senior level in the housing strategy department at the City of Edinburgh Council.Footnote1 It was the mid-1990s, he recalls, when ‘the waterfront was surfacing as an area surplus to requirements. And so they thought let’s extend the city north, bigtime.’ Stretched over some 346 acres of land in Granton, this was to be, he recalls, ‘a regeneration and redevelopment project on a scale never before seen at any time in Edinburgh.’ Property values across the city were rising fast—up 82% in the first five years of the millennium (Mathews and Satsangi Citation2007, 502)—and the ‘potential’ for success was clear to see. ‘Economic conditions could not have been better’ insists Alasdair with more than a hint of sadness. Part of the team that oversaw this project in its infancy, he dwells on its failures with frustration tempered only by the passage of time. This promised to be a gilded case of an ‘urban renaissance’, converting 20th century dereliction into 21st century luxury. As McCrone (Citation2018) notes, the contractual basis of such projects writes-in an obligatory optimism, where the calculation of values rising renders new futures ‘realistic.’ This potential relies on confidence, and confidence needs to be continuously declared. But as the years passed, confidence slipped into the shadow of hubris. The project was flagging due to a slew of odd management decisions, a fast turnover of staff and a veil of secrecy. When 2008 swung around, the financial crisis put any lingering disagreements to bed. For most of the decade since, that turn-of-the-century vision for a sparkling waterfront has remained impossible, grimly laughable in a context of vacancy, stasis, and the evaporation of any coordinated ability to plan. In the last few years, however, development has begun anew at a striking pace.

The declared fate of this site has fluctuated from ‘surplus’ land to imagined opulence; back again to ‘surplus’ land and on to reimagined opulence. It is a story that plays out over multiple decades, with wildly varying calculations of what is possible, realistic, desirable and obtainable against the backdrop of an economic ‘reality’ that has both fed these visions and rendered them harshly irrelevant. Trying to explain this dynamic, I kept returning to Neil Smith’s (Citation1979) rent gap model, the basis of which is intentionally simple: as the value of a building declines over time, a ‘gap’ emerges between the capitalised ground rent (the profit currently made by the landowner) and the potential ground rent (the profit that could be made if the land were put to a different use). The wider that gap, the more profit can be made from a change in land use. The ingenuity of this model is that it looks like the models it was designed to critique. The value of land seems to follow a neat pattern divorced from conflict, naturalised as the agency of some invisible hand, but this is subverted, prompting instead a series of controversial questions around class, inequality, intentional disinvestment, and uneven development (Slater Citation2017). If the model encourages us to see devalorisation and revalorisation as intrinsically linked in the first instance then, just as importantly, it suggests that potential leads and realisation follows; the idea of higher profit prefigures the making of actual profit. In between those moments (of fantasy first and capitalisation second) agency lies, and this should not be mistaken for the simple passage of time. In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in this approach, and much of this scholarship details how the state is key to both opening and attempted closure of rent gaps at a variety of scales. Whether in Athens (Alexandri Citation2018), Beirut (Krijnen Citation2018), New York (Teresa Citation2019), Santiago de Chile (López-Morales Citation2010), or Taipei (Lan and Lee Citation2020), this is a state inseparable from processes of austerity, corruption, ineptitude, and competitive urbanism in which some cities, or some parts of cities, must ‘lose’ in order for others to ‘win.’

I seek to add to this scholarship by attempting something a little counter-intuitive: a defence of the model as a conceptual tool in a context where it seems to have failed. Down on Edinburgh’s waterfront, I argue, the rent gap model retains its relevance even though gentrification has felt like nothing more than a fantasy for decades, and a ludicrously ill-fitting one at that. The rent gap is fascinating precisely because it contains within its neat curves the necessity of failure, crisis, stagnation and dereliction, even whilst appearing to model a process that promises cleanliness, affluence, order and economic growth. For some fifty years now, scholars have been adept at chronicling the negative impact of gentrification when it ‘succeeds’, but the moral perniciousness of the process is such that when it fails, the impact can still be negative (in this instance, negative enough to justify the next attempt at success). This duplicity is reflected in Slater’s (Citation2014) notion of ‘false choice urbanism’. To put that another way, the rent gap does not presume to model a world that ‘works’ by the measure of its own rationality, one in which all of space marches onwards to a gentrified future. I want to bring some of this negativity to the forefront. Here the dynamic of the model appears to fail, but when looked at differently (where gentrification is one possible outcome, never guaranteed), it holds renewed value as a tool for understanding the link between devalorisation and revalorisation even in contexts where the passage between the two is by no means smooth or inevitable. As I hope to show, the leap (as verb, with intention) between fantasy and capitalisation is important, layered over but not reducible to the shift from devalorisation to revalorisation. This becomes clearer, I suggest, when the latter journey is interrupted, or curtailed altogether, and what we are left with is just the fantasy of closing the rent gap, the leap that falters.

To illustrate this, I present a potted history of the Waterfront Edinburgh project, here split into three stages that broadly map onto (i) the pre-crisis period of optimism, (ii) the post-crisis period of stasis, and (iii) the more recent shift back to optimism. The transition from one stage to the next is obviously not as neat as this typology implies, and the detail on the third is thinnest because it has only just begun to unfold. By ordering my narrative in this way, I do not wish to imply that the project has evolved in a linear or teleological fashion. At each step of the way, rationality has faltered, and projections have been proven spectacularly wrong (indeed, this lack of clear trajectory is precisely what fascinates me). The drawing out of the timing of the rent gap makes the imaginary nature of potential clearer, whilst highlighting the limits to the state’s power. It reminds us that potential land values can (and must) go down as well as up and, I argue, it suggests that the rent gap may still be useful in contexts where gentrification as a concept is only loosely fitting.

1999–2008: From ‘wasteland’ to ‘potential’

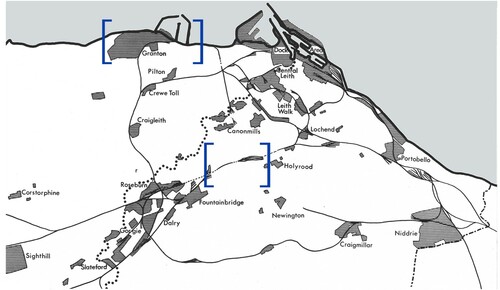

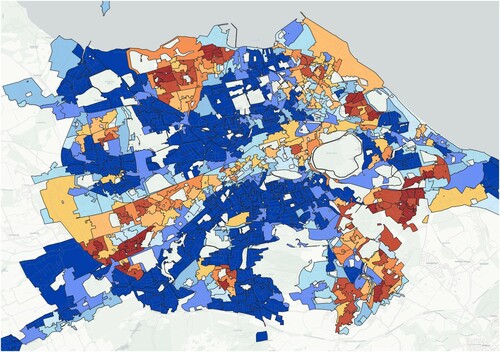

As Scotland’s capital city, Edinburgh—or at least its postcard-ready city centre—is often revered for its beauty. The consultancy firm ECA International (Citation2019) calls it the most ‘liveable’ city in the UK, a nebulous accolade which renders it less liveable for those who struggle to afford its rising rents, up 45% over the last decade (Citylets Citation2018). With a population of just over 520,000, its financial and tourism sectors are second only to London within the UK in terms of their size and value, which exacerbates the cost of urban land and the struggles over its use. Such affluence is by its very nature not homogenous, and the headline figures hide within them a city of sometimes striking inequalities, where ‘one of the highest concentrations of wealthy citizens in Scotland [exists] alongside some of the highest levels of poverty and deprivation’ (City of Edinburgh Council Citation2014, 7). Granton typifies this unevenness. It is an ex-industrial suburb two miles north of the city centre, bordered by local authority housing estates to the south and docklands buffering the banks of the Firth of Forth to the north (see and ).

Figure 1: Map of Edinburgh adapted from a 1960s atlas for local schools (The Edinburgh Branch of the Geographical Association Citationno date, 27). The shading represents areas zoned for industrial expansion by the city planning department. The blue brackets have been added to show the location of the Waterfront Edinburgh site in relation to the city centre.

Figure 2: Map of Edinburgh showing the 2020 rankings for deprivation, ranging on a scale from most affluent (dark blue) to most deprived (dark orange). Map drawn by Frank Thomas, using data from the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation.

This neighbourhood used to be home to a major gasworks and one of the largest ink manufacturers in the world; it was an export port for salted herring, coal, and coke; there were shipbuilders, yacht-makers, and a large lemonade factory. It was, in short, a neighbourhood whose ‘heritage from the early nineteenth century onwards has been almost wholly industrial’ (Gracie Citation2003, 17). Hay (Citation2011) recalls how the majority of those who lived on the Lower Granton Road were employed in the manual trades: fish curers, market porters, house painters, printing operatives, fishermen, gas workers, joiners, tram drivers, railwaymen, bakers and engineers. Unlike much of central Edinburgh, here the scars of deindustrialisation are still starkly visible. By the early 1990s, the last large-scale employer had gone bankrupt or moved elsewhere. The local population went into freefall and the area developed a reputation as ‘one of morbid dereliction’ (Kerr Citation2005, 212). As the long twentieth century crept to a close, Granton represented some 54% of all the vacant land in one of the most affluent cities in Europe (City of Edinburgh Council Development Committee Citation1997, n.p.). And as Christophers (Citation2018) brilliantly shows, the demarcation of public land as ‘surplus’ has long marked the first step in the path towards its privatisation.

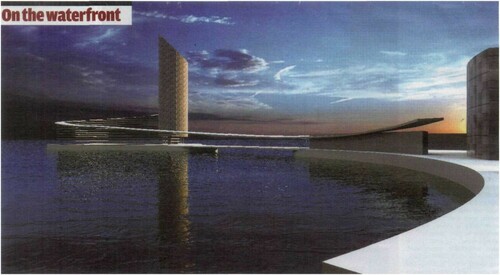

At the dawn of the new millennium, Waterfront Edinburgh Limited (WEL) was incorporated as a joint venture between the City of Edinburgh Council and Scottish Enterprise (a Scottish Government-owned investment company). WEL was a private company entirely owned and funded by different arms of the state and largely staffed by local authority planners on temporary secondment. It was a classic example of a public private partnership in which the expense and risk are borne almost entirely by the first part of that totemic dichotomy even whilst it masqueraded as following the rules of the second. WEL’s vision was hugely ambitious, promising to transform an area described as ‘cut-off, polluted, contaminated and a forgotten part of Edinburgh’ into ‘a world class location, on your doorstep’ (Llewelyn-Davies Citation2000, 2). What exactly a destination was, and on whose doorstep, was implicit in the vision that followed. Tourists and business visitors would flock to the new conference centre, situated beside the new art gallery, the new theatre, and three new luxury hotels. There were to be marinas, yacht clubs, and 30,000 new homes. It was to emulate Barcelona’s waterfront, to somehow be comparable to Copenhagen, Vancouver and Stockholm too (Friday Citation2005). A later proposal for part of the site dreamt of an artificial island (comparisons to Dubai were made) complete with sandy beaches and an observation tower (Urban Realm Citation2006). Local authority planning officers ‘were falling off their desks, wondering whether to laugh’ at that idea, recalls one of them (see Figure ). Connected by a causeway to the shore, this island was to feature a 35-storey skyscraper including 25 floors of luxury flats, a 10-storey hotel and a rooftop restaurant (Wehner Citation2005). The UK’s second World Trade Centre (the first being in Canary Wharf, London) was supposed to open in Granton by 2004 (The Herald Citation2000). The license, which cost the city £100,000 in 2001, was renewed each year for a further £5,000 (The Scotsman Citation2010) before the company set up to oversee its construction was quietly dissolved in early 2014.

Figure 3: The vision for a ‘teardrop-shaped man-made island’ at Granton never made it past the digital drawing board. Source: Building Design 2004, 1.

Waterfront Edinburgh was never a neat case study of gentrification, and I do not want to imply that this word alone can tell us what happened here. This was not a project that entailed immediate displacement on a large scale, for most of the site was never residential. But it sits right up against several large public housing estates, and its end result would have been—and was explicitly intended to be—a catalyst for rising prices across the area. When I asked one of WEL’s project managers how their plans fitted in with the local community, the answer was immediate and blunt. ‘It didn’t.’ This was a plan that reached straight for the sheen of affluent urbanism. In this sense, it aspired to the ‘highest and best’ use of land first. All else would ostensibly follow. ‘The core strategy,’ wrote WEL (Citation2002, n.p.) with such confidence, was ‘to increase land values to the levels where the aspirations of the Master Plan become viable.’ To envisage such a trajectory in Granton implied a complete upheaval, a total transformation. To appreciate this, it is instructive to consider two very different representations of the area side-by-side. The first—Irvine Welsh’s novel Trainspotting—was published in 1993 and went on to sell over a million copies in the UK alone, was translated into 30 different languages and adapted into an internationally successful film three years later. The second—WEL’s opening gambit to prospective developers—was published six years after the film came out, and only a handful of people in the world remember it ever existed.

Trainspotting is by far the most famous representation of ‘Edinburgh’s dockside wastelands’ (Hemingway Citation2006, 331). The city portrayed on its pages is starkly divided, not only in terms of coexisting difference, but through overlapping relations of exploitation, fear, and resentment (Maley Citation2000). As the literary critic Lewis MacLeod (Citation2008, 95) points out, the characters of Welsh’s novel are ‘the concrete manifestation of a basic socioeconomic truth—that as capital clusters in one locus […] it becomes scarce in others.’ The novel, of course, is a fictional representation of space in the most literal sense, but so was WEL’s Master Plan. Whilst the first sought to represent the area as it existed (whether accurately or not), the second sought to represent a completely different place in the same space. In a strange twist of fate, the novel sought to depict poverty and made a poor man very rich; the Master Plan imagined a speculative future for a company that was soon bankrupt. The first frames Granton as somewhere nobody wants to live (Welsh Citation1999, 147), somewhere to escape from (395) and, ultimately, somewhere to die (314), whilst the second frames it as ‘one of the finest development opportunities in Europe’ (WEL Citation2002, 1). That both representations can contain some discursive ‘truth’ less than a decade apart is striking and speaks to the multiple ways in which territorial stigmatisation and the rent gap are linked (Gray and Mooney Citation2011; Kallin Citation2017).

Setting these two works side by side does not suggest that ‘story-telling’ takes precedence in determining the fate of the neighbourhood: the Master Plan imagined a radically different future, but it was not very imaginative. It was beholden to a narrow perspective of what was financially possible, conjuring up a blueprint that would look right at home among a rollcall of similar developments across the UK (Hatherley Citation2011). Harvey (Citation2006) notes that the dominance of finance capital rests on continuous acts of faith; here faith was a story told on high-gloss paper, with full-colour digital mock-ups of a future that was never to become real. As Searle (Citation2016) argues, ‘routes to accumulation’ in the urban landscape are often paved with stories that are just as speculative as the money that enables some of them to become true. The transformation of Granton required fictitious capital in the Marxian sense of the word—money invested before it is productively realised—but also new stories told about old parts of the city.

In those heady pre-crash days, the state’s role was intentionally difficult to pin down. WEL was a private company independent of state oversight, even though it remained essentially a ‘vehicle’ for the state to drive. Its budget derived from a strategy set at multiple scales of government, with Scottish Enterprise acting as a broker between the City of Edinburgh Council and the Scottish Executive (now the Scottish Government).Footnote2 The latter had the final say on whether to fund the project or not, but even here the veneer of competition is a strange act of institutional theatre, for Scottish Enterprise are themselves 100% funded by the Scottish Government. This setup was intended to take the risk so that ‘genuine’ private sector investors would not have to, echoing similar strategies of state involvement in Chicago (Weber Citation2002). Several WEL employees reproduced the idea that a private sector company would be a more attractive business partner simply because of its appearance. ‘If you’re trying to persuade banks, institutions, property companies, developers to do something, there is a perception they will be reticent to do that with a public body’, notes one employee (my emphasis); ‘let’s give the private sector something it can deal with,’ notes another. ‘The idea of setting up WEL,’ according to one of its architects, ‘was […] to be seen as more freethinking’ (my emphasis). In other words, at the birth of this project, the state was imbued with power by denying its presence. None of this is particularly surprising: neoliberalisation, broadly conceived, did not result in less state, but simply a different kind of statecraft (Peck Citation2001). In this stage, then, the rent gap was wide open, fuelled by two fictions—the potential future for the site and the ‘private-sector’ company that would bring that dream to life—and the state was economically and politically powerful. Or so it seemed …

2008–2017: From ‘potential’ to ‘wasteland’

Granton Gasworks Station is one of the only buildings left that gives a sense of the importance of this area’s industry to the wider growth of the city. When passenger services began here in the early 1900s, they were ‘third class only’ (Hunter Citation1992, 171), intended solely for the workers (numbering in their thousands) who would make the journey each day to what was then one of the largest gasworks in the world (Cotterill Citation1980). Shorn of the lines that served it, it has stood empty for several years, surrounded by a cluster of Portakabins that typify a quiet crisis of planning. Peer through the perimeter fence and you can see a white board that looks blank (see Figure ). But it is not blank—or it never used to be. It was put up to showcase bold plans for a new town centre, at the heart of which this slice of aesthetically pleasing ‘heritage’ was supposed to stand tall. After years of exposure to the Scottish weather, the contours of that vision have been reduced to a barely decipherable outline. It remained largely fiction. Built in parts, superseded in others, and mostly abandoned, its fading seems sadly appropriate. Whilst there are some notable success stories (such as Edinburgh College’s new campus), they are dwarfed in scale by the amount of land that remains empty.

In the mid-20th century, huge swathes of the land in this part of north Edinburgh was owned by the state (in various forms, not as one homogenous block). British Gas was a nationalised company, as was the Forth Ports Authority, and the Council owned the final third. The first two parts of this tri-partite ownership structure were quietly privatised in the 1990s, for when the utility companies were sold on the stock exchange, they took their landholdings with them. By the time the Waterfront project began, a solid third of the site was still owned by the Council, and this was transferred to WEL to match (in land values) funding from the Scottish Government. This third dissipated rapidly, in part because the whole aim of the plan was to sell off land, and several of the developers who purchased these parcels of land soon ran out of money. By 2013, there were nine separate landowners on-site, and the possibility of coordinating a plan between them was operationally impossible.

The fallout from the financial crisis exacerbated this dissipation of control, but the root of the problem lay earlier (mirroring the roots of the crisis). Counter-intuitively, the lucrative potential value of the land appears to have played a substantial role in killing off the realisation of that potential. A former WEL employee recalls with bitter irony that ‘property values were going up too high too quickly.’ As a result, British GasFootnote3 and Forth Ports ‘refused to sell, at any price’ and were also reluctant to cooperate. One of WEL’s (several) chief executives considers the decision not to push ahead with a compulsory purchase to have been ‘a terrible, terrible mistake’ that presented an insurmountable problem. As a planner who worked closely with the WEL team, Calum sounds exasperated when he bemoans that ‘you had three different landowners, three different property companies, three different plans!’ The original Master Plan was reduced to being ‘just a nice thing on the wall. There was no pressure to follow it.’ Shortly after its formation, it became apparent that WEL had neither the power nor the money to deliver what it promised (or what its more idealistic employees wanted). ‘The Waterfront’ on paper was a cohesive vision; in reality, it was a disparate collection of real estate investment sites, whose landowners were pushed apart by their shared vision of future profits.

By the mid-2000s, independent mediators were trying to bring the three landowners together to discuss a coordinated approach. ‘Over four days we tried to hammer out a vision with architects and financial backers,’ Kieran tells me. ‘It was one of the most interesting, challenging, fruitless things I’ve ever done.’ Dylan, then employed to oversee the city’s urban design at a strategic level, recalls with dismay that ‘each individual landowner and their consultants had involved little bits and pieces’, focussed entirely on ‘how they could squeeze as much profit as possible out of their land parcel.’ To compound the problem, WEL’s status as an avowedly ‘private’ company meant that the local authority was obliged to treat it equally as just another developer on site. This removed any ability to fast-track their planning applications, guarantee approval, or reject contradictory plans on the basis of incompatibility (this was a particular source of frustration for those WEL employees on secondment from the council planning office, who essentially traded roles depending on which office they were assigned to that day). WEL was left in an awkward position that is reflected on the site to this day.

Nothing illustrates this more strikingly than the Avenue that bends. Designed to be the central artery of the entire site, Waterfront Avenue was supposed to cut a straight line across the landscape. If you walk along it today, you find yourself walking in a straight line for a few hundred meters before curving abruptly to the left. From there, the Avenue dissipates into a service road at the back of a large Morrisons supermarket. This lends the site an immediately disorientating feel, all the more noticeable because the straight section is so wide and prominent, confidently leading to nowhere. Why? Because the local authority gave Scottish Gas planning permission to build an office block in ‘exactly the wrong place’, to quote one of WEL’s original board members. The competition between developers, overlaying the contradiction between different arms of the state, became an enduring contradiction in the landscape (see Figure ). In 2003, WEL’s first Chief Executive resigned in frustration. His successor was a controversial figure, who occupied the position until the eve of the financial crisis. The stories that coalesce around him—universally hated by my interviewees—are undoubtedly libellous and highlight how the company’s structure was so beholden to ‘private sector efficiency’ that an astonishing array of checks and balances were never effectively applied.

Figure 5: One of several new roads constructed just before the financial crisis to access housing which was never built. It ends abruptly where it hits the northern boundary wall of the former Gasworks (the road was built by WEL; the wall was owned by British Gas). The land on the left is now occupied by the Social Bite Village, an innovative charity project that provides ‘tiny houses’ for homeless people. Source: author 2015.

When the financial crisis hit, all the lucrative ‘potential’ that was powering this project seemed to evaporate. In the council’s own words,

over the past two decades, development […] has been piecemeal and un-coordinated due to fragmented land ownership, high infrastructure costs, business cases built on overly-optimistic assumptions, and the 2008 financial crisis which brought the vast majority of housebuilding to a halt. (Housing and Economy Committee Citation2018, 3)

Figure 6: A former WEL sign that used to read ‘DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY’. Source: Leonor Estrada Francke 2020.

The heartbeat of the project was simultaneously immensely powerful and remarkably fragile: rising land values took the form of both means and end (or chicken and egg), so when the financial crisis began to unfold, the whole project lurched to a dramatic standstill. The Chief Executive of Forth Ports, one of the major landowners, went on record in early 2009 to say that their land was now ‘probably worth less than nothing.’ £220 million was wiped off the value of their waterfront landholdings almost overnight (The Scotsman Citation2009). WEL remained tight-lipped about their losses in terms of land values, but there is nothing to suggest they would not have been on a similar scale.

In other words, by the time the dust settled from the financial crisis, the principal vehicle of the state on Edinburgh’s waterfront had run out of money and been stripped of its landholdings, its personnel, and (crucially) the confidence and narrative essential to its performance. What was left was a disconcerting landscape of stasis, what Vradis (Citation2014) would call a ‘crisis-scape’, where the financial crisis takes on a particular geography. Unfinished pieces of infrastructure litter the site. There are roads that lead to nowhere, driveways into the water, and plots for luxury flats marked out but left abandoned. High fences still guard what looks like nothing. Brand new streetlights have shone onto emptiness for ten years. Even the signs that warn of guard dogs were transformed into lies by this crisis: one former employee tells me with great sadness that the dogs were quickly put to death, one more expenditure that could be struck off the balance sheet. It is in this context that the idea of ‘state-led gentrification’ seems to fade away completely. The state could not lead, and gentrification did not occur. The rent gap was drawn wide open with such confidence but never closed. The landscape felt almost frozen in time (McClanahan Citation2014). In late 2014, I asked a former board member of WEL why the waterfront did not look anything like those idealistic plans. He grinned, and insisted I changed my question: ‘It doesn’t yet look like that.’

2017 Onwards: from ‘wasted potential’ back to which future?

As I later learned, a crisis-scape can be deceptive. On the surface, it looks like everything had stopped, but this was never quite true. In January 2008, just before the financial crash, a property developer bought one of the plots of reclaimed land on Granton Harbour for just over £3 million. As the severity of the crisis became apparent, this company filed for bankruptcy. The plot lay empty for several years. Then, in 2012, a secretive consortium called Sapphire Land Ltd. acquired the land. Registered offshore on the British Virgin Islands, a tax haven par excellence, they hoovered up six neighbouring plots at the same time and kept them all empty (Wightman Citation2012). This is a subtle change, but an important one. The land was now being held intentionally empty, a classic case of land-banking, where future exchange value takes such precedence over present use value that it appears to annihilate the latter altogether (though there are always cracks in this dichotomy; whenever I visited, there were usually people walking their dogs, windswept and surrounded by piles of rubble). This feeling of stasis was deceptive: all the while, that powerful relation between realised ground rent and potential ground rent was rolling along, ownership changed, plans changed, and dreams of what could be possible were slowly forged from the shadows of crisis. As one of the council planners astutely pointed out to me, the site was ‘probably in a better place because land values ha[d] been depressed’ by the crisis. What stopped the old plan is also what made new plans viable. Though seemingly abandoned to the elements, the Granton Harbour plots now embodied what Harvey (Citation2011, 181) calls ‘landed developer interests’, where the most useful role the land can play is to sit empty until the time is perceived to be right. That time, it seems, is now.

The site of the original Waterfront Edinburgh project is now effectively split in three, on which divergent visions of the future emerge. On the first third—what was once Granton Harbour—a series of high-profile development proposals are together branded Edinburgh Marina. Their promotional material reads like a trip back to the future, a heightened rehash of the original plan.Footnote4 A luxury hotel and luxury clubhouse sit up against gated residential apartments with 24/7 private security, right on the edge of what remains one of the poorest neighbourhoods in the city.Footnote5 A company called ‘Edinburgh Marina Ltd.’ are credited with this resuscitation, arriving like saviours to lift the area into a bright and glossy future. Their logo sports the date ‘1836’, despite having been incorporated in 2015.Footnote6 In fact, no company with the name ‘Edinburgh Marina Ltd.’ legally exists: instead, there is a chain of similarly named companies that each own each other, all of which are nominally headquartered in Edinburgh or London but are for tax purposes based in Suite 131 on the first floor of an unremarkable office block above a bus station in St. Helier on the Isle of Jersey, which happens to be another tax haven par excellence.Footnote7 Such practices are far from unique. As Christophers (Citation2018, 191) notes, in the thirteen years prior to 2012, some 95,000 companies were established in tax havens ‘specifically to hold British properties’, taking the total value of UK property registered offshore to £170 billion and counting.

The ‘total’ luxury of the Edinburgh Marina plan imposes a certain order onto the landscape (at least in its digital mock-ups) that is strikingly absent from the middle third that was the centre of the original WEL plan. Cross the West Harbour Road with the last glimpse of the water behind you, and you find yourself amidst light industries (a garden shed shop, a safe storage warehouse, a private bus garage, and so on), many of which were on temporary contracts throughout the WEL years, airbrushed out of the visions for this neighbourhood but still clinging to life. They represent all that is left of what was once designated the Granton Industrial Action Area (Department of Planning Citation1994), under which the vacant land was considered suitable ‘only for industrial and employment purposes’ (1). Within six years, that plan was superseded by its complete opposite (a miraculous transformation broadly in line with the ‘neoliberalisation’ of urban policy itself). Head up to Waterfront Avenue and you pass a series of newbuild housing blocks, some finished just before the crisis, others constructed slowly in its shadow by housing associations, not-for-profit (though increasingly for-some-profit) housing providers who were willing to shoulder the risk where others were not (see Figure ). Follow the grandiose sweep of the Avenue that bends, and you find yourself on the final third of the site, home to the former gasworks. Here, too, things have changed significantly, but quite differently. In March 2017, the City of Edinburgh Council negotiated with National Grid (British Gas) to purchase all 66 acres of the remaining vacant land on this site for the not-insignificant sum of £9 million.Footnote8 The purchase was completed a year later, taking the council’s waterfront landholdings back up to over 120 acres. This is a rare inversion of the dominant tendency towards land privatisation across the UK (Christophers Citation2018) (see Figure ).

Figure 7: ‘55 Degrees North’ is a for-profit (sale) development from Places for People housing association, one of several newbuilds to rise over long-vacant land in recent years. Source: Leonor Estrada Francke 2020.

Edinburgh’s waterfront thus stands at the dawn of ‘regeneration’ once again (with competing grand visions up against each other once again). In strategic terms, alongside (and juxtaposed against) the grandiose Marina plans, the Council (re)assumes a central role, both as coordinating authority and as landowner, combining the newly acquired site with all the former WEL land, which has been unceremoniously transferred back ‘in house.’ Their priorities are, on the surface, quite distinct from the tenor of the initial WEL plans: ‘affordable’ housing is now the lead issue, with 35% of the housing on-site to be procured by the council themselves (in advance of any private sector housing) and constructed to a net zero carbon emission standard.Footnote9 Coupled with minimal car parking, a renewed emphasis on biodiversity and public transport, the sustainable credentials of these plans are substantial. So too is the emphasis on creating ‘high quality new jobs’ (Turner & Townsend Project Management Limited Citation2020, 6), an aspect conspicuously (and damagingly) absent from earlier plans. Even more ambitious is the link to a Regional Housing Programme that seeks to develop ‘a blueprint for UK wide public sector procurement of affordable housing’ (Policy and Sustainability Committee Citation2020, 11). This idealism is still underpinned by an aggressive growth strategy at the regional scale, tied to targets set out by the Scottish Government through the City Regional Deal. The symbiotic link between economic growth and social wellbeing has not been unravelled, but the order of priorities is markedly more balanced than it was in the early days of WEL. As a second attempt, lessons have clearly been learnt: this begins to look more like a renewed form of social democratic planning (with all its attendant contradictions and limitations) than the resuscitated zombie of neoliberalism (Peck Citation2010). Circumstances may still clip the wings of this vision (see Figure ).

Figure 8: Construction continues apace on these council houses (for ‘Mid-Market Rent’, which equates to 80% of market rent). The bridge was designed to lead to a luxury property development and has been fenced off for over a decade. The shallow water channel is constructed on reclaimed land above what was once a working dock, a neat illustration of ‘the recuperation of history […] simply reproduced as pastiche’ (Harvey Citation1990, 82). Source: author 2020.

![Figure 8: Construction continues apace on these council houses (for ‘Mid-Market Rent’, which equates to 80% of market rent). The bridge was designed to lead to a luxury property development and has been fenced off for over a decade. The shallow water channel is constructed on reclaimed land above what was once a working dock, a neat illustration of ‘the recuperation of history […] simply reproduced as pastiche’ (Harvey Citation1990, 82). Source: author 2020.](/cms/asset/a40f8de8-5cd0-4515-87e3-6499fa7b455d/ccit_a_1976559_f0008_oc.jpg)

The publication of this ambitious vision casts a 15-year timespan into the future. It resets the clock of potential after the 15-year timespan over which the last ambitious vision petered out. This reset occurs at a particularly fascinating juncture: it is perceived as sufficiently far enough after the 2008 financial crisis to commemorate ‘recovery’; sufficiently far enough ahead of the already-unfolding ecological crisis to be comfortingly ‘sustainable.’ On both fronts, the presentation of these plans may be deceptive (the campaign group Climate Central suggest most of the site will be permanently under water or at least prone to frequent flooding by 2050), but it is through their presentation that both promises are engineered to become true.

The fact these plans were published in late February 2020, just as the UK entered lockdown due to COVID-19, reiterates the centrality of crisis to the shifting rhythm of potential values. At the point of writing, it is impossible to foresee the extent of the economic crisis that will unfold as a result of this virus, but all signs point to it being at least as dramatic as 2008 (Wolf Citation2020). I will not attempt to predict the impact of this future: for my purposes here, the erratic timeline of potential through to crisis through to potential (and back again?) serves to reiterate the difficulty of closing the rent gap in sites that are considered risky or marginal. This reasserts the centrality of the state’s role (‘infrastructure first’ is the mantra of these new plans) but simultaneously highlights the fragility of the power underpinning that role. It also highlights that the dynamic of potential vs. realised profits on any given piece of land should not be thought of as a simply economic relation, one that takes place ‘above’ or ‘outside’ the world of discourse, power, and struggle, but is rather always embroiled in the human relationships that make that aspirational ‘gap’ feel real enough to invest in. It is worth recalling that, as a response to the abstractions of mainstream economics, Smith’s approach to theorising gentrification has contained the kernel of this ‘more-than-economic’ vision since its inception (Slater Citation2012). The rent gap was built on a theory of capitalism beholden to Marx, thus it carries at its heart an understanding of crisis not as an aberration of capitalism but a fundamental facet of its ‘normal’ operation. This was strikingly clear in Smith’s (Citation1982) own work, where the see-saw between devalorisation and revalorisation was animated by the dynamic relationship between potential and its stark opposite.

What exactly will come to pass on Edinburgh’s waterfront—now seemingly beholden to such distinct visions—remains to be seen. As the story of WEL itself demonstrates, nothing should be taken for granted. Already antagonism between the landowners rears its head: the council recently spent £27,000 on legal fees trying to force ‘Edinburgh Marina’ to reapply for planning permission and contribute more to the infrastructure costs (Matchett Citation2020); the court ruled in the developer’s favour (Scottish Legal News Citation2020). Two different futures have been incubated down on the waterfront: one has been lifted straight from the catalogue of capitalist urbanism; the other forges a subtly new direction for municipal housing provision, a step-change in the scale with which the local authority tries to more directly tackle the housing and ecological crises. Both are reactions to the last financial crisis, the fallout from which will be traceable in Granton for decades to come.

The gap between potential and profit

In the early 2000s, this looked like a gilded case of ‘state-led gentrification’. In the years since, gentrification has not occurred, and the capability of the state to lead that process has been sharply undermined. Writing from Athens, Alexandri (Citation2018) makes an observation that resonates on Edinburgh’s waterfront: it is not only intentionally that state power can aid the revalorisation process. State failure can be lucrative, albeit over a longer and less predictable period. The rent gap has always relied on the passing of time, imagined at its simplest as ‘time from construction date’ (Smith Citation1979). As Hammel (Citation1999, 131) notes, the original ‘hypothesis provides no specific guidelines in the timing of development of rent gaps,’ and his own attempt to substantiate those guidelines revealed a very mixed picture (there was, in short, no predictable relation of timing between disinvestment and reinvestment). In this case, however, a lengthy period of time—two decades and counting—has elapsed between the closure of the rent gap being conceived and the point at which the ‘potential ground rent’ actually becomes the new ‘realised ground rent.’ The drawing out of this process allows us to disaggregate the smooth curves of the rent gap model, to look anew at some of its key transition points.

In abstract economic terms, the rent gap has been open here for decades, but in discursive terms, it has opened and closed and opened again multiple times since the turn of the millennium, each time following the rhythm of a slightly different set of calculations, a reconceived planning framework, or the whims of a new landlord. The relationship between the two (what is said to be the potential value and what the potential value actually is) is so tight as to be impossible to tease apart. As I have argued elsewhere (Kallin Citation2017), this demonstrates the importance of seeing ‘potential value’ as an imagined potential, and one that is often constructed quite wistfully on uncertain ground. Closing the gap (achieving that potential) is not a done deal: the transition to revalorisation in Granton began in the late 1990s when the area was earmarked for substantial reinvestment and its discursive framing was abruptly upturned, but that transition is still in motion (and may still fail). Framing potential as imaginary, constructed and performed, helps to further denaturalise the power of its appeal, to focus on who frames what futures as realistic under the circumstances.

The relation between ‘capitalised ground rent’ and ‘potential ground rent’ is not simply a case of the former chasing to keep up with the latter. The dancing mirage of ‘potential’ interweaves with the hard calculus of actually possible profit. Sometimes the two overlap, sometimes one pulls the other up or down quite dramatically. In this case, perhaps controversially, I believe it is instructive to consider the rent gap model separately from the gentrification debates. I do not mean to divorce the ideas entirely: given the focus of my paper, it may not surprise the reader to know that I find the rent gap remains a compelling explanation of gentrification, but, as I hope I have shown, it remains a fascinating lens to consider projects in which gentrification does not occur within a timespan that lends itself to observational certainty. In these contexts, it still encourages us to see how devalorisation and the promise of revalorisation are intrinsically linked; how the logic of gentrification can be observed even when the end-result is not (yet). This gap between speculation and capitalisation should not be romanticised, but it should be taken seriously as a period of time in which the agency of creating potential comes to the fore. ‘Gentrification’, for Smith (Citation1979), is what occurs when the rent gap model plays out in a particular way, but it is not a predetermined fate within that dynamic cycle of urban land from disinvestment back to reinvestment. The spatialisation of the profit motive contains many weak points (as Smith well knew). These are also points of possibility, for if the victory of one vision of potential—what is often referred to as the ‘highest and best use’—over others fails, then the space for alternative futures is left wide open and the possibility of a more democratic and sustainable definition of ‘best use’ can emerge. As a tool that was designed to help us overcome the process that it sought to describe, the smooth working of the rent gap should not be fetishised or presumed. Its failure, both for the hardships it may cause and the possibilities it may enable, should be considered as part of the model’s rationality, not a perversion of its logic.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Leonor Estrada Francke for the use of her photos, Frank Thomas for his mapping skills, Tom Slater and Neil Gray for their continued support, two anonymous reviewers for their encouraging and helpful feedback, the City editors for their attention to detail, and all the interviewees for being so forthright.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Hamish Kallin

Hamish Kallin is a lecturer in Human Geography in the School of Geosciences at the University of Edinburgh. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Interviews cited in this paper were conducted in late 2014 with a range of professionals involved in the planning and implementation of the original Waterfront Edinburgh Limited-led project. All names have been changed and roles anonymised.

2 Following devolution in 1999, the Scottish Parliament was reconstituted as a devolved body within the UK, with the Scottish Executive as its legislative body. Whilst some powers (such as defence and foreign policy) are reserved for the UK government in Westminster, many (including housing and planning policy) are devolved completely. Following their election victory in 2007, the Scottish National Party (SNP) took the decision to rename the Executive the Scottish Government.

3 Legally speaking, it is not correct to say that “British Gas” owned any land on the waterfront, as it was owned through multiple subsidiaries. However, as all of those subsidiaries were owned by British Gas, and in the interests of clarity, I have used the shorthand “British Gas”.

4 See https://edinburgh-marina.com.

5 Granton South and Wardieburn remains one of the 5% most deprived wards in Scotland according to the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation 2020. Six other wards in the local area remain in the 20% most deprived category (data from https://simd.scot).

6 For the sake of local historical accuracy, I should note that it was in 1836 that the construction of Granton Harbour was given parliamentary consent (Somner Citation2004), so there is some vague relevance to the date at least. The Harbour has had a small marina since the 1880s, but that has always been operated by a local yacht club, who are not a property development company.

7 Information gleaned from the Companies House website: https://companieshouse.gov.uk

8 Figure obtained through a Freedom of Information request. Request no. 18656. Received: 24/04/2018, Resolved: 17/05/2018.

9 It is important to note that “affordable” housing in Scotland means multiple things. It can, for example, include accommodation built and rented by the local authority or housing associations at various levels (mid-market rent or social rent), as well as multiple forms of home ownership subsidised through shared-ownership systems of debt financing. The preferred strategy tends to be a mix of these tenures.

References

- Alexandri, Georgia. 2018. “Planning Gentrification and the ‘Absent’ State in Athens.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 42 (1): 36–50. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12566

- Christophers, Brett. 2018. The New Enclosure: The Appropriation of Public Land in Neoliberal Britain. London: Verso.

- Citylets. 2018. Citylets Quarterly Report, Issue 47. https://www.citylets.co.uk/research/reports/pdf/Citylets-Quarterly-Report-Q3-2018.pdf.

- City of Edinburgh Council. 2014. Poverty and Inequality Data in the City. http://www.edinburgh.gov.uk/download/meetings/id/42260/item_5_3_poverty_and_inequality_data_in_the_city.

- City of Edinburgh Council Development Committee. 1997. North Edinburgh Waterfront: A Report Presented to a Meeting of the City of Edinburgh Economic Development Committee. Edinburgh: City of Edinburgh Council.

- Cotterill, M. S. 1980. “The Development of Scottish Gas Technology 1817–1914: Inspiration and Motivation.” Industrial Archaeology Review 5 (1): 19–40. doi: https://doi.org/10.1179/iar.1980.5.1.19

- Department of Planning. 1994. Granton Master Plan: Draft Master Plan for the Granton Industrial Action Area. Edinburgh: City of Edinburgh District Council.

- ECA International. 2019. “Edinburgh Remains Most Liveable UK City for European Expats.” https://www.eca-international.com/news/february-2019/edinburgh-remains-most-liveable-uk-city-for-europe.

- The Edinburgh Branch of the Geographical Association. No date. An Atlas of Edinburgh. Edinburgh: The City Litho Co.

- Friday, Robert. 2005. “Waterfront Revival Begins in Granton.” Planning Resource. http://www.planningresource.co.uk/news/482945/.

- Gracie, James. 2003. Stranger on the Shore: A Short History of Granton. Glendaruel: Argyll Publishing.

- Gray, Neil, and GerryMooney. 2011. “Glasgow’s New Urban Frontier: ‘Civilising’ the Population of ‘Glasgow East’.” City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action 15 (1): 4–24. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2010.511857

- Hammel, Daniel J. 1999. “Gentrification and Land Rent: A Historical View of the Rent Gap in Minneapolis.” Urban Geography 20 (2): 116–145. doi: https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.20.2.116

- Harvey, David. 1990. The Condition of Postmodernity. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

- Harvey, David. 2006. The Limits to Capital. London: Verso.

- Harvey, David. 2011. The Enigma of Capital and the Crises of Capitalism. London: Profile Books.

- Hatherley, Owen. 2011. A Guide to the New Ruins of Great Britain. London: Verso.

- Hay, W. G. 2011. Our Changing Waterfront. Edinburgh: W. G. Hay.

- Hemingway, Judy. 2006. “Contested Cultural Spaces: Exploring Illicit Drug-Using Through Trainspotting.” International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 15 (4): 324–335. doi: https://doi.org/10.2167/irg198.0

- The Herald. 2000. “A World Trade Centre in Scotland.” http://www.heraldscotland.com/sport/spl/aberdeen/a-world-trade-centrein-scotland-1.210453.

- Housing and Economy Committee. 2017. The EDI Group Ltd - Transition Strategy. https://democracy.edinburgh.gov.uk/Data/City%20of%20Edinburgh%20Council/20180531/Agenda/item_81_-_the_edi_group_-_transition_strategy.pdf.

- Housing and Economy Committee. 2018. Granton Waterfront Regeneration Strategy. https://nen.press/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Item_7.2___Granton_Waterfront_Regeneration_____Delivery_Strategy.pdf.

- Hunter, D. L. G. 1992. Edinburgh’s Transport: The Early Years. Edinburgh: Mercat Press.

- Kallin, Hamish. 2017. “Opening the Reputational Gap.” In Negative Neighbourhood Reputation and Place Attachment: The Production and Contestation of Territorial Stigma, edited by Paul Kirkness and Andreas Tije-Dra, 102–118. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kerr, Derek. 2005. “Preparing for the 21st Century: The City in a Global Environment.” In Edinburgh: The Making of a Capital City, edited by Brian Edwards and Paul Jenkins, 204–216. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Krijnen, Marieke. 2018. “Gentrification and the Creation and Formation of Rent Gaps.” City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action 22 (3): 437–446. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2018.1472461

- Lan, Cassidy I-Chih, and Chen-JaiLee. 2020. “Property-Led Renewal, State-Induced Rent Gap, and the Sociospatial Unevenness of Sustainable Regeneration in Taipei.” Housing Studies 36 (6): 843–866.

- Llewelyn-Davies. 2000. Masterplan for Waterfront Granton: Draft Master Plan. London: Llewelyn-Davies.

- López-Morales, Ernesto. 2010. “Real Estate Market, State-Entrepreneurialism and Urban Policy in the ‘Gentrification by Ground Rent Dispossession’ of Santiago de Chile.” Journal of Latin American Geography 9 (1): 145–173. doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/lag.0.0070

- MacLeod, Lewis. 2008. “Life among Leith Plebs: Of Arseholes, Wankers and Tourists in Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting.” Studies in the Literary Imagination 41 (1): 89–106.

- Maley, Willy. 2000. “Denizens, Citizens, Tourists, and Others: Marginality and Mobility in the Writings of James Kelman and Irvine Welsh.” In City Visions, edited by DavidBell and Azzedine Haddour, 60–72. Harlow: Prentice Hall.

- Matchett, Conor. 2020. “Transparency Questions Raised as Reasons for Edinburgh Council’s £12 Million Legal Fee Bill to Remain Secret.” Edinburgh Evening News. https://www.edinburghnews.scotsman.com/news/politics/council/transparency-questions-raised-reasons-edinburgh-councils-ps12-million-legal-fee-bill-remain-secret-2534065.

- Mathews, Peter, and Madhu Satsangi. 2007. “Planners, Developers and Power: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the Redevelopment of Leith Docks, Scotland.” Planning Practice and Research 22 (4): 495–511. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02697450701770043

- McClanahan, Angela. 2014. “Archaeologies of Collapse: New Conceptions of Ruination in Northern Britain.” Visual Culture in Britain 15 (2): 198–213. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/14714787.2014.935129

- McCrone, David. 2018. “Lost in Leith: Accounting for Edinburgh’s Trams.” Scottish Affairs 27 (3): 361–381. doi: https://doi.org/10.3366/scot.2018.0248

- Peck, Jamie. 2001. “Neoliberalizing States: Thin Policies/Hard Outcomes.” Progress in Human Geography 25 (3): 445–455. doi: https://doi.org/10.1191/030913201680191772

- Peck, Jamie. 2010. “Zombie Neoliberalism and the Ambidextrous State.” Theoretical Criminology 14 (1): 104–110. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480609352784

- Policy and Sustainability Committee. 2020. Granton Waterfront - Leading the Way in Sustainable Development: Programme Delivery Plan. https://democracy.edinburgh.gov.uk/documents/s14342/Item%207.12%20-%20Granton%20Waterfront%20Leading%20the%20Way%20in%20Sustainable%20Development%20Programme%20Delivery%20Plan.pdf.

- The Scotsman. 2009. “Waterfront Woe: ‘Forth Ports Is Not Alone in Its Difficulties.’” http://www.scotsman.com/news/waterfront-woe-forth-ports-is-not-alone-in-its-difficulties-1-1195474.

- The Scotsman. 2010. “World Trade Centre Site Is Centre of Attention.” http://www.scotsman.com/news/world-trade-site-is-centre-of-attention-1-1309731.

- Scottish Legal News. 2020. “Edinburgh City Council Loses Planning Appeal over Waterfront Development.” https://www.scottishlegal.com/article/edinburgh-city-council-loses-planning-appeal-over-waterfront-development.

- Searle, Llerena Guiu. 2016. Landscapes of Accumulation: Real Estate and the Neoliberal Imagination in Contemporary India. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Slater, Tom. 2012. “Rose Street and Revolution: A Tribute to Neil Smith.” ACME: An International E - Journal for Critical Geographies 11 (3): 533–436.

- Slater, Tom. 2014. “Unravelling False Choice Urbanism.” City 18 (4–5): 517–524. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2014.939472

- Slater, Tom. 2017. “Planetary Rent Gaps.” Antipode 49 (Suppl. S1): 114–137. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12185

- Smith, Neil. 1979. “Toward a Theory of Gentrification: A Back to the City Movement by Capital, Not People.” Journal of the American Planning Association 45 (4): 538–548. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01944367908977002

- Smith, Neil. 1982. “Gentrification and Uneven Development.” Economic Geography 58 (2): 139–155. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/143793

- Somner, Graeme. 2004. The Port of Leith & Granton. Stroud: Tempus Publishing Limited.

- Teresa, Benjamin F. 2019. “New Dynamics of Rent gap Formation in New York City Rent-Regulated Housing: Privatization, Financialization, and Uneven Development.” Urban Geography 40 (10): 1399–1421. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2019.1603556

- Turner & Townsend Project Management Limited. 2020. Programme Delivery Plan: Granton Waterfront Programme. Edinburgh: City of Edinburgh Council.

- Urban Realm. 2006. “Thorny Issues on the Waterfront.” Urban Realm. http://www.urbanrealm.com/features/19/Thorny_issues_on_the_waterfront.html.

- Vradis, Antonis. 2014. “Crisis-Scapes Suspended.” City: Analysis of Urban Trends, Culture, Theory, Policy, Action 18 (4–5): 498–501. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2014.949095

- Waterfront Edinburgh Limited. 2002. A Capital Opportunity: One of the Finest Development Opportunities in Europe. Edinburgh: Waterfront Edinburgh Limited.

- Waterfront Edinburgh Limited. 2017. “Directors’ Report and Financial Statements for the Year Ended 31 December 2016.” Companies House.

- Weber, Rachael. 2002. “Extracting Value from the City: Neoliberalism and Urban Redevelopment.” In Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe, edited by Neil Brenner and Nik Theodore, 172–193. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Wehner, Piers. 2005. “Sea-Change for City.” The Estates Gazette, 15th January: 43–45.

- Welsh, Irvine. 1999. Trainspotting. London: Vintage.

- Wightman, Andy. 2012. “Edinburgh Waterfront in the British Virgin Islands.” Land Matters. http://www.andywightman.com/archives/1867.

- Wolf, Martin. 2020. “Coronavirus Could Be Worst Economic Crisis since Great Depression.” Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/video/fbaaa133-c94d-4e35-844b-bfde5f6a0635.