Abstract

In this article, we study the ongoing redevelopment of post-war, modernist residential area Rosengård, located in Sweden’s third biggest city Malmö. We show how a planning and design strategy for this area has come to focus on a ‘compact city’ typology in line with Malmö’s strategy for creating a ‘near, dense, green and mixed city’. Such compact city typology emphasizes high density, urbanity, proximity and mixed-use as key values for renewal, but also threatens the green spaces in areas designated for densification. This article illustrates how renewal plans for modernist residential areas with generous green space provision also ensure dispossession of residents’ rights to green space. Our analysis highlights how this planned dispossession is preceded by a discursive dispossession carried out by the way urban planning represents these spaces. The Rosengård case illustrates how a compact city vision imposed on marginalized modernist areas co-emerges with new forms of expert knowledge which both ‘unmaps’ existing green spaces and defines them as problematic and requiring interventions. The article highlights the important, but not yet sufficiently explored, dispossession of the right to public green space in racialized poor peripheries of Northern cities already facing intense displacement pressure. We argue that this type of renewal of modernist areas not only tends to neglect mapping important public spaces and uses of space, but actively produces blind spots by deploying a compact city planning epistemology which necessarily undermines rights to green space in the city and should put into question the compact city as the default sustainability fix.

Introduction

Dispossession of people’s right to a place in the urban environment is one of the many urgent questions facing city dwellers today. Around the world residents, activists and scholars alike draw attention to the shifting forms and dynamics of displacement as an acute and accelerating form of urban, spatial injustice (Baeten et al. Citation2017; Yiftachel Citation2020; Pull and Richard Citation2021). Despite decades of neoliberal claims about rolling back the social state, dispossession of the right to a home is in many cases intricately managed from above. Planned dispossession stretches from the violence of ‘slum clearing’ unleashed in cities across the global south (Ghertner Citation2015) to carefully choreographed ‘urban renewal projects’ in northern cities designed to purge the poor (Baeten and Listerborn Citation2015; Ferreri Citation2020). Dispossession thus takes many forms, from silent violence to open cruelty and from meticulously planned to the chaotic unleashing of profit-seeking real estate giants.

With this article we highlight a mode of planned but hidden urban dispossession taking place in the shadow of the more spectacular, and more well researched, ways that urban dwellers are displaced. We argue that planned renewal strategies impose a ‘compact city’ typology on post-war modernist residential areas dominated by multi-unit dwellings in the urban global north, which in practice often relies on seizing public green spaces within these areas for redevelopment. Today, increasing the density of cities has become an almost ‘common-sense’ planning idiom tied to notions of sustainable urban futures, and a way to actively reimagine and craft urban worlds (Pérez Citation2020; cf. Tunström Citation2009). Yet, this kind of renewal, increasingly filed under the broader rubric of ‘densification’ (see McFarlane Citation2020), is in practice premised on the dramatic appropriation of green spaces and other public amenities within residential areas to make space for new housing. Even when residents of these areas manage to resist outright displacement associated with renewal of working-class housing areas such as rent hikes (Baeten et al. Citation2017) or ‘decanting’ (Ferreri Citation2020), those that remain find themselves living in a dramatically remade landscape.

Unlike those that study relations between pro-market developer groups and the pioneering ‘new urbanist’ proponents of a compact city (MacLeod Citation2013; see also McFarlane Citation2016), our research focuses on how dispossession of the right to everyday green spaces through ‘densification’ of post-war residential areas might be planned processes. We approach this issue by studying the ‘densification’ plans for the large residential estate Rosengård, a relatively deprived and highly stigmatized area built in 1962–1972 and located in Sweden’s third largest city Malmö. There are countless ‘densification’ plans for similar areas in Malmö, and many other cities and towns across Sweden, which has led to veritable waves of grassroots resistance organized by residents still largely unrecognized in urban geography (cf. Kärrholm and Wirdelöv Citation2019). What makes Rosengård a particularly useful case to study is that the planning practices associated with the compact city paradigm are unleashed as part of a municipal strategy to completely rebrand one of Scandinavia’s most stigmatized places (Gustafsson Citation2021), making the effects of ‘densification’ more clearly visible than in most other potential cases.

Our ambition is to identify in which ways residential areas targeted by densification and renewal are mapped by an urban planning bureaucracy increasingly preoccupied with the compact city. This approach is inspired by scholars who suggest that the knowledge-making technologies of planning matter profoundly for how this mode of making space plays out (see Roy Citation2005, Citation2009; Ghertner Citation2015; Bénit-Gbaffou Citation2018). By arguing that a new mode of charting public space has co-emerged with the rise of the compact city paradigm, we further wish to underscore the concrete effects of the blind spots of expert knowledge production. Thus, we agree with authors like Mara Ferreri (Citation2020) suggesting that epistemic violence is an ‘othering that den[ies] the cultural intelligibility of people affected by municipal dispossession’ but are primarily interested in the role of this selective knowledge in enabling new forms of development unencumbered by care for residents’ everyday uses of space.

Densification in Rosengård is related to a whole range of causes, like financialization of housing and land (Gustafsson Citation2021; Polanska Citation2020) and geographic racialization of social issues as ‘problem spaces’ (Pries Citation2020; see also Dikeç Citation2007). Still, the ‘discursive dispossession’ we identify in the formal planning process precede and make possible the planned appropriation of public spaces and amenities for redevelopment, making it a fundamental part of how financialization is worked out in this kind of urban landscape. By tracing the nitty gritty of such mode of planning knowledge at work, this technical expertise might be opened up to forms of political contention and spotlight how rights to public green spaces in the city are systematically being weakened in certain kinds of locations.

We approach this issue by analyzing how expert knowledge about green space in the Rosengård area is produced in formal planning documents. Our ambition is to scrutinize the discursive planning practices which enable, and seemingly ensure, a ‘dispossession by densification’ where the right to green space of the people living in Malmö’s post-war residential areas systematically are rolled back by the public planning processes. Uncovering the seemingly neutral erasures this planning expertise is premised on might also, we hope, be a part of a larger reconsideration among urban planners of the compact city as the uncritically adopted standard template of ‘sustainable’ urbanism.

The compact city and its planning epistemologies

Visions of the future, and their relation to planning practices, has long played a foundational role in urban studies and planning scholarship. In recent decades, a whole host of related versions of what might be described as the compact city has emerged as the predominant vision in urban planning. Compact city visions have complex aesthetic, political and economic origins and are articulated with a range of other planning ideals today, but it was perhaps most powerfully lobbied for by the self-avowed ‘new urbanists’ who from a critique of modernist planning and suburbanization in the 1980s began to put forward neo-traditionalist ideals of the city. A core theme of new urbanism is the emphasis on density, with urban geographer Colin McFarlane (Citation2016, 637) even suggesting that ‘new urbanism articulated a new logic of density’ as ‘an ideological topology based on public transport, higher density, and social mixture’. In the last decades or so these notions of high-density residential space have emerged as the dominant features in ongoing debates about ‘sustainable’ urbanism, in particular in relation to how urban form might support mass transit infrastructure (Bibri, Krogstie, and Kärrholm Citation2020).

However, despite the intense work positioning the compact city as a sustainable vision for urban planning, visions do not make cities on their own. The actual reconfiguring of urban space along the lines of compact city visions is contingent on either steering market forces towards denser forms of urban development or, as in the Rosegård case, enrol and remake existing planning bureaucracies to reprogramme space along compact city lines. By describing actual spaces as a set of problems in contrast to dominant visions, planning motivates interventions to remake space in line with these visions. The ‘construction of problems’ are, as Foucaultian geographer Mustafa Dikeç (Citation2007) has argued in regard to renewals in French urban peripheries, ‘part of the policy-making problem’, rather than policies being ‘responses to self-evident problems’. Governmental ‘problems’ and ‘solutions’ thus tend to ‘co-emerge’ and shape each other, according to anthropologist of development bureaucracy Tania Li (Citation2007, 7), ‘within a governmental assemblage’. In spatial planning, this discursive ‘construction of problems’ can be seen as produced by the kind of technocratic expertise which urban theorist Ananya Roy has described as the ‘epistemologies’ of planning. Thus, Roy (Citation2005, 156) suggests that planning scholarship should study ‘not only techniques of implementation but also ways of knowing.’

Density measurements is an established ‘way of knowing’ urban space which in the Scandinavian context has been an epistemology of planning since the early post-war period (Mack Citation2019; Pries and Qviström Citation2021). Yet, the politics of density as planning epistemology are not given. As Colin McFarlane (Citation2016, 638) has noted, ‘density topographies [… are] always already interpreted as particular kinds of problems requiring particular kinds of solutions’. With the increasing dominance of the compact city as the leading vision of sustainable urbanism, we suggest that density as a planning epistemology is being drastically reworked to construct problems that more easily fit the compact city as a solution, along the lines theoretically suggested by Dikeç and Li. These new ways to produce knowledge about urban space are what we propose to call the compact city epistemologies of urban planning in the Global North.

This mode of expert knowledge highlights practical ‘problems’ of urban space, such as walkability or social mixing, which might be ‘solved’ by increased residential density. In terms of green space, it seems to be of particular concern to conserve areas at or beyond the urban-rural interface, but the compact city itself is seldom ‘as green as promised’ (Bibri, Krogstie, and Kärrholm Citation2020, 15). Unlike the evocative representation of rural landscapes presumed to be conserved by urban densification, we will argue that this mode of planning is set up to carelessly produce superficial assessments of the use and usefulness of the urban green spaces it targets for redevelopment. This lack of detailed attention in densification plans of areas like Rosengård is at least partly related, we suggest, to the ‘methodological cityism’ associated with the new urbanist programme, which has few tools to seriously assess modernist urban typologies of green space which neither correspond to ‘traditional’ urban forms nor preservation of rural landscapes (Pojani and Stead Citation2014; see also Qviström, Luka, and de Block Citation2019). There are few obstacles for particularly intense forms of densification in spacious modernist residential areas, because planners lack tools to map existing qualities and uses of their green spaces (see Mack Citation2021).

Rather than theorizing the superficial spatial knowledge about urban green spaces we associate with the compact city as a given effect of planning bureaucracies in general, we argue that these blind spots are contingent effects of a particular mode of planning that has emerged in recent years. The active disinterest in carefully charting certain spaces is related to a newfound focus on a narrow range of legitimate kinds of planning problems. Making use of Roy’s notion of planning epistemologies emerging from research on urban informality in India, we argue that recent theoretical work about the development bureaucracy of Southern cities is helpful to make some theoretical sense of planners’ strategically uneven attention to the spaces of development in Northern cities like Malmö.

Our argument about the selective carelessness of compact city epistemologies is in particular drawing on Claire Bénit-Gbaffou’s (Citation2018, 2156) work, suggesting that ‘deliberate opacification of information in certain sectors or areas of interventions in the city’ plays an important role in South African urban development bureaucracies. In effect, the bureaucratic amassing of detailed knowledge is according to Bénit-Gbaffou (Citation2018) paired with a strategic ‘will not to know’ about certain aspects of urban space. These sites are allowed to remain bureaucratically obscure, with interventions unrestrained by troublesome facts about these places’ actual and potential uses. Or to return to Roy’s (Citation2009) work on India, the lack of bureaucratic knowledge about particular sites, such as the edge of cities, is the result of an active process of geographic knowledge-making she suggests we think about as ‘unmapping’. Desired modes of informality can thus be allowed to play out, even as undesirable forms of informality can be purged from the urban landscape without ever being fully registered or chartered according to rigorous bureaucratic standards (see also Ghertner Citation2015). The closest European analogy to the ‘deliberate opacification’ we identify in the compact city epistemology at work in Malmö is perhaps Mara Ferreri’s (Citation2020) suggestion that the demolition of the South London Heygate Estate was made possible by a ‘willful production of ignorance’ about facts on the ground as understood by residents.

Drawing on these accounts, pointing to the selective and active production of shallow planning knowledge, we return to Malmö and Rosengård. We will show how, with the rise of the compact city as a guiding vision of Malmö’s attempt to become a pioneer of sustainable urbanism, planners have deserted established ambitions to carefully produce knowledge about the city’s modernist residential areas. Crucial to planning knowledge of the compact city epistemology is both the constructing of entirely new kinds of problems for plans to solve, but also the active unmapping of public green space. This renders unintelligible the actual uses and potential usefulness of these spaces to the planning process, and thus hides how the residents of the most racially stigmatized and economically destitute parts of Malmö are being deprived of existing rights to a green, diverse and accessible urban landscape. The actual dispossession by densification is in this way foreshadowed and made possible by an epistemological, discursive dispossession.

Methodological considerations

This article studies recent redevelopment plans of the Rosengård residential area in the Swedish city Malmö. For several decades Malmö was completely dominated by social democracy and an important laboratory of a welfarist spatial planning, but its planning bureaucracy has since the 1990s dramatically shifted to neoliberal priorities (Baeten Citation2012; Pries Citation2020). Malmö’s neoliberal urban renewal strategy was initially focused on exclusive waterfront renewal projects but has recently embraced inward expansion seeking to remake the very structure of the urban landscape left by decades of welfarist planning. This strategy has generated a wave of grassroot protests, as the large residential areas built by the city’s post-war social democratic planners one by one has been singled out for ‘densification.’ Critical geographers and urban scholars have in the last few years in detail studied the effects and responses of rent hikes in Sweden’s post-war residential areas, leading to overcrowding and displacement as well as new forms of tenant organization (Baeten et al. Citation2017; Polanska Citation2020; Pull and Richard Citation2021). The way that densification at the same time reduces access to green spaces and public amenities for the residents of these areas who manage to stay put has so far remained a largely unstudied question (see Kärrholm and Wirdelöv Citation2019).

If Malmö might be said to be among the forerunners of a densification strategy rapidly taken up by many other Swedish and Scandinavian municipalities, Rosengård was one of the cases where this strategy first began to be tested on a larger scale, with the ambition to physically remake a sizeable part of Malmö. Rosengård is the largest of Malmö’s post-war residential areas, and also one of the most clearly racialized as an ethnically othered place in Scandinavia. It is worth noting that this context is conspicuously absent in much of the material we analyze, save for discussion around safety and crime. This issue requires serious engagement with the way that planning itself is being racialized, although this line of inquiry would take us beyond what is the focus of this paper. While planning’s cavalier attitude to the residents of Rosengård’s right to urban green space is related to racism and territorial stigma, it is also the case that a cursory look at densification plans from other Swedish cities indicate the same compact city epistemology unconcerned with green space is at work also in areas clearly much less racially stigmatized.

To map the discursive dispossession created with this compact city epistemology we scrutinize the formal planning documents which the densification redevelopment of Rosengård so far has operated through. We read these plans, in particular their representations of problems and silences related to green space, as artefacts of this emerging mode of expert knowledge. The primary sources of our analysis are related to two so called ‘mobility pathways’ (stråk) projects running through Rosengård: Amiralsgatan and Rosengårdsstråket. Both projects propose new corridors of high density, medium rise housing along streets lined with pedestrian and bike paths. These two major interventions were introduced in the area strategy (planprogram) Planning program for Törnrosen and part of ÖrtagårdenFootnote1 (Malmö stad Citation2015). The Amiralsstaden project spans several strategic documents, not the least through a formally not yet approved area strategy called Planning program for Amiralsgatan and Persborg station (Malmö stad Citation2020) which at the time of writing this text is going through public consultation (samråd).

To make our analysis of these two cases more robust, we have also studied a wide range of related planning documents which we cite more sparingly in the text. These include the current Malmö Comprehensive plan (Malmö stad Citation2018a), a visionary document setting out Goals and Values for the Amiralsstaden project (Malmö stad Citation2018b), a study of Rosengård commissioned to Gehl Architects (Citation2009) by Malmö’s municipal housing company and the area plan for the Landssekreteraren block in Rosengård (Malmö stad Citation2007a). The Comprehensive Plan was written over several years and overlapped the early and formative strategic planning of the Amiralsstaden vision, but the reader should note that the final Comprehensive Plan is published in 2018, after the vision for Rosengård from 2015 which is the focus of our analysis. To chart what kinds of expert knowledge has been jettisoned with Malmö’s planning turn to a compact city planning epistemology, recent planning documents are compared with older plans such as a local housing plan (Malmö stadsbyggnadskontor Citation1974) and a historic preservation mapping of the city (Malmö Kulturmiljö & Länsstyrelsen Skåne Citation2002).

The reason for choosing to approach this issue by a close reading of planning documents is that they are a type of primary source which contain artefacts left by the very act of producing planning knowledge about space. These documents do not tell us the entire story about densification redevelopment, but they provide important insights to the formal production of planning knowledge of these redevelopment projects. We have chosen not to rely on interviews with planners because they mainly are a source of information about individual planner’s intentions and ambitions. To identify the particular epistemological techniques which produce planning knowledge we have instead studied how actual plans represent the urban landscape. This permits us to analyze which kinds of issues are skirted or avoided and which kinds of issues are constructed as problems for planning to solve, in short which kind of expert knowledge about space is tied to this particular kind of densification redevelopment. While we focus on formal plans, we make no claim of analyzing every single document produced in conjunction with these urban renewal projects but have strategically selected what we consider to be the most pivotal plans for the densification of Rosengård. Alongside close readings of the primary sources, several site visits were conducted and documented with notes, photographs and drawn maps.

Compact Malmö, spacious Rosengård

Malmö, with a population approaching 350,000 residents, is known for its compact typology. There are some stretches of single-family homes on the city edge, mostly built since the late 1970s, but to a large extent Malmö’s housing stock is made up of modernist apartment blocks built in inter-war and post-war years as well as more recent waterfront renewals. Despite being a compact and highly bikeable city for decades, increasing density has in the last decade become a key planning priority. A compact city planning vision is a defining feature of the most recent Comprehensive Plan, approved in 2018. This long term, city-wide vision focused on making Malmö a ‘socially, environmentally and economically sustainable city’ with the ‘near, dense, green and mixed city’ as ideal (Malmö stad Citation2018a, 4).

Several planning projects in Malmö taps into this vision, such as renewal projects in former industrial or harbour sites often highlighted as the strategy’s flagships (Malmö stad Citation2021). When it comes to densifying existing residential areas, the more recent single-family housing suburbs inside the municipal borders remain largely untouched. Instead, it is modernist housing estates of post-war areas which have become the most important locations for redevelopment. Socio-economically marginalized areas with modernist typologies are seemingly eligible for a particular type of densification where open spaces are used for new constructions. Examples of recent such densification projects in Malmö are Lorensborg and Bellevuegården, Holma and Lindängen (Malmö stad Citation2021), but the area that will be most thoroughly transformed by densification is Rosengård.

The two Amiralsstaden and Rosengårdsstråket projects suggest transforming large parts of the residential area. The Amiralsstaden area strategy is focused on the space around Amiralsgatan, a two-lane major thoroughfare, running through several Rosengård neighbourhoods and connecting the area with the town centre of Malmö. The Rosengårdsstråket strategy instead focuses on residential areas South of Amiralsgatan. These plans suggest creating traditional city streets lined with high-density, medium-rise housing units (see ). At the same time, the Rosengård neighbourhood centre and shopping mall is being redeveloped along a public-private partnership model and a new commuter railway station was recently opened where Rosengårdsstråket and Amiralsstaden connect to more central areas of Malmö (Gustafsson Citation2021).

Today Rosengård consists of a series of modernist neighbourhoods with just shy of 24,000 residents mainly living in multi-family housing units surrounded by generous and lush green spaces. The initial area plan was made by Malmö’s Planning Director Gunnar Lindman in 1956, and the plans for each neighbourhood within Rosengård were finalized by Lindman’s successor Gabriel Winge. While the Törnrosen area was finished already in 1964, most parts of the Rosengård area were built in the period 1967–1972 between the industrial estates along Malmö’s old rail lines and a then new ring road. The overarching priority of post-war planning designing places like Rosengård was how an emerging welfare society could be materialized by providing amenities fostering cohesive and democratic communities and providing more equal access to sport facilities, playgrounds and greenery as a public good (Franzén and Sandstedt Citation1993). This emphasis on providing a wide range of everyday assets through, or in, green spaces was common to post-war planning. In Sweden these ideas were firmly enshrined in national policy since the 1940s, endowing post-war urban design with distinctive ‘spacious’ and green typology (Kristensson Citation2003; Pries and Qviström Citation2021) which characterizes Rosengård and many other modernist housing areas.

Rosengård faced, however, wide-spread critique even as it was still being built and was singled out as one of the dominant examples of alienation and isolation of managed welfare capitalism by key cultural critics of the post-1968 new left (Ristilammi Citation1994, 28–33; Malmö Kulturmiljö & Länsstyrelsen Skåne Citation2002). The scale of certain parts of Rosengård, dominated by tower blocks, was by municipal planners early acknowledged as a mistake (Malmö stadsbyggnadskontor Citation1974). Also, the scale and, initially, meagre greenery of open spaces was criticized by the city’s Department of Social Services (Juhlin, Ronnby, and Urwitz Citation1974) for lacking amenities that could support the everyday interactions between neighbours. Even the National Council for Outdoor Play early on suggested that Rosengård was lacking a diverse outdoor environment suitable for children (Ristilammi Citation1994, 31). Not all parts of Rosengård faced the same critical response. The Örtagården area was, for instance, considered in need of substantial improvement as early as in the 1970s, whereas Törnrosen’s outdoor environment was simultaneously described as a varied, intricate and intense landscape (Malmö Kulturmiljö & Länsstyrelsen Skåne Citation2002, 132, 134).

Cultural critics’ fascination with Rosengård augmented the fact that the area was finished just as the housing shortage of Malmö developed to a housing surplus in the mid-1970s, and the new built area with its many empty flats increasingly being became regarded as lacking a community culture expressed through the use of public space as well as becoming one of the most deprived parts of the region. While poverty remains a serious, and racialized, issue in Rosengård and many other parts of Malmö, the outdoor landscape bears little resemblance to the desolate, muddy fields framed by tower blocks that once were the critics key points of contention. A pioneering community work programme for Rosengård’s residents transformed into a radical-democratic influence over local resources and the built environment, leading to early and high-profile resident-driven renewal of these green spaces (Ristilammi Citation1994, 96–98). A second wave of upgrades followed in the 1990s, including new paved surfaces, benches and seating, lighting as well as planting yet more trees and other greenery (Malmö stad Citation2007a). According to a formal 2002 report co-authored by municipal and regional cultural heritage experts, Rosengård had by then become an urban landscape characterized by mature and varied green spaces (Malmö Kulturmiljö & Länsstyrelsen Skåne Citation2002).

The community renewal in Rosengård of the 1970s echoes a broader story about how planning responded to the critique of modernist residential areas. Rather than the late 1970s and early 1980s leading to an abandonment of the new housing areas, these spaces became sites for new forms of planning. As architectural historian Jennifer Mack has argued, many new housing areas were rapidly transformed by the redesign of public spaces which often became participatory design experiments deeply involving residents (Mack Citation2019). The openness and unfinished character of these landscapes which at first had been seen as signs of alienation soon became an important spatial resource allowing residents to shape their local environment in this deep and profound way, as Wikström (Citation2017) argues. These local projects were partly funded and supported by a more general pivot in national policy from housing to recreation as the key concern of spatial planning in the late 1970s (Pries and Qviström Citation2021).

Whether Rosengård was an abject design failure, or a fairly successful planning project simply completed at the wrong time and place remains an unsettled issue. What is undeniable, though, is that both the planning of Rosengård and its initial community-driven renewals were deeply concerned with how design might speak to the rights of residents to generous, spacious and welcomingly lush everyday urban environments. It is then not surprising that formal documents assessing the area in the early ‘00s noted that the stigma and social problems of Rosengård was not the only thing that defined the area. Many of Rosengårds residents enjoyed living in the area, and the outdoor environment was in ‘many parts lush and mature’ according to a formal report (Malmö Kulturmiljö & Länsstyrelsen Skåne Citation2002, 130). Similar notions were voiced in the citizen participation processes of the 2015 area strategy, where residents made clear they found Rosengård to have a strong sense of identity and not deserving of a bad reputation (Malmö stad Citation2015, 45).

Thus, for several decades the ‘problem’ planners identified in Rosengård were primarily related to urban design as an everyday issue for, and partly defined with, local residents. Solutions to these kind of problems in turn tended to be public funds for redesign projects often based on participatory methods, from the foundational community work programme of the 1970s (Ristilammi Citation1994) to open meetings during the 1980s (MKB Citation1985, Citation1986) and 2000s (Malmö stad Citation2007b). More recently, this framing of what constitutes problems in Rosengård and how they might be solved have rapidly shifted, as a new compact city epistemology has displaced the welfarist planning focused on providing for a wide range of standardized needs dominant in the post-war era.

A compact city planning epistemology in a modernist landscape

With the 2015 Planning program of Törnrosen and part of Örtagården, planners decisively moved away from seeking to improve Rosengård's public green spaces as a way to address everyday problems experienced by, and partly defined in dialogue with, the area’s residents. Instead, the vision suggests an entirely new kind of problem for planning to solve based on other types of expert knowledge about urban space. In one of few detailed descriptions of public space in this strategic document, the area designated for a new commuter rail station is described as having ‘lawns and greenery with few qualities’, ‘no spaces or places for lingering’ and broadly ‘live up to the expectations of a non-cared for environment with lacking connections to the surrounding city’ (Malmö stad Citation2015, 47). The planning vision concedes that Rosengård’s existing ‘courtyards’ have ‘good play opportunities and rich vegetation’ but goes on to more generally describe public spaces in the area as ‘uncared for’, with a lot of hardened surfaces and limited green qualities (Malmö stad Citation2015, 68, 70). But, unlike previous renewal projects in Rosengård which would have seen this as easily addressed problems of landscape design and allocating resources for green space management, these issues had by 2015 become planning problems demanding much more dramatic interventions.

This shift is related to how planning by the late ‘00s began to disconnect the meaning of these modest public spaces in Rosengård to the experiences of the area’s residents, and instead saw them as part of a city-wide, or even regional, planning problem. Rosengård is quite favourably located close to the city centre and well-connected by transport infrastructure, as a pivotal study of the area conducted by Gehl Architects on behalf of the municipal housing company MKB conceded. Still, the area was considered ‘an island in the city’ (Gehl Architects Citation2009, 16) and thus the priority was to ‘create more connections’ to other areas and remake the urban fabric of Rosengård by a range of new forms of planning interventions like ‘densification’, ‘legible spaces’, and ‘distinct borders between public and private zones’ (Gehl Architects Citation2009, 20–21).

The influence of such mode of framing the problems with Rosengård’s urban landscape can be seen in the local planning vision presented six years later, with its three main ambitions being to ‘link’ the area to its surroundings, make the ‘urban structure legible and accessible’ and craft a ‘mixed-used Rosengård with lively street spaces’ (Malmö stad Citation2015, 6). No longer were planners describing the problem as figuring out which concerns with public space and amenities might make the area better for residents. The problem was instead countering segregation by increasing the area’s connectedness to other parts of the urban region. Rosengård was to become a ‘pilot project for creating social integration through spatial changes’ (Malmö stad Citation2015, 16).

While the bike and foot paths that the planning strategies focused on in fact already existed and were widely used by residents of the area, the vision sought to amend the problem of connectedness by building things other people in Malmö would be ‘attracted by’, like the new housing, public places and facilities in Rosengård (Malmö stad Citation2015, 3). By ‘assigning new functions to unused places and surfaces’, the vision imagined urban design qualities that would make Rosengård ‘attract’ outside visitors (Malmö stad Citation2015, 18). The two most dramatic interventions the vision proposed was a ‘landmark building’ financed by public-private partnership (Malmö stad Citation2015, 25; see also Gustafsson Citation2021) and new ‘narrow and attractive streets’ lined by traditional street-facing housing which would cut through the area’s open typology to create new urbanist corridors.

Framing the problem of planning in terms of using urban renewal to make the neighbourhood more ‘connected’ and ‘attractive’ on the urban and regional scale echoed the strategic priorities of Malmö’s planners. Since the late 1990s, Malmö’s overarching planning strategy had increasingly become using high-end urban design to attract human capital from the urban region’s affluent suburban peripheries (Pries Citation2020). The 2015 strategy, and before it the Gehl mapping, however, did more than simply bring this abstract strategy to a new part of town. This shift in who planning saw as the end end-user of space also meant a different way of formulating the very problems planning was to solve. Unkempt green spaces were no longer interpreted as mundane sites which easily could be improved by modest design interventions, but as ‘unused places and surfaces’ which demanded to be radically transformed in order to reshape the entire area’s typology. This construction of planning problems not only rhymed with overarching planning priorities of ‘attractiveness’ but also allowed densification to be posed as the given solution to neglected green space, proposing radical planning interventions in order to transform them into attractive and better-connected new urbanist mobility pathways.

Figure 1: Map of Rosengård. Ortofoto RGB 0.5m © CitationLantmäteriet, collage by authors. Amiralsgatan marked with dotted line, and Rosengårdsstråket with an arrow. The planning area of Planning program for Törnrosen and part of Örtagården is marked in yellow, while the planning area of Planning program for Amiralsgatan and Persborg station is marked in pink. The grey circle represents Rosengård’s new railway station.

Mapping and unmapping urban green space

Several studies suggest a conflict between densification and everyday green spaces (see Littke Citation2015; Treija, Bratuškins, and Bondars Citation2012; Bibri, Krogstie, and Kärrholm Citation2020). The 2015 strategy for Rosengård managed to completely side-step this potential tension between a more compact city on one hand and access to green space on the other, by a planning epistemology which produced new knowledge about urban space while at the same time unmapping it as public and green. It was thus not only which problems plans identified that shifted with the Rosengård densification, but the turn to a compact city epistemology also represented urban space in new ways. This shift is best exemplified by the 2015 Planning program for Törnrosen and part of Örtagården. To identify which public places could be targeted for densification, planners had to map the terrain and find the kinds of sites that credibly could be understood as of such poor design qualities that building on them would in fact improve them.

The ‘structure plan’ (see ) showcases the main interventions proposed in the strategic planning document: the new Rosengård commuter rail station, the mobility pathway from Rosengård neighbourhood centre towards central Malmö, existing and proposed buildings as well as public spaces and green space. The structure plan represents green spaces in three ways: 12 distinct areas between building are marked as ‘green courtyards’, one park-like ‘larger, collective, green courtyard space’ close the centre of the neighbourhood (Gröningen) and a ‘green connection between existing parks’ located outside of Rosengård. A belt of green spaces to be ‘developed’ are marked around the larger neighbourhood park.

Figure 2: The ‘structure plan’ (Malmö stad Citation2015, 7).

The most interesting part of the map is what it does not show. The key spaces it identifies are charted as well-defined ‘green courtyards’ between residential buildings. Rather than marking the entire area between residential buildings, the ‘courtyards’ are represented as a set of rounded rectangles with a band of grey between the ‘courtyard’ area and the buildings. There is, however, no definitive relation between what is marked as a ‘green courtyard’ and what spaces today actually consist of green space or public space. Nor is there any tangible relation between what is mapped as grey and what actual spaces now have hardened surfaces like paving, concrete or asphalt.

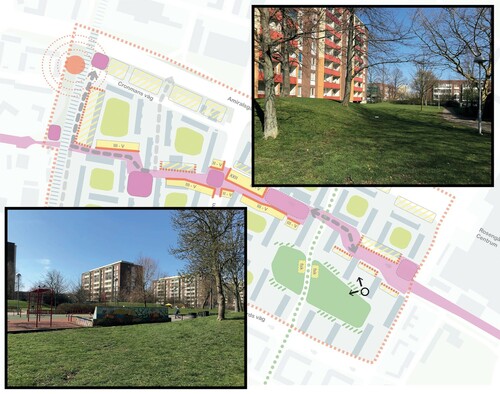

This disconnection between Rosengård’s landscape and the formal planning knowledge codified in this map can also be illustrated by comparing photographs of two views from the same point (see ). The first view turning to the left captures what in the structure map is defined as a park-like space named Gröningen and coloured in a darker shade of green. The second view turning to the right shows a similarly green park-like space, yet this site is neither park nor ‘courtyard’ and is coloured grey on the structure plan thus not indicating that it as a green space. These two views illustrate how spaces which cannot be sorted into three distinct forms of green space, and thus are represented as grey space in-between demarcated green places, might be part of a system of green public spaces. These sites have a wide range of spatial characteristics, some contain car parks while other are green spaces with mature vegetation, obscured by the structure map’s narrow focus on three kinds of public greenery.

Figure 3: Turning left, photographing a space conceptualized as green in the structure plan, and turning right, photographing a space represented as grey ‘background’. Photos and collage by author.

The use of green and grey as a way to present knowledge about Rosengård’s open spaces visually relies on an epistemological distinction between valuable, and clearly demarcated, green spaces and other kinds of open spaces. This kind of knowledge, however, completely unmaps the actual geography of Rosengård. Not only are the ‘green courtyards’ surrounded by bands of grey, but also the spaces around buildings which consist of smaller open green spaces linking the ‘courtyards’, are represented as grey and thus actively unmapped. Apart from one ‘green pathway’, the public green space which neither are neighbourhood parks nor are distinct ‘courtyards’, are in the structure plan shaded out as grey and their green qualities are thus also unmapped. The area’s broad range of differently programmed open spaces are in this rendering simply divided into green and grey areas. Thus, the manner in which modernist planning in post-war Sweden used public green space not only to create landscapes of recreation, sport and play, but also of everyday pedestrian mobility, is actively made obscure by the cartographic approach used in the structure plan (cf. Mack Citation2021).

In , we have marked densification redevelopments proposed by the 2015 strategy, color-coded yellow, on a satellite map of the area. Furthermore, to indicate the scale of combined densification renewals presently proposed we have also added the new buildings, and a ‘new’ park, of a much more recent consultation draft of a plan focused on Amiralsgatan (Malmö stad Citation2020), color-coded in pink and green. Comparing this map (see ) with the 2015 structure plan’s mapping of open spaces divided into grey and green areas () reveal how the compact city epistemology unmaps the green spaces that the very same plans propose to redevelop. All of the 2015 plans new (yellow, filled) and refitted or demolished (yellow, outlined) buildings that line the compact city style mobility pathway are in the structure plans indicated to be on grey open spaces, sometimes also assisting the emergence of green courtyard spaces between buildings. As the satellite image reveals, they are however predominantly placed on land which today is public or semi-public green space.

Figure 4: Orthophoto of the site (Ortofoto RGB 0.5m © CitationLantmäteriet) combined with the proposed built additions of the 2015 structure plan in yellow and the proposed built additions and park of the 2020 structure plan in pink and green. Collage by authors.

The compact city vision of adding a substantial amount of housing units in Rosengård not only meant jettisoning an established body of planning knowledge which had put the landscape’s lushness and its relationship to residents in focus. New modes of expert knowledge also co-emerged with this vision of a compact city. In terms of the ‘problems’ this compact city epistemology proposed planning solutions for, they were about increasing connectivity and attractiveness of these urban spaces through spectacular redevelopment. As we have argued above, the emerging epistemology of compact urban planning maps public spaces as an imagined geography of clearly defined borders between parks, ‘courtyards’, roads and buildings. This mode of knowledge only identified public green space as distinctly demarcated areas, even as these were part of multi-scalar urban landscapes. In effect, the emerging compact city epistemology at work actively unmapped the greenness of all other kinds of space by presenting them as something other than green space worth preserving. This discursive production of non-green open space then allowed parts of the actual green geographies of Rosengård to be designated for renewal, without ever having to account for the destruction of everyday green space implied by the proposed renewal.

The geographic vagueness of the expert knowledge produced by this planning epistemology thus left substantial parts of the charted area in something much like what Bénit-Gbaffou (Citation2018) describes as a fog of ‘deliberate opacification’ or Ferreri (Citation2020) discusses as ‘wilful production of ignorance’. This makes the blind spots of the compact city epistemology, as we have underlined, productive in designating developable sites for densification renewals without identifying negative consequences for the people living in the area. The potential conflict between densification and the local residents’ uses and their relation to their area’s everyday landscapes was effectively displaced by this unmapping, which refused to even chart the extent and structure of green space and its relation to planned renewal projects. Thus, the seemingly impossible equation of the city remaining green while becoming more compact could temporarily be considered solved.

Determining the quality of urban green space

The unmapping of green space in the 2015 structure plan concealed both the typology and scope of public greenery in Rosengård. It presented a picture where it was impossible to understand that green spaces were designated for densification. The strategic plan also engaged in a more detailed mapping of the design qualities of particular green spaces in Rosengård. While the quantity of greenery was to decrease, both in absolute and relative terms as thousands of new housing units were planned, this could according to planning documents be compensated by increasing the quality of green space. Realizing the vision of a ‘green’ and ‘compact’ city required redesigning the landscape so that ‘higher intensity and better quality for remaining green spaces’ compensated for this quantitative loss (Malmö stad 2019, 40; cf. Littke Citation2015). Modelling future spaces for more intense use thus also entails a sort of densification of green space.

The plans thus had to identify which places were to hold this ‘higher intensity’ and ‘better quality’ of design, and thus be protected from redevelopment. One example of such assessment is how Gröningen, the large public green space which the 2015 plan formally categorized as a type of park. This site is described as one of ‘few qualitative green spaces’ in the area (Malmö stad Citation2015, 68), and was therefore to be protected from housing construction with even more recreational functions proposed to be added to it (Malmö stad Citation2015, 44). Similarly, the two-kilometre-long double row of trees lining one of the main roads of Rosengård, Västra Kattarpsvägen, is described as ‘an important structuring spatial element with great symbolic value’, and thus something worth preservation (Malmö stad Citation2015, 69).

One might have expected planners to identify the same potential in the green spaces around the residential housing blocks, with the courtyards of western Rosengård briefly noted as ‘the most important meeting places’ for ‘elderly and parents (mainly women)’ (Malmö stad Citation2015, 44). Nonetheless, these courtyards are also described as ‘unused spaces’ which must be programmed with more clearly defined ‘content’ (Malmö stad Citation2015, 37). This is particularly interesting considering that the vision document from 2018, Amiralsstaden—Goals and Values, highlight the need of everyday places for encounters and socialization especially for women and girls, to make these groups feel welcome and safe (Malmö stad Citation2018b, 12). Furthermore, ‘carefulness and respect’ was to guide the densification since it is people’s ‘existing living environment that will be affected’ (Malmö stad Citation2018b, 6). Rather than seeing these places uses and usefulness as a potential to protect, like the Gröningen park, the plans actual engagement with the design of these very spaces constructs them as a problem by emphasizing the courtyards as too big and thus ‘unused’ according to the expectations of what can be accounted for as an ‘intense’ use of urban green space.

Representing the courtyards as ‘unused’ was clearly a productive way of mapping the area since it precisely matched the plan’s proposal that ‘parts of the existing courtyards’ be redeveloped by new housing construction (Malmö stad Citation2015, 40). Indeed, the plan’s proposed corridor of low-rise townhouses along one of the mobility pathways were to be built with private terraced gardens on some of the taller, modernist building’s existing courtyards. This clear-cut privatization of public space might perhaps entail less access to everyday green space for those living in the existing housing stock, but also in this case did the planners’ attention to ‘qualities’ of spatial design obscure this contradiction. The residents of apartment blocks losing parts of the courtyard would be compensated by the new ‘visual qualities’ that private courtyards provide for those looking in at them (Malmö stad Citation2015, 40). This dispossession by privatization of public space was thus clearly preceded and, we argue, made possible by an epistemological dispossession in the plan’s production of knowledge. The plan reduced the courtyards actual uses as meeting places to a mere parenthesis in mapping the area’s green spaces, and instead frontloaded its findings that these sites were desolate, ‘unused’ and lacking design qualities—allowing privatization of these spaces to be presented as a solution to a planning problem. Private gardens were presented to contribute to the problem of the neighbourhood’s lack of ‘visual qualities’ and increased ‘intensity’.

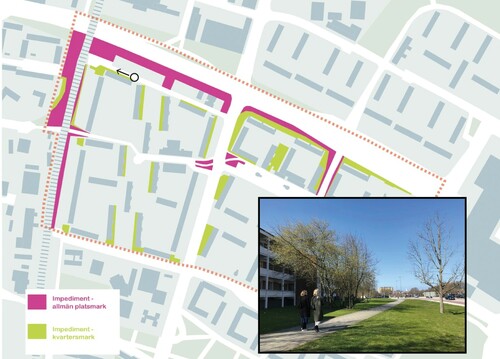

A set of green spaces constructed as having even less value in the 2015 strategic plan’s mapping, and thus requiring the least care when densifying Rosengård, were so called ‘impediment surfaces’ (impedimentsytor). This kind of common feature in the urban landscape consists of various scales of barriers, often lawns or hedges, surrounding housing, pedestrian walkways or roads. The 2015 strategic plan suggested that ‘impediment surfaces are hard to define and underused without specific functions’ (Malmö stad Citation2015, 44), thus offering an epistemological device for determining these spaces lack of usefulness without actually studying their role within a planned network of green spaces and ask potentially troubling question about their actual uses. Such reasoning brings to mind geographer Fran Tonkiss’ (Citation2013, 49) argument about the challenges of mapping certain mundane uses, like passing-by or lingering, in spaces designed for intensity and many uses.

The area’s impediment surfaces were carefully charted in a separate map (see ), but the actual features of these green spaces are in the same visual representations completely unmapped. Rather than a discussion of how to compensate for the loss of green space which building on impediment surfaces meant, the plans notes that these spaces provide ‘an opportunity for new additions’, echoing how Skärbäck et al. (Citation2014) stresses that public spaces adjacent to buildings often are characterized as ‘not yet built land’.

Figure 5: Map of impediment surfaces (Malmö stad Citation2015, 70) and a photograph exemplifying the character of these green spaces. Photo by author.

The map underscores a strange way that densification renewals are enabled by compact city epistemologies. This mode of planning knowledge dismissed quantitative mapping as unnecessary when assessing green space provision and simultaneously made use of it to identify green spaces to redevelop, just as it both highlights the need for more qualitative design features without qualitatively assessing the existing landscape’s features. The qualitative deficiencies of the modernist landscape’s in-between spaces are established by the very act of identifying a space as an impediment surface, much as urban geographer Asher Ghertner describe slum demolition in India relying on ‘aesthetic governmentality’ (Ghertner Citation2015) judging the fate of entire areas based on a few visual cues. No empirical elaboration about spaces’ actual design qualities appears to be needed, in this simultaneous mapping and unmapping of public space. The potential qualities of such spaces are thus not investigated seriously, as these sites are quantitatively mapped to mark spaces that can be offered for renewal with minimum need for compensation—because of an assumed lack of qualities. This is all the more ironic since the decreasing quantity of green space associated with densification is also assumed to not be a problem because of the plan’s claim to add design qualities, without ever mapping existing qualities.

The same tension between casual dismissal of quantitative measurements in the name of qualities which never are examined can also be seen in the most recent planning strategy Planning program for Amiralsgatan and Persborg station (Malmö stad Citation2020). This document, focusing on the densification of both sides the Amiralsgatan thoroughfare visible in , concedes that ‘the amount of green space per inhabitant decreases’ and courtyards are ‘made smaller than guidelines suggest’ (Malmö stad Citation2020, 80–81). Once again, this quantitative loss of green spaces is compensated in the plan by proposing to add more ‘qualities’ without any mapping of which qualities the existing green spaces might have. Also in this case is the planning knowledge produced with a compact city epistemology assuming a lack of design qualities, even as it unmaps and obscures the qualities of the places suggested as sites for densification renewal. For instance, it is almost impossible to make out that the plans only proposed new green space of significance, where these new qualities compensating for densification could be located, is a parklet on what already is a green space (see ). A large and unusually lush impediment surface, next to the busy two lane Amiralsgatan street, is simply reclassified as park without noting which qualities this site already has and what qualities one could expect to add to this kind of site lining a busy street.

The mapping of impediment surfaces and residential yards are similar in the ways that they defined such green spaces as distinct objects cut off from their location in multi-scalar urban landscapes and how they were positioned as spaces without qualities. Both the quantitative loss of open space, demanded by densification, and the potential qualitative loss of the appropriated green space was actively unmapped in the making of planning knowledge in a compact city epistemology. The densification of Rosengård thus speaks to how new problems solved by redevelopment have been produced, and how unmapping green spaces in a range of complex ways is a knowledge-making technique used in this context. This discursive dispossession of resident’s everyday landscape makes it possible to drastically renegotiate what until recently were indisputable rights to urban nature guaranteed by the social-democratic planners of post-war projects, seized and expanded from below in places like Rosengård.

Conclusion: discursive dispossession by a compact city epistemology

Malmö’s municipal planning’s turn to a compact city epistemology, exemplified by the renewal of Rosengård, has led to dramatic urban densification plans based on new modes of expert knowledge about green space which both suggest urgent problems solved by redevelopment and obscure the stakes of these interventions for residents’ access to green space. The dispossession of residents’ right to green space which this kind of expert knowledge makes possible is shaped by a range of factors, including new urbanist architectural debates (McFarlane Citation2016), emerging ideas of the compact city as sustainability fix (Bibri, Krogstie, and Kärrholm Citation2020) and Malmö’s turn to a neoliberal planning model where space is designed to attract demographic with human capital (Pries Citation2020). That the target of these most dramatic densification renewals are the modernist green spaces of residential areas built in the post-war period means that this process intersects with, and is augmented by, recent changes in these particular areas. The increasing financialization of public housing and land pushing people out of their homes (Baeten et al. Citation2017; Polanska Citation2020; Gustafsson Citation2021; Pull and Richard Citation2021) potentially makes green space a secondary issue for many residents simply struggling to stay put. The territorial stigmatization of racialized poverty (Kärrholm and Wirdelöv Citation2019) might in part explain the planners’ carefree production of expert knowledge with glaring blind spots for the needs of local residents.

This article has shown how the actual dispossession of the right to urban green space which the densification of Rosengård entails is nested within a discursive dispossession which makes invisible, or at least obscures, the everyday uses and usefulness of green spaces for residents. The epistemological devices used to create planning knowledge about Rosengård’s modernist landscapes slated for densification are calibrated to produce knowledge about green space which identify problems that densification might solve; focusing on ‘empty’, ‘unused’, ‘uncared’ for places having few ‘design qualities’ or even failing to account for these landscapes as green space altogether. The emerging compact city planning epistemology deployed to transform places like Rosengård also appears designed to create planning knowledge actively unmapping any mundane uses of urban green space that once were put in place to provide for resident’s needs and desires.

The most glaring example of how this planning knowledge unmaps modernist green spaces is related to the assumption that the modernist landscapes, and in particular its ‘impediment surfaces’ which are firmly situated within a modernist spatial design discourse, are too generous but have no design qualities. These assumptions make it possible to neither chart the actual design qualities of places nor the quantitative loss of green space. Existing spaces are by the briefest glance marked as ‘unused’ and lacking the spectacular design ‘qualities’ that redevelopment could bring.

We hope that our argument contributes to the ongoing debates about the many facets of displacement in the neoliberal city by highlighting the role of planning knowledge in appropriating green space in modernist, marginalized residential areas for the purpose of redevelopment. The compact city epistemology not only facilitates this dispossession by densification but obscures the way that the contradiction between green and compact city in this way is settled by seizing public green spaces of marginalized communities. With the compact city being uncritically adopted as the main solution for sustainable urban development, we suggest that planning must rapidly pivot to knowledge-making practices that take the many scales of modernist public green space design much more seriously, and that together with local residents ask how these spaces might be improved. The compact city is not a sustainable mode of urbanism if it comes at the cost of an unacknowledged dispossession by densification of important green spaces in a city’s most deprived and stigmatized areas.

Acknowledgements

This article has benefitted greatly from the comments offered by the editors and anonymous peer reviewers. Suggestions and encouragement from Mattias Kärrholm and Erik Jönsson have also contributed to improving the text. Catharina Nord offered valuable guidance in the initial stages of collecting and analyzing empirics, laying ground for this publication.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alva Zalar

Alva Zalar is a PhD student in the Department of Architecture and Built environment and Agenda 2030 Graduate School at Lund University. Email: [email protected]

Johan Pries

Johan Pries is Associate senior lecturer in the Department of Human Geography at Lund University. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 All titles and quotes from the municipal planning documents are translated from Swedish to English by the authors.

References

- Baeten, G. 2012. “Normalising Neoliberal Planning: The Case of Malmö, Sweden.” In Contradictions of Neoliberal Planning: Cities, Policies, and Politics, edited by T. Taðsan-Kok and G. Baeten, 21–42. Dordrecht: Springer .

- Baeten, G., and C. Listerborn. 2015. “Renewing Urban Renewal in Landskrona, Sweden: Pursuing Displacement Through Housing Policies .” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 97 (3): 249–261.

- Baeten, G., S. Westin, E. Pull, and I. Molina. 2017. “Pressure and Violence: Housing Renovation and Displacement in Sweden .” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 49 (3): 631–651.

- Bénit-Gbaffou, C. 2018. “Beyond the Policy-Implementation Gap: How the City of Johannesburg Manufactured the Ungovernability of Street Trading .” The Journal of Development Studies 54 (12): 2149–2167.

- Bibri, S. E., J. Krogstie, and M. Kärrholm. 2020. “Compact City Planning and Development: Emerging Practices and Strategies for Achieving the Goals of Sustainability .” Developments in the Built Environment 4 (2020): 100021.

- Dikeç, M. 2007. “Space, Governmentality, and the Geographies of French Urban Policy .” European Urban and Regional Studies 14 (4): 277–289.

- Ferreri, M. 2020. “Painted Bullet Holes and Broken Promises: Understanding and Challenging Municipal Dispossession in London’s Public Housing ‘Decanting’ .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 44 (6): 1007–1022.

- Franzén, M., and E. Sandstedt. 1993. Välfärdsstat och byggande: Om efterkrigstidens nya stadsmönster i Sverige. Lund: Arkiv .

- Gehl Architects. 2009. Malmö – Strategy for Outdoor Spaces in Rosengård, Links to Malmö and Identity in the Öresund Region. Copenhagen: Gehl Architects .

- Ghertner, D. A. 2015. Rule By Aesthetics: World-Class City Making in Delhi. Oxford: Oxford University Press .

- Gustafsson, J. 2021. “Spatial, Financial and Ideological Trajectories of Public Housing in Malmö, Sweden .” Housing, Theory and Society 38 (1): 95–114.

- Juhlin, D., A. Ronnby, and V. Urwitz. 1974. Rosengård. Malmö: Socialförvaltningen .

- Kärrholm, M., and J. Wirdelöv. 2019. “The Neighbourhood in Pieces: The Fragmentation of Local Public Space in a Swedish Housing Area .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43 (5): 870–887.

- Kristensson, E. 2003. Rymlighetens betydelse: en undersökning av rymlighet i bostadsgårdens kontext. Diss. Lund: Lunds universitet .

- Lantmäteriet. Geodata Extraction Tool – GET. Accessed October 26, 2021. https://maps.slu.se.

- Li, T. M. 2007. The Will to Improve: Governmentality, Development, and the Practice of Politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press .

- Littke, H. 2015. “Planning the Green Walkable City: Conceptualizing Values and Conflicts for Urban Green Space Strategies in Stockholm .” Sustainability 7: 11306–11320.

- Mack, J. 2019. “Renovation Year Zero: Swedish Welfare Landscapes of Anxiety, 1975 to the Present .” Bebyggelsehistorisk Tidskrift 76: 63–79.

- Mack, J. 2021. “Impossible Nostalgia: Green Affect in the Landscapes of the Swedish Million Programme .” Landscape Research 46 (4): 558–573.

- MacLeod, G. 2013. “New Urbanism/Smart Growth in the Scottish Highlands: Mobile Policies and Post-Politics in Local Development Planning .” Urban Studies 50 (11): 2196–2221.

- Malmö kulturmiljö & Länsstyrelsen Skåne Län. 2002. Bostadsmiljöer i Malmö: Inventering. Del 3 1965–1975. Malmö: Malmö kulturmiljö .

- Malmö stad. 2007a. Planbeskrivning tillhörande förslag till detaljplan för kvarteret Landssekreteraren i Rosengård i Malmö. Dp 4953. Malmö: Stadsbyggnadskontoret .

- Malmö stad. 2007b. Rosengård bjuder in till medborgardialog. https://www.mynewsdesk.com/se/malmo/events/rosengaard-bjuder-in-till-medborgardialog-10699.

- Malmö stad. 2015. Planprogram för Törnrosen och del av Örtagården i Rosengård i Malmö. Malmö: Stadsbyggnadskontoret .

- Malmö stad. 2018a. Översiktsplan för Malmö: Planstrategi. Malmö: Malmö stad .

- Malmö stad. 2018b. Amiralsstaden – Mål och värden. Malmö: Malmö stad .

- Malmö stad. 2020. Planprogram Amiralsgatan och Station Persborg: Från nu till år 2040. Malmö: Malmö stad .

- Malmö stad. 2021. Stadsutvecklingsområden. Accessed October 26, 2021. https://malmo.se/Stadsutveckling/Stadsutvecklingsomraden.html.

- Malmö stadsbyggnadskontor. 1974. Boendet: krav och resurser – en sammanställning för generaplanearbetet.

- McFarlane, C. 2016. “The Geographies of Urban Density: Topology, Politics and the City .” Progress in Human Geography 40 (5): 629–648.

- McFarlane, C. 2020. “De/Re-densification .” City 24 (1–2): 314–324.

- MKB. 1985. Vårt MKB, 1985(4).

- MKB. 1986. Vårt MKB, 1986(1).

- Pérez, F. 2020. “The Miracle of Density: The Socio-Material Epistemics of Urban Densification .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 44 (4): 617–635.

- Pojani, D., and D. Stead. 2014. “Dutch Planning Policy: The Resurgence of TOD .” Land Use Policy 41 (November): 357–367.

- Polanska, D. V. 2020. “Housing as a Social Right in Times of Financialization .” Almanach 2020–2021, Concilium Civitas.

- Pries, J. 2020. “Neoliberal Urban Planning Through Social Government: Notes on the Demographic Re-engineering of Malmö .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 44 (2): 248–265.

- Pries, J., and M. Qviström. 2021. “The Patchwork Planning of a Welfare Landscape: Reappraising the Role of Leisure Planning in the Swedish Welfare State .” Planning Perspectives 36 (5): 923–948.

- Pull, E., and Å Richard. 2021. “Domicide: Displacement and Dispossessions in Uppsala, Sweden .” Social & Cultural Geography 22 (4): 545–564.

- Qviström, M., N. Luka, and G. de Block. 2019. “Beyond Circular Thinking: Geographies of Transit-Oriented Development .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 43 (4): 786–793.

- Ristilammi, P. M. 1994. Rosengård och den svarta poesin: En studie av modern annorlundahet. Stehag: Symposion .

- Roy, A. 2005. “Urban Informality: Toward an Epistemology of Planning .” Journal of the American Planning Association 71 (2): 147–158.

- Roy, A. 2009. “Why India Cannot Plan Its Cities: Informality, Insurgence and the Idiom of Urbanization .” Planning Theory 8 (1): 76–87.

- Skärbäck, E., J. Björk, J. Stoltz, K. Rydell-Andersson, and P. Grahn. 2014. “Green Perception for Wellbeing in Dense Urban Areas – a Tool for Socioeconomic Integration .” Nordisk Arkitekturforskning 2: 179–205.

- Tonkiss, F. 2013. Cities by Design: The Social Life of Urban Form. Cambridge: Polity .

- Treija, S., U. Bratuškins, and E. Bondars. 2012. “Green Open Space in Large Scale Housing Estates: A Place for Challenge .” Journal of Architecture and Urbanism 36 (4): 264–271.

- Tunström, M. 2009. På spaning efter den goda staden: om konstruktioner av ideal och problem i svensk stadsbyggnadsdiskussion. Diss. Örebro: Örebro universitet .

- Wikström, T. 2017. “Spontaneous Welfare Design.” In Forming Welfare, edited by K. Lots, J. Pagh, and E. Braae, 29–37. Copenhagen: Arkitektens förlag .

- Yiftachel, O. 2020. “From Displacement to Displaceability .” City 24 (1–2): 151–165.