Abstract

In this paper, we set a framework for the Special Feature on urban living together by highlighting the main forces which, we contend, have significantly reshaped urban citizenship in recent times. Nearly two decades after the formulation of Doreen Massey’s influential concept of ‘throwntogetherness’, we engage it in a conversation with differing, often contrasting, urban realities. Throwntogetherness highlights the making of urban space through fluidity, openness and diversity within a ‘power geometry’ of global neoliberalism. We analyse the concept’s engagement with recent countervailing forces, in particular neo-nationalism and the digitisation of the city. These forces have mobilised a range of ‘hostile environment’ policies towards migrant, indigenous and marginalized communities, propelling practices of bordering, denial of rights, housing displacement and exclusion. The new assemblage of forces, we further argue, intensify the dialectic tension between throwntogetherness and ‘thrownapartness’ and increasingly lead to ‘urban apartheid’ in cities across the globe. We draw on contributions to the Special Feature which engage with these tensions in Bologna, Rome, Singapore, Glasgow, Budapest, Jerusalem/Al-Quds and Dhaka. These case studies illustrate the re-making of urban citizens throwntogether and thrownapart in contemporary hostile environments.

When I think of the term ‘hostile environment’, it conjures up notions of a war zone, of environmental degradation or an inhospitable climatic event, perhaps an earthquake – something stark and unpleasant, like a scene from a World War I killing field. I do not think – or, should I say, I had not previously thought – of it as something to do with my own country. (Lord Bassam of Brighton, UK House of Lords, 14 June 2018)

This is how Lord Bassam of Brighton started his powerful speech at the United Kingdom’s (UK) House of Lords’ meeting on immigration and ‘hostile environment’ in June 2018. Hostile environment refers here to a range of policy and political measures aimed at hardening immigration regimes through intensifying levels of inhospitality, denial of protection and services, and exclusion. In his speech, Lord Bassam said that the UK’s hostile environment policy had profoundly impacted the lives and livelihoods of migrant, minority ethnic and marginalised communities and effectively led to the production of a displaceable ‘underclass’ of the highly vulnerable to exploitation. Given the distinctively urban nature of these communities, the emergence of hostile environments is, we believe, of great concern to the reshaping of urban societies. This is relevant far beyond the UK as urban areas continue to grow rapidly in all world regions, and with added force against the recent environmental and climate crises and the Covid-19 pandemic. So what does ‘hostile environment’ mean for contemporary cities? What does it mean for urban togetherness?

To say that urban societies are undergoing immense change borders on a truism, but as we enter the third decade of the twenty-first century, these changes are particularly profound. The rapidly growing volumes of migration, both internal and international, fundamentally reshape the demographic profiles of cities and reconfigure human relations between and within urban societies. The recent rise of populism, nativism and (neo-)nationalism, against the backdrop of deepening global capitalism and related austerity policies, mean that people are increasingly exposed to different and competing ideas. Individuals, communities and institutions are also dramatically reconfiguring the relationships with one another, and with the city as the site of extension of as well as resistance to the state (De Genova Citation2015; Porter and Yiftachel Citation2019; Roy Citation2011).

In the ever-growing scholarship on urban living, the concept of ‘throwntogetherness’ has been particularly illuminating in capturing these relationships. Proposed by Doreen Massey in her germinal work For Space (Citation2005), throwntogetherness refers to the making of urban society in spaces where people different from one another in terms of ethnicity, religion, class, sexuality, gender, age and disability are ‘thrown together’. The concept further denotes the throwntogetherness of ‘conflicting trajectories’ of forces that engage in urban formation and the constant engagement of humans with non-human elements in the making of urban society. This diverse mixing of residents, materialities, ideologies and politics makes and remakes the contemporary city.

Admittedly, throwntogetheness and how it is lived, claimed, denied, and dismissed has inspired a rich and eclectic scholarship spanning a wide range of empirical studies dealing with urban difference, collaboration, conflict and struggles (for overview see Fincher et al. Citation2019), as well as conceptual frameworks such as the ‘stranger’ (Amin Citation2012), ‘superdiversity’ (Vertovec Citation2007), ‘encounter with difference’ (Valentine Citation2008; Vieten and Valentine Citation2015), ‘conviviality’ (Gilroy Citation2004), ‘commonplace diversity’ (Wessendorf Citation2014), ‘everyday multiculturalism’ (Wise and Velayutham Citation2009), ‘urban multiculture’ (James Citation2015; Neal et al. Citation2013) as well as (diasporic) ‘right to the city’ (Harvey Citation2008; Finlay Citation2019), ‘grey spacing’ and ‘defensive citizenship’ (Yiftachel Citation2015; Yiftachel and Cohen Citation2021), and ‘urban citizenship’ (Pine Citation2010; Blokland et al. Citation2015). However, the concept of throwntogetherness as well as further elaborations have not been engaged theoretically in the context of ‘hostile environment’ in its various forms and guises, particularly in the current age of populist resistance to migration and a rise of neo-nationalism.

This Special Feature is an attempt to make this theoretical bridge and reconfigure throwntogetherness against the backdrop of unfolding urban ‘hostilities’ and a surge of what Abuzaid and Yiftachel (in this Special Feature) describe as ‘thrownapartness': a stifling of space by means of forceful segregation and stratification, leading at times to the emergence of urban apartheid (Yiftachel Citation2009, Citation2020). It comes out at a time marked by struggles over rights, identity and bordering (De Genova Citation2015; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy Citation2018), and intensifying urban inequalities following accelerating globalisation of capital, a rise of neo-nationalism, and the hardening of bordering processes. This is, indeed, a profoundly challenging time for urban societies – a time to re-consider how we ‘live together’ in the city. To better understand the nature of these unfolding processes, in this Special Feature we call for a renewed and refreshed theoretical engagement with throwntogetherness (Massey Citation2005).

To that end, throughout the Special Feature we draw attention to the simultaneous amplification of the forces of integration and separation in the city, and highlight the power structures and deliberate discriminatory policies and practices that interact in the meeting of ‘throwntogetherness’ and hostile environments. These interactions, we argue, recreate a new, deeply stratified, urban citizenry. Some of the salient forces that underlie the making of this citizenry, in particular new expressions of exclusive nationalism and digitisation of the city, have not been given sufficient attention in Massey's work. In this Special Feature, we intend to close this gap.

In what follows, we bring together an international group of emerging, predominantly early-career scholars, hailing from the ‘global’ south, east, north and west, and representing interdisciplinary perspectives on urban throwntogetherness in hostile environments. We build upon four conference sessions at the 2019 Association of American Geographers Meeting in Washington DC titled Throwntogetherness in turbulent times: Diversity, Migration and the City and organised by Carlos Eastrada-GrajalesFootnote1 and Anna Gawlewicz. Following this introduction, the Special Feature includes a series of interventions encompassing three articles, three visual essays and an epilogue by Ruth Fincher, a leading feminist and urban geographer, and a friend of Doreen Massey. In the remainder of the introduction, we propose how throwntogetherness can be reconfigured in the context of ‘hostile environment’ by firstly foregrounding urban citizenship, and then focusing on processes of (neo-)nationalising and digitising the city.

Urban Citizenship and ‘Throwntogetherness’

‘Urban citizenship’ is pivotal for this Special Feature given its connectedness to both throwntogetherness and ‘hostile environment’. Urban citizenship denotes the package of rights, capabilities, statuses and power attained by residents as they pursue their lives in the city (Zhang Citation2002). In this context, Massey's work (Citation2005) illuminates the spatial making of urban social relations and how societies are shaped and reshaped in place. Institutions, communities, and individuals are always negotiating social, gender and political relations in urban places. These relations are forever malleable, chaotic, and contested.

Urban places, Massey (Citation2005) reminds us, are assemblages of multiple and simultaneous materialities, times, powers and identities, which are always ‘becoming’ as:

“ … ever-shifting constellations of trajectories [which] pose the question of our throwntogetherness. (…) Places in particular form the question of our living together. And this question (…) is the central question of the political. The combination of order and chance, intrinsic to space and here encapsulated in material place, is crucial.” (Massey Citation2005, 151)

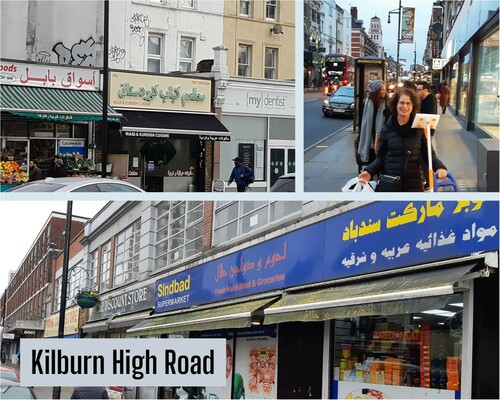

While Massey's theorisation of place is informed by Marxian and Feminist framing, her approach leaves room for people to create their own places and identities. She famously captured that by reflecting on the ‘global sense of place’ in her beloved neighbourhood of Kilburn in North-West London (Massey Citation1991; see ), crystallized within the circumstances of immigrants and veterans, young and old, rich and poor of diverse cultural backgrounds being ‘thrown together’. While she did not use the term urban citizenship explicitly, her account engages with its main components – participation, representation, distribution, housing, mobility and identity, shaped within the urban ‘geometry of power’ and through constant asymmetric struggles typifying contemporary neoliberal capitalism.

Figure 1: Commercial ‘throwntogetherness’ in Kilburn High Road, London, 2019 (photos by Oren Yiftachel).

Given this diverse urbanising context, recent research has made important strides towards understanding the links between cities and citizenship. As Varsanyi (Citation2006) outlines, three major approaches have emerged in theorising urban citizenship: transnational, re-scaling, and agency-centred. First, transnational theorists, whose work influenced Massey's account, articulate urban citizenship as a socio-political identity embedded within these enabling and interrelated cosmopolitan spaces (Harvey Citation2012; Sassen Citation2000, Citation2016). Often critiqued for its fluid understanding of the limits of citizenship and bordering (Beck Citation2004), transnational scholarship has nonetheless opened up possibilities for open-ended urban politics.

Second, re-scaling theorists have attempted to rescue the urban from its traditional structures of power, re-embedding it within multi-scalar systems of capabilities and within a set of supporting transnational institutions, and infrastructures, notably relating to class, mobility, and communication (Bauböck Citation2003; Brenner Citation2019; Datta Citation2018). The cosmopolitan and re-scaling approaches offer analytical lenses through which to entertain the possibilities of a non-statist citizenship-regulating mechanism, although the recent wave of neo-nationalism threatens some of their assumptions.

Third, the agency-centered approach, which also inspired Massey, offers a process-driven alternative to formal citizenship, based on urban residents’ constant negotiation of their throwntogetherness. It lays out a dynamic constellation of constantly changing relationships between residents’ agency, structural forces and urban space, expressed by ongoing ‘performance’ of identity and local embeddedness. Urban citizenship is a contested process of negotiation through which various agents can make claims on, for and through urban space (Amin Citation2012; Blokland et al. Citation2015). People's right to use city space is not merely a means for economic motives, but a fundamental right and a valid end in and of itself (Mitchell Citation2003; Desai and Sanyal Citation2013).

Conceptually, throwntogetherness attaches great importance to the role of public space in its material, political and conceptual capacity. It is the ‘public’ that creates the arenas for negotiating social and political meaning. Massey (Citation2005) reiterates the importance of preserving and expanding public space in the face of increasing privatisation, closure and exclusion. But she also stresses that public spaces should not hide the throwntogetherness and its associated conflicts over shared and contested space to successfully manage diverse and complex urban societies. Instead, the making of all things public must face the inevitable antagonism and struggle as part of contemporary urban life:

“The very fact that they are necessarily negotiated, sometimes riven with antagonism, always contoured through the playing out of unequal social relations, is what renders them genuinely public. Moreover, places vary, and so does the nature of the internal negotiation that they call forth. ‘Negotiation’ here stands for the range of means through which accommodation, anyway always provisional, may be reached or not.” (Massey Citation2005, 153).

(Neo-)nationalism and ‘Thrownapartness’

Recent waves of anti-immigration sentiments and majority-centric policies have had an immense impact on urban societies by complicating the already precarious position of minorities and marginalised communities, often causing frictions between communities, normalising racism and discrimination (de Mars et al. Citation2018; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy Citation2018) and increasing levels of urban displaceability (Yiftachel Citation2020). In this Special Feature, we call for recognising neo-nationalism as a key driving force in the emergence of urban hostile environments. This factor has been largely ignored in urban studies literatures.

Scholars have attributed the rise in nationalism to a number of prevailing global circumstances such as increasing migration, austerity and the deepening stratification of contemporary capitalism, as well as the perceived (yet not always actual) loss of privilege among dominant groups (e.g. Antonsich Citation2018; Bollens Citation2007). Valluvan and Kalra (Citation2019, 2393) have described this contemporary type of populist nationalism as ‘inward’: ‘anxious, resentful and defensive’. They have argued that it is distinctive in that ‘it marks a process through which a self-appointed normative majority attributes its socioeconomic, cultural, security concerns to the putatively excessive presence and allowance made to those understood as outsiders’ (Valluvan and Kalra Citation2019, 2395; see also Clements Citation2018). This type of nationalism has surfaced in most global regions. It presents several new attributes, including new ethnic and racial formations, a tendency to adopt religious narratives, the erosion of liberal and social democracy, the adoption of authoritarian practices, and the cultivation of direct communication channels mainly through social media. Hence, we speak of neo-nationalism.

Because of this connection to ‘outsiders’ and otherness more broadly, the global rise of neo-nationalism has been – and will continue to be - particularly consequential for urban societies. Surprisingly enough, against this backdrop, the nexus of nationalism and the city remains largely underexplored (with a few exceptions, e.g. Bollens Citation2007; Wilson Citation2015; Yiftachel and Yacobi Citation2003). Antonsich (Citation2018, 1) has recently argued that scholars working on urban diversity have traditionally moved away from the nation and prioritised ‘alternative socio-spatial registers where diversity might be more fully embraced and lived’. This has created a deepening gap in our understanding of relationships between the city and state power.

Related to the above is a reappearance of colonial-like relations in urban areas. This is the result of the large-scale international and internal migrations to urban regions, creating what Yiftachel (Citation2009) has termed ‘grey space’, in which marginalised pockets of the urban population are governed by the principles of ‘separate and unequal’. The new ‘coloniality of cities’ (Porter and Yiftachel Citation2019) is premised on a legal geography of stratified state-urban citizenship, whereby privileged groups are protected by legal and planning tools which produce further segregation and ghettoisation.

Hence, in vast parts of the urban world, the newcomers as well as local indigenous and marginalised communities are ‘thrownapart’ by the assemblage of domination structures and hostile politics, and are often repressed by impregnable boundaries and accelerating land values. This leads to their impoverishment, racialisation, segregation, displacement, and ‘disposability’.

In such settings, the concept of ‘throwntogetherness’, with its practices of mixing, indifference and coexistence (albeit governed by exploitive and oppressive capitalist regimes), appears like a distant mirage. In times of rapid change and crisis, as experienced at present by economic austerity, nationalism and the Covid-19 pandemic, the intrinsic openness of urban space drives authorities and political elites to adopt practices and policies to border the ‘unwanted irremovable’ groups (Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy Citation2018; Yiftachel Citation2015). In this vein, and in order to complete the vocabulary of Massey's conceptualisation, we join Abuzaid and Yiftachel (in this Special Feature) in conceptualising this condition as ‘urban thrownapartness’. While Massey (Citation2005) never implied harmony or peaceful coexistence in throwntogetherness, and what the concept denotes is oftentimes fraught with tension and conflict, adopting this lens creates a more explicit conceptual continuum. In this Special Feature, we show that thinking between the poles of throwntogetherness and thrownapartness and the assemblages produced by their dialectic negotiation, helps fathoming the various dynamics outlined in the individual contributions.

A key step to understand the spaces between ‘throwntogether’ and ‘thrownapart’ can be taken by looking at everyday bordering in contemporary cities and how it has been reshaping urban citizenship (Pine Citation2010; Blokland et al. Citation2015; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy Citation2018) ‘through ideology, cultural mediation, discourses, political institutions, attitudes and everyday forms of transnationalism’ (Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy Citation2018, 229). De Genova (Citation2015) has argued that the city is a primary site of extending the physical (national) border into the everyday. What he terms the ‘migrant metropolis’ has become ‘the premier exemplar, simultaneously, of the extension of borders deep into the putative ‘interior’ of the nation-state space (…) and of the disruptive and incorrigible force of migrant struggles that dislocate borders and instigate a re-scaling of border struggles as urban struggles’ (Citation2015, 3). Indeed, the city is where the state power meets the people in the everyday, ordinary and increasingly hostile settings to migrants and minority communities.

Digitising the urban

Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, we have seen a rapid increase in the dependence of cities on digital technologies mobilised by the expansion of the Internet, social media, and digital service provision, control and surveillance (further accelerated during the Covid-19 pandemic). The ‘digitisation’ of urban management and politics is a new development in a long appreciation of the connection between materialities, technologies, discourses, capabilities and geographies in the ceaseless making of urban ‘dispositif’ (Foucault Citation1977). As articulated by Foucault (Citation1977), and later in a different way by Massey (Citation2005), such a process combines dynamic material-discursive interconnections that produce ‘apparatuses’ or ‘geometries’ of power to shape and reshape urban society.

Given its rapidly growing accessibility and multi-directionality, the recent digitisation of the city adds a significant new dimension to debates on urban citizenship. Urban throwntogetherness is increasingly being experienced, contested and negotiated online (Leurs Citation2014), with a potential for accessibility to services, employment and resources to be offered by new digital platforms. These new spaces are producing distinctively ‘digital’ markers of stratifying difference in terms of identity and ideology as well as new bordering mechanisms deriving from growing ‘digital gaps’ and the ever-increasing ability of authorities for surveillance and punishment (Bork-Hüffer and Yeoh Citation2017; Kitchin, Cardullo, and Di Feliciantonio Citation2020).

While we have room here only to flag this important turn, we should note how it has already inspired a related body of work on the right to the digital city (e.g. Datta Citation2018; Foth, Brynskov, and Ojala Citation2015). Estrada-Grajales (Citation2019), for example, has shown that urban citizens are likely to deepen their political potential as city-makers by using digital media and other technological means. In his own words, ‘cities are imaginatively constructed by their inhabitants, and (…) people craft meaningful narratives of both their realities and their lived space [online]’ (Estrada-Grajales Citation2019, 54). Thus, digital technologies seem to have an empowering potential and give people a much-needed agency to shape the city, particularly migrant, minority ethnic and marginalised communities whose voices historically have tended to be ignored by policy-makers (Datta Citation2018). We need to recognise this potential in our efforts to create sustainable and just cities.

Hostile (urban) environments

As noted, both neo-nationalism and the digital city provide crucial foundations for understanding urban hostile environments. The term ‘hostile environment’ was initially devised in 2012 by Theresa May in her capacity as then UK Home Secretary to describe the policies of making the country inhospitable for immigrants (Tyler Citation2018). By being embedded in everyday urban spaces such as schools, hospitals, workplaces and homes, these hostile policies mobilise practices of bordering, surveillance and discipline, and contribute to inequalities and injustices. In practice, this means that immigrants are likely to face regular checks, for instance, when they open a bank account, apply for a job, accommodation or seek health services. In the UK, they also face prohibitive fees for visas and the Indefinite Leave to Remain (i.e. permanent residency) or naturalisation applications. In addition, they can have their details passed to immigration enforcement if they witness a crime and, if found to be living illegally there, face the prospect of detention and deportation (de Mars et al. Citation2018). Importantly, not all migrant groups are subject to such a stringent immigration regime. For example, citizens of the European Union countries were until recently exempted from such treatment (although this has changed since January 2021 in the aftermath of Brexit). This creates problematic hierarchies of privilege between migrant populations, including the production of what Burrell and Schweyher (Citation2019) have termed ‘conditional citizens’.

Reflecting on the UK context, de Mars et al. (Citation2018) argue that the potential for the hostile environment policy to ‘go wrong’ is considerable. The system’s flaws were particularly exposed in 2018 when the Windrush Generation of Commonwealth Caribbean migrants with a historic entitlement to live in the UK were asked by the Home Office to prove their status (or face deportation if unable to do so) (Gentleman Citation2019). It is also important to emphasise that the execution of this policy is oftentimes delegated by the Home Office to private and unqualified parties (e.g. landlords, employers) under the threat of punishment, which increases the risk of mistake as well as discriminatory treatment. Effectively, not only those who are immigrants are prompted to verify their status, but also those who ‘appear’ to be ones (de Mars et al. Citation2018; Yuval-Davis, Wemyss, and Cassidy Citation2018). This raises a set of challenges closely related to racism, xenophobia and islamophobia, among others, which may cause discrimination and lead to tensions within diverse urban communities. Admittedly, the hostile environment policy has turned UK cities into a ‘brutal migration milieu’ (Hall Citation2017) with significantly increased levels of surveillance and social control (Crawford, McKee, and Leahy Citation2020).

This ‘authoritarian turn’ (Tyler Citation2018; Clements Citation2018) in immigration policy stretches far beyond the UK. Examples abound: Donald Trump’s administration in the US (2017–2021), Viktor Orbán’s in Hungary and Law and Justice party (PiS) in Poland all use(d) the rhetoric of ‘walling’ the state against migrants and refugees (Szabó Citation2018), similarly to Australia's ‘stop the boats’ rhetoric (Martin Citation2015), Narendra Modi's citizen registration policy in India (Wagner and Arora Citation2020), China’s hukou system (Wu Citation2010; Zhao Citation2022) or Israel's and Singapore's attempt to strictly limit labour migration (Parreñas, Kantachote, and Silvey Citation2021). This is accompanied by violent forced displacements in countries such as Syria, Afghanistan, South Sudan, Myanmar, Somalia and Ukraine, and the simmering of the European migration crisis.

Contributions

Accordingly, the contributions in this Special Feature are adapting, extending and re-contextualizing the definition of throwntogetherness from a range of perspectives. The papers provide evidence on how urban societies experience hostility in everyday contexts including migration, religion, poverty, social movements, nationalism, indigeneity and gender, and how combinations of ‘throwntogetherness’ and ‘thrownapartness’ (after Abuzaid and Yiftachel in this Special Feature) shape urban societies worldwide.

Giuseppe Carta, for example, studies conflicts over mosques in Bologna and Rome by focusing on the meaning of throwntogetherness for Muslim communities. Orlando Woods and Lilly Kong look at the making of (privileged) Christian spaces in Singapore and the interplay of wealth, class and in/exclusion. Anna Gawlewicz takes us to Glasgow in search of urban spaces of inclusive throwntogetherness in the unfolding context of Brexit.

In the spirit of multiple understandings of the emerging urban, we also invited scholars to present visual essays, which capture other aspects of throwntogetherness and hostility. These present more graphic stories of urban in/exclusion, displacement and identity struggles. Shawn Bodden looks at community efforts to create an ‘alternative’ community space in Budapest amid the hostile environment of contemporary Hungarian politics. Huda Abuzaid and Oren Yiftachel bring a view from Palestinian Jerusalem-al-Quds deeply scarred by the spatialities of ‘thrownapartness’. Finally, Tanjil Sowgat and Shilpi Roy explore Dhaka as an ever-urbanising space marked by stark contrasts between the formalised urban rich and ‘informal’ poor.

By focusing on throwntogetherness in hostile urban environments, this Special Feature acknowledges, celebrates, but also moves beyond the generative work of Doreen Massey on space, place and urban society. The volume deals with the new ‘conjunctures’ (a term Massey often employed) faced in cities and their populations in these highly turbulent times. We hope that this collection paves a way towards opening, debating and understanding the new urban, in which all of us – researchers, activists, employers, investors, policy makers and residents – are inevitably throwntogether.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Carlos Estrada-Grajales for his help and support in the development of this Special Feature. We also wish to thank City editors and all anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on this introductory piece, individual contributions as well as the Special Feature as a whole. The production of the Special Feature coincided with the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic: we are very grateful to contributing authors, reviewers, and City for bearing with us during this difficult and most surreal time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna Gawlewicz

Anna Gawlewicz is Lecturer in Public Policy and Research Methods in the School of Social and Political Sciences (Urban Studies) at the University of Glasgow. Email: [email protected]

Oren Yiftachel

Oren Yiftachel is Professor and Lynn and Lloyd Hurst Family Chair of Urban Studies in the Geography Department at the Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 We wish to acknowledge Carlos’ input into the development of this Special Feature. Dr Estrada-Grajales is a digital ethnographer with interest in urban activism, right to the city and migration-driven diversity.

References

- Amin, A. 2012. Land of Strangers. Cambridge: Polity Press .

- Antonsich, M. 2018. “Living in Diversity: Going Beyond the Local/National Divide .” Political Geography 63: 1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2017.12.001.

- Bauböck, R. 2003. “Reinventing Urban Citizenship .” Citizenship Studies 7 (2): 139–160.

- Beck, U. 2004. “Cosmopolitical Realism: On the Distinction Between Cosmopolitanism in Philosophy and the Social Sciences .” Global Networks 4 (2): 131–156.

- Blokland, T., C. Hentschel, A. Holm, H. Lebuhn, and T. Margalit. 2015. “Urban Citizenship and Right to the City: The Fragmentation of Claims .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39: 655–665. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12259.

- Bollens, S. A. 2007. “Urban Governance at the Nationalist Divide: Coping with Group-Based Claims .” Journal of Urban Affairs 29: 229–253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9906.2007.00341.x.

- Bork-Hüffer, T., and B. Yeoh. 2017. “The Geographies of Difference in Conflating Digital and Offline Spaces of Encounter: Migrant Professionals’ Throwntogetherness in Singapore .” Geoforum 86: 93–102. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.09.002.

- Brenner, N. 2019. New Urban Spaces: Urban Theory and the Scale Question. Oxford: Oxford University Press .

- Burrell, K., and M. Schweyher. 2019. “Conditional Citizens and Hostile Environments: Polish Migrants in pre-Brexit Britain .” Geoforum 106: 193–201. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.08.014.

- Clements, K. 2018. “Authoritarian Populism and Atavistic Nationalism: 21st-Century Challenges to Peacebuilding and Development .” Journal of Peacebuilding and Development 13 (3): 1–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15423166.2018.1519354.

- Crawford, J., K. McKee, and S. Leahy. 2020. “More Than a Hostile Environment: Exploring the Impact of the Right to Rent Part of the Immigration Act 2016 .” Sociological Research Online 25 (2): 236–253. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780419867708.

- Crenshaw, K. 1991. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color .” Stanford Law Review 43 (6): 1241–1299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039.

- Datta, A. 2018. “Postcolonial Urban Futures: Imagining and Governing India’s Smart Urban age .” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 37 (3): 393–410. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775818800721.

- De Genova, N. 2015. “Border Struggles in the Migrant Metropolis .” Nordic Journal of Migration Research 5 (1): 3–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/njmr-2015-0005.

- de Mars, S., C. Murray, A. O’Donoghue, and B. Warwick. 2018. Bordering two Unions: Northern Ireland and Brexit. Bristol: Policy Press .

- Desai, R., and R. Sanyal, eds. 2013. Urbanizing Citizenship: Contested Spaces in Indian Cities. New York: Sage .

- Estrada-Grajales, C. 2019. "The Right to the Digital City: The Role of Urban Imaginaries in Participatory Citymaking.” PhD diss., Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane.

- Fincher, R., K. Iveson, H. Leitner, and V. Presto. 2019. Everyday Equalities: Making Multicultures in Settler Colonial Cities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press .

- Finlay, R. 2019. “A Diasporic Right to the City: The Production of a Moroccan Diaspora Space in Granada, Spain .” Social and Cultural Geography 20 (6): 785–805. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2017.1378920.

- Foth, M., M. Brynskov, and T. Ojala. 2015. Citizen’s Right to the Digital City: Urban Interfaces, Activism, and Placemaking. Springer .

- Foucault, M. 1977. What is Dispositif? Foucault Blog: https://foucaultblog.wordpress.com/2007/04/01/what-is-the-dispositif/.

- Gentleman, A. 2019. The Windrush Betrayal: Exposing the Hostile Environment. London: Guardian Faber Publishing .

- Gilroy, P. 2004. After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture? London: Routledge .

- Hall, S. M. 2017. “Mooring “Super-Diversity” to a Brutal Migration Milieu .” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (9): 1562–1573. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1300296.

- Harvey, D. 2008. “The Right to the City .” New Left Review 53, Sept-Oct.

- Harvey, D. 2012. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to Urban Revolution. London and New York: Verso Books .

- James, M. 2015. Urban Multiculture: Youth, Politics and Cultural Transformation in a Global City. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan .

- Kitchin, R., P. Cardullo, C. Di Feliciantonio, et al. 2020. “Citizenship, Justice and the Right to the Smart City.” In The Right to the Smart City, edited by P. Cardullo, 1–24. London: Emerald .

- Leurs, K. 2014. “Digital Throwntogetherness: Young Londoners Negotiating Urban Politics of Difference and Encounter on Facebook .” Popular Communication 12 (4): 251–265. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15405702.2014.960569.

- Martin, G. 2015. “Stop the Boats! Moral Panic in Australia Over Asylum Seekers .” Continuum 29 (3): 304–322. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2014.986060.

- Massey, D. 1991. “A Global Sense of Place .” Marxism Today June: 24–29.

- Massey, D. 1993. “Power-geometry and a Progressive Sense of Place.” In Mapping the Futures: Local Cultures, Global Change, edited by J. Bird, B. Curtis, T. Putnam, and L. Tickner, 59–68. London and New York: Routledge .

- Massey, D. 2005. For Space. London: Sage Publications .

- Mitchell, D. 2003. The Right to the City. New York: Guilford Press .

- Neal, S., K. Bennett, A. Cochrane, and G. Mohan. 2013. “Living Multiculture: Understanding the New Spatial and Social Relations of Ethnicity and Multiculture in England .” Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 31 (2): 308–323.

- Parreñas, R. S., K. Kantachote, and R. Silvey. 2021. “Soft Violence: Migrant Domestic Worker Precarity and the Management of Unfree Labour in Singapore .” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47 (20): 4671–4687, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2020.1732614.

- Pine, A. M. 2010. “The Performativity of Urban Citizenship .” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 42 (5): 1103–1120. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a42193.

- Porter, L., and O. Yiftachel. 2019. “Urbanizing Settler-Colonial Studies: Introduction to a Special Issue – Settler Colonialism, Indigeneity and the City .” Settler Colonial Studies 8 (1): 1–10.

- Roy, A. 2011. “Slumdog Cities: Rethinking Subaltern Urbanism .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 35 (2): 223–238. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01051.x.

- Sassen, S. 2000. “Spatialities and Temporalities of the Global: Elements for a Theorization .” Public Culture 12 (1): 215–232.

- Sassen, S. 2016. Expulsion: Brutality in the Global Economy. Cambridge: Harvard University Press .

- Szabó, ÉE. 2018. “Fence Walls: From the Iron Curtain to the US and Hungarian Border Barriers and the Emergence of Global Walls .” Review of International American Studies 11 (1): 83–111.

- Tyler, L. E. 2018. “Deportation Nation: Teresa May’s Hostile Environment .” Journal for the Study of British Cultures 25 (1), (early view).

- Valentine, G. 2008. “Living with Difference: Reflections on Geographies of Encounter .” Progress in Human Geography 32 (3): 323–337.

- Valluvan, S., and V. Kalra. 2019. “Racial Nationalisms: Brexit, Borders and Little Englander Contradictions .” Ethnic and Racial Studies 42 (14): 2393–2412. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2019.1640890.

- Varsanyi, M. W. 2006. “Interrogating “Urban Citizenship” vis-à-vis Undocumented Migration .” Citizenship Studies 10 (2): 229–249.

- Vertovec, S. 2007. “Super-diversity and its Implications .” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (6): 1024–1054.

- Vieten, U. M., and G. Valentine. 2015. “Special Feature - European Urban Spaces in Crisis: The Mapping of Affective Practices with Living with Difference .” City 19 (4): 480–485. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2015.1051731.

- Wagner, C., and R. Arora. 2020. “India's Citizenship Struggle: The Modi Government Pushes its Nationalist Agenda .” SWP Comment 3: 2–4.

- Wessendorf, S. 2014. Commonplace Diversity: Social Relations in a Super-Diverse Context. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan .

- Wilson, H. F. 2015. “An Urban Laboratory for the Multicultural Nation? ” Ethnicities 15 (4): 586–604. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468796815577703.

- Wise, A., and S. Velayutham, eds. 2009. Everyday Multiculturalism. Springer .

- Wu, W. 2010. “Drifting and Getting Stuck: Migrants in Chinese Cities .” City 14 (1-2): 13–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810903298490.

- Yiftachel, O. 2009. “Theoretical Notes On ‘Gray Cities’: The Coming of Urban Apartheid? .” Planning Theory 8 (1): 88–100.

- Yiftachel, O. 2015. “From Gray Space to Metrozenship: Reflections on Urban Citizenship .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (4): 726–737.

- Yiftachel, O. 2016. “The Aleph—Jerusalem as Critical Learning .” City 20 (3): 483–494.

- Yiftachel, O. 2020. “From Displacement to Displaceability: A Southeastern Perspective on the New Metropolis .” City 24 (1-2): 151–165.

- Yiftachel, O., and N. Cohen. 2021. “Defensive Urban Citizenship: A View from Southeastern Tel Aviv.” In Theorising Urban Development from the Global South, edited by A. K. Mohan, S. Pellissery, and J. Gómez Aristizábal, 149–174. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan .

- Yiftachel, O., and H. Yacobi. 2003. “Urban Ethnocracy: Ethnicization and the Production of Space in an Israeli ‘Mixed City’ .” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 21 (6): 673–693. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/d47j.

- Yuval-Davis, N., G. Wemyss, and K. Cassidy. 2018. “Everyday Bordering, Belonging and the Reorientation of British Immigration Legislation .” Sociology 52 (2): 228–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038517702599.

- Zhang, L. 2002. “Spatiality and Urban Citizenship in Late Socialist China .” Public Culture 14 (2): 311–334.

- Zhao, Y. 2022. “The Porous Urban .” City 26 (1): 1–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2022.2041291.