Abstract

Today, the landscapes of Asia—and Southeast Asia in particular—are undergoing major transformations, many of which are due to urbanisation processes that impact coastal areas. These are often controversial reclamation projects, generically referred to as the ‘war of sand’—an (in)visible conflict named for the raw material used to develop artificial land for property development. In Malacca, Malaysia, coastal urbanisation engenders serious environmental damage via the elimination of mangroves, deterioration of water quality and marine ecosystems, and erosion. It also causes severe social and economic transformation that leads to specific social dynamics marked by the marginalisation of certain ethnic minorities. This invites us to rethink the right to the city and the landscape in the moment of reclaiming land. For this purpose, this article describes how coastal development and reclamation projects are heavily mining local communities and the environment. The sand war, it turns out, is not purely a resource-grabbing conflict nor a real estate process with heavy environmental implications, but an implicit war against ethnic and religious communities. Inequality is a consequence not by accident but by design.

1. Land of sand

Today, the landscapes and urban areas of Asia—and Southeast Asia in particular—are undergoing major transformations. Many of these changes are the result of urbanisation processes that impact coastal areas. Emulating what has taken place in Singapore, Japan, and Hong Kong, several countries are creating new land, using ‘sand’ as construction material. The greedy request for sand gives rise to gruelling ‘sand wars’ (Delestrac Citation2013) among sand smugglers, real estate developers, politicians, and the local population. Nowhere is this more apparent than in Malaysia, specifically in the cities of Penang, Johor and Malacca.

Sand is a precious natural resource that enables land to be reclaimed from the sea by constructing artificial islands and peninsulas on which to pursue profitable real estate development. Sand is also essential for the construction market because it is needed to produce concrete (i.e. by mixing it with cement, water and gravel), and buildings, highways, airports and dams require large quantities of sand as their primary raw material. According to a 2014 report by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP Citation2014), global cement production tripled between 1994 and 2012, rising from 1.37 to 3.7 billion tons annually; this increase was principally driven by property development in Asia. In 2012, concrete production for the global construction sector used between 25.9 and 29.6 billion tons of sand extracted from quarries, rivers and coastal areas (Pedruzzi Citation2014; Beiser Citation2018). Sand for artificial coastal melioration projects is often obtained by dredging the nearby seabed, natural islands, or rivers but in some cases, natural resources may also be smuggled in (UNEP Citation2014). Singapore, for example, has expanded its surface area by 22% in just years mainly by using sand from Malaysia, Cambodia and Indonesia (UNEP Citation2014, Citation2019). The Mekong Delta in Vietnam, Lake Poyang and the Ayeyarwady River in Myanmar, and Guangdong, Guangxi and Fujian provinces in China are some of the (il)legal sources of the sand used in Asia and its removal inevitably compromises the origin countries’ landscapes (UNEP Citation2014, Citation2019). The other face of this phenomenon is widespread environmental damage and its inevitable socioeconomic repercussions—fishing decline, soil erosion, water pollution and the destruction of native flora and fauna.

Although sand is a vital material in spatial and urban processes, the impact on the urban landscape and social systems is infrequently studied with a gaze that goes beyond the rhetoric of sand flows in a system of ‘planetary urbanisation’ (Brenner and Schmid Citation2012, Citation2015). This article attempts to interpret the role of sand in reclamation projects starting from below by monitoring the transformations of places and people from the ‘land of sand’ of Malacca, Malaysia. I argue that landscape transformation and reclamation projects in Malacca—and likely throughout Malaysia and other countries in Southeast Asia—mark a neo-colonisation of space by supranational capitalist forces often and (un)deliberately inflicted on ethnic-religious minorities. The sand war is not purely a resource-grabbing conflict nor a real estate process with heavy environmental implications, but an implicit war against ethnic communities. However, some questions remain: Who/what is expropriated in the remediation process? Who/what is involved in this process and what are its consequences? What types of power structures underlie these processes and on what scales do they operate?

The research mostly relied on fieldwork because the site lacked information and/or consolidated literature. An in-depth survey was conducted in the 2017–18 academic year and partly originated from a semester-long design process in the Malaysian region that involved students in landscape architecture from a university in Singapore. Before starting the design course, I travelled along the coast and spent some months in Malacca, observing the places and dynamics of transformation and getting to know local people and culture. The methodology included the observation and study of different scales as starting points for decoding the sand cycle: from sand extraction in the sea to its delivery along the coast, from its environmental and spatial effects to the social effects on local communities. This approach sometimes overlapped with ‘action research’ (Greenwood and Levin Citation1998) and participatory techniques in the design project that I will not discuss as they are not the objective of this article.Footnote1

I relied on multiple sources of information to write this article. First, on-site investigations constituted the cornerstone of knowledge production of the places I visited. The survey included photographic investigations and, due to data scarcity, the sampling and study of living materials, such as water quality or plant species that may help us understand the phenomena related to sand extraction. After spending a period of study in Malacca before the beginning of the course, I returned with my students to start a collective exploration phase organised in working groups in different parts of the region. We shared information, photos and observations and, with time, my original gaze transformed with various pieces of evidence and answers to the questions that I did not dare to ask others or myself.

The other source of knowledge came from interviews with local people. I contacted ethnic minorities afflicted by the reclamation works. Our meetings were held in several places in Malacca and Singapore, including a research centre for architectural and urban heritage, the Portuguese Settlement of Malacca and a coastal Chinese–Malay fishing village. We had our last meeting on campus in Singapore, as part of the final phase of project presentations by students. Unfortunately, despite my efforts and many requests, I was unable to interview local authorities and foreign real estate companies in the reclamation areas. The research also involved mappings of landscape and urban systems (Cipriani Citation2018). Finally, urban studies literature and non-academic sources, such as newspapers and documents, helped me to understand the mechanisms underlying the ‘land of sand’ projects.

The article is structured as follows: In the first part, I describe the different meanings of the term ‘reclaim’ as a powerful means of sovereignty and colonisation of space that undermines the identity of local populations. Drawing on Lefebvre, Kofman, and Lebas (Citation1996), I want to emphasise the political dimension of the right to reclaim the city. This could also be put into further dialogues with recent urban studies literature that addresses the ‘materiality’ issues (Gastrow Citation2017; Choplin Citation2020; Pilò and Jaffe Citation2020; Dawson Citation2021), as sand is also a critical material that allows for interpreting encountered spatial and social phenomena. In the second and third sections, I refer to the case study of Malacca to elaborate first the physical and environmental consequences of the sand reclamation action and then the social impacts of such alterations. I want to demonstrate that the sand war in Malaysia is not just a war against the environment but a socioeconomic war that implies ethnic-religious dynamics of exclusion. Finally, I explore how this ‘land of sand’ has nurtured new and unexpected social practices after the halt of the reclamation and construction work. The practices of everyday life (De Certeau Citation1984) that today occur on this reclaimed land signal a possible future of land reappropriation that goes beyond capitalist and exclusionary dynamics, where local experiences might be transformed into the elements of new life and hope for the ‘land of sand’ and its communities.

2. Reclaiming the materiality of sand

In urban planning literature, the word ‘reclaim’ is used in many contexts and has multiple meanings. ‘Reclamation’ is primarily a physical operation that creates new land. The reclamation of coastal land involves sequestering space in the sea to develop new land for various purposes (Bo and Choa Citation2004). Historically, populations that have settled on coasts have carried out reclamation to facilitate transport and trade, improve the territory’s defences or remove insalubrious marshland. The impact of coastal urbanisation in Asia has been so rapid that today, Asia has the most coastal cities of any continent (United Nations Citation2015; Firth et al. Citation2016). Notably, Singapore, Japan and Hong Kong have conducted major coastal reclamation projects to overcome land scarcity, and more recently, this phenomenon has extended to the construction of entire islands in Asia and the Middle East (Burt et al. Citation2010; Chee et al. Citation2017); here, sand infilling goes hand in hand with the construction of entire high-density neighbourhoods, usually driven by real estate investments. Many environmental papers criticise and document the consequences of reclamation in natural habitats (Airoldi et al. Citation2005, Citation2009, Citation2015; Chee et al. Citation2017). The disappearance of mangrove forests, salt marshes and wetlands in coastal areas is strongly correlated with the loss of the natural connectivity between marine and terrestrial systems, the disappearance of biodiversity and the inability of coasts to attenuate waves and mitigate the effects of climate change. Sand infills for reclamation processes, therefore, not only threaten today’s environmental balance but also compromise the near future of the coasts, especially considering the climate changes currently underway.

‘To reclaim’ also means to take something back that has been lost. ‘Reclaiming the city’ (Lefebvre, Kofman, and Lebas Citation1996; Harvey Citation2008) in urban planning literature refers to the response to the loss of the use of urban spaces; in this context, to ‘reclaim’ means to advocate for city planning that favours the interests of its inhabitants—a ‘city for people, not for profit’ (Brenner, Marcuse, and Mayer Citation2009)—which eventually culminates in forms of active resistance. Over 40 years ago, Henri Lefebvre wrote that capital accumulation and industrialisation processes engendered a socio-spatial crisis in cities (Lefebvre, Kofman, and Lebas Citation1996), asserting society’s ‘right to the city’ as well as to nature and habitat—a principle that has once again become extremely topical and applicable to what is happening in many fragile environmental and social contexts (Lefebvre, Kofman, and Lebas Citation1996).

Over the last few years, the right to nature has, rather strangely, entered into social practice as a result of leisure activities, having emerged from ever-more commonplace protests against noise, fatigue, and the concentrationary universe of cities (as cities are rotting or exploding). A strange journey indeed! Nature is included among exchange value and commodities, something to be bought and sold. This ‘naturality’ which is counterfeited and traded in, is [in fact] destroyed by commercialized, industrialized and institutionally organized leisure pursuits. ‘Nature,’ or what passes for it, and survives for it, becomes the ghetto of leisure pursuits, the separate place of pleasure and the retreat of ‘creativity.’ (Lefebvre, Kofman, and Lebas Citation1996, 157–158)

The third meaning of ‘reclaim’ refers to a process of places losing their identity. Chang and Huang (Citation2011), referring to the Singapore waterfront projects, distinguish between the reclamation of functionality, accessibility, and local spaces ‘where history and cultures are commemorated.’ This was undoubtedly linked to Lefebvre’s denunciation but acquired special acclaim in Asia’s multicultural contexts, especially in Malaysia and the city of Malacca, where different societies and cultures are often segregated (Sidhu Citation1983). Malaysian society is based on strong and differentiated cultural, ethnic, and religious identities, strengthened and made extreme by a series of policies that favour the Islamic community and consequently discriminate against other minorities.

Despite being of the same nationality, most Malaysians see themselves in ethnic terms first, especially concerning their relationship with other individuals of different ethnicities. This is primarily due to the way the social dynamics are arranged, with heavy political and socioeconomic deprivation undertones. This state of affairs has given rise to increased ethnic consciousness among Malaysians. The country’s Bumiputera policy, which accords preferential treatments that strongly favor the majority ethnic Malay over others, has been blamed for Malaysia’s racial problems since its inception in 1957. The asymmetrical status relations among ethnic communities that manifest in almost all spheres of life have solidified the feeling of social exclusion among minorities, in a situation where individuals are disfavored or denied access to rights, opportunities, and resources other groups enjoy. (Moorthy Citation2021, 555–556)

The second line of study that I believe can contribute to a better understanding of the situation is the role of materiality. A series of recent articles (Gastrow Citation2017; Choplin Citation2020; Pilò and Jaffe Citation2020; Dawson Citation2021) have suggested that following the traces and processes of matter helps to explain the dynamics of urbanisation.

There are two interpretations of materiality that are both related to the different meanings of reclamation. The first relationship between materiality and reclamation is what Pilò and Jaffe (Citation2020) define as ‘political materiality.’ This line of inquiry invites us to reflect on how the notions of citizenship and individual and collective recognition are mediated by the material objects of the city. In Niger, for instance, the choice to build a house in concrete in the informal slums, rather than with less durable materials, offers a form of permanence and underlies the recognition of some rights, status, and legitimacy of the inhabitants (Körling Citation2020). And in Rio de Janeiro, residents of favelas usually receive electricity through illegal connections. The first bills by the electricity supply companies become the first recognition and implicit legalisation of their presence and their homes since their electricity bill can be used as a proof of address (Pilò Citation2020). And in this sense:

Non-human entities are mobilized within normative projects that seek to redefine the concept of ‘productive’ or ‘respectable’ citizen, or that delimit who is allowed to inhabit and act on the urban landscape. Things play a central role in the formulation, implementation, and contestation of ‘citizenship agendas,’ the normative framings that prescribe what norms, values, and behavior are appropriate for those claiming membership in a political community. (Pilò and Jaffe Citation2020, 13)

The other relationship between materiality and reclamation is linked to the fact that the reclamation process is a physical operation that uses a precise material—sand in this case. Sand is the construction material that allows reclamation. Following the process of extraction, transport, and capitalisation of the physical resource, we can understand the environmental, political, and social implications of urbanisation processes. For instance, Choplin (Citation2020) retraces the itinerary of cement bags from the plant to the plot, observing all the actors and processes involved in the cement chain between Accra, Lomè, Cotonou and Lagos. In a similar vein, Dawson (Citation2021) presents an analysis of the urbanisation of sand, or the ways in which sand is brought into the urban realm, grounding this reading in the city of Accra, Ghana. In both studies, it turns out, a follow-the-thing process is important to witness the making of the urban. In fact, in any design and planning process, every decision has an impact not only on the construction site but also on the extraction and production site. The asphalt of road infrastructure, the construction of a brick wall, and the tree species of an avenue make us reflect how the choices on the materiality of the built environment have a global chain effect. The materials that make up homes, infrastructures and ultimately cities have an impact on local natural systems and cascade on the populations that inhabit them or in some way benefit (or suffer) from them. If we pursue the process of extraction, transport and re-elaboration of each resource, we soon realise that each urban material should lead us to rethink cities and people’s lives. In this sense, the case of Malacca is exemplary because the sand reclaimed, extracted, and transported along the coast to create a new urban settlement destroys the coastal environment of mangroves, undermines the economic subsistence of the local inhabitants, thereby compromising their social identity and economic base.

The mechanisms of matter and materiality must also be addressed in terms of scale. The multi-scalar nature of the operations of extraction, consumption, accumulation and transport extends to the planetary level and invites a transnational analysis while requiring an investigation of local urbanity at different scales of intervention. The global flows of sand invite reflections on the concept of ‘planetary urbanization’ (Lefebvre Citation1970; Brenner and Schmid Citation2012, Citation2015), and I believe that the close study of places can reveal unexpected phenomena unidentifiable at first sight. An appropriate example is the small-scale approach of Moreno-Tabarez (Citation2020), who tells a story of corruption in the sand dredging of rivers in Latin America, the environmental consequences of which harm coastal fishing communities. Such micro-stories related to materiality reveal a greater richness and precision in the interpretation of the urban and highlight unusual and particularly critical perspectives. Against this background, this article intends to tell the story of the city of Malacca, Malaysia, its territory and its people.

3. Reclaiming the sea and the landscape in Malacca, Malaysia

The sea, coast, mangrove forests and rivers shaped the urban development of the city of Malacca from its early settlements. The city’s strategic geographical position between China, India and Indonesia gave rise to its multicultural development based on maritime trade and commerce (Widodo Citation2004, Citation2011). Malacca emerged as an important seaport during Portuguese colonisation in the 15th century but underwent a slow and long decline under Dutch (mid-17th to mid-19th century) and then English (mid-19th to mid-20th century) domination when much of its trade was lost to other port cities, such as Jakarta and Singapore. The foreign domination ended with the declaration of the city’s independence in 1946 and subsequently Malaysia’s complete independence in 1957, but the city continued to play only a peripheral role in Southeast Asia’s trade routes.

Following Malacca’s designation as a UNESCO heritage site in 2008, the city became a hub of mass tourism, and real estate speculation is now rife along the coast in the form of large-scale reclamation operations aimed at snatching land from the sea. The controversial ‘Melaka Gateway’ project aimed to construct a peninsula and three artificial islands to host a deep seaport, a cruise terminal, a marina for yachts and several theme parks and residential settlements. The project’s reclamation work was part of the Chinese ‘One Belt One Road’ infrastructural plan aimed at re-establishing a sea route between Asia and Europe, a 21st-century silk road whose nodal ports would host a series of satellite citadels for tourists. China’s geopolitical strategy also intended to shift the port traffic headed for Singapore to a series of ports on Malaysia’s east and west coasts, which would also be serviced by a new railway, the East Coast Rail Link. The city of Malacca could therefore re-establish its vocation as a port-city after centuries of neglect. However, this newfound role was to once again be dominated by foreign forces as the construction of the ports and railways was largely financed by Chinese banks so that they would remain Chinese if the Malaysian government was unable to service its loans (Embong, Evers, and Ramli Citation2017).

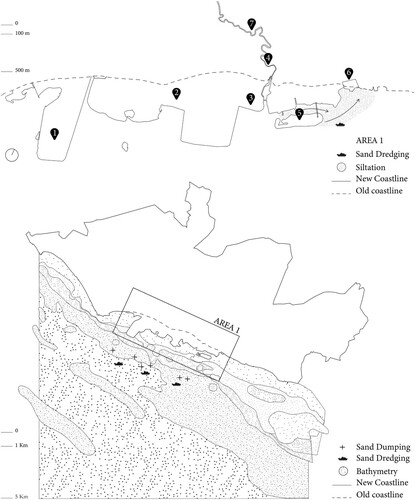

The Melaka Gateway project was established on 7 February 2014 from a direct decree of Malaysia’s then–Prime Minister Najib Razak after a visit to China (Wade Citation2020). Work commenced in 2016 with the first coastal reclamation measures in the areas of Pantai Klebang, Pekan Klebang, Taman Kota Laksamana, Pulau Melaka, Permatang Pasir Permai and Telok Mas (see ). However, the preparations for the project did not involve the local communities (Yusup et al. Citation2016). The plan was a simple expression of the forces of global capitalism, which made even the Malaysian government bend its own stringent rules. Thus, a 99-year concession was granted for the port’s development instead of the usual 30-year grant issued for such interventions. The reclamation conformed to the ‘Town and Country Planning Act 1976,’ (Act 172), which categorises land reclamation as ‘development’ activity (Laws of Malaysia Citation2014; Yusup et al. Citation2016).

Figure 1: Location map at the regional and local scale. 1. Pantai Klebang; 2. Pekan Klebang; 3. Taman Kota Laksamana; 4. Melaka City Center; 5. Pulau Melaka; 6. The Portuguese Settlement; 7. Melaka River. Image: Laura Cipriani 2022.

Coastal reclamation in Malaysia was first initiated—albeit on a much smaller scale—in the 1920s and continued into the mid-1970s and 1980s in the Bandar Hilir and Tranquerah areas. However, in recent years, major Chinese investments have considerably accelerated these interventions. The Melaka Gateway project was therefore the most recent to alter the coastline, and its impact and dimensions compromised the environmental assets of the area and forever erased the localities’ historical identity. The many historical buildings that once snaked along the former coastline (now swallowed up into the hinterland) bear witness to a past where the sea was a major protagonist (Cipriani Citation2018, Citation2021). These now mainly abandoned buildings recount the coast’s historical development and successive advancement. Similarly, cartographic surveys (Cipriani Citation2018, Citation2021) show a series of monumental trees that once marked the contours of the old coastline, and which are now an integral part of the city’s urban fabric. Old postcards (Wong Citation2011) show that the trees were an identifying element for fishermen and inhabitants, enabling them to pinpoint their moorings when still far at sea. Shells and sea leftovers can still be collected in the hinterland when walking along the old coastline (see ).

Figure 2: Shells and sea leftovers that were collected in the hinterland along the old coastline in Malacca. Photo: Laura Cipriani 2017.

The still incomplete reclamation projects in the Klebang peninsula, marked by mounds of stacked sand (see ), testify to the threat currently posed to the environment. Satellite images (Esri Community Maps Contributors et al. Citation2016) have documented the phases and processes of excavation operations (see ). Sand is dredged up from the sea, transported on large barges, accumulated along the coast in a series of dunes or piles and finally deposited along the coastal perimeter where a belt of irregular stone blocks attempts to stabilise it. However, the utility of the whole operation is questionable given that erosion is already at work.

Figure 3: Sand dunes on the new artificial coastline, Pantai Klebang Peninsula, Malacca. Photo: Mohd Azrin Roselan 2017.

Figure 4: Sand dredging in Malacca. Image: Esri Community Maps Contributors et al. Citation2016.

The mangrove forest that ran parallel to the coastline has completely disappeared. The vegetation along the coast is bereft of protection, and marine water is polluting the groundwater. Coastal deforestation combined with recent sand dredging makes the surface waters more turbid and intensifies erosion and silting, especially towards the south of the city near the so-called Portuguese Settlement (see ). Zenith images showing the artificial island of Pulau Melaka at an advanced state of construction demonstrate how this new island obstructs the natural flow of water and sediments as well as the silting in the area between the coast and the island. The ‘Environmental Impact Assessment Report Scenario’—a now inaccessible document—determined that the minimum distances between artificial islands and the mainland should be 500 metres for islands facing an unpopulated coast and 750 metres if they faced inhabited centres. Instead, the Melaka Gateway project has a separation channel of just 200 metres between the reclamation islands and the coast—an insufficient distance that visibly contributes to the silting problem in the southern coastal region.

Figure 5: There was the sea. Sand siltation phenomenon off the coast of the Portuguese Settlement. Photo: Laura Cipriani 2017.

The burden of the project falls on a small fishing village left without sea, its economic livelihood, as both freshwater and fish have disappeared. What tangible and intangible forces constitute such reclamation processes? How does sand become an instrument of social exclusion? How do local communities claim their land? The next part will attempt to make sense of the environmental, ecological and social consequences of reclamation processes, specifically focusing on ethnic, racial and religious exclusion.

4. Reclaiming the right to the landscape, nature and life

The Malacca ‘sand war’ is not just being waged on the environment—it is a socioeconomic struggle that indirectly fuels ethnic-religious exclusion. The new land reclamation projects undermine both natural landscapes and the identities and economies of places and people. The silting up of Malacca’s southern coast, the turbidity of its waters and the consequent decline in fishing threaten the economic subsistence of the ethnic Kristang fishing community. The people of this community descend from the first Portuguese conquerors who, in the early 16th century, intermingled with local Malay communities and forced them to convert to Christianity (Bernstein Citation2009). The Portuguese Settlement was formed in the early 1930s when the British government granted a Temporary (and annually renewable) Occupation Licence to the descendants of the colonisers for a plot of land along the coast that allowed them to live together in a single urban nucleus. Thanks to this concession, the Portuguese descendants were able to lift themselves out of extreme poverty and maintain their identities and cultural traditions. However, over time, the community has been progressively marginalised from the rest of the city (Eng Citation1983).

The community has always relied upon fishing for subsistence, but fish is now scarce as a result of recent reclamation work. The inhabitants vehemently voice their right to reclaim nature and life (see ). Martin Theseira, a Kristang fisherman and courageous spokesman for the local resistance, recounted their struggle to save the land, sea and what remains of their identity and history:

My family has been forced to move three times. Now we have lost the sea which we depend on. We can see with our own eyes how the ecology has changed: silting, worse seabed quality, sand dumping, macro-organisms in the mud. When the mud has a grey colour, it is alive; when it is chocolate black, it is dead instead. It is dirt from the sea. (Interview in September 2017)

Figure 6: Martin Theseira, the spokesman for the local resistance recounts their struggle to save the land and sea. Photo: Zhuhui Bai 2017.

It’s a stupid idea that such tall buildings on the seashore are blocking the sunset. The reclamation has totally destroyed the whole fishing industry. We don’t need all these developments. Malacca doesn’t need to be another Singapore. We are already happy with what Malacca was. (Interview in September 2017)

I miss Banda Hilir Park so much. It has now turned into a big shopping mall. The scene of people playing and resting on the football field along the sea was so nice. That’s why I decided to move from Kuala Lumpur and live in Malacca when I was young, but everything is changing now. (Interview in September 2017)

The first concerns the materiality of what has been lost—the sea and the economic subsistence guaranteed by a healthy marine ecosystem. The reclamation initiative of the inhabitants is aimed at attracting the attention of local media in a physical space. In July 2018, approximately 200 Portuguese villagers in Bandar Hilir arranged a mock funeral: a peaceful demonstration to protest reclamation work. Coffins bearing the effigies of fishermen were used to demonstrate the economic struggle of the local economy. Demonstrators complained about the dramatic environmental conditions of the area, specifically the poor quality of the water and accumulation of sediment along the coast that have destroyed the marine ecosystem and, consequently, fishing. The symbol of this initiative—the coffin—has been a taboo element for locals since the early years of the Sultanate of Melaka. Summoning death is synonymous with bad luck, something considered offensive in the local culture. The initiative therefore sought to leverage a traumatic emotional state to raise the attention of the public in a desperate attempt to save their sea and land.

The second claim concerns the right to the city, nature and habitat. When Henri Lefebvre asserted the right to the city at the time of the Parisian riots in the late 1960s, he was reacting to globalised urbanisation. Lefebvre and later Harvey were opposed to various forms of urban planning that exclusively intended to valorise capital investments (Lefebvre, Kofman, and Lebas Citation1996; Harvey Citation2003, Citation2008, Citation2012; Marcuse Citation2009; Purcell Citation2014) without regard to the interests of the local populations. In place of such planning, they proposed that urbanisation should be turned into the city’s transformation via collective power (Harvey Citation2003, Citation2008). The reclamation projects in Malacca epitomise how capitalist logic is prepared to sacrifice and undermine the livelihoods of local communities. It is a type of top-down planning managed by foreigners with little interest in preserving the environment or the local economy. This neo-colonialism relates to profit and perhaps to the implicit corruption of these operations undermines the economic subsistence of the citizens affected by the new interventions.

The ‘land of sand’ became an area in the hands of a foreign company, demonstrating how the Global South is easy prey to the predatory hunger of external powers; and in the long run, it became a geopolitical strategy to control the commercial traffic of Southeast Asia (Embong, Evers, and Ramli Citation2017). Here, the reclamation space is the network between groups and associations that suffer similar injustices in different contexts. The second reclamation therefore consists of the participation of important figures and representatives of other cities in Southeast Asia, such as Penang and Jakarta, that experience similar coastal works. The Save Portuguese Community Action Committee (SPCAC) from Malacca has joined forces with several other environmental groups: Penang Tolak Tambak (Penang Resists Land Reclamation), Kesatuan Nelayan Tradisional Indonesia, Persatuaan Aktivis Sahabat Alam (Friends of Nature Activists Association) of Perak, Kumpulan Indah Tanjung Aru (Tanjung Aru Beautiful Group) and Sabah, Koalisi Selamatkan Teluk Jakarta (Save the Jakarta Bay Coalition). In November 2019, these groups launched and signed the petition ‘Stop Stealing our Seas!,’ a heartfelt denunciation of the unsustainable development of sand reclamation and marine excavation projects and open criticism of the financial and political elite:

We denounce the environmental injustice of such land reclamation projects, which smack of coastal ‘land grabbing’ and ‘sea grabbing,’ designed to benefit the propertied, financial and political elite while marginalizing small-scale fishing communities and society at large. We also denounce the environmental injustice of sand mining projects, which ignores the rights of communities affected by the seabed destruction and ‘destroys one home to build another.’ (Penang Tolak Tambak et al. Citation2019)

modern ‘race relations’ in Peninsular Malaysia, in the sense of impenetrable group boundaries, were a byproduct of British colonialism of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. (…) Direct colonial rule brought European racial theory and constructed a social and economic order structured by race. (Hirschman Citation1986, 330)

After the country gained independence in 1957, Malaysian society became explicitly polarised: the ethnic Malaysian majority enjoyed a special status protected by the constitution, whereas ethnic minorities such as Eurasians and Chinese were treated as second-class citizens (Welsh Citation2020). In 1969, the special rights of the Malaysian community were institutionalised through the idea of ‘ketuanan Melayu’—a political concept that emphasises Malaysian pre-eminence—and the state became a vehicle for maintaining ethnic hierarchies. The institutionalised dominance allowed for the rise of economic inequalities between ethnic communities, favouring racial tensions and rivalry of different religious faiths. From the late 1970s political and economic inequalities accompanied by ethnic, religious and even educational diversity (Welsh Citation2020) intensified the polarisation of society.

I suggest that Malacca’s reclamation projects must also be interpreted through this gaze and in this political context. The systematic social exclusion of Eurasians from today’s political and administrative processes of a country in the hands of a Muslim Malaysian majority means that the Portuguese community must revert to unauthorised and external forms of protest to restate its opposition to top-down projects that ignore shared social experiences. The democratic struggle takes place on various fronts, including a series of local and international resistance networks. Reclamation is therefore no longer a physical act but the assertion of the right to the city, nature and life through a rapid rise in recourse to political action.

For people who have already lost the political battle, losing their identity and identification with their home means losing their last hope; this is perhaps the most intimate motivation for reclamation. Their interpretation and exercise of the right to the city start from the assumption that they will not be heard by politicians or local administrations. Only a super partes, an international or supranational intervention, can help their cause. Hence, the inhabitants claim an ethnic and cultural belonging to Portugal to recruit international support. Through SPCAC, the community presses politicians to resume relations with Lisbon—begun in a town-twinning agreement between Malacca and Lisbon, signed in 1984 to promote cultural and social exchange—as a means of engaging the attention of the European public (Twincities Citation2017). This political space goes back to colonial glories and partly allows for the reclamation of lost identity. Here, the forms of active resistance underpin, in an even more dramatic way, the reclamation of an ethnic-religious minority that wants to fight for its past identity by asking for the recognition that it misses. The demand for clear and just rules that apply to all citizens regardless of ethnicity is implied.

The oppression of past colonialism, institutionalised Malaysian supremacy and subjugation to Chinese capitalist commercial forces in the appropriation of the sea add up and merge in the different levels of demand. Reclaiming the city, the landscape and life involves a continual series of appeals and intermittent victories, which, in various phases, have made it possible to interrupt reclamation operations. Mahathir Mohamad, the then Prime Minister who took office in May 2018, suspended Chinese infrastructure projects, including the contested Melaka Gateway. Publicly he criticised the opaque contracts his predecessors signed and claimed that a ‘new version of colonialism (is) happening because poor countries are unable to compete with rich countries’ (Beech Citation2018). After an initial shut-down of construction sites, the Melaka Gateway project was allowed to continue following an appeal lodged by the company. However, the reclamation operations have slowed, and it currently seems that they have been permanently shut down. In February 2021, the Malaysian Court of Appeal declared that the timetable of the reclamation operations had not been respected and stopped the contractor from proceeding with the work. This occasion demonstrates how the different claims to the right to the city and the landscape sometimes can change top-down plans that do not consider national interests. The Melaka Gateway might be a strategy to control the land, the infrastructural systems and the commercial traffic of the region (Embong, Evers, and Ramli Citation2017). The court’s decision shows how geopolitical and economic conditions can influence the verdict but implicitly, as a second and unexpected result, recognises the claim for identity expressed by ethnic and religious minorities.

Today, the ‘land of sand’ is waiting for its destiny. The suspension decided by the Malaysian government for non-compliance with contractual deadlines seems to have stopped the reclamation projects and, therefore, coastal urbanisation schemes. A bird’s eye view of the artificial peninsula of Klebang reveals a white stripe stretching towards the sea, awaiting further transformation: piles of sand are interspersed with spontaneous vegetation and, in the background towards the city, the concrete skeletons of skyscrapers under construction can be glimpsed rising out of the ground. The future of these areas remains unclear, especially after having undergone a major but incomplete metamorphosis. I believe the answer may be found in the wholly informal processes that have followed one another ever since the halt of the reclamation and construction work.

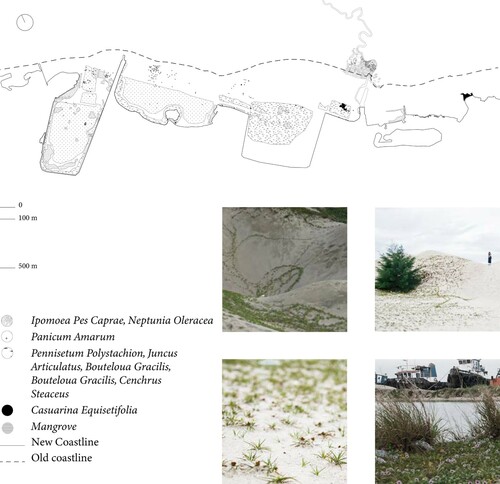

This ‘land of sand’ has nurtured new and (un)expected natural and social practices. The practices of everyday life (see De Certeau Citation1984) that occur in this reclaimed land show a possible future beyond capitalist and exclusionary dynamics. Abandonment has become an opportunity for nurturing new forms of life and use. For example, nature is gradually reclaiming what the projects stole. Waves are washing over and eroding hard stone edges, winds are shifting the dunes and spontaneous vegetation is colonising the sand with pioneer plants (see ): the creepers of Ipomoea Pes Caprae; the perennial herbs of Panicum Amarum, Pennisetum Polystachion, Juncus articulatus, Bouteloua gracilis and Cenchrus Setaceus; the aquatic grass with creeping stems of Neptunia Oleracea; and the spontaneous trees of Casuarina Equisetifolia are just a few of the species found on site.

Figure 7: Pioneering plants in the Pantai Klebang peninsula. Image: elaborated by Yitong Wu under the supervision of Laura Cipriani, National University Singapore NUS, 2017. Edited by Laura Cipriani Citation2021.

Secondly, a new tourist phenomenon is reclaiming the artificial peninsula in a new and unexpected way (see and ). Many informal visitors have posted pictures online of what passes as the ‘Melaka desert.’ Over 80 comments on Tripadvisor have promoted Pantai Klebang, the top corner of the island famous for its white dunes where you can practise ‘desert surfing,’ take wedding photos or simply spend an afternoon. The dunes of the reclamation areas attract hordes of new tourists wanting to discover one of the city’s unexpected attractions. The Indonesian phrase ‘Pasir Cantiki’ (‘Beautiful Beach’) has been written on a concrete relic complete with a directional arrow to reclaim this land of sand’s unexpected future. The new colonisation by natural forces (see ) and tourist experiences will perhaps become an element of new life and hope for the land of sand and its communities.

5. Conclusions: reclaiming the (un)expected

This article has investigated the story of a ‘land of sand’ in Malacca, one of the many controversial coastal reclamation projects in Southeast Asia. It reveals how landscape alterations hold subtle, underlying levels of meaning. Sand is a critical material that allows the sea to be transformed into land and is a powerful means of a new colonisation of space, encompassing environmental, economic, social and even racial conflicts. Referring to recent discussions in urban studies literature that work with ‘materiality,’ I have explored the physical, social, and political dimension of the right to claim the city and the landscape starting from sand. Reclaiming is a process of loss and dispossession. ‘To reclaim’ is the response to the loss of the right and the use of urban and landscape spaces (Lefebvre, Kofman, and Lebas Citation1996; Harvey Citation2008) as well as of identity (Chang and Huang Citation2011). Through the lens of ‘political materiality’ (Pilò and Jaffe Citation2020), this paper further illustrates how and how far the notions of citizenship and recognition are mediated by the materials of the city. Here, sand symbolises the capitalist power that destroys the coastal landscape and thus becomes the driver of the reclaim against top-down urbanisations that result from private interests. Following the operations of extraction, transport and capitalisation of sand (Choplin Citation2020; Dawson Citation2021), we can understand better the urban, environmental, political and social implications that are involved in this process.

The war of sand is first and foremost a physical war against the environment and the landscape. Sand dredging and the destruction of coastal areas have many ecological consequences at different scales, accelerating erosion and devastating marine flora and fauna habitats, which are already at risk due to climate change. Sand extraction, transport and sedimentation destroy the marine environment and damage the coast. The new artificial island obstructs the natural flow of water and sediments as well as the silting in the area between the coast and the island. The mangrove forest that ran parallel to the coastline has completely disappeared. Coastal deforestation combined with recent sand dredging makes the surface waters more turbid and intensifies erosion and silting. As a result, both freshwater and fish disappeared, undermining the Portuguese village’s economic base.

Reclaiming is nevertheless also a political act, in addition to the physical interventions in ‘the war of sand.’ Reclamation projects are led by supranational capitalist forces indifferent to local communities. Ecological devastation, socioeconomic neglect, and a top-down approach to planning disinterested in the needs of inhabitants, perhaps encouraged by corruption, characterise the interventions along the Malacca coast. Foreign powers—the Chinese in this case—aim at large-scale geopolitical spatial appropriation by establishing commercial infrastructural networks and have found fertile ground for their plans in the Global South. The ‘land of sand’ in Malacca demonstrates how these countries are easy prey to external powers and how the projects linked to the ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative and the like can become a geopolitical strategy to implicitly control such countries as well as the commercial traffic of Southeast Asia.

In addition, the sand war also has an economic-social dimension, inducing local ethnic-religious dynamics of exclusion. The case study reveals that a precious and underestimated material has localised implications that are invisible on the macro-scale of planetary urbanisation. Landscape transformation and reclamation projects are deliberately inflicted on certain ethnic-religious minorities. The sand war is not simply a battle for grabbing resources or an infrastructural real estate intervention with heavy environmental implications but an implicit war against certain ethnic communities through targeted racial supremacy policies. In the process of reclamation, the Portuguese fishing community is dispossessed of the view of the sea, robbed of fishing and their subsistence work, and even deprived of the possibility of changing their circumstances by claiming the right to a different way of urban life.

Finally, the abandoned ‘land of sand’ shows how (un)expected landscape and social phenomena can sometimes develop a second life in such places and maybe become future hope for its communities. The artificial peninsula has encouraged natural and social practices that go beyond capitalist and geopolitical dynamics. Nature is gradually reclaiming what the projects stole, eroding hard stone edges, shifting the dunes, and colonising the sand with pioneer plants. New forms of tourism take place on the reclaimed peninsula.

This case can induce theoretical and methodological implications for further research in landscape and urban studies. I think three main lines of inquiry can be drafted. First, the political economy of urbanisation in the context of China’s ongoing belt and road initiative can lead to further inquiries along the sea route and its intercepting countries and cities. Landscape, urban, economic, social and geopolitical impacts of the ‘One Belt One Road’ project might show similarities, differences and specificities on each site involved. Secondly, the physical and political materiality of sand can induce further reflections in urban and landscape research starting from multiple raw materials that compose our environments. The processes of exploitation and transfer of materials are strictly related to the destruction of our landscapes and the construction of our cities. Regarding this approach, the materiality of urban changes emphasises how the notions of citizenship and individual and collective recognition or, in this case, non-recognition, are mediated by the material objects of the city (Pilò and Jaffe Citation2020). Sand symbolises capitalist power and is the driver of the reclamation. Adopting a follow-the-thing approach (Choplin Citation2020; Dawson Citation2021) shows that the materials that make up cities impact local natural systems and cascade on the populations that inhabit them or benefit from them. All this should lead us to rethink the material politics of cities and people’s lives therein.

Thirdly, I hope this paper will lead to further studies on how the landscape and its design can become the means to screen dynamics of exclusion. Design is never a neutral operation. Landscape and urban transformations can hide social and sometimes even racist implications. Only the close study of places can reveal unforeseen phenomena unidentifiable at first sight. The sand war, it turns out, is not purely a resource-grabbing conflict nor a real estate process with heavy environmental implications, but an implicit war against ethnic and religious communities. The consequence is inequality by design.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Prof. Dr. Johannes Widodo and Prof. Dr. Yunn Chii Wong who introduced me to Malacca and its people. Thanks to the National University Singapore (NUS) for its hospitality at the Tun Tan Cheng Lock Center for Asian Architectural and Urban Heritage in Malacca. Many thanks to Martin Theseira and the Portuguese community for telling their stories and helping me discover reality beyond appearances. Thanks to my students—Ashley, Ran, Yitong, Zuhui and Amanda—for their dedication to the design studio. Thanks to the generous photographers of the land of sand: Pek Foong, Muna Noor and Mohd Azrin Roselan. Many thanks also to the anonymous reviewers of this article for their precious comments and insights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Laura Cipriani

Laura Cipriani is Tenure Track Assistant Professor in the Department of Urbanism, Section of Landscape Architecture at TU Delft. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 The main goal of the course was to plan the city of Malacca through rethinking its open spaces. The design process involved various scales of work. The landscape planning involved the local population and informed stakeholders in participatory design (Steinitz Citation1990).

References

- Airoldi, L., M. Abbiati, M. W. Beck, S. J. Hawkins, P. R. Jonsson, D. Martin, P. S. Moschella, A. Sundeloff, R. C. Thompson, and P. Åberg. 2005. “An Ecological Perspective on the Deployment and Design of Low-Crested and Other Hard Coastal Defence Structures .” Coastal Engineering 52 (10): 1073–1087.

- Airoldi, L., S. D. Connell, and M. W. Beck. 2009. “Marine Hard Bottom Communities: Patterns, Dynamics, Diversity, and Change .” Ecological Studies 206: 269–280.

- Airoldi, L., X. Turon, S. Perkol-Finkel, and M. Rius. 2015. “Corridors for Aliens But Not for Natives: Effects of Marine Urban Sprawl at a Regional Scale .” Diversity and Distributions 21: 755–768.

- Beech, H. 2018. “We Cannot Afford This: Malaysia Pushes Back Against China’s Vision.” The New York Times, 20 August. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/20/world/asia/china-malaysia.html.

- Beiser, V. 2018. The World in a Grain: The Story of Sand and How It Transformed Civilization. New York: Riverhead Books .

- Bernstein, R. 2009. The East, the West, and Sex: A History of Erotic Encounters. New York: Alfred A. Knopf .

- Bo, M. W., and V. Choa. 2004. Reclamation and Ground Improvement. Singapore: Thomson Learning .

- Brenner, N., P. Marcuse, and M. Mayer. 2009. “Cities for People, Not for Profit .” City 13 (2–3): 176–184.

- Brenner, N., and C. Schmid. 2012. “Planetary Urbanization.” In Urban Constellations, edited by M. Gandy, 10–13. Berlin: Jovis .

- Brenner, N., and C. Schmid. 2015. “Towards a New Epistemology of the Urban? ” City 19 (2–3): 151–182.

- Burt, J., D. Feary, P. Usseglio, A. Bauman, and P. F. Sale. 2010. “The Influence of Wave Exposure on Coral Community Development on Man-Made Breakwater Reefs, With a Comparison to a Natural Reef .” Bulletin of Marine Science 86 (4): 839–859.

- Chang, T. C., and S. Huang. 2011. “Reclaiming the City: Waterfront Development in Singapore .” Urban Studies 48 (10): 2085–2100.

- Chee, S. Y., A. G. Othman, Y. K. Sim, A. N. M. Adam, and L. B. Firth. 2017. “Land Reclamation and Artificial Islands: Walking the Tightrope Between Development and Conservation .” Global Ecology and Conservation 12: 80–95.

- Choplin, A. 2020. “Cementing Africa: Cement Flows and City-Making Along the West African Corridor (Accra, Lomè, Cotonou, Lagos) .” Urban Studies 57 (9): 1977–1993.

- Cipriani, L. 2018. Landscapes of Hope. Reclaiming Malacca. Singapore: NUS .

- Cipriani, L. 2021. “The Death and Life of a Tropical Landscape: Envisaging a New Melaka, Malaysia.” In Tropical Constrained Environments and Sustainable Adaptations. Businesses and Communities, edited by S. Azzali and K. Thirumaran. Singapore: Springer Singapore .

- Dawson, K. 2021. “Geologising Urban Political Ecology (UPE): The Urbanisation of Sand in Accra, Ghana .” Antipode 53 (4): 995–1017.

- De Certeau, M. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press .

- Delestrac, D. 2013. Sand Wars. ARTE France .

- Embong, A. R., H. D. Evers, and R. Ramli. 2017. “One Belt One Road (OBOR) and Malaysia: A Longterm Geopolitical Perspective .” Working paper 5. Institute of Malaysian & International Studies Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, 1–29.

- Eng, C. K. 1983. “The Eurasian of Melaka.” In Melaka: The Transformation of a Malay Capital c.1400–1980 – Volume II, edited by K. S. Sandhu and P. Wheatley, 264–281. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press .

- Esri Community Maps Contributors, Esri, HERE, METI/NASA, USGS. 2016. “World Imagery.” 20 December. https://livingatlas.arcgis.com/wayback/?active=18966&ext=102.25423,2.16627,102.27174,2.18074.

- Firth, L. B., A. M. Knights, D. Bridger, A. J. Evans, N. Mieszkowska, P. J. Moore, N. E. O’Connor, E. V. Sheehan, R. C. Thompson, and S. J. Hawkins. 2016. “Ocean Sprawl: Challenges and Opportunities for Biodiversity Management in a Changing World .” Oceanography and Marine Biology 54: 193–269.

- Furnivall, J. S. 1948. Colonial Policy and Practice: A Comparative Study of Burma and Netherlands India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press .

- Gastrow, C. 2017. “Cement Citizens: Housing, Demolition and Political Belonging in Luanda, Angola .” Citizenship Studies 21 (2): 224–239.

- Greenwood, D. J., and M. Levin. 1998. Introduction to Action Research: Social Research for Social Change. Thousand Oaks: Sage .

- Harvey, D. 2003. The New Imperialism. Oxford: Oxford University Press .

- Harvey, D. 2008. “The Right to the City .” New Left Review 53 (Sept-Oct): 23–40.

- Harvey, D. 2012. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. London: Verso .

- Hirschman, C. 1986. “The Making of Race in Colonial Malaya: Political Economy and Racial Ideology .” Sociological Forum 1 (2): 330–361.

- Körling, G. 2020. “Bricks, Documents and Pipes: Material Politics and Urban Development in Niamey, Niger .” City & Society 32 (1): 23–46.

- Laws of Malaysia. 2014. Act 172. Town and Country Planning Act 1976.

- Lefebvre, H. 1970. La Révolution urbaine. Paris: Editions Gallimard .

- Lefebvre, H., E. Kofman, and E. Lebas. 1996. Writings on Cities. Cambridge, MA: Blackwell Publishers .

- Marcuse, P. 2009. “From Critical Urban Theory to the Right to the City .” City 13 (2–3): 185–197.

- Moorthy, R. 2021. “Hybridity and Ethnic Invisibility of the “Chitty” Heritage Community of Melaka .” Heritage 4 (2): 554–566.

- Moreno-Tabarez, U. 2020. “Towards Afro-Indigenous Ecopolitics .” City 24 (1-2): 22–34.

- Pedruzzi, P. 2014. “Sand, Rarer Than One Thinks .” Environmental Development 11: 208–218.

- Penang Tolak Tambak, Kesatuan Nelayan Tradisional Indonesia (KNTI), Persatuaan Aktivis Sahabat Alam (KUASA), Save Portuguese Community Action Committee (SPCAC), Kumpulan Indah Tanjung Aru (KITA), and Koalisi Selamatkan Teluk Jakarta. 2019. “Stop Stealing Our Seas, Joint Statement by Malaysia-Indonesia Groups Against Reclamation.” https://www.change.org/p/prime-minister-of-malaysia-save-penang-reject-the-3-islands-reclamation/u/25389959.

- Pilò, F. 2020. “Material Politics: Utility Documents, Claims-Making and Construction of the ‘Deserving Citizen’ in Rio de Janeiro .” City & Society 32 (1): 69–90.

- Pilò, F., and R. Jaffe. 2020. “Introduction: The Political Materiality of Cities .” City & Society 32 (1): 8–22.

- Purcell, M. 2014. “Possible Worlds: Henri Lefebvre and the Right to the City .” Journal of Urban Affairs 36 (1): 141–154.

- Sidhu, M. 1983. “An Introduction to Ethnic Segregation in Melaka Town.” In Melaka: The Transformation of a Malay Capital c.1400–1980 – Volume II, edited by K. S. Sandhu and P. Wheatley, 30–46. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press .

- Steinitz, C. 1990. “A Framework for Theory Applicable to the Education of Landscape Architects (and Other Environmental Design Professionals) .” Landscape Journal 9 (2): 136–143.

- Twincities. 2017. “At a Glance.” http://msdesk.mbmb.gov.my/twincities/glance.cfm.

- UNEP. 2014. Sand, Rarer Than One Thinks. Sioux Falls, SD: United Nations Environment Programme .

- UNEP. 2019. Sand and Sustainability: Finding New Solutions for Environmental Governance of Global Sand Resources. Geneva: GRID-Geneva, United Nations Environment Programme .

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. 2015. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2014 Revision, (ST/ESA/SER.A/366). New York: United Nations .

- Wade, S. 2020. “Inside the Belt and Road’s Premier White Elephant: Melaka Gateway.” Forbes, 31 January. https://www.forbes.com/sites/wadeshepard/2020/01/31/inside-the-belt-and-roads-premier-white-elephant-melaka-gateway/?sh=7bbf9f7c266e.

- Wallace, A. R. 1869. The Malay Arcipelago. The Land of the Orang-Utan and the Bird of Paradise. London: MacMillan and Co .

- Welsh, B. 2020. “Malaysia’s Political Polarization: Race, Religion, and Reform.” In Political Polarization in South and Southeast Asia: Old Divisions, New Dangers, edited by T. Carothers and A. O’Donohue, 41–52. Washington, DC: Carnegie Endowement for International Peace .

- Widodo, J. 2004. The Boat and the City: Chinese Diaspora and the Architecture of Southeast Asian Coastal Cities. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Academic .

- Widodo, J. 2011. “Melaka. A Cosmopolitan City in Southeast Asia .” Review of Culture 40: 33–49.

- Wong, Y. C. 2011. Historic Malacca Postcards. Singapore: CASA and NUS .

- Yusup, M., A. F. Arshad, Y. A. Abdullah, and N. S. Ishak. 2016. “Coastal Land Reclamation: Implication Towards Development Control System in West Malaysia .” Environment-Behaviour Proceedings Journal 1 (1): 354–361.