Abstract

This article discusses migration to rural areas in Africa and its relation to the emergence and development of new towns and urbanism. New conditions of mobility and the establishment and development of newly urban and proto-urban areas call for a reassessment of mobility and settlement dynamics. Changing contexts of urban-rural relations with important societal implications, new transformations and reconfigurations of urban forms call for analyses beyond rural exoduses, unequal territorial development, or the primacy of major cities. In Angola, urban construction, namely of the new ‘centralidades’—emergent new cities made of blocks of buildings and respective infrastructure in vacant areas in the countryside—attempts the creation of cities before the agglomeration of population or the undertakings to attract migration, other than just housing. This intentional urbanisation is thus characterised by hesitant settlement, which this article analyses using empirical material collected in a variety of Angolan centralidades.

Introduction

This article discusses migration and mobility towards as-yet uninhabited rural and disconnected areas and its relation to the emergence and growth of new towns and new urban arrangements in sub-Saharan Africa, using the case of the ‘centralidades’ in Angola as an example. These new ‘cities’ built from scratch, with apartment blocks, organised streets and planned infrastructure and services’ facilities, involve in-migration of new residents, the majority of them moving from relatively nearby urban and peri-urban areas. This migration within the country contributes to creating new urban forms beyond the so far predominant type of urbanisation based on rural-urban exoduses and other new emergent urban configurations such as those of boomtowns linked to, for example, mineral exploration.

The colonial political and administrative spatial management has largely determined urbanism in Africa. Typical urban growth in the continent is generally geared by spontaneous migration to towns and cities and to their peripheries (Agergaard, Fold, and Gough Citation2009; Ferguson Citation1999; Geyer and Geyer Citation2015; Parnell and Pieterse Citation2014; Potts Citation2013a; Robinson Citation2016). As a consequence, most of the urban research focuses on forms of urbanisation based on rural-urban migration to already established or growing cities additionally placing the focus of urban analysis on rural exoduses, decentralisation and imbalances between urban and rural areas. Urbanisation in Angola is also historically linked to migration into already built towns and cities (Cain Citation2016; Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2012), especially throughout a three decades’ civil war (1975–2002) that lead to the urban explosion of the 1990s and 2000s. However, as in other parts of the world, in Angola other types of urban configurations and urban formation have become central in urban development projects, leading to new intentional, planned urban growth in the sense that it does not result from this typical spontaneous migration.

The characteristics of these new population movements to not yet urban locations are not so well known among scholars and policy stakeholders alike. Limited knowledge about urban-to-rural migration is due, on one hand, to fast-changing urban and internal migratory dynamics in the continent in general but on the other hand to the focus traditionally set on demographics and local development issues involved in these processes. New migratory dynamics are, however, developing throughout the continent, producing new urban configurations and new urban loci. These processes of rural change and city-making involve the mentioned promoted and intentional urban-to-rural migration and the transformation of the rural areas (Agergaard, D’haen, and Birch-Thomsen Citation2013; Berdegué, Rosada, and Bebbington Citation2014; Halfacree Citation2012; Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2020b). This transformation is fostered both by private investments and by state projects, such as the centralidades in Angola. Newly urbanised or proto-urban locations in rural vacant areas—or in few cases close to small towns or to villages—emerge especially associated with major endeavours such as industries or transportation infrastructure. They are often a result of economic changes introduced in rural economies (Makindara et al. Citation2013), such as agribusinesses, tourism, mining/extractives-related ventures, real estate, or with, for instance, new border or transport hubs like port towns (Bryceson and Mackinnon Citation2012; Nchito Citation2012; Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2010, Citation2012, Citation2020b; Jedwab and Moradi Citation2016; Dobler Citation2009; Buursink Citation2001; Nugent Citation2012).

In Angola, the state builds the centralidades in areas disconnected from the main cities to respond to the housing needs of a growing population, the majority living in precarious neighbourhoods, and to territorial management strategies that aim at deconcentration. The Bailundo centralidade (see ) is one example of such implantation in vacant areas, distant from other urban centres. Migration and settlement here are characterised by hesitation, by continued alternations of residence between the established cities from where the majority of the residents of the centralidades come from and the cities to be. The dynamics of non-definitive settlement associated with the centralidades show that many emergent patterns exist and that urbanisation is not always about unidirectional migration and fixation.

The literature about migration in Africa is mostly concerned with changing local dynamics related to international migration (De Bruijn, Van Dijk, and Foeken Citation2001; Castles Citation2002; Maphosa Citation2007; De Haas Citation2010) and less about those of internal migration (Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2020a). The latter is, however, an important feature to understand rural transformation and urbanisation as the proportion of urban settlements of all sizes tends to increase mostly due to new forms and possibilities for mobility. Migration and settlement change rural locations, transforming them at different rhythms into urban places (Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2012; Bryceson Citation2011). They ‘become culturally more similar to large urban agglomerations’, (Berdegué, Rosada, and Bebbington Citation2014, 463), attracting urban migration (Nhantumbo and Ferreira Citation2012) and ‘return’ migration (Falkingham, Chepngeno-Langat, and Evandrou Citation2012), creating a variety of conditions for permanency in such new ‘frontier settlements’ (Agergaard, Fold, and Gough Citation2009). This is, therefore, an important subject for the social sciences. This article contributes to the debates on ‘intentional’ city-building, as seen throughout the world (Graham Citation2000; Hannan and Sutherland Citation2015; Murray Citation2015; De Boeck Citation2019; van Noorloos Citation2021), looking specifically at the strategies devised by the residents in such contexts of countryside transformations. It not only points out the relevance of the topic of migration to rural areas, where new urban settlement is promoted, it shows that urbanisation and migration do not necessarily have a direct causal relation but can assume multiple and varied configurations. While the centralidades are not homogeneous, the dynamics of settlement and the way residents make the urban life there, further contribute to the emergence of diversified urban formations. The article then contributes to the discussion on the inter-correlations of migration and urbanisation in contemporary situations by emphasising the role of residents in the making of urban living, which goes beyond mere construction, such as in the centralidades. The construction of centralidades alone does not necessarily create new cities as residents are required to deal with infrastructural and economic shortcomings there, which continue to be covered by the facilities readily provided by the main established cities, leading to hesitant fixations.

The article starts by providing a general background of the research landscape of urban-rural migration and new in-country mobilities, focusing on Africa and on the main issues involved in these processes. After giving a broad perspective of the recent dynamics of Angolan urbanisation, the discussion focusses on the case of the centralidades, which provides an example for the analysis of how the construction of cities does not necessarily foster migration itself or urbanism. The main argument being developed is that while ‘spontaneous’ urbanisation in Angola results in urban consolidation in a variety of locations, ‘intentional’ new urbanism foreseen by large-scale ventures is dependent on a combination of factors beyond simple housing construction.

Materials and methods

This article is based on the ample discussions about migration and mobility in Africa and uses available literature on migration to rural areas combined with empirical research. It brings to the discussion some particular features and trends and takes the case of Angola to illustrate changing urban-rural dynamics and emergent new urbanisation. It uses demographic data and economic assessments from available data sources and recent studies to indicate the types and trends of migration and urbanisation. The qualitative data is drawn from research in urban contexts in Angola conducted since the early 2000s and in emergent towns from 2015 including insights from direct observation and the collection of accounts and interviews with a series of urban actors and stakeholders. Several visits and more than 50 semi-structured interviews conducted in the centralidades throughout the countryFootnote1 with different types of actors—residents, administrators, planers, traditional authorities, those involved in sales of houses, businesspeople of the formal and informal economies from shop owners and workers to peddlers, domestic workers, or other types of service providers like school teachers and staff, health workers, among others—were accompanied by direct ethnographic observation at different moments for different research projects. The figures selected for this article, drawn from my extensive photographic collection, aim at providing a visual dimension of the ongoing rural transformation under analysis. The review, compilation and triangulation of information—available from documents, publicly available data, and publications about the centralidades—that normally focus on just one or two case studies—were actively mobilised for a comprehensive analysis.

Context: urbanising Africa and migration to rural areas

While there are specificities of each country and of their urban-rural situations and relations, some general aspects can be highlighted in the African context: first, the continued high internal mobility of the population, across the continent and internationally (Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2020a); second, the tendency of increasing urbanisation and urban concentration in new areas (Graham Citation2000; Hannan and Sutherland Citation2015; Murray Citation2015; van Noorloos Citation2021).

Migration and mobility refer to a broad scope of forced and voluntary displacements, including temporary and permanent migrations, rural exoduses and returns to the countryside, not necessarily implying fixation in a certain destination (De Bruijn, Van Dijk, and Foeken Citation2001). The notions of mobility and movement that better translate the features of settlement include ‘circular migration’—a non-unilineal perspective of movement activated and ‘hibernated’ according to changing contexts, as proposed by James Ferguson (Citation1999) and further developed by Deborah Potts (Citation2010), or ‘dynamic heterolocalism’ (Halfacree Citation2012). Migration patterns are ‘far more complex than originally suggested in migration studies and vary greatly amongst different subpopulations’ (Geyer and Geyer Citation2015, 10). African intra-continental and in-country movements, seemingly ‘far exceed international movements’ (Potts Citation2013a, 8), interconnecting with international migrations, continental circulation, old and new corridors and their respective platforms (De Bruijn, Van Dijk, and Foeken Citation2001; Castles Citation2002; De Haas Citation2010; Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2020a).

Urbanisation and urban growth are intrinsically linked to the dynamics of migration and movement. Global urban history has been characterised by migration from rural areas combined with natural growth of populations and rural-urban migration continues to characterise the African continent (Fox, Bloch, and Monroy Citation2017). The impressive growth of bigger cities is both a global and African trend too, despite the important signs of rural transformation and new types of migratory trends (Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2020b). Early research about urban-to-rural migration has been focused on the earliest urbanised Western countries (Berry Citation1976, Citation1980) but today, also in developing contexts such as the African continent, ‘forces of economic and social change’ are often charged with restructuring rural areas and transforming them into urban ones (Rigg Citation2016). In the Global North in general, urban-to-rural migration usually appears as an idealised return to the countryside or the ‘gentrification’ of the ‘Global Rural’ (Nelson and Nelson Citation2010), an ‘idyllic’ life and a matter of lifestyle choices (Bijker and Haartsen Citation2012; Stockdale and Catney Citation2014). But urban-to rural migration research became ‘somewhat academically stagnant’ in general (Halfacree Citation2008, 482). A renewed perspective on urban-rural mobility and urban transformation will have to take into account the many features of the transforming relationships between the rural and the urban, new urbanisation in ‘frontier’ regions (Agergaard, Fold, and Gough Citation2009) and new migratory tendencies (Potts Citation2009, Citation2013a; Halfacree Citation2012; Dupuy, Mayer, and Morissette Citation2000; Démurger and Xu Citation2011; Veneri and Ruiz Citation2013).

Worldwide urban growth is a well-recognised tendency and part of Africa’s ‘urban revolution’ (Parnell and Pieterse Citation2014) with fast urbanising populations in the Global South, although it still remains higher in the Global North (Parnell and Robinson Citation2012). Africa’s urban growth and urbanisation, particularly recently, has progressively caught the attention of academics and practitioners, namely in what concerns ‘Dubai style’ large-scale urban projects (Graham Citation2000; Hannan and Sutherland Citation2015; Murray Citation2015). There is today an increasing number of new global, international and national ventures changing many parts of the continent, placing it within major global economic, political and demographic flows in new ways. Master-planned cities (van Noorloos Citation2021), associated with (new) types of national and global actors and types of investment open the urban analysis in Africa to new research terrains (Almqvist Citation2022; Côté-Roy and Moser Citation2022).

Urban-to-rural migration: economies and livelihoods

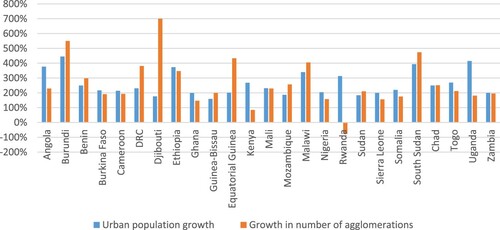

Economic reasons characterise migrations and mobility worldwide (Crankshaw and Borel-Saladin Citation2018), while not necessarily conforming to simplistic ‘push-pull’, neoclassical or other ‘equilibrium’ models. This includes new economic opportunities being created in rural areas or in smaller urban centres (Reynolds and Antrobus Citation2012) that become central for the economic strategies of urban-to-rural migrants (and rural-rural migrants alike). Shifts occurring in the labour market, government-driven decentralisation and expansion of services, housing and infrastructure (Agergaard, D’haen, and Birch-Thomsen Citation2013) and, most crucially, new public and private ventures such as the exploration of natural resources are central to understanding urban-to-rural migration. Throughout the continent, this type of migration was particularly marked within processes of economic decline observed for instance in the late 1970s and with changes in macro-economic policies such as the Structural Adjustment programmes (Beauchemin Citation2011). The share of people who migrate from urban to rural areas is usually limited but an analysis of the evolution of urban agglomerations—urban locations with more than 10,000 inhabitants—in sub-Saharan Africa in the last 15 years shows that the number has grown fast ().

Figure 2: Growth of agglomerations and population in selected fast urbanising sub-Saharan countries, 2000–15 (Source: adapted by the author from Africapolis (http://www.africapolis.org/)).

In some of the countries in , industries based in rural areas are the likely cause of attraction of urban populations. The extractives sector, both through in-land explorations and off-shore explorations linked to onshore urban platforms, has been a catalyst for agglomerations throughout Africa (Bryceson and Mackinnon Citation2012; Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2012; Agergaard, D’haen, and Birch-Thomsen Citation2013; Kirshner and Power Citation2015). Industrial agriculture, while mobilising a more modest amount of a qualified urban workforce, has also contributed to urban-to-rural migrations in some cases. Studies in African contexts have so far only identified a few cases of population growth directly related to tourism (Briedenhann and Wickens Citation2004) or, indirectly, to private investments in second homes for urban populations (Hoogendoorn, Visser, and Marais Citation2009).

Migration to rural areas in Africa may, however, combine with additional ‘repelling’ factors: urban problems related to overcrowding and congestion of different types, precarious living, crime and insecurity, environmental risks and poverty. Reasons for leaving cities range ‘from the inability to secure jobs, transfer from their place of work, retirement’ to high cost of living in the urban centres (Adewale Citation2005, 14). Livelihood vulnerability increasingly found in African cities fosters a higher propensity for mobility and although cities are sought after because of the better opportunities they offer, urban economies are not always favourable for urban dwellers (Bryceson and Potts Citation2006).

The dominant preoccupations with rural exoduses and territorial imbalances

Discussions and analysis of urban-rural migration and settlement have been focussed on the trends of rapid urbanisation of capital cities and on the differentials between the stock of urban and rural populations at national levels. This relegates the ‘apparent anomaly of urban-to-rural migration’ in Africa (Ferguson Citation1999, 82) virtually to invisibility. Moreover, these trends have been sustained by prevailing notions of development based on decentralisation and on an idealised ‘balanced’ territorial development.

The concentration of the urban analysis in capital cities and well-established cities in Africa may be due to the fact that Africa in general has for long been kept away from investigations about urban dynamics (Pieterse Citation2008), despite the diversity in the continent and the multiple processes of urbanisation (Robinson Citation2016). Consequently, in cases where the urban-to-rural migration is addressed, the main concerns end up being the demographics, both in Africa (Costello Citation2007, Citation2009; Grant Citation2015; Beauchemin Citation2011; Geyer and Geyer Citation2015; Potts Citation1995, Citation2009; Bryceson and Potts Citation2006) and elsewhere (Champion Citation1989; Ma Citation2001; Costello Citation2009; Bijker and Haartsen Citation2012; Halfacree Citation2012). While important to contextualise the main trends, the demographic approach is limited in many aspects. On one hand, due to practical constraints, the data generally available in Africa does not help to build full and definitive conclusions on the demographics of countries. Second, it is also difficult to capture mobility from censuses usually carried out in intervals of ten years, which often do not capture the intense internal mobility and the emphasised mixture of permanent and temporary circulations and settlement.

Another area dominating the study of internal migration and urban settlement and reconfigurations is the concern at policy level with decentralisation and local development. This is in line with the discussions of the 1970s to the 1990s that were split between the optimistic and the pessimist visions of ‘urban’ development of African rural areas (Baker and Claeson Citation1990; Funnell Citation1976; Mathur Citation1984). This type of research aimed ‘to address the issue as to how small towns can, and do, play a significant and positive role in promoting rural development and prosperity’ (Baker Citation1990, 7). The positive prospects of migration to and urbanisation of the countryside continue to perceive emergent, small, decentralised rural towns and urbanisation as drivers of development as a whole and as catalysts for rural development in particular in search for intermediate urban structures that can better support urban-rural relations within their complementarities (Satterthwaite Citation2016; Larsen and Birch-Thomsen Citation2015; Knudsen and Agergaard Citation2015; MacGranahan et al. Citation2009). Decentralisation explicitly or implicitly permeates this perspective of development and of the role of smaller cities as connectors between the rural and larger cities (Roberts Citation2014).

Neither the concerns about local development, balanced territorial distribution of urban populations and resources nor the demographics of urbanisation are less important when studying urban-rural mobility and urbanisation. However, these aspects need to be enhanced and integrated with more research about changing forms and loci of mobility with transforming urban realities, and particularly the residential projects in the countryside.

Angola and urbanisation: new emergent towns and in-migration

Urbanisation in Angola

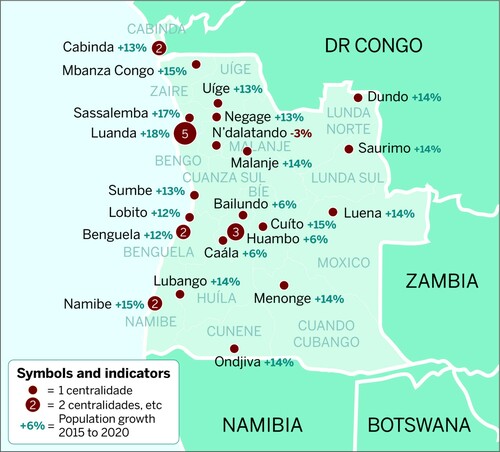

Research about urban Angola has been, like elsewhere in Africa, concentrated in the impressive growth and primacy of the capital Luanda (Cain Citation2018; Cardoso Citation2015; Croese Citation2017; Croese and Pitcher Citation2019; Gastrow Citation2020; Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2018, Citation2022) and very rarely looked at the growth of economic poles, related for instance to mining or gas explorations, to border towns, or to how intra-country circulation shaped the formation of new urban centres, especially after independence. Moreover, as urbanisation dynamics in Angola have been characterised by migration from rural areas to established cities, particularly during the civil war, less attention has been paid to new or to smaller centres. The colonial construction of the urban network and the control of the flows of population within the country through labour and housing, namely through the rural projects then called colonatos (Castelo Citation2016; Coghe Citation2017) was replaced by intensive post-independence forced migrations to urban centres due to the civil war. Most of the country’s population moved to the capitals of the provinces where the government had control, to escape the war being played out in the countryside (Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2012). After that, rural exoduses continued, motivated by precarious economic and infrastructural conditions in the countryside. Within these contexts, population movement and settlement was responsible for the growth and configuration of urban centres (Croese Citation2012, Citation2017; Cain Citation2016, Citation2018; Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2010, Citation2012, Citation2020b). shows how fast cities like the capital Luanda and others have grown right after the end of the war and particularly in the last five years.

Figure 3: Selected fast growing agglomerations/municipalities in Angola (Source: INE population projections Citation2020 and author compilation).

While, as mentioned, the emergence and growth of rural new ‘urban agglomerations’ has not been substantive, the early 2000s inaugurated a new era for Angolan urban planning and management with the beginning of the construction of the centralidades, the new satellite cities built from scratch, normally detached by 10–20 km on average from the regional cities. This also marked a reversal of the migration/urban growth nexus, with cities being built before settlement. For example, while located only seven kilometres from Caála, a small 130,000 inhabitants village, the Caála centralidade () is nearly 30 km away from the province capital Huambo.

As will be further detailed, this has led to intense commuting and/or hesitant definitive settlement as livelihoods of the new residents depend on stabilised functional urban economies. Other examples throughout the country also show how the implantation of this type of construction takes place in vacant rural areas, formerly utilised for agricultural activities and cattle raising, connected to small rural villages (at times compelling their resettlement). They are not easily accessible or interconnected peripheries of existing cities and therefore demand negotiating livelihoods and mobility in the making of urban lives in these new cities.

Urbanisation through the construction of centralidades

also shows how the construction of centralidades did not necessarily follow criteria of population quantities or growth, although the statistical projections may have anticipated urban growth motivated by these projects. The centralidades were roughly built one in each province, normally relatively near the capital of that province (marked bold in ), thereof being also called ‘satellite cities’ but not sufficiently close or served with the transportation infrastructure to allow easy commuting. The majority are located in the remote outskirts of the reference cities, within expansion lines defined by local urban planning. is a compilation of information about the Angolan centralidades. As most of them were built near a capital of province, the economies in which its residents are engaged or potentially engaged are in the majority of cases related to or dependent on the province capital city, despite the distance.

Table 1: Angolan centralidades, a compilation with information about demand

The new ‘centralities’ in Angola appear through the National Urbanism and Housing Programme, in execution since 2009. It is the main strategic instrument of the Housing Promotion Policy, based on the Housing Promotion Law (Law 3 / 07, of September 3, 2007). Only some cities have centralidades, mostly province capitals, but in general most cities in Angola have other urban projects, such as ‘fogos habitacionais’ composed of single-family houses built by the state or within self-construction projects. These are also often implanted in rural areas away from the urban centres. The national Programme of 2008 planned for the construction of One Million Houses throughout the country (Cain Citation2016, Citation2018; Croese Citation2012, Citation2017). Much of the analysis of these projects has focused on the role of external financial actors or on oil motivated Chinese financing (Cardoso Citation2015; Buire Citation2017), or on state politics as main motivations for their execution (Croese and Pitcher Citation2019), but rarely on the dynamics of mobility and settlement. Internationally, other approaches to urbanisation through macro-projects have also concentrated on the deep political logics involved in urban projects in rural disconnected areas (Almqvist Citation2022; Moser, Côté-Roy, and Korah Citation2021; Côté-Roy and Moser Citation2022).

Overall, Luanda is one of the Angolan cities that saw more housing and urban projects and programmes being planned and implemented since the beginning of the 2000s. Luanda has grown in population and area very rapidly, with more than seven million inhabitants today, which pushed for both new construction to cover the needs of the growing population but also requalification and/or reconstruction of areas that grew fast and unorderly during the civil war, resulting in dwelling precarity. summarises the main urban programmes of the capital Luanda between 2009 and 2014.

Table 2: Housing programme in Luanda 2009–14

As for the centralidades of the capital city, they were planned to be located away the main city centre, to function as satellite cities and contribute to the de-concentration of the population and activities gravitating around the city centre, a situation that characterised Angolan cities for many years, particularly during the civil war. shows the dimension of the new satellite cities as well as the logic of implantation, in all cases within more than 30 km away from the city centre, in what were then, at the time of planning, rural vacant areas.

Table 3: Compared analysis of the five centralidades of Luanda city

There were several construction companies involved in the projects since their inception: KORA Angola, IMOGESTIN SA (both private Angolan companies), CTCE (China Tiesiju Construction Engineering), CITIC (China International Trust and Investment Corporation), CIF (China International Fund), China Guangxi/Pan-China, or Confrasilvas SA (Portuguese multinational company). These are still the most active ones today. They are involved in the centralidades’ projects throughout the provinces, directly following state guidance in this respect.

Location and management of the centralities and demand

The centralidades were planned to be implanted in vacant rural areas and built to host mostly the residents from the large city centres, particularly those in precarious peripheral areas and/or dwellings. When the National Housing Programme of 2008 was introduced, the state had already established land reserves for its execution in the Luanda capital metropolitan region, in rural areas (Cain Citation2016). This anticipation was motivated by the need to secure land and prevent occupations for speculation (Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2022).

Location in the rural outskirts was seen from the beginning as a challenge by residents and potential candidates for the housing projects. Most people depended on the urban activities they had already established in their cities of origin. One among the many interviews conducted in Luanda clearly pointed out this challenge: ‘First of all, I will lose my business [market vendor] because the clients are here. If I try to keep this place in the market, how will I come to the city if there is no transportation there?’ (A. M., market vendor, Luanda November 2018). Both in Luanda and in some of the other centralidades throughout the country, the majority of the residents remained dependent on the main city economies, infrastructure and services, especially in the first stages of occupation of the new cities. Not being able to permanently fixate in the new cities and at the same time being far from the main cities, means the available options are roughly to stay, to go back or hesitantly find ways of negotiating between residencies. Settlement in most of the centralidades is consequently relatively weak so far, although it has been steadily growing. A study conducted in three centralidades of Luanda built first in the country (Quilamba, Sequele, Km 44), revealed that most of the residents have been living in the new city on average for two to three years (53%) and between one to two years (20%). The study also accounted for a return of residents back to the main city centre that had moved to the new cities in 2011, the majority mentioning the lack of infrastructure, services and economic opportunities (André Citation2019). Even in centralidades closer to urban centres like Lossambo (only 11 km away from province capital Huambo, ), residents would refer to the difficulties of finding businesses or other economic opportunities there. As M. L. indicated: ‘no one will come to the centralidade and those that live there have their businesses in Huambo’ (male, 26, Huambo, September 2014).

In addition to the challenges of location, all centralidades had/have issues regarding transparency and management of housing access, with some of the reported cases appearing more in the media than others. The managing institutions handling construction and sales of the apartments, houses and facilities have been replaced over the years, some of them due to alleged—and sometimes proved—irregularities in management. The centralidades were initially managed by the National Office for Reconstruction (Gabinete de Reconstrução Nacional) until 2010. In that year, the government decided to transfer the management to SONIP (Sonangol Imobiliária e Propriedades), a subsidiary of the national oil company Sonangol for real estate and assets, but this only lasted four years. Administration was then transferred to IMOGESTIN SA, a private real-estate company in 2014 and again in this case only lasted a few years, until 2019. Since then, the state reassumed the leadership of the urban programmes for the centralidades and currently the Housing Development Fund (Fundo de Fomento Habitacional) and the National Housing Institute (Instituto Nacional de Habitação) are in charge of construction, contracts and administration, including sales. These uncertainties and lack of transparency in management are also pointed out as a crucial factor explaining on one hand why people are not able to buy or access the houses and on the other, contributing to the apparent hesitant settlement.

Discussion: when cities are created before population settlement

The successive changes of management but also delays in delivering the centralidades—strongly impacted by the economic crisis since 2014 and by intricate socio-political dynamics—have caused some to be empty for significant periods. The fact that some were built in areas difficult to commute to or with no attractive economic possibilities has led to lower demand. The centralidades were also not all received by the buyers with the same interest throughout the country. In most of the cases, accounts collected through fieldwork and easily available in the media point to serious disruptions, delays and corruption in the attribution of houses, which held the interested buyers back from purchasing them. In other cases, the delays in construction and infrastructuring of the neighbourhoods were the reason that kept potential buyers from rushing to the new towns. For instance, the Capari centrality in Dande was uninhabited for over seven years due to delays and unclear selling procedures. In this new city, people from other parts of the region invaded the buildings and occupied the empty unsurveilled apartments until recently in 2020 a justice order was issued to expel the occupiers and resume the purchasing processes.

Completion of all works and infrastructure planned for the centralidades and their more efficient management was also key to determining the demand and settlement of residents. The infrastructure planned for the centralidades is quite comprehensive: water and electricity supply; transportation systems and accesses; sewage and water treatment; school facilities (pre-school, primary and other levels); waste collection; security/police stations; green areas; sidewalks; markets; shopping malls; community centres; hospitals/healthcare centres. This contrasts sharply with the precarious conditions found in most existing cities, both in the centre and in the peripheries, and is a strong feature of the demand for the centralidades (Udelsmann Rodrigues Citation2018). According to an interview with an urban planner in Luanda, the centralidades are projects about housing provision but also envisage work and leisure functions as they are detached from the main capitals/ cities, ‘not just dormitories’ (Luanda, I. D., March 2019). These infrastructural objectives are accompanied by sociocultural reconfigurations in Angolan society: ‘Luanda began to desire housing that was aesthetically formal […] for the realisation of the middle classes’ (Gastrow Citation2020, 509).

Two main aspects have a decisive impact on the dynamics of mobility and settlement, and urban formation and consolidation in the Angolan centralidades: the way they are managed and their location. shows the assessed levels of demand. While the majority of the centralidades are in high demand, delays and constraints caused by management have prevented people from moving in, like in the case of the Capari—although here, the houses were illegally occupied, as mentioned—or in the case of Baía Farta and Catumbela (Luhongo), where investigations into suspected fraud and irregularities are currently underway. In the two other centralidades with a low level of occupation, Centralidade do Dundo and Centralidade Horizonte do Andulo, issues related to the location are more salient, preventing adhesion and settlement, but delays in completion and management of the sales are also preventing people from moving in. The reference cities Dundo and Andulo are themselves small cities—although the latter has grown at a comparatively fast pace (see )—and consequently what accounts in the media and collected through interviews is that the centralidades here are not particularly crucial to cover the housing needs of the population. Moreover, the centralidade in Andulo is 120 km away from the province capital, Cuíto, where more attractive economic activities are located than in small Andulo. Dundo’s Mussungue centralidade is only 6 km away from the main city but the low population of the region and of the province and the concentration of the economic opportunities in the rural mining and agricultural sectors have not contributed to a significant urban growth in either of the urban economies. Location, the multiple transitions of management to different companies and the way the companies handled sales and access to the centralidades have led to different outcomes in terms of settlement and demand of the urban dwellers. Consequently, actual urban living has been intermittent and unstable in the centralidades that could not fully and rapidly attract dwellers. In Luanda's centralidades, like in Quilamba (see ) gradually some services like schools started to function and more people to live there more permanently.

The centralidades, being built in the rural areas, have followed an unparalleled pattern of urbanisation in Angola. Their construction preceded people’s interest to settle in a determined area and consequently the main complaints are that they are far away from the main city people relate to and do businesses/work in, with no transportation available to allow people to commute. As discussed, migration to rural areas, in this case urbanising ones, is essentially catalysed by the introduction of economic elements that can attract and fixate new dwellers. The existing chains of local (rural) production or new economic projects can catalyse in-migration if the important infrastructure is established, including roads, electricity, markets and agricultural processing facilities (Lazaro and Birch-Thomsen Citation2013) and the emergence of new settlements is in many cases due to a combination over time of infrastructure being introduced or improved (Agergaard, D’haen, and Birch-Thomsen Citation2013).

According to the literature, at the local level, the changes taking place regarding new urbanisms in Africa are varied and so are the new issues emerging. First and more evident are the changing urban forms, which need to be better understood. In some cases new spatial configurations include rural gated communities for instance, leading to new forms of ‘post-productive rurality’ (Spocter Citation2013) and territorial organisation. New socioeconomic processes happening in places increasingly qualified as cities, such as in long-lasting refugee camps (Jansen Citation2018; Landau Citation2008), or the dynamics of rural land grabbing, that impact urbanisation and infrastructure (Zoomers et al. Citation2017) also bring forward the emergence of new urban forms and formations that require more in-depth scrutiny. The centralidades are a new urban form in Angola that is evolving through processes of migration and settlement after urban construction, presenting new sites of urban investigation.

Conclusions

This analysis has shown that urban-to-rural migration and urbanisation of the rural does not necessarily take place according to planned housing ventures. Migration motivated by economic opportunities or by forced displacement is more likely to create cities than ready-built cities catalysing migration, if no other appeals beyond buildings exist. Within the context of rural transformation in Africa, understanding new migration and mobility needs to expand beyond the traditional rural-urban trend, namely to address urban-to-rural migration motivated by urban projects in the countryside. In Angola, as in many places, urban research has been developing around important issues such as planning, governance, poverty, employment or housing, but comparatively less has looked at internal migration and mobility as drivers of urbanisation happening outside of the main cities or at urban-rural mobilities beyond rural exoduses. Moreover, the focus on demographics and (un)balanced territorial development of urban and rural areas has also been predominant.

In Angola too, the focus of urban research has been predominantly the capital city Luanda and the rural exodus. Among policy stakeholders, the emphasis has been on decentralisation and on a balanced distribution of infrastructure throughout the country. Emergent towns and cities, already built and advanced in processes of consolidation have not captured the same interest. Key and intricate issues arising from new realities such as the centralidades are varied forms of hesitant settlement resulting from detachment—or difficult commuting—to the established urban centres they are connected to and their economies, incomplete infrastructuring, or management constraints. As a result, the mere construction of the centralidades does not make urbanism—people shape urban life—and the non-definitive settlement that characterises most of the living in the new centralidades is revealing a multitude of emergent residential and urban patterns. The analysis of some cases in Angola revealed that state-led intentional urbanisation of rural areas near established cities—but far enough for an easy daily commuting—often resulted in hesitant settlement. Associated to this detachment of the centralidades from the economically and infrastructurally better-off reference cities, most of the centralidades are slow to materialise and consolidate infrastructure and economic vibrancy. Additionally, the processes to access housing has been characterised by a generalised lack of transparency. Migration and settlement to the centralidades have produced different outcomes, depending on their situation: they are in some cases not fully occupied; in others those who initially settled there returned to the main cities. But the most common trend is non-permanent settlement, with intensive continued commuting taking place. Such outcomes bring to the fore the importance of location and management of the urbanisation processes for the fixation of residents and the expected urbanisation, as they are the key players in the making of urban life.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my special thanks of gratitude to my informants in Angola over the years. Also, I would like to thank the reviewers and editors, who provided most valuable comments and contributed to the improvement of the draft submitted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Cristina Udelsmann Rodrigues

Cristina Udelsmann Rodrigues is a researcher in interdisciplinary African Studies at the Nordic Africa Institute. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 To mention the ones where systematic fieldwork was conducted: Quilamba, Sequele, Zangos, Andulo, Capari, Km44, Caála.

References

- Adewale, J. Gmebiga. 2005. “Socio-Economic Factors Associated with Urban-Rural Migration in Nigeria: A Case Study of Oyo State, Nigeria .” Journal of Human Ecology 17 (1): 13–16.

- Agergaard, Jytte, Sarah Ann Lise D’haen, and Torben Birch-Thomsen. 2013. “Demographic Shifts and ‘Rural’ Urbanisation in Tanzania During the 2000s.” Paper Presented at the Session ‘Urbanisation as the New Frontier’, Abstract from Royal Geographical Society Annual International Conference, London. http://ign.ku.dk/english/employees/ign/?pure=files%2F134953880%2FRGS_IBG_2013_ja_tbt_final.pdf.

- Agergaard, Jytte, Niels Fold, and Katherine Gough. 2009. Rural-Urban Dynamics: Livelihoods, Mobility and Markets in African and Asian Frontiers. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis .

- Almqvist, A. 2022. “Rethinking Egypt’s ‘Failed’ Desert Cities: Autocracy, Urban Planning, and Class Politics in Sadat’s New Town Programme .” Mediterranean Politics, 1–22. doi:10.1080/13629395.2022.2043998.

- André, Bráulio Sebastião. 2019. “Políticas Habitacionais em Angola: o caso do programa novas centralidades em Luanda.” Unpublished master’s thesis, University Federal of Rio de Janeiro—UFRJ, Brazil.

- Baker, Jonathan. 1990. Small Town Africa: Studies in Rural-Urban Interaction. Uppsala: Scandinavian Institute of African Studies .

- Baker, Jonathan, and Claes-Fredrik Claeson. 1990. “Introduction.” In Small Town Africa: Studies in Rural-Urban Interaction, edited by Jonathan Baker, 7–33. Uppsala: Scandinavian Institute of African Studies .

- Beauchemin, Cris. 2011. “Rural-Urban Migration in West Africa: Toward a Reversal? Migration Trends and Economic Conjuncture in Burkina Faso and Côte D'Ivoire .” Population, Space and Place 17: 47–72.

- Berdegué, Julio A., Tomás Rosada, and Anthony J. Bebbington. 2014. “The Rural Transformation.” In International Development: Ideas, Experience, and Prospects, edited by Bruce Currie-Alder, Ravi Kanbur, David M. Malone, and Rohinton Medhora, 463–478. Oxford: Oxford University Press .

- Berry, Brian J. L. 1976. Urbanisation and Counter-Urbanisation. Los Angeles, CA: Sage .

- Berry, Brian J. L. 1980. “Urbanisation and Counterurbanisation in the United States .” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 451: 13–20.

- Bijker, Rixt Anke, and Tialda Haartsen. 2012. “More Than Counter-Urbanisation: Migration to Popular and Less-Popular Rural Areas in the Netherlands .” Population, Space and Place 18 (5): 643–657.

- Briedenhann, Jenny, and Eugenia Wickens. 2004. “Tourism Routes as a Tool for the Economic Development of Rural Areas—Vibrant Hope or Impossible Dream? ” Tourism Management 25 (1): 71–79.

- Bryceson, Deborah F. 2011. “Birth of a Market Town in Tanzania: Towards Narrative Studies of Urban Africa .” Journal of Eastern African Studies 5 (2): 274–293.

- Bryceson, Deborah F., and Daniel Mackinnon. 2012. “Eureka and Beyond: Mining’s Impact on African Urbanisation .” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 30: 513–537.

- Bryceson, Deborah F., and Deborah Potts. 2006. African Urban Economies: Viability, Vitality or Vitiation? London: Palgrave Macmillan .

- Buire, Chloé. 2017. “New City, New Citizens?: A Lefebvrian Exploration of State-Led Housing and Political Identities in Luanda, Angola .” Transformation: Critical Perspectives on Southern Africa 93: 13–40.

- Buursink, Jan. 2001. “The Binational Reality of Border-Crossing Cities .” GeoJournal 54 (1): 7–20.

- Cain, Allan. 2016. “Opportunities for Angola’s New Urbanism After the Collapse of the Oil Economy.” Development Workshop Angola, Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313902393_Opportunities_for_Angola's_New_Urbanism_after_the_Collapse_of_the_Oil_Economy.

- Cain, Allan. 2018. “Alternatives to African Commodity-Backed Urbanization: The Case of China in Angola .” Oxford Review of Economic Policy 33 (3): 478–495.

- Cardoso, Ricardo. 2015. “The Crude Urban Revolution: Land Markets, Planning Forms and the Making of a New Luanda.” PhD thesis, UC Berkeley. ProQuest ID: Cardoso_berkeley_0028E_15509.

- Castelo, Cláudia. 2016. “Reproducing Portuguese Villages in Africa: Agricultural Science, Ideology and Empire .” Journal of Southern African Studies 42 (2): 267–281.

- Castles, Stephen. 2002. “Migration and Community Formation Under Conditions of Globalization .” International Migration Review 36: 1143–1168.

- Champion, Anthony G., ed. 1989. Counterurbanisation: The Changing Pace and Nature of Population Deconcentration. London: E. Arnold .

- Coghe, Samuel. 2017. “Reordering Colonial Society: Model Villages and Social Planning in Rural Angola, 1920–45 .” Journal of Contemporary History 52 (1): 16–44.

- Costello, Lauren. 2007. “Going Bush: The Implications of Urban-Rural Migration .” Geographical Research 45 (1): 85–94.

- Costello, Lauren. 2009. “Urban-Rural Migration: Housing Availability and Affordability .” Australian Geographer 40 (2): 219–233.

- Côté-Roy, L., and S. Moser. 2022. “A Kingdom of New Cities: Morocco’s National Villes Nouvelles Strategy .” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 131: 27–38.

- Crankshaw, Owen, and Jacqueline Borel-Saladin. 2018. “Causes of Urbanisation and Counterurbanisation in Zambia: Natural Population Increase or Migration? ” Urban Studies 56 (10): 2005–2020.

- Croese, Sylvia. 2012. “One Million Houses? Chinese Engagement in Angola’s National Reconstruction.” In China and Angola: A Marriage of Convenience?, edited by Marcus Power and Ana C. Alves, 124–144. Cape Town: Pambazuka Press .

- Croese, Sylvia. 2017. “State-Led Housing Delivery as an Instrument of Developmental Patrimonialism: The Case of Post-War Angola .” African Affairs 116 (462): 80–100.

- Croese, Sylvia, and M. Anne Pitcher. 2019. “Ordering Power? The Politics of State-Led Housing Delivery Under Authoritarianism—the Case of Luanda, Angola .” Urban Studies 56 (2): 401–418.

- De Boeck, Filip. 2019. La ville du future: univers urbains du Congo à l'ère de la ville mondiale [Future City: Congo’s Urban Worlds in the Age of the Global City]. Montreuil: Editions de l'Oeil /MIAM .

- De Bruijn, Miriam, Rijk A. Van Dijk, and Dick Foeken. 2001. Mobile Africa: Changing Patterns of Movement in Africa and Beyond. London: Brill .

- De Haas, Hein. 2010. Migration Transitions: A Theoretical and Empirical Enquiry into the Developmental Drivers of International Migration. Working Paper 24. Oxford: International Migration Institute, University of Oxford .

- Démurger, Silvie, and Hui Xu. 2011. “Return Migrants: The Rise of New Entrepreneurs in Rural China .” World Development 39 (10): 1847–1861.

- Dobler, Gregor. 2009. “Oshikango: The Dynamics of Growth and Regulation in a Namibian Boom Town .” Journal of Southern African Studies 35 (1): 115–131.

- Dupuy, Richar, Francine Mayer, and Rene Morissette. 2000. “Rural Youth: Stayers, Leavers and Return Migrants .” Canadian Rural Partnership 152. http://publications.gc.ca/Collection/CS11-0019-152E.pdf.

- Falkingham, Jane, Gloria Chepngeno-Langat, and Maria Evandrou. 2012. “Outward Migration from Large Cities: Are Older Migrants in Nairobi ‘Returning’? ” Population, Space and Place 18 (3): 327–343.

- Ferguson, James. 1999. Expectations of Modernity: Myths and Meanings of Urban Life on the Zambian Copperbelt. Berkeley: University of California Press .

- Figueira, Moisés Bernardo. 2020. “Novas centralidades na área metropolitana de Luanda: a cidade de Sequele como estudo de caso.” Unpublished master’s thesis, Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas, University Nova of Lisboa, Portugal.

- Fox, Sean, Robin Bloch, and Jose Monroy. 2017. “Understanding the Dynamics of Nigeria’s Urban Transition: A Refutation of the ‘Stalled Urbanisation’ Hypothesis .” Urban Studies 55 (5): 947–964.

- Funnell, D. C. 1976. “The Role of Small Service Centers in Regional and Rural Development with Special Reference to Eastern Africa.” In Development Planning and Social Structure, edited by Alan Gilbert, 77–111. London: John Wiley .

- Gastrow, Claudia. 2020. “Housing Middle-Classness: Formality and the Making of Distinction in Luanda .” Africa: The Journal of the International African Institute 90 (3): 509–528.

- Geyer, Hermanus S., Sr., and Hermanus S. Geyer, Jr. 2015. “Disaggregated Population Migration Trends in South Africa Between 1996 and 2011: A Differential Urbanisation Approach .” Urban Forum 26 (1): 1–13.

- Government of Angola. 2014. Report of the state of the Territorial Planning 2014.

- Graham, Stephen. 2000. “Constructing Premium Network Spaces: Reflections on Infrastructure Networks and Contemporary Urban Development .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 24: 183–200.

- Grant, Richard. 2015. “Sustainable African Urban Futures: Stocktaking and Critical Reflection on Proposed Urban Projects .” American Behavioral Scientist 59 (3): 294–310.

- Halfacree, Keith. 2008. “To Revitalise Counterurbanisation Research? Recognising an International and Fuller Picture .” Population, Space and Place 14: 479–495.

- Halfacree, Keith. 2012. “Heterolocal Identities? Counter-Urbanisation, Second Homes, and Rural Consumption in the era of Mobilities .” Population, Space and Place 18 (2): 209–224.

- Hannan, Sylvia, and Catherine Sutherland. 2015. “Mega-Projects and Sustainability in Durban, South Africa: Convergent or Divergent Agendas? ” Habitat International 45 (3): 205–212.

- Hoogendoorn, Gijsbert, Gustav Visser, and Lochner Marais. 2009. “Changing Countrysides, Changing Villages: Second Homes in Rhodes, South Africa .” South African Geographical Journal 91 (2): 75–83.

- INE (Instituto Nacional de Estatística). 2020. Population Projections 2015–2050. Luanda: INE .

- Jansen, Bram J. 2018. Kakuma Refugee Camp: Humanitarian Urbanism in Kenya’s Accidental City. London: ZED Books .

- Jedwab, Remi, and Alexander Moradi. 2016. “The Permanent Effects of Transportation Revolutions in Poor Countries: Evidence from Africa .” Review of Economics and Statistics 98 (2): 268–284.

- Kirshner, Joshua, and Marcus Power. 2015. “Mining and Extractive Urbanism: Post Development in a Mozambican Boomtown .” Geoforum 61: 67–78.

- Knudsen, Michael H., and Jytte Agergaard. 2015. “Ghana’s Cocoa Frontier in Transition: The Role of Migration and Livelihood Diversification .” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 97: 325–342.

- Landau, Loren B. 2008. The Humanitarian Hangover: Displacement, aid, and Transformation in Western Tanzania. Johannesburg: Wits University Press .

- Larsen, Marianne N., and Torben Birch-Thomsen. 2015. “The Role of Credit Facilities and Investment Practices in Rural Tanzania: A Comparative Study of Igowole and Ilula Emerging Urban Centers .” Journal of Eastern African Studies 9: 55–73.

- Lazaro, Evelyn, and Torben Birch-Thomsen. 2013. “Rural-Urban Complementarities for the Reduction of Poverty (RUCROP): Identifying the Contribution of Savings and Credit Facilities.” Proceedings of the RUCROP Stakeholders’ Workshop, VETA Mikumi, Morogoro, Tanzania, August 20th 2012.

- Ma, Zhongdong. 2001. “Urban Labour-Force Experience as a Determinant of Rural Occupation Change: Evidence from Recent Urban–Rural Return Migration in China .” Environment and Planning A 33 (2): 237–255.

- MacGranahan, Gordon, Diana Mitlin, David Satterthwaite, Cecilia Tacoli, and Ivan Turok. 2009. Africa’s Urban Transition and the Role of Regional Collaboration. Human Settlements Working Paper Series, Theme: Urban Change—5. London: IIED . http://www.iied.org/pubs/display.php?o=10571IIED.

- Makindara, Jeromia, Marianne N. Larsen, Torben Birch-Thomsen, Freddy Kilima, Elizabeth Mshote, and Lukelo Msese. 2013. “Igowole Emerging Urban Centre.” Proceedings of the RUCROP Stakeholders’ Workshop, 23–32, Mikumi, Morogoro, Tanzania August 20, 2012.

- Maphosa, France. 2007. “Remittances and Development: The Impact of Migration to South Africa on Rural Livelihoods in Southern Zimbabwe .” Development Southern Africa 24 (1): 123–136.

- Mathur, Om Prakash, ed. 1984. The Role of Small Cities in Regional Development: Selected Case Studies from Developing Countries. Nagoya: United Nations Centre for Regional Development .

- Moser, S., L. Côté-Roy, and P. I. Korah. 2021. “The Uncharted Foreign Actors, Investments, and Urban Models in African New City Building .” Urban Geography, 1–8. doi:10.1080/02723638.2021.1916698.

- Murray, Martin. 2015. “City Doubles’: Re-Urbanism in Africa.” In Cities and Inequalities in a Global and Neoliberal World, edited by Faranak Miraftab, David Wilson, and Ken Salo, 92–109. London: Routledge .

- Nchito, Wilma. 2012. “Agriculture-Related Industry and Small Town Growth in Zambia: The Case of Mazabuka.” In Small Town Geographies in Africa: Experiences from South Africa and Elsewhere, edited by Ronnie Donaldson and Lochner Marais, 403–415. New York: Nova Science Publishers .

- Nelson, Lise, and Peter B Nelson. 2010. “The Global Rural: Gentrification and Linked Migration in the Rural USA .” Progress in Human Geography 35 (4): 441–459.

- Nhantumbo, E., and S. Ferreira. 2012. “Tourism Development and Community Response: The Case of Inhambane Coastal Zone, Mozambique.” In Small Town Geographies in Africa: Experiences from South Africa and Elsewhere, edited by R. Donaldson and L. Marais, 365–382. New York: Nova Science Publishers .

- Nugent, Paul. 2012. “Border Towns and Cities in Comparative Perspective.” In A Companion to Border Studies, edited by Thomas M. Wilson and Hastings Donnan, 557–572. Chichester: John Wiley .

- Parnell, Susan, and Edgar Pieterse, eds. 2014. Africa’s Urban Revolution. London: Zed Books .

- Parnell, Susan, and Jennifer Robinson. 2012. “(Re)Theorizing Cities from the Global South: Looking Beyond Neoliberalism .” Urban Geography 33 (4): 593–617.

- Pieterse, Edgar. 2008. City Futures: Confronting the Crisis of Urban Development. London: Zed Books .

- Potts, Deborah. 1995. “Shall We Go Home? Increasing Urban Poverty in African Cities and Migration Processes .” Geographical Journal 161 (3): 245.

- Potts, Deborah. 2009. “The Slowing of Sub-Saharan Africa’s Urbanisation: Evidence and Implications for Urban Livelihoods .” Environment & Urbanisation 21 (1): 253–259.

- Potts, Deborah. 2010. Circular Migration in Zimbabwe and Contemporary Sub-Saharan Africa. Woodbridge: James Currey .

- Potts, Deborah. 2013a. Rural-Urban and Urban-Rural Migration Flows as Indicators of Economic Opportunity in Sub-Saharan Africa: What Do the Data Tell Us? Working Paper 9. Cities Research Group, Geography Department, King’s College London .

- Reynolds, Kian, and Geoff Antrobus. 2012. “Identifying Economic Growth Drivers in Small Towns in South Africa.” In Small Town Geographies in Africa: Experiences from South Africa and Elsewhere, edited by Ronnie Donaldson and Lochner Marais, 35–43. New York: Nova Science Publishers .

- Rigg, Jonathan. 2016. “Rural–Urban Interactions, Agriculture and Wealth: A Southeast Asian Perspective .” Progress in Human Geography 22 (4): 497–522.

- Roberts, Brian H. 2014. Managing Systems of Secondary Cities. Brussels: Cities Alliance and UNOPS .

- Robinson, Jennifer. 2016. “Comparative Urbanism: New Geographies and Cultures of Theorizing the Urban .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 40 (1): 187–199.

- Satterthwaite, David. 2016. Small and Intermediate Urban Centers in sub-Saharan Africa. Working Paper 6. London: International Institute for Environment and Development .

- Spocter, Manfred. 2013. “Rural Gated Developments as a Contributor to Post-Productivism in the Western Cape .” South African Geographical Journal 95 (2): 165–186.

- Stockdale, Aileen, and Gemma Catney. 2014. “A Life Course Perspective on Urban-Rural Migration: The Importance of the Local Context .” Population, Space and Place 20 (1): 83–98.

- Udelsmann Rodrigues, Cristina. 2010. “Angola’s Southern Border: Entrepreneurship Opportunities and the State in Cunene .” Journal of Modern African Studies 48 (3): 461–484.

- Udelsmann Rodrigues, Cristina. 2012. “Angola’s Planned and Unplanned Urban Growth: Diamond Mining Towns in the Lunda Provinces .” Journal of Contemporary African Studies 30 (4): 687–703.

- Udelsmann Rodrigues, Cristina. 2018. “Private Condominiums in Luanda: More Than Just the Safety of Walls, a New Way of Living .” Social Dynamics 44 (2): 341–358.

- Udelsmann Rodrigues, Cristina. 2020a. Intra-African Migration. European Parliament: Policy Department, Directorate-General for External Policies, Reference EP/EXPO/DEVE/FWC/2019-01/LOT3/R/04, October.

- Udelsmann Rodrigues, Cristina. 2020b. “Emergent Urbanism in Angola and Mozambique: Management of the Unknown.” In Routledge Handbook of Urban Planning in Africa, edited by Carlos Nunes Silva, 233–247. London: Routledge .

- Udelsmann Rodrigues, Cristina. 2022. “From Musseques to High-Rises: Luanda’s Renewal in Times of Abundance and Crisis.” In The Unknown African City: Space, Power and Everyday Practices, edited by Annika Teppo and Laura Stark, 215–235. London: Bloomsbury .

- van Noorloos, F. 2021. “New Master-Planned Cities in Africa: Translocal Flows ‘Touching Ground’?” In Handbook of Translocal Development and Global Mobilities, edited by Annelies Zoomers, Maggi Leung, Kei Otsuki, and Guus Van Westen, 204–215. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing .

- Veneri, Paolo, and Vicente Ruiz. 2013. Urban-to-Rural Population Growth Linkages. OECD Regional Development Working Papers No. 2013/03. http://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/urban-rural-and-regional-development/urban-to-rural-population-growth-linkages_5k49lcrq88g7-en.

- Zoomers, Annelies, Femke van Noorloos, Kei Otsuki, Griet Steel, and Guus van Westen. 2017. “The Rush for Land in an Urbanising World: From Land Grabbing Toward Developing Safe, Resilient, and Sustainable Cities and Landscapes .” World Development 92: 242–252.