Abstract

In this paper I argue that squatting provides a concrete and theoretical location for dismantling binaries between successful and failed resistance. Focusing on the development of a political and affective consciousness and the inherent antagonism within squatting above the temporality of an individual squat or occupation helps to recentre the ‘urban political’ and understand the value and power of the urban commons. I combine radical democracy and affect theory to argue for the centrality of squatting in challenging urban capitalist hegemony. Not only does squatting transform consciousness, but the physically and emotionally supportive practices that it engenders helps to return the emotive as well as the political to the urban environment. I support this claim with reference to the successful 2015 Aylesbury occupation in London, which the occupiers approached with affective solidarity and a desire to reclaim space through antagonistic urban insurrection.

No fence can contain us. No fence can keep us out. We are squatters who are not bound by the borders of the Aylesbury estate. We are residents who still have leases and tenancies. We are everyone who needs a place to stay. We are bound by nothing but this need. See you soon at Aylesbury … See you soon in all the squats. See you at every protest and minor act of resistance. See you soon everywhere. (Fight for the Aylesbury Citation2015)

On the 31st March 2015, the three-month occupation of the Aylesbury Estate in Southwark, London, ended with a final act of defiance. A large crowd gathered, masked up, and pulled down the fences surrounding what was once one of the largest social housing projects in Europe. Built between 1967 and 1977, Aylesbury was designed to house over 10,000 residents, with generous apartments and spectacular views across London, before falling into managed decline and gaining a negative reputation as a ‘sink estate’. This made it a perfect target for New Labour’s policies of ‘new urban renewal’ in the late 1990s, a by-word for regeneration-by-eviction (Lees Citation2013). Rhetoric about mixed communities, coupled with calculated stigmatisation, first paved the way for regeneration plans before a final programme for complete demolition and to completely rebuild the estate as ‘mixed communities and luxury flats.

The recent history of the Aylesbury symbolises both the destructive forces of neoliberal urban development and the potential that lies in resistance. Whilst the occupation was ultimately unsuccessful in preventing redevelopment of the estate, this doesn’t mean it was a ‘failure’. As this paper shows, too much theorising of resistance still tends to succumb to ‘post-political pessimism’, or the idea that if a project of resistance is halted, fails to stop whatever it is protesting against, is shut down, repressed, or attacked, it is deemed a failure (Gualini, João, and Allegra Citation2015). This kind of analysis, however, lacks nuance and, more often than not, overlooks the affective changes that can be wrought through participation in an action. Occupations and housing squats allow us to see between the cracks and celebrate the temporary, the fragile, the sporadic and multiple forms of resistance, suggesting that we need to reconfigure how we relate to neoliberalism: from a single expansive ideology, towards a fragile and contradictory system in which many cracks can be opened and many alternative economies, relationships and possibilities can blossom.

In this paper, I argue that incorporating squatting into theories and practices of resistance helps to circumvent dominant binaries of ‘successful’ or ‘failed’ resistance and instead provides discursive, concrete and affective locations for challenging the hegemony commonly afforded to capitalism. I support this claim through my participation in, and observation of, the Aylesbury occupation, an action which was notable for the participants’ militancy, antagonism and claims for the reappropriation of space. In this paper, I combine two often disconnected areas of contemporary thought—radical democracy and affective politics—in order to demonstrate the antagonism inherent in squatting and how this reconfigures individual and collective consciousness, recentring the ‘urban political’ (Swyngedouw Citation2007). I situate my argument using theories that emphasise the power of the temporary, the ‘crack’ and the importance of prefigurative and affective experiences to generate a more nuanced understanding of ‘political’ action and solidarity between actors fighting for decent housing. The bodily and affective support that occurs through practices like breaking bread and breaking doors can generate new political subjectivities and return the political and emotive to the urban sphere (Hemmings Citation2012). Further, the affective resonance which lasts beyond the duration of any specific political action, project or moment, demonstrates the enduring power of ‘temporary’ projects. Squatting is therefore framed as not only a key practice in the cracking open of capitalism and the reclamation of the city, but as an affective experience in and of itself—the resonance of which may outlast the timeline of any single action. As such, I hope to deepen understanding of the ways in which occupation is used by diverse groups and the potential that can arise from the struggle to reclaim urban space for common good.

Context: the housing crisis in London

The destruction of the Aylesbury can be situated in a forty-year long process of gentrification within London, beginning in 1980. The post-world-war-two British welfare state oversaw the rise of a mass state-financed social housing programme that had created 6.6 million public homes by the end of the 1970s, many in high rise blocks, which at the time were considered ‘villages in the sky’—an association that is a far cry from the ‘sink estate’ stereotypes afforded to such projects nowadays (Slater Citation2018). However, the arrival in 1979 of Margaret Thatcher’s conservative government changed this narrative, leading the way for forty subsequent years of destruction of the reputation, quality and quantity of social housing, and increasing freedom of the free market to control the housing sector. The infamous Right to Buy programme was one of the most popular policies ever introduced by a Conservative party in the UK, allowing tenants to buy their publicly rented properties at a discounted price. This led to the sell-off of over 2.7 million previously public homes over the last 30 years, since 1980 (Hodkinson Citation2012), with little in the way of replacement, as the funds generated by the sales did not return to the local authorities from which the stock was sold.

This process has been complemented with the sale of entire estates to Housing Associations contributing to an additional 1.5 million homes out of the public housing stock (Hodkinson Citation2012, 510; see also Ferreri Citation2020; Penny Citation2022). However, this was a cloak for further privatisation as part of the 2000 ‘Urban Renaissance Agenda’, aiming to bring the middle classes back to the city (Davidson and Wyly Citation2012). This New Labour neoliberal strategising was epitomised by Blair giving his first major speech as Prime Minister at the Aylesbury Estate in South London, a symbol of urban despair and denigrated social housing. This estate was later sold off to a private company for complete demolition and rebuilding as luxury apartments and we will look at the subsequent resistance movement in the next section of this paper. As such, the Aylesbury symbolises both the destructive forces of neoliberal urban development and the potential that lies in resistance to its machinations. Therefore, gentrification and dispossession in cities such as London has been two-fold: bottom-up as caused by Right to Buy and similar schemes which turn residents into agents of gentrification, and top-down as caused by regeneration schemes and corporation-government partnerships, designed to ‘maximise the market potential of centrally located council estates’ (Hodkinson Citation2012, 513).

London also has a long history of organised resistance to housing insecurity including a squatters’ movement that was especially active in the seventies and eighties, despite general media hostility (Milligan Citation2016; see Vasudevan Citation2017). This long history of occupation and resistance and the ambivalence towards squatters created a rich history of struggle while establishing the practice as a recognisable part of the city landscape. However, in 2012, the new coalition government criminalised the practice in residential properties. Squatting in commercial properties such as pubs, hotels, and warehouses was still legal, while occupying residential properties was only unlawful if there was intention to live in them (Finchett-Maddock Citation2014). In practice, the occupation of a residential property as a form of protest or as a communal social space does not fall under the act. This loophole was utilised during the wave of council estate occupations that swept the city in 2014–2015 in open defiance of the squatting ban and as a collective embodiment of resistance to the wholesale destruction of council estates across the city. Starting with the Focus E15 empty homes campaign in Stratford in late 2014, council estates were soon occupied across the city, from Sweets Way in the North, to the Aylesbury and Guinness Estates south of the river. For all of these occupations, a simple notice was posted: ‘This is a protest occupation: section 144 LASPO does not apply’.

The localised context of the Aylesbury occupation is that of an intensive decade of social cleansing and estate demolition across South London. Just a few streets away from the Aylesbury is the site of the former Heygate estate, once housing over 3,000 people and demolished as part of the regeneration of Southwark between 2011 and 2014. While local residents were promised a better quality of neighbourhood and of life, the reality was mass displacement. This was an omen for those next on Southwark’s council’s hit list. In her article regarding the ‘New Urban Renewal’ of the Aylesbury, Lees highlights the attempts to create a false ‘consensus’ regarding the regeneration of the estate through initiatives such as the Creation Trust, which she defines as a ‘post-political construct par excellence—a consensus-building mode of engagement and participation … which ultimately serves to legitimate policies that privilege economic growth’ (Citation2013, 931). However, she states that ‘despite its best efforts, neoliberal governance has not managed to kill local politics on and around the Aylesbury Estate’ and further posits that these forms of local politics are exactly what Swyngedouw (Citation2007) sees as the ‘antidote to the post political’ (Lees Citation2013, 937). In 2013, these incipient forms of resistance were from a mixture of residents who wanted to reclaim their estate from the narrative of ghettos and sink-estates, local groups such as Southwark Notes who fought for urban justice in their locality, the dissent that manifests in everyday acts of resistance such as graffiti, and widespread community refusal to be co-opted into faux-consensus processes such as the Creation Trust. These early acts of contention, accompanied by escalating plans for redevelopment and demolition, paved the way for the militancy that sprang up in spring 2015, in the form of the Aylesbury Occupation.

It is in this context that the Aylesbury Estate was occupied at the end of January 2015 following the March for Homes, in protest against the demolition of the estate and the broader processes of neoliberal urban redevelopment across London. The occupation occurred simultaneously with other forms of protest against the demolition organised by other groups within the Radical Housing Network, such as Defend Council Housing and Aylesbury Tenants and Leaseholders First. Taken together, the actions also pointed to a main theme of this paper, namely the importance of moving beyond individual actions and awareness-raising towards generating a new and powerful way of being-in-common, of affecting solidarity and creating a sense of community that can transcend a ‘moment of rupture’ and return the political as well as the affective to the city.

Positionality and methods

As a participant of this occupation, who lived in the occupation for the full three months of its existence, my impressions are largely from personal and collective reflections, complimented by analysis of the literature and materials produced from those within the occupation and broader campaigns oriented around the estate. I orient my research within the tradition of militant ethnography (Juris and Khasnabish Citation2013) wherein my research is a product of my active political involvement in a project, rather than my participation conditioned by my research. I lived within the site, along with a rotation of other squatters, housing activists and sympathisers. I was involved in decision-making processes, wrote several of the online statements and analyses the occupation produced, involved myself with cooking, cleaning, caring and other social reproductive and affective forms of home-making and day to day political organisation, as well as some of the more antagonistic activities which took place. My analysis is derived from my personal experiences, conversations with other participants both during and after the occupation, as well as the theoretical and grounded literature I have consumed on the subject, particularly that of affect, which I found a key mechanism through which to untangle the experience as I felt no other body of theory was able to situate the emotional as well as practical legacy of the occupation. While I have talked broadly about my commitment to militant ethnographic methods, within the geographic tradition specifically, I follow Cloke (Citation2002) in recognising that I am a researcher because of my commitment to the political and spatial struggle my research subjects are engaged in, not the other way around. ‘[Q]uestions about living ethically and acting politically as human geographers are integrally wrapped up in the life experiences of the individual’ (Cloke Citation2002, 588). This is particularly significant if the subject of one’s research is emotion and bodily experiences.

I can then offer something further than the simple recognition that involvement in one’s research subject politically is desirable. My insider status is not only a doorway to a rich and often inaccessible investigative topic. My research is preceded by my involvement. To put it simply, I was a squatter first. Between 2014 and 2016, I was a member of the London squatting movement, with the understanding that ‘movement’ is here a loosely defined term. I lived both in squats that were generally oriented towards being a home, and squats with an explicitly confrontational orientation, such as occupations of council estates which were facing demolition, in which they functioned both as a home and as a political protest. During this time, I took part in multiple political occupations, such as Focus E15, the Guinness Occupation, and the Fight for the Aylesbury, as well as living in squats that were primarily for us, the ‘crew’, to have as a home. My research is explicitly drawn on these previous experiences and the conversations and actions that I have been privy to. I am a continuous advocate and campaigner both for repealing the current criminalisation of residential squatting and against the drive to criminalise non-residential squatting. This commitment is reflected in my research, with the one complementing the other in terms of broadening knowledge and political awareness of the legitimacy of squatting as a solution to the housing crisis and its implications in reorienting our understandings of space and the home within the city.

Squatting and the urban commons

Whilst there is a growing literature around the squatting movement in London, much of this is historical, analysing and documenting the impact of the squatting movement during its peak in the 1970s and 1980s (Wates and Wolmar Citation1980; Reeve Citation2009; see also Cook Citation2013; Vasudevan Citation2017; Wall Citation2017), whilst more recent research deals with the changing face of squatting since residential squatting became criminalised in 2012 (Finchett-Maddock Citation2014; Dadusc and Dee Citation2014). In the wider European literature on squatting, one of the most cited studies in squatting attempted to generate a typology of the different ‘types’ of squatters based on their socio-economic status, activities and political leanings (Pruijt Citation2012), but this has since been critiqued by myself and others for creating a false binary between political and deprivation squatters which fails to acknowledge the radical act of occupation in itself (Milligan Citation2016; Polanska Citation2017).

More recently, there have been several outputs exploring the relationship between squats, occupations, and the right to the city. I am building upon the work done in relation to squatting and urban commoning by Dadusc (Citation2019), Grazioli (Citation2017), Martinez and Polanska (Citation2020), among others. Grazioli argues that the right to the city framework can be used even in describing the temporary or the unstable, ‘that right to the city as exerted into housing squats does not make promises, nor does it seek recipes for success and revolution … the right to the city [is] a powerful tool for interpreting the unstable and transient nature of urban space, and confronting those living inside and against’ (Grazioli Citation2017, 406), which corroborates my argument for the value of temporary interventions. Further, Deanna Dadusc’s work on squats as commoning practices offer several important intersections with my work on the affective and emotive experience of squatting (Citation2019). Dadusc explores the importance of the urban commons, arguing that they:

entail the active creation of alternative forms of life through the creation of heterogeneous networks of solidarity, mutual aid and cooperation in resistance to the commodification of every aspect of social life … Autonomous modalities of organising everyday life and the creation of common urban spaces produce the conditions for the prefiguration of social relations and political practices that operate against, counter and contest the norms and rationalities of neo-liberal capitalism. (Citation2019, 172)

In their 2020 editorial to a special issue on squatting and the urban commons, Martinez and Polanska define the urban commons as ‘the collective self-management of resources, spaces, services, and institutions located in urban settings which are deemed essential for social reproduction’ (Citation2020, 1246). While I broadly agree with this definition, I feel the role of solidarity and collective emotion which intangibly bind together the in-common dimension of the urban commons is under-articulated. As such, I favour Papadopoulos and Tsianos’ definition of the mobile commons as ‘a world of knowledge, of information, of tricks for survival, of mutual care, of social relations, of services exchange, of solidarity and sociability’ (Citation2013, 190; in Dadusc, Grazioli, and Martínez Citation2019).

Drawing on these rigorous explorations of commoning, in this piece I narrow the focus to the inclusion of ‘care’ and ‘solidarity’ within Papadopoulos and Tsianos’ list of communing attributes, and why they ought to be centred in understandings of squatting and occupation as a commoning practice. While the inherently political act of occupying urban space has been acknowledged in broader social movement literature (Chatterton and Hodkinson Citation2007; Swyngedouw Citation2007; Tonkiss Citation2013; Springer Citation2016), the emotional resonance and affective dimensions of the reappropriation of space and squatting have not been fully explored.

Dismantling neoliberal hegemony and possibilities for alternatives

Neoliberalism is generally defined as the simultaneous processes of opening up national economies to global institutions and multinational corporations, the liberalisation of international markets and the increasing role of non-state actors in national, regional and local governance (Harvey Citation2007). The impact of neoliberalism since the 1970s has fundamentally restructured cities across the world, leading to the decline of democratic processes and increasing socio-spatial polarisation. ‘When we refer to the neoliberal city […] we are describing the dynamics through which the neoliberal ideology is applied to urban policy’ (Walliser Citation2013, 5). The commodification of urban space occurs in terms of employment, housing, and leisure space, leading to the creation of exclusive urban spaces and the expulsion from the inner-city of those deemed not fit or able to contribute to the new urban imaginary of a space of consumption (Brenner and Theodore Citation2002).

There, nevertheless, remains a tension in the literature between describing neoliberalism as a hegemonic project and theorising the potential for resistance against its strictures and impositions. Gramsci defines hegemony as ‘the ‘spontaneous’ consent given by the great masses of the population to the general direction imposed on social life by the dominant fundamental group; this consent is ‘historically’ caused by the prestige (and consequent confidence) which the dominant group enjoys because of its position and function in the world of production’ (Gramsci Citation1971, 12; in Lears Citation1985). A hegemonic reading of neoliberalism (Harvey Citation2007) has, in this context, faced critique from feminist, anarchist, and post-colonial scholars, who beg caution towards inscribing neoliberalism with the hegemonic power it has commonly been afforded. The fact that neoliberalism is so broad means that it cannot be monolithic. The fact that it operates on multiple scales means there are multiple points of entry and exit, different variants of neoliberalism. Attention must be paid to the hybrid nature of the global neoliberal project and the ‘multiple and contradictory aspects of neoliberal spaces, techniques, and subjects’ (Larner Citation2003, 509). Critical academia has a responsibility to not simply reiterate the status quo as we see it, but to look closely at processes and complexities which initially seem monolithic. Current definitions of neoliberalism need to be disrupted and challenged. McKinnon accuses these capitalocentric discourses of a ‘paranoid stance’, which, in their words:

habituates us to seeing only examples in the world that reinforce and repeat familiar narratives—in this case our narratives of what is wrong. There is a perverse pleasure in paranoia and a joy attached to being able to see here, and everywhere, again, another example of neoliberal devastation, or neo-imperialist dispossession, or capitalist exploitation. (McKinnon Citation2016, 345)

Set against this backdrop, I break away from a reading of neoliberalism which emphasises the dominance of the neoliberal model, towards more post-structuralist and anarchistic perspectives, which emphasis the potential available in gaps and fractures, rather than the pessimism evoked by focus on the monolith. This allows us to think more carefully about other forms of power, wherein spaces, states and subjects are constituted in various forms through both state and non-state processes. It enables analysis of neoliberalism to expand into new and important domains such as bodies, households, families, sexualities, and communities. To fully conceptualise alternatives, we must dismantle the hegemony commonly afforded to neoliberalism, not only on the streets but within the academy and follow other forms of communing that re-image the city as a space of solidarity and connection.

Antagonism and affect

Revolutionary movements do not spread by contamination but by resonance … An insurrection is not like a plague or a forest fire … It rather takes the shape of music. (The Invisible Committee Citation2009, 12)

Radical democratic scholars have identified the current era as one in which the ‘post-political condition’ structures and controls the nature of state and non-state relationships and the possibilities of dissent and rebellion. Gualini, João, and Allegra (Citation2015), for instance, warn against the pacification of struggle which occurs when the framework of debate is co-opted and embedded within the parameters of the institutional order of ‘liberal-global hegemony’ (Swyngedouw Citation2007, 65), identifying this phenomenon as ‘post-political’. Yet, in terms of squats and occupations specifically, there are limits to this agonistic framework promoted by radical democratic scholars. As argued by Kebir (Citationn.d.),

[under ‘agonistic democracy'] … conflict is defused and deprived from its radical potentialities, namely a radical struggle against domination that does not entail any element of communication—which is one necessary condition for overcoming the domination we are dealing with.

Due to the limitation of the post-political framework in conceptualising possibility, I hybridise the understandings of uprisings within the post-political neoliberal city with analysis of the importance of ‘cracks’ and the significance of the temporary. The concept of cracks within capitalism comes from John Holloway’s (Citation2010) arguments that individual actions can create ‘cracks’ in capitalism’s buttresses, by asserting alternative ways of living. Choosing not to go to work but instead read a book in a park is a concrete act of resistance. Small can be beautiful. Beyond prefigurative living, cracks can also take on a concretely spatial form, in terms of occupations of urban spaces, guerrilla gardening, the refusal to relinquish public space to control and surveillance. Tonkiss (Citation2013) refers to these potentialities as ‘ordinary audacities’, which can occur in the cracks of formal planning, speculation and local possibility. Opening up spaces in cracks between capitalism’s edifices and structures is key to reclaiming the city, as well as actively living differently by treating each other as actors rather than subjects, crumbling the façade of capital to create a new space of possibility and political subjectivation. Occupations and squats are a concrete and spatial manifestation of this concept.

Squatting represents a conflict that the state cannot domesticate because its existence is directly confrontational with a major foundation of the status quo: property. One of the characteristics that set apart the post-2008 wave of insurrections and uprisings is a shift from demands that could be reconciled within the post-political consensus framework, such as demands for housing, transport, better environmental quality, towards claims on a broader scale, such as for a fair and equitable society, a dismantling of capitalism and an end to neoliberal redevelopment of urban space. The observation of the different nature of urban rebellion is accompanied by a theoretical shift led by a desire to ‘place politics at the heart of radical urban political theory and practice’ (Dikeç and Swyngedouw Citation2017, 2). Dikeç and Swyngedouw consider these urban insurrections ‘incipient political movements’ that institute ‘new forms and choreographies of urban political acting’ (Citation2017, 2). Instead of single-issue claims that could be contained or pacified by neoliberal participation politics they demand wholesale a new process for producing space politically (Lefebvre Citation1974). As such, an emphasis on the immanent, incipient and experimental forms of these new insurrections is needed in order to understand the significance of both the temporary, in terms of evoking a new urban imaginary, as well as the prefigurative potential that arises from engagement in such a struggle.

Peck and Tickell argue that ‘the defeat (or failure) of local neoliberalisms—even strategically important ones—will not be enough to topple what we are still perhaps justified in calling ‘the system'’ (Citation2002, 401). An affective approach, however, allows us to emphasise how involvement in these occupations changes hearts and minds, and functions as a politicising process for those involved (which is just as significant as concrete political goals being achieved). An affective disposition is required to demonstrate that in various ways both the politicisation processes, in terms of returning ‘the political’ to urban struggles, and recognising the importance of changing ‘hearts and minds’ as central to urban anti-capitalist struggle. In his Citation2017 article, Duff argues that ‘the materialisation of the right to the city is embodied in the social, material and affective occupation of urban spaces’, what he refers to as the ‘affective right to the city’ (1). This process of change of individual and collective consciousness as well as the urban form is what García-Lamarca (Citation2017) among others refer to as a process of ‘political subjectivation’. However, I wish to emphasise that beyond consciousness, meaningful change is achieved through affective and bodily being-in-common. Affect, as outlined in Gregg and Seigworth’s edited volume, is precisely located in the ‘midst of in-between-ness: in the capacities to act and be acted upon’. It can be a ‘momentary or sometimes more sustained state or relation … of forces or intensities’ (Citation2010, 1). This in-between-ness, emphasising both the moment and the aftermath of an event or prefigurative change is central to acknowledging that the power of the temporary exists not just in the momentary ‘eruption’ but also in the longer-lasting effects of such a ‘rupture’. Lancione, in turn, writes of the visceral and bodily experiences which constitute the urban experience:

It is the city—with its carnality of pavements and rusty platforms, of cold benches and shadowy galleries, of mechanistic speed set against the tempo of a human body, of crowded shelters and social services; with its atmospheres of indifference and hate, of solidarity and joyfulness, of discrimination and playfulness—which entangles with the bodies, souls and dreams of the people that navigate its terrains. (Citation2017, 12)

The interweaving between the urban form and those who dwell within, and shape, it, is the territory my analysis seeks to explore.

The physicality of an occupation, the feelings that are evoked from the concrete being-in-common are as significant to the value of a project and its possibilities regarding urban change as the knowledge that you are in it together. Thus, I follow scholars such as Woodward and Lea (Citation2010) in developing the concept of subjectivation and the importance of space into an affective orientation.

Affects are in this sense a collective endeavour, emerging from the makings of any assemblage or, to say it differently, from the ‘composites of place’. If the capacity to affect and be affected belongs to each individual element, the instantiation of that capacity (which we call affect) can be understood and grasped only in its unfolding, namely, in the interaction between bodies, in their frictions, attunement, dispersal and perturbations. (Lancione Citation2017, 6)

As Deborah Thien says, ‘affect is the how of emotion. That is, affect is used to describe (in both the communicative and literal sense) the motion of emotion’ (Citation2005, 451; emphasis added). An inclusion of affective perspectives is vital for understanding the longer-term resonance of urban insurrections and social struggles, in terms of those who engage but also those who gain encouragement or ‘politicisation’ through observing the actions, successes, failures, and dialogues produced by the movement itself. As Spinks reminds us, what we code as the political must subsequently expand to include ‘the way that political attitudes and statements are partly conditioned by intense autonomic bodily reactions that do not simply reproduce the trace of a political intention and cannot be wholly recuperated within an ideological regime of truth’ (Citation2001; 23 in Thrift Citation2004, 64). Understanding affective and politicising changes in attitudes and behaviours is fundamental to understanding why different political struggles took different paths, embraced different ideologies, and manifested in different forms of praxis.

I use the example of the Aylesbury Estate Occupation of 2015 to make a case for why the inclusion of squatters actively within one’s solidarity praxis is fundamental for a truly radical and oppositional urban politics. This is a case which moves beyond individual actions and awareness-raising towards generating a new and powerful way of being-in-common, of affecting solidarity and creating a sense of the urban commons that does not depend only on local history and ties, nor on singular strategies or voices, in order to transcend a ‘moment of rupture’ and return the political as well as the affective to the city. The occupation, as I argue, was an explicitly antagonistic form of protest that nevertheless engendered a common politics of affect and solidarity among the occupants, debunking the idea that agonism is the only means through which an alternative politics can be realised.

Squatters and tenants unite! A case for the temporary and impermanent

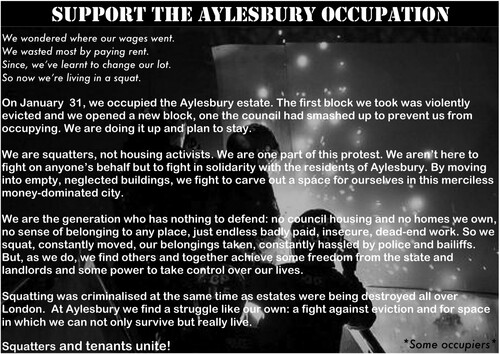

We are squatters, not housing activists. We are one part of this protest. We aren’t here to fight on anyone’s behalf but to fight in solidarity with the residents of Aylesbury … squatting was criminalised at the same time as estates were being destroyed all over London. At Aylesbury we find a struggle like our own. (Extract from Aylesbury Occupation flyer, 2015 see )

Figure 1: Flyer from the Fight for the Aylesbury campaign website: https://fightfortheaylesbury.wordpress.com/.

At the Aylesbury Occupation, some squatted for housing need, some identified as housing activists, but most seemed to fall somewhere between the two. But an awareness and effort existed to keep all these motivations working together rather than creating unnecessary divisions for the media or the council to exploit. Simply living in a squat and facing the daily repression by the state and landlords radicalises many people. Experiences of solidarity and collective action make many people realise their own capacity for self-determination and control over their own lives. Part of the collective action that squatting entails is realising that ‘the authorities’ are not there to protect squatters and are in fact what the squatters are resisting (Milligan Citation2016). Self-determination and political subjectivation were often realised through experiences of mutual aid and collective action, a necessary feature of squat survival, not only between squatters but between all who resist the neoliberal redevelopment of London (see ).

Figure 2: Sticker designed by me which was distributed around the neighbourhood surrounding the Aylesbury. Photo: Rowan Milligan.

Temporary, impermanent or overtly anti-capitalist projects are often critiqued on the basis of their outsider status inhibiting their ability to affect change, thus are only considered truly political if they achieve a degree of permanence or continuity (Dikeç and Swyngedouw Citation2017). Due to the illegality or confrontational nature of their praxis, many projects, occupations, sites and acts of resistance are temporary, and thus considered ineffectual. However, in recent years arguments have been put forward for a reinterpretation of the importance of temporary occupations and uses of urban space. In her article on ‘austerity urbanism and the makeshift city’, Tonkiss (Citation2013) suggests that rethinking the importance of time and delay in terms of urban activism is necessary. To capitalists, ‘money is time’, and this line of thinking is followed by mainstream development companies and planners who rigorously ensure they stick to a fixed cost-schedule analysis in their urban development projects. Thus, to undermine or to delay these processes can in itself be a significant criterion of success for an urban project. What Clausen refers to as ‘spaces of deceleration’ and Hodkinson terms ‘the power to delay’ (Clausen in Tonkiss Citation2013, 320; Hodkinson Citation2012, 515) can be significant tools, not only in delaying a specific redevelopment project, through occupying the site of development or barricading the entrances, but can also help to prefigure a different type of urban future through the celebration of the temporary, not just as a failed attempt at permanent but as a significant urban intervention for its own sake (Tonkiss Citation2013). If we consider the power to delay a strategy of resistance in its own right, we are able to resurrect urban movements from the dichotomy of the institutionalise-or-not debate regarding success and consider their smaller actions, their ‘cracks’, their emotional impact, as legitimate marks of ‘success’.

However temporary, sites of commonality have the power to subvert the preclusions of private property and the prescriptions of the state and generate free spaces which have the power to change hearts, minds, and the development of the city, through the development of the urban actors who live within it. After all, as Lynch wrote in 1968, ‘the guerrillas of the future will need a base of operations’ (Lynch [Citation1968] Citation1995, 780). The creation of these bases and the defiance with which they are defended and promoted are vital, not only despite, but also because of their temporality for something which can pop up and disappear has the power to pop up again, to multiply, to spread cracks throughout the city. As Pickerill and Chatterton conclude:

Autonomous projects face the accusation that, even if they do improve participants’ quality of living, they fail to have a transformative impact on the broader locality and even less on the global capitalist system … However, commentators make the mistake of looking for signs of emerging organisational coherence, political leaders and a common programme that bids for state power, when the rules of engagement have changed. A plurality of voices is reframing the debate, changing the nature and boundaries of what is taken as common sense and creating workable solutions to erode the workings of market-based economies in a host of, as yet, unknown ways. (Citation2006, 738–739)

The temporary can be a tool, as well as an obstacle, and success can be calculated on the ability to frustrate and delay and the lasting impact it has on its participants and observers, as much as on the ability to achieve institutional recognition or power.

The importance of affect and solidarity

Living together side by side, day by day, created bonds of affinity that could not be wrought through attending meetings and blockading gateways alone. The bodily experiences of eating together, with food brought up by residents by rope when we were blockaded in, of people turning up, asking what we needed, providing literature for when we were blocked in by police and bored—all these encounters sought to highlight what is important beyond the concrete task of delaying demolition: generating new ways of living together, of creating human friendships, of re-igniting that sense of community destroyed by capitalist urban redevelopment. The antagonism towards ‘them’ strengthened the political and emotional bonds between the ‘us’. Solidarity is an emotional experience as much as it is a rational political stance. Here my experiences echo those of Lancione, articulating his own experiences of being in common:

[t]he food, its preparation and the act of sharing it produced an invigorating sense of commonness and scope that exceeded any specific body assembling the occupation of Vulturilor’s street sidewalks. The same affection was produced by seemingly insignificant assemblages like the exchange of cigarettes around the fire; by borrowing the wi-fi from neighbours; by buying coffee from an automatic machine. (Lancione Citation2017, 11)

As Cohen (Citation2020) notes in his discussion on the affective possibilities of the riot, ‘the joy of the riot, however, is qualitatively different from the pleasures of private life. Acting as a collective force, the protestors experience a form of joy more akin to public happiness … public happiness emerges from the experience of collective power, that is, participating in public with others in such a way as to organise the affairs of our common lives’ (Citation2020, 161). Similarly, Tyler, writing on the 2011 London riots suggests that ‘the riots created a temporary space of negative freedom, a seemingly autonomous zone in which young people were able to make their rage visible and enjoy themselves in the process’ (Citation2013, 203, my italics). The same can be said of the occupation. By enduring and sharing and finding joy in the daily life of resistance we find ourselves shifting and changing, experiencing mutual care and compassion in struggle which eludes us in the atomisation and isolation of daily life under normative circumstances. The action of living politically not only broadens our horizons of possibility for everyday life but the act of the struggle itself is a constitutive aspect; ‘pleasures emerge from action-in-concert that simultaneously renders the law inoperative as it opens up a public space of autonomy’ (Cohen Citation2020, 162). There is an incredible power in the de-arrest, the action of finding yourself isolated and attacked by the state forces only to be rallied around by friends and allies and comrades, most not yet made known to you, but brought together by a shared passion. Feeling their arms physically pulling your body away from those who seek to assault it, to be encircled, protected by strangers and knowing fully in your heart that you would do the same for them. This feeling cannot be quantified or measured; it is beyond the bounds of the logic of the state. Those people may fade away, you may never see them again, but the trust and compassion remain. The exhilaration of the small collective victory occurs again and again if you let it. Popping up, re-emerging, dying down only to be reborn elsewhere, much like squats themselves. This is why the joy we find in struggle endures far beyond the lifespan of a single project, if only we know to look for it.

This sense of solidarity also extended to the broader housing movement. Squatters consistently emphasised the importance of unity with tenants and residents, and the strength of a united neighbourhood. Housing activists, residents and squatters would turn up to each other’s evictions, help build each other’s barricades, and offer each other aid when needed. One example of solidarity was the many supporters who turned up after the Aylesbury’s Twitter call-out during the aggressive eviction in which people engaged in clashes with the police. Solidarity means self-determination, which often leads to a reconceptualization of one’s place in society, rights, and autonomy. At the Aylesbury, the squatters leafleted around the neighbourhood and also held two information and fun days, with crepes, bouncy castles and information boards in order to connect with the tenants. Working with tenants and residents on campaigns against property developers and rent hikes builds trust and is able in many cases to resist the efforts of the state to polarise squatters and tenants. Connections of friendship grow between individuals who struggle together against a common enemy.

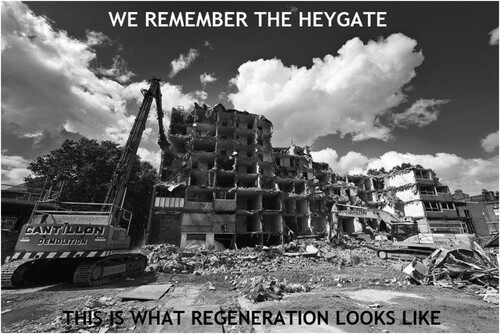

Central to the ethos of the Aylesbury occupation was the desire to raise awareness of the interconnectedness of the different housing struggles across London and emphasise the similarities between tenants, leaseholders and squatters against those who sought to evict all of them. One of the ways of doing this was by evoking the lessons of the Heygate Estate, formerly up the road from the Aylesbury at Elephant and Castle, which, under the name of ‘regeneration’ had been entirely demolished, its residents scattered throughout London and the replacement with luxury flats owned by international property moguls. The Heygate served not only as a physical and spatial reminder of the outcomes of regeneration but also a visceral, emotional one. The stakes, and the connections between different struggles were laid bare and the resonance of former struggles formed part of the emotional drive to engage in future ones (see ).

Figure 3: Flyer from the Fight for the Aylesbury campaign website: https://fightfortheaylesbury.wordpress.com/.

Like many of the housing resistances across London, the Aylesbury Occupation was centred on a single site. However, the occupation transcended the framework of a simply local struggle. Squatters, after all, are oftentimes a mobile population, a mobile commons (Papadopoulos and Tsianos Citation2013). If we have a ‘neighbourhood’ it is a temporary construct only. While we may feel affinity with different localities due to experiences of living there or working there, we are not rooted. Therefore, much of the traditional discourse around neighbourhood solidarity does not apply to squatters.Footnote1 What particularised the Aylesbury occupation was that people from across London (and the world) decided they would take a stand, decided they would fight for this estate, not because it was ours but because it represented the struggle across London and across Europe, the struggle against dispossession. This was significant because the ideology was not then ‘they deserve to keep this because it’s theirs’ but that ‘everyone has the right to live here, even us’. I argue that this is more of a revolutionary or prefigurative approach to squatting and housing action than the territoriality you often see in resistance movements. While people, of course, fight for their locality, the idea of fighting for somewhere because you should or because it’s right rather than because it’s yours resonates more with the concept of making-public which I highlighted above. Reclaiming or expropriating a common space for whoever is far more radical, and antagonistic to capital, than staking a claim of ownership based on legitimacy under property law.

Paramount to much squatting ideology and practice is the assertion that a space does not belong to a single individual but rather to a collective, with their own self-defined limits (Occupato, Occupato, and Landstreicher Citation1995). Ideology becomes manifest through emotion—you have to feel solidarity in order to enact it. Enacting and feeling the desire to share space overrides any residual feeling of ‘mine’ and lays the groundwork for arguments not just in favour of public space and the social production of such space, but also for the public-isation of space. Activities of making-public are fundamental to the practice of squatting; to take a space formerly accessible to only a privileged few and opening it up to a broader range of participants is an empowering political and emotive act (Tonkiss Citation2013). Public space is not just defined by its urban ‘but public space is always as well a set of social relations and social (inter)actions in the city’ ergo making-public also has an affective disposition (Knierbein Citation2017, 102, my emphasis). An agonistic framework does not give adequate space for the violence sometimes necessary in claiming a space as (y)ours and the broader public-ising of space and an affective disposition is needed to find joy in the endeavour.

Conclusion

The radical nature of squatting needs to be reasserted and the active antagonism so often present between squatters and institutional structures needs to be celebrated and engaged with so that the radical potential of squatting, as suggested by the militancy of the Aylesbury occupation, can be unlocked. By recognising the myriad ways we can come together both from within and beyond our individual positions within the capitalist housing system we demonstrate not only our own strength but the porousness of the structures that contain us and strive to keep us separate. Squatters and tenants and leaseholders are more alike than they are separate, and the Aylesbury exemplifies the strength that can come from that unity. Further, to engage in squatting acts that are not territorialised to justify their legitimacy, that are not confined within a single strategy, that are not tied but are multiple and fragmented, offers a possibility of a new way of organising politically, in solidarity and kindness and support, regardless of local, national, or international boundaries. A multiplicity of attempts, of delays, of inconveniences to the forces of accelerated urban development destabilises the monopoly on urban decision making that property developers and local authorities strive to maintain. It also undermines the ‘post-political pessimism’ I have mentioned—if we do not strive only to overturn or to stop completely but take joy in the inconvenience and the ever-multiplying possibilities for this (as the city is increasingly broken up and redeveloped), we can more easily recognise the value and significance of our actions, even (or especially) if temporary.

Beyond the practicalities of delaying redevelopment, I have also attempted to emphasise the ways in which squatting can be politically and affectively transformative, radicalising people through experiences of solidarity, self-determined action, and communal living. Squatters’ discourse of mutual aid undermines claims for capitalism’s supposed omnipotence, as their practices of nurture and care demonstrate the limits to its economic capabilities. Recognising the significance of affective transformation more readily enables us to see the political importance of the everyday, the minute, the cracks. These cracks in the system provide both discursive and concrete locations for what anarchist theorists call prefiguration: the reappropriation of everyday life and blossoming of possibilities for the transformation of existence.

Affect and solidarity are the fragments that last when the physical matter of a project, be it a protest, occupation, or riot, has faded away. But feelings linger. Sensations remain. I can still recall, six years later, how I felt participating in the Aylesbury Occupation, even if I have forgotten specific events, logistical details, even faces. I still recollect the exhilaration and camaraderie and fear and joy in a collective project. And this is not mere nostalgia, wistful reminiscence of a wild youth. Whenever I am in a phase of life where I am not engaging in as much on the ground struggle, these feelings are what I remember, what I miss. And, ultimately, these feelings, this lingering affect, is what makes me get involved all over again. A different fight perhaps, in a different location almost certainly, and with different people. But always with a common intent, a collective effort and with solidarity and friendship that contains the echoes of previous struggles, and adds new voices to the clamour.

Under the current neoliberal urban development and increasingly hostile trespass and protest laws, the possibilities of squatting are increasingly limited. More research that explicitly highlights the absurdity of empty buildings and increasing homelessness must be carried out and hopefully put into policy as the current status quo is untenable. Hopefully this will lead to further autonomous and insurrectionary action. Perhaps it will even lead to politicians and policy-makers actually recognising the logic of squatting as a solution to the housing crisis. But, while I will hold my crowbar ready, I won’t hold my breath.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Professor Mathieu Van Criekingen and Dr Antonis Vradis for help with earlier drafts of this paper, to the anonymous reviewers who helped me hone my ideas, to the CITY editors for their patience and insight, and to Sam Burgum and Alex Vasudevan for curating this Special Feature and offering advice and support throughout. Most importantly, thank you to all squatters everywhere for continuing to fight for a liberatory and joyful urban sphere.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rowan Tallis Milligan

Rowan Tallis Milligan is a PhD Candidate at the School of Geography & Sustainable Development at the University of St Andrews. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 I would add, this is particularly the case since 2012. Before the law changed in 2012, criminalising residential squatting, squatters in London were far more likely to stay in one building for several months or years.

References

- Brenner, Neil, and Nik Theodore. 2002. Spaces of Neoliberalism: Urban Restructuring in North America and Western Europe. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing .

- Chatterton, Paul, and Stuart Hodkinson. 2007. “Why We Need Autonomous Spaces in the Fight Against Capitalism.” In Do it Yourself: A Handbook for Changing our World, edited by Trapese, 201–215. London: Pluto .

- Cloke, Paul. 2002. “Deliver Us from Evil? Prospects for Living Ethically and Acting Politically in Human Geography .” Progress in Human Geography 26 (5): 587–604. doi:10.1191/0309132502ph391oa.

- Cohen, Aylon. 2020. “Sovereign Chaos and Riotous Affects, Or, How to Find Joy Behind the Barricades .” Capacious: Journal for Emerging Affect Inquiry, doi:10.22387/cap2020.40.

- Cook, Matt. 2013. “‘Gay Times’: Identity, Locality, Memory, and the Brixton Squats in 1970s London .” 20th Century British History 24 (1): 84–109. doi:10.1093/tcbh/hwr053.

- Dadusc, Deanna. 2019. “Enclosing Autonomy: The Politics of Tolerance and Criminalisation of the Amsterdam Squatting Movement .” City 23 (2): 170–188. doi:10.1080/13604813.2019.1615760.

- Dadusc, Deanna, and E. T. C. Dee. 2014. “The Criminalisation of Squatting: Discourses, Moral Panics and Resistances in the Netherlands and England and Wales.” In Moral Rhetoric and the Criminalisation of Squatting, edited by Lorna Fox O'Mahony, David O'Mahony, and Robin Hickey, 108–131. Abingdon: Routledge .

- Dadusc, Deanna, Margherita Grazioli, and Miguel A. Martínez. 2019. “Introduction: Citizenship as Inhabitance? Migrant Housing Squats Versus Institutional Accommodation .” Citizenship Studies 23 (6): 521–539. doi:10.1080/13621025.2019.1634311.

- Davidson, Mark, and Elvin Wyly. 2012. “Classifying London: Questioning Social Division and Space Claims in the Post-Industrial Metropolis .” City 16 (4): 395–421. doi:10.1080/13604813.2012.696888.

- Dikeç, Mustafa, and Erik Swyngedouw. 2017. “Theorizing the Politicizing City .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12388.

- Duff, Cameron. 2017. “The Affective Right to the City .” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42 (4): 516–529. doi:10.1111/tran.12190.

- Ferreri, Mara. 2020. “Painted Bullet Holes and Broken Promises: Understanding and Challenging Municipal Dispossession in London’s Public Housing ‘Decanting’ .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 44: 1007–1022. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12952.

- Fight for the Aylesbury. 2015. “Even When We Lose in Court, We Win in the Streets. Victory to the Aylesbury!” April 2, 2015. https://fightfortheaylesbury.wordpress.com/2015/04/02/even-when-we-lose-in-court-we-win-in-the-streets/.

- Finchett-Maddock, Lucy. 2014. “Squatting in London: Squatters’ Rights and Legal Movement(s).” In The City is Ours, edited by Ask Katzeff, Bart van der Steen, and Leendert van Hoogenhuijze, 207–231. Oakland: PM Press .

- García-Lamarca, Melissa. 2017. “From Occupying Plazas to Recuperating Housing: Insurgent Practices in Spain .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41 (1): 37–53. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12386.

- Gramsci, Antonio. 1971. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. New York: International Publishers .

- Grazioli, Margherita. 2017. “From Citizens to Citadins? Rethinking Right to the City Inside Housing Squats in Rome, Italy .” Citizenship Studies 21 (4): 393–408. doi:10.1080/13621025.2017.1307607.

- Gregg, Melissa, and Gregory J Seigworth. 2010. The Affect Theory Reader. Durham, NC: Duke University Press .

- Gualini, Enrico, Morais Mourato João, and Marco Allegra. 2015. Conflict in the City: Contested Urban Spaces and Local Democracy. Berlin: Jovis .

- Harvey, David. 2007. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press .

- Hemmings, Clare. 2012. “Affective Solidarity: Feminist Reflexivity and Political Transformation .” Feminist Theory 13 (2): 147–161. doi:10.1177/1464700112442643.

- Hodkinson, Stuart. 2012. “The New Urban Enclosures .” City 16 (5): 500–518. doi:10.1080/13604813.2012.709403.

- Holloway, John. 2010. Crack Capitalism. London: Pluto Press .

- Invisible Committee. 2009. The Coming Insurrection. Los Angeles: Semiotexte .

- Juris, Jeffrey S, and Alex Khasnabish. 2013. Insurgent Encounters: Transnational Activism, Ethnography, & the Political. London: Duke University Press .

- Kebir, Ali. n.d. “Agonistic Democracy Contra Deliberative Democracy? Mouffe, Rancière & the Issue of Conflict.” www.academia.edu. Accessed 12 August 2018. https://www.academia.edu/11514878/Agonistic_Democracy_Contra_Deliberative_Democracy_Mouffe_Ranci%C3%A8re_and_the_issue_of_conflict.

- Knierbein, Sabine. 2017. “Public Space and Housing Affairs and the Dialectics of Lived Space .” Tracce urbane. Rivista italiana transdisciplinare di studi urbani 1. doi:10.13133/2532-6562_1.10.

- Lancione, Michele. 2017. “Revitalising the Uncanny: Challenging Inertia in the Struggle Against Forced Evictions .” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 35 (6): 1012–1032. doi:10.1177/0263775817701731.

- Larner, Wendy. 2003. “Neoliberalism? ” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 21 (5): 509–512. doi:10.1068/d2105ed.

- Lears, T. J. Jackson. 1985. “The Concept of Cultural Hegemony: Problems and Possibilities .” The American Historical Review 90 (3): 567–593. doi:10.2307/1860957.

- Lees, Loretta. 2013. “The Urban Injustices of New Labour’s ‘New Urban Renewal’: The Case of the Aylesbury Estate in London .” Antipode 46 (4): 921–947. doi:10.1111/anti.12020.

- Lefebvre, Henri. [1974] 1991. The Production of Space. Translated by Donald Nicholson-Smith. Oxford: Blackwell .

- Lynch, Kevin. 1968. The Possible City.

- Martínez, Miguel A., and Dominika Polanska. 2020. “Squatting and Urban Commons: Creating Alternatives to Neoliberalism .” Participation and Conflict 3 (13): 1244–1251. doi:10.1285/i20356609v13i3p1244.

- McKinnon, Katharine. 2016. “Naked Scholarship: Prefiguring a New World Through Uncertain Development Geographies .” Geographical Research 55 (3): 344–349. doi:10.1111/1745-5871.12196.

- Milligan, Rowan Tallis. 2016. “The Politics of the Crowbar: Squatting in London, 1968–1977 .” Anarchist Studies 24: 2.

- Occupato, Barocchio, El Paso Occupato, and Wolfi Landstreicher. 1995. Against the Legalisation of Occupied Spaces. The Anarchist Library. https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/el-paso-occupato-barocchio-occupato-against-the-legalization-of-occupied-spaces.

- Papadopoulos, Dimitris, and Vassilis S. Tsianos. 2013. “After Citizenship: Autonomy of Migration, Organisational Ontology and Mobile Commons .” Citizenship Studies 17 (2): 178–196. doi:10.1080/13621025.2013.780736.

- Peck, Jamie, and Adam Tickell. 2002. “Neoliberalizing Space .” Antipode 34 (3): 380–404. doi:10.1111/1467-8330.00247.

- Penny, Joe. 2022. “Revenue Generating Machines? London’s Local Housing Companies and the Emergence of Local State Rentierism .” Antipode 54 (2): 545–566. doi:10.1111/anti.12774.

- Pickerill, Jenny, and Paul Chatterton. 2006. “Notes Towards Autonomous Geographies: Creation, Resistance and Self-Management as Survival Tactics .” Progress in Human Geography 30 (6): 730–746. doi:10.1177/0309132506071516.

- Polanska, Dominika V. 2017. “Reclaiming Inclusive Politics: Squatting in Sweden 1968–2016 .” Trespass: A Journal About Squatting 1 (1): 36–72.

- Pruijt, Hans. 2012. “The Logic of Urban Squatting .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37 (1): 19–45. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2012.01116.x.

- Reeve, Kesia. 2009. The UK Squatters’ Movement, 1968–1980. Unpublished PhD thesis.

- Schaap, Andrew. 2016. Law and Agonistic Politics. Abingdon: Routledge .

- Slater, Tom. 2018. “The Invention of the ‘Sink Estate’: Consequential Categorisation and the UK Housing Crisis .” The Sociological Review 66 (4): 877–897. doi:10.1177/0038026118777451.

- Spinks, Lee. 2001. “Thinking the Post-Human: Literature, Affect and the Politics of Style .” Textual Practice 15 (1): 23–46. doi:10.1080/09502360010013866.

- Springer, Simon. 2016. The Anarchist Roots of Geography: toward Spatial Emancipation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press .

- Swyngedouw, Erik. 2007. “The Post-Political City.” In Urban Politics Now. Re-Imagining Democracy in the Neo-Liberal City, edited by BAVO, 58–76. Rotterdam: NAI Publishers.

- Thien, Deborah. 2005. “After or Beyond Feeling? A Consideration of Affect and Emotion in Geography .” Area 37 (4): 450–454. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4762.2005.00643a.x.

- Thrift, Nigel. 2004. “Intensities of Feeling: Towards a Spatial Politics of Affect .” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 86 (1): 57–78. doi:10.1111/j.0435-3684.2004.00154.x.

- Tonkiss, Fran. 2013. “Austerity Urbanism and the Makeshift City .” City 17 (3): 312–324. doi:10.1080/13604813.2013.795332.

- Tyler, Imogen. 2013. Revolting Subjects: Social Abjection and Resistance in Neoliberal Britain. London: Zed Books .

- Vasudevan, Alex. 2017. The Autonomous City: A History of Urban Squatting. London: Verso .

- Wall, C. 2017. “Sisterhood and Squatting in the 1970s: Feminism, Housing and Urban Change in Hackney .” History Workshop Journal 83 (1): 79–97. doi:10.1093/hwj/dbx024.

- Walliser, Andrés. 2013. “New Urban Activisms in Spain: Reclaiming Public Space in the Face of Crises .” Policy & Politics 41 (3): 329–350. doi:10.1332/030557313X670109.

- Wates, Nick, and Christian Wolmar. 1980. Squatting: The Real Story. London: Bay Leaf Books .

- Woodward, Keith, and Jennifer Lea. 2010. Geographies of Affect, edited by S. Smith, R. Pain, S. Marston, and J.P. Jones, 154–175. London: Sage Publications .