Abstract

This paper traces the Croatian Swiss franc loans crisis and debtors’ movement in the context of the wider politics of housing finance after the 2000s credit and housing boom. The movement mainly contested Swiss franc loans through litigation and demands for regulation of predatory lending practices. This selective and institutional articulation of the issue reflected the urban middle-class background of the movement’s constituency and its ambivalent position of having stakes in the financialized housing regime while resisting some of its consequences. Political and financial elites supported a relaunch of a more regulated version of finance-led, state-subsidized housing provision. The structural conditions resulting from the postsocialist housing privatization and the hegemonic ideology of homeownership have been instrumental in preserving the established model. Even then, the CHF loans experience contributed to a slow and gentle shift in the politics of housing towards a possibility of, and calls for, a less ownership-dominated and financialized model.

Introduction

In the early 2000s, along with other Eastern and Southern European countries, Croatia experienced a process of peripheral financialization that was driven by inflows of interest-bearing capital from European core countries in search of higher profitability (see Gagyi and Mikuš, this Special Feature). This process was, most of all, reflected in a boom in household credit and housing—from 2001 to 2008, household debt grew from 17% to nearly 41% of GDP while housing prices increased by 66% (Vizek Citation2009, 283). An important and distinctly peripheral feature of the boom was short-lived but substantial Swiss franc (CHF) lending by foreign-owned banks dominating the market. The volume of CHF loans to non-bank clients shot up from 200m CHF in 2003 to 7.7bn CHF in 2007, corresponding to their third highest share (16.4%) in Eastern Europe, surpassed only by Hungary and Poland (Brown, Peter, and Wehrmüller Citation2009, 170–171). Most CHF loans to households were housing loans, which made up nearly two thirds of the volume outstanding in 2010, while the most common among the remaining categories were car loans (11.5%).Footnote1 Following the terminology explained in the introduction to this Special Feature, the loans were mostly indexed to the franc, which meant that the principal and the repayment plan were given in the franc but installments had to be paid in the Croatian kuna (HRK)Footnote2 according to current exchange rates (Rodik Citation2015, 78, n. 1).

The strong and sustained appreciation of the franc after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) inflated the kuna values of outstanding principals and installments drastically. Debtors experienced severe financial hardship, defaults, and health and relationship issues (Rodik Citation2015, Citation2019) and organized to contest the legality and legitimacy of the loans (Dolenec, Kralj, and Balković Citation2021; Mikuš Citation2019). Responding to their pressure, the government undertook a series of pro-debtor interventions in CHF loans, eventually enabling debtors to convert their loans to the euro in 2015. Franc loans subsequently all but disappeared from bank portfolios, but the issue lives on in individual lawsuits by former CHF debtors suing their banks and the ongoing battle over the general principles that Croatian courts should follow to adjudicate these lawsuits consistently.

This article pursues two main objectives. First, it develops a holistic and relational account of the boom and crisis of CHF loans in Croatia by bringing together the various, so far relatively separate levels of analysis of foreign-currency (FX) housing lending in Eastern Europe that we discussed in the introduction: political economy; the roles of state institutions, political elites, banks and debtors’ movements; and debtors’ practices and experiences, further enhanced by auto-ethnography (since one of the authors participated in the main CHF debtors’ organization in 2011–2014). Second, the article connects the literature on Eastern European FX lending to the burgeoning scholarship on new social movements that challenge the financialization of housing and urban space. As we noted in the introduction to this Special Feature, the latter literature has so far focused on a small number of progressive movements in metropolitan Global North that contest housing financialization directly and often in an insurgent mode. The Croatian case shows that movements may address housing financialization more indirectly and selectively, employing a more ‘conservative’, technical and legalistic register and institutional strategies.

We employ the idea of moral economies of housing to make visible negotiations over housing in the Croatian CHF loans crisis and their embedment in political-economic processes. The concept of moral economy has been blurred by being used to refer to ‘alternative’, moralized economic spheres or simply as a suggestive metaphor for a study of morals. Anthropologists Palomera and Vetta (Citation2016) instead proposed to return to the historian E. P. Thompson’s original ‘radical’ formulation of the concept—one rooted in the materialist and socially progressive analytical tradition of Marxian political economy. In this perspective, moral economies are understood as historically and socially situated fields of norms, meanings and practices that ‘metabolize’ structural inequalities generated by particular forms of capital accumulation and state regulation (414). Building on this conceptualization, Alexander, Bruun, and Koch (Citation2017) developed the notion of moral economies of housing as a heuristic device for the anthropological study of struggles over housing. This is an arena in which real and imagined communities of families, households and nations engage with state, market and civil society actors seen as responsible for housing provision based on reciprocal obligations of citizenship (128–129). Since various communities hold different conceptions of such obligations, multiple moral economies of housing intersect (124).

In what follows, we build on these arguments to explore how political and financial elites and the movement of Croatian CHF debtors engaged in struggles over regulation of housing finance and how this affected wider moral economies of housing in post-boom Croatia.Footnote3 Regarding the latter aspect, we focus on the ways in which the struggles over CHF loans impacted state housing policies and hegemonic public discourse about housing in Croatia—dominant ideas, tropes and narratives on the subject that constrain possibilities of articulating alternatives (e.g. Lewis Citation2016, 422). We will argue that although the properties of their loans made CHF debtors by far the most vulnerable group of mortgagors, their opponents from the financial industry, politics and the media consistently represented them as well-off elites and therefore not worthy of assistance. To counter such stereotypes and accusations that their issues were due to their own financial illiteracy and irresponsibility, the movement of CHF debtors chose to focus on proving the illegal nature of the loans in courts and criticize them in legalistic and technical rather than openly political registers. This was also in line with their subject position of distressed mortgagors who sought to escape their own predatory debts and retain homeownership rather than reform the housing system as a whole. Even then, their legal victories and interventions in the public discourse, both of which won them substantial public sympathy, contributed to a slow and gentle shift in the Croatian politics of housing towards a recognition of the problematic aspects of super-homeownership and housing financialization as well as calls for, and modest early signs of, a reorientation of housing policy.

Our argument is developed as follows. Following this introduction, the second section describes the housing provision regime in Croatia and its key transformations since the 1970s, highlighting the increasing dominance of homeownership and marketized and financialized provision. The third section places CHF lending in the context of the 2000s boom and describes the socio-demographic profile of Swiss franc debtors. This is followed by the main empirical section with four subsections that trace the unfolding of the CHF loans crisis chronologically. The last section before the conclusion describes relevant policy and political developments after the 2015 conversion of Swiss franc loans. Our conclusion summarizes the argument and considers the impact of the CHF loans crisis on the moral economies of housing in Croatia.

Housing regime and inequalities in Croatia

This section situates the period of housing financialization within the long-term development of the Croatian housing regime. The rationale for this contextualization is twofold. First, inasmuch as moral economies of housing are embedded in political economies, discourses on debt and indebtedness need to be studied in a close relation to material processes and structures of housing provision and inequalities they generate. Second, this helps nuance the argument that peripheral financialization in Eastern Europe has been ‘mass-based’ (Becker et al. Citation2010, 242). In fact, the developmental trajectory of the Croatian housing regime has contributed to a concentration of housing debt in a distinct—young, urban and rather affluent—subsection of the society. This had significant implications for the politics of housing financialization.

Building on and slightly revising the periodization presented in Rodik, Matković, and Pandžić (Citation2019), we identify five periods in the development of the housing regime since the 1970s and summarize their key features in . The overall drift is from a late socialist housing regime with a mix of public and familial self-provisioning to a ‘super-homeownership’ regime that is characterized by a strong familialism, an increasing role of market-based and financialized provision, and a declining relevance of public housing. In hegemonic discourse on housing, the latter was increasingly framed as socialist legacy, while homeownership was preferred since it was aligned with individualistic approach to ownership and the transition to capitalist society.

Table 1: Transformations of Croatia’s housing provision regime since the 1970s. Data sources: Croatian Bureau of Statistics census data 1991, 2001 and 2011; Eurostat, dataset nasa_10_f

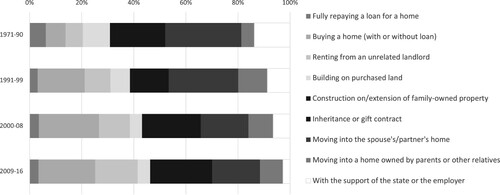

To explore intersections of the successive housing regimes and individual housing transitions, Rodik, Matković, and Pandžić (Citation2019) asked survey respondents to list retrospectively their housing tenures and the means of attaining them (that is, housing transitions from one tenure to another). The authors then grouped housing transitions as ‘market-based’, ‘familial’ or ‘publicly supported’, referring to their underlying social institutions. The overall pattern is one of a lasting predominance of familial housing transitions, a growing share of market-based transitions, and a decline of publicly supported transitions to marginal levels (see ). At a more granular level, there has been an increase in transitions based on inheritance, housing purchase and renting since the 2000s.Footnote4 Though this is not visible from , it is important to note that since the early 2000s, contracting a housing loan was the main instrument of financing housing purchases (CNB Citation2009, 28).

Figure 1: Housing transitions in the four periods. Light grayscale = market-based, dark grayscale = familial, white = publicly supported. Source: Rodik, Matković, and Pandžić (Citation2019, 320).

Mortgage market expansion in the 2000s introduced significant new generational inequalities in housing ownership and affordability. By 2000, 90% of Croatian households were homeowners, which puts Croatia into the category of Eastern European ‘super-homeownership’ societies (Stephens, Lux, and Sunega Citation2015). While older generations had enjoyed more options for accessing housing and bought their apartments at discounted prices during the privatization wave of the 1990s, the generations of younger adults entering the housing market in the 2000s, unless they were lucky to be able to access housing through familial means (inheritance or moving in with a partner), had only two realistic options—renting privately or purchase on the housing market, most often debt-financed.Footnote5 The latter is generally recognized as by far the superior choice due to the limited supply, poor regulation and precarityFootnote6 of rentals, their high costs compared to typical mortgage installments, the economic and social benefits of property ownership, state policies subsidizing (mortgaged) homeownership, and other circumstances. The resulting concentration of mortgage debt in generations entering the housing market in the 2000s is visible in the socio-demographic profile of CHF mortgagors described in the next section.

Swiss franc loans and the mortgage boom and bust

Booms in housing debt and prices unfolded across most of Eastern Europe in the 2000s up to the GFC (Bohle Citation2018, 198–199). A fertile ground for these processes was prepared by the dominance of homeownership in these countries and government policies promoting the spread of mortgage finance (Tsenkova Citation2009). In Croatia, the government actively supported housing financialization through mortgage subsidies and tax breaks for mortgage holders (see ). Programmes of public housing construction remained limited in both scope and extent of decommodification and involved private banks as monopoly household creditors for particular projects. The Croatian mortgage market thus became ‘extremely more developed’ and substantially larger than anywhere else in the ‘Western Balkans’ (162).

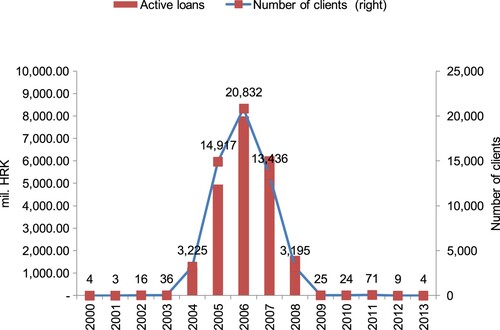

The characteristics of this transformation typify the peripheral financialization pattern discussed in the introduction to this special feature. After a fast privatization of Croatia’s banking sector (Ćetković Citation2011), the mostly foreign-owned banks imported large quantities of cheap capital, which they lent out at higher interest rates than in their home markets in European core economiesFootnote7 and with a preference for households over local companies. As in other Eastern European countries with lax regulatory regimes (Bohle Citation2018, 204–206), they regularly employed high-risk and predatory household lending practices. The most exploitative segment of predatory lending in Croatia were CHF loans, which made up nearly a half of total housing debt at the end of the boom (CNB Citation2014, 40). Almost 90% of CHF housing loans was issued in a very short period from 2005 to 2007 (see ). By the end of the boom, Croatia had one of the largest household debts and least affordable housing prices in Eastern Europe (Eurostat Citation2021; Vizek Citation2009, 283).

Figure 2: CHF housing loans by the year of issue and number of clients with CHF housing loans. Adapted from Figure 5 in CNB (Citation2015, 11).

CHF housing loans had multiple exploitative features. They combined foreign currency indexation with variable interest rates that banks were free to change essentially as they pleased up until January 2013 when new consumer protection legislation was enforced (see below). Before this, loan agreements did not link variable interest rates to any market parameters, leaving their adjustments for banks’ unilateral decisions (Rodik Citation2015, 65). This facilitated further exploitative practices. For example, ‘teaser’ interest rates on CHF loans, lower than those on euro or kuna loans, artificially boosted borrowers’ creditworthiness and justified approving larger CHF loans than they would be granted in other currencies—only to be increased soon after the contract was signed (Mikuš Citation2019, 307–308; Rodik Citation2019, 79). Such poorly conceived and untransparent creditworthiness checks enabled overindebtedness in the long term (Mikuš Citation2019, 308; Rodik Citation2019, 77, 100-102). Finally, before 2015, real estate valuation was completely unregulated and, in an apparent conflict of interest, banks calculated loan-to-value ratios based on their own or their sister companies’ real estate valuations. Misleading advertising and frontline marketing, informational asymmetry between banks and clients, the latter’s trust in banks as expert institutions (due to which borrowers of all social backgrounds assumed that contracts were broadly fair), and not least the industrial scale and routine nature of CHF loans contributed to their acceptance by borrowers.

Crucially, real estate market dynamics left many borrowers with few alternatives to accepting the banks’ terms if they wished to acquire housing. Homes in high-demand areas such as Zagreb and the Adriatic coast have become increasingly unaffordable in the course of the 2000s boom. This was reflected in a modest purchasing power of CHF loans—about 80% of CHF housing loans still being repaid in 2013 were originally worth less than 100,000 CHF, which would have been enough to buy only some 35 square metres in Zagreb at the average 2007 price (authors’ calculation based on data in CNB Citation2015, 10–11; Vizek Citation2009, 283). Many buyers sought to limit their expenditures by buying in peripheral areas of Zagreb, thereby pushing up prices in those areas as well and closing the gap between them and the central areas.

Statistics indicate that somewhat below 10% of households had housing loans (in any currency) at the end of the 2000s debt build-up. The debtors with housing loans tended to be urban, middle-aged, well-educated, with children, permanent employment contracts in the public sector and earning incomes above national average (Rodik Citation2019, 52–54). The spatial distribution of household debt reflected the geography of uneven socio-economic development in Croatia as measured by the official county development index. More developed areas had higher levels of household indebtedness, with an especially prominent concentration of household debt in general and housing debt in particular in Zagreb (Krišto and Tuškan Citation2016). Socio-demographics of households with CHF mortgages mostly resemble those of other mortgagors (Rodik Citation2019, 110–111) and their spatial distribution matched the general mortgagor population. Their average income was above the Croatian average, but slightly lower than that of households with euro or kuna mortgages, which is consistent with the more relaxed lending standards for CHF loans. Their socio-demographic profile should be interpreted within the broader context of housing tenure structure and inequalities in Croatia outlined in the previous section. It was disproportionately members of young and lower-middle-age generations who, under the conditions of Croatia’s super-homeownership housing regime, found themselves practically compelled to take out housing loans in the boom period—that is, if they could qualify for one. The fact that they have done so in the heyday of the unprecedented transformation of the Croatian financial sector exposed them to unforeseen vulnerabilities.

The crisis of CHF loans: actors, events, discourses

Beginnings of the Franc Association, 2009–2011

After the GFC, Croatia’s economy sank into a long recession in 2009–2015. As elsewhere in the same period, the recession manifested in job losses, falling incomes, mortgage and housing bust, growing state debt, and austerity measures. The country entered the recession with some 73,000 CHF housing loans approved during the boom (CNB Citation2015, 10). These loans soon turned problematic as the franc appreciated against the Croatian kuna by some 40% in 2008–2011 and another 10% in January 2015 (7). The appreciation directly inflated outstanding principals and, augmented by the banks’ raises of interest rates, increased monthly repayment installments by a half on average (Rodik Citation2015, 66). Furthermore, the option of unilateral interest rate modification allowed banks to raise active interest rates for long periods of time even as CHF interbank interest rates were falling (66).

During the recession, the share of non-performing loans in bank loans to households increased from 4% in 2008 to the peak of more than 12% in 2015 (CNB Citation2009, 45, Citation2017, 39). As a result, debt enforcement proceedings against physical persons became much more common. The number of people subjected to ‘enforcement over monetary assets’, which means that all deposits on their bank accounts except a legally protected minimum were seized for repayment, shot up from about 78,000 in January 2011 to about 331,000 in March 2017—an alarming 8% of the population. The number of foreclosures of houses and apartments grew from about a hundred in 2006 to more than 3,000 in 2014 (Rodik Citation2019, 148–149).

The exposure of indebted households to recession shocks was highly uneven. As already mentioned, those with CHF mortgages were exposed to much larger shocks than those with euro or kuna mortgages. The difference between CHF and euro mortgages was due to the fact that the CHF-HRK exchange rate is a floating one while the EUR-HRK rate was kept practically fixed by the central bank from the 1990s up until euro adoption in 2023. While euro and kuna mortgagors were also affected by an increased repayment burden, this was mostly due to a drop in their incomes. CHF debtors experienced reduced incomes as well as much larger surges of repayment (Rodik Citation2015, 70, Citation2019, 133–134). Bankers and public officials sought to diminish the extent of these shocks, most often by arguing that CHF debtors had had a lighter repayment burden before the bust and that the shocks might well even out over the entire amortization period. The first government publications that disclosed official statistics on CHF loans were published only in 2015. It was the debtors themselves who organized and started collecting evidence and campaigning from below.

From the outset, the debtors’ movement has been developing in a close relationship with the events on the global FX market, as EUR-CHF fluctuations translated to CHF-HRK FX rates. The CHF-HRK rate first started to grow significantly in 2008, followed by some stagnation in 2009. It resumed fast growth in fall 2009 and rose permanently above 1 CHF = 5 HRK in spring 2010. After a period of alternating increases and drops in the second half of 2010 and the first quarter of 2011, another sharp increase of about 17% ensued from April to August 2011, peaking at 7.16 HRK on 11 August.Footnote8 Against this backdrop, a group of CHF debtors established a civic association called Franc Association (Udruga Franak, FA from now on)Footnote9 in July 2011. After debating their options, the founding members decided on two things. First, the FA would aim at a broad membership base and a crowdfunding model to be independent. Second, it would file a class-action lawsuit against the banks. The first Statute, adopted in July 2011, defined the interests of FX debtors and more broadly regulation of consumer financial services as the FA’s focus. This orientation was reconfirmed by successive statutes adopted in November 2011, 2014, 2015 and 2017 and by the 2013 Strategic Directions of Action. These documents did not make any references to issues of housing policy and housing provision or leftist critiques of financialized capitalism of the kind formulated by the more visible Western European and North American movements.

Most founding members had a middle-class professional background and no experience in finance or economics. There were notable exceptions cutting both ways: several trained economists joined early on while the first FA president was a kindergarten janitor. Moreover, from the very beginning, leaders were aware of the heterogeneity of the group in terms of social backgrounds, worldviews and political inclinations. They chose to put their ideological disagreements aside for the sake of common interests and frame the problem of CHF loans in legal and moral rather than explicitly political terms. This strategy reflected also their awareness of the long-standing marginalization of economic leftism in Croatia and a wish to avoid right-wing populist and nationalist frameworks promoted by some members. This deliberately depoliticized approach would have been largely observed in later years, although political tensions occasionally resurfaced.

As the debtors were starting to organize and publicly voice the issue and the FX rate continued to rise, the government started to discuss the situation with the Croatian National Bank (CNB) and banks. This resulted in two official agreements between banks and the government in summer 2011 that were supposed to relieve CHF debtors’ repayment burden. However, the measures introduced—essentially expanded options for individual mortgage modifications—came short of a meaningful solution and very few debtors used them. The media was taking an increasing interest and all actors started articulating their positions. The FA’s entry into the public debate radically transformed its terms.

Public discourses on CHF loans in summer 2011

The debate in summer 2011 revolved around the foreign-currency aspect of the CHF loans issue. At that stage, the focus was not on housing; the CNB governor Željko Rohatinski explicitly argued that those with CHF housing and car loans shared the ‘same problem’. Initially, only bankers, politicians and frequent media interlocutors presented as ‘economic/financial experts’Footnote10 were involved in the debate while debtors were its passive objects. The hegemonic discourse of elites portrayed franc debtors as either victims of their own irresponsibility or as speculators who ‘gambled on the currency market’. The main implication was the same—that they should not expect the state to save them when they had to pay the price for their carelessness or speculation. One ‘economic expert’ argued that ‘it is like when you buy shares; why should the state protect the losers?’ (t-portal, June 2, 2011). Such arguments were often coupled with admonishments that policy should not ‘privilege’ franc debtors over euro and kuna debtors. Some officials went so far as to suggest that appropriate state intervention should be disciplinary: the irresponsible CHF debtors should have their loans converted to euros but ‘pay one percent higher interest rate than those who had euro loans from the beginning’ (Jutarnji list, August 9, 2011).

The banks, represented by the Croatian Banking Association (HUB), had a slightly different position. Likewise refusing that CHF debtors were victims of any wrongdoing, they nevertheless argued that they needed assistance since their insolvency was becoming a ‘social problem’ (socijalni problem)—a Croatian syntagm that frames the issue as one of poverty and welfare assistance. Faced with growing holdings of bad loans, the banks were essentially calling on the state to restore the solvency of their debtors. They advocated for a targeted solution based on what they labelled as ‘social criteria’ or ‘debtors’ profile’, arguing specifically that government intervention should only apply to those with CHF loans of up to €100,000 (Jutarnji list, August 9, 2011). At the same time, they cautioned that assistance for CHF debtors ‘could put those who took euro-indexed loans at a disadvantage’ and that excessive intervention might ‘result in collateral damage to the banking system that would exceed the problems being solved’ (HUB press release, August 4, 2011).

It was against this backdrop that the FA entered the public sphere and started developing a counter-discourse from the debtors’ perspective, thereby challenging the hegemonic discourse of elites and establishing the debtors as active participants in the debate. The association outlined its key arguments and demands in its first press release (August 9, 2011). Its argumentation was predominantly formulated in economic, technical and legalistic registers, with calls on the banks to obey the law. However, the press release also noted that ‘citizens took out housing loans with a purpose of solving their housing question’ and that the situation had become a ‘first-rate economic, social and political problem’ and a ‘question of national interest’. This was a wider and more political definition of the issue than the banks’ ‘social problem’ as it encompassed the threats that predatory loans posed to human and consumer rights and their impact on the national economy. As part of this expanded problematization, the argument we label ‘housing credit as an especially sensitive type of credit’ stressed the social and political significance of housing debt derived from its role as a means of satisfying the universal and basic need for housing. Still, this was not the dominant line of argumentation, and foreclosures were mentioned only in the context of the broader debt enforcement issue.

Ultimately, the FA press release called for an intervention that would not differentiate between debtors based on the loan purpose, claiming that all had been subjected to the same exploitative lending practices. Accordingly, none of the six demands articulated in the first press release focused explicitly on housing loans. The list started with a demand for lower interest rates on all FX loans ‘notwithstanding the loan purpose or currency’. The second demand called for a temporary suspension of debt enforcement proceedings (concerning ‘salaries, flats etc’). The rest of the demands called for limiting the use of FX clauses in loan agreements, conversion of all FX loans to the kuna, transparency of banks’ franc liabilities, transparency of interest rate changes, and a ban on early repayment charges. Crucially, none of these demands or those the FA formulated later, such as for damage compensations, necessitated any public spending. The association always advocated for solutions to be paid for by the banks that had enriched themselves illegally, thereby avoiding any new injustices against people with other kinds of loans or without any loans at all.

Growing pressure and first legislative interventions, 2012–2013

Between summer 2011 and autumn 2012, the FA was primarily concerned with preparing for the class action lawsuit and mobilizing its wider membership. The leadership conducted extensive in-house research covering the legal, financial and social aspects of the franc loans issue to develop the class action suit against the eight largest Croatian banks (all foreign-owned), which was filed in April 2012. The main focus up until autumn 2012 continued to be on unfair lending practices and the impact of the loans crisis on debtors. In this period, the debtors themselves started deconstructing the banks’ techniques of profit extraction, which was vital for their self-empowerment. FA members compared the contractual definitions and movements of their interest rates, repayment plans, other contract terms, or information obtained from personal bankers, noticing a lot of arbitrariness, unfairness and outright errors. The banks’ aura of professionality, trustworthiness and infallibility faded. The debtors started writing complaint letters to their banks and the CNB’s Consumer Protection Monitoring Office en masse. A growing sense of outrage fuelled the membership mobilization and peer support played an important role in overcoming the feelings of stigmatization, guilt and isolation. By the end of 2012, the FA attracted a membership of more than 5,000Footnote11 and secured necessary funding by collecting small annual membership fees (ca. €4).

In autumn 2012, the FA entered the debate on the government’s draft of the first law amending the Consumer Credit Act (CCA1 from now on). The FA articulated three key demands—conversion of CHF loans to the euro, introduction of transparent interest-rate formulas (see below), and adoption of a personal bankruptcy law (FA press release, October 9, 2012)—alongside writing open letters and organizing events. For the first time, a senior FA member argued in an interview that franc housing loans were a ‘particularly sensitive category of credit’ since the debtors took them out to satisfy their existential need for housing, in other words to ‘solve their housing question’ (net.hr, December 6, 2012). This ‘sensitive’ nature of housing debt morally justified the FA’s calls for special regulatory rules on housing loans. By that time (October 2012), the share of housing loans in outstanding CHF loans exceeded 80%,Footnote12 which might in part also explain the increased FA’s focus on this category of loans. Although it never became the primary concern, the FA also at times indirectly critiqued the current housing regime by arguing that people were compelled to take out housing loans because public policies did not provide alternatives to homeownership. Diverging from the morally grounded claim that housing debt is ‘particularly sensitive’, this argument of a ‘lack of alternatives to homeownership’ was based on structural and material conditions of housing provision and the first-hand experiences of homebuyers during the boom that it shaped.

The main change introduced by the CCA1 was forcing the banks to adopt transparent variable interest rate formulas, including in existing FX loan contracts. The banks had to define two components of the interest rate: a fixed margin and a relevant variable parameter, such as LIBOR or EURIBOR. In a parliament debate in September 2012, representatives of the coalition government led by the Social Democratic Party (SDP) justified the need for these amendments by ‘disadvantageous lending conditions that recently brought citizens into a desperate situation: high interest rates, easy adjusting of interest rates as well as abuses of some provisions of the Consumer Credit Act’. The government thus essentially validated the FA’s arguments about the unfair construction and manipulation of interest rates. At the same time, it set 1m kuna (ca. €135,000) as the maximum principal size for housing loans to which CCA1 provisions would apply. Larger housing loans would not be subject to this new consumer lending regulation on an assumption that they were used for profit-oriented investments. This was consistent with the aforementioned banks’ calls for ‘social criteria’ and, more implicitly, the elite discourse about CHF debtors as ‘speculators’. The FA, for its part, disputed the 1m kuna cap and argued that debtors were forced to take loans of such sizes by the 2000s housing bubble.

In addition, the FA pointed also to the issue of what we label a ‘housing debt trap’. As housing prices dipped and CHF-indexed principals soared, many debtors found themselves in situations of negative equity. Moreover, the Croatian Debt Enforcement Act did not allow for a repayment of mortgage debt by transferring the ownership of the real estate collateral. If the current market value of a repossessed property was less than the outstanding debt, the bank claimed the balance from the debtor. For that reason, the FA demanded an urgent passing of a personal bankruptcy law that would enable defaulted debtors to claim insolvency and have a part of their debt written off.

CCA1 was adopted and enforced from January 2013 with the million kuna cap. The banks subverted the main expected impact of the law on existing FX housing loans—introduction of fair and transparent interest rates—by deciding on both the fixed and the variable component of interest rates as it suited them and such that rates could only get higher in the future. CHF debtors thus did not see a drop in their interest rates and repayment because of the law coming into force. The FA continued its campaign and in early 2013 the government announced more substantial interventions were under way in the form of the second law amending the Consumer Credit Act (CCA2). In the spring, the FA submitted a petition with over 15,000 signatures to the government, the speakers of the parliament and the CNB along with the three demands formulated in October 2012. The July 2013 verdict of the first-level court (Commercial Court in Zagreb) in the class action lawsuit was in favour of debtors and this raised the stakes, even though the banks appealed the verdict. Negotiations between the Ministry of Finance and the banks were taking place during the summer and autumn of 2013 as the government looked for a solution acceptable to the banks. At the same time, the FA continued expanding its membership and achieved huge media visibility.

The parliament debates on CCA2 (in September and October 2013) were extensive and several interventions evoked the problematic of housing lending and housing policy. Politicians of the ruling coalition and the opposition Labour Party picked up the FA’s argumentation about housing loans as particularly socially sensitive. The SDP finance minister vaguely referred to government plans to take over unsold flats from construction companies and rent them out to citizens at affordable rates. Ultimately, however, the debate naturalized the homeownership model and housing finance in two ways: by assuming that bank funding and ‘market interests’, if sometimes problematic, were unavoidable components of Croatia’s super-homeownership regime, and by culturalizing the latter through what we call the ‘fetish for real estate’ argument. This label paraphrases the statement of the investor and financial analyst Nenad Bakić who ‘explained’ the dominance of homeownership as the result of Croatians’ supposed cultural ‘fetish for real estate’ as well as, historically incorrectly, a ‘socialist legacy’ (Eclectica.hr, January 20, 2015).

CCA2, adopted in late 2013 and in force from February 2014, alleviated the repayment burden of CHF debtors by capping their active interest rates at 3.23% for as long as the CHF-HRK exchange rate was at least 20% higher than at the time of contracting. This decreased the debtors’ monthly installments significantly (CNB Citation2015, 14) as interest rates on housing loans previously climbed as high as 7% in some banks. While CCA2 did not have a major impact on housing lending in general, it represented the first significant intervention in existing franc loan contracts.

Escalation and conversion, 2014–2015

In July 2014, the High Commercial Court in Zagreb (the first appeal court) delivered the verdict in the class action lawsuit that was less in favour of debtors than the first verdict in 2013. It became clear to the FA that litigation was too slow of a path and that a collective solution through the adoption of a new law was needed.Footnote13 Events in 2015, especially the drastic appreciation of the franc in January, refocused attention mostly on the FX aspect of franc loans. In January 2015, in response to the sudden franc appreciation after the SNB removed the 1 EUR = 1.20 CHF FX cap, the government adopted the third law amending the Consumer Credit Act (CCA3), which froze the exchange rate on franc loans for a year. The parliament discussion of CCA3 engaged with housing issues in limited and generic ways. The argument about housing loans being ‘sensitive’ was presented in the form of a recognition that franc debtors faced the threat of repossessions. MPs further referenced it in calls to distinguish debtors who took franc loans to buy modest homes from other cases, evoking again the idea that any assistance of franc debtors should be limited to those meeting ‘social criteria’. In doing so, MPs accepted the argument about housing loans being ‘sensitive’ in principle while limiting its validity to a subset of individual cases.

The FA continued to push for a permanent solution to the problems of franc debtors. In 2015, it organized a series of six protests (Dolenec, Kralj, and Balković Citation2021, 8), the largest of which, in Zagreb in April, was attended by some 20,000 people. This corresponded to the number of members reached already the previous summer (FA press release, August 31, 2014). In fall 2015, after this impressive protest wave and in the run-up to general elections, the government adopted the fourth law amending the Consumer Credit Act (CCA4). Such pre-election mobilizations and government concessions are a familiar feature of Croatian political culture. The FA was involved in the drafting of the law. Known informally as the ‘law on conversion’, CCA4 introduced the right of franc debtors to convert their outstanding debts to the euro. Specifically, each loan was to be recalculated as if it was an EUR-indexed loan issued in line with the terms and conditions of each given bank from the beginning. The difference between the assumed repayment for this EUR-indexed loan (lower) and the incurred repayment for the CHF-indexed loan (higher) was then calculated and deduced from the outstanding principal and future repayment.

The discussion of the link with housing re-emerged somewhat more prominently in this context. In a document explaining the rationale of the proposed amendments, the government recognized the issue of housing debt trap, noting that the drop in housing prices precluded franc debtors from settling their outstanding debts by selling their property (GRC Citation2015, 2–3). In the discussion, MPs reproduced the argument about the sensitivity of housing credit in implicit and conditional ways. They generally accepted the assumption that franc debtors who bought their homes deserved help. At the same time, several MPs from across the political spectrum suggested that some bought luxurious homes or even yachts or built real estate for sale, thereby keeping the ‘speculators’ narrative alive.

Despite the rhetoric critical of the debt boom and bust, the government of the SDP-led coalition (late 2011—early 2016) failed to deliver any significant shift in housing policy. In 2011–2012, the government implemented two cycles of a mortgage subsidy scheme, subsequently discontinued. Since 2013, it has been implementing POS + (ongoing), a revamped POS programme (see ) that could be interpreted as an attempt to salvage the financialized homeownership model by stimulating sales of unsold newly-built properties through a combination of mortgage subsidies and price discounts. Nevertheless, interest in the programme has been very limited. The State-Subsidized Rental Housing Programme (PON, ongoing), which offers unsold POS flats for renting or rent-to-buy instead of purchase, was initiated in 2015. However, it has remained limited to several hundred apartments. In 2017, a new government led by the right-wing Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), which has remained in power until present, adopted the Act on Housing Loan Subsidies (AHLS) to introduce a refurbished programme of mortgage loan subsidies, thereby confirming its orientation to owner-occupation and financialized provision.

Post-conversion developments, 2016–2023

After the conversion, the FA expanded its presence to party politics. In 2016 snap elections, several FA members ran on a candidate list led by Human Shield (Živi zid), an anti-establishment party that had first become visible as an activist group organizing anti-eviction sit-ins (Dolenec, Kralj, and Balković Citation2021, 8–9). The association’s president Goran Aleksić won one seat in the parliament and subsequently broke off from Human Shield and set up a new FA-controlled party. However, the latter failed to establish itself as a standard (rather than single-issue) party and lost its parliamentary representation in 2020 (Dolenec, Kralj, and Balković Citation2021, 9–10). Since then, the FA focuses on supporting the lawsuits of CHF debtors suing their banks for full compensation of excess repayment and lobbying for favourable standards of their adjudication by the Croatian judiciary, which are subject of ongoing Supreme Court proceedings at the time of final revisions of this article (February 2023).

The passing of several laws on housing finance in 2017 occasioned a particularly intense and elaborate engagement (by the standards of Croatian politics) with wider issues of housing provision and policy. The Act on Consumer Housing Loans (ACHL) implemented the EU Mortgage Credit Directive into Croatian legislation and was the first Croatian law to regulate housing credit specifically. The law did not go beyond this narrow focus. The second relevant 2017 law was amendments of the Debt Enforcement Act (DEA-17). These amendments limited repossessions and improved the debtor’s status in such proceedings in both future and existing credit/debt relationships, including CHF loans. Finally, the aforementioned AHLS introduced a new housing loan subsidy scheme.

The FA’s approach to the first two of these laws illustrated its continued focus on regulation of consumer lending and a limited engagement with housing issues through the concern with repossessions, which it shared with Human Shield. Concerning the DEA-17, the ruling HDZ-led coalition accepted the FA’s proposal to ban repossessions of the ‘only real estate’ (i.e. owner-occupied home whose owners did not own another home) due to debts other than a mortgage loan for which the property was collateral. In addition, the FA proposed four amendments that would also ban repossessions due to mortgages in certain situations (including when the mortgage contract specified the variable interest rate in an illegal manner, which was generally the case with CHF loans) but these were not accepted (FA press release June 27, 2017).

Discussion of housing provision and policy became particularly elaborate in the context of the passing of the AHLS. The explanatory part of the draft law framed it as a demographic policy rather than a housing policy. It noted emigration from Croatia, population ageing, and degradation and depopulation of inner cities as trends that could be supposedly attributed also to the high cost of housing credit. The document identified subsidies for bank loans for purchase or construction of privately owned housing as the solution without mentioning any alternative models of housing provision. However, the parliament discussion of the draft law in April 2017 featured references to alternative housing models and the experience with franc loans. MP and erstwhile SDP finance minister Boris Lalovac noted how his government had to intervene in franc loans and that this revealed the unsustainability of housing finance and opened the ‘question of ownership’ as the dominant tenure. The liberal Croatian People’s Party MP Anka Mrak-Taritaš, formerly the construction minister in the SDP-led government and the key person behind the PON rental programme, questioned whether this was the right moment for another ownership-oriented policy. She argued that young people in particular were often not keen on buying.

More recently, alternative approaches to housing policy featured prominently in the 2021 local election programme and campaign of the green-left coalition Možemo! (We Can!). Its programme for Zagreb, where it won the elections at all levels, included measures such as expansion, better usage and participatory governance of public rental housing stock; ending the privatization of the former; upgrading housing assistance for the poor; and incentives for housing cooperatives and affordable private rentals. The coalition’s housing policy proposals drew mostly on the work of the Zagreb-based NGO Pravo na grad (Right to the City), to which it also had close social connections. Pravo na grad has initially focused on struggles against the privatization of public urban space but gradually expanded its attention also to the issues of housing financialization and affordability. In her landmark work on housing policy, the leading expert of Pravo na grad Iva Marčetić (2020, 12) acknowledged the activities of the FA as extremely important in countering (with a partial success) the dominant narrative about mortgagor overindebtedness as the result of mortgagors’ own irresponsibility and their ‘fetish for real estate’, instead directing attention to the role of lenders and the state in producing the debt crisis. This represents one concrete channel through which the CHF debtors’ movement contributed to a denaturalization of financialized homeownership and search for alternatives.

In practice, since 2020, public debate and policies on housing both in Zagreb and nationally have been dominated by the (very slow) renovation of the housing stock damaged by a series of earthquakes that year. Even then, there have been some tentative signs of shifts in housing policy. The new Zagreb city government limited further privatization of city-owned apartments to exceptional cases, such as when sitting tenants acquired a right to it based on national legislation (Zagreb je naš! press release, May 17, 2022). The city has plans for the construction of public rental apartments in various stages of progress, including in central locations (poslovni.hr, May 29, 2022). Most recently, the Minister of Construction, Physical Planning and State Property Branko Bačić signaled that the government is considering a general overhaul of the housing policy. This could include modifications or scrapping of the costly mortgage subsidy scheme (criticised due to its documented push-up effect on housing prices) and subsidized construction of public rental apartments instead of apartments earmarked for owner-occupation (N1 TV (Zagreb) main news show, February 25, 2023).

Conclusions: moral economies and material structures of housing provision after the loans crisis

This paper has shown that the crisis of CHF housing loans has led to a politicization of housing lending in Croatia mainly through the bottom-up mobilization and contestational practices of debtors. The radical concept of moral economy helps make sense of the key characteristics of this crisis: its embedment in specific forms of political economy and the structural inequalities that they generate; its articulation in an often moral, technical and legalistic rather than explicitly political register; and its relational and interactive character, reflected in the alternation of struggles, negotiations and alliances between elites and popular groups. To this must be added the structurally constrained, but never fully predetermined strategic decisions made by key actors, which channelled the crisis in partially contingent ways. Taken together, these considerations help understand the forms and outcomes of the contestations of Croatian CHF loans.

The crisis was closely embedded in Croatia’s super-homeownership housing regime and its distinctively peripheral and predatory financialization. During the 1990s, the very idea of public housing provision was abandoned, with an exception of several limited programmes targeting very particular groups (e.g. war veterans). Homeownership has emerged as the most socially and politically validated housing tenure since it was part of the collective movement toward an idealized capitalist prosperity and, at an individual level, the sign of one’s successful middle-class status. Its dominance further derived its legitimacy from the widely shared common-sense generalization about homeownership as the culturally preferred tenure in Croatia. During the crisis, elite actors sought to preserve this hegemonic discourse. They depicted CHF debtors as buying into this ‘obsession with ownership’ while ‘gambling’ on the FX market. They evoked these arguments as they found convenient and without aligning them into a coherent interpretive framework, following the general rationale of individualizing responsibility and attaching blame to debtors. In their (apparently) most accommodative, financial and political elites conceded the need for some assistance to select debtors based on ‘social criteria’, thereby framing the loans crisis as an issue of welfare rather than legal and social justice.

This material and ideological context was not conducive to the emergence of radical movements directly challenging housing financialization. Acute material hardship of FX mortgage repayments directed activists toward the contestation of specific predatory lending practices rather than housing financialization as such. Related to that, the FA’s plan to sue the banks oriented its discourse and practices towards law, in particular, consumer protection law and litigation. The emphasis on illegal and unfair lending practices went hand in hand with the opposition to the efforts to differentiate between debtors according to ‘social criteria’. The FA’s preference for expert-like, legal and financial discourse, and avoidance of more radical and openly political discourses, was also motivated by its need to overcome internal ideological differences and be recognized as a knowledgeable subject in the debate dominated by ‘experts’. Litigation and the focus on the technical aspect of predatory lending that supported the litigation claims figured as an important tool for another reason. While moral arguments foregrounded predatory lending practices as unsustainable and illegitimate, the legal and technical arguments supported the argument that they were illegal.Footnote14 This proved as a powerful strategy for building up the political pressure. Given the constraints of the socio-political context, explicit leftist argumentation and systemic-level critique of financialization would not be as powerful either in terms of membership mobilization or political pressure. At the same time, this prevented the drift towards right-wing articulation of the issue of the kind seen in Hungary (this Special Feature).

The crisis of CHF loans also impacted the wider moral economies of housing in Croatia. First, it contributed to a greater public recognition of the failures of the leveraged homeownership model: the predatory lending practices, the excessive risks borne by debtors, and the broader issue of housing unaffordability. Materially, this has been reflected in a stronger regulation of housing finance and the elimination of the particularly exploitative and predatory practices. The responses of banks and debtors were also significant: new CHF lending ceased and, especially from 2016 to the euro adoption in 2023, kuna borrowing was becoming increasingly popular. Second, the CHF loans crisis has contributed to denaturalization of the financialized homeownership model and growing calls for alternative forms of housing provision in political discourse, especially regulated renting with varying degrees of decommodification. While the government mostly continued to promote the existing housing regime and reproduce naturalizing narratives about homeownership, we also noted some recent tentative signs of an incipient shift in housing policy in Zagreb and signals of a possible turn towards supporting public rental housing provision at the state level. Nevertheless, only a large-scale boost of public rental provision would open the door to a more diversified housing regime. Beyond that, we believe it would take a more radical shift towards decommodification of housing at an international scale (at least EU scale in Croatia’s case) to offset financialization tendencies and bring about socio-economically just housing systems.

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewer, the journal editors, Agnes Gagyi, and participants in the February 2020 workshop ‘Foreign-Currency Housing Loans in Eastern Europe: Crises, Tensions and Struggles’ in Zagreb for their helpful feedback to earlier versions of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Petra Rodik

Petra Rodik (independent researcher) is a sociologist with research interests in financialization of housing, household debt, housing inequalities and advances in research methods. Email: [email protected]

Marek Mikuš

Marek Mikuš (Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology) is a social anthropologist studying civil society, the state and finance in East-Central and South East Europe. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 Breakdown of CHF-indexed loans, time series provided to the authors by the Croatian National Bank on 6 March 2018.

2 Croatia adopted the euro as its official currency on 1 January 2023 and phased out the kuna shortly thereafter. The conversion rate was fixed at 1 € = 7.5345 HRK.

3 Mislav Žitko (Citation2018) has already employed a moral economy framework to analyse Eastern European CHF loans crises. However, his reading of the concept and conclusions diverge from our own.

4 The ‘buying’ category aggregates housing purchases with and without a loan.

5 The only remaining alternative is to give up (temporarily or permanently) on establishing an independent household altogether and stay in the parental household. Croatians have been leaving the parental household at the highest average age in the EU for most of the past 20 years (Eurostat dataset YTH_DEMO_030), which again points to the unaffordability of housing.

6 The private rental market at the time was almost completely unregulated and informal. For example, most renters had no rental contracts and landlords routinely prevented them from registering their residence at the address to protect their tax avoidance schemes. The situation of private renters has improved somehwat since then but remains precarious (Marčetić Citation2021, 163–169).

7 In early 2003, nominal interest rates on FX-indexed housing loans in Croatia were almost 2 percentage points higher than those in eurozone countries (CNB Citation2009, 26).

8 In September 2011, the Swiss National Bank (SNB) introduced a 1 EUR = 1.20 CHF FX cap. This led to a slight decrease in the CHF-HRK rate.

9 While formally based in Zagreb, the FA had an active membership base from all across Croatia from the start. Most founding members first met in the popular Croatian internet forum Forum.hr under the discussion topic dedicated to CHF loans. They did not have any previous common history of organizing and started building the organization from scratch.

10 We employ the quotation marks to problematize the way in which this label stresses the purported technical expertise of those recognized as such. In particular, we show below that the arguments of ‘economic/financial experts’ about the CHF loan issue often turned out to be primarily moral or ideological in nature on closer inspection.

11 This figure includes all formal FA members. The organization distinguished between ‘active’ and ‘supporting’ members depending on whether they actively participated in campaigning and other FA activities or not. Active members had more responsibilities as well as rights, such as to participate in decision-making.

12 Breakdown of CHF-indexed loans.

13 Protracted appeal proceedings ensued and the class action only really ended in February 2021 with a Constitutional Court ruling that upheld a previous Supreme Court ruling confirming the 2013 verdict in full.

14 Here we are loosely borrowing from the distinction of debt types used in the sovereign debt context (TCPD Citation2015).

References

- Alexander, Catherine, Maja Hojer Bruun, and Insa Koch. 2017. “Political Economy Comes Home: On the Moral Economies of Housing .” Critique of Anthropology 38 (2): 121–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X18758871.

- Becker, Joachim, Johannes Jäger, Bernhard Leubolt, and Rudy Weissenbacher. 2010. “Peripheral Financialization and Vulnerability to Crisis: A Regulationist Perspective .” Competition & Change 14 (3-4): 225–247. https://doi.org/10.1179/102452910X12837703615337.

- Bohle, Dorothee. 2018. “Mortgaging Europe’s Periphery .” Studies in Comparative International Development 53 (2): 196–2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-018-9260-7.

- Brown, Martin, Marcel Peter, and Simon Wehrmüller. 2009. “Swiss Franc Lending in Europe .” Aussenwirtschaft 64 (2): 167–181.

- Ćetković, Predrag. 2011. “Credit Growth and Instability in Balkan Countries: The Role of Foreign Banks”. Research on Money and Finance Discussion Paper 27. http://ideas.repec.org/p/rmf/dpaper/27.html.

- CNB. 2009. Financial Stability 2. Zagreb: Croatian National Bank .

- CNB. 2014. Financial Stability 13. Zagreb: Croatian National Bank .

- CNB. 2015. Izvješće o problematici zaduženja građana kreditima u švicarskim francima i prijedlozima mjera za olakšavanje pozicije dužnika u švicarskim francima temeljem zaključka Odbora za financije i državni proračun Hrvatskog sabora. Zagreb: Croatian National Bank. https://www.hnb.hr/documents/20182/447389/hp15092015_CHF.pdf/6e84815b-eb41-4315-96a2-9ecf5b8c6183.

- CNB. 2017. Financial Stability 18. Zagreb: Croatian National Bank .

- Dolenec, Danijela, Karlo Kralj, and Ana Balković. 2021. “Keeping a Roof Over Your Head: Housing and Anti-Debt Movements in Croatia and Serbia During the Great Recession .” East European Politics, https://doi.org/10.1080/21599165.2021.1937136.

- Eurostat. 2021. Private Sector Debt: Loans, by Sectors, Consolidated – % of GDP. Accessed June 7, 2021. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/view/NASA_10_F_BS.

- GRC. 2015. Prijedlog Zakona o izmjeni i dopunama Zakona o potrošačkom kreditiranju, s konačnim prijedlogom zakona. Zagreb: Government of the Republic of Croatia. https://www.sabor.hr/sites/default/files/uploads/sabor/2019-01-18/080849/PZ_899.pdf.

- Krišto, Jakša, and Branka Tuškan. 2016. “Karakteristike kreditne politike banaka po županijama u Republici Hrvatskoj .” Ekonomija 22 (2): 315–333.

- Lewis, David. 2016. “Blogging Zhanaozen: Hegemonic Discourse and Authoritarian Resilience in Kazakhstan .” Central Asian Survey 35 (3): 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1080/02634937.2016.1161902.

- Marčetić, Iva. 2021. Housing Policies in the Service of Social and Spatial (In)Equality. Zagreb: Pravo na grad .

- Mikuš, Marek. 2019. “Contesting Household Debt in Croatia: The Double Movement of Financialization and the Fetishism of Money in Eastern European Peripheries .” Dialectical Anthropology 43 (3): 295–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10624-019-09551-8.

- Palomera, Jaime, and Theodora Vetta. 2016. “Moral Economy: Rethinking a Radical Concept .” Anthropological Theory 16 (4): 413–432. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463499616678097.

- Rodik, Petra. 2015. “The Impact of the Swiss Franc Loans Crisis on Croatian Households.” In Social and Psychological Dimensions of Personal Debt and the Debt Industry, edited by Serdar M. Değirmencioğlu, and Carl Walker, 61–83. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan .

- Rodik, Petra. 2019. (Pre)zaduženi: Društveni aspekti zaduženosti kućanstava u Hrvatskoj. Zagreb: Naklada Jesenski i Turk .

- Rodik, Petra, Teo Matković, and Josip Pandžić. 2019. “Stambene karijere u Hrvatskoj: Od samoupravnog socijalizma do krize financijskog kapitalizma .” Revija za Sociologiju 49 (3): 319–348. https://doi.org/10.5613/rzs.49.3.1.

- Stephens, Mark, Martin Lux, and Petr Sunega. 2015. “Post-socialist Housing Systems in Europe: Housing Welfare Regimes by Default? ” Housing Studies 30 (8): 1210–1234. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673037.2015.1013090.

- TCPD. 2015. Preliminary Report. Truth Committee on Public Debt. https://www.cadtm.org/Preliminary-Report-of-the-Truth.

- Tsenkova, Sasha. 2009. Housing Policy Reforms in Post Socialist Europe: Lost in Transition. Heidelberg: Physica-Verlag .

- Vizek, Maruška. 2009. “Priuštivost stanovanja u Hrvatskoj i odabranim europskim zemljama .” Revija za Socijalnu Politiku 16 (3): 281–297. https://doi.org/10.3935/rsp.v16i3.809.

- Žitko, Mislav. 2018. “Governmentality Versus Moral Economy: Notes on the Debt Crisis .” Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research 31 (1): 68–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2018.1429897.