Abstract

Amid the redevelopment of Seattle’s Yesler Terrace, C. Davida Ingram wrote, ‘residents have made their lives possible in places where others only see the impossible.’ Thinking with Ingram, this article asks ‘what goes unnoticed’ in the reproduction of the built environment along Yesler Way over time. In contrast to its plats—the plans and designs undergirding the colonization of sdzídzəlʔalič, renewal of Profanity Hill, and redevelopment of Yesler Terrace—I lift the spatial practices and vernacular spaces of marginalized inhabitants who were simultaneously rendered out of place yet sustained life here. Following interventions in Black Studies, I describe this work as plotting and consider its specific forms in and through the built environment. Alongside this theoretical framework, I suggest critical fabulation as a method that locates and centers inhabitants’ plottings, and as such, reveals histories of and precedents for alternative buildings and landscapes. I caution practitioners and scholars against producing and describing violence in their work, and I instead advocate for learning from inhabitants as they imagine, practice, and create place for themselves.

Introduction

When City Hall talks about Yesler Terrace, the talk is of rats, of earthquakes and erupting sewage lines, of crumbling infrastructure.

Yesler Terrace residents have made their lives possible in places where others only see the impossible—a different native tongue, households headed by women, poverty. Nonetheless, the Global South is alive and well and gardening in America.

- C. Davida Ingram (Mw [Moment Magnitude] Blog, December 13, 2012)

In this article, I reiterate and expand Ingram’s question: what goes unnoticed in the reproduction of the built environment along Seattle’s Yesler Way from the 1850s to the 2010s? I emphasize marginalized inhabitants’ spatial practices and vernacular spaces as they make place to live amid discursively and materially violent plans and designs that represent them as out of place. Following scholars in Black Geographies and Black Ecologies, I describe this work as plotting—‘the actions of enslaved, free, and emancipated communities to create a distinctive and often furtive social architecture rivaling, threatening, and challenging the infrastructures of abstraction, commodification, and social control,’ according to J.T. Roane (Citation2018, 242; see also Davis et al. Citation2019; McKittrick Citation2013)—and I consider the specific forms that plotting takes in and through buildings and landscapes. Alongside this theoretical framework, I suggest Saidiya Hartman’s (Citation2008) critical fabulation as a method that locates and centers inhabitants’ plottings, and as such, reveals histories of and inspires precedents for alternative built environments. For example, what is learned by asking, as Ingram does, ‘how the families at Yesler Terrace have sustained themselves’? Likewise, how do the hauntings of Profanity Hill and sdzídzəlʔalič represent ‘a mode of refusing displacement, banishment, and archival erasure’ (Best and Ramírez Citation2021, 1045)? I argue the inhabitants of Yesler Way refuse erasure and sustain themselves through plotting—naming places, building homes, decorating interiors, growing gardens, cooking meals, organizing neighbors, and making art—and I use their spatial practices and vernacular spaces to imagine other Yesler Ways.

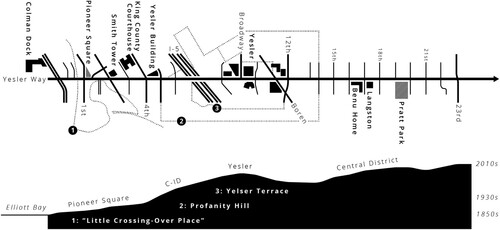

Inhabitants’ plottings in the built environment contest the structuring plats—development plans, design presentations, and marketing materials—of the city, developers, and spatial technicians (i.e. urban planners and architectural designers). Scholars in urban studies have long explained how those who conceive built environments frame marginalized inhabitants and their spaces in violent ways to justify redevelopment. Their plans and designs, sometimes explicitly and sometimes implicitly, rely on and reproduce classed, gendered, and raced oppressions. For example, the City of Seattle emphasizes the ‘crumbling infrastructure’ of Yesler Terrace, and as such, the divested neighborhood is represented as in decline and in need of redevelopment. While these plats structure settings, however, they need not also structure research—in other words, scholars should not center violence and foreclose alternatives. As Katherine McKittrick (Citation2011, 955) warns, ‘It logically follows, because they are dead and dying, the condemned and ‘without’ apparently have nothing to contribute to our broader intellectual project of ethically reimagining our ecocidal and genocidal world.’ In this article, I critically read the plats of Yesler Way—from the colonization of sdzídzəlʔalič in the 1850s to the urban renewal of Profanity Hill in the 1930s to the neoliberal redevelopment of Yesler Terrace in the 2010s—to reveal the structuring forces faced by inhabitants in this setting and emphasize the continuous complicity of planners and designers in their oppression. However, as I do not wish to simply describe this violence and there is much more to learn from their practices and spaces, I insist on centering those ways in which inhabitants along Yesler Way are plotting from a plat.

In the next section, I develop the notions of plat and plotting through scholarship in urban studies as well as ongoing work in Black Geographies and Black Ecologies; I also consider the relevance of Hartman’s method and its potential application by scholars and practitioners of built environments. I then return to Seattle to examine the plats that remade sdzídzəlʔalič, Profanity Hill, and Yesler Terrace—these texts present what are supposedly declining spaces of marginalized inhabitants to justify the production of a more controlled, normative, or profitable built environment. In the sections that follow, I trace plottings in these three moments to rethink technologies of spatial design and imagine alternatives. Finally, I conclude by noticing how inhabitants continue to plot amid the ongoing redevelopment, in addition to reiterating the broader implications of this work.

From plat to plotting

In this section, I develop the notions of plat, based on scholarship in urban studies, and plotting, thinking with scholars of Black Geographies and Black Ecologies. While it is necessary to understand and critique the historical and contemporary violence of those who conceive space, this is not an appropriate conclusion, and I argue for a shift from describing dominant plats to learning from inhabitants’ plottings. I also explain how critical fabulation enables scholars to emphasize plotting in their research and consider this method’s relevance for studying and imagining alternative built environments.

Plats are maps of or plans for a piece of land; more capaciously, they structure space, from its legal boundaries to its organization and materiality to its perception and experience. Examples include colonial land surveys and architectural plans, reports on and exhibitions of urban renewal, and renderings and advertisements for new construction in gentrifying areas. Reading plats for power makes clear that envisioning new spaces often involves devaluing existing places, particularly those of marginalized inhabitants. This is especially apparent in descriptors like decline, decay, blight, and death, but it has involved different representations over time. Moreover, the discursive violence of these plans becomes material as new spaces are constructed. In settler colonialism, Indigenous ways of knowing and relating to environments are represented as ‘uncivilized’ or ‘undeveloped,’ and they are erased as surveys render landscapes ‘vacant’ (Blomley Citation2003) and infrastructures transform them (Weizman Citation2007). In racialized renewal, ‘beautiful experiments’ in tenements and slums (Hartman Citation2019) are represented as ‘blighted’ and remade through normative designs (Herscher Citation2020). And in neoliberal gentrification, Black and Brown neighborhoods are represented as unprofitable, resulting in criminalized inhabitants (Ramírez Citation2020) and appropriated aesthetics (Summers Citation2019). Such representations justify redevelopment, which in turn, reinscribes dominant ideologies into the built environment. In this way, plats are not only about envisioning space for processes of colonial and racialized capital accumulation, but also about representing existing places as empty, broken, or deficient—a tabula rasa to be filled, a slum to be renewed, a divested area to be gentrified. As I show in the next section, plats for the reproduction of Yesler Way take many forms, but they have continuously devalued a home to differently marginalized peoples in explicit or implicit ways. I present these plats because inhabitants now live in their aftermath and contemporary planning and designing often still work in this way.

Nevertheless, it is not enough to describe a plat—concluding here forecloses the lives and lessons of inhabitants who experience and confront its violence. This is a significant intervention of Black Geographies. Arguing that ‘[p]redictions of the death of impoverished and actively marginalized racial and ethnic communities are premature,’ Clyde Woods (Citation2002, 62–63) asks:

Have we become academic coroners? Have the tools of theory, method, instruction, and social responsibility become so rusted that they can only be used for autopsies? Does our research in any way reflect the experiences, viewpoints, and needs of the residents of these dying communities? On the other hand, is the patient really dead? What role are scholars playing in this social triage?

Continuing to think with McKittrick as she reads Sylvia Wynter, I argue for a theoretical and methodological shift to plotting. To plot is also to map or plan, and again like a plat, it represents a small piece of land. Whereas plats are associated with land ownership, however, plots are associated with growing food. In addition, to plot can be to plan in secret, and it has yet another definition: a narrative. Wynter (Citation1971, 101) gets at these meanings in ‘Novel and History, Plot and Plantation,’ as she recognizes a ‘secretive history’ in both the plots of plantation novels and the plots of land given to enslaved Black peoples to grow food for themselves. As McKittrick (Citation2013, 11) explains, Wynter reveals how the plantation setting does not guarantee a narrative of death or foreclose alternative lives; she writes,

The forced planting of blacks in the Americas is coupled with an awareness of how the land and nourishment can sustain alternative worldviews and challenge practices of dehumanization … It is through the violence of slavery, then, that the plantation produces black rootedness in place precisely because the land becomes the key provision through which black peoples could both survive and be forced to fuel the plantation machine.

This intervention has been developed in recent years through Black Ecologies. Roane (Citation2018) uses Wynter’s notion to describe the burial grounds, garden parcels, and fishing practices of Black people around the lower Chesapeake Bay over time. ‘Through the fugitive practices of plotting enslaved and post-emancipation Black communities in the region created possibilities for survival, connection, and insurgency through the strategic renegotiation of the landscapes of captivity and dominion,’ explains Roane (Citation2018, 242). In Dark Agoras (Citation2023), he connects these rural forms of plotting to practices of place in Philadelphia. Roane’s attention to its built environment—that is, the material spaces of the underground (of disreputable economies) and the set-apart (of religious movements)—is especially resonant with my work along Yesler Way. Other scholars offer additional understandings of plot-and-plantation—notably, ‘narratives of social and ecological death, decay, and destruction must be emphasized and also further understood as fertile ground containing possibilities for life, wellness, and wholeness emerging from collective struggle’ (Davis et al. Citation2019, 10)—and further examples, such as informal settlements in Jamaica (Goffe Citation2023) and productive nostalgia in Louisiana (Barra Citation2023).

As these writings make clear, this intervention is not only theoretical but also methodological. It requires scholars to rethink dominant sources in conjunction with stories of marginalized peoples, ‘multifariously textured tales, narratives, fictions, whispers, songs, grooves’ (McKittrick Citation2021, 4). Simply describing and critiquing the violence of dominant sources risks reproducing oppression through overlooking the lives of inhabitants. Hartman (Citation2019) reveals this limitation and offers an alternative approach through a relevant example. Photographs of slums and tenements from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, taken by spatial technicians and social scientists, usually show empty places without inhabitants—‘[t]he reformers snap their pictures of the buildings, the kitchenettes, the clotheslines, and the outhouses’ (4), and their descriptions ‘transform the photographs into moral pictures, amplify the poverty, arrange and classify disorder’ (20). While it is certainly necessary to recognize the violence of these representations, centering their oppression in scholarship also prevents us from noticing the lives of inhabitants. In contrast, Hartman reads dominant texts against the grain and alongside everyday sources to speculatively write of the ‘insurgent ground of these lives’ (xiv), of young Black women in New York and Philadelphia not as problems but as planners. Within the slum and tenement, she argues, ‘[b]eautiful experiments in living free, urban plots against the plantation flourished, yet were unsustainable or thwarted or criminalized before they could take root (17).’ This approach extends Hartman’s work in Scenes of Subjection (Citation1997, 11), involving ‘excavations at the margins of monumental history,’ and ‘Venus in Two Acts’ (Citation2008, 3), in which she asks, ‘how does one rewrite the chronicle of a death foretold and anticipated, as a collective biography of dead subjects, as a counter-history of the human, as the practice of freedom.’ These three writings present Hartman’s method of critical fabulation, or ‘re-presenting the sequence of events in divergent stories and from contested points of view … to imagine what might have happened or might have been said or might have been done’ (11).

Wynter’s notion of plot-and-plantation, as it has been developed in Black Geographies and Black Ecologies, and Hartman’s method of critical fabulation have much to offer scholars and practitioners who are serious about liberation in and through built environments. For scholars, this intervention suggests an approach that does not reproduce the power of those who conceive space but centers inhabitants’ agency as they make place for themselves—no matter the form, however brief or lasting. Here, I echo the Feminist Art and Architecture Collaborative’s (Citation2017, 277) call for historians to study contested spaces, like ‘vernaculars, interiors, and social spaces.’ For practitioners, it offers another way into a project, as the imaginings, practices, and creations of inhabitants become the precedents from which to design. Two exhibitions—This is a Black Spatial Imaginary in 2017 at Paragon Gallery in Portland and Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America in 2021 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York—suggest the alternative built environments and social relations that emerge when designers learn from marginalized inhabitants. In later sections, I practice this theory and method to lift what goes unnoticed along Yesler Way—how inhabitants plot this place otherwise over time. I start, however, with a walk up this street to note its historical and contemporary plats—the plans and designs that structure but do not determine the narratives of this place.

Yesler Way

Returning to Seattle in the remaining sections, I first read Yesler Way as a palimpsest of plats and then again for the traces of ‘relics and ruins of former times, former worlds’ (Savoy Citation2015, 2)—that is, inhabitants’ plottings of place from and against these plats. Sdzídzəlʔalič consisted of a village of ‘up to eight longhouses’ on a small, wooded promontory between the sea, tidal flats, and a lagoon; a nearby trail led over the hill to xwqwíyaqwayaqs, ‘Saw-Grass Point,’ where people gathered tule along the lake to make household items (Thrush Citation2017, 229, 248). With its longhouses, places like sdzídzəlʔalič were the spatial centers for ‘nearby seasonal camps, resource sites, and sacred places’ (Thrush Citation2017, 23) of dxwdəwʔabš, or Duwamish people, who have lived in this area with the Lakes and Shilshole peoples for millennia. By 1852, however, only one ruined longhouse remained at this site, likely due to epidemics brought by expeditions to the region in the late 18th and early 19th centuries (Thrush Citation2017, 24–25). In addition to fatally infecting Native peoples, these expeditions represented and renamed the landscape through cartography, such as George Vancouver’s ‘Coast of N.W. America’ (1798) and Charles Wilkes’s ‘Oregon Territory’ (1841). The cartographers of these early plats approached the landscape as a terra incognita and nullius to be explored and territorialized—they erased existing Indigenous geographies and presented sdzídzəlʔalič as ‘Piners Point,’ on the ‘Elliott Bay,’ near ‘Admiralty Inlet’. In this way, settlers ‘saw the wealth of the land as it could and would be, expressed in words like “arable,” “improvement,” and “export”,’ writes Coll Thrush (Citation2017, 28–29).

The Denny Party and ‘Doc’ Maynard settled at sdzídzəlʔalič, submitting their surveyed claims in 1853 (Speidel Citation1967, 217–218). For these plats, the existing topography was problematic, requiring filling, deforesting, and regrading to build grid plans. Henry Yesler’s sawmill, which opened near the neck of the promontory, helped reify this envisioned landscape—Thomas Phelps’s ‘Plan of Seattle’ (1855–1856) shows ‘saw dust’ in place of the small tidal stream on Wilkes’s map, as well as some deforestation. While this plan includes a ‘Lake Trail,’ likely between sdzídzəlʔalič and xwqwíyaqwayaqs, it contrasts the settlers’ labeled structures with ‘hills and woods thronged with Indians’. Despite Coast Salish peoples’ roles in constructing the new built environment—‘Native men cleared the land and helped build homes … and Native women did the washing within those homes’ (Thrush Citation2017, 49)—this oppositional relationship became policy. When it was incorporated in 1865, Seattle adopted an ordinance decreeing ‘no Indian or Indians shall be permitted to reside or locate their residences on any street, highway, lane, or alley or any vacant lot,’ explicitly segregating its infrastructure. Native workers were allowed to remain if employed and housed by a settler, enforcing their designs of domesticity. Settlers reinforced their architecture by burning the housing of Coast Salish peoples and displacing them to Ballast Island, a dumping ground on the waterfront (Thrush Citation2006, 99).

When incorporated, ‘Seattle was a small, struggling community economically dominated by Yesler’s sawmill and a few hardware and mercantile stores, boarding houses, barbershops, saloons, and brothels—all catering to the loggers, miners, and sailors who regularly passed in and out of town’ (Taylor Citation1994, 16). Successive aerial perspective maps from 1878, 1884, 1891, and 1904 reveal its development: structures and roads expand toward ‘Lake Washington’ and ‘Lake Union,’ while the buildings around ‘Mill Street’ and ‘Front Street’ (renamed ‘Yesler Way’ and ‘First Avenue’ in 1895) are made taller and heavier. These plats not only represent, but also speculate. For example, railways on piers above the tide flats become named roads sketched across the reclaimed bay. By the 1920s, early products by the Kroll Map Company show an expansive street grid, a ship canal between the ‘Puget Sound’ and ‘Lake Washington,’ and a straightened ‘Duwamish River’. Kroll’s ‘Birdseye View’ (1925) overemphasizes the regrading projects of this period, envisioning Seattle as entirely flat. Such cartographic representations reveal settlers’ ‘improvements,’ predicated on an inefficient topography. Surveys by the Sanborn Map Company from this time further evidence the physical changes, as well as reveal how the built environment was raced and gendered. While most of the surveyed city is divided into rectangular lots with residential or commercial structures, the area south of Yesler Way includes identity labels: ‘Chinese Washing,’ ‘Female Dwellings,’ ‘Siwash Huts,’ and ‘Japanese Lodgings.’ Some of these structures, which do not align with lots, are called ‘shanty’ or ‘cabin,’ while others are described as ‘poor,’ ‘cheap,’ ‘dilapidated,’ or ‘old.’ These plats explicitly note damage, associating specific peoples with it.

These various maps reveal the significance of Yesler Way—as a successor to the ‘Lake Trail,’ as a ‘Skid Road’ for sliding logs, and as a line of segregation. By the 1900s, this street separated ‘pioneers,’ older (primarily white) settlers in the north, from ‘transients,’ newer (increasingly Asian and Black) settlers, who worked as laborers and found less restrictive, more affordable accommodations just south of Yesler Way (Asaka Citation2018, 239; Taylor Citation1994, 16). Later plats, like the 1921 Alien Land Law (Chin Citation2001, 47), rental restrictions and racial covenants (Taylor Citation1994, 84), and Kroll’s ‘Commercial Map of Greater Seattle’ (1936), limited most non-white inhabitants to this area. The map, of lending risk, shades the neighborhood south of Yesler Way as ‘business,’ as if people do not live there, while the surrounding area is redlined and marked ‘hazardous’—it is ‘composed of various mixed nationalities … [h]omes generally old and obsolete in need of extensive repairs.’ Like earlier surveys, these plats explicitly connect identities to places and structures, presenting them all as in decline.

Such descriptions rendered a stretch of Yesler Way, a small neighborhood called Profanity Hill, as a site for urban renewal in 1939. Profanity Hill was home to ‘[s]ome one thousand residents—42% white, 33% Japanese, and the rest Filipinos, Chinese, Hawaiians, and Blacks … 18 prostitution houses, a grocery store, a Chinese laundry, and two Japanese-operated hotels … [and] three Japanese churches’ (Chin Citation2001, 66). Applying for federal funds through the Housing Act of 1937, the Seattle Housing Authority (SHA) proposed demolishing Profanity Hill to construct the city’s first housing project, ‘Yesler Terrace’. Megan Asaka (Citation2018, 234) reads this proposal against the grain, arguing ‘[t]he SHA strategically utilized technologies such as photography and mapping to create a visual narrative of abandonment and absence.’ On one map, for example,

[t]he SHA reserved brown for slum areas, which meant that any structure colored brown could not be depicted as anything else but a slum—not a church, commercial area, or residence … the SHA categorized nearly the entire demolition zone as a slum area, obliterating the diverse ways in which Profanity Hill residents actually used the buildings (246–248).

After its construction, the physical form of Yesler Terrace was celebrated (J. Lister Holmes, Pencil Points, November 1941), and despite the displacements, requirements, and limitations, its social composition symbolized desegregation—it was the country’s ‘first racially integrated public housing project,’ an oft-repeated fact today. Nevertheless, this did not guarantee preservation or praise in subsequent decades. An article by Mayumi Tsutakawa states ‘critical work needs to be done on utilities, heating, kitchens, and bathrooms’ (International Examiner, December 31, 1976), a modernization project that would not be funded or completed for several years. By the late 1980s, Yesler Terrace was associated with violence—Timothy Egan describes Yesler Terrace as ‘a subsidized housing complex where a child was likely to hear gunfire before he learned to talk’ (New York Times, January 5, 1990). These issues of maintenance and perception accompanied changing demographics—residents were increasingly Black and Asian—and governance—neoliberal ideologies, in addition to new solutions to poverty, such as ‘‘deconcentrat[ing]’ the poor’ through public housing demolition (Crump Citation2002, 582). When Yesler Terrace again required maintenance in the 2000s, the SHA suggested ‘[m]oney to pay for these improvements could be raised by selling some of the acreage to private developers’ (Stuart Eskenazi, Seattle Times, June 9, 2004). By 2011, it proposed a ‘highly visionary,’ mixed-income, mixed-use neighborhood built in partnership with private developers, like Vulcan Real Estate. Unlike the 561 apartments for ‘extremely low-income’ residents in two-story row houses with individual yards, Yesler—‘just ‘Yesler’’ (Jen Graves, The Stranger, November 30, 2016)—will be ‘a campus of mid-rise buildings that will house more than five times as many people … in a range of income brackets—rich and poor’ (Lornet Turnbull, Crosscut, May 18, 2017).

The redevelopment produced reams of paperwork: the Citizen Review Committee’s ‘Definitions & Guiding Principles’ (2007), workshops, analyses, and renderings by CollinsWoerman (2008–2009), the SHA’s Environmental Impact Statements (2010, 2011) and ‘Yesler Terrace Development Plan’ (2011), design guidelines by GGLO and the City (2012), architectural presentations for the design review board, and developers’ marketing materials. Like the texts undergirding sdzídzəlʔalič’s colonization, the environment’s ‘improvement,’ the city’s segregation, and Profanity Hill’s renewal, these contemporary plats imagine a ‘better future’ through devaluing the present. Some explicit statements include the SHA’s desire to ‘reintegrate Yesler Terrace’ into the city and a comparison by Vulcan Real Estate’s Ada Healey: Yesler Terrace is like South Lake Union fifteen years ago, ‘[y]ou drove through it, not to it’ (Marc Stiles, Puget Sound Business Journal, February 24, 2015). More often, deficiencies are implied. For example, after the SHA nominated Yesler Terrace for historic preservation—‘[w]e didn’t want to get further down in the process and have someone else nominate us’ (Cienna Madrid, The Stranger, September 2, 2010)—only the Steam Plant was designated. The row houses had lost their ‘integrity,’ their ‘historical and architectural significance.’ The design guidelines are similarly unimpressed, offering inspiration from other neighborhoods and cities. As a presentation summarizes, ‘[a]rchitecturally the area does not offer much guidance.’ In addition, across many of these documents, the inhabitants of this place are absent. Rather, it is settlers, spatial technicians, and the SHA who represent the history of Seattle and Yesler Terrace—they turned a ‘blighted’ area into ‘new dwellings with individual outdoor spaces, views, and community amenities,’ and the redevelopment will ‘renew Yesler’s promise.’ When inhabitants are included, it is to demonstrate their ‘participation’ or market their ‘multiculturalism’. In some texts, this ‘outreach’ is thoroughly documented and supposedly informs the proposal; in other texts, uncaptioned photographs of smiling, diverse inhabitants accompany proposals for expensive living and retail spaces, implying their approval and presence. While construction and gentrification may displace these inhabitants, the texts market their flattened cultures for consumption. For instance, living at the market-rate Batik, a ‘home in harmony that’s welcoming to all,’ residents will hear ‘different languages’ and dine at ‘ethnic eateries’. The leasing website presents colorful apartments alongside people of color. In other new buildings, culture is, at best, public art, and at worst, colorful trim; it is something for developers to capitalize and residents to consume. Unlike previous plats, these contemporary texts do not use violent labels to justify redevelopment but imply that inhabitants have little to offer the new design besides displays of ‘participation’ or advertisements for ‘multiculturalism’.

Yesler Way’s successive plats evince the concrete work of settler, racial capitalism in and through built environments. This is a necessary examination, for these layers of development affect the street’s contemporary topography and planners and designers continue to work in these ways. However, there are other narratives, stories, and traces within this palimpsest, and as Anna Livia Brand (Citation2022, 278) suggests, ‘disarraying the stratigraphy uncovers a way of seeing the landscape and methodologically opens up ways to distill and contest its historical and ongoing spatial logics.’ In the next three sections, I return to three moments of plotting to learn about histories of and precedents for alternative built environments.

sdzídzəlʔalič

The rastaman thinks, draw me a map of what you see / then I will draw a map of what you never see / and guess me whose map will be bigger than whose? / Guess me whose map will tell the larger truth?

- The Cartographer Maps His Way to Zion (Miller Citation2014, 19)

Several maps offer other examples of Indigenous plotting, for they reveal where and how Coast Salish peoples sustained themselves despite settlers’ exclusive ordinances and violent actions. These examples suggest how Hartman’s method for reading at the margins of an archive can be applied to cartography. An 1878 perspective map by Eli Sheldon Glover includes people, canoes, and tents on the waterfront at the end of Main Street; there is more life on this small beach than in the city’s empty streets. An 1884 perspective map by Henry Wellge, as well as Sanborn surveys from 1888 and 1893, show the formation of Ballast Island at the end of Washington Street (Paul Dorpat and Jean Sherrard, Seattle Now & Then, May 12, 2012). Another plate from the 1893 survey includes ‘Siwash Huts’ near Jackson and 4th Streets, along the shrinking tide flats. Like other labels in this survey, both terms are derogatory—the former is a Chinook Jargon word for Indigenous peoples that comes from the French word for ‘wild’ or ‘savage,’ while the latter stands in contrast to ‘dwellings.’ Nevertheless, their very presence on these maps shows that the Duwamish and other Coast Salish peoples continued to make lives around sdzídzəlʔalič. Although cartography worked to name, naturalize, and neutralize a colonial infrastructure through disregarding and transforming the existing landscape, it was not totalizing. Indeed, despite intentions, plats are never wholly determining and other narratives are present. A counter-reading for plotting reveals the resilience of Indigenous life, be it at a map’s margins, as with Ballast Island, or beyond the map, as with Whulshootseed place names.

Profanity Hill

All the World is there.

It runs from the safe solidity of honorable marriage to all of the amazing varieties of harlotry—from replicas of Old World living to the obscenities of latter decadence—from Heaven to Hell.

- ‘A Possible Triad on Black Notes’ (Bonner Citation1987, 102)

This method of critical fabulation, which speculates against the grain and from the margins of dominant texts, also suggests how built environments might be planned and designed in a way that starts from inhabitants’ creative plottings. To learn, fabulate, and design from Profanity Hill in particular, I read Miller’s (Citation1979) memoir of her time as the SHA’s relocation supervisor against the grain. Despite her work—rendering the neighborhood a ‘slum,’ relocating its residents, and presenting normative designs—Miller cannot help but note inhabitants’ spatial imaginings and creations:

Through the fence, I glimpsed a garden. Sweet peas climbed up the weather-stained wall of an old house; below, bloomed rows of yellow and red roses; in the corner, blue hyacinths hovered over yellow and purple pansies; and a border of white shasta daisies at the rear of the yard almost hid the shack in the lot behind (14).

The tinkling sounds came from a home-made mobile of miniature toys swinging from a pink ribbon tacked to the ceiling … A wide board plastered with colorful comic strips and placed over two wooden boxes served as a bench. A cot with army blankets stool along the other wall; bright Chinese calendars hung above it (27).

Mrs. Walker had turned the hovel into a cozy home with bright print slipcovers, hooked rugs and sheets cut up for living room drapes. Wooden crates had been made into bookshelves which were jammed with children’s books as well as classics … flour sacks had been dyed yellow for curtains, coffee cans painted blue served as canisters and a tiny orange pot held a red geranium (50).

Yesler Terrace

‘If my father was me, he probably take a pencil and scheme some changes for the house’ … he mark in some plants, some vegetables, some flowers.

- His Own Where (Jordan Citation1971, 78–79)

In addition to revealing social appropriations at the scale of the neighborhood, Yesler Terrace Happening shows how inhabitants make physical changes to create beautiful yards and homes. As the newspaper puts it, ‘meet your neighbor[s]’:

The list of flowers and vegetables in Jessie O’Kelley’s small front yard is unbelievable … Tulips, Tomatoes, Pansies, Mustard, Dahlias, Spinach, Roses, Beans, Gladiolas, Corn, Phlox, Zucchini, Begonias, Onions, Hyacinths, Collards, Beets … That isn’t all. Inside her apartment are luxuriant tropicals and African violets. Everything seems to grow and bloom for Jessie (June, 1979).

While looking around his house I could tell that Joe [Williams] also liked to tinker and build things. The most spectacular thing is right in the middle of his yard. He built a feeding house for squirrels and birds (September, 1979).

Last year [‘Pete’ Lovenia Jones] grew greens, beans, peppers, onions, garlic, tomatoes, and strawberries. Pete also likes to grow flowers. She has grown a flower for every year she has lived in Yesler Terrace (April, 1981).

Still plotting

Amid the ongoing redevelopment of Yesler Terrace, its inhabitants are still plotting. An early redevelopment document includes a ‘Minority Report’ (2007), which criticizes the privatization of Yesler Terrace and argues density should only be added to expand public housing—‘not for ‘sustainability,’ ‘smart growth,’ ‘vanity,’ or planning awards and not to satisfy contractors and developers who would profit.’ In 2016, residents raise similar concerns at a YTCC meeting recorded by artist d.k. pan (https://youtu.be/BsxB1nOojBw). Attendees question the city’s definition of ‘affordability’ and imagine retail spaces for small, local businesses. As one attendee states, ‘They don’t need to push away low-income people and build a high-rise … we live here a long time, maybe ten years, forty years, and they push us out the city—that’s not fair.’

This video is just one of pan’s projects from their time as an artist in residence at Yesler Terrace. Another project (https://vimeo.com/300863881) involves ‘photo sessions for the residents of the neighborhood and surrounding communities,’ revealing life where the city sees damage. Yet another project ‘bear[s] witness to the rapid development and loss of the nation’s first integrated public housing tract’ through a series of dated and geolocated videos (e.g. https://vimeo.com/300863821); the short clips contrast walkways, playgrounds, and gardens with boarded windows, tree removal, and construction work. The photographs of Yesler Terrace Youth Media (http://ytyouthmedia.com/, available on Wayback Machine) are similar—for example, a series of photos from 2014 show children playing on a stone retaining wall, heavy equipment pulling apart a row house, a resident posing in their lush backyard garden, and a child looking at a pile of debris. These photos not only counter representations of this supposedly ‘damaged’ place and questions who is responsible for this damage, but also witness the material destruction of discursively violent texts. Like its photographs, Yesler Terrace Youth Media’s videos are also design documents that represent Yesler otherwise. A tour of the Yesler Community Center, where inhabitants study, cook, and dance suggests another way of doing ‘mixed-use,’ while other videos consider childcare and gardening, previously organized by inhabitants but made difficult by new urban and architectural designs. Still other videos chart a cartography of spatial struggles, connecting the redevelopment of Yesler Terrace to the construction of a nearby youth jail and gentrification in surrounding neighborhoods.

Most significantly, produce and flowers are still growing at Yes Farm, organized by the Black Farmers Collective. Jas Keimig writes, ‘Replete with dozens of gardens, a beehive, a greenhouse and a covered shed, Yes Farm is now a green gem amongst the gray concrete of the city’ (i-D, December 17, 2021). The farm grows ‘[s]oul food staples,’ like some previous inhabitants, in addition to directing its harvest to Black and Brown communities and offering programs for youth of color.

These latest efforts—public comments, critical media, and communal farming—reveal some of the ways marginalized inhabitants continue to imagine and create Yesler Way otherwise. Like previous generations, they are constructing alternative built environments and social relations along the street. This infrastructure may not have the apparent permanence of most buildings, but inhabitants’ practices are far more resilient than the dominant landscape, which has been successively renovated since the 1850s. In this article, I called attention to these spatial practices and vernacular spaces—or plotting, following work in Black Geographies and Black Ecologies—in contrast to violent conceptions of marginalized peoples and their places—what I call plats. I argued that plotting sustains life within a plat, as well as suggested how critical fabulation can be used to learn from plotting, be it alternative histories of buildings or radical futures for landscapes. While it remains necessary to reveal how plats contribute to unjust topographies and the continued complicity of those who conceive space today, I also caution scholars against simply describing this violence in their work and instead advocate for lifting and learning from inhabitants’ lives as they create place for themselves amid this violence. These are the precedents that should inform the work of both practitioners and researchers.

Among some of the last blocks of Yesler Terrace to be razed was a home near the Yesler Way and 8th Avenue. In 2018, artist Rachel Kessler worked with inhabitants to transform this home into ‘a community gallery and gathering space’ for cookouts, films, and workshops. An abbreviated quote from bell hooks (Citation1994, 281) was painted in English on one side of the building and translated around the corner: ‘the function of art is … to imagine what is possible.’ In this context, I read the statement as a critique of practitioners and scholars of built environments—does our work ‘tell it like it is’ or ‘imagine what is possible’? After two centuries of making plats for Yesler Way, we ought to learn and design from inhabitants’ creative imaginings—their plottings of sdzídzəlʔalič, Profanity Hill, and Yesler Terrace. For what if Yesler was not a plat in the image of the city, but the city was plotted in the image of Yesler Terrace?

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Katharyne Mitchell, Naya Jones, Xavier Livermon, and the CUS working group at UCSC, along with two reviewers and City editors for their feedback. Thanks as well to Brian McLaren, Mark Purcell, and Megan Ybarra, whose comments on my M.S. thesis inspired this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Gregory Woolston

Gregory Woolston is a PhD Student in the Department of Sociology at the University of California, Santa Cruz, United States. Email: [email protected]

References

- Asaka, Megan. 2018. “‘40-Acre Smudge’: Race and Erasure in Prewar Seattle .” Pacific Historical Review 87 (2): 231–263. https://doi.org/10.1525/phr.2018.87.2.231.

- Barr, Julian. 2017. “Pioneer Square and the Making of Queer Seattle.” ArcGIS StoryMaps. https://arcg.is/1GfC4K.

- Barra, Monica Patrice. 2023. “Plotting a Geography of Paradise: Black Ecologies, Productive Nostalgia, and the Possibilities of Life on Sinking Ground .” Transforming Anthropology 31 (1): 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/traa.12243.

- Basso, Keith H. 1996. Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press .

- Best, Asha, and Margaret M. Ramírez. 2021. “Urban Specters .” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 39 (6): 1043–1054. https://doi.org/10.1177/02637758211030286.

- Blomley, Nicholas. 2003. “Law, Property, and the Geography of Violence: The Frontier, the Survey, and the Grid .” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 93 (1): 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8306.93109.

- Bonner, Marita. [1933] 1987. “A Possible Triad on Black Notes.” In Frye Street & Environs: The Collected Works of Marita Bonner, edited by Joyce Flynn and Joyce Occomy Stricklin, 102-118. Boston: Beacon Press Books .

- Brand, Anna Livia. 2022. “The Sedimentation of Whiteness as Landscape .” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 40 (2): 276–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/02637758211031565.

- Chari, Sharad. 2021. “The Ocean and the City: Spatial Forgeries of Racial Capitalism .” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 39 (6): 1026–1042. https://doi.org/10.1177/02637758211030922.

- Chin, Doug. 2001. Seattle’s International District: The Making of a Pan-Asian American Community. Seattle: International Examiner Press .

- Crump, Jeff. 2002. “Deconcentration by Demolition: Public Housing, Poverty, and Urban Policy .” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 20 (5): 581–596. https://doi.org/10.1068/d306.

- Davis, Charles L. 2020. “Henry Van Brunt and White Settler Colonialism in the Midwest.” In Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, edited by Irene Cheng, Mabel O. Wilson, and Charles L. Davis, 99–115. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press .

- Davis, Janae, Alex A. Moulton, Levi Van Sant, and Brian Williams. 2019. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, … Plantationocene?: A Manifesto for Ecological Justice in an Age of Global Crises .” Geography Compass 13 (5): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/gec3.12438

- De Barros, Paul. 1993. Jackson Street after Hours: The Roots of Jazz in Seattle. Seattle: Sasquatch Books .

- Feminist Art and Architecture Collaborative. 2017. “Counterplanning from the Classroom .” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 76 (3): 277–280. https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2017.76.3.277.

- Goffe, Rachel. 2023. “Reproducing the Plot: Making Life in the Shadow of Premature Death .” Antipode 55 (4): 1024–1046. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12812.

- Harris, Diane. 2012. Little White Houses: How the Postwar Home Constructed Race in America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press .

- Hartman, Saidiya. 1997. Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America. Oxford: Oxford University Press .

- Hartman, Saidiya. 2008. “Venus in Two Acts .” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 12 (2): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1215/-12-2-1.

- Hartman, Saidiya. 2019. Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals. New York: W. W. Norton & Company .

- Herscher, Andrew. 2020. “Black and Blight.” In Race and Modern Architecture: A Critical History from the Enlightenment to the Present, edited by Irene Cheng, Mabel O. Wilson, and Charles L. Davis, 291–307. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press .

- hooks, bell. 1994. Outlaw Culture: Resisting Representations. New York: Routledge .

- Imhof, Eduard. 1975. “Positioning Names on Maps .” The American Cartographer 2 (2): 128–144. https://doi.org/10.1559/152304075784313304.

- Itō, Kazuo. 1973. Issei: A History of Japanese Immigrants in North America. Seattle: Japanese Community Service .

- Jordan, June. 1971. His Own Where. New York: Feminist Press .

- Kessler, Rachel. 2017. “Profanity Hill: A Tour of Yesler Way.” In Ghosts of Seattle Past: An Anthology of Lost Seattle Places, edited by Jaimee Garbacik and Josh Powell, 45–52. Seattle: Chin Music Press .

- McKittrick, Katherine. 2011. “On Plantations, Prisons, and a Black Sense of Place .” Social & Cultural Geography 12 (8): 947–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2011.624280.

- McKittrick, Katherine. 2013. “Plantation Futures .” Small Axe: A Caribbean Journal of Criticism 17 (3): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1215/07990537-2378892.

- McKittrick, Katherine. 2021. Dear Science and Other Stories. Durham: Duke University Press .

- Miller, Irene Burns. 1979. Profanity Hill. Everett: Working Press .

- Miller, Kei. 2014. The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion. Manchester: Carcanet .

- Monmonier, Mark. 1991. How to Lie with Maps. Chicago: University of Chicago Press .

- Ramírez, Margaret M. 2020. “City as Borderland: Gentrification and the Policing of Black and Latinx Geographies in Oakland .” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 38 (1): 147–166. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819843924.

- Roane, J.T. 2018. “Plotting the Black Commons.” Souls: A Critical Journal of Black Politics , Culture, and Society 20 (3): 239–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/10999949.2018.1532757.

- Roane, J. T. 2023. Dark Agoras: Insurgent Black Social Life and the Politics of Place. New York: New York University Press .

- Savoy, Lauret E. 2015. Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape. Berkeley: Counterpoint .

- Simone, AbdouMaliq. 2018. Improvised Lives: Rhythms of Endurance in an Urban South. Cambridge: Polity Press .

- Soja, Edward. 1989. Postmodern Geographies: The Reassertion of Space in Critical Social Theory. New York: Verso .

- Speidel, William C. 1967. Sons of the Profits or, There’s No Business Like Grow Business! The Seattle Story, 1851–1901. Seattle: Nettle Creek Publishing Company .

- Summers, Brandi Thompson. 2019. Black in Place: The Spatial Aesthetics of Race in a Post-Chocolate City. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press .

- Taylor, Quintard. 1994. The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District, from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era. Seattle: University of Washington Press .

- Thrush, Coll. 2006. “City of Changers: Indigenous People and the Transformation of Seattle’s Watersheds .” Pacific Historical Review 75 (1): 89–117. https://doi.org/10.1525/phr.2006.75.1.89.

- Thrush, Coll. 2017. Native Seattle: Histories from the Crossing-Over Place. Seattle: University of Washington Press .

- Tuck, Eve. 2009. “Suspending Damage: A Letter to Communities .” Harvard Educational Review 79 (3): 409–428. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.3.n0016675661t3n15.

- Weizman, Eyal. 2007. Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation. New York: Verso .

- Wong, Marie Rose. 2018. Building Tradition: Pan-Asian Seattle and Life in the Residential Hotels. Seattle: Chin Music Press .

- Woods, Clyde. 1998. Development Arrested: The Blues and Plantation Power in the Mississippi Delta. New York: Verso .

- Woods, Clyde. 2002. “Life After Death .” The Professional Geographer 54 (1): 62–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/0033-0124.00315.

- Wynter, Sylvia. 1971. “Novel and History, Plot and Plantation .” Savacou 5: 95–102.