Abstract

São Paulo’s Minhocão (Big Worm) is a 3.5 km elevated expressway that cuts across a dense part of the central city. Opened in 1971, it was controversial from the start, and widely held responsible for the decline of the city’s historic centre in the 1970s and 1980s. However, it has been gradually tamed over the years, first closed to traffic at night, and then at weekends and on holidays, becoming an impromptu park, the Parque Minhocão, which has had official status since 2014. Those informal closures have been accompanied by numerous architectural schemes over the years to make the Minhocão a permanent park on the lines of New York’s High Line. The Parque Minhocão in its present condition represents a stand-off between various interest groups, all of whom have claims on it as public space. The paper explores the history of the Parque Minhocão since 1969 through different forms of visualisation, arguing that its present condition, however imperfect, keeps multiple and contradictory interests in balance.

Urban expressways are, conventionally speaking, the enemies of public space. They do all kinds of bad things to it: they slice it in pieces, they fill it with pollution and noise, and they exacerbate existing racial and social divisions (see Berman Citation1983; DiMento and Ellis Citation2013). They have a prominent place in Marc Augé’s (Citation1996) famous demonology of non-places, archetypes of transactional spaces that keep their users under close surveillance, the opposite of ‘anthropological’ place (1–2). The subject of this paper, São Paulo’s Elevado João Goulart, but nearly always referred to as the Minhocão, or ‘Big Worm’, is a rare example of an urban expressway that has, through a mixture of activism, accident, and some design become a temporary public space: the Parque Minhocão (see ).

The Minhocão has long been closed to traffic at night and at weekends. At these times it becomes an impromptu park, often said to be the nearest thing São Paulo has to a beach (Van Mead Citation2017; Miguel Citation2023). There have been periodic campaigns for the Minhocão’s demolition, most recently the Movimento Desmonte do Minhocão (MDM), but for the time being the loudest voices are those that support its retention, and its use for leisure purposes (Machado Citation2015; Yamashita Citation2019, 292). Its peculiar situation has attracted a good deal of interest outside of Brazil since the mid-2010s (Hochuli Citation2020; Millington Citation2017; Van Mead Citation2017). Images of it as a leisure space abound, both in reality on social media and as a fantasy in innumerable architectural projects for its renovation; it has been the subject of at least two documentary films (Barba Citation2016; Bühler, Pastorelo, and Sodré Citation2007). Its road surface has been the site of regular film screenings since 2010, as well as the site of a temporary Olympic-sized swimming pool in 2014 (Florence Citation2010; Senra Citation2014). Since 2017, a public art programme, the Museu de Arte de Rua, has added 40 or so large-scale murals to the empty gable ends of adjacent buildings, filling spaces left vacant by the Cidade Limpa programme abolishing outdoor advertising (Prefeitura de São Paulo Citation2006, Citation2017). Since 2016, the Parque Minhocão has had legal status, and since then, there have been attempts, currently stalled, to make it into a permanent park (Câmera Municipal de São Paulo Citation2016; Levy Citation2015; Rodrigues Citation2017).

It is far from the only example of such transformations of expressways into quasi-public space, and there are now many more complete, not to say more expensive, transformations: Seoul’s Cheonggyecheon park (2005) and Boston’s Rose Kennedy Greenway (completed 2008) are the most celebrated examples, not least because of their astronomical cost. However, the Minhocão is unusual in that it has undergone little physical transformation at all, aside from fencing at the side of the roadway to prevent accidents, the periodic addition of street furniture, and some scaffold-like pedestrian access points (Comolatti Citation2022). Its transformation into semi-public space bears revisiting at a time when calls for transformations of expressway infrastructure have become more frequent (for example, Leadbetter Citation2023). In particular, the Minhocão in its current, unresolved condition suggests the possibility of a route between inaction and complete reformation, one that might be capable, however imperfectly, of balancing contradictory interests. This paper explores three instances in the history of the Parque Minhocão: the concept of the park legible in the original expressway design, the much later creation of the official Parque Minhocão and architectural designs for it, and lastly, what might be called an ‘alternative’ Parque Minhocão, based on a realistic assessment of the lived experience of the area. The latter, even if largely accidental, I argue offers modes of accommodating diverse and contradictory interests, and may provide a more realistic model for the rehabilitation of expressway infrastructure elsewhere.

The paper draws on various concepts of public space. In the Anglophone world it was until recently a commonplace once to bemoan the death of public space, under pressure from the rise of the shopping mall, or the private car, or the private security industry, or the decline of the bourgeois public realm, or a combination of all of these things (Davis Citation1990; Harvey Citation1990; Rogers Citation1997; Sennett Citation1977). Brazil has its own variants of this literature, focused especially on the erosion of public space through the fear of crime (Caldeira Citation2000; de Souza Citation2008). In this literature, São Paulo, like a southern hemisphere Los Angeles, plays an outsize role, and the Minhocão has been emblematic of it (it is the cover image of Caldeira’s Citation2000 book, for example). These accounts of public life remain important background here as they help explain the desire for new forms of urban public space, including the Parque Minhocão. But they describe historic conditions, such as urban depopulation, that no longer necessarily obtain. The Parque Minhocão—or at least the official version of it—arguably has more in common with the new public spaces that have been described by David Madden (Citation2010) as ‘publicity without democracy—a concept of the public that speaks of access, expression, inclusion, and creativity but which nonetheless is centered upon surveillance, order, and the bolstering of corporate capitalism’ (187; see also Madden Citation2017). Madden was describing spaces in New York and London, but his concerns have relevance here, certainly when it comes to the fears generated by the visualisations of the so far unrealised permanent Parque Minhocão.

The source material here is in large part visual: visualisations of the Minhocão produced by architects and engineers, as well as representations on film and in photography. For that I draw on the work of Gillian Rose and her co-authors, who, writing about digital architectural visualisations, have argued the cultivation of ‘atmospheres’ above all. The ‘experience economy’ they write ‘has fuelled an increased concern with the notion of atmosphere’, a product of an economy increasingly fixated on aesthetics (Degen, Melhuish, and Rose Citation2015, 6). The result is public space increasingly envisaged as a species of theatre, the city in effect as stage set. The images described here, digital or not, are all about atmosphere, and without them the project of the Parque Minhocão is incomprehensible. It is, and has always been, a profoundly aesthetic project; it is, in large part, its images.

The Minhocão as park, 1969

To make sense of the Parque Minhocão now, we need to begin at the beginning. As far as it is possible to tell, the Minhocão was a project of Paulo Maluf, the pro-development, engineering-trained, 35th mayor of São Paulo, although it likely drew on a metropolitan plan done in the earlier Prestes Maia administration. The laws passed to enable its construction are notably unspecific in their detail (Prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo Citation1968, Citation1969). As built, it lies in the centre of São Paulo, just to the south of the old financial district, erected along the centre of two existing boulevards, a short stretch of the Rua Amaral Gurgel and a longer section of the Avenida São João to its junction in the west with the Avenida Francisco Matarazzo. It transformed the Avenida São João in particular, a popular European-style boulevard once celebrated by Claude Levi-Strauss (Citation1973, 122). Maluf was close to Brazil’s military government, and the Minhocão is in many ways legible as one of its products. It was a government that oversaw—in terms that will be familiar to students of 19th-century Paris—a combination of transformations in urban infrastructure, a consumer boom, and political repression. The Minhocão project was announced in 1969, in the middle of what were later understood as the years of greatest political repression, the ‘anos de chumbo’ (Cordeiro Citation2009). It is forever associated with that period, not least because its original name, the Elevado Artur Costa e Silva commemorated the army general and Brazilian president in power at the start of the project (Costa e Silva died in office the year it was announced). It was completed in 14 months from start to finish, without closing of any of the affected roads, and it was, as a delighted Maluf announced, the ‘largest work in reinforced concrete in all of Latin America’ (Folha de São Paulo Citation1971; Maulf Citation1969). It was opened on the city’s annual founding day in January 1971 to some fanfare, along with the newly constructed Praça Roosevelt, a futuristic public square-cum-shopping mall. The official name, the Elevado Artur Costa e Silva, never stuck—it was always the Minhocão, despite occasional complaints (Gorizio Citation1971).

In retrospect therefore it is tempting to read the Minhocão as the trace of political violence, a literal scar (Artigas, Mello, and Castro Citation2008, 7–10; Rodrigues Citation2013; Wisnik Citation2012, 96–98). There are numerous contemporary news reports that read the Minhocão in this way too, even in ostensibly friendly newspapers (Estado de São Paulo Citation1970). The Minhocão as political violence later became a cinematic trope (Pinazza and Bayman Citation2013). However, late 1960s São Paulo was also an emerging consumer society, and its roads were designed to appeal to an increasingly well off, numerous, and mobile middle class, as well as the automobile-industrial complex (Bastos Citation2003; Lagonegro Citation2003, 18). As Eduardo Vasconcellos has written, the middle-class city and the automobile-oriented city were coterminous at this point in Brazil, the one the contemporary expression of the other. ‘The middle class and the automobile’, he wrote, ‘is the longest lasting and happiest marriage of our times’ (Vasconcellos Citation2001, 156). Therefore, the Minhocão at the time of its construction could be pitched as, and at the beginning at any rate, understood by middle-class Paulistas as, a humane intervention in the city’s fabric and a positive contribution to its public realm.

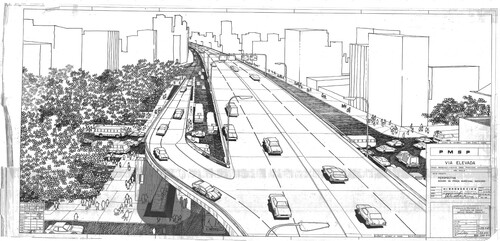

The Minhocão could therefore even be understood as something like a park. This perspective drawing (see ) of the Minhocão, dated 25 September 1969, was produced by the designers of the Minhocão, Hidroservice, then Brazil’s largest engineering firm, and one of the chief beneficiaries of government largesse. It depicts the Minhocão from above the roadway, looking westwards about halfway along the elevated section at the Praça Marechal Deodouro, whose greenery dominates the left-hand side of the images. It’s a relaxed, breezy scene, the traffic flowing easily on the empty highway, pedestrians ambling beneath. The city proper is a dense abstraction against which the Minhocão appears as relief. Here, implicitly, one can breathe. The drawing stretches the horizontal axis, increasing the (in reality, desperately narrow) gap between the roadway and the surrounding buildings. The Minhocão represented here isn’t an imposition, but of a piece with the existing landscape, reinforcing and extending its existing park-like qualities. The traffic and pedestrians are politely separated, but it is not as if they belong to alien worlds. The columns holding up the on-ramp form a kind of colonnade. In terms of ‘atmosphere’—leisurely, affluent, modern—this image is consistent with the later re-imagination of the Minhocão as park. The Parque Minhocão might therefore, somewhat unexpectedly, begin here.

Figure 2: Prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo, Elevado Costa e Silva, perspective drawing of the Praça Marechal Deodoro access, September 1969. Acervo de projetos da Superintendência de Projetos Viários—Secretaria de Serviços e Obras—PROJ 4. Reproduced with the permission of the Prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo.

The Hidroservice image was one of a dozen or so perspective drawings representing the Minhocão in the same terms. Highly rhetorical, they help to occlude the fact that Hidroservice did no preparatory studies whatsoever of the effect of the highway on its surroundings (Florence Citation2020, 360). But there is in fact other evidence to support the reading of Minhocão as public space, including a feature in the colour news magazine Manchete, in an issue celebrating São Paulo’s growth on the 417th year of its founding; the Minhocão was opened to coincide with the founding day on 24 January. The image is striking to say the least: the headline reads, with no trace of irony, ‘Towards a More Humane City’, laid over an image of the Praça Roosevelt under construction, the eastern terminus of the Minhocão. It’s an extraordinary image of a city in tumult; residential towers rise everywhere, dwarfing the 19th-century church of Nossa Senhora da Consolação in the foreground, while in the middle the Praça Roosevelt emerges already half-ruined. But the image nevertheless embodied the idea that the expressways might bring with them civilised public space, at least if they were finished (Manchete Citation1971). And in its reportage of the inauguration, the Folha de São Paulo printed an aerial photograph of the Minhocão that showed a crowd occupying its entire length, an uncanny prefiguration of its later existence at weekends. In concept if not realisation, the early Minhocão was legible—to some at any rate—as public space (Folha de São Paulo Citation1971).

This reading of the Minhocão would be consistent with the views of prominent international architects and designers of the time. For the English architectural historian and critic Reyner Banham (Citation1971, 213), the expressway was perfectly capable of being public space, as (based on somewhat anecdotal evidence) he wrote of Los Angeles’s freeways. His thinking broadly aligned with that of the planner Peter Hall, and the architects Peter and Alison Smithson, with whom he had been associated in London (Hall Citation1969; Smithson and Smithson Citation1970). In the United States, landscape architects such as Lawrence Halprin (Citation1966) thought sympathetically designed expressways might be significant additions to the public realm, rather than erosions of it. The Minhocão, at least in this image, can be aligned with an international consensus—it could be, in concept at least, a kind of public space.

Needless to say, the park concept did not survive contact with reality. The Estado de São Paulo had already complained at length of the destruction of the Avenida São João. On the day of inauguration, a Volkswagen Fusca broke down on an eastbound lane, bringing the entire expressway to a standstill. ‘The congestion has already started’, reported the Estado de São Paulo (Citation1970, Citation1971) somewhat wearily. A classic story of technology’s capacity for self-sabotage, had it not occurred, one senses that it would have to have been staged. The ensuing reportage of the Minhocão through the 1970s depicted it as São Paulo’s most accident-prone road, the site of spectacular and sometimes surreal accidents, with regular calls for its closure or even demolition (Folha de São Paulo Citation1976a, Citationb).

The image of the Parque Minhocão

Whatever the reality of the Minhocão, the presence of park-like imagery in the early designs is important, indicative of more continuity between past and present than is generally assumed. The process of creating the present-day Parque Minhocão was nevertheless drawn-out. It is partly down to a series of legal closures, not all related, firstly in January 1977, when under pressure from a well-organised group of sleepless residents it closed from midnight until 5 a.m. (Folha de São Paulo Citation1976b; Rodrigues Citation2017). Further closures occurred in 1990 when traffic was barred on Sundays and public holidays for the same reasons, and a guard rail installed, a structural recognition for the first time of the needs of pedestrians (Rodrigues Citation2017). Closure the whole weekend including Saturdays started in 2018 (Comolatti Citation2022). There has never been a consistent project of closure, however, and its architectural re-imagining has always been a parallel and fragmentary process.

The first major architectural proposal to re-imagining of the Minhocão emerged in 1987 in a scheme by a local architect, Pitanga do Amparo, who sketched the Minhocão semi-transformed into a park (Amparo Citation1987; Rodrigues Citation2017). Its inside lanes were given over to electric trolleybuses, cars having been banned; the other lanes became parkland, with gangways to new shops at gallery level, street cafés, and luxuriant planting. The then mayor of the city (and former President), Jânio Quadros, apparently looked at the sketches, but did not take them further (Amparo Citation1987; Rodrigues Citation2017).

Amparo’s scheme, in retrospect, was an outlier at the time. It was nearly 20 years before anything similar was attempted, in this case the results of a design competition held by the municipality of São Paulo, the Prêmio Prestes Maia de Urbanismo, named after Francisco Prestes Maia, a former mayor and by profession a planner. The winning entry by José Alves and Juliana Corradini, re-imagined the Minhocão as a linear park enclosing the roadway in a tunnel (Artigas, Mello, and Castro Citation2008, 92–100). At roadway level the architects envisaged art galleries in steel and glass, cantilevered beyond the existing road boundary (they would, curiously, have brought the structure into unimaginable proximity with the adjacent apartment buildings). In the section drawings for the design, children play, a man works on a laptop, cyclists cycle, balloon sellers sell balloons. A vision of a leisurely and polite urban order, it indicated a profound change in approach to the Minhocão: not only could it now be rendered as place, it could also be civilised. The cars might have been tamed, but (to invoke Vasconcellos momentarily) it was every bit as middle class a space as the original design. The Parque Minhocão always existed at some level—it just needed to be brought back. It was, as Kelly Yamashita (Citation2019) described, evidence of a ‘strange preservationism’ (35).

That ‘strange preservationism’ reached its peak in 2013 with the creation of the Associação Parque Minhocão (APM) formed by a local businessman, Athos Comolatti, and others including an architect, Felipe Rodrigues. Comolatti (Citation2022) had seen the High Line—an immensely popular public park made out of a converted overhead rail line—while on holiday in New York and had wondered if something similar might be possible in São Paulo. The APM’s headquarters in a flat overlooking the Minhocão housed an exhibition about the High Line as part of the 2013 iteration of the São Paulo architecture Biennial, meant (according to its authors) as ‘inspiration’ rather than ‘literal proposal’ (Associação Parque Minhocão Citation2013). On the wall, there was also as well a short, handwritten text by Rodrigues, ‘O que é a Associação Parque Minhocão’ (‘What is the Minhocão Park Association?’), which speaks of the ‘violence’ of the Minhocão, of its ‘tearing apart’ the urban fabric, and the proposed park would ‘completely changing the panorama of the centre of the city’ (Comolatti Citation2022; Rodrigues Citation2013) (see ).Footnote1

The flat also showed a handful of architectural capriccios of a remade Minhocão by Ciro Miguel, an architect specialising in fantastic photomontages mixing contemporary Paulista urbanism with historical monuments (his remarkable Impossible Landscapes were exhibited elsewhere in the Biennial). In the most striking of the images made for the APM, he depicts the Minhocão at the iconic point at which it joins the Avenida São João on its way to Barra Funda: the triangular, green flatiron-like building housing the APM fills the right-hand side of the image, but turned into a hotel. In the foreground, in what is seemingly in a literal illustration of the Situationist International slogan ‘Sous Les Pavés, La Plage’, the roadway has been scraped back to reveal a beach, populated by bikini models. Just to their right, a family of cyclists emerge from behind vegetation on a bike path. The beach extends seemingly endlessly towards Barra Funda, dotted with colourful umbrellas and sunbathers. With its supernaturally intense colours and cloudless sky, it has a hyperreal quality consistent with Miguel’s other landscape work. It also treads a fine line between description and absurdity; like early Pop collages, this one makes everyday life into a theatre of the absurd, but one in which we are all in on the joke. It was an APM commission, and Miguel (Citation2023) acted under their instructions, adding and emphasising elements where he was required. Its playful surrealism is nevertheless consistent both with his work of the time, and what the APM needed at this stage, a playful provocation without too much commitment. It is also in itself iconic, perhaps the best known, and most widely reproduced, of the Minhocão beach images. Alongside the exhibition there were events including talks by the High Line’s founders Robert Hammond and Joshua David (Deudoro Citation2013). Meanwhile other parts of the Biennial touched on the Minhocão’s present and future, including a film Carrópolis (Monolíto Citation2013). The year 2013 was, Miguel (Citation2023) noted later, ‘Peak Minhocão’.

In large part as a result of this activism, the desire to create the Parque Minhocão became official in 2014 in a law enshrining the gradual deactivation of the expressway and the creation of a park in its place (Diário Oficial Citation2014, 18). A further law in 2016 gave the name of the Parque Minhocão to the highway during its periodic closures, along with another unrelated one renaming it as the Elevado João Goulart after the left-wing Brazilian president deposed by the 1964 military coup. Then in 2018, a law was passed for the creation of a permanent park of the same time (Prefeitura de São Paulo Citation2018). It was rescinded the following year on a technicality, but the project undoubtedly had momentum, enough to get the interest of Jaime Lerner’s major architectural practice who produced speculative images of their version of the park in 2017, even more archly surreal than Ciro Miguel’s (Galani Citation2019). The Parque Minhocão itself closed during the covid-19 pandemic between 2020 and 2022, but re-emerged with new furniture, washrooms, and (reflecting the demographic of the surrounding neighbourhood) an unambiguously pro-LGBTQI+ identity.

The actual Parque Minhocão

It is easy, and tempting, to read the creation of the APM as a straightforward gentrification project, although its authors have all in different ways denied this is the case (Comolatti Citation2022; Morozini Citation2022; Rodrigues Citation2017). For the APM’s critics, the invocation of the High Line in 2013 was enough to suggest gentrification, that project having been the focus of the most intense property speculation in lower Manhattan in recent years, as well as becoming one of the city’s most popular tourist attractions with over eight million visitors per year (the High Line is also key evidence in David Madden’s (Citation2017) critique of new public spaces. The images produced of a future park for the APM do little to dispel that worry, and even more so those however alluring they might be. Miguel’s Minhocão beach of 2013 is a brilliant image, but it also depicts, following APM’s instructions, a somewhat exclusive space.

The actual Parque Minhocão is arguably something else. There is evidence from 2006 in the form of a remarkable documentary film by Maíra Bühler, Paolo Pastorelo, and João Sodré, two of whom (Pastorelo and Sodré) were recent graduates of the Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism at the University of São Paulo. Elevado 3.5 represented little of the Minhocão’s structure, except for the hypnotic opening sequence, and another filmed from a passenger’s perspective from inside of a taxi cab. Apart from these moments, it focused instead on the lives of 20 residents in and around the Minhocão, from a bankrupt former gambler, living alone in a tiny room, to a glamorous trans woman, a retired political activist, a cobbler, an artist, and a clairvoyant. The film did something important: it represented the Minhocão as place, somewhere with history and association, produced by its inhabitants. Some of this place was private and intimate, but much of it not. A surprising number of residents were openly enthusiastic about it; none wanted it demolished, even though the Minhocão of their depiction was often run down and unsafe. Two of its subjects described how graffiti artists routinely scaled their apartment block; another building was a ‘fortress’ against crime, so difficult to enter, it once forestalled the military police. The Minhocão of Elevado 3.5 was certainly tough. It might be argued that the film performed a similar function for the Minhocão as Joel Sternfeld’s photographs from 2000 did for New York’s High Line, rendering it as an authentic place in the first stage of a process of rehabilitation. Perhaps. But Elevado 3.5 also depicted an alternative Minhocão produced by its inhabitants through innumerable small acts of resistance, a community (albeit an eccentric one) not easily recuperable by the market. Consciously, it seems, it avoided the spectacular image-making characteristic of the APM.

That version of the Minhocão saw physical realisation in an immensely popular screening in 2010 of Elevado 3.5 on the roadway itself, an event that both celebrated the film and the place (Florence Citation2010). And a similarly alternative Minhocão could be found in the artist Rosa Barba’s 2016 documentary Disseminate and Hold, which celebrated the daily transformation of the Minhocão from highway to park, in so doing recognising its inherent contradictions, as well as the difficulties of its history (Barba Citation2016; Farago Citation2016). In the same spirit is an academic project, the ‘Inventário Participativo’ (‘Participatory Inventory’) project by two University of São Paulo geographers, Simone Scifoni and Mariana Nito, which maps the cultural and community organisations of the Minhocão area, and which describes a complex place produced by different constituencies; the Parque Minhocão they regard as a gentrification project that serves the interests of developers rather than the existing residents of the area. Architects, they complain, have been complicit—they ‘always have to intervene’, implicitly in the service of the market (Nito and Scifoni Citation2017, Citation2018, Citation2022).

There is therefore a case for the actual Parque Minhocão. The project as envisaged by the APM in 2013 has yet to come into being, and even its authors recognise opposition to it, and imagine only slow progress towards that goal (Comolatti Citation2022; Rodrigues Citation2017). The actually existing Parque Minhocão remains compelling for many observers precisely because it remains unresolved, and is often under threat—in 2022 there was an attempt, one of many over the years, to roll back the hours of the nocturnal park on weeknights in favour of the motorist (Câmera Municipal de São Paulo Citation2022). At the same time, as a complex, multi-authored process, it holds diverse and contradictory interests in balance. The actual Parque Minhocão might include the legally defined entity that operates at night and at weekends with its security guards and washrooms, giant chessboards and astroturf. It might also be said to include everything else that happens in the area defined by the Minhocão, including the 3-km-long undercroft beneath the roadway with its 85 concrete piers, another world, mostly absent from architectural visualisations. Here are bus stops, cycle paths, junk shops, bars, the odd construction site, a fluctuating homeless population. The actual Minhocão also represents the results of opinion polls carried out by the APM themselves in recent years, which indicate a substantial majority, around 55%, in favour of the uneasy status quo (Comolatti Citation2022). That status quo undoubtedly reproduces in miniature the vast inequalities of the surrounding city, not least the ongoing situation as regards the homeless. The security guards on the upper level at weekends work hard to keep the upper and lower worlds apart, as is well known to all users. But the actual Parque Minhocão, for all its difficulties, may still be preferable to the architectural Parque Minhocão, in which seemingly only the young and beautiful are admitted.

Acknowledgements

The Leverhulme Trust provided an International Research Fellowship in 2022 enabling the research for this paper. I would like to thank Rosa Barba, Jens Baumgarten, Athos Comolatti, Luiz Florence, José Lira, Ciro Miguel, Felipe Morozini, Mariana Nito, João Sodré, Simone Scifoni, and Guillerme Wisnik for their assistance at different stages.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Richard J. Williams

Richard J. Williams is Professor of Contemporary Visual Cultures, University of Edinburgh. Email: [email protected]

Notes

1 The wall text was still there in 2022.

References

- Amparo, Pitanga do. 1987. “Uma solução para o elevado.” Jornal da Tarde. 29 September.

- Artigas, Rosa, Joana Mello, and Ana Claudia Castro, eds. 2008. Caminhos do elevado: memória e projetos. São Paulo: IMESP .

- Associação Parque Minhocão. 2013. “Modos de Negociar .” Monolito 17: 118–119.

- Augé, Marc. 1996. Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London: Verso .

- Banham, Reyner. 1971. Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies. London: Penguin .

- Barba, Rosa, dir. 2016. Disseminate and Hold, 2016, Foundation Prince Pierre de Monaco, 21 min.

- Bastos, Maria Alice Junqueira. 2003. Pós-Brasília: Rumos da Arquitetura Brasileira. São Paulo: Editora Perspectiva .

- Berman, Marshall. 1983. All That is Solid Melts Into Air: The Experience of Modernity. London: Verso .

- Bühler, Maíra, Paulo Pastorelo and João Sodré, dir. 2007. Elevado 3.5, Primo Filmes/TV Cultura, 2007, 1 hr., 15 min.

- Caldeira, Teresa P. R. 2000. City of Walls: Crime, Segregation and Citizenship in São Paulo. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press .

- Câmera Municipal de São Paulo. 2016. “Notícias: Prefeitura sanciona lei que cria o parque minhocão.” March 10. https://www.saopaulo.sp.leg.br/blog/prefeitura-sanciona-lei-que-cria-o-parque-minhocao/.

- Câmera Municipal de São Paulo. 2022. “Alteração do período de fechamento do Minhocão recebe aval da Comissão de Administração Pública.” October 19. https://www.saopaulo.sp.leg.br/blog/alteracao-do-periodo-de-fechamento-do-minhocao-recebe-aval-da-comissao-de-administracao-publica/.

- Comolatti, Athos. 2022. Interview with the author. April 5.

- Cordeiro, Janaina Martins. 2009. “Anos de chumbo ou anos de ouro?A memória social sobre o governo Médici .” Estudos Históricos (Rio de Janeiro) 22 (43), June: 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-21862009000100005

- Davis, Mike. 1990. City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles. London: Verso .

- Degen, Monica, Clare Melhuish, and Gillian Rose. 2015. “Producing Place Atmospheres Digitally: Architecture, Digital Visualisation Practices and the Experience Economy .” Journal of Consumer Culture 17 (1): 3–24.

- Deudoro, Juliana. 2013. “O Minhocão pode se transformar em uma gentileza para São Paulo.” Veja São Paulo. September 24. https://vejasp.abril.com.br/cidades/robert-hammond-high-line-sao-paulo.

- Diário Oficial, Cidade de São Paulo. 2014. 140. August 1. Leia mais em: https://vejasp.abril.com.br/cidades/robert-hammond-high-line-sao-paulo.

- DiMento, Joseph, and Cliff Ellis. 2013. Changing Lanes: Visions and Histories of Urban Freeways. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press .

- Estado de São Paulo. 1970. “Elevado, O Triste Futuro da Avendida.” December 1: 23.

- Estado de São Paulo. 1971. “Minhocão Aberto, Sem Repercussão Esperada.” January 26: 16.

- Farago, Jason. 2016. “Rosa Barba Examines the Everyday Chaos of São Paulo's ‘Giant Earthworm’ Highway.” Guardian. September 20, 2016. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/sep/20/rosa-barba-sao-paulo-biennial-disseminate-and-hold-film

- Florence, Luiz Ricardo. 2010. “Estréia documentário ‘Elevado 3.5’.” Vitruvius. 032. 03. June. https://vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/drops/10 .032/3441.

- Florence, Luiz R. 2020. “Arquitetura e Autopia: Infraestrutura Rodoviária em São Paulo 1952-1972 .” PhD thesis, University of São Paulo, Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism .

- Folha De São Paulo. 1971. “Cidade Recebeu A Via Elevada.” January 25.

- Folha De São Paulo. 1976a. “Rota 120 metralha e fere cuatro jovenes.” September 8: 12.

- Folha de São Paulo. 1976b. “DSV fecha o elevado durante a madrugada.” December 30. 14.

- Galani, Luan. 2019. “Jaime Lerner comandará transformação do Minhocão em parque suspenso.” Gazeta do Povo. February 26. https://www.gazetadopovo.com.br/haus/urbanismo/minhocao-sao-paulo-jaime-lerner-parque-linear-pedestres/.

- Gorizio, Federichi. 1971. Letter. Folha de São Paulo, February 16: 4.

- Hall, Peter. 1969. London 2000. 2nd ed. London: Faber and Faber .

- Halprin, Lawrence. 1966. Freeways. New York: Reinhold .

- Harvey, David. 1990. Spaces of Hope. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press .

- Hochuli, Alex. 2020. “The Minhocão Highway of São Paulo: Living with the Big Worm.” Domus, 1044, 12 March.

- Lagonegro, M. A. 2003. “Metrópole sem metrô: transporte público, rodoviarismo e populismo em São Paulo (1955-1965) .” PhD thesis, University of São Paulo .

- Leadbetter, Russell. 2023. “M8 in Glasgow: Should it be Scapped?” Herald. April 16. https://www.heraldscotland.com/news/23453466.m8-glasgow-scrapped/.

- Levi-Strauss, Claude. 1955 trans. 1973. Tristes Tropiques. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Levy, Wilson. 2015. “Parque Minhocão: Cidade e democracia: novas perspectivas, Vitruvius (February 2015).” https://vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/minhacidade/14.175/5431.

- Machado, Gisele. 2015. “Minhocão Volta a Pauta.” Revista Apartes - Câmara Municipal de São Paulo. November – December: 36-8.

- Madden, David. 2010, June. “Revisiting the End of Public Space: Assembling the Public in an Urban Park .” City and Community 9 (2): 187–207.

- Madden, David. 2017. “The Contradictions of Urban Public Space: The View from London and New York.” In The SAGE Handbook of the 21st Century City, 535–551. London: Sage .

- Manchete. 1971. “Retrato de São Paulo” (special issue). Manchete, January 25.

- Maulf, Paulo. 1969. “Official Announcement of the Construction of the Minhocão.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = j44cTNnDHps.

- Miguel, Ciro. 2023. Interview with the Author. September 29.

- Millington, Nate. 2017. “Public Space and Terrain Vague on São Paulo’s Minhocão.” In Deconstructing the High Line, edited by Christoph Lindner, and Brian Rosa, 201–218. New Brunswick: Rutgers .

- Monolíto. 2013. “Carrópolis.” 17. 40–4.

- Morozini, Felipe. 2022. Interview with the Author. March 17.

- Nito, Mariana da Silva and Simone Scifoni. 2017. “O Patrimônio Contra a Gentrificação: A Experiência do Inventário Participativo de Referências Culturais do Minhocão .” Revista do Centro da Pesquisa e Formação 5 (November 2017): 82–94.

- Nito, Mariana Da Silva, and Simone Scifoni. 2018. “Ativismo urbano e patrimônio cultural .” Arq Urb 23: 82–94.

- Nito, Mariana Da Silva, and Simone Scifoni. 2022. Interview with the author. April 1.

- Pinazza, Natalia, and Louis Bayman. 2013. World Film Locations: São Paulo. Bristol: Intellect .

- Prefeitura de São Paulo. 2006. Lei Cidade Limpa. Lei n° 14.223. September 26.

- Prefeitura de São Paulo. 2017. “Notícias: Museu de Arte de Rua terá intervenções artísticas em todas as regiões da cidade.” March 10. https://www.capital.sp.gov.br/noticia/museu-de-arte-de-rua-tera-intervencoes-artisticas-em-todas-as-regioes-da-cidade.

- Prefeitura de São Paulo. 2018. Lei N° 16.833. February 7. https://legislacao.prefeitura.sp.gov.br/leis/lei-16833-de-7-de-fevereiro-de-2018.

- Prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo. 1968. Lei no. 7.113. January 11.

- Prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo. 1969. Lei no. 7.386. November 19.

- Rodrigues, Felipe S. S. 2013. “O que é a Associação Parque Minhocão?” Wall text, Associação Parque Minhocão headquarters.

- Rodrigues, Felipe S. S. 2017. “Razões do Parque Minhocão.”Arquitextos. 209.05. October 2017. https://vitruvius.com.br/revistas/read/arquitextos/18.209/6751.

- Rogers, Richard. 1997. Cities for a Small Planet. London: Faber and Faber .

- Sennett, Richard. 1977. The Fall of Public Man. New York: Knopf .

- Senra, Ricardo. 2014. “Após proibição, prefeitura autoriza piscina olímpica no Minhocão.” Folha de São Paulo. March 20.

- Smithson, Alison, and Peter Smithson. 1970. Ordinariness and Light. London: Faber and Faber .

- Souza, Marcelo Lopes de. 2008. Fobópole: o medo generalizado e a militarização da questão urbana. Rio de Janeiro: Bertrand de Brasil .

- Van Mead, Nick. 2017. “Taming ‘the Worm': How the Minhocão is São Paulo's Soul.” Guardian. December 1.

- Vasconcellos, Eduardo Alcantara. 2001. Urban Transport, Environment and Equity: The Case for Developing Countries. London: Earthscan .

- Wisnik, Guilherme. 2012. “Dentro do Nevoeiro: diálogos cruzadas entre arte e arquitetura contemporânea .” PhD thesis, University of São Paulo , Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism.

- Yamashita, K. M. 2019. “Minhocão: Via de Práticas Culturais e Ativismo Urbano .” (PhD thesis). University of São Paulo , São Carlos.