Abstract

This paper examines the planning process behind the construction of a mosque building in the English city of York, to demonstrate how it is entangled with contested ideas of national identity. We argue that the politics of religious architecture, particularly mosque planning and architecture, serve as a litmus test for the ways multiculturalism is experienced in contemporary Britain. We explore objections during the planning process for this mosque alongside letters to a local newspaper, where objections included the effect of the mosque on urban infrastructure, the symbolic identity of the mosque within the wider city, and how the mosque would affect claims to citizenship more widely. Objections to this mosque application indicate that architecture and the urban environment are core elements of national identity, and it is through the planning process (of religious buildings) that claims about ‘who is a citizen’ are articulated. Democratic planning processes around the construction of individual buildings can allow groups to organise resistance to much wider cultures of multiculturalism and act as platforms for Islamophobic sentiments. We argue that planning processes work as discursive registers through which architectural aesthetics, cultural identities and fears of otherness are wrapped into the wider politics of public space.

Introduction

The idea of British citizenship has always harboured an inherent paradox, torn as it is between being an exclusionary privilege for some, granted on the basis of identifications with empire and a homogeneous culture, and, for others, shorthand for a more capacious understanding that figures people from diverse ethnic, racial and religious backgrounds contributing to a plural socio-political landscape. Given how its particular history of multiculturalism is bound up with longer histories of imperialism, migration, and racism, the UK provides a useful case study for understanding the complexities and conflicts inherent in contemporary forms of citizenship (Modood Citation2013). Moreover, a focus on the urban dynamics of citizenship in the UK offers an opportunity to trace place-based loyalties as they arise in contemporary conflicts about who has the right to shape the future city. In particular, in this paper we will offer a case study of how questions of architectural design intersect with disputes over everyday urban infrastructures (road networks, terraced housing, parking spaces, and the like), and how these get amplified into larger symbolic questions of community, as well as nativist accounts of national identity (Amin Citation2007; Citation2023).

An existing body of research has demonstrated the interrelationship between citizenship and claims over urban space, both from above and from below (Holston and Appadurai Citation1996; Painter and Philo Citation1995; Staeheli Citation2003), with the city acting as a broker in mediating shared ideas of belonging (Anjaria Citation2009; Holston Citation2009; Van Eijk Citation2009; Yardımcı Citation2023). The city is argued to mediate complex processes of negotiating identity and belonging at a much wider scale, as people frame their claims over a particular piece of urban land and/or architecture through claiming to be ‘civilised’, ‘native’/‘indigenous’ citizens, all of which imply notions of deservingness. These studies mostly focus on metropolitan urban environments in different parts of the world with significant levels of ethnic or cultural minority presence and deprivation. However, a subset of studies explores the intersecting politics of citizenship and urban space, using religious architecture to do so; studies with a particular focus on mosques within the UK context have discussed how tensions around these buildings contribute to the construction of boundaries between insider/outsider (Gale Citation2004; Citation2005) and English and non-English others (Villis and Hebing Citation2014).

This paper dwells on the importance of urban space as a medium of redefining feelings of national belonging and citizenship, and follows the path of scholarship focusing on the politics of Islamic architecture (DeHanas and Pieri Citation2011; Gale Citation2004; Citation2005). By interrogating concerns raised about the place of mosques within contemporary cities, we connect with wider arguments on the importance of understanding architecture as a quilting point for all manner of political pressure points (Latour and Yaneva Citation2008), and urban infrastructure as means to re-animate understandings of community, via the agency of the everyday material artefacts that shape our environments (Amin Citation2007; Citation2008). We aim to contribute to these debates by providing a timely analysis of how minority-majority relations play out in an urban setting within a wider political context shaped by a failing multiculturalism, which is characterised in the UK by its ‘strange non-death’ as a policy tool (Modood Citation2013) and manifested in the path that led to Brexit and the ongoing hostile environment. To do that we turn our gaze to the underexplored Northern English city of York. Being a cathedral city with relatively low levels of deprivation, York provides a unique case study that offers new insights into the ways citizenship is currently articulated, through the planning process, in a small UK city that swings between celebrating diversity and more rigid ideas around national identity, with Christianity still being an important marker of belonging in nativist discourses.

Changing trajectories of citizenship in the UK

Citizenship has always been a broader concept than the juridical status of individuals within a territorial state; it comprises sociological as well as legal dimensions (Isin and Wood Citation1999). Citizenship indicates a status in the sense of value, worth and honour which is not secured by officially acquiring membership citizenship, but, rather, the entry to a community of value which is defined in explicitly normative ways (Anderson Citation2012). As Yuval-Davis (Citation2006) reminds us, entitlements are constructed around the question of who ‘belongs’ and who does not, and what are the minimum common grounds—in terms of origin, culture and normative behaviour—that are required to signify belonging (Yuval-Davis Citation2006, 207). This suggests a complex relationship between citizenship, territory and political identity. The meaning of membership is defined in explicitly normative ways that go beyond conventional, legal—formal citizenship status, implying models of virtuous and deviant citizens, favouring particular subject-citizens over others, and suggesting ways to transform the latter into the former (De Koning, Jaffe, and Koster Citation2015, 121). This means that citizenship is partial, varied, and geographically contextual, in the sense that different individuals and groups within a single territorial boundary may enjoy differentiated rights and senses of belonging.

Ideas of citizenship in the UK have developed in conjunction with immigration from the beginning, often racializing and deeming certain ethnic, racial, and later religious (particularly non-Christian) communities as unfit to belong in the nation. Initially, British citizenship was rooted in redistributive ideals around the welfare state, social rights, and class equality, influenced by the liberal welfarism that predominated after the Second World War, but gradually became disconnected to these (Tyler Citation2010, 62). In the aftermath of the second world war, the UK faced a labour shortage to respond to, which enacted the 1948 Nationality Act and gave all Commonwealth citizens the right to settle, work and vote in the UK. The following waves of postcolonial immigration did help rebuild the labour force, while rupturing former ideals of citizenship due to the political mobilisation of reactionary views on immigration throughout the 1960s. As a result, the Immigration Act 1971 removed the citizenship status of the Commonwealth residents, bringing the onus to those who had come to Britain to prove their right to stay in ways that paved the way for the Windrush scandal (University of Birmingham Library Services Citation2024). A key marker of the growing white racism in the UK was the 1981 Nationality Act which further restricted immigration to the British Isles, by introducing the requirement for Commonwealth citizens who had settled in the UK to register to become British citizens. Tyler argues that whilst race and ethnicity were never directly named, the 1981 Act effectively designed citizenship so as to exclude black and Asian populations in the Commonwealth while positively discriminating for white nationals born within the boundaries of the empire, which, she interprets, has embedded racism in British citizenship (Citation2010, 63).

The 1990s witnessed a dual strategy that aimed to restrict immigration to the UK and introduce visa controls, while at the same time advancing integration as part of a wider multiculturalist political agenda. In the immediate aftermath of its massive election victory in May 1997, New Labour was keen to present a commitment to embracing diversity and valuing cultural mix, before shifting away from that position following the 2001 riots in the Northern English cities of Bradford, Burnley, Leeds, and Oldham (Back et al. Citation2002, 446). The claims raised by the South Asian populations over their recognition as fully-fledged citizens of a multi-ethnic and multicultural society (Amin Citation2003) changed the tone of the public debates on immigration, alarming a widespread moralising about what it takes to be British (Amin Citation2002, 959). Official analysis saw the root cause in each town as the estrangement of two communities (white and non-white) (Thomas Citation2008, 10). There followed a strategy of community integration and social cohesion (Kundnani Citation2002), which was centred on an emphasis of a shared set of civic values associated with Britishness such as ‘openness’ and ‘tolerance’ implicitly over diverse cultural identities (Commission for Integration and Cohesion Citation2007, 14). The governmental (and media) anxiety over ‘parallel lives’ (Cantle Report Citation2001, 9) heightened in the wake of the activities in British cities of English-born bombers professing Islamic beliefs (Thomas Citation2008, 10). The New Labour government’s commitment to ‘manage diversity’ (Back et al. Citation2002, 446) continued to be adjusted over the years. The subsequent Conservative-Liberal Democrat coalition distanced itself further from the goals of diversity, with the former Prime Minister David Cameron rejecting the ‘passive tolerance of recent years’ in favour of ‘much more active, muscular liberalism’ in a speech delivered on the same day that the English Defence League held its biggest ever demonstration, in Luton (Wintour Citation2011).

The resulting history of community relations in the UK has echoed a wider ‘reigning in the boundaries of tolerance’, with the governance of plurality within contemporary societies ‘through order and discipline, in short, the abandonment of multiculturalism’ (Amin Citation2012, 61). By multiculturalism, we mean the ‘the recognition of group difference within the public sphere of laws, policies, democratic discourses and the terms of a shared citizenship and national identity’ (Modood Citation2013, 2), with a caveat. That is, rather than a shared sense of citizenship and national identity, a truer definition of actually-existing multiculturalism, certainly in the UK, would capture a sense of ‘differentiated citizenship’ amongst ethnic groups, with some groups awarded greater rights than those enjoyed by others (Festenstein Citation2006, 3). In large part, this speaks to legacies within Western Europe of multiculturalism arising less from universalistic political philosophies and more from histories of migration that introduce ‘a kind of ethno-religious mix that is relatively unusual for those states’ (Modood Citation2013, 8). Despite helping manage a complex society through policies that aimed at addressing the needs of diverse communities and tackling racism, discrimination and inequality, contemporary discourses around multiculturalism have struggled to create cohesion and a sense of belonging among minority groups in the UK, especially within the broader context of pressures from austere and hostile socio-political atmospheres. Multicultural discourses have rubbed up against the anxieties and fears of the supposed majority population, fostered through populist political and media narratives about the presence of ‘undeserving others’ amidst increasingly austere resources. Against this backdrop, and with particular respect to rising anxieties around home-grown terrorists in the UK and how ‘non-violent Muslim groups are ambiguous about British values such as equality between sexes, democracy and integration’ (Wintour Citation2011), British multiculturalism has apparently buckled under various Muslim-related pressures (Meer and Modood Citation2009). The figure of the Muslim has emerged as the key problem category on Britain’s racial and ethnic landscape, with new fears emerging around the visibility of symbols such as the veil and the minaret (Hussain Citation2014, 624).

These political discourses set the context for planning processes around new religious buildings in the UK, and so we argue that the politics of mosque planning and architecture serve as a litmus test for the ways multiculturalism is experienced today. As Thomas (Citation2008, 2) argues, the planning system is the arena within which struggles take place over whether and how the environment might reflect a dynamic cultural mix. Within a highly charged political atmosphere in which allegiance to a vague sense of Britishness ventriloquised white racism making inroads into mainstream politics, alongside ongoing racial tensions and urban disturbances, ‘the task of trying to promote race equality within and through planning’ (Thomas Citation2008, 2) has always been a double-edged sword. As changing conceptions of the national community are entangled with the ways in which diversity and difference has been managed by urban policy and planning (Fincher et al. Citation2014, 5), we look at community responses to the planning applications of a mosque in York, proposed to replace a smaller mosque on the same site. We will show below how urban architecture can hit raw nerves in contested claims to national belonging, as a mechanism to articulate more primary assertions of who has a right to own city space—and related to that—to belong in the wider political community.

Politics of mosque architecture and the case of York

The recent history of religious buildings in European cities reveals the depth of tension over cultural identity between different communities, with purpose-built mosques especially controversial because of their ‘visibility, religious symbolism, and claim to public space’ (DeHanas and Pieri Citation2011, 800). Saleem has argued how, by virtue of its pronounced place as a public space, the purpose-built mosque has ‘come to symbolise Muslim presence in Britain’, especially in Northern English cities (Citation2018, 3). Until the 1960s, mosques in the UK were most often conversions of existing domestic, public or other religious buildings, and they developed as grassroots community projects, connected to social identities of Muslim communities often living in the most economically marginalised areas of their cities. For Villis and Hebing, a mosque is ‘not only a physical site for the location of an Islamic community but also an important space for rehearsing and voicing questions of culture and identity’ (Citation2014, 416). As such, the planning, approval, and construction of mosques must be understood within the complexities and tensions of an urban politics of ‘public recognition’ (Fincher et al. Citation2014, 39), bringing into sharp relief the claims of different groups on public space.

As Batuman rightly notes, it is the city where the conflicts and struggles related to the practices and public representations of Islam (and religion in general) take place (Citation2021, 1, emphasis original). Religious architecture in Britain is dominated by Christianity, whose emergence dates back to as early as the 7th century. Although previous research has found that mosque construction within Britain has been less contentious than elsewhere in Europe (Ahmed, Dwyer, and Gilbert Citation2020), there have been significant points of conflict. At times, these points of conflict are charged because planning decisions on individual mosques get wrapped up within larger urban processes and immediate political controversies (DeHanas and Pieri Citation2011). At other times, points of conflict accumulate over longer periods of unequal treatment, as in local councils’ higher rates of planning refusals for mosques by comparison to Christian buildings (Gale Citation2005). When mosques have been approved and built, there are significant differences in how they have been located within their cities, with a longer history of cities hiding their mosques, displacing them from central routes and sites, than there is of cities celebrating and embracing mosques as landmarks and statements of civic pride (Peach and Gale Citation2003). Even in the case of mosques celebrated for their architectural designs, such as the recently completed Cambridge mosque (Arslan Citation2019), a review of public discourses surrounding their planning reveals the unease felt by many residents in the city and surrounding region about its construction (Villis and Hebing Citation2014).

With some exceptions (Villis and Hebing Citation2014), most existing scholarship on the planning of purpose-built mosques in the UK focuses on large cities (DeHanas and Pieri Citation2011; Gale Citation2004; Citation2005). In contrast, this paper focuses on York, as a small city in the north of England with a population slightly above 200,000, and with a historical identity tightly bound to the development of the Church of England. In 2021, 92.8% of York’s residents were white British, while 3.8% identified their ethnic group within the Asian category. It is predominantly Christian (95% of the population), whereas the Muslim population constitutes 1.2% of the population. Ranked as 12th least deprived on the Index of Multiple Deprivation and 6th least deprived on the domain of Crime out of 151 local districts in England in 2019, the city is strikingly different to the economic profiles of poorer towns and cities in the North of England with large Muslim populations, for whom their mosque plays a key role in their sense of belonging (Saleem Citation2018).

What makes the York Mosque such an interesting case study to explore is the central place the wider city occupies in national white geographies, with its Christian architectural and urban heritage dating back to the 10th century, its role as the ‘de facto capital of England’ in the 13th century and its later role as the Council of the North in Tudor England (Brooks Citation1954, 3), and as a historical seat of the established Church in the North of England. York’s Christian heritage is symbolised with the most celebrated individual building, York Minster, which is one of the largest Gothic cathedrals not only in England but in Northern Europe. The Minster was addressed as the ‘city’s signature building’ and a symbol of common identity in a recent report by the City Council (Citation2014, 42); indeed, the city draws on its built environment to such an extent in terms of its economic base that it can act as a barrier to developing in sustainable and socially just ways (Gill Citation2022), with the performative nature of a tourism strategy set on the preservation of its architectural core seen to be integral to underlying process of social exclusion in the city (Mordue Citation2005).

This makes York a unique case study through which to explore how Islamic architecture mediates negotiations around citizenship, and where boundaries are drawn in the tolerance of multiculturalism and difference in the city. The history of York’s Mosque speaks to the tensions that can arise when new religious architecture, built in response to rising numbers of faith communities from non-majority groups, is introduced to an urban environment with a large white British population. Moreover, the planning process for York Mosque came at a time when the numbers of purpose-built mosque buildings began to fall across the UK after decades of significant growth—and despite a rising Muslim population (Saleem Citation2018, 18). This confluence of counter-intuitive trends has led to concerns that planning regulations, permissions, and cultures are becoming more difficult for those wishing to build new mosques (Saleem Citation2018). Therefore, exploring the planning process for new purpose-built mosques such as the York building can offer a sense of where these planning difficulties lie, and whether the objections raised in response to new mosques speak to wider tensions in terms of multiculturalism, claims to citizenship, and the politics of public space.

Method and the case study

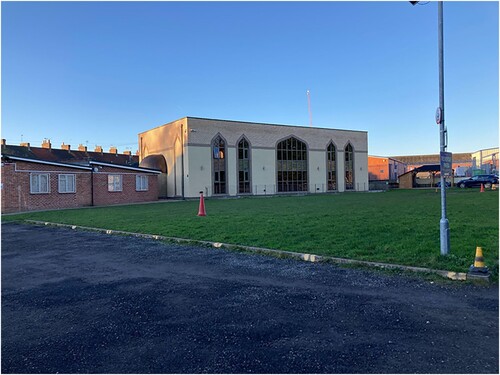

Our case study focuses on the planning applications for York Mosque and Islamic Centre (see ). The original design to substantively replace the existing small one-storey mosque was put forward for planning to York City Council in 2011, and included a central dome, two minarets, a prayer hall, and a series of community spaces including a classroom, library, community hall, and an accommodation block. This plan was subject to significant revisions through the planning process brought about by, inter alia, objections by the Environment Agency on the flooding risk the planned building might have on the surrounding area, concerns by local Police on the high risk of crime because of insufficient security features, and a concerted social media campaign amongst those who wanted to see planning permission refused (Stead Citation2011). The plan for a more modest building was finally approved by the city council in 2012, after which construction began in 2015, alongside fundraising campaigns. The building was formally opened in late 2018. It is located in Bull Lane, a narrow street less than one mile from York’s mediaeval walls towards the east of the city (see ). The mosque is immediately surrounded by a tightly knit Victorian terraces of two storey housing, and which retain a number of small businesses, such as garages and takeaway food premises. With respect to Peach and Gale’s typology of mosque buildings in England and their prominence within their wider cities (Citation2003), this mosque is somewhat hidden within the wider city, outside its city walls and tucked discreetly away from a large busy road. Although its location is a result of the decision to build on the site of the existing mosque, and the City Council was supportive of the mosque application in spite of many and varied objections, it is also the case that the building is muted within the wider place-marketing of the city, by comparison to how York trades on its Christian heritage.

Figure 1: York Mosque and Islamic Centre, including the original one storey, red-brick mosque building (Source: Daryl Martin).

After ethics approval by the University of York’s ELMPS committee, we undertook archival research of two sources: (1) public comments made on the multiple planning applications for the building, which were disclosed by the City of York council upon our Freedom of Information request; and (2) news and reader comments submitted to the two daily local newspapers, York Press and Yorkshire Evening Post concerning the mosque development from August 2011 (when the news about the York mosque opening its doors was first announced) to 2021. We read through each of the public comments, and put them into two separate files, namely ‘objection’ and ‘support’. There were more objections raised (52) than there were emails or statements of support (37). This trend was also repeated in the publicly printed letters to the York Press that we consulted. Then, we undertook thematic analysis in which we coded and analysed the comments that the local council had received in opposition to the proposed mosque development. The coding process was not comprehensive of the supportive comments, mainly due to the characteristics of the available data. Supportive comments pertaining to the mosque development were typically concise and lacked detailed explanations of their reasons for approval. More frequently, with letters to the local newspaper, these were responses to previously published objections, often addressing these objections point by point.

Although the objections did not achieve their desired outcome (i.e. to halt the construction of the mosque), they did have an impact on the planning process as the original proposal for a three storey building that included two minarets and a central dome was changed; the mosque was constructed without a dome or without symbolic minarets, and with the original one-storey building retained. By focusing on the planning objections as a particular kind of data that provides a glimpse into how individuals and communities raising these objections view the city and their place within the wider political community, we will show below how these platforms for objection and complaint can serve as an arena for the expression of racism and Islamophobia, disclosing a troubled relationship between narratives of nationhood and religious architecture.

When the objective is to object: the politics of mosque building

In what follows, we will consider the main themes arising from our analysis of objections raised by individual residents, businesses, and other stakeholders (sometimes outside the city) during the planning process for the mosque. These range from specific objections raised about the impact on the everyday spaces of the neighbourhood in which the mosque was located; critical comments about some of the symbolic aspects of the architectural design; and, objections indicating how the mosque was an architectural controversy (Yaneva Citation2012), filtered through Islamophobic discourses, racist narratives, and nativist claims to public space. In this way, our analysis offers an example of how architecture sits within wider urban infrastructures, pointing to how questions of design and the appropriations of the everyday material cultures of contemporary cities inform a wider politics of public space (Amin Citation2012). ‘A rematerialised urban sociology implies a different politics of urban community’, Amin has argued (Citation2007, 109); indeed, our case study demonstrates the significance of individual buildings, but also the wider urban networks they sit within, as being sites of dissensus as much as consensus (ibid.).

Urban infrastructures, and the everyday experience of the city

At first glance, a large number of objections were substantively unrelated to questions of religion, culture, and identity, and were rather more prosaic in character. These related to how the construction and functioning of the mosque would have an impact on the road network, noise levels, and property values in the surrounding area. In a wider sense, though, we see in this case study an illustration of the extended political role of ‘urban infrastructure (layout of public spaces, physical infrastructure, public services, technological and built environment, visual and symbolic culture) and its resonance as a “collective unconscious” working on civic feelings, including those towards the stranger’ (Amin Citation2012, 63). Certainly, we can see in this case study the working out of place-based urban politics away from the heavy symbolism of formal spaces of policy and power, and mobilised in fragmented ways in, and through, the ordinary spaces of the city (Amin Citation2007).

In the case of York’s mosque, repeated concerns were raised across the 52 objecting statements received by the local authority about the implications of an expanded mosque for traffic on the main access road. This road was wide enough for only single vehicles at any time (R13) and, on that basis, catastrophic scenarios were raised by some respondents: ‘If Fire Brigade access was required on a Friday lunchtime there would be a disaster’ (R23). This repeated objection to the unsuitability of the existing access road was linked to fears about especially heavy traffic use during religious festivals such as Eid and Ramadan (R33), and also noted with respect to fears about how ‘emergency services would react and cope with any incident when the new buildings were full to capacity’ (R31).

Concerns about road access led to related questions about parking on the site of the new mosque, with objections raised based on the expected noise and disruption due to the scaling up of the existing mosque capacity. For example, objections about parking escalated to concerns about the noise of increasing vehicular traffic and disruption to existing neighbours, which was echoed in objections raised by local business owners (R27). Residents from private households objected to levels of noise at night, because of the observance of religious customs of praying throughout the day: ‘there is continuous traffic coming to and from the Mosque and recently this has been continuous until 4.30 am in the morning’ (R11).

Various home-owners saw a connection between such technical issues as parking, noise, and the market worth of their houses; one objection began ‘Setting aside any religious, racist or bigoted thoughts or comments, in relationship to this proposal is that our main concern, would and will be the possible and probable de-valuation to our property’ (R44). Whilst many of the objections to traffic, parking, noise, and disruption seem like technical issues in character, we shouldn’t mistake the socio-technical artefacts and infrastructures of the everyday environment as unrelated to questions of politics (Amin Citation2007; Citation2008). Rather, we see how urban infrastructure ‘pieces the city together but also authorizes possibility’, favouring some groups and not others, in a highly uneven and contested way (Amin Citation2012, 67). We can see these questions to the fore in the next section, on the role of architecture in evoking a sense of place and public culture.

Architecture and symbolic identity within the city

In this section, we review objections on the architectural form of the mosque, its fit within the immediate area, the city of York more generally, and English urbanism in broader cultural terms. Many objections to the architectural plans for the mosque at York drew attention to its significantly extended scale; as one respondent noted, in a matter-of-fact way, ‘I can see that the new Mosque building will increase from 421m2 to 2910m2, a gain of 2489m2. This increase is a factor of seven from the existing layout’ (R16). This increased footprint is taken up in another objection: ‘It has taken 29 years for the building to reach its current capacity; this proposed increase would not reach capacity for another 180 years based on its current expansion rate … this seems somewhat excessive!’ (R19). Underlying the extension plans for a nearby business was a suspicion that ‘In reality the proposed Mosque is of a size more likely to become a regional centre of worship with the attendant adverse impact on the amenity of the neighbourhood’ (R27).

This theme of the mosque becoming too large for its surrounding streets was echoed in objections about the minarets and dome in the original proposal. Although mosque design has varied greatly over time and in different places, the British mosque has come to be identified with minarets and domes (Saleem Citation2018). Indeed, in York, concern about the mosque’s proposed minarets and dome dominating the skyline was a frequent one, with one respondent concerned about these obscuring existing residents’ view of York Minster (R8), another respondent concerned about their fit within a Victorian streetscape (R5), and another respondent (not actually resident in the city) concerned with the implications for the wider landscape of the city: ‘an example of Eastern/Arabic architecture would be completely out of character with York’ (R2). Other respondents, tellingly, conjured a sense of York as a city which was different to other English cities, with one respondent suggesting that they ‘would not like to see York become like Leeds where there are Mosques there and everywhere’ (R40). This kind of complaint could lead to paranoia about community tensions, with one respondent worried that: ‘traffic wardens in London are told not to give parking tickets to those who prey as it may result in riots’ (R4).

One respondent suggested that the ‘intent [of the mosque design] appears clearly to overawe the neighbouring buildings’ and, moreover, suspected the addition of minarets to be ‘the thin end of the wedge to have a future amplified call [to prayer], which would affect the amenities of the locality’ (R41)—in spite of this type of feature being explicitly ruled out in the proposals. The amenity of a locality, as Gale and Naylor note, is a ‘malleable concept’ which ‘has spawned considerable public discussion regarding the “appropriateness” of non-Christian places of worship to their prospective locations in Britain’s cities and towns’ (Citation2002, 389). Or, as one respondent succinctly put it, ‘You must also remember we’re a Christian country’ (R46). As was found in the contemporaneous planning tensions in Cambridge, there are clear signs here of local (and, indeed, wider) objections to mosque designs ventriloquising much wider anxieties about national identity, and ‘a significant othering of the Muslim population and a rejection of “difference” that a mosque represents’ (Villis and Hebing Citation2014, 417). It is to this strain of Islamophobic discourse, and these questions of difference and the politics of public space that we turn to next, in exploring how the mosque became a medium for the construction of social boundaries and wider questions of citizenship.

The Mosque, the aesthetics of national identity, and the politics of public space

In this section, we review objections on the planning applications of the York Mosque in relation to the ways these mediate constructing the ‘appropriate citizen’ entitled to claim their right to the city. Previous urban scholarship has shown that in the routinised interactions that shape social relations and feelings of belonging, the spaces of the city are centrally important, and that struggles and practices of citizenship are powerfully shaped and conditioned by spatial relationships and the geography of the city (Staeheli Citation2003, 99). As Painter and Philo point out, it is the immaterial—as well as material—spaces of the mind that have become important as sites of citizenship, since it is in this realm of assumptions, fears, and prejudices that citizenship in both its de jure and de facto guises is invented prior to its installation in actual practices ‘on the ground’ (Citation1995, 108). One reader at the York Press was disappointed when the then councillor Sonja Crisp welcomed the mosque plans saying that York has a strong and growing Muslim community (Aitchison Citation2012). The reader responded that ‘One building is no great consequence, but the statement that its architecture makes can be’ (Readers’ letter, York Press, 4 August 2011). The threatened status of York as a historic, cathedral city was at the centre of objections to the planning consultation:

Islam is the enemy, of this there can be no doubt … The spread of Islam needs to be halted in its tracks and one of the ways that will help is to stop the building of any more mosques. (R39)

What the heritage associated with York can (and cannot) include was more explicitly expressed in the below objection that suggested:

I am not a resident of York – although my maternal great grandparents were - but, like all Britons, particularly Yorkshire men, York is especially dear to me representing our historical heritage and our Christian tradition … There is no reason why your Moslem residents would not convert an existing building to meet their needs rather than erecting a structure which will be seen as an affront by us non Moslem majority. (R2)

Objections to the building of a mosque in York reveal a repeated theme of encroachment and triumphalism of Islam, with one resident arguing that the mosque would ‘destroy the unique characteristics which make the historic core of York so special’ (R38). There was also a shared sense of threat that ‘once one gets permission more will follow’ (R40), which another resident found incompatible with the Christian tradition in the UK, suggesting that ‘we should not encourage the building of mosques’ (R15). Even more moderate objections expressed caution, with one reader of YorkPress commenting that

I have no problem with peace-loving religions having a place of worship in our city, so long as they don’t encroach on our way of life and culture (Readers’ letter, Yorkpress, 31 August 2012; emphasis inserted). Moreover, some of these objections also reflect nationalist ideas that were mobilised around white British people and places ‘being left behind’ within the Brexit context. For example, a resident expressed concerns about ‘all these foreign people coming in, taking JOBS from our own men, their livelihood’ (R1, emphasis original).

a lot of residents are afraid to speak out about these issues in fear of being branded racist, because people of ethnic minority all too often wave the ‘human right’ card … but where are the rights of the people who have lived in this area for generations?. (R8, emphasis inserted)

The mosque was viewed by those objecting as an aggressive structure that ‘could incite racial tension (R4)’, ‘would become a catalyst for racial troubles’ (R47), and ‘will intensify the growing problem of cultural division’ (R7). One objection even made reference to past riots in other cities arguing that the mosque ‘is likely to attract a great deal of protestors [that would lead to] chaos and horrific scenes [as in] August 2011’ (R35). As was discussed above, those civil disturbances have widely been understood by the government as resulting from a lack of (and decline of) ‘social cohesion’ (Worley Citation2005). This was followed by a shift in political and policy discourse away from multiculturalism and integration in the previous decades towards security and national cohesion, which rests on a narrow sense of Britishness (Worley Citation2005, 485). Separately and together, the quotes in this section are emblematic of the tropes that Amin has characterised as working within nativist discourses; namely, the ‘raw imagery of good insiders and bad outsiders, homely pasts and scary futures, secure traditions and disruptive invasions giving affective expression and energy to the misgivings of populations feeling entitled and betrayed’ (Citation2023, 6).

Conclusion

In this paper, we focused on the interactions around mosque construction and design in York and considered how a section of the population made use of the available spaces and opportunity for objection and complaint about Islamic architecture that are closely connected with xenophobic discourses about nationhood and citizenship. We argue that these planning forums thus play a mediating role in mobilising ‘common-sense’ understandings about the ‘normal’ English landscape, and how the proposed mosque will be located within it. As highlighted in the quotes above, white British and Christian residents of York (and, indeed, elsewhere, given the objections raised by those not actually living in the city) claim to be the ‘indigenous/native’ residents ‘who have been there’ whereas Muslim residents were represented as people inclined to aggress and intrude. The negotiations around mosque planning are thus closely linked to Islamophobic and populist discourses that articulate objections to equality of citizenship, and convivial multi-cultures within the city (Neal et al. Citation2019). They also speak to the legacies of multiculturalism in a country where this project has developed not as a result of a conscious and universalistic political philosophy, but rather as a consequence of generations of migration, tied to the decline of empire and accompanied by racist ideologies (Modood Citation2013). Overall, these objections demonstrate how debates over city space are connected to the contested processes of boundary-making that separate ‘appropriate’ citizens from the ‘undeserving’, and ‘invasive’ or ‘exploitative’ migrant communities within the nation.

In our focus on how communities connect to the (British/English) city through the medium of religious architecture, this paper has demonstrated the interrelations between the urban and the national scale and the significance of the former in articulating the processes of national identity construction. And with its attention to religious architecture sitting within its wider urban infrastructure, our paper has demonstrated the need to evaluate claims to citizenship and public space as they relate to cities that are organised according to two principles: ‘multiplicity as the definite urban norm, and co-presence as being on common ground’ (Amin Citation2012, 75). As Amin continues to argue, for ‘multiplicity to mean more than diversity placed in hierarchical order, the commons has to be widely understood as a gathering of equals’ (Citation2012, 78). In the case of the York Mosque, we see the conflicting impact of particular types of building (especially religious architecture) in anchoring an Islamophobic agenda, and we see the clear inequalities of different ethnic groups in their status as citizens. We see the routinised but dangerous politics of difference, entitlement, and domination that lie behind the aesthetics of national identity, and that can be consolidated through the everyday urban infrastructures of our towns and cities (Amin Citation2023).

Within the recent past of provincial English cities, the optimism of urban citizenship struggles has given way to a more fragmented sense of conflictual claims to citizenship that reveal the cultural fears and tensions lying latent with the surface rhetorics and strategies of community integration, as is evident in our case study. Within a city with a strong Christian heritage such as York, the recent mosque building illuminates that place matters in how public cultures are positioned, contested, and ultimately extended. In this sense, we should consider the planning process as a kind of ‘discursive domain’ through which architectural aesthetics, cultural identities and fears of otherness are wrapped into nativist sentiments and the wider politics of public space (Gale Citation2005, 1163), which thus proves a useful lens to further examine the rising tension between multiple nationalist agendas and the politics of cities beyond the UK.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Anna Richter and editorial colleagues at City for their support of this article, and the two anonymous reviewers whose reports were extremely valuable in helping to improve the paper’s arguments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Öznur Yardimci

Öznur Yardimci is a researcher at the ESRC Vulnerabilities and Policing Futures Research Centre at the University of York. Email: [email protected]

Daryl Martin

Daryl Martin is a Senior Lecturer in Sociology and Co-Director of the Centre for Urban Research (CURB) at the University of York. Email: [email protected]

References

- Ahmed, N., C. Dwyer, and D. Gilbert. 2020. “Faith, Planning and Changing Multiculturalism: Constructing Religious Buildings in London’s Suburbia .” Ethnic and Racial Studies 43 (9): 1542–1562. doi:10.1080/01419870.2019.1649442.

- Aitchison, G. 2012. “York Mosque Plans Get the Go-Ahead.” York Press, August 22, 2012. Accessed May 22, 2024. https://www.yorkpress.co.uk/news/9888330.york-mosque-plans-get-the-go-ahead/.

- Amin, A. 2002. “Ethnicity and the Multicultural City: Living with Diversity .” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 34 (6): 959–980. doi:10.1068/a3537.

- Amin, A. 2003. “Unruly Strangers? The 2001 Urban Riots in Britain .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27: 460–463. doi:10.1111/1468-2427.00459.

- Amin, A. 2007. “Re-Thinking the Urban Social .” City 11 (1): 100–114. doi:10.1080/13604810701200961.

- Amin, A. 2008. “Collective Culture and Urban Public Space .” City 12 (1): 5–24. doi:10.1080/13604810801933495.

- Amin, A. 2012. Land of Strangers. Cambridge: Polity .

- Amin, A. 2023. After Nativism: Belonging in an Age of Intolerance. Cambridge: Polity .

- Anderson, B. 2012. “What does ‘The Migrant’ Tell Us about the (Good) Citizen?” University of Oxford Centre on Migration, Policy and Society Working Paper No. 94. Accessed May 22, 2024. https://www.compas.ox.ac.uk/2012/wp-2012-094-anderson_migrant_good_citizen/.

- Anjaria, J. S. 2009. “Guardians of the Bourgeois City: Citizenship, Public Space, and Middle-Class Activism in Mumbai .” City and Community 8 (4): 391–406. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6040.2009.01299.x.

- Arslan, H. D. 2019. “Ecological Design Approaches in Mosque Architecture .” International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research 10 (12): 1374–1377.

- Back, L., M. Keith, A. Khan, K. Shukra, and J. Solomos. 2002. “New Labour’s White Heart: Politics, Multiculturalism and the Return of Assimilation .” The Political Quarterly 73: 445–454. doi:10.1111/1467-923X.00499.

- Batuman, B. 2021. “Introduction: Islamisms and the Built Environment: Notes for a Research Agenda.” In Cities and Islamisms: On the Politics and Production of the Built Environment, edited by B. Batuman, 1–12. New York and Oxon: Routledge .

- Brooks, F. 1954. York and the Council of the North. London: St Anthony’s Press .

- Cantle, T. 2001. “Community Cohesion: A Report of the Independent Review Team.” Home Office, Accessed May 22, 2024. https://tedcantle.co.uk/pdf/communitycohesion%20cantlereport.pdf.

- City of York Council Design, Conservation & Sustainable Development Service. 2014. “City of York Heritage Topic Paper Update.” Accessed May 22, 2024. https://www.york.gov.uk/downloads/file/1731/sd103-city-of-york-heritage-topic-paper-update-september-2014-.

- Commission on Integration and Cohesion final report. 2007. “Our Shared Future.” June 14, 2007. Accessed May22, 2024. https://image.guardian.co.uk/sys-files/Education/documents/2007/06/14/oursharedfuture.pdf.

- DeHanas, D. N., and Z. P. Pieri. 2011. “Olympic Proportions: The Expanding Scalar Politics of the London ‘Olympics Mega-Mosque’ Controversy .” Sociology 45 (5): 798–814. doi:10.1177/0038038511413415.

- De Koning, A., R. Jaffe, and M. Koster. 2015. “Citizenship Agendas in and Beyond the Nation-State: (en)Countering Framings of the Good Citizen .” Citizenship Studies 19 (2): 121–127. doi:10.1080/13621025.2015.1005940.

- Festenstein, M. 2006. Negotiating Diversity: Culture, Deliberation, Trust. Cambridge: Polity .

- Fincher, R., K. Iveson, H. Leitner, and V. Preston. 2014. “Planning in the Multicultural City: Celebrating Diversity or Reinforcing Difference? ” Progress in Planning 92: 1–55. doi:10.1016/j.progress.2013.04.001.

- Gale, R. 2004. “The Multicultural City and the Politics of Religious Architecture: Urban Planning, Mosques and Meaning-Making in Birmingham, UK .” Built Environment 30 (1): 30–44. doi:10.2148/benv.30.1.30.54320.

- Gale, R. 2005. “Representing the City: Mosques and the Planning Process in Birmingham .” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31 (6): 1161–1179. doi:10.1080/13691830500282857.

- Gale, R., and S. Naylor. 2002. “Religion, Planning and the City: The Spatial Politics of Ethnic Minority Expression in British Cities and Towns .” Ethnicities 2 (3): 387–409. doi:10.1177/14687968020020030601.

- Gill, G. 2022. “Urban Sustainability Amid Neoliberalism: the Tensions Between Capital and Economic Wellbeing in the Contemporary City.” PhD thesis, University of York.

- Holston, J. 2009. “Insurgent Citizenship in an Era of Global Urban Peripheries .” City & Society 21 (2): 245–267. doi:10.1111/j.1548-744X.2009.01024.x.

- Holston, J., and A. Appadurai. 1996. “Cities and Citizenship .” Public Culture 8 (2): 187–204. doi:10.1215/08992363-8-2-187.

- Hussain, A. 2014. “Transgressing Community: The Case of Muslims in a Twenty-First-Century British City .” Ethnic and Racial Studies 37 (4): 621–635. doi:10.1080/01419870.2013.836604.

- Isin, E., and P. Wood. 1999. Citizenship and Identity. London: Sage .

- Kundnani, A. 2002. “The Death of Multiculturalism .” Race & Class 43 (4): 67–72. doi:10.1177/030639680204300406.

- Latour, B., and A. Yaneva. 2008. “Give Me a Gun and I Will Make all Buildings Move: An ANT's View of Architecture.” In Explorations in Architecture: Teaching, Design, Research, edited by R. Geiser, 80–89. Basel: Birkhäuser .

- Meer, N., and T. Modood. 2009. “The Multicultural State We're In: Muslims, ‘Multiculture’ and the ‘Civic Re-Balancing’ of British Multiculturalism .” Political Studies 57 (3): 473–497. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2008.00745.x.

- Modood, T. 2013. Multiculturalism: A Civic Idea. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Polity .

- Mordue, T. 2005. “Tourism, Performance and Social Exclusion in “Olde York” .” Annals of Tourism Research 32 (1): 179–198.

- Neal, S., K. Bennett, A. Cochrane, and G. Mohan. 2019. “Community and Conviviality? Informal Social Life in Multicultural Places .” Sociology 53 (1): 69–86. doi:10.1177/0038038518763518.

- Painter, J., and C. Philo. 1995. “Spaces of Citizenship: An Introduction .” Political Geography 14 (2): 107–120. doi:10.1016/0962-6298(95)91659-R.

- Peach, C., and R. Gale. 2003. “Muslims, Hindus, and Sikhs in the New Religious Landscape of England .” Geographical Review 93 (4): 469–490. doi:10.1111/j.1931-0846.2003.tb00043.x.

- Saleem, S. 2018. The British Mosque: An Architectural and Social History. Swindon: Historic England .

- Staeheli, L. A. 2003. “Cities and Citizenship .” Urban Geography 24 (2): 97–102. doi:10.2747/0272-3638.24.2.97.

- Stead, M. 2011. “Bull Lane Mosque Plan Rethink, 17 October 2011.” York Press. Accessed May 22, 2024. https://www.yorkpress.co.uk/news/9309191.bull-lane-mosque-plan-rethink/.

- Thomas, H. 2008. “Race Equality and Planning: A Changing Agenda .” Planning Practice and Research 23 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/02697450802076407.

- Tyler, I. 2010. “Designed to Fail: A Biopolitics of British Citizenship .” Citizenship Studies 14 (1): 61–74. doi:10.1080/13621020903466357.

- University of Birmingham Library Services. 2024. “Migration to the UK: an Introduction.” Accessed May 22, 2024. https://libguides.bham.ac.uk/c.php?g=672295&p=4775844.

- Van Eijk, G. 2009. “Exclusionary Policies are not Just About the ‘Neoliberal City’: A Critique of Theories of Urban Revanchism and the Case of Rotterdam .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 34 (4): 820–834. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00944.x.

- Villis, T., and M. Hebing. 2014. “Islam and Englishness: Issues of Culture and Identity in the Debates Over Mosque Building in Cambridge .” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 20: 415–437. doi:10.1080/13537113.2014.969146.

- Wintour. 2011. “David Cameron Tells Muslim Britain: Stop Tolerating Extremists.” The Guardian, February 5, 2011. Accessed May 22, 2024. http://www.guardian.co.uk/politics/2011/feb/05/david-cameron-muslim-extremism.

- Worley, C. 2005. “‘It’s not About Race. It’s About the Community’: New Labour and ‘Community Cohesion’ .” Critical Social Policy 25 (4): 483–496. doi:10.1177/0261018305057026.

- Yaneva, A. 2012. Mapping Controversies in Architecture. Aldershot: Ashgate .

- Yardımcı, O. 2023. “Drawing the Boundaries of ‘Good Citizenship’ Through State-led Urban Redevelopment in Dikmen Valley .” European Urban and Regional Studies 30 (3): 235–247. doi:10.1177/09697764221119919.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 2006. “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging .” Patterns of Prejudice 40 (3): 197–214. doi:10.1080/00313220600769331.