Abstract

This study analyzes the discursive social position of Vietnamese migrants represented by three types of Vietnamese commercial places: a large wholesale complex, Vietnamese-run grocery shops on local streets, and stylish chain restaurants in commercial centers. Guided by the notions of semiotic landscapes and geosemiotics, this study analyzes the semiotic dynamic among the spatial structures, visual images, and human activities in and around the study sites. The analysis demonstrates that the spatial representations of Vietnamese in Prague are associated with the spatial-visual discourses of the globalized city. The walled wholesale complex, situated on the margin of the city, serves to discursively segregate the diasporic community from the mainstream society. Ubiquitous grocery stores on local streets paradoxically signify the inconspicuousness of Vietnamese in Czech society. On the other hand, stylish Vietnamese restaurants in commercial centers add sophisticated cultural tastes and are included in the cosmopolitan dynamic of Prague. This geosemiotic study illustrates how geographical centrality and marginality are intertwined with migrants’ commercial practices, reflecting their multilayered positions in the socioeconomic strata of society. In transnational urban spaces, understanding the discursively associated ethnic markers and their urban locations provides important insights into the inclusive and exclusive dynamics of globalized cities.

Introduction

Long before I started paying attention to Vietnamese in the Czech Republic (CR) as my research subjects, I, as a member of a family from South Korea, was already relying on Vietnamese businesses. A Vietnamese wholesale complex in Brno was the only place I could buy some essential materials for my ethnic cuisine. I occasionally bought small, cheap toys like fidget spinners for my little daughter, who was often fascinated by garish displays in front of a Vietnamese-run chandlery in the underpass of Brno’s main railway station. After moving to Prague, I became increasingly intertwined with Vietnamese people and places, partly because of my research but more because of their visibility in my everyday life. In the bigger city, I often drop into a small Vietnamese-run grocery shop for simple items instead of driving to a big chain grocery store. I have become a regular customer of a Vietnamese hairdresser. I have had many visitors from South Korea, as I live in one of the most popular destinations for Korean travelers, and Vietnamese pho is always the best option for treating those who miss Asian flavors. I have often taken pictures of those everyday Vietnamese places I visit or pass by intentionally and unintentionally. This study is based on my everyday experiences, as well as my photographic surveys.

While various commercial activities have shaped urban lifestyles in modern cities (Zukin Citation2012), urban lifestyles have represented the symbolic capital of people and urban places (Bourdieu Citation1984, Citation1989). Attracting more people, money, goods, and brands, commercial centers are places for accumulating not only economic capital but also cultural capital. Additionally, there are many different commercial activities taking place on the margins of a city. However, store fronts, goods, and people around marginal areas tend to be different from those in commercial centers. The visual distinctions are combined with the geographical locations and spatial compositions to construct different types of urban landscapes that represent various economic, social, and cultural values. Theoretically and analytically guided by the concepts of semiotic landscapes and geosemiotics, this study analyzes the spatial-visual discourse constructed in three types of commercial landscapes shaped through Vietnamese commercial activities in Prague: a huge Vietnamese wholesale complex situated on the edge of Prague, Vietnamese-run grocery shops located on every corner of the city, and stylish Vietnamese fast-food chain restaurants burgeoning in commercial centers. By analyzing the semiotic landscapes composed of the spatial locations and structures, visual images, and human activities in and around the study sites, this study demonstrates how the spatial-visual discourse embedded in the landscapes represents the multiple meanings of ‘Vietnamese’ in the CR.

Vietnamese in Prague

Forming the third-largest group of migrants after Ukrainians and Slovaks, more than eighty thousand Vietnamese, including Czech citizens and long-term residents, live in the CR (Czech Statistical Office Citation2021). Vietnamese migration to the CR can be traced back to 1955 when the first group of Vietnamese people arrived as a result of the agreement on economic and technical cooperation between then-Czechoslovakia and Vietnam (Neustupný and Nekvapil Citation2003). Brouček (Citation2016) broadly summarizes two waves of the Vietnamese influx in Czech history; while the first wave in the 1970s and 1980s was based generally on government-assisted labor migration, including industrial training programs, the second wave in the 1990s was mainly led by business-oriented migrants and their compatriot employees. Joining the major pattern of migration to other postsocialist countries, Vietnamese migrants in the CR actively engaged in the trade of cheap goods mainly from China in the early 1990s (Szymańska-Matusiewicz Citation2015). Unlike other large migrant groups like Ukrainians, therefore, the Vietnamese community is comprised of a large number of business owners (Drbohlav and Dzúrová Citation2007). Usually starting with street sale stands, the migrant businesses have gradually moved to regular stores because of both stricter regulations and higher standards of businesses (Drbohlav and Čermáková Citation2016). Mainly due to the stabilization of Vietnamese businesses, there has been a significant increase in Vietnamese migrants with regular work contracts since 2006 (Svobodová and Janská Citation2016). This historic background of Vietnamese economic practices in the CR is represented by many small businesses visible across the CR, as well as large Vietnamese marketplaces in cities like Prague, Brno, and Cheb (Brouček Citation2016).

Despite the ubiquitous presence of Vietnamese businesses, economic transactions among Vietnamese predominantly occur within the diasporic community, forming an exclusive ethnic economy (Drbohlav and Čermáková, Citation2016). These businesses rely on border-crossing commercial activities centered around SAPA, the exclusive Vietnamese wholesale complex in Prague (Brouček, Citation2016; Hüwelmeier, Citation2015; Martínková, Citation2011). Similar to the Vietnamese in Slovakia, who were described as ‘the early winners in globalization’ by William and Baláž (Citation2005), early Vietnamese migrants in CR successfully settled in the Czech marketplace by leveraging their transnational diasporic network. However, the sociocultural interaction of this early generation with other communities has been very limited due to their constrained linguistic and cultural competence, along with widespread discrimination in Czech society (Pham Citation2022). The Vietnamese community is notable for its relatively large number of children (40 percent) (Kušniráková Citation2014). Unlike the first generation confined within the diasporic community, the younger generation, who have been raised in CR, actively interact with both their diasporic community and Czech society (Pham Citation2022). Studies have reported a unique hybrid identity formation among young Vietnamese (Pham and Kraus Citation2024) and active social engagement of the younger generation (Freidingerová and Nováková Citation2021).

Vietnamese places in Prague

Whereas Vietnamese migrants founded their settlements in border cities such as Cheb and Karlovy Vary in the early years of postsocialist CR, their migratory direction turned to bigger metros, mainly Prague (Brouček Citation2016). Traveling around Central European countries and maintaining the trading route from China and Vietnam, Vietnamese migrants founded marketplaces in border cities and then later in Prague (Hüwelmeier Citation2015). An exclusively Vietnamese wholesale complex called Sapa is the largest Vietnamese marketplace in the CR (Brouček Citation2016). Sapa is the home of various large and small Vietnamese businesses, including wholesale vendors, food businesses, hair and nail shops, logistic companies, and migrant-service businesses called dịch vụ (meaning service in Vietnamese). Located in the southern end of Prague, the walled wholesale complex has been not only an economic center but also a ‘communal space for the whole Central European Vietnamese diaspora’ (Brouček Citation2016, 41). As an economic center, Sapa supplies cheap imported goods and food supplies for numerous Vietnamese businesses situated on every corner of streets cross the country.

Specializing in small grocery shops, fast-food-style bistros, and nail shops, Vietnamese businesses have become an important part of Czech urban landscapes. Food stores or convenience stores are some of the most common businesses of diasporic communities across the world (e.g. Parzer and Astleithner Citation2018), and the small grocery shop called potraviny (groceries) or vecerka (night shop) is the most prominent type of business visible, even in small towns far from major cities. Despite the lack of official data, it is widely known that a majority of potravinies across the country are owned by Vietnamese. Thus, a potraviny is often called a ‘Vietnamese shop’ by local Czech residents. Relying mostly on the supply network of Sapa, potravinies mainly carry ordinary foods and goods that are also available in most grocery chains in the CR. While most banal-looking Vietnamese small businesses are found on local streets, food businesses with so-called urban-chic style have been increasingly visible in commercially active areas. There have been more brand Vietnamese restaurant chains, especially in commercial centers and big shopping malls. Despite the ubiquity of Vietnamese-run grocery shops and restaurants in Czech cities, no academic study has explored these places. As the first study of this kind, this study pays particular attention to the commercial landscapes around the abovementioned places; Sapa stands at the edge of Prague while separated from local neighborhoods; the ubiquitous potravinies are paradoxically insignificant on local streets; trendy Vietnamese restaurants add cultural accents to the rapidly expanding cosmopolitan commercial areas. These three types of commercial landscapes made up of spatial structures, visual materials, and human interactions are useful texts for reading how these landscapes discursively index the sociocultural positions of Vietnamese migrants in various ways.

Semiotic landscapes of urban transnationalism

Weaving together scattered discussions into a coherent notion of transnationalism, Vertovec (Citation1999) points out that reconstruction of place or locality is one of the prominent phenomena of transnationalism. In describing how global migrations have denationalized urban spaces, Sassen (Citation2000) maintains that transnational migration is more like an urban phenomenon than a national-level border crossing (Friedman Citation2002; Smith Citation2005). Similarly, studies on transnational migration have suggested cities as the basic unit in understanding the formation of migrant communities (e.g. Blunt and Bonnerjee Citation2013). Cities and diasporic communities have mutually shaped each other in continuous contextual interplays, which makes diaspora a spatial process (Finlay Citation2019).

Whereas natural spaces are delimited by physical boundaries, social spaces are produced through triadic interplay among everyday spatial practices, representations of space, and representational spaces, which overlap one another (Lefebvre Citation1991). Similarly, Soja introduces the notion of thirdspace, explaining how social spaces are shaped through ‘trialectics of spatiality-historicality-sociality’ (Citation1996, 57). Our urban spaces are composed of numerous everyday practices, and everyday life is staged in urban spaces as social theater that constitutes various public and private relations (De Certeau Citation1984; Mumford Citation1937). In the dynamic interplay between daily life and urban space, migrants have gained ‘the right to transform and produce urban space and the right to spatialize and display distinctive identities’ (Finlay Citation2019, 789). However, the right is not always evenly distributed to all the inhabitants because urban space is ‘the product of power-filled social relations’ (Massey Citation1999, 21). When produced, social spaces are permeated with diverse social relations among spaces, material structures, and human agents. The present study aims to dissect the social relations layered in the spatial variations opened up by Vietnamese migrants in Prague.

The representation of urban spaces is a visual event. More precisely, it is a visually mediated ideology (Berger Citation2008). Pointing out the limited understanding of landscape as literary representation of the visible world or as human phenomena which can be empirically verified, Cosgrove (Citation1998) redefines landscape as a social product of collective human activities: ‘Landscape is a way of seeing the world’ (13). In other words, landscape is composed not only of the literally visible world and verifiable human activities but also of discursive and ideological relations among physical structure, location, and human activities. This study’s sites are often called simply ‘Vietnamese places’ due to the ownership of the places. However, the meaning of ‘Vietnamese’ in each place is associated with its landscape, which is discursively constructed by the spatial-visual dynamics. As Soja (Citation1996) maintains, spaces are simultaneously real and imagined, so multiple meanings are likely to be layered in Vietnamese commercial landscapes.

Studies of semiotic landscapes have scrutinized the complex network of meanings often imposed with various signs, including indexical codes, visually represented images, and interactions among signs and between humans and signs (Jaworski and Thurlow Citation2010). Sharing epistemological ground with the notion of linguistic landscape that focuses on both informational and symbolic functions of linguistic texts inscribed in a spatial territory (Landry and Bourhis Citation1997), the notion of semiotic landscape widens the scope of linguistic text by including various place-making semiotic and material resources (Lee and Lou Citation2019). As social semiotics emphasizes ‘social action, context, and use’ of signs (Hodge and Kress, Citation1988, 5), semiotic landscape studies interpret various visual, textual, behavioral, and structural components that make up a certain place. Composed of various semiotic resources in an urban place, such as buildings, visual installments, texts on signboards, sounds, colors, smells, languages, body images, and goods (Jaworski and Thurlow Citation2010), an urban landscape is a meaningful whole woven together with semiotic and material conditions (Hodge Citation2017, 34). This study posits that the three types of Vietnamese commercial landscape composed of various semiotic resources are also likely to index the social meanings of the places and the human actors as meaningful wholes.

Commercial landscapes and social positions

Ethnic economies and urban spatial changes have interplayed in shaping transnational urban spaces (Kaplan Citation1998). With the complex influx of migrants, ethnic economies have evolved into multi-ethnic enclaves, where multiple ethnic groups compete by commodifying their cultures (Collins, Citation2020). On the other hand, the preservation of old ethnic commercial areas has also been discussed in response to the decline of ethnic businesses (Chan and Zhou Citation2022). There has also been an increasing number of ethnic retail chains in ethnic neighborhoods, which impacts the formation of ethnic economies (Somashekhar Citation2019). Studies have long documented Vietnamese migrants who have established ethnic enclaves in their destination countries, giving rise to culturally distinctive commercial areas such as Little Saigon (e.g. Mazumdar et al. Citation2000). Price, Abdinnour, and Hughes (Citation2017) historically analyze the role of Vietnamese entrepreneurs in transforming urban commercial districts and spreading ethnic businesses across a small American city.

Many linguistic landscape studies have delved into how diasporic communities express their ethnic identities through commercial-spatial practices (e.g. Khayambashi Citation2019). Among these, global Chinatowns, as visually prominent diasporic commercial places, have been scrutinized to understand the significance of language inscriptions in shaping and negotiating identities (e.g. Zhang, Seilhamer, and Cheung Citation2023; Zhao Citation2021). Studies have also captured the emergence or redesign of Chinatowns as a result of the commodification of culture amid the recent expansion of tourism (Lee and Lou Citation2019; Sharma, Citation2021). Vietnamese migrants’ businesses have recently been subject to study, highlighting how their ethnic identity is linguistically represented in their commercial activities (Tran Citation2021) and how language is used to commodify both their ethnic authenticity and hybridity (Nguyen Citation2022). While these migrant businesses visually represent their distinctive identities, they also tend to create a ‘self-orientalized diaspora space’ by commodifying ethnicities (Finlay Citation2019, 787). These studies primarily analyze linguistic and visual materials located in diasporic commercial areas to demonstrate the various contesting discourses imposed on the commercial landscapes. Visual-material-human signs, commonly found in these studies, often commodify ethnic authenticity while reflecting the competitive cultural politics in transnational urban spaces (Leeman and Modan, Citation2009; Lou Citation2016).

Discourses lying in diasporic commercial landscapes not only index cultural differences but also imply the socioeconomic positions of human actors in given places. Since a local commercial place is ‘simultaneously a site of social, economic, and cultural exchange’ (Zukin Citation2012, 282), commercial activities in migrants’ places are likely to be important semiotic cues representing the socioeconomic status of diasporic communities. A study of a Tibetan landscape in Chengdu, China, demonstrated that the dominant Tibetan atmosphere in a thriving market is a sign of a successful economic collective of Tibetan migrants (Brox Citation2019). Commercial activities of migrants claim their various rights to the city, such as their visible presences, their participations in the local economy, and their productions of new socio-spatial patterns (Finlay Citation2019). In a semiotic landscape study of a Berlin neighborhood experiencing rapid gentrification, Papen (Citation2015) argues that discourses layered in commercial activities index the neighborhood’s position in the social strata.

Just as social space functions like symbolic space representing the symbolic capital of a certain place, according to Bourdieu (Citation1989), semiotic landscapes shaped with migrants’ commercial activities may reflect the socioeconomic positions of the people and the places. Placed in the dynamic between global and local contexts, the geocultural locations of migrants’ places and their spatial practices are combined to signify the symbolic positions of migrants’ communities (Kim Citation2021). In vibrant migrants’ commercial places, the material traces of migrants’ social interactions and markers of their settlement can be the ‘most common signifier(s) of the ethnic and class vernaculars’ (Krase and Shortell Citation2011, 372). Vernacular landscapes are constituted with ordinary people’s practices in their everyday worlds, such as home, marketplace, and workplace (Jackson Citation1984). As Brox (Citation2019) demonstrates, ethnic authenticity forms unique vernacular landscapes in a migrant neighborhood, while the wealth disparities in the area form contesting vernacular landscapes. Thus, vernacular landscapes of diasporic communities connote migrants’ symbolic social class, as well as their ethnic distinctiveness (Krase and Shortell Citation2011). As a study on the vernacular landscapes of a marketplace in Leeds, United Kingdom, shows, we may understand the power dynamics underlying symbolic tastes by seeing unregulated landscapes (Adami Citation2020). Interlocked with the urban transformation of the rapidly globalizing city, Vietnamese commercial places in Prague could also imply the complex positions of the Vietnamese migrant community in the CR. Investigating three different commercial places run by Vietnamese people, therefore, the present study analyzes vernaculars inscribed in the geocultural locations, visual materials, and human practices of the Vietnamese commercial places.

Geosemiotics

As an analytic lens for making ‘reference to the social meaning of the material placement of signs and discourses,’ geosemiotics is widely adopted in the abovementioned studies of linguistic and semiotic landscapes (Scollon and Scollon Citation2003, 4). Positing geographical places as discursive vehicles, geosemiotics has contributed to the growing academic focus on the urban place as communicative medium (Aiello Citation2021). In the course of analyzing the integration of social positioning and power relationships in the material world, geosemiotics sees geographical places as semiotic aggregates made up of interaction order, visual semiotics, and place semiotics. First, originating from Goffman’s notion, interaction order can be defined as human actions that ‘form social arrangement’ (Scollon and Scollon Citation2003, 7). Second, visual semiotics refers to visible materials, such as signs and design layout, installed in a place. The represented meanings of visual materials are analyzed in a certain spatial context. Last, place semiotics deals with place as a semiotic system of built environment along with other regulated and natural surroundings. More important, the three semiotic systems interact to form complex semiotic aggregates (Scollon and Scollon Citation2003).

Studies on urban transnational places composed of migrants’ diasporic practices have employed the geosemiotic framework in exploring discourses reflected in the built environment and human interactions in given places (Lee and Lou Citation2019; Tran Citation2021). These studies demonstrate that the triangular semiotic analysis of geosemiotics is particularly suitable for understanding the social positions of transnational places because (1) transnational places, as cultural contact zones, are where diverse people belong to different demographic segments; (2) transnational places, as places socially produced by global and local dynamics surrounding migrant and local populations, are generally represented by distinctive visual images such as languages, signs, shops, and lifestyles; and (3) spatial compositions of transnational places are often distinctive from other local places within the same urban areas. Following the analytic guidelines of geosemiotics, this study analyzes how human interactions, visual materials, and built environment are discursively interwoven to index the sociocultural position of the Vietnamese places.

All three places in the study are commercial sites frequented by customers and business-related people. Interaction orders constructed with human actors in the places are closely analyzed to present how interactions among people and between people and material structures signify the discursive meaning of places and people. The social status of globally mobile people is often represented by their placemaking practices in certain urban places (Polson Citation2016). This study examines the interplay between the symbolic capital of people and of places.

Visual semiotics are composed of visual materials such as color, shape, texture, and their composition is analyzed to demonstrate how visual materials installed around Vietnamese places interact with discursive locations, social spaces, and human activities in constructing landscapes. Zukin (Citation1998) demonstrates that aestheticization is an important visual practice in ever-commercializing contemporary cities; the visual images of a commercial place connote the place’s position in the strata of a consumer society. While visualized brands and global languages often index a place with privileged symbolic values, such as cosmopolitan, modernized, and sophisticated tastes (Leeman and Modan Citation2009), other visual materials, such as temporary fliers and displayed shoddy goods, may represent the marginal position of a place (Kim Citation2021). This study also aims to unveil the underlying discourses of visual practices.

Place semiotics begins with understanding the discursive meanings of different geographical locations, in this case three different types of places in Prague. A geographical location often becomes a certain index in a local context (e.g. Lynn and Lea Citation2005). Thus, this study analyzes the place semiotics of each place by putting it in the context of a geographical location within Prague. As the functionality of places, such as public or commercial spaces, is an important semiotic resource in geosemiotics (Scollon and Scollon Citation2003), this study also investigates how different types of Vietnamese places connote the hierarchical meanings of the places. Also, the spatial dynamic made up of the Vietnamese places and their surroundings is analyzed as an important resource in place semiotics.

Although I, as a daily customer as well as a dweller in Prague, quotidianly visit these study sites, I also conducted structured walking fieldwork, which consisted of multiple field observations in many different shops (in the case of potravinies). The fieldwork was designed to establish walking and photographic surveys as the main methods of data collection and analysis (Banda and Jimaima Citation2015; Krase and Shortel Citation2011). Ethnographic walking enables researchers to interact and communicate in urban spaces while enhancing their multisensory experiences (Shortel Citation2018). Recognizing the methodological benefit of ethnographic walking in urban landscape studies, several studies have employed ethnographic walking to interpret social discourses layered in everyday places (e.g. Brox Citation2019). I took photographs during field observations to avoid sampling bias that could result from the use of preexisting photographs (Krase and Shortell Citation2011). A photographic survey has a merit in that it can ‘capture and compare details’ of the landscape (Hall Citation2009, 456). In order to consistently maintain the study focus, the present study excludes pictures taken after the outbreak of COVID-19. Because various regulations have affected daily urban practices and businesses, pandemic-related changes should be discussed in a separate research study. Thus, the present study covers field observations conducted from summer 2017 to winter 2019.

The geosemiotics of Vietnamese commercial landscapes in Prague

Exploring the discursive meanings layered in Vietnamese commercial landscapes in Prague, the analysis starts with Sapa, a large wholesale complex hosting a tremendous number of small wholesale vendors along with various retail and service businesses. As the supply center of Vietnamese businesses, this wholesale complex marks the beginning of Vietnamese commercial practices in Prague. The analysis then turns to potraviny, which are perched at every corner of Prague’s local streets. Understanding the spatial and visual composition of these common Vietnamese businesses is crucial for grasping the implied socioeconomic position of the migrants in Czech society. Noticing the recent emergence of new, stylish Vietnamese food businesses in the touristic centers of Prague, this analysis lastly examines the new commercial practices that are being integrated into the cosmopolitan commercial landscapes of the city’s center.

Sapa: representation of Vietnamese

Sapa is geographically located in the south end of Prague. It is currently unreachable by subway or tram, which is the backbone of Prague’s public transportation system. Coming from the city center either by bus or one’s own car, one may pass large farmlands stretching several kilometers. The wholesale complex is surrounded by farmlands and residential areas filled with panel apartment buildings, called panelák in Czech. Built during the socialist era, panel apartments, often derogatorily referred to as socialist housing, have been criticized for various issues including grey facades, poor construction quality, and their long-standing negative association with residents, particularly vulnerable populations like the Roma (Zarecor, Citation2011). The overall landscape, composed of farmland, small villages, and panel apartments, is a prominent component of the place semiotics of Sapa that signifies this area as underdeveloped compared to the other parts of the city. The location, limited reachability, and surrounding environments connote the symbolic marginality of the migrant community, as Sapa represents the Vietnamese community as well as being the largest Vietnamese marketplace in the CR. The impression of underdevelopment and segregation is also visually signified by the structure of Sapa as a walled marketplace containing many decayed buildings and unorganized shops and vendors. The majority of human actors in Sapa are Vietnamese migrants running small wholesale businesses scattered throughout the area. Their daily practices of moving, stacking, and selling goods form the primary interaction order in the wholesale complex. Combined with the place semiotics composed of the location and the surrounding environments, and the visual semiotics made up of the decaying structures and confusingly stacked cheap goods, the interaction order completes a comprehensive geosemiotic aggregate signifying the marginal position of the marketplace in Czech society ().

Despite the unorganized composition, there are three distinctive landscapes signifying Sapa as a commercial, ethnic, and transnational place. First of all, numerous wholesale vendors located inside and outside buildings construct a commercial landscape by displaying a tremendous amount of merchandise and engaging in transactions with wholesalers, retailers, customers, and their vehicles. Second, many Vietnamese restaurants scattered in Sapa and grocery shops clustered nearby the main entrance create an ethnic landscape that highlights a distinctive culinary culture with visual materials such as Vietnamese signboards, photographs of foods, and displayed food items. The Vietnamese-themed gate and a Buddhist temple next to the food-business cluster visually index the ethnicity of the landscape. Third, the wholesale complex is also a social space facilitating transnational interactions. The transnational landscape is composed of groups of Caucasian retailers who procure wholesale products in bulk and non-Vietnamese Asian visitors who consume Vietnamese foods and Asian groceries. Czech, Vietnamese, and English on the signage of various migrant service businesses, such as travel agencies, currency-exchange services, international money-transfer services like Western Union, and international logistic companies, typically make up the transnational landscape.

While indexing Sapa as commercial, ethnic, and transnational places, the landscapes discursively represent the ambivalent sociocultural position of Vietnamese migrants in the CR. The brisk commercial transactions taking place visually prove how Vietnamese migrants are sustained by ubiquitous business in the CR. The large businesses like Tamda Foods, a warehouse club, and logistic services represent the success of the Vietnamese economy in the CR. On the other hand, the whole area is packed with small vendors carrying cheap merchandise in a bulk. Fake-brand goods piled helter-skelter under the dimmed light in shack-like wholesale halls visually signify the informal and marginal economic practices of the Vietnamese community. In the dark and narrow hallway lined with wholesale vendors, visitors may come across shopkeepers and children eating foods and playing card games. While goods, Vietnamese sellers, and spatial compositions form semiotic aggregates connoting the informal and marginal position of the commercial place, its location and the wall delimiting Sapa both discursively and geographically, separate it from the capital city of CR.

The implied informality and marginality are likely to be associated with the visible ethnicity of food businesses and their surroundings. As Sapa is often intended for cultural consumption by local Czechs and non-Vietnamese foreigners, the visual-ethnic cues, such as foods, signs, installments, and facilities, continuously link the whole place to the Vietnamese community. The vibrant economic activities in the busy commercial place represent the successful economic presence of the Vietnamese community. In the meantime, the marginal location and the humble look of shops, spatial structures, visual materials, and human activities become semiotic aggregates that represent the discursive sociocultural position of the Vietnamese community.

Potraviny: Vietnamese as local vernacular

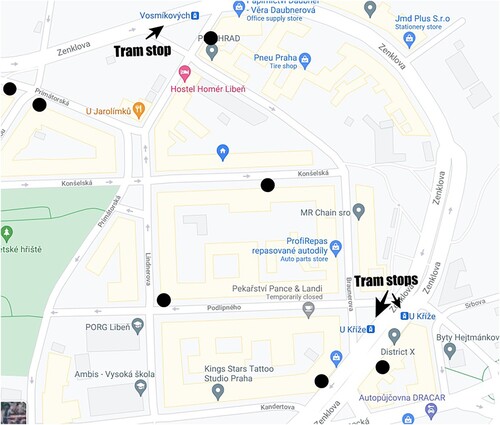

Vietnamese-run potravinies in Prague are literally ubiquitous. While many potravinies are located near a public transit stop, there are also plenty of potravinies on side streets and corners of streets in local residential areas. Potravinies can even be spotted across the street from large grocery chains on most commercial streets all over Prague. Despite their size and visual appearance, small potravinies still invite local residents quickly buying a few items, commuters stopping by for simple items like candy and cigarettes, or travelers picking up cheap drinks and late-night snacks. As they are simply called potravinies, most shops look identical because of the humdrum design of window signage and displayed common goods. As the general term potraviny indicates, the common façade of potravinies drily indicates the type of the business. While potravinies are visible everywhere in Prague, they are visually insignificant due to their mundane appearance lacking distinctive identity, their ubiquity in the city, and the flow of ordinary people coming in and out of the shops ().

Figure 2: Potravinies (black dots) in a neighborhood in Prague (Source: ©2021 Google Maps. Image captured and modified by Tae-Sik Kim.).

Bulky metal security bars, clumsy graffiti, and pictures of cannabis products and peculiar alcoholic drinks, such as absinth, are often paired with men drinking from a bottle in front of a potraviny. Most potravinies also carry prepaid sim cards and post the logos of mobile providers. A little chip with the logo of a giant mobile corporation no longer connotes advanced technologies and digital economies when displayed with cheap toys and chewing gum on the counter of a potraviny. Instead, a sim card signifies dislocation from the major market. Sharply contrasted with chain supermarkets with well-designed brand logos and promotional posters, the banal appearance of the everyday grocery shops on every corner of local streets makes up the vernacular landscape in local neighborhoods of Prague (Krase and Shortell Citation2011). The local vernacular is complemented by surrounding small businesses such as textile shops without certain brands, local bistros displaying common menus on their windows, and repair shops stacked with old electronics.

Upon entering any potraviny, the local vernacular takes on an ethnic variation, particularly with Vietnamese shopkeepers standing behind the cashier’s counter, which is crammed with trivial goods apparently placed to attract children (). The ordinary items everywhere in CR sharply contrast with the distinct ethnic difference of the shopkeepers. These shopkeepers are often observed sitting before small televisions or using mobile devices that emit foreign sounds to ordinary local Czech customers The Vietnamese identity is conveyed through sensory perceptions, including the appearance of the shopkeeper and their daily practices. The local vernacular, characterized by insignificant appearances and inexpensive goods of the small shop and its neighboring shops, overtly merges with the ethnic identity of the human actor within the shop. The very local, everyday grocery shop in the CR is, therefore, commonly called ‘Vietnamese shop’ regardless of the types of merchandises that it carries. The perceived insignificance, banality, and informality of the shops are likely to be intertwined with the ethnic origin of the shop owners. The labeled ethnicity is placed in the same position as the potraviny in the capitalist market economy. Vietnamese are discursively situated one step away from the commercial centers where regular customers buy essential, well-packaged goods and foods When the visible ethnic origin of the shop owners, the lack of uniqueness in their ubiquity, and the perceived informality and banality are discursively associated, the small grocery shop signifies the marginalized position of the people associated with this type of business.

Banh-mi-ba: cosmopolitan Vietnamese

The potraviny is not the only type of Vietnamese business seen everywhere in Prague. There are many Vietnamese nail shops and restaurants in large shopping malls and touristic streets, as well as in local streets. In particular, the restaurant business is one of the most representative Vietnamese business types because of not only the large number of restaurants but also their overt Vietnamese-ness. Vietnamese foods are the most commonly available Asian foods in the CR. There has been an increasing number of stylish Vietnamese restaurants with unique brands in recent years. Located in highly commercial areas of Prague, these places are visually distinguished from the rather banal look of Vietnamese restaurants on local streets. Blended with the stylish look and the commercial surroundings, young people who either work or eat there create the trendy vibe of these places. The locations and surroundings of stylish Vietnamese restaurants, along with their visual images and branded designs, seamlessly blend with the young students, professionals working nearby, and tourists from various countries who frequent both the interior and exterior spaces of these establishments. This integration creates a semiotic aggregate that signifies Vietnamese culture as an integral part of the cosmopolitan landscape.

Banh-mi-ba is a Vietnamese fast-food chain in three different locations populated by young people and foreigners in Prague (). The largest shop is located across from the historic main post office of Prague, which is on the street that leads to the symbolic center of the city, Wenceslas Square. Another shop in the city center is located at the mouth of historic Old Town, which is always crowded with many visitors from all over the world. There is another Banh-mi-ba in a district called Karlín, which has recently been redeveloped with many new office buildings that house regional offices of well-known transnational corporations hiring many foreigners. Karlín is known as one of the most popular destinations for young people, mainly due to many trendy food businesses, including pubs and cafes. Indexed as cosmopolitan areas with many foreigners, the common use of English, and global commercial brands (Leeman and Modan Citation2009; Papen Citation2015), these locations work as place semiotic signs that place the Vietnamese restaurant chain in the center of the commercial market.

Figure 4: From left: interior of Banh-mi-ba in Karlín, exterior of one in the Old Town, and exterior of the one near Wenceslas Square. (Source: Tae-Sik Kim).

Unlike most Vietnamese restaurants displaying many photographic images of Vietnamese foods under signs in Vietnamese characters, the design concept of Banh-mi-ba is overtly simple; the logo is designed with Banh-mi-ba in lowercase letters without Vietnamese accented letters; the façade is decorated with the logo but with no ethnic hints. Named for a famous Vietnamese fast food, bánh mì, the restaurant informs pedestrians of its ethnic origins. As bánh mì literally means ‘bread’ in Vietnamese, the logo of the chain restaurant is a simple line illustration of a baguette. Although the bread implies the colonial history of Vietnam and France, the simple image plainly indexes a familiar type of bread. The interior of the restaurant is composed of typified stylish items, such as bar tables, fashionable lighting, large menu boards with vogue food photos, and bilingual Czech and English menus. Whereas foods and food photos represent the ethnic origin of the place, its plating styles, languages, menu designs, and table settings index modernity, cosmopolitan orientation, and sophistication (Leeman and Modan Citation2009). As commercial signs often represent how businesses are positioned in stratified global consumer practices (Jaworski and Thurlow Citation2010), Banh-mi-ba restaurants place themselves in the context of cosmopolitan consumerism while representing the symbolic capital of their geographical locations (Bourdieu Citation1989).

It is common to see young people sitting at the tables and waiting at the counter in all three Banh-mi-ba shops. It is also customary to see several people hanging around outside the shops at peak times. Mixed with Caucasian employees, Vietnamese servers represent the ethnic origin of the restaurants by working busily around the floor. The visual ethnicity of the employees is dimmed by their fluent Czech and English. Their casual-style clothes do not stand out much in the shop full of young customers. Located in commercial centers busy with transnationally mobile people, the Vietnamese fast-food chain provides foods and venues suitable for the cosmopolitan tastes of young professionals and globetrotters. The Westernized style of the Vietnamese places contributes to the cosmopolitan commercial landscape in the capital city of the CR. The spatial positions, located in the city's commercial centers, become important place semiotics that interplay with the sophisticated visual designs of the chain restaurant as visual semiotics. The customers and employees, both inside and outside the restaurants, add another semiotic dynamic by forming interaction orders with the spatial and visual cues, completing semiotic aggregates that identify the Vietnamese chain with a cosmopolitan urban center instead of a locally isolated and marginal diaspora.

Concluding remarks

Grounded in a geosemiotics analysis of places, visual materials, and human interactions, this study shows how the three types of Vietnamese commercial places in Prague discursively represent the multilayered Vietnamese people while corresponding to the spatial hierarchies in the capital city of the CR. In analyzing place semiotics, this study notably takes the discursive locations of the study sites into account. All the semiotic resources, such as places, visual representations, and human interactions, are interwoven in the discursive meanings of geographical locations. The discourse of location is always subject to a series of urban (re)developments, the expansion of tourism, and the global-local economic dynamics. Thus, this study theoretically suggests that a semiotic landscape study must be firmly based in the locational context of the study site. This analytic framework proves to be a practical as well as a theoretical guide to geosemiotic studies focusing on ever-changing urban places.

The geosemiotic understanding of transnational urban spaces offers an opportunity to explore the spatial discourse of migrants in global urban areas. By analyzing the semiotic associations among places, visible practices, and human interactions, this study illustrates how geographical centrality and marginality are intertwined with migrants’ commercial practices, reflecting their multilayered positions in the socioeconomic strata of society. Migrants who relocate to new societies with distinct everyday practices often leave ethnic markers through their visible practices. These visual markers are interpreted discursively within dominant social discourses. In societies that celebrate thriving cosmopolitan commercial expansion, locally isolated ethnic markers are likely to be excluded from the dominant social discourse. When migrants contribute to the celebratory diversity of the cosmopolitan center, they become part of a new cosmopolitan repertoire. In transnational urban spaces where globally mobile populations are increasingly visible, understanding the discursively associated ethnic markers and their urban locations provides important insights into the inclusive and exclusive dynamics of global cities.

The wholesale complex on the edge of Prague, the numerous small groceries, and the stylish chain restaurants collectively represent the trajectory of Vietnamese migration to the CR. While spatially segregated, Sapa continuously supplies resources for the Vietnamese small businesses. The diverse products supplied by Sapa are now found ubiquitously across the city. However, Vietnamese culture is recognized as an integral component of global cultures when it is located in the globalized commercial centers. This spatial trajectory forms a flow, aligning with the level of commercial centrality of their locations in Czech society. The Vietnamese commercial and human network originates from the literal margins of the city, extending toward every corner, and finally reaching the bustling commercial centers. The presence of Vietnamese businesses in multiple locations across Prague discursively represents their multiple yet evolving positions within the rapidly changing Czech capital.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Tae-Sik Kim

Tae-Sik Kim is a Senior Lecturer in the School of Arts and Social Sciences at Monash University, Malaysia. Kim received his M.A. and Ph.D. in Anthropology from the State University of New York at Buffalo and Communication Studies from the University of Oklahoma, respectively. Prior to joining Monash, he worked as an Assistant Professor at Masaryk University in the Czech Republic. His research interests range from transnational communication to urban communication and visual communication. Email: [email protected]

References

- Adami, E. 2020. “Shaping Public Spaces from Below: The Vernacular Semiotics of Leeds Kirkgate Market .” Social Semiotics 30 (1): 89–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2018.1531515.

- Aiello, G. 2021. “Communicating the “World-Class” City: A Visual-Material Approach .” Social Semiotics 31 (1): 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/10350330.2020.1810551.

- Banda, F., and H. Jimaima. 2015. “The Semiotic Ecology of Linguistic Landscapes in Rural Zambia .” Journal of Sociolinguistics 19 (5): 643–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/josl.12157.

- Berger, J. 2008. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books .

- Blunt, A., and J. Bonnerjee. 2013. “Home, City and Diaspora: Anglo–Indian and Chinese Attachments to Calcutta .” Global Networks 13 (2): 220–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12006.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard university press .

- Bourdieu, P. 1989. “Social Space and Symbolic Power .” Sociological Theory 7 (1): 14–25. https://doi.org/10.2307/202060.

- Brouček, S. 2016. The Visible and Invisible Vietnamese in the Czech Republic. Prague: Institute of Ethnology, Academy of Science .

- Brox, T. 2019. “Landscapes of Little Lhasa: Materialities of the Vernacular, Political and Commercial in Urban China .” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 107:24–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.10.017.

- Chan, C., and A. Zhou. 2022. “How to Save Chinatown: Preserving Affordability and Community Service Through Ethnic Retail .” Berkeley Planning Journal 32 (1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.5070/BP332052798.

- Collins, B. 2020. “Whose Culture, Whose Neighborhood? Fostering and Resisting Neighborhood Change in the Multiethnic Enclave .” Journal of Planning Education and Research 40 (3): 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X18755496.

- Cosgrove, D. E. 1998. Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press .

- Czech Statistical Office. 2021. Foriegners in the CR. Czech Statistical Office. https://www.czso.cz/csu/cizinci/1-ciz_pocet_cizincu.

- De Certeau, M. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press .

- Drbohlav, D., and D. Čermáková. 2016. ““A new Song or Evergreen … ?” The Spatial Concentration of Vietnamese Migrants’ Businesses on Prague’s Sapa Site .” Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie 41 (4): 427–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-016-0247-1.

- Drbohlav, D., and D. Dzúrová. 2007. ““Where Are They Going?”: Immigrant Inclusion in the Czech Republic (A Case Study on Ukrainians, Vietnamese, and Armenians in Prague)1 .” International Migration 45 (2): 69–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2435.2007.00404.x.

- Finlay, R. 2019. “A Diasporic Right to the City: The Production of a Moroccan Diaspora Space in Granada, Spain .” Social & Cultural Geography 20 (6): 785–805. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2017.1378920.

- Freidingerová, T., and B. Nováková. 2021. “Civic Engagement and Self-Empowerment of Second-Generation Vietnamese in Czechia .” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 30 (3): 312–337. https://doi.org/10.1177/01171968211040573.

- Friedmann, J. 2002. The Prospect of Cities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press .

- Hall, T. 2009. “The Camera Never Lies? Photographic Research Methods in Human Geography .” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 33 (3): 453–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260902734992.

- Hodge, B. 2017. Social Semiotics for a Complex World: Analysing Language and Social Meaning. Cambridge: Polity .

- Hodge, R., and G. Kress. 1988. Social Semiotics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press .

- Hüwelmeier, G. 2015. “Mobile Entrepreneurs: Transnational Vietnamese in the Czech Republic.” In Rethinking Ethnography in Central Europe, edited by H. Cervinkova, M. Buchowski, and Z. Uherek, 59–73. New York: Palgrave Macmillan .

- Jackson, J. B. 1984. Discovering the Vernacular Landscape. New Haven: Yale University Press .

- Jaworski, A., and C. Thurlow. 2010. Semiotic Landscapes: Language, Image, Space. New York: Continuum .

- Kaplan, D. H. 1998. “The Spatial Structure of Urban Ethnic Economies .” Urban Geography 19 (6): 489–501. https://doi.org/10.2747/0272-3638.19.6.489.

- Khayambashi, S. 2019. “Diaspora, Identity, and Store Signs .” Visual Studies 34 (3): 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/1472586X.2019.1653787.

- Kim, T. S. 2021. “Center and Margin on the Margin: A Study of the Multilayered (Korean) Chinese Migrant Neighborhood in Daerim-Dong, South Korea .” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 120:165–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2021.01.027.

- Krase, J., and T. Shortell. 2011. “On the Spatial Semiotics of Vernacular Landscapes in Global Cities .” Visual Communication 10 (3): 367–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357211408821.

- Kušniráková, T. 2014. “Is There an Integration Policy Being Formed in Czechia? .” Identities 21 (6): 738–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2013.828617.

- Landry, R., and R. Y. Bourhis. 1997. “Linguistic Landscape and Ethnolinguistic Vitality .” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 16 (1): 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X970161002.

- Lee, J. W., and J. J. Lou. 2019. “The Ordinary Semiotic Landscape of an Unordinary Place: Spatiotemporal Disjunctures in Incheon's Chinatown .” International Journal of Multilingualism 16 (2): 187–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2019.1575837.

- Leeman, J., and G. Modan. 2009. “Commodified Language in Chinatown: A Contextualized Approach to Linguistic landscape1 .” Journal of Sociolinguistics 13 (3): 332–362. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2009.00409.x.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell .

- Lou, J. J. 2016. The Linguistic Landscape of Chinatown: A Sociolinguistic Ethnography. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters .

- Lynn, N., and S. J. Lea. 2005. “‘Racist’ Graffiti: Text, Context and Social Comment .” Visual Communication 4 (1): 39–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470357205048935.

- Martínková, Š. 2011. “The Vietnamese Ethnic Group, Its Sociability and Social Networks in the Prague Milieu .” Migration, Diversity and Their Management 8: 133–201.

- Massey, D. 1999. “Imagining Globalization: Power-Geometries of Time-Space.” In Global Futures: Migration, Environment and Globalization, edited by A. Brah, M. Hickman, and M. Mac an Ghaill, 27–44. London: Palgrave Macmillan .

- Mazumdar, S., S. Mazumdar, F. Docuyanan, and C. M. McLaughlin. 2000. “Creating a Sense of Place: The Vietnamese-Americans and Little Saigon .” Journal of Environmental Psychology 20 (4): 319–333. https://doi.org/10.1006/jevp.2000.0170.

- Mumford, L. 1937. “What is a City .” Architectural Record 82 (5): 59–62.

- Neustupný, J. V., and J. Nekvapil. 2003. “Language Management in the Czech Republic .” Current Issues in Language Planning 4 (3-4): 181–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/14664200308668057.

- Nguyen, A. K. 2022. “Degrees of Authenticity .” Linguistic Landscape. An International Journal 8 (1): 85–113. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.21004.ngu.

- Papen, U. 2015. “Signs in Cities: The Discursive Production and Commodification of Urban Spaces .” Sociolinguistic Studies 9 (1): 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1558/sols.v9i1.21627.

- Parzer, M., and F. Astleithner. 2018. “More Than Just Shopping: Ethnic Majority Consumers and Cosmopolitanism in Immigrant Grocery Shops .” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (7): 1117–1135. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2017.1358080.

- Pham, T. H. 2022. “Social Integration Problems of Vietnamese Migrants and Their Descendants Into Czech Society: Empirical Study from Brno, the Czech Republic .” Journal of Identity & Migration Studies 16 (2): 25–43.

- Pham, T. H., and F. Kraus. 2024. “‘Banana’, Vietnamese or Czech?: The Identity Struggles of Second-Generation Vietnamese in the Czech Republic .” Diaspora Studies 17 (1): 85–104.

- Polson, E. 2016. Privileged Mobilities: Professional Migration, geo-Social Media, and a new Global Middle Class. New York: Peter Lang .

- Price, J. M., S. Abdinnour, and D. T. Hughes. 2017. “Del NorteMeets Little Saigon: Ethnic Entrepreneurship on Broadway Avenue in Wichita, Kansas, 1970–2015 .” Enterprise & Society 18 (3): 632–677. https://doi.org/10.1017/eso.2016.76.

- Sassen, S. 2000. “The Need to Distinguish Denationalized and Postnational .” Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies 7 (2): 575–584.

- Scollon, R., and S. W. Scollon. 2003. Discourses in Place: Language in the Material World. Abingdon, UK: Routledge .

- Sharma, B. K. 2021. “The Scarf, Language, and Other Semiotic Assemblages in the Formation of a new Chinatown .” Applied Linguistics Review 12 (1): 65–91. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2019-0097.

- Shortell, T. 2018. “Everyday Mobility: Encountering Difference.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Urban Ethnography, edited by I. Pardo, and G. B. Prato, 133–151. London: Palgrave Macmillan .

- Smith, M. P. 2005. “Transnational Urbanism Revisited .” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 31 (2): 235–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183042000339909.

- Soja, E. W. 1996. Thirdspace. Malden, MA: Blackwell .

- Somashekhar, M. 2019. “Ethnic Economies in the age of Retail Chains: Comparing the Presence of Chain-Affiliated and Independently Owned Ethnic Restaurants in Ethnic Neighbourhoods .” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (13): 2407–2429. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2018.1458606.

- Svobodová, A., and E. Janská. 2016. “Identity Development Among Youth of Vietnamese Descent in the Czech Republic.” In Contested Childhoods: Growing up in Migrancy, edited by M. L. Seeberg, and E. M. Goździak, 121–137. Basel, CH: Springer .

- Szymańska-Matusiewicz, G. 2015. “The Vietnamese Communities in Central and Eastern Europe as Part of the Global Vietnamese Diaspora .” Central and Eastern European Migration Review 4 (1): 5–10.

- Tran, T. T. 2021. “Phoas the Embodiment of Vietnamese National Identity in the Linguistic Landscape of a Western Canadian City .” International Journal of Multilingualism 18 (1): 73–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2019.1604713.

- Vertovec, S. 1999. “Conceiving and Researching Transnationalism .” Ethnic and Racial Studies 22 (2): 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/014198799329558.

- Williams, A. M., and V. Baláž. 2005. “Winning, Then Losing, the Battle with Globalization: Vietnamese Petty Traders in Slovakia .” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 29 (3): 533–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2005.00604.x.

- Zarecor, K. E. 2011. Manufacturing a Socialist Modernity: Housing in Czechoslovakia, 1945-1960. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press .

- Zhang, H., M. F. Seilhamer, and Y. L. Cheung. 2023. “Identity Construction on Shop Signs InSingapore’s Chinatown: A Study of Linguistic Choices by Chinese Singaporeans and New Chinese immigrants .” International Multilingual Research Journal 17 (1): 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2022.2080445.

- Zhao, F. 2021. “Diaspora and Asian Spaces in a Transnational World .” Linguistic Landscape. An International Journal 7 (2): 235–257. https://doi.org/10.1075/ll.20009.zha.

- Zukin, S. 1998. “Urban Lifestyles: Diversity and Standardisation in Spaces of Consumption .” Urban Studies 35 (5-6): 825–839. https://doi.org/10.1080/0042098984574.

- Zukin, S. 2012. “The Social Production of Urban Cultural Heritage: Identity and Ecosystem on an Amsterdam Shopping Street .” City, Culture and Society 3 (4): 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2012.10.002.