Abstract

Objectives: Advanced age is a time shaped by the current experience of physical, social and psychological characteristics associated with living into an eighth decade and beyond and also by reflection upon past experiences. Understanding the specific factors that contribute to ageing well is increasingly important as greater numbers of older people remain living independently in the community and may require targeted and sustainable support to do so. This paper offers a conceptualisation of resilience for advanced age (age 85+), a life stage currently under-researched.

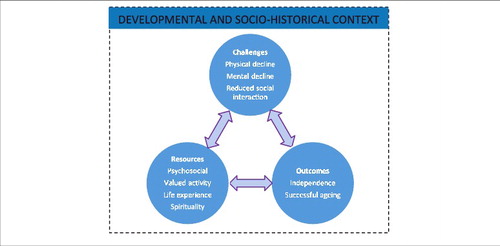

Method: We utilise a developmental and socio-historical context to develop key arguments about adversity, resources and positive outcomes that affect the experience of resilient ageing.

Results: Very late life is characterised by a unique balance between losses, associated with vulnerability and resource restrictions, and potential gains based upon wisdom, experience, autonomy and accumulated systems of support, providing a specific context for the expression of resilience. Post-adversity growth is possible, but maintenance of everyday abilities may be more relevant to resilience in advanced age.

Conclusion: An increasing life-span globally necessitates creative and conscientious thought about wellbeing, and resilience research has the important aim to focus health and wellness on success and what is possible despite potential limitations.

Introduction

In today's complex world, the capacity to navigate challenges inherent to living in the ‘everyday’ without succumbing is an obvious advantage. Traumatic experiences (and those perceived as such) pose additional challenges and reveal varied individual responses (Westphal & Bonanno, Citation2007). A desire to know who adapts to adversity more effectively (and why) has led to ongoing interest in the capacity for resilience – the ability to overcome or bounce back from adversity – with a suggestion that resilience is available to everybody (Bonanno, Galea, Bucciarelli, & Ylahov, Citation2006).

As a construct, resilience has been focused on children and adolescents who certainly encounter numerous trials and tribulations. Given the health and social compromises faced regularly by older adults, with their potential to compound as age advances, however, resilience is especially important in later life. A shift over recent years in the emphasis of health research from limitations and illness to wellness (Antonovsky, Citation1990) is matched by a move in gerontological research to identify and maximise what people are doing well rather than the shortcomings of age (Harris & Keady, Citation2006; Vaillant, Citation2007). Given the fact that people continue to contribute to society in multiple ways into their old age, understanding what support agencies, learning opportunities, and other interventions they need in order to remain capable and resilient to challenges is of obvious importance to a healthy society. This paper provides a conceptualisation of resilience (adversity, resources and outcomes) in very advanced age (the oldest-old).

Although resilience in the old has been reviewed by a few researchers (Allen, Haley, Harris, Fowler, & Pruthi, Citation2011; Stewart & Yuen, Citation2011; Wild, Wiles, & Allen, Citation2013; Windle, Citation2011; Windle, Markland, & Woods, Citation2008), and actively repositioned by others (Felten & Hall, Citation2001; Grenier, Citation2005; Greve & Staudinger, Citation2006; Hoge, Austin, & Pollack, Citation2007; Wild et al., Citation2013), the very advanced age group have been somewhat neglected thus far. Commentary on lifespan and developmental perspectives suggests that positive and negative adaptation is informed by both the presence and absence of resilience factors relevant and variable in different life-stages (Greve & Staudinger, Citation2006). In relation to later life, they contend that maintenance of quality of life (QOL) is related to ongoing resilience processes. Others argue for a more precise positioning of resilience within places of importance for older people and also for a recognition of the subjective needs of older people (Golant, Citation2011; Wild et al., Citation2013). In this view, prior conceptualisations of resilience understate the influence of community interdependence where community members are agents as well as recipients of care.

Along these lines, recognition by health and service providers of the variety of contexts in which adversity is present and within which health care is assumed to be needed has the potential to generate a more positive and ‘coherent’ experience for those who face increasing dependence (Grenier, Citation2005). In one of the few conceptualisations of resilience targeted at advanced age, Felten and Hall (Citation2001) offer a gendered vision; however, because unifying policy implementation may be set by age, a more useful conceptualisation would position age as the key defining feature. Despite an explicit connection to social ageing, we believe that resilience work has an opportunity to align itself more clearly with challenges and resources relevant to people of advanced age.

Resilient outcomes result from the mobilisation of resources in response to adversity (Masten, Citation2001). In , we propose an age-related model whereby a developmental and socio-historical context (which includes physical and social life-stage and cohort factors) surrounds and defines these features.

This paper argues several points of difference with respect to the manifestation and operation of resilience in the oldest-old relative to younger old (and younger groups in general). First, that the challenges the oldest-old face are age-related, second, that the influence of situational and social factors on resilience is greater in advanced age, and third, that as health declines (as age increases), the capacity to achieve the same activities alters and means that tasks and outcomes may be valued differently than for younger people. We begin this discussion by briefly outlining what is meant by resilience. The main portion of the paper is then devoted to describing the advanced age life-stage as a context that shapes how the oldest-old act and interact and what resilience might mean in this context. We comment on pertinent developmental perspectives and discuss what is different about the challenges and potentially mitigating resources of advanced age. We finish by returning to our conceptualisation to argue that the experiences and attainments associated with living into advanced age are central to understanding when and how resilience emerges among the oldest-old.

What is resilience?

Research on individual resilience stretches back to the 1950s when two seminal studies involving the children of schizophrenic parents (Rutter, Citation1979; Werner & Smith, Citation1982) showed that it was possible for children to achieve relatively unaffected futures despite seemingly insurmountable odds. This finding countered early assumptions that extreme disadvantage would inevitably have detrimental effects and that the absence of negative symptoms was rare and exceptional.

Broadly, resilience is described as the ability to achieve, retain, or regain a level of physical or emotional health after devastating illness or loss (Felten & Hall, Citation2001). Physical and social losses are of high importance to positive outcomes for the oldest-old (Smith, Citation2000). Other work suggests a difference between resilience and recovery, the distinguishing feature being the length of time to improvement, recovery implying improvement after a deep and long-term reduction in function and resilience being demonstrated when the impact of adversity is shorter term or when there is no discernible functional decline at all (Bonanno, Citation2004). These approaches consider resilience to be about homeostasis, or maintenance of normal competencies under adverse conditions. Conversely, resilience conceived as ‘an extraordinary and positive response to a challenge or stressor’ (Hochhalter, Smith, & Ory, Citation2011) suggests that rather than merely ‘getting through’ a hard time, a resilient response denotes improved functioning. Although improvement is possible in advanced age, the extent of growth may be less than is evident in younger populations or may be modified with age (Baltes, Citation1997).

Response approaches aside, various life-stage and cohort factors affect how people manage new experiences. Positive resources, also described as a ‘resilience repertoire’ (Clark, Burbank, Greene, Owens, & Riebe, Citation2011), are thought to shield individuals against setbacks. Sub-optimal resources, alternatively, may jeopardise adaptive outcomes (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, Citation2000). The constant balancing of protective and risk factors determines the level of resilience in any given situation. Both adversity and protective resources are influenced by the degree of exposure to them and their significance to the individual. Protective resources may either maintain or enhance competence in stressful situations, or reduce adversity. It seems most likely that a combination of protective factors has a synergistic effect whereby greater benefit is possible together versus factors considered alone (Luthar, Citation1993).

Overall, resilience denotes a complex relationship between adversity, protective and risk factors and a positive behavioural response (Antonovsky, Citation1974, Citation1983). Resilience may be innate (Masten, Citation2001) and, importantly, the process of resilience in aged individuals is one involving interaction and feedback specific to their life stage and cohort factors as discussed below.

What is advanced age?

A discussion of resilience amongst the oldest-old is facilitated when recalling who this group of individuals are. A global per capita population increase plus ever-improving medical techniques and increasing investment in community service means that people are living longer than ever before, with the oldest increasing in number faster than any other age group (Kinsella & Phillips, Citation2005). The oldest-old (age 85 plus in developed countries) comprises 50% of the people who attain ages 50 or 60 (Baltes & Smith, Citation2003) and constitutes more women, reduced social interaction, higher dependency (Bowling & Browne, Citation1991) and increased healthcare spending (Felten & Hall, Citation2001). But advanced-agers are also the most heterogeneous group (Blood & Bamford, Citation2010) with the greatest variability in physical and mental health (Wu, Schimmele, & Chappell, Citation2012). Moves to characterise the heterogeneity of people living beyond age 65, previously expressed as a single ‘old’ cohort, have been advanced by theories such as Baltes theory of ‘incomplete architecture’ which describes an increasing mismatch between gains and losses as the human body ages (Baltes, Citation1997). Given evidence for some people of good psychological health in very old age despite physical compromise (Scheetz, Martin, & Poon, Citation2012), however, other processes appear to offset losses and enable the maintenance of good functional ability. Some researchers have suggested that people may move in and out of health states subject to the risks and resources that are available to them (Verbrugge & Jette, Citation1994). Advanced agers have been exposed to more events and particular challenges in development but have also had more time to develop effective coping methods.

It is not only the ageing adults themselves that are heterogeneous; the contexts in which they live also vary widely. Within the intersecting spaces of household, family, neighbourhood and community, particularly household and family spaces, where the oldest-old spend much of their time, mental and physical health concerns operate in conjunction with social concerns (Smith, Citation2000; Wild et al., Citation2013). Variability exists in decision-making ability, motivational practices, the importance placed upon daily activities, and access to social support. A more informed understanding of this socio-historical context is essential to maximising the well-being of the oldest-old who face an increasing timespan living with disability.

Resilience is context-specific – advanced age as a context

Although some resilience resources may be effective in multiple contexts, the existence of an overall resilience capacity is unlikely; resilience seems responsive to specific situations in both an inter-personal (Hochhalter et al., Citation2011) and intra-personal (Luthar et al., Citation2000) sense. A developmental approach to resilience suggests that when people of different ages face the same situation, they may have different experiences of stress. For example, few research studies in advanced age assess financial stress as an adversity. That people in advanced age rate financial stress differently than younger people may reflect previous experiences in managing frugality (Hill, Kellard, Middleton, Cox, & Pound, Citation2007). The perception of adversity has also been found to differ between the agent and health professionals and researchers. Feelings of vulnerability in advanced age, for instance, appear to be triggered, not by the physical, psychological and social characteristics that are related to frailty, as clinicians or researchers might assume, but by fear of the unknown, e.g. sudden health decline and dependence (von Faber & van der Geest, Citation2010) and anxiety about reduced personal control (Abley, Bond, & Robinson, Citation2011).

Second, the differences between those who do well and those who do not in the same situation is partially dependent on the resources the individual can draw upon. Resources are thought to be different in advanced age, with psychosocial resources more accessible and other resources perhaps less so (Jopp & Rott, Citation2006). But resources, too, are context-dependent (Kaplan, Citation2002). Social support, for example, is constituted differently for people living alone than for those living intergenerationally. Moreover, although having accessible social support may be generally protective, service providers, while well-intentioned, do not always accurately determine either subjective or objective need. For some people, living alone is a preference and the presence of care workers in their home adds stress rather than value. The degree to which social support resembles social capital (the value ascribed to social networks) depends upon how that support is perceived by the recipient and how appropriately it is utilised. Age and the accumulation of prior experience are likely to be significant in influencing whether a resource is experienced as positive.

Third, strategies employed by older people to maintain competence in activities they see as important are common. ‘Meaningful ageing’ (Stuckey, Citation2006) is now a central focus in gerontology work and seeing meaning in life experiences is a key component of resilience for ageing adults. Ageing is also a whole-of-life process (Goulet & Baltes, Citation1970) and, as such, adaptation along the way to facilitate desired and meaningful outcomes is actively sought. Now widely recognised for its utility in explaining behavioural decisions within gerontology, the theory of Selection and Optimisation with Compensation (Baltes & Baltes, Citation1990) proposes that when faced with limitations, older people select or retain fewer and more meaningful activities, optimise the activities they do well, and/or compensate for the losses they face by altering the way in which they accomplish tasks. People in advanced age recognise and actively strategise to manage losses and re-conceptualise them into a perception of ageing that maximises what they can do rather than what they cannot (von Faber & van der Geest, Citation2010). Optimal individual functioning in response to age-related demands is theorised as an ecological approach to the person–environment interaction (Lawton & Nahemow, Citation1973; Satariano, Citation2006).

Misunderstanding the components of resilience in any context risks placing importance on activities that do not matter. For example, valuation studies suggest that the oldest-old, in contrast to the young-old, seem to value social contact by phone over face-to-face support (Jopp, Rott, & Oswald, Citation2008), which may reflect a changing set of values with age and a psychological adaptation to declining abilities (Scheetz et al., Citation2012). In contrast to definitions of resilience that denote thriving, in advanced age, loss management may be as important as regaining previous levels of function (Greve & Staudinger, Citation2006). Indeed, research suggests that the ability to keep going, i.e. to maintain activities that are both functional and meaningful, despite potentially significant challenges, may better define success for this age group than making and striving to achieve new goals (Ebner, Freund, & Baltes, Citation2006).

While the literature about contributions to resilience is growing steadily, empirical studies which focus on, or even include, people of very advanced age remain scarce. Little is known about age-related changes in the manifestations of resilience as few studies have compared resilience between older and younger populations or indeed between the oldest-old and younger old. However, the few relevant findings are consistent with the notion that there is considerable heterogeneity in late life (Jopp et al., Citation2008; Kotter-Gruhn, Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn, Gerstorf, & Smith, Citation2009; Kunzmann, Little, & Smith, Citation2000; Schindler, Staudinger, & Nesselroade, Citation2006; Smith & Baltes, Citation1997; Windle, Woods, & Markland, Citation2010) and that resilience is either stable or increases with age (Cherry, Silva, & Galea, Citation2009; Shen & Zeng, Citation2010; Staudinger & Fleeson, Citation1996; Zeng & Shen, Citation2010).

Antecedents to resilience in advanced age: adversity and resources

Advanced age provides a relevant context for resilience research in a number of ways. We might ask whether the exposure to (or experience of) adversity is different for the oldest-old than it is for younger old, as well as consider whether different resources that might mitigate harm are available to the oldest-old. While good physical and mental health are amongst the most valued factors in maintaining wellness, older adults are aware of their lives changing and of meaningful activities becoming more difficult (Hill et al., Citation2007). Indeed, the changes that accompany and comprise ageing might themselves create an adversity of sorts, although Hildon, Smith, Netuveli, and Blane (Citation2008) caution against focusing on ageing rather than changes. Whilst ordinary everyday pursuits might offer a ‘comfortable familiarity’, whereby awareness of one's limitations is accepted, they also expose potentially challenging age-related changes (Wright St-Clair, Kerse, & Smythe, Citation2011). Neither adversities nor protective and risk factors have been systematically analysed within the oldest-old (Hildon et al., Citation2008). Below we reflect upon the unique challenges and resource experiences available to this group, drawing from what is known about advanced age in this area as well as the literature addressing resilience in older age more broadly.

Adversity in advanced age

Losses, particularly related to physical health and social networks, seem central to the oldest-old (Smith, Citation2000). Chronic disease and disability are major contributors to hospitalisation and institutionalisation in advanced age, as well as the need for home care (Bonanno, Citation2004; Ostir et al., Citation1999). Physical and social aspects of ageing are highly connected. People with greater physical dependence tend to rely more heavily upon family and friends in times of need and often live geographically close to these sources of informal support (Bowling & Browne, Citation1991). But, unfortunately, while the need for informal and formal instrumental support may increase, loss of significant others (e.g. spouses) is also higher in advanced age, reducing access to this personal reserve. Similarly, vulnerability to poor health outcomes, which is more common in advanced age, is affected by social influences and positive and negative aspects of human agency (Schröder-Butterfill & Marianti, Citation2006); that is, the exposure to and ability to cope with risk affects an individual's susceptibility to harm. A qualitative study of successful ageing found that while current or projected health declines were of major concern to octogenarians, it was the effect of disability on social opportunities that caused the most distress (von Faber & van der Geest, Citation2010). Functional ability, therefore, seems to negatively affect overall capacity rather than just the achievement of immediate activities. With increasing limitations in mobility and decreasing access to informal support systems, opportunities for the very old to engage socially also become more elusive.

Negotiating ordinary everyday activities may be a source of stress modifiable by resilience resources (Ong, Bergeman, & Boker, Citation2009). Paradoxically, however, although increasing losses and compromises in advanced age should translate to increased stress, older adults tend to report less frequent and less severe daily stressors (Almeida & Horn, Citation2004). Daily stress has been investigated as a dependent variable in studies of adaptation for older people (Diehl & Hay, Citation2010; Ong, Bergeman, Bisconti, & Wallace, Citation2006) but rarely specifically in those of advanced age. One study, finding age-related effects in stress-reporting, hypothesised that stress experienced over time facilitates a more balanced perspective of new stresses and that the effects of stress are actively minimised by those in poorer health in order to avoid further compromise (Aldwin & Yancura, Citation2010). Despite differing perceptions of stress and although potentially impacted by different coping strategies, responses to routine stressors could be similarly adaptive for the oldest-old compared to others (Aldwin, Sutton, Chiara, & Spiro, Citation1996). Serious trauma, such as environmental disasters, as have occurred across the globe in recent times, may also compound already reduced social circumstances for the oldest-old. There are complexities for older people around receipt of care in times of crisis; nevertheless, resilience is evident in reports of older adults’ response to disasters (Davey & Neale, Citation2013) and they may even actively contribute to disaster relief (Cherry et al., Citation2009; Davey & Neale, Citation2013).

As well as personal complaints, inter-personal social and community factors are more salient in advanced age compared to other ages (Luthar et al., Citation2000). The coping literature suggests that older respondents, compared to others, perceive stressors that are experienced by their significant others, particularly family members, as more salient than egocentric ones (Aldwin & Yancura, Citation2010).

Resources in advanced age

In addition to generating some age-normative challenges and stressors, very late life is also a time in which the resources needed for resilient responding vary. Adaptive resources, while similar across the lifespan, may be weighted differently in advanced age (Connor & Davidson, Citation2003; Hoge et al., Citation2007; Kumpfer, Citation1999; Lamond et al., Citation2009). For example, informal social support is a key determinant of independence and well-being amongst the oldest-old, more so than in other age groups. Key social, psychological and attitudinal resources relevant to the understanding of resilience in advanced age are described below, with the focus resting upon possible differences between the oldest-old and younger old.

Social support – informal and formal, emotional and instrumental, received and given – is a central resilience resource in advanced age. Social support operates protectively by providing help, companionship, advice or advocacy, and by validating an individual's worth (Fiori, Smith, & Antonucci, Citation2007). Informal support is usually supplied by family members (Bowling & Browne, Citation1991). In ageing studies, greater resilience is associated with greater formal support (Netuveli, Wiggins, Montgomery, Hildon, & Blane, Citation2008), higher quality social relationships (Hildon, Citation2009), and more frequent social participation (Blane, Wiggins, Montgomery, Hildon, & Netuveli, Citation2011).

Interestingly, studies of spousal loss in older men have found significant levels of resilience (Bennett, Citation2010; Bonanno et al., Citation2002; Moore & Stratton, Citation2002), despite the loss of a key supporter. Hardiness (O'Rourke, Citation2004) and sense of control (Ott, Lueger, Kelber, & Prigerson, Citation2007) are other resources found to speed up adjustment to widowhood. Greater pre-loss acceptance of death (Bonanno et al., Citation2002) and preparation for death (Ott et al., Citation2007) may also help explain high resilience to widowhood in advanced age, as bereavement is often predated by ill health which is more commonly experienced as age advances.

Equally, a positive perception of the self might contribute to resilience by helping to mitigate the stigma of ageing as a period of decline (Brandtstadter & Greve, Citation1994). Time to adapt to age-related changes is important to survival into advanced age (Kotter-Gruhn et al., Citation2009) and the oldest-old do seem to have higher self-rated physical health when they feel younger (Infurna, Gerstorf, Robertson, Berg, & Zarit, Citation2010; Liang, Citation2014). In another study, although visual impairment was associated with high rates of depression in nursing home residents (42.5%), adaptation to nursing home living decreased depression (Ip, Leung, & Mak, Citation2000).

With increasing age, control over external events is decreased (Lachman, Rosnick, & Rocke, Citation2009) and may be reflected in a reduction of assimilative (active) coping as the costs required to actively cope are perceived as too high to bear (Golant, Citation2015). The more emotion-focused coping style employed by the oldest-old (accommodative coping) seems to be most effective for events where problem-focused coping options are few; such events may be more likely in very advanced age. The Maturation hypothesis suggests that mature and effective coping styles and greater wisdom may buffer against severe late-life stress (Blazer & Hybels, Citation2005). ‘Meaning-based coping’ sustains positive as opposed to negative emotional responses to stressful situations and may be particularly relevant to advanced-agers achieving resilience (Folkman, Citation1997). An holistic view of ageing suggests that social productivity is also valued by older people and aspired to as a means of maintaining wellness or resilience (Wiles, Wild, Kerse, & Allen, Citation2012). Engaging in valued activities provides meaning (Baltes & Baltes, Citation1990) and may tap into the advantages of being socially connected.

There is growing evidence that previous exposure to stressful events also contributes to the manifestation of resilience during later events (Jennings, Aldwin, Levenson, Spiro, & Mroczek, Citation2006). It works by providing a reference for positive action, empowering the individual through enhancing self-efficacy, or possibly by inoculating against stressful effects (Aldwin et al., Citation1996). People in advanced age have a unique history to draw from when adapting to challenges. An 85 year old in 2015, for example, would have been born in 1930 and would have lived through global, formative experiences such as the Great Depression, WWII and social movements after WWII (Consedine, Magai, & Krivoshekova, Citation2005). Reflecting upon past life events is an active strategy employed by older people when facing adversity; indeed, life review involves connecting what was to what is in the experience of very old people (Gattuso, Citation2003).

Finally, adversity and resilient resources are effective right up until the end of life. Qualitative work with people living with terminal illness shows that reliance upon effective past strengths, meaningful life-review, and spiritual and social connections provide some relief from the negative effects of illness and the dying process, or negotiating through the health system at the end of life (Nakashima & Canda, Citation2005). Octo- and nona-genarians have a more accepting perspective of death than the younger old and feel comforted by religious and spiritual perspectives (Clarke & Warren, Citation2007), contributing more closely to fulfilment of their personal potential at their end of life.

Conceptualisation of resilience in advanced age

So, adults in advanced age are usefully characterised in terms of the specific challenges they face as well as the resources they have to manage them. These two factors combine to offer insight into resilience in advanced age, an important consideration given that degrees of resilience may hold the key to health improvement (Verbrugge & Jette, Citation1994); those with greater resilience improve faster in the face of adversity.

The foregoing discussion shows that although a disease-free old age is unlikely for most people (Hildon, Montgomery, Blane, Wiggins, & Netuveli, Citation2009), advanced age does not preclude the existence of resilience. Developmental psychology's suggestion that older peoples’ dignity is at risk due to the drastic difference between the resources available to them and biological decline (Baltes & Smith, Citation2003) is countered by evidence that QOL, a positive attitude and age-related competencies exist amongst the oldest-old. Resilience may even be higher in advanced age than at other ages (Staudinger & Fleeson, Citation1996), perhaps because life experience plays a major part in resilient outcomes. In conceptualising resilience within the context of advanced age, we have highlighted the importance of the developmental and socio-historical context that surrounds adversity, resource availability and mobilisation and positive adaptation. The subjective evaluation of these elements is key, but perhaps the most important difference in the way resilience operates for people of advanced age compared to others is the length of time the oldest-old have had to accumulate experience. Four points of difference are expanded below.

Resilience is an ongoing process

The resilience process mobilises existing internal and external factors to reduce the negative effects of stressors and achieve positive outcomes, be they maintenance or improvement. In the developmental process, these elements are constantly updated through conscious or unconscious internalisation of experiences and thus they change over time (Luthar et al., Citation2000). Even in later life, positive outcomes, such as successful coping, are assimilated into one's psyche and build upon one's world view to become a future referent (Nakashima & Canda, Citation2005; Richardson, Citation2002). Through their interactive nature, the elements also feed into each other. Wherever competencies are able to confer advantage, they contribute to a happier and more resilient ageing experience.

The perception of adversity is dependent upon experience and meaning

People in advanced age have had more time and opportunity to be exposed to stresses and to develop resources to deal with them. Someone now in their 80s is experiencing unique age-related conditions and cohort effects, as well as coping with societal stereotypes of ageing. Significant world events have occurred that will not be part of current generational experiences. However, surviving trauma can have benefit as well as loss; for example, by increasing confidence in one's coping ability. Data suggest that WWII veterans who experienced the greatest adversity during the war showed the greatest improvement in resilience in later life (Elder & Clipp, Citation1989).

Consistent with Luthar's argument that adaptation to high-stress situations is more reflective of resilience, with increasing age and frailty, managing ordinary daily tasks represents an ongoing challenge which can be interpreted as a high-stress situation (Guilley et al., Citation2008). However, as importantly, the reality of normal life changes for the oldest-old may be accepted in the light of past experiences as even people with seemingly low resilience express pride in having once been strong and active. Their comparison with others who they think are worse off may be a ‘normalising’ effect of growing older (Aléx & Lundman, Citation2011). Thus, the subjective meaning ascribed to an experience also influences its impact. Moreover, what is adverse in one situation may be protective in another for the same person and may vary across the life course (Elder & Clipp, Citation1989). For example, although personal life investment is generally considered to be adaptive, low personal life investment was protective of a positive perception of ageing, given higher somatic risk in the very old, supporting the notion of selectivity of activities as age and disability increase (Staudinger, Freund, Linden, & Maas, Citation1999). Factors such as social support and the memory of past actions that work in favour of resilience when they are positive can create stress when they are poor or lacking (Aléx & Lundman, Citation2011).

In addition to the advantage of experience, the perception of challenge is affected by current health state, self-efficacy and other adaptive behaviours. That is, those who are more compromised (physically or otherwise, but commonly as a function of age) may under-rate adversity because they cannot afford additional compromise; the knowledge that one has effective resources and that positive outcomes are possible (self-efficacy) may mitigate the strength of a stressor; or, because older adults already creatively manage routine activities, when faced with the same stressors as younger people, the perception of hardship is likely to be lower.

Although the same resources may be protective, they should be weighted differently

Even towards the end of life, resilient responses to adversity may be enhanced by a history of positive learning experiences, multifaceted personal strengths and the ability to draw upon accumulated and new systems of support. Living to a greater age builds up an asset pool. However, because perceived adversity and opportunities to acquire resources are different in advanced age, different protective resources are required. The influence of situational and social factors on resilience is likely greater in advanced age, suggesting the need for appropriate weighting on factors such as life history and external support from other people. Such factors have been identified as conferring resilience in longitudinal studies of ageing, which also focus on age-relevant adversities such as physical impairments and bereavement (Nygren, Citation2006; Staudinger et al., Citation1999).

Resilient outcomes in advanced age are about maintenance of functional competence

Although various outcomes are possible in dealing with any adverse situation, maintaining competence and independence may be the most salient outcomes for the oldest-old whose goals tend to be focused on immediate needs. Independent living is a goal for many but how that is achieved rests upon an individual's values and what makes sense to them. That is, although physical improvements, such as shifting from a sedentary to a more active lifestyle, may demonstrate thriving or resilient growth (Richardson, Citation2002), others have found that, in advanced age, the ability to retain activities that are comfortable and hold importance in daily life may offer a sense of security to the older person (Wright St-Clair et al., Citation2011). Indeed, ‘resilient ageing’, with a focus on subjectively achievable goals, seems more realistic for people of advanced age (Harris, Citation2006).

The fact that individuals are more concerned about how they function than what they are able to achieve reflects the concept that actions are readily translated into functional reality for people in advanced age. In this sense, function is broadly defined as both physical and emotional competence to achieve subjectively important resilient outcomes. Resilient outcomes hinge upon the person's own experience of environmental challenges and decisions are made within that space that utilise available resources to enhance congruence between the person and their environment (Golant, Citation2015).

Advanced agers who are aware of their health changes and needs may be able to actively influence their own health outcomes. Research is consistent with the notion that advanced age is not a barrier to a personal investment in health (Hall, Chipperfield, Heckhausen, & Perry, Citation2010) or to subjective well-being (Lawton, Kleban, Rajagopal, & Dean, Citation1992). Consideration of the views and specific motivations of the people who are approaching very old age, then, is essential to an appropriate conceptualisation of resilience.

In summary, the developmental and socio-historical context affects the exposure to and experience of, measurement of, and impact of adversity and resilience. Our conceptualisation underlines the importance of individual approaches to wellness at best and cohort-focused approaches at a minimum. Awareness by health professionals and service providers of the potential of the oldest-old to maintain competency despite health challenges has the potential to improve their QOL and lead to more ‘coherent’ health treatments and end-of-life processes.

Implications for practice

There are many ways to maximise resilience to enable best outcomes for those in advanced age but resources have to be focused in the right place to be effective, targeting what is possible and what is important. Communities can promote resilience by validating advanced age as a productive time rather than a burden. This includes recognising the place of older people in relation to productive activity such as part-time work, and maintaining opportunities for social engagement outside the home and enabling access to these. Interventions, furthermore, need to actively seek and include the oldest-old who are often living alone.

The oldest members of society argue that involvement in service is a key component of their resilience (Stanford, Citation2006). Recognising that they often have the time to give to others in productive and caring activities can help to alleviate some of the burden on family and community members caring for dependents. The concept of ‘lifelong learning’ means that new experiences have the potential to inform current self-perceptions and life-view (Pincas, Citation2014) and contribute to adaptation. Encouraging age-directed learning into advanced age includes more than formal learning but also skills training, volunteering and learning new creative activities. Learning opportunities offered by local councils, charities, voluntary organisations and self-help groups such as the U3A have the potential to maximise civic involvement and productivity.

The most resiliently ageing older adults might be the ones who are able to review their lives as active coping strategies. An emphasis on emotion-focused coping suggests that interventions could focus on boosting emotional intelligence (Allen et al., Citation2011). Given, also, that many stressors in late life have psychological impact (chronic illness, dependence, loss, loneliness), this means encouraging positive emotional reappraisals of events that have caused negative feelings, thereby shifting the consequences to more positive ones. On the other hand, efficacious outcomes can also be achieved by encouraging largely passive older people, aiming to simply minimise their distress, to expand their range of manageable activities or to accept problem-focused action from others (Birkeland & Natvig, Citation2009). As well as identifying strengths and resources that older people have, when resources are limited, vulnerabilities (tempered by acknowledgment of the needs and motivations as expressed by the individual) can be alleviated by providing ‘place resilience’ through age-appropriate architectural and urban design (Golant, Citation2015) and sound community-based support and formal homecare services.

That adversity and resources are different in advanced age has important implications for the measurement of resilience. Multiple methods have been used to measure resilience, including self-report resilience scales. However, measures that appear to assume that resilience is an age-neutral construct with largely psychological components should be used cautiously given the situation-specificity and multidimensionality of resilience and the likelihood that both challenges and resources fluctuate in age-normative ways. For example, the oft-cited Resilience Scale (Wagnild & Young, Citation1993) assesses only internal characteristics, omitting the valuable contribution of other mechanisms of support that are important to those in advanced age. Other scales are similarly incomplete with little attention paid to context-specific factors. Nor have resilience scales been developed specifically for people in advanced age. Such instruments should attend to the specific challenges faced by ageing adults as well as assessing the maintenance of function rather than exclusively concentrating on improvement. Scales of any sort are problematic given the complex nature of resilience. Other methods of measurement, such as resource clustering, show promise (Smith & Baltes, Citation1997).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the contexts through which adversity is experienced and in which it is expressed are increasingly central to understanding resilient outcomes. Above, we have suggested that the developmental and socio-historical background of advanced age is usefully conceptualised as a resilience-relevant context; one which recognises the heterogeneity of what was once thought of as ‘old’ age. An appropriate conceptualisation of late-life resilience should emphasise subjectivity and life experience in relation to the challenges, resources and adaptive outcomes that typically occur for these individuals. This conceptualisation has been necessarily constrained as the topic is broad and complex. We have tried to incorporate examples that reflect the most salient aspects of advanced ageing and how they combine to create a specific context in which resilience may manifest. Coupled with strategies the older person can undertake to maximise their resilience, and spurred on by the increasing global lifespan, developing a better understanding of resilience in advanced age has the capacity to benefit older people through more focused service development, intervention development, and successful ageing strategies. In fact, resilience thrives upon adversity and may constitute a process by which people can make the most of their longer lives and live them out with dignity.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abley, C., Bond, J., & Robinson, L. (2011). Improving interprofessional practice for vulnerable older people: Gaining a better understanding of vulnerability. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 25, 359–365. doi:10.3109/13561820.2011.579195

- Aldwin, C.M., Sutton, K.J., Chiara, G., & Spiro, A., III. (1996). Age differences in stress, coping, and appraisal: Findings from the Normative Aging Study. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 51B(4), P179–P188. doi:10.1093/geronb/51B.4.P179

- Aldwin, C.M., & Yancura, L.A. (2010). Effects of stress on health and aging: Two paradoxes. California Agriculture, 64(4), 183–188. doi:10.3733/ca.v064n04p183

- Aléx, L., & Lundman, B. (2011). Lack of resilience among very old men and women: A qualitative gender analysis. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice: An International Journal, 25(4), 302–316.

- Allen, R.S., Haley, P.P., Harris, G.M., Fowler, S.N., & Pruthi, R. (2011). Resilience: Definitions, ambiguities, and applications. In B. Resnick, L.P. Gwyther, & K.A. Roberto (Eds.), Resilience in aging: Concepts, research, and outcomes. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media.

- Almeida, D.M., & Horn, M.C. (2004). Is daily life more stressful during middle adulthood? [References]. In O.G. Brim, C.D. Ryff, & R.C. Kessler (Eds.), How healthy are we?: A national study of well-being at midlife (pp. 425–451). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press

- Antonovsky, A. (1974). Conceptual and methodological problems in the study of resistance resources and stressful life events. In B.S. Dohrenwend & B.P. Dohrenwend (Eds.), Stressful life events: Their nature and effects (pp. 245–258). New York, NY: Wiley.

- Antonovsky, A. (1983). The sense of coherence: Development of a research instrument. Newsletter and Research Reports, 1, 1–11.

- Antonovsky, A. (1990). The salutogenic model of health. In R.E. Ornstein & C. Swencionis (Eds.), The healing brain: A scientific reader (pp. 231–243). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Baltes, P.B. (1997). On the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny: Selection, optimization, and compensation as foundation of developmental theory. American Psychologist, 52(4), 366–380.

- Baltes, P.B., & Baltes, M.M. (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In P.B. Baltes & M.M. Baltes (Eds.), Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences (pp. 1–34). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Baltes, P.B., & Smith, J. (2003). New frontiers in the future of aging: From successful aging of the young old to the dilemmas of the fourth age. Gerontology, 49(2), 123–135. doi:10.1159/000067946

- Bennett, K.M. (2010). How to achieve resilience as an older widower: Turning points or gradual change? Ageing and Society, 30(3), 369–382. doi:10.1017/S0144686×09990572

- Birkeland, A., & Natvig, G.K. (2009). Coping with ageing and failing health: A qualitative study among elderly living alone. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 15(4), 257–264. doi:10.1111/j.1440-172X.2009.01754.x

- Blane, D., Wiggins, R.D., Montgomery, S.M., Hildon, Z., & Netuveli, G. (2011). Resilience at older ages: The importance of social relations and implications for policy. London: ICLS Occasional Papers Series.

- Blazer, D.G., & Hybels, C.F. (2005). Origins of depression in later life. Psychological Medicine, 35, 1–12. doi:10.1017/S0033291705004411

- Blood, I., & Bamford, S.-M. (2010). Equality and diversity and older people with high support needs. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Bonanno, G.A. (2004). Loss, trauma, and human resilience: Have we underestimated the human capacity to thrive after extreme adversive events? American Psychologist, 59(1), 20–28.

- Bonanno, G.A., Galea, S., Bucciarelli, A., & Ylahov, D. (2006). Psychological resilience after disaster: New York city in the aftermath of the September 11th terrorist attack. Psychological Science, 17, 181–186.

- Bonanno, G.A., Wortman, C.B., Lehman, D.R., Tweed, R.G., Haring, M., Sonnega, J., … Nesse, R.M. (2002). Resilience to loss and chronic grief: A prospective study from preloss to 18-months postloss. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(5), 1150–1164. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.5.1150

- Bowling, A., & Browne, P.D. (1991). Social networks, health, and emotional well-being among the oldest old in London. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 46(1), S20–S32.

- Brandtstadter, J., & Greve, W. (1994). The aging self: Stabilizing and protective processes. Developmental Review, 14, 52–80.

- Cherry, K.E., Silva, J.L., & Galea, S. (2009). Natural disasters and the oldest-old: A psychological perspective on coping and health in late life. In K.E. Cherry (Ed.), Lifespan perspectives on natural disasters. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media.

- Clark, P.G., Burbank, P.M., Greene, G., Owens, N., & Riebe, D. (2011). What do we know about resilience in older adults? An exploration of some facts, factors, and facets. In B. Resnick, L.P. Gwyther, & K.A. Roberto (Eds.), Resilience in aging: Concepts, research, and outcomes. New York, NY: Springer Science+Business Media.

- Clarke, A., & Warren, L. (2007). Hopes, fears and expectations about the future: What do older people's stories tell us about active ageing? Ageing and Society, 27, 465–488. doi:10.1017/S0144686×06005824

- Connor, K.M., & Davidson, J.R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. doi:10.1002/da.10113

- Consedine, N.S., Magai, C., & Krivoshekova, Y.S. (2005). Sex and age cohort differences in patterns of socioemotional functioning in older adults and their links to physical resilience. Ageing International, 30(3), 209–243.

- Davey, J.A., & Neale, J. (2013). Earthquake preparedness in an ageing society: Learning from the experience of the canterbury earthquakes. Wellington: Earthquake Commission.

- Diehl, M., & Hay, E.L. (2010). Risk and resilience factors in coping with daily stress in adulthood: The role of age, self-concept incoherence, and personal control. Developmental Psychology, 46(5), 1132–1146. doi:10.1037/a0019937

- Ebner, N.C., Freund, A.M., & Baltes, P.B. (2006). Developmental changes in personal goal orientation from young to late adulthood: From striving for gains to maintenance and prevention of losses. Psychology and Aging, 21(4), 664–678. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.21.4.664

- Elder, G.H., Jr., & Clipp, E.C. (1989). Combat experience and emotional health: Impairment and resilience in later life. Journal of Personality, 57(2), 311–341. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1989.tb00485.x

- Felten, B.S., & Hall, J.M. (2001). Conceptualizing resilience in women older than 85: Overcoming adversity from illness or loss. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 27(11), 46–53.

- Fiori, K.L., Smith, J., & Antonucci, T.C. (2007). Social network types among older adults: A multidimensional approach. Journal of Gerontology, 62B(6), 322–330.

- Folkman, S. (1997). Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science and Medicine, 45, 1207–1221.

- Gattuso, S. (2003). Becoming a wise old woman: Resilience and wellness in later life. Health Sociology Review, 12, 171–177.

- Golant, S.M. (2011). The quest for residential normalcy by older adults: Relocation but one pathway. Journal of Aging Studies, 25, 193–205. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2011.03.003

- Golant, S.M. (2015). Residential normalcy and the enriched coping repertoires of successfully aging older adults. The Gerontologist, 55(1), 70–82. doi:10.1093/geront/gnu036

- Goulet, L.R., & Baltes, P.B. (Eds.). (1970). Life-span developmental psychology: Research and theory. New York, NY: Academic Press Inc.

- Grenier, A.M. (2005). The contextual and social locations of older women's experiences of disability and decline. Journal of Aging Studies, 19, 131–146. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2004.07.003

- Greve, W., & Staudinger, U.M. (2006). Resilience in later adulthood and old age: Resources and potentials for successful aging. In D. Cicchetti & D.J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology ( Vol. 3: Risk, disorder, and adaptation, 2nd ed., pp. 796–840). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Guilley, E., Ghisletta, P., Armi, F., Berchtold, A., Lalive d'Epinay, C., Michel, J.-P., … de Ribaupierre, A. (2008). Dynamics of frailty and ADL dependence in a five-year longitudinal study of octogenarians. Research on Aging, 30(3), 299–317. doi:10.1177/0164027507312115

- Hall, N.C., Chipperfield, J.G., Heckhausen, J., & Perry, R.P. (2010). Control striving in older adults with serious health problems: A 9-year longitudinal study of survival, health, and well-being. Psychology & Aging, 25(2), 432–445. doi:10.1037/a0019278

- Harris, P.B. (2006). Resilience: An undervalued concept in the debate about successful aging. Paper presented at the 59th annual scientific meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, Dallas, TX.

- Harris, P.B., & Keady, J. (2006). Editorial. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 5(1), 5–9. doi:10.1177/1471301206059751

- Hildon, Z. (2009). Resilience and quality of life at older ages: Mixed methods analysis of the Boyd Orr Cohort (Doctoral dissertation). University of London, London.

- Hildon, Z., Montgomery, S.M., Blane, D., Wiggins, R.D., & Netuveli, G. (2009). Examining resilience of quality of life in the face of health-related and psychosocial adversity at older ages: What is "right" about the way we age? The Gerontologist, 50(1), 36–47. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp067

- Hildon, Z., Smith, G., Netuveli, G., & Blane, D. (2008). Understanding adversity and resilience at older ages. Sociology of Health & Illness, 30(5), 726–740. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01087.x

- Hill, K., Kellard, K., Middleton, S., Cox, L., & Pound, E. (2007). Understanding resources in later life: Views and experiences of older people. York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- Hochhalter, A.K., Smith, M.L., & Ory, M.G. (2011). Successful aging and resilience: Applications for public health and health care. In B.G. Resnick, L.P. Gwyther, & K.A. Roberto (Eds.), Resilience in aging: Concepts, research, and outcomes (pp. 15–29). New York, NY: Springer.

- Hoge, E.A., Austin, E.D., & Pollack, M.H. (2007). Resilience: Research evidence and conceptual considerations for posttraumatic stress disorder. Depression and Anxiety, 24, 139–152.

- Infurna, F.J., Gerstorf, D., Robertson, S., Berg, S., & Zarit, S.H. (2010). The nature and cross-domain correlates of subjective age in the oldest old: Evidence from the OCTO study. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 470–476. doi:10.1037/a0017979

- Ip, S.P.S., Leung, Y.F., & Mak, W.P. (2000). Depression in institutionalised older people with impaired vision. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15, 1120–1124.

- Jennings, P.A., Aldwin, C.M., Levenson, M.R., Spiro, A., III, & Mroczek, D.K. (2006). Combat exposure, perceived benefits of military service, and wisdom in later life: Findings from the normative aging study. Research on Aging, 28(1), 115–134. doi:10.1177/0164027505281549

- Jopp, D., & Rott, C. (2006). Adaptation in very old age: Exploring the role of resources, beliefs, and attitudes for centenarians' happiness. Psychology and Aging, 21(2), 266–280. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.266

- Jopp, D., Rott, C., & Oswald, F. (2008). Valuation of life in old and very old age: The role of sociodemographic, social, and health resources for positive adaptation. The Gerontologist, 48(5), 646–658.

- Kaplan, H.B. (2002). Toward an understanding of resilience: A critical review of definitions and models. In M.D. Glantz & J.L. Johnson (Eds.), Resilience and development: Positive life adaptations. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic

- Kinsella, K., & Phillips, D.R. (2005). Global aging: The challenge of success population bulletin (Vol. 60). Washington, DC: Population Reference Bureau.

- Kotter-Gruhn, D., Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn, A., Gerstorf, D., & Smith, J. (2009). Self-perceptions of aging predict mortality and change with approaching death: 16-year longitudinal results from the Berlin Aging Study. Psychology and Aging, 24(3), 654–667. doi:10.1037/a0016510

- Kumpfer, K.L. (1999). Factors and processes contributing to resilience the resilience framework. In M.D. Glantz (Ed.), Resilience and development: Positive life adaptations (pp. 194). Hingham, MA: Kluwer Academic.

- Kunzmann, U., Little, T.D., & Smith, J. (2000). Is age-related stability of subjective well-being a paradox? Cross-sectional and longitudinal evidence from the Berlin Aging Study. Psychology and Aging, 15(3), 511–526. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.15.3.511

- Lachman, M.E., Rosnick, C.B., & Rocke, C. (2009). The rise and fall of control beliefs and life satisfaction in adulthood: Trajectories of stability and change over ten years. In H.B. Bosworth & C. Hertzog (Eds.), Aging and cognition: Research methodologies and empirical advances (pp. 143–160). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association

- Lamond, A.J., Depp, C.A., Allison, M., Langer, R., Reichstadt, J., Moore, D.J., … Jeste, D.V. (2009). Measurement and predictors of resilience among community-dwelling older women. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(2), 148–154. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.007

- Lawton, M., Kleban, M.H., Rajagopal, D., & Dean, J. (1992). Dimension of affective experience in three age groups. Psychology and Aging, 7, 171–184.

- Lawton, M.P., & Nahemow, L. (1973). Ecology and the aging process. In C. Eisdorfer & M.P. Lawton (Eds.), The psychology of adult development and aging (pp. 619–674). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association

- Liang, K. (2014). The cross-domain correlates of subjective age in Chinese oldest-old. Aging & Mental Health, 18(2), 217–224. doi:10.1080/13607863.2013.823377

- Luthar, S.S. (1993). Annotation: Methodological and conceptual issues in research on childhood resilience. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 34(4), 441–453.

- Luthar, S.S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00164

- Masten, A.S. (2001). Ordinary magic: Resilience processes in development. American Psychologist, 56(3), 227–238.

- Moore, A.J., & Stratton, D.C. (2002). Resilient widowers: Older men speak for themselves. New York, NY: Springer.

- Nakashima, M., & Canda, E.R. (2005). Positive dying and resiliency in later life: A qualitative study. Journal of Aging Studies, 19(1), 109–125. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2004.02.002

- Netuveli, G., Wiggins, R.D., Montgomery, S.M., Hildon, Z., & Blane, D. (2008). Mental health and resilience at older ages: Bouncing back after adversity in the British Household Panel Survey. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 62, 987–991. doi:10.1136/jech.2007.069138

- Nygren, B. (2006). Inner strength among the oldest old: A good aging (Medical dissertations). Umeå University, Sweden.

- O'Rourke, N. (2004). Psychological resilience and the well-being of widowed women. Ageing International, 29(3), 267–280.

- Ong, A.D., Bergeman, C., Bisconti, T.L., & Wallace, K.A. (2006). Psychological resilience, positive emotions, and successful adaptation to stress in later life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(4), 730–749. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.91.4.730

- Ong, A.D., Bergeman, C., & Boker, S.M. (2009). Resilience comes of age: Defining features in later adulthood. Journal of Personality, 77(6), 1777–1804. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00600.x

- Ostir, G.V., Carlson, J.E., Black, S.A., Rudkin, L., Goodwin, J.S., & Markides, K.S. (1999). Disability in older adults 1: Prevalence, causes, and consequences. Behavioural Medicine, 24(4), 147–156.

- Ott, C.H., Lueger, R.J., Kelber, S.T., & Prigerson, H.G. (2007). Spousal bereavement in older adults: Common, resilient, and chronic grief with defining characteristics. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 195(4), 332–341.

- Pincas, A. (2014). Lifelong learning – a brief sketch. Retrieved from http://lifelonglearningoverview.weebly.com/lifelong-learning.html

- Richardson, G.E. (2002). The metatheory of resilience and resiliency. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(3), 307–321.

- Rutter, M. (1979). Protective factors in children's responses to stress and disadvantage. In M.W. Kent & J.E. Rolf (Eds.), Primary prevention in psychopathology: Social competence in children ( Vol. 8, pp. 49–74). Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

- Satariano, W. (2006). Epidemiology of aging: An ecological approach. Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Scheetz, L.T., Martin, P., & Poon, L.W. (2012). Do centenarians have higher levels of depression? Findings from the Georgia Centenarian Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60, 238–242. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03828.x

- Schindler, I., Staudinger, U.M., & Nesselroade, J.R. (2006). Development and structural dynamics of personal life investment in old age. Psychology and Aging, 21(4), 737–753. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.21.4.737

- Schröder-Butterfill, E., & Marianti, R. (2006). A framework for understanding oldage vulnerabilities. Ageing and Society, 26, 9–35. doi:10.1017/S0144686×05004423

- Shen, K., & Zeng, Y. (2010). The association between resilience and survival among Chinese elderly. Demographic Research, 23(5), 105–116.

- Smith, J. (2000). The fourth age: A period of psychological mortality?. Berlin: Max Planck Forum.

- Smith, J., & Baltes, P.B. (1997). Profiles of psychological functioning in the old and oldest old. Psychology and Aging, 12(3), 458–472. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.12.3.458

- Stanford, B.H. (2006). Through wise eyes: Thriving elder women's perspectives on thriving in elder adulthood. Educational Gerontology, 32, 881–905. doi:10.1080/03601270600846709

- Staudinger, U.M., & Fleeson, W. (1996). Self and personality in old and very old age: A sample case of resilience? Development and Psychopathology, 8, 867–885.

- Staudinger, U.M., Freund, A.M., Linden, M., & Maas, I. (1999). Self, personality, and life regulation: Facets of psychological resilience in old age. In P.B. Baltes & K.U. Mayer (Eds.), The Berlin aging study: Aging from 70 to 100 (pp. 302–328). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stewart, D.E., & Yuen, T. (2011). A systematic review of resilience in the physically ill. Psychosomatics, 52(3), 199–209.

- Stuckey, J. (2006). Not ‘success’ but ‘meaning’: Dementia and meaningful aging. Paper presented at the 59th annual scientific meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, Dallas, TX.

- Vaillant, G.E. (2007). Aging well. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(3), 181–183. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e31803190e0

- Verbrugge, L.M., & Jette, A.M. (1994). The disablement process. Social Science and Medicine, 38(1), 1–14.

- von Faber, M., & van der Geest, S. (2010). Losing and gaining: About growing old “successfully” in the Netherlands. In J.E. Graham & P.H. Stephenson (Eds.), Contesting aging and loss (pp. 27–46). Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Wagnild, G.M., & Young, H.M. (1993). Development and psychometric evaluation of the resilience scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1(2), 165–178.

- Werner, E.E., & Smith, R.S. (1982). Vulnerable but invincible: A study of resilient children. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Westphal, M., & Bonanno, G.A. (2007). Posttraumatic growth and resilience to trauma: Different sides of the same coin or different coins? Applied Psychology: An International Review, 56(3), 417–427.

- Wild, K., Wiles, J.L., & Allen, R.E.S. (2013). Resilience: Thoughts on the value of the concept for critical gerontology. Ageing and Society, 33, 137–158. doi:10.1017/S0144686X11001073

- Wiles, J.L., Wild, K., Kerse, N., & Allen, R.E.S. (2012). Resilience from the point of view of older people: ‘There's still life beyond a funny knee’. Social Science & Medicine, 74, 416–424. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.11.005

- Windle, G. (2011). What is resilience? A review and concept analysis. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 21(2), 152–169. doi:10.1017/S0959259810000420

- Windle, G., Markland, D.A., & Woods, R.T. (2008). Examination of a theoretical model of psychological resilience in older age. Aging & Mental Health, 12(3), 285–292. doi:10.1080/13607860802120763

- Windle, G., Woods, R.T., & Markland, D.A. (2010). Living with ill-health in older age: The role of a resilient personality. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(6), 763–777. doi:10.1007/s10902-009-9172-3

- Wright St-Clair, V., Kerse, N.M., & Smythe, E. (2011). Doing everyday occupations both conceals and reveals the phenomenon of being aged. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58, 88–94. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1630.2010.00885.x

- Wu, Z., Schimmele, C.M., & Chappell, N.L. (2012). Aging and late-life depression. Journal of Aging and Health, 24(1), 3–28. doi:10.1177/0898264311422599

- Zeng, Y., & Shen, K. (2010). Resilience significantly contributes to exceptional longevity. Current Gerontology and Geriatrics Research, 2010, 1–9. doi:10.1155/2010/525693