ABSTRACT

Objectives: The implementation of new health services is a complex process. This study investigated the first phase of the adaptive implementation of the Dutch Meeting Centres Support Programme (MCSP) for people with dementia and their carers in three European countries (Italy, Poland, the UK) within the JPND-MEETINGDEM project. Anticipated and experienced factors influencing the implementation, and the efficacy of the implementation process, were investigated. Findings were compared with previous research in the Netherlands.

Method: A qualitative multiple case study design was applied. Checklist on anticipated facilitators and barriers to the implementation and semi-structured interview were completed by stakeholders, respectively at the end and at the beginning of the preparation phase.

Results: Overall, few differences between countries were founded. Facilitators for all countries were: added value of MCSP matching needs of the target group, evidence of effectiveness of MCSP, enthusiasm of stakeholders. General barriers were: competition with existing care and welfare organizations and scarce funding. Some countries experienced improved collaborations, others had difficulties finding a socially integrated location for MCSP. The step-by-step implementation method proved efficacious.

Conclusion: These insights into factors influencing the implementation of MCSP in three European countries and the efficacy of the step-by-step preparation may aid further implementation of MCSP in Europe.

Introduction

Current estimates suggest that 900 million people worldwide are aged over 60 (Alzheimer's Disease International, Citation2015). This ageing of the population is often attributed to improvements in public health, nutrition and more effective health care interventions (Huber et al., Citation2011). The leading causes of disease and death have shifted, with an increasing number of people experiencing non-communicable and degenerative diseases (World Health Organization, Citation2011). For example, the number of people living with a dementia is predicted to grow from 46.8 million in 2015 to 131.5 million by 2050 (Alzheimer's Disease International, Citation2015). This ‘epidemiologic transition’ has driven experts to reconsider the definition of health. An example is the new concept of health as suggested by Huber et al. (Citation2011) who have conceptualized health as the ability to adapt and to self-manage.

A programme for people with dementia that resonates with the new conceptualization of health is the Meeting Centre Support Programme (MCSP). It was developed in the Netherlands in the 1990s, based on the Adaptation–Coping Model (Dröes, Citation1991; Dröes, Meiland, Schmitz, & van Tilburg, Citation2011). The MSCP provides a person-centred, comprehensive and integrated programme, offering support to people with dementia and their family carers, providing information and practical, social and emotional support. This enables people with dementia and their families to cope with the condition. A key element of the MCSP is that it is offered in a local resource centre to promote social participation and integration in the community. Dutch multi-centre research demonstrated that when compared to regular psychogeriatric day care in nursing homes, the MCSP had a positive effect on mood, behaviour, self-esteem and delay of institutionalization (Dröes et al., Citation2000; Dröes, Breebaart, Meiland, Van Tilburg, & Mellenbergh, Citation2004a; Dröes, Meiland, Schmitz, & van Tilburg, Citation2004b; Meiland, Schmitz, & Van Tilburg, Citation2006). In addition, it improved the feelings of competence (Dröes et al., Citation2004a) and reduced feelings of burden, and psychological and psychosomatic complaints of family caregivers (Dröes, Meiland, Schmitz, & Van Tilburg, Citation2006).

Despite the proven effectiveness of an intervention, successful implementation will be determined by the specific context. Although many models have attempted to describe which factors influence successful implementation of an intervention, there is no evidence to suggest that one model is preferable (Grol, Citation1997). Research has demonstrated that obstacles to implementation can be of different types: the nature of the intervention, the skills of the professionals delivering it, and the social, organizational, economic and political contexts (Grol & Wensing, Citation2004). Thus, while ‘lessons learned’ about facilitators and barriers to implementation in different contexts and cultures can be helpful, facilitating and impeding factors need to be reassessed in different contexts and the implementation adapted accordingly.

Within the framework of a European collaborative implementation study the MEETINGDEM project (funded by the EU Joint Programme – Neurodegenerative Disease Research – JPND), the MCSP was implemented in three additional European countries: Italy, Poland and the UK. The aim of MEETINGDEM is to understand if and how MCSP can be implemented in other European countries and how it can be adapted to their needs and culture as well as to different welfare and health care organizations, and to evaluate whether the effects of MCSP in these new countries are comparable to those evidenced in the Netherlands.

This paper reports on the evaluation of the first phase of the adaptive implementation process in Italy, Poland and the UK. It also tries to shine a light on the relevance of adaptive implementation of MCSP by investigating in these three countries to what extent and in what areas anticipated facilitators and barriers of implementation beforehand match actual experiences during the implementation process. Discrepancies between anticipated and experienced facilitators and barriers would emphasize the need for adaptive implementation of MCSP in these and other countries in Europe. More specifically, the research in this preparation phase addressed four sub-questions:

What facilitating and impeding factors did MCSP stakeholders anticipate before the implementation of MCSP in the different countries?

What facilitators and barriers were actually experienced during the first phase of adaptive implementation and did those differ from what was expected beforehand?

Are the facilitators and barriers observed in Italy, Poland and the United Kingdom comparable to those experienced in the Netherlands?

Is the implementation methodology, as developed and successfully used in the Netherlands, feasible and effective in other countries? Or were adaptations needed in the implementation methodology (e.g. step-by-step procedure, tools, planning) in the new context of the three countries, and if so, what adaptations were necessary?

Methods

Study design

A qualitative multiple case study design was used to compare data on (anticipated and experienced) facilitators and barriers to the implementation of MCSP during the preparation phase in European countries and to evaluate the implementation methodology.

Implementation methodology

In all countries, a step-by-step approach was adopted to promote an effective implementation of the MCSP. The first step consisted of preparing a database of possible organizations interested in setting up a Meeting Centre. An Information Meeting with interested organizations took place in each country. The aim was threefold: to inform stakeholders in the locality about the project, to recruit participants willing to be involved in the Initiative Group that would prepare a plan for the adaptive implementation in their own country and to interest stakeholders in becoming potential future referrers of clients to the Meeting Centre. This meeting was carried out with the same agenda for all three countries, based on the experiences in the Netherlands. In the first Initiative Group meeting stakeholders who expressed willingness in the implementation of MCSP were asked to complete the checklist in order to raise awareness of potential facilitators and barriers they might encounter during the implementation. This was then discussed in subgroups. A second Initiative Group meeting was held to further discuss the facilitators and barriers identified with a view to find possible solutions. Working groups that would elaborate on the various aspects of the implementation were formed (i.e. the target group that would use the centre, the support programme for people with dementia and their carers, location-requirements, requirements for and training of personnel and volunteers, financing of the Meeting Centre, a protocol for collaboration and a communication plan). The results achieved in the working groups were shared with the other members during the Initiative Group meeting. When all working groups had finalized their activities, the date for opening of the Meeting Centre was set (see for details on the implementation process in Italy, Poland and the UK).

Table 1. Description of the implementation process in the three countries.

Setting and sample

All European countries within the INTERDEM group (a pan-European network of researchers on early detection and psychosocial interventions in dementia, see www.interdem.org) were invited to apply for participation. The three countries included in this study (Italy, Poland and the UK) were the countries that expressed their willingness to participate in the MEETINGDEM project and who were also involved in the EU JPND research program. Differences between care infrastructures in the different countries were taken into account in the process of adaptive implementation. In all countries Initiative Groups were set up that consisted of representatives of a mix of welfare and care organizations, Alzheimer organizations, volunteer organizations, local/regional government and the Research Institute involved in the MEETINGDEM project. In the UK, a charity organization and a forum for older people also participated. Next, these Initiative Groups worked in themed sub-groups to prepare different aspects of the implementation (e.g. inclusion criteria for the target group, the support programme, the location, training of personnel, collaboration with other organizations, financing). In each country, and for every meeting centre, one of the organizations was asked to appoint the personnel of the meeting centre. In Italy, in Milan, this was the Research Institute involved in the MEETINGDEM project the Municipality and a private foundation, in Poland this was the university and in the UK this was the Alzheimer organization.

Stakeholders for the data collection on anticipated facilitators and barriers (before the start of the preparation phase) were recruited from members of the Initiative Groups in Italy (19 stakeholders), Poland (23 stakeholders) and the UK (34 stakeholders), in the period 2014–2015. At the end of the preparation phase, semi-structured interviews were conducted with ‘purposively selected’ (Barbour, Citation1999) Meeting Centre stakeholders in Italy, Poland and the UK. These data were compared with data from a multi-centre study on successful implementation of MCSP in the Netherlands in 2000–2003 (Dröes et al., Citation2003). The inclusion criteria were: representatives from different organizations (care and welfare) involvement in the implementation, stakeholders with professional and financial expertise and stakeholders at the local governmental level (municipality) and at the regional/national level (e.g. Alzheimer Association and Societies). These are described in

Table 2. Stakeholders interviewed in each country.

In Italy, this study was conducted in Milan (Lombardia region), in Poland in the city of Wroclaw region and in the UK in Droitwich Spa (Worcestershire). In Italy two Meeting Centres opened in May 2015. Meeting Centres opened in Poland and the UK in September 2015.

In the Netherlands the earlier implementation study was performed in 11 Meeting Centres located in five regions. In this study, the same step-by-step procedure was used as in the MEETINGDEM project.

Data collection materials and procedure

To collect the data a checklist of anticipated facilitators and barriers for implementation was used before the start of the preparation phase and semi-structured interviews on experienced facilitators and barriers were conducted at the end of this phase. The checklist was based on the theoretical framework of Meiland, Dröes, De Lange, and Vernooij-Dassen (Citation2004) and the findings on facilitating and impeding factors of the implementation of MCSP in the Netherlands (Meiland, Dröes, de Lange, & Vernooij-Dassen, Citation2005). It consisted of a list with potential facilitators and barriers in each category of the model, and room for adding new potential facilitators and barriers which were not listed in the survey.

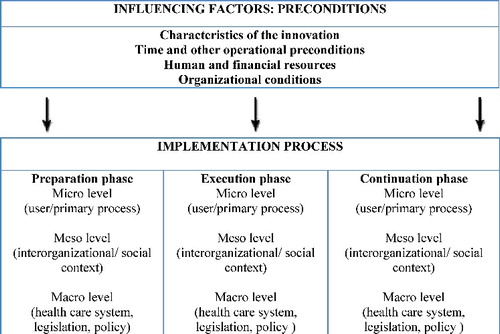

In the Dutch multi-centre implementation study semi-structured interviews were conducted, that were also based on the theoretical framework of Meiland et al. (Citation2004). This framework () identifies three phases in the implementation process: Preparation, Execution and Continuation. Factors facilitating or impeding the implementation process can be found in (1) the (pre)conditions existing at the start of the implementation process, which can influence the implementation in all phases of the process, i.e. Characteristics of the innovation, Time and other operational preconditions, Human and financial resources, and Organizational conditions; (2) during the different phases of implementation at the user/primary process (micro) level, the (inter)organizational/social context (meso) level, and the level of the health care system, legislation and policy (macro) level.

Figure 1. Theoretical framework of factors influencing adaptive implementation (Meiland et al., Citation2004)*. *In this paper the focus is on Influencing factors: preconditions and the preparation phase.

The semi-structured interview investigated the same topics as presented in the checklist, with the addition of new topics that were mentioned during the administration of the checklist. A common interview schedule was used for all countries. Depending on the expertise of the various stakeholders and their particular involvement in the implementation process, relevant questions were selected from this common interview schedule.

Furthermore, minutes were collected of all meetings of the Initiative Group in each country.

In Italy, Poland and the UK data were collected at two stages: (1) during the first meeting of the Initiative Group members were asked to fill in the checklist about expected facilitators and barriers in their community and to rank items according to whether they could be considered as major, intermediate or minor in terms of the expected impact on the implementation process. This was first done on an individual level to stimulate everyone to think about potential facilitators and barriers, then discussed in subgroups and finally in the plenary group, in order to reach an agreement on the emerging facilitators and barriers and their order of priority. (2) At the end of the preparation phase the semi-structured interviews were performed with stakeholders in these three countries.

In the Netherlands the semi-structured interviews on the preparation phase were conducted retrospectively once the MCSP was operational.

All interviews in Italy, Poland, the UK and the Netherlands were done in the national language either by a trainee (Italy) or by researchers from the project team (in Poland, the UK and the Netherlands).

In Italy the mean length of the interviews was 55 minutes, in Poland 23, in the UK 38 and in the Netherlands 80 minutes. All approached stakeholders agreed to participate, except in Poland, where one of the stakeholders declined because of the audiotape recording.

All countries had ethical approval for the study from the relevant ethical committees.

Analysis

A descriptive analysis was used to analyse the data collected with the checklist and the results were summarized in tables.

All semi-structured interviews with stakeholders were audio-taped and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were analysed qualitatively using the methodology of direct content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005) using Excel and Mindmap in Italy, and NVivo in the other countries. In each country, transcripts and minutes of the Initiative Groups meetings were coded by two independent researchers. The emphasis was on deductive coding: the framework of Meiland et al. (Citation2004) and the facilitators and barriers found in the Dutch implementation project guided the development of the coding scheme that was used to analyse the interviews with stakeholders. Incidentally, new codes were added if themes appeared relevant that were not yet included in the checklist, such as in Italy where a code was added on the role of family members of people with dementia in the development of the meeting centre. Where there was disagreement about the assigned codes, the assessors discussed these until consensus was reached.

In each country all coded text fragments were ordered by code, and subsequently divided into the categories of influencing factors as distinguished in the theoretical framework of Meiland et al. (Citation2004), and according to the level of importance assigned by stakeholders (major, intermediate, minor). The themes were checked for consistency with the original data. Next, the themes were organized and described for each country, and compared with each other. Finally, the main differences and similarities between the four countries in factors influencing the preconditions and the preparation phase were summarized.

Results

Below, the results on anticipated (research question 1) and experienced (research question 2) facilitators and barriers encountered in preparing the implementation of the meeting centres in Italy, Poland and the UK are described following the theoretical model of adaptive implementation (see ); the comparison with facilitators and barriers found in the Netherlands when implementing the meeting centres (research question 3) is also reported. Finally, the results for research question 4 (implementation methodology) are described.

Facilitators and barriers regarding preconditions

provides an overview of facilitators and barriers in setting up a MCSP in different countries. Below they will be explained.

Table 3. Anticipated and experienced facilitators (F) and barriers (B) regarding the preconditions of implementation of MCSP.

Characteristics of MCSP

All three countries anticipated that MCSP would have added value because it provides support for both the person with dementia and the caregiver. Polish stakeholders pointed out that in their country there is nowhere for caregivers of people with dementia to get practical and emotional support. However, concerns emerged regarding the limited number of people with dementia that would be able to attend one MCSP (one centre was considered not enough) and the stigma associated with dementia that causes communities to be resistant to socialising with people with dementia. During the preparation phase all three countries could see the need for this innovative programme. Although in the English context stakeholders initially struggled ‘to understand what it [the MCSP] is different to what's currently in place’, their experience was that the MCSP was ‘going to offer a lot more than currently available and pull things together in a really nice way for the community’. This matches the Dutch findings where stakeholders considered the combined support offered to persons with dementia and caregivers, as opposed to the previously fragmented support offer, as a strength of the programme.

In the Netherlands, having examples of MCSP's available appeared beneficial for setting up new centres. This was recognized by the other countries, who believed that having the Dutch example available was a facilitator, while the lack of examples in their own country was experienced as a barrier. In the preparation phase some Italian stakeholders felt that the European project proposal and the existing Dutch guide to set up a MCSP were helpful, but in the beginning they considered it difficult to imagine the project. In Poland, trying to follow the ‘perfect Dutch model’ was a barrier for successful adaptation of MCSP in their country-specific context. However, the practical and theoretical support based on the Dutch experiences facilitated the implementation. A stakeholder from the UK also highlighted that having an existing model ‘gives people confidence that it is a model that can be delivered’.

Time and other preconditions

Stakeholders in Italy and the UK expected that the time schedule of one year would be sufficient for establishing a Meeting Centre. However, in Poland there were concerns about the timescale. English stakeholders highlighted that a barrier of having such a long time schedule could be that people might lose their enthusiasm. Despite their expectation, the reality in Italy was that for practical reasons (funding opportunities) they had to speed up the implementation process. English stakeholders felt that the long preparation phase was indeed needed, as expressed by a stakeholder: ‘I certainly wouldn't have wanted less time.’ The Polish stakeholders could meet deadlines within the time planned, although some stakeholders considered the workload too high. Also in the Netherlands having enough preparation time proved necessary for successful implementation. A condition that sped up the implementation was integrating MCSP in an existing facility (general community centre or day care centre). This was experienced as a facilitator in Italy and in the Netherlands.

Human resources

All countries expected and experienced that good skills of the project manager and enthusiasm of involved parties facilitated the implementation. Moreover, stakeholders of the three countries emphasized the good management skills of their own project manager. The enthusiasm of the project manager was also a facilitating factor in preparing the Dutch Meeting Centres.

Having a transparent project plan was considered beneficial by all countries, before and after the preparation phase, as it enabled stakeholders to better understand the project concept. An English stakeholder said: ‘There was a very clear sense of what we were doing, what we were here to do, what role the different group members would take.’ Polish and English stakeholders claimed that part of this transparency included good communications, as an English stakeholder said: ‘clear information [was given] in advance, [there was] a clear sense of when the meetings were, and what was going to be covered’.

Organizational conditions

According to the Italian stakeholders, contact with the existing network in dementia care was expected to be helpful but not essential. English stakeholders foresaw an existing network as facilitating the implementation as long as the organizations of the network did not feel threatened by the Meeting Centre. Polish stakeholders expected the existing network to both facilitate and impede the implementation because it is developing but not yet functioning well. During the preparation phase in Italy, stakeholders experienced the collaboration with the existing network not only as useful, but also necessary, contrary to what was expected. In the UK the Meeting Centres project enriched the existing network, creating links between the Alzheimer's Society, Age UK, memory clinics, local organizations and voluntary groups. This helped to embed the Meeting Centre in the community. All countries expected competition with other services to be a potential barrier. During the preparation phase difficult collaborations between organizations were experienced. Polish stakeholders expected that the attuned value of MCSP with the policy of Wroclaw to improve the quality of life of elderly people through social reactivation and improving health care and social assistance would be a facilitator. During the preparation phase this appeared partly true because of the difficult collaboration between care and welfare organizations. However, for the implementation of the first Meeting Centre this barrier was overcome.

The collaboration between organizations is discussed in more detail under the subheading meso level.

The existing network and organizational competition also matched the findings in the Netherlands.

Facilitators and barriers in the preparation phase

provides an overview of expected and experienced facilitators and barriers in the preparation phase.

Table 4. Anticipated and experienced facilitators (F) and barriers (B) during the preparation of the implementation of MCSP.

Micro level

The enthusiasm of people involved in the implementation was expected and experienced as a facilitator in all countries. As an Italian stakeholder claimed: ‘well, being there all together for a common purpose, that of being able to improve the quality of life of the ill person and his family, […] everybody was there for one single purpose’. Stakeholders of the UK highlighted that the Initiative Group was a good way of bringing people together.

Human resources were expected to be an important and facilitating factor by all countries if skilled personnel and volunteer were to be appointed appropriately. Polish stakeholders thought that it would be difficult to find enough volunteers, which was expected to impede the implementation. Among the English stakeholders barriers concerning getting experienced personnel and enough volunteers were anticipated. Italian stakeholders expected the mix of personnel and volunteers to facilitate the implementation of MCSP as the interdisciplinarity would enrich the team, provided that extensive training would be given to them. During the preparation phase, English stakeholders underestimated the time needed to recruit and train the staff. In Italy, stakeholders did not experience any difficulties in recruiting suitable personnel and volunteers.

In all countries, all stakeholders expected that location would heavily influence the implementation. In the UK, it was expected to be beneficial if the Meeting Centre would be located near the centre, otherwise problems with transport would occur. In Poland, finding a suitable location was anticipated as a barrier because of funding issues. During the preparation phase Italian stakeholders experienced finding a good location a major barrier, because of limited choice of funded locations, and because other users of one of the chosen centres resisted the idea of sharing their space with people with dementia. In Poland, finding a good location was facilitated by cooperation with Wroclaw Municipality and welfare organizations. In the UK, it was experienced as a barrier, and compromises had to be made. One stakeholder explained: ‘it was a case of what's available for the time we want, in the area we want it, and it couldn't tick all the boxes’. In the Netherlands, it was experienced as a facilitator when a suitable location was soon found. Meeting Centres put a heavy demand on a location because of the opening hours (three days a week) and the space needed for the activities for people with dementia and for the carers, while most existing public locations, such as community centres, are also occupied by other activities and groups for several days a week.

Meso level

Constructive collaboration with health care and welfare was expected to be a major facilitator in the preparation of the implementation in all three countries. Italian stakeholders expected that collaboration with the organizations involved in dementia care would be important, while the collaboration with other organizations (e.g. local health agency) would be merely energy and time consuming. In the UK, at the start of the preparation phase, the collaboration between care and welfare organizations was seen as a major barrier as well as in Poland where the procedures between the health care system and the social support system are structured in a rigid manner. However, contrary to expectations, the Italian stakeholders felt that the collaboration with other organizations facilitated the implementation. In line with expectations, a Polish stakeholder stated that ‘a lack of collaboration between the medical and social sector in Poland, in practice’, had a negative impact on the collaboration on a local and national level. Stakeholders in the UK experienced good collaboration with both care and welfare organizations.

Finding funders for the Meeting Centres was expected to be a major barrier in all countries.

Italian stakeholders expected difficulties in obtaining funding due to the financial structure and procedure. In Poland, difficulties were expected because the National Health System is predominantly medically focused and as a consequence the National Health Funds are inclined to finance only health care services and not psychosocial interventions. During the preparation phase two Italian organizations represented on the Initiative Group proposed to financially support the project. In Poland, difficulties were experienced in finding adequate funding for the MCSP. In the UK, having funding from the start of the preparation phase from the Alzheimer's Society was very beneficial. All countries obtained funding for the execution phase but not yet sustainable funding in the longer term.

Macro level

In Italy, health care system legislation was both expected and experienced as an impediment to the possibility of providing funding, as the care offered is not currently recognized as a health care treatment. On the other hand, obtaining funding from the welfare system was experienced as difficult because of its limited resources. Another barrier was the absence of a national plan for dementia. However, during the preparation phase the involvement in the Initiative Group of a person experienced in legislation and financing was beneficial. Also in Poland it was expected and experienced that legislation and regulations would impede the implementation because of the medical orientation of the national health care system, as well as different legislation for the health and social sectors. In the UK, an expert in law and regulation from the Initiative Group facilitated the process of identifying potential sources of funding.

Implementation methodology

The step-by-step procedure was seen as one of the fundamental facilitators to the implementation of MCSP by the Polish stakeholders. It was well structured, the tasks were defined clearly and sharing the results each month helped to keep everyone updated about progress. English stakeholders reported similar advantages. According to a stakeholder: ‘I think it was a really good way of organizing the project. The Initiative Group, the coming together and having updates through all of those working groups actually worked very well’.

Regarding the first step of the procedure, i.e. to make an inventory of potential facilitators and barriers for implementation, Poland and the United Kingdom did not make any adaptations. Among Italian stakeholders, concerns about the clarity and suitability of the checklist arose. Many stakeholders had difficulties thinking in advance about factors that could facilitate or impede the implementation of MCSP. A stakeholder said: ‘The first meetings were a bit difficult, because we had to do all the discussions of the checklist about barriers and facilitators. For us, at least, that was absolutely the most difficult thing’. They also had difficulties understanding some of the questions, e.g. if the MCSP was attuned to the local care and support offer. However, they found the working groups to be effective as they helped to focus on specific tasks and the groups were experienced as inspiring because of the mix of members with different backgrounds.

Discussion

This study evaluated the preparation process that preceded the adaptive implementation of the Dutch MCSP in three European countries: Italy, Poland and the UK. The aim was to gain insight into facilitators and barriers that were anticipated prior to the preparation phase and those that were actually experienced, and to compare the facilitators and barriers that were experienced in Italy, Poland and the UK with those in the Netherlands. Furthermore, this study investigated whether aspects of implementation needed to be adapted in the different countries and whether the Dutch step-by-step procedure was transferable.

The characteristics of the innovation facilitates the implementation process, as expected by all countries. This includes the added value, meeting the needs of the target group, scientific evidence demonstrating the effectiveness of the programme, the clear project plan, the enthusiasm of the people involved and the skilled management. However, all countries found that competition with other organizations, access to funding and existing law and regulations on health care and welfare impeded the implementation.

Not all anticipated facilitators and barriers were experienced during the preparation phase. In Italy the importance of existing health and care networks, the enthusiasm of the stakeholders in the Initiative Group and preparation of the location were underestimated beforehand. Obtaining funding turned out to be a facilitator in Italy. Although some English stakeholders had concerns about the rather long preparation phase (9–12 months), the time scheduled turned out to be realistic. The collaboration with organizations in the existing network proved to be beneficial. Contrary to the expectations of Polish stakeholders, finding a suitable location, thanks to collaboration with the Municipality of Wroclaw, facilitated the process. Although some Polish stakeholders were optimistic that the added value of the Meeting Centre would stimulate organizations to collaborate with the centres, competition turned out to be a major barrier for this. Polish and Italian stakeholders expected that the Dutch Model would be the best fit, but in practice the programme had to be adapted to the local context.

The following facilitating factors were similar in all three countries, as well as mirroring the earlier Dutch experience of implementing Meeting Centres (Meiland et al., Citation2005) are: the added value of the programme, meeting the needs of the target group and values of organizations, the enthusiasm of the stakeholders involved, the availability of scientific research, having a clear project plan and a motivated project manager. Common impeding factors were the competition, the limited availability of funding and the challenges of collaboration with other organizations. However, some factors seemed to depend on the specific context in the different countries. For example, the lack of a dementia care network impeded the implementation in Poland, whereas in the Netherlands this proved to be an important facilitator. Shortage of time in the preparation phase was only an issue for the Italian stakeholders, because circumstances related to funding forced them to shorten the preparation phase. In Poland and the UK, recruiting the appropriate personnel was experienced as difficult, while in Italy and in the Netherlands this was not an issue.

The implementation methodology followed a step-by-step procedure which consisted of first making an inventory of potential facilitators and barriers for implementation and, after that, the preparation of the implementation plan in thematic working groups. This appeared feasible and useful in the different countries. However, some adaptation might be needed where stakeholders have difficulties conceptualizing the implementation process in advance, as was the case in Italy.

In such cases it could be helpful to use tools that enable stakeholders to better comprehend the MCSP – such as videos and brochures on the MCSP and a practical guide on setting up an MCSP, but also to visit existing Meeting Centres within or outside their country. This might make it easier to discuss potential facilitators and barriers for setting up an MCSP.

Regarding funding, all the countries struggled to obtain financial support from welfare sources. A solution could be involving the health care systems of the different countries, as was successfully done in the Netherlands, in the financing of MCSP, as this programme showed several health benefits in the past both for the person with dementia – such as delay of institutionalization and less behavioural and mood problems – and the carer – such as less psychosomatic problems, burden and sense of competence (Dröes et al., Citation2000, Citation2004a, Citation2004b, Citation2006). In fact considering the new formulation of health in an ageing society (Huber et al, Citation2011) as the ability to adapt and self-manage, and the shift in treatment from a biological to a biopsychosocial perspective, the MSCP can be considered as part of the health care system, providing effective multidisciplinary and combined support to people with dementia and informal carers.

Previous implementation studies in dementia care showed comparable facilitating factors: importance of a constructive collaboration (Döpp et al., Citation2013), being attuned to the local service offer (Van Haeften-van Dijk Meiland, Van Mierlo, & Dröes, Citation2015), the importance of having an enthusiastic and skilled project leader, transparent project planning and clarity about the role of each person involved (Van Weert et al., Citation2004; Van Haeften-van Dijk et al., Citation2015). Difficulties in collaborating with other organizations due to the threat of competition were also found earlier (Van Haeften-van Dijk et al., Citation2015; Van Mierlo, Meiland, Van Hout, & Dröes, Citation2014). However, none of these studies considered facilitating and impeding factors within a European comparative perspective. Lau et al. (Citation2016) found comparable results in the primary care setting: appropriate law and legislation, skilled leadership, the availability of resources such as time, funding, staff, the benefit of the intervention, the fit between the intervention and the context facilitated the implementation process. This suggests that the results of our study may also be of relevance for other fields of health care.

The study reported in this paper had a number of strengths. It was conducted in three very different European countries; multiple data collection methods were used (checklist, interviews, documentary analysis of the minutes of the Initiative Group meetings); and the study was supported by scientific research and guided by a well-structured project plan and experts in the field of implementation research. However, the latter can also be seen as a weakness for generalizing the results, as these conditions will not always be available in daily practice. In addition, the content analyses were performed separately in each country and it was difficult to ensure that this was done in exactly the same way. To mitigate against this problem, a common coding list was used. Also, two independent coders were utilized to enhance reliability. As the implementation was evaluated in one locality per country, caution needs to be exercised in generalizing the results to implementation of Meeting Centres to other regions, especially when there are strong regional differences (e.g. regulations and care culture).

The relevance of this study is that it gives a better understanding of implementation of MCSP in the local context by comparing anticipated facilitators and barriers with those that were experienced in practice. To our knowledge, such comparison has not been researched previously.

It also adds to the knowledge on adaptive implementation of the MCSP obtained from previous research in the Netherlands. The centres set up in Italy, Poland and the UK are pilot-centres, intended as examples for these countries. Moreover, they showed that successful implementation of MCSP in different European countries is feasible, despite differences in these countries regarding, for example, existing services for psychosocial support in dementia and more specifically for dementia caregivers, involvement and responsibilities of different type of organizations in community dementia care, and funding opportunities. At the end of the MEETINGDEM project the findings on the adaptive implementation of MCSP in Italy, Poland and the UK will be used to develop country-specific implementation guides to support further dissemination of Meeting Centres in these and other European countries. Such a broad dissemination of the MCSP may contribute to more adequate and timely support for community-dwelling people with dementia and their caregivers, thereby promoting their health and well-being.

Acknowledgments

This is an EU Joint Programme – Neurodegenerative Disease Research (JPND) project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alzheimer's Disease International. (2015). World Alzheimer Report 2015. The global impact of dementia. An Analysis of Prevalence, Incidence, Cost and Trends. Retrieved from https://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2015.pdf

- Barbour, R.S. (1999). The case for combining qualitative and quantitative approaches in health services research. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, 4(1), 39–43. doi:10.1177/135581969900400110

- Döpp, C.M., Graff, M.J., Rikkert, M.G.M.O., Nijhuis van der Sanden, M.W.G., & Vernooij-Dassen, M.J.F.J. (2013). Determinants for the effectiveness of implementing an occupational therapy intervention in routine dementia care. Implement Science, 8(1), 131. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-8-131

- Dröes, R.M. (1991). Psychosocial care for elderly people with dementia. Amsterdam: Faculty of Medecine of Vrije University. ( in Dutch).

- Dröes, R.M., Breebaart, E., Ettema, T.P., van Tilburg, W., & Mellenbergh, G.J. (2000). Effect of integrated family support versus day care only on behavior and mood of patients with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 12(1), 99–115. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1041610200006232

- Dröes, R.M., Breebaart, E., Meiland, F.J.M., Van Tilburg, W., & Mellenbergh, G.J. (2004a). Effect of Meeting Centres Support Program on feelings of competence of family carers and delay of institutionalization of people with dementia. Aging & mental health, 8(3), 201–211. doi:10.1080/13607860410001669732

- Dröes, R.M., Meiland, F.J., de Lange, J., Vernooij-Dassen, M.J., & van Tilburg, W. (2003). The meeting centres support programme: An effective way of supporting people with dementia who live at home and their carers. Dementia, 2(3), 426–433.

- Dröes, R.M., Meiland, F., Schmitz, M., & van Tilburg, W. (2004b). Effect of combined support for people with dementia and carers versus regular day care on behaviour and mood of persons with dementia: results from a multi‐centre implementation study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(7), 673–684. doi:10.1002/gps.1142

- Dröes, R.M., Meiland, F.J.M., Schmitz, M.J., & Van Tilburg, W. (2006). Effect of the meeting centres support program on informal carers of people with dementia: Results from a multi-centre study. Aging and Mental Health, 10(2), 112–124. doi:10.1080/13607860500310682

- Dröes, R.M., Meiland, F.J., Schmitz, M.J., & van Tilburg, W. (2011). How do people with dementia and their carers evaluate the meeting centers support programme? Non-Pharmacological Therapies in Dementia, 2(1), 19.

- Grol, R. (1997). Beliefs and evidence in changing clinical practice. Personal Paper, 315(7105), 418–421.

- Grol, R., & Wensing, M. (2004). What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Medical Journal of Australia, 180(Suppl. 6), S57.

- Hsieh, H.F., & Shannon, S.E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Huber, M., Knottnerus, J.A., Green, L., van der Horst, H., Jadad, A.R., Kromhout, D., … Schnabel, P. (2011). How should we define health? BMJ, 343, 1–3. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d4163

- Lau R., Stevenson, F., Ong, B.N., Dziedzic, K., Treweek, S., Eldridge, S., … Peacock, R. (2016). Achieving change in primary care—causes of the evidence to practice gap: Systematic reviews of reviews. Implementation Science, 11(1), 1. doi:10.1186/s13012-016-0396-4

- Meiland, F.J.M., Dröes, R.M., De Lange, J., & Vernooij-Dassen, M.J.F.J. (2004). Development of a theoretical model for tracing facilitators and barriers in adaptive implementation of innovative practices in dementia care. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 38, 279–290. doi:10.1016/j.archger.2004.04.038

- Meiland, F.J., Dröes, R.M., de Lange, J., & Vernooij-Dassen, M.J. (2005). Facilitators and barriers in the implementation of the meeting centres model for people with dementia and their carers. Health policy, 71(2), 243–253. doi:10.1016/j.healthpol.2004.08.011

- Van Haeften-van Dijk, A.M., Meiland, F.J.M., Van Mierlo, L.D., & Dröes, R.M. (2015). Transforming nursing home-based day care for people with dementia into socially integrated community day care: Process analysis of the transition of six day care centres. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(8), 1310–1322. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.04.009

- Van Mierlo, L.D., Meiland, F.J., Van Hout, H.P., & Dröes, R.M. (2014). Towards personalized integrated dementia care: A qualitative study into the implementation of different models of case management. BMC Geriatrics, 14(1), 1. doi:10.1186/1471-2318-14-84

- Van Weert, J.C., Kerkstra, A., van Dulmen, A.M., Bensing, J.M., Peter, J.G., & Ribbe, M.W. (2004). The implementation of snoezelen in psychogeriatric care: An evaluation through the eyes of caregivers. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 41(4), 397–409. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2003.10.011

- World Health Organization. (2011). Global health and aging. Retrived from http://www.who.int/ageing/publications/global_health.pdf