ABSTRACT

Objectives: To update previous reviews and provide a more detailed overview of the effectiveness, acceptability and conceptual basis of communication training-interventions for carers of people living with dementia.

Method: We searched CINAHL Plus, MEDLINE and PsycINFO using a specific search and extraction protocol, and PRISMA guidelines. Two authors conducted searches and extracted studies that reported effectiveness, efficacy or acceptability data regarding a communication training-intervention for carers of people living with dementia. Risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration guidelines. Quality of qualitative studies was also systematically assessed.

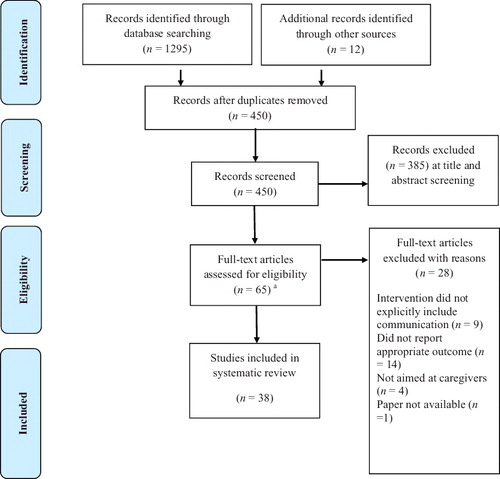

Results: Searches identified 450 studies (after de-duplication). Thirty-eight studies were identified for inclusion in the review. Twenty-two studies focused on professional carers; 16 studies focused mainly on family carers. Training-interventions were found to improve communication and knowledge. Overall training-interventions were not found to significantly improve behaviour that challenges and caregiver burden. Acceptability levels were high overall, but satisfaction ratings were found to be higher for family carers than professional carers. Although many interventions were not supported by a clear conceptual framework, person-centred care was the most common framework described.

Conclusion: This review indicated that training-interventions were effective in improving carer knowledge and communication skills. Effective interventions involved active participation by carers and were generally skills based (including practicing skills and discussion). However, improvements to quality of life and psychological wellbeing of carers and people living with dementia may require more targeted interventions.

The ability to communicate is a fundamental need that impacts on the quality of our relationships and our general sense of health and wellbeing (Jootun & McGhee, Citation2011; Segrin, Citation2001). This is reflected in the experience of people living with dementia who identify that their unmet needs are psychosocial in nature (van der Roest et al., Citation2009). For people living with all types of dementia, their cognitive impairments can affect their ability to communicate in varying ways; such as finding words to express their intentions, retrieving memories or processing the contextual information they need to understand the motivations of others (Schrauf & Muller, Citation2014). This can make it difficult to sustain the everyday conversations that support their social relationships (Kindell, Keady, Sage, & Wilkinson, Citation2016) and exacerbate the feelings of social isolation and exclusion (Ablitt, Jones, & Muers, Citation2009). Family and professional (paid) carers also find these communication impairments very challenging as they contribute to relationship stress (Dooley, Bailey, & McCabe, Citation2015; Jones, Edwards, & Hounsome, Citation2014).Footnote1

A number of studies have demonstrated that caring for someone living with dementia has the potential to have significant negative effects on carers’ physical and emotional health (Gallagher-Thompson et al., Citation2012). Studies have also indicated that carers can identify positive aspects of their role (Brodaty & Donkin, Citation2009) and resilience within a caring role has been shown to be linked to factors such as perceived ability to cope, perceived control and social support (Dias et al., Citation2015; Harmell, Chattillion, Roepke, & Mausbach, Citation2011). The declining neurological capability of people living with dementia is only one of many factors that may influence the quality of their relationships and communicative interactions (Guendouzi & Savage, Citation2017). Compensatory adaptations may enable carers to ameliorate the effects of an individual's cognitive impairment; for example, by findings ways of keeping a conversation going without placing as much pressure on the individual's cognitive resources (Haberstroh, Neumeyer, Krause, Franzmann, & Pantel, Citation2011). Qualitative research indicates that acquisition of knowledge and skills can help facilitate resilience and maintaining a relationship with those cared for (Donnellan, Bennett, & Soulsby, Citation2015). These factors can be supported by communication and interaction based training interventions, which can enhance perceived coping and control (Eggenberger et al., Citation2013). However, the availability of evidence-based support and training for carers- especially family carers- is still limited (Dawson, Bowes, Kelly, Velzke, & Ward, Citation2015; Eggenberger et al., Citation2013).

The current review evaluated the effectiveness and acceptability of communication training-interventions with a view to contributing to greater implementation of such interventions. This review included studies of training-interventions that include a communication component and were aimed at professional and family carers of people living with dementia. Effectiveness and efficacy studies were included. Acceptability data included qualitative and qualitative data regarding the acceptability of the training-intervention to participants (e.g. systematically analysed self-report ratings of whether carers found the intervention satisfactory, helpful). The current review builds on a high quality systematic review of the effectiveness and content of communication skills training interventions by Eggenberger and colleagues. This previous review identified that training increased the communication skills, competencies and knowledge of carers and contributed to improvements in the wellbeing of people living with dementia (Eggenberger et al., Citation2013). However, levels of caregiver burden and behaviour that challenges were not found to significantly change post training. Since the publication of this review a significant number of studies have been published, including 13 new RCTs, and it is considered important to re-examine the evidence-base in light of this. Furthermore, the current review seeks to provide a more detailed account of the conceptual basis of training-interventions.

Method

The review was conducted in accordance with the guidelines provided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & Group, Citation2009). The current review is a mixed methods systematic review. Given that one of the focuses of the review was on acceptability, qualitative data was considered potentially useful in illuminating participant experience, satisfaction and acceptability. A search protocol was developed through team discussion (see ).

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they evaluated training interventions aimed at family or professional carers of people living with dementia. Studies were included from 2010 due to the recent review by Eggenberger, Heimerl, Bennett, Eggenberger, Heimerl, and Bennett (Citation2013); this date was chosen so as not to duplicate the studies included in this previous review. The definitions of communication and interaction are in line with Eggenberger and colleagues and multicomponent interventions were included to align the scope of these two reviews. This was in order to enable readers to draw on both reviews from a common point of reference. See for more details of inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Information sources and study selection

The electronic databases CINAHL Plus, MEDLINE and PsycINFO were systematically searched to identify the appropriate studies to include in the review. Boolean combinations were used to maximise the strength of the search. See for search protocol and list of search terms. Searching of relevant systematic reviews was undertaken. The reference lists of all the included studies were scanned for additional relevant studies. One author was contacted to obtain a paper that was unavailable, but they did not respond and the study was excluded.

Study selection and data extraction

The first two authors (Lydia Morris & Maxine Horne) independently screened 50% of the titles and abstracts using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Cohen's Kappa was calculated at 0.76 indicating reliable agreement. The second author (Maxine Horne) screened the remaining papers.

Data was extracted from included studies by Lydia Morris and Maxine Horne using a data extraction table devised for this purpose. Information extracted from the included studies consisted of: study design, sample characteristics, training interventions used (including intervention characteristics and the conceptual basis of training interventions) and results.

Risk of bias and quality assessment

The methodological quality of all quantitative studies was assessed by the first author (Lydia Morris) using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (Higgins & Green, Citation2011). Although a number of quality assessment tools are available, the PRISMA statement cautions against using these (Liberati et al., Citation2009). Component based approaches are recommended, and specifically the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool (Liberati et al., Citation2009). Studies were assessed for risk of selection bias (including adequacy of randomisation and of allocation concealment), performance bias (whether participants and trainers were blind to treatment group), detection bias (whether assessors were blind to treatment group), attrition bias (related to the amount, nature or handling of incomplete data), reporting bias (whether all expected outcomes have been reported) and other bias (primarily sample size and measures used). Although the current review included a range of quantitative study designs (not just RCTs), the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool provides useful information concerning the risk of bias present in all quantitative study design. For example, if a study is not randomised there will be inadequate randomisation sequence generation and blinding, which will potentially bias the results.

The methodological quality of all qualitative studies was assessed by the second author (Maxine Horn) using the criteria for appraising qualitative studies proposed by Walsh and Downe (Citation2006). Although establishing the reliability and validity of qualitative studies is more contentious than for quantitative studies, steps can be taken to establish the validity of themes presented and to promote quality (Creswell, Citation2013; Creswell & Miller, Citation2000; Shenton, Citation2004). Given these considerations and the variety of methodologies and perspectives of the qualitative studies included, a domains-based approach was used to examine quality. To illustrate the variety of qualitative studies included: one study used a phenomenological action research approach (Lykkeslet, Gjengedal, Skrondal, & Storjord, Citation2014) others used content analysis or videotaped interaction-data (Chenoweth et al., Citation2015; Hammar, Emami, Engstrom, & Gotell, Citation2011; Lykkeslet et al., Citation2014; Soderlund, Cronqvist, Norberg, Ternestedt, & Hansebo, Citation2013); one study focused on organisational acceptability of the training rather than on participant experience (Chenoweth et al., Citation2015).

Data synthesis

Following the principles recommended by Popay et al. (Citation2006) an inductive approach was used to develop a preliminary synthesis and explore the relationships between studies. This includes: grouping studies by relevant clusters (e.g. interventions aimed at family or professional carers), deciding whether to formally assess quality and the tools to use, and formulating a textual description.

Results

Study selection

After de-duplication and exclusion according to the study protocol, 38 studies were included. See for a flow diagram of the numbers of studies identified and excluded during the selection process.

Figure 2. PRISMA flow diagram of selection and exclusion (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Characteristics of included studies

Of the 38 studies identified for inclusion in this systematic review, 21 of the studies were conducted in English speaking nations (UK, US and Australia). The remaining 17 were located in Western Europe. Twenty-two studies evaluated communication skills training interventions for professional staff in care home and hospital settings. The remaining 16 studies evaluated interventions that targeted mainly family carers and they were delivered in family homes and other community settings. See for details of all studies. There were 28 quantitative studies, of which 13 were RCTs and there were 10 qualitative studies.

Table 1. Details of Included studies.

Overall quality assessment and methodological challenges

Quantitative studies

Overall methodological quality was variable across all quantitative studies and only four studies had low bias ratings in three or more domains (Chenoweth et al., Citation2014; De Rotrou et al., Citation2011; Livingston et al., Citation2013; Orgeta et al., Citation2015). See for the overall assessment of risk of bias. Performance bias was present in all of the quantitative studies due to the impossibility of blinding patients and trainers to the intervention being delivered. However, most studies were also subject to detection bias; only seven studies used comprehensive assessor blinding (Ballard et al., Citation2016; Broughton et al., Citation2011; Chenoweth et al., Citation2014; De Rotrou et al., Citation2011; Gitlin, Winter, & Dennis, Citation2010; Livingston et al., Citation2013; Orgeta et al., Citation2015).

Table 2. Risk of bias table using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool.

Eight studies reported adequate randomisation processes and allocation procedures, and therefore reduced selection bias (Ballard et al., Citation2016; Chenoweth et al., Citation2014; De Rotrou et al., Citation2011; Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Livingston et al., Citation2013; Orgeta et al., Citation2015; Prick, De Lange, Twisk, & Pot, Citation2015; van der Ploeg et al., Citation2013). However, attrition levels were often high and rarely reported for each treatment group. Only four studies provided sufficient information to conclude that attrition was sufficiently equal across groups (Cristancho-Lacroix et al., Citation2015; De Rotrou et al., Citation2011; Orgeta et al., Citation2015; Prick et al., Citation2015) (in addition, one small scale dissertation reported no attrition) (Gentry, Citation2011). Four studies were clearly protocol driven and provided enough information to conclude a low risk of reporting bias (Chenoweth et al., Citation2014; Cristancho-Lacroix et al., Citation2015; Livingston et al., Citation2013; Orgeta et al., Citation2015). Ten studies reported small sample sizes (Alnes, Kirkevold, & Skovdahl, Citation2011; Beer, Hutchinson, & Skala-Cordes, Citation2012; Cristancho-Lacroix et al., Citation2015; Cruz, Marques, Barbosa, Figueiredo, & Sousa, Citation2011; Gentry, Citation2011; Haberstroh et al., Citation2011; Liddle et al., Citation2012; Prick et al., Citation2015; Raglio et al., Citation2016; van der Ploeg et al., Citation2013). Eight studies used unstandardised measures (Alnes et al., Citation2011; Bray et al., Citation2015; Broughton et al., Citation2011; Galvin et al., Citation2010; Judge, Yarry, Orsulic-Jeras, & Piercy, Citation2010; Robinson, Bamford, Briel, Spencer, & Whitty, Citation2010; Velzke, Citation2014; Weitzel et al., Citation2011); therefore it is not clear if these are reliable and valid and it is difficult to compare outcomes between studies.

Qualitative studies

Using the criteria for appraising qualitative studies proposed by Walsh and Downe (Citation2006), no included study met all the criteria (See ; see Walsh & Downe, Citation2006, for more detail of the domains assessed). It is possible that when the study was conducted a particular criterion was addressed, but for sake of brevity this was not reported in the journal article and thus cannot be assessed. Only one study (Lykkeslet et al.,Citation2014) indicated that there had been a systematic search of the literature before conducting the study. All the studies appeared to use convenience samples. In Söderlund et al. (Citation2012) sampling is detailed, but one resident was excluded from the study because the approach in the study (Validation Method) did not work for them; this raises questions about what is being evaluated if nurses excluded cases where the approach did not work. In the Söderlund studies there is substantial ethical consideration of the residents living with dementia, but all the written accounts only have limited consideration of the nurse participants.

Table 3. Quality assessment of qualitative studies.

Conceptual basis

Although an implicitly or explicitly person-centred care approach to care was advocated in many of the studies, few of the studies specified a clear conceptual basis for using the communication skills intervention as a stand-alone or multi-component intervention. The study by Haberstroh et al. (Citation2011) on the use of the TANDEM communication approach with family carers of people living with dementia was a clear exception to this trend. A person-centred care approach places an emphasis upon dynamic attunement, which highlights factors such as the significance of the communicative cues of individuals with dementia and the need to adopt an open approach that enables a person with dementia to take the conversational lead (Kitwood & Bredin, Citation1992). Yet as noted by Young, Manthorp, Howells, and Tullo (Citation2011), many communication skills training interventions for the carers of people with dementia appear to assume communication is based on keeping speech simple, maintaining eye contact and removing distractions. Gentry (Citation2011) assumed that a person living with dementia knows what they are trying to communicate but are simply struggling with word finding. Some studies, such as Alnes et al. (Citation2011) and Broughton et al. (Citation2011), appeared to propose a prescriptive way of communicating with a person living with dementia. Such interventions involved specific scripts, or prompts, regarding how to communicate; the effectiveness of communication was evaluated on the basis of whether participants communicated in this particular way.

In a similar way, very few studies explicitly stated the pedagogical basis for teaching or learning, i.e. stating how the training could result in learning by considering how knowledge and skills are conveyed. Some studies (e.g. Conway & Chenery, Citation2016; Cristancho-Lacroix et al., Citation2015; Liddle et al., Citation2012; Livingston et al., Citation2013) treated teaching and learning as the presentation of information, but did not consider how this information would be learnt (e.g. whether reflection or repetition was required). However, others studies (e.g. Chenoweth et al., Citation2015; Haberstroh et al., Citation2011) explicitly included a rationale for the co-creation of knowledge with the participants including reflective learning. Some interventions included peer coaching (Galvin et al., Citation2010) and arguably Alnes et al. (Citation2011), whilst Haberstroh et al. (Citation2011) included group work on case studies.

Family-carers and community based workers

Effectiveness: knowledge, communication skills and strategies

There was consistent evidence that engagement in training interventions resulted in increased knowledge; for example, carers commonly rated knowledge and understanding of dementia, or- less commonly- knowledge of effective communication strategies. Five RCTs examined post-training knowledge (Conway & Chenery, Citation2016; Cristancho-Lacroix et al., Citation2015; De Rotrou et al., Citation2011; Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Liddle et al., Citation2012); all of these utilised TAU control groups. All RCTs found significant changes in knowledge, including improved strategy knowledge and use. Three of these RCTs collected data at multiple follow-up points (Cristancho-Lacroix et al., Citation2015; De Rotrou et al., Citation2011; Gitlin et al., Citation2010) and they found mixed results for the effects of training interventions on knowledge over time. The high quality RCT of the Aide dans la Maladie d'Alzheimer (AIDMA), a multi-component interactive, intervention indicated that there was a significant increase in self-reported understanding of dementia at post-intervention and at six months (De Rotrou et al., Citation2011). Whereas, in Cristancho-Lacroix et al.'s pilot RCT (Citation2015) of a web based intervention a significant improvement in knowledge about Alzheimer's disease was found from baseline to three months, but not at six months. Further, Gitlin et al. (Citation2010) did not find a significant increase in simplification strategy use in the treatment group compared to control group at 16-weeks, but found a significant difference at 24-weeks. In summary, at post-treatment knowledge was increased, but longitudinal follow-up data indicated that these gains in knowledge might be vulnerable to decay over time.

Only one study reported specific communication outcomes; for example, rating of six negative communication forms, such as threatening and criticising (Gitlin et al., Citation2010). However, two previously reported RCTs indicated improvements in strategy use knowledge, which included strategies relating to communication (e.g. using simple familiar expressions, assisting with visual aids, discussing interesting and familiar topics) (Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Liddle et al., Citation2012). All studies reporting communication outcomes found improvements. Although findings generally indicated that communication outcomes were improved by trainings, the studies found somewhat mixed results at follow-up (Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Liddle et al., Citation2012). Gitlin et al. (Citation2010) found significantly less negative communication in the treatment group than the control group at 16-weeks, but not at 24-weeks. As previously reported, they did not find a significant increase in simplification strategy use in the treatment group at 16-weeks, but there was a significant difference at 24-weeks. However, Liddle et al. (Citation2012) found a significant difference in knowledge of communication and other strategies over time (including 6-month follow-up) in favour of the intervention group. The training delivered in these two RCTs differed considerably: Gitlin and colleagues’ training involved numerous home/telephone contacts over 16-weeks, whereas Liddle and colleagues reported a memory and communication skills training consisting of two DVDs. This points to the need for more studies to include specific communication outcomes.

Overall, studies support the effectiveness of interventions with a communication component for family carers in improving knowledge, communication and strategy use. Although training interventions were not demonstrated to be effective across all follow-up time points, interventions were found to be effective post-treatment. This indicates that future studies should include multiple follow-up points to establish if training interventions are able to maintain effects on communication over time.

Effectiveness: carer resilience and behaviour that challenges

Four out of ten studies found that training interventions reduced carer burden (Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Haberstroh et al., Citation2011; Judge, Yarry, Looman, & Bass, Citation2013; Raglio et al., Citation2016); two of these were RCTs (Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Judge et al., Citation2013). Five RCTs found no significant improvement in caregiver burden or strain of training interventions when compared to TAU controls (Cristancho-Lacroix et al., Citation2015; De Rotrou et al., Citation2011; Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Liddle et al., Citation2012; Prick et al., Citation2015). In regards to the two training-interventions evaluated by RCTs that were particularly effective in reducing burden, it is possible that a certain dimension of these two programmes was particularly helpful. For example, both training interventions were skills based (including practicing skills and discussion space). Further, both involved home visits over a number of weeks.

Four out of eight studies found that training interventions reduced carer anxiety and/or depression (Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Judge et al., Citation2010; Livingston et al., Citation2013; Raglio et al., Citation2016), and three of these were RCTs (Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Judge et al., Citation2013; Livingston et al., Citation2013). Again the two interventions described in the previous paragraph were effective (Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Judge et al., Citation2013), as was a home-based programme that involves developing skills and active participation by carers (Livingston et al., Citation2013). One of these also conferred greater improvements and reduced upset regarding behaviour that challenges than TAU control (Gitlin et al., Citation2010). The other RCTs that examined effects of training on behaviour that challenges did not find that the training offered reduced behaviours that challenge significantly more than in the control group (Liddle et al., Citation2012; Prick et al., Citation2015).

Effectiveness: impact on quality of life (QoL), psychological distress and wellbeing of people living with dementia

Four RCTs found no significant post-training improvements in depression, wellbeing, and/or QoL (Liddle et al., Citation2012; Livingston et al., Citation2013; Orgeta et al., Citation2015; Prick, De Lange, Scherder, Twisk, & Pot, Citation2016). Only one case control study found a significant improvement in QoL (Haberstroh et al., Citation2011). A small pre-post study found a decrease in depression amongst people living with dementia (Raglio et al., Citation2016).

Acceptability: satisfaction and qualitative data

Five studies reported satisfaction ratings (Conway & Chenery, Citation2016; Cristancho-Lacroix et al., Citation2015; Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Judge et al., Citation2010; Liddle et al., Citation2012). Given that they used different measures it is hard to compare across studies. However, three studies found that over 90% of participants would recommend the training (Conway & Chenery, Citation2016; Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Liddle et al., Citation2012). Participants in four studies reported high levels of usefulness (over 80%) (Conway & Chenery, Citation2016; Cristancho-Lacroix et al., Citation2015; Judge et al., Citation2010; Liddle et al., Citation2012). However, one study of a web-based multi-component psychoeducational training also reported more mixed levels of overall satisfaction, with low acceptance levels (Cristancho-Lacroix et al., Citation2015). The researchers believed that the web-based training lacked interactivity and social contact that the participants wanted.

Only two studies were identified that qualitatively examined family carer experience of accessing a training intervention with a communication component (Orgeta et al., Citation2015; Yates et al., Citation2016). They both evaluated an individual cognitive stimulation programme, which was found not to promote significant change on a number of outcome measures. However, both the quantitative and qualitative components were of generally good methodological quality and qualitative studies indicated that family carers and people living with dementia experienced a number of benefits. The authors suggest that one of the reasons why cognitive stimulation was found not to be effective in this study (while numerous other studies have demonstrated effectiveness) could have been because the format was individual while previously this had mainly been delivered in a group format (Orgeta et al., Citation2015). They also noted that health-related QoL for carers seemed to be improved and that this could be due to communication and relational components less commonly included in cognitive stimulation approaches. However, additional in-depth qualitative data is certainly required.

Residential care and hospital settings

Effectiveness: Knowledge, communication skills and strategies

Four RCTs reported effectiveness data on a training-intervention (Ballard et al., Citation2016; Chenoweth et al., Citation2014; van der Kooij et al., Citation2013; van der Ploeg et al., Citation2013). The results of two RCTs and two case control studies indicated that those receiving training-interventions demonstrated significant improvements in knowledge and communication skills (Broughton et al., Citation2011; Chenoweth et al., Citation2014; Sprangers, Dijkstra, & Romijn-Luijten, Citation2015; van der Kooij et al., Citation2013). However, one RCT comparing a Montessori- based intervention to an active social interaction control did not report a significant reduction in agitation in intervention participants compared to controls (there was a significant reduction when the analysis was restricted to 12 participants who were no longer fluent in English) (van der Ploeg et al., Citation2013).

The remaining eight studies used pre-post, between-groups or quasi-experimental designs and generally found improved knowledge and/or communication post-training. Four out of the five that reported communication outcomes found post-training improvements in communication and interaction (Alnes et al., Citation2011; Galvin et al., Citation2010; Robinson et al., Citation2010; Weitzel et al., Citation2011). One small study found a non-significant trend towards improved communication (Cruz et al., Citation2011). All four studies that reported knowledge outcomes found improvements post-training (Beer et al., Citation2012; Bray et al., Citation2015; Galvin et al., Citation2010; Velzke, Citation2014).

Acceptability: satisfaction and qualitative data

Quantitative data indicates that training-interventions were effective in improving communication and knowledge. Satisfaction data (where available) was generally high (Broughton et al., Citation2011; Galvin et al., Citation2010; Robinson et al., Citation2010). However, ratings were lower than ratings from studies of family carers; for example, high ratings of relevance and usefulness ranged from 70%–80% (Broughton et al., Citation2011; Galvin et al., Citation2010; Robinson et al., Citation2010) compared to 80%–95% in studies of family carers (Conway & Chenery, Citation2016; Cristancho-Lacroix et al., Citation2015; Liddle et al., Citation2012).

Eight detailed qualitative studies of training-interventions were available (Chenoweth et al., Citation2015; Figueiredo, Barbosa, Cruz, Marques, & Sousa, Citation2013; Hammar et al., Citation2011; Lykkeslet et al., Citation2014; Soderlund et al., Citation2013; Soderlund et al., Citation2016; Soderlund, Cronqvist, Norberg, Ternestedt, & Hansebo, Citation2016; Soderlund, Norberg, & Hansebo, Citation2012, Citation2014). As previously discussed the methodology and focus of these studies was diverse, and the quality was variable. However, studies offered an insight into some of the benefits of training-interventions; for example, seeing behaviour that challenges as communicating a need of the people living with dementia and working more creatively to reduce aggression or increase wellbeing and cooperation (such as, using music or singing) (Hammar et al., Citation2011; Lykkeslet et al., Citation2014). They also provided information regarding how communication could be improved following training interventions; for example, studies on Validation Method indicated that nurses communication could change from being controlling and not attending to the potential meaning of the people living with dementia to being more attentive and following the pace and conversational meaning of people living with dementia (Soderlund et al., Citation2013; Soderlund et al., Citation2012). Further the findings of Chenoweth et al. (Citation2015) indicate some of the challenges in supporting organisational change and maintaining skills learnt in training; for example, managers supporting staff to continue implementing changes by providing adequate staff education and supervision. Given the potential insight into what is beneficial and valued by participants in training-interventions, additional qualitative studies with rigorous methodology are required.

Discussion

This review mapped out the current evidence-base for training-interventions with a communication component for family and professional carers of people living with dementia. A greater number of quantitative studies, with higher quality levels, evaluated training-interventions for family carers than professional carers. Overall training-interventions for family carers were found to improve communication and knowledge (including strategy knowledge and use). The majority of studies that used controlled designs indicated that carers’ skills and competencies improved significantly compared to controls. While results indicated that training-interventions for professional carers also improved communication and knowledge, there were a limited number of controlled studies and so these results must be interpreted with more caution. This review complements Eggenberger and colleagues’ review as the majority of well-controlled studies within their review were with professional carers, whilst the majority of well-controlled studies in the current review were with family carers. Overall, taking into consideration Eggenberger et al. (Citation2013), interventions aimed at both family and professional carers improved communication skills and knowledge in the majority of studies.

In regards to the effects on behaviour that challenges and caregiver burden, results were more mixed. Given the limited numbers of studies including professional carers that examined these outcomes, we are unable to draw conclusions for this group. However, there were a greater number of studies examining burden, psychological distress and behaviour that challenges in samples of family carers. Findings were inconsistent with only a minority of studies demonstrating improvements on these outcomes. These findings are in line with those of Eggenberger et al. (Citation2013) who also found mixed results in these domains for both family and professional carers.

In addition, studies generally indicated that training-intervention did not result in statistically significant changes in QoL, depression or wellbeing in people living with dementia. However, three studies did find improvements in this domain (Chenoweth et al., Citation2014; Haberstroh et al., Citation2011; Raglio et al., Citation2016). The two controlled studies that demonstrated improvements in QoL replicated previous studies (Chenoweth et al., Citation2014; Haberstroh et al., Citation2011; Haberstroh, Neumeyer, Schmitz, & Pantel, Citation2009; Olsson, Jakobsson Ung, Swedberg, & Ekman, Citation2013). One of the interventions was training in person-centred care for professional carers and the other evaluated the TANDEM training, which uses a specific (TANDEM) model of communication to inform strategies to improve communication, such as eliminating distractions, delivering one item of content information in a short simple sentence and repeating messages using the same wording.

Further, there were other RCTs of interventions aimed at family carers that demonstrated improvements on a range of outcomes; such outcomes included carer QoL, anxiety and depression symptoms, and communication skills (De Rotrou et al., Citation2011; Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Judge et al., Citation2013; Livingston et al., Citation2013). All of these involved developing skills and active participation by carers; active participation includes practicing skills within training and applying skills/knowledge as homework. This is in line with previous research that the degree of active participation by carers is associated with how effective an intervention is (Pinquart & Sörensen, Citation2006; Vasse, Vernooij-Dassen, Spijker, Rikkert, & Koopmans, Citation2010). Three interventions were particularly effective in improving family carer resilience and wellbeing in terms of reducing burden and improving psychological distress (Gitlin et al., Citation2010; Judge et al., Citation2013; Livingston et al., Citation2013). Again these interventions involved active participation and were skills based (including practicing skills and discussion space). All involved home visits over a number of weeks. This supports the importance of application and practice by carers for training effectiveness. Further it indicates that to have a significant impact on carer burden and psychological distress intensive interventions including home visits maybe required.

An earlier review found that involvement of the people living with dementia was the strongest predictor of a successful intervention (Brodaty, Green, & Koschera, Citation2003), but the current review did not replicate this (this could be due to the low number of interventions that directly involved people living with dementia). In spite of indications from previous review that individual psychosocial interventions for family carers of people living with dementia were more effective than group interventions (Selwood, Johnston, Katona, Lyketsos, & Livingston, Citation2007), some of the more effective interventions were in a group format (De Rotrou et al., Citation2011; Haberstroh et al., Citation2011). This could be explained by the fact that behavioural management was particularly effective individually (Selwood et al., Citation2007), while coping and communication skills could be effectively delivered individually or in groups (Pinquart & Sörensen, Citation2006; Selwood et al., Citation2007). This makes intuitive sense, as behavioural management could be particularly effective when specific strategies are applied to a nuanced account of an individual's behaviour, whereas coping and communication skills can have a more general application and attendees may also benefit from the social support of a group (Elvish, Lever, Johnstone, Cawley, & Keady, Citation2013).

However, as Eggenberger et al. (Citation2013) highlighted, this is still an emerging field of practice. It was not clear whether some training-interventions had a tangible impact upon the development of specific communication skills that were consistently translated into practice. One of the reasons for this may be that, despite the fact that the review included many controlled studies, the communication skills training was often an aspect of a multi-component training programme. Relatively few studies reported on the impact that the training intervention had upon carers’ ability to utilise specific communication skills. Even fewer studies specified a clear theoretical rationale for why certain strategies were delivered and for the overall training approach used. The study by Haberstroh et al. (Citation2011) on the use of the TANDEM communication approach with family carers of people with dementia was an exception, as it provides clear details of the theoretical model that informed the design and delivery of the training. Detailed qualitative and observational studies could facilitate understanding how relatively subtle changes in communication interactions may impact upon people with dementia (Alsawy, Mansell, McEvoy, & Tai, Citation2017). Further conceptual clarification would be useful to understand the communications mechanisms involved in effective interventions (Elvish et al., Citation2013; Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997; Popay et al., Citation2006); for example, through experimental and dismantling studies to examine the specific components that are effective.

As well as considering limitations to the conclusions that can be drawn from the current review, it is necessary to consider limitations of the systematic review strategy used. Although a broad range of inclusive search terms was used, the authors did not search the grey literature. Therefore, the review is unable to assess the extent to which publication bias could have affected the findings reported. Studies that were not published in the English language were excluded for pragmatic reasons, which could result in reporting bias.

Conclusion

The extant evidence base indicates that communication training-interventions for carers of people living with dementia can improve knowledge of communication strategies and communication skills. Effective interventions involved active participation by carers and were generally skills based (including practicing skills and discussion). Both individual and group interventions were found to be effective. Interventions that had a significant impact on family carer burden tended to be intensive and include regular home visits. Despite this promising evidence, further well-controlled studies are required. It is recommended that such studies clearly specify the conceptual basis of the intervention, use active control groups, and use specific (ideally standardised) measures of communication skills. Further, additional research is required into the ‘active ingredients’ and mechanisms of effective communication trainings.

Acknowledgments

This review was conducted in a project that has received part funding from INNOVATE-UK and the Big Lottery Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Based on previous consultations with key stakeholders, ‘family carers’ is used for informal carers and ‘people living with dementia’ for those they are supporting (Farina et al., Citation2017; Young, Manthorp, Howells, & Tullo, Citation2011).

References

- Ablitt, A., Jones, G. V., & Muers, J. (2009). Living with dementia: A systematic review of the influence of relationship factors. Aging & Mental Health, 13(4), 497–511.

- Alnes, R. E., Kirkevold, M., & Skovdahl, K. (2011). Marte Meo Counselling: A promising tool to support positive interactions between residents with dementia and nurses in nursing homes. Journal of Research in Nursing, 16(5), 415–433.

- Alsawy, A., Mansell, W., McEvoy, P., & Tai, S. (2017). What is good communication for people living with dementia? A mixed-methods systematic review. International Psychogeriatric Association, 29 (11) 1785–1800. doi:10.1017/S1041610217001429

- Ballard, C., Orrell, M., YongZhong, S., Moniz-Cook, E., Stafford, J., Whittaker, R., … Fossey, J. (2016). Impact of antipsychotic review and nonpharmacological intervention on antipsychotic use, neuropsychiatric symptoms, and mortality in people with dementia living in nursing homes: A factorial cluster-randomized controlled trial by the Well-Being and Health for People with Dementia (WHELD) program. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(3), 252–262.

- Beer, L. E., Hutchinson, S. R., & Skala-Cordes, K. K. (2012). Communicating with patients who have advanced dementia: Training nurse aide students. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 33(4), 402–420.

- Bray, J., Evans, S., Bruce, M., Carter, C., Brooker, D., Milosevic, S., … Woods, C. (2015). Enabling hospital staff to care for people with dementia. Nursing Older People, 27(10), 29–32.

- Brodaty, H., & Donkin, M. (2009). Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(2), 217–228.

- Brodaty, H., Green, A., & Koschera, A. (2003). Meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51(5), 657–664.

- Brooker, D., Milosevic, S., Evans, S., Carter, C., Bruce, M., & Thompson, R. (2014). RCN Development Programme: Transforming Dementia Care in Hospitals. http://www.worcester.ac.uk/documents/FULL_RCN_report_Transforming_dementia_care_in_hospital.pdf.

- Broughton, M., Smith, E. R., Baker, R., Angwin, A. J., Pachana, N. A., Copland, D. A., … Chenery, H. J. (2011). Evaluation of a caregiver education program to support memory and communication in dementia: A controlled pretest-posttest study with nursing home staff. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(11), 1436–1444.

- Chenoweth, L., Forbes, I., Fleming, R., King, M. T., Stein-Parbury, J., Luscombe, G., … Brodaty, H. (2014). PerCEN: A cluster randomized controlled trial of person-centered residential care and environment for people with dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(07), 1147–1160.

- Chenoweth, L., Jeon, Y.-H., Stein-Parbury, J., Forbes, I., Fleming, R., Cook, J., … Tinslay, L. (2015). PerCEN trial participant perspectives on the implementation and outcomes of person-centered dementia care and environments. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(12), 2045–2057.

- Conway, E. R., & Chenery, H. J. (2016). Evaluating the MESSAGE communication strategies in dementia training for use with community-based aged care staff working with people with dementia: A controlled pretest-post-test study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(7–8), 1145–1155.

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. London, UK: Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Miller, D. L. (2000). Determining validity in qualitative inquiry. Theory into Practice, 39(3), 124–130.

- Cristancho-Lacroix, V., Wrobel, J., Cantegreil-Kallen, I., Dub, T., Rouquette, A., & Rigaud, A.-S. (2015). A web-based psychoeducational program for informal caregivers of patients with Alzheimer's disease: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(5), e117.

- Cruz, J., Marques, A., Barbosa, A. L., Figueiredo, D., & Sousa, L. (2011). Effects of a motor and multisensory-based approach on residents with moderate-to-severe dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias, 26(4), 282–289.

- Dawson, A., Bowes, A., Kelly, F., Velzke, K., & Ward, R. (2015). Evidence of what works to support and sustain care at home for people with dementia: A literature review with a systematic approach. BMC geriatrics, 15(1), 59.

- De Rotrou, J., Cantegreil, I., Faucounau, V., Wenisch, E., Chausson, C., Jegou, D., … Rigaud, A. S. (2011). Do patients diagnosed with Alzheimer's disease benefit from a psycho educational programme for family caregivers? A randomised controlled study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(8), 833–842.

- Dias, R., Santos, R. L., Sousa, M. F. B. D., Nogueira, M. M. L., Torres, B., Belfort, T., & Dourado, M. C. N. (2015). Resilience of caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review of biological and psychosocial determinants. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 37(1), 12–19.

- Donnellan, W. J., Bennett, K. M., & Soulsby, L. K. (2015). What are the factors that facilitate or hinder resilience in older spousal dementia carers? A qualitative study. Aging & Mental Health, 19(10), 932–939.

- Dooley, J., Bailey, C., & McCabe, R. (2015). Communication in healthcare interactions in dementia: A systematic review of observational studies. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(08), 1277–1300.

- Eggenberger, E., Heimerl, K., Bennett, M. I., Eggenberger, E., Heimerl, K., & Bennett, M. I. (2013). Communication skills training in dementia care: A systematic review of effectiveness, training content, and didactic methods in different care settings. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(3), 345–358.

- Elvish, R., Lever, S.-J., Johnstone, J., Cawley, R., & Keady, J. (2013). Psychological interventions for carers of people with dementia: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 13(2), 106–125.

- Farina, N., Page, T. E., Daley, S., Brown, A., Bowling, A., Basset, T., … Banerjee, S. (2017). Factors associated with the quality of life of family carers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Alzheimer's & Dementia (in press).

- Figueiredo, D., Barbosa, A., Cruz, J., Marques, A., & Sousa, L. (2013). Empowering staff in dementia long-term care: Towards a more supportive approach to interventions. Educational Gerontology, 39(6), 413–427.

- Gallagher-Thompson, D., Tzuang, Y. M., Au, A., Brodaty, H., Charlesworth, G., Gupta, R., ... Shyu, Y. -I. (2012). International perspectives on nonpharmacological best practices for dementia family caregivers: A review. Clinical Gerontologist, 35(4), 316–355.

- Galvin, J. E., Kuntemeier, B., Al-Hammadi, N., Germino, J., Murphy-White, M., & McGillick, J. (2010). “Dementia-friendly hospitals: Care not crisis”: an educational program designed to improve the care of the hospitalized patient with dementia. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 24(4), 372–379.

- Gentry, R. (2011). Facilitating communication in older adults with Alzheimer's disease: An ideographic approach to communication training program for family caregivers. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 71(8-B), 5160.

- Gitlin, L. N., Winter, L., & Dennis, M. P. (2010). Assistive devices caregivers use and find helpful to manage problem behaviors of dementia. Gerontechnology, 9(3), 408–414.

- Guendouzi, J., & Savage, M. (2017). Alzheimer's dementia. In L. Cummings (Ed.), Research in clinical pragmatics (pp. 323–346). Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Haberstroh, J., Neumeyer, K., Krause, K., Franzmann, J., & Pantel, J. (2011). TANDEM: Communication training for informal caregivers of people with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 15(3), 405–413.

- Haberstroh, J., Neumeyer, K., Schmitz, B., & Pantel, J. (2009). Development and evaluation of a training program for nursing home professionals to improve communication in dementia care. Zeitschrift fur Gerontologie und Geriatrie, 42(2), 108–116.

- Hammar, L. M., Emami, A., Engstrom, G., & Gotell, E. (2011). Finding the key to communion-Caregivers' experience of ‘music therapeutic caregiving’ in dementia care: A qualitative analysis. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 10(1), 98–111.

- Harmell, A. L., Chattillion, E. A., Roepke, S. K., & Mausbach, B. T. (2011). A review of the psychobiology of dementia caregiving: A focus on resilience factors. Current Psychiatry Reports, 13(3), 219–224.

- Higgins, J. P., & Green, S. (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org

- Jones, C., Edwards, R. T., & Hounsome, B. (2014). Qualitative exploration of the suitability of capability based instruments to measure quality of life in family carers of people with dementia. ISRN Family Medicine, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/919613

- Jootun, D., & McGhee, G. (2011). Effective communication with people who have dementia. Nursing Standard, 25(25), 40–46.

- Judge, K. S., Yarry, S. J., Looman, W. J., & Bass, D. M. (2013). Improved strain and psychosocial outcomes for caregivers of individuals with dementia: Findings from project ANSWERS. The Gerontologist, 53(2), 280–292.

- Judge, K. S., Yarry, S. J., Orsulic-Jeras, S., & Piercy, K. W. (2010). Acceptability and feasibility results of a strength-based skills training program for dementia caregiving dyads. The Gerontologist, 50(3), 408–417.

- Kindell, J., Keady, J., Sage, K., & Wilkinson, R. (2016). Everyday conversation in dementia: A review of the literature to inform research and practice. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 52, 4, 389–539.

- Kitwood, T., & Bredin, K. (1992). Towards a theory of dementia care: Personhood and well-being. Ageing and Society, 12(03), 269–287.

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P., … Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000100.

- Liddle, J., Smith-Conway, E. R., Baker, R., Angwin, A. J., Gallois, C., Copland, D. A., … Chenery, H. J. (2012). Memory and communication support strategies in dementia: Effect of a training program for informal caregivers. International Psychogeriatrics, 24(9), 1927–1942.

- Livingston, G., Barber, J., Rapaport, P., Knapp, M., Griffin, M., King, D., … Cooper, C. (2013). Clinical effectiveness of a manual based coping strategy programme (START, STrAtegies for RelaTives) in promoting the mental health of carers of family members with dementia: Pragmatic randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal (Clinical research ed.), 347, f6276.

- Lykkeslet, E., Gjengedal, E., Skrondal, T., & Storjord, M. B. (2014). Sensory stimulation - a way of creating mutual relations in dementia care. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being, 9, 23888.

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097.

- Olsson, L. E., Jakobsson Ung, E., Swedberg, K., & Ekman, I. (2013). Efficacy of person‐centred care as an intervention in controlled trials–a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(3–4), 456–465.

- Orgeta, V., Leung, P., Yates, L., Kang, S., Hoare, Z., Henderson, C., … Orrell, M. (2015). Individual cognitive stimulation therapy for dementia: A clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness pragmatic, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Health Technology Assessment, 19(42), 1–108.

- Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic Evaluation. London: Sage.

- Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2006). Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: Which interventions work and how large are their effects ? International Psychogeriatrics, 18(04), 577–595.

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., … Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. Lancaster, UK: ESRC Methods Programme, University of Lancaster. http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/shm/research/nssr/research/dissemination/publications.php

- Prick, A. E., De Lange, J., Scherder, E., Twisk, J., & Pot, A. M. (2016). The effects of a multicomponent dyadic intervention on the mood, behavior, and physical health of people with dementia: A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Interventions In Aging, 11, 383–395.

- Prick, A. E., De Lange, J., Twisk, J., & Pot, A. M. (2015). The effects of a multi-component dyadic intervention on the psychological distress of family caregivers providing care to people with dementia: A randomized controlled trial. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(12), 2031–2044.

- Raglio, A., Fonte, C., Reani, P., Varalta, V., Bellandi, D., & Smania, N. (2016). Active music therapy for persons with dementia and their family caregivers (Vol. 31, pp. 1085–1087). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Robinson, L., Bamford, C., Briel, R., Spencer, J., & Whitty, P. (2010). Improving patient-centered care for people dementia in medical encounters: An educational intervention for old age psychiatrists. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(1), 129–138.

- Schrauf, R. W., & Muller, N. (Eds). (2014). Dialogue and dementia: Cognitive and communicative resources for engagement. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Segrin, C. (2001). Interpersonal processes in psychological problems. New York: Guilford Press.

- Selwood, A., Johnston, K., Katona, C., Lyketsos, C., Livingston, G. (2007). Systematic review of the effect of psychological interventions on family caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of affective disorders, 101(1), 75–89.

- Shenton, A. K. (2004). Strategies for ensuring trustworthiness in qualitative research projects. Education for Information, 22(2), 63–75.

- Soderlund, M., Cronqvist, A., Norberg, A., Ternestedt, B.-M., & Hansebo, G. (2013). Nurses’ movements within and between various paths when improving their communication skills: An evaluation of validation method training. Open Journal of Nursing, 3(2), 265–273.

- Soderlund, M., Cronqvist, A., Norberg, A., Ternestedt, B.-M., & Hansebo, G. (2016). Conversations between persons with dementia disease living in nursing homes and nurses-qualitative evaluation of an intervention with the validation method. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 30(1), 37–47.

- Soderlund, M., Norberg, A., & Hansebo, G. (2012). Implementation of the validation method: Nurses' descriptions of caring relationships with residents with dementia disease. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 11(5), 569–587.

- Soderlund, M., Norberg, A., & Hansebo, G. (2014). Validation method training: Nurses' experiences and ratings of work climate. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 9(1), 79–89.

- Sprangers, S., Dijkstra, K., & Romijn-Luijten, A. (2015). Communication skills training in a nursing home: Effects of a brief intervention on residents and nursing aides. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 10, 311–319.

- Vasse, E., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Spijker, A., Rikkert, M. O., & Koopmans, R. (2010). A systematic review of communication strategies for people with dementia in residential and nursing homes. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(02), 189–200.

- Velzke, K. (2014). Evaluation of a dementia care learning programme. Nursing Older People, 26(9), 21–27.

- Walsh, D., & Downe, S. (2006). Appraising the quality of qualitative research. Midwifery, 22(2), 108–119.

- Weitzel, T., Robinson, S., Mercer, S., Berry, T., Barnes, M., Plunkett, D., … Kirkbride, G. (2011). Pilot testing an educational intervention to improve communication with patients with dementia. Journal for Nurses in Staff Development - JNSD, 27(5), 220–226.

- Yates, L. A., Orgeta, V., Phuong, L., Spector, A., Orrell, M., & Leung, P. (2016). Field-testing phase of the development of individual cognitive stimulation therapy (iCST) for dementia. BMC Health Services Research, 16, 1–11.

- Young, T. J., Manthorp, C., Howells, D., & Tullo, E. (2011). Developing a carer communication intervention to support personhood and quality of life in dementia. Ageing & Society, 31(6), 1003–1025.

- van der Kooij, C., Droes, R., de Lange, J., Ettema, T., Cools, H., & van Tilburg, W. (2013). The implementation of integrated emotion-oriented care: Did it actually change the attitude, skills and time spent of trained caregivers ? Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 12(5), 536–550.

- van der Ploeg, E. S., Eppingstall, B., Camp, C. J., Runci, S. J., Taffe, J., & O'Connor, D. W. (2013). A randomized crossover trial to study the effect of personalized, one-to-one interaction using Montessori-based activities on agitation, affect, and engagement in nursing home residents with Dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(04), 565–575.

- van der Roest, H. G., Meiland, F. J. M., Comijs, H. C., Dersken, E., Jansen, A. P. D., van Hout, H. P. J., … Dröes, R. M. (2009). What do community-dwelling people with dementia need? A survey of those who are known to care and welfare services. International Psychogeriatrics, 221(5), 949–965.