Abstract

Objectives: Despite a large body of sociological and psychological literature suggesting that religious activities may mitigate the effects of stress, few studies have investigated the beneficial effects of religious activities among immigrants. Immigrants in particular may stand to benefit from these activities because they often report a religious affiliation and often occupy disadvantaged positions. This study investigates whether private and public religious activities reduce the negative effects of a lack of physical, social, and socio-economic resources on wellbeing among Turkish and Moroccan young-old immigrants in the Netherlands.

Method: Using data from the Longitudinal Study Amsterdam, cluster analysis revealed three patterns of absence of resources: physically disadvantaged, multiple disadvantages, and relatively advantaged. Linear regression analysis assessed associations between patterns of resources, religious activities and wellbeing.

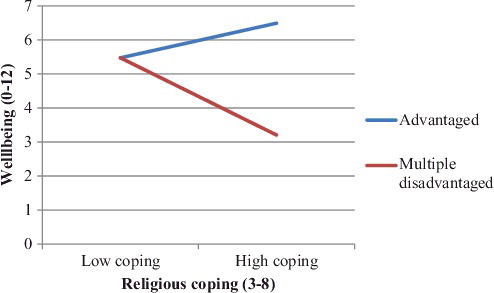

Results: Persons who are physically disadvantaged or have multiple disadvantages have a lower level of wellbeing compared to persons who are relatively advantaged. More engagement in private religious activities was associated with higher wellbeing. Among those with multiple disadvantages, however, more engagement in private religious activities was associated with lower wellbeing. Public religious activities were not associated with wellbeing in the disadvantaged group.

Conclusion: Private religious activities are positively related to wellbeing among Turkish and Moroccan immigrants. In situations where resources are lacking, however, the relation between private religious activities and wellbeing is negative. The study's results highlight the importance of context, disadvantage and type of religious activity for wellbeing.

Introduction

Due to demographic changes as a result of migration and population aging, immigrants are now beginning to constitute the fastest growing segment of the population over 55 in many Western European countries (Zubair & Norris, Citation2015). Gerontological studies find that levels of health and well-being among immigrants are typically lower than among native populations (Bolzman, Poncioni-Derigo, Vial, & Fibbi, Citation2004). These differences are often attributed to structural disadvantages including limited access to socio-economic recourses (Bajekal, Blane, Grewal, Karlsen, & Nazroo, Citation2004), lower levels of education (Uskul & Greenglass, Citation2005), language barriers (Alpass et al., Citation2007), and experiences of discrimination and segregation (Pettigrew et al., Citation1997). In this context gerontologists have found that there is a need to understand factors that protect immigrants against the negative impact of lacking resources and help to sustain high levels of well-being among immigrants who grow old in the receiving country (Zubair & Norris, Citation2015).

Religion might offer behavioural strategies that are beneficial for well-being of specific immigrant groups (Ciobanu & Fokkema, Citation2017). Religious activities, for example, may offer relief to individuals regardless of their position within social hierarchies and regardless of their access to other social and economic resources (Pargament, Citation2001). In order to sustain a relationship with a divine other (Ellison, Citation1991), one does not necessarily need financial resources. Similarly, the idea that life evolves according to a divine plan may be reassuring in contexts of severe deprivation (Schieman, Pearlin, & Ellison, Citation2006) or financial hardship (Bradshaw & Ellison, Citation2010). Religious communities, in addition, may strengthen feelings of belonging and foster a sense of security (Krause & van Tran, Citation1989). Religious activities, in this sense, do not only provide relief by offering a meaningful value orientation but may also aid access to community resources and social support (Koening, Siegler, & George, Citation1989).

Religion promotes well-being (Ellison, Citation1991) and reduces levels of anxiety and depression (Schieman et al., Citation2006). However, empirical evidence, so far, has predominantly been accumulated among native populations in Western Europe (Braam, Beekman, Poppelaars, Van Tilburg, & Deeg, Citation2007) and North America (Levin, Citation1994). Findings do not always replicate well in different contexts. For example, studies in the United States indicated that dimensions of religion served as a buffer against negative consequences of poverty (Diener, Tay, & Myers, Citation2011), chronic illnesses (Landis, Citation1996), low levels of mastery, and bereavement (Ellison & Taylor, Citation1996). A Dutch study, in contrast, suggested that the inverse association of religion with depression was not selectively higher among people with physical impairment, low levels of mastery or chronic illness (Braam, Beekman, Van Tilburg, Deeg, & Van Tilburg, Citation1997). Similarly diverse are findings of studies among immigrant populations, with some studies indicating religion is especially beneficial to immigrants’ well-being (Ciobanu & Fokkema, Citation2017; Kim, Citation2013; Roh, Lee, & Yoon, Citation2013), and others suggesting a strong religious identity is a source of polarization, and segregation that undermines the well-being of immigrants (Verkuyten & Yildiz, Citation2007). Therefore, it is not entirely clear whether findings of protective effects of religion also pertain to immigrant populations living with structural disadvantages in, for example, Western Europe.

The current study investigates the buffering qualities of various religious activities on well-being among young-old Turkish and Moroccan immigrants living in the Netherlands. Two characteristics of these populations are particularly relevant for the current study. First, Turkish and Moroccan immigrants have a high level of socio-economic disadvantage that is neither matched by age-peer native Dutch nor by two other large immigrant groups residing in the Netherlands, i.e. Surinamese and Antilleans. In old age, this gap is only expected to widen because Turkish and Moroccan immigrants are likely to be confronted with more rapid physical deterioration due to their structural disadvantage. Therefore, it is relevant to investigate both how the accumulation of disadvantage affects their well-being and what protective role religion could play in this context. Second, although Turkish and Moroccan immigrants are in general highly religious, there is a variation in their religious behaviour (Braam et al., Citation2010). While almost all Turkish and Moroccan immigrants reported being religious (Schellingerhout, Citation2004), only one-third reports visiting the local mosque weekly (Buijs & Rath, Citation2003). Understanding variation in religious behaviour is essential for investigating its potential protective effect.

Well-being and lack of resources

Situations characterised by lack of resources, particularly income, physical health, social support, and social resources are important antecedent conditions of reduced well-being among older adults (Fry, Citation2000). Individuals who lack such resources are likely to experience higher levels of stress and more often have to deal with hardship and negative life events. For example, individuals who lack financial means not only have trouble paying monthly bills but also have on average greater exposure to chronic and acute stressors, including family and relationship problems, physical limitations, and poor neighbourhood conditions (Bradshaw & Ellison, Citation2010). Similarly, individuals who experience social hardship tend to suffer from elevated levels of distress because of less helpful social ties and support systems, lower levels of self-esteem and personal mastery, and less effective coping styles (Krause, Citation2016). Therefore, the lack of resources in multiple domains is likely to have an increasingly negative effect on well-being and the lack of resources in different domains each elicit their own stress responses on well-being (Halleröd & Seldén, Citation2013). We hypothesize a relative lack of physical, social, and socio-economic resources among Turkish and Moroccan immigrants with a low level of well-being (Hypothesis 1).

Religious experience and meaningfulness of life

There are two partially overlapping theories about the relationship between religion and well-being. The first is that religion offers psychological protection through private religious activities (Pargament, Citation2001). These include, for example, beliefs in God and an afterlife, praying and reading religious texts. Private religious activities often involve ‘role-taking’ (Wikström, Citation1987). In this instance, believers construct a relation with a divine ‘other’, similar to the ties that they build with other individuals. These activities are believed to act as a source of strength, provide the individual with meaning in life, and a sense of happiness (Pargament, Koenig, & Perez, Citation2000). Hypothesis 2a predicts that the more individuals engage in private religious activities their well-being will be.

Another aspect of private religious activities is that they are particularly beneficial when people have problems that are beyond the limit of human agency and control (Reich, Zaustra, & Hall, Citation2010). Because the ‘divine other’ asserts ultimate control over the good and bad situations in a believer's life (Schieman et al., Citation2006), this may lead to a sense of security and meaning in life, especially in difficult situations (Reich et al., Citation2010). It has been suggested that some individuals are capable of managing emotions associated with problematic situations more easily by considering their situation from the standpoint of the ‘God-role’ (Pollner, Citation1989). Therefore, when other resources are lacking, compensation is offered through activities of reappraisal, a quest for meaning in life and a sense of security (Glock, Ringer, & Babbie, Citation1967). Hypothesis 2b states that, among people lacking resources, higher well-being is found among those engaging in more private religious activities compared to those who engaging in fewer religious activities.

Religious community

The second theory focuses on sociological aspects that foster protection by the public aspects of religion. The classical insights from Durkheim (1897/Citation1951), Weber Citation(1922/1964), and CitationJames (1901/1978) are based on the idea that religion conveys protection by way of offering social support and social integration into communities. Public religious activities include activities such as religious attendance and active involvement in religious organizations (Nguyen et al., Citation2013). These activities are believed to provide a sense of belonging to a community and feelings of value and protection (Krause & Bastida, Citation2011). They may contribute to embedding religious individuals in larger supportive networks and provide access to psychological resources such as self-esteem (Schieman et al., Citation2006). This may be crucial for the way in which religion relates to well-being among older immigrants (Ciobanu & Fokkema, Citation2017; Roh et al., Citation2013). These activities may help to unify individuals with a common set of beliefs, values and practices and foster strong religious communities. This may be especially true in contexts where public condemnation of Islam and the pressure to assimilate have increased the salience of the Muslim identity (Verkuyten & Zaramba, Citation2005). Hypothesis 3a states that the more a person engages in public religious activities the higher their well-being is.

Similar to private religious activities, public religious activities may also help individuals deal with life's problems and structural disadvantage (Reich et al., Citation2010). Religious communities may, for example, provide a support networks through which individuals receive direct support in the form of financial aid or indirect support in the form of emotional support (Krause, Citation2016). Moreover, feeling embedded in a community may compensate, in part, for stresses related to a lack of resources. Hypothesis 3b states that among people lacking resources, higher well-being is found among those who engage in public religious activities.

Methods

Sample

Data collection took place in the context of the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam (LASA). LASA focused on investigating the determinants and consequences of trajectories of social, cognitive, physical, and emotional domains of functioning (Huisman et al., Citation2011). In 2012–2013 LASA included a sample of Turkish and Moroccan immigrants. As Turkish and Moroccan immigrants in the Netherlands predominantly live in cities, data collection took place by drawing from the registers of 15 Dutch cities with a population size over 85,000 and with dates of birth between 1948 and 1957. Trained interviewers of the same ethnic background and gender as the immigrants conducted face-to-face interviews. A translated interview in Turkish, Tarafit or Moroccan dialect was available if needed. All questions were either translated by certified translators or translations were taken from prior studies. The recruitment yielded 269 immigrants of Turkish origin and 209 immigrants of Moroccan origin (cooperation rate 45%). Seven persons were excluded due to missing data on well-being and five persons were excluded because they were not born in Turkey or Morocco. In total 260 Turkish and 195 Moroccan immigrants were included in the analysis.

Measurements

Well-being

Well-being is defined as a person's evaluation and judgment of his or her quality of life as a whole (Angner, Citation2010). One of its core components is positive affect, which is often denoted as the emotional component of well-being (Diener, Suh, Lucas & Smith Citation1999). Positive affect is one dimension of the Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, Citation1977). Translations of the CES-D in Turkish and Arabic were derived from Spijker et al. (Citation2004). The independent use of this subscale was supported by others (Jonker et al., Citation2009). This dimension included four items: enjoying life; feeling happy; being hopeful about the future; and feeling as good as other people. Response categories were: rarely or never; some of the time; occasionally; or mostly or always. Values ranged from 0 to 3. Subscale scores ranged from 0 (low) to 12 (high). Cronbach's alpha is 0.79 for Turkish and 0.74 for Moroccan respondents.

Religion

Private religious activities were measured by two questions taken from the abbreviated version of the religious coping measure (Braam et al., Citation2010; Pargament et al., Citation2000). A translation was derived from a previous study in which the validity was found to be satisfactory (Braam et al., Citation2010). The items assessed ways of coping in which religion offered supportive elements including turning to God in times of crises and asking for God's forgiveness. Response categories included the following: never; sometimes; regularly; and very often. Values for these responses ranged from 1 to 4. The scores were summed, ranging from 2 to 8. Cronbach's alpha is 0.83 for Turkish and 0.75 for Moroccan respondents.

For public religious activities we assessed religious attendance by asking respondents to indicate whether and how many times a week they visited a mosque, church or synagogue. Response categories ranged from never (1) to once a week or more (3). Involvement in religious organizations was assessed by asking respondents whether they were an active member of a mosque or another religious organization. Response options were no and yes.

Resources

Physical domain

Physical functioning was assessed using a measurement from a prior study (Smits, Deeg, & Jonker, Citation1997) and the translations in Arabic and Turkish were validated previously (Klokgieters, van Tilburg, Deeg, & Huisman, Citation2017). Respondents indicated whether they experienced difficulty performing seven daily tasks: going up and down a staircase; using own or public transportation; cutting their own toenails; dressing and undressing themselves; sitting down and standing up from a chair; walking outside; taking a shower or bath. Response options were: unable; only with help; much difficulty; some difficulty; no difficulty, coded as 0–4. Sum scores were calculated with a range from 0 to 28. Cronbach's alpha was 0.87 and 0.79 for Turkish and Moroccan respondents, respectively. Chronic diseases. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they suffered from any of seven chronic diseases. The list of diseases was derived from a questionnaire developed by Central Bureau of Statistics Netherlands (Citation1989). Response categories were ‘no’ and ‘yes’. The number of chronic diseases was counted.

Social domain

Marital status. Respondents were asked whether they were married or not. Household members. Respondents were asked whether they had household members apart from their spouse. Contact frequency. Respondents were asked to how often they were in contact with six relationship types: children; grandchildren; children-in-law; other kin (uncles, aunts, siblings, and in-laws); (Moroccan, Turkish) friends, acquaintances; (Dutch or other) friends or acquaintances; (Moroccan, Turkish) neighbours; (Dutch or other) neighbours (Schellingerhout, Citation2004). Response categories ranged from (0) never to (5) every day. A variable was constructed based on the maximum score on the six relationship types. Because very few respondents had maximum scores in the lowest categories, these categories were collapsed. The categories ranged from (0) never to once a week to (1) every day.

Socio-economic domain

Income. Respondents were asked which income category they (together with their partner, if present) classified themselves in. Response categories ranged from 1 to 11 with the lowest category indicating 454–1021 euro and the highest category indicating 2950 euro or more net income per month. Level of education. Respondents were asked how many years they had received any form of education during their lifetime. Responses ranged from 0 to 16 years.

Statistical analysis

We used descriptive analyses to summarize the characteristics of respondents. Differences between groups of Turkish and Moroccan origin were assessed by independent samples t-test and Mann-Whitney U test for continuous data and by Chi-square tests for categorical data.

In order to capture patterns of resources, we performed cluster analysis (K-means). Cluster analysis identifies subgroups of individuals who are most similar to each other, yet distant to other subgroups in their pattern of available resources. We standardized the variables to eliminate effects caused by scale differences. We explored solutions with two to five clusters and selected the solution that provided the best interpretability.

Next, using linear regression analysis, we assessed to what extent the resulting clusters were associated with well-being. In order to avoid multicollinearity for the main effects and interaction effects, all explanatory variables were first centred around the grand mean before they were included in the model. After this measure, the lowest tolerance value included 0.46, which we considered satisfactory for further analysis. Model 1 added confounders, i.e. country of origin, age, and gender. Model 2 investigated the association of disadvantage clusters with well-being. Model 3 added religious variables and Models 4–6 included main effects of disadvantage clusters and interactions with religious coping, religious attendance, and active membership in religious organizations. The contribution of interaction terms to the explanatory power of the model was assessed using an F-statistic. If an interaction term was found to be statistically significant and if it reduced the negative effect of disadvantage on well-being, we considered it a buffer.

There may be differences in religious activities according to country of origin, due to different religious orientations and cultural traditions of host countries spilling over into Turkish and Moroccan communities living in the Netherlands (Braam et al., Citation2010). Turkey was relatively secularized at the time most respondents emigrated, while Morocco was not, which resulted in The traditions of Morocco being strongly rooted in the teachings of Islam (Buitelaar, Citation2009). To analyse whether the results for people of Turkish origin should be reported separately from those of Moroccan origin, we tested all abovementioned models with the groups of respondents separated by national origin. By computing z-scores, we tested for differences in coefficients (Brame, Paternoster, Mazerolle, & Piquero, Citation1998).

Results

The majority (n = 421) of respondents reported that they were affiliated to Islam with a few exceptions reporting affiliation to other religions (n = 6). Eighteen respondents reported no religious affiliation. Nonreligious respondents, however, still engaged in some religious activities, i.e. three reported engaging in private religious activities and two reported attending religious services.

There was variation in religious behaviour (). Seventy-one respondents (16%) indicated that they never attended religious services and 197 (43%) were not involved in activities of religious organizations. While religious coping scores were generally high, the data encompassed the full range of religious coping scores (3–8). Moroccan respondents scored higher on religious coping and religious attendance than Turkish respondents.

Table 1. Description of respondents.

Contact frequency was omitted from the cluster solutions because its contribution was not statistically significant and mean scores varied little over the clusters. The three-cluster solution was adopted, on face-value because it generated both an advantaged subgroup and two distinct disadvantaged subgroups (). The two-cluster solution provided less information because it only distinguished between an advantaged and a disadvantaged group. The four-cluster solution did not generate disadvantaged subgroups that were clearly distinct from each other.

Table 2. Disadvantage clusters.

The first cluster we labelled the ‘multiple disadvantages’ subgroup (n = 59, 13%) (). The majority of respondents in this subgroup were not married and lived alone. They had a low income, and their level of education, physical functioning, and number of chronic diseases fell in between those of respondents from the other two clusters. Respondents in the second cluster, the ‘physically disadvantaged’ cluster (n = 149, 33%), scored low in the physical domain. They often had a spouse and household members. Their income level fell in between that of the two other clusters. The third cluster, the ‘advantaged’ cluster (n = 247, 54%), was characterized by relatively good positions on all domains.

provides descriptive statistics per cluster. The physically disadvantaged cluster was slightly older than the advantaged cluster. The multiple disadvantages cluster included a relatively high percentage of Turkish respondents and the physically disadvantaged cluster included a high percentage of females. The mean scores for religious coping did not differ between the three clusters. The physically disadvantaged cluster was lowest in religious attendance. The multiple disadvantages cluster had the fewest memberships of religious organisations.

In Model 1 () we regressed well-being on control variables, i.e. country of origin, age and gender. Country of origin showed the largest association with well-being. Moroccan respondents scored higher on well-being than Turkish respondents (B = 1.45, SE = 0.31).

Table 3. Linear regression of well-being.

In Model 2 we added disadvantage clusters to the model (Hypothesis 1). Physically disadvantaged respondents and those with multiple disadvantages had lower levels of well-being than advantaged respondents. Patterns of disadvantage affected respondents’ well-being substantially; for respondents with a physical disadvantage and multiple disadvantages there was a decrease of about two units on the well-being scale, which ranged from 0 to 12.

In Model 3 we added religious coping, religious attendance, and religious membership. In support of hypothesis 2a, we found on average higher well-being among those with higher scores in religious coping. Contrary to Hypothesis 3a, religious attendance and religious membership were not related to well-being.

To test whether religion buffered against disadvantage, interaction terms were added to the regression equation (Model 4–6). However, we did not find indications of buffer effects. As Model 4 indicates, the interaction between the multiple disadvantages group and religious coping revealed a negative effect. This indicated, contrary to our Hypothesis 2b, that the more a person with multiple disadvantages is engaged in private religious activities their lower well-being (). The interaction terms with public religious activities were not statistically significant (Models 5 and 6; Hypothesis 3b). In Model 7 (not shown) we added all interaction terms into the model, which yielded again no statistically significant results.

We tested whether Moroccan respondents differed from Turkish respondents with regard to protection by religion. From the results of the stratified analysis (results not shown), z-scores indicated that there was no difference between Turkish and Moroccan respondents. Therefore, the results did not show that it would be meaningful to examine the buffering effect in the two groups separately.

Discussion

We investigated whether private and public religious activities were related to well-being and whether these expressions of religiosity served as a buffer against a lack of resources among young-old Turkish and Moroccan immigrants living in the Netherlands. Although we based our hypotheses on literature about religious coping and spirituality, and had access to relevant data, we failed to find support for most hypotheses. More engagement in private religious activities but not public religious activities was positively related to well-being, and we found no buffering effect of religious behaviour against any sort of disadvantage.

We found that a lack of physical, social or socio-economic resources is negatively related to well-being, thereby supporting Hypothesis 1. The subjects of the study had a significant lack of resources compared to the native population (Reijneveld, Citation1998). Therefore, it may be noted that, in line with findings from others (Halleröd & Seldén, Citation2013), a relative lack of resources may play a role in the well-being of immigrants. The results indicated that it did not matter whether the lack of resources was mostly in the physical domain or in multiple domains simultaneously; the negative relation with well-being was equally negative. This goes against our initial expectation that a lack of resources in multiple domains rather than in one single domain reduces well-being. One explanation could be that having good physical health is so important for well-being in this population of immigrants that it dominates having few resources in other domains (Spirduso & Cronin, Citation2001).

Our results show that having more engagement in private religious activities is positive for well-being. Support for this finding was found in earlier studies among Christian populations in Western Europe (Braam et al., Citation2001) and in North America (Warner, Roberts, Jeanblanc, & Adams, Citation2017). We extended this finding by testing this in a population of predominantly Muslim Turkish and Moroccan immigrants. The findings confirm that private religious activities such as prayer are associated with well-being in immigrants with an Islamic affiliation. It furthermore means that private religious activities may be beneficial for well-being regardless of the religious context or religious affiliation.

We found no support for Hypothesis 3a in which we predicted that more engagement in public religious activities (i.e. attending religious services and active membership in religious organizations) is beneficial for well-being. This finding is contrary to what one would predict based on the theories of Durkheim and Weber that public religious participation is associated with other types of social roles and activities and, by extension, with higher well-being. It is also contrary to studies on this topic in the literature (Fry, Citation2000; Taylor, Chatters, & Jackson, Citation2007). Compared to what is often observed among Dutch populations in general (Braam et al., Citation1997), religious attendance among this population of Turkish and Moroccan origin was relatively high. We found however variation in religious attendance and religious membership. Yet, we did not observe a positive association between well-being and religious attendance or membership. As such, we may conclude that we either cannot observe beneficial consequences of religious activities above a certain threshold or that sources of support that are accessed through religious activities among other groups are accessed differently by Turkish and Moroccan immigrants. Such sources may be support of family members (Idler & Kasl, Citation1997) or ethnic identity (Assari, Citation2013).

No evidence was found to suggest either public or private religious activities act as a buffer against a lack of resources. Instead, we found that private religious activities were even negatively related to well-being when individuals lacked resources in multiple domains. This is contrary to the hypothesis (Hypotheses 2b and 3b), which states that individuals are protected by religious behaviours, especially, when they lack resources. This might be explained by specific characteristics of the subjects’ religion. In interviews with Moroccans living in the Netherlands, Smits, de Vries and Beekman (Citation2005), for example, noted the belief that ‘good Muslims do not have problems’. In other words, religious behaviours in situations that are severely stressful may actually enhance guilt rather than offer relief. The obvious response would be to pray and adopt even more religious coping strategies, which in turn, will enhance feelings of guilt. Disadvantaged individuals may therefore display more religious activities, but are not necessarily rewarded with higher levels of well-being; when resources are lacking in multiple domains, such individuals may even display lower levels of well-being.

We highlight two additional considerations. In this study we captured disadvantage by measuring physical, social and socio-economic resources. The assumed underlying mechanism is that a lack of resources leads to fewer options for compensation and subsequently to stress and hardship, which hampers well-being. However, we did not directly measure the actual stress levels that could be caused by the lack of resources. Future studies may take into account relative contributions of different resources and the potential buffering effect of religious behaviours. Second, the extent to which religion effectively acts as a buffer may depend on other coping strategies employed by the individual (Ellison & Taylor, Citation1996). Some scholars have argued that religion's positive effects work through other beneficial by-products of religious behaviour. Several studies, for example, showed that more frequent church attendance and more spiritual support are associated with greater humility (Krause & Bastida, Citation2011). Greater humility, in turn, offers the capacity to mobilize social support, reduces loneliness, and results in better health (Krause, Citation2016). The question is whether there are preconditions under which religious behaviours affect the well-being of Turkish and Moroccan immigrants.

Four limitations need to be mentioned. First, this study was conducted in highly religious communities. While our study affirmed that religious activities varied, this variation was relatively small especially for religious coping behaviours. As a consequence, our ability to detect protective or positive effects of religious behaviours may have been limited. Second, we employed only two positive religious coping items derived from an, in total, 14-item religious coping scale (Pargament, Citation2001). Although positive religious coping items are found to be the most predictive of positive outcomes (Ano & Vasconcelles, Citation2005), we acknowledge that our scale only partially captures the concept of religious coping in private religious activities. Future studies may take into account other variables, including intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity or meaning of life. Third, the religious coping scale is developed for and mostly used among Judeo-Christian populations (Braam et al., Citation2010). Despite the finding that the positive items on the scale function similarly in relation to depression among Muslim populations (Braam et al., Citation2010), we acknowledge that the items may not fully capture the nuances of Islamic faith (Khan & Watson, Citation2006). For example, for Muslims it may be more important to perform a Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca) or Zakat (give money, food or clothing to the poor) (Khan & Watson, Citation2006) in order to fulfil their religious duties than to ask for Allah's forgiveness directly through ‘confessing sins’ in prayer. Fourth, our study was cross-sectional, which limits possibilities for causal inference. For the present study this may mean that we caught individuals who have been dealing with some of the disadvantages for longer periods of time. In these cases, reduction of stress by religion may be a gradual process, which was not completed yet. To this end, longitudinal studies have, indeed, shown that religion is often beneficial emotionally.

The contributions of this paper are at least threefold. First, we contributed to the religious coping literature by studying a buffering effect of religious activities in predominantly Muslim populations. Religious coping literature, so far, has usually compared religious with nonreligious individuals in Judeo-Christian populations (Ano & Vasconcelles, Citation2005; Harrison et al., Citation2001). Extending the investigation of potential buffering into different communities is important in order to assess whether the protective effect of religious behaviours can be generalized. Second, we investigated patterns or relative absence of physical, social, and socio-economic resources in relation to well-being while simultaneously deducing a potential buffering effect of religious activities. The importance of investigating potential benefits of religious activities in the context of multiple disadvantages has been highlighted previously (Hoverd & Sibley, Citation2013), but few studies have addressed this. Third, given the disadvantaged and vulnerable position of young-old immigrants in Western Europe (Zubair & Norris, Citation2015), it is important to find culturally appropriate ways in which the resilience of these populations can be improved. A prior qualitative study (Ciobanu & Fokkema, Citation2017) suggested that religion serves as an important protective mechanism among immigrants.

We conclude that private religious activities are positively related to the well-being of Turkish and Moroccan immigrants. However, for individuals lacking physical, social, and socio-economic resources, private religious activities are negatively associated with the well-being of Turkish and Moroccan immigrants. The results of the study highlight the importance of cultural context, the type of disadvantage and various religious activities when studying the potential benefits of religious behaviour.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alpass, F., Flett, R., Trlin, A., Henderson, A., North, N., Skinner, M., & Wright, S. (2007). Psychological wellbeing in three groups of skilled immigrants to New Zealand. The Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling, 13(1), 1–13.

- Angner, E. (2010). Subjective well-being. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 39(3), 361–368.

- Ano, G. G., & Vasconcelles, E. B. (2005). Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 461–480.

- Assari, S. (2013). Race and ethnicity, religion involvement, church-based social support and subjective health in United States: A case of moderated mediation. International Journal of Preventive Medicine, 4(2), 208–217.

- Bajekal, M., Blane, D., Grewal, I. N. I., Karlsen, S., & Nazroo, J. (2004). Ethnic differences in influences on quality of life at older ages: A quantitative analysis. Ageing & Society, 24(05), 709–728.

- Bolzman, C., Poncioni-Derigo, R., Vial, M., & Fibbi, R. (2004). Older labour migrants' wellbeing in Europe: The case of Switzerland. Ageing & society, 24(03), 411–429.

- Braam, A. W., Beekman, A. T. F., Poppelaars, J. L., Van Tilburg, W., & Deeg, D. J. H. (2007). Prayer and depressive symptoms in a period of secularization: Patterns among older adults in The Netherlands. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 15(4), 273–281.

- Braam, A. W., Beekman, A. T. F., Van Tilburg, T. G., Deeg, D. J. H., & Van Tilburg, W. (1997). Religious involvement and depression in older Dutch citizens. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 32(5), 284–291.

- Braam, A. W., Schrier, A. C., Tuinebreijer, W. C., Beekman, A. T., Dekker, J. J., & de Wit, M. A. (2010). Religious coping and depression in multicultural Amsterdam: A comparison between native Dutch citizens and Turkish, Moroccan and Surinamese/Antillean migrants. Journal of Affective Disorders, 125(1), 269–278.

- Braam, A. W., Van den Eeden, P., Prince, M. J., Beekman, A. T. F., Kivelae, S. L., Lawlor, B. A., … Mann, A. H. (2001). Religion as a cross-cultural determinant of depression in elderly Europeans: Results from the EURODEP collaboration. Psychological medicine, 31(05), 803–814.

- Bradshaw, M., & Ellison, C. G. (2010). Financial hardship and psychological distress: Exploring the buffering effects of religion. Social Science & Medicine, 71(1), 196–204.

- Brame, R., Paternoster, R., Mazerolle, P., & Piquero, A. (1998). Testing for the equality of maximum likelihood regression coefficients between two independent equations. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 14(3), 245–261.

- Buijs, F., & Rath, J. (2003). Muslims in Europe: The state of research. New York, NY: IMISCOE.

- Buitelaar, M. (2009). Patronen van religiositeit onder Marokkanen. In S. Vallenga, S. Harchaoui, & B. Sijsjes (Eds.), Mist in de polder: Zicht op ontwikkelingen omtrent de islam in Nederland (pp. 47–67). Amsterdam: Askant.

- Central Bureau of statistics (CBS). (1989). Health interview questionnaire. Heerlen, the Netherlands: Central Bureau of Statistics.

- Ciobanu, R. O., & Fokkema, T. (2017). The role of religion in protecting older Romanian migrants from loneliness. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 43(2), 199–217.

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress, Psychological bulletin, 125 (2), 276.

- Diener, E., Tay, L., & Myers, D. G. (2011). The religion paradox: If religion makes people happy, why are so many dropping out?. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101(6), 1278–1290.

- Durkheim, E. (1897/1951). Suicide. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Ellison, C. G. (1991). Religious involvement and subjective well-being. Journal of health and social behavior, 32, 80–99.

- Ellison, C. G., & Taylor, R. J. (1996). Turning to prayer: Social and situational antecedents of religious coping among African Americans. Review of Religious Research, 38(2), 111–131.

- Fry, P. S. (2000). Religious involvement, spirituality and personal meaning for life: Existential predictors of psychological wellbeing in community-residing and institutional care elders. Aging & Mental Health, 4(4), 375–387.

- Glock, C. Y., Ringer, B. B., & Babbie, E. R. (1967). To comfort and to challenge: A dilemma of the contemporary church. Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

- Halleröd, B., & Seldén, D. (2013). The multi-dimensional characteristics of wellbeing: How different aspects of wellbeing interact and do not interact with each other. Social Indicators Research, 113(3), 807–825.

- Harrison, M. O., Koenig, H. G., Hays, J. C., Eme-Akwari, A. G., & Pargament, K. I. (2001). The epidemiology of religious coping: A review of recent literature. International Review of Psychiatry, 13(2), 86–93.

- Hoverd, W. J., & Sibley, C. G. (2013). Religion, deprivation and subjective wellbeing: Testing a religious buffering hypothesis. International Journal of Well-Being, 3(2), 182–196.

- Huisman, M., Poppelaars, J., Van der Horst, M., Beekman, A. T., Brug, J., Van Tilburg, T. G., & Deeg, D. J. (2011). Cohort profile: Longitudinal aging study amsterdam (LASA). International Journal of Epidemiology, 40(4), 868–876.

- Idler, E. L., & Kasl, S. V. (1997). Religion among disabled and nondisabled persons II: Attendance at religious services as a predictor of the course of disability. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 52(6), S306–316.

- James, W. (1901/1978). (Original). The Varieties of Religious Experience. Garden City, NY: Image Books.

- Khan, Z. H., & Watson, P. J. (2006). Construction of the Pakistani religious coping practices scale: Correlations with religious coping, religious orientation, and reactions to stress among Muslim university students. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 16(2), 101–112.

- Kim, Y. S. (2013). Ethnic senior schools, religion, and psychological well-being among older Korean immigrants in the United States: A qualitative study. Educational Gerontology, 39(5), 342–354.

- Klokgieters, S. S., van Tilburg, T. G., Deeg, D. J., & Huisman, M. (2017). Resilience in the Disabling effect of gait speed among older Turkish and Moroccan immigrants and Native Dutch. Journal of Aging and Health. doi: 10.1177/0898264316689324.

- Koening, G. H., Siegler, C. I., & George, L. K. (1989). Religious and non-religious coping: Impact of adaptation in later life. Journal of Religion & Aging, 5(4), 43–51.

- Krause, N. (2016). Assessing the relationships among religiousness, loneliness, and health. Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 38(3), 278–300.

- Krause, N., & Bastida, E. (2011). Church-based social relationships, belonging, and health among older Mexican Americans. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 50(2), 397–409.

- Krause, N., & Van Tran, T. (1989). Stress and religious involvement among older blacks. Journal of Gerontology, 44(1), S4–S13.

- Landis, B. J. (1996). Uncertainty, spiritual well-being, and psychosocial adjustment to chronic illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 17(3), 217–231.

- Levin, J. S. (1994). Religion and health: Is there an association, is it valid, and is it causal?. Social Science & Medicine, 38(11), 1475–1482.

- Nguyen, A. W., Taylor, R. J., Chatters, L. M., Ahuvia, A., Izberk-Bilgin, E., & Lee, F. (2013). Mosque-based emotional support among young muslim Americans. Review of Religious Research, 55(4), 535–555.

- Pargament, K. I. (2001). The psychology of religion and coping: Theory, research, practice. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Pargament, K. I., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. M. (2000). The many methods of religious coping: Development and initial validation of the RCOPE. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56, 519–543.

- Pettigrew, T. F., Jackson, J. S., Brika, J. B., Lemaine, G., Meertens, R. W., Wagner, U., & Zick, A. (1997). Outgroup prejudice in Western Europe. European Review of Social Psychology, 8, 241–273.

- Pollner, M. (1989). Divine relations, social relations, and well-being. Journal of health and Social Behavior, 30(1), 92–104.

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

- Reich, J. W., Zautra, A. J., & Hall, J. S. (Eds.). (2010). Handbook of adult resilience. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Reijneveld, S. A. (1998). Reported health, lifestyles, and use of health care of first generation immigrants in The Netherlands: Do socioeconomic factors explain their adverse position?. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 52(5), 298–304.

- Roh, S., Lee, K. H., & Yoon, D. P. (2013). General well-being of Korean immigrant elders: The significance of religiousness/spirituality and social support. Journal of Social Service Research, 39(4), 483–497.

- Schellingerhout, R. (2004). Gezondheid en welzijn van allochtone ouderen. Den Haag: The Netherlands Institute for Social Research.

- Schieman, S., Pearlin, L. I., & Ellison, C. G. (2006). The sense of divine control and psychological distress: Variations across race and socioeconomic status. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45, 529–549.

- Smits, C. H., de Vries, W. M., & Beekman, A. T. (2005). The CIDI as an instrument for diagnosing depression in older Turkish and Moroccan labour migrants: An exploratory study into equivalence. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 20(5), 436–445.

- Smits, C. H., Deeg, D. J., & Jonker, C. (1997). Cognitive and emotional predictors of disablement in older adults. Journal of Aging and Health, 9(2), 204–221.

- Spijker, J., Van der Wurff, F. B., Poort, E. C., Smits, C. H. M., Verhoeff, A. P., & Beekman, A. T. F. (2004). Depression in first generation labour migrants in Western Europe: The utility of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale (CES‐D). International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(6), 538–544.

- Spirduso, W. W., & Cronin, D. L. (2001). Exercise dose–response effects on quality of life and independent living in older adults. Medicine & science in sports & exercise, 33(6), S598–S608.

- Taylor, R., Chatters, L., & Jackson, J. (2007). Religious participation among older black Caribbeans in the United States. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences & Social Sciences, 62(4), S251–S566.

- Uskul, A. K., & Greenglass, E. (2005). Psychological wellbeing in a Turkish-Canadian sample. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 18(3), 269–278.

- Verkuyten, M., & Yildiz, A. A. (2007). National (dis) identification and ethnic and religious identity: A study among Turkish-Dutch Muslims. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(10), 1448–1462.

- Verkuyten, M., & Zaremba, K. (2005). Interethnic relations in a changing political context. Social Psychology Quarterly, 68(4), 375–386.

- Warner, C. B., Roberts, A. R., Jeanblanc, A. B., & Adams, K. B. (2017). Coping resources, loneliness, and depressive symptoms of older women with chronic illness. Journal of Applied Gerontology. doi:10.1177/0733464816687218.

- Weber, M. (1922/1964). The Sociology of Religion. Translated by Ephraim Fischoff. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Wikström, O. (1987). Attribution, roles and religion: A theoretical analysis of Sunden's role theory of religion and the attributional approach to religious experience. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 26(3), 390–400.

- Zubair, M., & Norris, M. (2015). Perspectives on ageing, later life and ethnicity: Ageing research in ethnic minority contexts. Ageing & Society, 35(5), 897–916.

- Jonker, A. A., Comijs, H. C., Knipscheer, K. C., & Deeg, D. J. (2009). The role of coping resources on change in well-being during persistent health decline. Journal of Aging and Health, 21(8), 1063–1082.