Abstract

Objectives: The paper identifies types of work-family trajectories of men and women and investigates their links with depression at older age.

Method: We use data from the Heinz Nixdorf Recall study, with retrospective information on employment histories and parenthood between age 20 and 50 (1482 men and 1537 women, born between 1925 and 1955). We apply sequence analysis and group trajectories into six clusters for each gender. We test their association with two alternative measures of depression: self-reported depressive symptoms and intake of antidepressant medication. Multivariate models exclude participants with early life depression and adjust for age, marital status, education, and income.

Results: We find clear differences of work-family trajectories between men and women, where women’s trajectories are generally more diverse, and include family leaves and returns into full or part-time work. For men, work-family trajectories are neither related to depressive symptoms nor to medication intake. In contrast, women who returned into full-time work after family leave show more depression than those who return part-time, both in terms of depressive symptoms and intake of antidepressant medication.

Conclusion: Our findings show gender differences in terms of work-family trajectories and their health-related consequences. In particular, findings suggest that mothers who return to full-time work are a vulnerable group for depression at older age and should be the focus of further research attention.

Introduction

The prevalence of depression in our Western society is high and women are diagnosed with depression about twice as often as men (Salk et al., Citation2017). Depression now constitutes the world’s major burden of disease and with demographic change, depression in the ageing population is particularly problematic (Murray et al., Citation2012). Studies demonstrate that, among other factors, people’s work and family situations have an important influence on mental health (Piccinelli & Wilkinson, Citation2000; Sachs-Ericsson & Ciarlo, Citation2000). Yet, despite solid evidence that roles in these two domains vary by gender and are contributing to differences in depression, there are at least two shortcomings of existing research.

Work, family and mental health

Firstly, most existing studies focus on either family or work situation, but only a few integrate both dimensions. For example, multiple studies show that a history of stable and continued employment improves health and well-being, while insecurity or unemployment is associated with a higher risk of mental impairments in later life (Frech & Damaske, Citation2012; van der Noordt et al., Citation2014). Research also shows that stressful working conditions in mid-life increase depression at older age (Wahrendorf et al., Citation2013). However, employment situation cannot be evaluated in isolation from people’s family situation. For most individuals, family and career formations happen around the same time in life and they are highly dependent on each other. In the past, having children often increased men’s likelihood to work full-time while decreasing women’s likelihood to work full-time (Perry-Jenkins et al., Citation2013). Effects of parenthood on mental health are not straightforward: Parents of young children often report increased depressive symptoms (Evenson & Simon, Citation2005) whereas having children in general may increase well-being (Nelson et al., Citation2013; Umberson et al., Citation2010). Thus, early family formation appears to be a vulnerable phase for mental health and therefore, the interplay of work and family situation in this phase should be investigated more closely.

Work-family situation over the life course

Secondly, when it comes to work-family research, most of it stems from the field of occupational health psychology and circles around potential risks from role conflicts or benefits from role enhancements at a given point of time (Allen & Martin, Citation2017; Perry-Jenkins & Wadsworth, Citation2017). However, some shortcomings of this previous research are its often cross-sectional design (Plaisier et al., Citation2008) and the subjective assessment of the interplay (i.e. using questionnaires of perceived work-family conflict). In the current paper, we want to explore the interplay of work and family situations from a different angle, using the life course framework, as multiple studies have shown that both work and family roles change throughout life and continue to influence mental health at older age (Henretta, Citation2007; Wahrendorf, Citation2015). Some other studies used life course methodology to investigate the effect of work-family trajectories on measures of physical and subjective well-being at older age but most of them have done so for women only: Studies from the UK found that women with strong ties to the labor market had higher satisfaction with life and better self-rated health than homemakers (McMunn et al., Citation2006; Lacey et al., Citation2016). Stone et al., (Citation2015) showed that mothers who were engaged in full-time work rated their own health most favorably around the age of retirement. Similar results have been found in US samples (Frech & Damaske, Citation2012; Worts et al., Citation2013). We could only find one study to this date that analyzed the relationship between combined work-family trajectories and mental health, showing no association with depressive symptoms (Benson et al., Citation2017).

Additionally, it has been shown that work and family roles depend largely on the socio-cultural and historical context of the time that people live in and findings cannot be transferred easily to other populations or historic periods (Worts et al., Citation2016). Social policies can influence timings of employment and unpaid family care work over the life course and differ between countries. Research on the presented issue has not yet been conducted in German populations.

Outline of the present study

Therefore, the first aim of this study is to describe employment and family situation over the life course of men and women born in West Germany in mid-twentieth century (1925–1955). Specifically, we aim to identify types of work-family trajectories for men and women, applying the method of sequence analysis. The second aim is to investigate whether certain types of work-family trajectories are associated with two alternative measures of depression at older age.

Methods

Data

We use data from the Heinz Nixdorf Recall (HNR) study, a population-based prospective cohort study. Participants were randomly selected from the population registers from three neighboring cities in the German Ruhr area (Schmermund et al., Citation2002; Stang et al., Citation2005). Baseline data collection was 2000–2003 with two subsequent follow-up examinations in 2006–2008 and 2011–2014. Data was collected at the University Clinic Essen using self-administrated questionnaires, computer assisted personal interviews (CAPI) and clinical examinations. Importantly, as part of the interview the second follow-up includes a retrospective assessment of previous employment histories. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee at the University Clinic Essen and all participants gave written informed consent. More details about the HNR study and its methods are explained elsewhere (Stang et al., Citation2005; Schmermund et al., Citation2002).

Participants

At baseline, a total of 4814 participants, aged 45 to 74 at the time, were recruited (2395 men and 2419 women). The response rate was 55.8%. At the second follow-up examination, 64.1% of the original sample participated (n = 3088). For the current study, full information on employment and family histories is available for 3019 participants (1482 men and 1537 women).

Measures

Depression: Our main outcome consists of two complementary indicators of depression, both measured at second follow-up: (1) self-reported depressive symptoms, and (2) intake of antidepressant medication.

Self-reported depressive symptoms are measured with the German short version of the Centre for Epidemiological Study – Depression Scale (CES-D) (Radloff, Citation1977; Hautzinger & Bailer, Citation1993). It consists of 15 items describing different symptoms of depression, and asking how often these symptoms occurred over the past week on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (”rarely, 0–1 day”) to 3 (”most of the time, 5–7 days”). In case people answered at least 12 (out of 15) items, we created an additive sum score ranging from 0 to 45 with higher values indicating more depressive symptoms (using mean replacement for unanswered items). For the analyses, we decided to include the score as a continuous variable. This, on the one hand, allows for a nuanced investigation of depressive symptoms and mental well-being (going beyond clinically relevant depression as indicated with cut-off points) (Siddaway et al., Citation2017).

As an additional measure, we include intake of antidepressant medication. This measure is based on a general assessment of recorded intake of all medicaments that participants took in the week prior to the examination. On this basis, any medication from the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) groups N06A or N06CA (WHO, Citation2011) was defined as an antidepressant for the present study. In sum, the two measures allow for a comprehensive assessment of depression among older people.

Work-family Trajectories: Work-family trajectories serve as our main independent variable. For this, we combine data on participants’ employment history with data on their family history. Employment histories are derived from a retrospective interview at second-follow up, in which participants gave details on jobs including, among others, the starting and ending date and working hours, and answered questions on parenthood, including the birth year of each biological child. From this information we derive a complete employment trajectory, in terms of employment situation (working full-time, working part-time, and non-employed for any reasons) for each year of age between 15 and the age at data collection, and a family trajectory measuring for each year, whether the participant had at least one child aged 6 or younger (the age where children in Germany generally enter school). By combining these two trajectories, we decided to distinguish the following 6 possible states for each year: (1) Working full-time without children <7, (2) working part-time without children <7, (3) non-employed without children <7, (4) working full-time with children <7, (5) working part-time with children <7, and finally, (6) non-employed with children <7. For each participant, we construct an individual trajectory specifying work-family state at each age between 20 and 50 years age. This range is chosen, because these are the years where work and family responsibilities are most likely to overlap and because the majority of the participants had their first child and first job in their twenties.

Additional Variables: In addition to gender and age, we include marital status, education and income level. Education is measured as total years of formal education, combining both school and vocational training (Unesco, Citation1997). We grouped the score into three categories: low (9–11 years), medium (12–15 years) and high education (16 or more years). Income is measured at second follow-up (based on household income, weighted for number of household members) and divided into tertiles (low, medium, and high). For a few cases income has missing values (5%). Yet, because these missings are neither related to clusters nor to depression, we decide not to apply imputation strategies for the multivariate regression. Finally, we include marital status, again measured at second follow-up. Hereby, we decided to distinguish the four following categories: married, single (never married), divorced or widowed.

Analytical strategy

In accordance with our two aims, the analysis is conducted in two stages: (1) sequence analysis to describe work-family trajectories and to identify distinct types of trajectories and (2) regression modelling to test the associations between types of trajectories and depression at older age. All steps of the analysis are conducted separately for men and women.

Sequence Analysis: To start, we describe trajectories in terms of average years spent in each of the six states and mean number of spells. This allows to see how many years individuals spent in a given work-family constellation and how many state changes an individual went through between age 20 and 50 years. Furthermore, we investigate the overall complexity of individual trajectories and present Shannon’s entropy (with higher values indicating more complex trajectories).

Next, we group individuals with similar work-family trajectories into clusters. To do this, we first calculate distances between individuals' sequences based on Optimal Matching (Abbott & Tsay, Citation2000). Hereby, the distances are calculated based on the number of operations necessary to make one sequence identical to another, either by substituting (so-called ‘substitution costs’) or by inserting and deleting states (so-called ‘indel costs’). In our case, substitution costs are set to 2 if substitutions involve a change in the family status, and to 1 otherwise (e.g. change from full to part-time work only); indel costs are set to 1. Comparing each sequence to all other sequences results in a matrix that quantifies the distances for each pair of individual sequences in the sample and that can then be used to group sequences into clusters based on cluster analyses (‘Ward’s linkage’). To determine the most appropriate number of clusters, for both men and women, we compare solutions between 4 and 10 clusters, including commonly used quality measures: Calinski-Harabasz and Duda-Hart stopping rules (Duda et al., Citation2012; Halpin, Citation2017). We also look at the resulting cluster sizes and evaluate each cluster solution in terms of its content validity, and whether a higher cluster solution adds another cluster of interest. On this basis, we adopt a six-cluster solution (both for men and women).

Regression Analysis: To investigate the relationship between work-family trajectories and depression at older age, a set of multivariate regression models is estimated for each of the two outcome variables (either logistic or linear depending on the outcome variable) with types of work-family trajectories as main independent variable. In addition to types of trajectories, the first model includes age (and age squared). The second model adds education and marital status as potential confounders. In a third model, we add income at older age because it could be an explaining factor between work-family trajectories and depression at older age. Depending on the outcome used (continuous or binary), Tables present unstandardized coefficients or Odds-Ratios, as well as respective measures of model fit (Adjusted R2, F-statistics and C-index). Importantly, to address potential reverse causality (poor health leading to particular trajectories), all regression models exclude participants who reported that they were diagnosed with depression before the age of 30 (8 men and 18 women). All calculations and figures are based on Stata 13 with the Sadi extension for sequence analysis (Halpin, Citation2017).

Results

Sample Description: As seen in , the mean age is nearly identical for both genders (around 69 years). While most men have a high education or a high income, women tend to have medium education or a low income. Most men and women report being married and having children. With regard to our two main outcomes, we see that women have more depressive symptoms and are more likely to report medication intake than men.

Table 1. Sample description (n = 3019).

gives a first impression on the studied work-family trajectories and how these differ between men and women. As expected, men spent on average more years in full-time work than women, while women spent longer periods in non-employment or part-time work. With regard to the complexity of the trajectories, we see that women have higher number of spells and a higher entropy value, indicating that they change state more often and have more diverse work-family trajectories.

Table 2. Characteristics of work-family trajectories, n = 3019.

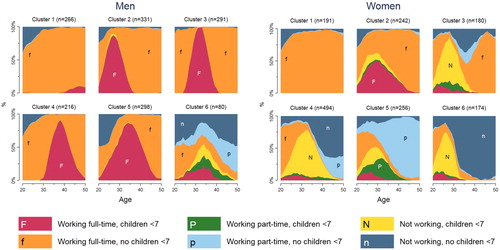

presents chronograms for each identified cluster of work-family trajectories for men and women, showing the distribution of states at each year between age 20 and 50 years. For both genders, we find one cluster of childless individuals with continuous full-time employment (Cluster 1) while all remaining clusters differ between men and women. For men, Clusters 2 to 5 are characterized by uninterrupted full-time employment, only differentiated by the timing of children and entry into the labor market. We find men in full-time work with early children (Cluster 2), few children in their thirties (Cluster 3), later children (Cluster 4) and full time work with many children and late entry into the labor market (Cluster 5). A final cluster collects men with unstable employment trajectories, including longer phases of part-time work or non-employment (Cluster 6). This is the smallest cluster of the sample (n = 80). Apart from that, men’s work-family trajectories are evenly distributed.

Figure 1. Chronograms by cluster of work-family trajectories for men (n = 1482) and women (n = 1537).

For women, types of work-family trajectories appear more heterogeneous. Besides Cluster 1 (childless with continuous full-time employment), Cluster 2 includes women with children who worked full-time with little or no interruptions. In the third and fourth cluster, we find women who left full-time work when they had children and returned after a few years, either back to full-time (Cluster 3) or in part-time (Cluster 4). The fifth cluster includes trajectories of women with children who worked part-time with little or no interruptions (Cluster 5). A final cluster includes women who had children early in their 20s and stayed mostly non-employed (Cluster 6). The latter is the smallest cluster (n = 174).

Multivariable findings: and depict multivariate results for men for depressive symptoms () and medication intake (). Results for women are presented in (depressive symptoms) and (medication intake).

Table 3. Multivariate regression estimates for depressive symptoms for men: unstandardized regression coefficients (b), confidence intervals (CI 95%) and p-values.

Table 4. Multivariate logistic regression estimates for antidepressant use for men: Odds Ratios (OR), confidence intervals (CI 95%) and p-values.

Table 5. Multivariate regression estimates for depressive symptoms for women: unstandardized regression coefficients (b), confidence intervals (CI 95%) and p-values.

Table 6. Multivariate logistic regression estimates for antidepressant use for women: Odds Ratios (OR), confidence intervals (CI 95%) and p-values

Note: All models are additionally adjusted for age and age squared, and participants with early depression are excluded.

For men, results can be summarized as follows: overall, there are no associations between types of work-family trajectories and depression. This is both true for number of depressive symptoms () and for antidepressant intake (). Exceptions are Cluster 2 (full-time work with early children) and Cluster 6 (unstable work with children) where scores for depressive symptoms are slightly higher in Model 1.In case of the remaining covariates, we see that lower education and lower income are significantly related to more depression (both indicators), and that married men report fewer depressive symptoms and are less likely to take antidepressant medications.

Results are different in case of women, where we find significant associations between work-family trajectories and both indicators of depression (see and ). Specifically, women who returned into full-time work after childcare (Cluster 3) report more depressive symptoms and are more likely to take antidepressant medications compared with women who returned into part-time work after childcare (Cluster 4). Notably, this association slightly attenuates when we include education and marital status (Model 2), and additionally, income (Model 3), but remains significant. For the remaining covariates, we again observe an association for income and education (more depression with lower levels), and that married participants have less depression (again for both indicators).

To validate our results, the following two sensitivity analyses are conducted: First, due to the non-normal distribution of depressive symptoms, all analyses are also calculated with log transformations of the depression score. Second, to control for a possible shift in symptoms after treatment, we also estimate models that additionally adjust for antidepressant medication intake. In both cases, analyses (not presented in the article) show similar results.

Discussion

The aim of the present research was to summarize entire work-family trajectories for men and women and to investigate their links to two indicators of depression later in life.

In summary, findings show that men’s work-family trajectories in the HNR cohort are dominated by full-term employment while women’s trajectories are more heterogeneous and often characterized by longer periods of non-employment. While we find no particular type of men’s work-family trajectory associated with indicators of depression at older age, the results suggest that women who return to full-time employment after a longer period of family leave show higher depressive symptoms or antidepressant intake at older age than women who return into part-time work. This association can only partly be explained by education, income or marital status.

Interpretation and integration of findings

The types of work-family trajectories we observe are in accordance with recent sociological studies and reflect the different social roles that men and women took on in West Germany in the mid-20th century (Aisenbrey & Fasang, Citation2017). Men’s attachment to the labor market was very high while women took over most of the household and childcare responsibilities. Past research has highlighted the importance of work for men’s psychological well-being (Cinamon & Rich, Citation2002) and suggested that men with long periods of non-employment have more depressive symptoms later on (Wahrendorf et al., Citation2013). There is only small support for these findings, probably because of the rather stable career of men in our sample. Another possible explanation for the general absence of a relationship between men’s trajectories and depression in the present study is the overall lower prevalence of antidepressant intake for men, which makes it difficult to detect differences between the groups in our study. In a similar vein, previous studies have criticized the assessment of depressive symptoms for being gender biased and not accounting for symptoms that men typically show (e.g. substance abuse (Cochran & Rabinowitz, Citation2003)). Another difficulty is that the men’s trajectories are very similar to each other with full-time employment being the norm. Other characteristics of the trajectories, such as history of financial burdens, work stress or job insecurity could provide additional information and help to identify potential risks of poor mental health for men.

Our findings for women are surprising and contradict past research from the UK that showed higher subjective well-being in mothers who return to full-time employment compared to long-term homemaking mothers and childless women (McMunn et al., Citation2006). We expected closer attachment to the labor market to be beneficial for mental health at older age for women, but this appears not to be the case in our sample. Mothers who took a few years of family leave and returned into full-time work afterwards show higher depressive symptoms and higher probability of antidepressant intake than mothers who returned into part-time work. One possible explanation is that the proportion of single mothers, a particularly vulnerable group (Afifi et al., Citation2006), is highest in that cluster. This idea is further supported in our multivariate findings, where associations between cluster and depression are weakened once marital status is considered. Being a single earner might force these women to return to full-time work and increase the burden on mental health. Along these lines, Zagel (Citation2014) has argued that single mothers in Germany have stronger labor market attachment than their English counterparts and suggests that they might be economically forced to re-enter full-time work. Another argument is that women who take a long family leave take over major childcare responsibilities, that are, in turn, more difficult to hand over when returning to full-time work (Craig, Citation2006; Bianchi, Citation2000). It is possible that mothers who remained in continuous full-time work (without long family leave) shared those responsibilities with other family members, e.g. grandparents. All these aspects are very closely linked to the dominant cultural norms and policies at the time and cultural differences regarding the tradition of mothers’ employment can also explain the deviation in findings between the UK and West Germany.

Strengths and limitations

One major strength of our study is the use of two complementary measurements of depression, allowing for a comprehensive assessment of depression among older people. Specifically, measuring depression via medication intake provides a measure of mental health that is less likely to be biased by self-report. However, antidepressants are sometimes prescribed for other indications besides depression. Measuring self-reported symptoms can help to avoid this potential misclassification.

Further, the present study is one of the first to investigate combined work-family trajectories and their relationship with depression at older age in Germany. Thereby, the use of sequence analysis allowed a more holistic description of people’s life courses and helps to summarize men’s and women’s experiences over many years. The chosen methodology has several strengths and limitations: For creating work-family trajectories we rely on retrospective interviews of the participants and recall bias is a possibility. However, validation studies revealed high accuracy of recalled information, in particular when asking about socio-demographic conditions (Berney & Blane, Citation1997), such as employment histories (Bourbonnais et al., Citation1988; Wahrendorf et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, to limit the number of possible states in the sequence analysis, we only distinguished between full-time, part-time and non-employment and whether participants had children under 7 at the time. However, future research should describe work-family trajectories in more detail and also take into account the type of job, reasons for non-employment and number of children.

Another limitation comes from the time passing between mid-life and the measurement of depressive symptoms. Our sample has a large age range, so that for parts of the oldest cohort the described life events are more than 30 years ago and their work-family trajectories might not affect their level of depressive symptoms as strongly as other age- and disease-related factors. This may be one reason for the small proportion of explained variance in the outcome. On the other hand, given the accumulation hypothesis, it is possible that life course stressors can continue to have an effect on health many years later as they make individuals more vulnerable for depressions and other stress-related diseases (Assari & Lankarani, Citation2016). Further analysis should investigate the relationship between work-family trajectories, chronic diseases and mental health, as diabetes and heart disease are common comorbidities of depression and could also be an explanatory factor for mental health at old age.

Although the sample is representative for the population of men and women born around World War II in Germany and cannot be generalized. A replication of the study in younger cohorts will be necessary as life course social norms are changing fast and specifically women’s employment patterns have changed a lot. At the time, it was a very strong norm for men to work full-time continuously and still common for women to be homemakers (at least for some years). Nowadays, household and childcare responsibilities are more equally shared between the genders and the availability of formal childcare has increased; these developments could be beneficial for employed mothers’ mental health (Milkie et al., Citation2000; Eek & Axmon, Citation2015).

Finally, life courses get more complex and atypical over time and the work-family trajectories can no longer be described easily with standardized categories. Some developments in work and family roles (also including multiple marriages and stepfamilies) over the life course can be accounted for by advanced methods such as multichannel sequence analysis but it will become increasingly harder to identify types or groups. Sabbath et al. (Citation2015) recently showed that 86% of women had unique work-family trajectories. Therefore, future research should not only consider the quantity but also the quality of the roles held by men and women in society, investigating work stress over the life course and individuals’ experiences of role conflicts and role enhancements in the work-family interface. This is where life course and occupational health research can meet.

Further research should not only compare different generations with each other but also compare work-family trajectories across countries, as each country has its own history of family policies with different incentives for specific work-family arrangements that is changing over time. If certain work and family roles in mid-life are associated with vulnerability in mental health at older ages, then another practical implication should be to identify individuals on these trajectories early and offer targeted support for these groups. This could happen in the clinical context (e.g. through life course anamnesis with specific questions about the return to work) as well as in the social and political context, through policy changes (e.g. financial support for single working mothers).

Conclusion

The present study has shown that certain types of work-family trajectories are associated with increased depressive symptoms and more antidepressant intake at older age for women. This may help to explain some of the gender difference in depression at older age. As the interplay of work and family roles over the life course continues to change, there is a need for policies to adapt as well as to support men and women coping with concurring demands in mid-life.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Heinz Nixdorf Foundation [Chairman: Martin Nixdorf; Past Chairman: Dr. jur. Gerhard Schmidt (deceased)] for their support of the HNR study. Final thanks go to Prof. Dr. Johannes Siegrist for his help during the writing process.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abbott, A., & Tsay, A. (2000). Sequence analysis and optimal matching methods in sociology. Sociological Methods & Research, 29(1), 3–33.

- Afifi, T. O., Cox, B. J., & Enns, M. W. (2006). Mental health profiles among married, never-married, and separated/divorced mothers in a nationally representative sample. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 41(2), 122–129.

- Aisenbrey, S., & Fasang, A. (2017). The interplay of work and family trajectories over the life course: Germany and the United States in comparison. American Journal of Sociology, 122(5), 1448–1484.

- Allen, T. D., & Martin, A. (2017). The work-family interface: A retrospective look at 20 years of research in JOHP. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 259–272.

- Assari, S., & Lankarani, M. M. (2016). Stressful life events and risk of depression 25 years later: Race and gender differences. Frontiers in Public Health, 4(9), 49.

- Benson, R., Glaser, K., Corna, L. M., Platts, L. G., Di Gessa, G., Worts, D., Price, D., … Sacker, A. (2017). Do work and family care histories predict health in older women? European Journal of Public Health, 27(6), 1010–1015.

- Berney, L. R., & Blane, D. B. (1997). Collecting retrospective data: Accuracy of recall after 50 years judged against historical records. Social Science & Medicine, 45(10), 1519–1525.

- Bianchi, S. M. (2000). Maternal employment and time with children: dramatic change or surprising continuity? Demography, 37(4), 401–414.

- Bourbonnais, R., Meyer, F., & Theriault, G. (1988). Validity of self reported work history. British journal of industrial medicine, 45(1), 29–32.

- Cinamon, R. G., & Rich, Y. (2002). Gender differences in the importance of work and family roles: Implications for work – family conflict. Sex roles, 47(12), 531–541.

- Cochran, S. V., & Rabinowitz, F. E. (2003). Gender-sensitive recommendations for assessment and treatment of depression in men. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34(2), 132–140.

- Craig, L. (2006). Does father care mean fathers share? Gender & Society, 20(2), 259–281.

- Duda, R. O., Hart, P. E. & Stork, D. G. (2012). Pattern classification. John Wiley & Sons.

- Eek, F. ,& Axmon, A. (2015). Gender inequality at home is associated with poorer health for women. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 43(2), 176–182.

- Evenson, R. J., & Simon, R. W. (2005). Clarifying the relationship between parenthood and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(4), 341–358.

- Frech, A., & Damaske, S. (2012). The Relationships between mothers' work pathways and physical and mental health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 53(4), 396–412.

- Halpin, B. (2017). SADI: Sequence analysis tools for stata. Stata Journal, 17(3), 546–572.

- Hautzinger, M., & Bailer, M. (1993). Allgemeine Depressions-Skala: ADS; Manual. Goettingen, Germany: Beltz-Test-GmbH.

- Henretta, J. C. (2007). Early childbearing, marital status, and women's health and mortality after age 50. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(3), 254–266.

- Lacey, R. E., Sacker, A., Kumari, M., Worts, D., McDonough, P., Booker, C., & McMunn, A. (2016). Work-family life courses and markers of stress and inflammation in mid-life: Evidence from the National Child Development Study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 45(4), 1247–1259.

- McMunn, A., Bartley, M., & Kuh, D. (2006). Women's health in mid-life: life course social roles and agency as quality. Social Science & Medicine, 63, 1561–1572.

- Milkie, M. A., Sayer, L. C., & Robinson, J. P. (2000). Is anyone doing the housework? Trends in the gender division of household labor. Social Forces, 79(1), 191–228.

- Murray, C. J. L., Vos, T., Lozano, R., Naghavi, M., Flaxman, A. D., Michaud, C., … Memish Z. A. (2012). Disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 291 diseases and injuries in 21 regions, 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 380(9859), 2197–2223.

- Nelson, S. K. , Kushlev, K., English, T., Dunn, E. W., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2013). In defense of parenthood: children are associated with more joy than misery. Psychological Science, 24(1), 3–10.

- van der Noordt, M. , IJzelenberg, H., Droomers, M., & Proper, K. I. (2014). Health effects of employment: A systematic review of prospective studies. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 71(10), 730–736.

- Perry-Jenkins, M., Newkirk, K. & Ghunney, A. K. (2013). Family work through time and space: An ecological perspective. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 5(2), 105–123.

- Perry-Jenkins, M., & Wadsworth, S. M. (2017). Work and family research and theory: Review and analysis from an ecological perspective. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 9(2), 219–237.

- Piccinelli, M., & Wilkinson, G. (2000). Gender differences in depression. Critical review. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177(6), 486–492.

- Plaisier, I. , de Bruijn, J. G., Smit, J. H., de Graaf, R., Ten Have, M., Beekman, A. T., … Penninx, B. W. (2008). Work and family roles and the association with depressive and anxiety disorders: Differences between men and women. Journal of Affective Disorders, 105(1–3), 63–72.

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A Self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

- Sabbath, E. L., Guevara, I. M., Glymour, M. M., & Berkman, L. F. (2015). Use of life course work-family profiles to predict mortality risk among US women. American Journal of Public Health, 105(4), e96–e102.

- Sachs-Ericsson, N. & Ciarlo, J. A. (2000). Gender, social roles, and mental health: An epidemiological perspective. Sex Roles, 43(9–10), 605–628.

- Salk, R. H., Hyde, J. S., & Abramson, L. Y. (2017). Gender differences in depression in representative national samples: Meta-analyses of diagnoses and symptoms. Psychological Bulletin, 143(8), 783–822.

- Schmermund, A., Möhlenkamp, S., Stang, A., Grönemeyer, D., Seibel, R., Hirche, H. … Erbel, R. (2002). Assessment of clinically silent atherosclerotic disease and established and novel risk factors for predicting myocardial infarction and cardiac death in healthy middle-aged subjects: Rationale and design of the Heinz Nixdorf RECALL study. American Heart Journal, 144(2), 212–218.

- Siddaway, A.P., Wood, A.M., & Taylor, P.J. (2017). The Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression (CES-D) scale measures a continuum from well-being to depression: Testing two key predictions of positive clinical psychology. Journal of Affective Disorders, 213, 180–186.

- Stang, A., Moebus, S., Dragano, N., Beck, E. M., Möhlenkamp, S., Schmermund, A. … Jöckel, K. H. (2005). Baseline recruitment and analyses of nonresponse of the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study: Identifiability of phone numbers as the major determinant of response. European Journal of Epidemiology, 20(6), 489–496.

- Stone, J., Evandrou, M., Falkingham, J., & Vlachantoni A. (2015). Women’s economic activity trajectories over the life course: Implications for the self-rated health of women aged 64+ in England. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 69(9), 873–879.

- Umberson, D., Pudrovska, T., & Reczek, C. (2010). Parenthood, childlessness, and well-being: A life course perspective. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 612–629.

- Unesco (1997). International Standard Classification of Education-ISCED. Paris, France: Unesco.

- Wahrendorf, M., Marr, A., Antoni, M., Pesch, B., Jöckel, K.-H., Lunau, T., … Dragano, N. (2018). Agreement of self-reported and administrative data on employment histories in a german cohort study: A sequence analysis. European Journal of Population, 1–18.

- Wahrendorf, M. (2015). Previous employment histories and quality of life in older ages: sequence analyses using SHARELIFE. Ageing and Society, 35(09), 1928–1959.

- Wahrendorf, M., Blane, D., Bartley, M., Dragano, N., & Siegrist, J. (2013). Working conditions in mid-life and mental health in older ages. Advances in Life Course Research, 18(1), 16–25.

- WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology. (2011). Guidelines for ATC classification and DDD assignment 2011. Oslo, Norway.

- Worts, D., Sacker, A., McMunn, A., & McDonough, P. (2013). Individualization, opportunity and jeopardy in American women’s work and family lives: A multi-state sequence analysis. Advances in Life Course Research, 18(4), 296–318.

- Worts, D., Corna, L., Sacker, A., McMunn, A., & McDonough, P. (2016). Understanding older adults’ labour market trajectories: A comparative gendered life course perspective. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies, 7(4), 347–367.

- Zagel, H. (2014). Are all single mothers the same’ Evidence from british and west german women’s employment trajectories. European Sociological Review, 30(1), 49–63.