Abstract

Objectives: Frailty, multimorbidity and functional decline predict adverse health outcomes in community dwelling older people and older patients in general hospitals. This study investigates whether these characteristics separately are independent predictors of health outcomes of acute psychiatric hospitalization.

Methods: Observational study in a prospectively sampled cohort of older patients, consecutively admitted to a psychiatric hospital. On admission we assessed frailty (Frailty Index and walking speed); multimorbidity (Cumulative Index Rating Scale Geriatrics (CIRS-G)) and functional status (Barthel Index). We used the Clinical Global Impressions of Improvement scale (CGI-I) as the psychiatric outcome measure, and dichotomized discharge destination as overall outcome measure: favourable (able to return home or previous care level) or adverse (death, or move to higher level of residential care).

Results: We included 120 patients, 74.6 years (±7.8). 52.5% of the patients was frail (FI ≥0.25). The mean level of the CIRS-G was 13.5 (5.4). Mean CGI-I at discharge was 2.8 (± 1.0), indicating moderate improvement in the psychiatric outcome. Neither FI, CIRS-G, nor Barthel scores were, independent of age, sex and diagnosis, associated with the CGI-I. FI was predictive for adverse discharge destination (OR 1.91, 95%CI 1.09–3.37 per 0.1), as were higher CIRS-G (OR 1.19 95%CI 1.06–1.34, per point) and lower walking speed (OR 1.35 95%CI 1.06–1.72 per 0.1 m/s).

Conclusions: Half of our patients were frail and had a high level of multimorbidity. The FI, walking speed and multimorbidity did not predict improvement of psychiatric symptoms at discharge, but independently helped to predict adverse discharge destination.

Introduction

Frailty, multimorbidity and functional impairment are associated with negative health outcomes in older adults (Clegg, Young, Iliffe, Olde Rikkert, & Rockwood, Citation2013; Guralnik, Fried, & Salive, Citation1996; Inouye, Studenski, Tinetti, & Kuchel, Citation2007). These so called geriatric syndromes, defined as multi-causal health problems with high prevalence in old age (Inouye et al., Citation2007), may co-occur independently, but often overlap and occur together (Fried et al., Citation2001; Theou, Rockwood, Mitnitski, & Rockwood, Citation2012).

Frailty is an age related state of increased vulnerability to poor resolution of homoeostasis after a stressor event, which increases the risk of adverse outcomes (Clegg et al., Citation2013; Rockwood, Citation2005).

Frailty is operationalized and validated in two different models: first in the accumulation of deficits model: a Frailty Index (FI) is constructed based on the concept that the more deficits individuals have, the more frail they are. Symptoms, signs, disabilities and diseases are termed as deficits and contain the following domains: cognition, mood, mobility and balance, nutritional status, vision and hearing, (Instrumental) Activities of Daily Living, medical history, selected items of physical examination, or laboratory results (Rockwood & Mitnitski, Citation2007). The sum score of the deficits that are ‘wrong’ is divided by the number of deficits that are scored, resulting in a score between 0 and 1: the higher the FI, the more frail an individual is.

The other concept model of frailty is the ‘physical phenotype’ model. It consists of five items: slow gait speed, weak hand grip strength, unintentional weight loss, self reported exhaustion and low energy expenditure. Every item is scored positive when an individual has a score that is in the lowest quintile score compared to a population based cohort, resulting in a score robust (0), pre-frail (1 or 2) and frail (≥3) (Fried et al., Citation2001). Frailty has mainly been studied in community dwelling older adults (Collard, Boter, Schoevers, & Oude Voshaar, Citation2012; Fried et al., Citation2001; Rockwood et al., Citation2004) and in hospital patients (Partridge, Harari, & Dhesi, Citation2012).

There are indications that frailty is also associated with psychiatric disorders in older persons (Andrew & Rockwood, Citation2007). It is investigated in longitudinal and cross sectional studies in older patients with depression, where it is found to be associated with severity of depressive symptoms (Buigues et al., Citation2015; Collard, Comijs, Naarding, & Oude Voshaar, Citation2014; Collard et al., Citation2015; Soysal et al., Citation2017; Vaughan, Corbin, & Goveas, Citation2015).

Functional impairment is defined as restriction in or lack of ability to perform an activity, because of impairment in physical performance (Lenze et al., Citation2001). It is known as a risk factor as well as a consequence of depression in older adults (Bruce, Citation2001; Lenze et al., Citation2001) and inpatients with psychotic or bipolar disorder (Auslander et al., Citation2001; Bowie, Reichenberg, Patterson, Heaton, & Harvey, Citation2006; Harvey & Bellack, Citation2009; Sanchez-Moreno et al., Citation2009).

Multimorbidity, resulting in complex interactions of several co-existing diseases, is associated with psychiatric disorders like psychosis, bipolar disorder or depression (De Hert et al., Citation2011; Lala & Sajatovic, Citation2012; Penninx, Milaneschi, Lamers, & Vogelzangs, Citation2013).

In older adults with cognitive disorders or dementia associations with frailty, functional impairment and multimorbidity are found as well (Haaksma et al., Citation2017; Oosterveld et al., Citation2014; Robertson, Savva, & Kenny, Citation2013).

Up to now frailty, multimorbidity and functional status have not been studied for their impact in clinical studies in geriatric psychiatry, although they might be as relevant in older psychiatric populations as in older adults in primary care or general hospitals (Benraad et al., Citation2016). This underlines the need to study the impact these geriatric syndromes have on outcomes of treatment in older adults with psychiatric disorders.

We conducted an observational follow up study in older patients with severe mental disorders who were admitted to acute wards for geriatric psychiatry. First, we investigated the prevalence and correlations of geriatric and psychiatric characteristics in patients with different psychiatric disorders at admission. Secondly, we studied whether frailty (measured with a FI or walking speed), multimorbidity (measured with the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale Geriatrics (CIRS-G) (Miller et al., Citation1992)) and functional impairment, (measured with the Barthel index (Collin, Wade, Davies, & Horne, Citation1988)), separately and independent of age, sex and diagnosis, were predictors of the outcome measures at discharge: the score on the Clinical Global Impressions Scale of Improvement (CGI-I) (Guy, Citation1976) and discharge destination.

Methods

We conducted an observational follow up study in a prospectively sampled clinical cohort of older adults who were admitted to an acute department for geriatric psychiatry between 1 February 2009 and 1 August 2010.

Setting

The study was carried out in two acute geriatric psychiatry wards of Pro Persona Mental Health Care, which is a large psychiatric teaching hospital in Nijmegen, the Netherlands. One ward was specialised in older patients with mood disorders, anxiety disorders and psychotic disorders, and the second in patients with Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD). Patients with multimorbidity could be referred to these geriatric psychiatry wards, as treatment for somatic diseases is included in medical care, but patients needing treatment for severe acute somatic problems, (i.e. intravenous therapy or intensive somatic diagnostic procedures) could not be admitted. Geriatric psychiatrists and geriatricians were involved in multidisciplinary treatment.

Subjects

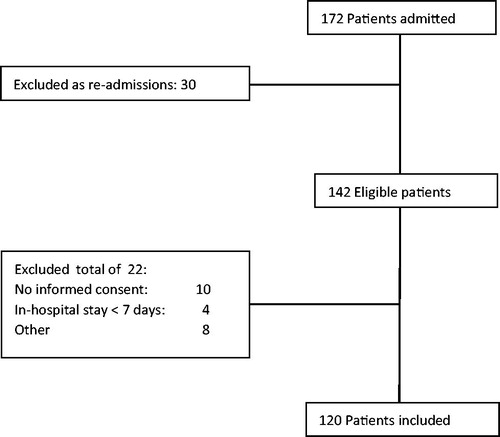

Included were all consecutively referred patients. Excluded were patients in whom no informed consent was given, who stayed less than five days or were not able to understand Dutch. As some patients were readmitted, only the data of the first included admission was analysed in our study. If patients could not give informed consent themselves, we asked their proxies. There were 172 consecutive admissions of 142 different patients in the study period. 120 patients could be included in the study sample ().

As we conducted an observational study with limited extra data collection compared to our usual care, the medical ethical committee approved informed consent as ‘written or oral consent of the patient or proxy’.

Baseline measures

On admission we collected the following demographic data: age, gender, marital status, level of education and living situation. Within the first week after admission all others measures were assessed. Psychiatric diagnoses were made according to the DSM- IV-TR classification (APA, Citation2000). Although patients have usually more than one diagnosis, we used the main diagnosis on Axis 1 or Axis 2 for our study. We categorised all patients in four main diagnosis groups: ‘depressive disorder’, n = 41 (39 major depressive disorder, 2 dysthymia); cognitive disorder and dementia, admitted for ‘BPSD’, n = 41 (9 cognitive disorder nao, 30 dementia, 2 delirium); ‘psychosis and bipolar disorder’, n = 17 (12 bipolar disorder, 5 psychotic disorder) and ‘other psychiatric diagnoses’, n = 21 (5 anxiety disorder, 4 somatoform disorder, 5 substance abuse disorder and 5 adjustment disorder, 2 personality disorder).

Frailty

Frailty was measured in different ways: first, we used the accumulation of deficits model and we constructed a Frailty Index (FI) of 39 items, containing: cognition, measured with MMSE (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, Citation1975); mobility, measured with the Timed Up and go Test (TUG) (Podsiadlo & Richardson, Citation1991); balance, measured by the Performance-Oriented Mobility Assessment (POMA) (Tinetti, Citation1986); nutritional status, measured with the Body Mass index Score. Additionaly vision, hearing, Instrumental Activities of Daily Living, number of medications, medical history according to the family practitioner, selected items of physical examination, and laboratory results at admission were included. All items are scored according to the procedure recommended for FI construction (Searle, Mitnitski, Gahbauer, Gill, & Rockwood, Citation2008). See Supplementary, Table 1 for included items and scoring options of each individual item of the FI.

To prevent overlap, we have excluded psychiatric and ADL items. The FI contained only one global item on IADL. Former research has shown that FI scores <0.08 indicate being robust, a score between 0.08 and 0.25 indicates pre-frailty state, and a score of >0.25 indicates being frail, whereas a score above approximately 0.6 is considered as the maximum observable score for people alive (Rockwood & Mitnitski, Citation2006).

Secondly, because of its predictive validity for mortality and its ease of use, we have used walking speed as a separate measure of frailty (Studenski et al., Citation2011). We used the average walking speed in meters per second over 6 meters. Generally, a walking speed of >1.0 m/s is judged as good and <0.8 indicates probable frailty.

However, walking speed is also part of the ‘physical frailty’ phenotype (Fried et al., Citation2001). As self reported exhaustion and low energy expenditure overlap with symptoms of several severe mental disorders, we have measured hand grip strength and nutritional status besides walking speed and chosen not to take the full physical frailty phenotype into account in our study.

Hand grip strength (HGS) was measured in kilograms with the Jamar Dynamometer, using the dominant hand, taking the best score of three consecutive attempts (Desrosiers, Bravo, Hébert, & Dutil, Citation1995). Overall, a hand grip strength of women >18 kg and of men >30 kg is considered to be adequate. We used the Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) (range 0–30: score <17 indicating undernutrition, 17–23.5: risk for undernutrition, and 24–30: well nourished) as measure for nutritional status (Rubenstein, Harker, Salvà, Guigoz, & Vellas, Citation2001).

Multimorbidity

Multimorbidity was measured with sum score of the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale Geriatrics (CIRS-G) (Miller et al., Citation1992). It measures the lifelong cumulative burden of diagnosed diseases in 14 domains: 13 domains of different somatic organ systems and the psychiatric domain. Each item can be scored from 0–4 (range 0–56, higher score: more multimorbidity). Besides the sum score, we used the Comorbidity Index: the number of items scoring equal or greater than 2, indicating burden of at least two relevant diseases. As all patients scored 3 or 4 on the psychiatric domain, we were interested in a comorbidity index ≥3: having two relevant diseases besides the psychiatric disease.

Functional status

Functional status was measured with the Barthel index, a scale to measure activities of daily living, consisting of 10 items, two items can be scored 0 or 1, two items 0 to 3 and 6 items 0 to 2 (range 0–20, higher score, more independent) (Collin et al., Citation1988).

All prospective measurements were conducted by professionals who were involved in patient care: two residents in training for geriatrician and one in training for psychiatrist (for history taking, physical and psychiatric examination, psychosocial history, MMSE), all trained in data acquisition by and under supervision of one psychiatrist and two different geriatricians and by nurses (Barthel), a dietician (BMI, MNA), and physical therapist (6 meter walking test, Hand grip Strength, TUG, POMA).

Outcome measures

We defined two different treatment outcome measures at discharge as dependent variables in our study: 1. the Clinical Global Impressions of Improvement scale (CGI-I) as psychiatric outcome measure and 2. dichotomized Discharge Destination as overall outcome measure: favourable (able to return home or previous care level) or adverse (death, or move to higher level of residential care).

Clinical global impressions of improvement (CGI-I)

The severity of psychiatric disorders is usually measured by specific severity scales, making it difficult to compare the severity of different psychiatric disorders, or the level of improvement after treatment. For this reason, we have assessed the severity of the different psychiatric disorders by Clinical Global Impressions Scales. We used an expert panel of three professionals, who were not involved in the treatment of the included patients, to assess CGI scales: a psychiatrist (PH), a geriatrician (CB) and a senior resident in geriatrics (NL). They assessed the scales independently and retrospectively.

To assess the severity of the mental disorders at admission we used the Clinical Global Impressions Severity Scale at Admission (CGI-SA), and at discharge the Clinical Global Impressions Severity Scale at Discharge (CGI-SD) (Guy, Citation1976). We used the Clinical Global Impressions Scale of Improvement (CGI-I) to assess the extent of improvement or worsening of the psychiatric symptoms at discharge (Guy, Citation1976). The CGI scales provide an overall clinician-determined summary measure that takes into account all available information, including knowledge of the patient’s history, psychosocial circumstances, symptoms, behavior, and the impact of the symptoms on the patient’s ability to function (Busner & Targum, Citation2007). The CGI Severity scales are seven point scales scoring from 1 (normal, no symptoms) to 7 (very severely ill). The CGI-I is a seven point scale scoring from 1 (very much improved) to 7 (very much worse), with a score of 4 indicating no change. The CGI scales are validated for different psychiatric disorders (Berk et al., Citation2008; Pinna et al., Citation2015; Spielmans & McFall, Citation2006), but not specifically in older adults, although older populations are taken into account in one large study that adequately validated the CGI scales in an inpatient clinic, which showed good overall validity (Berk et al., Citation2008). We used a scoring guideline and a matrix with examples how to score outcomes in different disorders (Brodaty, Draper, & Low, Citation2003; Busner & Targum, Citation2007; Kadouri, Corruble, & Falissard, Citation2007; Spearing, Post, Leverich, Brandt, & Nolen, Citation1997). The CGI-SA was scored using the admission report, which includes both the patient’s and proxy’s psychiatric and medical history, psychiatric and physical examination, social circumstances and level of functioning. At discharge the CGI-SD and CGI-I were scored using the discharge letter. If the discharge letter was unavailable, the last treatment plan before discharge was used.

The CG-I scales are not meant to take the influence of somatic morbidity into account. This was stressed in the scoring guideline. To improve our score reliability, we conducted a pilot assessment procedure in which we independently scored 10 patients, who were admitted to the geriatric psychiatry department before the study period (S. D. Targum, Busner, & Dunn, Citation2008; S. D. Targum, Busner, & Young, Citation2008).

To compose one score for the CGI-SA, the GCI-SD and the CGI-I for each patient, we took the mean of the scores by the three panel members. To establish the interrater reliability of the average CGI scores (CGI-SA, CGI-SD and the CGI-I) of the three raters we calculated an intra class correlation coefficient (ICC). The ICC for the CGI measurements were ‘good’ to ‘very good’, showing a score of 0.77 for the CGI-SA; 0.87 for the CGI-SD and 0.91 for the CGI-I.

Discharge destination

We used ‘Discharge Destination’ as a dichotomised overall health outcome measure: favourable (able to return home or previous care level) or adverse (death or move to a higher level of residential care compared to the situation before admission).

Analysis

To analyse differences in demographic variables as well as outcomes between the diagnosis groups, we used an one way ANOVA for continuous and chi square tests for categorical variables, with a p value significance of 0.005, as Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

The Pearson Correlations Coefficient (CC = r) was used to analyse correlations between age, FI, walking speed, Barthel, CIRS-G, Hand Grip Strength, MMSE and MNA as well as their correlations with the CGI-SA, CGI-SD and the CGI-I.

We performed four linear regression analyses to investigate whether the FI, CIRS-G, the Barthel, and walking speed, separately are predictors for the CGI-I as dependent variable. We used age, gender, level of education, marital status, living independent or not before admission, psychiatric diagnosis group and the CGI-SA as covariates to correct for independency towards these prediction measures, which are already used in psychiatric studies.

We performed four logistic regression analyses with the FI, CIRS-G, Barthel and walking speed, each as separate independent variable and Discharge Destination as dependent variable.

Again, we included age, gender, level of education, marital status, living independent or not before admission, psychiatric diagnosis group and the CGI-SA as covariates.

Results

Description of demographic, psychiatric and geriatric measures at baseline: prevalence and correlations

shows that 63 (52.5%) patient had a FI ≥0.25; 55 (49.1%) a walking speed <0.8 m/s or were unable to walk. 52 (46.4%) Patients had a Hand Grip Strength below the Fried cut of score and 105 (92.1%) were undernourished or were at risk for undernutrition.

Table 1. Demographics, psychiatric and geriatric characteristics on admission.

Forty-four patients (37.9%) scored as frail (FI ≥0.25), had at least one problem in ADL (Barthel <19), and had at least two or more relevant diseases besides the psychiatric disease (CI score ≥3). 14 (12.1%) Patients were robust, functionally independent and had a low CI score of ≤3.

shows these measures at admission and outcomes of treatment in the four different diagnosis groups. Neither the FI, CIRS-G, Barthel nor walking speed differed significantly between diagnosis groups, nor was the CGI-SA.

Table 2. Psychiatric and geriatric variables on admission and at discharge per diagnosis group.

Besides differences in mean age and the finding that patients with ‘psychosis or bipolar disorder’ were less frequently married (p < 0.05), there were no differences in demographics between the four diagnosis groups (data not shown).

Higher age was correlated with higher scores on the Frailty index (r = 0.36, p = 0.000), CIRS-G (r = 0.24, p = 0.008), lower scores on the Barthel (r = 0.32, p = 0.001) and lower walking speed (r = 0.35, p = 0.000). Neither gender, level of education nor marital status were correlated with geriatric syndromes.

Supplementary Table 2 shows that most geriatric measures were intercorrelated, but did not correlate with CGI-SA, CGI-SD and the CGI-I.

Outcomes at discharge

Clinical global impressions of improvement: CGI-I

The results of the linear regression analyses for the four different predictors are shown in .

Table 3. FI, Walking speed, CIRS-G and Barthel as predictors for Clinical Global Impressions of Improvement (CGI-I) in multivariable linear regression models.

Neither the FI, CIRS-G, Barthel, nor walking speed were independent predictors of CGI-I in the whole sample. Patients with ‘BPSD’ had the highest CGI-I and patients with a ‘depressive disorder’ the lowest CGI-I, as analysed with the ANOVA. In the linear regression analyses, the group of patients with ‘BPSD’ showed significantly worse improvement in all four multivariable models, compared to patients with ‘depressive disorders’. The subgroups were too small to investigate interactions between diagnoses, geriatric variables and the CGI-I. None of the other co-variates were associated with the CGI.

Discharge destination

Seventy-seven (64%) patients had a favourable discharge outcome and were able to return to their own living situation. Forty-three patients (36%) had an adverse discharge outcome, of whom six patients died (see ).

The FI was a significant predictor for this adverse outcome (Table 4): OR 1.91, 95% CI 1.09–3.37 (per 0.10 point increase), as were the CIRS-G: OR 1.19 95% CI 1.06–1.34 (per 1 point increase), and walking speed: OR 1.35 95% 1.06–1.72 (per 0.10 meter per second slower).

Patients admitted with ‘BPSD’ had a high odds on adverse discharge destination compared to patients with depressive disorders. Being unmarried or widowed gave higher odds on adverse outcome than being married. Patients who lived independently had a higher odds on an adverse discharge destination than patients who already lived in residential or nursing home care, which seems logical.

Discussion

This observational follow up study is the first, as far as we know, to assess prevalence of geriatric characteristics at geriatric psychiatry admission and their value as predictor for outcomes at discharge. None of the four independent geriatric variables were independent predictors for the CGI-I scores. Nevertheless, frailty, multimorbidity and lower walking speed had predictive power for less favourable discharge destination.

Due to the observational design, with a participation grade of 84.5% by broad inclusion criteria, these results are likely to have high extern validity for similar psychiatric populations.

On the other hand, we studied only one psychiatric hospital, and patients therefore may not be representative for all Dutch departments of geriatric psychiatry, where patients with dementia, serious multimorbidity frailty might not be admitted.

Geriatric measures at admission

We found that half of the patients were frail, as evaluated with a FI constructed according to accumulation of deficits paradigm, and as measured with walking speed; there was a high level of multimorbidity. Most patients had at least functional impairments in one domain, and were at risk for undernutrition or undernourished at admission.

Frailty, multimorbidity and functional impairment were found to be significantly correlated, resulting in a high percentage of overlap (37.9%), in concordance with larger population based studies (Blodgett, Theou, Kirkland, Andreou, & Rockwood, Citation2015; Fried et al., Citation2001; Theou et al., Citation2012). Our FI did hardly contain items of functional status, but we included somatic items. Nevertheless, the correlations between FI and the CIRS-G and the Barthel were both high. Although somatic items are incorporated in the FI, this does not mean that CIRS-G is a part of the FI. In the FI the somatic items are dichotomised and are incorporated in a model of accumulation of deficits. The CIRG-G is, like the FI, a model of deficit accumulation, but only of diseases, and also expresses disease severity. Together a FI, Barthel and CIRS-G result in a comprehensive overview of older psychiatric patients. If persons have problems in on or more of these geriatric domains, they could benefit from a multidisciplinary Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA) (AGS, Citation1989) in order to assess more geriatric syndromes as risk for falls, cognitive decline or urinary incontinence as well as life style, quality of life and advanced care planning. Subsequently, a CGA should be used to develop a coordinated care plan to focus interventions on all the relevant problems for individual persons.

Table 4. FI, Walking speed, CIRS-G and Barthel as predictors for ‘Adverse Discharge Destination ‘in uni- and multivariable logistic regression models.

When focussing on the FI, we found that higher age was associated with the FI, although the association seems not as strong as in population based studies (Mitnitski, Graham, Mogilner, & Rockwood, Citation2002; Song, Mitnitski, & Rockwood, Citation2010) and notably, female sex was not associated with frailty in this population, in contrast with community based studies (Gordon et al., Citation2017).

In our study the prevalence of frailty as measured with a FI (52.5%) is much higher than in community dwelling older adults (13.6%) (Collard et al., Citation2012). The mean of our FI was somewhat lower compared to studies in general hospitals (Evans, Sayers, Mitnitski, & Rockwood, Citation2014; Krishnan et al., Citation2014; Ritt, Ritt, Sieber, & Gaßmann, Citation2017), and in one other geriatric psychiatric ward (Jacobs, Benraad, Wetzels, Olde Rikkert, & Kramers, Citation2017). These FIs contained more ADL items than our FI.

Depression is the only mental disorder in older adults that has been investigated in relation to frailty in cross sectional and longitudinal studies. In almost all these studies, the Fried criteria were used to measure frailty, showing a prevalence of frailty of 40.4% in mainly outpatient populations with depression (Soysal et al., Citation2017).We could not compare the FI with the full five item Physical frailty phenotype criteria. The three Fried items we have taken into account, gait speed, grip strength and nutritional status, had a higher prevalence of limitations compared to older community populations (Fried et al., Citation2001) and to an older outpatient population with depression (Collard et al., Citation2015).

The mean CIRS-G score (13.5, SD 5.4) was comparable to scores in patients admitted to geriatric wards in medical hospitals (Dias et al., Citation2015; M. Miller et al., Citation1992; Ritt et al., Citation2017).

Clinical global impressions scales

The application of the CGI scales as a single measurement for clinical impression of severity and improvement across psychiatric diagnoses proved to be feasible and reliable with a good to very good ICC. The scores at baseline and admission are in line with one validation study of CGI scales in an inpatient psychiatric setting, including older patients (Berk et al., Citation2008). As it was scored by an independent consensus panel, it had to be scored retrospectively.

The geriatric predictors and the CGI measures were not mutually associated, suggesting the severity of psychiatric disorders to be independent of geriatric syndromes and the CGI scales to be valid instruments to score severity or improvement of psychiatric symptoms separate from the presence of geriatric syndromes.

Outcome: the CGI-I

This lack of correlation foreboded the lack of predictive value in predicting the CGI-I scores: the improvement in CGI-I scores at discharge, which was overall ‘slight’, was independent of the presence of geriatric syndromes, nor was it associated with any of the covariates.

The diagnosis group of ’BPSD’ showed significant less improvement in all four analyses compared to patients with depressive disorders. This confirms former studies, which have shown that severe BPSD are difficult to treat (Ballard & Corbett, Citation2013; Kales, Gitlin, & Lyketsos, Citation2015).

The diagnosis groups were too small to analyse possible interactions between diagnoses, predictors and CGI-I scores, as we would possibly expect: in depressive disorders, cross-sectional and longitudinal studies show bidirectional associations between frailty and depression (Collard et al., Citation2014; Collard et al., Citation2015; Soysal et al., Citation2017; Vaughan et al., Citation2015), although there are yet no treatment studies taking frailty as predictor into account (Benraad et al., Citation2016). The same accounts for studies for other psychiatric disorders and multimorbidity (Cuijpers et al., Citation2014; De Hert et al., Citation2011; Penninx et al., Citation2013; Walker, McGee, & Druss, Citation2015) and studies on BPSD (Brodaty & Arasaratnam, Citation2012; Gentile, Citation2010).

In the whole sample, only few patients were robust or without multimorbidity, which also may have covered possible associations with geriatric syndromes.

Notable is the fact that we did not find covariates known from studies on depression in older adults, such as age, male gender or severity of the psychiatric symptoms at admission, to be associated with the CGI-I (Calati et al., Citation2013; Tedeschini et al., Citation2011).

Outcome: discharge destination

One third of the patients could not return to their former living situation, six persons even died in their hospitalisation period. FI, CIRS-G and walking speed were separate, independent predictors of this adverse outcome of discharge destination (death, or move to higher level of residential care). This finding is in line with data on predictive power of frailty in general hospitals (Evans et al., Citation2014; Krishnan et al., Citation2014) and with the overall predictive value of multimorbidity, but not that of functional status (Miller & Weissert, Citation2000). As patients with BPSD were found to improve less on the CGI-I, they were also more prone to adverse discharge destination: ‘BPSD’ is one of the predictors of nursing home admission (Gaugler, Yu, Krichbaum, & Wyman, Citation2009; Toot, Swinson, Devine, Challis, & Orrell, Citation2017). Demographic variables as being single or divorced and living independently before admission also gave a higher odds ratio on adverse dicharge destination. These findings confirm the reliability of our predictive model.

According to our research question, we focussed on the separate predictive value of the geriatric variables and not on the complete multivariate model in this small population. The high correlations between the predictors would probably also have led to multicollinearity, which would have hampered the interpretation of the outcomes.

Implications and further research

Our findings mean that geriatric syndromes should not only be taken into account in discharge planning, but may also add in the overall treatment perspective of older patients with severe mental disorders.

We recommend screening for frailty, though our research was not aimed at finding the best screening tool. In line with our data, and for reasons of applicability, walking speed can be used, for example combined with the Clinical Frailty Scale, which is validated against the FI (Rockwood et al., Citation2005). Alternatively, multimorbidity may also be assessed by the CIRS-G. Such measures can be used in geriatric psychiatry populations to identify patients who can benefit from a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment (CGA). Future studies should compare screening methods for effectiveness, efficiency and feasibility.

These CGA’s should best be followed by complex care interventions in collaborative, interdisciplinary care models for older patients who have severe psychiatric disorders.

Collaborative care of psychiatric disorders and multimorbidity has been investigated in younger outpatients with depression, in which the depression as well as the somatic conditions and functional status improve significantly better in treatment than in control groups (Dham et al., Citation2017; Katon et al., Citation2010; Von Korff et al., Citation2011). The usefulness of a collaborative care model might be even more beneficial in older adults with severe mental disorders. However, in practice it both can be ‘too little and too late’, if it starts up only after admission to acute geriatric psychiatry wards, taking into account the high prevalence of geriatric syndromes at admission and the impact of frailty and multimorbidity on discharge destination.

Further research on complex care interventions with interdisciplinary, collaborative care models should include larger sample sizes, frailty or multimorbidity measures as targeting criteria, and best include quality of life or wellbeing as generally preferred outcomes by older people themselves.

Conclusion

The level of frailty and multimorbidity of the older patients admitted to acute geriatric psychiatric wards in our study is comparable to older patients admitted to general hospitals. Frailty, together with walking speed and multimorbidity may help to identify patients at risk for in hospital mortality, or move to higher level of residential care. Together these findings underline that geriatric syndromes, complementary to psychiatric diagnoses, matter in understanding the outcomes in geriatric psychiatry. Well-designed studies on complex care interventions, taking these geriatric syndromes into account, are urgently needed in older adults with severe psychiatric disorders.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (18.6 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.3 KB)References

- AGS. (1989). Public policy committee AGS comprehensive geriatric assessment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 37(5), 473–474.

- Andrew, M. K., & Rockwood, K. (2007). Psychiatric illness in relation to frailty in community-dwelling elderly people without dementia: A report from the Canadian study of health and aging. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue canadienne du vieillissement, 26(01), 33–38. doi: 10.1353/cja.2007.0026

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., Text Revision).

- Auslander, L. A., Lindamer, L. L., Delapena, J., Harless, K., Polichar, D., Patterson, T. L., … Jeste, D. V. (2001). A comparison of community-dwelling older schizophrenia patients by residential status. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 103(5), 380–386.

- Ballard, C., & Corbett, A. (2013). Agitation and aggression in people with Alzheimer’s disease. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 26(3), 252–259. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835f414b

- Benraad, C. E., Kamerman-Celie, F., van Munster, B. C., Oude Voshaar, R. C., Spijker, J., & Olde Rikkert, M. G. (2016). Geriatric characteristics in randomised controlled trials on antidepressant drugs for older adults: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(9), 990–1003. doi: 10.1002/gps.4443

- Berk, M., Ng, F., Dodd, S., Callaly, T., Campbell, S., Bernardo, M., & Trauer, T. (2008). The validity of the CGI severity and improvement scales as measures of clinical effectiveness suitable for routine clinical use. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 14(6), 979–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2007.00921.x

- Blodgett, J., Theou, O., Kirkland, S., Andreou, P., & Rockwood, K. (2015). Frailty in NHANES: Comparing the frailty index and phenotype. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 60(3), 464–470. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2015.01.016

- Bowie, C. R., Reichenberg, A., Patterson, T. L., Heaton, R. K., & Harvey, P. D. (2006). Determinants of real-world functional performance in schizophrenia subjects: Correlations with cognition, functional capacity, and symptoms. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(3), 418–425.

- Brodaty, H., & Arasaratnam, C. (2012). Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(9), 946–953.

- Brodaty, H., Draper, B. M., & Low, L. (2003). Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: A seven-tiered model of service delivery. Medical Journal of Australia, 178, 231–234.

- Bruce, M. L. (2001). Depression and disability in late life: Directions for future research. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 9(2), 102–112.

- Buigues, C., Padilla-Sanchez, C., Garrido, J. F., Navarro-Martinez, R., Ruiz-Ros, V., & Cauli, O. (2015). The relationship between depression and frailty syndrome: A systematic review. Aging and Mental Health, 19(9), 762–772. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2014.967174

- Busner, J., & Targum, S. D. (2007). The clinical global impressions scales: Applying a research tool in clinical practice. Psychiatry, 4(7), 28–37.

- Calati, R., Salvina Signorelli, M., Balestri, M., Marsano, A., De Ronchi, D., Aguglia, E., & Serretti, A. (2013). Antidepressants in elderly: Metaregression of double-blind, randomized clinical trials. J Affect Disord, 147(1–3), 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.11.053

- Clegg, A., Young, J., Iliffe, S., Olde Rikkert, M., & Rockwood, K. (2013). Frailty in elderly people. Lancet, 381(9868), 752–762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(12)62167-9

- Collard, R. M., Boter, H., Schoevers, R. A., & Oude Voshaar, R. C. (2012). Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: A systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(8), 1487–1492. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04054.x

- Collard, R. M., Comijs, H. C., Naarding, P., & Oude Voshaar, R. C. (2014). Physical frailty: Vulnerability of patients suffering from late-life depression. Aging and Mental Health, 18(5), 570–578. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.827628

- Collard, R. M., Comijs, H. C., Naarding, P., Penninx, B. W., Milaneschi, Y., Ferrucci, L., & Oude Voshaar, R. C. (2015). Frailty as a predictor of the incidence and course of depressed mood. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 16(6), 509–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2015.01.088

- Collin, C., Wade, F. T., Davies, S., & Horne, V. (1988). The Barthel ADL Index: A reliability study. International Disability Studies, 10(2), 61–63.

- Cuijpers, P., Vogelzangs, N., Twisk, J., Kleiboer, A., Li, J., & Penninx, B. W. (2014). Comprehensive meta-analysis of excess mortality in depression in the general community versus patients with specific ilnesses. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(4), 453–462.

- De Hert, M., Correll, C. U., Bobes, J., Cetkovich-Bakmas, M., Cohen, D., Asai, I., … Leucht, S. (2011). Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. 1. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparaties in health care. World Psychiatry, 10(1), 52–77.

- Desrosiers, J., Bravo, G., Hébert, R., & Dutil, E. (1995). Normative data for grip strength of elderly men and women. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 49(7), 637–644.

- Dham, P., Colman, S., Saperson, K., McAiney, C., Lourenco, L., Kates, N., & Rajji, T. K. (2017). Collaborative care for psychiatric disorders in older adults: A systematic review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(11), 761–771. doi: 10.1177/0706743717720869

- Dias, A., Teixeira-Lopes, F., Miranda, A., Alves, M., Narciso, M., Mieiro, L., … Gorjão-Clara, J. P. (2015). Comorbidity burden assessment in older people admitted to a Portuguese University Hospital. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 27(3), 323–328. doi: 10.1007/s40520-014-0280-5

- Evans, S. J., Sayers, M., Mitnitski, A., & Rockwood, K. (2014). The risk of adverse outcomes in hospitalized older patients in relation to a frailty index based on a comprehensive geriatric assessment. Age and Ageing, 43(1), 127–132. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft156

- Folstein, M., Folstein, S., & McHugh, P. (1975). “Mini mental state” a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12, 189–198.

- Fried, L. P., Tangen, C. M., Walston, J., Newman, A. B., Hirsch, C., Gottdiener, J., … McBurnie, M. A. (2001). Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 56(3), M146–M156.

- Gaugler, J. E., Yu, F., Krichbaum, K., & Wyman, J. F. (2009). Predictors of nursing home admission for persons with dementia. Medical Care, 47(2), 191–198.

- Gentile, S. (2010). Second-generation antipsychotics in dementia: Beyond safety concerns. A clinical, systematic review of efficacy data from randomised controlled trials. Psychopharmacology, 212(2), 119–129. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1939-z

- Gordon, E. H., Peel, N. M., Samanta, M., Theou, O., Howlett, S. E., & Hubbard, R. E. (2017). Sex differences in frailty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Experimental Gerontology, 89, 30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2016.12.021

- Guralnik, J. M., Fried, L. P., & Salive, M. E. (1996). Disability as a public health outcome in the aging population. Annual Review of public Health, 17, 25–46.

- Guy, W. (1976). Clinical global impressions. In W. Guy (Ed.), ECDEU assessment manual for psychopharmacology. (pp. 218–222). Rockville: US Department of Heath, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration.

- Haaksma, M. L., Vilela, L. R., Marengoni, A., Calderon-Larranaga, A., Leoutsakos, J. S., Olde Rikkert, M. G. M., & Melis, R. J. F. (2017). Comorbidity and progression of late onset Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review. PLoS One, 12(5), e0177044. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177044

- Harvey, P. D., & Bellack, A. S. (2009). Toward a terminology for functional recovery in schizophrenia: Is functional remission a viable concept? Schizophrenia Bulletin, 35(2), 300–306. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn171

- Inouye, S. K., Studenski, S., Tinetti, M. E., & Kuchel, G. A. (2007). Geriatric syndromes: Clinical, research and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 55(5), 780–791.

- Jacobs, A., Benraad, C., Wetzels, J., Olde Rikkert, M., & Kramers, C. (2017). Clinical relevance of differences in glomerular filtration rate estimations in frail older people by creatinine- vs. cystatin C-based formulae. Drugs & Aging, 34(6), 445–452.

- Kadouri, A., Corruble, E., & Falissard, B. (2007). The improved clinical global impression scale (iCGI): Development and validation in depression. BMC Psychiatry, 7(1), 7. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-7-7

- Kales, H. C., Gitlin, L. N., & Lyketsos, C. G. (2015). Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ, 350(mar02 7), h369. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h369

- Katon, W. J., Lin, E. H. B., Von Korff, M., Ciechanowski, P., Ludman, E. J., Young, B., … McCulloch, D. (2010). Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. The New England Journal of Medicine, 363(27), 2611–2620.

- Krishnan, M., Beck, S., Havelock, W., Eeles, E., Hubbard, R. E., & Johansen, A. (2014). Predicting outcome after hip fracture: Using a frailty index to integrate comprehensive geriatric assessment results. Age and Ageing, 43(1), 122–126. doi: 10.1093/ageing/aft084

- Lala, S. V., & Sajatovic, M. (2012). Medical and psychiatric comorbidities among elderly individuals with bipolar disorder: A literature review. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 25(1), 20–25. doi: 10.1177/0891988712436683

- Lenze, E., Rogers, J., Martire, L., Mulsant, B., Rollman, B., Dew, M., … Reynolds, C. (2001). The association of late-life depression and anxiety with physical disability. A review of the literature and prospectus for future reseach. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 9(2), 113–135.

- Miller, E. A., & Weissert, W. G. (2000). Predicting elderly people's risk for nursing home placement, hospitalisation, functional impairment, and mortality: A synthesis. Medical Care Research and Review, 57(3), 259–297.

- Miller, M. D., Paradis, C. F., Houck, P. R., Mazumdar, S., Stack, J. A., Rifai, A. H., … Reynolds, C. F. (1992). Rating chronic medical illness burden in geropsychiatric practice and research: Application of the cumulative illness rating scale. Psychiatry Research, 41(3), 237–248.

- Mitnitski, A. B., Graham, J. E., Mogilner, A. J., & Rockwood, K. (2002). Frailty, fitness and late-life mortality in relation to chronological and biological age. BMC Geriatrics, 2(1), 1

- Oosterveld, S. M., Kessels, R. P. C., Hamel, R., Ramakers, I. H. G. B., Aalten, P., Verhey, F. R. J., … Melis, R. J. F. (2014). The influence of co-morbidity and frailty on the clinical manifestation of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 42(2), 501–509. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140138

- Partridge, J. S., Harari, D., & Dhesi, J. K. (2012). Frailty in the older surgical patient: A review. Age and Ageing, 41(2), 142–147. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afr182

- Penninx, B. W. J. H., Milaneschi, Y., Lamers, F., & Vogelzangs, N. (2013). Understanding the somatic consequences of depression: Biological mechanisms and the role of depression symptom profile. BMC Medicine, 11(1), 129.

- Pinna, F., Deriu, L., Diana, E., Perra, V., Randaccio, R., Sanna, L., … Carpiniello, B. (2015). Clinical global impression-severity score as a reliable measure for routine evaluation of remission in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorders. Annals of General Psychiatry, 14(1), 6. doi: 10.1186/s12991-015-0042-6

- Podsiadlo, D., & Richardson, S. (1991). The timed ‘‘Up & Go’’: A test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 39(2), 142–148.

- Ritt, M., Ritt, J., Sieber, C., & Gaßmann, K. (2017). Comparing the predictive accuracy of frailty, comorbidity, and disability for mortality: A 1-year follow-up in patients hospitalized in geriatric wards. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 12, 293–304. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S124342

- Robertson, D. A., Savva, G. M., & Kenny, R. A. (2013). Frailty and cognitive impairment–A review of the evidence and causal mechanisms. Ageing Research Reviews, 12(4), 840–851. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2013.06.004

- Rockwood, K. (2005). What would make a definition of frailty successful?. Age and Ageing, 34(5), 432–434. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afi146

- Rockwood, K., Howlett, S. E., MacKnight, C., Beattie, B. L., Bergman, H., Hébert, R., … McDowell, I. (2004). Prevalence, attributes, and outcomes of fitness and frailty in community-dwelling older adults: Report from the Canadian study of health and aging. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A, 59(12), 1310–1317.

- Rockwood, K., & Mitnitski, A. (2006). Limits to deficit accumulation in elderly people. Mechanisms of Ageing and Development, 127(5), 494–496. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2006.01.002

- Rockwood, K., & Mitnitski, A. (2007). Frailty in relation to the accumulation of deficits. Journal of Gerontology Medical Sciences, 62(7), 722–727.

- Rockwood, K., Song, X., MacKnight, C., Bergman, H., Hogan, D. B., McDowell, I., & Mitnitski, A. (2005). A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. CMAJ, 173(5), 489–495. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050051

- Rubenstein, L. Z., Harker, J. O., Salvà, A., Guigoz, Y., & Vellas, B. (2001). Screening for undernutrition in geriatric practice: Developing the short-form mini-nutritional assessment (MNA-SF). Journal of Gerontology A Biological Medical Sciences, 56A(6), M366–M372.

- Sanchez-Moreno, J., Martinez-Aran, A., Tabares-Seisdedos, R., Torrent, C., Vieta, E., & Ayuso-Mateos, J. L. (2009). Functioning and disability in bipolar disorder: An extensive review. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78(5), 285–297. doi: 10.1159/000228249

- Searle, S. D., Mitnitski, A., Gahbauer, E. A., Gill, T. M., & Rockwood, K. (2008). A standard procedure for creating a frailty index. BMC Geriatrics, 8(1), 24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-8-24

- Song, X., Mitnitski, A., & Rockwood, K. (2010). Prevalence and 10-year outcomes of frailty in older adults in relation to deficit accumulation. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 58(4), 681–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02764.x

- Soysal, P., Veronese, N., Thompson, T., Kahl, K. G., Fernandes, B. S., Prina, A. M., … Stubbs, B. (2017). Relationship between depression and frailty in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Research Reviews, 36, 78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2017.03.005

- Spearing, M. K., Post, R. M., Leverich, G. S., Brandt, D., & Nolen, W. (1997). Modification of the clinical global impressions (CGI) scale for use in bipolar illness (BP): The CGI-BP. Psychiatry Research, 73(3), 159–171.

- Spielmans, G. I., & McFall, J. P. (2006). A comparative meta-analysis of clinical global impressions change in antidepressant trials. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 194(11), 845–852. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000244554.91259.27

- Studenski, S., Perera, S., Patel, K., Rosano, C., Faulkner, K., Inzitari, M., … Guralnik, J. (2011). Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA, 305(1), 50–58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1923

- Targum, S. D., Busner, J., & Dunn, J. (2008). Confounding influence of extraneous symptoms on clinical global impression ratings for depression. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology, 28(5), 587–589.

- Targum, S. D., Busner, J., & Young, A. H. (2008). Targeted scoring criteria reduce variance in global impressions. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 23(7), 629–633. doi: 10.1002/hup.966

- Tedeschini, E., Levkovitz, Y., Iovieno, N., Ameral, V. E., Nelson, J. C., & Papakostas, G. I. (2011). Efficacy of antidepressants for late-life depression: A meta-analysis and meta-regression of placebo-controlled randomized trials. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 72(12), 1660–1668. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10r06531

- Theou, O., Rockwood, M. R., Mitnitski, A., & Rockwood, K. (2012). Disability and co-morbidity in relation to frailty: How much do they overlap? Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 55(2), e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2012.03.001

- Tinetti, M. E. (1986). Performance-orientated assessment of mobility problems in elderly patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 34(2), 119–126.

- Toot, S., Swinson, T., Devine, M., Challis, D., & Orrell, M. (2017). Causes of nursing home placement for older people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(02), 195–208. doi: 10.1017/S1041610216001654

- Vaughan, L., Corbin, A. L., & Goveas, J. S. (2015). Depression and frailty in later life: A systematic review. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 10, 1947–1958. doi: 10.2147/CIA.S69632

- Von Korff, M., Katon, W. J., Lin, E. H. B., Ciechanowski, P., Peterson, D., Ludman, E. J., … Rutter, C. M. (2011). Functional outcomes of multi-condition collaborative care and successful ageing: Results of randomised trial. BMJ, 343(nov10 1), d6612. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d6612

- Walker, E. R., McGee, R. E., & Druss, B. G. (2015). Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(4), 334–341. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502