Abstract

Objectives: Depressive symptoms in the elderly have been shown to be associated with increased mortality. The purpose of this study was to examine symptoms of depression in octogenarian men and their association with all-cause mortality, and whether physical, cognitive and social factors influence this association.

Methods: Out of the 703 initially included 55-years-old men, from the prospective cohort study “Men born in 1914”, we studied 163 survivors who could take a part in a survey at age 81, and followed them until their death.

Results: Those men who had at least mild depressive symptoms, defined with Zung Self-rating Depression Scale, were found to have an increased mortality risk (HR = 1.52; CI =1.10–2.08; p = 0.01). This association persisted significantly after adjusting for: education, global cognition at age 81, cognitive abilities at age 68, vascular risk factors and comorbidities. Instead, it was attenuated after adjustments for Activities of Daily Life (ADL) – dependency and for a grade of Satisfaction with Participation in daily life.

Conclusion: In octogenarian men with survival above the average, mild depressive symptoms predict all-cause mortality. Neither cognitive capacity nor vascular comorbidity explained this association, but lower Satisfaction with Participation in daily life, especially in combination with moderate ADL-dependency.

Introduction

Late-life depression is associated with cognitive impairment and chronic medical illness, and leads to suffering, disability and worsens outcome of other medical illnesses (Alexopoulos et al., Citation2002; Alexopoulos, Citation2005; Bruce, Seeman, Merrill, & Blazer, Citation1994). It also increases mortality by different social, mental and physical factors (Almeida, Alfonso, Hankey, & Flicker, Citation2010; Almeida et al., Citation2015; Burns et al., Citation2015; Köhler et al., Citation2013). Even though the prevalence of major depression in the elderly is lower, the prevalence of subclinical depression is increasing. Symptoms of late-life depression also differ from those in younger adults (Alexopoulos, Citation2005) and include somatic symptoms, like constipation, weight loss and feeling of dependence, as included in the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) and Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (ZSDS).

Different hypotheses have been formulated to explain the atypical spectra of depression in the elderly. The ”vascular depression hypothesis” postulates that cerebrovascular disease may predispose, precipitate and/or perpetuate some geriatric depressive syndromes (Alexopoulos et al., Citation1997; Taylor, Aizenstein, & Alexopoulos, Citation2013) by mechanisms of disconnection, in which ischaemic damage disrupts cerebral circuits, inflammation, in which increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines induce fatigue and mood reduction, and of hypoperfusion, in which disruption of cerebrovascular autoregulation has an adverse effect on cognitive and affective processes. Previous studies failed to reach a consensus regarding the covariates of the depression-mortality association. It could be mediated fully via somatic comorbidity (André-Petersson et al., Citation2003), or explained by frailty, disability and decreased heart rate variability (Almeida et al., Citation2010, Citation2015; Bruce et al., Citation1994; Glassman, Bigger, Gaffney, & Van Zyl, Citation2007; Nicolini, Ciulla, Asmundis, Magrini, & Brugada, Citation2012). Frailty, defined as decreased physiological reserve capacity, has also been associated with more severe depressive symptoms in aging, as well as with increased all-cause mortality (Almeida et al., Citation2015; Collard, Comijs, Naarding, & Oude Voshaar, Citation2014). The concept of participation in social and daily activities has recently emerged in studies concerning elderly people’s health and well-being. Defined as involvement in a life situation, including accomplishment of daily activities and social roles, satisfaction with participation in daily life has been acknowledged by the WHO as a key indicator of human health and well-being. Spanning over both dependency in activities of daily life (ADL) and emotional well-being, a growing number of studies indicates a satisfaction with participation as a key concept in measuring elderly people’s general and mental health (Croezen, Avendano, Burdorf, & van Lenthe, Citation2015; Silva, Cesse, & Albuquerque, Citation2014; Sundquist, Lindström, Malmström, Johansson, & Sundquist, Citation2004). Gender seems to have an impact on the relationship between mortality and late-life depression as well. Although depression is more prevalent in elderly women, most studies have found depression to be more significantly associated to mortality in men (Diniz et al., Citation2014; Sun et al., Citation2011). Elderly men have also a 14-fold increased risk of committing suicide compared to women (National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Citation2010).

These observations offer a plausible explanations to the link between mortality and depression, but there are still no coherent explanatory theories and not enough evidence supporting any of the proposed mechanisms. The purpose of this study was to examine depressive symptoms in octogenarian men and their association with all-cause mortality, and whether physical, cognitive and social factors influence this association. The null hypothesis was that the depression-scores were not related to the survival.

Methods

Study sample

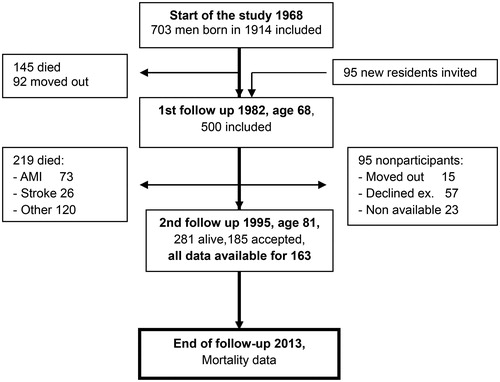

A prospective population sample study “Men born in 1914” has been in progress since 1968. It included all men born in the even months of 1914 in the city of Malmö, Sweden (). Of the total of 809 men invited, 703 men took part in the first health examination. In 1982, 465 men from the cohort at age 68 and additionally 95 new residents were invited to a new examination. Five hundred of them agreed to participate. The collected data included estimation of ankle-brachial pressure index (ABI), sociodemographic data and medical history, amongst others. Five tests of cognitive ability were performed by a clinical neuropsychologist, and included: Synonyms, a test of verbal ability; Block Design, a test of visuospatial and constructive ability; Paired Associates, a test of verbal, immediate memory; Digit Symbol Substitution Test, a test measuring psychomotor speed, visual-motor coordination, concentration and cognitive flexibility; and Benton Visual Retention Test (BVRT), a test of immediate visual, spatial memory. For further explanation of the various tests performed, we refer to previous methodological description (André-Petersson et al., Citation2003).

The most recent survey started in 1995, and 281 men at age 81 were found to still be alive. Of these, 185 agreed to take part (66%) in both physical and psychological examinations. Data concerning ZSDS-scores, ADL, Satisfaction with Participation, cognitive status measured with Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), and concerning vascular comorbidity were available from 163 subjects, and these men were defined as a study group. Our cohort was followed-up until 2013, when the last subject still residing in Malmö died. Dates of death were available from the Local Mortality Register. The ethics committee at Lund University approved the study, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Zung Self-Rating depression scale

The ZSDS was applied by a research neuropsychologist to survey depressive symptoms. The ZSDS consists of 20 items using a four-point grading system, ranging from “none, or a little of the time” to “most of, or all the time” (Appendix 1). The ZSDS does not express the severity of depression accurately, but is a sensitive tool to detect clinical depression in the elderly, and the results are explained by cognitive deficits only to a lesser extent (Zung, Richardy, & Short, Citation1965). In the group studied, the ZSDS score ranged from 21 to 57 (mean: 35.47, SD: 6.37, median 35.9; Skewness 0.622, SE 0.188; Kurtosis 0.570, SE 0.374). The study group was divided into two groups according to the mean ZSDS value of the cohort: one subgroup with ZSDS scores of 36 or lower, and one with scores above 36.

Comorbidity

Current prescriptions were reported by the participants themselves. We used four markers of vascular health status in the statistical analysis: congestive heart failure (CHF), previous stroke, previous myocardial infarction (MI) and ankle-brachial index (ABI) less than 1.0. Data on these and other diagnoses were either reported by the participants themselves or based on their current medications. ABI was measured at the Department of Clinical Physiology, University Hospital in Malmö.

ADL-questionnaire

A total of 36 questions regarding dependency in everyday-life activities were included in the original questionnaire (Appendix 2). We selected 12 of these to be used in the statistical analysis. The variables were dichotomized into either an” independent”, or a” dependent” group. Independency was defined as a full autonomy, and dependency as requiring the aid of tools or persons.

Satisfaction with participation in daily life

Four questions regarding satisfaction with participation were asked when participants were 81 years of age, and included in the analysis (Appendix 2). Each answer was graded from 1 to 4, with higher points indicating higher satisfaction.

Statistical analyses

In order to incorporate the data concerning ADL, Satisfaction with Participation and cognitive ability at age 68 into the survival analyses, we used composite variables. Each ADL-item was dichotomized indicating a dependant or an independent value (Appendix 2). Basing on that, we defined a variable indicating independency in all 12 ADL-items or dependency in one or more of the 12 items. To define Satisfaction with Participation at age 81, we summarized scores from each of the four questions presented in Appendix 2. Low Satisfaction with Participation was defined as a summarized composite score of below the median value of the whole cohort. Concerning cognitive ability at age 68, we standardized each of the five cognitive test variables into Z-scores using the mean score of the whole cohort (N = 463) as reference. We then calculated the mean Z-scores of each cognitive test into a composite variable.

Univariate Cox Regression for all-cause mortality and single independent variables used in the main analysis was performed (Appendix 3). Eight sets of baseline covariates were used in the adjusted models to determine background of the association between mortality and depressive symptoms. Model 1 adjusted for education and MMSE-scores at age 81; Model 2 adjusted for education and for cognition at age 68; Model 3 adjusted for vascular comorbidity at age 81 (history of CHF, stroke, MI and ABI < 1.0); Model 4 adjusted for ADL-dependency; Model 5 adjusted for vascular comorbidity and ADL-dependency; Model 6 adjusted for Satisfaction with Participation; Model 7 adjusted for ADL-dependency and Satisfaction with Participation; and model 8 adjusted for the number of medications. There was no multicollinearity between predictor variables when calculated separately for each model (tolerance values >0.8; Variance Inflation Factors <1.4).

Values are expressed as means ± standard deviation. The relationship between variables was calculated with the chi-squared test. The t-test for independent samples was used to analyse differences for normally distributed data, and the Mann-Whitney U-test was used for non-normally distributed data. A 2-tailed p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Cox proportional hazards model was used to calculate mortality hazard rates.

All data analyses and statistical calculations were performed using the SPSS v. 22 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) data package.

Results

Mean survival after the last examination in 1995 (age 81 years), was 101.5 months (95% CI = 93.8–109.2, range 6–207). When stratified by ZSDS-score, mean survival for the low-scoring group was 109.6 months (CI = 99.9–119.2, range: 17–207) and for the high-scoring group, 88.5 months (CI = 76.4–100.56, range: 6–196). Descriptive data of the total cohort of the study and after stratification by ZSDS-score are presented in . The high ZSDS-scoring group had: higher prevalence of CHF and previous stroke, higher median number of daily medications, and higher prevalence of ADL-dependency and of low mean Satisfaction with Participation. There were no significant differences between the high and low-ZSDS score group regarding education or cognition at 68 or 81.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the total study group (left column), and analyses of relationship between two subgroups stratified by ZSDS-scores, above and below 36 points.

presents results from the proportional hazards models testing the study hypothesis. We observed an association between belonging to the subgroup with high ZSDS-scores and decreased survival in an unadjusted model (HR = 1.52, CI = 1.10–2.08, p = 0.010). Adjusting for education and cognition in models 1 and 2 yields no change in significance for ZSDS-score-impact on survival. Adjusting for vascular comorbidity in model 3 diminishes the association slightly, but statistical significance remains. When adjusting for ADL-dependency in model 4, the association between ZSDS-scores and survival decreases to borderline values of significance. The association becomes non-significant after adjusting for ADL-dependency and vascular comorbidity in combination (model 5), after adjusting for Satisfaction with Participation (model 6), after adjusting for ADL-dependency and Satisfaction with Participation in combination (model 7), and after adjusting for a number of medications (model 8).

Table 2. Hazard ratios (95%CI) for all-cause mortality in a cohort of men, age 81, with high depression scale scores, both in a crude and in the adjusted models.

To further examine the connection between depressive symptoms and the strongest covariate, Satisfaction with Participation, we made a post-hoc analysis. Using a bivariate correlational analysis, we observed an association between Satisfaction with Participation and the second strongest covariate, number of medications (r = 0.20, p = 0.009). Low Satisfaction with Participation was also associated with lower scores of ABI, the variable that showed highest hazard ratio in the multivariate models (Mann-Whitney U-test, Z = −2.84, p = 0.005).

Discussion

Elderly men with mild depressive symptoms, defined as a ZSDS-score of above 36, were found to have an increased risk of all-cause mortality. This association was attenuated by adjustments for ADL-dependency, number of medications and Satisfaction with Participation in Daily Life. Global cognition at age 81 and cognitive capacity at age 68 had no confounding effect. Vascular comorbidities, being significant mortality factors themselves, did not affect this association significantly. However, Satisfaction with Participation was associated with ankle brachial index (ABI) and with a number of medications. These results suggest a complex relationship between depression and mortality, with several possible potential explanatory factors, but also a potential for reverse causation and confounding effects.

Due to the means of recruitment, our study group comprises healthy, elderly individuals: mean age of death was 89 years (101.5 months after last follow up). The majority of the original cohort died before the follow-up at age 81, while sick or hospitalized individuals were not able to attend the last follow up. We could observe a drop-out already at the survey in 1985 (Janzon et al., Citation1986). In the drop-out group, there was an overrepresentation of single men, of men depending on social welfare, from an area of the city with a higher unemployment rate and a higher share of single person households and households with a larger utilisation of social welfare, and non-married men. Social assistance act and/or law on temperance had been applied to more of the non-attenders than of the attenders, and the percentage of men who had been in contact with the Department of Alcohol Diseases in local hospital was about three times greater among non-attenders. Other differences were: a negative attitude towards health surveys and rating subjectively their health as poor. Of the non-attenders 25%, and of the attenders 12% had been hospitalised during last 12 months before the survey at 1985. Hence, due to a degree of healthy user-bias affecting our sample, our subjects represent a community-based population of relatively healthy octogenarians. That could explain why very few reached ZSDS-scores indicating an actual, clinical depression (Roh et al., Citation2015). Therefore, a cut-off at 36 points indicates depressive symptoms or a subsyndromal depression, rather than clinical diagnosis. Nevertheless, even with such a low cut-off, there is still a significant and strong correlation with mortality.

Our study group is also characterized by a high global cognition and cognitive capacity, compared to the rest of the original cohort. Previous studies have shown a strong correlation between cognitive impairment and depressive symptoms, as well as an additive effect on mortality (Mehta et al., Citation2003; Rapp et al., Citation2011; van den Kommer et al., Citation2013). Healthy user-bias could partly explain the absence of such an association in our study, as well as the fact that MMSE is a crude tool for detecting mild cognitive defects. According to the theory of vascular depression, cognitive decline and affective disorders could in the elderly be a part of the same underlying pathological mechanisms (Alexopoulos et al., Citation1997; Taylor et al., Citation2013). Our results do not support this observation in the oldest old, since cognitive function at neither the age of 68 nor 81 had any correlation with mortality or depressive symptoms.

As expected, some comorbidities were more frequent in the high-ZSDS group (CHF and Stroke), and subjects with low ABI had highest mortality risk. However, after adjusting for these factors, the impact of high ZSDS-scores on the risk of death was not significantly affected. Previous studies showed an increased risk of both fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events in elderly patients with depression (Whooley & Browner, Citation1998; Peters et al., Citation2010). However, our results indicate that emotional state has not an explanatory effect on increased mortality in elderly patients with depressive symptoms. We have additionally, although not presented in the results, adjusted for diabetes, cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and hypertension in the proportional hazard model, and none of these potential confounders affected the depression-mortality association. Diabetes and hypertension, being risk factors rather than markers of vascular disease, have a smaller impact on a survival in an octogenarian population, which could explain negative results. Previous research also showed a complex and paradoxical relationship between hypertension and depressive symptoms (Siennicki-Lantz, André-Petersson, & Elmståhl, Citation2013). It suggest that in eighth decade rather consequences of vascular risk factors, like CHF or stroke, than the risk factors themselves, might affect emotional status. However, the impact on mortality is not noticeable until the social factors are affected.

Even though our participants would nowadays be considered to have a low number of daily medications, subjects with high ZSDS-scores had double number of medications and it affected risk of death. As multimorbidity naturally increases the number of medications taken, the latter could express a general burden of the diseases. Since neither vascular nor general morbidity affected mortality, this would imply that polypharmacy in itself might be associated with depressive symptoms and a risk of death in the elderly. We have previously showed that using hypnotics and sedatives was twice as high in high ZSDS score as in low score subgroup (Siennicki-Lantz, André-Petersson, & Elmståhl, Citation2013), indicating an axis between the grade of emotional burden, polypharmacy, social health and mortality.

Low Satisfaction with Participation in Daily Life was the strongest covariate with depressive symptoms and risk of death. In regard to the questions used in our study and the manner in which they were formulated, one could argue that they might act as a proxy for depression itself, yielding the strong correlations seen in the results. However, previous studies have also observed a correlation between low satisfaction with participation, depression and earlier death, especially due to cardiovascular disease (Croezen et al., Citation2015; Silva et al., Citation2014; Sundquist et al., Citation2004). In concurrence with these results, we showed that subjects with low satisfaction with participation had lower ABI. It might indicate that Satisfaction with Participation acts as a reflector not only of a grade of mental ill-health but also of vascular burden and, together with ADL dependency, being strongest associated with death risk. Future research should focus on whether asking about satisfaction with participation in various aspects of everyday life could be used to identify individuals with veiled depressivity, polypharmacy, high vascular burden, ADL dependency and at risk of earlier death.

Our study group had generally a low grade ADL-dependency. Although 68 (37.1%) subjects were defined as dependent, 38 of them were dependent in only one ADL-item. For 14 of these, the sole item was:” unable to walk briskly for 5 minutes”. Nonetheless, adjusting for ADL-dependency in Cox regression-models showed a decrease of significance for ZSDS-scores, indicating an interconnected relationship between ADL-dependency, depressive symptoms and mortality. Indeed, previous studies have highlighted the relationship between disability and depression (Alexopoulos et al., Citation2002; Bruce et al., Citation1994; Mehta, Yaffe, & Covinsky, Citation2002). Depression has been shown as a risk factor for developing ADL-dependency in previously independent subjects (Mehta et al., Citation2002). Therefore, we hypothesize that even slight ADL-dependency in octogenarians could have an explanatory role of mortality in depressed individuals (Millán-Calenti, et al., Citation2010; Jakobsson & Karlsson, Citation2011. We suggest that future research should focus on clarifying the causal and temporal relationship between depressive symptoms and the development of ADL-dependency.

According to the previous research, ADL-dependency and frailty overlap greatly. Although not measured directly, our results could indicate some degree of frailty in our study group. While usually being defined by only physical criteria, broader definitions of frailty include psychiatric symptoms as well as somatic ones (Collard, Boter, Schoevers, & Oude Voshaar, Citation2012; Collard & Oude, Citation2012). Previous studies have found correlation between frailty and depression in elderly subjects, as well as a synergistic effect of frailty and depression on mortality (Almeida et al., Citation2015; Buigues et al., Citation2015; Collard, Comijs, Naarding, & Oude Voshaar, Citation2014). These observations and our results as well might be possibly explained by the fact that frailty exerts an effect not only on somatic systems but also on affective and cognitive systems. Increased frailty could therefore shift the framework of both somatic, cognitive and emotional processes, yielding a spiralling decline in all.

The strengths of our study include: a well-documented sample, lack of age and gender bias and a high-quality longitudinal follow-up. The medical examination was performed by an experienced geriatrician, and the psychological interview by a clinical neuropsychologist. Amongst the limitations is the small sample which was due to missing data for some participants at the different follow-ups, and the underrepresentation of the institutionalized elderly and those with cognitive decline. At the last follow-up in 1995, there was an absence of standardized questionnaires measuring satisfaction with participation in daily life. Until today, several standardized questionnaires used to measure participation have been developed (PARTS/M, PROMIS, SATIS-Stroke). Several questions regarding satisfaction with participation were nevertheless included in the general health-questionnaire, which is why these were used to give a crude measure of satisfaction. Regarding ADL, the questions used are today included in a standardized questionnaire such as the Katz’ ADL-index to measure both basic and instrumental ADL. Furthermore, assessing the elderly using questionnaires and interviews can be associated with difficulties in remembering symptoms, or in recounting for questions regarding emotional health truthfully.

Conclusion: In this cohort of octogenarian men with survival above the average, mild depressive symptoms predict all-cause mortality. Neither cognitive capacity nor vascular comorbidity had major impact on this association. Instead, multiple medications and especially lower satisfaction with participation in daily life, in combination with moderate ADL-dependency, strongest attenuated the association between depressivity and mortality. Asking very elderly about a satisfaction with participation in various aspects of everyday life might not only reflect a grade of mental ill-health, but also of vascular burden and, together with ADL dependency, could help to identify individuals at risk for earlier death.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexopoulos, G. S. (2005). Depression in the elderly. Lancet (London, England), 365(9475), 1961–1970.

- Alexopoulos, G. S., Buckwalter, K., Olin, J., Martinez, R., Wainscott, C., & Krishnan, K. R. R. (2002). Comorbidity of late life depression: An opportunity for research on mechanisms and treatment. Biological Psychiatry, 52(6), 543–558.

- Alexopoulos, G. S., Meyers, B. S., Young, R. C., Campbell, S., Silbersweig, D., & Charlson, M. (1997). ‘Vascular depression’ hypothesis. Archives of General Psychiatry, 54(10), 915–922.

- Almeida, O. P., Alfonso, H., Hankey, G. J., & Flicker, L. (2010). Depression, antidepressant use and mortality in later life: The Health In Men Study. PLoS One, 5(6), e11266

- Almeida, O. P., Hankey, G. J., Yeap, B. B., Golledge, J., Norman, P. E., & Flicker, L. (2015). Depression, frailty, and all-cause mortality: A cohort study of men older than 75 years. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 16(4), 296–300.

- André-Petersson, L., Elmståhl, S., Hagberg, B., Janzon, L., Reinprecht, F., & Steen, G. (2003). Is blood pressure at 68 an independent predictor of cognitive decline at 81? Results from follow-up study ‘Men born in 1914’, Malmö, Sweden. Aging & Mental Health, 7(1), 61–72.

- Bruce, M. L., Seeman, T. E., Merrill, S. S., & Blazer, D. G. (1994). The impact of depressive symptomatology on physical disability: MacArthur studies of successful aging. American Journal of Public Health, 84(11), 1796–1799.

- Buigues, C., Padilla-Sánchez, C., Fernández Garrido, J., Martínez, R. N., Ros, V. R., & Cauli, O. (2015). The relationship between depression and frailty syndrome: A systematic review. Aging & Mental Health, 19(9), 762–772.

- Burns, R. A., Butterworth, P., Browning, C., Byles, J., Luszcz, M., Mitchell, P., … Anstey, K. J. (2015). Examination of the association between mental health, morbidity, and mortality in late life: Findings from longitudinal community surveys. International Psychogeriatrics, 27(5), 739–746.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2010). Web-based injury statistics query and reporting system (WISQARS). National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/injury/wisqars/

- Collard, R. M., Boter, H., Schoevers, R. A., & Oude Voshaar, R. C. (2012). Prevalence of frailty in community-dwelling older persons: A systematic review. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(8), 1487–1492.

- Collard, R. M., Comijs, H. C., Naarding, P., & Oude Voshaar, R. C. (2014). Physical frailty: Vulnerability of patients suffering from late-life depression. Aging & Mental Health, 18(5), 570–578.

- Collard, R. M., & Oude, V. R. (2012). [Frailty; a fragile concept]. Tijdschrift voor Psychiatrie, 54(1), 59–69.

- Croezen, S., Avendano, M., Burdorf, A., & van Lenthe, F. J. (2015). Social participation and depression in old age: A fixed-effects analysis in 10 European countries. American Journal of Epidemiology, 182(2), 168–176.

- Diniz, B. S., Reynolds, C. F., Butters, M. A., Dew, M. A., Firmo, J. O., Lima-Costa, M. F., & Castro-Costa, E. (2014). satisfaction with participation in various aspects of everyday life might not only reflect a grade of mental ill-health, but also of vascular burden and, together with ADL dependency, could help to identify individuals with at risk for earlier death. Depression and Anxiety, 31(9), 787–795.

- Glassman, A. H., Bigger, J. T., Gaffney, M., & Van Zyl, L. T. (2007). Heart rate variability in acute coronary syndrome patients with major depression: Influence of sertraline and mood improvement. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(9), 1025–1031.

- Jakobsson, U., & Karlsson, S. (2011). Predicting mortality with the ADL-staircase in frail elderly. Physical & Occupational Therapy in Geriatrics, 29(2), 136–147.

- Janzon, L., Hanson, B. S., Isacsson, S. O., Lindell, S. E., & Steen, B. (1986). Factors influencing participation in health surveys. Results from prospective population study ‘Men born in 1914’ in Malmö, Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health, 40(2), 174–177.

- van den Kommer, T. N., Comijs, H. C., Aartsen, M. J., Huisman, M., Deeg, D. J., & Beekman, A. T. (2013). Depression and cognition: How do they interrelate in old age? The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(4), 398–410.

- Köhler, S., Verhey, F., Weyerer, S., Wiese, B., Heser, K., Wagner, M., … Maier, W. (2013). Depression, non-fatal stroke and all-cause mortality in old age: A prospective cohort study of primary care patients. Journal of Affective Disorders, 150(1), 63–69.

- Mehta, K. M., Yaffe, K., & Covinsky, K. E. (2002). Cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and functional decline in older people. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 50(6), 1045–1050.

- Mehta, K. M., Yaffe, K., Langa, K. M., Sands, L., Whooley, M. A., & Covinsky, K. E. (2003). Additive effects of cognitive function and depressive symptoms on mortality in elderly community-living adults. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 58(5), M461–M467.

- Millán-Calenti, J. C., Tubío, J., Pita-Fernández, S., González-Abraldes, I., Lorenzo, T., Fernández-Arruty, T., & Maseda, A. (2010). Prevalence of functional disability in activities of daily living (ADL), instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) and associated factors, as predictors of morbidity and mortality. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 50(3), 306–310.

- Nicolini, P., Ciulla, M. M., Asmundis, C. D., Magrini, F., & Brugada, P. (2012). The prognostic value of heart rate variability in the elderly, changing the perspective: From sympathovagal balance to chaos theory. Pacing and Clinical Electrophysiology, 35(5), 621–637.

- Peters, R., Pinto, E., Beckett, N., Swift, C., Potter, J., McCormack, T., … Bulpitt, C. (2010). Association of depression with subsequent mortality, cardiovascular morbidity and incident dementia in people aged 80 and over and suffering from hypertension. Data from the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET). Age and Ageing, 39(4), 439–445.

- Rapp, M. A., Schnaider-Beeri, M., Wysocki, M., Guerrero-Berroa, E., Grossman, H. T., Heinz, A., & Haroutunian, V. (2011). Cognitive decline in patients with dementia as a function of depression. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 19(4), 357–363.

- Roh, H. W., Hong, C. H., Lee, Y., Oh, B. H., Lee, K. S., Chang, K., & Son, S. J. (2015). participation in physical, social, and religious activity and risk of depression in the elderly: A community-based three-year longitudinal study in Korea. PLoS One, 10(7), e0132838.

- Siennicki-Lantz, A., André-Petersson, L., & Elmståhl, S. (2013). Decreasing blood pressure over time is the strongest predictor of depressive symptoms in octogenarian men. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(9), 863–871.

- Silva, V. D. L., Cesse, E. Â. P., & Albuquerque, M. D. F. P. M. (2014). Social determinants of death among the elderly: A systematic literature review. Revista Brasileira de Epidemiologia, 17(suppl 2), 178–193.

- Sundquist, K., Lindström, M., Malmström, M., Johansson, S. E., & Sundquist, J. (2004). Social participation and coronary heart disease: A follow-up study of 6900 women and men in Sweden. Social Science & Medicine, 58(3), 615–622.

- Sun, W., Schooling, C. M., Chan, W. M., Ho, K. S., & Lam, T. H. (2011). The association between depressive symptoms and mortality among Chinese elderly: A Hong Kong cohort study. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 66(4), 459–466.

- Taylor, W. D., Aizenstein, H. J., & Alexopoulos, G. S. (2013). The vascular depression hypothesis: Mechanisms linking vascular disease with depression. Molecular Psychiatry, 18(9), 963–974.

- Whooley, M. A., & Browner, W. S. (1998). Association between depressive symptoms and mortality in older women. Archives of Internal Medicine, 158(19), 2129–2135.

- Zung, W. W. K., Richardy, C. B., & Short, M. J. (1965). Self-rating depression scale in an outpatient clinic. Archives of General Psychiatry, 13(6), 508–518.

Appendixes

Appendix 1. The Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale includes 20 items which describe the pervasive effect, the psychological equivalents, other disturbances, and psychomotor activities. It includes ten positively worded and ten negatively worded questions, each scored on a scale of 1–4. The score range from 25 to 100 (Zung, Richardy, & Short, Citation1965).

For each item below, please check the column which best describes how often you felt or behaved this way during the past several days.

Appendix 2. Activities of daily life (ADL) and satisfaction with participation variables

Appendix 3. Univariate cox regression for all-cause mortality and single independent variables used in the main analysis