Abstract

Objectives: Research evidence has demonstrated disparities and barriers associated with mental illness, which creates challenges for individuals with mental illness to maintain physical, mental, and social health as they age. The aim of this study was to examine the meaning of aging from the perspective of individuals with mental illness and explore their motivations and challenges to adopting healthy aging lifestyles and practices.

Method: Using a qualitative narrative inquiry approach, interviews were conducted with 61 aging patients with mental illness aged 40 and older in community and institutional settings in Hong Kong.

Results: Participants discussed the meaning of healthy aging in terms of meaningful occupation and use of time, and independence and autonomy. Motivating factors included a desire to avoid ‘burdening’ other people, to ‘give back’ to society, and gain back ‘lost time’. These were connected to strategies for healthy aging, including social relationships and activities, spirituality, and healthy lifestyles. Challenges to adopting healthy aging practices included physical health difficulties and medication side effects, lack of purpose and boredom associated with daily routines and use of time, and conflicts and loss affecting family and peer relationships.

Conclusion: Social and health services should be tailored to support aging individuals with mental illness and their families, addressing motivations and barriers to adopting healthy lifestyles. Promoting healthy aging practices to enable individuals with mental illness to achieve healthy aging is important for preparing for the aging of this population.

Introduction

Aging experiences vary widely from one person to another and are influenced by various social and interpersonal attributes (Covan, Citation2005). Successful aging involves maintaining physical, mental, and social health, functioning, and activities over time (Chodzko-Zajko, Schwingel, & Park, Citation2009; Dionigi, Horton, & Bellamy, Citation2011). However, people living with mental illness encounter many challenges to aging, and recent research provides overwhelming evidence on health disparities and barriers associated with mental illness. To inform the development of services to meet the changing needs of aging patients with mental illness, and promote healthy aging, it is important to understand their subjective meanings and experiences of aging as well as barriers to adopting healthy lifestyles.

Challenges facing mental health patients as they age

Recent research describes challenges and barriers facing patients with mental illness during the aging process. Mental illness is associated with cognitive, mood, motivational, and health challenges (Aschbrenner et al., Citation2013), and older patients with mental illness experience specific physical, psychological, emotional, and psychosocial needs and challenges compared to younger people. Some limited research on aging among patients with mental illness identifies challenges and needs linked to health, wellbeing, and service access.

Physical and cognitive health

The life expectancy of people with serious mental illness is 25 to 30 years shorter than for the general population (Colton & Manderscheid, Citation2006). Compared to younger people with mental illness and to other older adults, aging patients with mental illness are more likely to experience mobility and functional capacity challenges, higher mortality and illness rates, and cognitive and neurological challenges (Cummings & Kropf, Citation2011; Ramaprasad, Rao, & Kalyanasundaram, Citation2015). Aging intensifies physical, functional, and cognitive challenges associated with mental illness, and affects people’s capacity to manage mental illness (e.g. medication cost and management, access to health information and services) (Cummings & Kropf, Citation2011; Jimenez, Schmidt, Kim, & Cook, Citation2016).

Social and emotional wellbeing

Patients with mental health challenges perceive themselves as subjectively older and experience lower life satisfaction than their healthier peers (Covan, Citation2005; Uotinen, Suutama, & Ruoppila, Citation2003), and experience greater difficulties with social interactions, relationships, and participation, with older age intensifying social challenges (Clifton, Marples, & Clarke, Citation2013; Mueser et al., Citation2010; Ramaprasad et al., Citation2015). Mental illness can strain family relationships and patients with mental illness may be less likely to marry and raise children, limiting family support as they age, and family caregivers may face challenges in addressing needs associated with both mental illness and aging-related changes (Cummings & Kropf, Citation2011). Aging-related challenges also include the death or loss of loved ones. In one study (O’Hare, Shen, & Sherrer, Citation2017), emotional distress from the loss of loved ones (e.g. relatives, friends) was the most significant source of trauma and stress for mental health clients. Aging patients with mental illness may be particularly vulnerable to such losses due to limited social support and social withdrawal. In one study of older mental illness patients (Futeran & Draper, Citation2012), over 80% of psychiatric and medical needs but less than half of social needs were met, illustrating the significance of social exclusion associated with aging and mental illness. Loss of natural support networks associated with aging also means that older patients with mental illness may be more likely to live in long-term care settings (Mueser et al., Citation2010).

Financial challenges represent another concern for aging patients with mental illness (Clifton et al., Citation2013). Due to difficulties with social relationships, education, and employment/income, they may lack social and economic resources and supports in later life. This affects access to services and treatment (due to, for example, a lack of employment-based health or social insurance) (Cummings & Kropf, Citation2011).

Service access

Compared to younger patients, aging patients with mental illness face increased care needs and are more likely to have longer hospital stays and re-hospitalization, lose independent function, and enter residential care (Clifton et al., Citation2013; Yu, Sylvestre, Segal, Looper, & Rej, Citation2015). They are also more likely to receive inadequate, insufficient, and inappropriate care, due to a lack of mental health services and professionals specialized in aging, lack of aging services (e.g. residential or end-of-life care) prepared for mental illness, and ageist attitudes among service providers (Clifton et al., Citation2013; Cummings & Kropf, Citation2011; Morgan, Perez, Frankowski, Nemec, & Bennett, Citation2016). Aging also affects mental illness diagnoses and treatment when symptoms (e.g. anxiety, cognitive impairment) are considered ‘normal’ signs of aging (Cummings & Kropf, Citation2011). On a wider societal level, aging patients with mental illness are affected by ‘double stigma’ and stereotypes of mental illness and aging. This presents barriers to help-seeking, linked to shame, embarrassment, and discomfort in discussing mental health. This may be associated with cultural norms, attitudes, and beliefs about causes of mental illness, as well as family and societal expectations (e.g. family harmony, honour) (Jimenez, Bartels, Cardenas, & Alegría, Citation2013). Aging patients may be more likely than younger adults to experience mental illness stigma, and some experience added stigma and discrimination associated with race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, etc. (Clifton et al., Citation2013; González-Domínguez, Muñoz, Ausín, Castellanos, & Pérez-Santos, Citation2016; Jimenez et al., Citation2013).

Rationales for studying aging among patients with mental illness

With improvements in health care, it is estimated that the lifespan of patients with mental illness will continue to increase and that they will represent up to one in five older adults by 2030 (Cummings & Kropf, Citation2011; Jimenez et al., Citation2013). This means that more people will experience simultaneous challenges associated with mental illness and aging. As aging patients with mental illness face increased care needs (Clifton et al.,Citation2013; Yu et al., Citation2015), targeted programs and interventions are required to address specific challenges associated with aging and mental health (Mueser et al., Citation2010). However, aging patients with mental illness are more likely to receive inadequate, insufficient, and inappropriate support due to a lack of appropriate, specialized, non-discriminatory services, and a lack of responses to specific aging and mental illness needs by government institutions, policy makers, and service providers (Clifton et al., Citation2013; Cummings & Kropf, Citation2011; Morgan et al., Citation2016).

Knowledge of experiences, challenges, and treatment needs of aging patients with mental illness is necessary to properly address challenges facing this growing population. Services and policies should be based on understanding specific physical, social, personal, and financial needs associated with aging and mental illness. Recent research has indicated significant unmet needs associated with aging and mental illness. However, most research about unmet needs and other issues associated with mental illness focuses on younger, rather than aging, patients (Clancy, Happell, & Moxham, Citation2015; Cummings & Kropf, Citation2011; Futeran & Draper, Citation2012; Ramaprasad et al., Citation2015). Little research had examined specific experiences of aging with mental illness, probably due to the relatively short life expectancy of patients with mental illness or institutionalization policies in the past. Yet with an enhanced level of attention to human rights and improved community care services for people with mental illness, patients have a better chance of growing old in the community through various professional and informal support measures. Thus, paying adequate attention to the aging expectations and experiences of patients with mental illness would be useful to inform service development as well as clinical practice to support this aging population with unique health and psychosocial needs. Understanding subjective experiences and expectations of aging among patients with mental illness can inform the development of tailored services and supports that respond to their specific needs, as well as identifying and mitigating barriers to access to existing services and supports, thus contributing to services and support that are more equitable and of better quality (Alegría, Nakash, & NeMoyer, Citation2018; Dowrick et al., Citation2013). While much as been done to examine the use of clinical psychotherapeutic approaches on aging patients (Heisel, Talbot, King, Tu, & Duberstein, Citation2015; Wilkinson, Citation2013), this current study can help to enhance clinicians’ understanding of various personal and social dimensions of aging (e.g. personal relationships, social participation, housing, employment), rather than focusing only on mental illness symptoms.

Research objectives and questions

The aim of this study is to understand the meanings and experiences of aging from the perspective of patients with mental illnesses, and to understand their motivations, challenges, and barriers associated with adopting healthy aging lifestyles and practices. Three key research questions are addressed:

What are the meanings of aging and successful aging for patients living with mental illness?

What do patients with mental illness do to prepare for aging?

What are the motivations, challenges, and barriers for patients with mental health illness in adopting healthy aging lifestyles and practices?

Design and methods

Research design, data collection, and analysis

A qualitative narrative interview approach was adopted to capture stories representing participants’ experiences and perspectives. Narrative interviews can facilitate understanding of research participant’s experiences and behaviours that represent the integrity of their lives and add voices from people who were unheard (Anderson & Kirkpatrick, Citation2016). For aging people, a narrative approach can help to organize experiences and assign meaning, inform modes of being or identity, and guide action, as well as challenging dominant narratives of aging and strengthening resilience and illustrating one’s capacity to cope with challenges in later life (Phoenix, Smith, & Sparkes, Citation2010; Randall, Baldwin, McKenzie-Mohr, McKim, & Furlong, Citation2015). This makes it an ideal approach for this study. Narrative interviews generate stories of experience rather than generalized descriptions (Riessman, Citation2008), ranging from ‘tightly bounded’ narratives to accounts of specific past events consisting of structured beginnings, middles, and ends. Interviewers and respondents become active participants engaged in an evolving conversation in which they jointly make meaning of events and experiences reported by the narrator (Gubrium & Holstein, Citation2002). In this study, narrative interviews followed the process suggested by Bauer (Citation1996).

Data were collected through individual interviews. The interviewers, who were master level social work students and social workers, received a half-day training session consisting of role play and exercises, before pairing up to conduct the interviews. While the first author was involved in the training and design of data collection, the second and third authors were also involved in supervision and actual data collection. In this study, about 20 interviewers were involved in data collection. Many interviews were conducted by two interviewers comprised of a social worker and a master level social work student. This approach ensured that the master students were able to conduct the interviews according to the interview protocols at the initial phase of the data collection. At the later stage, most of the interviews were conducted mainly by four to five student interviewers while a few interviewers had only conducted a small number of interviews. To ensure the quality of the interviews, the interviews were transcribed and reviewed for quality before being processed for further analysis.

To prompt sharing of experiences and stories during interviews, unstructured qualitative questions included “What does ‘being older’ mean to you?”, “As a person with mental illness, what are the pros and cons of becoming older?”, “What does ‘successful aging’ mean in your mind?”, “How do you/how do you see yourself preparing for growing old?”, “What are the challenges and barriers for you to prepare for being older?”, “What are ‘healthy lifestyles and practices’, in your mind?“, and “What are the challenges and barriers to keeping healthy lifestyles and practices?”

In terms of analysis, the integrative use of thematic analysis in qualitative research approaches, including narrative interviews, has been discussed (Anderson & Kirkpatrick, Citation2016; Braun & Clarke, Citation2014). Following Riessman’s (Citation2008) model, analysis focused on narratives and stories and how they were constructed, and the meaning ascribed by participants, with attention to the context of the narratives and the reflexive stance of the researchers. At the same time, thematic analysis was also used to examine the codes, categories, and themes from the ‘bottom up’ of the narratives (Anderson & Kirkpatrick, Citation2016). Due to communication challenges associated with mental health symptoms and related cognitive capacity difficulties, not all participants were able to provide very detailed elaboration and narratives of specific stories. Although incidents, events, and concrete examples were shared, some were presented in segments rather than coherent stories. In order to comprehensively cover key concepts revealed by participants, the details provided in these scenarios and stories were analyzed to identify specific categories related to the research questions. Experiences revealed through stories or story segments were cited to illustrate perspectives and ideas that emerged in narrative data collection.

Research targets and sampling

Participants were patients with a mental illness aged 40 and older, who were emotionally and mentally capable of verbally communicating with the interviewers. Participants were recruited among service users of a non profit service provider specialized in services for patients with mental illness. All participants had previously been clinically diagnosed with a mental illness by a psychiatrist before being referred for mental health care or support services. Participants aged 40 and older (rather than only those 50 and older) were included because aging as a process that happens to everyone, and thinking about and planning for later life can begin before age 50. Additionally, the service provider involved in this study observed that multiple age-related health problems common among older adults, were also common among their 40 to 50-year old clients due to dietary and lifestyle reasons (e.g. hypertension, diabetics, and arthritis). In order to understand how people with mental illness prepare for aging, it is important to include the mid-age group. A total of 61 participants were included in the study. Participants’ demographic characteristics and health background are shown in and . Participants reflected different age cohorts (i.e. 55 to 64, 65 to 74, and 75 years and above) and gender distribution of the service provider's service users. Participants also included adults served by institutional care and community-based services.

Table 1. Demographic profile of the participants (n = 61).

Table 2. Health background of the participants (n = 61).

Results

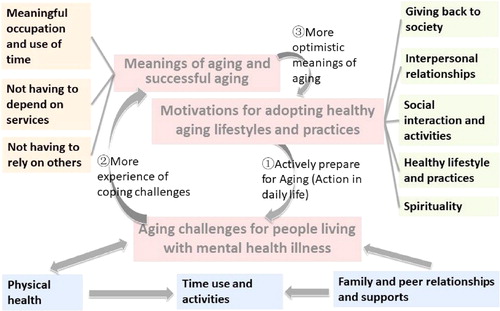

provides a visual overview of the key conceptual themes emerging from the data, showing key meanings, motivations, and constructions of participants’ aging experiences. Key themes and subthemes (in both the description of the results and the figure) were derived from the analysis of participants’ narratives. Individual participants’ narratives were generally structured around three broad themes: the meanings they attached to the process of ‘successful’ aging, their motivations for adopting healthy aging practices, and the challenges they face in attaining these goals. Within each of these areas, individual narratives revealed specific priorities and difficulties, as well as varying levels of preparation, coping, and optimism for the future. The results are organized in a way that highlights elements of narratives falling within these broad themes, and the interconnections between them are visually illustrated in . When analyzing the interview results, attention was paid to potential differences in perspectives according to mental illness and demographic status. However, there were no obvious differences in the participants’ responses according to their different health diagnosis or demographic profiles (e.g. age, accommodation type).

Despite participants’ relatively young age, most expressed specific ideas about the meaning of aging, aging challenges for people living with a mental illness, and motivations for adopting healthy aging lifestyles and practices. Growing old was associated with deteriorating health, mobility, and energy for many participants, affecting possibilities for employment and leisure activities. However, participants also described specific motivations and strategies for achieving healthy aging across a range of domains.

Meanings of aging and successful aging

Participants’ responses about the meaning of aging and successful aging are organized into three broad themes: meaningful occupation and use of time, not having to rely on others, and not being dependent on services.

Meaningful occupation and use of time

Having a meaningful occupation and using time in a meaningful way are associated with successful aging. In addition to providing income and stability, having an occupation is associated with a meaningful role in life, social engagement, motivation and hope, and positive thinking and self-regard. As one participant explained, “I enjoy working the sheltered workshop. It’s fun to work here and I feel my life is meaningful”. Meaningful employment was connected to broader meaningful occupation of time, including through volunteer work, by serving others, and social engagement. Some participants discussed the importance of leisure, travel, entertainment, and arts (e.g. music, drawing) or sports (e.g. hiking, walking) as providing meaningful occupation of time. They described the importance of acquiring, renewing, and engaging in interests and hobbies and spending time with family and friends. As one participant stated, “The best life for me is to have friends and families, to sleep early, get enough rest, and have the opportunity to go travelling”.

Not having to rely on others

Independence and autonomy, or not having to rely on others, is another factor associated with successful aging, particularly in relation to health. Health influences aspects of mobility, engagement in physical leisure activities, and expectations of independence, as well as concerns about avoiding burdening family members. As one participant stated, “I think being happy, free of pain and disease, and having good mobility are the most important things in my life”. A healthy lifestyle, contributing to independence and autonomy, included a balanced diet, good nutrition, and regular physical activity.

Successful, independent aging may require support from social (e.g. family or peer) networks. Participants described the importance of daily support and care from family members, including siblings, parents, children, and spouses, and from friends, colleagues, and religious/church groups. Many described the importance of tangible social supports with finances, activities, employment, and social networks, from human service organizations and human service professionals (e.g. social workers, doctors, nurses), friends, relatives, and workplaces. A few participants described the importance of ‘intangible’ social support, such as advice on health, finances, employment, relationships, welfare, and spirituality, as well as emotional support, such as encouragement, listening, acceptance, validation, and comfort, and spiritual support. The most common sources of ‘intangible’ support were family members, religious/spiritual sources, and human service professionals.

Not having to depend on services

A number of participants would like to avoid relying on formal services as they age. As one stated, “I am trying not to use too many government resources and to rely on myself”. When discussing finances, some participants expressed a desire for independent living, without relying on the government or NGOs (e.g. financial subsidies). Others, however, felt that subsidies would enable them to get rid of financial burden and maintain a good standard of living. To avoid dependence on services, it may be necessary to have other sources of social support (outside formal services). This illustrates a tension in discussions of independence and successful aging: many participants wanted to maintain independence and did not want to rely on others, but also described the importance of social support, which may be necessary to avoid depending on formal services. For example, while some participants wished to avoid reliance on financial subsidies, others described the importance of financial support from relatives.

Aging-related challenges for patients with mental health illness

Participants identified a number of challenges in adopting healthy aging lifestyles and practices, related to physical health, use of time and activities, and family and peer relationships.

Physical health

Participants described physical health challenges as low energy level, ‘deterioration’ of the body, and chronic pain. As one stated, “I hate doing exercises, because I have chronic pain… I don’t want to move my body”. Some participants experienced illnesses such as high blood pressure, high cholesterol, or diabetes, restricting mobility, social engagement, and hobbies, negatively affecting mood, and contributing to feelings of unhappiness and helplessness. For example, one participant explained, “I am even not sure if I can take care of myself… because of my poor health… Our halfway house will take a trip tomorrow… but this time it involves climbing… I cannot join them since my knees are in pain every day”.

Participants also described the side effects of long-term medications, including low physical and mental energy, poor sleep quality, and physical symptoms (e.g. shaking, weight gain, swollen feet). As one explained, “All medicines have similar side effects… This medicine will make you fat, and you are overweight already so you need to do more exercise, and you need to have a balanced diet, and sleep eight hours every day, since you always feel sleepy in the daytime”. Participants could not do what they wanted to, significantly affecting their daily life, aging process, and expectations. Low energy level particularly affected motivation and achievement of goals related to work, social engagement, and leisure. Several participants described feeling tired as a major effect of medication. As one noted, “It is troublesome to take so many medicines, since I always feel very tired after taking medicines… I sleep on time already every day, but I still feel very tired”. Another explained, “I feel very tired every day… especially after taking medicines… I don’t want to do anything but lie in bed and listen to the radio… I don’t know why I can’t sleep well at night… So I feel sleepy and painful in the daytime”. This affected daily activities, as one participant explained: “I will worry if I have not slept well because I will have no energy at work”.

Time use and activities

Some participants described challenges associated with time use and activities, including difficulties filling their time on a day-to-day basis and feeling like they had nothing to do. Some perceived this as a relaxing way to live. As one participant described, “I recently installed a new mobile phone game named Carp King, very fun… I am living a casual life, with a lot of time and without many tasks to do”. For others, however, this reflected a lack of purpose or boredom. As one participant explained, “I wake up late every day… I feel as though I have nothing to do, so I only get up when the staff wakes me up… I do whatever they ask me to do, since I have a lot of time without any specific things to do”. Another noted, “I will take afternoon naps since there is nothing to do, then have a meal again after waking up… After the meal, I will feel tired, have a shower and lie on the bed, listen to the radio, but there is nothing special to listen to”. The patient was affected by physical health and medication side effects. As one participant described, “I’m getting old… and my health is becoming worse… The things I can do are less and less… I can only stay in my hostel”.

Family and peer relationships and supports

Social networks, including family and peer relationships and supports, are very important to successful aging, as well as affecting engagement in activities and use of time. However, participants described challenges associated with family networks and relationships, including separation and loss of family members and a general lack of contact with family members. They also described challenges with peer networks and relationships, including conflicts, loss of friends, and inability to make close friends.

Motivations and strategies for adopting healthy aging lifestyles and practices

Participants identified a range of factors motivating healthy aging lifestyles and practices. Some wished to avoid reliance on others, burdening family members or others, or dependence on services. Others described a desire to ‘give back’ to society, gain back ‘lost time’, or make up for past losses or regrets. Motivations for healthy aging were connected to strategies for healthy aging, including social interactions, relationships, and activities, spirituality, and healthy lifestyle practices.

Giving back to society

When discussing meanings and motivations for successful aging, some participants described a desire to ‘give back’ to society. As one explained, “I have received help before… so I want to give back to society and help others”. Another said, “I would like to give back to the society… The society supported me through CSSA [public financial assistance]… so I always participate in voluntary activities to give back to society… as a helper in the elderly home”. A third explained, “I‘m aged now, but I can face it… I hope I can continue to give back to the society, and not only wait for society to support me through welfare”. They gained happiness through serving others and social engagement. Some mentioned the importance of volunteering as a way of helping and engaging with other people and providing a connection to society. For example, one participant explained, “I think helping others is helping myself… Sometimes I go out to have home-visits with older adults on Saturdays”.

Interpersonal relationships

Another motivating factor and healthy aging strategy is support from significant others, including family members, peers, NGOs, and spiritual groups. Important types of support include emotional support and support for health, employment, finances, spirituality, socialisation, household work, and housing. Some participants described a desire to gain back ‘lost time’ by making up for past losses or regrets, including having more time to spend with children and other family members as well as having intimate relationships. Many described family relationships and support as very important, referring to siblings, parents, children, and spouses. They identified relationships with family members, and receiving tangible and emotional support and care in their daily lives, as important parts of aging. As one participant stated, “The moment I enjoy most is tea time with my children. They support me very much”.

Social interaction and activities

Social interaction and activities represent motivating factors as well as healthy aging strategies. Participants described the significance of peer networks, including relationships with and support (tangible and emotional) from friends, colleagues, and church members. They also described the importance of going out into the community and participating in activities offered by NGOs or other organizations, in order to meet new peers, make friends, develop life goals, and promote happiness. Many participants described efforts to acquire, renew, and engage in interests and hobbies. For some, maintaining an active lifestyle involved leisure activities and exploring new things, enabling them to enjoy life. For others, this provided a chance to make up or compensate for past regrets, open their mind, and engage in meaningful occupation of time.

Spirituality

Spirituality represents an important motivating factor, reflecting a holistic understanding of health and wellbeing. Spirituality has helped participants to set life or career goals, have a direction in life, and provide a sense of hope and meaning. Spirituality also helped patients to increase interpersonal trust, serve society, and express thanks and gratitude, with social responsibility considered important to successful aging. As one participant said, “I believe in Buddhism… If you hope to gain happiness from others, you should give happiness to others first”. Spirituality was linked to participation in religious activities, providing opportunities for social connection and support. As another participant described, “I also go to the church and religious group gathering every Thursday and Sunday. These brothers and sisters support me very much… God helped me and friends supported me during the hard time. They helped me to know that I am a useful person and that my life is meaningful”.

Healthy lifestyle and practices

Many participants discussed the importance of healthy lifestyle and practices in preparing for aging, particularly healthy diet and regular exercise. They generally had a good understanding of approaches for staying healthy, such as seeking out information or professional advice and regular exercise. As one participant explained, “A healthy diet is very important to the elderly… Now I am studying cooking. I go to the cooking class, then I can share the food with my roommates and they all love it”. For some participants, healthy lifestyle motivations were associated with health conditions (e.g. diabetes) or a desire to control weight. One reported, “We always chat on the topic of losing weight, because I want to make myself healthier”.

Many participants described strong motivations and preparation for healthy aging. Others described more passive approaches, such as ‘following the natural course’ of aging or accepting the ‘status quo’. For some, this was associated with an effort to try to live in and enjoy the present. A small number of younger participants felt that they were too young to think about aging and expressed uncertainty about their future. This was a coping method to face aging and mental illness when facing feelings of hopelessness, a lack of options, and fears of shortened life span, which affected feelings about aging.

Discussion

Meanings of ‘successful’ aging, coping and management capacities and supporting factors, and associated challenges and barriers, influence aging-related motivations, preparation, and experiences. Meanings of aging, motivations, preparation for aging, and challenges and barriers interact in different ways. For some people, these form a ‘vicious circle’. Pessimistic meanings of aging (e.g. uncertainty or fear) may be associated with a refusal to think about and prepare for aging, and a lack of motivation or ability to maintain a healthy lifestyle (e.g. due to medication or housing challenges). Preparation strategies may be ‘passively’ implemented, following the natural course of aging, and people may struggle to cope when facing unexpected challenges or barriers (health-related, financial, or social). For others, these factors combine to form a ‘virtuous circle’. More optimistic meanings of aging (e.g. hopefulness, readiness) may be associated with more active preparations for aging. Motivations may be associated with spiritual pursuits, support from others, and making up for past regrets, which inform active efforts to maintain a healthy lifestyle. When facing unexpected challenges or barriers, these people may draw on coping and management strategies such as wisdom or insight gained from experience, reassuring self-talk, financial management, and work-life balance. The impacts of these challenges are mediated by supporting factors such as personality, health, family support, interpersonal relationships, access to services, and financial resources.

When discussing meanings of successful aging, participants highlighted the importance of meaningful occupation and use of time (through employment, serving others, and social engagement), not having to rely on others (including in health-related areas), and not being dependent on formal services. At the same time, they emphasized the importance of tangible social support from family members and peer networks. These reflect a key tension facing aging people with mental illness: the desire for independence and autonomy, and the need for social and formal supports. This is reflected in previous research findings on formal care and health service needs (Clifton et al., Citation2013; Mueser et al., Citation2010; Yu et al., Citation2015) and financial challenges (Clifton et al., Citation2013; Cummings & Kropf, Citation2011) among aging people with mental illness. While the priorities identified by participants echo to some extent existing operational definitions of successful aging, they also highlight key gaps. Operational definitions of successful aging tend to focus heavily on physiological constructs and engagement, with less attention to personal resources such as independence or autonomy or extrinsic factors such as finances (Cosco, Prina, Perales, Stephan, & Brayne, Citation2014). Participants identified a number of challenges to adopting healthy aging practices, related to physical health difficulties and medication side effects, lack of purpose and boredom, and conflicts and loss affecting family and peer relationships. These echo previous research findings on challenges facing aging patients with mental illness in areas of physical health and disability and family and social relationships and functioning (Clancy et al., Citation2015; Clifton et al., Citation2013; Cummings & Kropf, Citation2011; Futeran & Draper, Citation2012; Mueser et al., Citation2010; Ramaprasad et al., Citation2015). The current findings also highlight challenges associated with daily routines and use of time, which have been paid less attention in previous research.

Participants identified a range of factors motivating them to adopt healthy aging practices, including desires to avoid relying on or ‘burdening’ other people and to ‘give back’ to society or gain back ‘lost time’. Motivations for healthy aging were connected to strategies for healthy aging, including social interactions, relationships, and activities, spirituality, and healthy lifestyle practices. These motivations and strategies can be understood not only as part of individual healthy aging, but also as ways of challenging stigma and stereotypes associated with both mental illness and aging, which affect aging patients with mental illness (Clifton et al., Citation2013; González-Domínguez et al., Citation2016; Jimenez et al., Citation2013).

Implications

These findings highlight the need for mental health and social services to ensure that aging patients with mental illness can take a lead in making decisions about types and sources of support they receive (client-led decision making), to avoid perceptions of dependence or burden, and to enhance feelings of autonomy, independence, and agency. There is also a need for services facilitating access to employment and volunteer opportunities specifically for aging patients with mental illness, and actively addressing potential barriers and stigma. Service providers in both community-based and residential services serving aging patients with mental illness could also implement activities specifically aimed at strengthening family relationships, as well as friendship or peer support programs. The findings from this study point to a holistic conception of health and wellbeing among aging patients with mental illness, moving beyond individualized interventions or treatment to encompass services and supports focused on interpersonal, social, economic, and spiritual dimensions of wellbeing.

When discussing services and support for aging patients with mental illness, this study also adds new perspectives for clinical intervention practice. For example, cognitive behavioral intervention (CBI) is a commonly used clinical approach to enable patients to reframe negative thoughts into positive thinking, in order to support positive behaviors in the face of difficulties (Fenn & Byrne, Citation2013). The study findings offer new perspectives and contexts that can enable clinicians to address issues that underpin some of the challenges and barriers to building positive thinking and behaviors among aging patients with mental illness. Similarly, understanding the aging issues and concerns of these patients can facilitate the application of interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT), another commonly used approach to treat mood disorders through improving interpersonal relationships by reducing distress and strengthening capacity in resolving interpersonal deficits and disputes and enhancing strategies for handling life transitions (Wilfley & Shore, Citation2015). The study findings can inform clinicians of unresolved issues and challenges facing patients, enabling them to address a holistic life course context and concrete realities related to interpersonal and mood related distress.

Study limitations

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, nearly half of the participants (28 of 61) were under age 50. While they shared their perspectives on the meaning of future aging, and motivations and strategies for preparing for healthy aging, their experiences may not reflect those who are older in age with mental illness. In addition, due to the sample size and the lack of specific etiological details during the interviews, the study was unable to delineate variations in participant perspectives and experience according to diagnosis. As a qualitative study, it was difficult to examine the associations between participants’ health diagnosis or demographic profiles (e.g. age, accommodation type) and specific patterns or unique results among participant subgroups. . Future research could continue to examine relationships between perceptions or expectations of aging, and demographic and health status.

Conclusion

This study highlights the specific meanings of ‘healthy aging’ among patients with mental illness, challenging deficit-focused assumptions and highlighting the motivations and strategies that inform ways to maintain physical, mental, social, and spiritual wellbeing in the face of combined challenges of aging and mental illness.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Ms. Sania Yau, the late CEO of New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association. She collaborated with the research team to create this research and facilitated access to clients with mental illness to take part in this study. We also thank the staff of New Life Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association for facilitating access to participants, conducting interviews, and logistical arrangements. We thank the participants who shared their views in this research. The support from research staff of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University including Mr. Jerry Nip and Ms. Fani Wong, and master students from Chinese University of Hong Kong, is much appreciated.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Daniel W. L. Lai

Daniel W.L. Lai was principal investigator of the study, conceptualized and designed the study, identified recruitment sources, provided training the interviewers, coordinated data collection, led and supervised data analysis, drafted and critically reviewed the paper. K.C. Chan was co-investigator of the study, co-designed the study, coordinated recruitment and data collection, oversaw data collection, involved in discussion of the results, critically reviewed the draft and provided inputs. X.J. Xie involved in data collection, data analysis, and organizing the results for paper development. G.D. Daoust organized research findings and drafted parts of the paper.

K. C. Chan

Daniel W.L. Lai was principal investigator of the study, conceptualized and designed the study, identified recruitment sources, provided training the interviewers, coordinated data collection, led and supervised data analysis, drafted and critically reviewed the paper. K.C. Chan was co-investigator of the study, co-designed the study, coordinated recruitment and data collection, oversaw data collection, involved in discussion of the results, critically reviewed the draft and provided inputs. X.J. Xie involved in data collection, data analysis, and organizing the results for paper development. G.D. Daoust organized research findings and drafted parts of the paper.

X. J. Xie

Daniel W.L. Lai was principal investigator of the study, conceptualized and designed the study, identified recruitment sources, provided training the interviewers, coordinated data collection, led and supervised data analysis, drafted and critically reviewed the paper. K.C. Chan was co-investigator of the study, co-designed the study, coordinated recruitment and data collection, oversaw data collection, involved in discussion of the results, critically reviewed the draft and provided inputs. X.J. Xie involved in data collection, data analysis, and organizing the results for paper development. G.D. Daoust organized research findings and drafted parts of the paper.

G. D. Daoust

Daniel W.L. Lai was principal investigator of the study, conceptualized and designed the study, identified recruitment sources, provided training the interviewers, coordinated data collection, led and supervised data analysis, drafted and critically reviewed the paper. K.C. Chan was co-investigator of the study, co-designed the study, coordinated recruitment and data collection, oversaw data collection, involved in discussion of the results, critically reviewed the draft and provided inputs. X.J. Xie involved in data collection, data analysis, and organizing the results for paper development. G.D. Daoust organized research findings and drafted parts of the paper.

References

- Alegría, M., Nakash, O., & NeMoyer, A. (2018). Increasing equity in access to mental health care: A critical first step in improving service quality. World Psychiatry, 17(1), 43–44.

- Anderson, C., & Kirkpatrick, S. (2016). Narrative interviewing. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 38(3), 631–634.

- Aschbrenner, K., Carpenter-Song, E., Mueser, K., Kinney, A., Pratt, S., & Bartels, S. (2013). A qualitative study of social facilitators and barriers to health behavior change among persons with serious mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 49(2), 207–212.

- Bauer, M. (1996). The narrative interview: Comments on a technique for qualitative data. Papers in Social Research Methods Qualitative Series No. 1. London: London School of Economics and Political Science Methodology Institute.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). What can "thematic analysis" offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 26152.

- Chodzko-Zajko, W., Schwingel, A., & Park, C. H. (2009). Successful aging: The role of physical activity. American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine, 3(1), 20–28.

- Clancy, L., Happell, B., & Moxham, L. (2015). Perception of risk for older people living with a mental illness: Balancing uncertainty. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 24(6), 577–586.

- Clifton, A., Marples, G., & Clarke, A. (2013). Aging with a serious mental illness: A literature and policy review. Mental Health Review Journal, 18(2), 65–72.

- Colton, C. W., & Manderscheid, R. W. (2006). Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Preventive Chronic Disease, 3, 1–14.

- Cosco, T. D., Prina, A. M., Perales, J., Stephan, B. C., & Brayne, C. (2014). Operational definitions of successful aging: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(03), 373–381.

- Covan, E. (2005). Meaning of aging in women's lives. Journal of Women & Aging, 17(3), 3–22.

- Cummings, S. M., & Kropf, N. P. (2011). Aging with a severe mental illness: Challenges and treatments. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 54(2), 175–188.

- Dionigi, R., Horton, S., & Bellamy, J. (2011). Meaning of aging among older Canadian women of varying physical activity levels. Leisure Sciences, 33(5), 402–419.

- Dowrick, C., Chew-Graham, C., Lovell, K., Lamb, J., Aseem, S., Beatty, S., … Gask, L. (2013). Increasing equity of access to high-quality mental health services in primary care: A mixed-methods study. Programme Grants for Applied Research, 1(2), 1–184.

- Fenn, K., & Byrne, M. (2013). The key principles of cognitive behavioural therapy. Innovait: Education and Inspiration for General Practice, 6(9), 579–585. https://doi.org/10.1177/1755738012471029

- Futeran, S., & Draper, B. M. (2012). An examination of the needs of older patients with chronic mental illness in public mental health services. Aging and Mental Health, 16(3), 327–334.

- Gubrium, J. F., & Holstein, J. A. (2002). Handbook of interview research: Context and method. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- González-Domínguez, S., Muñoz, M., Ausín, B., Castellanos, M. A., & Pérez-Santos, E. (2016). Age-related self-stigma of people over 65 years old: Adaptation of the Internalized Stigma of Mental Illness scale (ISMI) for use in age-related self-stigma (IS65+) in a Spanish sample. Aging and Mental Health, 22, 250–256

- Heisel, M. J., Talbot, N. L., King, D. A., Tu, X. M., & Duberstein, P. R. (2015). Adapting interpersonal psychotherapy for older adults at risk for suicide. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(1), 87–98.

- Jimenez, D. E., Bartels, S. J., Cardenas, V., & Alegría, M. (2013). Stigmatizing attitudes toward mental illness among racial/ethnic older adults in primary care. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(10), 1061–1068.

- Jimenez, D. E., Schmidt, A. C., Kim, G., & Cook, B. L. (2016). Impact of comorbid mental health needs on racial/ethnic disparities in general medical care utilization among older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32, 909–921. doi:

- Morgan, L. A., Perez, R., Frankowski, A. C., Nemec, M., & Bennett, C. R. (2016). Mental illness in assisted living: Challenges for quality of life and care. Journal of Housing for the Elderly, 30(2), 185–198.

- Mueser, K. T., Pratt, S. I., Bartels, S. J., Swain, K., Forester, B., Cather, C., & Feldman, J. (2010). Randomized trial of social rehabilitation and integrated health care for older people with severe mental illness. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(4), 561–573.

- O’Hare, T., Shen, C., & Sherrer, M. V. (2017). Subjective distress from trauma in older clients with severe mental illness. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 27(3), 180–186.

- Phoenix, C., Smith, B., & Sparkes, A. C. (2010). Narrative analysis in aging studies: A typology for consideration. Journal of Aging Studies, 24(1), 1–11.

- Ramaprasad, D., Rao, N. S., & Kalyanasundaram, S. (2015). Disability and quality of life among elderly persons with mental illness. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 18, 31–36.

- Randall, W., Baldwin, C., McKenzie-Mohr, S., McKim, E., & Furlong, D. (2015). Narrative and resilience: A comparative analysis of how older adults story their lives. Journal of Aging Studies, 34, 155–161.

- Riessman, C. K. (2008). Narrative methods for the human sciences. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Uotinen, V., Suutama, T., & Ruoppila, I. (2003). Age identification in the framework of successful aging: A study of older Finnish people. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 56(3), 173–195.

- Yu, C., Sylvestre, J. D., Segal, M., Looper, K. J., & Rej, S. (2015). Predictors of psychiatric re‐hospitalization in older adults with severe mental illness. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(11), 1114–1119.

- Wilfley, D. E., & Shore, A. L. (2015). Interpersonal psychotherapy. In J. D. Wright (Ed.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 631–636). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Wilkinson, P. (2013). Cognitive behavioural therapy with older people. Maturitas, 76(1), 5–9.