Abstract

Objectives: Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a complex neurodegenerative disorder with a broad list of motor and non-motor symptoms (NMS) that has been shown to affect the relationship quality (mutuality) and caregiver burden. However, little is known if the effect of motor and NMS on caregiver burden is mediated by mutuality. Therefore, the aim of this study was to explore if perceived mutuality by patients and partners mediates the effect of motor and NMS on caregiver burden.

Methods: Data were collected from 51 dyads with one PD patient, including measures of motor signs, NMS, impaired cognition, patients’ and partners’ perceived mutuality, caregiver burden and dependency in activities in daily life (ADL). Structural equation model with manifest variables were applied to explore if patients’ and partners’ mutuality score mediated the effect of motor signs, NMS, ADL or impaired cognition on caregiver burden.

Result: Our results suggest that having a partner with PD who is dependent in ADL or has impaired cognition decreases partners’ mutuality which leads to elevated burden. Motor symptoms or other NMS were not associated with partners’ mutuality or caregiver burden. Instead, increasing severity of motor symptoms decrease patients’ mutuality in turn leading to lower level of partners’ mutuality.

Conclusion: Our findings enhance the understanding of the complexity of living with PD for the partner and suggest that clinical assessment should include evaluation of how PD symptoms influence the quality of the relationship between partners and patients.

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a complex neurodegenerative disorder which can be challenging to live with not only for the patients but also for their partners (K. Ray Chaudhuri, Citation2011; Fereshtehnejad, Citation2016; Maffoni, Giardini, Pierobon, Ferrazzoli, & Frazzitta, Citation2017; Schrag & Quinn, Citation2000). Although not all partners regard themselves as caregivers, patients often rely on their partners for support or help with medications, transporting, shopping and other daily activities as the disease advances. As the disease advances, the person with PD needs more help and the partner often becomes the main provider of this informal care without any training, support or remuneration. This increasing need of help, support or supervision may narrow down caregivers’ possibility to live an unrestricted social life e.g. visiting friends, with or without the person with PD (Lokk, Citation2009). There is no universal definition of caregiver burden but it is referred to as a negative physical, emotional and financial effect on partners’ experience of wellbeing when performing caregiving tasks (Martinez-Martin, Rodriguez-Blazquez, & Forjaz, Citation2012). Caregiver burden has been associated with severity of motor impairment and non-motor symptoms (NMS) of the person with PD such as cognitive impairment, depression and fatigue (Aarsland, Larsen, Karlsen, Lim, & Tandberg, Citation1999; D'Amelio et al., Citation2009; Lokk, Citation2008; Martinez-Martin et al., Citation2008; Martinez-Martin, Forjaz et al., Citation2007; Schrag, Hovris, Morley, Quinn, & Jahanshahi, Citation2006).

In most marital relationships caring for and supporting each other, are integral parts of the relationship. Previous studies of dementia care have reported that caregivers having high relationship quality toward the care receiver are less likely to consider institutionalization of the care receiver and are also more prone to continue the care at home (Hirschfeld, Citation1983; Spruytte, Van Audenhove, & Lammertyn, Citation2001). Mutuality, defined as the “positive quality of the relationship between the caregiver and care-receiver” consists of four dimensions: love and affection, shared pleasurable activities, shared values, and reciprocity (Archbold, Stewart, Greenlick, & Harvath, Citation1992; Archbold, Stewart, Greenlick, & Harvath, Citation1990). Mutuality has been found to be an important protective factor of burden in caregivers of persons with chronic diseases. Conversely, low mutuality may increase the risk of strain or burden (Archbold et al., Citation1990; Ball et al., Citation2010; Campbell et al., Citation2008; Francis, Worthington, Kypriotakis, & Rose, Citation2010; Halm & Bakas, Citation2007; Hooker, Grigsby, Riegel, & Bekelman, Citation2015; Hsiao & Tsai, Citation2014; Yates, Tennstedt, & Chang, Citation1999). In PD, behavioural problems and gait impairment have been associated with lower level of mutuality (Goldsworthy & Knowles, Citation2008; Tanji et al., Citation2008). Thus, high mutuality may allow caregivers to endure in difficult care situations but mutuality has also been reported to decrease in later stages of PD (Carter et al., Citation1998; M. Karlstedt, Fereshtehnejad, Winnberg, Aarsland, & Lokk, Citation2017). However, very few studies have explored PD symptoms’ association with mutuality and caregiver burden.

According to most of the stress theories used in caregiving research, primary stressors consist of objective indicators such as disease related factors which will affect appraisals and protective factors such as mutuality (Goldsworthy & Knowles, Citation2008; Greenwell, Gray, van Wersch, van Schaik, & Walker, Citation2015). These stressors can, directly or indirectly through appraisals or protective factors such as mutuality, affect caregiving outcomes such as burden (Greenwell et al., Citation2015). In statistics, the construct of a mediation model is designed to measure the change in the association between the independent variable and the dependent through the inclusion of a third variable (Rucker, Preacher, Tormala, & Petty, Citation2011). In PD research very few studies have explored the mediating effect of mutuality on caregiver burden. Building on an extended version of Chappel and Reids’ stress-appraisal model, Goldsworthy and Knowles (Citation2008) found that the caregivers’ perceived relationship quality mediated the effect of behavioral problems on caregiver burden (Goldsworthy & Knowles, Citation2008). Limitations of this study were serious medical conditions other than PD, in the majority of patients. Furthermore, only caregivers’ mutuality was included in the model (Goldsworthy & Knowles, Citation2008). We have recently shown that perceived mutuality by one member of the dyad seems to be an important contributor to the other members’ perceived level of mutuality (M. Karlstedt, Fereshtehnejad, Aarsland, & Lokk, Citation2017). Also, our prior results showing that the effects of motor and NMS on PD patients’ HRQoL are partly mediated by either patients’ or partners’ mutuality (Michaela Karlstedt, Fereshtehnejad, Aarsland, & Lökk, Citation2018). Thus, it is reasonable to believe that partners’ or patients’ mutuality may also act as a mediator between PD symptoms and caregiver burden. By constructing a hypothetical mediation model guided by the stress process model by Greenwell, Gray, van Wersch, van Schaik and Walker (Citation2015) we disentangled different pathways that may explain the effect of PD specific symptoms on caregiver burden. This knowledge is needed to fully understand PD symptoms’ association with caregiver burden. The results may inform whether the influence of mutuality by partners or patients is an effective mechanism that may decrease caregiver burden. Also, it may help guiding future research and pave way for care models that improve caregivers’ wellbeing. Therefore, the aim of the present study was to expand our previous research by testing the mediating effect of partners’ and patients’ mutuality on caregiver burden. We hypothesized that motor, NMS, impaired cognition and dependency in ADL in addition to acting as primary stressors with direct effects, also have indirect effects through partners’ and/or patients’ mutuality on caregiver burden.

Material and methods

Participants and procedure

During 2014–2015, 51 PD dyads were recruited from movement disorders clinics at Karolinska University Hospital (n = 42), Sweden and through advertisement in the journal of the Swedish Parkinson’s disease Association (n = 9). All self-rated questionnaires used in the study were filled out individually and separately by the dyads, in the presence of the first author. These were done at the out clinic or during a home visit whichever was preferred by the participants. Eligible participants were those dyads who had been living together as partners for 3 years or more, aged > 55, with no other severe medical conditions except for one member of the dyad who was diagnosed with PD. Furthermore, the dyads should not be in the phase of life rearing small children and none the partners should be employed as a caregiver. The included participants consisted of 22 (43.1%) female partners and 29(56.9%) male patients. Mean age of patients and partners were 70.9 (SD = 8.5) and 70.7 (SD = 9.3) years, respectively and the mean length of cohabitation was 38.4 (SD = 14.5) years.

Ethics

The study was approved by the local research ethics committee (registration number: 2013/1812-31/3) and was conducted in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki.

Measurement

Sociodemographic data regarding education, income, work status, PD duration were also collected. The Hoehn and Yahr (H/Y) scale was used to determine stage of PD. It contains 6 stages where 0 indicates no visible symptoms and 5 represents a patient who is unable to walk unless assisted (Hoehn & Yahr, Citation2001)

Primary stressors

The 14 items Unified Parkinson´s Disease Rating scale -Part III (UPDRS III) was used to measure severity of PD specific motor signs. The scale is a 5-point Likert scale. Higher scores indicate more severe motor signs (Fahn, Elton, & Committee., a. M. o. t. U. D, Citation1987).

To detect functional changes associated with decline in cognitive function, the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) was used. The scale comprises 26 items and was filled out by the partner. The individual score is ranging between 1 and 5 and is calculated by the mean across all item scores. Higher score (>3) indicates decline in cognitive functioning. Cronbach’s alpha has been reported ranging between 0.93 and 0.97 (Jorm, Citation2004).

To detect PD specific non-motor manifestations, the Non-motor Symptom Questionnaire (NMSQuest) was used. The scale comprises 30 items and is scored “yes” or “no”. The scale contains domains such as: urinary, cardiovascular, depression/anxiety, memory, sexual function, sleep disorder, digestive, hallucination/delusion and miscellaneous the. Higher score indicates higher frequency of non-motor manifestations (K. R. Chaudhuri et al., 2006; Martinez-Martin, Schapira et al., Citation2007).

An extended modified form of Katz index was used to detect the level of dependency in ADL of the person with PD (Asberg & Sonn, Citation1989). The scale contains items assessing grooming/dressing, bathing, food intake, toileting, walking/transferring, housekeeping and shopping. The scale is a 4-point Likert scale (0 = no help to 3 = need all help) and was filled out by the partner. A dichotomous variable (0 = independent 1 = dependent) was created aiming to assess dependency.

Mediator

To measure the positive quality of the caregiver-care receiver relationship the 15 items Mutuality scale (MS) was used (Archbold et al., Citation1992; Archbold et al., Citation1990). The scale contains 15 items and is a 5-point Likert scale (0= not at all to 4= a great deal). It covers domains such as: love and affection (3 items), shared pleasurable activates (4 items), shared values (2 items) and reciprocity (6 items). The individual score is ranging between 0 and 4 and is calculated by the mean across all item scores. Higher scores indicate higher perceived relationship quality between the care-dyads. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated for the Swedish version of MS as 0.936 and 0.933 for patients’ and partners’, respectively (M. Karlstedt, Fereshtehnejad, Winnberg, et al., Citation2017).

Caregiving outcome

The 22-items caregiver burden scale (CBS) was used to measure perceived burden of the partner. The scale evaluates domains such as general strain, isolation, disappointment, emotional involvement and environment. The scale is a 4-point Likert scale (1 = not at all to 4 = often). Higher score (range 22-88) indicates greater level of stress and burden (Elmstahl, Malmberg, & Annerstedt, Citation1996). Cronbach’s alpha has been calculated as 0.88 in previous PD samples (Caap-Ahlgren & Dehlin, Citation2002).

Statistical analyses

Percentage, frequency, means (m), standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range (IQR) were used to describe dyads’ characteristics and disease-related factors.

Within the NMSQuest scale two missing items by two participants were identified. The individual score by these participants were larger than the sample median. To avoid case-wise deletion and loss of statistical power, these missing items were imputed with a zero score.

Assumptions of multicollinearity were examined prior to the analyses through tolerance and variance inflation factor (VIF). Tolerance (>0.4) and VIF index (<2.5) were consider acceptable. No influential multivariate outliers were detected using Malahanobis and Cooks distance (CitationTabachnick, 2012).

Our mediation model was based on our a priori hypothesis on the relationship between included variables and a modified form of the proposed stress-process model (Greenwell et al., Citation2015). To test our hypothetical mediation model, structural equation modeling (SEM) with manifest variables was performed. This means that UPDRS III, NMSQuest, IQCODE and ADL were served as primary stressors (exogenous variables), caregiver burden as the outcome variable (endogenous variable) and patients’ and partners’ mutuality as mediators (endogenous variables).

Several measures can be used to evaluate how well the constructed model fits the data. In the present study a model was considered well fitted if the result of the chi-square test was non-significant, the Comparative fit index (CFI), Normed Fit Index (NFI), Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), Goodness-of-Fit statistic (GFI) were above .95 and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was less than .05 (Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, Citation2008). We used squared multiple correlations to assess how much of the variance could be explained by the included exogenous variables in the endogenous variables.

Maximum likelihood estimation was used to calculate the total, direct and indirect effects between exogenous and endogenous variables and are presented as standardized path coefficients. An advantage of using SEM is that indirect effects (mediation) can be tested within the model. The bias-corrected bootstrap method was used to test indirect effects (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008). The 95% confidence interval (CI) was determined following 2000 iterations from the sample of 51 participants.

We used typology and interpretation proposed by Zaho et al to classify and understand different types of mediation (Zhao, Lynch, & Chen, Citation2010). The model was adjusted by age and gender. Based on prior results gender was chosen to adjust the effect on patients’ mutuality (M. Karlstedt, Fereshtehnejad, Aarsland, et al., Citation2017). A p-value of .05 or less was regarded as statistically significant.

All data analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 23 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) and AMOS graphic module version 23 (IBM INC).

Result

Sociodemographic and clinical features are presented in

Path analysis

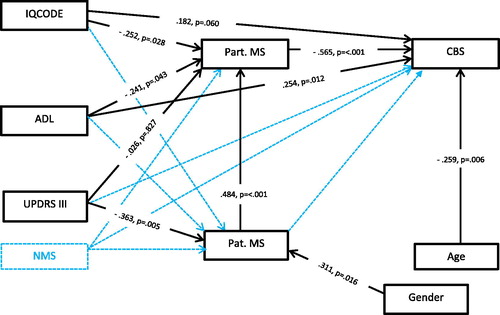

illustrates the relationship between factors affecting partners’ and patients’ mutuality and caregiver burden.

Figure 1. Direct effects reported as standardized path coefficients for the final model with caregiver burden as outcome. Dashed lines are non-significant direct paths which were removed in the final analysis. The best fit of the final model was achieved with χ2=7.658, df = 8, CMIN/DF=.957, p=.468, GFI=.965, NFI=.938, CFI = 1.0, TLI = 1.0 and RMSEA=.00 (95%CI=.000-.161).

Abbreviation: PD = Parkinson’s disease, Pat.MS = PD patient mutuality scale, Part. MS = PD-partner mutuality scale, CBS: Caregiver burden scale, IQCODE: Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly, NMS: Non-motor Symptoms Questionnaire, UPDRS III: the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale-Part III, ADL: Activities in daily life (0 = independent, 1 = dependent), Gender: 0 = female,1 = male, Age = PD partners age.

The preliminary model resulted in poor fit and several of the path coefficients were non-significant including the path between patients’ mutuality and CBS indicating that patients’ mutuality did not act as mediator on CBS. Due to the small sample size unrequired paths not needed for the analysis were discarded one by one. The standardized direct effects and the best fit of the final model are presented in . The final model explained 40.8% of the variance in partners’ mutuality, 18.9% in patients’ mutuality, and 61.0% in caregiver burden.

Direct effects

The significant direct effect of disease-related factors (ADL beta= –.241, p=.043 and IQCODE beta= –.252, p=.028) on partners’ MS score and the significant direct effect of partners’ MS score (beta= –.565, p= <.001) on caregiver burden indicated that partners’ mutuality may act as mediator. This means that decline in cognitive function and need of support or help in ADL decreases partners’ mutuality, thus combined effect of these variables and mutuality may influence the experience of burden. The UPDRS III scores were neither associated with partners’ mutuality nor caregiver burden, instead higher UPDRS III scores (beta= −.363, p=.005) were associated with lower level of patients’ mutuality. This implies that the effect of motor signs (UPDRS III) may influence partners’ mutuality through patients’ mutuality.

Indirect and total effect

Indirect and total effects are presented in .

Table 2. Indirect and total effect of disease related factors on caregiver burden.

The test of indirect effects revealed that effect of dependency in ADL on caregiver burden was mediated by partners’ mutuality (beta=.136, p=.048). In other words, having a partner with PD who is dependent in daily activities leads to a decrease in partners’ mutuality in turn leading to higher burden. The significant direct effect (beta= .391, p = .002) indicates a complementary mediation and points towards omitted mediators.

The direct effect of impaired cognition (increasing IQCODE scores) on caregiver burden was non-significant (beta=.182, p=.060). The effect was instead mediated by partners’ mutuality (beta=.142, p=.014). This means that decline in cognitive function decreases partners’ mutuality resulting in higher burden. The lack of significant direct effect indicates an indirect-only mediation.

Increasing UPDRS III scores had a non-significant direct effect on partners’ mutuality (beta=–.026, p=.827). Instead, the effect of increasing severity of motor symptoms leads to a decrease in patients’ mutuality in turn leading to decreasing level of partners’ mutuality (beta = −.176, p = .006).

Discussion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, that has explored if patients’ or partners’ mutuality act as mediator on caregiver burden. In the present study we have tried to capture the complexities of the caregiving situation by examining the association between a set of disease-related factors identified as central predictors of PD caregivers’ burden through the use of a path model (Greenwell et al., Citation2015; Martinez-Martin et al., Citation2012; Mosley, Moodie, & Dissanayaka, Citation2017). In doing so, we attempt to disentangle different direct and indirect ways clinical variables and mutuality may affect burden. Our findings indicate that mutuality plays an important role as a mediator between some stressors and caregiver burden which is in line with the results of other studies (Goldsworthy & Knowles, Citation2008; Lawrence, Tennstedt, & Assmann, Citation1998; Yates et al., Citation1999). Consistent with prior research, dependency in ADL was associated with higher levels of burden (Aarsland et al., Citation1999; Caap-Ahlgren & Dehlin, Citation2002; Santos-Garcia and de la Fuente-Fernandez, Citation2015; Schrag et al., Citation2006). However, our results also suggest an indirect effect of dependency in ADL on burden through partners’ mutuality. That is, having a partner who needs some form of supervision or help in ADL decreases partners’ mutuality in turn leading to higher levels of burden. This type of indirect effect could be classified as a complementary mediation indicating that there may be other omitted mediators explaining the association between dependency and burden (Zhao et al., Citation2010). Since it has been suggested that being more optimistic may protect PD spouses against future development of burden, other variables of interest in future studies might be personality styles linked to coping strategies and mutuality (Jones et al., Citation2017; Lyons, Stewart, Archbold, & Carter, Citation2009). Perhaps more optimistic caregivers are using more effective coping strategies in turn leading to higher mutuality and lower levels of burden. Future intervention studies aiming to maintain or improve mutuality by e.g. some form of dyadic acceptance and adjustment therapy is another interesting direction of future research that may improve the dyads’ wellbeing (Ghielen et al., Citation2017)

The negative effect of impaired cognition on caregiver burden is well known from the literature (K. Ray Chaudhuri, Citation2011; Greenwell et al., Citation2015; Martinez-Martin et al., Citation2012). However, in the present study there was no significant direct effect of impaired cognition on caregiver burden. Instead, an indirect-only mediation was observed, indicating that a decline in cognitive function decreases partners’ mutuality which in turn leads to elevated burden. This type of mediation indicates that influence of impaired cognition on burden is only effective through partners’ mutuality (Zhao et al., Citation2010).

In contrast to our initial hypothesis, neither motor nor frequency of NMS directly influence partners’ mutuality and caregivers’ experience of burden. Instead, an indirect-only mediation of the effect of motor symptoms on partners’ mutuality through patients’ mutuality was observed. That is, higher frequency of motor symptoms decreases patients’ mutuality in turn leading to lower level of partners’ mutuality.

In summary, our results are in line with several qualitative studies showing PD as a relationally-disruptive illness challenging the dyadic relationship (Birgersson & Edberg, Citation2004; Haahr, Kirkevold, Hall, & Ostergaard, Citation2013; Martin, Citation2016). However, facing these challenges and working together as a couple may also strengthen the relationship (Chiong-Rivero et al., Citation2011; Martin, Citation2016). Even though the result of our model is quite complex, understanding the relationship between disease-related factors, mutuality and burden is important because improving the support of PD dyads may have a bearing on future interventions and delay the need of nursing home placement. Even if higher level of partners’ mutuality may act as a shield against elevated caregiver burden, our results suggest that clinicians should be aware of patients’ decline in cognitive function and dependency in ADL as risk of elevating caregiver burden because the suffering of partners’ mutuality. Similarly, partners’ perceived mutuality may also decrease when patients’ mutuality suffers because of higher frequency of motor symptoms.

Conducting regular family meetings with both members of the dyad aiming to disentangle and discuss the ways PD affects different dimensions of mutuality may be helpful to detect risk dyads and personalize future interventions. For instance, a decline in cognitive function or having a partner who needs help in ADL may alter relational roles if the partner takes over the patient’s former responsibilities (Martin, Citation2015). In similar way patients’ experience of motor symptoms and not being able to carry out day-to-day tasks they previously took for granted may cause frustration and sadness resulting in withdrawal (Soleimani, Negarandeh, Bastani, & Greysen, Citation2014). Altogether, this may lead to tension in the relationship with disagreement in how to cope and adjust, less engagement in prior social activities and loss of affection and intimacy (Davis, Gilliss, Deshefy-Longhi, Chestnutt, & Molloy, Citation2011; Martin, Citation2016). Discussion how PD symptoms affect different dimension of mutuality, may enhance the dyads’ understanding of each other. In addition to regular family meetings with clinicians, engagement in support groups or couple therapy may help dyads to accept, cope and find inner strength in order to adjust to a life with PD.

Limitations

We acknowledge that the present study has limitations. First, conclusion regarding causality cannot be made due to the cross-sectional design and the rather small sample size. We acknowledge that a sample of 51 dyads is rather small for running SEM. However, one advantage of using SEM compared to conventional regression analysis is that both direct and indirect effects are simultaneously calculated within the model instead of calculating several regression analyses and stepwise test direct and indirect effects. We also acknowledge that sample bias is a potential problem when majority of the participants are recruited from one hospital. This could be addressed by recruiting participants from multiple centers and settings in future studies. Second, using only disease related factors in the explored model do not allow a comprehensive view of other possible predictors, mediators or outcomes variables. Third, the sample had a predominance of elderly patients with mild to moderate PD which limits the generalizability. Thus, findings may not be relevant for younger and early-onset patients. Future research would benefit from a longitudinal design, have different PD contexts and include variables such as personal traits, coping mechanism, acceptance, adjustment and experience of support. Another outcome variable like HRQoL may also improve the possibility to detect risk dyads. Another future interesting direction would be to perform intervention studies aiming to maintain or improve mutuality by dyads. Nonetheless, the study is innovative in its attempt to look at both direct and indirect effects of mutuality. Furthermore, the results provide novel insight about PD symptoms’ association with mutuality and caregiver burden missing from the current larger body of knowledge. The results may also add useful knowledge that can be used in clinical settings helping health professionals improve caregivers’ wellbeing.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that when dependency and impaired cognition are present in family care situations, the experience of burden elevates because partners’ mutuality suffers. Neither motor nor NMS were associated with caregiver burden, instead motor symptoms decreased patients’ mutuality in turn leading to lower level of partners’ mutuality. However, we do acknowledge that more research is needed using longitudinal design and larger sample in different PD contexts. Nonetheless our findings enhance our understanding of the complexity of living with PD and provide novel insights of PD symptoms’ association with mutuality and caregiver burden which can be used in future studies helping health-professionals improve the wellbeing of PD dyads.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the participants

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article

Data availability

Due to ethical restrictions, raw data are not suitable for public deposition. Data are available upon request for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data.

Table 1. Sociodemographic and clinical features n = 51 dyads.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aarsland, D., Larsen, J. P., Karlsen, K., Lim, N. G., & Tandberg, E. (1999). Mental symptoms in Parkinson's disease are important contributors to caregiver distress. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 14(10), 866–874.

- Archbold, P., Stewart, B., Greenlick, M. R., & Harvath, T. A. (1992). The clinical assessment of mutuality and prepardness in family caregivers to frail older people. In S. G. Funk, E. M. Tornquist, M. T. Champagne, R. A. Wise (Eds.), Key aspects of elder care: Managing falls, incontinence, and cognitive impairment. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company.

- Archbold, P. G., Stewart, B. J., Greenlick, M. R., & Harvath, T. (1990). Mutuality and preparedness as predictors of caregiver role strain. Research in Nursing & Health, 13(6), 375–384. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/nur.4770130605/asset/4770130605_ftp.pdf?v=1&t=jcuo010l&s=00e529b98806646176734800b57e36a971549d5d

- Asberg, K. H., & Sonn, U. (1989). The cumulative structure of personal and instrumental ADL. A study of elderly people in a health service district. Scandinavian Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine 21(4), 171–177.

- Ball, V., Snow, A. L., Steele, A. B., Morgan, R. O., Davila, J. A., Wilson, N., & Kunik, M. E. (2010). Quality of relationships as a predictor of psychosocial functioning in patients with dementia. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 23(2), 109–114. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0891988710363709

- Birgersson, A. M., & Edberg, A. K. (2004). Being in the light or in the shade: persons with Parkinson's disease and their partners' experience of support. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 41(6), 621–630.

- Caap-Ahlgren, M., & Dehlin, O. (2002). Factors of importance to the caregiver burden experienced by family caregivers of Parkinson's disease patients. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 14(5), 371–377.

- Campbell, P., Wright, J., Oyebode, J., Job, D., Crome, P., Bentham, P., … Lendon, C. (2008). Determinants of burden in those who care for someone with dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(10), 1078–1085. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1002/gps.2071

- Carter, J. H., Stewart, B. J., Archbold, P. G., Inoue, I., Jaglin, J., Lannon, M., … Zoog, K. …. (1998). Living with a person who has Parkinson's disease: the spouse's perspective by stage of disease. Parkinson's Study Group. Movement Disorders, 13(1), 20–28. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/mds.870130108/asset/870130108_ftp.pdf?v=1&t=jcuo0wva&s=052bcc3c78e2e6370387c7fab7ab17f44dc0f08f

- Chaudhuri, K. R. (2011). Handbook of non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease. New York: NY: Springer.

- Chaudhuri, K. R., Martinez-Martin, P., Schapira, A. H. V., Stocchi, F., Sethi, K., Odin, P., … Olanow, C. W. (2006). International multicenter pilot study of the first comprehensive self-completed nonmotor symptoms questionnaire for Parkinson's disease: the NMSQuest study. Movement Disorders, 21(7), 916–923. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/mds.20844/asset/20844_ftp.pdf?v=1&t=jct7otol&s=58c0e77c2e7f125c2f7eaef6abc4071060ba5451 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/mds.20844/asset/20844_ftp.pdf?v=1&t=jct7p15e&s=a398fb3c81f4feb4cfe85c319422cd58bb4eb5fb

- Chiong-Rivero, H., Ryan, G. W., Flippen, C., Bordelon, Y., Szumski, N. R., Zesiewicz, T. A., … Vickrey, B. G. (2011). Patients' and caregivers' experiences of the impact of Parkinson's disease on health status. Patient Related Outcome Measures, 2011(2), 57–70.

- D'Amelio, M., Terruso, V., Palmeri, B., Di Benedetto, N., Famoso, G., Cottone, P., … Savettieri, G. (2009). Predictors of caregiver burden in partners of patients with Parkinson's disease. Neurological Sciences, 30(2), 171–174. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs10072-009-0024-z

- Davis, L. L., Gilliss, C. L., Deshefy-Longhi, T., Chestnutt, D. H., & Molloy, M. (2011). The nature and scope of stressful spousal caregiving relationships. Journal of Family Nursing, 17(2), 224–240. Retrieved from < Go to ISI>://WOS:000290027300006 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3839348/pdf/nihms525822.pdf

- Elmstahl, S., Malmberg, B., & Annerstedt, L. (1996). Caregiver's burden of patients 3 years after stroke assessed by a novel caregiver burden scale. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabiliation, 77(2), 177–182.

- Fahn, S., & Elton, R, & Committee., a. M. o. t. U. D. (1987). The Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale. In S. Fahn, C. D. Marsden, D. B. Calne, M. Goldstein (Eds.), Recent Developments in Parkinson’s Disease (Vol. 2, pp. 153–163, 293-304). Florham Park, NJ: Macmillan Health Care Information

- Fereshtehnejad, S. M. (2016). Strategies to maintain quality of life among people with Parkinson's disease: what works? Neurodegenerative Disease Management, 6(5), 399–415.

- Francis, L. E., Worthington, J., Kypriotakis, G., & Rose, J. H. (2010). Relationship quality and burden among caregivers for late-stage cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer, 18(11), 1429–1436. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2Fs00520-009-0765-5.pdf

- Ghielen, I., van Wegen, E. E. H., Rutten, S., de Goede, C. J. T., Houniet-de Gier, M., Collette, E. H., … van den Heuvel, O. A. (2017). Body awareness training in the treatment of wearing-off related anxiety in patients with Parkinson's disease: Results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 103, 1–8.

- Goldsworthy, B., & Knowles, S. (2008). Caregiving for Parkinson's disease patients: an exploration of a stress-appraisal model for quality of life and burden. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 63(6), P372–376.

- Greenwell, K., Gray, W. K., van Wersch, A., van Schaik, P., & Walker, R. (2015). Predictors of the psychosocial impact of being a carer of people living with Parkinson's disease: a systematic review. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders, 21(1), 1–11.

- Haahr, A., Kirkevold, M., Hall, E. O. C., & Ostergaard, K. (2013). Being in it together': living with a partner receiving deep brain stimulation for advanced Parkinson's disease - a hermeneutic phenomenological study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(2), 338–347. Retrieved from < Go to ISI>://WOS:000313722600010

- Halm, M. A., & Bakas, T. (2007). Factors associated with caregiver depressive symptoms, outcomes, and perceived physical health after coronary artery bypass surgery. Journal of Cardiovascular Nurses, 22(6), 508–515. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com/ovftpdfs/FPDDNCOBJEIKNG00/fs046/ovft/live/gv023/00005082/00005082-200711000-00015.pdf

- Hirschfeld, M. (1983). Homecare versus institutionalization: family caregiving and senile brain disease. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 20(1), 23–32.

- Hoehn, M. M., & Yahr, M. D. (2001). Parkinsonism: onset, progression, and mortality. 1967. Neurology, 57(10 Suppl 3), S11–S26.

- Hooker, S. A., Grigsby, M. E., Riegel, B., & Bekelman, D. B. (2015). The impact of relationship quality on health-related outcomes in heart failure patients and informal family caregivers: An integrative review. Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing, 30(4 Suppl 1), S52–S63. Retrieved from https://insights.ovid.com/pubmed?pmid=25955196

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60.

- Hsiao, C. Y., & Tsai, Y. F. (2014). Caregiver burden and satisfaction in families of individuals with schizophrenia. Nursing Research, 63(4), 260–269. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com/ovftpdfs/FPDDNCDCMCAIAE00/fs046/ovft/live/gv025/00006199/00006199-201407000-00006.pdf

- Jones, A. J., Kuijer, R. G., Livingston, L., Myall, D., Horne, K., MacAskill, M., … Dalrymple-Alford, J. C. (2017). Caregiver burden is increased in Parkinson's disease with mild cognitive impairment (PD-MCI). Translational Neurodegeneration, 6, 17. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5474856/pdf/40035_2017_Article_85.pdf

- Jorm, A. F. (2004). The Informant Questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE): a review. International Psychogeriatrics, 16(3), 275–293.

- Karlstedt, M., Fereshtehnejad, S.-M., Aarsland, D., & Lökk, J. (2018). Mediating effect of mutuality on health-related quality of life in patients with Parkinson's Disease. Parkinson’s Disease, 2018, 8. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9548681

- Karlstedt, M., Fereshtehnejad, S. M., Aarsland, D., & Lokk, J. (2017). Determinants of dyadic relationship and its psychosocial impact in patients with Parkinson's Disease and their spouses. Parkinsons Disease, 2017, 9. Retrieved from < Go to ISI>://WOS:000395197100001 http://downloads.hindawi.com/journals/pd/2017/4697052.pdf

- Karlstedt, M., Fereshtehnejad, S. M., Winnberg, E., Aarsland, D., & Lokk, J. (2017). Psychometric properties of the mutuality scale in Swedish dyads with Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 136(2), 122–128. Retrieved from < Go to ISI>://WOS:000404782500006 http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/ane.12706/abstract

- Lawrence, R. H., Tennstedt, S. L., & Assmann, S. F. (1998). Quality of the caregiver care recipient relationship: Does it offset negative consequences of caregiving for family caregivers? Psychology and Aging, 13(1), 150–158. Retrieved from < Go to ISI>://WOS:000072552200013

- Lokk, J. (2008). Caregiver strain in Parkinson's disease and the impact of disease duration. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine, 44(1), 39–45.

- Lokk, J. (2009). Reduced life-space of non-professional caregivers to Parkinson's disease patients with increased disease duration. Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery, 111(7), 583–587. Retrieved from < Go to ISI>://WOS:000269109700005 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S030384670900136X?via%3Dihub

- Lyons, K. S., Stewart, B. J., Archbold, P. G., & Carter, J. H. (2009). Optimism, pessimism, mutuality, and gender: predicting 10-year role strain in Parkinson's disease spouses. Gerontologist, 49(3), 378–387. Retrieved from https://watermark.silverchair.com/gnp046.pdf?token=AQECAHi208BE49Ooan9kkhW_Ercy7Dm3ZL_9Cf3qfKAc485ysgAAAd4wggHaBgkqhkiG9w0BBwagggHLMIIBxwIBADCCAcAGCSqGSIb3DQEHATAeBglghkgBZQMEAS4wEQQMCi7olb931GHOkwh8AgEQgIIBkXcqPzQkk2-5joPUbiS-MpSvXjTK2jaOWw2soT0PqBHWXTNOvEF0wIzDuNbrOuJQea_AgpK1z-vL1DdeaTsc6BfgQUPl4D68Vi4vzWQbwkGbS_WatTlydllxIoE9ebTIr6FkQEqbRpzT12U4U24eTUcFknuwkE3_OLFz4NZ9yaUMwuJ4S-vufNpo-HMMOG648BS8JS1SKvMxK3C_UjdPwf6NufWWd9JFnuGB3rb2HNIBRfwc2WYYFtxPzBmN09_UU_wQOq_2Nh_grFyt2KlBN-xJZ6oP7nCbFkv36pdVZoZNWjIXN1MdoTg6A3fqpX76fEfUkmBCjBCZs7F2fuWc03oO6OY-Cm_3LYjORS4NDw7UCE6hlP7OixDLkUimwOm7HVBmxMzzOZ7HU-jNdCx0I_AcvsH0ckQuJtvfiMpCH2OmLOjhMMKqofnzuyg8SefTIzypG_cql2NCWK1CZiy2tEFWq-TWoh6fntwLA5CkhbRL4KQJiyUI2rZ4HFv1lP3ITrnRNQbsjFJqwgwBrj8UaJu4

- Maffoni, M., Giardini, A., Pierobon, A., Ferrazzoli, D., & Frazzitta, G. (2017). Stigma experienced by Parkinson’s disease patients: A descriptive review of qualitative studies. Parkinson’s Disease, 2017, 1–7.

- Martin, S. C. (2015). Psychosocial challenges experienced by partners of people with Parkinson Disease. Journal of Neuroscience Nursing, 47(4), 211–222. Retrieved from http://ovidsp.tx.ovid.com/ovftpdfs/FPDDNCJCFCPLJE00/fs046/ovft/live/gv023/01376517/01376517-201508000-00005.pdf

- Martin, S. C. (2016). Relational issues within couples coping with Parkinson's disease: Implications and ideas for family-focused care. Journal of Family Nursing, 22(2), 224–251. Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1074840716640605?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pub%3dpubmed

- Martinez-Martin, P., Arroyo, S., Rojo-Abuin, J. M., Rodriguez-Blazquez, C., Frades, B., & de Pedro Cuesta, J. (2008). Burden, perceived health status, and mood among caregivers of Parkinson's disease patients. Movement Disorders, 23(12), 1673–1680. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/mds.22106/abstract

- Martinez-Martin, P., Forjaz, M. J., Frades-Payo, B., Rusinol, A. B., Fernandez-Garcia, J. M., Benito-Leon, J., … Catalan, M. J. (2007). Caregiver burden in Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders, 22(7), 924–931. quiz 1060.

- Martinez-Martin, P., Rodriguez-Blazquez, C., & Forjaz, M. J. (2012). Quality of life and burden in caregivers for patients with Parkinson's disease: concepts, assessment and related factors. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 12(2), 221–230. Retrieved from http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1586/erp.11.106?needAccess=true

- Martinez-Martin, P., Schapira, A. H. V., Stocchi, F., Sethi, K., Odin, P., MacPhee, G., … Chaudhuri, K. R. (2007). Prevalence of nonmotor symptoms in Parkinson's disease in an international setting; study using nonmotor symptoms questionnaire in 545 patients. Movement Disorders, 22(11), 1623–1629. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/mds.21586/asset/21586_ftp.pdf?v=1&t=jdn5634x&s=f12220f94e10e1b8504ba753781f663514df8787

- Mosley, P. E., Moodie, R., & Dissanayaka, N. (2017). Caregiver burden in Parkinson Disease: A critical review of recent literature. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 30(5), 235–252.

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891.

- Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations: Mediation analysis in social psychology. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 359–371.

- Santos-Garcia, D., & de la Fuente-Fernandez, R. (2015). Factors contributing to caregivers' stress and burden in Parkinson's disease. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica, 131(4), 203–210. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/ane.12305

- Schrag, A., Hovris, A., Morley, D., Quinn, N., & Jahanshahi, M. (2006). Caregiver-burden in Parkinson's disease is closely associated with psychiatric symptoms, falls, and disability. Parkinsonism and Related Disorders, 12(1), 35–41.

- Schrag, A., & Quinn, N. (2000). Dyskinesias and motor fluctuations in Parkinson's disease. A Community-Based Study. Brain, 123(Pt 11), 2297.

- Soleimani, M. A., Negarandeh, R., Bastani, F., & Greysen, R. (2014). Disrupted social connectedness in people with Parkinson's disease. British Journal of Community Nursing, 19(3), 136–141.

- Spruytte, N., Van Audenhove, C., & Lammertyn, F. (2001). Predictors of institutionalization of cognitively‐impaired elderly cared for by their relatives. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(12), 1119–1128.

- Tabachnick, B. G. (2012). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.) Boston, Mass. London: Boston, Mass.London: Pearson Education.

- Tanji, H., Anderson, K. E., Gruber-Baldini, A. L., Fishman, P. S., Reich, S. G., Weiner, W. J., & Shulman, L. M. (2008). Mutuality of the marital relationship in Parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders, 23(13), 1843–1849. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/store/10.1002/mds.22089/asset/22089_ftp.pdf?v=1&t=jcuo4b00&s=b17538eb010e7a7b474bbaf4ec967c660947f706

- Yates, M. E., Tennstedt, S., & Chang, B. H. (1999). Contributors to and mediators of psychological well-being for informal caregivers. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Science, 54(1), P12–22.

- Zhao, X. S., Lynch, J. G., & Chen, Q. M. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. Retrieved from < Go to ISI>://WOS:000279443600001