Abstract

Objectives: It is essential to develop interventions that meet individual needs for coping and self-management of people with dementia. This study explored the feasibility and applicability of an intervention merging methods of cognitive rehabilitation and self-management groups for people with early stage dementia. The potential of this intervention to promote adoption of assistive technology was also explored.

Method: People with early stage Alzheimer’s disease (N = 19) participated in the programme comprising both individual and group sessions. Caregivers were involved in the individual session and a separate group meeting. The intervention both addressed individual goals and more general self-management approaches. In addition, both participants and caregivers were introduced to the ReACT app, a holistic solution tailormade to meet self-management needs of people with early stage dementia.

Results: There was significant improvement in the participants’ attainment of individual goals and satisfaction with goal attainment from pre- to post-intervention. Participants and caregivers generally reported a positive attitude towards the intervention, attendance rate was high, and all participants completed the intervention. Qualitative results also indicated that the intervention promoted awareness, acceptance and coping among participants. The specific benefits of using the ReACT app for self-management were also emphasised. Forty-two percent of the participants adopted the app and continued using it after completing the intervention.

Conclusion: Results from this pilot study indicated that the intervention is both feasible and applicable and can be an effective method to promote coping and adoption of assistive technology among people with early stage dementia.

Introduction

The number of people living with dementia world-wide is fast growing and this generates an increasing demand for adequate and affordable solutions to meet the needs for support and care of those affected by dementia. Neurodegenerative dementia diseases cause progressive cognitive and functional decline, but the consequences of these symptoms can be reduced through timely and suitable interventions (Olazarán et al., Citation2010). It is essential that we develop and adopt interventions to support independence, quality of life and well-being of people living with dementia and to reduce the impact on supporters and society in general.

Various forms of assistive technology (AT) have potential to support cognitive functions and thereby promote self-management and functional independence of people living with dementia (King & Dwan, Citation2017; Meiland et al., Citation2017; Van der Roest, Wenborn, Pastink, Droes, & Orrell, Citation2017), and the number of AT solutions offered to people with dementia is fast increasing (Asghar, Cang, & Yu, Citation2017; Gibson et al., Citation2016). However, to provide adequate, efficient and evidence-based AT solutions for people with dementia there are several issues that need to be further addressed through research. Among these is the crucial need to find applicable and effective methods to deploy and adopt AT, bringing it into people’s everyday life (Kenigsberg et al., Citation2017; Meiland, et al., Citation2017).

To identify such applicable and effective methods, we can consider other successful methods of promoting self-management and coping among people with dementia and here both self-management groups (Quinn, Toms, Anderson, & Clare, Citation2016) and individualised reablement programmes (Poulos et al., Citation2017) seem relevant and applicable. They each represent different approaches to positive support and empowerment of people with dementia. Self-management groups target self-efficacy in a broader sense, addressing cognitive, psychological and social functioning, by combining elements like psychoeducation, problem solving and coping skills training (Mountain & Craig, Citation2012; Quinn et al., Citation2016). The group setting also promotes the benefits of sharing, socializing and learning from people in a similar situation, which is often put forward by people with dementia when expressing their preferences in relation to psychosocial interventions (Toms, Quinn, Anderson, & Clare, Citation2015; Øksnebjerg et al., Citation2018). Compared to this, reablement interventions, e.g. programmes of goal-oriented cognitive rehabilitation, target self-management from a person-centred and individualised approach (Clare, Citation2017; Poulos, et al., Citation2017). Both Self-management groups (Laakkonen et al., Citation2016; Martin et al., Citation2015; Quinn et al., Citation2016) and individualised reablement programmes (Clare, Citation2017; Clare et al., Citation2010; Hindle et al., Citation2018) have proven to be well suited as post-diagnostic interventions for people with early stage dementia, and effective ways to adopt coping strategies and compensatory aids and tools.

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, the potential of combining methods from group-based self-management programmes and individualised reablement methods into a group-based cognitive rehabilitation programme for people with early stage dementia has not been explored in any intervention studies. Integrating these methods could promote self-management, empowerment and coping skills by combining a person-centred and individualised approach with the benefits of peer-support and meaningful social activities. Furthermore, the possible benefits of deploying and adopting the use of AT though such a programme has not been explored. Such an integrated programme could reinforce the use of AT by offering a structured intervention involving both education and support from staff, and inspiration and support from peers.

The pilot study described in this paper is part of the research project ReACT (Rehabilitation in Alzheimer’s disease using Cognitive support Technology), which comprises a range of interacting components (Øksnebjerg, Woods, & Waldemar, in press). Consequently, the study design is based on the principles of the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions (Craig et al., Citation2008).

The development of the specific AT used here, the ReACT app, has been reported elsewhere (Øksnebjerg et al., in press). It was tailormade through an iterative user-involving process to meet the self-management needs of the end-users, people with early stage Alzheimer’s disease. The app was designed as a holistic solution, with a calendar system as a main feature, and combines a range of functionalities, mainly supporting various aspects of prospective and retrospective memory (ibid). The app was designed to be used on a touch screen tablet computer (iPad).

The aim of the current pilot study was to examine the feasibility and applicability of a group-based goal-oriented rehabilitation programme for people with early stage Alzheimer’s disease, and to explore if such a programme can be a suitable and effective way to deploy and adopt AT. In addition, the study also aimed to explore outcome measures that capture the aims of the intervention, to inform planning of future large-scale studies.

Methods

Participants

The study was conducted in three Danish memory clinics and participants were recruited from these clinics. Potential eligible participants who met the inclusion criteria were offered a short oral introduction to the study and written information when visiting the memory clinic, and they were subsequently contacted by telephone and invited to a screening interview with the staff conducting the intervention. Inclusion criteria were a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer´s disease according to the NIA-AA criteria for probable Alzheimer’s disease (McKhann et al., Citation2011) within the last 12 months, a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 23 or above (Folstein, Folstein, & McHugh, Citation1975) to include those with a mild degree of dementia, stability of prescribed anti-dementia or anti-depressant medications (stable doses at least one month prior to the start of the intervention), and they should be Danish-speaking. Exclusion criteria were severe psychiatric symptoms (e.g. severe depressive or psychotic symptoms), substance abuse, or a visual or hearing disability that could impede participation in the group-based activities or the use of a tablet computer. Participants were also required to have a caregiver who could support their participation in the programme. A caregiver was defined as a family member or a friend with whom they had face-to-face contact at least once a week. Since people with dementia were the primary participants in the intervention they are subsequently referred to as participants and the co-participating family caregivers are referred to as caregivers.

Twenty-four potential participants and their caregivers accepted the invitation to the screening interview. One participant withdrew after the screening interview and three more withdrew after the consecutive baseline visit. They all stated that they found the intervention programme too extensive. Twenty participants were enrolled, and all completed the intervention programme, but one participant died from an unrelated acute disorder before the final assessment. Hence data from nineteen participants could be analysed after the conclusion of the study. The study was conducted between December 2016 and June 2017.

Procedure

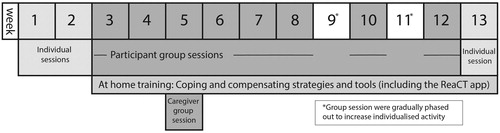

As illustrated in , the intervention programme included both individual and group-based activities and it was conducted over a period of 13 weeks.

Group sizes varied between three to seven participants. All activities were conducted by a clinical neuropsychologist, and two neuropsychologists were present at the group session, except in one group, where a neuropsychologist was assisted by a nurse specialised in dementia care.

There were two individual sessions with patient-caregiver dyads at the start of the programme and one individual session at the end of the programme. The two initial sessions were conducted with two objectives. The first objective was to identify the participants’ individual goals for the rehabilitation programme, in a collaboration between the participant, caregiver and staff. As outlined in the outcome measures section, a Danish version of the Bangor Goal Setting Interview (Clare et al., Citation2012) was used to define and assess these individual goals. The participant was encouraged to select a minimum of one and a maximum of three individual goals to be addressed during the programme. Participants and caregivers were of course informed that they would be introduced to the use of the ReACT app during the programme, but it was emphasised that it was not mandatory to define individual goals related to the use of the app. During the sessions there was also discussion of how the individual goals could be supported and achieved during the programme. The second objective of the individual sessions was to provide an introduction to the tablet and the ReACT app for the participant and the caregiver, and to provide initial instructions, support and inspiration of how to use the app.

At the individual session at the end of the programme the objectives were to carry out a final evaluation of the participants’ individual goals and to support continued activities related to these goals if relevant. The participants and caregivers who wanted to continue using the ReACT app after the programme were also given advice on this and information on post-intervention support. Between these individual sessions the participants attended eight two-hour weekly group sessions and caregivers attended one two-hour group session for caregivers.

The group sessions for participants comprised components from self-management group interventions (Quinn et al., Citation2016) including psychoeducation related to living with early stage Alzheimer’s disease and solution focused approaches to challenges in everyday life, including training of coping and compensation skills. The themes and activities were planned to target the participants’ individual goals, and the sessions included both group discussions and individualised activities. The use of the ReACT app as a compensatory tool was introduced as a potential solution when relevant, but using the app was not mandatory for participants. Between sessions participants were encouraged to practise coping and compensation skills at home, including the use of the app when relevant.

The session for caregivers provided information on the topics included in the group sessions for participants, and caregivers were also given advice on how to support transfer of knowledge and skills from the programme into home activities. During the entire programme the information presented to participants and caregivers was also made available in writing.

Both participants and caregivers had a tablet during the intervention programme with the ReACT app installed on it. Some off-the-shelf apps were also installed on the tablets, e.g. a news app, a weather forecast app, and an app for internet search. These were selected based on participants’ preferences and results from a previous pilot study, where criteria for selecting dementia friendly off-the-shelf apps were addressed (Øksnebjerg et al., in press). To reduce the complexity of operating the tablet a tailored device management system was installed on all the tablets, enabling the study team to simplify the layout of the screens and manage updates of the devices and apps. Participants and caregivers who wanted to continue using the app after the programme could choose whether to continue using the device from the study or have the ReACT app installed on a private device.

Outcome measures

Baseline and post-intervention outcome measures were obtained before and after the intervention programme. Post-intervention measures were obtained within two weeks after finalising the programme. Demographic information for both participants and caregivers was collected at baseline. Outcome measures were selected to capture the potential impacts of the intervention programme and to identify possible differences between participants who adopted the ReACT app during the intervention and continued using the app after the intervention (adoptors) and those who did not adopt the app (non-adoptors). Adoptors were defined as participants who continued using the app after finishing the intervention programme.

Primary outcome

Goal attainment was evaluated using a Danish translation of the Bangor Goal Setting Interview (BGSI) (Clare et al., Citation2012). Participants’ and caregivers’ evaluation of goal attainment was assessed on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 10, with 1 representing “Unable to carry out or perform task” and 10 representing “Able to carry out or perform task without difficulty”. Participants’ rating of satisfaction with goal attainment was also assessed on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 10, with 1 representing “Extremely dissatisfied with attainment” and 10 representing “Extremely satisfied with attainment”.

Secondary outcomes

Capability-related well-being was measured with the ICECAP-O (Coast et al., Citation2008). Scores range from 0 to 1, with higher scores indicating better well-being.

Activities of Daily Living were assessed using the Bayer Activities of Daily Living Scale (B-ADL) (Hindmarch, Lehfeld, de Jongh, & Erzigkeit, Citation1998). The main target group of this scale is community dwelling patients who have mild cognitive impairment or mild-to-moderate dementia and the scale is designed to be completed by a caregiver. The scale comprises 25 items and the caregiver was asked to rate if the participant had difficulty performing various daily activities on a 10-point Likert scale ranging from 1 “Never” to 10 “Always”. The total score was divided by the number of items rated, to correct for items replied to as irrelevant, and the score was rounded to two decimal places, giving total scores ranges between 1.00 and 10.00.

Health-related quality of life was measured by the EQ-5D-5L (EuroQol Group, Citation1990) and responses were converted to an index value between –0.624 and 1 (Van Hout et al., Citation2012), with 1 representing best possible health-related quality of life. The visual analogue scale (EQ-5D VAS) was also included. It has a range of 0 to 100, with 100 representing best-imagined health. These two health-related quality of life scales were both administered to participants and, as a proxy, to caregivers.

Cognitive outcome measures included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein, et al., Citation1975), Addenbrooke’s Cognitive Examination ACE (Mathuranath, Nestor, Berrios, Rakowicz, & Hodges, Citation2000), list learning and visual memory tests from the Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) (Randolph, Tierney, Mohr, & Chase, Citation1998). Symbol Digit Modalities Test (SDMT) (Smith, Citation1982), Trail A and B tests (Reitan, Citation1992), verbal fluency (number of animals and words beginning with S for 1 min) (Strauss, Sherman, & Spreen, Citation2006), and non-verbal fluency measured with the Five Point test (Lee, Loring, Newell, & McCloskey, Citation1994).

To obtain a nuanced evaluation of the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention programme a short semi-structured interview was conducted with both participants and caregivers during the final assessment. They were asked to give feedback on their experience of participating in the programme, and they were encouraged to give examples of both possible gains and needs or wishes that had perhaps not been met during the interventions. They were also invited to suggest changes to the programme that could be addressed in future studies. The data from the interviews were collected by note-taking.

Attendance rate was registered to support the assessment of acceptability.

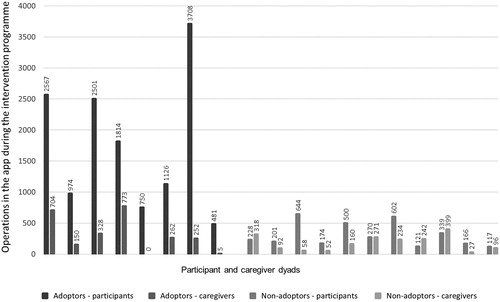

To monitor the use of the ReACT app during the intervention log data was collected to monitor the operations in the app performed by both participants and caregivers.

The usability and applicability of the ReACT app was rated with a modified version of the USE Questionnaire (Usefulness, Satisfaction, and Ease of use) (Lund, Citation2001). To make the scale applicable for people with dementia it was adapted and reduced from 30 to 12 items. Scores on each item range from 1 to 5 on a Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher ratings of usability and applicability. In this paper this version of the scale is referred to as the USE-dem questionnaire.

Data analyses

Quantitative data were analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics v.22. Baseline characteristics were explored with descriptive statistics. Possible changes in outcome measures were investigated through non-parametric analysis of change scores (Wilcoxon signed rank test).

Possible differences between baseline characteristics of adoptors and non-adoptors of the ReACT app were analysed using the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test or Fisher’s exact test as appropriate. The variation in the two groups’ use of the app during the intervention, assessed through log data, and their evaluation of the usability of the app, measured with the USE-dem questionnaire, were analysed using the Mann–Whitney U test. In addition, the changes in the two groups’ outcomes on the BGSI from baseline to post-intervention were analysed using mixed-design analysis of variance (split-plot ANOVA).

Tests of significance were performed two-tailed, with a significance level of 0.05 and a Bonferroni correction was applied to correct for multiple comparisons. Imputed values for missing data were calculated following standard procedures for multiple regression modelling.

The qualitative data from the interviews was inductively processed and summarised in emerging themes and subthemes, according to the principles of the Constant Comparison Analysis (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2007).

Results

Participants

The baseline characteristics for participants and caregivers are presented in . Most participants were female, their mean age was 67.5 years and their average education was 14.3 years. They were on average diagnosed 5.5 months before entering the study. Fifteen of the participants were living with their spouse, who participated as caregivers in the study. Four participants were living alone. One of them had a non-cohabiting partner and three of them had a friend who supported their participation in the study. Except for one participant, all the participants and caregivers were previous users of a smartphone and 12 of the participants and 11 of the caregivers were previous user of a tablet computer.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of participants and caregivers.

Impacts of the intervention programme

presents scores on outcome measures at baseline and post-intervention. Results show that there was a significant change in the participants’ evaluation of goal attainment (p < .001) and satisfaction with goal attainment (p = .001), whereas the caregivers’ evaluation of goal attainment did not change to a level that was statistically significant.

Table 2. Changes in outcome scores from baseline to post-intervention.

There were no statistically significant differences on the secondary outcome measures addressing well-being and level of performance in activities of daily living, however data did show a tendency towards an increase in participants’ self-rating of health-related quality of life at the end of the intervention, indicated by the EQ-5D-5L Index value (p = .033).

Among the secondary outcome measures addressing cognitive functions there were no significant changes, but a tendency to reduction on two of the tests, measuring categorial verbal fluency (p = .027) and list learning (p = .018).

Interviews

Results from the semi-structured interviews are summarized in , presenting themes, subthemes and related quotes. Both participants and caregivers generally gave positive feedback on participating in the programme. Many emphasised positive emotional reactions to participating, including the encouraging experience of meeting people in a similar situation, sharing their experience of living with dementia. Some participants also mentioned new relationships with other group members as a benefit. The shortcomings were related to the differences between group participants and some felt that the group did not match their personal skills. Participants also drew attention to issues that should be considered when developing further interventions, some of them requested longer breaks and more time for informal talks among participants.

Table 3. Results from interviews with participants and caregivers.

Most participants underlined that they had profited from gaining knowledge of their disease and for some this had led to increased awareness of symptoms and being more open to others about living with dementia. The interviews also indicated that participants and their caregivers had noticed specific activities related to self-management, coping and support that had been encouraged or promoted through the intervention programme, e.g. communicating with family and friends and being more organised with notetaking and reminders. In addition, specific benefits from learning how to use the tablet and the ReACT app was also discussed, e.g. using the electronic calendar and diary to support memory. However, some participants and caregivers also found it difficult or less beneficial to use the tablet and the app. The feedback that was specifically related to the app and suggested changes were collected and, if expedient, used to further optimize the app. This specific user feedback on app design and functionalities are not included in this paper.

Attendance during the programme

The attendance rate was in general high among both participants and caregivers. All participants attended the individual sessions. All the caregivers attended at least one of the initial individual sessions. In the group setting all participants attended at least six sessions, 14 of the participants participated in all sessions. The most common reasons for non-attendance were holidays and shorter periods of illness.

Differences between adoptors and non-adoptors of the ReACT app

As summarised in the quantitative data did not reveal any statistically significant differences in baseline characteristics between adoptors and non-adoptors of the ReACT app.

Table 4. Baseline differences between adoptors vs. non-adoptors of the ReACT app.

As mentioned it was not mandatory for participants to use the app or to define individual goals related to the use of the app. In total, 32 individual goals were defined among the participants. Nineteen of these goals were related to the use of the ReACT app (app-related goal), e.g. using the app to manage appointment and to-do lists or using the app to recollect precious moments with a grandchild by using photos and text in diary notes. Thirteen goals addressed other themes (non-app related goals), e.g. methods to support memory for choir lyrics or finding a system to support memory for various access codes. All participants defined at least one app-related goal, and four participants only defined app-related goals (three of them became adoptors and one of them a non-adoptor).

summarises the change in the two groups’ outcomes on the BGSI from baseline to post-intervention, including separate analyses for app-related goals and non-app related goals. These data show that the adoptors had a significantly larger change in rating of goal attainment for all goals compared to non-adoptors (p = .004). When separating these goals into app-related and non-app related goals there was no significant difference between the two groups, though there was a tendency for the app-related goal attainment to have a larger change from baseline to post-intervention for the group of adoptors (p = .068).

Table 5. Change in scores on the BGSI from baseline to post-intervention for adoptors and non-adoptors.

The differences between adoptors’ and non-adoptors’ use and rating of the ReACT app is summarised in . These data show that there was a significant difference in the number of operations in the app during the intervention performed by participants who adopted the app compared to those who did not adopt the app (p = .001), whereas there was no significant difference between the caregiver’s number of operations in the two groups (p = .741). These differences are also illustrated in where the total number of actions in the app during the intervention programme is summarised for each participant and caregiver dyad, and for adoptors and non-adoptors separately. The rating of usefulness, satisfaction, and ease of use the ReACT app as measured with the USE-dem questionnaire is also presented in . These data illustrate that adoptors rate the app significantly higher compared to non-adoptors (p < .001) and this is in line with the by-proxy rating conducted by the caregivers (p = .006), whereas the between group difference in the caregivers’ own rating of the app is not significant (p = .397).

Figure 2. Participant and caregiver dyads: Number of operations in the app during the intervention programme.

Table 6. Number of operations in the ReACT app and rating of the app.

Discussion

This pilot study aimed to explore the feasibility and applicability of an intervention merging methods of cognitive rehabilitation and self-management groups for people with early stage dementia to gain the best of both worlds and, in addition, to explore if this structured intervention is a feasible and effective way to encourage adoption of AT by people with dementia. To the best of the authors’ knowledge this study is the first to explore such a combined intervention and relating it to AT adoption.

The results demonstrated that our programme was generally feasible. Attendance rates were high and none of the participants dropped out after the initiation of the intervention.

The combination of methods from individual cognitive rehabilitation and group based self-management programmes appeared applicable. The qualitative data from interviews with participants and caregivers showed that they were generally positive towards the activities and methods applied during the programme.

Quantitative data confirmed that the programme was an applicable method to address individual goals of rehabilitation. The Bangor Goal Setting Interview (BGSI) (Clare et al., Citation2012) was used to define and assess the individual goals during the intervention. In line with other studies involving people with early stage dementia (Clare, Citation2017; Hindle, et al., Citation2018) participants in our study were in general able to identify individual goals in collaboration with caregivers and professionals and results confirmed that they experienced a significant improvement in their achievement of these goals during the intervention.

Qualitative data also supported the successful implementation of self-management features in the programme. Results from the interviews demonstrated that participants emphasised the benefits of meeting and sharing with peers in a similar situation. The utility of group-based psychoeducation, providing knowledge of disease and possible ways to cope with symptoms, was also highlighted. These results are in line with other studies published on self-management underlining the feasibility of such programmes to promote knowledge, independence and support, and having a positive impact on self-esteem (Martin, et al., Citation2015), quality of life (Sprange et al., Citation2015) and self-efficacy (Quinn, Toms, Jones, et al., Citation2016). Our results showed a tendency towards improvement in the participants’ rating of health-related quality of life.

Other small-scale studies have explored the adoption of cognitive supportive AT solutions similar to the ReACT app to people with dementia, both in a group-based setting (Dewar, Kapur, & Kopelman, Citation2018) and through individualised rehabilitation approaches (Imbeault et al., Citation2018), but with varied success. In our study, the combination of individual and group-based activities proved to be a feasible, applicable and efficient method to deploy AT. All participants accepted some degree of introduction to the app and forty-two percent of the participants adopted the app. The adoptors performed significantly more operations in the app during the intervention and they rated the app higher in usefulness, satisfaction, and ease of use compared to non-adoptors.

To be able to target future adoptors of this kind of AT, and to avoid adverse effects, e.g. non-adoptors feeling defeat or incompetence, we explored data to detect possible differences between adoptors and non-adoptors. The baseline characteristics did not reveal any significant differences between the two groups, though there was a tendency for adoptors to be slightly younger. The adoptors also had a significantly larger change in goal attainment during the intervention compared to non-adoptors. This could be ascribed to a larger success with app-related goals, which was of course unintended, as the intervention aimed to give equal attention to app-related and non-app related goals. These results and tendencies could indicate that there might be some factors that influence successful adoption of AT by people with dementia that were not fully captured in the outcome measures that were applied in this study. However, being an uncontrolled pilot study, the study was not designed or powered to detect significant differences in outcome measures, the assessments were conducted to explore outcome measures that could capture the aims of the intervention. Further large-scale studies are needed to identify possible predictive factors of AT adoption.

Study limitations and implications

In contrast to the participants’ evaluation of goal attainment, the caregiver’s evaluation did not change significantly during the intervention. The caregivers’ rating of goal attainment was relatively high at baseline, perhaps reflecting that participants were all newly diagnosed, and caregivers were maybe more optimistic about levels of functional ability at this time point. In order to provide psychoeducation and to promote coping and compensation, the consequences of living with dementia were highlighted during the intervention programme. It is possible that this increased focus on the participants’ ability to perform tasks and the assessment of ability and skills during the programme had a negative influence on caregiver’s evaluations, accentuating their focus on disabilities. This is also supported by the post-intervention increase in scores on the B-ADL, indicating that caregivers rated the participants to have a lower level of performance in activities of daily living. This could be viewed as an adverse effect of the intervention on caregivers. On the other hand, it also highlights the need to explore if the caregivers were adequately involved in the intervention and if they were provided enough information and support on how to be involved in coping and self-management as a caregiver. These questions must of course be addressed when planning future studies.

Another limitation is the skewed recruitment of participants. Despite efforts to recruit a varied group of people with early stage Alzheimer’s disease from the three memory clinics, a disproportionate part were woman. and they were all fairly well-educated. This might influence the generalizability of the results and a broader recruitment of participants should also be addressed in future studies.

In addition, the relevance of using cognitive tests among secondary outcomes in a self-management intervention programme can be questioned (Mountain, Citation2017), since the main goal of the intervention was to promote self-management and empowerment through positive support, including coping strategies and tools. However, in line with the MRC framework for the development and evaluation of complex interventions (Craig, et al., Citation2008) both the feasibility and applicability of intervention methods and outcome measures were explored in this pilot study. Cognitive outcome measures were applied to explore possible baseline differences among participants, and if possible to detect factors that could predict adoption of AT, but for future studies it should be considered to omit these cognitive outcome measures post-intervention to reduce the assessment burden for participants.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrated that a structured intervention programme addressing both individual goal-based rehabilitation and more general self-management approaches is feasible and applicable for people with early stage Alzheimer’s disease. In addition, results indicated that such a programme can be an effective method to promote adoption of AT. However, large-scale studies are needed to explore effective measures that capture the impact of the programme. Methods for deployment of the intervention at a larger scale and across multiple settings also need to be explored.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was evaluated by the regional scientific ethical committees of The Capital Region of Denmark (protocol number H-15005558), where it was decided the study did not need approval, since it was not considered to be within the framework of biomedical research.

All participants received oral and written information about the study objectives and methods. They all gave written informed consent.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the cooperation and great engagement of all participants, caregivers and professionals involved in the study, including staff from the memory clinics at Roskilde Hospital, Herlev Hospital and Rigshospitalet where the study was conducted.

Danish Dementia Research Centre is supported by the Danish Ministry of Health.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise research participants’ privacy and consent.

References

- Asghar, I., Cang, S., & Yu, H. (2017). Assistive technology for people with dementia: an overview and bibliometric study. Health Information & Libraries Journal, 34(1), 5–19.

- Clare, L. (2017). Rehabilitation for people living with dementia: A practical framework of positive support. PLoS Medicine, 14(3), e1002245

- Clare, L., Hindle, J. V., Jones, I. R., Thom, J. M., Nelis, S. M., Hounsome, B., & Whitaker, C. J. (2012). The AgeWell study of behavior change to promote health and wellbeing in later life: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 13(1), 115.

- Clare, L., Kudlicka, A., Oyebode, J. R., Jones, R. W., Bayer, A., Leroi, I., … Pool, J. (2019). Individual goal‐oriented cognitive rehabilitation to improve everyday functioning for people with early‐stage dementia: A multicentre randomised controlled trial (the GREAT trial. ). International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(5), 709–721.

- Clare, L., Linden, D. E. J., Woods, R. T., Whitaker, R., Evans, S. J., Parkinson, C. H., … Rugg, M. D. (2010). Goal-oriented cognitive rehabilitation for people with early-stage Alzheimer disease: a single-blind randomized controlled trial of clinical efficacy. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(10), 928–939.

- Coast, J., Flynn, T. N., Natarajan, L., Sproston, K., Lewis, J., Louviere, J. J., & Peters, T. J. (2008). Valuing the ICECAP capability index for older people. Social Science & Medicine, 67(5), 874–882.

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. Bmj, 337, a1655.

- Dewar, B.-K., Kapur, N., & Kopelman, M. (2018). Do memory aids help everyday memory? A controlled trial of a Memory Aids Service. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 28(4), 614–632.

- Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). “Mini-mental state”: a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198.

- Gibson, G., Newton, L., Pritchard, G., Finch, T., Brittain, K., & Robinson, L. (2016). The provision of assistive technology products and services for people with dementia in the United Kingdom. Dementia, 15(4), 681–701.

- EuroQol Group. (1990). EuroQol - a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 16(3), 199.

- Hindle, J. V., Watermeyer, T. J., Roberts, J., Brand, A., Hoare, Z., Martyr, A., & Clare, L. (2018). Goal‐orientated cognitive rehabilitation for dementias associated with Parkinson's disease―A pilot randomised controlled trial. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(5), 718–728.

- Hindmarch, I., Lehfeld, H., de Jongh, P., & Erzigkeit, H. (1998). The Bayer activities of daily living scale (B-ADL). Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 9(2), 20–26.

- Imbeault, H., Gagnon, L., Pigot, H., Giroux, S., Marcotte, N., Cribier-Delande, P., … Bier, N. (2018). Impact of AP@ LZ in the daily life of three persons with Alzheimer’s disease: long-term use and further exploration of its effectiveness. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 28(5), 755–778.

- Kenigsberg, P.-A., Aquino, J.-P., Bérard, A., Brémond, F., Charras, K., Dening, T., …., Innes, A. (2017). Assistive technologies to address capabilities of people with dementia: from research to practice. Dementia, 18(4), 1568–1595.

- King, A. C., & Dwan, C. (2017). Electronic memory aids for people with dementia experiencing prospective memory loss: A review of empirical studies. Dementia, 1–14. doi:10.1177/1471301217735180.

- Lee, G., Loring, D., Newell, J., & McCloskey, L. (1994). Figural fluency on the five-point test: preliminary normative and validity data. International Neuropsychological Society Program Abstract, 1, 51.

- Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2007). An array of qualitative data analysis tools: a call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(4), 557

- Lund, A. M. (2001). Measuring usability with the use questionnaire. Usability Interface, 8(2), 3–6.

- Laakkonen, M. L., Kautiainen, H., Hölttä, E., Savikko, N., Tilvis, R. S., Strandberg, T. E., & Pitkälä, K. H. (2016). Effects of self‐management groups for people with dementia and their spouses—Randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(4), 752–760.

- Martin, F., Turner, A., Wallace, L. M., Stanley, D., Jesuthasan, J., & Bradbury, N. (2015). Qualitative evaluation of a self-management intervention for people in the early stage of dementia. Dementia, 14(4), 418–435.

- Mathuranath, P., Nestor, P., Berrios, G., Rakowicz, W., & Hodges, J. (2000). A brief cognitive test battery to differentiate Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology, 55(11), 1613–1620.

- McKhann, G. M., Knopman, D. S., Chertkow, H., Hyman, B. T., Jack, C. R., Jr, Kawas, C. H., … Mayeux, R. (2011). The diagnosis of dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & Dementia, 7(3), 263–269.

- Meiland, F., Innes, A., Mountain, G., Robinson, L., van der Roest, H., García-Casal, J. A., …., Dröes, R.-M. (2017). Technologies to support community-dwelling persons with dementia: a position paper on issues regarding development, usability, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, deployment, and ethics. JMIR Rehabilitation and Assistive Technologies, 4(1), 1.

- Mountain, G. A. (2017). Self-management programme for people with dementia and their spouses demonstrates some benefits, but the model has limitations. Evidence Based Nursing, 20(1), 26–27.

- Mountain, G. A., & Craig, C. L. (2012). What should be in a self-management programme for people with early dementia?. Aging & Mental Health, 16(5), 576–583.

- Øksnebjerg, L., Diaz‐Ponce, A., Gove, D., Moniz‐Cook, E., Mountain, G., Chattat, R., & Woods, B. (2018). Towards capturing meaningful outcomes for people with dementia in psychosocial intervention research: A pan‐European consultation. Health Expectations, 21(6), 1056–1065.

- Øksnebjerg, L., Woods, B., & Waldemar, G. (in press). Designing the ReACT app to support self-management of people with dementia: An iterative user-involving process. Gerontology, doi:10.1159/000500445.

- Olazarán, J., Reisberg, B., Clare, L., Cruz, I., Peña-Casanova, J., del Ser, T., … Muñiz, R. (2010). Nonpharmacological therapies in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review of efficacy. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 30(2), 161–178.

- Poulos, C. J., Bayer, A., Beaupre, L., Clare, L., Poulos, R. G., Wang, R. H., … McGilton, K. S. (2017). A comprehensive approach to reablement in dementia. Alzheimer's & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 3(3), 450–458.

- Quinn, C., Toms, G., Anderson, D., & Clare, L. (2016). A review of self-management interventions for people with dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 35(11), 1154–1188.

- Quinn, C., Toms, G., Jones, C., Brand, A., Edwards, R. T., Sanders, F., & Clare, L. (2016). A pilot randomized controlled trial of a self-management group intervention for people with early-stage dementia (The SMART study). International Psychogeriatrics, 28(5), 787. p

- Randolph, C., Tierney, M. C., Mohr, E., & Chase, T. N. (1998). The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS): preliminary clinical validity. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 20(3), 310–319.

- Reitan, R. M. (1992). Trail Making Test: Manual for administration and scoring. Tucson, AZ: Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratory.

- Smith, A. (1982). Symbol digit modalities test. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services Los Angeles.

- Sprange, K., Mountain, G. A., Shortland, K., Craig, C., Blackburn, D., Bowie, P., … Spencer, M. (2015). Journeying through Dementia, a community-based self-management intervention for people aged 65 years and over: A feasibility study to inform a future trial. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 1(1), 42.

- Strauss, E., Sherman, E. M., & Spreen, O. (2006). A compendium of neuropsychological tests: Administration, norms, and commentary. New York, NY: American Chemical Society.

- Toms, G. R., Quinn, C., Anderson, D. E., & Clare, L. (2015). Help yourself: perspectives on self-management from people with dementia and their caregivers. Qualitative Health Research, 25(1), 87–98.

- van der Roest, H. G., Wenborn, J., Pastink, C., Droes, R. M., & Orrell, M. (2017). Assistive technology for memory support in dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 6, Cd009627.

- van Hout, B., Janssen, M. F., Feng, Y.-S., Kohlmann, T., Busschbach, J., Golicki, D., … Pickard, A. S. (2012). Interim scoring for the EQ-5D-5L: mapping the EQ-5D-5L to EQ-5D-3L value sets. Value in Health : The Journal of the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research, 15(5), 708–715.