Abstract

Objectives: With rates of dementia continuing to rise, the impetus on improving care for people with dementia is growing. Unmet needs of people with dementia living in nursing homes have been linked with worsening neuropsychiatric symptoms, higher levels of depression, and reduced quality of life. Furthermore, proxy accounts exploring the needs of people with dementia have frequently been shown to be unreliable. Therefore, this literature review aims to explore the self-reported needs and experiences of people with dementia in nursing homes.

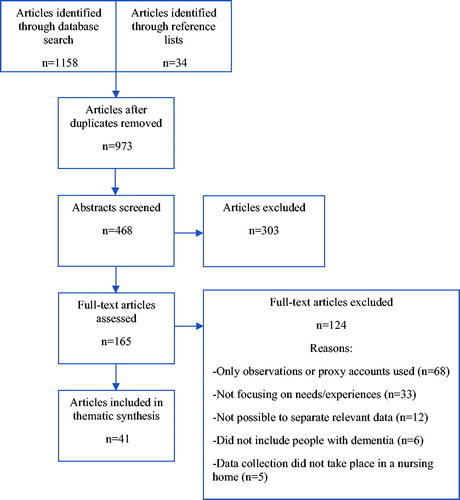

Method: A scoping review of the literature was carried out using the databases PubMed and PsycINFO to search for relevant articles according to PRISMA guidelines. Search terms were designed to include both quantitative and qualitative study designs. Thematic synthesis was used to categorise findings into themes related to self-reported needs and experiences.

Results: A total of 41 articles met the eligibility criteria. An analysis of study characteristics revealed more than half of studies used a qualitative design. Thematic synthesis resulted in eight themes: activities, maintaining previous roles, reminiscence, freedom and choice, appropriate environment, meaningful relationships, support with grief and loss, end-of-life care.

Conclusion: Whilst the voice of people with dementia has previously been neglected in research, this review has shown that people with dementia in nursing homes are able to describe their experiences and communicate their needs. The findings in this review have provided a contribution towards guiding evidence-based practice that is tailored to the needs of nursing home residents with dementia.

Introduction

Historically, people with dementia, and specifically those living in nursing homes, have been excluded from participation in research (Davies et al., Citation2014). Exclusion from research can be linked with the dominance of the biomedical model and an emphasis on developing pharmacological treatments for dementia. Consequently, researchers have frequently pursued a positivist-based paradigm of research, with participants playing a passive role in clinical trials (Bond & Corner, Citation2001). Furthermore, involving people with dementia in qualitative research has commonly been disregarded because of the association of dementia with ‘dwindling personhood’ (Moore & Hollett, Citation2003), and the view that associated communication and memory problems may affect an individual’s ability to share their experiences (Nygård, Citation2006).

In recent years, research into the needs and experiences of people with dementia living in nursing homes has been recognised as an increasingly valuable field (Milne, Citation2011). In the United Kingdom, approximately 70% of people living in nursing homes have dementia, which is often in the moderate to severe stages (Prince et al., Citation2014). Unmet needs of people with dementia living in nursing homes have been linked with worsening neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia (Cohen-Mansfield, Dakheel-Ali, Marx, Thein, & Regier, Citation2015), higher levels of depression (Hancock, Woods, Challis, & Orrell, Citation2006), and reduced quality of life (Hoe, Hancock, Livingston, & Orrell, Citation2006). However, research in this field has frequently relied on reports from family members and staff, despite evidence to suggest that proxy accounts are not always reliable (Crespo, Bernaldo de Quirós, Gómez, & Hornillos, Citation2012; Orrell et al., Citation2008). Therefore, eliciting the voice of people with dementia in research aimed at exploring their needs is essential for the production of evidence-based guidelines for care delivery in nursing homes, paving the way for improved quality of life amongst people with dementia (Sabat, Citation2003).

Although literature reviews exploring the self-reported needs of people with dementia have been carried out, these have focussed on those living in the community (Van der Roest et al., Citation2007; Von Kutzleben, Schmid, Halek, Holle, & Bartholomeyczik, Citation2012). One review by Cadieux, Garcia, and Patrick (Citation2013) looked at the needs of people with dementia in long-term care, using both proxy and subjective accounts. Their search included quantitative and qualitative studies published between 2000 and 2010. However, their search string did not include specific terms to identify subjective accounts, and consequently, some articles exploring subjective needs and experiences may have been overlooked. The aim of this scoping review therefore, is to explore the self-reported needs and experiences of people with dementia in nursing homes.

Method

Scoping review methodology

Due to the broad nature of the research question and the lack of current research in this area, the scoping review was selected as the appropriate methodology for this study (Peters et al., Citation2015). A scoping review has been described as a form of ‘knowledge synthesis’ and involves examining the nature and extent of research activity, which is important for determining gaps in the literature and directing future research (Colquhoun et al., Citation2014). For the purposes of this review, the six-stage framework as described by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) and adapted by Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien (Citation2010) has been used to guide the process.

Search strategy

Search strings were discussed amongst the authors (K.S & L.P) and with a librarian. They were then organised according to the PICOS model for constructing search strings for mixed-methods reviews (Methley, Campbell, Chew-Graham, McNally, & Cheraghi-Sohi, Citation2014). The databases PubMed and PsycINFO were used in the search, which took place during February and March 2018. The search was initially narrowed to include articles published between January 2000 and February 2018 in English, French or Czech, which resulted in a total of 1158 articles. shows the exact search string used for each database and the number of articles found.

Table 1. Exact search strings used for each database and number of articles found.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were initially decided upon by the authors (K.S & L.P) and reviewed during the search process by all authors. Articles of both quantitative and qualitative study designs exploring the self-reported needs and/or experiences of people with a diagnosis of any type of dementia living in a long-term care facility, such as a nursing home or residential home, were included. Those only involving participants with dementia living at home or in hospital were rejected, as well as studies involving only participants with mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or probable dementia. Studies where participants already had a confirmed diagnosis of dementia were included, as well as those where researchers assessed cognitive impairment using an appropriate test. Those studies using only proxy accounts or observational methods were not included, as these did not seek to obtain views of people with dementia themselves. Finally, conference reports, editorials, books, protocols and dissertations were rejected. The screening process was carried out in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Liberati et al., Citation2009), as shown in .

Critical appraisal

Critical appraisal in mixed methods reviews is currently a developing area. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) (Pace et al., Citation2012) was used as a general guide to assess the quality of articles of all study designs and to exclude any articles with fatal flaws. No studies were considered to warrant exclusion on this basis alone.

Data analysis

A convergent qualitative synthesis was carried out, enabling the transformation of both quantitative and qualitative data into qualitative findings (Pluye & Hong, Citation2014). In order to transform data, thematic synthesis as described by Thomas and Harden (Citation2008) was used. This involved firstly coding data inductively, according to both the category of needs and the category of experiences. For instance, a number of participants made reference to being bored and to repetitive days, and these topics formed initial codes under the category of experiences. In the second step, similar codes were merged into sub-themes wherever possible. In this case, codes were categorised into the sub-theme ‘boredom and monotony’. The same process was undertaken according to the category of needs.

The final stage of thematic synthesis requires the development of ‘analytical themes’, which address the research question directly. In this example, two authors (K.S & L.P) discussed, developed and sorted sub-themes to form the overarching analytical theme ‘activities’. Wherever possible, direct quotes from participants were used for data analysis, rather than the authors’ interpretation of what participants had said (Van Leeuwen et al., Citation2019).

Results

Study characteristics

A total of 41 studies were included in the final synthesis. The most commonly stated aims were to explore participants’: experiences (n = 14); quality of life (n = 10); perspectives (n = 5); perceptions (n = 4); preferences (n = 3); needs (n = 3); views (n = 3); self-report (n = 2); wellbeing (n = 1); priorities (n = 1); requirements (n = 1); and feelings (n = 1). Twenty-eight studies used a qualitative design, eight studies used a quantitative design, and five studies used mixed methods. Of the qualitative studies, the majority used interviews (n = 27), including semi-structured and unstructured or conversational interviews, and one study used focus groups. Of the quantitative studies, five were randomised controlled trials. A number of studies used various methods to collect additional data, including: proxy interviews or focus groups with family or staff (n = 15); observations (n = 12); proxy scale ratings or questionnaires completed by family or staff (n = 5); and data from medical notes (n = 7). A small number of studies (n = 4) used stimulus materials, such as photos, symbols or Talking Mats to aid participants’ communication during interviews. Finally, details about participants’ type of dementia were only described in a small number of studies (n = 10), whilst severity of dementia was more commonly described (n = 33), with approximately half of studies specifying that they included people with severe dementia (n = 20). In , we provide a summary of the individual studies.

Table 2. Summary of articles used in thematic synthesis.

Themes

Eight themes resulted from thematic synthesis: activities, maintaining previous roles, reminiscence, freedom and choice, appropriate environment, meaningful relationships, support with grief and loss, end-of-life care. shows the sub-themes according to both experiences and needs for each of the eight analytical themes.

Table 3. Specific experiences and needs according to each theme.

Activities

One of the most commonly occurring experiences of residents with dementia was boredom, with synonymous expressions such as ‘monotonous’ days (Harmer & Orrell, Citation2008) and ‘lack of stimulation’ (Aggarwal et al., Citation2003) also conveyed. The effects of boredom were spoken about by one resident who said: ‘I get bored here […] I feel like throwing something at them’ (Clare, Rowlands, Bruce, Surr, & Downs, Citation2008). Participants discussed a number of unstructured activities they enjoyed, such as crosswords, playing instruments, jigsaws, reading and knitting (Harmer & Orrell, Citation2008; Jonas-Simpson & Mitchell, Citation2005; Murphy, Tester, Hubbard, Downs, & MacDonald, Citation2005). However, many participants wished for ‘more social interaction’ (Popham & Orrell, Citation2012), and said that they take part in activities as a way of socialising with others (Tak, Kedia, Tongumpun, & Hong, Citation2015).

Preferred facilitated activities occurring in group settings included: music sessions (Mjørud, Engedal, Røsvik, & Kirkevold, Citation2017), dancing (Guzmán-García, Mukaetova-Ladinska, & James, Citation2013; Tak et al., Citation2015), bingo (Cahill & Diaz-Ponce, Citation2011); pet therapy (Travers, Perkins, Rand, Bartlett, & Morton, Citation2013), and group storytelling (George & Houser, Citation2014). A reading group was shown to increase feelings of belonging (Cooke, Moyle, Shum, Harrison, & Murfield, Citation2010), and residents experienced improvements in wellbeing (Conradsson, Littbrand, Lindelhöf, Gustafson, & Rosendahl, Citation2010) and increased mobility, independence and self-esteem from regular exercise classes (Olsen, Wiken Telenius, Engedal, & Bergland, Citation2015). Practicing of religion was also linked with improved quality of life (Dröes et al., Citation2006; Powers & Watson, Citation2011), with residents wishing to attend church services (Mjørud et al., Citation2017; Moyle, Fetherstonhaugh, Greben, Beattie, & AusQoL Group, Citation2015), and take part in ‘life-long religious practices’ within the home (Tak et al., Citation2015).

Activities should also be tailored to the individual (Moyle et al., Citation2015). Specific barriers to partaking in activities included deterioration in hearing and sight, arthritis, and lack of staff, transport and space in the home (Moyle et al., Citation2015; Tak et al., Citation2015). For those residents at a more advanced stage of dementia, engaging in ‘simple pleasures’, such as having an ice cream and a chat were described as enjoyable activities (Cahill & Diaz-Ponce, Citation2011).

Maintaining previous roles

A number of participants from various studies described feeling sad about the loss of roles, as portrayed by the following example: ‘I used to be a famous teacher, a psychologist, now I am nothing’ (Cohen-Mansfield, Golander, & Arnheim, Citation2000). Participants described feeling of ‘little value’ (Moyle et al., Citation2011), and many still had a desire to contribute to the home or society (Godwin & Poland, Citation2015; Jonas-Simpson & Mitchell, Citation2005). This could be achieved through engagement in domestic tasks such as tidying their rooms (Kaufmann & Engel, Citation2016). However, some participants were happy to be relieved of the responsibility of domestic tasks (Godwin & Poland, Citation2015; Van Zadelhoff, Verbeek, Widdershoven, Van Rossum, & Abma, Citation2011).

Altruism was also important for some residents, providing occupation, as well as comfort (Doyle, Rubinstein, & de Medeiros, Citation2015; Kaufmann & Engel, Citation2016). This may take place within the home, as explained by one participant, who said the best thing about her day was ‘chatting with other people, hearing their complaints and their worries and trying to give them a little advice’ (Moyle et al., Citation2015). This was echoed by other participants who said they cope better with their own situation by helping others (Clare et al., Citation2008). Residents also feel appreciated when staff asked for their knowledge about a subject (Graneheim & Jansson, Citation2006). Finally, one participant reported how being involved in altruistic activities benefitting the wider society, in this case crocheting baby clothes for hospitals, gave her ‘purpose in life’ (Tak et al., Citation2015).

Reminiscence

Reminiscence was described as a meaningful activity (Harmer & Orrell, Citation2008) and led to a sustained improvement in quality of life amongst participants in one trial (Serrani Azcurra, Citation2012), although these results were not replicated in a trial investigating reminiscence therapy and wellbeing (Haslam et al., Citation2010). Residents enjoy reminiscence sessions that involve staff, as they feel they are taking more of an interest in them, which in one study led to increased interaction during activities of daily living (Cooney et al., Citation2014). Residents also gain consolation from reflecting on things they have done in the past, which provides hope that life may be like that again (Kaufmann & Engel, Citation2016). Furthermore, reminiscence provides a means to reflect on things they can still do (Clare et al., Citation2008).

Tools for reminiscence included ‘photographs, recordings and newspaper clippings’ and subsequent group discussion (Serrani Azcurra, Citation2012). Films showing familiar places were enjoyed by some participants (Chung, Choi, & Kim, Citation2016). However, such reminders could bring back both happy and sad memories (Mjørud et al., Citation2017). In particular, photographs may remind individuals of what they have lost (Murphy et al., Citation2005).

Freedom and choice

As with boredom, an experience of a restriction was common. Residents described staff as ‘controlling’ (Moyle et al., Citation2011), and said that their quality of life would improve if they could do more of what they pleased (Dröes et al., Citation2006). When asked what they would like to do but were not allowed to, participants answered: music, going home, and attending family events (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2000). Lack of freedom to leave the home was noted as a source of frustration across a number of articles (Cahill & Diaz-Ponce, Citation2011; Goodman, Amador, Elmore, Machen, & Mathie, Citation2013; Milte et al., Citation2016; Popham & Orrell, Citation2012), and being prevented from simply going for a walk in the garden was associated with lower ratings of quality of life (Dröes et al., Citation2006). World War II veterans living in locked cognitive support units in one nursing home described them as prison camps (Wiersma & Pedlar, Citation2008); an experience echoed by a number of others residing in general nursing homes (Moyle et al., Citation2015; Olsen et al., Citation2015). However, in a home where the doors were not locked, one resident still felt restricted because staff did not have time to assist him to go outside (Heggestad, Nortvedt, & Slettebø, Citation2013).

Several participants experienced a sense of disempowerment (Moyle et al., Citation2011), and a lack of choice (Aggarwal et al., Citation2003) in other areas of their lives. Residents stated that they should have control over their daily routines and not have to fit in with ‘the status quo’ (Milte et al., Citation2016). This included choosing: what to eat (Aggarwal et al., Citation2003); whether to have a bath or shower (Murphy et al., Citation2005); which room to sit in (Popham & Orrell, Citation2012); and what time to go to bed (Jonas-Simpson & Mitchell, Citation2005). Residents would also like to prepare a drink or snack when they are hungry (Heggestad, Nortvedt, & Slettebø, Citation2013), with one participant suggesting that there should be a small kitchen in the home for their use (Popham & Orrell, Citation2012). Participants also wished to be respected as a person with individual preferences (Milte et al., Citation2016). For instance, in one study, although staff addressed almost all residents by their first name, only 70% of participants who expressed an opinion were happy with this (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2000).

Appropriate environment

There were varied reports as to whether nursing homes were a homely environment. Reasons for feeling ‘at home’ included living near family or near where they used to live, and good relationships with staff. Those with mild dementia were more inclined to consider a nursing home homely compared to those at a more advanced stage (Cahill & Diaz-Ponce, Citation2011). Participants discussed several needs in relation to their built environment, including the need to navigate areas without risk of falls (Dröes et al., Citation2006) or confusion, particularly for those at advanced stages of dementia (Bartlett, Citation2007). Participants also appreciated access to ‘personal space’ (Popham & Orrell, Citation2012), which promotes a sense of ownership (Moyle et al., Citation2015), and fulfils the need for time alone (Kaufmann & Engel, Citation2016). However, some residents lacked privacy and disliked that strangers could enter without permission (Dröes et al., Citation2006). As a result, some said they should be provided with a key (Milte et al., Citation2016; Heggestad, Nortvedt, & Slettebø, Citation2013). Within their rooms, family photos were important for combatting loneliness (Mjørud et al., Citation2017). When asked about other objects they would have liked to bring, participants mentioned: furniture, carpet, and plants (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2000).

The type of home may also play an important role in meeting individuals’ needs, such as group living homes, which were found to encourage interaction (Van Zadelhoff et al., Citation2011). As regards to the outdoor environment, participants wished for accessible external spaces (Moyle et al., Citation2011) and gardens (Bartlett, Citation2007), which were found to be important in maintaining independence and ownership (Moyle et al., Citation2015). Green care farms were also explored. However, no statistically different quality of life scores were found when green care farms were compared with traditional nursing homes or small-scale living facilities (De Boer, Hamers, Zwakhalen, Tan, & Verbeek, Citation2017).

Meaningful relationships

A number of participants spoke about the importance of relationships, and gaining comfort through human contact (Kaufmann & Engel, Citation2016). Fear of loneliness was discussed, specifically amongst those residents with advanced dementia (Cahill & Diaz-Ponce, Citation2011; Mjørud et al., Citation2017). In one study, a male participant highlighted how as a man it was harder to make friends, partly because there were a lot more women in the home (Moyle et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, in one dementia specific unit, no residents reported having a friendship within their unit, compared with non-dementia specific units (Casey, Low, Jeon, & Brodaty, Citation2016). Participants frequently described frustrations with fellow residents, disliking how they shout or hurt others (Bartlett, Citation2007; Murphy et al., Citation2005; Wiersma & Pedlar, Citation2008). Some residents felt that routines kept in the home were not conducive to forming friendships, as most went to bed early (Moyle et al., Citation2011).

As regards to relationships with staff, Cahill and Diaz-Ponce (Citation2011) found that they are especially important for those with mild-moderate dementia. Some residents described positive relationships with staff (Mjørud et al., Citation2017). However, others described their relationships as ‘economic’ (Bartlett, Citation2007), and said that staff could be difficult to find, manhandled them, and treated them like patients (Goodman et al., Citation2013; Milte et al., Citation2016). Relationships with family also continue to be significant (Dröes et al., Citation2006; Harmer & Orrell, Citation2008; Tak et al., Citation2015). Spending time with family provided opportunities for ‘meaningful conversations’, as well as reminding individuals about their existence outside of the care setting (Moyle et al., Citation2011). Losing contact with family was mentioned as a ‘key source of anxiety’ for residents, particularly when first moving into the home, and they may require staff to assist them to maintain contact (Milte et al., Citation2016), including through the use of Skype (Moyle et al., Citation2015). Participants felt that their families were not visiting them enough, which was particularly common amongst those at an advanced stage of dementia, who often wrongly believed family had not visited them when they had (Cahill & Diaz-Ponce, Citation2011).

Finally, a small number of participants talked about how they missed intimacy (Bauer et al., Citation2013; Dröes et al., Citation2006). In one study, nursing homes were not considered to be conducive to expressions of sexuality, with residents fearing negative reactions from staff and gossip. Residents found talking to staff about sexual needs too personal, and viewed staff as ‘strangers’ (Bauer et al., Citation2013).

Support with grief and loss

Individuals residing in a nursing home are likely to experience the loss of fellow residents. However, Tan, O’Connor, Howard, Workman, and O’Connor (Citation2013) found that 70% of residents with mild dementia in their study were not concerned about being around people dying. Instead, they were unhappy about not being told about the death of a resident, and felt that all residents should be informed together. As regards to funerals, 40% of participants in this study indicated that they would have liked to have attended a funeral of a resident they were close to. Furthermore, participants appreciated the idea of an afternoon tea in memory of residents who had died.

Residents may also experience loss in regards to their former lives and identities (Cahill & Diaz-Ponce, Citation2011; Mjørud et al., Citation2017). A number of participants expressed confusion and fear about why they were in the nursing home (Clare et al., Citation2008). Others wished to go home, with one participant describing how she had taken to walking down corridors so she would become strong enough to live with her daughter (Goodman et al., Citation2013). Other residents disliked living in the home so much that they felt they had no future, with three residents in one study saying that they wished for their lives to end. Notably, two of these residents said that they had not been able to talk this way with anyone except the researcher (Goodman et al., Citation2013). However, Thein, D’Souza, and Sheehan (Citation2011) found that most of the 18 participants they interviewed after their move liked their new homes, which was in part linked with having undertaken a pre-move visit, as well as having a ‘known person in the home’.

Participants also described a ‘loss of function’, leading to a ‘loss of purpose’. For instance, a decline in physical independence led one resident to express: ‘I can’t help anybody else in here, what’s the point of it all’ (Goodman et al., Citation2013). Support for residents may be provided in the form of a pastor (Powers & Watson, Citation2011) or other ‘spiritual rituals’ (Kaufmann & Engel, Citation2016), which were identified as providing comfort during difficult times.

End-of-life care

Needs at the end of life were explored in two studies. Mulqueen and Coffey (Citation2017) found that, amongst six participants with mild dementia, comfort and peace were ranked most important at this stage. Participants wished to be ‘pain free, worry free’ at the end of their lives, with ‘quiet and peaceful surroundings’. This included not being moved to hospital. Presence of family was ranked second in importance, followed by ‘my own things’, where participants said being in their own room surrounded by familiar items, such as family photos, would provide comfort. Fourthly, residents highlighted the need for effective communication, hoping that staff would not withdraw from them. In particular, residents would like familiar staff to care for them.

Goodman et al. (Citation2013) qualitatively explored the preferences of 18 residents with dementia for end-of-life care. There were mixed feelings regarding place of death, with one resident expressing preference for the nursing home. However, another said that she would prefer to go to hospital as she felt that there people ‘especially take an interest in your feelings’. As regards to religious needs, one resident said he would like to see a priest. Another participant emphasised that she would prefer to talk to a particular staff member about any concerns she may have, more so than her children, who she worried about upsetting.

Residents with dementia may also have varying needs as regards to pain relief. Although it was not specified whether participants were receiving end-of-life care, Monroe et al. (Citation2014) found that nursing home residents with dementia reported more intense levels of pain than those without dementia. However, participants were less likely to tell staff about pain, and less likely to report that nursing home staff asked about their pain.

Discussion

This scoping review provides new evidence concerning the needs and experiences of people with dementia in nursing homes, a previously underrepresented population in research. One of the most commonly occurring needs in the literature was the need for activities. However, participants emphasised the need for activities that are tailored to their abilities and interests. This is a challenge for nursing homes where often ‘personal preferences are constrained by the needs of others’ (Bruce & Schweitzer, Citation2008). Obtaining a life history when an individual first moves into the home has been suggested to ensure all aspects of care are personalised. This should be followed by a thoughtful approach to replicating activities, in a way that evokes ‘the “feel” of an activity enjoyed in the past, without engendering any anxiety about performance’ (Bruce & Schweitzer, Citation2008).

One particular activity explored in the literature was reminiscence. There was conflicting evidence regarding the impact of this activity on quality of life and wellbeing. Schweitzer and Bruce (Citation2008) propose a ‘creative communication-based approach’ to reminiscence, underpinned by a person-centred philosophy. For instance, this approach involves listening to individuals tell their stories in a respectful manner, and avoiding questioning information that may seem factually incorrect.

The need for freedom was another common theme amongst participants in this review. In particular, low quality of life ratings were linked with a lack of access to the outdoor environment. Although restricting access to the outdoor environment reduces risk from a staff perspective, it limits activities and prevents the ‘possibility of building relationships which might enhance the person’s life’ (Fossey, Citation2008). Furthermore, access to the outdoor environment has been shown to have a number of health benefits for people with dementia, including reducing neuropsychiatric symptoms (Heyn, Abreu, & Ottenbacher, Citation2004), restoring circadian rhythm, and increasing levels of vitamin D (Pollock & McMair, Citation2012), linked with a reduction in falls (Bischoff-Ferrari et al., Citation2009). One potential solution to this dilemma is to introduce ‘dementia-friendly outdoor environments’ (Mitchell & Burton, Citation2006). Preliminary recommendations for which include environments that are ‘familiar, legible, distinctive, accessible, comfortable and safe’ (Mitchell & Burton, Citation2006). For example, flat paving and regular seating intervals.

Under the theme of ‘meaningful relationships’, frustrations with fellow residents, and staff were described, as well as a loss of contact with communities and families. These findings may suggest the need for a movement towards ‘relationship-centred care’, as explored by Nolan, Keady, and Aveyard (Citation2001), who argue that relationships play an important role in determining quality of life, in particular by maintaining ‘identity and personhood’ (Davies & Nolan, Citation2008). Participants also described feeling unable to talk to staff about sexual needs. In their study exploring the attitudes of nursing home staff, Ward, Vass, Aggarwal, Garfield, and Cybyk (Citation2005) found that staff commonly avoid this topic during the assessment process as they find it ‘problematic’. The authors suggest that staff should be trained in how to broach this topic, and develop an understanding of the way in which sexuality forms an important part of personhood.

As regards to end-of-life care, only two studies in this review specifically addressed this area of need, and in both studies, there were mixed opinions amongst participants about the preferred place of death. This stresses the requirement for future wishes to be discussed, which may take the form of advance care planning (ACP), a process where patients determine their preferences for future care (Robinson et al., Citation2012). ACP has been shown to reduce inappropriate hospitalisations for people with dementia. However, the ACP process should be commenced in the early stages of dementia before loss of capacity (Robinson et al., Citation2012).

Implications

This study has shown that people with dementia in nursing homes, including those at a more advanced stage, are able to voice their experiences and needs, which has implications for education, practice and policy in the domain of dementia care planning, provision and evaluation in this setting. Firstly, wherever possible, nursing homes should involve people with dementia in the planning of their care at all stages, including for end of life. Furthermore, the themes and sub-themes presented in this paper have provided a possible evidence-based framework to guide nursing homes in the process of person-centred assessment and care planning for people with dementia. Thirdly, people with dementia should be given the opportunity to contribute to the evaluation of their care.

Future research

This study has also provided a means to identify gaps in the literature and future research priorities. More research addressing the needs of this population in relation to reminiscence, sexuality and intimacy, and end-of-life care is required. Furthermore, only one study specifically exploring the spiritual needs of people with dementia was identified. Spiritual needs have been found to be neglected in research, despite the role that spirituality has been shown to play in providing a source of comfort for people with dementia, and the way in which spiritual needs determine a range of other needs, such as end-of-life care (Higgins, Citation2013).

Secondly, due to the broad nature of dementia, needs of individuals according to various types, as well as stages of the condition should be explored. Finally, as regards to methods used in the studies, observations and proxy accounts were commonly used to complement self-reports. Although it has been said that triangulation increases confidence in drawing conclusions from data in dementia research (Black & Rabins, Citation2007), the researcher should consider that different sources of data may actually introduce ‘different perspectives’ (Nygård, Citation2006). provides a brief description of methods and additional tools used to collect data. However, a review exploring methods used to elicit the experiences and needs of people with dementia in more detail could provide a valuable source of information for researchers developing their own studies in this area.

Limitations

Only two databases were used to search for articles, hence some articles may have been missed, including grey literature. Restriction to articles in English, French and Czech may also mean that results are more representative of a European or Western perspective.

Conclusion

With rates of dementia continuing to rise, the impetus on improving care for this population is growing. Whilst the voice of people with dementia has previously been neglected in research, this review has shown that people with dementia in nursing homes are able to describe their experiences and communicate their needs. A total of eight themes were identified across the articles used in this scoping review, providing evidence that people with dementia have a wide variety of needs which, as developed by Kitwood (Citation1997), span significantly further than physical needs alone, to include psychosocial and environmental needs. However, this review is only a starting point towards guiding evidence-based practice, and has highlighted a number of gaps in the literature. In particular, further research is required to investigate needs according to the type and stage of dementia, as well as needs in relation to reminiscence, sexuality, spirituality, and end-of-life care for people with dementia in nursing homes.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Katrien Alewaters, librarian at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, and the End-of-Life Care Research Group, also at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel, for their input in designing the search string.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aggarwal, N., Vass, A. A., Minardi, H. A., Ward, R., Garfield, C., & Cybyk, B. (2003). People with dementia and their relatives: Personal experiences of Alzheimer’s and of the provision of care. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 10(2), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2850.2003.00550.x.

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Bartlett, R. (2007). ‘You can get in alright but you can’t get out.’ Social exclusion and men with dementia in nursing homes: Insights from a single case study. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 8(2), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1108/14717794200700009.

- Bauer, M., Fetherstonhaugh, D., Tarzia, L., Nay, R., Wellman, D., & Beattie, E. (2013). ‘I always look under the bed for a man’. Needs and barriers to the expression of sexuality in residential aged care: The views of residents with and without dementia. Psychology and Sexuality, 4(3), 296–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2012.713869.

- Bischoff-Ferrari, H. A., Dawson-Hughes, B., Staehelin, H. B., Orav, J. E., Stuck, A. E., Theiler, R., …, Henschkowski, J. (2009). Fall prevention with supplemental and active forms of vitamin D: A meta-analysis of randomised control trials. British Medical Journal, 339, b3692. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b3692.

- Black, B. S., & Rabins, P. V. (2007). Qualitative research in psychogeriatrics. International Psychogeriatrics, 19(02), 167–173. https://doi:10.1017/S1041610206004534.

- Bond, J., & Corner, L. (2001). Researching dementia: Are there unique methodological challenges for health services research? Ageing & Society, 21(1), 95–116. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X01008091.

- Bruce, E., & Schweitzer, P. (2008). Working with life history. In M. Downs & B. Bowers (Eds.), Excellence in dementia care (pp. 168–186). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Cadieux, M. A., Garcia, L. J., & Patrick, J. (2013). Needs of people with dementia in long-term care. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementiasr, 28(8), 723–733. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317513500840.

- Cahill, S., & Diaz-Ponce, A. M. (2011). ‘I hate having nobody here. I’d like to know where they all are’: Can qualitative research detect differences in quality of life among nursing home residents with different levels of cognitive impairment? Aging & Mental Health, 15(5), 562–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2010.551342.

- Casey, A.-N. S., Low, L.-F., Jeon, Y.-H., & Brodaty, H. (2016). Residents perceptions of friendship and positive social networks within a nursing home. The Gerontologist, 56(5), 855–867. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnv146.

- Chung, J., Choi, S.-I., & Kim, J. (2016). Experience of media presentations for the alleviation of agitation and emotional distress among dementia patients in a long-term nursing facility. Dementia, 15(5), 1021–1033. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214550660.

- Clare, L., Rowlands, J., Bruce, E., Surr, C., & Downs, M. (2008). The experience of living with dementia in residential care: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. The Gerontologist, 48(6), 711–720. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/48.6.711.

- Cohen-Mansfield, J., Dakheel-Ali, M., Marx, M. S., Thein, K., & Regier, N. G. (2015). Which unmet needs contribute to behaviour problems in persons with advanced dementia? Psychiatry Research, 228(1), 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2015.03.043.

- Cohen-Mansfield, J., Golander, H., & Arnheim, G. (2000). Self-identity in older persons suffering from dementia: Preliminary results. Social Science & Medicine, 51(3), 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00471-2.

- Colquhoun, H. L., Levac, D., O’Brien, K. K., Straus, S., Tricco, A. C., Perrier, L., … Moher, D. (2014). Scoping reviews: Time for clarity in definition, methods, and reporting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(12), 1291–1294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.03.013.

- Cooke, M., Moyle, W., Shum, D., Harrison, S., & Murfield, J. (2010). A randomized controlled trial exploring the effect of music on quality of life and depression in older people with dementia. Journal of Health Psychology, 15(5), 765–776. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105310368188.

- Conradsson, M., Littbrand, H., Lindelhöf, N., Gustafson, Y., & Rosendahl, E. (2010). Effects of a high-intensity functional exercise programme on depressive symptoms and psychological well-being among older people living in residential care facilities: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. Aging & Mental Health, 14(5), 565–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860903483078.

- Cooney, A., Hunter, A., Murphy, K., Casey, D., Devane, D., Smyth, S., … O’Shea, E. (2014). ‘Seeing me through my memories’: A grounded theory study on using reminiscence with people with dementia living in long-term care. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(23-24), 3564–3574. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12645.

- Crespo, M., Bernaldo de Quirós, M., Gómez, M. M., & Hornillos, C. (2012). Quality of life of nursing home residents with dementia: A comparison of perspectives of residents, family, and staff. The Gerontologist, 52(1), 56–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr080.

- Davies, S., & Nolan, M. (2008). Attending to relationships in dementia care. In M. Downs & B. Bowers (Eds.), Excellence in dementia care (pp. 438–454). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Davies, S. L., Goodman, C., Manthorpe, J., Smith, A., Carrick, N., & Iliffe, S. (2014). Enabling research in care homes: An evaluation of a national network of research ready care homes. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14(1), 47. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-47.

- De Boer, B., Hamers, J. P. H., Zwakhalen, S. M. G., Tan, F. E. S., & Verbeek, H. (2017). Quality of care and quality of life of people with dementia living at green care farms: A cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-017-0550-0.

- Doyle, P. J., Rubinstein, R. L., & de Medeiros, K. (2015). Generative acts of people with dementia in a long-term care setting. Dementia, 14(4), 409–417. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301213498246.

- Dröes, R.-M., Boelens-Van Der Knoop, E. C. C., Bos, J., Meihuizen, L., Ettema, T. P., Gerritsen, D. L., … SchöLzel-Dorenbos, C. J. M. (2006). Quality of life in dementia in perspective: An explorative study of variations in opinions among people with dementia and their professional caregivers, and in literature. Dementia, 5(4), 533–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301206069929.

- Fossey, J. (2008). Care homes. In M. Downs & B. Bowers (Eds.), Excellence in dementia care (pp. 336–358). Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- George, D. R., & Houser, W. S. (2014). “I’m a storyteller!”: Exploring the benefits of a timeslips creative expression program at a nursing home. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementiasr, 29(8), 678–684. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317514539725.

- Godwin, B., & Poland, F. (2015). Bedlam or bliss? Recognising the emotional self-experience of people with moderate to advanced dementia in residential and nursing care. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 16(4), 235–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAOA-08-2015-0038.

- Goodman, C., Amador, S., Elmore, N., Machen, I., & Mathie, E. (2013). Preferences and priorities for ongoing and end-of-life care: A qualitative study of older people with dementia resident in care homes. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 50(12), 1639–1647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.06.008.

- Graneheim, U. H., & Jansson, L. (2006). The meaning of living with dementia and disturbing behaviour as narrated by three persons admitted to a residential home. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15(11), 1397–1403. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01476.x.

- Guzmán-García, A., Mukaetova-Ladinska, E., & James, I. (2013). Introducing a Latin ballroom dance class to people with dementia living in care homes, benefits and concerns: A pilot study. Dementia, 12(5), 523–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301211429753.

- Hancock, G. A., Woods, B., Challis, D., & Orrell, M. (2006). The needs of older people with dementia in residential care. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(1), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1421.

- Harmer, B. J., & Orrell, M. (2008). What is meaningful activity for people with dementia living in care homes? A comparison of the views of older people with dementia, staff and family carers. Aging & Mental Health, 12(5), 548–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860802343019.

- Haslam, C., Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., Bevins, A., Ravenscroft, S., & Tonks, J. (2010). The social treatment: The benefits of group interventions in residential care settings. Psychology and Aging, 25(1), 157–167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018256.

- Heggestad, A. K. T., Nortvedt, P., & Slettebø, A. (2013). ‘Like a prison without bars’: Dementia and experiences of dignity. Nursing Ethics, 20(8), 881–892. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733013484484.

- Heyn, P., Abreu, B. C., & Ottenbacher, K. J. (2004). The effects of exercise training on elderly persons with cognitive impairment and dementia: A meta-analysis. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 85(10), 1694–1704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2004.03.019.

- Higgins, P. (2013). Meeting the religious needs of residents with dementia. Nursing Older People, 25(9), 25–29. https://doi.org/10.7748/nop2013.11.25.9.25.e501.

- Hoe, J., Hancock, G., Livingston, G., & Orrell, M. (2006). Quality of life of people with dementia in residential care home. British Journal of Psychiatry, 188(5), 460–464. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007658.

- Jonas-Simpson, C., & Mitchell, G. J. (2005). Giving voice to expressions of quality of life for persons living with dementia through story, music, and art. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly, 6(1), 52–61. http://hdl.handle.net/10315/13759.

- Kaufmann, E. G., & Engel, S. A. (2016). Dementia and well-being: A conceptual framework based on Tom Kitwood’s model of needs. Dementia, 15(4), 774–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214539690.

- Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., … Moher, D. (2009). The Prisma statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLOS Medicine, 6(7), e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

- Methley, A. M., Campbell, S., Chew-Graham, C., McNally, R., & Cheraghi-Sohi, S. (2014). PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 579. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0.

- Milne, A. (2011). Living with dementia in a care home: Capturing the experiences of residents. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 12(2), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.1108/14717791111144687.

- Milte, R., Shulver, W., Killington, M., Bradley, C., Ratcliffe, J., & Crotty, M. (2016). Quality in residential care from the perspective of people living with dementia: The importance of personhood. Archives in Gerontology and Geriatrics, 63, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2015.11.007.

- Mitchell, L., & Burton, E. (2006). Neighbourhoods for life. Designing dementia-friendly outdoor environments. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 7(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1108/14717794200600005.

- Mjørud, M., Engedal, K., Røsvik, J., & Kirkevold, M. (2017). Living with dementia in a nursing home, as described by persons with dementia: A phenomenological hermeneutic study. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2053-2.

- Monroe, T. B., Misra, S. K., Habermann, R. C., Dietrich, M. S., Cowan, R. L., & Simmons, S. F. (2014). Pain reports and pain medication treatment in nursing home residents with and without dementia. Geriatrics & Gerontology International, 14(3), 541–548. https://doi.org/10.1111/ggi.12130.

- Moore, T. F., & Hollett, J. (2003). Giving voice to persons with dementia: The researcher’s opportunities and challenges. Nursing Science Quarterly, 16(2), 163–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318403251793251793.

- Moyle, W., Fetherstonhaugh, D., Greben, M., Beattie, E, & AusQoL Group. (2015). Influencers on quality of life as reported by people living with dementia in long-term care: A descriptive exploratory approach. BMC Geriatrics, 15(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0050-z.

- Moyle, W., Venturto, L., Griffiths, S., Grimbeek, P., McAllister, M., Oxlade, D., & Murfield, J. (2011). Factors influencing quality of life for people with dementia: A qualitative perspective. Aging & Mental Health, 15(8), 970–977. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2011.583620.

- Mulqueen, K., & Coffey, A. (2017). Preferences of residents with dementia for end of life care. Nursing Older People, 29(2), 26–30. https://doi.org/10.7748/nop.2017.e862.

- Murphy, J., Tester, S., Hubbard, G., Downs, M., & MacDonald, C. (2005). Enabling frail older people with a communication difficulty to express their views: The use of Talking Mats™ as an interview tool. Health and Social Care in the Community, 13(2), 95–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00528.x.

- Nolan, M., Keady, J., & Aveyard, B. (2001). Relationship-centred care is the next logical step. British Journal of Nursing, 10(12), 757–757. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2001.10.12.12336.

- Nygård, L. (2006). How can we get access to the experiences of people with dementia? Suggestions and reflections. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 13(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038120600723190.

- Olsen, C. F., Wiken Telenius, E., Engedal, K., & Bergland, A. (2015). Increased self-efficacy: The experience of high-intensity exercise of nursing home residents with dementia–A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 15(1), 379. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-1041-7.

- Orrell, M., Hancock, G. A., Liyanage, K. C., Woods, B., Challis, D., & Hoe, J. (2008). The needs of people with dementia in care homes: The perspectives of users, staff, and family caregivers. International Psychogeriatrics, 20(5), 941–951. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610208007266.

- Pace, R., Pluye, P., Bartlett, G., Macaulay, A. C., Salsberg, J., Jagosh, J., & Seller, R. (2012). Testing the reliability and efficiency of the pilot Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) for systematic mixed studies reviews. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49(1), 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.07.002.

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. https://doi:10.1097/xeb.0000000000000050.

- Pluye, P., & Hong, Q. N. (2014). Combining the power of stories and the power of numbers: Mixed methods research and mixed studies reviews. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182440.

- Pollock, A., & McMair, D. (2012). Going outside is essential for health and wellbeing. In A. Pollock & A. Marshall (Eds.), Designing outdoor spaces for people with dementia (pp. 23–48). Greenwich, NSW: HammondPress and DSDC.

- Popham, C., & Orrell, M. (2012). What matters for people with dementia in care homes? Aging & Mental Health, 16(2), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2011.628972.

- Powers, B. A., & Watson, N. M. (2011). Spiritual nurturance and support for nursing home residents with dementia. Dementia, 10(1), 59–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301210392980.

- Prince, M., Knapp, M., Guerchet, M., McCrone, P., Prina, M., Comas-Herrera, A., … Salimkumar, D. (2014). Dementia UK: Update (2nd ed.). London: Alzheimer’s Society.

- Robinson, L., Dickinson, C., Rousseau, N., Beyer, F., Clark, A., Hughes, J., … Exley, C. (2012). A systematic review of the effectiveness of advance care planning interventions for people with cognitive impairment and dementia. Age and Ageing, 41(2), 263–369. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afr148.

- Sabat, S. R. (2003). Some potential benefits of creating research partnerships with people with Alzheimer’s disease. Research Policy and Planning, 21(2), 5–12. http://ssrg.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/article1.pdf.

- Schweitzer, P., & Bruce, E. (2008). Remembering yesterday, caring today-reminscence in dementia care: A guide to good practice. London: Jessica Kingsley.

- Serrani Azcurra, D. J. (2012). A reminiscence program intervention to improve the quality of life of long-term care residents with Alzheimer’s disease. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria, 34(4), 422–433. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.rbp.2012.05.008.

- Tak, S. H., Kedia, S., Tongumpun, T. M., & Hong, S. H. (2015). Activity engagement: Perspectives from nursing home residents with dementia. Educational Gerontology, 41(3), 182–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601277.2014.937217.

- Tan, H. M., O’Connor, M. M., Howard, T., Workman, B., & O’Connor, D. W. (2013). Responding to the death of a resident in aged care facilities: Perspectives of staff and residents. Geriatric Nursing, 34(1), 41–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2012.08.001.

- Thein, N. W., D’Souza, G., & Sheehan, B. (2011). Expectations and experience of moving to a care home: Perceptions of older people with dementia. Dementia, 10(1), 7–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301210392971.

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

- Travers, C., Perkins, J., Rand, J., Bartlett, H., & Morton, J. (2013). An evaluation of dog-assisted therapy for residents of aged care facilities with dementia. Anthrozoos, 26(2), 213–225. https://doi.org/10.2752/175303713X13636846944169.

- Van der Roest, H. G., Meiland, F. J., Maroccini, R., Comijs, H. C., Jonker, C., & Dröes, R. M. (2007). Subjective needs of people with dementia: A review of the literature. International Psychogeriatrics, 19(3), 559–592. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610206004716.

- Van Leeuwen, K. M., Van Loon, M. S., Van Nes, F. A., Bosmans, J. E., de Vet, H. C. W., Ket, J. C. F., … Osetlo, R. W. J. (2019). What does quality of life mean to older people? A thematic synthesis. Plos One, 14(3), e0213263. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213263.

- Van Zadelhoff, E., Verbeek, H., Widdershoven, G., Van Rossum, E., & Abma, T. (2011). Good care in group home living for people with dementia. Experiences of residents, family and nursing staff. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(17-18), 2490–2500. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03759.x.

- Von Kutzleben, M., Schmid, W., Halek, M., Holle, B., & Bartholomeyczik, S. (2012). Community-dwelling persons with dementia: What do they need? What do they demand? What do they do? A systematic review on the subjective experiences of persons with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 16(3), 378–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2011.614594.

- Ward, R., Vass, A. A., Aggarwal, N., Garfield, C., & Cybyk, B. (2005). A kiss is still a kiss? The construction of sexuality in dementia care. Dementia, 4(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301205049190.

- Wiersma, E. C., & Pedlar, A. (2008). The nature of relationships in alternative dementia care environments. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement, 27(1), 101–108. https://doi.org/10.3138/cja.27.1.101.