Abstract

Objectives

Caring for a person with dementia can be challenging over the years. To support family carers throughout their entire caregiving career, interventions with a sustained effectivity are needed. A novel 6-week mobile health (mHealth) intervention using the experience sampling method (ESM) showed positive effects on carers’ well-being over a period of 2 months after the intervention. In this study, the effects after 6 months of the selfsame intervention were examined to evaluate the sustainability of positive intervention effects.

Method

The 6-week mHealth intervention consisted of an experimental group (ESM self-monitoring and personalized feedback), a pseudo-experimental group (ESM self-monitoring without feedback), and a control group (providing regular care without ESM self-monitoring or feedback). Carers’ sense of competence, mastery, and psychological complaints (depression, anxiety and perceived stress) were evaluated pre- and post-intervention as well as at two follow-up time points. The present study focuses on the 6-month follow-up data (n = 50).

Results

Positive intervention effects on sense of competence, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms were not sustained over 6-month follow-up.

Conclusion

The benefits of this mHealth intervention for carers of people living with dementia were not sustained over a long time. Similarly, other psychosocial interventions for carers of people with dementia rarely reported long-lasting effects. In order to sustainably contribute to carers’ well-being, researchers and clinicians should continuously ensure flexible adjustment of the intervention and consider additional features such as ad-hoc counseling options and booster sessions. In this regard, mHealth interventions can offer ideally suited and unique opportunities.

Introduction

The reduction of independent functioning of a person with dementia (PwD) results in the need for assistance. This demand is often carried out by a family carer (Brodaty and Donkin, Citation2009). Caring for a loved one living with dementia is a potentially rewarding (Cohen, Colantonio, & Vernich, Citation2002) but long-term task that can be time-consuming and challenging due to experienced stress, negative affect, or social isolation (Adelman, Tmanova, Delgado, Dion, & Lachs, Citation2014; Clyburn, Stones, Hadjistavropoulos, & Tuokko, Citation2000; Pinquart and Sörensen, Citation2003). Therefore, interventions with sustained positive effects are needed to support carers of PwD throughout their entire caregiving career.

The overall impact of psychosocial interventions for carers of PwD seems promising (Gilhooly et al., Citation2016), even though the effectiveness varies strongly between approaches such as educational interventions, dementia specific therapies, group or individual carer coping strategies, or behavioral management techniques (Adelman et al., Citation2014; Selwood, Johnston, Katona, Lyketsos, & Livingston, Citation2007).

To assist carers of PwD outside the clinical setting in everyday life, the intervention ‘Partner in Sight’ was developed based on the experience sampling method (ESM) delivered by a mobile device. Carers monitored activities, mood, and context in everyday life autonomously and, supported by a coach-guided feedback, got insight into their feelings and personal strength. Two months after the mobile health (mHealth) intervention, carers’ well-being was shown to be positively influenced on outcome measures of sense of competence, perceived stress, and depressive symptoms (van Knippenberg, de Vugt, Ponds, Myin-Germeys, & Verhey, Citation2018). We expected these positive effects to sustain further as an ESM intervention for depressed outpatients with a similar design showed benefits over a period of six months post-intervention (Kramer et al., Citation2014).

The aim of the present study is to evaluate the sustainability of the above-mentioned beneficial effects of the ESM intervention for carers at a 6-month follow-up. The results will be discussed in relation to other psychosocial interventions leading to a reflection about the necessity for a sustainable approach in psychosocial interventions for carers of PwD.

Methods

Participants and design

Details of the ‘Partner in Sight’ randomized control trial have been described elsewhere (van Knippenberg et al., Citation2018). In brief, informal carers of PwD of all subtypes and stages were recruited from December 2014 to June 2016. Recruitment took place in the Netherlands through memory clinics, other care institutes, as well as the digital newsletter and website of the Dutch Alzheimer Association (Alzheimer Nederland). Inclusion criteria included being a spousal carer of a PwD, sharing a household with the care recipient, and providing written informed consent. Participants were excluded from the study if cognitive abilities to engage in ESM seemed insufficient, if carers felt overburdened or had severe health problems based on clinical judgment of a knowledgeable practitioner.

A single-blinded randomized controlled trial was conducted with three treatments arms including an experimental group (ESM self-monitoring and personalized feedback), a pseudo-experimental group (ESM self-monitoring only), and a control group (providing regular care without ESM self-monitoring or feedback). The Medical Ethics Committee of the MUMC+ (#143040) approved the study. It is registered in the Dutch Trial Register (NTR4847).

Procedure

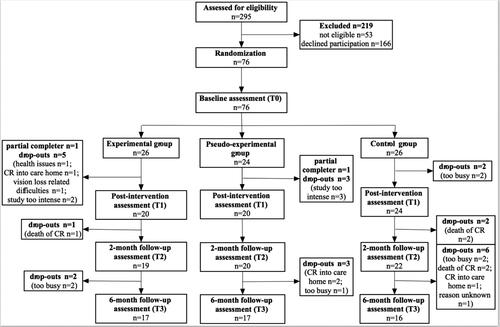

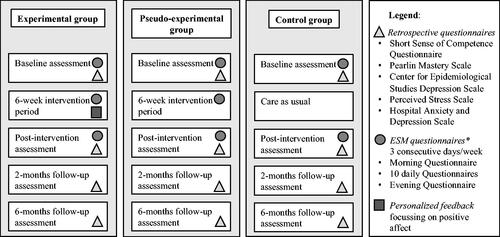

A telephone screening ensured study eligibility to participate. Furthermore, the study protocol contained a baseline assessment (T0), a 6-week intervention period, a post-intervention assessment (T1), a 2-month (T2), and a 6-month (T3) follow-up assessment. At T0, T1, T2, and T3, the questionnaires selected as primary and secondary outcome measures were filled in by the participants. illustrated the general procedure and moments of data collection.

Figure 1. ‘Partner in Sight’ intervention, general overview of the three groups and main intervention elements. Note. The full ESM questionnaire can be found in Appendix 1.

Intervention

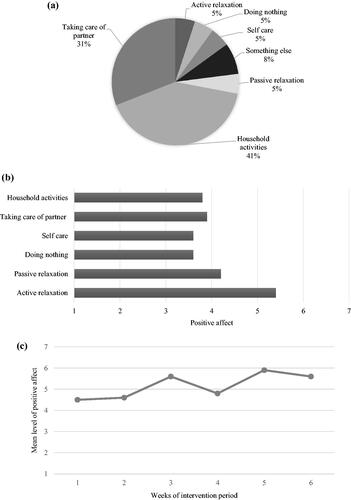

The program ‘Partner in Sight’ ran over six consecutive weeks. Both the experimental (at baseline n = 26) and the pseudo-experimental group (at baseline n = 24) self-monitored mood (e.g. positive and negative affect) and context (e.g. activities, social company and location) for three days in a row each week. The experimental group received face-to-face feedback from a coach every two weeks including a verbal and graphically visualized overview of the personal data of the previous two weeks. Each feedback session followed a standardized protocol. The focus lay on the identification and highlighting of positive affect experienced during activities and social interactions in daily life. For example, a carer might have experienced high levels of positive affect during active relaxation activities but did actually spend very little time on this activity. The coach then stimulated the carer to think about this finding and potentially redirect behaviors towards activities related to more positive emotions. In addition, changes in daily average positive affect during the intervention period were discussed and thus positively reinforced as part of the motivational coaching. illustrates an example of the ESM-based feedback. The summarized feedback was handed out to each participant and clinicians involved (health care professionals involved in the treatment for the PwD and who approached the carer to participate in the study).

Figure 2. Examples of ESM-based feedback graphs. (a) Amount of time spend doing different types of activities; (b) Amount of positive affect experienced per type of activity; (c) Mean level of positive affect over the 6-week intervention period.

The pseudo-experimental group was similar in the ESM procedure including face-to-face sessions, except that no feedback was provided during these sessions. Instead, a semi-structured interview was conducted focused on the participant’s wellbeing during the previous two weeks (i.e. SSCQ, PSS, PMS, CES-D, HADS, and NPI-Q). The ESM responses were not discussed when mentioned by the carer, but issues with the use of the PsyMate or unclear ESM items were addressed.

All face-to-face counselling sessions of both intervention groups took place at the participant’s home. In the experimental group, the feedback sessions took about 90 minutes, while the face-to-face session in the pseudo-experimental group lasted for about 60 minutes. The control group (at baseline n = 26) did not take part in the intervention but continued with regular care.

Experience sampling methodology (ESM)

ESM self-monitoring of mood and context was conducted with the ‘PsyMate’ mobile device (www.psymate.eu). The ‘PsyMate’ has been used in diverse populations (Myin-Germeys, Birchwood, & Kwapil, Citation2011; Verhagen, Hasmi, Drukker, van Os, & Delespaul, Citation2016) and is feasible for carers of PwD (van Knippenberg, de Vugt, Ponds, Myin-Germeys, van Twillert, & Verhey, Citation2017).

During the 6-week intervention period, participants used the ‘PsyMate’ as a digital diary to fill in structured questionnaires about mood and context ten times per day on three consecutive days, with a total amount of n = 180 (10 beeps × 3 consecutive days × 6 weeks). Positive affect as part of the mood questions was defined as the mean score of the items ‘I feel cheerful’, ‘I feel relaxed’, ‘I feel enthusiastic’ and ‘I feel satisfied’. The full ESM item list can be found in appendix 1. Of the 50 participants, 39 (78.0%) participants in the experimental or pseudo-experimental group fully completed the 6-week intervention period (6 × 3 ESM assessment days and three corresponding face-to-face sessions). The average number of completed beep-questionnaires in these 39 participants was 137.4 ± 20.2 out of 180, indicating a completion rate of 76.4% (van Knippenberg et al., Citation2018).

Instruments

Baseline assessment

Sociodemographic information of the carer and the PwD were assessed at baseline including age, gender and the level of education. The severity of dementia was measured by the Clinical Dementia Rating Scale (CDR) (Hughes, Berg, Danziger, Coben, & Martin, Citation1982).

Primary outcomes

Carers’ sense of competence and mastery were chosen as primary outcomes measured with retrospective questionnaires. The Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire (SSCQ) reflects the carer’s sensation of being capable to care for the person with dementia. It consists of seven items and total scores range from 7 to 35 (Vernooij-Dassen, Persoon, & Felling, Citation1996). The construct validity of this instrument was supported by a high Person correlation (0.88) between the SSCQ and the original Sense of Competence Questionnaire (Vernooij-Dassen et al., Citation1999) as well as a high reliability (Cronbach’s alpha of .89; van Knippenberg, de Vugt, Ponds, Myin-Germeys, & Verhey, Citation2017). The Pearlin Mastery Scale (PMS) evaluates feelings of mastery, consists of seven items, and a total scores range from 0 to 28 (Pearlin and Schooler, Citation1978). Previous studies reported good psychometric properties of the PMS (Eklund, Erlandsson, & Hagell, Citation2012; Gordon, Malcarne, Roesch, Roetzheim, & Wells, Citation2018; Kempen, Citation1992).

Secondary outcomes

Secondarily, depressive symptoms, perceived stress, and anxiety symptoms were measured using standardized questionnaires. Depressive symptoms were evaluated with the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) consisting of 20 items and a total score range from 0 to 60 (Radloff, Citation1977). The CES-D is widely used and has good psychometric properties as shown by previous research (Hann, Winter, & Jacobsen, Citation1999; Knight, Williams, McGee, & Olaman, Citation1997; Morin et al., Citation2011). The Perceived Stress Scale (PSS) includes 10 items, has a total score range from 0 to 40, and was used to assess perceived stress in carers (S. Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, Citation1983). A review of previous PSS studies confirmed good psychometric properties of the PSS, particularly in the 10-item version used in the present study (Lee, Citation2012). Finally, the seven-item anxiety subscale of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS-A) with a total range from 0 to 21 was chosen to rate the severity of anxiety symptoms (Zigmond and Snaith, Citation1983). The psychometric properties of the HADS-A have been found to be good in older adults (Djukanovic, Carlsson, & Årestedt, Citation2017).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 24. The data-set was checked for missing values, normality, and outliers before further analysis. Potential baseline differences between the three treatment groups were tested with t-test for continuous variables and χ2-test for categorical variables. In case of unmet assumptions, non-parametric tests were used. Baseline characteristics were added as potential confounders in the analyses in case of significant group differences.

For the main analyses, generalized estimated equation for the Gaussian family and identity-link function were specified to yield population-average unstandardized regression-coefficient (B) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). To evaluate the impact of treatment allocation on the course of carer sense of competence, mastery, depressive symptoms, perceived stress, and anxiety symptoms, treatment allocation (experimental, pseudo-experimental, control group) was entered as a between-subject factor, time (baseline, post-intervention, 2-month and 6-month follow-up) as a within-subject factor, and their two-way interaction as additional factor. To account for the correlated data (repeated measures), an unstructured working correlation matrix (R matrix) was specified. Post-hoc analyses were performed to calculate estimated between-group effects. All tests of significance reported mean change and were two-tailed with a minimal α set at 0.05.

Results

Participants and descriptive statistics

A total of 76 carers participated in the intervention and 61 participants completed the 2-month follow-up assessment. Another eleven participants dropped out leaving a total of n = 50 carers six months after the intervention (experimental group n = 17, pseudo-experimental group n = 17, control group n = 16). Reasons for the drop-out are listed in the flow-chart (). There were no significant differences in the socio-demographics between the groups at baseline ().

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

Primary outcomes

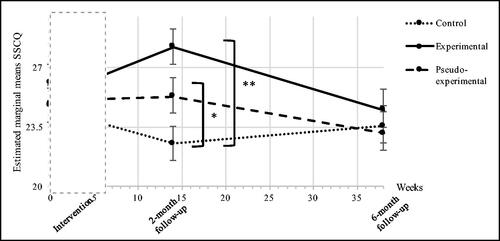

Sense of competence (SSCQ)

Multilevel regression analyses showed a significant overall interaction effect between treatment allocation and time on retrospectively measured sense of competence (F(6,50)= 3.329, p = 0.007), indicating that SSCQ scores differed between the three groups over the course of the study.

At 6-month follow-up, no significant differences were found for the SSCQ score between the control group and either the experimental (B = −0.40, 95% Cl = −3.27 to 2.47, p = 0.781) or pseudo-experimental group (B = −0.47, 95% Cl = −3.34 to 2.41, p = 0.746). Consequently, the SSCQ scores between the experimental and pseudo-experimental group did not differ significantly 6-month post-intervention (B = −0.067, 95% Cl = −2.95 to 2.81, p = 0.963) (see ).

Mastery (PMS)

For the PMS scores, analyses showed no significant overall interaction effect between treatment allocation and time on retrospectively measured mastery in carers (F(6,50)=0.744, p = 0.617), indicating that no significant group differences were present over the course of the study.

Secondary outcomes

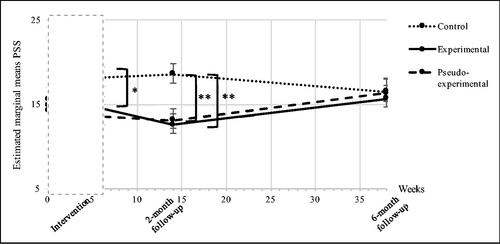

Perceived stress (PSS)

The overall interaction effect between treatment allocation and time on retrospectively measured PSS scores was significant (F(6,50)=2.96, p = 0.013), indicating different perception of stress between the three groups over the course of the study.

At 6-month follow-up, no significant difference between the groups was observed (control vs. experimental group (B = 0.476, 95% Cl = −4.24 to 5.19, p = 0.841); control vs. pseudo-experimental group (B = 0.522, 95% Cl = −4.22 to 5.26, p = 0.826); experimental vs. pseudo-experimental group (B = 0.046, 95% Cl = −4.69 to 4.79, p = 0.984) (see ).

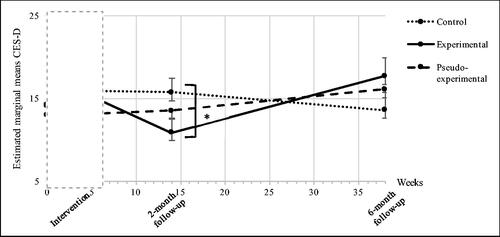

Depressive symptoms (CES-D)

Analyses showed a significant overall interaction effect between treatment allocation and time on the retrospectively measure of depressive symptoms (F(6,50) = 2.553, p = 0.028), indicating that CES-D scores differed between the three groups over the course of the study.

At 6-month follow-up, no significant results were found between groups with regards to depressive symptoms measured with the CES-D (control vs. experimental group (B = 5.05, 95% Cl = −0.106 to 10.21, p = 0.055); control vs. pseudo-experimental group (B = 2.64, 95% Cl = −2.52 to 7.81, p = 0.309); experimental vs. pseudo-experimental group (B = −2.41, 95% Cl = −7.53 to 2.72, p = 0.35) (see ).

Symptoms of anxiety (HADS-A)

The overall interaction effect between treatment allocation and time on retrospectively measured symptoms of anxiety measured with the HADS-A was non-significant (F(6,50) = 1.65, p = 0.15), indicating that no significant group differences were present over the course of the study.

Details of the results of all outcome measures directly and 2-month post-intervention can be reviewed at van Knippenberg et al. (Citation2018).

Discussion

This study examined the sustainability of effects after six months of a promising 6-week-long ESM intervention for informal carers of PwD. The outcome measures evaluated carers’ well-being namely sense of competence, feelings of mastery, and psychological complaints (depressive symptoms, anxiety and perceived stress). While the results obtained after two months showed that the intervention ‘Partner in Sight’ can reduce feelings of stress and depressive symptoms as well as enhance sense of competence in carers (van Knippenberg et al., Citation2018), no positive effects could be reported after six months. As the study design was orientated on the design of an ESM intervention for depressed outpatient with sustained intervention effects over six months (Kramer et al., Citation2014), the disappearance of beneficial effect in the present study was unexpected. The ‘Partner in Sight’ intervention was theoretically based on the idea that self-monitoring, particularly in combination with a personalized feedback, would promote an emotional and behavioral change towards more enjoyable activities (Kanning, Ebner-Priemer, & Schlicht, Citation2013). Carers would thus become more aware of and engage more in behaviors that elicit positive emotions, such as relaxation and social activities. The coping process model suggesting furthermore that positive emotions are important to cope with challenging life events (Folkman, Citation1997; Folkman & Moskowitz, Citation2000), such as caring for a person with dementia. Additionally, the broaden-and-build theory believes that positive emotions build a person’s resources (Fredrickson, Citation1998, Citation2004), potentially influencing feelings of mastery, sense of competence, and emotional well-being (Fredrickson, Citation2001, Citation2013). As the 2-month follow-up results showed (van Knippenberg et al., Citation2018), this theoretical basis was widely constructive. However, in carers of PwD the intervention design might have been lacking additional features to sustain beneficial effects on well-being.

Noticeable is the fact that this ESM intervention is not the only psychosocial intervention in dementia care not finding sustainable intervention effects after a few months, as a similar disappearance of positive effects over time has been observed in other studies. For example, providing a comprehensive home care program for people with early stages of Alzheimer’s disease and their carers reduced feelings of burden in carers six months after the intervention started but not at 10, 14 or 18 months (Chu, Edwards, Levin, & Thomson, Citation2000). Similarly, carers’ coping strategies improved after three months participating together with the care recipient in the Meeting Centers Support Program. The post-measure at seven months revealed the disappearance of this positive intervention effect (Dröes, Breebaart, Meiland, van Tilburg, & Mellenbergh, Citation2004). A short telephone-based cognitive behavioral intervention for carers leading to positive long-term effects on one scale for emotional well-being with small effect size (Wilz, Meichsner, & Soellner, Citation2017). In the same study, no significant group differences were found for depressive symptoms, health status, bodily complaints, and quality of life after two years (Wilz et al., Citation2017). These studies are but some examples and due to the difficulty to publish negative results (Matosin, Frank, Engel, Lum, & Newell, Citation2014), it is possible that a variety of psychosocial interventions experienced the disappearance of positive intervention effects but did not publish these findings.

In general, the goal of systematic reviews focusing on psychosocial intervention in dementia care seems to be the evaluation of their composition and effectiveness rather than the sustainability of these effects (Gilhooly et al., Citation2016; Hopwood et al., Citation2018). Pinquart and Sörensen (Citation2006) observed that the effect-sizes of carer interventions are usually small and fewer significant effects appear at follow-up. Reviews further reveal that most studies (60–90%) did not follow up participants at all or report effects only during a relatively short period of less than 6-month post-intervention (Abrahams et al., Citation2018; Chien et al., Citation2011; Cooke, McNally, Mulligan, Harrison, & Newman, Citation2001; Dam, de Vugt, Klinkenberg, Verhey, & van Boxtel, Citation2016; Selwood et al., Citation2007). Where interventions include additional follow-ups, there is a considerable variation in the length of follow-up amongst trials (Jensen, Nwando Agbata, Canavan, & McCarthy, Citation2015; Thompson et al., Citation2007), leading to difficulties in comparison between studies. Finally, the number of studies using identical instruments and follow-up measurement points in similar target groups is limited (Pendergrass, Becker, Hautzinger, & Pfeiffer, Citation2015; Smith et al., Citation2007). An example of another intervention for carers of people with dementia that effectively increased well-being over the intervention period but treatment effects were not maintained after six months is the internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral intervention called Tele.TAnDem (Meichsner, Theurer, & Wilz, Citation2019).

In the present study, the recession of positive intervention effects could be ascribed to the following aspects. To start with, the intensity of the intervention may have been too low. A high intervention intensity is generally associated with greater long-term effects (Huis in het Veld, Verkaik, Mistiaen, van Meijel, & Francke, Citation2015). The design of the present intervention was based on the setup originally aimed at depressed outpatients with a similar 6-week intervention period. However, it provided twice the amount of feedback sessions (Kramer et al., Citation2014). The results showed a sustainable reduction of depressive symptoms 6-month post-intervention. The decision to reduce the feedback sessions in our study was made in order to avoid potential overburdening of carers as both the caring-tasks and the ESM intervention require time. Future research could pay extra attention to adjusting the balance between both.

Furthermore, the theoretical framework of the intervention was originally built for depressed outpatients, for whom positive affect is an important drive (Höhn et al., Citation2013). Raising awareness for positive affect in people with depression can lead to actual behavioral changes and thereby long-lasting effects (Snippe et al., Citation2016). In carers, this framework might need adjustment as caring for a person with dementia is a complex task not only accompanied by depressive symptoms but other stressors. This interesting research question focusing on carers’ behavioral change in everyday life will be addressed shortly. Outcomes of interventions are influenced by a variety of features such as the context, individual participant responses to, and interactions with the intervention, other mediators and unexpected pathways and consequences (Moore et al., Citation2015) and therefore, insight into causations are essential.

Generally, the ‘Partner in Sight’ intervention might be beneficial to improve carers’ well-being over a certain period of time but adjustments to meet the altered needs of carers over time (Peeters, van Beek, Meerveld, Spreeuwenberg, & Francke, Citation2010) could contribute to sustain effects. Furthermore, after the ‘Partner in Sight’ intervention, carers in the experimental group showed a non-significant increase of depressive symptoms between the 2-month and 6-month follow-up (see ). This trend may again highlight the need for an intervention design to provide support long-term as not having access to an intervention that initially provided relief might later aggravate the well-being of the carer. The trend could also be explained by a deterioration of the care recipients condition, or a combination of both. Dementia as a progressive neurodegenerative disease leads to continuous changes and a range of new challenges for the carer. Therefore, a stabilization of carers’ well-being rather than decline can already be seen as a positive outcome.

There are general limitations to this study. First of all, the study is likely to be underpowered to detect smaller intervention effects in the long-term as the recruitment itself was a challenge resulting in a small sample size at baseline. Over the course of the study, the rate of drop-outs due to care recipients moving into care homes, death of care recipients, or a high load of carers’ obligations led additionally to a selective attrition and reduced participation at 6-month follow-up. Additionally, the composition of the study population might have influenced the outcome resulting in questionable generalization. As mentioned above, ESM interventions are time-consuming, potentially resulting in an initial selection bias towards a group of carers not yet exposed to the high demand of care. Furthermore, the feedback sessions were originally planned to have a duration of 45 minutes, but lasted in the experimental group (∼90 min.) significantly longer than in the pseudo-experimental group (∼60 min.). This difference in personal contact with the coach could have influenced the results. Finally, other factors such as the financial status or holistic living situation (i.e. not only living with the person with dementia but also other family members) were not taken into account and might have potentially influenced the intervention effects.

Recommendations to achieve sustainability of intervention effects

Carers of PwD expressed the need for support provided over a longer period (Bormann et al., Citation2009). Clinicians and researchers should be aware of this need and aim to meet it. Thus, interventions for carers should include additional features after the main period of the intervention.

Examples to report on sustainable intervention effects in dementia care are the studies by Livingston et al. (Citation2014) and Mittelman, Roth, Coon, & Haley (Citation2004). Livingston et al. (Citation2014) conducted eight sessions of a manual-based coping intervention improving carers’ depression and anxiety sustainably over two years. However, their study is the only one finding long-term results without any additional features after the intervention period and underlying mechanisms are not evaluated. In contrast, Mittelman et al. (Citation2004) added additional features after the main period of the intervention. Initially, carers were randomly assigned to either a group receiving enhanced counseling and support treatment, or a control group, receiving usual care. The treatment group participated in six sessions of individual and family counseling. After the main intervention, the attendance of support groups four months after enrollment and ongoing ad-hoc counseling resulted in a decrease of depressive symptoms in the treatment group compared to the control group over a period of 3.1 years post-enrollment. Consequently, a short intervention, counseling, and readily available supportive maintenance can have long-lasting effects in reducing symptoms of depression among carers of PwD (Mittelman et al., Citation2004).

Availability of experts/counselors

In the ‘Partner in Sight’ intervention, counselling took place during the feedback sessions. Prospectively, if the intervention would be delivered via the PsyMate application rather than the mobile device, ongoing contact with an expert could be promoted. A messaging function is not yet integrated in this particular application but other smartphone applications offer chat options and mHealth interventions would be generally able to maintain contact after the intervention. The availability of a counselor at any time after the intervention eventually gives carers a feeling of security when facing problems and the chance to adapt to new challenges with encouragement.

Flexible tailoring to change in needs

Most interventions follow a personalized approach. Researchers and clinicians should be aware, however, that a person-tailored intervention might need to be adapted along the course as the context and the needs of the carer might change (Peeters et al., Citation2010). The framework by Chiu and Eysenbach (Citation2010) highlighted the importance for eHealth interventions to be dynamic, continuous, and longitudinal with respect to the different stages of the dementia. Regular evaluation of the expectations and suggestions from the carers could help to optimize the support. In the ‘Partner in Sight’ intervention, the ESM itself was incorporated in everyday life. Furthermore, the individualized feedback for each carer ensured flexibility and tailoring. This procedure should not be limited to the intervention period only. Potentially, the PsyMate application could be used by the carer autonomously with an online feedback and the option to contact the clinician if needed. Thus, self-monitoring and self-management could be promoted and might give the carer insight into changes in own emotions and behavior.

Booster sessions

Interventions in dementia care might need regular booster sessions post-intervention to guarantee a long-term effect as incorporated in a drug abuse prevention program (Botvin, Baker, Dusenbury, & Botvin, Citation1995). Through such a booster session, the participant might be reminded of learned strategies or knowledge achieved during the intervention. In carers especially, it might raise awareness for own strengths and offers opportunities to adapt these strengths to other contexts in everyday life. Booster sessions in an ESM intervention could mean a micro-intervention of a few days a couple of months after the main intervention including a personalized face-to-face or digitalized feedback.

Implications

In the last years, e- and mHealth strategies have been increasingly used in clinical populations not limited to dementia care to improve individuals’ well-being and health, to promote the communication between professionals and health care recipients, and reduce costs of health care (Kumar et al., Citation2013; Zapata, Fernández-Alemán, Idri, & Toval, Citation2015). The evaluation of the effectiveness and efficacy of mHealth interventions seems promising (Myin-Germeys, Klippel, Steinhart, & Reininghaus, Citation2016; Tomlinson, Rotheram-Borus, Swartz, & Tsai, Citation2013), even though, the sustainability of mHealth intervention effects needs more attention. The underlying mechanisms to achieve these sustainable intervention effects for carers of PwD, however, are currently unknown. Qualitative research could evaluate carers’ ideas on this topic via interviews or focus groups.

E- and mHealth interventions delivered by a mobile device or application offer the unique opportunity to provide a flexible, personal-tailored approach with a 24/7 access to experts. The present study can be seen as the first step towards a sustainable support for carers. Future research might focus on features such as notifications in apps, regular emails, or reminders in mobile devices to promote booster effects. Additionally, research on programming technology tailored to personal needs, including education and coping-strategies would be beneficial. Most importantly, the option to share questions and problems with the social network including family, friends, and clinical experts at any time should be investigated.

With increasing awareness for the necessity for support throughout the carers’ entire career, we hope to be able to assist carers optimally in caring for their loved ones living with dementia.

Conclusion

The ‘Partner in Sight’ experience sampling intervention had beneficial effects on carer’s well-being over a period of 2 months, however, not 6 months. Reflecting on this result as well as outcomes of other interventions, it is suggested to prospectively include additional features such as ad-hoc counseling options and booster sessions as well as ensure flexible adjustment to meet the changing needs of carers. The caregiving career continues often over years and therefore, clinicians and researchers need to be aware of the necessity for sustainable intervention effects.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the participants taking part in this research. Furthermore, the authors wish to acknowledge Claudia Smeets for her help during study recruitment and data management.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abrahams, R., Liu, K. P. Y., Bissett, M., Fahey, P., Cheung, K. S. L., Bye, R., … Chu, L.-W. (2018). Effectiveness of interventions for co-residing family caregivers of people with dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 65(3), 208–224.

- Adelman, R. D., Tmanova, L. L., Delgado, D., Dion, S., & Lachs, M. (2014). Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA, 311(10), 1052–1059.

- Bormann, J., Warren, K., Regalbuto, L., Glaser, D., Kelly, A., Schnack, J., & Hinton, L. (2009). A spiritually based caregiver intervention with telephone delivery for family caregiver of veterans with dementia. Alzheimer’s Care Today, 10(4), 212–220.

- Botvin, G. J., Baker, E., Dusenbury, L., & Botvin, E. M. (1995). Long-term follow-up results of a randomized drug abuse prevention trial in a white middle-class population. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association, 273(14), 1106–1112.

- Brodaty, H., & Donkin, M. (2009). Family caregivers of people with dementia. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 11(2), 217–228.

- Chien, L.-Y., Chu, H., Guo, J.-L., Liao, Y.-M., Chang, L.-I., Chen, C.-H., & Chou, K.-R. (2011). Caregiver support groups in patients with dementia: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(10), 1089–1098.

- Chiu, T. M. L., & Eysenbach, G. (2010). Stage of use: Consideration, initiation, utilization and outcomes on an internet-mediated intervention. BMC Informatics and Decision Making, 10, 73.

- Chu, P., Edwards, J., Levin, R., & Thomson, J. (2000). The use of clinical case management for early stage Alzheimer’s patients and their families. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Disease, 15(5), 284–290.

- Clyburn, L. D., Stones, M. J., Hadjistavropoulos, T., & Tuokko, H. (2000). Predicting caregiver burden and depression in Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Gerontology, 55(1), 2–13.

- Cohen, C. A., Colantonio, A., & Vernich, L. (2002). Positive aspects of caregiving: Rounding out the caregiver experience. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(2), 184–188.

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24(4), 385–396.

- Cooke, D. D., McNally, L., Mulligan, K. T., Harrison, M. J. G., & Newman, S. P. (2001). Psychosocial interventions for caregivers of people with dementia: A systematic review. Aging & Mental Health, 5(2), 120–135.

- Dam, A. E., de Vugt, M. E., Klinkenberg, I. P., Verhey, F. R., & van Boxtel, M. P. (2016). A systematic review of social support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia: Are they doing what they promise? Maturitas, 85, 117–130.

- Djukanovic, I., Carlsson, J., & Årestedt, K. (2017). Is the hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) a valid measure in a general population 65–80 years old? A psychometric evaluation study. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 15(1), 193.

- Dröes, R.-M., Breebaart, E., Meiland, F. J. M., van Tilburg, W., & Mellenbergh, G. J. (2004). Effect of Meeting Centres Support Program on feelings of competence of family carers and delay of institutionalization of people with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 8(3), 201–211.

- Eklund, M., Erlandsson, L.-K., & Hagell, P. (2012). Psychometric properties of a Swedish version of the Pearlin Mastery Scale in people with mental illness and healthy people. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 66(6), 380–388.

- Folkman, S. (1997). Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science &Amp; Medicine (1982), 45(8), 1207–1221.

- Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2000). Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist, 55(6), 647–654.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology: Journal of Division 1, of the American Psychological Association, 2(3), 300–319.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 359(1449), 1367.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Positive emotions broaden and build. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 47, pp. 1–53). Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

- Gilhooly, K. J., Gilhooly, M. L. M., Sullivan, M. P., McIntyre, A., Wilson, L., Harding, E., … Crutch, S. (2016). A meta-review of stress, coping and interventions in dementia and dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatrics, 16(106), 106.

- Gordon, J. R., Malcarne, V. L., Roesch, S. C., Roetzheim, R. G., & Wells, K. J. (2018). Structural validity and measurement invariance of the Pearlin Mastery Scale in Spanish-speaking primary care patients. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 41(3), 393–399.

- Hann, D., Winter, K., & Jacobsen, P. (1999). Measurement of depressive symptoms in cancer patients: Evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 46(5), 437–443.

- Höhn, P., Menne-Lothmann, C., Peeters, F., Nicolson, N. A., Jacobs, N., Derom, C., … Wichers, M. (2013). Moment-to-moment transfer of positive emotions in daily life predicts future course of depression in both general population and patient samples. PLoS One, 8(9), e75655.

- Hopwood, J., Walker, N., McDonagh, L., Rait, G., Walters, K., Iliffe, S., … Davies, N. (2018). Internet-based interventions aimed at supporting family caregivers of people with dementia: Systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(6), e216. p

- Hughes, C. P., Berg, L., Danziger, W. L., Coben, L. A., & Martin, R. L. (1982). A new clinical scale for the staging of dementia. British Journal of Psychiatry, 140(6), 566–572.

- Huis In Het Veld, J. G., Verkaik, R., Mistiaen, P., van Meijel, B., & Francke, A. L. (2015). The effectiveness of interventions in supporting self-management of informal caregivers of people with dementia; a systematic meta review. BMC Geriatrics, 15(1), 147.

- Jensen, M., Nwando Agbata, I., Canavan, M., & McCarthy, G. (2015). Effectiveness of educational interventions for informal caregivers of individuals with dementia residing in the community: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(2), 130–143.

- Kanning, M. K., Ebner-Priemer, U. W., & Schlicht, W. M. (2013). How to investigate within-subject associations between physical activity and momentary affective states in everyday life: A position statement based on a literature overview. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 187.

- Kempen, G. (1992). Psychometric properties of GLAS baseline measures: A pilot study. Northern Centre for Healthcare Research, University of Groningen, The Netherlands.

- Knight, R. G., Williams, S., McGee, R., & Olaman, S. (1997). Psychometric properties of the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in a sample of women in middle life. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35(4), 373–380.

- Kramer, I., Simons, C. J. P., Hartmann, J. A., Menne-Lothmann, C., Viechtbauer, W., Peeters, F., … Wichers, M. (2014). A therapeutic application of the experience sampling method in the treatment of depression: A randomized controlled trial. World Psychiatry, 13(1), 68–77.

- Kumar, S., Nilsen, W. J., Abernethy, A., Atienza, A., Patrick, K., Pavel, M., … Swendeman, D. (2013). Mobile health technology evaluation the mHealth evidence workshop. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 45(2), 228–236.

- Lee, E.-H. (2012). Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nursing Research, 6(4), 121–127.

- Livingston, G., Barber, J., Rapaport, P., Knapp, M., Griffin, M., King, D., … Cooper, C. (2014). Long-term clinical and cost-effectiveness of psychological intervention for family carers of people with dementia: A single-blind, randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(7), 539–548.

- Matosin, N., Frank, E., Engel, M., Lum, J. S., & Newell, K. A. (2014). Negativity towards negative results: A discussion of the disconnect between scientific worth and scientific culture. The Company of Biologists Ltd. Disease Models & Mechanisms, 7, 171–173.

- Meichsner, F., Theurer, C., & Wilz, G. (2019). Acceptance and treatment effects of an internet-delivered cognitive-behavioral intervention for family caregivers of people with dementia: A randomized-controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 75(4), 594–613.

- Mittelman, M., Roth, D. L., Coon, D. W., & Haley, W. E. (2004). Sustained benefit of supportive intervention for depressive symptoms in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Psychiatry, 161(5), 850–856.

- Moore, G. F., Audrey, S., Barker, M., Bond, L., Bonell, C., Hardeman, W., … Baird, J. (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 350(6), h1258.

- Morin, A., Moullec, G., Maiano, C., Layet, L., Just, J.-L., & Ninot, G. (2011). Psychometric properties of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) in French clinical and nonclinical adults. Revue D'épidémiologie et de Santé Publique, 59(5), 327–340.

- Myin-Germeys, I., Birchwood, M., & Kwapil, T. (2011). From environment to therapy in psychosis: A real-world momentary assessment approach. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 37(2), 244–247.

- Myin-Germeys, I., Klippel, A., Steinhart, H., & Reininghaus, U. (2016). Ecological momentary interventions in psychiatry. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 29(4), 258–263.

- Pearlin, L. I., & Schooler, C. (1978). The structure of coping. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 19(1), 2–21.

- Peeters, J. M., van Beek, A., Meerveld, J., Spreeuwenberg, P., & Francke, A. (2010). Informal caregivers of persons with dementia, their use of and needs for specific professional support: A survey of the National Dementia Programme. BMC Nursing, 9(1), 9.

- Pendergrass, A., Becker, C., Hautzinger, M., & Pfeiffer, K. (2015). Dementia caregiver interventions: A systematic review of caregiver outcomes and instruments in randomized controlled trials. International Journal of Emergency Mental Health and Human Resilience, 17(2), 459–468.

- Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2003). Differences between caregivers and noncaregivers in psychological health and physical health: A meta-analysis. Psychology and Aging, 18(2), 250. p

- Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2006). Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: Which interventions work and how large are their effects? International Psychogeriatrics, 18(4), 577–595.

- Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3), 385–401.

- Selwood, A., Johnston, K., Katona, C., Lyketsos, C., & Livingston, G. (2007). Systematic review of the effect of psychological interventions on family caregivers of people with dementia. Journal of Affective Disorders, 101(1–3), 75–89.

- Smith, C. H. M., de Lange, J., Dröes, R. M., Meiland, F. J. M., Vernooij-Dassen, M., & Pot, A. M. (2007). Effects of combined intervention programmes for people with dementia living at home and their caregivers: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 22, 1181–1193.

- Snippe, E., Simons, C. J. P., Hartmann, J. A., Menne-Lothmann, C., Kramer, I., Booij, S. H., … Wichers, M. (2016). Change in daily life behavior and depression: Within-person and between-person associations. Health Psychology, 35(5), 433–441.

- Thompson, C. A., Spilsbury, K., Hall, J., Birks, Y., Barnes, C., & Adamson, J. (2007). Systematic review of information and support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. BMC Geriatrics, 7(1), 18.

- Tomlinson, M., Rotheram-Borus, M. J., Swartz, L., & Tsai, A. C. (2013). Scaling up mHealth: Where is the evidence. PLoS Medicine, 10(2), e1001382.

- van Knippenberg, R. J., de Vugt, M. E., Ponds, R. W., Myin-Germeys, I., & Verhey, F. R. (2017). Dealing with daily challenges in dementia (deal-id study): An experience sampling study to assess caregivers’ sense of competence and experienced positive affect in daily life. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(8), 852–859.

- van Knippenberg, R. J. M., de Vugt, M., Ponds, R. W., Myin-Germeys, I., van Twillert, B., & Verhey, F. R. J. (2017). Dealing with daily challenges in dementia (deal-id study): An experience sampling study to assess caregiver functioning in the flow of daily life. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(9), 949–958.

- van Knippenberg, R. J. M., de Vugt, M. E., Ponds, R. W., Myin-Germeys, I., & Verhey, F. R. J. (2018). An experience sampling method intervention for dementia caregivers: Results of a randomized controlled trial. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(12), 1231.

- Verhagen, S. J. W., Hasmi, L., Drukker, M., van Os, J., & Delespaul, P. E. G. (2016). Use of the experience sampling method in the context of clinical trials. Evidence Based Mental Health, 19(3), 86–89.

- Vernooij-Dassen, M. J. F. J., Persoon, J. M. G., & Felling, A. J. A. (1996). Predictors of sense of competence in caregivers of demented persons. Social Science & Medicine, 43, 41–49.

- Vernooij-Dassen, M. J., Felling, A. J., Brummelkamp, E., Dauzenberg, M. G., van den Bos, G. A., & Grol, R. (1999). Assessment of caregiver’s competence in dealing with the burden of caregiving for a dementia patient: A Short Sense of Competence Questionnaire (SSCQ) suitable for clinical practice. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 47(2), 256–257.

- Wilz, G., Meichsner, F., & Soellner, R. (2017). Are psychotherapeutic effects on family caregivers of people with dementia sustainable? Two-year long-term effects of a telephone-based cognitive behavioral intervention. Aging & Mental Health, 21(7), 774–781.

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–396.

- Zapata, B. C., Fernández-Alemán, J. L., Idri, A., & Toval, A. (2015). Empirical studies on usability of mHealth apps: A systematic literature review. Journal of Medical Systems, 39(2), 1–19.

Appendix 1. Description of the ESM concepts, items and response choices in the daily, morning and evening questionnaire