Abstract

Objectives

The aim of the present study was to investigate the association between trait gratitude and loneliness in a Dutch population sample of adults over 40 years. In addition, the mediating role of psychological flexibility and engaged living between trait gratitude and loneliness was assessed.

Method

A total sample of 163 adults of which 65 men (40%) and 98 women (60%) between 41 and 92 years (Mage = 66, SDage = 12) participated in this study. Data from the Loneliness Questionnaire, Flexibility Index Test, Engaged Living Scale and the Short Gratitude, Resentment, and Appreciation Test were used. Mediation analysis was performed.

Results

Analysis showed a negative association between trait gratitude and loneliness. In addition, after adjusting for the demographic variables age, gender and educational level, the association between trait gratitude and loneliness was fully mediated by psychological flexibility, and partially mediated by engaged living.

Conclusion

This study endorses the importance of trait gratitude and psychological flexibility in relation to experiencing loneliness. Further research is needed to replicate these findings in a more diverse sample and to investigate the causal relationships between these constructs. It would also be interesting to further investigate the role of different age groups and goal (dis)engagement strategies in this relation.

Introduction

When people age, they are confronted with many challenges in life such as physical and cognitive decline, experiencing pain, being affected by disruptive stressors, or loss of family or friends leading to social isolation and loneliness (Hill, Citation2011). On the other hand, undergoing adversity increases the likelihood of engagement in a quest for meaning in life and adaptation to changed circumstances (P. T. P. Wong, Citation2016). Therefore, it is recommended to consider aging as a challenge or opportunity to make changes in life instead of a burden (Pavlickova & Nagyova, Citation2016).

Regarding loneliness, within the European Union, the Netherlands is in third place of countries with the highest rates of loneliness (Eurostat, Citation2017). The prevalence of loneliness increases with age, from 41% of the middle-aged population to 63% of the older adults at the age of 85 or older (Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu, Citation2016). Scientists argue that loneliness comprises two characteristics. First, loneliness is considered as an aversive experience with negative affective states such as anxiety or sadness. Second, loneliness is seen as a subjective perception of quantitative shortcomings in social networks. These shortcomings can be due to the absence of relationships within a social network – social loneliness – or qualitative shortcomings due to the absence of intimate relationships with others – emotional loneliness (Brimelow & Wollin, Citation2017; De Jong Gierveld, Keating, & Fast, Citation2015; Menec, Newall, Mackenzie, Shooshtari, & Nowicki, Citation2019; Russell, Cutrona, Rose, & Yurko, Citation1984). Risk factors for loneliness include the loss of social contacts, activities or work, serious health problems, genetic predispositions and personality factors. There is a vast amount of evidence that loneliness has detrimental effects on human physical and mental health such as cardiovascular diseases, stress perception, depression and suicide ideation (Christiansen, Larsen, & Lasgaard, Citation2016; Gan, Xie, Duan, Deng, & Yu, Citation2015; Hegeman et al., Citation2018; Huang et al., Citation2019; Kharicha et al., Citation2017; Niu et al., Citation2018; Stickley & Koyanagi, Citation2016; Valtorta, Kanaan, Gilbody, & Hanratty, Citation2018; Wolf & Davis, Citation2014). Additionally, loneliness can be the result of the accumulation of multiple risk factors (Niedzwiedz et al., Citation2016). Loneliness is, for example, associated with unhealthy lifestyle behavior such as less physical activity, obesity or smoking, which affects the likelihood of developing chronic diseases and subsequently may lead to more psychological distress (Richard et al., Citation2017).

Hence, it is of societal relevance to identify psychological resources that may prevent or mitigate loneliness. In this study, the focus is on the association between trait gratitude and loneliness, and the effects of psychological flexibility and engaged living as underlying mechanisms in the association between trait gratitude and loneliness in adults of 40 years and older. These mechanisms have shown to be beneficial for increased physical and mental health and decreased psychopathological problems (Jans-Beken, Lataster, Peels, Lechner, & Jacobs, Citation2017; Kashdan & Rottenberg, Citation2010; Trompetter et al., Citation2013). This study aims to reveal more knowledge about the possible role of trait gratitude, psychological flexibility and engaged living in relation to loneliness with possible implications for developing interventions to reduce loneliness.

Trait gratitude

One potential psychological resource that may prevent or mitigate loneliness in middle-aged or older adults is trait gratitude, which is defined as a general tendency to recognize benefits, experience abundance and acknowledge anything in the world – human and not human – with grateful emotion and expression of this emotion that fosters both personal well-being and well-being of others (Jans-Beken, Citation2018). Although not studied extensively yet, previous research has demonstrated a negative association between (trait) gratitude and loneliness (Caputo, Citation2015; Ni, Yang, Zhang, & Dong, Citation2015; O'Connell, O'Shea, & Gallagher, Citation2016). Furthermore, the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson, Citation2004) posits that positive emotions, such as gratitude, can incite people to broaden their life perspective which can lead to an increase in engagement in activities and psychological flexibility in the direction of a more meaningful or value-oriented life (Froh, Bono, & Emmons, Citation2010; Ni et al., Citation2015). In the short term, grateful people will initially show prosocial behavior to express their gratitude, but in the longer term, the behavior that is motivated by gratitude can lead to building social relationships and strengthening friendships (Fredrickson, Citation2004). In addition, the find-remind-and-bind theory of gratitude elaborates on this theory (Algoe, Citation2012; Algoe & Zhaoyang, Citation2016). Gratitude ensures that a person's attention is focused on positive, valuable qualities or traits of the other or is reminded of this in that person. Simultaneously, thoughts, feelings and behaviors are aligned so that it connects both people more closely together (Algoe, Citation2012; Algoe & Zhaoyang, Citation2016). Because lonely people generally feel alienated from society, have a lack of social trust (Lamster, Lincoln, Nittel, Rief, & Mehl, Citation2017; A. Wong, Chau, Fang, & Woo, Citation2017) pay less attention to or are less involved in conversations with others (Shi, Zhang, Zhang, Fu, & Wang, Citation2016) and may show social withdrawal behavior (Qualter et al., Citation2015), it is hypothesized that trait gratitude may mitigate loneliness or may act as a buffer against loneliness (Caputo, Citation2015; Ni et al., Citation2015; O'Connell et al., Citation2016). Trait gratitude might be able to encourage older individuals to find new friends and/or to strengthen existing relationships. In this way, trait gratitude, as a positive characteristic, can build stronger social connections that can in turn alleviate feelings of loneliness.

The role of psychological flexibility and engaged living

A previous study by Von Faber et al. (Citation2001) showed that flexible coping with changes during the aging process, feeling grateful for social contacts, and an absence of marked feelings of loneliness were crucial for optimal functioning and well-being in middle-aged and older adults. Therefore, a possible pathway from gratitude to loneliness may run through psychological flexibility which is a concept derived from the Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Psychological flexibility refers to the ability to flexibly cope with adversity, thereby promoting engagement in personal meaningful or valued activities. Psychological flexibility is established through the six core processes of acceptance, defusion, being present, self as context, values and committed action which are overlapping and mutually connected. The first four processes represent the Acceptance process and the last two processes represent the Commitment process in ACT (ACT; Hayes, Luoma, Bond, Masuda, & Lillis, Citation2006).

Because previous research has demonstrated that psychological flexibility decreases with age (Boman, Lundman, Nygren, Årestedt, & Santamäki Fischer, Citation2017; Viglund et al., Citation2013), it may be beneficial for middle-aged and older adults to strengthen psychological flexibility. However, there is a gap in the literature about psychological flexibility as an underlying mechanism in the association between trait gratitude and loneliness. Moreover, little evidence is available to support the association between gratitude and psychological flexibility (Fredrickson, Citation2004; Hill, Citation2011; Kashdan & Rottenberg, Citation2010). According to the broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, Citation2004), a grateful life orientation may be related to an increase in psychological flexibility. In addition, gratitude is viewed as a life-enhancing skill that promotes psychological flexibility (Hill, Citation2011). However, limited prior research has indicated that psychological flexibility is associated with reduced feelings of loneliness (Boman et al., Citation2017; Gardiner, Geldenhuys, & Gott, Citation2018; Hamama-Raz & Hamama, Citation2015).

A process that is derived from ACT’s psychological flexibility and based on the core processes values and committed action, is engaged living (Trompetter et al., Citation2013) which is also called an ‘engaged response style’. Engaged living relates to recognizing and acknowledging personal values and the experience of completeness and satisfaction with life as the result of committed actions in accordance with personal values and life goals (Trompetter et al., Citation2013). Engaged living is correlated to having a sense of purpose in life (Trompetter, Bohlmeijer, Fox, & Schreurs, Citation2015). The experience of a sense of purpose in life persists across the life span, by providing opportunities for older adults to contribute to society with meaningful activities and sustain their social value and sense of relevance (Irving, Davis, & Collier, Citation2017). Also, the purpose in life has been associated to positive health outcomes such as having robust resilience, having faith in a higher being, and experiencing good mental and physical health (Musich, Wang, Kraemer, Hawkins, & Wicker, Citation2018). Engaged living might have similar benefits for physical, mental and social health in middle-aged and older persons.

Although not studied extensively yet, some studies revealed a negative association between engaged living and loneliness (Drageset, Eide, Dysvik, Furnes, & Hauge, Citation2015; Tam & Chan, Citation2019). A deficit in personal values in life may hinder connecting to other individuals and consequently increase feelings of loneliness (Caputo, Citation2015; Ho, Cheung, & Cheung, Citation2010). On the other hand, people who are engaged in meaningful or valued activities experience increased levels of positive affect and decreased levels of negative affect (Froh, Kashdan, et al., Citation2010), which are associated with reduced feelings of loneliness (Ditcheva, Vrshek-Schallhorn, & Batista, Citation2018). In addition, engaged living is associated with decreased psychological distress (Trindade, Ferreira, Pinto-Gouveia, & Nooren, Citation2016) that might be evident in the form of loneliness. Because living in accordance with deeply held values may be more rooted in older people (Petkus & Wetherell, Citation2013), it might be beneficial for older adults to clarify values and promote engagement in meaningful or valued activities that might prevent or mitigate the subjective experience of loneliness (Trindade et al., Citation2016).

Current study and hypotheses

This study examines the association between trait gratitude and loneliness. In addition, this study is the first to investigate the mediating role of psychological flexibility and engaged living between trait gratitude and loneliness in adults over 40 years. Based on previous research, it is hypothesized that (i) trait gratitude is negatively associated with loneliness; and (ii) the association between trait gratitude and loneliness is mediated by psychological flexibility and engaged living, respectively and combined. Thereby, it is expected that the mediating role of engaged living will be less pronounced, as engaged living can be seen as a subdomain of the overarching construct of psychological flexibility.

Method

Design and sample

This study used a cross-sectional survey design with quantitative data collection. A survey was presented to a random sample of the Dutch population using the snowball sampling method. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) at least 40 years and older; (b) residing in the Netherlands and (c) sufficient knowledge of the Dutch language. The sample consisted of 203 participants. In total, 39 participants were excluded from the analysis due to missing data in one of the presented questionnaires and one participant did not meet the age inclusion criterion, being younger than 40 years. The total sample thus consisted of 163 participants (Mage = 66, SDage = 12, range 41–92) of which 65 men (40%) and 98 women (60%). The educational level varied from primary school to a graduate degree, with 88 (54%) participants having a lower or middle educational level and 75 (46%) participants having a higher educational level. Post-hoc power analysis with WebPower (Zhang & Yuan, Citation2018) in R (R Core Team, Citation2014) showed that power >.90 was reached with this sample.

Procedure

Participants were recruited through face-to-face contact and social media. Those who were interested in participation received an email with an accompanying information letter. They also received the request to fill out the questionnaires through an online survey (Limesurvey version 2.06). For those who had no computer at their disposal or insufficient computer skills, a paper version of the survey was offered, including an enclosed envelope that could be returned to the researcher. Before filling out the questionnaires, the participants were asked to sign an informed consent. Furthermore, the participants were informed about the time that completing the questionnaires would take. In addition, it was stated that all data would be treated strictly anonymously, and that participation was voluntary. This study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Open University (reference number: U2017/09465/HVM).

Measures

Gratitude

To assess disposition towards gratitude, the validated Dutch version of the Short Gratitude, Resentment, and Appreciation Test was used, consisting of 16 items (SGRAT-NL; Jans-Beken, Lataster, Leontjevas, & Jacobs, Citation2015). Participants rated the responses to items such as ‘Life has been good for me’ and ‘I think that it's important to pause often to “count my blessings” on a 9-point Likert scale ranging from “I strongly disagree” (1) to “I strongly agree” (9).’ The negatively formulated items were reverse coded. The average total score ranges from 1 to nine with a high score indicating a higher level of gratitude in daily life. Cronbach’s α in the current study was high with α = .86, and comparable to previous studies (Jans-Beken et al., Citation2015).

Psychological flexibility

The Flexibility Index Test (FIT-60) is a validated Dutch 60-item self-report questionnaire measuring psychological flexibility (FIT-60; Batink, Jansen, & de Mey, Citation2012). The FIT-60 is divided into six subscales with items such as ‘Worry stands in the way of my success,’ ‘My thoughts give me discomfort or emotional pain’ that are rated on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from (0) ‘totally disagree’ to (6) ‘totally agree.’ However, as the items 13 and 34 are work related items, they are generally no longer relevant for the elderly. Hence, when a participant did not complete these items, the missing value was replaced by the group mean imputation. Negatively formulated items were reverse coded. The average total score ranges from 0 to six with a high score indicating a higher level of psychological flexibility. Cronbach’s α of the FIT-60 scale in this study is α = .93. A previous study (Batink et al., Citation2012) showed a comparable internal consistency (α = .95) as well a high convergent construct validity and a moderate divergent construct validity.

Engaged living

Participants completed the 16-item Engaged Living Scale that measures valued living (i.e. the two core processes ‘values’ and ‘committed actions’ from the ACT model) and the process of life fulfillment. Engaged living is related to recognize and acknowledge personal values and committed actions to reach for life goals according to these personal values. Life fulfillment refers to the experience of completeness and satisfaction with life as the result of valued living (ELS; Trompetter et al., Citation2013). Each item (e.g. ‘I know what motivates me in life’ and ‘I feel that I am living a full life’) is scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranges from ‘strongly disagree’ (1) to ‘strongly agree’ (5). The average total score ranges from 1 to 5, with a high score indicating a higher engagement in meaningful or valued life activities. The Chronbach's α in this study is high, α = .95 and the ELS was previously found to be a reliable and valid measure (Trompetter et al., Citation2013).

Loneliness

Loneliness was measured with the Loneliness Questionnaire (LQ; De Jong Gierveld & Van Tilburg, Citation1999). The total scale consists of 11 items which are divided into the two subscales emotional and social loneliness. The responses to the items such as ‘There are many people I can trust completely’ and ‘I miss having a really close friend,’ were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from ‘yes!’ (1) to ‘no!’ (5). The negatively formulated items were reverse coded. An average total score (sum of individual scores on the LQ items/11) was used, ranging from 1 to five with a high score indicating a higher level of perceived loneliness. Cronbach’s α for the current study was high with α = .94 for the total score. Previous research has shown that the LQ is a reliable and valid instrument (De Jong Gierveld & Van Tilburg, Citation1999; Penning, Liu, & Chou, Citation2014).

Data analysis

SPSS version 24.0 was used for data analysis. Descriptive analyses were performed to calculate mean, standard deviation, Cronbach’s alpha and Pearson’s correlation. PROCESS v.3.1 (Hayes, Citation2018) was used to assess the association between trait gratitude, psychological flexibility, engaged living and loneliness, and the mediating role of psychological flexibility and engaged living between trait gratitude and loneliness. This was done with three different models. Model one tested the mediation between trait gratitude, psychological flexibility, and loneliness. Model two tested the mediation between trait gratitude, engaged living, and loneliness. Model three tested a mediation with two mediators. The study controlled for the demographic variables age, gender (0 = male, 1 = female) and educational level (0 = low education, 1 = high education) in all models as previous studies showed possible associations between age, gender and educational differences in the experience of loneliness (Chukwuorji, Amazue, & Ekeh, Citation2017; Hawkley & Kocherginsky, Citation2018) and gratitude (Jans-Beken et al., Citation2017). As advised by Yzerbyt, Muller, Batailler, and Judd (Citation2018), bootstrapping was performed with 50,000 resamples. The variables age, gratitude, psychological flexibility, engaged living and loneliness were transformed into z-scores to ensure comparison of the different measurement scales used. All results were interpreted against a significance threshold of 5%, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations for demographic characteristics and all study measures are presented in . Regarding demographic characteristics, there was a difference between men and women on trait gratitude with men feeling less grateful than women. Regarding the level of education, there was a difference between low and high level of education on loneliness and psychological flexibility. Higher educated individuals scored lower on the measure of loneliness and higher on psychological flexibility. Age was positively correlated with loneliness. All pairwise correlations between the study measures were significant in conceptually expected ways, i.e. trait gratitude was negatively associated with loneliness, and positively with both psychological flexibility and engaged living. Likewise, psychological flexibility and engaged living were both negatively associated with loneliness.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlations among the variables gratitude, psychological flexibility, engaged living, loneliness and the demographic variables.

Hypotheses

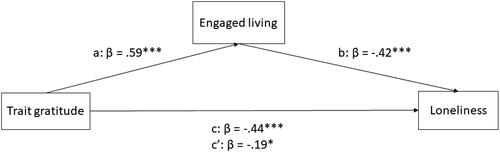

Mediation analysis of Model 1 (see ) showed that trait gratitude was positively associated with psychological flexibility (a-path: β = .58, p <. 001), and psychological flexibility was negatively associated with loneliness (b-path: β = −.59, p <. 001). The significant c-path between gratitude and loneliness (β = −.44, p < .001) was no longer significant by entering psychological flexibility as the mediator of the model (c′-path: β = −.09, p = .18).

Figure 1. The association between trait gratitude and loneliness, mediated by psychological flexibility.

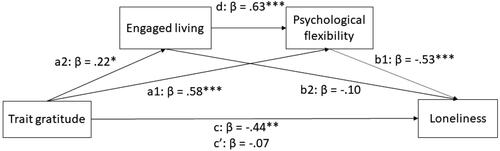

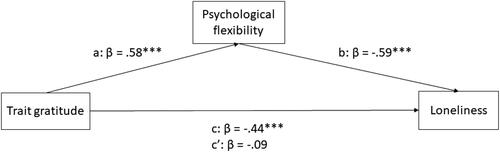

Mediation analysis of Model 2 (see ) showed that trait gratitude was positively associated with engaged living (a-path: β = .59, p <.001), and engaged living was negatively associated with loneliness (b-path: β = −.42, p < .001). The c-path between gratitude and loneliness (β = −.44, p <.001) decreased by entering engaged living as the mediator, yet, the association between gratitude and loneliness remained significant (c′-path: β = −.19, p = .03).

Mediation analysis of Model 3 (see ) showed that trait gratitude was positively associated with engaged living (a1-path: β = .22, p < .01) and psychological flexibility (a2-path: β = .58, p < .001). Engaged living was no longer associated with loneliness (b2-path: β = −.10, p > .05); only psychological flexibility was negatively associated with loneliness (b1-path: β = −.53, p < .001). The significant c-path between gratitude and loneliness (β = −.44, p < .001) was no longer significant by entering both mediators to the model (c′-path: β = −.07, p > .05). Engaged living and psychological flexibility were strongly associated (d-path: β = .63, p < .001). The model is presented in .

Discussion

This study is the first to examine psychological flexibility and engaged living as underlying mechanisms in the relation between trait gratitude and loneliness in a Dutch population of 40 years and older. The findings of the current study showed a negative association between trait gratitude and loneliness, consistent with prior research (Caputo, Citation2015; Ni et al., Citation2015; O'Connell et al., Citation2016). Evidently, adults of 40 years and older who felt more grateful in everyday life experienced less feelings of loneliness. A plausible theoretical account for this association is derived from the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions (Fredrickson, Citation2004) and the find-remind-and-bind theory of gratitude (Algoe, Citation2012). These theories argue that gratitude can increase communication, bind people closer together, and foster social relationships (Algoe, Citation2012; Fredrickson, Citation2004). In addition, gratitude can engender an upstream reciprocity; an increase in gratitude in the moment can promote an increase in helpfulness towards strangers, which can have a positive influence on building new social relationships (Stellar et al., Citation2017). Therefore, it is assumed that trait gratitude is a potential psychological resource that may mitigate or prevent loneliness in adults over 40 years.

Furthermore, the results showed that the association between trait gratitude and loneliness was fully mediated by psychological flexibility. By adding psychological flexibility as a possible underlying mechanism in the relation between trait gratitude and loneliness, there is no longer a significant relation between these two concepts. This implicates that psychological flexibility can be seen as an important underlying mechanism with significant associations with both trait gratitude and loneliness. Findings in limited prior research support a positive association between gratitude and psychological flexibility (Fredrickson, Citation2004; Hill, Citation2011; Kashdan & Rottenberg, Citation2010) and a negative association between psychological flexibility and loneliness (Boman et al., Citation2017; Gardiner et al., Citation2018; Hamama-Raz & Hamama, Citation2015). In addition, results revealed that engaged living partly mediates the association between gratitude and loneliness in middle-aged and older adults when it is included as a single mediator. As with psychological flexibility, prior research supports the positive association between gratitude and engaged living (Drageset et al., Citation2015; Froh, Emmons, Card, Bono, & Wilson, Citation2011) and the negative association between engaged living and loneliness (Froh, Kashdan, et al., Citation2010; Tam & Chan, Citation2019). When including engaged living as a second mediator next to psychological flexibility, the association between engaged living and loneliness disappears because psychological flexibility is fully mediating the association between trait gratitude and loneliness. This is an indication that just engaged living is not sufficient as an explaining mechanism of the relation between trait gratitude and loneliness. Grateful individuals seem to be motivated to act in social and prosocial ways (Froh, Bono, et al., Citation2010) in line with their values and directing their attention towards others, which increases their social interactions and might reduce the chance of feeling lonely. However, as the findings of this study suggest, psychological flexibility as the concept of both the acceptance and the commitment process in the ACT model, seems even more pronounced as underlying mechanism in the relation between gratitude and loneliness. Grateful individuals may have learned to accept that life can be good but also that life knows times of suffering, and they understand situations, their own identity and other people in association with their selves (P. T. P. Wong, Citation2012). Gratitude is thought to be a mindful appreciation of both present and past events, with an increased attentiveness to the internal and external surroundings (Catalino & Fredrickson, Citation2011; Emmons & Mishra, Citation2011) and in this way match with the four core processes of the acceptance process of the ACT model acceptance, defusion, being present, and self as context. This study suggests that gratitude can support psychological flexibility based on the ACT model, although the causality of this relation needs to be addressed in future studies.

The broaden-and-build theory (Fredrickson, Citation2004) as mentioned earlier posits that gratitude can motivate people to broaden their life perspective that can embolden people to clarify personal values and promote engagement in meaningful or valued life activities, which may lead to a decrease in negative affect, and an increase in positive affect (Froh, Kashdan, et al., Citation2010), life satisfaction and happiness (Van Oyen-Witvliet, Richie, Root-Luna, & Van Tongeren, Citation2018) and might mitigate or prevent loneliness in adults over 40 years. The present study indicates that trait gratitude as a positive characteristic adds to the psychological flexibility as a personal resource to handle challenges in later life; trait gratitude supports the personal resources necessary to act in a flexible way and thereby alleviating social isolation.

Interesting is also to link other empirical findings for example regarding engagement and disengagement strategies across the life span to psychological flexibility and the ACT model. It is assumed that goal engagement strategies are especially important during younger age when there are a lot of opportunities for goal attainment. By increasing age, more constraints on goal attainment will be encountered due to for example a decline in physical or cognitive functioning or social changes. This may be faced more functionally with disengagement strategies (Barlow, Wrosch, Heckhausen, & Schulz, Citation2016). Psychological flexibility includes acceptance of inevitable feelings and circumstances and adapting in a flexible way. Further research could be directed to investigate the link between psychological flexibility and (dis)engagement strategies.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study that should be considered. First, and most important, is that because of the cross-sectional design of this study, no statements can be made about causality. For testing causalities is it recommended to use longitudinal, experimental studies. Second, the sample was right skewed on loneliness; most of the participants did not report feeling lonely at a high level. This is in line with the distribution of loneliness in the general population of middle-aged and older adults. However, the findings of this study apply to relatively social active individuals and cannot be generalized to individuals with high levels of loneliness. Another limitation regarding the generalizability of the results is that although a snowball sampling method was used to include participants for this study, this may have resulted in a selective sample. Future work is advised to obtain a more diverse sample in order to engender generalizability of the test results.

Conclusion and implications

The present study examined the association between trait gratitude and loneliness, and was the first to examine the mediating role of psychological flexibility and engaged living between trait gratitude and loneliness in adults of 40 years and older. Knowledge about these associations is of societal relevance to identify psychological resources that may prevent or mitigate loneliness. The results show that an increase in trait gratitude is associated with a decrease in loneliness in this age group. Moreover, both psychological flexibility and engaged living are important underlying mechanisms in the association between trait gratitude and loneliness in adults of 40 years and older.

The present study entails several theoretical implications and directions for further research. First, this study contributes to the small amount of existing work on the association between trait gratitude, psychological flexibility, engaged living, and loneliness and adds to the increasing research and clinical applications of ACT. The findings imply that trait gratitude and psychological flexibility are important psychological resources in relation to experiencing less loneliness. Further research is needed to replicate these findings in a more diverse sample and investigate the causal relationships between these constructs by following individuals over a longer period. This could be done for example with intervention studies investigating the effect of existing interventions (based on gratitude exercises or ACT model) on symptoms of loneliness. It would also be interesting to include the role of different age groups and goal (dis)engagement strategies in future research.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all participants for their contribution to this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This research did not receive any funding from agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Algoe, S. B. (2012). Find, remind, and bind: The functions of gratitude in everyday relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(6), 455–469.

- Algoe, S. B., & Zhaoyang, R. (2016). Positive psychology in context: Effects of expressing gratitude in ongoing relationships depend on perceptions of enactor responsiveness. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(4), 399–415.

- Batink, T., Jansen, G., & de Mey, H. R. A. (2012). De Flexibiliteits Index Test (FIT 60): Een beknopte beschrijving. GZ – Psychologie, 5, 18–21.

- Barlow, M., Wrosch, C., Heckhausen, J., & Schulz, R. (2016). Control strategies for managing physical health problems in old age: Evidence for the motivational theory of life-span development. In J. W. Reich & F. J. Infurna (Eds.), Perceived control: Theory, research, and practice in the first 50 years. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Boman, E., Lundman, B., Nygren, B., Årestedt, K., & Santamäki Fischer, R. (2017). Inner strength and its relationship to health threats in ageing: A cross-sectional study among community‐dwelling older women. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(11), 2720–2729.

- Brimelow, R. E., & Wollin, J. A. (2017). Loneliness in old age: Interventions to curb loneliness in long-term care facilities. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 41(4), 301–315.

- Caputo, A. (2015). The relationship between gratitude and loneliness: The potential benefits of gratitude for promoting social bonds. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 11(2), 323–334.

- Catalino, L. I., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2011). A Tuesday in the life of a flourisher: The role of positive emotional reactivity in optimal mental health. Emotion, 11(4), 938–950.

- Christiansen, J., Larsen, F. B., & Lasgaard, M. (2016). Do stress, health behavior, and sleep mediate the association between loneliness and adverse health conditions among older people?. Social Science & Medicine, 152, 80–86.

- Chukwuorji, J. C., Amazue, L. O., & Ekeh, O. H. (2017). Loneliness and psychological health of orthopaedic patients' caregivers: Does gender make a difference? Psychology. Health & Medicine, 22(4), 501–506.

- De Jong Gierveld, J., Keating, N., & Fast, J. E. (2015). Determinants of loneliness among older adults in Canada. Canadian Journal on Aging/La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement, 34(2), 125–136.

- De Jong Gierveld, J., & Van Tilburg, T. G. (1999). Manual of the loneliness scale. VU University, Faculty of Social Sciences, Department of Sociology. Retrieved from https://home.fsw.vu.nl/tg.van.tilburg/manual_loneliness_scale_1999.html

- Ditcheva, M., Vrshek-Schallhorn, S., & Batista, A. (2018). People who need people: Trait loneliness influences positive affect as a function of interpersonal context. Biological Psychology, 136, 181–188.

- Drageset, J., Eide, G., Dysvik, E., Furnes, B., & Hauge, S. (2015). Loneliness, loss, and social support among cognitively intact older people with cancer, living in nursing homes – A mixed-methods study. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 10, 1529–1536.

- Emmons, R. A., & Mishra, A. (2011). Why gratitude enhances well-being: What we know, what we need to know. In K. M. Sheldon, T. B. Kashdan, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Designing positive psychology: Taking stock and moving forward (pp. 248–262). Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Eurostat. (2017). Do Europeans feel lonely? Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20170628-1.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds. In R. A. Emmons & M. E. McCullough (Eds.), The psychology of gratitude (pp. 145–166). New York: Oxford University Press

- Froh, J. J., Bono, G., & Emmons, R. (2010). Being grateful is beyond good manners: Gratitude and motivation to contribute to society among early adolescents. Motivation and Emotion, 34(2), 144–157.

- Froh, J. J., Emmons, R. A., Card, N. A., Bono, G., & Wilson, J. A. (2011). Gratitude and the reduced costs of materialism in adolescents. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(2), 289–302.

- Froh, J. J., Kashdan, T. B., Yurkewicz, C., Fan, J., Allen, J., & Glowacki, J. (2010). The benefits of passion and absorption in activities: Engaged living in adolescents and its role in psychological well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(4), 311–332.

- Gan, P., Xie, Y., Duan, W., Deng, Q., & Yu, X. (2015). Rumination and loneliness independently predict six-month later depression symptoms among Chinese elderly in nursing homes. PLoS One, 10(9), e0137176.

- Gardiner, C., Geldenhuys, G., & Gott, M. (2018). Interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness among older people: An integrative review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(2), 147–157.

- Hamama-Raz, Y., & Hamama, L. (2015). Quality of life among parents of children with epilepsy: A preliminary research study. Epilepsy and Behavior, 45, 271–276.

- Hawkley, L. C., & Kocherginsky, M. (2018). Transitions in loneliness among older adults: A 5-year follow-up in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. Research on Aging, 40(4), 365–387.

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). The PROCESS macro for SPSS and SAS. Retrieved from http://www.processmacro.org/index.html.

- Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44(1), 1–25.

- Hegeman, A., Schutter, N., Comijs, H., Holwerda, T., Dekker, J., Stek, M., & Van der Mast, R. (2018). Loneliness and cardiovascular disease and the role of late-life depression: Loneliness and cardiovascular disease. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 33(1), e65–e72.

- Hill, R. D. (2011). A positive aging framework for guiding geropsychology interventions. Behavior Therapy, 42(1), 66–77.

- Ho, M. Y., Cheung, F. M., & Cheung, S. F. (2010). The role of meaning in life and optimism in promoting well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(5), 658–663.

- Huang, L., Du, W., Liu, Y., Guo, L., Zhang, J., Qin, M., & Liu, K. (2019). Loneliness, stress, and depressive symptoms among the Chinese rural empty nest elderly: A moderated mediation analysis. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(1), 73–78.

- Irving, J., Davis, S., & Collier, A. (2017). Aging with purpose: Systematic search and review of literature pertaining to older adults and purpose. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 85(4), 403–437.

- Jans-Beken, L. (2018). Appreciating gratitude: New perspectives on the gratitude-mental health connection. (Doctoral dissertation), Open University, Heerlen.

- Jans-Beken, L., Lataster, J., Leontjevas, R., & Jacobs, N. (2015). Measuring gratitude: A comparative validation of the Dutch Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ6) and Short Gratitude, Resentment, and Appreciation Test (SGRAT). Psychologica Belgica, 55(1), 19–31.

- Jans-Beken, L., Lataster, J., Peels, D., Lechner, L., & Jacobs, N. (2017). Gratitude, psychopathology and subjective well-being: Results from a 7.5-month prospective general population study. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(6), 1–17.

- Kashdan, T. B., & Rottenberg, J. (2010). Publisher note to “psychological flexibility as a fundamental aspect of health. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 865–878.

- Kharicha, K., Iliffe, S., Manthorpe, J., Chew‐Graham, C. A., Cattan, M., Goodman, C., … Walters, K. (2017). What do older people experiencing loneliness think about primary care or community based interventions to reduce loneliness? A qualitative study in England. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(6), 1733–1742.

- Lamster, F., Lincoln, T., Nittel, C., Rief, W., & Mehl, S. (2017). The lonely road to Paranoia. A path-analytic investigation of loneliness and Paranoia. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 74, 35–43.

- Menec, V., Newall, N., Mackenzie, C., Shooshtari, S., & Nowicki, S. (2019). Examining individual and geographic factors associated with social isolation and loneliness using Canadian Longitudinal Study on Aging (CLSA) data. PLoS One, 14(2), e0211143.

- Musich, S., Wang, S. S., Kraemer, S., Hawkins, K., & Wicker, E. (2018). Purpose in life and positive health outcomes among older adults. Population Health Management, 21(2), 139–147.

- Ni, S., Yang, R., Zhang, Y., & Dong, R. (2015). Effect of gratitude on loneliness of Chinese college students: Social support as a mediator. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 43(4), 559–566.

- Niedzwiedz, C. L., Richardson, E. A., Tunstall, H., Shortt, N. K., Mitchell, R. J., & Pearce, J. R. (2016). The relationship between wealth and loneliness among older people across Europe: Is social participation protective?. Preventive Medicine, 91, 24–31.

- Niu, L., Jia, C., Ma, Z., Wang, G., Yu, Z., & Zhou, L. (2018). The validity of proxy-based data on loneliness in suicide research: A case-control psychological autopsy study in rural China. Bmc Psychiatry, 18(1), 116–118.

- O'Connell, B. H., O'Shea, D., & Gallagher, S. (2016). Mediating effects of loneliness on the gratitude-health link. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 179–183.

- Pavlickova, A., & Nagyova, I. (2016). Meeting the challenge of ageing and multimorbidity. European Journal of Public Health, 26(suppl_1), 274–274.

- Penning, M. J., Liu, G., & Chou, P. H. B. (2014). Measuring loneliness among middle-aged and older adults: The UCLA and de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scales. Social Indicators Research, 118(3), 1147–1166.

- Petkus, A., & Wetherell, J. (2013). Acceptance and commitment therapy with older adults: Rationale and considerations. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(1), 47–56.

- Qualter, P., Vanhalst, J., Harris, R., Van Roekel, E., Lodder, G., Bangee, M., … Verhagen, M. (2015). Loneliness across the life span. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 250–264.

- R Core Team. (2014). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

- Richard, A., Rohrmann, S., Vandeleur, C., Schmid, M., Barth, J., & Eichholzer, M. (2017). Loneliness is adversely associated with physical and mental health and lifestyle factors: Results from a Swiss National Survey. PLoS One, 12(7), e0181442.

- Rijksinstituut voor Volksgezondheid en Milieu. (2016). Eenzaamheid: cijfers en context: huidige situatie. Retrieved from https://www.volksgezondheidenzorg.info/onderwerp/eenzaamheid/cijfers-context/huidige-situatie-definitie–node-wat-eenzaamheid.

- Russell, D., Cutrona, C. E., Rose, J., & Yurko, K. (1984). Social and emotional loneliness: An examination of Weiss's typology of loneliness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46(6), 1313–1321.

- Shi, R., Zhang, S., Zhang, Q., Fu, S., & Wang, Z. (2016). Experiential avoidance mediates the association between emotion regulation abilities and loneliness. PLoS One, 11(12), e0168536.

- Stellar, J. E., Gordon, A. M., Piff, P. K., Cordaro, D., Anderson, C. L., Bai, Y., … Keltner, D. (2017). Self-transcendent emotions and their social functions: Compassion, gratitude, and awe bind us to others through prosociality. Emotion Review, 9(3), 200–207.

- Stickley, A., & Koyanagi, A. (2016). Loneliness, common mental disorders and suicidal behavior: Findings from a general population survey. Journal of Affective Disorders, 197, 81–87.

- Tam, K. Y. Y., & Chan, C. S. (2019). The effects of lack of meaning on trait and state loneliness: Correlational and experience-sampling evidence. Personality and Individual Differences, 141, 76–80.

- Trindade, I. A., Ferreira, C., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Nooren, L. (2016). Clarity of personal values and committed action: Development of a shorter engaged living scale. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(2), 258–265.

- Trompetter, H. R., Bohlmeijer, E. T., Fox, J.-P., & Schreurs, K. M. G. (2015). Psychological flexibility and catastrophizing as associated change mechanisms during online acceptance & commitment therapy for chronic pain. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 74, 50–59.

- Trompetter, H. R., Ten Klooster, P. M., Schreurs, K. M. G., Fledderus, M., Westerhof, G. J., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2013). Measuring values and committed action with the engaged living scale (ELS): Psychometric evaluation in a nonclinical and chronic pain sample. Psychological Assessment, 25(4), 1235–1246.

- Valtorta, N. K., Kanaan, M., Gilbody, S., & Hanratty, B. (2018). Loneliness, social isolation and risk of cardiovascular disease in the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 25(13), 1387–1396.

- Van Oyen-Witvliet, C., Richie, F. J., Root-Luna, L. M., & Van Tongeren, D. R. (2018). Gratitude predicts hope and happiness: A two-study assessment of traits and states. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(3), 1–12.

- Viglund, K., Jonsen, E., Lundman, B., Strandberg, G., Nygren, B., & Health, A. M. (2013). Inner strength in relation to age, gender and culture among old people – A cross-sectional population study in two Nordic countries. Aging & Mental Health, 17(8), 1016–1022.

- von Faber, M., Bootsma–van der Wiel, A., van Exel, E., Gussekloo, J., Lagaay, A. M., van Dongen, E., … Westendorp, R. G. J. (2001). Successful aging in the oldest old: Who can be characterized as successfully aged?. Archives of Internal Medicine, 161(22), 2694–2700.

- Wolf, L., & Davis, M. (2014). Loneliness, daily pain, and perceptions of interpersonal events in adults with fibromyalgia. Health Psychology, 33(9), 929–937.

- Wong, A., Chau, A., Fang, Y., & Woo, J., (2017). Illuminating the psychological experience of elderly loneliness from a societal perspective: A qualitative study of alienation between older people and society. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 14(7), 824–819.

- Wong, P. T. P. (2012). Toward a dual-systems model of what makes life worth living. In P. T. P. Wong (Ed.), The human quest for meaning (pp. 49–68). Abingdon-on-Thames, UK: Routlegde

- Wong, P. T. P. (2016). Integrative meaning therapy: From logotherapy to existential positive interventions. In P. Russo-Netzer, S. E. Schulenberg, & B. A. (Eds.), Clinical perspectives on meaning: Positive and existential psychotherapy (pp. 323–342). New York: NY: Springer.

- Yzerbyt, V., Muller, D., Batailler, C., & Judd, C. M. (2018). New recommendations for testing indirect effects in mediational models: The need to report and test component paths. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 115(6), 929.

- Zhang, Z., & Yuan, K. (2018). Practical statistical power analysis using WebPower and R. Granger. IN: ISDSA Press.[Google Scholar].