Abstract

Objectives

There are a number of conceptual models of dementia, capturing a range of biopsychosocial factors. Few integrate the lived experience of dementia. The aim of this study was to develop a conceptualisation grounded in the first-hand accounts of living with the condition and reflecting its complexity.

Method

The study was conducted within an explanatory, critical realist paradigm. An overarching narrative approach, informed by a previously completed systematic review and metasynthesis of research on the lived experience of dementia and the assumptions of complexity theory, was used to guide data collection and analysis. Data were contributed by 31 adults, including 12 people living with dementia and 19 family caregivers.

Results

The experience of living with dementia was conceptualised as a process of adaptation through participation, emerging from ongoing, dynamic and nonlinear interactions between the adaptive capacity of a person with dementia and the adaptive capacity within the environment. The proposed conceptual model describes contexts and mechanisms which shape this capacity. It identifies a range of potential outcomes in dementia. These outcomes reflect interactions and the degree of match between the adaptive capacity of a person and the adaptive capacity within the environment.

Conclusion

By recognising and exploring the potential for adaptation and enduring participation in dementia, findings of this research can support practitioners in facilitating positive outcomes for people affected by the condition.

Introduction

This research seeks to contribute a conceptual model of dementia reflective of lived experience. It is anticipated that this model can support practitioners in facilitating positive outcomes.

Polarisation of conceptual positions

Thinking about dementia has been dominated by biomedical models, which explain symptoms in relation to neuropathology (Cheung, Chien, & Lai, Citation2011). However, despite contributions to the understanding of the neurological aspects of dementia and efforts to manage symptoms (Cheung et al., Citation2011), researchers within the social model of disability argued that the biomedical models do not offer a comprehensive account of the condition (Downs, Clare, & MacKenzie, Citation2006).

This critique led to research efforts aiming to understand factors determining people’s experience of dementia. As a result, conceptualisations of dementia evolved to incorporate biological, psychological and social domains (e.g. Kales, Gitlin, & Lyketsos, Citation2015; Kitwood, Citation1997; Sabat & Harré, Citation1992; Spector & Orrell, Citation2010). The biopsychosocial view has been influential in empowering people with dementia to challenge accepted constructions of their experience (Dorenlot, Citation2005) and triggered a drive for change (Innes & Manthorpe, Citation2013). However, just like the biomedical understanding, biopsychosocial models have been contested as limiting (Zwijsen, Van der Ploeg, & Hertogh, Citation2016), with Dewing (Citation2008) arguing that they fail to fully deal with the notion of embodiment and its importance.

Such polarisation of conceptual positions in relation to dementia is unhelpful and inaccurate (Manthorpe & Iliffe, Citation2016; Zwijsen et al., Citation2016), particularly in light of research evidence showing the malleability of a nervous system in contact with the environment (neuroplasticity) (Vance, Roberson, McGuinness, & Fazeli, Citation2010). As a result, the need for fresh conceptualisations of dementia, incorporating the lived experience and capturing its complexity, has been increasingly recognised (Dewing, Citation2019; Manthorpe & Iliffe, Citation2016; Zwijsen et al., Citation2016).

First-hand experience

Theoretical conceptualisations shape professional approaches to care and socio-cultural attitudes towards people with dementia (Innes & Manthorpe, Citation2013), with implications for stigma, reduced mental health and wellbeing (Riley, Burgener, & Buckwalter, Citation2014). Existing conceptualisations are dominated by knowledge based on professional expertise, rather than personal experiences (Bartlett & O’Connor, Citation2010). This is because, for a long time, due to the assumption of diminished competence, people with dementia were excluded from academic and clinical discourse (Rabins, Kasper, Kleinman, Black, & Patrick, Citation1999). This exclusion narrowed explanatory potential of research and deprived people with dementia of participation in the development of knowledge that influences their experience (Bartlett & O’Connor, Citation2010; Dewing, Citation2019; Swaffer, Citation2014; Zeilig, Citation2013).

It is recognised that, in order to truly move towards person-centred care and ethics, our understanding of dementia must incorporate the lived experience (Dewing, Citation2019; Estey-Burtt & Baldwin, Citation2014; Swaffer, Citation2014). This will facilitate consideration of “complex configurations of a person’s values, wishes, needs, context, web of relationships, situated-ness in terms of history and place, and their desired trajectory(ies)” (Estey-Burtt & Baldwin, Citation2014, p. 59); alongside existing theoretical explanations (Dewing, Citation2019). Over the last two decades, due to better understanding of issues pertaining to insight, awareness and competence (Clare, Citation2004; Howorth & Saper, Citation2003; Trigg, Jones, & Skevington, Citation2007) and emerging contributions of people with the lived experience (e.g. Bryden, Citation2015; Swaffer, Citation2016; Taylor, Citation2006), research on the lived experience has been growing (e.g. Karlsson, Savenstedt, Axelsson, & Zingmark, Citation2014; Lawrence, Samsi, Banerjee, Morgan, & Murray, Citation2011). However, due to the predominantly descriptive/interpretive nature of individual studies, their potential to inform theoretical developments has not been realised (Górska, Forsyth, & Maciver, Citation2018).

Recently, this research has been subject to metasynthesis (Górska et al., Citation2018), indicating that people’s experience is shaped by multiple personal and environmental factors which remain in a constant, transactional relationship to each other and determine the way people adjust over time. This is in line with complexity theory which considers experience from multiple levels, from molecular to cultural, views development as emergent, non-linear and multi-determined, and provides theoretical principles for understanding the process of change (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1994; DiCorcia & Tronick, Citation2011; Gurland & Gurland, Citation2009; Keenan, Citation2010, Citation2011; Kielhofner, Citation2008; Roy & Andrews, Citation1999; Schroots, Citation1995; Szanton, Gill, & Thorpe, Citation2010; Thelen, Citation2005; Townsend & Polatajko, Citation2013; World Health Organisation (WHO), 2001). However, although the aforementioned metasynthesis was informative in identifying key personal and environmental factors affecting people’s experience and recognising adaptive behaviours that people engage in, due to methodological limitations of the included studies, the dynamic relationships between contextual factors and mechanisms underlying adaptive behaviours could not be fully explored.

Hence, this research examines findings of a previously completed metasynthesis of research on the lived experience of dementia (Górska et al., Citation2018) against the narrative data contributed by those affected by the condition. To maintain focus on complexity, the study design was informed by realist evaluation methodologies (Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997) and relevant complexity-consistent frameworks (e.g. DiCorcia & Tronick, Citation2011; Keenan, Citation2010, Citation2011; Kielhofner, Citation2008; WHO, Citation2001). To our knowledge, this research is the first to put forward a conceptualisation of dementia built from a synthesis of contemporary literature and incorporating first-hand experience.

Methods

Design

As this study aimed to contribute a conceptual model reflective of lived experience, it was important to seek accounts of those directly affected (Bogdan & Biklen, Citation1998). Hence, we used a narrative methodology (Clandinin, Citation2013; Stanley, Citation2008) to study stories contributed by both people with dementia, hereafter referred to as ‘person/people’; and their family members, denoted as ‘caregivers’.

The analysis was informed by assumptions of critical realism, which recognises the importance of meaning and context, allowing investigation of dementia inclusive of voices of those affected by the condition as well as knowledge generated through previous research (Ritchie & Lewis, Citation2003). It emphasises the importance of and provides means for investigating mechanisms shaping outcomes, enabling the complexity of dementia to be captured (Fletcher et al., Citation2016; Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997).

Participant selection

Participants were recruited from dementia health and social care services within a local authority in central Scotland. Participants were provided with information about the study, both verbally and in writing, and granted written informed consent.

A maximum variation sampling (Patton, Citation2002) was used to facilitate recruitment of participants across the dementia spectrum. Guidance was sought from medical services and from caregivers to evaluate the ability to make an informed decision, to consent, and to participate. Only those individuals who were able to give informed consent were asked to participate.

Thirty-one adults, 12 people with dementia (38.7%) and 19 caregivers (61.3%); were recruited. This includes ten family dyads. Characteristics of all participants are summarised in and .

Table 1. Sample characteristics, people with dementia (n = 12).

Table 2. Sample characteristics, family members (n = 19).

Data collection

Interviews were designed according to Jovchelovitch and Bauer (Citation2000) guidelines which, while facilitating a spontaneous narration of participants’ experience, ensured that issues and concepts central to this research were suitably explored.

Critical realist-informed interviews require the researcher to have detailed knowledge of previous relevant research, which is tested against interview data (Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997). Accordingly, findings of previously completed metasynthesis of research on the experience of living with dementia (Górska et al., Citation2018) informed the design of the interview schedule, allowing exploration of contextual features and mechanisms affecting possible outcomes in dementia (Pawson & Tilley, Citation1997). In other words, personal and environmental factors identified through metasynthesis as shaping people’s experience of living with dementia, and relationships between these factors, were explored through narrative interviewing. Interviews were audio recorded and lasted on average 60 min. Each interview was transcribed verbatim to facilitate analysis.

Data analysis

The analytic procedure drew on principles of narrative analysis, and incorporated two methods, ‘categorical’ and ‘holistic’ (Lieblich, Tuval-Mashiach, & Zilber, Citation1998). In the categorical approach, narratives were analysed in the search for themes and features, to identify and explore mechanisms that may lead to outcomes, and what aspect of context may matter. A framework approach (Ritchie & Spencer, Citation2002), allowing concepts derived from existing theories to be combined with concepts emerging ‘de novo’; was used as support. Analytical procedures included familiarisation, identification of thematic framework, charting themes, and mapping and interpreting data (Ritchie & Spencer, Citation2002). The approach allowed testing findings of the metasynthesis of research on the lived experience of dementia (Górska et al., Citation2018) and basic assumptions of complexity theory (e.g. DiCorcia & Tronick, Citation2011; Keenan, Citation2010, Citation2011; Kielhofner, Citation2008; WHO, Citation2001) against narrative data, while ensuring that results were grounded in participants’ perspectives.

As categorical analysis carries risk of underemphasising the unique aspects of each story (Polkinghorne, Citation1995) and may overlook the systemic and contextual character of reported experiences (Layder, Citation1998); holistic narrative analyses were also performed. This allowed consideration of participants’ accounts in their entirety (Lieblich et al., Citation1998), facilitating appreciation of temporal order, causality, motivations and choice, and contextual influences (Polkinghorne, Citation1995). This component of the analysis was informed by the realist evaluation perspective which ‘focusses on developing, testing and refining theories regarding complex causal mechanisms and how these interact with individuals’ agency and social context to produce outcomes’ (Fletcher et al., Citation2016, p. 287). Realists consider that experience (Outcome) emerges out of dynamic and complex interactions between features within individuals and their environment (Contexts), which are shaped by a range of biological, psychological and social processes (Mechanisms). Hence, the main objective in this study was to explore how different mechanisms, within different contexts, lead to adaptive or maladaptive outcomes for people affected by dementia; otherwise known as CMO configurations (Pawson, Citation2006).

Rigour

Methods used to safeguard rigour included a robust philosophical and theoretical grounding of research design; triangulation of theory, methods, sources and interpretations; contradictory case analysis; and ongoing reflexivity (Lincoln, Lynham, & Guba, Citation2011).

Ethics

The research protocol was endorsed by the South East Scotland Research Ethics Service (NR/1109AB20). The main ethical considerations included participants’ beneficence, informed consent and confidentiality. These were managed in accordance with relevant legal and policy requirements (Scottish Government, Citation2000; UK Government, Citation2005).

Results

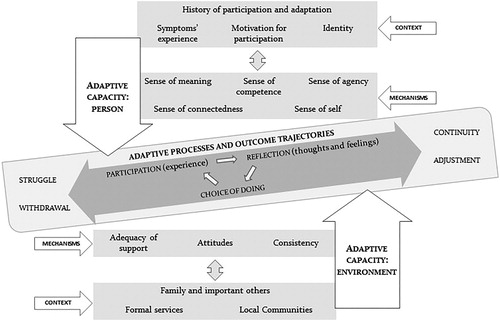

The main output of this study is the ‘Adaptation through Participation’ conceptual model, presented in . We define participation as “engagement in activities of daily living that are part of one’s sociocultural context and are necessary to one’s well-being” (Kielhofner, Citation2008, p. 101). Adaptation is conceptualised as a regulatory process activated in response to change within the person or within the environment, determined by the status of and transactional interactions between multiple factors within the person and within the environment; aimed at achieving a match between person’s needs and environmental resources/demands (DiCorcia & Tronick, Citation2011).

The three main themes identified in the study are represented in the model: (1) Adaptive capacity of a person with dementia (Context and Mechanisms); (2) Adaptive capacity within the environment (Context and Mechanisms); (3) Adaptive processes and outcome trajectories. Example narrative evidence for all themes is presented in .

Table 3. Example narrative evidence.

Theme 1: Adaptive capacity of a person with dementia (context and mechanisms)

Adaptive capacity of a person is understood as the potential within a person to adjust to internal or external changes. This capacity is underpinned by dynamic, nonlinear interactions between personal and environmental factors and mechanisms described below.

Context

We identified four interrelated contextual factors affecting people’s adaptive capacity: (1) individual history of participation and adaptation, (2) experience of symptoms, (3) motivation for participation and (4) identity.

Overall, individual history of participation and adaptation, incorporating life-long values and interests as well as previous exposure and ways of responding to challenges, was found to shape people’s adaptive responses and choices.

…my mum’s never been a big reader, because from a very young age she had to do so much work. […] She does some knitting, yes, she has got knitting on the go, she just doesnae do it as much. (Caregiver 4)

Experience of symptoms was also important. The impact of symptoms was reported to increase with their severity. Symptoms were crucial in shaping people’s motivation for participation and, in turn, their capacity to adapt. Both people with dementia and caregivers associated the experience of cognitive, psychological and physical symptoms with diminishing skills. This related to a wide range of skills and, with the progression of the condition, was reported to result in a deteriorating ability to complete activities; leading to a decreased sense of competence and, consequently, reduced motivation.

I believe I could still do things but I’ve got a fear of tackling things that I used to do before and I don’t think I can do it now for some reason. I seem to have lost… My mind doesn’t seem to work the same how I used to do all these things. (Person 4)

Another factor related to the experience of living with dementia was identity. Changes in participation did not appear to affect identity if people were able to engage in activities that were meaningful and important. But, difficulty maintaining participation in meaningful activities appeared to hinder their ability to incorporate the experienced changes into identity. Despite this, both people with dementia and caregivers reported a maintained sense of identity into advanced stages of the condition. Sense of identity influenced choices that people made in terms of participation and was a powerful mechanism determining adaptation.

R: […] there is a big change in me, I know that myself. And sometimes I feel I should kick myself out of it. I don’t think I can change myself back again. I: So what is the change about? What has changed? R: I used to be able to go out myself and things like that. I can’t do that now. (Person 1)

Mechanisms

Five mechanisms shaping the adaptive capacity were identified, these include: (1) sense of meaning, (2) sense of competence, (3) sense of agency, (4) sense of connectedness, (5) sense of self.

Sense of meaning signifies the importance and value that daily participation holds for people. It is developed over time through history of participation as individuals experience and reflect upon their engagement in activity, ‘I’ve always been interested in music and in jazz music – boogie woogie – liked the music. We used to go to symphony concerts in the [Concert Hall], which I thoroughly enjoyed’ (Person 6).

Participants indicated that sense of meaning is triggered when a person experiences enjoyment, satisfaction or a sense of achievement. It appears to be influenced by an interaction between an individual’s sense of competence, agency, connectedness and self; and the adaptive capacity within the environment.

Sense of competence reflects the degree to which individuals are confident that they have the skills required for successful participation in the activities that they wish or need to do. Sense of competence is elicited when a person experiences accomplishment. It is shaped by a dynamic interplay between experienced symptoms, meaning assigned to participation, sense of agency, connectedness and self; and the capacity of the environment to support participation. Data indicates that sense of competence might be particularly sensitive to the level of awareness experienced by a person i.e. with the progression of dementia, a person who has intact awareness may demonstrate a reduced sense of competence related to their perception of reduced skills for participation. Due to experienced symptoms and inadequate external support, a person may experience a disproportionate loss of sense of competence leading to loss of skills for participation, despite objectively preserved abilities, ‘Mum is forgetting how to do things because there's a lot of people now coming in who are doing things for her’ (Caregiver 10).

Impaired awareness may prevent people adjusting their sense of competence. They may continue to engage in activities for which they lack skills. This, combined with inadequate external support, may lead to withdrawal as a person experiences repeated failure and associates activities with negative thoughts and emotions.

Sense of agency signifies belief that one has control over the initiation and execution of activities. Findings suggest that sense of agency is activated when one experiences a sense of control in relation to choices and decisions. Although sense of agency appears to result from a dynamic interaction between experienced symptoms, sense of meaning, competence, connectedness and self; and the adaptive capacity within the environment; analysis of narrative data indicates that, in the context of dementia, personal sense of competence and the adaptive capacity within the environment play a key role.

when I go to the doctor my daughter comes with me usually, I’m sure she comes in with me to make sure what they’re tell me. […] If she didn’t come in with me and I was saying maybe I have to take [medication] every two hours and it’s maybe wrong me saying that it should be every four hours you know. (Person 4)

While a person’s sense of competence determines whether they engage in an activity; the proportionality of support, social attitudes and consistency of the environment can either support or undermine the sense of agency.

Sense of connectedness incorporates a sense of security and belief that one remains in respectful and caring relationships. In this study, sense of connectedness was found to be realised when people experience positive, consistent interactions with their environment. A dynamic interaction between experienced symptoms, sense of meaning, competence, agency and self; and the adaptive capacity within the environment influence this experience. However, it appears sensitive to memory problems and confusion, and other symptoms affecting communication and interaction, ‘I used to speak in company, I am sitting quiet. I am not taking things in as well as I used to’ (Person 2).

Sense of self refers to a composite sense of who one is, incorporating an individual’s sense of meaning, competence, agency and connectedness, reflected in typical patterns of participation and social roles and enacted within one’s environment. This was reflected in the researcher’s interaction with a 90 year old female (person 7), who had difficulty incorporating her diagnosis into her sense of self (“nothing wrong with it [my memory]”). Instead, she manifested her sense of self, incorporating her current sense of meaning, competence, agency and connectedness, in response to the researcher’s remarks about her garden which, according to her daughter, has been her lifelong passion:

[…] after the interview, when I was admiring the garden [Person 7] became quite animated. She opened the back door and showed me her garden, which she is obviously proud of. […] She explained that it’s too big for her to keep and that her son in law does the gardening for her. […] She was visibly pleased when I asked about the garden and happy to have the opportunity to show it to me. (Field notes extract)

Our findings suggest that, if the ability of a person to engage in meaningful activities and roles is supported by their personal capacities and by their environment, the sense of self remains preserved, supporting ongoing participation. If one or more components of this dynamic is compromised, one’s sense of self may be threatened which resonates in a person’s pattern of participation.

Theme 2: Adaptive capacity within the environment (context and mechanisms)

The adaptive capacity within the environment is understood in terms of a potential within the environment to adjust or be adjusted to changes occurring within it or within individuals participating in its context. The environment, in the context of this study, is understood broadly as physical, social and cultural features of one’s context (Kielhofner, Citation2008; WHO, Citation2001). In their narratives, participants across the sample referred to all these aspects. However, in the analysis, the societal and relationship features came up as strongest themes and these are emphasised in our model.

Key contextual factors reported by participants across our sample included family and important others, formal services and local communities; whereas most impactful mechanisms were: support from others, social attitudes and consistency of routine, people and places. The impact of these contextual factors and mechanisms relative to people’s experience of living with dementia has been well documented within the literature (e.g. Bosco et al., Citation2019; Brittain, Corner, Robinson, & Bond, Citation2010; Bunn et al., Citation2012; Fetherstonhaugh, Tarzia, & Nay, Citation2013; Gilmour, & Huntington, 2005; Górska et al., Citation2013; Harman & Clare, Citation2006; Holst & Hallberg, Citation2003; Langdon, Eagle, & Warner, Citation2007) and therefore will not be expanded upon here. For example narratives supporting these themes see .

Theme 3: Adaptive processes and adaptive trajectories

Adaptive processes

Based on our analysis, outcomes in dementia are influenced by on-going, dynamic interactions between contexts and mechanisms as described above. Before describing a spectrum of identified outcomes, it is important to consider the adaptive processes that lead to these outcomes.

As depicted in , when mechanisms are triggered within a personal context, they enter and influence the adaptive process, through which a person engages in participation, reflects upon the experience and, based on thoughts and feelings generated as part of this reflection, makes choices regarding future actions. This adaptive cycle within a person is also influenced by the person’s environment, with the environment in turn being influenced by the person. Outcomes in dementia depend upon the bi-directional interactions and level of “match” between the adaptive capacity of the person and the adaptive capacity within the environment, and are reflected in a person’s patterns of participation and emotional responses.

Outcome trajectories

Identified outcomes ranged between adaptive and maladaptive. Four main trajectories were identified: (1) maintaining continuity, (2) ongoing adjustment, (3) struggle and (4) withdrawal. These trajectories reflect various degrees of match between the adaptive capacity of a person and the adaptive capacity within the environment. Notably, the results indicate that outcomes in dementia reflect a spectrum rather than distinct categories. All people with dementia in the sample experienced mixed adaptive trajectories, demonstrating continuity in some and adjustment, struggle or even withdrawal in others areas of their lives. Overall an increase in maladaptive trajectories was observed and reported by the participants with the progression of the condition.

Maintaining continuity, represents a response to a change within a person or within the environment, which disrupts the pattern of participation and emotional wellbeing of a person. However, given the match between the person’s adaptive capacity and the adaptive capacity within the environment, a person is able to regain continuity.

I was just walking up and down the kitchen, I wanted to get the cooker right and I couldn’t remember what to do […]. Now I put all the washing in and that but [my husband] wants to see that things are right with the cooker. (Person 2)

Ongoing adjustment reflects the experience of a person who undergoes recurrent disruptions to their pattern of participation, caused by internal or external change. In this trajectory, the adaptive capacity of a person is not sufficiently matched by the adaptive capacity within the environment and as a result, adjustments of the internal or external factors and mechanisms are required to facilitate new or adapted forms of participation. These adjusted patterns of participation result in longer-term stability and are accompanied by overall positive emotional adaptation by a person.

I used to [do the washing] maybe only once a week but now I do it two or three times in a week […], and I’ve stopped putting it out because it’s quite a lot to get out with one hand so I just do it all in the house now. (Person 11)

Struggle reflects a mismatch between the adaptive capacity of a person and the adaptive capacity within the environment, where a person and/or others within the environment struggle to adjust and resort to coping behaviours which are not effective in terms of long-term stability. Consequently, a person experiences repeated failure, accompanied by negative emotions such as frustration, disappointment or anger. This may further compromise their adaptive capacity. As this dynamic includes environment interacting with a person, its adaptive capacity may also become compromised.

I would try and get her to change her clothes and she really would put up great resistance to this. I would say, “Your clothes are becoming grubby, you need to change, I need to wash your clothes,” and she would stubbornly refuse. That used to upset me […] (Caregiver 20)

Withdrawal reflects a recurring mismatch between the adaptive capacity of a person and the environment, leading to gradual disengagement of a person from participation. This trajectory is characterised by the experience of persistent stress and exhaustion, on the part of the person and/or the environment, meaning that successful adjustment is difficult to achieve, ‘When he’s really distressed he just goes to sleep, sometimes deliberately and sometimes I think just he’s had enough. And so, everything shuts down’ (Caregiver 18).

Discussion

The explanatory model proposed in this paper incorporates literature evidence and first-hand experience of those living with dementia as part of its conceptual representation. We have advanced the conceptual work of Górska et al. (Citation2018) and examined it against data contributed by people with dementia and their family members to develop a new conceptualisation. It comes in recognition that much of the previous theoretical work is biased towards professional expertise, limiting its explanatory potential and failing to capitalise on knowledge rooted in the lived experience (Bartlett & O’Connor, Citation2010; Dewing, Citation2019).

This is reflected in current service delivery internationally, with literature suggesting that, although the requirement for interventions to support a range of physical, psychological and social needs is recognised (Brodaty, Draper, & Low, Citation2003; National Institute for Health & Care Excellence, 2018); physical needs are more carefully assessed and remain the focus of interventions (Brodaty et al., Citation2003; Hansen, Hauge, Hellesø, & Bergland, Citation2018). This is explained by limited understanding of psychosocial needs and low availability of interventions to address these (Hansen et al., Citation2018).

Hansen et al. (Citation2018) note that psychosocial needs in dementia are predominantly perceived as related to depression, anxiety, unrest and safety and that increased knowledge is required to prevent these “sensitive needs” (p.8) from being unassessed and unfulfilled. Swaffer (Citation2014) argues that we can only develop a true picture of the needs for people with dementia through their direct inclusion in research and scholarly debate. By providing a platform for people affected by dementia to contribute to knowledge about their experience, we were able to identify a range of biopsychosocial needs related to one’s experience of symptoms, as well as sense of meaning, competence, agency, connectedness and self; which can inform the assessment and intervention planning process. These findings are supported by longstanding research highlighting the importance of meaning and selfhood (e.g. Caddell & Clare, Citation2010; Sabat Citation2001), as well as sense of competence (e.g. Clare, Citation2002; Preston, Marshall, & Bucks, Citation2007), agency (e.g. Boyle, Citation2014; Fetherstonhaugh et al., Citation2013) and meaningful relationships (e.g. Birt et al., Citation2019; Han, Radel, McDowd, & Sabata, Citation2016) for outcomes in dementia.

The focus on first-hand experience allowed recognition of ongoing participation as a context and means for adaptive processes (Imms et al., Citation2017). The relationship between the ability to engage in meaningful daily activities and wellbeing in dementia was previously recognised, but not explicitly explored relative to the adaptive potential, by Kitwood (Citation1997). A growing body of evidence emphasises the relationship between structural and functional plasticity of the brain, environmental conditions and participation (Kolanowski, Fick, Clare, Therrien, & Gill, Citation2010; Sobral, Pestana, & Paúl, Citation2015; Valenzuela & Sachdev, Citation2006, Citation2009; Vance et al., Citation2010). It has been recognised that participation in meaningful activities induces synaptic plasticity and, in longer term, structural changes in brains of those living with dementia (Kolanowski et al., Citation2010; Sobral et al., Citation2015; Valenzuela & Sachdev, Citation2006; Vance et al., Citation2010). A recent literature review (Fallahpour et al., Citation2016) concludes that participation in cognitive, physical and social activities might significantly contribute to prevention of cognitive decline in later-life; identifying phenomena of neural plasticity and brain reserve as possible explanations. Positioning the adaptive capacity in dementia in the context of participation, as suggested in our research, appears in line with these findings. Yet, although use of meaningful activity as a treatment agent is recommended within clinical guidelines internationally (Australian Government, Citation2016; NICE, Citation2018), evidence suggests that activity-based and other psychosocial interventions remain underutilized and underfunded (Hansen et al., Citation2018; Scales, Zimmerman & Miller, Citation2018). This may reflect the lack of conceptual clarity around participation.

Fallahpour et al. (Citation2016) note that the existing research exploring the relationship between participation and cognitive resilience in dementia does not account for important aspects of participation e.g. subjective experience, which may influence its role in adapting to life with the condition. The WHO (Citation2001) conceptualisation of health and disability, which recognises the importance of participation by positioning it in intersection between personal and environmental factors and the experience of a health condition, has faced similar criticism (Hemmingsson & Jonsson, Citation2005). The proposed model considers both objective (e.g. capacity for doing underpinned by individually experienced symptoms) and subjective (e.g. sense of competence, motivation, sense of self) aspects of participation; offering potential for comprehensive assessment and intervention. This is important in the context of research indicating that these factors might be particularly influential relative to treatment outcomes in dementia (Herholz, Herholz, & Herholz, Citation2013; Kolanowski, Litaker, & Buettner, Citation2005).

The proposed model corroborates knowledge rooted in professional expertise, clinical observations and/or proxy reports (Hall & Buckwalter, Citation1987; Keady et al., Citation2013; Kitwood, Citation1997; Sabat & Harré, Citation1992) or existing theoretical understandings (Bender & Cheston, Citation1997; Dröes, Citation1991; Kales et al., Citation2015; Spector & Orrell, Citation2010) by offering evidence routed in the first-hand experience. Like these models, it recognises the significance of neurodegenerative processes and positions these alongside other factors within the person and environment relative to their impact. It views an experience of living with dementia as an adaptive cycle involving dynamic interaction between the person and the environment (Bender & Cheston, Citation1997; Dröes Citation1991; Keady et al., Citation2013; Kitwood, Citation1997; Spector & Orrell, Citation2010) and supports the idea of person-environment match (Dröes Citation1991; Kales et al., Citation2015). Its unique value is in contributing knowledge reflecting the first-hand experience; knowledge that can stimulate fresh discussions in the field and open new avenues in terms of policy, practice and research.

Limitations

Triangulation of existing knowledge with the subjective perspective of dementia is a strength of this study (Finfgeld-Connett, Citation2014, Citation2016). Using realist informed methods provides strong foundations for theory development (Pawson, Citation2006). However, limitations of any model of any complex system apply equally to the model developed through this research. By default, the proposed model is reductionist – it is impossible to capture and explain all nonlinear interactions between contributory factors and mechanisms identified in this study. In fact, considering the unique character of the experience of dementia, the possibility of identifying and including all relevant factors and mechanisms is questionable (Cilliers, Citation2013).

Implications for practice, policy and research

By recognising the role of participation and the potential for adaptation in dementia the proposed model implies that, when designing interventions, greater emphasis should be placed on supporting every day, meaningful participation; rather than on isolated functional domains (Imms et al., Citation2017). This is supported by previous research recognising the value of participation as a treatment agent in dementia; one that offers far greater malleability and potential than most known risk factors such as genetics, health conditions or advancing age (Fallahpour et al., Citation2016). Yet, more research is needed to further the understanding of subjective and objective aspects of participation and, based on this knowledge, develop comprehensive assessments and interventions.

The presented model enhances understanding of contextual factors and adaptive mechanisms within both a person and the environment, which determine how people experience their symptoms, a key recently identified research priority (Khillan, Gitlin & Maslow, Citation2018). It also highlights the role of matching the adaptive capacity of a person and the adaptive capacity within the environment. As such, it does not only acknowledge the environment as a means of support (Kales et al., Citation2015), but positions it at the centre of interventions. This too is in line with recent recommendations (Khillan et al., Citation2018).

At a global policy level, documents such as the WHO Draft Global Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia (WHO, Citation2017) advocate the human rights, empowerment and engagement, and equity for people with dementia and their carers. Although, thanks to growing research on the lived experience and inspirational contributions of those directly affected (e.g. Bryden, Citation2015; Swaffer, Citation2016; Taylor, Citation2006), much has been achieved to reduce stigma (Oliver & Guss, Citation2019); evidence suggests that much remains to be done (e.g. Batsch & Mittelman, Citation2012; Garma, Citation2017; Sabat Citation2018, Citation2019; Swaffer, Citation2014). Recently, Sabat (Citation2019) argued that “malignant social psychology”, still present in our societies, “reflects misinformed thinking and the resultant malignant positioning of people with dementia” (p.62). The model presented in this paper challenges such positioning by emphasizing sense of meaning, competence, agency, connectedness and self as underpinning potential for enduring adaptation and participation throughout the dementia continuum. Indeed, the value assigned within the presented model to ongoing participation, as both the means and the outcome of adaptive processes in dementia, and the provision of a means for identifying its subjective as well as objective aspects, could inform development of more ethical and person-centred approaches of assessment and support.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of this research for their contributions. We would also like to acknowledge our colleagues within Firefly Research, Queen Margaret University Edinburgh, who offered ongoing support and feedback.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Australian Government. (2016). Clinical practice guidelines for dementia in Australia. Canberra: Cognitive Decline Partnership Centre.

- Bartlett, R., & O’Connor, D. (2010). Broadening the dementia debate: Towards social citizenship. Bristol, UK: Policy Press Scholarship Online.

- Batsch, N. L., & Mittelman, M. S. (2012). World Alzheimer Report 2012 – Overcoming the stigma of dementia. Alzheimer's Disease International. Retrieved from http://www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2012.pdf

- Bender, M. P., & Cheston, R. (1997). Inhabitants of a lost kingdom: A model of the subjective experiences of dementia. Ageing and Society, 17(5), 513–532. doi:10.1017/S0144686X97006570

- Birt, L., Griffiths, R., Charlesworth, G. M., Higgs, P. F. D., Orrell, M., Leung, P., & Poland, F. (2019). Maintaining social connections in dementia: A qualitative synthesis. Qualitative Health Research. doi:10.1177/1049732319874782

- Bogdan, R., & Biklen, S. (1998). Qualitative research for education: An introduction to theory and methods. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Bosco, A., Schneider, J., Coleston-Shields, D. M., Higgs, P., & Orrell, M. (2019). The social construction of dementia: Systematic review and metacognitive model of enculturation. Maturitas, 120, 12–22. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2018.11.009

- Boyle, G. (2014). Recognising the agency of people with dementia. Disability & Society, 29(7), 1130–1144. doi:10.1080/09687599.2014.910108

- Brittain, K., Corner, L., Robinson, L., & Bond, J. (2010). Ageing in place and technologies of place: The lived experience of people with dementia in changing social, physical and technological environments. Sociology of Health & Illness, 32(2), 272–287. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2009.01203.x

- Brodaty, H., Draper, B. M., & Low, L. F. (2003). Behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: A seven‐tiered model of service delivery. Medical Journal of Australia, 178(5), 231–234. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05169.x

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1994). Ecological models of human development. In M. Gauvain and M. Cole (Eds.), Readings on the development of children (pp. 37–43). New York: Freeman.

- Bryden, C. (2015). Nothing about us without us. London: Jassica Kingsley.

- Bunn, F., Goodman, C., Sworn, K., Rait, G., Brayne, C., Robinson, L., … Iliffe, S. (2012). Psychosocial factors that shape patient and carer experiences of dementia diagnosis and treatment: A systematic review of qualitative studies. PLoS Medicine, 9(10), e1001331. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001331

- Caddell, L. S., & Clare, L. (2010). The impact of dementia on self and identity: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(1), 113–126. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.10.003

- Cilliers, P. (2013). Understanding complex systems. In J. P. Strumberg & C. M. Martin (Eds.), Handbook of systems and complexity in health (pp. 27–38). New York: Springer Science & Business Media.

- Cheung, D. S., Chien, W. T., & Lai, C. K. (2011). Conceptual framework for cognitive function enhancement in people with dementia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20(11-12), 1533–1541. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2010.03584.x

- Clandinin, D. J. (2013). Engaging in narrative inquiry. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc.

- Clare, L. (2002). We'll fight it as long as we can: Coping with the onset of Alzheimer's disease. Aging & Mental Health, 6(2), 139–148. doi:10.1080/13607860220126826

- Clare, L. (2004). The construction of awareness in early‐stage Alzheimer's disease: A review of concepts and models. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43(2), 155–175. doi:10.1348/014466504323088033

- Dewing, J. (2008). Personhood and dementia: Revisiting Tom Kitwood’s ideas. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 3(1), 3–13. doi:10.1111/j.1748-3743.2007.00103.x

- Dewing, J. (2019). On being a person. In T. Kitwood (D. Brooker Ed.), Dementia reconsidered, revised. The person still comes first (pp.17–23). London: Open University Press.

- DiCorcia, J. A., & Tronick, E. (2011). Quotidian resilience: Exploring mechanisms that drive resilience from a perspective of everyday stress and coping. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(7), 1593–1602. doi:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.04.008

- Dorenlot, P. (2005). Editorial: Applying the social model of disability to dementia: Present-day challenges. Dementia, 4(4), 459–462.

- Downs, M., Clare, L., & MacKenzie, J. (2006). Understandings of dementia: Explanatory models and their implications for the person with dementia and therapeutic effort. In J. C. Hughes, S. J. Louw, & S. R. Sabat (Eds.), Dementia: Mind, meaning and the person (pp. 235–258). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Dröes, R. M. (1991). In Beeweging: Over Psychosociale Hulpverlening aan Demente Ouderen [In movement: On psychosocial care for people with dementia]. Academic thesis: Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit.

- Estey-Burtt, B., & Baldwin, C. (2014). Ethics in dementia care: Storied lives, storied ethics. In M. Downs, & B. Bowers (Eds.), Excellence in dementia care. Research into practice (pp.53–65). Maidenhead, England: Open University Press.

- Fallahpour, M., Borell, L., Luborsky, M., & Nygård, L. (2016). Leisure-activity participation to prevent later-life cognitive decline: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 23(3), 162–197. doi:10.3109/11038128.2015.1102320

- Fetherstonhaugh, D., Tarzia, L., & Nay, R. (2013). Being central to decision making means I am still here! The essence of decision making for people with dementia. Journal of Aging Studies, 27(2), 143–150. doi:10.1016/j.jaging.2012.12.007

- Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2014). Metasynthesis findings: Potential versus reality. Qualitative Health Research, 24(11), 1581–1591. doi:10.1177/1049732314548878

- Finfgeld-Connett, D. (2016). The future of theory-generating meta-synthesis research. Qualitative Health Research, 26(3), 291–293. doi:10.1177/1049732315616628

- Fletcher, A., Jamal, F., Moore, G., Evans, R. E., Murphy, S., & Bonell, C. (2016). Realist complex intervention science: Applying realist principles across all phases of the Medical Research Council framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions. Evaluation, 22(3), 286–303. doi:10.1177/1356389016652743

- Garma, C. T. (2017). Influence of health personnel's attitudes and knowledge in the detection and reporting of elder abuse: An exploratory systematic review. Psychosocial Intervention, 26(2), 73–91.

- Gilmour, J. A., & Huntington, A. D. (2005). Finding the balance: Living with memory loss. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 11(3), 118–124. doi:10.1111/j.1440-172X.2005.00511.x

- Górska, S., Forsyth, K., Irvine, L., Maciver, D., Prior, S., Whitehead, J., … Reid, J. (2013). Service-related needs of older people with dementia: Perspectives of service users and their unpaid carers. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(7), 1107–1114. doi:10.1017/S1041610213000343

- Górska, S., Forsyth, K., & Maciver, D. (2018). Living with dementia: A meta-synthesis of qualitative research on the lived experience. The Gerontologist, 58(3), e180–e196.

- Gurland, B. J., & Gurland, R. V. (2009). The choices, choosing model of quality of life: Description and rationale. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(1), 90–95. doi:10.1002/gps.2110

- Hall, G. R., & Buckwalter, K. C. (1987). Progressively lowered stress threshold; a conceptual model for care of adults with Alzheimer's disease. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 1(6), 399–406.

- Han, A., Radel, J., McDowd, J. M., & Sabata, D. (2016). Perspectives of people with dementia about meaningful activities: A synthesis. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementiasr, 31(2), 115–123. doi:10.1177/1533317515598857

- Hansen, A., Hauge, S., Hellesø, R., & Bergland, Å. (2018). Purchasers’ deliberations on psychosocial needs within the process of allocating healthcare services for older home-dwelling persons with dementia: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 746. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3550-7

- Harman, G., & Clare, L. (2006). Illness representations and lived experience in early-stage dementia. Qualitative Health Research, 16(4), 484–502. doi:10.1177/1049732306286851

- Hemmingsson, H., & Jonsson, H. (2005). An occupational perspective on the concept of participation in the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health—some critical remarks. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 59(5), 569–576. doi:10.5014/ajot.59.5.569

- Herholz, S. C., Herholz, R. S., & Herholz, K. (2013). Non-pharmacological interventions and neuroplasticity in early stage Alzheimer's disease. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics, 13(11), 1235–1245. doi:10.1586/14737175.2013.845086

- Holst, G., & Hallberg, I. R. (2003). Exploring the meaning of everyday life, for those suffering from dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias, 18(6), 359–365. doi:10.1177/153331750301800605

- Howorth, P., & Saper, J. (2003). The dimensions of insight in people with dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 7(2), 113–122. doi:10.1080/1360786031000072286

- Imms, C., Granlund, M., Wilson, P. H., Steenbergen, B., Rosenbaum, P. L., & Gordon, A. M. (2017). Participation, both a means and an end: A conceptual analysis of processes and outcomes in childhood disability. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 59(1), 16–25. doi:10.1111/dmcn.13237

- Innes, A., & Manthorpe, J. (2013). Developing theoretical understandings of dementia and their application to dementia care policy in the UK. Dementia, 12(6), 682–696. doi:10.1177/1471301212442583

- Jovchelovitch, S., & Bauer, M. W. (2000). Narrative interviewing. Retrieved from http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/2633.

- Kales, H. C., Gitlin, L. N., & Lyketsos, C. G. (2015). Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ, 350(mar02 7), h369. doi: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h369 doi:10.1136/bmj.h369

- Karlsson, E., Savenstedt, S., Axelsson, K., & Zingmark, K. (2014). Stories about life narrated by people with Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 70(12), 2791–2799. doi:10.1111/jan.12429

- Keady, J., Jones, L., Ward, R., Koch, S., Swarbrick, C., Hellström, I., … Williams, S. (2013). Introducing the bio‐psycho‐social‐physical model of dementia through a collective case study design. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(19-20), 2768–2777. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2012.04292.x

- Keenan, E. K. (2010). Seeing the forest and the trees: Using dynamic systems theory to understand “Stress and coping” and “Trauma and resilience. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 20(8), 1038–1060. doi:10.1080/10911359.2010.494947

- Keenan, E. K. (2011). From bumps in the road to the edge of chaos: The nature of change in adults. Journal of Social Work, 11(3), 306–325.

- Khillan, R., Gitlin, L. N., & Maslow, K. (2018). National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers. Report to the National Advisory Council on Alzheimer’s Research, Care, and Services. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/national-research-summit-care-services-and-supports-persons-dementia-and-their-caregivers.

- Kielhofner, G. (2008). Model of human occupation. Theory and application (4th ed.). Baltimore, MD: Wolters Kluwer Health, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Kolanowski, A. M., Fick, D. M., Clare, L., Therrien, B., & Gill, D. J. (2010). An intervention for delirium superimposed on dementia based on cognitive reserve theory. Aging & Mental Health, 14(2), 232–242. doi:10.1080/13607860903167853

- Kolanowski, A. M., Litaker, M., & Buettner, L. (2005). Efficacy of theory-based activities for behavioral symptoms of dementia. Nursing Research, 54(4), 219–228. doi:10.1097/00006199-200507000-00003

- Langdon, S. A., Eagle, A., & Warner, J. (2007). Making sense of dementia in the social world: A qualitative study. Social Science & Medicine, 64(4), 989–1000. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.10.029

- Lawrence, V., Samsi, K., Banerjee, S., Morgan, C., & Murray, J. (2011). Threat to valued elements of life: The experience of dementia across three ethnic groups. The Gerontologist, 51(1), 39–50. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq073

- Layder, D. (1998). Sociological practice: Linking theory and social research. London: Sage.

- Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber, T. (1998). Narrative research: Reading, analysis and interpretation. London: SAGE Publications.

- Lincoln, Y. S., Lynham, S. A., & Guba, E. G. (2011). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences, Revisited. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed., pp. 97–128). Thousand Oaks: .Sage

- Manthorpe, J., & Iliffe, S. (2016). The dialectics of dementia. Retrieved from http://www.kcl.ac.uk/sspp/policy-institute/scwru/news/2016/december.aspx#dec2.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2018). Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97.

- Oliver, K., & Guss, R. (2019). The Experience of dementia. In T. Kitwood (D. Brooker Ed.), Dementia reconsidered, revised: The person still comes first (pp.97–103). London: Open University Press.

- Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Pawson, R. (2006). Evidence-based policy: A realist perspective. London: SAGE Publications.

- Pawson, R., & Tilley, N. (1997). Realistic evaluation. London: SAGE Publications.

- Polkinghorne, D. E. (1995). Narrative configuration in qualitative analysis. In J. A. Hatch & R. Wisniewski (Eds.), Life history and narrative (pp. 5–23). London: Routledge.

- Preston, L., Marshall, A., & Bucks, R. S. (2007). Investigating the ways that older people cope with dementia: A qualitative study. Aging & Mental Health, 11(2), 131–143. doi:10.1080/13607860600844572

- Rabins, P. V., Kasper, J. D., Kleinman, L., Black, B. S., & Patrick, D. L. (1999). Concepts and methods in the development of the ADRQL: An instrument for assessing health-related quality of life in persons with Alzheimer's disease. Journal of Mental Health and Aging, 5(1), 33–48.

- Riley, R. J., Burgener, S., & Buckwalter, K. C. (2014). Anxiety and stigma in dementia: A threat to aging in place. The Nursing Clinics of North America, 49(2), 213–231. doi:10.1016/j.cnur.2014.02.008

- Ritchie, J., & Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers. London: Sage Publications.

- Ritchie, J., & Spencer, L. (2002). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In A. Bryman & R. G. Burgess (Eds.), Analysing qualitative data (pp.173–194). London: Routledge.

- Roy, C., & Andrews, H. A. (1999). The roy adaptation model (2nd ed.). Stamford, CT: Appleton & Lange.

- Sabat, S. R. (2001). The experience of Alzheimer’s disease: Life through a tangled veil. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Sabat, S. R. (2018). Alzheimer’s disease & dementia: What everyone needs to know. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Sabat, S. R. (2019). How personhood is undermined. In T. Kitwood (D. Brooker Ed.), Dementia reconsidered, revised. The person still comes first (pp.59–63). London: Open University Press.

- Sabat, S. R., & Harré, R. (1992). The construction and deconstruction of self in Alzheimer's disease. Ageing and Society, 12(4), 443–461.

- Scales, K., Zimmerman, S., & Miller, S. J. (2018). Evidence-based nonpharmacological practices to address behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. The Gerontologist, 58(suppl_1), S88–S102. doi:10.1093/geront/gnx167

- Scottish Government. (2000). Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000. Edinburgh: The Stationary Office.

- Schroots, J. J. (1995). Gerodynamics: Toward a branching theory of aging. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement, 14(1), 74–81. doi:10.1017/S0714980800010515

- Sobral, M., Pestana, M. H., & Paúl, C. (2015). The impact of cognitive reserve on neuropsychological and functional abilities in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Psychology & Neuroscience, 8(1), 39. doi:10.1037/h0101022

- Spector, A., & Orrell, M. (2010). Using a biopsychosocial model of dementia as a tool to guide clinical practice. International Psychogeriatrics, 2(6), 957–965. doi:10.1017/S1041610210000840

- Stanley, L. (2008). Madness to the method? Using a narrative methodology to analyse large-scale complex social phenomena. Qualitative Research, 8(3), 435–447. doi:10.1177/1468794106093639

- Swaffer, K. (2014). Dementia: Stigma, language, and dementia-friendly. Dementia, 13(6), 709–716. doi:10.1177/1471301214548143

- Swaffer, K. (2016). What the hell happened to my brain?: living beyond dementia. London: Jessica Kingsley. doi:10.1177/1471301218760120

- Szanton, S. L., Gill, J. M., & Thorpe, R. (2010). The society-to-cells model of resilience in older adults. Annual Review of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 30(1), 5–34.

- Taylor, R. (2006). Alzheimer’s from the inside out. Baltimore, MD: Health Professions Press.

- Thelen, E. (2005). Dynamic systems theory and the complexity of change. Psychoanalytic Dialogues, 5(2), 255–283. doi:10.1080/10481881509348831

- Townsend, E. A., & Polatajko, H. J. (2013). Enabling occupation II: Advancing an occupational therapy vision for health, well-being, & justice through occupation (2nd ed.). Ottawa: Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists.

- Trigg, R., Jones, R. W., & Skevington, S. M. (2007). Can people with mild to moderate dementia provide reliable answers about their quality of life? Age and Ageing, 36(6), 663–669. doi:10.1093/ageing/afm077

- UK Government. (2005). Mental capacity Act 2005. London: The Stationary Office.

- Valenzuela, M. J., & Sachdev, P. (2006). Brain reserve and dementia: A systematic review. Psychological Medicine, 36(4), 441–454. doi:10.1017/S0033291705006264

- Valenzuela, M., & Sachdev, P. (2009). Can cognitive exercise prevent the onset of dementia? Systematic review of randomized clinical trials with longitudinal follow-up. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 17(3), 179–187. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181953b57

- Vance, D. E., Roberson, A. J., McGuinness, T. M., & Fazeli, P. L. (2010). How neuroplasticity and cognitive reserve protect cognitive functioning. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 48(4), 23–30. doi:10.3928/02793695-20100302-01

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2001). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: ICF. Geneva: .WHO.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2017). Draft global action plan on the public health response to dementia. Geneva: .WHO.

- Zeilig, H. (2013). Dementia as a cultural metaphor. The Gerontologist, 54(2), 258–267. doi:10.1093/geront/gns203

- Zwijsen, S. A., Van der Ploeg, E., & Hertogh, C. M. (2016). Understanding the world of dementia. How do people with dementia experience the world? International Psychogeriatrics, 28(7), 1067–1107. doi:10.1017/S1041610216000351