Abstract

Objectives

To explore barriers in access to dementia care in Turkish, Pakistani and Arabic speaking minority ethnic groups in Denmark.

Method

Semi-structured qualitative individual- and group interviews with minority ethnic family carers, primary care dementia coordinators, staff in elderly daycare, and multicultural link workers. Hermeneutic phenomenology was used as theoretical framework.

Results

A total of 21 individual- and 6 group interviews were conducted, including a total of 35 participants. On the service user side, barriers in access to dementia care were related to lacking language proficiency and strong cultural norms, including familial responsibility for the care of older family members and stigma associated with mental illness and dementia. On the care provider side, the available formal services were rarely tailored to the specific needs of minority ethnic service users and were often considered inadequate or unacceptable.

Conclusion

Care practices and perceived consequences of dementia in minority ethnic communities were heavily influenced by cultural factors leading to a number of persisting barriers to accessing dementia care services. There is a simultaneous need to raise awareness about dementia and the existence of dementia care services in minority ethnic groups, to reduce stigma, and to develop culturally appropriate dementia care options.

Introduction

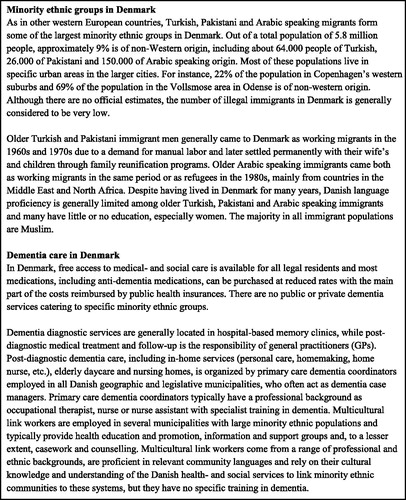

As in other European countries, in Denmark most people with minority ethnic backgrounds are immigrants or first-degree descendants of immigrants from non-western countries (Nielsen et al., Citation2015). Although minority ethnic populations are generally younger than the majority population, immigrants who came to Denmark as working migrants in the 1960s and 1970s are now ageing (see ). Due to differences in demographic aging, the estimated number of minority ethnic people with dementia is predicted to increase six to sevenfold between 2013 and 2040; from approximately 1200 to 7300 people, compared to a predicted two-fold increase in the number of people with dementia in the general population (Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI), Citation2015; Nielsen et al., Citation2015). This is similar to the trends seen in other European countries, including the United Kingdom (All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Dementia, Citation2013). Despite the need for dementia care in minority ethnic communities, previous studies in Nordic countries have found the diagnostic rate in older minority ethnic populations to be lower than in the majority population (Diaz, Kumar, & Engedal, Citation2015; Nielsen, Vogel, Phung, Gade, & Waldemar, Citation2011), and that minority ethnic populations have a lower uptake of post-diagnostic support and care (Nielsen, Nielsen, & Waldemar, Citation2019). Thus, in 2012 just 388 older people from minority ethnic groups were registered with a formal dementia diagnosis in the Danish health registries (corresponding to 1% of all registered cases) and of these, 109 resided in a nursing home (corresponding to 0.6% of all nursing home residents) (Stevnsborg, Jensen-Dahm, Nielsen, Gasse, & Waldemar, Citation2016).

Access to care can be defined as ‘the possibility of care users to identify healthcare needs, to seek healthcare services, to reach the healthcare resources, and to obtain or use healthcare services, and to actually be offered services appropriate to the needs for care’ (Levesque, Harris, & Russell, Citation2013). The barriers in access to dementia care in minority ethnic groups are complex and have not been well studied in Nordic countries but has been suggested to include language barriers, different help-seeking patterns, poor knowledge and misconceptions about dementia, in addition to different cultural views on caregiving (Daker-White, Beattie, Gilliard, & Means, Citation2002; Nielsen et al., Citation2015, Citation2019; Nielsen & Waldemar, Citation2016). In Denmark, people from minority ethnic groups with a diagnosis of dementia are 30% less likely to be prescribed anti-dementia medication and 48% less likely to enter a nursing home (Stevnsborg et al., Citation2016). These differences in dementia care patterns are worrying as they may result in poorer dementia outcome and care for people from minority ethnic groups.

To develop dementia care services that are inclusive of minority ethnic groups, it is important to examine barriers to accessing available services. Ethnic inequalities in dementia treatment and care, and the possible reasons for these inequalities have previously been explored in three comprehensive systematic reviews (Cooper, Tandy, Balamurali, & Livingston, Citation2010; Kenning, Daker-White, Blakemore, Panagioti, & Waheed, Citation2017; Mukadam, Cooper, & Livingston, Citation2011). However, these reviews included only studies from English-speaking countries that have minority ethnic populations and dementia care systems that differ from the ones in other countries (see for a description of dementia care in Denmark). An important difference between the Danish dementia care system and those of English-speaking countries such as the United Kingdom, the United States of America and Australia, is the responsibilities falling to family carers and the extent of involvement of formal services. Although family carers are the main providers of care across all countries, formal services play a considerable larger role in dementia care in Denmark. This is reflected in the availability and accessibility of public care services and the percentwise national expenditure on long-term care, which is about twice as large in Denmark (Knapp, Comas-Herrera, Somani, & Bannerjee, Citation2007). Thus, in Denmark 9.1% of the older population is living in nursing homes and residential care homes and 25.0% receive home care. In comparison, these numbers are 5.7% and 14.7% for Australia, 5.5% and 6.1% for England, and 4.2% and 8.7% for the Unites States of America (Knapp et al., Citation2007).

The aim of this study was to explore barriers in access to dementia care in Turkish, Pakistani and Arabic speaking minority ethnic groups in Denmark from the perspective of family carers, primary care dementia coordinators, staff in elderly daycare, and multicultural link workers in order to inform development of tailored interventions to encourage timely diagnosis and utilization of post-diagnostic dementia care.

Method

Design

Hermeneutic phenomenology (Kvale, Citation1983) was used as theoretical framework and semi-structured interviews were conducted by two experienced researchers (TRN, a certified psychologist and PhD; DN, a registered nurse and PhD). The meaning of the phenomenon was explored by being open to what was experienced, perceived and reported by the participants themselves. Then these reports were interpreted and further explored with the participants based on the researchers’ preunderstandings. This contributed to a manifold and in-depth description of the explored phenomenon along with different perspectives that might be relevant to the underlying construction of data. From a hermeneutical approach, the process of interpretation of different meanings is endless, but in practice stops when the meaning of the participant is constant and reasonable (Kvale, Citation1983).

All interviews were conducted between February and September 2018 at a location chosen by the participant(s) and lasted between 28 and 73 min. Individual interviews and group interviews comprising two or three participants with shared background, e.g. from the same family or working in the same elderly daycare center, were conducted to explore barriers in access to dementia care in minority ethnic groups. This approach was chosen to enhance data richness and contribute to the credibility of the findings (Lambert & Loiselle, Citation2008). Through the combination of data collection methods, complementary aspects of the same phenomenon were explored by approaching topics in depth through individual interviews and by inspiring new associations and perspectives through group discussions. The whole process followed the guidelines of COREQ (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, Citation2007)

Participants

Primary care dementia coordinators, staff in elderly daycare and multicultural link workers were purposively recruited from urban areas with large minority ethnic populations in Odense and Copenhagen and then by snowballing from those contacts. Minority ethnic family carers were recruited from the professional contacts of dementia coordinators to secure they had personal experience with dementia care services. Inclusion criteria for family carers were: having personal experience with providing care for a family member with dementia; and being of Turkish, Pakistani or Arabic speaking origin. Inclusion criteria for dementia coordinators and staff in elderly daycare were: having professional experience with minority ethnic older people with dementia. Inclusion criteria for multicultural link workers were: having professional or personal experience with minority ethnic older people with dementia; and being of Turkish, Pakistani or Arabic speaking background. Turkish, Pakistani and Arabic speaking was defined as being anyone who identified themselves as having Turkish, Pakistani or Arabic identity or heritage by links to Turkey, Pakistan or any Arabic speaking country. Experience was defined as any form of current or previous engagement in supporting or caring for minority ethnic older people. Dementia could be of any subtype.

Demographic information was collected for all participants. Although speaking Danish was not an inclusion criterion, all family carers and multicultural link workers were able to participate in Danish. Saturation was monitored continuously throughout data collection. Recruitment continued until saturation was reached and no new themes emerged from the data. All carers provided care for a family member with progressed dementia. Consequently, communicative challenges due to the severity of cognitive impairment and other dementia related challenges did not allow us to include the perspectives of people with dementia in the current study.

Data analysis

All interviews were recorded with a digital audio recorder and transcribed verbatim. First, the transcripts were read several times. Then thematic analysis was conducted (Kvale, Citation1983), in which responses to the interview questions along with other themes that emerged at this level were coded and compared across participant categories and ethnic groups. Finally, a strategy of mapping and interpretation was undertaken. Initial coding was undertaken by TRN and researcher triangulation employed via code and interpretation cross-checking by other members of the research group (DN and GW). The trustworthiness and credibility of the data analysis was further supported by triangulation of sources (multiple participant categories) and methods (individual- and group interviews), as described in the previous sections. Data was stored and organized using NVivo software (QSR International Pty Ltd, v.12, 2018).

Ethics

All participants provided written informed consent after reading a participation information sheet and having the opportunity to ask additional questions, following the principles of the European Framework for Research Ethics (European Commission, Citation2013). Participation was voluntary and without any financial incentive. The study was approved by the Danish Data Protection Agency (jnl no.: 2012-58-0004) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval by an official ethics committee was not required by Danish law.

Results

Participants and demographics

A total of 21 individual- and 6 group interviews were conducted, including a total of 35 participants. Of these, 31 (86%) were female. Demographic characteristics are presented in . Family carers had provided care for a family member with Alzheimer’s disease for 3 to 15 years; 2 were spouses, 9 children (or children-in-law) and 1 grandchild. Dementia coordinators and staff in elderly daycare had supported or cared for 2 to 10 minority ethnic older people with dementia within the last year, while multicultural link workers had experience with 1 to 20 through their professional and personal networks.

Table 1. Participants.

Themes

Emerging themes from the analysis were mapped and the following barriers were identified:

barriers to perceiving a need and desire for dementia care

barriers to seeking dementia care

barriers to reaching and engaging with dementia care

Barriers to perceiving a need and desire for dementia care

Families lacking awareness and knowledge

A recurring theme in most interviews was that lacking knowledge about dementia in minority ethnic communities posed a significant barrier for recognizing cognitive symptoms and perceiving a need for dementia care. Minority ethnic participants explained that dementia was generally something that was not talked about, partly due to a widespread belief that memory problems are a normal part of old age, and partly due to stigmatizing beliefs about mental illness and dementia resulting in it being a taboo condition:

Well, our experience is that when you get old, […] you lose your memory. Then you stay at home and it is the others (the family) who manage the chores […] There is a lot of taboo about it (dementia) and lacking knowledge as well (30-39yo Arabic speaking male family carer)

However, several participants also mentioned that things seem to be changing as awareness about dementia is slowly increasing among older people, who have acquired knowledge about dementia from TV programs from the country of origin, from friends and relatives having a family member diagnosed with dementia, and from children or grandchildren who have grown up in Denmark.

Family structure and care practices

Both Minority ethnic participants and dementia coordinators experienced that dominant cultural values of intergenerational reciprocity and care for older family members meant that milder cognitive and functional impairment would often go unnoticed or be regarded as unproblematic:

…this issue about you forgetting things and not really being able to keep track of things just becomes a natural part of family life. People simply adjust to it as a natural consequence of old age […] Well, you simply get a helping hand from left and right because you have these family relations where there’s always someone around who can help you (30-39yo Pakistani female multicultural link worker)

Perceiving a need or desire for seeking dementia care usually did not happen until family carers were exhausted and distressed by progressing behavioral symptoms making the person with dementia hard to manage, interfered with family dynamics, or led to dangerous situations or socially inappropriate behavior.

Information about existence of services rarely reach minority ethnic groups

Several dementia coordinators and multicultural link workers mentioned that information about the existence of formal dementia care services rarely reached people from minority ethnic groups, mainly due to issues with Danish language proficiency and literacy, making it difficult for them to approach such services:

… they also don’t know that options for counselling and support are actually available but believe that it is something you need to handle yourself (50-59yo Danish female dementia coordinator)

It was generally agreed that culture sensitive outreach and information was needed to facilitate awareness about the existence of dementia care services, how to reach them, and their value for the person with dementia and the family carers. Two dementia coordinators explained that they had had good experiences with organizing and carrying out dementia information meetings in liaison with multicultural link workers and local leaders of religious communities or cultural associations, who hosted the meetings. Despite this, there were only few examples of such efforts, which was generally related to limited time- and financial resources.

Barriers to seeking dementia care

Lacking knowledge about dementia care options and rights

When a need and desire for dementia care was present, lacking knowledge about dementia care options posed an additional barrier for seeking care and navigating the health- and social care systems. Sometimes, this led to a different or unusual pathway to dementia care:

We didn’t know where to seek dementia care, who to talk to. So, we actually didn’t seek care. But my brother he called… or were in contact with the public pensions department. If they could help him. What he should do. Then he contacted the GP because they told him that, well, we are probably not… this is something your GP needs to take care of (50-59 yo Turkish female family carer)

Also, due to uncertainty about their rights and previous negative experiences with social care services, some family carers would be reluctant to seek formal dementia care out of fear this could lead to restrictions in individual choice and autonomy:

… some people are likely to fear that they will lose their parents… if someone in social care services realizes that they are unable to take care of their dad and mom… or if their dad and mom aren’t… and then they will be taken away from you even if you don’t want it (30-39yo Pakistani female multicultural link worker)

Cultural values and norms for care

A recurring theme across most interviews was a strong cultural norm for taking care of older family members in minority ethnic groups. This was generally considered to be a family obligation, especially for the younger generations. Failure or unwillingness to live up to this norm would generally be associated with shame:

It is a cultural view that we must take care of our parents. They have given us so much. We must pay them back. It makes them uncomfortable that people talk badly about us. “Look, she has many children, but they send her to a nursing home. They should take care of her themselves” (60-70yo Arabic speaking female multicultural link worker)

This often meant that dementia care services were not considered until the point when family carers hardly coped any more. However, several participants also mentioned that the traditional family care practices may be gradually changing due to changing family structures, more women taking up paid employment outside the home and different perspectives on care, especially amongst younger generations:

… I also had [my own] family to look after, I have a job, and I also have a husband from Pakistan […] And I had children to pick up from school or follow to sports, or something. So, it became kind of… it became problematic because it was perceived as if I… I had… well, put myself first (40-49 yo Pakistani female family carer)

Stigmatizing beliefs

Stigmatizing beliefs about dementia, particularly that dementia is a form of insanity, was another issue that prevented or delayed dementia care seeking. Due to the strong stigma, minority ethnic people with dementia and their family carers would often try to conceal the symptoms for as long as possible:

Some women conceal these things for their husband because they are afraid he will think they have become demented or crazy and he needs to marry someone else […] I also think that’s why you try to conceal it for as long as possible and… well, try to leave it at home (30-39yo Turkish female elderly daycare worker)

Another widespread belief in minority ethnic communities was that dementia is hereditary and linked to genes. Having a family member diagnosed with dementia could thus be perceived as an indication that ‘insanity is running in the family’, potentially affecting the community status and position of other family members as well as the marriage prospects of adult children or grandchildren in arranged marriages:

Yes, that’s why. When we ask these people, they will not admit having dementia because they don’t want it to harm the children in the family. That their grandmother has dementia […] They don’t want to know what dementia is, what support is available… they only consider how this could harm my family (30-39yo Arabic speaking female multicultural link worker)

Rather than seeking dementia care, several participants had examples of family carers keeping people with dementia in their homes and hiding them away when cognitive or behavioral symptoms became apparent.

A recurring theme across all interviews was a strong taboo associated with moving a family member to a nursing home, which would be considered culturally unacceptable to many family carers. Although dementia coordinators were generally impressed by the extent of care provided by family carers, they also stated professional concerns about family carers with little understanding of dementia managing dementia related behaviors and coping with caregiver burden. Especially concerning were issues of neglect and abuse:

It’s also ignorance. […] And then they saw that he had tied her to the bed. To the bed rails. […] but when I asked openly, then (the son answered) … well, but it’s because of this issue with stools, and my wife has so much laundry already and we did not know what to do… it’s powerlessness (50-59yo Danish female dementia coordinator)

When formal dementia care services were unable or unwilling to meet the needs and expectations of people from minority ethnic groups, this could lead to mistrust, frustration and resignation, and sometimes a decision to not access available services.

Barriers to reaching and engaging with dementia care

Family dependence

Another issue that posed a barrier for reaching dementia care was the fact that minority ethnic older people were often dependent on other family members to establish contact to and communicate with dementia care services, typically their adult children:

Yes, well, language would probably be…well, it’s obvious that they can only go if someone from the family takes them. Would the person want to take them? Is it someone who should hear about these issues that may be intimate and exposing? When does the person have time to take them? Well, these are some of the issues I could think of. Also, there needs to be someone calling for them to make the appointment (40-49yo Turkish female multicultural link worker)

Also, hierarchical and gendered family roles and positions sometimes meant that decisions about dementia care rested with family members who differed from the ones providing the actual care:

In this family, all arrangements must be cleared with the son. In this way it’s the son who makes the decisions […] even though it’s the daughters who… one of them is employed there [as a paid family carer], so it’s her who knows everything (50-59yo Danish female dementia coordinator)

Often, seeking dementia care would be based on a family decision, taking into consideration the needs, wishes and interests of both the person with dementia, the family carers, and the immediate- and extended family, sometimes including family in the country of origin as well.

Lacking language proficiency

Minority ethnic older people were generally unable to engage with dementia care providers during the care process, mainly due to a language barrier, and often family carers were dissatisfied with the outcome of dementia care provided by Danish speaking care professionals. This sometimes led to a decision to discontinue utilizing services:

Her mother moved to a nursing home and this led to many challenges for them, mainly because she did not know the language. Also, they do not have the food she likes, and all the other people in the nursing home were Danish. She has become even more lonely there. And has become very closed (40-49yo Turkish female elderly daycare worker)

… and then there has been a healthy wife who did not speak Danish and she has had to try to explain to the home carer… and the home carer has tried to explain to the wife, and it gets… well, it’s kind of too much trouble … and then the family rather manages on their own (40-49yo Danish female dementia coordinator)

Many family carers preferred having care providers who spoke their language. However, having a language matched care provider is not a standard service delivered by dementia care services in Denmark. Also, some family carers cautioned that efforts to provide language matched care providers should always come second to professional and personal qualifications.

A professional lack of cultural sensitivity

To date, there are no dementia care services tailored to specific minority ethnic groups in Denmark and most participants felt that mainstream care services were generally not sensitive to the specific needs and expectations of minority ethnic groups:

There are many who ask why they are not getting the services they need […] First, they want someone speaking their own language to enable them to communicate with each other, and secondly, if women are expected to be washed by a man, this would not at all be acceptable (30-39yo Turkish female elderly daycare worker)

In nursing homes and elderly daycare centers, the content of activities, for example, foods and drinks, songs and music, television and traditional Danish pastimes, and the norms for social interaction, for example, between genders, would often be unfamiliar or inappropriate to minority ethnic older people. Some dementia coordinators and staff in elderly daycare stated that although care workers representing the main minority ethnic groups are well represented in nursing homes and home care services, service providers were not always prepared to match these to the ethnic background of service users.

Culturally inadequate care options

Some minority ethnic participants expressed the view that health- and social care was very good in Denmark. However, at the same time most participants felt that minority ethnic people were not able to benefit from this as they generally only had the opportunity to utilize dementia care services that did not fit their cultural and language needs. Participants generally considered available services to be inadequate in terms of both the dementia care options available and the way in which services were provided. Instead, many preferred options that would support them in providing dementia care at home:

I am not sure that a nursing home for people originating from Pakistan is something that is wanted […] What is wanted may rather be the opportunity to employ someone at home, or receive home care by someone, who speaks the language and have better time (50-59yo Danish female dementia coordinator)

However, in Denmark being economically compensated for the time spent on caregiving as a family carer is not part of standard dementia care options and decisions to accommodate this preference depended on the flexibility and goodwill of individual dementia care providers.

Discussion

This study explored barriers in access to dementia care in Turkish, Pakistani and Arabic speaking minority ethnic groups from the perspective of family carers, dementia coordinators, staff in elderly daycare and multicultural link workers. Overall, our findings replicate findings from studies in English-speaking countries within a Danish context. This suggests that identified barriers may be generalized across these countries and dementia care systems. Some of the identified barriers, including lack of knowledge regarding available services, misconceptions and stigma related to dementia, lack of services that focus on social needs and a complex healthcare system that is difficult to navigate do not seem to be specific to minority ethnic communities, but rather reflect more general barriers in access to formal dementia care in European countries (Stephan et al., Citation2018). However, our findings are generally in line with a recent meta-synthesis of qualitative studies (Kenning et al., Citation2017) as well as a recent survey among Danish dementia coordinators (Nielsen et al., Citation2019), indicating that these as well as other barriers are exaggerated by language and cultural issues.

The identified themes link to the conceptual framework of access to healthcare proposed by Levesque and coworkers (Levesque et al., Citation2013). A first barrier in access to dementia care happened when minority ethnic older people developed cognitive and functional impairment, but this was not perceived as a need for dementia care. There was often a particularly high threshold for identifying abnormality and perceiving a need and desire for dementia care in the minority ethnic groups. Lacking awareness and knowledge about dementia in many cases lead people to normalize symptoms of dementia as a natural part of old age. Also, cultural values and care practices meant that milder cognitive and functional impairment would often go unnoticed or be regarded as unproblematic as families would simply adjust to the changing circumstances as a natural part of family dynamics. These findings are similar to those of several other studies (Berdai Chaouni & De Donder, Citation2018; Kenning et al., Citation2017; Sagbakken, Spilker, & Nielsen, Citation2018; Vissenberg, Uysal, Goudsmit, van Campen, & Buurman-van Es, Citation2018). The fact that many people in minority ethnic groups were also unaware of the existence of dementia care services, how to reach them, and their usefulness, posed an additional barrier for perceiving a need and desire for approaching such services. As noted by others, this sometimes resulted in different or unusual pathways to care (Mukadam et al., Citation2011).

A second barrier in access to dementia care happened when minority ethnic older people or family carers perceived a need and desire for dementia care but did not have the capacity, accept or autonomy to choose to seek care. As reported in other studies, lacking knowledge about available dementia care options and personal rights, as well as previous negative experiences with health- and social services and an inability to successfully navigate these systems, with language barriers being reported as the main obstacle, often posed additional barriers for seeking formal care (Berdai Chaouni & De Donder, Citation2018; Mukadam et al., Citation2011; Parveen, Peltier, & Oyebode, Citation2017). Also, strong cultural norms for family care were seen to have a huge impact on care decisions and perceptions of dementia care options. Minority ethnic groups in the present study generally represented traditionally collectivist Islamic cultures characterized by strong values and norms for filial piety and pride in taking care of one’s own. Taking care of older family members was generally considered to be a family obligation, especially for the younger generations. As described in several other studies, failure or unwillingness to live up to the cultural norms for family care would generally be met with community disapproval and family shame (Berdai Chaouni & De Donder, Citation2018; Boughtwood et al., Citation2011; Naess & Moen, Citation2015; Parveen et al., Citation2017; Sagbakken, Spilker, & Ingebretsen, Citation2018; Sagbakken, Spilker, & Nielsen, Citation2018; van Wezel et al., Citation2016). Interestingly, although it was assumed by some dementia coordinators that minority ethnic families have large extended family networks that ‘look after their own’, some family carers reported that dementia was concealed from the wider family, and that the wider family networks were not supportive. Hierarchical and gendered family roles and positions sometimes meant that the final choice to seek dementia care rested with someone who differed from the ones providing the actual care, and it was noticed that these family members tended to focus more on the consequences of dementia for the family, such as family stigma and isolation, than for the person living with dementia. As described in other studies, concealment of the condition, or the person with dementia, was an evident result of the associated stigma (Berdai Chaouni & De Donder, Citation2018; Boughtwood et al., Citation2011; Mukadam et al., Citation2011; Mukadam, Waugh, Cooper, & Livingston, Citation2015; Parveen et al., Citation2017; Vissenberg et al., Citation2018).

A final barrier in access to dementia care was related to the fact that people from minority ethnic groups generally only had the opportunity to utilize dementia care services that did not fit their language and cultural needs. The general lack of choice faced by family carers and people with dementia when approaching service providers was seen to be a major barrier to utilizing dementia care services. Similar to the reports from studies in other European countries, mainstream services were generally perceived to lack cultural awareness and sensitivity for interacting with minority ethnic communities (Berdai Chaouni & De Donder, Citation2018; Naess & Moen, Citation2015; Parveen et al., Citation2017; Sagbakken, Spilker, & Ingebretsen, Citation2018; Vissenberg et al., Citation2018) and even when people from minority ethnic groups reached the point when a need and desire for dementia care was present, many would choose not to access available services. Families often preferred options that would allow them to provide family care for the person with dementia at home or having a home care provider who spoke their language. However, such options were generally not available. In a recent study (Nielsen, Waldemar, & Nielsen, Citation2020), we explored dementia care models adopted by minority ethnic families and found ‘rotational care’ to be a common alternative to formal care solutions; that is, the care responsibility was shared between several family members, who took turns to provide 24-h care for the person with dementia. On one hand, this allowed the person with dementia to stay in familiar caring contexts surrounded by people speaking the same language, while decreasing the burden of care of individual family carers. On the other hand, with advancing dementia and behavioral and psychological symptoms, rotational care could be confusing and stressful to the person with dementia and negatively affect the quality of life of all involved. Thus, higher reliance on shared family care should not be taken to indicate that minority ethnic families are not in need of support and guidance from formal dementia services.

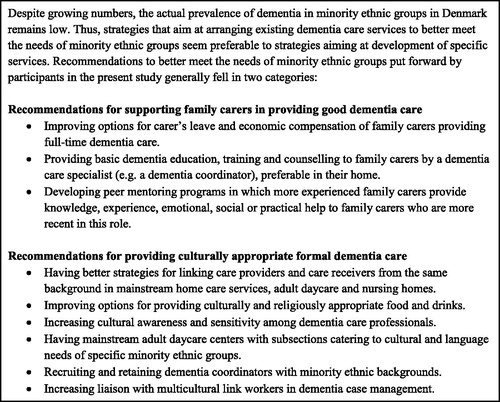

At the service user level, the study suggests that it is not enough to raise awareness about dementia in minority ethnic groups to reduce misconceptions and associated stigma. As many were not aware of the existence of dementia care services, it will also be important to promote knowledge about the existence of such services. It was generally agreed, that this required a more proactive effort from service providers to be effective. At the service provider level, it seems important to increase cultural competence and sensitivity in interacting with people from minority ethnic groups, for instance by using professional interpreters when needed, and negotiating culturally and professionally acceptable care solutions based on available resources. At the same time, the study suggests that there may be a general need to develop new resources in terms of culturally appropriate dementia care solutions. These should preferably include both options that support families in providing good care within the context of the family and formal care options that are culturally appropriate (see ).

Strengths of the study include the purposive inclusion of participants with personal experiences with dementia care in minority ethnic groups, the variation in participant characteristics, and the triangulation of sources and methods, which enabled in-depth examination of variations and contradictions, as well as consistency across different participant categories and data sources. Although the views expressed by participants in individual- and group interviews may have been affected by the different data collection methods, we found the combination of data collection methods revealed broader aspects of the explored phenomenon and contributed to a more comprehensive understanding (Lambert & Loiselle, Citation2008). We found, that the individual interviews exploring personal experiences and the group interviews examining opinions and beliefs about barriers to dementia care were complimentary and helped to provide a deeper understanding of the phenomenon. Also, overlap with previously identified barriers in access to dementia care in minority ethnic groups suggests transferability of the findings (Kenning et al., Citation2017; Nielsen et al., Citation2019). Limitations of the study include the fact that although we were able to get in-depth information from people with personal experience with dementia care in three minority ethnic groups in Denmark, this is not necessarily representative of other minority ethnic groups or even all people in those groups, particularly as most participants were females from two larger cities who all spoke Danish. Especially the Arabic speaking minority ethnic group is a large and heterogeneous group, but even in more homogeneous groups there will be differences among individuals. It is important to notice, that although the participants made several general observations, the attitudes, beliefs and behaviors of people were also perceived to vary within the minority ethnic groups. Apart from their cultural background, people in minority ethnic groups were perceived to be influenced by factors such as education, acculturation, family background, economic circumstances and migration experience. Finally, we did not include the perspectives of people with dementia which may differ from those of their family carers. Only very few studies have directly reported the perspectives of people with dementia, which may be because people from minority ethnic groups with dementia generally access services at a late stage where they may lack capacity to take part in research. However, a study that reported the views of south Asian people with dementia seem to corroborate the perspectives of family carers as they generally conceptualized their condition as a natural part of ageing and expressed confidence and pride in the presence of family support. This helped them cope with their condition and led to a perceived irrelevance of nursing homes. On the other hand, a distinctive level of distress was evident in the few who lacked confidence in family support (Lawrence, Samsi, Banerjee, Morgan, & Murray, Citation2011).

In conclusion, this study provides an account of barriers in access to dementia care in less researched minority ethnic groups in Denmark and suggests target areas for tailored interventions to improve timely diagnosis and utilization of post-diagnostic dementia care. Although perceptions of dementia may be gradually changing among minority ethnic communities, care practices and perceived consequences were heavily influenced by cultural factors leading to several persisting barriers to accessing dementia care services. The study suggests a simultaneous need to raise awareness about dementia and the existence of dementia care services in minority ethnic groups, to reduce stigma, and to develop culturally appropriate dementia care options.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- All Party Parliamentary Group (APPG) on Dementia. (2013). Dementia does not discriminate. The experience of black, Asian and minority ethnic communities. London: Alzheimer’s Society.

- Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI). (2015). World Alzheimer Report 2015: The Global Impact of Dementia. An analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International.

- Berdai Chaouni, S., & De Donder, L. (2018). Invisible realities: Caring for older Moroccan migrants with dementia in Belgium. Dementia (London, England), 18(7–8), 3113–3129. doi:10.1177/1471301218768923

- Boughtwood, D., Shanley, C., Adams, J., Santalucia, Y., Kyriazopoulos, H., Pond, D., & Rowland, J. (2011). Culturally and linguistically diverse (CALD) families dealing with dementia: An examination of the experiences and perceptions of multicultural community link workers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 26(4), 365–377. doi:10.1007/s10823-011-9155-9

- Cooper, C., Tandy, A. R., Balamurali, T. B., & Livingston, G. (2010). A systematic review and meta-analysis of ethnic differences in use of dementia treatment, care, and research. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 18(3), 193–203. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181bf9caf

- Daker-White, G., Beattie, A. M., Gilliard, J., & Means, R. (2002). Minority ethnic groups in dementia care: A review of service needs, service provision and models of good practice. Aging & Mental Health, 6(2), 101–108. doi:10.1080/13607860220126835

- Diaz, E., Kumar, B. N., & Engedal, K. (2015). Immigrant patients with dementia and memory impairment in primary health care in Norway: A national registry study. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 39(5-6), 321–331. doi:10.1159/000375526

- European Commission. (2013). Ethics for researchers. Facilitating Research Excellence in FP7. Luxembourg: European Commission

- Kenning, C., Daker-White, G., Blakemore, A., Panagioti, M., & Waheed, W. (2017). Barriers and facilitators in accessing dementia care by ethnic minority groups: A meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 316. doi:10.1186/s12888-017-1474-0

- Knapp, M., Comas-Herrera, A., Somani, A., & Bannerjee, S. (2007). Dementia: International comparisons. Summary report for the National Audit Office. London: Personal Social Services Research.

- Kvale, S. (1983). The qualitative research interview: A phenomenological and a hermeneutical mode of understanding. Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 14(1–2), 171–196. doi:10.1163/156916283X00090

- Lambert, S. D., & Loiselle, C. G. (2008). Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(2), 228–237. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04559.x

- Lawrence, V., Samsi, K., Banerjee, S., Morgan, C., & Murray, J. (2011). Threat to valued elements of life: The experience of dementia across three ethnic groups. The Gerontologist, 51(1), 39–50. doi:10.1093/geront/gnq073

- Levesque, J. F., Harris, M. F., & Russell, G. (2013). Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12, 18. doi:10.1186/1475-9276-12-18

- Mukadam, N., Cooper, C., & Livingston, G. (2011). A systematic review of ethnicity and pathways to care in dementia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(1), 12–20. doi:10.1002/gps.2484

- Mukadam, N., Waugh, A., Cooper, C., & Livingston, G. (2015). What would encourage help-seeking for memory problems among UK-based South Asians? A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 5(9), e007990. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007990

- Nielsen, T. R., Antelius, E., Spilker, R. S., Torkpoor, R., Toresson, H., Lindholm, C., & Plejert, C. (2015). Dementia care for people from ethnic minorities: A Nordic perspective. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(2), 217–218. doi:10.1002/gps.4206

- Nielsen, T. R., Nielsen, D. S., & Waldemar, G. (2019). Barriers to post-diagnostic care and support in minority ethnic communities: A survey of Danish primary care dementia coordinators. Dementia. doi:10.1177/1471301219853945

- Nielsen, T. R., Vogel, A., Phung, T. K., Gade, A., & Waldemar, G. (2011). Over- and under-diagnosis of dementia in ethnic minorities: A nationwide register-based study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(11), 1128–1135. doi:10.1002/gps.2650

- Nielsen, T. R., & Waldemar, G. (2016). Knowledge and perceptions of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in four ethnic groups in Copenhagen, Denmark. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(3), 222–230. doi:10.1002/gps.4314

- Nielsen, T. R., Waldemar, G., & Nielsen, D. S. (2020). Rotational care practices in minority ethnic families managing dementia: A qualitative study. Dementia. doi:10.1177/1471301220914751

- Naess, A., & Moen, B. (2015). Dementia and migration: Pakistani immigrants in the Norwegian welfare state. Ageing & Society, 35, 26.

- Parveen, S., Peltier, C., & Oyebode, J. R. (2017). Perceptions of dementia and use of services in minority ethnic communities: A scoping exercise. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(2), 734–742. doi:10.1111/hsc.12363

- Sagbakken, M., Spilker, R. S., & Ingebretsen, R. (2018). Dementia and migration: Family care patterns merging with public care services. Qualitative Health Research, 28(1), 16–29. doi:10.1177/1049732317730818

- Sagbakken, M., Spilker, R. S., & Nielsen, T. R. (2018). Dementia and immigrant groups: A qualitative study of challenges related to identifying, assessing, and diagnosing dementia. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 910. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3720-7

- Stephan, A., Bieber, A., Hopper, L., Joyce, R., Irving, K., Zanetti, O., … Actifcare Consortium. (2018). Barriers and facilitators to the access to and use of formal dementia care: Findings of a focus group study with people with dementia, informal carers and health and social care professionals in eight European countries. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 131. doi:10.1186/s12877-018-0816-1

- Stevnsborg, L., Jensen-Dahm, C., Nielsen, T. R., Gasse, C., & Waldemar, G. (2016). Inequalities in access to treatment and care for patients with dementia and immigrant background: A Danish nationwide study. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 54(2), 505–514. doi:10.3233/JAD-160124

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- van Wezel, N., Francke, A. L., Kayan-Acun, E., Ljm Deville, W., van Grondelle, N. J., & Blom, M. M. (2016). Family care for immigrants with dementia: The perspectives of female family carers living in The Netherlands. Dementia (London, England), 15(1), 69–84. doi:10.1177/1471301213517703

- Vissenberg, R., Uysal, O., Goudsmit, M., van Campen, J., & Buurman-van Es, B. (2018). Barriers in providing primary care for immigrant patients with dementia: GPs' perspectives. BJGP Open, 2(4). doi:10.3399/bjgpopen18X101610