Abstract

Background

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) has a profound impact on the spouse and other family caregivers involved. While caregivers have a need for support, it is difficult for healthcare providers to respond to their specific needs. This qualitative study explores the lived experiences and needs of caregivers of persons with FTD to facilitate the development of support.

Methods

Three focus group discussions were organized to explore the lived experiences of Dutch FTD caregivers. The included caregivers (n = 24) were aged 16 years or older and were involved in the care of a relative with FTD. Two researchers independently performed an inductive content analysis using open and axial coding.

Results

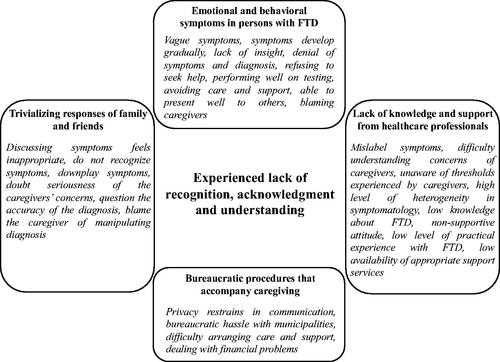

The main category emerging from the data was a lack of recognition, acknowledgment, and understanding experienced by caregivers. This was linked to caregivers’ experiences with (1) complex emotional and behavioral symptoms in the person with FTD, (2) the trivializing responses of family and friends, (3) a perceived lack of knowledge and support from healthcare professionals, and (4) the bureaucratic procedures that accompany caregiving. As a result, caregivers felt lonely and solely responsible for the caregiving role.

Conclusion

Caregivers of persons with FTD experience a lack of understanding in caring for their relative with FTD, which contributes to feelings of loneliness. A specialized support approach is needed to address the specific needs of caregivers of persons with FTD. Support should address strategies that caregivers can use to inform and involve family and friends in the caregiving situation to prevent loneliness in FTD caregivers.

Introduction

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) has a profound impact not only on the persons with FTD themselves but also on their spouses and other family caregivers involved (Kaizik et al., Citation2017; Nunnemann, Kurz, Leucht, & Diehl-Schmid, Citation2012). Diagnostic disclosure is important for caregivers as it helps them to understand and cope with symptoms in their relative with FTD (Caceres et al., Citation2016; Nunnemann et al., Citation2012). In retrospect, caregivers often describe the prediagnostic phase as a period full of uncertainty and frustration (Caceres et al., Citation2016; Nunnemann et al., Citation2012). This is probably attributed to the prolonged time to diagnosis, as it is difficult for caregivers and healthcare professionals to recognize FTD due to the insidious onset of symptoms at young age (van Vliet et al., Citation2013). It is challenging to recognize FTD due to its heterogeneous clinical presentation including symptoms such as disinhibition, apathy, compulsive behavior, loss of insight, loss of empathy, aphasia, impaired semantic knowledge, loss of speech production, agrammatism, and apraxia (Bang, Spina, & Miller, Citation2015; Hogan et al., Citation2016). Behavioral and personality change and a lack of disease insight in the person with FTD may especially delay help-seeking behavior, thereby further prolonging the diagnosis (Draper et al., Citation2016; Rosness, Haugen, Passant, & Engedal, Citation2008b; van Vliet et al., Citation2013).

Although caregivers often already perform caregiving tasks prior to diagnosis, diagnostic disclosure marks the start of the caregiving trajectory (de Vugt & Verhey, Citation2013; Ducharme, Lévesque, Lachance, Kergoat, & Coulombe, Citation2011). Especially in the behavioral variant of FTD, caregivers often experience the loss of an emotional connection with the person with FTD and feel forced to sacrifice parts of their social life to fulfil their caregiving role. As a result, caregivers can experience social isolation and feelings of loneliness (Caceres et al., Citation2016; Massimo, Evans, & Benner, Citation2013; Nunnemann et al., Citation2012). In particular, coping with behavioral changes in the person with FTD may impose high levels of burden and distress in FTD caregivers (Nunnemann et al., Citation2012).

While FTD caregivers express a high need for support after the diagnosis, it is difficult for healthcare providers to recognize and respond to their specific needs (Barca, Thorsen, Engedal, Haugen, & Johannessen, Citation2014; Caceres et al., Citation2016; Rosness, Haugen, & Engedal, Citation2008a). This may be related to the low prevalence and heterogeneous clinical presentation of FTD (Onyike & Diehl-Schmid, Citation2013). Caregivers of persons with the behavioral variant of FTD, for example, often have to cope with challenging behavior from their relative with FTD, such as social awkwardness, a loss of manners, and egoistic behavior (Gossink et al., Citation2018b; Ibañez & Manes, Citation2012; Mendez et al., Citation2014). Caregivers of persons with a language variant of FTD, either non-fluent primary progressive aphasia or semantic dementia, are confronted with a profound decline in the linguistic abilities of their relative, such as difficulties with language production or loss of word meaning (Bang et al., Citation2015). Both changes in behavior and difficulties with communicating are known to be challenging and burdensome for caregivers (Caceres et al., Citation2016; Diehl-Schmid et al., Citation2013). While the wide variety of symptoms poses unique challenges for caregivers, there seems to be a knowledge gap regarding effective support for caregivers of persons with FTD (Gossink et al., Citation2018a; Karnatz et al., Citation2019). Therefore, this study aims to explore the lived experiences and needs of spouses and other family caregivers of persons with FTD to facilitate the development of support strategies and interventions.

Methods

In this qualitative study, focus group discussions were organized to explore lived experiences and needs of spouses and other family caregivers of persons with FTD in the Netherlands. The results are reported using the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) (Tong, Sainsbury, & Craig, Citation2007).

Recruitment and participants

In spring 2019, participants were recruited by (1) distributing information leaflets in waiting rooms in the memory clinic of the Maastricht University Medical Centre (MUMC+), (2) addressing the focus groups during bimonthly meetings with healthcare organizations affiliated with Dutch Young-onset Dementia Knowledge Center [Kenniscentrum Dementie op Jonge Leeftijd], and (3) providing information via peer-support meetings, social media and the website of the Dutch FTD peer-support organization [FTD lotgenoten]. An ambassador of the Dutch FTD peer-support organization also actively informed caregivers about the study.

All potential participants registered via email and were then informed about the study objectives in a telephone conversation. To obtain a comprehensive understanding on how caregivers perceived caring for a relative with FTD throughout the caregiving trajectory we used purposeful sampling to include participants that varied in their level of experience, their relationship to the person with FTD (spouses, children, and other relatives), FTD subtype (behavioral and language variants), and gender. This allowed us to gain insight into experiences from caregivers in different stages of the caregiving trajectory. The focus group discussions were conducted with caregivers from two urban areas and one rural area in the Netherlands.

Caregivers were eligible for participation if they were involved in the care of their spouse, parent, or other relative with either the behavioral or a language variant of FTD. In accordance with guidelines of the medical ethical committee, caregivers younger than 16 years were excluded from participation.

All eligible participants received written information about the study by post before inclusion and were phoned to check whether they had additional questions. All participants provided informed consent before participating in the focus group discussions.

Procedures and data collection

A context mapping approach with generative techniques was used to sensitize caregivers prior to the focus groups to obtain insight into their lived experiences and to initiate discussion during the focus groups (Visser, Stappers, van der Lugt, & Sanders, Citation2005). In line with grounded-theory multiple techniques were used to collect data (Charmaz, Citation2014; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967). For example, prior to their participation, caregivers completed a booklet containing questions about their everyday life such as ‘What is important for you when caring for your relative with FTD?’ and ‘What gives you positive energy in your daily life?’ In addition, caregivers reflected on their experiences by writing a letter containing advice on caregiving to peers (Boots, Wolfs, Verhey, Kemplen, & de Vugt, Citation2015).

Each focus group discussion was moderated by a (neuro)psychologist (MdV/CB) with clinical and research expertise regarding FTD and with experience in moderating focus group discussions. During each focus group, the process was monitored and field notes were made by the first author (JB), who has a background in nursing, psychology and health sciences. In addition, two assistants with a background in nursing or health sciences made fieldnotes as well.

To guide the focus group discussions, a topic list was developed based on the literature, qualitative interviews from the NEEDs in Young-onset Dementia study (NeedYD) (van Vliet et al., Citation2010), and expert discussions. The topic list covered (1) the prediagnostic period, (2) the postdiagnostic period, and (3) caregiver coping strategies. After each focus group discussion, a consensus meeting was organized with the research team to evaluate the data collection process and refine the topic list if needed. Each focus group discussion was video recorded to gain insights into the interactions between participants. All focus groups were transcribed verbatim using F5 transcript software.

Data analysis

To derive categories from the data, two researchers (JB/KP) independently performed an inductive content analysis by openly coding the data in Atlas.ti version 8.3.1 (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008; Evers, Citation2015; Savin-Baden & Major, Citation2013). They compared texts that were assigned to codes by constant comparison to reach consensus on the code definitions and code structure (Bradley, Curry, & Devers, Citation2007). Then, related codes within the code structure were merged using axial coding and both researchers independently developed a mind-map to elicit categories and subcategories from the codes. In line with grounded theory an iterative process was used to interpret the findings and derive theory from the data using selective coding (Charmaz, Citation2014). First, the main category and subcategories were derived by combining the mind-maps through discussion with the last author (MdV). Next, the main category and subcategories were discussed with the wider research team to deepen the findings. Then, the results were verified by discussing the findings with the chairman of the Dutch FTD peer-support organization. Throughout the process, the first and second authors continuously checked whether new information emerged from the data to establish data saturation (Patton, Citation2002).

Trustworthiness of data

To ensure the trustworthiness of the data, multiple techniques to achieve method and data source triangulation were used, such as the use of fieldnotes, video recordings of the group discussions, and the use of the booklet containing questions about everyday life (Creswell, Citation2013). During meetings, researchers with different backgrounds reflected on the general research process, the data collection, and the results during team meetings to ensure investigator triangulation (Carter, Bryant-Lukosius, DiCenso, Blythe, & Neville, Citation2014).

Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of Maastricht University (#2018-0675).

Results

A total of 48 FTD caregivers registered for participation. Using purposeful sampling, 24 caregivers were invited for three focus group discussions (). Eight caregivers were included in the first focus group in a rural area in the Netherlands. Subsequently, two additional focus group discussions, each with eight participants, were organized in urban areas. The remaining 24 caregivers were added to a waiting list for an additional fourth focus group. Data saturation was established after the third focus group discussion as no new information emerged. Therefore, no fourth focus group discussion was organized. All focus groups were organized in the evenings or on weekends to facilitate the participation of caregivers who were working or studying. The focus groups lasted between 2 h and 2.5 h and were held in meeting rooms of one hospital and two healthcare organizations.

Table 1. Characteristics of the family members (n = 24) of persons with FTD (n = 20).

Participants

In the three focus groups, 17 females and seven males between the ages of 31 and 79 participated. The majority of the participants were spouses. Other family caregivers, such as children, and siblings of the person with FTD, also participated. As some were part of the same family, the 24 included caregivers were involved in the care for 20 persons with FTD; 15 with the behavioral variant and five with a language variant of FTD. On average, the first symptoms in the persons with FTD started about 9 years before the focus group discussion (range between 4 and 12 years), and the diagnosis was on average established 4 years ago (range 0.5–9 years).

Main category: the experienced lack of recognition, acknowledgment, and understanding throughout the caregiving trajectory

After an iterative open and axial coding process, consensus was reached about the used codes and their definitions. Using selective coding iteratively theory was derived from the data by yielding one main category from the data and four subcategories (). The data revealed that throughout the caregiving trajectory, caregivers perceived a lack of recognition, acknowledgment, and understanding not only from the person with FTD but also from family, friends, and healthcare professionals. Caregivers, for example, experienced that FTD symptoms often did not fit within the image that people have of dementia making it difficult for family, friends, and healthcare professionals to recognize symptoms of FTD. In turn, caregivers perceived a lack of understanding and felt not acknowledged in their caregiving role. This made caregivers feel solely responsible for the caregiving role and this induced feelings of loneliness. According to caregivers, this made caring for a relative with FTD particularly exhausting and stressful.

People simply do not understand the impact of FTD on the caregivers involved. This is very difficult to cope with.– son-in-law, behavioral variant, FG3

It is a very lonely process. I have a lot of people around me, but you can’t really share it. – spouse, behavioral variant, FG3

Although caregivers stressed that there were profound differences between the behavioral and language variants of FTD, a common perception among caregivers was that they perceived a lack of recognition, acknowledgment, and understanding. This was linked to four subcategories related to caregivers’ experiences with (1) complex emotional and behavioral symptoms in the person with FTD, (2) the trivializing responses of family and friends, (3) a perceived lack of knowledge and support from healthcare professionals, and (4) the bureaucratic procedures that accompanied the caregiving role. The extent to which these subcategories influenced the experienced lack of recognition, acknowledgment and understanding varied during the three phases of the caregiving trajectory namely, recognizing early symptoms of FTD, during the diagnostic process, and while gaining access to social and professional support.

Caregivers’ experiences with the recognition of the early symptoms of FTD

In the first phase of the caregiver trajectory, caregivers experienced egoistic, paranoid, jealous, impulsive, stereotypic, and apathetic behavior as early symptoms in their relative with FTD. Caregivers of persons with a language variant of FTD described apathy, a loss of semantic knowledge, mutism, and difficulty speaking fluently. This made caregivers feel that their relationship with the person with FTD deteriorated because there was less reciprocity and interaction.

Most caregivers experienced difficulties with recognizing and understanding these symptoms as they developed gradually over time. According to caregivers of persons with the behavioral variant, recognizing early symptoms was complicated due to a lack of disease insight in the person with FTD, who often denied that something was wrong. This made caregivers feel insecure about the seriousness of the symptoms and sometimes caregivers felt that they themselves were to blame for the emotional and behavioral changes in their relative with FTD.

The behavioral change was going on for years. You have no idea what is going on. You think you are the one to blame. – spouse, behavioral variant, FG1

Caregivers also expressed that it was difficult to discuss their concerns about early symptoms with their family and friends. They suggested this might be due to feelings of guilt and shame, as they perceived it as complaining or bad-mouthing their relative with FTD.

My father lost the ability to speak. […] In our cultural community, they thought he did something bad. They thought the symptoms were supernatural or that it was voodoo. This was very stressful for our family. So, you simply do not talk about it. Perhaps, this is due to shame. – daughter, language variant, FG1

I always felt that something was wrong. (…) I was worried, but I could not go anywhere with my worries. – spouse, behavioral variant, FG3

In addition, trivializing responses from family and friends downplaying the severity of the caregivers’ concerns made caregivers feel as if they had overreacted to the situation. This made caregivers doubt the seriousness of their concerns.

When people came to visit us, they said “He seems to be doing very well”. This made me doubt. – spouse, behavioral variant, FG2

Caregivers perceived that it was difficult to discuss their concerns with family and friends who often did not recognize symptoms in the person with FTD, such as apathy, agitation, or compulsive behavior. As a result, caregivers missed social support and this made them feel unrecognized in coping with early symptoms. As a result, many caregivers expressed to feel lonely.

Caregivers also experienced that early symptoms of FTD being regularly mislabeled as work-related distress or marital problems by employers and occupational physicians. Looking back, caregivers perceived a lack of knowledge in healthcare professionals regarding FTD and felt this had contributed to a delayed diagnosis. In addition, caregivers felt frustrated by privacy restraints that hindered communication with the employer and occupational physician of their relative with FTD.

When I asked the occupational physician what was going on, he said, ‘Privacy. I can only tell you that stress does strange things to people’. – spouse, behavioral variant, FG2

Caregivers perceived that the unwillingness of the occupational physician to disclose any information about problems at work felt as an unnecessary bureaucratic barrier, and it significantly delayed the start of the diagnostic process and therefore obstructed gaining access to professional help and support.

Caregivers’ experiences with the diagnostic process and diagnostic disclosure

In the diagnostic process, caregivers perceived several barriers that delayed help seeking. Caregivers explained they postponed visiting the general practitioner (GP), as the person with FTD denied symptoms and refused to go to the GP. Some caregivers visited the GP alone, while others eventually succeeded in persuading the person with FTD to visit the GP by, for example, asking their children to accompany the person with FTD. Caregivers also postponed visiting the GP because of the trivializing responses of family and friends who often doubted the seriousness of symptoms. However, some caregivers indicated that on some occasion’s family or friends also noticed early symptoms and motivated them to reach out for professional help.

Everybody in our environment had an opinion about what is going on. (…) This is why you do not discuss the situation. – daughter, language variant, FG1

My daughter took a year off to travel. When she came home, she felt like, “What happened here?” This is why we visited the general practitioner’. – spouse, behavioral variant, FG3

According to caregivers, GPs often had difficulty understanding the caregivers’ concerns because the persons with FTD often presented themselves well to GPs and performed well on neuropsychological testing. Caregivers acknowledged that it was difficult for GPs to recognize FTD because symptoms are difficult to interpret and developed gradually over time. They also felt that early recognition was complicated by work-related stress, marital problems or comorbid disease, such as a neurological pain disorder, low-back, problems, or multiple sclerosis. Additionally, caregivers felt that GPs were often unaware of the threshold perceived by caregivers in talking openly about emotional and behavioral changes in their relative with FTD, especially when caregivers and persons with FTD both consulted the GP. Some GPs, for example, confronted the person with FTD with the caregivers’ concerns during a consult, which made caregivers feel misunderstood and unsupported. Caregivers also felt that GPs should have had more knowledge about the early symptoms of FTD, as this would have fostered the early recognition of symptoms.

It feels bad to talk about your spouse like this with the GP. Especially when he kept asking my husband, ‘How do you feel if she [caregiver] says all these things about you?’ – spouse, behavioral variant, FG3

Looking back at the diagnostic process, some caregivers also expressed highly positive experiences with regard to the role of their GP. Some caregivers, for example, felt that the GP took their concerns seriously, acted very supportively and seemed highly motivated to determine what was going on. This made caregivers feel heard and recognized.

Our GP was very supportive from the beginning but lacked knowledge about FTD. GPs should have more knowledge about the early symptoms, but this is difficult because GPs already need to know so much. – spouse, language variant, FG2

According to caregivers, the FTD diagnosis helped them to better understand the emotional and behavioral changes in their relative with FTD. Diagnostic disclosure led to a sense of recognition among caregivers. Some felt relieved that pieces of the puzzle had finally fallen into place. Receiving the diagnosis also helped caregivers address and explain the situation to family and friends.

I thought ‘If this continues, then I will quit’. In that sense, the diagnosis was a blessing. You finally get it and think, ‘Okay, for better and for worse’. This is why I continue. – spouse, behavioral variant, FG2

The diagnosis enabled me to tell my children why their father acted like this. That it was his illness and not because he did not love them anymore. – spouse, behavioral variant, FG2

Some caregivers explained that family members said they had doubts about whether the diagnosis was correct. Some caregivers of persons with the behavioral variant of FTD, explained that family sometimes accused them of manipulating the diagnosis. As a result of these trivializing responses, caregivers felt sad and abandoned by family and friends. This made caregivers feel solely responsible for the caregiving role.

My family and my sisters think that I manipulated the diagnosis. They think that there is nothing going on with my husband. They even said that I should see a doctor. This makes me really sad. – spouse, behavioral variant, FG3

You have to cope with all of this by yourself. You need to find some kind of best practice for all the shit you go through. – spouse, behavioral variant, FG2

Caregivers’ experiences with gaining access to social and professional support

Caregivers stated that emotional, behavioral, and language symptoms progressed in the phase after the diagnosis. As a result, caregivers felt that they were losing the emotional connection with their relative. For example, due to increasing levels of apathy and a lack of empathy. Caregivers perceived the diagnostic process as an emotional burden and experienced feelings of sadness and grief as they felt they were gradually losing their relative with FTD.

He is still here, but he no longer behaves as my husband. Losing your spouse really hurts. – spouse, behavioral variant, FG2

Caregivers explained this was frustrating for them to cope with the lack of awareness of the disease in their relative with FTD, who in turn, devalued, neglected and underestimated the impact of their caregiving role. As a result, they felt unrecognized as caregivers. Most caregivers acknowledged that social support helped them to cope with stress and recharge their battery, but it was difficult to gain sufficient support from family and friends after diagnosis. Involving family and friends in the caregiving situation was experienced as exhausting as they were often unable to recognize symptoms and acknowledge the caregivers’ needs, despite the diagnosis.

When people say, ‘He visited us but we did not notice anything’. I always think, ‘What are you trying to say? That I am crazy?’ – spouse, behavioral variant, FG3

Sometimes I feel completely upset. Then, my children tell me, ‘It is not that bad.’ (…) They simply do not understand. This is why being a caregiver is lonely. – spouse, behavioral variant, FG3

Caregivers perceived this as a lack of understanding from family and friends. This made caregivers feel unsupported and lonely. In turn, caregivers felt it was very difficult to achieve a sense of balance in their life and learn to adjust to combining caregiving with having a life of their own.

I was very tired and stressed when my husband still lived at home. […] I learned that it is very important to find a balance and think about yourself. – spouse, behavioral variant, FG2

Caregivers often experienced that it was difficult for GPs, psychologists, and specialized dementia nurses to provide practical advice about coping with emotional and behavioral change in the person with FTD. As a result, caregivers felt unrecognized and misunderstood by healthcare providers and postponed the use of care and support services. Due to the lack of appropriate support services for FTD caregivers, they stressed the importance of peer-support groups to elicit a sense of recognition and understanding. During the focus groups, some caregivers expressed that they only needed half a word to understand other FTD caregivers. When it came to professional support and peer-support, child caregivers expressed feeling left in the dark.

As a daughter, there was no support for me at all. I visited a peer-support group once, but everyone there was a spouse. I was hard for me to connect with them. – daughter, language variant, FG1

Caregivers also expressed frustration with the bureaucratic procedures that accompanied the caregiving role, such as struggles with the municipality to receive the postal mail, and applying for personal care funding. Some caregivers explained that they had lost their specialized dementia nurse and peer-support group because their relative with FTD became institutionalized. Caregivers explained it was frustrating to feel unsupported, neglected, and misunderstood by healthcare providers.

I do not understand why I am not allowed to visit peer-support meetings anymore now that my husband is hospitalized. All of a sudden, your support is gone. – spouse, language variant, FG1

Some caregivers of persons with the behavioral variant also explained that they ended up with serious financial problems as a result of their relative having FTD. After the diagnosis, some caregivers found that the person with FTD was gambling, made risky investments or had refused to pay the bills. Coping with financial difficulties was often frustrating for caregivers, and arranging financial custody could only be achieved by following lengthy procedures. This generally resulted in increased financial debts.

My parents are in deep financial debt and may lose their house. We are unable to put my dad [the person with FTD] under financial supervision due to the paperwork. The process is really frustrating. – daughter, behavioral variant, FG3

At the same time, caregivers experienced little compassion from financial institutions such as banks and debt collectors, who often did not understand the impact of FTD. As a result, caregivers felt unacknowledged and misunderstood.

The frustrating part is that no one has any understanding. If he [the person with FTD] would stab and kill someone, they would probably declare him unaccountable. With regard to financial debts, they do not. You are all alone with those debt collectors breathing down your neck. – son-in-law, behavioral variant, FG1

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that FTD caregivers experience a lack of recognition, acknowledgment and understanding while caring for their relative with FTD. According to caregivers, FTD symptoms often do not fit within the image people have of dementia. In turn, they felt that emotional and behavioral symptoms were difficult to recognize for family, friends, and healthcare professionals. This made caregivers feel that no one understands them and this resulted in feelings of loneliness.

In the early stages of the caregiving trajectory, caregivers themselves also had difficulty recognizing and understanding the early symptoms of FTD, as these often occurred at a young age and the severity of symptoms gradually increased over time. This may be specific to FTD, as 70–80% of the persons with FTD develop symptoms well before the age of 65 (Knopman & Roberts, Citation2011; Rabinovici & Miller, Citation2010). While Alzheimer’s dementia (AD) is still the most prevalent cause of young-onset dementia (YOD) (Rossor, Fox, Mummery, Schott, & Warren, Citation2010), only 5% of all persons with AD have a symptom onset at a young age (Zhu et al., Citation2015). In FTD, there is a longer delay in diagnosis compared to YOD caused by AD, ranging between 4.1 and 6.4 years (Rosness et al., Citation2008b; van Vliet et al., Citation2013). This has important negative consequences for caregivers as diagnostic delay is associated with high levels of uncertainty, caregiver distress, family or marital conflict, and even financial problems in the period prior to diagnosis (van Vliet et al., Citation2011). Caregivers may experience several internal and external barriers that delay the diagnosis (van Vliet et al., Citation2011, Citation2013). Specific internal factors for caregivers of persons with FTD are, for example, feelings of uncertainty whether or not the symptoms in their relative need to be taken seriously. In line with van Vliet et al. (Citation2013), trivializing remarks from family, friends, and healthcare professionals seemed to enhance these feelings of uncertainty. In turn, caregivers felt they delayed their decision to seek professional help. Prediagnostic uncertainty further increased by typical characteristics of the behavioral variant of FTD, such as changes in character and behavior and a lack of insight, as these symptoms are often not associated with dementia by healthcare professionals (Rosness et al., Citation2008b; Spreadbury & Kipps, Citation2018; van Vliet et al., Citation2011). In particular, the behavioral variant of FTD is difficult to recognize for healthcare professionals due to the overlapping symptomatology with psychiatric disorders (Gossink et al., Citation2016). Our findings also demonstrate that comorbid disease made it difficult for healthcare professionals to interpret early symptoms of FTD. Early recognition is further hampered by the low prevalence of FTD (Onyike & Diehl-Schmid, Citation2013; Rossor et al., Citation2010). Obtaining a timely diagnosis is important as it helps caregivers with adapting to the caregiving role (de Vugt & Verhey, Citation2013). In our study, caregivers perceived the diagnosis as an important milestone because it allowed them to understand the changes in their relative with FTD. Nevertheless, caregivers of persons with the behavior variant of FTD felt that family and friends often continued to struggle with recognizing symptoms. It is known that emotional and behavioral symptoms of dementia are often misattributed to environmental factors or to fall within personal control (Polenick et al., Citation2018). Although family, friends, and healthcare professionals misattributed symptoms in all variants of FTD, this might occur more often in the behavioral variant which is characterized by the inability to empathize with others, recognize emotions, and comply with social norms (Harciarek & Cosentino, Citation2013; Ibañez & Manes, Citation2012). These symptoms also disrupt the relational connection between the caregiver and the person with FTD and are difficult to recognize for family and friends (Massimo et al., Citation2013; Polenick et al., Citation2018). In line with Vasileiou et al. (Citation2017), this resulted in feelings of loneliness in caregivers.

Caregivers in our study confirmed that there is a need for support in the postdiagnostic phase (Rosness et al., Citation2008a; Spreadbury & Kipps, Citation2018). According to caregivers there is only limited appropriate support available and healthcare professionals often have little knowledge about FTD and the challenges that caregivers face. These negative experiences with healthcare will lower the confidence that caregivers have in professional care and may increase the risk for delay in initiation of care and support services (Rabanal, Chatwin, Walker, O'Sullivan, & Williamson, Citation2018; Sikes & Hall, Citation2018). Particularly in the behavioral variant of FTD this is problematic given the high levels of burden and distress experienced by caregivers (Mioshi et al., Citation2013). Therefore, specialized support services and educational programs on FTD for healthcare professionals seem needed to improve postdiagnostic care in FTD (Rabanal et al., Citation2018; Sikes & Hall, Citation2018).

Strengths and limitations

A strength of our study is that we recruited a heterogeneous sample with spouses and other family caregivers who were in different phases of the caregiving trajectory. This provides a comprehensive picture of the lived experiences of FTD caregivers while they engage in the caregiving role. Focus group discussions require caregivers to talk openly about their experiences in front of others, therefore, some caregivers may have felt hesitant to discuss certain sensitive topics. As multiple caregivers from the same family were included, some participants may have provided socially desirable answers or some experiences are overrepresented. To address this, we also asked caregivers to individually reflect on the caregiving role prior to their participation in the group discussion by completing a booklet containing questions and writing a letter to a caregiver peer. We mainly recruited participants via a Dutch peer-support group. It could be that caregivers who experience difficulty in gaining support may experience more need for peer-support. Therefore, these caregivers may be overrepresented in our study.

Future directions and conclusions

A specialized support approach is needed to improve prediagnostic and postdiagnostic care in FTD (Rosness et al., Citation2008a). Our findings provide directions for developing adequate support for FTD caregivers by emphasizing their need for recognition, acknowledgement, and understanding. Care and support services that elicit a sense of recognition in FTD caregivers may lower the threshold to gain timely access to support. In turn, this will facilitate the role adaptation process, which may reduce caregiver burden and distress. Healthcare professionals could play an important role to reduce barriers that caregivers experience when gaining social support (Dam, Boots, Boxtel, Verhey, & de Vugt, Citation2018). Our study adds that healthcare professionals can achieve this by reducing feelings of shame and stigma and by supporting FTD caregivers with actively informing and involving family and friends in the caregiving situation. The medical training of healthcare professionals on FTD seems a prerequisite for facilitating adequate postdiagnostic support to FTD caregivers. Additionally, our findings underscore the importance of peer-support as recognition from peers made caregivers feel heard and reduced feelings of loneliness. As FTD does not fit within the general image people have of dementia, peer-support groups that specifically include caregivers of persons with FTD seem needed to elicit a sense of recognition. Specialized support programs may also be beneficial for FTD caregivers by increasing sense of competence and decreasing burden and distress (Gossink et al., Citation2018a). Given the active life phase of younger caregivers and the low prevalence of FTD, online peer-support and web-based psychosocial support may provide an opportunity to support FTD caregivers, even in remote areas (Diehl-Schmid et al., Citation2013). Our findings show that FTD caregivers often postpone the use of professional healthcare services. Several factors could lower barriers to access support, such as designing tailored support programs that meet the specific needs of FYD caregivers and offering support also outside the healthcare sector, for example, by online programs that can be accessed at a time and place that is convenient for FTD caregivers. Allowing timely access to support may help caregivers of persons with FTD not only to gain more understanding themselves but also experience it from others.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the important role of the Dutch peer-support organization [FTD lotgenoten] during this study. In particular, we would like to express our appreciation to Margreet Mantel for her role as ambassador of the project while recruiting participants. We thank Hendrik-Jan van der Waal, chair of the Dutch peer-support organization, for his assistance with interpreting some of the results. In addition, we would like to express appreciation for Yvette Daniels, Esther Gerritzen, and Anne Marieke Doornweerd for their assistance during the focus group discussions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bang, J., Spina, S., & Miller, B. L. (2015). Frontotemporal dementia. The Lancet, 386, 1672–1682. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00461-4

- Barca, M. L., Thorsen, K., Engedal, K., Haugen, P. K., & Johannessen, A. (2014). Nobody asked me how I felt: Experiences of adult children of persons with young-onset dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 26, 1935–1944. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610213002639

- Boots, L. M. M., Wolfs, C. A. G., Verhey, F. R. J., Kempen, G. I. J. M., & de Vugt, M. E. (2015). Qualitative study on needs and wishes of early-stage dementia caregivers: The paradox between needing and accepting help. International Psychogeriatrics, 27, 927–936. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610214002804

- Bradley, E. H., Curry, L. A., & Devers, K. J. (2007). Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Services Research, 42, 1758–1772. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00684.x

- Caceres, B. A., Frank, M. O., Jun, J., Martelly, M. T., Sadarangani, T., & de Sales, P. C. (2016). Family caregivers of patients with frontotemporal dementia: An integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 55, 71–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.10.016

- Carter, N., Bryant-Lukosius, D., DiCenso, A., Blythe, J., & Neville, A. J. (2014). The use of triangulation in qualitative research. Oncology Nursing Forum, 41, 545–547. doi:https://doi.org/10.1188/14.ONF.545-547

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounded theory. London, United Kingdom: Sage.

- Creswell, J. W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Dam, A. E. H., Boots, L. M. M., Boxtel, M. P. J., Verhey, F. R. J., & de Vugt, M. E. (2018). A mismatch between supply and demand of social support in dementia care: A qualitative study on the perspectives of spousal caregivers and their social network members. International Psychogeriatrics, 30, 881–892. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217000898

- de Vugt, M. E., & Verhey, F. R. J. (2013). The impact of early dementia diagnosis and intervention on informal caregivers. Progress in Neurobiology, 110, 54–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.04.005

- Diehl-Schmid, J., Schmidt, E. M., Nunnemann, S., Riedl, L., Kurz, A., Förstl, H., … Cramer, B. (2013). Caregiver burden and needs in frontotemporal dementia. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 26, 221–229. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988713498467

- Draper, B., Cations, M., White, F., Trollor, J., Loy, C., Brodaty, H., … Withall, A. (2016). Time to diagnosis in young-onset dementia and its determinants: The INSPIRED study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31, 1217–1224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4430

- Ducharme, F., Lévesque, L., Lachance, L., Kergoat, M.-J., & Coulombe, R. (2011). Challenges associated with transition to caregiver role following diagnostic disclosure of Alzheimer disease: A descriptive study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48, 1109–1119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.011

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Evers, J. (2015). Kwalitatieve analyse: Kunst én kunde. Amsterdam, Nederland: Boom Lemma Uitgevers.

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Gossink, F., Dols, A., Krudop, W. A., Sikkes, S. A., Kerssens, C. J., Prins, N. D., … Pijnenburg, Y. A. (2016). Formal psychiatric disorders are not overrepresented in behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 51, 1249–1256. doi:https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-151198

- Gossink, F., Pijnenburg, Y., Scheltens, P., Pera, A., Kleverwal, R., Korten, N., … Dols, A. (2018a). An intervention programme for caregivers of dementia patients with frontal behavioural changes: An explorative study with controlled effect on sense of competence. Psychogeriatrics, 18, 451–459. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12351

- Gossink, F., Schouws, S., Krudop, W., Scheltens, P., Stek, M., Pijnenburg, Y., & Dols, A. (2018b). Social cognition differentiates behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia from other neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric disorders. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26, 569–579. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2017.12.008

- Harciarek, M., & Cosentino, S. (2013). Language, executive function and social cognition in the diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia syndromes. International Review of Psychiatry (Abingdon, England), 25, 178–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2013.763340

- Hogan, D. B., Jetté, N., Fiest, K. M., Roberts, J. I., Pearson, D., Smith, E. E., … Maxwell, C. J. (2016). The prevalence and incidence of frontotemporal dementia: A systematic review. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences / Journal Canadien Des Sciences Neurologiques, 43(S1), S96–S109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/cjn.2016.25

- Ibañez, A., & Manes, F. (2012). Contextual social cognition and the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology, 78, 1354–1362. doi:https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182518375

- Kaizik, C., Caga, J., Camino, J., O'Connor, C. M., McKinnon, C., Oyebode, J. R., … Mioshi, E. (2017). Factors underpinning caregiver burden in frontotemporal dementia differ in spouses and their children. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 56, 1109–1117. doi:https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-160852

- Karnatz, T., Monsees, J., Wucherer, D., Michalowsky, B., Zwingmann, I., Halek, M., … Thyrian, J. R. (2019). Burden of caregivers of patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration - a scoping review. International Psychogeriatrics, 1–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610219000176

- Knopman, D. S., & Roberts, R. O. (2011). Estimating the number of persons with frontotemporal lobar degeneration in the US population. Journal of Molecular Neuroscience, 45, 330–335. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12031-011-9538-y

- Massimo, L., Evans, L. K., & Benner, P. (2013). Caring for loved ones with frontotemporal degeneration: The lived experiences of spouses. Geriatric Nursing (New York, N.Y.), 34, 302–306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2013.05.001

- Mendez, M. F., Fong, S. S., Shapira, J. S., Jimenez, E. E., Kaiser, N. C., Kremen, S. A., & Tsai, P. H. (2014). Observation of social behavior in frontotemporal dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease and Other Dementias, 29, 215–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317513517035

- Mioshi, E., Foxe, D., Leslie, F., Savage, S., Hsieh, S., Miller, L., … Piguet, O. (2013). The impact of dementia severity on caregiver burden in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 27(1), 68–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/WAD.0b013e318247a0bc

- Nunnemann, S., Kurz, A., Leucht, S., & Diehl-Schmid, J. (2012). Caregivers of patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration: A review of burden, problems, needs, and interventions. International Psychogeriatrics, 24, 1368–1386. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s104161021200035x

- Onyike, C. U., & Diehl-Schmid, J. (2013). The epidemiology of frontotemporal dementia. International Review of Psychiatry (Abingdon, England), 25, 130–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/09540261.2013.776523

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Polenick, C. A., Struble, L. M., Stanislawski, B., Turnwald, M., Broderick, B., Gitlin, L. N., & Kales, H. C. (2018). "The filter is kind of broken": Family caregivers' attributions about behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26, 548–556. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2017.12.004

- Rabanal, L. I., Chatwin, J., Walker, A., O'Sullivan, M., & Williamson, T. (2018). Understanding the needs and experiences of people with young onset dementia: A qualitative study. BMJ Open, 8, e021166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021166

- Rabinovici, G. D., & Miller, B. L. (2010). Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: Epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. CNS Drugs, 24, 375–398. doi:https://doi.org/10.2165/11533100-000000000-00000

- Rosness, T. A., Haugen, P. K., & Engedal, K. (2008a). Support to family carers of patients with frontotemporal dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 12, 462–466. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860802224334

- Rosness, T. A., Haugen, P. K., Passant, U., & Engedal, K. (2008b). Frontotemporal dementia: A clinically complex diagnosis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23, 837–842. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1992

- Rossor, M. N., Fox, N. C., Mummery, C. J., Schott, J. M., & Warren, J. D. (2010). The diagnosis of young-onset dementia. The Lancet Neurology, 9, 793–806. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S1474-4422(10)70159-9

- Savin-Baden, M., & Major, C. H. (2013). Qualitative research: The essential guide to theory and practice. Abingdon, England: Routledge.

- Sikes, P., & Hall, M. (2018). The impact of parental young onset dementia on children and young people's educational careers. British Educational Research Journal, 44, 593–607. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3448

- Spreadbury, J. H., & Kipps, C. M. (2018). Understanding important issues in young-onset dementia care: The perspective of healthcare professionals. Neurodegenerative Disease Management, 8(1), 37–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.2217/nmt-2017-0029

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care , 19, 349–357. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- van Vliet, D., Bakker, C., Koopmans, R. T., Vernooij-Dassen, M. J., Verhey, F. R., & de Vugt, M. E. (2010). Research protocol of the NeedYD-study (Needs in Young onset Dementia): A prospective cohort study on the needs and course of early onset dementia. BMC Geriatrics, 10(1), 13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-10-13

- van Vliet, D., de Vugt, M. E., Bakker, C., Koopmans, R. T., Pijnenburg, Y. A., Vernooij-Dassen, M. J., & Verhey, F. R. (2011). Caregivers' perspectives on the pre-diagnostic period in early onset dementia: A long and winding road. International Psychogeriatrics, 23, 1393–1404. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610211001013

- van Vliet, D., de Vugt, M., Bakker, C., Pijnenburg, Y., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Koopmans, R., & Verhey, F. (2013). Time to diagnosis in young-onset dementia as compared with late-onset dementia. Psychological Medicine, 43, 423–432. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291712001122

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Barreto, M., Vines, J., Atkinson, M., Lawson, S., & Wilson, M. (2017). Experiences of loneliness associated with being an informal caregiver: A qualitative investigation. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 585–511. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00585

- Visser, F. S., Stappers, P. J., van der Lugt, R., & Sanders, E. B. N. (2005). Contextmapping: Experiences from practice. CoDesign, 1, 119–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15710880500135987

- Zhu, X. C., Tan, L., Wang, H. F., Jiang, T., Cao, L., Wang, C., … Yu, J. T. (2015). Rate of early onset Alzheimer's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Translational Medicine, 3, 1–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2305-5839.2015.01.19