Abstract

Objectives

Older adults are more likely to encounter adverse life events and have protective factors that are different from other populations. Currently, there is no resilience scale designed exclusively for older adults. This study aims at developing a new measurement scale for assessing resilience of older adults.

Methods

Items of Resilience Scale for Older Adults (RSOA) was generated from thorough literature review. A multiple stage method was applied to examine the psychometric properties of the scale. In pretesting, items that did not meet the psychometric criteria were removed. A sample of 368 older adults was collected in the main survey to perform preliminary item selection and removal, reliability and construct validity analyses. Another survey on 76 samples was then conducted to assess test-retest reliability of the scale.

Results

RSOA that comprised four constructs (personal strength, meaning and purpose of life, family support, and social support) with a total of 15 items was developed with good reliability and validity. Cronbach’s α of the scale was 0.882. All the four constructs were found significantly correlated with life satisfaction of older adults.

Conclusions

The RSOA is a reliable means of assessing psychological and physical resilience of older people as well as predicting their satisfaction with life. The study may also provide important information about elderly coping with adversity.

Introduction

The pace of population aging is increasing dramatically worldwide. Globally in 2019, there were an estimated 703 million older people aged 65 years or older, and the number is projected to surpass 1.5 billion by 2050 (United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division, Citation2019). Such rapid aging has urged countries to address the needs of the aging population.

Older adults often face a myriad of challenges and adversities due to frailty, disability, physical and cognitive impairment, which tend to further increase with advancing age (World Health Organization, Citation2015). In addition to personal health conditions, elderly people are vulnerable to natural disasters, poverty, loneliness, loss and bereavement, as well as social isolation (Hashim, Eng, Tohit, & Wahab, Citation2013; Landeiro, Barrows, Nuttall Musson, Gray, & Leal, Citation2017; United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, n.d.). Moreover, adverse events may lead to mental health problems for elderly people, which can cause depression and eventually low quality of life (World Health Organization, Citation2017).

Growing evidence suggests that elderly people are able to age successfully despite the adversities and limitations (Pruchno, Heid, & Genderson, Citation2015). Resilience, the ability to adapt well and bounce back in the face of adversity, is one of the key components of successful aging (American Psychological Association, Citation2020). Studies have unveiled the association between resilience and successful aging, suggesting that high resilience is a predictor of successful aging (Byun & Jung, Citation2016; Jeste et al., Citation2013; MacLeod, Musich, Hawkins, Alsgaard, & Wicker, Citation2016). Highly resilient elderly people were found to have reduced depression, greater happiness and life satisfaction, which will result in successful aging (Smith & Hollinger-Smith, Citation2015). Thus, the measurement and evaluation of elderly people’s resilience are crucial for developing appropriate responses to the problems they face. However, most resilience scales have only been developed and validated in young and adolescent populations. The concepts of resilience in elderly are different to those in other stages of life despite some resilience scales such as Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC), Resilience Scale (RS) and Brief Resilient Coping Scale (BRCS) were validated in the older population in previous studies (Cosco, Kaushal, Richards, Kuh, & Stafford, Citation2016). These existing scales focus mainly on the assessment of intrinsic resilience factors and have limitations in capturing factors like meaning and purpose of life and other extrinsic factors such as social support from family and society. Thus, the present study aims to develop a concept and appropriate tool for measuring resilience in the elderly population.

Literature review

People’s general impressions of elderly people who are experiencing functional decline in the aging process include them being incapable, disabled, and frail. Despite the age and frailty of elderly people, their wisdom and life experience as well as their positive attitude and active engagement in life facilitate them developing resilience, which promotes successful aging (Byun & Jung, Citation2016; Fontes & Neri, Citation2015). Resilience is generally defined as a dynamic adaptive process that can be developed and changes with time and circumference (American Psychological Association, Citation2020). The role of resilience in successful aging has gained increasing attention nowadays and many studies have discussed the protective factors that promote resilience in older adults. Examples of individual protective factors identified are sense of humor, self-esteem, optimism, and hopefulness (Fontes & Neri, Citation2015; MacLeod et al., Citation2016; McClain, Gullatt, & Lee, Citation2018). Examples of external protective factors encompass community, family, relationship, and cultural factors (Doty, Citation2010; Ledesma, Citation2014).

Dozens of resilience measures have been developed based on various theories, components, and target populations. In the assessment of resilience in later-life, studies revealed that RS, CD-RISC and BRCS had robust psychometric properties that are adequate for the use in older population (Cosco et al., Citation2016; Ho, Lee, & Hu, Citation2012).

The CD-RISC is a self-administered questionnaire measured on a 5-point Likert scale (Connor & Davidson, Citation2003). The scale comprises 25 items that were developed to measure resilience, and is administered to subjects in a variety of populations. The scale has five factors, namely (1) personal competence; (2) trust, tolerance, and the strengthening effects of stress; (3) positive acceptance of change and secure relationships; (4) control; and (5) spiritual influences. The scale was validated in older adults samples (Goins, Gregg, & Fiske, Citation2013; Lamond et al., Citation2008) and showed high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.88–0.93).

The RS was developed based on qualitative interviews of 24 older women. The scale has five domains (equanimity, perseverance, self-reliance, meaningfulness, and existential) with 25 items rated on a 7-point Likert scale (Wagnild & Young, Citation1993). Resnick and Inguito (Citation2011) tested the psychometric properties of RS in two samples of older adults (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83–0.91) but found that there were some items that did not fit the model of RS. Another validation study of Chinese version of RS (RS-CN) showed that the scale is valid and reliable in Chinese older people (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.95) (Yang, Bao, Huang, Guo, & Smith, Citation2015).

The BRCS was originally developed to capture the tendencies to cope with stress in two samples of individuals with rheumatoid arthritis (Sinclair & Wallston, Citation2004). The themes emerge from the 4-items scale includes tenacity, optimism, creativity, aggressive approach to problem solving, and commitment to extract positive growth from adversities. The scale was shown to be valid and reliable in an elderly Spanish sample (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83) (Tomás, Meléndez, Sancho, & Mayordomo, Citation2012). Despite the fact that CD-RISC, RS and BRCS were validated in older people in a handful of early studies, these scales were originally developed in the population that are different from the elderly. The concept of resilience may not be the same in the population facing different types of adversities in life.

Concept and scale development

Given that the maladaptation of elderly people is often caused by more than single adverse experiences, resilience in older adults is complex and diverse at different levels (Hayman, Kerse, & Consedine, Citation2017). An elderly resilience scale should extend from the assessment of individual protective factors to social support from family, spiritual support, and other external environmental factors.

Several studies have identified meaning in life as an important dimension of resilience in older populations (Resnick, Gwyther, & Roberto, Citation2018). Perceived meaning in life was found to be related to resilience and promotion of well-being and mental health in older adults (Heisel & Flett, Citation2016). Resilience was one of the strongest characteristics in older adults with moderate and high levels of purpose in life, and was found to be strongly associated with improved mental and physical health outcomes (Musich, Wang, Kraemer, Hawkins, & Wicker, Citation2018).

Social support from family and friends is particularly salient for older adults (Belanger et al., Citation2016). Social support is defined as on going emotional support and assistance from people an individual can depend on, especially when facing with adversities (Atchley, Citation2000). The impact of social support is generally more critical in elderly institutionalized people who are highly dependent on others (Rash, Citation2007).

Helping people and maintaining strong relationships with god, family, and other people help older adults who are approaching end-of-life to live meaningfully with dignity, and are crucial for improving life satisfaction and quality. Spiritual coping strategies such as spiritual beliefs and religiosity have often been discussed in the resilience of older adults (Baldacchino, Bonello, & Debattista, Citation2014a, Citation2014b; Madsen, Ambrens, & Ohl, Citation2019). Thus, in addition to personal strength, life meaning, religious and spiritual beliefs, and family and social support are critical concepts in elderly resilience.

Since older adults are experiencing adversities that are different from the general population, the CD-RISC, RS, and BRCS do not seem entirely appropriate for measuring their resilience. These resilience scales, which focus mainly on the assessment of intrinsic resilience factors, have limitations in capturing extrinsic factors such as social support from family and society. Furthermore, the scales lack the ability to assess certain resilience factors such as meaning and purpose in life, which are salient for developing resilience in older adults.

We can inferred from literature review that the resilience scale for older population should include the following constructs: personal strength, family support, social support, meaning and purpose in life, and religious or spiritual beliefs. Based on these five concepts and relevant scale items, this study compiled a new resilience scale for older adults (RSOA).

Methods

Scale development

This study reviewed literature related to the resilience and protective factors of older adults to confirm the concept of resilience in older adults and summarize the main constructs. Accordingly, questionnaire items for the scale were formulated to complete the first draft of the RSOA. Face validity of the newly developed RSOA was determined by enrolling elderly care service providers and residents from two caring institutions to participate in two focus group discussions to modify and adjust the items of the scale. Two experts on older adults’ welfare were invited to evaluate the scale content to ensure its content validity. Five residents aged 60 years or older with self-care ability (ADL scores >60) and normal cognitive function (SPMSQ <3 errors) were invited from each of the two caring institutions in the focus group discussions. Eventually, a consensus was attained and a scale comprising 24 items based on 5 constructs was developed for pre-testing. The RSOA is a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 ‘never’ to 5 ‘always’.

Data collection

We recruited older adults from four public and private caring institutions in Taipei and New Taipei City for the purpose of pre-testing. The inclusion criteria were older adults aged 60 years and above, having self-care ability and normal cognitive function. The Barthel Index (BI) was used to measure the self-care ability while Pfeiffer’s Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire (SPMSQ) was used to assess the cognitive function of the older adults. In BI, a score of 60 on ADL is considered to be the threshold for marked dependence (Patricia, Citation2003) while in SPMSQ, 0–2 errors indicate normal mental functioning and ≥3 errors indicate a mild to severe cognitive impairment (Pfeiffer, Citation1975). Older adults with self-care ability and normal cognitive function were those who had ADL score ≥60 and <3 errors on SPMSQ. We included all the older adults who met the inclusion criteria and a total of 226 valid samples were collected. Internal consistency of RSOA was evaluated using item analysis and item-total correlation test while construct validity of the scale was evaluated using exploratory factor analysis (EFA).

In the main survey, data was obtained from seven public and private caring institutions and a day care center in Taipei and New Taipei City. We used the same inclusion criteria as in the pre-testing. A total of 368 valid samples were collected for preliminary item selection and removal as well as reliability and construct validity analyses of the scale. Another sample of 76 older adults was collected from one of the caring institutions and surveyed using the scale two weeks later to examine the test-retest reliability of the RSOA.

Research instruments

In addition to the proposed RSOA, Chinese version of Resilience Scale for Adults (RSA-CN), Chinese version of CD-RISC (CD-RISC-CN) and Taiwan Longitudinal Study on Aging–Life Satisfaction Index (TLSA–LSI) were employed in empirical validity analysis. The 29-items RSA-CN was translated from the original RSA, which was developed to measure the stress-coping abilities and resilience of adults. The scale exhibited good validity and reliability and a higher score indicates greater resilience (Lu, Citation2011; Wang, Citation2007).

The CD-RISC has been widely researched and applied in various countries. The original CD-RISC (Connor & Davidson, Citation2003) was translated into CD-RISC-CN, which has 25-items rated on a 5-point Likert scale. The higher the score obtained, the greater the resilience.

The TLSA-LSI consists of 10 item adopted from the original LSI, which has five constructs, namely zest, resolution and fortitude, congruence between desired and achieved goals, self-concept, and mood tone (Neugarten, Havighurst, & Tobin, Citation1961). Higher total score indicates greater individual’s life satisfaction. The scale was shown to be reliable and valid for assessing life satisfaction of Taiwanese older adults (Lin, Citation2010).

Data analysis

All the statistical analyses in pre-testing were conducted using SPSS (version 21.0) for Windows (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). An independent sample t-test was used in item analysis and item-total correlation coefficients >0.3 were recommended. In EFA, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy (KMO) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity were used to determine the adequacy of the factor analysis. Principal axis factor was then used for factor extraction, followed by varimax rotation. We defined the meaningful factor as having an eigenvalue >1. Pearson product-moment correlation test was then used to analyze the interfactor correlation. After EFA, all items were renumbered to allow internal consistency reliability testing. Items with item-total correlation coefficient <0.3 were deleted from the scale. In the main survey, AMOS statistical software was used to perform confirmatory factor, convergent validity, and discriminant validity analyses to verify the construct validity and reliability of the RSOA. In convergent validity, all factor loadings must reach a 0.05 significance level (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair, Black, Babin, Anderson, & Tatham, Citation2006). Average variance extracted (AVE) method was adopted to test for the discriminant validity. Discriminative validity between constructs exists when the Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient of each construct is less than the square root of AVE. Pearson product-moment correlation test was then used to analyze the empirical validity and test-retest reliability of the scale. Correlation coefficients <0.3, 0.3–0.7, and >0.7 indicate weak, moderate, and strong empirical validity, respectively (Cohen, Citation1988).

Results

Demographic characteristics of the participants

shows the demographic characteristics of the participants in the study. Among the participants, 67.1% were women. A higher proportion of the participants (38.3%) were aged between 71 and 80, followed by the 81 and 91 years age group (31.8%). Nearly one third of all participants had attained a bachelor’s or higher degree (28.3%), followed by elementary graduates or lower education level (28.3%). Most of the participants were living alone (70.7%) and almost half of the participants (47.8%) had three or more children. 40.8% and 32.6% reported to have sufficient and moderately sufficient budget for living expenditures, respectively. In terms of perceived health, 32.1% and 31.5% of the participants perceived themselves as neutral and healthy, respectively. In terms of perceived ADL, a majority of participants (90.8%) deemed themselves as easy or highly easy to complete daily living activities. Lastly, most participants in the study had religious beliefs (76.4%).

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of participants.

Pre-testing

Item analysis

All the obtained composite reliability (CR) values, ranging from −1.977 to −15.465, reached statistical significance (p < 0.05), implying that the 24 items in the RSOA exhibited good discriminatory power (). The item–total correlation coefficient of items A5, A8, A9, A20, A21, and A22 were all <0.3, whereas those of the remaining items were >0.328. A high correlation coefficient indicated a strong relative correlation between the items and high internal consistency. Since the CR values were statistically significant, all the 24-items were temporarily retained for EFA.

Table 2. Item analysis of RSOA in pre-testing.

Exploratory factor analysis

The KMO coefficient of the RSOA was 0.829, showing the adequacy and representativeness of the sample to assess factor structure. The Bartlett’s test of sphericity value was 3124.621 (p < 0.001), indicating that the correlation coefficient of the RSOA was appropriate for factor analysis. Six factors were extracted from the analysis, among which one factor with only two items (items 8 and 9) was deleted because it failed to comply with the standard of three items per factor. The cumulative explanatory variation of the remaining factors was 63.415% (Result not shown). Factors 1–5 were family support, social support, meaning and purpose of life, personal strength, and religious and spiritual beliefs.

The correlation coefficient between Factors 1 and 5 of the retest version of RSOA was statistically non-significant. The remaining inter-factor coefficients ranged between 0.144 and 0.586. The correlation coefficients between five factors and the entire scale were in the range of 0.383–0.812 (), which proved that the scale possesses good construct validity.

Table 3. Correlation coefficients between constructs of RSOA.

Internal consistency

After removing the factor with two items, the reliability of the five factors with 22 items left in the RSOA was tested and the result showed that the correlation coefficients between the total score and three items—Items B14, B20, and B7—were <0.3 (). Reliability analysis was repeated on the remaining 19-items in RSOA after deleting the three items with an item–total correlation coefficient <0.3. The Cronbach’s α coefficient was 0.882 for the overall scale, with the Cronbach’s α of the five subscales ranging from 0.682–0.941, indicating good internal consistency reliability of the pre-test version of RSOA. All item–total correlation coefficients of the 19-items RSOA ranged from 0.436 to 0.899 ().

Table 4. Reliability analysis of RSOA.

Confirmatory factor analysis

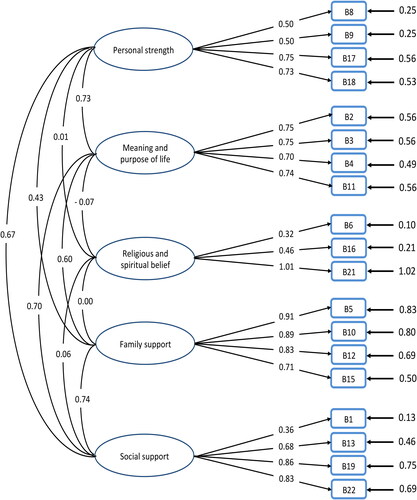

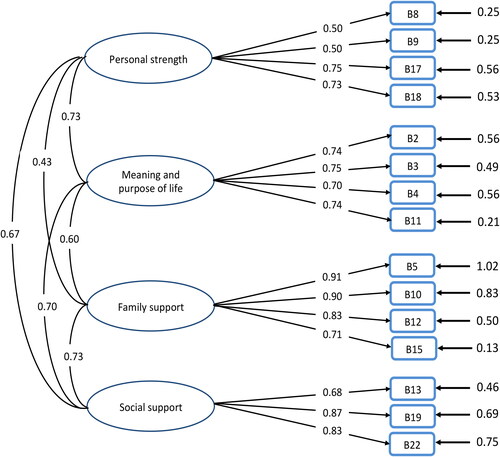

Regarding the framework of the test model for the RSOA, each of the five factors had corresponding items, thereby forming five first-order potential factors (). Regarding the basic goodness-of-fit (GOF) test of the model, no negative error variances or excessive standard errors were found among the parameter estimates. Thus, the model met the evaluation criteria (Hair et al., Citation2006). The absolute values of the correlation coefficients between all parameters did not approximate 1; moreover, all error variances reached statistical significance. Items B1, B6, B16 (factor loading <0.5) and B21 (factor loading >1) violated the estimation criteria and were removed from the scale for subsequent analysis (). After the adjustment, the 15-items in RSOA met the evaluation criteria (factor loadings = 0.50–0.91) and showed a good overall fit ().

Figure 1. Confirmatory factor analysis model of RSOA (before correction).

RSOA: Resilience Scale of Older Adults.

Figure 2. Confirmatory factor analysis model of RSOA (after correction).

RSOA: Resilience Scale of Older Adults.

The chi-square value for the GOF between the theoretical model and observed data was statistically significant (χ2(df = 84)=264.9, p < 0.05). However, because chi-square values are more likely to achieve statistical significance with larger sample sizes (Hair et al., Citation2006), other GOF indicators had to be considered when the model’s GOF was evaluated (Jöreskog & Sörbom, Citation1993). The GOF indices obtained in this study—comparative fit index = 0.938, Tucker-Lewis index = 0.911, root mean square error of approximation = 0.072, and standardized root mean square residual = 0.07—all satisfied the requirement. In sum, the proposed RSOA exhibited sufficient GOF between theoretical model and observed data, indicating that the theoretical model was able to explain the observed data.

Convergent validity and discriminant validity

shows the results of reliability of latent constructs in RSOA. All the factor loading were >0.5. The item reliability of each subscale ranged between 0.25 and 0.83. AVE values of the four latent constructs were 0.399, 0.537, 0.708, and 0.708, with only the AVE of personal strength being less than the 0.50 standard. The composite reliability values of the four latent constructs were 0.719, 0.823, 0.906, and 0.906, all of which were higher than the evaluation standard criterion of 0.70. The scale exhibited good convergent validity and ideal internal quality.

Table 5. Reliability, discriminant validity, empirical validity and test-retest reliability of RSOA.

also demonstrates that the correlation coefficients of all constructs were less than the square roots of AVE, and this implied satisfactory overall discriminant validity among the four constructs.

Empirical validity

The four constructs of the RSOA that were significantly correlated with TLSA–LSI (correlation coefficient = 0.361–0.542), CD-RISC-CN (correlation coefficient = 0.484–0.728), and RSA-CN (correlation coefficient = 0.556–0.649) were shown in . Strong empirical validity was observed between the RSOA and CD-RISC-CN (correlation coefficient = 0.748) as well as RSA-CN (correlation coefficient = 0.751).

Among the constructs of the RSOA, meaning and purpose of life had the highest correlation with TLSA–LSI, which implied that the construct could best predict the life satisfaction of older adults. The construct was also highly correlated with CD-RISC-CN and RSA-CN ().

Test-retest reliability

The constructs and the RSOA had highly correlated test-retest reliability (correlation coefficients = 0.572–0.794), except for the social support construct, which demonstrated moderately correlated test-retest reliability (correlation coefficient = 0.572). With a correlation coefficient of 0.794, the RSOA achieved good test-retest reliability ().

Discussion

The RSOA, which can be used to obtain a more holistic view on resilience of older adults, was developed in this study. Item analysis in the pre-testing revealed that all items in the proposed scale exhibited good discriminatory power. Five constructs of the scale (family support, social support, meaning and purpose of life, personal strength, and religious and spiritual beliefs) were derived from the EFA. The subsequent analyses revealed that the proposed scale had good construct validity and internal consistency reliability. In the main survey, religious and spiritual beliefs and four items were removed from the scale in confirmatory factor analysis. The final version of RSOA comprised a total of 15 items under four constructs. As a theoretical model, the RSOA was proven effective at explaining the real-world observed data. Moreover, the scale exhibited good convergent validity and satisfactory discriminant validity among the four constructs. The contents of the scale were thus proven to have excellent quality.

The constructs of the RSOA were found significantly correlated with the TLSA–LSI, CD-RISC-CN, and RSA-CN. Additionally, a higher than moderate level of empirical validity was observed between the RSOA and the three scales. The results proved the RSOA is effective at predicting resilience and life satisfaction of older adults. Meaning and purpose of life construct could best predict the life satisfaction of older adults. This construct was also highly correlated with the CD-RISC-CN and RSA-CN. This renders the meaning and purpose of life crucial to the life satisfaction and development of resilience in older adults. Lastly, the RSOA demonstrated good test-retest reliability in this study.

Doty (Citation2010) deemed adversity and adaptation to be two key concepts of resilience. Protective factors for resilience are particularly crucial in the face of adversity. Personal protective factors are primarily associated with hope and belief, optimism, self-esteem, the meaning and purpose of life, determination and perseverance, problem-solving ability, self-regulation ability, emotion management ability, and other life skills. External-environmental protective factors mainly depend on family support, social support, religious beliefs, and culture (Ledesma, Citation2014; Madsen et al., Citation2019). The proposed RSOA covers four constructs, namely personal strength, family support, social support, and meaning and purpose of life. The scale contents span personal adaptive skills, family and social resources, and opinions on the meaning of an individual’s life. The implications of the factors in the RSOA resonate with the definition and connotation of resilience proposed by the majority of researchers, thereby enabling the connotations of resilience in older adults to be sufficiently evaluated.

Furthermore, a higher than moderate level of empirical validity was observed between the four constructs of the proposed scale and the TLSA–LSI, CD-RISC-CN and RSA-CN. Relevant studies have discovered a positive correlation between the resilience and life satisfaction of older adults and concluded that older adults with greater resilience tend to be more satisfied with life (Hayat, Khan, & Sadia, Citation2016; Jahangir, Amir, & Parvaneh, Citation2017; Jeste et al., Citation2013; Smith & Hollinger-Smith, Citation2015). This implied that the proposed scale can effectively predict older adults’ life satisfaction while suitably serving as a tool for predicting psychological and physical resilience. Hayat et al. (Citation2016) found that resilience was significantly correlated with life satisfaction of older adults living in a nursing home but showed insignificantly result among those living at home. Given that older adults often face drastic life changes caused by involuntary relocation to a nursing home or long-term care institutions, resilience serves its purpose to protect older adults from these life adversities. Hence, older adults living in long-term care institutions have to maintain their resilience to obtain life satisfaction.

Meaning and purpose of life is one of the crucial factors of positive wellbeing (Fotuhi & Mehr, Citation2015). We found that the meaning and purpose of life subscale could best predict the life satisfaction of older adults. This is consistent with a study that reported a positive correlation between meaning and purpose of life and life satisfaction of older adults (Oliveira et al., Citation2019). Another study among community-dwelling older adults also confirmed the relationship of meaning in life with quality of life, which is the degree of overall life satisfaction (Chui, Citation2018). Besides, meaning and purpose of life in RSOA was found highly correlated with the CD-RISC-CN and RSA-CN. Our result is in line with previous study that indicated a significant and positive correlation between meaning and purpose of life and resilience among older adults (Mohseni, Iranpour, Naghibzadeh-Tahami, Kazazi, & Borhaninejad, Citation2019).

Social and family support is vital resources for older adults facing physical and psychological deterioration and changes in family life. Social support for older adults can come in the form of emotional and tangible assistance, both of which are conducive to facing adversities. More specifically, social support can be categorized into emotional support (concern and respect), self-esteem support (positive feedback or support for their values/concepts), and tangible support (financial assistance and care) (Wu & Chen, Citation2017). Serving as key factors that influence the quality of life and happiness of older adults, family and social supports are particularly imperative in older age (Belanger et al., Citation2016; Patil et al., Citation2014; Rash, Citation2007) and are critical factors for improving resilience in older adults (Southwick et al., Citation2016). Therefore, this study incorporated social and family supports into the RSOA to more comprehensively measure the resilience of the older population.

Research limitations and suggestions

This study had several limitations that open avenues for further research. First, the concept and item development of the scale were generated through deductive approach, which were based on thorough literature review. We suggest combining both deductive and inductive methods in future study on RSOA. Qualitative interview with older population could be done in future to identify broader and more comprehensive items of the RSOA. Second, our samples were drawn from caring institutions and day care center. Older adults living in caring institution and day care center in Taiwan need to pay for their care service and most of them have no difference with general older population in terms of physical and mental health as well as financial status. Nevertheless, these residents may have slightly different characteristics compared to older population in general even though we have only recruited those with self-care ability and normal cognitive function. Further testing and validation in general older population and other regions are warranted to prove the reliability and generalization of the RSOA. Furthermore, more samples are required to verify the measurement invariance and applicability of the proposed scale.

In sum, the RSOA is the first scale designed to measure resilience in older adults. The scale, which has good quality, reliability and validity, could be introduced as a main assessment tool for older adults and their caregivers in understanding their level of resilience and enable them to confront and adapt to adversity accordingly. Moreover, the scale would be helpful to the government in formulating guidance and interventions for older adults to develop their resilience and improve quality of life.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychological Association. (2020). The road to resilience. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience

- Atchley, R. C. (2000). Social forces and aging: An introduction to social gerontology (9th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

- Baldacchino, D. R., Bonello, L., & Debattista, C. J. (2014a). Spiritual coping of older people in Malta and Australia (part 1). British Journal of Nursing (Mark Allen Publishing), 23(14), 792–799. doi:https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2014.23.14.792

- Baldacchino, D. R., Bonello, L., & Debattista, C. J. (2014b). Spiritual coping of older persons in Malta and Australia (part 2). British Journal of Nursing (Mark Allen Publishing), 23(15), 843–846. doi:https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2014.23.15.843

- Belanger, E., Ahmed, T., Vafaei, A., Curcio, C. L., Phillips, S. P., & Zunzunegui, M. V. (2016). Sources of social support associated with health and quality of life: A cross-sectional study among Canadian and Latin American older adults. BMJ Open, 6(6), e011503. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011503

- Byun, J., & Jung, D. (2016). The influence of daily stress and resilience on successful ageing. International Nursing Review, 63(3), 482–489. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12297

- Chui, R. C. F. (2018). The role of meaning in life for the quality of life of community-dwelling Chinese elders with low socioeconomic status. Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine, 4, 1–8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2333721418774147

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

- Cosco, T. D., Kaushal, A., Richards, M., Kuh, D., & Stafford, M. (2016). Resilience measurement in later life: A systematic review and psychometric analysis. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 14(16), 16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016-0418-6

- Doty, B. (2010). The construct of resilience and its application to the context of political violence. Pursuit - The Journal of Undergraduate Research at the University of Tennessee, 1(1), 137–154.

- Fontes, A. P., & Neri, A. L. (2015). Resilience in aging: Literature review. Ciencia & Saude Coletiva, 20(5), 1475–1495. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232015205.00502014

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

- Fotuhi, M., & Mehr, S. (2015). The science behind the powerful benefits of having a purpose: Purpose in life is one of the main components of quality of life. Practical Neurology. Retrieved from https://practicalneurology.com/articles/2015-sept/the-science-behind-the-powerful-benefits-of-having-a-purpose

- Goins, R. T., Gregg, J. J., & Fiske, A. (2013). Psychometric properties of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale with older American Indians: The Native Elder Care Study. Research on Aging, 35(2), 123–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027511431989

- Hair, J. F. J., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hashim, S. M., Eng, T. C., Tohit, N., & Wahab, S. (2013). Bereavement in the elderly: The role of primary care. Mental Health in Family Medicine, 10(3), 159–162.

- Hayat, S. Z., Khan, S., & Sadia, R. (2016). Resilience, wisdom, and life satisfaction in elderly living with families and in old-age homes. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 31(2), 475–494.

- Hayman, K. J., Kerse, N., & Consedine, N. S. (2017). Resilience in context: The special case of advanced age. Aging & Mental Health, 21(6), 577–585. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1196336

- Heisel, M. J., & Flett, G. L. (2016). Does recognition of meaning in life confer resiliency to suicide ideation among community-residing older adults? A longitudinal investigation. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 24(6), 455–466. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2015.08.007

- Ho, H. Y., Lee, Y. L., & Hu, W. Y. (2012). Elder resilience: A concept analysis. The Journal of Nursing, 59(2), 88–92.

- Jahangir, K., Amir, S., & Parvaneh, K. (2017). The prediction of life satisfaction among the elderly based on resilience and happiness. Journal of Aging Psychology, 2(4), 229–236.

- Jeste, D. V., Savla, G. N., Thompson, W. K., Vahia, I. V., Glorioso, D. K., Martin, A. S., … Depp, C. A. (2013). Association between older age and more successful aging: Critical role of resilience and depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(2), 188–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030386

- Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (1993). LISREL 8: Structural equation modeling with the SIMPLIS command language. Chicago, IL: Scientific Software International.

- Lamond, A. J., Depp, C. A., Allison, M., Langer, R., Reichstadt, J., Moore, D. J., … Jeste, D. V. (2008). Measurement and predictors of resilience among community-dwelling older women. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(2), 148–154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.007

- Landeiro, F., Barrows, P., Nuttall Musson, E., Gray, A. M., & Leal, J. (2017). Reducing social isolation and loneliness in older people: A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open, 7(5), e013778. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013778

- Ledesma, J. (2014). Conceptual frameworks and research models on resilience in leadership. SAGE Open, 4(3), 1-8. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014545464

- Lin, T. H. (2010). Stability, predictors, and sensitivity of Life Satisfaction Index Scores among Taiwanese older adults (master’s thesis). Taiwan: National Taiwan University. Airiti Library. Retrieved from https://www.airitilibrary.com/Publication/alDetailedMesh?docid=U0001-2807201017035100

- Lu, C. H. (2011). Association between resilience and posttraumatic stress symptoms among motor vehicle accident patients (maters’s thesis). Taiwan: National Taiwan University. Airiti Library. Retrieved from https://www.airitilibrary.com/Publication/alDetailedMesh?docid=U0001-2912201118501600

- MacLeod, S., Musich, S., Hawkins, K., Alsgaard, K., & Wicker, E. R. (2016). The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatric Nursing, 37(4), 266–272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.02.014

- Madsen, W., Ambrens, M., & Ohl, M. (2019). Enhancing resilience in community-dwelling older adults: A rapid review of the evidence and implications for public health practitioners. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 14. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00014

- McClain, J., Gullatt, K., & Lee, C. (2018). Resilience and protective factors in older adults (master’s thesis). California: Dominican University of California. Dominican scholar. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.33015/dominican.edu/2018.OT.11

- Mohseni, M., Iranpour, A., Naghibzadeh-Tahami, A., Kazazi, L., & Borhaninejad, V. (2019). The relationship between meaning in life and resilience in older adults: A cross-sectional study. Health Psychology Report, 7(2), 133–138. doi:https://doi.org/10.5114/hpr.2019.85659

- Musich, S., Wang, S. S., Kraemer, S., Hawkins, K., & Wicker, E. (2018). Purpose in life and positive health outcomes among older adults. Population Health Management, 21(2), 139–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1089/pop.2017.0063

- Neugarten, B. L., Havighurst, R. J., & Tobin, S. S. (1961). The measurement of life satisfaction. Journal of Gerontology, 16, 134–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/16.2.134

- Oliveira, D. V. D., Ribeiro, C. C., Pico, R. E. R., Murari, M. O., Freire, G. L. M., Contreira, A. R., & Nascimento Júnior, J. R. A. D. (2019). Is life satisfaction associated with the purpose in life of elderly hydrogymnastics practitioners? Motriz: Revista de Educação Física, 25(3), e101962. doi:https://doi.org/10.1590/s1980-6574201900030009

- Patil, B., Shetty, N., Subramanyam, A., Shah, H., Kamath, R., & Pinto, C. (2014). Study of perceived and received social support in elderly depressed patients. Journal of Geriatric Mental Health, 1(1), 28–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.4103/2348-9995.141921

- Patricia, P. (2003). Measures of adult general functional status. Arthritis & Rheumatism, 49(S5), S15–S27.

- Pfeiffer, E. (1975). A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 23(10), 433–441. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x

- Pruchno, R., Heid, A. R., & Genderson, M. W. (2015). Resilience and successful aging: Aligning complementary constructs using a life course approach. Psychological Inquiry, 26(2), 200–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2015.1010422

- Rash, E. M. (2007). Social support in elderly nursing home populations: Manifestations and influences. The Qualitative Report, 12(3), 375–396.

- Resnick, B., Gwyther, L. P., & Roberto, K. A. (2018). Resilience in aging: Concepts, research, and outcomes (2nd ed.). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

- Resnick, B. A., & Inguito, P. L. (2011). The Resilience Scale: Psychometric properties and clinical applicability in older adults. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 25(1), 11–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2010.05.001

- Sinclair, V. G., & Wallston, K. A. (2004). The development and psychometric evaluation of the Brief Resilient Coping Scale. Assessment, 11(1), 94–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191103258144

- Smith, J. L., & Hollinger-Smith, L. (2015). Savoring, resilience, and psychological well-being in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 19(3), 192–200. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.986647

- Southwick, S. M., Sippel, L., Krystal, J., Charney, D., Mayes, L., & Pietrzak, R. (2016). Why are some individuals more resilient than others: The role of social support. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 15(1), 77–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20282

- Tomás, J. M., Meléndez, J. C., Sancho, P., & Mayordomo, T. (2012). Adaptation and initial validation of the BRCS in an elderly Spanish sample. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28(4), 283–289. doi:https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000108

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (n.d.). Income poverty in old age: An emerging development priority. Retrieved from https://www.un.org/esa/socdev/ageing/documents/PovertyIssuePaperAgeing.pdf

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. (2019). World population ageing 2019: Highlight. Retrieved from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/3846855?ln=en

- Wagnild, G. M., & Young, H. M. (1993). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Resilience Scale. Journal of Nursing Measurement, 1(2), 165–178.

- Wang, S. Y. (2007). Associations of sense of self, resilience and posttraumatic stress symptoms among burn patients (master’s thesis). Taiwan: National Taiwan University. Airiti Library. Retrieved from https://www.airitilibrary.com/Publication/alDetailedMesh1?DocID=U0001-0507200716175600

- World Health Organization. (2015). World report on ageing and health. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/ageing/events/world-report-2015-launch/en/

- World Health Organization. (2017). Mental health of older adults. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults

- Wu, S. T., & Chen, C. Y. (2017). Relationships between social support, social participation, and active aging for and in aged people. Journal of Gerontechnology and Service Management, 5(4), 331–352.

- Yang, F., Bao, J. M., Huang, X. H., Guo, Q., & Smith, G. D. (2015). Measurement of resilience in Chinese older people. International Nursing Review, 62(1), 130–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12168