Abstract

Objectives

To effectively reduce loneliness in older adults, interventions should be based on firm evidence regarding risk factors for loneliness in that population. This systematic review aimed to identify, appraise and synthesise longitudinal studies of risk factors for loneliness in older adults.

Methods

Searches were performed in June 2018 in PsycINFO, Scopus, Sociology Collection and Web of Science. Inclusion criteria were: population of older adults (M = 60+ years at outcome); longitudinal design; study conducted in an OECD country; article published in English in a peer-review journal. Article relevance and quality assessments were made by at least two independent reviewers.

Results

The search found 967 unique articles, of which 34 met relevance and quality criteria. The Netherlands and the United States together contributed 19 articles; 17 analysed national samples while 7 studies provided the data for 19 articles. One of two validated scales was used to measure loneliness in 24 articles, although 10 used a single item. A total of 120 unique risk factors for loneliness were examined. Risk factors with relatively consistent associations with loneliness were: not being married/partnered and partner loss; a limited social network; a low level of social activity; poor self-perceived health; and depression/depressed mood and an increase in depression.

Conclusion

Despite the range of factors examined in the reviewed articles, strong evidence for a longitudinal association with loneliness was found for relatively few, while there were surprising omissions from the factors investigated. Future research should explore longitudinal risk factors for emotional and social loneliness.

Loneliness in old age has adverse consequences for well-being, physical and mental health, and mortality (Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris, & Stephenson, Citation2015; Leigh-Hunt et al., Citation2017; Rico-Uribe et al., Citation2018). While many studies have examined correlates of loneliness, fewer have explored risk factors for loneliness prospectively. An understanding of such risk factors is crucial for the development and implementation of effective interventions to alleviate loneliness, and longitudinal studies offer better evidence than cross-sectional studies for causal mechanisms due to the temporal relationship between predictor and outcome. This article reports the findings of a systematic review of longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in older adults.

A common definition of loneliness states that loneliness is ‘a discrepancy between one’s desired and achieved levels of social relations’ (Perlman & Peplau, Citation1981, p. 32). This discrepancy may concern the number of relationships, frequency of contact, or the intimacy or quality of the relationships. Sometimes, definitions of loneliness specify two dimensions: emotional and social, where emotional loneliness refers to the absence of a close emotional attachment, while social loneliness refers to the absence of an engaging social network (Weiss, Citation1973).

There have been several reviews of loneliness in older adults. Some systematic reviews and meta-analyses have focused on consequences of loneliness in people of all ages or in adults, for example in terms of health and mortality (for an overview of reviews, see Leigh-Hunt et al., Citation2017), while a scoping review has summarised studies on loneliness and health in older adults (Courtin & Knapp, Citation2017). Other reviews have focused on interventions to reduce loneliness in older adults (for overviews of reviews, see Fakoya, McCorry, & Donnelly, Citation2020; Victor et al., Citation2018).

There have also been reviews examining risk factors for loneliness, although these have mainly included cross-sectional studies. For example, Pinquart and Sörensen (Citation2001, Citation2003) undertook meta-analyses of risk factors for loneliness in older adults based on cross-sectional studies. Routasalo and Pitkala (Citation2003) noted in their review of risk factors for loneliness that only a few studies of older adults were of longitudinal design. A recent review including both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies (Cohen-Mansfield, Hazan, Lerman, & Shalom, Citation2016) concluded that most associations between risk factors and loneliness had been examined in cross-sectional studies.

Although there is a growing body of longitudinal research on loneliness, to date no systematic review has summarised the evidence-base on longitudinal risk factors for loneliness in older adults. This article aims to identify, appraise and summarise available longitudinal research on risk factors for loneliness in older adults.

Methods

The reporting of this systematic review mostly follows the Preferred Reporting Items of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, although these were not developed for reviews of risk factors (Liberati et al., Citation2009; Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & The Prisma Group, Citation2009). A review protocol has been registered at the international prospective register of systematic review (PROSPERO; 2018 CRD42018091159).

Inclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied:

Population: older adults, defined as an average age of 60 years or older among participants at point of outcome measurement

Exposure: any risk factor for loneliness

Outcome: loneliness

Study design: quantitative longitudinal

Setting: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country

Publication type: peer-review journal articles

Publication language: English

Time period: no restriction

Search strategy for identification of studies

The search strategy was developed with support from a librarian. The literature search was conducted on 25 June 2018 and included studies published up to this date. The search covered the following databases: PsycINFO, Scopus, Sociology Collection and Web of Science. The search combined four groups of keywords: 1) loneliness, 2) older adults, 3) longitudinal design, and 4) risk factor (see Supplement A for an example). Additional relevant articles were identified via, e.g. reference lists of included articles and previous reviews.

Selection of studies

Article relevance was assessed using a checklist based on the inclusion criteria presented above. Titles and abstracts of articles identified via the database search were examined independently by two of the authors (A.F., M.N.) and obviously irrelevant articles were removed. For the remaining articles, a full-text relevance assessment was made independently by two authors (A.F., M.N.). Disagreements were resolved via discussion with one or both of the other authors (L.D., K.J.M.). Reasons for exclusion of articles at this stage were recorded (see Supplement B) and double-checked for accuracy (L.D.).

Quality assessment (risk of bias)

Most quality criteria for systematic reviews are developed for the assessment of intervention studies and are not necessarily appropriate for other study designs. For the purpose of this review, the authors were guided in the development of their own quality criteria by those proposed by others (Boyle, Citation1998; SBU, Citation2014). The criteria used related to aspects of sampling, measurement, and analysis. For further details, see Supplement C.

Two authors (A.F., M.N.) independently quality assessed each relevant article. The assessments based on individual criteria were discussed with the other two authors (L.D., K.J.M.) who agreed an overall assessment for each article. Studies assessed as being of low quality were not included in the synthesis of results in this review.

Data extraction and analysis

Data were extracted from the articles by one of the authors (L.D.) and double-checked for accuracy by a research assistant (E.A.) (see ). When articles failed to provide clear methodological information on e.g. recruitment, response rate or attrition rate, where possible such information was determined by two authors together (L.D., K.J.M.) based on details available in the article, or in separate technical reports.

Table 1. Characteristics of included articles.

Findings from the articles were summarised in a narrative synthesis. All predictive bivariate and/or multivariable associations between a risk factor and global loneliness reported in an article are listed in and indicated to be: significant and positive (high levels of the factor predict high levels of loneliness); significant and negative (high levels of the factor predict low levels of loneliness); or non-significant. A small number of articles considered risk factors for recovery from loneliness, but we have not reported their findings. Where an article presented associations for emotional and social loneliness but not global loneliness, we report a single association if they were consistent; if they differed in significance or direction, we specify this and report the separate associations. Most articles used p<.05 as the level of significance for a statistical test, and this is the level used in this review. Associations of p ≥.05 are therefore reported as non-significant even if described as significant in the article.

Table 2. Results of risk factors for loneliness.

The associations obtained from baseline to follow-up are reported. For articles with multiple data collection waves where more than one longitudinal association was analysed, a single result is reported where associations across waves were consistent or where the form of analysis provided only one association. Where there was variation in the association across different waves, these findings are reported separately. Baseline and follow-up(s) are standardised across studies regardless of the time interval between waves and indicated as: T0 (baseline); T1 (first follow-up); T2 (second follow-up), etc. If in an article there were several multivariable models analysing associations between (sub)sets of risk factors and loneliness, the associations in the final/full model have been reported. Where an article addressed a subgroup of the population, this is specified.

We do not report: variables included in articles but for which the longitudinal association with loneliness was not reported; moderator effects; and associations between loneliness at baseline and loneliness at follow-up(s) – the latter, when presented, were always statistically significant and positive.

In several cases conceptually similar risk factors were operationalised and labelled in divergent ways across articles. Where in the consensual judgement of two of the authors (L.D., K.J.M.) differently labelled factors were effectively operationalisations of the same construct, variations in labelling were standardised and the findings for those risk factors are listed together under a single label. The original labels and operationalisations for all measures of risk factors in the articles are presented in Supplement D.

Results

Article selection

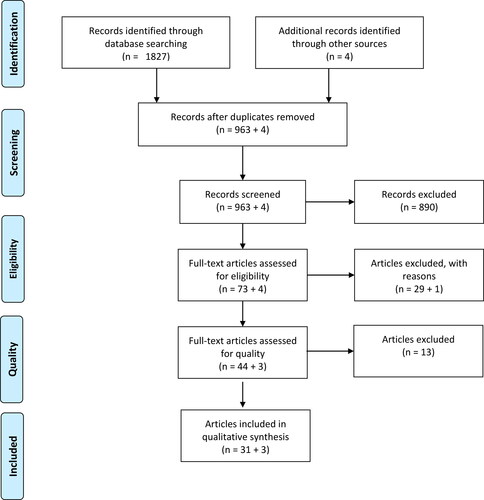

A flow chart of the selection process is presented in . After screening of titles and abstracts of a total of 967 articles, 890 non-relevant articles were excluded and after assessment of the full text another 30 articles were removed (see Supplement B for reasons for exclusion).

Quality assessment was made of the 47 relevant articles (see Supplement C), with an overall grading of high quality, i.e. low risk of bias (2 articles), medium to high quality (3), medium quality (22), medium to low quality (7) and low quality (13). The 13 articles found to be of low quality were excluded from this review, thus N = 34 articles were included.

The characteristics of the included articles are presented in . The articles described studies from eleven countries, with the highest representation from the Netherlands (10 articles), the United States (9), the United Kingdom (4), and Sweden (3). One article was based on an international study that included Belgium and the Netherlands, and 17 articles were based on national studies, representing Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United States. While the earliest article was published in 1999, over half were published between 2015 and 2018.

Methods of included articles

Several major studies were the source of data for a considerable number of the articles included in this review: the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam and/or the linked studies Living Arrangements and Social Networks of Older Adults and the Widowhood Adaptation Longitudinal Study (5 articles); the English Longitudinal Study on Ageing (3); the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (3); the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study (2); the Norwegian Study of the Life Course, Ageing and Generations (2); the Swedish Panel Study of Living Conditions of the Oldest Old (2); and the Zutphen Elderly Study (2).

A majority of the articles (n = 20) used several data collection methods. Among those based on a single data collection method, an interview-completion questionnaire was most common (8) followed by a self-completion questionnaire (3) or a combination of interview- and self-completion questionnaires (3). A response rate was reported in half of the articles (n = 17) and attrition reported in approximately a fifth (7). The response rate varied from 45% (Cacioppo, Chen, & Cacioppo, Citation2017; Cacioppo, Hawkley, & Thisted, Citation2010) to 87% (Dahlberg, Andersson, McKee, & Lennartsson, Citation2015; Taekema, Gussekloo, Maier, Westendorp, & de Craen, Citation2010), while attrition varied from 3% (Aartsen & Jylhä, Citation2011) to 48% (Pronk et al., Citation2014).

Fifteen of the articles included two waves of data collection in the analysis, eight articles included three waves and the remaining articles included more than three. Nearly half of the articles (n = 16) covered a period of up to five years from baseline data collection to final follow-up, with two articles including follow-ups of 20 years or more (Aartsen & Jylhä, Citation2011; Dahlberg, Andersson, & Lennartsson, Citation2018).

Participants

The analytic samples in the articles ranged in size from N = 111 (van Baarsen, Citation2002) to N = 11,010 (Böger & Huxhold, Citation2018). The majority of articles included a general population of older adults (n = 24), albeit often restricted to those living in the community (n = 14). However, some articles included a specific subgroup of the population, e.g. people with depression (Houtjes et al., Citation2014) or those who had recently lost their partner (van Baarsen, Citation2002). Some articles only included individuals that were not lonely at baseline (Aartsen & Jylhä, Citation2011; Moreh, Jacobs, & Stessman, Citation2010; Pikhartova, Bowling, & Victor, Citation2016).

The average age of the participants at baseline varied between 59 and 85 years, and approximately half of the articles had samples with an average age of 70 years or older (information not given in six articles). Women formed the majority of participants in 23 articles (information not given in six articles). Two articles were based on a study that only included men (Rius-Ottenheim et al., Citation2012; Tijhuis, de Jong Gierveld, Feskens, & Kromhout, Citation1999).

Measures of loneliness

There are two main approaches to measuring loneliness: via a single item or via multi-item scales. As shown in , over a third of the articles (n = 13) measured loneliness via the de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, usually the 11-item version (n = 11); and nearly a third of the articles (n = 11) measured loneliness via the UCLA Loneliness Scale, usually the 3-item version (n = 9). In the remaining articles (n = 10) single items were used to measure loneliness. While the wording and response options of the single items varied across articles, all measured frequency of loneliness, usually with four response options.

Measures of risk factors for loneliness

Supplement D provides an overview of the risk factors for loneliness examined in each article and how these factors were described and measured. We grouped the risk factors into five main categories: demographic; socio-economic; social; health-related; and psychological. In 34 reviewed articles we found 120 unique risk factors. This figure includes two risk factors measured only as change variables (factors analysed as both standard predictor variables and as change variables are counted once).

Results of risk factors for loneliness

presents the results of risk factors for loneliness. To simplify the presentation, the results of some unique risk factors that occupy a similar conceptual area are grouped together. For example, within the main category of socio-economic factors, the unique risk factors 1) not having enough money and 2) household assets/wealth are grouped together under the label financial situation.

Demographic factors

Measures of age and gender were included in most of the articles, although sometimes without presentation of their associations with loneliness. In bivariate analyses an increased risk of loneliness was found in people of greater age in four out of six articles (Dahlberg et al., Citation2015; Newall et al., Citation2009; Nicolaisen & Thorsen, Citation2014; Pikhartova et al., Citation2016). However, a positive association between age and loneliness was found in multivariable analyses in only 4 out of 16 articles (Donovan et al., Citation2017; Dykstra, van Tilburg, & de Jong Gierveld, Citation2005; Sutin, Stephan, Carretta, & Terracciano, Citation2015; Taube, Kristensson, Midlöv, Holst, & Jakobsson, Citation2013).

Similarly, whereas five out of six articles found an increased risk of loneliness for women in bivariate analyses (Aartsen & Jylhä, Citation2011; Cohen-Mansfield, Shmotkin, & Goldberg, Citation2009; Dahlberg et al., Citation2015; Nicolaisen & Thorsen, Citation2014; Pikhartova et al., Citation2016), only 2 out of 15 articles found a positive association in multivariable analyses (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2009; Donovan et al., Citation2017) while 2 articles found a negative association (Dykstra et al., Citation2005; van Baarsen, Citation2002).

Ethnicity has only been examined as a longitudinal risk factor in five articles. One article (Warner & Adams, Citation2016) found that being of Hispanic ethnicity compared to White reduced the risk of being lonely, while another (Cacioppo et al., Citation2017) found this to be the case for Black ethnicity.

Socio-economic factors

Relatively few articles examined socio-economic risk factors. The financial factors examined were household income, income-to-needs ratio and financial situation. The only article to examine household income at the bivariate level found a negative association with loneliness (Pikhartova et al., Citation2016), while of the three articles examining this relationship at the multivariable level only one found an association, where medium to high and low household income increased the risk of loneliness relative to high household income (Donovan et al., Citation2017). One article examined the income-to-needs-ratio and found no association with loneliness (Hawkley & Kocherginsky, Citation2018). Four articles examined the financial situation of older adults: out of two articles examining the relationship between not having enough money and loneliness, one article found a positive association (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2009); while one out of two articles found that household assets or wealth decreased the risk of loneliness (Donovan et al., Citation2017).

Socio-economic position was examined via measures of education, social status and employment status. Higher levels of education were associated with a decrease in the risk of loneliness in two out of five articles in bivariate analyses (Nicolaisen & Thorsen, Citation2014; Pikhartova et al., Citation2016) and in two out of ten articles in multivariable analyses (Donovan et al., Citation2017; Sutin et al., Citation2015). One article examined social status, finding a negative association with loneliness (Pikhartova et al., Citation2016). The same article found being employed to be negatively associated with loneliness in a bivariate analysis, whereas the only article to examine being employed at the multivariable level found no association (Hawkley & Kocherginsky, Citation2018).

Social factors

Many different social factors were examined. Marital or partner status was considered in fifteen articles. Three out of five articles found that being married/partnered reduced the risk of loneliness in bivariate analyses (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2009; Nicolaisen & Thorsen, Citation2014; Pikhartova et al., Citation2016), while five out of 11 articles found the same association in multivariable analyses (Deckx et al., Citation2015; Dykstra et al., Citation2005; Nicolaisen & Thorsen, Citation2012; Pikhartova et al., Citation2016; Tijhuis et al., Citation1999; Yang, Citation2018). One article found an increased risk of loneliness for widowed persons in both bivariate and multivariable analyses (Dahlberg et al., Citation2015). However, Brittain et al. (Citation2017) found that compared to not being widowed, being widowed in the last four years was not associated with loneliness, while being widowed for more than five years was associated with a decreased risk of loneliness.

With regard to marital or partner status change, five out of six articles that examined partner loss (i.e. becoming separated, divorced or widowed) found an increased risk of loneliness (Aartsen & Jylhä, Citation2011; Dahlberg et al., Citation2015; Dykstra et al., Citation2005; Nicolaisen & Thorsen, Citation2014; Tijhuis et al., Citation1999).

Living arrangement was analysed at bivariate level in two articles and at multivariable level in six articles. Three articles found that living alone increased the risk of loneliness (Brittain et al., Citation2017; Newall et al., Citation2009; Taube et al., Citation2013), while one article found that household size decreased the risk of loneliness (Pikhartova et al., Citation2016). Two out of three articles that examined the relationship between being in residential care and loneliness found a positive association (Brittain et al., Citation2017; Tijhuis et al., Citation1999).

Social contacts was examined in a variety of ways. One out of two articles found higher numbers of social contacts reduced the risk of loneliness in bivariate analyses (Dahlberg et al., Citation2015), although no association was found in multivariable analyses in two articles. In multivariable analyses, three out of five studies found that a larger social network was protective of loneliness (Böger & Huxhold, Citation2018; Donovan et al., Citation2017; Dykstra et al., Citation2005). Pikhartova et al. (Citation2016) found that a greater number of close relationships reduced the risk of loneliness. Various aspects of social contacts change were also examined. One article found that the loss of close friends increased the risk of loneliness (Aartsen & Jylhä, Citation2011), although this association became non-significant at the multivariable level; and one article found that a reduction in one’s social network increased the risk of loneliness (Dykstra et al., Citation2005). In five other analyses of aspects of social contact change across three articles, all associations with loneliness were non-significant.

Relationship quality and relationship quality change was almost exclusively examined in multivariable analyses. In the only article presenting bivariate analyses, Margelisch, Schneewind, Violette, and Perrig-Chiello, (Citation2017) found high marital satisfaction to be negatively associated with social and emotional loneliness, although only the association with social loneliness remained significant in multivariable analyses. Warner and Adams (Citation2016) found a negative association with loneliness when examining positive marital quality. Nine other aspects of relationship quality were examined across four articles, but an association with loneliness was found in only two analyses: higher friendship strain (Hawkley & Kocherginsky, Citation2018) and receiving verbal abuse by family (Wong & Waite, Citation2017) both increased the risk of loneliness. When considering relationship quality change, Yang (Citation2018) found that a reduced closeness to one’s partner was positively associated with loneliness, while Warner and Adams (Citation2016) found increased positive marital quality reduced risk. Neither change in negative marital quality nor change in family and friendship strain were associated with loneliness (both Warner & Adams, Citation2016).

Social support was examined in seven articles. Cacioppo et al. (Citation2010) found social support to reduce the risk of loneliness. Other aspects of social support were examined in 11 multivariable analyses across 5 articles, resulting in three associations with loneliness: marital support prior to widowhood (van Baarsen, Citation2002), family support (Hawkley & Kocherginsky, Citation2018; Wong & Waite, Citation2017), and emotional support (Dahlberg et al., Citation2018) all reduced the risk of loneliness. Emotional support also reduced the risk of loneliness at the bivariate level in one out of two articles (Dahlberg et al., Citation2018).

When examining social activity and/or social activity change, greater social activity was found to decrease the risk of loneliness at the bivariate level in one out of three articles (Newall et al., Citation2009) and in each of three articles at the multivariable level (Böger & Huxhold, Citation2018; Dahlberg et al., Citation2018; Newall et al., Citation2009). Specific social activities were investigated in five analyses across four articles, with four non-significant analyses and one in which being a member of organisations and active in the neighbourhood was negatively associated with loneliness (Pikhartova et al., Citation2016). One article examined social activity change and found that a reduction in social activity increased the risk of loneliness (Aartsen & Jylhä, Citation2011).

Life events was examined in three articles. No association with loneliness was found for either traumatic or significant live events, but positive associations were found for each of three childhood events (Nicolaisen & Thorsen, Citation2014). Sutin et al. (Citation2015) found an increased risk of loneliness in individuals that had experienced discrimination based on: age; weight; physical disability; or physical appearance. Discrimination based on other factors was not associated with loneliness.

Health-related factors

Negative associations with loneliness were found in three out of four articles that examined self-perceived health in bivariate analyses (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2009; Nicolaisen & Thorsen, Citation2014; Pikhartova et al., Citation2016) and in three out of six articles in multivariable analyses (Dykstra et al., Citation2005; Tijhuis et al., Citation1999; van Baarsen, Citation2002). Self-perceived health compared to people the same age was also found to be negatively associated with loneliness (Newall et al., Citation2009), but self-perceived physical health was not (Hawkley & Kocherginsky, Citation2018). Self-perceived health change was examined in five articles, and two articles found a reduction in self-perceived health to increase the risk of loneliness (Dykstra et al., Citation2005; Tijhuis et al., Citation1999).

A greater number of health conditions was found to increase the risk of loneliness at the bivariate level in one article (Newall et al., Citation2009), but no associaiton was found at the multivariable level in two articles (Böger & Huxhold, Citation2018; Donovan et al., Citation2017). Various health conditions and general measures of health were examined in five articles. Co-morbidity (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2009) and leg pain (Taube et al., Citation2013) were found to increase loneliness, while health status was found to decrease loneliness (Newall et al., Citation2009).

While three articles examined cognitive functioning and found no association with loneliness, one article focusing on cognitive functioning change found that compared to not being impaired, both becoming or being persistently impaired increased risk (Deckx et al., Citation2015). Memory functioning was found to decrease the risk of loneliness in one article (Ayalon, Shiovitz-Ezra, & Roziner, Citation2016)

Functional limitations and functional limitations change were variously examined. Two articles that considered limitations in activities of daily living (ADLs) found positive associations with loneliness (Hawkley & Kocherginsky, Citation2018; Warner & Adams, Citation2016). Two articles examined limitations in instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), one of which found a positive bivariate association with loneliness, but no multivariable association (Newall et al., Citation2009). Limitations in ADLs and IADLs combined ((I)ADLs) were examined in five articles, of which two found positive associations with loneliness (Brittain et al., Citation2017; Dykstra et al., Citation2005). An increase in limitations in (I)ADLs was found to increase the risk of loneliness in one out of two articles (Dykstra et al., Citation2005). In the only article to consider mobility problems, a positive association with loneliness was found at the bivariate, but not multivariable, level, while changes in mobility problems had no association (Dahlberg et al., Citation2015).

Fatigue was examined in two articles, with one article finding a positive association with loneliness in a bivariate analysis while the multivariable analysis found the same association in participants aged 85 at follow-up, but not in those aged 78 (Moreh et al., Citation2010). Examining fatigue change, Deckx et al. (Citation2015) found that compared to non-fatigued participants, there was an increased risk of loneliness in the persistently fatigued, but not for participants who became fatigued or who were no longer fatigued.

Psychological factors

Many different psychological factors were considered, but most in only a single article. However, several articles examined depression or depressed mood. Depression was found to increase the risk of loneliness in three out of three articles in bivariate analyses (Cacioppo et al., Citation2010, Citation2017; Pikhartova et al., Citation2016) and in two out of four articles in multivariable analyses (Brittain et al., Citation2017; Donovan et al., Citation2017). One article examined depression change in people with depression, and found remission to decrease and chronic depression to increase the risk of loneliness (Houtjes et al., Citation2014). Depressed mood was found to increase the risk of loneliness in two out of three articles in bivariate analyses (Cacioppo et al., Citation2017; Dahlberg et al., Citation2015) and in one out of three articles in multivariable analyses (Dahlberg et al., Citation2015). Depressed mood change was also considered in three articles, and an increase in depressed mood was found to be consistently positively associated with loneliness (Aartsen & Jylhä, Citation2011; Cacioppo et al., Citation2017; Dahlberg et al., Citation2015).

An additional 27 psychological risk factors were examined across 15 articles. Self-perceived mental health was found to decrease loneliness (Warner & Adams, Citation2016), while anxiety was found to increase loneliness (Wong & Waite, Citation2017). Various aspects of affect have been considered, with negative affect (Böger & Huxhold, Citation2018), hopelessness (Gum, Shiovitz-Ezra, & Ayalon, Citation2017), increased nervousness (Aartsen & Jylhä, Citation2011), and increased feelings of uselessness (Aartsen & Jylhä, Citation2011) all found to be positively associated with loneliness. The five factor model of personality (Costa & McCrae, Citation1985) has been examined in three articles. Openness was found to decrease loneliness at T2, but not T1 (Taube et al., Citation2013). Two articles found no association between neuroticism and global loneliness (Cacioppo et al., Citation2010; Taube et al., Citation2013). However, one article found that neuroticism increased the risk of emotional, but not social, loneliness (Margelisch et al., Citation2017). In one article, having an older subjective age was positively associated with loneliness (Pikhartova et al., Citation2016). Other articles found that self-centeredness increased loneliness (Cacioppo et al., Citation2017) and that mastery (Nicolaisen & Thorsen, Citation2012) and optimism (Rius-Ottenheim et al., Citation2012) decreased loneliness. Finally, different perceptions of loneliness have been examined, with both self-comparison processes (Brittain et al., Citation2017) and stereotypes and expectations of old age being associated with loneliness (Pikhartova et al., Citation2016).

Discussion

Main findings on risk factors’ associations with loneliness

Many different risk factors were examined in the 34 articles in this review. While significant associations with loneliness were plentiful, relatively consistent associations with loneliness across several articles were found for only a few risk factors. The risk factors that stand out in this respect are: not being married/partnered and partner loss; a limited social network; a low level of social activity; poor self-perceived health; and depression/depressed mood and an increase in depression.

Approximately half of the articles that examined being married/partnered found this to be associated with a decreased risk of loneliness, while loss of a partner was found to increase risk in almost all analyses. A previous review similarly found strong support for an increased risk of loneliness among people without a partner such as widows and widowers (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2016).

Despite social contacts being examined in a variety of ways across several articles, there was surprisingly little evidence of an important role in loneliness. Still, in more than half of the articles that examined one’s social network, a more extensive network decreased the risk of loneliness. A reduction in one’s social network was also found to increase risk. Similarly, if religious activity is excluded then higher levels of social activity were found to decrease the risk of loneliness in a majority of analyses. The evidence for an association between social support and loneliness was inconsistent, and less than half of the analyses of relationship quality found an association. This review therefore provides a different picture to that of a meta-analysis of cross-sectional research of correlates of loneliness, which found that measures of quality in social relations had stronger associations with loneliness than measures of quantity (Pinquart & Sörensen, Citation2003). Our findings are also not fully consistent with socio-emotional selectivity theory (Carstensen, Fung, & Charles, Citation2003), in which it is argued that the active maintainence of a small number of emotionally meaningful relationships provides a foundation for well-being in later life.

Previous reviews based only or primarily on cross-sectional research found evidence of associations between physical and mental health factors and loneliness (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2016; Pinquart & Sörensen, Citation2003). Our review found self-perceived health to be one of the most investigated risk factors, with more than half of the analyses indicating that good self-perceived health decreases the risk of loneliness. The evidence for an association between functional limitations and an increased risk of loneliness was more mixed, being consistent for ADL limitations in two articles but less consistent for IADL and (I)ADL limitations. The majority of analyses of depression found it increases the risk of loneliness, while an increase in depressed mood was found to increase risk in all analyses. A previous review has shown that depression and loneliness often co-occur and that there are reciprocal influences over time between loneliness and depressive symptomatology (O'Luanaigh & Lawlor, 2008).

Some findings relating to other risk factors are worth highlighting. Previous reviews based primarily on cross-sectional studies found evidence that loneliness is associated with female gender and greater age (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2016; Pinquart & Sörensen, Citation2003). These findings are echoed in our review when considering analyses at the bivariate level, but not those at the multivariable level. This failure to replicate bivariate associations at the multivariable level suggests that these associations are at least partly due to factors that co-occur with female gender and greater age, such as reduced health and functioning and widowhood. There were also indications in our review that low income and poor financial conditions increase the risk of loneliness, but most articles examining education did not find an association. These findings resonate with a resource perspective on loneliness (see Tesch-Römer & Huxhold, Citation2019) and can also be compared with those of a meta-analysis in which both income and education were associated with loneliness, with the greatest effect for income (Pinquart & Sörensen, Citation2003). Finally, while only two articles considered perceptions of loneliness via self-comparison processes and stereotypes of ageing, all analyses found significant associations with loneliness (Brittain et al., Citation2017; Pikhartova et al., Citation2016). Taken together with the finding that an older subjective age was associated with an increase in loneliness (Pikhartova et al., Citation2016), these results are consistent with a cognitive perspective on loneliness (see Tesch-Römer & Huxhold, Citation2019) and suggest that older adults’ subjective perceptions of loneliness and old age merit further investigation.

Research focus and gaps

The amount of longitudinal research on risk factors for loneliness has more than doubled in the last few years, and the range of risk factors that have been investigated is considerable. However, many of these risk factors have been considered in, at best, a few articles, and some in only one. Thus, there were several articles focusing on social contacts as a risk factor, yet social contacts was operationalised variously across articles such that, e.g. the number of close relationships or having close friends were each analysed as risk factors only once. Health-related factors have mostly been examined via self-perceived health and (I)ADL limitations. Perhaps surprisingly only a few articles examined cognitive impairment as a risk factor for loneliness, while the only form of sensory impairment considered was hearing impairment. Similarly, research on psychological factors was dominated by a focus on depression and depressed mood, with most other psychological factors each investigated in only one article. Taken collectively, the current evidence-base for longitudinal risk factors for loneliness can be described as broad but shallow.

Even given the breadth of risk factors examined there were some notable absences. For example, no articles examined mental health issues such as personality disorders or psychosis nor existential factors that may contribute to loneliness. Social contact with children also received little attention. None of the reviewed articles examined the separate effects of having daughters or sons, or the effect of contact with grandchildren. These seem strange omissions given the important role of adult children in the informal care of older adults and the significant role of older adults in childcare and in the care of other older adults (Evandrou, Falkingham, Gomez-Leon, & Vlachantoni, Citation2018; Verbakel, Tamlagsrønning, Winstone, Fjaer, & Eikemo, Citation2017). Cross-sectional research has found that receiving informal care is associated with lower levels of emotional loneliness in older adults (Dahlberg & McKee, Citation2014) and that older adults with a perceived need of informal care but receiving none have higher levels of social loneliness (Dahlberg & McKee, Citation2016). A recent cross-sectional study found that higher levels of stress in informal carers of people with dementia are associated with higher levels of loneliness (Victor et al., in press). However, a longitudinal study published after the inclusion period of this review found no association between being an informal carer and loneliness (Hajek & Konig, Citation2019).

Similarly, while three articles in our review analysed living in, or entry to, residential care, no articles considered social care more broadly, such as the receipt of home help, day care, respite care etc. Cross-sectional research has found that older adults in receipt of social care have higher levels of social loneliness (Dahlberg & McKee, Citation2014), while cross-country comparisons suggest that welfare states can enable social participation and reduce loneliness (Nyqvist, Nygard, & Scharf, Citation2019) and that differences regarding, e.g. material deprivation and lack of access to health care are associated with differences in loneliness (Morgan et al., Citation2021). The assessment of how such macro-level factors might influence loneliness is limited by the lack of international comparative longitudinal studies. In our review, only one article analysed data from more than one country, and that article did not present cross-country comparisons (Deckx et al., Citation2015). There is also a lack of research on the relationship between meso-level factors and loneliness, for example community-level factors or urban vs. rural residence, while factors on the border of meso- and micro-levels are also largely absent, e.g. neighbourhood integration (cf. Gibney, Zhang, & Brennan, Citation2020; Gyasi & Adam, Citation2020; Tesch-Römer & Huxhold, Citation2019).

Few risk factors were examined that could be said to relate to a life course perspective. Such a perspective when studying older adults can only truly be achieved through analysing data over a significant part of the lifespan. However, only two articles included follow-ups of over 20 years (Aartsen & Jylhä, Citation2011; Dahlberg et al., Citation2018).

Although 13 articles in this review used the bidimensional de Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale, only 6 of them analysed emotional and social loneliness separately. A similar research limitation has been observed in longitudinal research on interventions to reduce loneliness (Masi, Chen, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, Citation2011). Although emotional and social loneliness are correlated, articles identified risk factors unique to each dimension (Deckx et al., Citation2015; Margelisch et al., Citation2017; Pronk et al., Citation2011; van Baarsen, Citation2002). There is thus a need for more longitudinal research into risk factors for loneliness that distinguishes between emotional and social loneliness.

Quality of included articles

The reviewed articles often lacked information on sampling frame and methodology, while response and attrition rates were often not reported and/or not analysed. Such problems were particularly common in articles based on the major longitudinal studies. Readers should not be required to seek out figures from secondary sources to reach an informed assessment of an article’s quality. Data analysis was another area where a thorough quality assessment was often compromised. The analysis of longitudinal data can involve complex statistical modelling that cannot be satisfactorily described in a couple of sentences. Many clinical and medical journals have restrictive word counts for articles, which can limit the description of modelling to the point that an informed assessment of its adequacy is not possible.

The comparison of findings for risk factors across articles was made difficult by the variation in operationalisation and measurement of similar constructs, including loneliness. As noted elsewhere (Victor et al., Citation2018), it is difficult to judge the extent to which various single-items, scales and versions of scales measuring loneliness correspond to each other. Approximately a third of the articles in this review measured loneliness via a single item. While single-item measures can possess face validity, they may have limited sensitivity, particularly if the item has a small number of response options. This problem of limited sensitivity is exacerbated by two related issues: a) the frequently-reported finding that responses to loneliness items and scales are heavily skewed, and b) the common practice of dichotomising the loneliness measure, thus reducing its sensitivity even further. A further limitation of single-item measures is that they cannot discriminate between different dimensions of loneliness.

Strengths and limitations

This is the first systematic review of longitudinal risk factors of loneliness in older adults. One of the strengths of the review is its scope, that is, the inclusion of all variables examined for their predictive associations with loneliness. However, this scope means that it was not practical to provide a more nuanced assessment of each individual risk factor. The variability in the measurement of risk factors and of loneliness also militated against presenting the associations between risk factors and loneliness with more precision. The assemblage of individual risk factors into categories and the combination of results for similar constructs measured in different ways across articles, should be considered critically. For transparency and to facilitate analysis, descriptions of how each risk factor was operationalised in the articles are presented in this review.

As was true of most articles, we adopted p<.05 as the criteria of significance for the association between a risk factor and loneliness. However, few studies applied corrections for multiple testing or otherwise addressed the family-wise error rate. Over half the articles reviewed analysed data from only seven studies, so the problem of alpha inflation in these articles is particularly acute. This issue should also be considered in the context of the well-known bias in scientific publishing in which non-significant findings are less likely to be submitted for publication.

The review was limited to articles published in English describing research carried out in high income countries, although no article was excluded from the review on the latter criterion. As with all systematic reviews, there is a risk that we have failed to identify all relevant articles, for example, as a consequence of the search strategy and choice of databases. To minimise this risk, we applied a rigorous search strategy whereby we conducted searches in several databases and combined this with searches via other routes. The risk of rejecting relevant articles was reduced by using two independent researchers.

Conclusions: Further research and recommendations for practice

In 34 reviewed articles we found 120 unique risk factors. Many of these risk factors were significantly associated with loneliness. However, relatively few risk factors could be said to have compellingly consistent associations with loneliness across a considerable number of articles and at both bivariate and multivariable levels. With a handful of exceptions, we regard the evidence-base for longitudinal risk factors for loneliness to be broad but shallow. Additionally, there are several variables that demonstrate promise as potential longitudinal risk factors for loneliness where further research is justified and required; and, despite the range and quantity of risk factors examined there remain surprising omissions where theory or cross-sectional evidence would suggest investigation is warranted. Further longitudinal research that considers emotional and social dimensions of loneliness is also recommended; the failure to analyse these two dimensions separately has implications for the development of effective loneliness interventions.

An overview of reviews concluded that interventions to reduce loneliness designed for specific needs of targeted populations have a greater potential to be beneficial (Victor et al., Citation2018). Our review provides relatively strong evidence that certain sub-groups of the older adult population are at a higher risk of loneliness. These include: older adults that are not married/partnered, particularly those who have recently lost their partner; individuals with a limited social network and/or low levels of social activity; older adults with poor self-perceived health; and those with depression/depressed mood. If we are to reduce the levels of loneliness in the general adult population, this might best be achieved by using the resources available to develop interventions targeting older adults with the characteristics listed above. When developing interventions, thought should also be given to which risk factors are most easy to assess and change in older adults. Different intervention strategies will be required for risk factors that can be thought of as triggers for loneliness, such as the loss of a partner, those linked to an older adult’s social context such as their social network and social activities, and those of a more dispositional nature, such as depression (cf. Pinquart & Sörensen, Citation2001).

Author contributions

Protocol development; relevance and quality assessments; review and final approval of manuscript: all authors. Data searches: A.F. and M.N. Data analyses; original draft of manuscript; funding acquisition: L.D. and K.J.M. Project management: L.D.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (505.4 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Gunilla Fahlström at the Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Studies for valuable advice, and to Erika Augustsson at Aging Research Center, Karolinska Institutet/Stockholm University, for double-checking .

Declaration of interest

Two of the authors have been involved in two of the articles included in this review.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aartsen, M., & Jylhä, M. (2011). Onset of loneliness in older adults: Results of a 28 year prospective study. European Journal of Ageing, 8(1), 31–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-011-0175-7

- Ayalon, L., Shiovitz-Ezra, S., & Roziner, I. (2016). A cross-lagged model of the reciprocal associations of loneliness and memory functioning. Psychology and Aging, 31(3), 255–261. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000075

- Böger, A., & Huxhold, O. (2018). Do the antecedents and consequences of loneliness change From middle adulthood into old age? Developmental Psychology, 54(1), 181–197. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000453

- Boyle, M. H. (1998). Guidelines for evaluating prevalence studies. Evidence-Based Mental Health, 1(2), 37–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmh.1.2.37

- Brittain, K., Kingston, A., Davies, K., Collerton, J., Robinson, L. A., Kirkwood, T. B. L., … Jagger, C. (2017). An investigation into the patterns of loneliness and loss in the oldest old – Newcastle 85+ Study. Ageing and Society, 37(1), 39–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X15001142

- Cacioppo, J. T., Chen, H. Y., & Cacioppo, S. (2017). Reciprocal Influences Between Loneliness and Self-Centeredness: A Cross-Lagged Panel Analysis in a Population-Based Sample of African American, Hispanic, and Caucasian Adults. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(8), 1125–1135. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217705120

- Cacioppo, J. T., Hawkley, L. C., & Thisted, R. A. (2010). Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychology and Aging, 25(2), 453–463. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017216

- Carstensen, L. L., Fung, H. H., & Charles, S. T. (2003). Socioemotional selectivity theory and the regulation of emotion in the second half of life. Motivation and Emotion, 27(2), 103–123. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024569803230

- Cohen-Mansfield, J., Hazan, H., Lerman, Y., & Shalom, V. (2016). Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults: A review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(4), 557–576. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610215001532

- Cohen-Mansfield, J., Shmotkin, D., & Goldberg, S. (2009). Loneliness in old age: Longitudinal changes and their determinants in an Israeli sample. International Psychogeriatrics, 21(6), 1160–1170. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610209990974

- Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1985). The NEO personality inventory manual. Odessa, FL.: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Courtin, E., & Knapp, M. (2017). Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: A scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(3), 799–812. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12311

- Dahlberg, L., Andersson, L., & Lennartsson, C. (2018). Long-term predictors of loneliness in old age: Results of a 20-year national study. Aging & Mental Health, 22(2), 190–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1247425

- Dahlberg, L., Andersson, L., McKee, K. J., & Lennartsson, C. (2015). Predictors of loneliness among older women and men in Sweden: A national longitudinal study. Aging & Mental Health, 19(5), 409–417. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.944091

- Dahlberg, L., & McKee, K. J. (2014). Correlates of social and emotional loneliness in older people: Evidence from an English community study. Aging & Mental Health, 18(4), 504–514. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.856863

- Dahlberg, L., & McKee, K. J. (2016). Living on the edge: Social exclusion and the receipt of informal care in older people. Journal of Aging Research, 2016, 6373101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/6373101

- Deckx, L., van den Akker, M., van Driel, M., Bulens, P., van Abbema, D., Tjan-Heijnen, V., … Buntinx, F. (2015). Loneliness in patients with cancer: The first year after cancer diagnosis. Psycho-Oncology, 24(11), 1521–1528. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3818

- Donovan, N. J., Wu, Q., Rentz, D. M., Sperling, R. A., Marshall, G. A., & Glymour, M. M. (2017). Loneliness, depression and cognitive function in older US adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(5), 564–573. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4495

- Dykstra, P. A., van Tilburg, T. G., & de Jong Gierveld, J. (2005). Changes in older adult loneliness: Results from a seven-year longitudinal study. Research on Aging, 27(6), 725–747. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027505279712

- Evandrou, M., Falkingham, J., Gomez-Leon, M., & Vlachantoni, A. (2018). Intergenerational flows of support between parents and adult children in Britain. Ageing and Society, 38(2), 321–351. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X16001057

- Fakoya, O. A., McCorry, N. K., & Donnelly, M. (2020). Loneliness and social isolation interventions for older adults: A scoping review of reviews. Bmc Public Health, 20(1), 129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-8251-6

- Fisher, G. G., & Ryan, L. H. (2018). Overview of the Health and Retirement Study and introduction to the special issue. Work, Aging and Retirement, 4(1), 1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/wax032

- Gibney, S., Zhang, M., & Brennan, C. (2020). Age-friendly environments and psychosocial wellbeing: A study of older urban residents in Ireland. Aging & Mental Health, 24(12), 2022–2033. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1652246

- Gum, A. M., Shiovitz-Ezra, S., & Ayalon, L. (2017). Longitudinal associations of hopelessness and loneliness in older adults: Results from the US health and retirement study. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(9), 1451–1459. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217000904

- Gyasi, R. M., & Adam, A. M. (2020). Does financial inclusion predict a lower risk of loneliness in later life? Evidence from the AgeHeaPsyWel-HeaSeeB study 2016. Aging & Mental Health. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1786006

- Hajek, A., & Konig, H. H. (2019). Impact of informal caregiving on loneliness and satisfaction with leisure-time activities. Findings of a population-based longitudinal study in germany. Aging & Mental Health, 23(11), 1539–1545. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1506739

- Hawkley, L. C., & Kocherginsky, M. (2018). Transitions in loneliness among older adults: A 5-year follow-up in the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project. Research on Aging, 40(4), 365–387. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027517698965

- Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for mortality: A meta-analytic review. Perspectives on Psychological Science : a Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614568352

- Hoogendijk, E. O., Suanet, B., Dent, E., Deeg, D. J. H., & Aartsen, M. J. (2016). Adverse effects of frailty on social functioning in older adults: Results from the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. Maturitas, 83, 45–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2015.09.002

- Houtjes, W., van Meijel, B., van de Ven, P. M., Deeg, D., van Tilburg, T., & Beekman, A. (2014). The impact of an unfavorable depression course on network size and loneliness in older people: A longitudinal study in the community. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(10), 1010–1017. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4091

- Huisman, M., Poppelaars, J., van der Horst, M., Beekman, A. T. F., Brug, J., van Tilburg, T. G., & Deeg, D. J. H. (2011). Cohort profile: The Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. International Journal of Epidemiology, 40(4), 868–876. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyq219

- Klaus, D., Engstler, H., Mahne, K., Wolff, J. K., Simonson, J., Wurm, S., & Tesch-Römer, C. (2017). Cohort profile: The German Ageing Survey (DEAS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 46(4), 1105–1105g. +. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyw326

- Knipsher, C. P. M., de Jong Gierveld, J., van Tilburg, T., & Dykstra, P. A. (Eds.). (1995). Living arrangements and social networks of older adults. Amsterdam: VU University Press.

- Lappegård, T., & Veenstra, M. (Eds.). (2010). Life-course, generation and gender. LOGG 2007. Field report of the Norwegian Generations and Gender Survey. Oslo: Statistics Norway.

- Leigh-Hunt, N., Bagguley, D., Bash, K., Turner, V., Turnbull, S., Valtorta, N., & Caan, W. (2017). An overview of systematic reviews on the public health consequences of social isolation and loneliness. Public Health, 152, 157–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2017.07.035

- Lennartsson, C., Agahi, N., Hols-Salén, L., Kelfve, S., Kåreholt, I., Lundberg, O., … Thorslund, M. (2014). Data resource profile: The Swedish Panel Study of Living Conditions of the Oldest Old (SWEOLD). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(3), 731–738. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyu057

- Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gotzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., … Moher, D. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: Explanation and elaboration. BMJ, 339(jul21 1), b2700–b2700. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700

- Margelisch, K., Schneewind, K. A., Violette, J., & Perrig-Chiello, P. (2017). Marital stability, satisfaction and well-being in old age: Variability and continuity in long-term continuously married older persons. Aging & Mental Health, 21(4), 389–398. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1102197

- Masi, C. M., Chen, H. Y., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2011). A Meta-Analysis of Interventions to Reduce Loneliness. Personality and Social Psychology Review : An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 15(3), 219–266. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868310377394

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G, & The Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339(jul21 1), b2535–b2535. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2535

- Moreh, E., Jacobs, J. M., & Stessman, J. (2010). Fatigue, function, and mortality in older adults. Journals of Gerontology Series a-Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 65(8), 884–892. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glq064

- Morgan, D., Dahlberg, L., Waldegrave, C., Mikulionienė, S., Rapolienė, G., Lamura, G., & Aartsen, M. (2021). Revisiting loneliness: Individual and country-level changes. In K. Walsh, T. Scharf, A. Wanka & S. Van Regenmortel (Eds.), Social exclusion in ageing societies: Interdisciplinary and policy perspectives. New York, NY: Springer.

- Newall, N. E., Chipperfield, J. G., Clifton, R. A., Perry, R. P., Swift, A. U., & Ruthig, J. C. (2009). Causal beliefs, social participation, and loneliness among older adults: A longitudinal study. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 26(2-3), 273–290. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407509106718

- Nicolaisen, M., & Thorsen, K. (2012). Impairments, mastery and loneliness. A prospective study of loneliness among older adults. Norsk Epidemiologi, 22(2), 143–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.5324/nje.v22i2.1560

- Nicolaisen, M., & Thorsen, K. (2014). Loneliness among men and women-a five-year follow-up study . Aging & Mental Health, 18(2), 194–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.821457

- Nyqvist, F., Nygard, M., & Scharf, T. (2019). Loneliness amongst older people in Europe: A comparative study of welfare regimes. European Journal of Ageing, 16(2), 133–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-018-0487-y

- Luanaigh, C. O., & Lawlor, B. A. (2008). Loneliness and the health of older people. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(12), 1213–1221. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2054

- O’Muircheartaigh, C., English, N., Pedlow, S., & Kwok, P. K. (2014). Sample design, sample augmentation, and estimation for wave 2 of the NSHAP. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(Suppl 2), S15–S26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu053

- Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. A. (1981). Toward a social psychology of loneliness. In S. Duck & R. Gilmour (Eds.), Personal relationships in disorder (pp. 31–56). London: Academic Press.

- Pikhartova, J., Bowling, A., & Victor, C. (2016). Is loneliness in later life a self-fulfilling prophecy? Aging & Mental Health, 20(5), 543–549. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1023767

- Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2001). Influences on loneliness in older adults: A meta-analysis. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 23(4), 245–266. doi:https://doi.org/10.1207/153248301753225702

- Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2003). Risk factors for loneliness in adulthood and old age: A meta-analysis. Advances in Psychology Research, 19(3), 111–143.

- Pronk, M., Deeg, D. J. H., Smits, C., Twisk, J. W., van Tilburg, T. G., Festen, J. M., & Kramer, S. E. (2014). Hearing loss in older persons: Does the rate of decline affect psychosocial health? Journal of Aging and Health, 26(5), 703–723. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264314529329

- Pronk, M., Deeg, D. J. H., Smits, C., van Tilburg, T. G., Kuik, D. J., Festen, J. M., & Kramer, S. E. (2011). Prospective effects of hearing status on loneliness and depression in older persons: Identification of subgroups. International Journal of Audiology, 50(12), 887–896. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/14992027.2011.599871

- Rico-Uribe, L. A., Caballero, F. F., Martin-Maria, N., Cabello, M., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., & Miret, M. (2018). Association of loneliness with all-cause mortality: A meta-analysis. Plos One, 13(1), e0190033. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0190033

- Rius-Ottenheim, N., Kromhout, D., van der Mast, R. C., Zitman, F. G., Geleijnse, J. M., & Giltay, E. J. (2012). Dispositional optimism and loneliness in older men. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(2), 151–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2701

- Routasalo, P., & Pitkala, K. H. (2003). Loneliness among older people. Reviews in Clinical Gerontology, 13(4), 303–311. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S095925980400111X

- Rouxel, P., Heilmann, A., Demakakos, P., Aida, J., Tsakos, G., & Watt, R. G. (2017). Oral health-related quality of life and loneliness among older adults. European Journal of Ageing, 14(2), 101–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-016-0392-1

- SBU. (2014). Utvärdering av metoder i hälso- och sjukvården [Assessment of methods in health care]. Stockholm: Swedish Agency for Health Technology Assessment and Assessment of Social Services.

- Steptoe, A., Breeze, E., Banks, J., & Nazroo, J. (2013). Cohort profile: The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(6), 1640–1648. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys168

- Sutin, A. R., Stephan, Y., Carretta, H., & Terracciano, A. (2015). Perceived discrimination and physical, cognitive, and emotional health in older adulthood. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry : official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(2), 171–179. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2014.03.007

- Taekema, D. G., Gussekloo, J., Maier, A. B., Westendorp, R. G. J., & de Craen, A. J. M. (2010). Handgrip strength as a predictor of functional, psychological and social health. A prospective population-based study among the oldest old. Age and Ageing, 39(3), 331–337. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afq022

- Taube, E., Kristensson, J., Midlöv, P., Holst, G., & Jakobsson, U. (2013). Loneliness among older people. Results from the Swedish National Study on Aging and Care – Blekinge. The Open Geriatric Medicine Journal, 6(1), 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.2174/1874827901306010001

- Tesch-Römer, C., & Huxhold, O. (2019). Social isolation and loneliness in old age. Oxford Research Encyclopedias. Subject: Developmental Psychology.

- Tijhuis, M. A. R., de Jong Gierveld, J., Feskens, E. J. M., & Kromhout, D. (1999). Changes in and factors related to loneliness in older men. The Zutphen Elderly Study. Age and Ageing, 28(5), 491–495. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/28.5.491

- van Baarsen, B. (2002). Theories on coping with loss: The impact of social support and self-esteem on adjustment to emotional and social loneliness following a partner's death in later life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 57(1), S33–S42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/57.1.s33

- Warner, D. F., & Adams, S. A. (2016). Physical disability and increased loneliness among married older adults: The role of changing social relations. Society and Mental Health, 6(2), 106–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2156869315616257

- Weiss, R. S. (1973). Loneliness: the experience of emotional and social isolation. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Verbakel, E., Tamlagsrønning, S., Winstone, L., Fjaer, E. L., & Eikemo, T. A. (2017). Informal care in Europe: Findings from the European Social Survey (2014) special module on the social determinants of health. European Journal of Public Health, 27(suppl_1), 90–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw229

- Victor, C. R., Mansfield, L., Kay, T., Daykin, N., Lane, J., L., G. D., … Meads, C. (2018). An overview of reviews: The effectiveness of interventions to address loneliness at all stages of the life-course. Retrieved from https://whatworkswellbeing.org/resources/tackling-loneliness-review-of-reviews/.

- Victor, C. R., Rippon, I., Quinn, C., Nelis, S. M., Martyr, A., Hart, N., … Team, I. P. (in press). The prevalence and predictors of loneliness in caregivers of people with dementia: Findings from the IDEAL programme. Aging & Mental Health. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1753014

- Wong, J. S., & Waite, L. J. (2017). Elder mistreatment predicts later physical and psychological health: Results from a national longitudinal study. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 29(1), 15–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2016.1235521

- Yang, K. M. (2018). Longitudinal loneliness and its risk factors among older people in England. Canadian Journal on Aging = La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement, 37(1), 12–21. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s0714980817000526