Abstract

Objectives

Discordance between self-reported functional limitations and performance-based physical functioning may have a negative impact in functional independence in older adults. We longitudinally examined baseline apathy- and depressive symptomatology as associates of discordance.

Method

469 participants from the multi-site cohort study NESDO were included. Self-reported functional limitations were assessed by two items derived from the WHO-Disability Assessment Schedule. Performance-based physical functioning included walking speed and handgrip-strength. Both measures were rescaled, with final sum-scores ranging from 0 to 6. Discordance-scores were computed by subtracting sum-scores on performance-based measures from self-reported functional limitations. Using latent growth curve analysis, we estimated individual trajectories of discordance at baseline, 2-and 6-years follow-up, consisting of the baseline discordance-score (intercept) and the yearly change of discordance-score (slope). We then estimated associations with apathy and depression indicators.

Results

At baseline, persons (mean age 70.48 years, 65% female, 73% depressed) on average overestimated their daily functioning compared to performance tests (b = 0.77, p < 0.001). The average discordance-scores yearly increased by 0.15 (p < 0.001). Only in models adjusted for several demographic and clinical characteristics, depression severity was negatively associated with discordance-scores at baseline (b=−0.01, p = 0.02), while apathy was not (b=−0.02, p = 0.21). No associations with change over time were found.

Conclusion

In older persons, not indifference and diminished goal-directed activity, but negative emotions appear to underlie underestimation of one’s physical capacity. Further research is needed to determine (1) to what extent targeting discordance results in actual preservation of physical functioning and (2) whether older persons with apathy and/or depression need different approaches for this purpose.

Introduction

Both from older adults’ own perspective as from a public health perspective, retaining physical functioning is an important aim. However, there are several ways in which physical functioning can be assessed, and it has been shown that there can be substantial discordance between, for example, performance-based and self-reported levels of functioning (Brach et al., Citation2002; Daltroy et al., Citation1999; Kempen et al., Citation1996; Kok et al., Citation2020). Discordance of physical functioning means that an individual’s self-assessed level of physical functioning differs from level of performance on physical tests. When older adults experience more limitations than objectively measured with performance tests, the literature typically refers to this as “underestimation” of physical functioning, whereas the opposite is referred to as “overestimation.” Both modes of discordance may be considered as disadvantageous phenomena, as they may both result in loss of independence. For example, overestimation of physical functioning may lead to higher risk of falls and (fall-related) injuries (Delbaere et al., Citation2010; Sakurai et al., Citation2013), which consequently may result in additional functional decline (Gill et al., Citation2013; Tinetti and Williams, Citation1998). Vice versa, underestimation of physical functioning may result in suboptimal utilization of one’s physical potential and, therewith, in (potential preventable) loss of physical functioning and independence. Therefore, identification and knowledge of predictors or correlates of discordance is of great importance. Literature has already indicated several factors related to under- and overestimation in older persons living in the community. For example, male gender and increasing age have been associated with overestimation (Kok et al., Citation2020; Wloch, Citation2016). Female gender (Daltroy et al., Citation1999; Kok et al., Citation2020; Merrill et al., Citation1997), more pain (Daltroy et al., Citation1999; Kok et al., Citation2020) and lower self-rated health (Kok et al., Citation2020) or less perceived physical competence (Kempen et al., Citation1996) have been associated with underestimation.

Despite its high prevalence in older persons (Henstra et al., Citation2019; van der Mast et al., Citation2008), apathy has not yet been explored as a potential correlate of discordance. Apathy is defined as a quantitative reduction of goal-directed activity in at least two of the three apathy dimensions (behavior/cognition; emotion and social interaction) (Robert et al., Citation2018). Although apathy is a distinct clinically relevant syndrome that can be present without an underlying condition (Brodaty et al., Citation2010; Kawagoe et al., Citation2017), it is mostly described as a symptom of neurodegenerative, cerebrovascular and psychiatric diseases (Marin, Citation1991). Two recent longitudinal studies provide a rationale for further exploration of the role of apathy in the underestimation of capacity of physical functioning. First, a recent population-based study in non-demented older persons using data of two ongoing cohort studies (LonGenity (Ayers et al., Citation2014) and Central Control of Mobility in Aging [CCMA (Holtzer et al., Citation2014)]) it was demonstrated that independent of depressive symptoms, apathy was more strongly associated with self-reported disability than with performance-based physical decline at follow up (Ayers et al., Citation2017). Second, we previously demonstrated similar results, using data from the Netherlands Study of Depression in Older persons (NESDO)-cohort; in older persons without dementia, apathy was associated with decline of self-reported physical functioning but not with decline in performance-based tests after two years, irrespective of the presence of depression (Henstra et al., Citation2018). These results imply that reduced goal-directed activity (apathy) has a stronger negative impact on self-reported than performance-based measures of functional status. Therefore, an association between apathy and discordance (or more specific, underestimation) of capacity of physical functioning is plausible but not yet empirically investigated.

Studies so far suggest that when exploring apathy as an associate of discordance of physical functioning, it is important to consider depressive symptomatology. This is because in old age, symptoms of apathy can be present without depression, but vice versa, depression is often accompanied by apathy. Nevertheless, for over twenty years, apathy and depression have been considered as separate constructs that may have different courses requiring different approaches (Levy et al., Citation1998; Yuen et al., Citation2015). Evidence on the effect of depression on discordance is mixed. Some studies found cross-sectional associations of depression with underestimation (Daltroy et al., Citation1999; Kempen et al., Citation1996; Citation1996), but in two large Dutch population-based prospective studies depression was not independently associated with discordance (Kempen et al., Citation1999; Kok et al., Citation2020).

In sum, with regard to associations between apathy, depression and discordance, several uncertainties exist. It is unknown whether apathy relates to discordance and evidence on the association between depression and discordance is inconsistent. Furthermore, it is unknown to what extent associations between apathy and depression and discordance are independent of each other.

Therefore, the current study has several aims. 1) We calculate individual trajectories of discordance between self-reported and performance-based measures of physical functioning across three waves (baseline, two and six years of follow-up) and examine correlates of discordance. 2) We separately examine baseline symptoms of apathy and severity of depression as associates of both discordance at baseline and change of discordance over time in multivariable models. We hypothesize that apathetic symptoms are more strongly associated with underestimation of physical capacity compared to severity of depressive symptoms due to the core symptom of apathy: reduced goal-directed activity. More detailed knowledge on the separate roles of apathy and depression on discordance of measures of physical functioning may help clinicians to apply tailor-made interventions to postpone functional decline in older persons.

Methods

Study sample

We used data from participants of the Netherlands Study of Depression in Older persons (NESDO), a longitudinal, multisite, naturalistic cohort study that included 378 older adults with a depressive disorder at baseline (in the past 6-months) and 132 non-depressed controls with no diagnosis of depression during their lifetime (Comijs et al., Citation2011). The cohort of depressed older people (60 years and older) was recruited, between 2007 and 2010, from specialized mental health services and general practitioners, in five regions throughout the Netherlands. Late-life depression at various developmental and severity stages were present in the sample. Exclusion criteria were a diagnosis of dementia or a suspected dementia according to the clinician, baseline Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score below 18, having another primary severe psychiatric disorder, or insufficient command of the Dutch language. Non-depressed controls were recruited from general practitioners, using similar criteria. A face-to-face assessment was performed at baseline and after 2- and 6-years follow-up. All participants gave verbal and written informed consent before enrolment, and the Ethical Review Board of the VU University Medical Center, the Leiden University Medical Center, University Medical Center Groningen, and the Radboud University Medical Center in Nijmegen granted ethical approval. The procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committees and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 1983. A more detailed description of NESDO is given elsewhere (Comijs et al., Citation2011).

Measurements

Assessment of self-reported physical functioning

Self-reported physical functioning were assessed with the WHO-Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO-DASII) (Chwastiak and Von Korff, Citation2003). The WHO-DASII is a general disability instrument that examines difficulties in six domains of life during the last 30 days. To assess discordance, it is important that the operationalization of both subjective and objective physical functioning are matched as much as possible. Therefore, we selected the two WHO-DAS domains focusing on (i) ADL activities and mobility, namely self-care (four questions) and physical mobility (five questions, supplementary material). Answer categories ranged from 0 (extreme/cannot do) to 5 (no difficulties) and were summed to form a scale ranging from 0 to 45. Higher scores reflect better self-reported functioning. We rescaled this to a range of 0–6, to match the range of the performance-based physical functioning measure.

Assessment of performance-based physical functioning

In order to incorporate both upper and lower extremity functions, we created a performance score existing of walking speed and handgrip strength. Walking speed was assessed by timing a 6-meter walk. Participants were instructed to walk at usual pace and from a standing start as if they were walking down the street, and given no further encouragement or instruction (Studenski et al., Citation2011). Results are expressed in meters/seconds (ms). Handgrip strength, measured in kilograms (kg), was assessed by means of a hand-held dynamometer. Participants were asked to squeeze the dynamometer twice with their dominant hand in a standing position (Chung et al., Citation2014). For our analyses, the average of these two measurements was used (Henstra et al., Citation2018; Citation2019). In order to combine the two performance-based tests, we divided the scores of both measures into quartiles and assigned a score of zero to the lowest functioning quartile, and a score of three to the highest functioning quartile. For handgrip strength, we calculated quartiles for men and women separately. We then summed scores of both measures, resulting in a range of 0–6.

Assessment of discordance

To assess discordance, we calculated discordance-scores by subtracting scores on performance-based physical functioning from scores on self-reported measures of physical functioning at each wave. Positive discordance-scores imply overestimation and negative discordance-scores imply underestimation.

Assessment of predictors

Apathy symptoms

Symptoms of apathy were assessed at baseline by means of the 14-item Apathy Scale (Dutch version (Lampe et al., Citation2001)), which is an abbreviated version of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. This scale was shown to discriminate between patients with stroke, Alzheimer disease and depression versus healthy older control patients, according to mean levels of apathy, with good reliability and validity (Marin et al., Citation1991). Higher scores on the Apathy Scale, up to a maximum of 42 points, are indicative of more severe apathy.

The optimal cut-off value of 14 is used most often, and previously showed a 66% sensitivity and a 100% specificity for the presence of clinically relevant apathy in patients with Parkinson’s Disease.

Depressive symptoms

Severity of depression was measured at baseline using the Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (IDS, Dutch translation: Altrecht GGZ. Copyright© 1995/2005), which is a self-report 30-item questionnaire on the severity and frequency of specific symptoms present over the last 7 days (Rush et al., Citation1996). All answer items are scored on a scale between 0 and 3. Higher scores on the IDS, up to a maximum of 84 points, are indicative of more severe depression. In international research a score <14 is used as a measure of remission of depression (Meesters et al., Citation2016). In the manuscript, we will further use the term ‘IDS-score’ when referring to severity of depressive symptoms.

Depression patterns

We also determined the association between two different patterns of depression. Pattern 1 was defined as presence of a depressive disorder at baseline or after two years. Pattern 2 was defined as the presence of a depressive disorder at baseline and after two years. Depression was defined as at least one of the following conditions: major depression, dysthymia in the past 6 months or minor depression in the past month according to DSM-IV criteria (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2000). It was assessed with a structured clinical interview that is designed for use in research settings with high validity for depressive disorders (Composite International Diagnostic Interview; CIDI; WHO version 2.1; life-time version) (Kessler et al., Citation2010; Wittchen et al., Citation1991).

Covariates

Socio-demographics, neuropsychiatric characteristics, physical health and lifestyle characteristics were included at baseline and were selected based on the existing literature and clinical rationale (Kok et al., Citation2020). Socio-demographics included age, gender, current partner status (yes/no) and years of education. Neuropsychiatric characteristics included global cognitive functioning. To assess cognitive performance the Mini Mental State Examination-score (MMSE) score was used. Physical health and lifestyle characteristics included physical activity, alcohol consumption, Body Mass Index (BMI), the number of chronic diseases, cardiovascular disease risk, use of psychotropic drugs (yes/no), and the presence of disabling pain. The International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) was used to measure physical activity as part of daily, work and leisure time activities. Results are presented in ratio of energy expenditure during activity compared to rest, times the number of minutes performing the activity per week in metabolic equivalent minutes (MET-minutes) (Craig et al., Citation2003). For practical reasons, we recalculated this variable into Meth/day. In older adults, the IPAQ is a validated questionnaire for assessing physical activity (Tomioka et al., Citation2011). Alcohol consumption was assessed by the AUDIT questionnaire (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) in units per week (low [<1 for men and women], moderate [1–14 for women, 1–21 for men], and high [>14 for women, >21 for men]) (Babor et al., Citation1989). BMI was measured using anthropometry. The number of chronic diseases (0–8) was assessed by means of a self-report questionnaire that has previously been used in the Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA) (Penninx et al., Citation2008). The participants were asked whether they currently or previously had been diagnosed with any of the following chronic diseases or disease events: cardiac disease (e.g. myocardial infarction), peripheral atherosclerosis, stroke, diabetes mellitus, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD i.e. asthma, chronic bronchitis or pulmonary emphysema), arthritis (rheumatoid arthritis or osteoarthritis), cancer or any other disease. To further determine cardiovascular disease burden in our population, we computed an incident 5-year absolute cardiovascular risk score derived from the Dubbo-study (Simons et al., Citation2011). This study was designed to identify predictors of long-term all-cause mortality in Australian senior citizens. To account for medication effects, we also included use of psychotropics as covariates (Yes/No). Use of psychotropics was assessed at baseline by registration of the medication participants brought in and was coded using the Anatomic Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. Pain was assessed using Chronic Graded Pain Scale-Dutch (CGPS), a self-report questionnaire that scores both pain intensity and disability due to pain (Von Korff et al., Citation1992). The CGPS has a range between 0 and 100, with higher scores indicating more intense or disabling pain. It was categorized into 5 grades ranging from pain free (grade 0) to high disability with severe limiting (grade 4).

Analytic procedure

First, we calculated Pearsons’ correlations between self-reported and performance-based measures of physical functioning for each wave, and for apathy-scores and IDS-scores at baseline. We then investigated potential multicollinearity between apathy-scores and IDS-scores. The variance inflation factor (VIF) score was 1.0, indicating there was no multicollinearity between the two variables. Using latent growth modelling (LGM) in Mplus v7 (Muthén and Muthén, Citation2012), we calculated individual trajectories based on the three discordance-scores at each wave (baseline, two and six years), consisting of an ‘intercept’ (i.e. baseline value of the discordance-score) and ‘slope’ (i.e. the yearly change of the discordance-score) parameter. We estimated models with linear and quadratic slopes and then selected the model with the best fit, using the sample-size adjusted Bayesian Information Criterion (SSA-BIC) (Neath and Cavanaugh, Citation2012). Then, we estimated the association between baseline apathy-scores and IDS-scores and discordance in several steps. First, we estimated apathy symptoms and IDS-scores as separate predictors of the intercept and slope. Second, we estimated a model with both IDS-scores and apathy-scores in the model. Third, we examined which covariates were significantly (p<.05) associated with apathy-scores, IDS-scores and with the discordance intercept and/or slope, and added these to the model in a stepwise fashion: first demographic characteristics (age, gender, partner status, education) and then the other covariates. As secondary predictors, we applied these procedures again to examine associations between the course of depression (based on CIDI-derived diagnoses) and discordance. Finally, as in our study sample the majority had a depressive disorder, we calculated individual trajectories thereby stratifying for depression. We also examined correlates of discordance stratified for depression (bivariable models only, post-hoc analyses). In all analyses, missing data on covariates was handled by Full Information Maximum Likelihood procedures. P-values of <0.05 were considered significant.

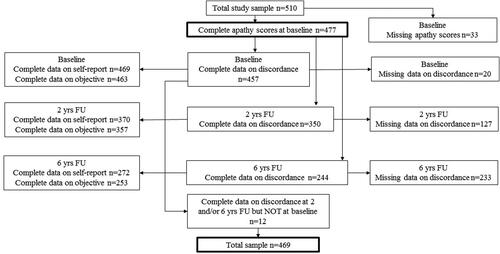

Results

At baseline, 33 persons had missing data on apathy-scores. Of the remaining 477 persons, 457 persons had complete data on both self-reported and performance-based measures of physical functioning at baseline. Twelve persons had complete data on both measures for at least one follow-up wave, yielding 469 persons for our analyses (n = 343 depressed; n = 126 healthy controls). Of the 457 persons with a discordance-score at baseline, 244 had a discordance-score at six years follow up (no discordance-score at six years follow up n = 213, (47%) (). Main reason for the absence of discordance-score at the end of the study was drop-out from the study (n = 184 (86%). Main reasons for drop-out were: deceased (34%), refusal for various reasons (21%) and unable for various reasons (43%). Compared to persons with a discordance-score at the end of the study, persons without discordance-score were significantly older (72.9 vs. 68.3 years), lower educated (10.4 vs. 11.5 years), had higher baseline discordance-scores (1.1 vs. 0.5), had more apathy (16.7 vs. 13.9) and worse depression symptoms (26.8 vs. 10.8) and lower MMSE-scores (27.5 vs. 28.4). They also had lower physical activity (5.4 vs. 7.0), higher cardiovascular risk (6.5 vs. 5.7) and higher pain scores (1.8 vs. 1.6).

Baseline characteristics of all variables are depicted in . At baseline, mean age was 70.48 years (SD 7.24) and 65% were women. Mean apathy-score was 15.28 (SD 6.2) and mean IDS-score was 23.78 (SD 15.10). Of the 343 depressed persons, 326 (95%) had a major depressive disorder in the past 6 months, of which 91 combined with dysthymia. 17 persons had a minor depression of which 1 also suffered from dysthymia in the past 6 months. The mean discordance-score at baseline was 0.78 (SD 1.76) (). Correlations between self-reported and performance-based measures of physical functioning at baseline, two and six years were 0.38, 0.49 and 0.37 respectively. Correlation between baseline apathy-scores and IDS-scores was 0.57 (all p-values<.001).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics.

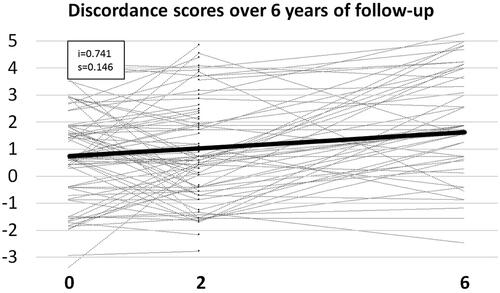

Trajectories of discordance-scores across three waves

shows the estimated mean and individual trajectories of discordance based on individual discordance-scores across three waves. A model with a linear slope had the best fit; adding a quadratic slope did not improve the model. Therefore, we assumed a linear growth curve for all respondents, which was in addition to statistical fit indicators also supported by visually inspecting random subsets of individual observed trajectories; these showed largely linear changes over time. On average, at baseline persons had positive discordance-scores (intercept = 0.77, p < 0.001) and discordance-scores increased by 0.15 per year (slope = 0.146, p < 0.001). Variance of the intercept was significant (variance = 1.729, p < 0.001), indicating that persons differed substantially in the degree of discordance at baseline. However, the variance of the linear slope was non-significant (variance = 0.013, p = 0.5), indicating that persons did not significantly differ in the degree of increase of discordance across follow-up.

Correlates of discordance: bivariable analyses

In the bivariable analyses neither baseline apathy symptoms nor severity of depressive symptoms at baseline were associated with discordance at baseline (b = 0.009, p = 0.51 and b= −0.006, p = 0.27, respectively). However, the association between IDS-scores and discordance at baseline was marginally significantly negative after adjustment for apathy symptoms (b=−0.012, p = 0.076). Apathy- and IDS-scores at baseline were not associated with change of discordance-scores over time (slope −0.002, p = 0.60 and slope 0,000, p = 0.94 respectively) ().

Table 2. Bivariable latent growth models for the association with discordance-score at baseline (intercept) and change of discordance-scores over time (slope).

Higher age, female gender, not having a partner, lower levels of education, lower MMSE-score, lower levels of physical activity and higher cardiovascular risk were associated with more positive discordance-scores at baseline. Only physical activity was significantly associated with the slope of discordance; higher physical activity was associated with a stronger increase of discordance-scores over time (Supplemenary ). These covariates were selected for our multivariable analyses.

Associates of discordance: multivariable analyses

For apathy symptoms, no significant associations with discordance-score or change of discordance-score over time were present after adding the significant covariates from the bivariate analyses to the model (b=−0.016, p = 0.21 and slope 0.000 and p = 0.95). However, the association between IDS-scores and discordance-score was significant in the multivariable analysis excluding apathy (b=-0.012, p = 0.023) and after additional adjustment for apathy symptoms (b=−0.011, p = 0.05). We found no associations between apathy or depression with change of discordance ().

Table 3. Multivariable Latent Growth Models for the association with discordance-score at baseline (intercept) and yearly change of discordance-scores (slope).

Depression patterns and discordance

Depression at only one time point (thus at baseline or after 2 years) was neither associated with discordance at baseline not with the slope. For both patterns of depression, the association with the slope was not significant in all models. Only in the multivariable models chronic depression was significantly negatively associated with discordance at baseline (b=−0.429, p = 0.028) but not with change over time.

Post-hoc analysis: suppression of the effect of depression

The finding that associations between IDS-scores and chronic depression with discordance became significant only after adjustment for covariates, indicated suppression effects of these covariates. In a post-hoc analysis to determine the relative strength of these effects between covariates, we added each covariate separately to the model with IDS-scores and chronic depression and calculated the change in effect on the intercept. We found that level of education, MMSE-score and partner status were responsible for the largest part of the suppression-effect (data not shown).

Post-hoc analysis: trajectories and correlates of discordance stratified for depression at baseline (bivariable analyses only)

At baseline both depressed and non-depressed persons had positive discordance-scores (intercept = 0.71, p < 0.001 and intercept 0.77, p < 0.001 respectively) and discordance-scores yearly increased in both groups (depressed: slope= 0.133, p < 0.001, non-depressed slope 0.170, p < 0.001). In the depressed, higher age, lower levels of education, lower levels of cognitive functioning and lower levels of physical activity associated with higher discordance-scores. In the non-depressed, higher age, not having a partner, lower levels of cognitive functioning and lower levels of physical activity associated with higher discordance-scores.

In both groups, neither baseline apathy symptoms nor severity of depressive symptoms at baseline were associated with discordance at baseline. Apathy- and IDS-scores at baseline were not associated with change of discordance-scores over time in both groups (Supplemenary material ).

Discussion

In a Dutch sample of depressed and non-depressed older persons, we found that on average, older persons overestimate their level of physical functioning, and the extent of overestimation significantly increased over the course of six years. Our hypotheses regarding the associations between apathy and depression with this discordance were partly supported: indeed, apathy and depression appear to play different roles in discordance, although not in the way that we expected. Not symptoms of apathy, but depression severity and chronic depression were associated with more negative discordance-scores, that is underestimation. Furthermore, these effects were observed only after taking into account particular characteristics of depressed older persons, particularly their lower educational level, higher likelihood of living alone, and lower cognitive functioning. Neither apathy symptoms, nor depression severity were associated with the course of discordance in our study.

We expected both positive mean discordance-scores at baseline and increase of discordance-scores over time in our study as increasing age has previously been associated with overestimation in several studies (Kok et al., Citation2020; Sakurai et al., Citation2013; Wloch, Citation2016). It has been suggested that overestimation may at least partly reflect normal aging rather than a pathological process, as objective measures of physical functioning may be capable of detecting functional decline that is still unnoticeable for respondents (Guralnik et al., Citation1989; Kok et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, overestimation may also reflect an adaptation process (Glass, Citation1998). That is, older adults might consider difficultness in daily tasks as a part of normal aging and therefore report no difficulties even if they use material or personal aids when executing specific tasks (Feuering et al., Citation2014). Nevertheless, we expected that apathy and depression symptoms would affect these processes.

However, we found no evidence that apathy is associated with discordance. This implies that underestimation is not driven by the diminished ability to achieve goal directed activity in multiple apathy dimensions (behavior/cognition; emotion and social interaction). Interestingly, there was a trend for the association between IDS-scores and discordance at baseline adjusted for apathy symptoms and in our fully adjusted models IDS-scores associated with a negative discordance-score. This substantiates that in old age, despite their overlap in symptomatology, apathy and depression have different roles in discordance. Namely, apathy and depression differ in experienced emotions varying from indifference and emotional neutrality (apathy) to negative thoughts and feelings (depression). Thus, presumably not indifference but negative thoughts and feelings are underlying underestimation. Other affective characteristics associated with negative thoughts such lower self-rated health (Kok et al., Citation2020), less perceived physical competence (Kempen et al., Citation1996), and anxiety (Kempen et al., Citation1996) have been also associated with underestimation, strengthening this line of thought. As our results were contrary to our expectations, we decided to further explore the course of depression on discordance. It appeared that older persons with persistent depression, and therewith persistent negative affective characteristics, are more likely to underestimate their capacity of physical functioning at baseline compared to depression at one time point. This in line with the scarce literature, although with different methodology: in a large British cohort study, chronic depression but not depression at baseline was associated with underestimation of physical functioning at follow-up (PhD thesis, chapter 7 (Wloch, Citation2016)).

The finding that the association between severity of depressive symptomatology and negative discordance-scores at baseline was significantly only after adjustment for covariates suggests that depression in old age in itself may result in underestimation. However, patient characteristics such as not having a partner, lower cognitive function and lower levels of education appear cancel out the negative effect of depressive symptoms on discordance as these factors (all known associates of depression) were associated with overestimation in our study. However, as this suppressive effect was not present for apathy, we still consider our findings relevant. Namely, these show that even in a cohort of mainly severe depressed older persons, with regard to discordance between measures of physical functioning, apathy and depression are not interchangeable conditions. One can argue whether our findings support the theory of depressive realism (Haaga and Beck, Citation1995). This theory suggests that persons with a depression may be more accurate in estimating their level of functioning compared to non-depressed persons who tend to overestimate their level of functioning. Although indeed (some) overestimation may at least partly reflect normal aging rather than a pathological process, it is in our opinion unlikely that in old age the presence of a depression is beneficial for more accurate use of physical capacity. On the other hand, in clinical practice, therapists and clinicians often automatically assume that depressed persons are not motivated to be active. However, our results suggest that depressed older persons are capable of adequately assessing their capacity of physical functioning and that clinicians should value the opinion of their depressed older patients with regard to their physical capacity. Next, theoretically it is conceivable that especially in persons with severe self-overestimation, co-existence of depression may result in a more realistic estimation of physical capacity.

Our study has several strengths and limitations. Strengths of this study are the longitudinal data from a well-designed large population-based sample of older adults and inclusion of a broad range of psychosocial and health-related factors. Next, despite the high rate of missing of discordance-score at the end of follow-up (47%), we think we limited the potential impact of attrition by handling missing data by Full Information Maximum Likelihood procedures (FIML). Namely, currently, FIML has been shown to be the best statistical method to reduce such bias, outperforming methods such as complete case analysis, weighted least squares with mean and variance adjustment and pairwise deletion. Second, despite the fact that persons without discordance-score at end of follow-up had higher baseline discordance-scores, higher age, lower education and MMSE-scores (all associated with higher discordance-scores), in our study participants still (increasingly) overestimated their functional capacity. Several limitations must be addressed. The majority of the participants had a major depression, raising questions on the generalizability of our results to the general older population. Next, to our knowledge, only one large Dutch population-based previously examined correlates of discordance between self-reported functional limitations and performance-based physical functioning, although with different methodology (Kok et al., Citation2020). Only for age and cognitive functioning we found similar results, but not for the other significant covariates (i.e. gender, level of education, partner status and physical activity). In our post-hoc analyses we found no additional significant correlates of discordance in either group after stratification for depression. This indicates that, the inconsistencies between our and the aforementioned study (Kok et al., Citation2020) are not (fully) explained by the high prevalence of (severe) depression in our study sample. Next, one could state that the high correlation between apathy- and depression severity (Pearsons’ correlation 0.57 (p-values < 0.0001) complicated our attempt to separately analyze apathy and depression as associates. However, valid assessments of both apathy and depression were performed to answer our research questions, which were both provided in the NESDO-cohort. Finally, as the NSEDO-study only provided data on two physical performance tests, our assessment of performance-based physical functioning may be considered somewhat limited.

Conclusion

With increasing age, older persons tend to overestimate their level of physical functioning and the extent of overestimation increases over time. Not apathetic symptoms defined as the inability to achieve goal directed behavior, but depression severity appeared to associate with underestimation, after adjustment for several demographic and clinical characteristics. However, in daily practice, not having a partner, lower cognitive function and lower levels of education may cancel out the negative effect of depressive symptoms on discordance as these factors (all known associates of depression) associated with overestimation in our study. Therefore, in clinical practice, neither apathy nor depression appear to be fruitful targets for improving underestimation between self-reported and performance-based measures of physical functioning. Nevertheless, our study provides more understanding to what extent experienced emotions, that is indifference versus negative affective symptoms, have different relationships with experienced physical functioning. Further research is needed to determine 1) to what extent targeting discordance results in actual preservation of physical functioning and 2) whether older persons with apathy and/or depression need different approaches for this purpose.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (21.4 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington: American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Ayers, E., Barzilai, N., Crandall, J. P., Milman, S., & Verghese, J. (2014). Association of exceptional parental longevity and physical function in aging. AGE, 36(4), 1–7. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-014-9677-5

- Ayers, E., Shapiro, M., Holtzer, R., Barzilai, N., Milman, S., & Verghese, J. (2017). Symptoms of apathy independently predict incident frailty and disability in community-dwelling older adults. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 78(5), e529–e536. doi:https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.15m10113

- Babor, T. F., Kranzler, H. R., & Lauerman, R. J. (1989). Early detection of harmful alcohol consumption: Comparison of clinical, laboratory, and self-report screening procedures. Addictive Behaviors, 14(2), 139–157. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0306-4603(89)90043-9

- Brach, J. S., VanSwearingen, J. M., Newman, A. B., & Kriska, A. M. (2002). Identifying early decline of physical function in community-dwelling older women: Performance-based and self-report measures. Physical Therapy, 82(4), 320–328.

- Brodaty, H., Altendorf, A., Withall, A., & Sachdev, P. (2010). Do people become more apathetic as they grow older? A longitudinal study in healthy individuals. International Psychogeriatrics, 22(3), 426. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610209991335

- Chung, C. J., Wu, C., Jones, M., Kato, T. S., Dam, T. T., Givens, R. C., Templeton, D. L., Maurer, M. S., Naka, Y., Takayama, H., Mancini, D. M., & Schulze, P. C. (2014). Reduced handgrip strength as a marker of frailty predicts clinical outcomes in patients with heart failure undergoing ventricular assist device placement. Journal of Cardiac Failure, 20(5), 310–315. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2014.02.008

- Chwastiak, L. A., & Von Korff, M. (2003). Disability in depression and back pain: Evaluation of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO DAS II) in. a Primary Care Setting. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 56(6), 507–514. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00051-9

- Comijs, H. C., van Marwijk, H. W., van der Mast, R. C., et al. (2011). The Netherlands study of depression in older persons (NESDO); a prospective cohort study. BMC Research Notes, 4, 524. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-4-524

- Craig, C. L., Marshall, A. L., Sjostrom, M., Bauman, A. E., Booth, M. L., Ainsworth, B. E., Pratt, M., Ekelund, U., Yngve, A., Sallis, J. F., & Oja, P.(2003). International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, 35(8), 1381–1395.

- Daltroy, L. H., Larson, M. G., Eaton, H. M., Phillips, C. B., & Liang, M. H. (1999). Discrepancies between self-reported and observed physical function in the elderly: The influence of response shift and other factors. Social Science & Medicine, 48(11), 1549–1561. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00048-9

- Delbaere, K., Close, J. C. T., Brodaty, H., Sachdev, P., & Lord, S. R. (2010). Determinants of disparities between perceived and physiological risk of falling among elderly people: Cohort study. BMJ, 341, c4165. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4165

- Feuering, R., Vered, E., Kushnir, T., Jette, A. M., & Melzer, I. (2014). Differences between self-reported and observed physical functioning in independent older adults. Disability and Rehabilitation, 36(17), 1395–1401. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2013.828786

- Gill, T. M., Murphy, T. E., Gahbauer, E. A., & Allore, H. G. (2013). Association of injurious falls with disability outcomes and nursing home admissions in community-living older persons. American Journal of Epidemiology, 178(3), 418–425. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kws554

- Glass, T. A. (1998). Conjugating the “tenses” of function: Discordance among hypothetical, experimental, and enacted function in older adults. The Gerontologist, 38(1), 101–112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/38.1.101

- Guralnik, J. M., Branch, L. G., Cummings, S. R., & Curb, J. D. (1989). Physical performance-measures in aging research. The Journals of Gerontology, 44(5), M141–M146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/44.5.m141

- Haaga, D. A., & Beck, A. T. (1995). Perspectives on depressive realism: Implications for cognitive theory of depression. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(1), 41–48. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)E0016-C

- Henstra, M. J., Feenstra, T. C., van der Velde, N., van der Mast, R. C., Comijs, H., Stek, M. L., & Rhebergen, D. (2018). Apathy is associated with greater decline in subjective, but not in objective measures of physical functioning in older people without dementia. The Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 74(2), 254–260.

- Henstra, M. J., Rhebergen, D., & Stek, M. L. (2019). The association between apathy, decline in physical performance, and falls in older persons. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 31(10), 1491–1499. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-018-1096-5

- Holtzer, R., Wang, C., & Verghese, J. (2014). Performance variance on walking while talking tasks: Theory, findings, and clinical implications. AGE, 36(1), 373–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-013-9570-7

- Kawagoe, T., Onoda, K., & Yamaguchi, S. (2017). Apathy and executive function in healthy elderly-resting state fMRI study. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 9, 124–124.

- Kempen, G. I. J. M., Sullivan, M., Sonderen, E., & Ormel, J. (1999). Performance-based and self-reported physical functioning in low-functioning older persons: Congruence of change and the impact of depressive symptoms. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 54B(6), P380–P386. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/54B.6.P380

- Kempen, G. I., Steverink, N., Ormel, J., & Deeg, D. J. (1996). The assessment of ADL among frail elderly in an interview survey: Self-report versus performance-based tests and determinants of discrepancies. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 51(5), P254–P260. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/51b.5.p254

- Kempen, G. I., van Heuvelen, M. J., van den Brink, R. H., Kooijman, A. C., Klein, M., Houx, P. J., & Ormel, J. (1996). Factors affecting contrasting results between self-reported and performance-based levels of physical limitations. Age and Ageing, 25(6), 458–464. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/25.6.458

- Kessler, R. C., Birnbaum, H., Bromet, E., Hwang, I., Sampson, N., & Shahly, V. (2010). Age differences in major depression: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Psychological Medicine, 40(2), 225–237. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709990213

- Kok, A. A. L., Henstra, M. J., van der Velde, N., Rhebergen, D., & van Schoor, N. M. (2020). Psychosocial and health-related factors associated with discordance between 13-year trajectories of self-reported functional limitations and performance-based physical functioning in old age. Journal of Aging and Health, 32(9), 1084–1097. 898264319884404. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264319884404

- Lampe, I. K., Kahn, R. S., & Heeren, T. J. (2001). Apathy, anhedonia, and psychomotor retardation in elderly psychiatric patients and healthy elderly individuals. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 14(1), 11–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/089198870101400104

- Levy, M. L., Cummings, J. L., Fairbanks, L. A., Masterman, D., Miller, B. L., Craig, A. H., Paulsen, J. S., & Litvan, I. (1998). Apathy is not depression. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 10(3), 314–319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1176/jnp.10.3.314

- Marin, R. S. (1991). Apathy: A neuropsychiatric syndrome. The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 3(3), 243–254.

- Marin, R. S., Biedrzycki, R. C., & Firinciogullari, S. (1991). Reliability and validity of the Apathy Evaluation Scale. Psychiatry Res, 38(2), 143–162. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(91)90040-V

- Meesters, Y., Duijzer, W., Nolen, W., Schoevers, R., & Ruhé, H. (2016). Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology en verkorte versie in routine outcome monitoring van Stichting Benchmark GGZ. Tijdschrift Voor Psychiatrie, 58(1), 48–54.

- Merrill, S. S., Seeman, T. E., Kasl, S. V., & Berkman, L. F. (1997). Gender differences in the comparison of self-reported disability and performance measures. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 52A(1), M19–M26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/52A.1.M19

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus: Statistical analysis with latent variables; user’s guide;[version 7]. Muthén et Muthén.

- Neath, A. A., & Cavanaugh, J. E. (2012). The Bayesian information criterion: Background, derivation, and applications. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Computational Statistics, 4(2), 199–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/wics.199

- Penninx, B. W., Beekman, A. T., Smit, J. H., Zitman, F. G., Nolen, W. A., Spinhoven, P., Cuijpers, P., De Jong, P. J., Van Marwijk, H. W. J., Assendelft, W. J. J., et al. (2008). The Netherlands Study of Depression and Anxiety (NESDA): Rationale, objectives and methods. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 17(3), 121–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.256

- Robert, P., Lanctôt, K., & Agüera-Ortiz, L. (2018). Is it time to revise the diagnostic criteria for apathy in brain disorders? The 2018 international consensus group. European Psychiatry, 54, 71–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2018.07.008

- Rush, A. J., Gullion, C. M., Basco, M. R., Jarrett, R. B., & Trivedi, M. H. (1996). The Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (IDS): psychometric properties. Psychological Medicine., 26(3), 477–486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291700035558

- Sakurai, R., Fujiwara, Y., Ishihara, M., Higuchi, T., Uchida, H., & Imanaka, K. (2013). Age-related self-overestimation of step-over ability in healthy older adults and its relationship to fall risk. BMC Geriatrics, 13(1), 44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-13-44

- Simons, L. A., Simons, J., Friedlander, Y., & McCallum, J. (2011). Predictors of long‐term mortality in the elderly: The Dubbo Study. Internal Medicine Journal, 41(7), 555–560. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1445-5994.2009.02106.x

- Studenski, S., Perera, S., Patel, K., et al. (2011). Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA, 305(1), 50–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1923

- Tinetti, M. E., & Williams, C. S. (1998). The effect of falls and fall injuries on functioning in community-dwelling older persons. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 53A(2), M112–M119. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/53A.2.M112

- Tomioka, K., Iwamoto, J., Saeki, K., & Okamoto, N. (2011). Reliability and validity of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) in elderly adults: The Fujiwara-kyo Study. Journal of Epidemiology, 21(6), 459–465. doi:https://doi.org/10.2188/jea.je20110003

- van der Mast, R. C., Vinkers, D. J., & Stek, M. L. (2008). Vascular disease and apathy in old age. The Leiden 85-Plus Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(3), 266–271. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1872

- Von Korff, M., Ormel, J., Keefe, F. J., & Dworkin, S. F. (1992). Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain, 50(2), 133–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-3959(92)90154-4

- Wittchen, H. U., Robins, L. N., Cottler, L. B., Sartorius, N., Burke, J. D., & Regier, D. (1991). Cross-cultural feasibility, reliability and sources of variance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). The Multicentre WHO/ADAMHA Field Trials. British Journal of Psychiatry, 159(5), 645–653. 658. doi:https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.159.5.645

- Wloch, E. G. (2016). Exploring the discordance between selfreported and performance-based measures of physical capability, UCL (University College London).

- Yuen, G. S., Bhutani, S., Lucas, B. J., Gunning, F. M., Abdel Malak, B., Seirup, J. K., Klimstra, S. A., & Alexopoulos, G. S. (2015). Apathy in late-life depression: Common, persistent, and disabling. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 23(5), 488–494. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2014.06.005