Abstract

Objective

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15), a self-report questionnaire, emphasizes the psychological dimension of depression. We aimed to investigate whether GDS-15 scores were associated with mortality in older patients with cancer and describe the course of individual symptoms on the GDS-15.

Methods

An observational, multicenter, prospective study of 288 patients 70 years or older with cancer followed over 24 months. The patients were assessed with the GDS-15 at inclusion, and after four and 12 months. An extended Cox regression model assessed the association between time-dependent GDS-15 scores and mortality.

Results

After adjusting for cancer-related prognostic factors, a one-point increase in GDS-15 sum score increased risk of death by 12%. GDS-15 mean score increased during the first four months of the study, as did odds for the presence of the GDS-15 symptoms ‘feel you have more problems with memory than most’, ‘not feel full of energy’, and ‘think that most people are better off than you’. The most prevalent and persistent GDS-15 symptom was ‘prefer to stay at home, rather than going out and doing new things’, and ‘not to be in good spirits most of the time’ was the least prevalent.

Conclusions

More severe depressive symptoms, as measured by the GDS-15, were associated with higher mortality in older patients with cancer. The importance of emotional distress and how to alleviate it should be investigated further in these patients.

Keywords:

Introduction

Currently, older adults (≥70 years) account for 50% of all new cancer diagnoses, about 70% of cancer deaths, and the number of older patients with cancer is growing due to the aging population (Atag et al., Citation2018; Bluethmann et al., Citation2016; Cancer Registry of Norway, Citation2019).

Mental health for older patients with cancer is understudied, despite its impact on cancer-related outcomes (Anguiano et al., Citation2012; Mitchell, Citation2018; Parpa et al., Citation2015; Saracino & Nelson, Citation2019). Depression is the most common mental health condition in older patients with cancer, and the reported prevalence varies from 13 to 45% between studies (Atag et al., Citation2018; Duc et al., Citation2017; Saracino et al., Citation2017; Weiss Wiesel et al., Citation2015). Whereas some longitudinal studies of older patients with cancer have shown an association between depression and increased mortality (Gouraud et al., Citation2019; Lloyd-Williams et al., Citation2009), others have not (Ferrat et al., Citation2015). Depression in older patients with cancer is reportedly associated with more pain, reduced quality of life, greater disability, and increased costs to the health care system (Anguiano et al., Citation2012; Atag et al., Citation2018; Gouraud et al., Citation2019; Kristjansson et al., Citation2010; Lloyd-Williams et al., Citation2009). Taken this together, it is important to target depression, which is remediable (Mitchell, Citation2018; Saracino & Nelson, Citation2019).

Recognizing depression in older patients with cancer may be challenging, particularly due to overlapping physical symptoms (e.g., fatigue, concentration difficulties, appetite changes) that might stem from depression, the aging process, cancer, coexisting physical disease, or side effects from cancer treatment (Saracino et al., Citation2016). Self-report measures of depressive symptoms like the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) can help identify and assess relevant depressive symptoms among older patients (Balsamo et al., Citation2018; Friedman et al., Citation2005; Midden & Mast, Citation2018; Pocklington et al., Citation2016; Yesavage & Sheikh, Citation1986). The 15-item version of GDS (GDS-15) is easy to administer and emphasizes the psychological dimension of depression over physical symptoms, making it beneficial for older patients with cancer (Friedman et al., Citation2005; Yesavage & Sheikh, Citation1986). The GDS is well validated, used frequently in geriatric populations, and is recommended by the International Society of Geriatric Oncology for the assessment of depressive symptoms in older patients with cancer (Balsamo et al., Citation2018; Wildiers et al., 2014). However, further knowledge of the use of GDS among older patients with cancer has been advocated (Nelson et al., Citation2010).

A few studies have investigated how GDS is associated with deaths in older patients with cancer, and we are not aware of longitudinal studies of the individual symptoms on the GDS-15 (Crawford & Robinson, Citation2008; Ferrat et al., Citation2015). Thus, in this 24-month longitudinal study, including patients with cancer aged ≥ 70 years, we aimed to investigate whether GDS-15 scores were associated with mortality during follow-up and to describe the course of individual GDS-15 symptoms in terms of prevalence and persistence.

Materials and methods

Patients

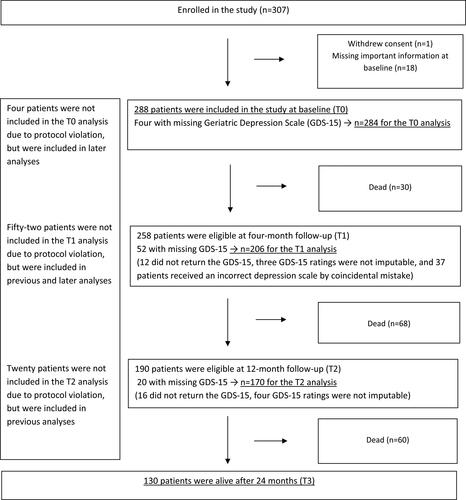

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were ≥70 years and referred for systemic cancer treatment for a histologically confirmed solid tumor (new diagnosis or first relapse after previous curative treatment). Eight oncology outpatient clinics (two university hospitals and six local hospitals) consecutively recruited patients from January 2013 to April 2015 with a referral to the clinic. As presented in , 307 patients were enrolled in the study; one withdrew consent and 18 had important missing information on the baseline questionnaires, and thus 288 patients were included in the present study. More details on the study’s procedures and enrollment have previously been described (Kirkhus et al., Citation2017, Citation2019).

Design

This article is based on a Norwegian, observational, multicenter, prospective study. In the study design, the patients were assessed for depressive symptoms three times: at inclusion (T0), four-month follow-up (T1), and 12-month follow-up (T2). The assessment intervals were related to treatment schedules. The patients were followed for 24 months (T3) or until death.

Measurements

Depressive symptoms were assessed by self-report using the GDS-15, which consists of 15 questions, each answered yes or no and scores from 0 to 1 (Yesavage & Sheikh, Citation1986). The presence of depressive symptoms (score 1) is indicated by affirmative answers to ten questions and negative answers to five. Scores are summarized into a sum score, from 0 to 15, where higher scores indicate more depressive symptoms. At T0, an oncology nurse, trained in study procedures gave the GDS-15 to the patient, whereas it was administered by mail at T1 and T2. Patients also completed the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Core Questionnaire-C30 (QLQ-C30) at T0 (Aaronson et al., Citation1993). The answer to question 24: ‘Last week, did you feel depressed?’ was dichotomized to ‘no’ (‘not at all’, ‘a little’) or ‘yes’ (‘quite a bit’, ‘very much’).

At T0, patients’ oncologists reported cancer type according to the International Classification of Diseases-10th edition (ICD-10), stage of disease (localized/locally advanced or metastatic), and performance status according to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) (Oken et al., Citation1982). For analyses, ECOG scores were dichotomized to ‘good’ (including ratings 0 = ‘asymptomatic’ or 1 = ‘ambulatory’) or ‘poor’ (including ratings 2 = ‘<50% in bed’, 3 = ‘>50% in bed’, or 4 = ‘bedbound’). Patients’ cognitive function was examined using the Norwegian Revised Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE-NR) (scores from 0 to 30) (Folstein et al., Citation1975). A higher score indicates better cognition. We used patient reports on the Physical Health Section, a subscale of the Older Americans’ Resources and Services Questionnaire (OARS), to assess the number of comorbidities (0–15) (Fillenbaum & Smyer, Citation1981). Nutritional status was measured by the Patient-Generated Subjective Global Assessment (PG-SGA) (Ottery, Citation1996). Patients were classified as ‘malnourished’ if they reported weight loss ≥10% the last six months, or the oncology nurse rated them as severely malnourished. Medication was registered and classified according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC).

Treatment data were obtained retrospectively from patients’ medical records and classified as (1) curative (neoadjuvant treatment, adjuvant treatment after curative surgery, or curative radiotherapy); (2) palliative chemotherapy (traditional cytotoxic regimens); (3) other palliative systemic cancer treatment (hormone therapy and modern targeted treatment); (4) other palliative care (radiotherapy, surgery, medical symptom treatment).

Ethical and legal considerations

All participants gave informed, written consent to participate. The study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics South East Norway (2012/104 C) and registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01742442).

Data analysis and statistics

Baseline characteristics were described as means and standard deviations (SD) or frequencies and percentages. We used independent samples t-test to compare GDS-15 scores and χ2-test to analyze differences in mortality between groups.

For analyses, prevalence of a specific GDS-15 symptom was defined as the proportion of patients presenting the symptom at an assessment. Persistence of a specific GDS-15 symptom was defined as the proportion of patients presenting the symptom at one assessment to those presenting it at the preceding assessment.

The intra-class correlations coefficient (ICC) showed some cluster effect present on center level, implying hierarchical structure in the data. Due to repeated measurements for each patient and hierarchical structure in data, a generalized linear mixed model was applied to assess time trend in the prevalence of GDS-15 symptoms, a dichotomous variable. The model contained fixed effects for each time point and random effects for patients nested within the study centers. The results were presented as odds ratios (ORs), quantifying the differences between time points, with corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI) and p-values. A linear mixed model with the same fixed and random effects described above was estimated to assess the time trend in GDS-15 sum score, a continuous variable. Results were presented as mean difference between the time points with corresponding 95% CI and p-values. Analyses were repeated among patients with GDS-15 sum score > 6, as they had a greater probability of being depressed (Cullum et al., Citation2006; Friedman et al., Citation2005; Kirkhus et al., Citation2017). Persistence was not calculated due to small frequencies.

Extended Cox regression model enables to model the association between a longitudinal covariate and time-to-event outcome. Therefore, to assess the association between GDS-15 sum score measured up to three times and mortality, unadjusted extended Cox regression model was estimated first. The model was further adjusted for pre-chosen covariates, known as major cancer-related prognostic factors: age, sex, ECOG performance status, cancer type, treatment, and stage. Survival time was measured as time to death or last follow-up, with censoring at 24 months.

Results with p-value <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Missing values in MMSE (n = 3) and GDS-15 (n = 27, n = 16, and n = 20 at T0, T1, and T2, respectively) were imputed by drawing one random number per value from the empirical distribution generated for each item. Statistical Program for Social Science (SPSS v. 26) and Statistical Analysis System (SAS v. 9.4) were used to analyze data.

Results

This study included 288 patients, 56% were men, mean age was 76.9 (SD = 5.1) years, and 68% received palliative treatment (). At inclusion (T0), 3.1% had MMSE < 24, MMSE mean score was 28.5 (SD = 1.9), GDS-15 mean score was 2.9 (SD = 2.8), and 4% were using antidepressants. There were no differences in GDS-15 mean score between patients who were using or not using antidepressants, 2.5 (SD = 2.5) and 2.9 (SD = 2.8), respectively (p = 0.615).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics at inclusion to the study (n = 288 if not otherwise specified).

No patients withdrew their consent during follow-up. For the GDS-15 analyses at T0, four-month follow up (T1), and 12-month follow-up (T2), respectively 284, 206, and 170 patients were included (). Compared to patients who were dead at 24-month follow-up (T3) (n = 158), patients who were alive (n = 130) had a lower GDS-15 mean score at T0, 2.1 (SD = 2.4) and 3.6 (SD = 3.0), respectively (p < 0.001). By coincidental mistake, 37 patients received an incorrect depression scale at T1 (). They had higher GDS-15 mean score at T0 compared to those with a valid GDS-15 rating at T1 (n = 206), 4.1 (SD = 3.1) and 2.5 (SD = 2.6), respectively (p = 0.005), but there were no differences in mortality at T3 between the two groups (p = 0.280).

The most prevalent GDS-15 symptom at all time points was ‘prefer to stay at home, rather than going out and doing new things’, and the least prevalent symptom was ‘not to be in good spirits most of the time’ (). ‘Prefer to stay at home rather than going out and doing new things’ was among the two most persistent symptoms at both T0-T1 and T1-T2. At T0-T1, ‘not to be in good spirits most of the time’ was the least persistent symptom.

Table 2. Prevalence and persistence of Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) symptoms at different time points (T0 = inclusion to the study, T1 = four-month follow-up, and T2 = 12-month follow-up) and differences in GDS-15 mean score.

The GDS-15 symptoms ‘feel you have more problems with memory than most’, ‘not feel full of energy’, and ‘think that most people are better off than you’ were more prevalent at T1 compared to T0 ().

The analyses for patients with GDS sum score > 6 showed ‘not feel full of energy’ was the most prevalent GDS-15 symptom at T0, T1, and T2, with prevalence of 97.1%, 100%, and 91.7%, respectively (data not tabulated). The least prevalent symptom was ‘not to be in good spirits most of the time’, with prevalence of 14.3% and 16.7% at T0 and T1, respectively. The symptom ‘think that most people are better off than you’ was more prevalent at T1 compared to T0, with OR = 3.9 (CI 1.2; 11.9, p = 0.021).

The unadjusted extended Cox regression model showed that higher GDS-15 sum score was associated with higher risk of death (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.16 [CI 1.12; 1.21, p < 0.001]) (). This association remained significant when adjusted for age, gender, and major cancer-related prognostic factors (HR 1.12 [CI 1.07; 1.17, p < 0.001]).

Table 3. Results from extended Cox regression model (n = 283) showing the association between the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-15) score adjusted for covariates, and risk (expressed as hazard ratio [HR] with 95% confidence interval [CI]) of death.

Discussion

This longitudinal study of older patients with cancer showed that more depressive symptoms were associated with increased mortality, independent of known cancer-related prognostic factors. GDS-15 mean score increased during the first four months of the study, as did odds for the presence of the GDS-15 symptoms ‘feel you have more problems with memory than most’, ‘not feel full of energy’, and ‘think that most people are better off than you’. The most prevalent and persistent symptom was ‘prefer to stay at home, rather than going out and doing new things’, and ‘not to be in good spirits most of the time’ was the least prevalent.

The association between higher GDS-15 scores and higher mortality is a key finding in our study. In the adjusted extended Cox regression model, a one-point increase in GDS-15 sum score increased risk of death by 12%. In line with our finding, a meta-analysis of 76 longitudinal studies by Pinquart and Duberstein indicated that depression and higher levels of depressive symptoms are associated with higher mortality in cancer patients (Mitchell, Citation2018; Pinquart & Duberstein, Citation2010). However, results from the few longitudinal studies of merely older patients with cancer are inconsistent and may not be entirely comparable due to differences in patient populations, follow-up periods, and different depression classification methods (Ferrat et al., Citation2015; Gouraud et al., Citation2019; Krebber et al., Citation2014; Lloyd-Williams et al., Citation2009). A study by Ferrat et al. did not find depression, measured by a four item version of the GDS and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)-IV criteria as an independent predictor of one year mortality (Ferrat et al., Citation2015). These results do not concur with ours, but findings from studies by Lloyd-Williams et al. (Citation2009) and Gouraud et al. (Citation2019) do. Lloyd-Williams et al. used The Edinburgh Depression Scale to assess depressive symptoms in patients with advanced cancer, mean age 69 years and found depression to be a predictor for higher mortality over one year. Gouraud et al. used a data-driven latent class analysis of depressive symptom profiles in older patients with cancer and showed that severe depression was associated with higher mortality over three years.

Several mechanisms can underlie why we and others have found depression and higher levels of depressive symptoms to be associated with higher mortality in cancer patients. Depression may alter immune and neuroendocrine functions that could influence mortality (Spiegel & Giese-Davis, Citation2003). Also, overlapping symptoms between depression and medical illness can confound the picture (Pinquart & Duberstein, Citation2010). Further, an association between depression and acceptance of treatment has been found (Atag et al., Citation2018; Colleoni et al., Citation2000). Hence, treatment adherence may also be affected, leading to overall inferior cancer management (Pinquart & Duberstein, Citation2010). Since GDS-15 is known to emphasize the psychological dimension of depression, our study has demonstrated how psychological aspects of depression may be linked to mortality. Several authors have described how a feeling of hopelessness and/or helplessness among patients with advanced cancer can affect the ability to cope with their disease and their will to live (Chochinov et al., Citation2005; Lloyd-Williams et al., Citation2009; Nelson et al., Citation2010; Parpa et al., Citation2019). Others have discussed that patients with advanced cancer may have a wish to hasten death (WTHD), which could impact mortality (Villavicencio-Chávez et al., Citation2014). WTHD is somewhat challenging to conceptualize but contains physical, social, and psychological factors and is related to suffering (Castelli Dransart et al., 2019; Chochinov et al., Citation2005; Parpa et al., Citation2019; Villavicencio-Chávez et al., Citation2014). Both older age and depression are associated with WTHD (Bornet et al., Citation2020; Chochinov et al., Citation2005; Parpa et al., Citation2019; Villavicencio-Chávez et al., Citation2014), but we do not know if this is the case for older age in cancer.

In our study, the prevalence of depression according to the GDS-15 was dependent on the cut-off value and varied from 12 to 23%, i.e. whether cutoff was set to 4/5, which is often used, or 6/7 (Krebber et al., Citation2014). Other studies of older patients with cancer reported prevalence from 13 to 45%. This relatively large variation may be explained by different definitions of depression and differences in cancer type, stage, and treatment between the study populations (Atag et al., Citation2018; Saracino et al., Citation2017; Saracino & Nelson, Citation2019; Weiss Wiesel et al., Citation2015). The prevalence of depression in our study was thus in the lower range of what has been reported. It is worth noting that at all assessments, 85–90% of our study population ‘thought it was wonderful to be alive’ and ‘did not feel that their situation were hopeless’, indicating that many older patients with cancer are able to appreciate life despite their challenging life situations (Saracino et al., Citation2016).

‘Not to be in good spirits most of the time’ was the least prevalent depressive symptom, both in the overall group, and among patients with GDS-15 score > 6 in our study. This indicated that the core symptom of depression, low mood or sadness, was rare or patients seldom endorsed it. Accordingly, only 6% reported being depressed on the QLQ-C30 questionnaire at inclusion. Our findings may be consistent with an atypical presentation of depression (‘depression without sadness’), which is reportedly more common in older populations (Gallo & Rabins, Citation1999; Saracino & Nelson, Citation2019). Few longitudinal studies on older patients with cancer are available for comparison, but our findings are consistent with those of a study that used GDS to assess depressive symptoms in 84 patients with advanced cancer (Crawford & Robinson, Citation2008). As in our study, the authors also reported that ‘prefer to stay at home rather than going out and doing new things’ was a highly prevalent symptom. This novel finding may be explained as part of depression but may also be a consequence of cancer and its treatment or as a common feature among older patients with cancer, illustrating how some GDS-15 questions may be ambiguous for these patients (Saracino et al., Citation2017). GDS-15 score increased during the first four months of our study as did odds for presence of the symptoms ‘think most people are better off’, ‘not feel full of energy’, and ‘feel you have more memory problems than most’. This could be related to cancer treatment. A majority of patients received either curative or palliative chemotherapy during the first months after inclusion. Undoubtedly, this caused some exhaustion that could affect how patients perceived their situation compared to that of others. Bodily impact of cancer treatment might also be a reason for ‘loss of energy’ (Saracino et al., Citation2016, Citation2017). Furthermore, chemotherapy might affect cognitive functions like concentration and memory. Chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment has been described in 29–51% of older patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy (Loh et al., Citation2016).

The ambiguity of some GDS-15 items raises the question of whether the scores can represent a measure of patients’ total morbidity (Cullum et al., Citation2006; Saracino et al., Citation2017), thus explaining the association with mortality shown in our study. However, the GDS-15 is known to emphasize the psychological dimension of depression, and in our study, we found that a higher GDS-15 score was associated with higher risk of death independent of major cancer-related prognostic factors. This suggests that in older patients with cancer, GDS-15 scores are associated with mortality beyond well-known factors reflecting cancer morbidity. Hence, our results underline the need to focus more on the origin and impact of emotional distress and how to improve treatment (Janberidze et al., Citation2014; Mitchell, Citation2018; Nelson et al., Citation2019; Ostuzzi et al., Citation2018).

We recommend that future studies on the use of GDS-15 in older patients with cancer investigate more specifically how different GDS-15 symptoms may be associated with cancer- related symptoms, comorbidity, and mortality, e.g. by factor analysis or qualitative research.

Limitations

Due to the observational design, our study cannot provide evidence for any causal relationship between depressive symptoms and mortality. Additionally, we cannot rule out that other confounding factors than those adjusted for may have influenced the results. Multiple testing might be an issue in our study and results have to be interpreted with caution. However, for the sake of transparency we chose to present p-values not adjusted for multiple testing.

At four-month follow-up (T1), 37 patients received an incorrect depression rating scale. We do not know if and how this could have influenced our results. The 37 patients had a higher GDS score at inclusion compared to those with a valid GDS-15 rating at T1, but there were no differences in mortality over 24 months between the two groups. Furthermore, depressive symptoms can fluctuate and should have been assessed at more regular intervals. Lastly, although the study population was cognitively healthy at inclusion with a MMSE mean score of 28.5, some patients could have been vulnerable to cognitive impairments during the study, which might have influenced the validity of mailed GDS-15 ratings (Loh et al., Citation2016; Midden & Mast, Citation2018; Morin & Midlarsky, Citation2018). The patients were not assessed with MMSE at follow-ups, thus we do not know if these scores changed during the study.

The strengths of this study are its longitudinal design and use of well-established assessment scales. The results of pre-chosen covariates were in line with what we expected, which we also reckon as a strength for our findings.

Conclusions

In older patients with cancer we showed that more severe depressive symptoms, as measured by the GDS-15, were associated with a higher risk of death, independent of major cancer-related prognostic factors. This indicates that focus on emotional distress and depressive symptoms are needed in the treatment of these patients. The importance of emotional distress and how to alleviate it should be further investigated.

Symptoms such as memory problems and lack of energy that can be part of a depression, may also be a consequence of cognitive impairment, having cancer, or receiving cancer treatment. Hence, careful clinical evaluation is required to determine the origin of these symptoms.

Author’s contributions

Study concepts and design: G. Selbæk. M. Slaaen, Data acquisition: M. Harneshaug, L. Kirkhus, M. Slaaen. Quality control of data and algorithms: M. Harneshaug, L. Kirkhus, J. Šaltytė Benth, M. Slaaen. Data analysis and interpretation: T. Borza, M. Harneshaug, L. Kirkhus, J. Šaltytė Benth, G. Selbæk. S. Bergh, M. Slaaen. Statistical analysis: T. Borza, J. Šaltytė Benth. Manuscript preparation: T. Borza, M. Harneshaug, L. Kirkhus, J. Šaltytė Benth, G. Selbæk. S. Bergh, M. Slaaen. Manuscript editing: T. Borza, M. Harneshaug, L. Kirkhus, J. Šaltytė Benth, G. Selbæk, S. Bergh, M. Slaaen. Manuscript review: T. Borza, M. Harneshaug, L. Kirkhus, J. Šaltytė Benth, G. Selbæk. S. Bergh, M. Slaaen. All authors have approved the submitted manuscript version.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the cancer clinics at Innlandet Hospital Trust, Oslo University Hospital, and Akershus University Hospital for their participation in the study. A special thanks to the patients and the oncology nurses at all locations who participated in inclusion and assessment of patients.

Disclosure statement

Geir Selbæk is member of the advisory board of Biogen Norway. The other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings in this study are not publicly available due to general Norwegian Data protection regulations. However, the data, which are stored according to present regulations at Innlandet Hospital Trust (‘Cancer in the elderly, 0303/150337’), will be available upon visiting our Research center.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaronson, N. K., Ahmedzai, S., Bergman, B., Bullinger, M., Cull, A., Duez, N. J., Filiberti, A., Flechtner, H., Fleishman, S. B., & de Haes, J. C. (1993). The European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QLQ-C30: A quality-of-life instrument for use in international clinical trials in oncology. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 85(5), 365–376. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/85.5.365

- Anguiano, L., Mayer, D. K., Piven, M. L., & Rosenstein, D. (2012). A literature review of suicide in cancer patients. Cancer Nursing, 35(4), E14–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e31822fc76c

- Atag, E., Mutlay, F., Soysal, P., Semiz, H. S., Kazaz, S. N., Keser, M., Ellidokuz, H., & Karaoglu, A. (2018). Prevalence of depressive symptoms in elderly cancer patients receiving chemotherapy and influencing factors. Psychogeriatrics: The Official Journal of the Japanese Psychogeriatric Society, 18(5), 365–370. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/psyg.12329

- Balsamo, M., Cataldi, F., Carlucci, L., Padulo, C., & Fairfield, B. (2018). Assessment of late-life depression via self-report measures: A review. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 13, 2021–2044. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S178943

- Bluethmann, S. M., Mariotto, A. B., & Rowland, J. H. (2016). Anticipating the “Silver Tsunami”: Prevalence trajectories and comorbidity burden among older cancer survivors in the United States. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 25(7), 1029–1036. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0133

- Bornet, M. A., Rubli Truchard, E., Waeber, G., Vollenweider, P., Bernard, M., Schmied, L., & Marques-Vidal, P. (2020). Life worth living: Cross-sectional study on the prevalence and determinants of the wish to die in elderly patients hospitalized in an internal medicine ward. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 348. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01762-x

- Cancer Registry of Norway. (2019). Cancer in Norway 2018 - Cancer incidence, mortality, survival and prevalence in Norway. C. R. o. Norway.

- Castelli Dransart, D. A., Lapierre, S., Erlangsen, A., Canetto, S. S., Heisel, M., Draper, B., Lindner, R., Richard-Devantoy, S., Cheung, G., Scocco, P., Gusmão, R., De Leo, D., Inoue, K., De Techterman, V., Fiske, A., Hong, J. P., Landry, M., Lepage, A.-A., Marcoux, I., … Wyart, M. (2021). A systematic review of older adults’ request for or attitude toward euthanasia or assisted-suicide. Aging & Mental Health, 25(3), 420–430. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1697201

- Chochinov, H M., Hack, T., Hassard, T., Kristjanson, L. J., McClement, S., & Harlos, M. (2005). Understanding the will to live in patients nearing death. Psychosomatics, 46(1), 7–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.psy.46.1.7

- Colleoni, M., Mandala, M., Peruzzotti, G., Robertson, C., Bredart, A., & Goldhirsch, A. (2000). Depression and degree of acceptance of adjuvant cytotoxic drugs. The Lancet, 356(9238), 1326–1327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(00)02821-X

- Crawford, G. B., & Robinson, J. A. (2008). The geriatric depression scale in palliative care. Palliative & Supportive Care, 6(3), 213–223. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951508000357

- Cullum, S., Tucker, S., Todd, C., & Brayne, C. (2006). Screening for depression in older medical inpatients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(5), 469–476. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1497

- Duc, S., Rainfray, M., Soubeyran, P., Fonck, M., Blanc, J. F., Ceccaldi, J., Cany, L., Brouste, V., & Mathoulin-Pelissier, S. (2017). Predictive factors of depressive symptoms of elderly patients with cancer receiving first-line chemotherapy. Psycho-Oncology, 26(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4090

- Ferrat, E., Paillaud, E., Laurent, M., Le Thuaut, A., Caillet, P., Tournigand, C., Lagrange, J. L., Canouï-Poitrine, F., & Bastuji-Garin, S. (2015). Predictors of 1-year mortality in a prospective cohort of elderly patients with cancer. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 70(9), 1148–1155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glv025

- Fillenbaum, G. G., & Smyer, M. A. (1981). The development, validity, and reliability of the OARS multidimensional functional assessment questionnaire. Journal of Gerontology, 36(4), 428–434. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/36.4.428

- Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). “Mini-mental state”. A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

- Friedman, B., Heisel, M. J., & Delavan, R. L. (2005). Psychometric properties of the 15-item geriatric depression scale in functionally impaired, cognitively intact, community-dwelling elderly primary care patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 53(9), 1570–1576. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53461.x

- Gallo, J. J., & Rabins, P. V. (1999). Depression without sadness: Alternative presentations of depression in late life. American Family Physician, 60(3), 820–826.

- Gouraud, C., Paillaud, E., Martinez-Tapia, C., Segaux, L., Reinald, N., Laurent, M., Corsin, L., Hoertel, N., Gisselbrecht, M., Mercadier, E., Boudou-Rouquette, P., Chahwakilian, A., Bastuji-Garin, S., Limosin, F., Lemogne, C., Canoui-Poitrine, F., & Group, E. S. (2019). Depressive symptom profiles and survival in older patients with cancer: Latent class analysis of the ELCAPA cohort study. The Oncologist, 24(7), e458–e466. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1634/theoncologist.2018-0322

- Janberidze, E., Hjermstad, M. J., Brunelli, C., Loge, J. H., Lie, H. C., Kaasa, S., & Knudsen, A. K. (2014). The use of antidepressants in patients with advanced cancer-results from an international multicentre study. Psycho-oncology, 23(10), 1096–1102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3541

- Kirkhus, L., Harneshaug, M., Šaltytė Benth, J., Grønberg, B. H., Rostoft, S., Bergh, S., Hjermstad, M. J., Selbæk., G., Wyller, T. B., Kirkevold, Ø., Borza, T., Saltvedt, I., & Jordhøy, M. S. (2019). Modifiable factors affecting older patients’ quality of life and physical function during cancer treatment. Journal of Geriatric Oncology, 10(6), 904–912. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.08.001

- Kirkhus, L., Šaltytė Benth, J., Rostoft, S., Grønberg, B. H., Hjermstad, M. J., Selbæk., G., Wyller, T. B., Harneshaug, M., & Jordhøy, M. S. (2017). Geriatric assessment is superior to oncologists’ clinical judgement in identifying frailty. British Journal of Cancer, 117(4), 470–477. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2017.202

- Krebber, A. M. H., Buffart, L. M., Kleijn, G., Riepma, I. C., Bree, R., Leemans, C. R., Becker, A., Brug, J., Straten, A., Cuijpers, P., & Verdonck‐de Leeuw, I. M. (2014). Prevalence of depression in cancer patients: A meta-analysis of diagnostic interviews and self-report instruments. Psycho-Oncology, 23(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3409

- Kristjansson, S. R., Jordhøy, M. S., Nesbakken, A., Skovlund, E., Bakka, A., Johannessen, H., & Wyller, T. (2010). Which elements of a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) predict post-operative complications and early mortality after colorectal cancer surgery? Journal of Geriatric Oncology, 1(2), 57–65.

- Lloyd-Williams, M., Shiels, C., Taylor, F., & Dennis, M. (2009). Depression-an independent predictor of early death in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of Affective Disorders, 113(1–2), 127–132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2008.04.002

- Loh, K. P., Janelsins, M. C., Mohile, S. G., Holmes, H. M., Hsu, T., Inouye, S. K., Karuturi, M. S., Kimmick, G. G., Lichtman, S. M., Magnuson, A., Whitehead, M. I., Wong, M. L., & Ahles, T. A. (2016). Chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment in older patients with cancer. Journal of Geriatric Oncology, 7(4), 270–280. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2016.04.008

- Midden, A. J., & Mast, B. T. (2018). Differential item functioning analysis of items on the Geriatric Depression Scale-15 based on the presence or absence of cognitive impairment. Aging & Mental Health, 22(9), 1136–1142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1337716

- Mitchell, A. J. (2018). Why doesn’t depression treatment improve cancer survival? The Lancet. Psychiatry, 5(4), 289–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30086-5

- Morin, R. T., & Midlarsky, E. (2018). Depressive symptoms and cognitive functioning among older adults with cancer. Aging & Mental Health, 22(11), 1465–1470. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1363868

- Nelson, C. J., Cho, C., Berk, A. R., Holland, J., & Roth, A. J. (2010). Are gold standard depression measures appropriate for use in geriatric cancer patients? A systematic evaluation of self-report depression instruments used with geriatric, cancer, and geriatric cancer samples. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 28(2), 348–356. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0201

- Nelson, C. J., Saracino, R. M., Roth, A. J., Harvey, E., Martin, A., Moore, M., Marcone, D., Poppito, S. R., & Holland, J. (2019). Cancer and Aging: Reflections for Elders (CARE): A pilot randomized controlled trial of a psychotherapy intervention for older adults with cancer. Psycho-oncology, 28(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4907

- Oken, M. M., Creech, R. H., Tormey, D. C., Horton, J., Davis, T. E., McFadden, E T., & Carbone, P. P. (1982). Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. American Journal of Clinical Oncology, 5(6), 649–655.

- Ostuzzi, G., Matcham, F., Dauchy, S., Barbui, C., & Hotopf, M. (2018). Antidepressants for the treatment of depression in people with cancer. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4, CD011006. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011006.pub3

- Ottery, F. D. (1996). Definition of standardized nutritional assessment and interventional pathways in oncology. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif.), 12(1 Suppl), S15–S19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0899-9007(96)90011-8

- Parpa, E., Tsilika, E., Galanos, A., Nikoloudi, M., & Mystakidou, K. (2019). Depression as mediator and or moderator on the relationship between hopelessness and patients’ desire for hastened death. Supportive Care in Cancer, 27(11), 4353–4358. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-019-04715-2

- Parpa, E., Tsilika, E., Gennimata, V., & Mystakidou, K. (2015). Elderly cancer patients’ psychopathology: A systematic review: Aging and mental health. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 60(1), 9–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2014.09.008

- Pinquart, M., & Duberstein, P. R. (2010). Depression and cancer mortality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 40(11), 1797–1810. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291709992285

- Pocklington, C., Gilbody, S., Manea, L., & McMillan, D. (2016). The diagnostic accuracy of brief versions of the Geriatric Depression Scale: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(8), 837–857. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4407

- Saracino, R. M., & Nelson, C. J. (2019). Identification and treatment of depressive disorders in older adults with cancer. Journal of Geriatric Oncology, 10(5), 680–684. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgo.2019.02.005

- Saracino, R. M., Rosenfeld, B., & Nelson, C. J. (2016). Towards a new conceptualization of depression in older adult cancer patients: A review of the literature. Aging & Mental Health, 20(12), 1230–1242. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1078278

- Saracino, R. M., Weinberger, M. I., Roth, A. J., Hurria, A., & Nelson, C. J. (2017). Assessing depression in a geriatric cancer population. Psycho-oncology, 26(10), 1484–1490. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4160

- Spiegel, D., & Giese-Davis, J. (2003). Depression and cancer: Mechanisms and disease progression. Biological Psychiatry, 54(3), 269–282. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00566-3

- Villavicencio-Chávez, C., Monforte-Royo, C., Tomás-Sábado, J., Maier, M. A., Porta-Sales, J., & Balaguer, A. (2014). Physical and psychological factors and the wish to hasten death in advanced cancer patients. Psycho-Oncology, 23(10), 1125–1132. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3536

- Weiss Wiesel, T. R., Nelson, C. J., Tew, W. P., Hardt, M., Mohile, S. G., Owusu, C., Klepin, H. D., Gross, C. P., Gajra, A., Lichtman, S. M., Ramani, R., Katheria, V., Zavala, L., & Hurria, A. (2015). The relationship between age, anxiety, and depression in older adults with cancer. Psycho-Oncology, 24(6), 712–717. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3638

- Wildiers, H., Heeren, P., Puts, M., Topinkova, E., Janssen-Heijnen, M. L., Extermann, M., Falandry, C., Artz, A., Brain, E., Colloca, G., Flamaing, J., Karnakis, T., Kenis, C., Audisio, R. A., Mohile, S., Repetto, L., Van Leeuwen, B., Milisen, K., & Hurria, A. (2014). International Society of Geriatric Oncology consensus on geriatric assessment in older patients with cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, 32(24), 2595–2603. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8347

- Yesavage, J. A., & Sheikh, J. I. (1986). Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). Clinical Gerontologist, 5(1–2), 165–173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1300/J018v05n01_09