Abstract

Objectives: This evaluation study was designed to examine the factors that contribute the promotion of social connectedness among people with dementia and their caregivers through social recreational programs; develop an understanding of volunteer’s impact on program success; and identify the barriers and facilitators to improve the volunteer-based programs to promote social connectedness.

Method: A qualitative descriptive research design was used to explore the study participants’ lived experiences of social recreational programs from Alzheimer’s Society of Durham Region (ASDR) in Ontario, Canada. A final sample of 31 participants was recruited including people with dementia, informal caregivers, and community volunteers. Qualitative data was collected through face-to-face semi-structured interviews. Emerging themes were derived from the qualitative descriptive data using thematic analysis.

Results: The qualitative interviews highlighted the impact of social recreational programs on people with dementia, caregivers and volunteers in the promotion of social connectedness, as well as the examination of barriers and facilitators to identify opportunities for the future improvement of ASDR programs that would benefit the dementia populations. The study findings revealed that the project ‘Living Well with Dementia’ has been able to successfully foster social connectedness through its volunteer-led social recreational programs by promoting the physical and mental well-being of people with dementia and their caregivers.

Conclusion: Our study findings underscored the critical roles of volunteers who contributed to the success of community-based programs. Future research is needed to identify the opportunities to address current gaps in services and to strengthen the social recreational programs using evidence-based practices and client-centered approaches.

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at http://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1950614.

Background

Social isolation for people with dementia

As the population ages, an array of age-related health concerns is emerging (He et al., Citation2016), and certain health requirements are needed to be fulfilled in order to meet the needs and specificity of care for older adults outside the traditional medical care model (Moody & Phinney, Citation2012). One of the most vulnerable groups in this context that requires significant level of attention is individuals living with dementia and their caregivers. In the year of 2020, it is estimated that 50 million global citizens are living with dementia (World Health Organization [WHO], Citation2020), and that number continues to increase (Wong et al., Citation2016). The term dementia is used to describe an umbrella of health issues that encompasses a variety of symptoms related to the decline of cognitive function, which influences a person’s ability to execute everyday activities (Wong et al., Citation2016). It has been found that the people living with dementia and individuals providing care for a family member with dementia are at increased risk of experiencing social isolation (Alzheimer Society of Durham Region [ASDR], Citation2020b; Brodaty & Donkin, Citation2009; Kovaleva et al., Citation2018).

Social Isolation is defined as an absence of social belongingness, feelings of loss in relationships, or lack of meaningful interpersonal relationships (Singer, Citation2018). The term can be mostly attributed to the lack of engagement with others, specifically in regard to the ability to make meaningful social relationships (Singer, Citation2018). Social isolation is described as an individual’s lack of sense of social belonging in a community, decline in social engagement, and having significant minimal number of social contacts, which in part leading to the inadequate sense of a satisfying quality relationship (Sun, Biswas, et al., Citation2019). Experience of social isolation by an older individual depends on several factors, most of which are objective characteristics found in the individual’s community (De Jong Gierveld & Van Tilburg, Citation2010). These include but not limited to socio-economic factors such as living area, level of knowledge and awareness, access to transportation, availability of support, ethnicity and culture, sexual and gender identity, transitions in life and presence of social network or social relationships along with physical and mental health conditions (Choi et al., Citation2015). A vast array of negative health risks is observed to be associated with social isolation among older adults (Alpert, Citation2017). This is mainly due to the many losses occurring at the physical and psychological level including social roles, mobility, and living arrangements, which correlate to a decline in social relationships and an increase in isolation (British Columbia Ministry of Health, Citation2004; National Institute on Aging, Citation2019). This is especially true for older adults with cognitive impairments (i.e. Alzheimer’s or any other forms of dementias) as it can pose as a serious health risk (The National Seniors Council, Citation2014). Not only does social isolation affect the individual living with dementia, but it can also be detrimental to the caregivers. This is mainly due to the increase in burden of care, facing obstacles, and balancing other affairs (i.e. career, and relationships) (Biordi & Nicholson, Citation2013). Literature has gone as far as to label caregivers as the ‘invisible second patients’ due to the stressors that come with caring for a person living with dementia (i.e. fatigue, and burnout) (Brodaty & Donkin, Citation2009). Studies have identified that the impact of isolation and loneliness on health and mortality were of the same order of magnitude as such risk factors as high blood pressure, obesity, and smoking (Cattan et al., Citation2005; National Institute on Aging, Citation2019). Social isolation may act as a contributing factor in increasing the risk of cardiac attack, cardio-vascular illness, faster deterioration of mental health impairment, depression, and overall poor quality of physical and psychological health (Cattan et al., Citation2005; National Institute on Aging, Citation2019). These negative health risks highlighted the importance to implement strategies to combat social isolation among vulnerable populations including people with dementia and their caregivers.

Volunteer-based social recreational programs in Canada

In 2016, it was estimated that approximately 228,000 people were living with dementia in Ontario, Canada, and by 2038, this number will be increased to over 430,000 (Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care [MOHLTC], Citation2016; Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2018). To address the negative impact associated with social isolation, social recreational programs that are led by community volunteers are developed to provide the support systems to relieve the challenges faced by members of the dementia community in Canada. Alzheimer Society of Canada has been the leading community organization who actively develops stimulating social recreational programs for people with dementia and their caregivers to combat the negative effects of social isolation. Through the engagement and training of community volunteers, the different regional societies within the Alzheimer Society of Canada develop and implement social recreational programs with the aim of reducing social isolation and helping people to live well with dementia (Alzheimer Society of Canada, Citation2020b). For example, within the Durham Region of Ontario, Brainwave Café offers a dementia friendly place for people with dementia, their families and friends to meet for meaningful conversations, receiving peer support and engaging in stimulating activities (Alzheimer Society of Durham Region [ASDR], Citation2020a). Caregiver Support Group provides the opportunities for social interaction, and it helps to contribute to a greater sense of well-being, promote mental well-being and a sense of connectedness for caregivers (ASDR, 2020a). Minds-in-Motion is a community-based social program that incorporates physical activity and cognitive stimulation for people with early to mid-stage dementia and their care partners (Alzheimer Society of Canada, Citation2020a). Pilot study findings showed that Minds-in-Motion participants reported decreased social isolation and most participants continued to participate in physical and social recreational programs in the future (Alzheimer Society of Canada, Citation2020a). The main goal of these programs is to promote the social connectedness and interaction among people with dementia and their caregivers to improve their physical and mental health, and to support a better quality of life. These types of non-pharmacological and complementary interventions have been found to be anecdotally successful in facilitating the social engagement of people with dementia (Cammisuli et al., Citation2016; Zucchella et al., Citation2018).

Study purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the project: ‘Living Well with Dementia’, which was designed by the Alzheimer Society of Durham Region (ASDR) in Ontario, Canada. ‘Living Well with Dementia’ project focuses on reducing social isolation for people with dementia and their caregivers through the development of social recreational programs that are being co-facilitated by community volunteers. The aim of this study was to examine how volunteers can be best utilized in social recreational programs to combat the effect of social isolation among people with dementia and their caregivers. This evaluation project aimed at providing the future strategic directions for ASDR to improve the quality of life of people with dementia and their caregivers by investing in the social recreational programs that have the greatest impact on the reduction of social isolation. This study can provide important implications into the effective use of social recreational programs, and the engagement of volunteers to create more dementia-friendly communities through promoting the social participation of people with dementia. This study focused on achieving the following three objectives: (1) To explore the lived experiences of people with dementia, caregivers and volunteers regarding the impact of social recreational programs in reducing social isolation;

(2) To understand the role of volunteers in social recreational programs and its impact on the dementia community; and (3) To explore the barriers and facilitators that improve the volunteer-based social recreational programs for people with dementia and their caregivers to promote their sense of social connectedness.

Methods

Study design

An exploratory qualitative descriptive research design was used to examine the experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers within the ASDR social recreational programs that are being co-facilitated by the community volunteers. This research employed qualitative methodology to conduct individual in-depth interviews using a series of open-ended questions to explore the perspectives of people with dementia, caregivers and volunteers’ experiences of the ASDR programs

Study sample

The target populations for this study were people with dementia and their caregivers who were accessing the ‘Living Well with Dementia’ social recreational programs, as well as community volunteers who facilitated these programs. There was a total of 31 study participants (11 people with dementia; 13 caregivers; and 7 volunteers) in the final sample and they were recruited from the following three primary programs: (1) Minds in Motion; (2) Brain Wave Café; and (3) Caregiver Support Groups. Study participants reported their participation in additional programs, including Singing Choir, Walking Group, and Blue Umbrella Programs. The inclusion criteria of eligible study participants were people with dementia; caregivers and volunteers who were involved in the social recreational programs that falls under the Living Well with Dementia project. All participants were English-speaking adults (18+) and were able to provide informed consent. People with dementia and their caregivers were older adults who were over the age of 65. To ensure participants able to provide informed consent on their own, people with dementia who had mild or moderate cognitive impairment were included in the study. Using a demographic questionnaire, the level of cognitive impairment was self-identified by the participants, and it was subsequently confirmed by the program facilitators. Caregivers included in this study were family members who accompanied the people with dementia to the programs, such as spouses and children. Exclusion criteria included non-English speaking individuals, and individuals with advanced stage of dementia due to their inability to provide informed consent on their own.

Recruitment

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to help facilitate the successful recruitment of eligible study participants. For people with dementia and their caregivers, they were recruited using the promotional flyers being distributed within the ASDR programs, along with the word of mouth by the program facilitators. Furthermore, the Research Assistant (RA) from Ontario Tech University attended the social recreational programs held at the organization to help recruit the target populations, including Minds in Motion; Brain Wave Café and Caregiver Support Group. By attending these programs in-person, the RA clearly explained to the potential study participants about the study purpose, procedure, impact and significance of the study. The letter of information was distributed prior to the research briefing to facilitate the informed consent process with the potential study participants. Individuals who expressed interest during the recruitment efforts were requested to participate in the interview after the social recreational program on the same day, or they were offered the option to schedule an interview at a later date of their choice. Recruitment of study participants for community volunteers was facilitated by the Volunteer Coordinator at ASDR through the distribution of promotional flyer, as well as a recruitment email to all community volunteers at ASDR with study information that outlined the research purpose, procedure and study significance. Individuals who were interested in the study participation were requested to contact the RA to schedule an interview at a mutually agreed upon time and location of their preference.

Data collection

Ethics approval was obtained from the Ontario Tech University Research Ethics Board (Protocol Reference and REB approval #14171). There was no existing relationship established between the researchers and the study participants prior to the study commencement. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. Upon study participant’s expression of interest in the study and following informed consent, an interview was scheduled and conducted by the RA. All the interviews were conducted in a meeting room at the ASDR. Prior to the interview, study participants were asked to complete a brief demographic questionnaire following the completion of consent form. The one-on-one, in-depth, semi-structured interview lasted approximately 30-45minutes, and were audio-recorded upon informed consent by the study participants. The interview process was guided by an interview guide, which was pilot-tested for usability and accessibility among the providers at ASDR (Refer to Appendix B for the Interview Guides). During the interview, the researcher asked a series of open-ended questions to explore the perspectives of people with dementia, caregivers and volunteers’ experiences about the ASDR programs, as well as making field notes to reflect on the interview process. All people with dementia were offered the option to have their caregivers accompanied them during the interview as non-participants to provide comfort and support as needed. All study participants were offered the option to engage in participant checking, but none of them requested to provide feedback on the transcript and data analysis. No repeat interview was needed and none of the study participants dropped out for the duration of the study.

Data analysis

The demographic questionnaire surveys were reviewed to analyze the characteristics of age, gender, academic background, geographical location of participants, frequency of program participation, and perception about the impact of program on physical and mental health. Transcriptions and preliminary analysis (Initial coding) of the interviews were performed simultaneously while data collection process continued. The goal is to utilize the emerging analysis to help with informing the ongoing data collection process. Data collection efforts continued until data saturation was reached. Thematic analysis was conducted for the analysis of qualitative descriptive data. The process of qualitative data analysis was grounded within Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) thematic analytical model. This model outlines the six phases of thematic analysis including: 1) Familiarizing with collected research data, 2) Generating initial codes of data in a systematic fashion, 3) Collating codes into potential themes, 4) Reviewing generated themes, 5) Defining and naming themes, and 6) Producing the report. For the thematic analysis, each transcript was read individually and was coded to generate emerging themes that are derived from the interview data. The data analysis was conducted by the principal investigator, research assistants, research practicum students and undergraduate work-study students from Ontario Tech University. A codebook was developed by the RA and was used as a template to develop the coding tree by the research team. Once the set of codes was finalized and all the individual transcripts were coded, peer debrief meeting was conducted within the research team to discuss the emerging themes and the associated meanings. Upon the completion of peer debriefing of coding, a list of common themes was identified for each group of study participants (people with dementia; caregivers; and volunteers) that described the main factors contributing to the reduction of social isolation and the increase of social connectedness. The overarching themes and sub-themes generated were being compared within and across each group to examine any differences and similarities of common themes. The identified themes were accompanied by the data extracts (illustrative quotes) for auditability.

Study findings

Quantitative descriptive findings

The quantitative descriptive survey collected the demographics of the participants including age; gender; residence location; living arrangement; educational background; stage of dementia; disease treatment; frequency of program attendance; changes related to level of confidence; stress level; sleeping pattern, appetite; loneliness and pleasure in life associated with program participation (Refer to Appendix C Demographic Form). For the survey questions pertaining to changes after participation in program activities, the questionnaire asked the participants if they experienced a positive change, negative change, or no change.

Age and gender

The mean age of people with dementia was 75.73 years, ranging from 66-83 years. The age distribution of caregivers (CGs) reported as mean (range) in years were 74.35 (63-83). Age distribution of volunteers ranged from 24-73 years. Majority of the people with dementia were male (63.6%) whereas a majority of study participants were female in both CGs (58.3%) and volunteers (71.42%) cohort.

Socio-economic characteristics

Majority of the study participants were from Whitby area (27% of people with dementia and 33% of CGs) followed by Oshawa and Pickering in Ontario, Canada. Other reported cities of residence from Ontario included Newcastle, Pefferlaw, Port Perry, and Scarborough. Majority of participants reported College/University degree as their highest level of education among the people with dementia (45.5%) and volunteers (100%) cohort, whereas High School Diploma was reported as the highest level of education by the majority of CGs cohort. All of the people with dementia reported to be living with their spouses, with the exception of one person with dementia reported residing in the retirement home. Majority of the participants in the people with dementia cohort reported their severity of dementia as mild (45.5%) or moderate (45.5%) and are currently being treated with medications (72.7%).

Program participation and program impact

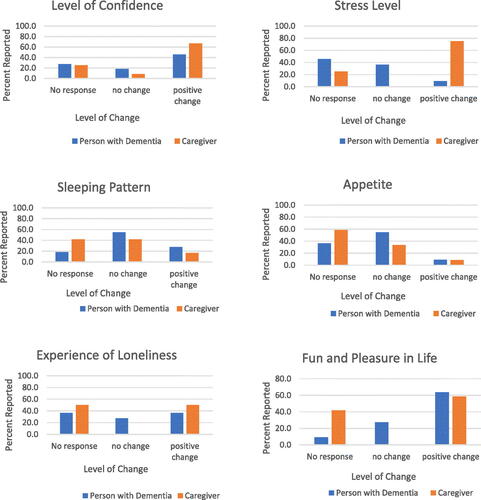

Most frequently reported ASDR program attended by people with dementia and CGs cohorts was Minds in Motion (66.7%). Other programs reported by the participants included Brainwave Cafes, Blue Umbrella Program and Walking Buddies Program. Following participation in the social recreational programs, positive changes were reported by both people with dementia and CGs in regard to the level of confidence, stress level, sleeping pattern, appetite, loneliness, and pleasure in life as demonstrated in .

Qualitative findings from interviews

The qualitative interview findings highlighted the impact of social recreational programs on people with dementia, caregivers and volunteers in the promotion of social connectedness, as well as the examination of barriers and facilitators to identify opportunities for the future improvement of ASDR programs to that would benefit the dementia community.

Program impact on the perceptions of social isolation for people with dementia and their caregivers

The qualitative interviews provided the examination of the factors that enabled the greatest reduction of social isolation from the perspectives of people with dementia and their caregivers. Four overarching themes were identified that explored the perspectives on social isolation among people with dementia and their caregivers after their participation in ASDR programs: (1) Developing Social Connectedness in the Community; (2) Building Positive Attitude Towards Living Well with Dementia; (3) Improving Physical and Mental Well-Being through Sensory Stimulation; and (4) Increased Awareness about Dementia and related programs/services through Education

Developing social connectedness in the community

The most prominent and widely shared outcome of participating in the ASDR social recreational programs was the development of social connectedness in the community. People with dementia and their caregivers were at high risk of experiencing social isolation as a result of the symptoms of dementia. Attending the programs at ASDR allowed the study participants to stay socially connected and engaged in the community. Similarly, volunteers experienced an increased sense of social connectedness through their contributions in the ASDR programs. The social recreational programs facilitated the development of social connection among people with dementia, their caregivers, and volunteers as demonstrated by the following three attributes: (1) Establishing a sense of belonging; (2) Fostering relationship growth; (3) Strengthening social support network.

Establishing a sense of belonging: Sense of belonging refers to people with dementia’s ability to form social connection with those who shared similar life experiences, which has resulted in a strong sense of bonding among the program participants. All study participants reported that involving in the ASDR programs not only allowed them to socialize, but also gave them an opportunity to connect with others who shared similar life experiences, thus allowing them to build a ‘sense of belonging’ in the community.

‘We get to know people who can understand your problems… as opposed to someone who doesn’t know anything about the disease… you know that everyone belong here and knows what’s the matter with you…’ (PWD9)

‘It (ASDR program) allowed us to, meet and talk with people who are sharing the same situation.’ (CG3)

Fostering relationship growth: People with dementia and their caregivers indicated that the positive influence of the social recreational program was to rekindle existing relationships with each other, their family members and loved ones, while developing new friendships.

‘It was a chance to enjoy activities together. Probably more so than we were able to do before… When you’re involved in a lot of activities together, it’s a good thing because you can share more, and this brings us closer together’ (CG3).

‘I like the idea of being able to talk and relate to people on the same level when I join these programs.’ (PWD10).

Strengthening social support network: Another sub-theme related to the development of social connectedness is the positive impact of social recreational programs on strengthening the social support network for the program users. Strengthening social support network refers to the feeling of social inclusion experienced by people with dementia, which helped contribute to the development of a strong social support network through their participation in the programs. Through participating in the ASDR programs, study participants were given an opportunity to be part of a community that was supportive of each other to allow for an increased social engagement. People with dementia explained that they felt uncomfortable engaging in the programs during the initial stage. As their involvement in the program progressed, they became more and more comfortable interacting with others, and they were better able to help the new members in the group to feel more socially included. The increased feeling of social inclusion was an indication of people with dementia’ ability to strengthen their social support network through their participations in the ASDR programs.

‘I tried to join to the program because when I had the disease, I was very depressed… I just didn’t want to see nobody, I didn’t want to talk to nobody. Now I made friends and I helped some other people who were just like me. If they can’t walk and I help them by serving them tea or coffee…’ (PWD8)

Caregivers indicated that ASDR programs gave them an opportunity to seek out social support to manage the difficulties arising from the care of their loved ones: ‘All I can say is that with this kind of program, you’re never on your own dealing with problems… The caregiver program is a good support network.’ (CG4)

Building positive attitude towards living well with dementia

Building positive attitude towards living well with dementia were identified to be a notable impact of social recreational programs at ASDR. People with dementia and their caregivers identified that the programs enabled them to increase the understanding of their diagnosis and develop a positive attitude about their illness experience, while allowing them to practice effective coping strategies for managing their disease conditions. Four positive attitudes were developed by people with dementia and their caregivers as a result of their program participation: (1) Increased sense of acceptance; (2) Reduced stigmatization; (3) Realizing self-actualization; and (4) Strengthening resiliency.

Increased sense of acceptance: Increased sense of acceptance focuses on people with dementia’s increased acceptance towards his/her diagnosis of dementia, the associated symptoms, and related consequences. Both people with dementia and their caregivers reported a decreased sense of self-depreciative feelings, and they were able to develop an increased sense of acceptance after their participation in the social recreational programs. People with dementia and their caregivers were able to build their self-confidence while developing meaningful friendships. They felt an increased sense of acceptance of their disease condition, while recognizing that others were going through the same struggles and sharing similar stories.

‘I’m saying to myself what’s the difference… so what with having the illness? I’ve stopped saying to myself, poor me! I’m not the only one…there are so many people like me with this illness’. (PWD4)

‘With programs like this, he (my husband) doesn’t come home beating himself up by worrying about saying something wrong or he did something wrong… and he doesn’t come back feeling down, but being able to come to terms with his illness.’ (CG4)

Reduced stigmatization: Reduced stigmatization refers to people with dementia’s reduced sense of fear and shame of being judged by others regarding their symptoms of dementia. Living with dementia is associated with internal and external stigma, which often acts as a major barrier to seek appropriate treatment, health care services and support. One of the most commonly shared impact of ASDR programs was the decreased in perceived stigma experienced by people with dementia and their caregivers. These social recreational programs provided an opportunity for people with dementia and their caregivers to socialize without the fear of being judged, as well as creating a social platform for them to freely express themselves.

‘We can talk to each other without being judged cause we’re on the same level. So that makes it a big difference.’ (PWD10).

‘There’s no judgement here… I mean if you say something that’s inappropriate or you do something that’s wrong, nobody’s going to put you down for it or make you feel stupid… Which is what my spouse goes through a lot in the outside world. He feels very self-conscious outside whereas there is no judgement here.’ (CG4)

Realizing self-actualization: Perceived loss of capability and purpose in life was one of the most frequently observed experiences for people with dementia. However, People with dementia and their caregivers reported a positive change in the understanding of their illness trajectory, and they reported an improvement in perceived self-actualization by participating in the social recreational programs. Both people with dementia and their caregivers indicated an improved capacity to actively contribute to self-care, family roles and responsibilities, as well as exploring other meaningful social activities outside of the ASDR programs. People with dementia and their caregivers were able to achieve self-understanding, leverage their potentials and regain their purpose in life:

‘(The program activities) give me something meaningful and purposeful to achieve.’ (CG6).

‘When they told me I had early onset of Alzheimer’s… I didn’t know anyone who had it. But coming to the programs give me the chance to see that there are other people who just get along fine in life. So nothing to get overly worried about… just focus on taking good care of myself.’ (PWD9)

Building resiliency: The educational components of the ASDR programs enabled the participants to strengthen their resilience through practicing effective coping strategies to manage the symptoms of their conditions. People with dementia indicated that program participation allowed them to become more resilient in facing the adversity of their lived experiences and illness trajectory of dementia:

‘(The programs) made us aware that we need to slow down… take it easy on certain things. Learning to cope and be strong’. (PWD7)

Caregivers discussed that program participation helped develop a positive attitude towards dealing with the symptoms of dementia. Caregivers stated that the programs made them feel more ‘Accepting of what’s going on.’ (CG2)

Improving physical and mental well-being through sensory stimulation

The multi-activity nature of ASDR programs that catered to both physical and psychological health of participants has resulted in an overall improvement in physical and mental well-being. Most of the social recreational programs involved a mild physical activity with the program participants, followed by a socialization component. Interview findings revealed that attending ASDR programs on a regular basis helped people with dementia and their caregivers to become more physically active through physical stimulation, including exercises and group walking. The socialization component of the program provided the people with dementia with the increased sensory stimulation related to brain exercises, along with the opportunity to socially engage in stimulating discussion to improve cognitive and emotional health.

‘(Through the program), more and more people are understanding that being physically active and socializing is really a good idea. The opportunities for socializing and interactions (during the program) helped motivate people to come out more often.’ (CG5)

The physical and mental stimulation were identified as a positive impact on the overall health and well-being of people with dementia and their caregivers: ‘These programs do make a difference… Making a big difference in my health and well-being. I don’t know what I’d do without it.’ (PWD10)

Increased awareness about dementia and related programs/services through education

Both people with dementia and their caregivers indicated that the public education helped to raise their awareness of ASDR programs and services, and how to live well with dementia. In particular, the educational components of ASDR programs allowed people with dementia and their caregivers to learn about symptoms management, and problem-solving approaches to deal with the challenges associated with dementia. This knowledge allowed people with dementia and their caregivers to develop an increased self-awareness and understanding about dementia.

‘(The programs) give you an insight about (your disease) … what’s going on and what to expect….’ (CG2).

‘(The program)…it taught me what to do and how to cope with the illness’ (PWD5).

Another important benefit of the social recreational programs was the utilization of technology as an educational tool. Using information communication technology such as computers and tablets as a tool to provide brain exercises for people with dementia. Participants described the positive experience of utilizing technology for cognitive training and socialization purposes: ‘He learns from these programs about how to use email; google for information, and play games such as mind games just to have his brain staying active through technologies…’ (CG9).

Program impact related to volunteers

Qualitative findings revealed how the volunteers contributed to achieving the greatest impact on people with dementia and their caregivers through their involvement in the social recreational programs. Analysis of volunteer interview identified three overarching themes that highlighted the benefits experienced by the volunteers and the program impact as a result of their active contributions: (1) Receiving Positive Rewards of Volunteerism; (2) Consolidating a Sense of Community; and (3) Raising Awareness about Living Well with Dementia.

Receiving positive rewards of volunteerism

Volunteers indicated that their motivation to engage in volunteerism in the field of dementia was due to their personal interests and desires to give back to the community. Through their dedication to volunteerism at ASDR, they developed a sense of personal satisfaction from their good deeds and received positive rewards by giving back to the community; developing knowledge, skills and competencies in dementia care; and achieving an increased sense of personal satisfaction.

Giving back to the community: Volunteers indicated that they were passionate about their active involvement in ASDR programs, and they viewed their volunteer contribution as a meaningful way of giving back to the community. In particular, they wanted to give back to the community organization because their loved ones had benefitted from ASDR programs in the past: ‘I’m trying to give back. We want them (clients) to reach out and we need to reach out too … It is a mutual relationship.’ (V2) Volunteers mentioned about the positive impact they bring to the social recreational programs in establishing increased social support network for their clients. Caregivers of people with dementia experienced a great deal of stress where their lives were consumed by caring for their partner or loved ones. Volunteers highlighted that their contributions in ASDR programs enabled the caregivers to have ‘some time for themselves’. Volunteers indicated that caregivers were provided with a positive caring environment where they did not have to be stressed about the safety of their loved ones, and they were surrounded by other caregivers who were going through the same issues.

Developing the knowledge, skills and competencies in dementia care: Volunteers indicated that one of the motivations of their volunteer work at ASDR was to develop the necessary knowledge, skills and competencies in dementia care to prepare themselves for future employment. Specifically, their volunteerism had an added benefit of changing their understanding about the lived experiences of people with dementia, and this has resulted in the transformation of their perspectives about life: ‘I volunteered to gain more knowledge and experiences to provide better care… But I think people should be a volunteer because it will change your perspectives about life for sure.’ (V8)

Achieving a sense of personal satisfaction: Volunteers indicated that their dedication and contributions at ASDR always made them feel satisfied and proud. They enjoyed helping the community organization, and the clients within the social recreational programs because they believed that they were making a significant difference in the lives of these individuals within the community: ‘I want to make a difference by speaking to a group of people to increase their awareness (about their illness); to engage them and get the support they need. This will help clients to better progress along the journey of dementia. That feels awesome to me.’ (V1)

Consolidating a sense of community

Volunteers described that they experienced a consolidated sense of community after volunteering in the ASDR programs. For example, they indicated that they have made meaningful connections with their clients by actively listening to their life stories or engaging in a discussion to exchange ideas. The volunteers further built a sense of community by leveraging the linking and referring of others who were impacted by dementia to access the ASDR programs for follow-up and support. The volunteers built a stronger sense of community with the clients within the ASDR programs by establishing new friendships and social bonding. Some volunteers indicated that they were able to better understand their client’s life stories due to their roles and connections with ASDR. Other volunteers described that they travelled from other regions to volunteer at ASDR in order to expand their geographical horizons and reach out to a new community to develop a new circle of care network.

‘I got to meet a whole bunch of different people. That’s amazing because they are new people who are not in my circle of friends. I have been able to meet people who have different life experiences. It’s been a really interesting experience.’ (V3)

Volunteers observed that the social aspects of ASDR programs allowed for the development of a circle of care community to be formed, as well as creating a safe and comfortable environment to develop social bonding. ‘The program creates a little community in which they belong. They are being accepted..It’s a place where they truly belong’ (V9). Similarly, volunteers identified that the programs helped their clients to become more engaged in the community through a positive social environment that would otherwise be impossible if they stayed at home.

‘It (Brainwave Cafe) served to provide an outing for people who would otherwise be sitting at home or retirement home or home with no interaction…Our clients looked forward to coming to our programs.’ (V7)

Raising awareness about living well with dementia

As a result of their volunteerism, many of the volunteers explained that they were able to raise awareness about living well with dementia, particularly about the impact of stigma in contributing to social isolation among people with dementia and their caregivers. Volunteers reported reduced stigma experienced by people with dementia and their caregivers following program participation: ‘They come to these events and they are not being judged in any way..they’ll come and just talk freely’ (V6). Additionally, volunteers indicated that ASDR programs facilitated participant’s awareness of their disease conditions by providing information about the warning signs; where to access help; availability and accessibility of different types of dementia support programs. Volunteers identified the importance of their involvement in delivering public education for their existing and future clients to help support the development of a dementia-friendly community. Specifically, the educational component of ASDR programs was identified to contribute to increasing social connectedness and generating increased interest in the utilization of appropriate community resources and dementia care programs.

Volunteers indicated that the increased understanding about the illness experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers enabled them to empathize with their clients to better understand their experiences from their frame of reference. Volunteers demonstrated an increased understanding about the importance of dementia care, as well as developing a greater appreciation of the invisible work of informal caregivers.

‘We must recognize that we are aging… our population is aging. I come to understand that I’m getting older and will be affected by this (dementia) one day. I hope the organization will become fully equipped by the time I get to this stage.’ (V5)

‘I have great admiration for the caregivers …Who are able to stand by their mate … people need to know that caregivers struggle through the day just like the people with dementia. They pull their hair out and they cry… they’re just bewildered.’ (V7).

Barriers and facilitators of Volunteer-based social recreational programs

The qualitative interviews revealed the facilitators and barriers to improve the volunteer-based social recreational programs for people with dementia and their caregivers to promote their sense of social connectedness. The interview findings revealed some challenges faced by the participants that limited their access and level of participation in the social recreational programs. The study findings also highlighted the facilitating factors that enhanced their willingness in program participation, as well as providing future suggestions and recommendations that could improve the quality of the programs to adequately address the needs of people with dementia and their caregivers.

Barriers and areas of improvement of programs

This study identified several challenges experienced by the clients that acted as barriers to their level of program participation. One of the most commonly reported barriers that resulted in their inability to fully engage in the program activities was the level of difficulty related to the physical exercises. Clients reported difficulties in practicing the physical exercises led by the facilitators during the social recreational programs. Program participants reported that the exercises were hard to follow as they were often too complicated, fast-paced, and older adults were not strong enough to perform the physical exercises as expected. Specifically, participants reported difficulties in following the program activities due to their limited physical mobility as a result of their disease conditions. Depending on the stage of dementia, their physical and cognitive functioning may impact their activity tolerance and ability to follow commands. These barriers may provide some explanation for the difference between PWD and caregiver responses to changes in the level of confidence, stress level, and pleasure in life following participation in ASDR programs with caregivers reporting more overall positive changes compared with people with dementia.

Another program barrier that was identified by the participants was the accessibility of social recreational programs. Transportation to and from the programs was an issue for some clients at the ASDR. In many cases, the caregiver reported not being able to take the people with dementia to the social recreational programs due to the lack of accessible transportation, while both the people with dementia and their caregivers were unable to drive. The program locations also presented as barriers to the participants when the venues were not within a geographically accessible distance. Program availability was identified to be another area of improvement related to program accessibility. Program participants reported that there was a lack of flexibility in the scheduling of some social recreational programs, and they often found themselves unable to choose from a variety of programs that were offered in different time/date of the week to accommodate the different scheduling needs of the participants. For instance, the program participants were unable to attend a session at a specific time due to conflicting schedule, and they were not able to attend the programs of their choice at all. Another barrier identified by the people with dementia was the lack of caregiver availability for having the time to bring them to the programs due to the multiple demands faced by the caregivers. Finally, people with dementia and their caregivers indicated that there was a need to increase their awareness about the availability of these social recreational programs through public education and promotional activities because the lack of awareness of these existing programs was reported as one major reason leading to their delayed access and utilization of ASDR programs and services.

Program strengths and facilitating factors

The interview findings revealed that one of the main facilitators of the social recreational programs that led to program success was the contributions of volunteers. The support provided from volunteers was identified to be an important strength that facilitated the successful implementation of ASDR programs. Program participants reported that volunteers provided significant contributions to the program through their effective facilitation skills and caring presence with the clients who needed extra support. Specifically, both people with dementia and their caregivers indicated that the volunteers were professional; highly skilled and trained in dementia care; and they were friendly, supportive, and encouraging. The qualities and attributes possessed by the volunteers allowed the participants to feel comfortable and confident to participate in the program activities. In addition to volunteer support, outreach and promotional activities were identified to the facilitating factors that positively improved program access and participation. For instance, public education can raise awareness about dementia care; address the concerns and stigma associated with the disease; promote the utilization of existing programs and resources at ASDR; and facilitating the creation of a dementia friendly environment. Promoting the social recreational programs through the word-of-mouth was identified to be an effective approach to spread the words to the general public about the programs and services available at ASDR. Raising awareness via online media was identified to be another facilitator in providing the information to the individuals who used the Internet to search for the available programs and resources that are suitable to them.

Recommendations for future program success

Study findings identified several recommendations suggested by people with dementia, their caregivers, and volunteers to address the barriers and challenges experienced by the program participants. One major barrier identified by the people with dementia was that their program attendance was highly dependent on the availability of their caregivers to bring them to the social recreational programs. Therefore, the program participants suggested that ASDR could consider developing a volunteer driver program where the volunteer driver would act as a driver and companion for people with dementia who would need support with commuting to and from the programs. Additionally, participants suggested the need for ASDR to develop a variety of social recreational programs during the day and evening. At the present time, majority of the programs were offered during the day, while some caregivers would prefer the availability of some evening programs to accommodate their scheduling needs. Another recommendation suggested by the people with dementia and their caregivers was the development of a mentorship program. The interview participants indicated that many of the social recreational programs included a scheduled time for socialization activities to help them establish new friendship and social bonding. However, some of the program participants experienced perceived discomfort in the participation of these social activities during the initial phase of the program. In order to better engage in the program’s social activities, people with dementia and their caregivers suggested that it would be helpful if ASDR would offer an initial mentor-mentee matching session where the mentor could provide the new members with helpful coaching, guidance and support in the development of new social network within the program. The participants also suggested the use of ‘Refer a Friend or Bring a Buddy’ approach to encourage the program participants to refer and bring someone they know to participate the social recreational programs. This approach will help promote the awareness of the program, as well as encouraging people with dementia and their caregivers to engage in social activities with their friends and loved ones during the program. In regard to the volunteer training, people with dementia and their caregivers suggested that an extended orientation and training provided to the volunteers prior to the start of the ASDR programs would be beneficial. Program participants noted a lack of confidence in some volunteer’s level of confidence in their facilitation skills during the initial phase of the program, but their skills and confidence improved as the program progressed. Therefore, it is critical to invest in the future development of volunteer training programs that would better equip the volunteers with the increased capacity to deliver effective social recreational programs for the people with dementia and their caregivers to promote their sense of social connectedness.

Discussion

New knowledge generated from our study findings demonstrated the positive impact of social recreational programs in promoting a sense of social connectedness for people with dementia and their caregivers. Previous literature revealed the benefits of social recreational programs including mindfulness, enjoyment, engagement, socialization, and personhood among people with dementia and their caregivers (Burnside et al., Citation2017). Our study findings further expanded these themes to include the development of social connectedness; building positive attitudes; improving physical and mental well-being; and increased awareness about living well with dementia. Our study findings underscored the importance of having ongoing funding support to facilitate the development of social recreational programs as an effective approach in improving the social connectedness of people with dementia. These programs are exemplars of potential recovery interventions targeted at supporting people with dementia to develop a greater sense of social connection in the community, as well as promoting their recovery from the negative health and emotional impact associated with their cognitive impairment (Sun, Biswas, et al., Citation2019).

Our current study findings are complementary to the existing literature by concluding that providing social support and recreational activities for both people with dementia and their caregivers can enhance the long-term development of relationship roles and responsibilities; facilitate open communication; and enable the caregivers to develop a sense of partnership that will promote the feelings of enjoyment and togetherness (Pahlavanzadeh et al., Citation2010; Roland & Chappell, Citation2015). Future research should continue to expand upon the understanding and utilization of social recreational programs and its associated benefits by people with dementia and their caregivers. The causes of loneliness and social isolation for people with dementia are inter-related, and new research is needed to provide evidence to inform the future development of intervention programs that address the barriers associated with the multifactorial causes (Poey et al., Citation2017; Victor et al., Citation2021). Existing literature suggests that stigma increases the likelihood of social isolation among people with dementia and their caregivers by acting as barriers to the utilization of available services that will reduce their health burden associated with the disease (Werner et al., Citation2012). Our current study findings indicated that building positive attitude towards living well with dementia were identified to be a notable impact of social recreational programs, while one of these positive attitudes is reduced stigmatization. People with dementia and caregivers identified that the programs enabled them to increase the understanding of their diagnosis and develop a positive attitude about their illness experience, while allowing them to practice effective coping strategies for the management of their disease conditions.

Our study examined how volunteers contributed to achieve the greatest impact on the health and well-being of people with dementia and their caregivers through social recreational programs. The findings highlighted the critical role of volunteer-based social recreational programs in helping the people with dementia and their caregivers to combat the negative effects of social isolation in the community. Our current study findings are complementary to the existing literature to indicate that volunteers could provide people with dementia with many positive physical and mental health benefits, including building meaningful relationships and social connections, as well as reducing the societal stigma associated with dementia (Costa Guerra et al., Citation2012). Volunteer-led programs in raising awareness about Living Well with Dementia are examples of important public education initiatives to help reduce the existing stigma surrounding the disease. Volunteers can play an important role in educating the dementia communities about the services available to them, which is a facilitating factor in decreasing the social isolation experienced by people with dementia and their caregivers (Gaugler et al., Citation2019).

Future research will benefit from conducting exit interviews with those program participants who dropped out from the social recreational programs to examine the rationale for discontinuing their program participation. Longitudinal research could also be conducted to explore the long-term impact of program participation and the changes needed to address the ongoing needs of the program users over time. These study findings may have implications to community agencies, service clubs, churches and local businesses to better understand the unique needs of people with dementia and their caregivers, as well as identifying the education and training that are necessary for their volunteers to address the challenges of social isolation among people with dementia. Through reducing social isolation, community volunteers can support people with dementia into the road of recovery with the goal of enabling them to feel empowered in actively participating and being socially engaged in the community.

This research study holds a few limitations. Our current study sample was predominately comprised of participants with Caucasian ethnic background, and individuals who are currently accessing dementia care programs. However, literature revealed that a reduced level of participation is observed in the dementia care and support programs among immigrants and refugees compared to their nonimmigrant counterparts (Sun, Clarke, et al., Citation2019). Therefore, there is an urgent need for ongoing evaluation to explore whether the existing social recreational programs are culturally appropriate in supporting the needs of people with dementia and their caregivers, as well as raising awareness about these programs and services to promote increased access and utilization by the program participants from diverse cultural background.

It should be noted that there could be self-reported bias when participants reported their perceived changes after program participation. Also, the self-reported survey is not a validated measurement tool, and the reported findings should be interpretated as descriptive rather than correlational results. Research involving qualitative interviews to collect data about sensitive topics have the tendency to be affected by external bias caused by social desirability (Althubaiti, Citation2016). Therefore, social desirability bias from the volunteers, people with dementia and caregivers may have influenced the reports of their personal experiences about the social recreational programs. Another limitation of this study is the need to further expand our understanding about the lived experiences of people with dementia in later stages, as well as the perspectives of non-English speaking participants to explore their cultural needs. Finally, the study data were only collected from three types of social recreational programs, and the participants were limited to those individuals who were accessing ASDR programs. Future research will benefit from expanding the program evaluation to explore the effectiveness of additional ASDR programs, and other dementia care programs in diverse settings and geographical locations.

Conclusion

In summary, this research employed an exploratory qualitative descriptive approach to explore the study participants’ lived experiences of the ASDR programs within ‘Living Well with Dementia’ project. Our study findings highlighted the impact of social recreational programs on people with dementia, caregivers and volunteers in the promotion of social connectedness, as well as the examination of barriers and facilitators to identify opportunities for the future improvement of community-based programs that would benefit the dementia populations. The study findings revealed that the project ‘Living Well with Dementia’ has been able to successfully combat the impact of social isolation through its volunteer-led social recreational programs for people with dementia and their caregivers living in the community of Durham Region of Ontario, Canada. The program impact of ASDR were not only limited to benefit the people with dementia and their caregivers, but it also extended to underscore the critical roles of volunteers who contributed to the success of these programs. Future directions of this evaluation project would be to identify the opportunities to address the current gaps in services and to strengthen the existing social recreational programs using evidence-based practices and client-centered approaches. Continued efforts need to be made to recruit, train and build a competent volunteer workforce with the capacity to support the development of dementia-friendly communities.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (65.6 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alpert, P. T. (2017). Self-perception of social isolation and loneliness in older adults. Home Health Care Management & Practice, 29(4), 249–252. https://doi.org/10.1177/1084822317728265

- Althubaiti, A. (2016). Information bias in health research: Definition, pitfalls, and adjustment methods. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 9, 211–217. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S104807

- Alzheimer Society of Canada (2020a). Minds in motion. Alzheimer Society. https://alzheimer.ca/on/en/help-support/programs-services/minds-in-motion#The_benefits_of_Minds_in_Motion®

- Alzheimer Society of Canada (2020b). Normal aging vs dementia. Alzheimer Society. https://alzheimer.ca/en/about-dementia/do-i-have-dementia/differences-between-normal-aging-dementia

- Alzheimer Society of Durham Region (2020a). About dementia. Alzheimer Society. https://alzheimer.ca/en/about-dementia

- Alzheimer Society of Durham Region (2020b). Changes in mood and behaviour. Alzheimer Society. https://alzheimer.ca/en/help-support/im-caring-person-living-dementia/understanding-symptoms/changes-mood-behaviour

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2018). 2018 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, 14(3), 367–429. https://www.alz.org/media/homeoffice/facts%20and%20figures/facts-and-figures.pdf

- Biordi, D. L., Nicholson, N. R. (2013). Social isolation. In Problems and issues of social isolation (pp. 85–111). Jones and Bartlett Publishers. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/67b7/cf4a9d1aeacc000a11f617a4dda83e396256.pdf

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- British Columbia Ministry of Health (2004). Social isolation among seniors: An emerging issue. Children’s Women’s and Seniors Health Branch. https://www.health.gov.bc.ca/library/publications/year/2004/Social_Isolation_Among_Seniors.pdf

- Brodaty, H., & Donkin, M. (2009). Family caregivers of people with dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment, 11(2), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.31887/dcns.2009.11.2/hbrodaty

- Burnside, L. D., Knecht, M. J., Hopley, E. K., & Logsdon, R. G. (2017). Here:Now - Conceptual model of the impact of an experiential arts program on persons with dementia and their care partners. Dementia (London, England), 16(1), 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301215577220

- C., Guerra, S. R., Demain, S. H., Figueiredo, D. P., & Marques De Sousa, L. X. (2012). Being a volunteer: Motivations, fears, and benefits of volunteering in an intervention program for people with dementia and their families. Activities, Adaptation & Aging, 36(1), 55–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/01924788.2011.647538

- Cammisuli, D. M., Danti, S., Bosinelli, F., & Cipriani, G. (2016). Non-pharmacological interventions for people with alzheimer’s disease: A critical review of the scientific literature from the last ten years. European Geriatric Medicine, 7(1), 57–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurger.2016.01.002

- Cattan, M., White, M., Bond, J., & Learmouth, A. (2005). Preventing social isolation and loneliness among older people: A systematic review of health promotion interventions. Ageing and Society, 25(01), 41–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X04002594

- Choi, H., Irwin, M. R., & Cho, H. J. (2015). Impact of social isolation on behavioral health in elderly: Systematic review. World Journal of Psychiatry, 5(4), 432–438. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v5.i4.432

- De Jong Gierveld, J., & Van Tilburg, T. (2010). The de Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: Tested on data from 7 countries in the un generations and gender surveys. European Journal of Ageing, 7(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-010-0144-6

- Gaugler, J. E., Bustamante, G., Rosebush, C., Schoonover, J., Jenkins, R., Bauer, N., Beardsley, L., & Rowe, L. (2019). The porchlight project: Collaborating to enhance the dementia capability of community-based volunteers. Innovation in Aging, 3(Supplement_1), S363–S363. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igz038.1326

- He, W., Goodkind, D., Kowal, P. (2016). An aging world: 2015 [International Population Reports]. U.S. Government Publishing Office. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2016/demo/p95-16-1.pdf

- Kovaleva, M., Spangler, S., Clevenger, C., & Hepburn, K. (2018). Chronic stress, social isolation, and perceived loneliness in dementia caregivers. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 56(10), 36–43. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20180329-04

- Moody, E., & Phinney, A. (2012). A community-engaged art program for older people: Fostering social inclusion. Canadian Journal on Aging = La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement, 31(1), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980811000596

- National Institute on Aging (2019, April 23). Social isolation, loneliness in older people pose health risks. https://www.nia.nih.gov/news/social-isolation-loneliness-older-people-pose-health-risks

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long Term Care (MOHLTC). (2016). Developing Ontario’s dementia strategy: A discussion paper. Queen’s Printer for Ontario. https://files.ontario.ca/developing_ontarios_dementia_strategy_-_a_discussion_paper_2016-09-21.pdf

- Pahlavanzadeh, S., Heidari, F. G., Maghsudi, J., Ghazavi, Z., & Samandari, S. (2010). The effects of family education program on the caregiver burden of families of elderly with dementia disorders. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 15(3), 102–108. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21589771/

- Poey, J. L., Burr, J. A., & Roberts, J. S. (2017). Social connectedness, perceived isolation, and dementia: Does the social environment moderate the relationship between genetic risk and cognitive well-being?The Gerontologist, 57(6), 1031–1040. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw154

- Roland, K. P., & Chappell, N. L. (2015). Meaningful activity for persons with dementia: family caregiver perspectives. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 30(6), 559–568. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317515576389

- Singer, C. (2018). Health effects of social isolation and loneliness. Journal of Aging Life Care, 28(1), 4–8. https://www.aginglifecare.org/ALCA_Web_Docs/journal/ALCA%20Journal%20Spg18_FINAL.pdf

- Sun, W., Biswas, S., Dacanay, M., & Zou, P. (2019). An examination of factors influencing equitable access to dementia care and support programs among migrants and refugees living with dementia: A literature review. In D. Larrivee (Ed.), Redirecting alzheimer strategy - tracing memory loss to self pathology (pp. 1–17). IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.84858

- Sun, W., Clarke, S.-L., Madahey, H., & Zou, P. (2019). Recovery intervention to promote social connectedness through social recreational programs for persons with dementia: A critical analysis. In G. Ashraf (Ed.), Advances in dementia research (pp. 1–19). IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.83784

- The National Seniors Council (2014). Report on the social isolation of seniors. Government of Canada. https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/nsc-cna/documents/pdf/policy-and-program-development/publications-reports/2014/Report_on_the_Social_Isolation_of_Seniors.pdf

- Victor, C. R., Rippon, I., Quinn, C., Nelis, S. M., Martyr, A., Hart, N., Lamont, R., & Clare, L. (2021). The prevalence and predictors of loneliness in caregivers of people with dementia: Findings from the ideal programme. Aging & Mental Health, 25(7), 1232–1238. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1753014

- Werner, P., Mittelman, M. S., Goldstein, D., & Heinik, J. (2012). Family stigma and caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. The Gerontologist, 52(1), 89–97. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnr117

- Wong, S. L., Gilmour, H., Ramage-Morin, P. L. (2016). Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in Canada [Health Report]. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/82-003-x/2016005/article/14613-eng.htm

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2020, September 21). Dementia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- Zucchella, C., Sinforiani, E., Tamburin, S., Federico, A., Mantovani, E., Bernini, S., Casale, R., & Bartolo, M. (2018). The multidisciplinary approach to Alzheimer’s disease and dementia. A narrative review of non-pharmacological treatment. Frontiers in Neurology, 9, 1058. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2018.01058

Appendix A

Table A1. Illustrative Quotes: Developing Social Connectedness in the Community.

Appendix B:

Interview guide

Interview Guide (Persons living with Dementia)

Introduction

Thank you for meeting with me today. My name is XXX, and I would like to talk to you about your experiences of the Alzheimer Society of Durham Region programs. The interview should take about an hour. With your permission, I will be audio recording the session so I don’t miss out on any of your answers to the questions. Even though I’ll be taking notes during the interview, I won’t be able to write everything down. Because we’ll be audio recorded, please make sure to speak up so we don’t miss anything when we are putting your responses unto the paper copy. Your answers will be kept confidential. They only will be shared with research team members and we will make sure that whatever information we include in our report does not identify you in any way. You do not have to talk about anything you don’t want to and you may end the interview at any time. Here is a consent form that provides the details of the study. I will read through each part of this consent with you to ensure you understand before you sign this form. You will be provided a copy of this signed consent form. If you have any questions, please feel free to ask me at any time.

Before we begin the interview, I am going to ask you a few questions to assist us with understanding who you are and what brings you to the Alzheimer Society programs (Demographic Questionnaire).

Interview Prompt Questions

Tell me little about why you agreed to this interview.

Tell me how you became aware of the Alzheimer Society programs.

What programs are you attending at the Alzheimer Society?

Prior to coming to the program(s), what did your social life look like and what does it look like now (ask about connection to others, resources etc.)?

What part of the program did you enjoy the most (find most helpful) and why?

What part of the program did you least enjoy (was least helpful) and why?

Is there anything that makes it difficult to attend the program(s) at the Alzheimer Society?

Is there anything that makes it easier to attend the program(s) at the Alzheimer Society?

How has the program changed your life, if at all? (e.g. with partners, friends, other family, community)

Is there anything that you might change about the programs – e.g. take out or add?

Is there anything else you would like to say that I haven’t asked about?

Conclusion:

(End audio recording.) Okay, I’ll be making this audio recording into a printed record, which I will review with you to ensure we were able to record your answers accurately (if you would like to do this). This data will be used to develop a report on the research findings. If you’re interested in remaining updated with this study, feel free to get in touch with me using the contact information provided. We are keeping a list of people who are interested and will present the findings to them.

Thank you so much for your time!

Interview Guide (Informal Caregiver)

Introduction

Thank you for meeting with me today. My name is XXX, and I would like to talk to you about your experiences of the Alzheimer Society of Durham Region programs. The interview should take about an hour. With your permission, I will be audio recording the session so I don’t miss out on any of your responses. Even though I’ll be taking notes during the interview, I won’t be able to write everything down. Because we’ll be audio recorded, please make sure to speak up so we don’t miss anything when transcribing your responses. Your responses will be kept confidential. Your responses will only be shared with research team members and we will make sure that whatever information we include in our report does not identify you in any way. You do not have to talk about anything you don’t want to and you may end the interview at any time. Here is a consent form that elaborates on the details of the study. Please read through it carefully and sign at the bottom for your free informed consent to participate in this study. You will be provided a copy of this signed consent form. If you have any questions, please feel free to ask me.

Before we begin the interview, I am going to ask you a few questions to assist us with understanding who you are and what brings the person you provide care for (or yourself) to the Alzheimer Society programs.

Interview Prompt Questions

Tell me a little about what prompted you to agree to this interview.

Tell me a little about how you became aware of the Alzheimer Society programs.

What program(s) are you or the person you provide care for attending at the Alzheimer Society and when did begin to attend those programs begin? (could be one program or more)

Prior to attending the program(s), what did your social life look like and what does it look like now (ask about connection to others and resources etc.)?

What program(s) or aspects of the program(s) have you found most helpful and why?

What program(s) or aspects of the program(s) have you found least helpful and why?

What are those factors that challenge the ability for the person you provide care for and/or yourself to attend the program(s) at the Alzheimer Society? (e.g. timing of the program, location, transportation, cost etc.)

What are those factors that make it easier for you to access the program(s) at the Alzheimer Society?

How has the program impacted your life in relation to connection to others and/or resources, if at all? (1) your relationship with your partner and/or extended family and friends was improved after participating in the program; (2) forming friendships; (3) mutual peer support from group members; (4) feeling inclined to participate in other community activities?

Is there anything that prevents you from using these programs?

Is there anything that you might change about the programs – additions, deletions etc.?

If at all, in what ways have the program volunteers enhanced your participation experience?

Can you tell me about your experience with mobile devices; which ones do you use and in what way do you use them? How would you describe your ability to be connected to resources and others through the use of these devices? If you don’t use devices, can you tell me what keeps you from doing so.

Is there anything else you would like to add that I haven’t asked about?

Interview Guide (Volunteers)

Introduction

Thank you for meeting with me today. My name is XXX, and I would like to talk to you about your experiences of the Alzheimer Society of Durham Region programs. The interview should take about an hour. With your permission, I will be audio recording the session so I don’t miss out on any of your responses. Even though I’ll be taking notes during the interview, I won’t be able to write everything down. Because we’ll be audio recorded, please make sure to speak up so we don’t miss anything when transcribing your responses. Your responses will be kept confidential. Your responses will only be shared with research team members and we will make sure that whatever information we include in our report does not identify you in any way. You do not have to talk about anything you don’t want to and you may end the interview at any time. Here is a consent form that elaborates on the details of the study. Please read through it carefully and sign at the bottom for your free informed consent to participate in this study. You will be provided a copy of this signed consent form. If you have any questions, please feel free to ask me.

Before we begin the interview, I am going to ask you a few questions to assist us with understanding who you are and what brings you to the work at the Alzheimer Society.

Interview Prompt Questions

Tell me a little about what prompted you to agree to this interview.

Tell me a little about how you became a volunteer with the Alzheimer Society(AS) programs.

What programs have you been involved with at the Alzheimer Society and what is your role?

What is the program or are the programs you have been involved in designed to do?

What programs or aspects of the program(s)you have been involved in have been most helpful to those accessing them and why do you think that is the case?

What programs or aspects of the program(s)you have been involved in have been least helpful to those accessing them and why do you think that is the case?

What are those factors that challenge people in relation to access to the program(s) at the Alzheimer Society?

What are those factors that enable people to access the program(s) at the Alzheimer Society?

What would you add to the programming to assist further with breaking social isolation? and What would you change, if anything?

What benefits have you experienced personally as a volunteer with the AS?

Can you tell me a little about what your connection to the community has been since being a volunteer?

What is your understanding of the needs of those living with dementia as a result of volunteering with the AS? Can you describe the ways in which experience has changed your understanding, if at all?

What changes, if any, would you make to the program to encourage greater interaction amongst the persons living with dementia and/or caregivers within the program?

What changes, if any, are you aware of that have occurred for persons living with dementia and/or caregivers in terms of their social interactions and/or connectedness as a consequence this program?

Is there anything else you would like to add that I haven’t asked about?

Appendix C:

Demographic questionnaire

Living Well with Dementia: Demographic and Well-being Questionnaire

Please tell us the following information about yourself:

Please check one of the following categories that applies to you

I am aperson living with dementia caregiver volunteer

What is your name (please print): ______________________________

What is your age: _____

What is your gender:Male Female

In which city or town do you live? ______________________

What is your educational level?

No formal education

Grade school

High school

College/University

7. What is your marital status?

Married/common-law

Separated/divorced

Widowed

Never married

8. What is your current living arrangement?

I live alone

I live with my spouse