Abstract

Objectives: Personality can influence older adults’ health and quality of life. However, the pathways are relatively less examined. This study aimed to understand the mediating effect of resilience in the relationship between two personality traits—neuroticism and extraversion—and Hong Kong Chinese older adults’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL). Whether such effect varied across older adults in different financial conditions were also examined.

Method: A purposive non-probability sample of 253 Hong Kong Chinese older adults aged 60 and above was recruited for a face-to-face questionnaire survey. Neuroticism and extraversion were measured using the subscales form the Big Five Inventory (BFI). Resilience was measured by the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). HRQoL was measured by the short-form 8 (SF- 8). Path analysis was conducted to examine the relationship between key variables. Multi-group path analysis was also performed to investigate whether the pathways differed by financial status. Indirect effects were computed in the path analyses to detect the mediatory role of resilience between personalities and HRQoL.

Results: The findings included that after controlling for confounders, neuroticism, but not extraversion was significantly associated with HRQoL. The relationships were mediated by resilience. Moreover, the mediating role of resilience is more pronounced among the participants who live in a financially poor or fair condition, comparing to their wealthier peers.

Conclusion: This study confirmed the important role of personality in shaping older adults’ resilience and quality of life. Personality should be kept in mind in the identification of potential vulnerable groups for interventions, especially those in financial hardships who may face double disadvantages.

Introduction

Population aging across the globe has posed great challenges for the health and elderly care systems. To gain a better understanding of factors and pathways influencing older people’s health and well-being is helpful for designing and implementing effective programs and interventions. Among all the factors of older people’s health, personality is relatively under-examined, even though that it accounts for as much as 40% of overall Health-related quality of life (HRQoL), according to a meta-analytical study (Huang et al., Citation2017). Even less known is the underlying mechanism in the personality-health relationship.

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) is a multi-dimensional and cross-disciplinary health outcome, measuring an individual’s physical health, mental health, and social functioning. It has been increasingly used to represent the overall health condition of the aging population (Thompson et al., Citation2012). A systematic review reviewing 76 English literature has found that personality can be either directly linked to HRQoL or indirectly via mechanisms such as social support and coping resources (Huang et al., Citation2017). The present study aims to understand the relationship between two dimensions of personality, specifically extraversion and neuroticism, and HRQoL of Hong Kong Chinese older adults. Moreover, we aimed to test the role of resilience, as a critical coping resource for older adults in mediating the personality-health relationship. The moderators in the direct and indirect relationships were also examined.

Extraversion, neuroticism, and HRQoL

In the literature of personality and health, extraversion and neuroticism are the two personality traits that have been most frequently examined. Neuroticism represents a tendency to react in a maladaptive and excessive way under stressful situations. It is usually companied by negative affect such as anxiety, irritation, helplessness, and a perception that the world is dangerous and threatening whereas the self is incapable to cope with adversity (Barlow et al., Citation2014; McHugh & Lawlor, Citation2012). By contrast, extraversion is characterized by positive thinking and emotions, minimal self-doubt when facing problems, and higher level of sociality.

Empirical studies have found that a higher level of neuroticism is negatively correlated with older adults’ HRQOL, and the direction is the opposite for extraversion (Chapman et al., Citation2006, Citation2007; Duberstein et al., Citation2003). The direct relationship between personality and HRQoL can be understood by the framework of trait theory, which suggests the individual differences in emotional reactivity and information processing (Huang et al., Citation2017). Specifically, extraverts react more strongly to positive stimuli and neurotic are more reactive to unpleasant stimuli (Diener et al., Citation2003; Huang et al., Citation2017). Extraverts have higher levels of energy and vitality; therefore, they may rate their health more positively. By contrast, neuroticism is often related to pessimistic views of one’s heath conditions (Duberstein et al., Citation2003).

Resilience as a mediator between the relationship of extraversion, neuroticism, and HRQoL

In addition to a direct relationship, personality can also influence HRQoL indirectly. Stress and coping resources are one of the multiple mechanisms developed by Ferguson (Citation2013) to explain how personality can influence health. According to cognitive behavior theory, personality can influence an individual’s coping styles and behaviors may result in different levels of resilience. Resilience represents the stress coping ability and a skill of an individual to bounce back and maintain physical and psychosocial functions when facing stress and adversity (Lamond et al., Citation2008; Luthar et al., Citation2000). Resilience can be influenced by both individual and societal factors. For instance, studies have found that increased social support was associated with a higher level of resilience among older population (Li et al., Citation2015). It is an important psychosocial coping source for older adults and closely related to older adults’ HRQoL (Lau et al., Citation2018; MacLeod et al., Citation2016; Wu et al., Citation2018; Yazdi-Ravandi et al., Citation2013).

An individual’s resilience is influenced by the combination of personality and the environment (Vyas & Dillahunt, Citation2017). Many previous researchers from different disciplines have linked individuals’ personality and resilience (Eley et al., Citation2013). A recent meta-analysis showed that neuroticism is negatively correlated with resilience (r = − 0.46) and extraversion is positively related to resilience (r = 0.42) (Oshio et al., Citation2018). An individual tends to cope in a way concordant with their personality (Diener et al., Citation2003; Huang et al., Citation2017). For instance, a study among Chinese empty-nested older adults found that, extraverts may view stressful events as opportunities and challenges, and adopt a more proactive way to cope. By contrast, people with a high level of neuroticism may lead to passive and more negative coping (Su et al., Citation2018). Older people’s resilience can be also contributed by other factors, such as social network and activity engagement Lamond et al. (Citation2008). Extravert older adults, who are more socialized, tend to have a higher level of social network (Chapman et al., Citation2006, Citation2007; Duberstein et al., Citation2003), and activity participation (Lai & Qin, Citation2018) that can improve older adults’ resilience.

Financial status as a moderator

While personality reflects an individual inner capacity, external factors and resources, such as socioeconomic status (SES), can also have impacts on older people’s resilience and HRQoL (Diener et al., Citation2003; Vyas & Dillahunt, Citation2017). For instance, a study among 1756 people aged 60 to 64 have shown that respondents with higher SES score higher in the spectrum of resilience (Cosco et al., Citation2018). Financial status is an essential indicator of one’s socioeconomic status. It has been found as one of the most important predictors of older adults’ resilience in recovering from adversities (Bennett et al., Citation2016; Stephens et al., Citation2015), and directly influences their HRQoL (Kale & Carroll, Citation2016; Zafar et al., Citation2015). People with higher SES may have fewer chances to encounter difficulties related to later-life poverty, and more resources and capacities to cope with stressful life events. They are also more likely to adopt healthy behaviors that may contribute to a higher level of HRQoL in later life (Adler & Newman, Citation2002; Lago et al., Citation2018; Pampel et al., Citation2010).

In addition to that personality and SES can influence people’s health and well-being separately, previous studies have found that personality and socioeconomic status can interact with each other to influence older adults’ longevity (Chapman et al., Citation2010). According to the vulnerability model and selective vulnerability hypothesis, a low SES may amplify the risks of adverse outcomes related to vulnerable personality. For instance, those with lower SES and vulnerable personality features such as neuroticism may have more health problems (Chapman et al., Citation2011). For instance, based on 513 French older adults, the negative relationship between neuroticism and physical functioning is only significant among those with lower education, and having a higher education can diminish the risk of neuroticism (Jaconelli et al., Citation2013). Therefore, a good financial condition may act as a protective factor against the negative influence of neuroticism on resilience and HRQoL. On the other hand, less favorable financial status may compromise the positive influence of extraversion.

Research gaps and the present study

There are several research gaps in the literature. First, as summarized by the evidence synthesis conducted by Huang et al. (Citation2017) including two studies among Chinese population, studies on the influence of personality on older adults mostly focused on subjective well-being, mortality, and outcomes related to specific diseases (Gomez et al., Citation2012; Wilson et al., Citation2005), instead of HRQoL. Second, the relationship between personality traits, especially extraversion and neuroticism, and older adults’ HRQoL, the mechanisms remain empirically under-examined. Previous studies have explored the mediatory role of resilience in the relationship between personality and health, but they are mostly focusing on at-risk adolescents or college students (Lü et al., Citation2014; Shi et al., Citation2015a). Third, fewer studies have examined the interaction between personality and socioeconomic status of older adults in shaping their resilience and HRQoL.

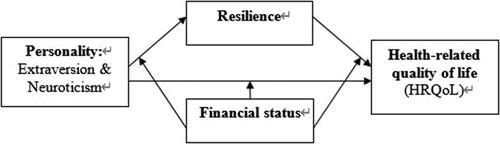

To fill these gaps, this study aimed to examine the relationship between extraversion, neuroticism, resilience and HRQoL, and how the relationships vary across older adults in different financial status, using the older Chinese as the target participants. The proposed framework is illustrated in . The hypotheses of this study included: (1) Older adults’ HRQoL is positively related to extraversion and negatively related to neuroticism. (2) Resilience significantly mediates the relationship between extraversion and HRQoL, and neuroticism and HRQoL. (3) The relationship between personality, resilience and HRQoL is moderated by older adults’ financial status.

Figure 1. Older adults’ HRQoL is hypothesized to positively related to extraversion and negatively related to neuroticism. Resilience is hypothesized to significantly mediate the relationship between extraversion and HRQoL, and neuroticism and HRQoL. Older adults’ financial status is hypothesized to be a moderator moderate the relationship between personality, resilience and HRQoL.

Methods

Data collection and sampling

Hong Kong Chinese older adults are the population of interest in this study. Hong Kong is one of the rapidest aging cities in the world and has one of the longest life expectancies in the world. In 2018, 17.9% of Hong Kong population were aged 65 and above, and the proportion will go up to 30% in 2033. Moreover, Hong Kong faces a serious elderly poverty issue that almost one in every three older people aged 65 and above are living in poverty (Census & Statistics Department, 2018), raising great concern over quality of life and health inequality. Therefore, it is important to examine whether the factors influencing older adults’ health vary across groups in different financial status.

We recruited the participants via the help of local NGOs and agencies starting from January 2018 via a convenient sampling approach. A total 253 participants, 84 males and 169 females, completed the study. Hong Kong Chinese older adults aged 60 and above and have not been previously diagnosed with cognitive impairment were eligible to participate. Participants with hearing or visual impairment were excluded from the study. The participants were invited to visit the university and filled in a questionnaire with the assistance of a research assistant. It took around 20 to 30 min to complete the questionnaire. The ethical approval was obtained from the Human Subjects Ethics Application System of the authors’ university (HSEARS20180110001).

Measurements

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was measured by the Short Form-8 (SF-8), which includes eight items measuring overall health, physical functioning capacity, physical or difficulties with daily work due to physical pain, bodily pain, vitality, social functioning, mental health or emotional problems, and emotional or absence from daily activities due to emotional problems (Yiengprugsawan et al., Citation2014). The Cronbach’s Alpha is 0.89, indicating a satisfactory internal consistency. We adopted the summary score of the eight items, ranging from 6 to 42, and a higher score indicates a higher health-related quality of life.

Extraversion and neuroticism were measured by the sub-scales of extraversion and neuroticism of The Big Five Inventory (BFI), respectively (John & Srivastava, Citation1999). Each sub-scale consists of eight items and the participants indicated their agreement with statements regarding whether they are someone like such as” is talkative” and” is depressed, blue” on a 5-point scale (0 = disagree strongly, 1 = disagree a little, 2 = neither agree nor disagree, 3 = agree a little, 4 = agree strongly). The Chinese version has been validated and adopted in previous studies with good internal consistency (Shi et al., Citation2015b; Lai & Qin, Citation2018). The Cronbach’s alpha values were 0.73 and 0.8 respectively, indicating good internal consistency. Higher overall scores of each sub-scale (ranging from 0 − 32) indicate a higher level of extraversion and neuroticism, respectively.

Resilience was measured by the 10-item Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) (Connor & Davidson, Citation2003). Participants indicated the frequency of them coping and recovering from stressful events on a 5-point scale (0 = Not true at all, 1 = Rarely true, 2 = Sometimes true, 3 = Often true, 4 = True nearly all the time). The scale has been widely adopted and validated among Chinese population (Wang et al., Citation2010; Yu et al., Citation2011). The Cronbach’s Alpha is 0.9 indicating a satisfactory internal consistency. The total score ranges from 0 to 40 and a higher score indicates a higher level of resilience.

Financial status was measured by a single-item question for the participant to self-evaluate their financial condition. The answers included 1 = Very good, 2 = good, 3 = fair, 4 = poor. The answers were further recoded to a dummy variable (0 = fair or poor, 1 = good or very good). Subjective economic status has been found to be a significant factor of health and well-being via multiple mechanisms (Cheng et al., Citation2002). The single-item measurement of subjective economic condition has been previously adopted in other studies among Hong Kong older population (Lai et al., Citation2020).

Other variables for controlling included age (in years), gender (female = 0, male = 1), marital status (0 = non-married, 1 = married), education (0 = lower than middle school, 1 = middle school, 2 = higher than middle school), living arrangement (0 = not living alone, 1 = living alone), caregiving status (0 = No, 1 = Yes), frequency of technology use (continuous, a composite score of frequencies using computers or laptops for various functions), and amount of physical activity (minutes per week). These variables have been found to be associated with HRQoL as well. Specifically, past studies have found age and gender differences in HRQoL (Etxeberria et al., Citation2019). Marital status and living arrangement are closely related to family support and caregiving roles, and therefore will influence older adults’ health and well-being (Feng et al., Citation2014). Previous studies also have found that Internet use and physical activity are both common activities participated by older adults and have significant associations with their wellness (Li & Zhou, Citation2021).

Data analysis

Bivariate descriptive analysis was first conducted to compare the participants from different financial conditions. Path analyses were conducted to examine the relationship between extraversion, neuroticism, resilience and HRQoL. The skewness of the four key variables were all smaller than 2, which indicates that they in general fit for a normal distribution. Indirect effects were computed to detect potential mediatory role of resilience. Before the path analysis, we computed the bivariate correlational matrix. The path analyses only included the significant (p < 0.05) or marginally significant (p < 0.2) correlations. We adopt several indices to indicate a good model fit: comparative fit index (CFI, >0.95), the goodness of fit index (GFI, >0.95), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA, <0.06), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR, <0.08) (Hooper, Coughlan, & Mullen, 2008). Multi-group path analysis was also performed to test whether the pathways differed by financial status. We first computed an unconstrained model wherein all parameters were allowed to vary freely across two different financial groups. We then performed a constrained model in which all the structural coefficients were set to be invariant across groups. A significant decrease in model fit from model 1 to model 2, indicate that there were significant group differences between the paths. RStudio was adopted for the whole data analysis.

Results

Sample characteristics

As shown in , the mean age of the participants was 65 years old (SD = 3.79). Most of the participants (64.8%) were married. Around 75% of them finished middle school or a higher level of education. 17% of them lived alone, and 24.9% of them had been caregivers over the past year. According to chi2 tests or t-tests, participants in good/very good financial status had a higher education level, more frequent technology use, less neuroticism, more extraversion, more resilience, and a higher level of HRQoL.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the sample (N = 253).

Results of path analyses

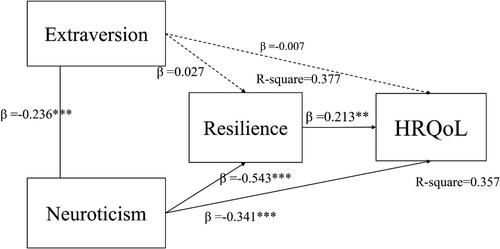

We first performed the path analysis among the total sample, which has shown an excellent model fit (CFI = 1.000, TLI = 0.999; RMSEA = 0.004; SRMR = 0.036) (). Neuroticism was significantly associated with resilience (β = −0.543, p < 0.001) and HRQoL (β = −0.341, p < 0.001). However, there was no significant associations between extraversion and either resilience or HRQoL. Resilience had a significant positive relationship with HRQoL (β = 0.213, p < 0.001). The R-square of resilience was 0.357 and based on the rule developed by Ranatunga et al. (Citation2020), with power being 0.8 and maximum number of arrows pointing at a construct being 10, the sample size required was smaller than 91. Therefore, with a sample size of 253, our analysis has been able to achieve a satisfactory power.

We also computed the mediatory role of resilience. The results showed that resilience only mediated the relationship between neuroticism and HRQoL (β=-0.125, p = 0.001), but not between extraversion and HRQoL. shows the direct and indirect effects between the key variables.

Table 2. Direct and indirect effects between neuroticism/extraversion and HRQoL among subsamples stratified by financial status.

Multi-group path analysis: moderating role of financial status

We conducted a multiple-group path analysis to test whether the pathways differed by financial status. The fully unconstrained path model provided a good model fit to the data (CFI = 1.000, TLI = 1.029; RMSEA = 0.000; SRMR = 0.048). A constraining model showed a less satisfactory model fit than the unconstrained model, which indicates that there were significant differences between financially rich and poor groups.

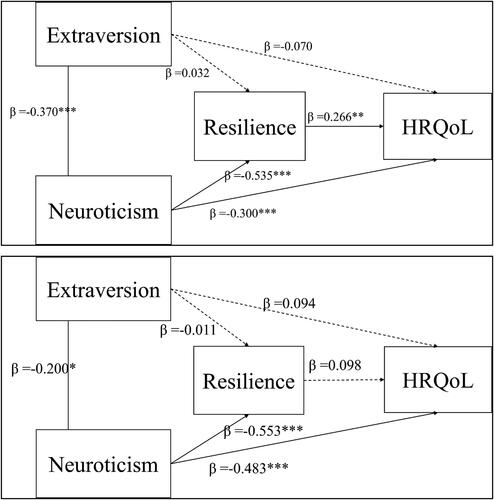

shows the pathways among two groups, respectively, according to the unconstrained path model. In the poor group, neuroticism was significantly related to resilience (β = −0.535, p < 0.001) and HRQoL (β = −0.300, p < 0.001). Resilience was significantly associated with HRQoL (β = 0.266, p < 0.01). However, extraversion had no significant relationship with neither resilience nor HRQoL. In the rich group, neuroticism was significantly related to resilience (β = − 0.553, p < 0.001) and HRQoL (β =-0.483, p < 0.001). However, in this group, resilience was not significantly associated with HRQoL. Extraversion had no significant relationship with neither resilience nor HRQoL. The mediation test showed that resilience only mediated neuroticism and HRQoL in the financially poor group (β =-0143, p < 0.01). Resilience did not mediate neuroticism and HRQoL in the financially rich group; it did not mediate extraversion and HRQoL in both two groups.

Discussion

The current study adopted a sample of 253 Hong Kong Chinese older adults to examine the relationship between two personality traits, neuroticism and extraversion, and HRQoL. Neuroticism was negatively associated with HRQoL. The relationships were partially mediated by resilience. Moreover, the mediating effect of resilience was stronger for older adults in a financially disadvantaged status than their richer counterparts.

The finding is consistent with previous studies that older adults who score high on neuroticism are more likely to have a lower HRQoL. Neuroticism and extraversion are two most pronounced personality traits that can influence individuals’ health and well-being (Butkovic et al., Citation2012). Suls and Martin (Citation2005) identified five pathways explaining why neuroticism leads to more psychological distress: (a) hyper-reactivity to minor hassles, (b) greater exposure to negative events, (c) appraisal of events as more harmful, (d) mood negative spillover, and (e) inability to adjust to recurring problems (Ong et al., Citation2009). A 40-year follow-up study conducted by Gale et al. (Citation2013) found that the two traits have a long-term influence on health and well-being in later life. For Chinese older adults specifically, Chang and Dong (Citation2014) also found that neuroticism was associated with worsened health and quality of life among Chinese older adults in the United States.

Resilience is an individual’s cognitive and affective responses to adversity. It is a critical psychosocial resource that helps older adults maintain their quality of life (Gallacher et al., Citation2012). There have been repeated evidence showing the links between personality and an individual’s resilience and well-being (Friborg et al., Citation2005). Coping is an important pathway linking personality to health. Personality influences people’s information and emotional processing, and therefore can influence people’s coping styles and behaviors during stressful life events (Ferguson, Citation2013). Emotional regulation and problem solving are especially important to older adults’ resilience than younger adults’ (Gooding et al., Citation2012). Personality is also related to people’s ability to establish social relationship and acquire social support when needed, which is also critical in determining an individual’s ability to recover from life adversities (Friborg et al., Citation2005). The present study is consistent with previous studies showing neurotic older adults tend to have a lower resilience. Some previous studies have found the mediatory effects of resilience between personality and people’ health and well-being, even though most of the outcomes were not HRQoL and the population were in a younger age (Lü et al., Citation2014). As an exception, even though they did not use the term “resilience”, Gale et al. (Citation2013) found that neuroticism influenced later life health via susceptibility to distress, which is a key feature of low resilience.

The present study also showed that neuroticism had an independent and direct association with older adults’ HRQoL, while extraversion was not significantly associated with HRQoL anymore after resilience being added to the model. It indicates that different personality traits may link with HRQoL via diverse pathways (Wiebe et al., Citation2018). It highlights the needs in future research to investigate the potential mechanisms between each personality trait separately (Smith, Citation2006).

The present study found the mediatory effects of resilience between personality and HRQoL is more salient among financially disadvantaged group. This is consistent with previous studies showing that the impacts of personality on people’s health is more apparent and amplified among disadvantaged groups (Jaconelli et al., Citation2013). It indicates that the personality-HRQoL pathways may differentiate between the poor and the rich. Specifically, personality plays a more important role in the formation of the resilience of older adults in unfavorable financial status. Resilience can be influenced by factors from multiple levels, including individual, familial, neighborhood and community, and social policy (Bennett et al., Citation2016). For financially advantaged group, the negative impacts of personality may be ameliorated by external factors, such as favorable neighborhood environment, community involvement, and quality of relationship (Jaconelli et al., Citation2013; Smillie et al., Citation2015). Wealthier people tend to live in a favorable neighborhood, and be exposed to better health care programs, and enjoy more social and community participation and support. Therefore, even though wealthy older adults score high on neuroticism, they may still be resilient as they can obtain resilience from other external sources. On the other hand, personality is more important for the resilience and HRQoL of older adults in financial difficulties. That may indicate that, when the external resource is scarce, the influence of inner capacity becomes extra salient in shaping people’s well-being. Therefore, older people with a higher level of neuroticism and a lower level of SES face double vulnerabilities in formulating resilience and a good quality of life. In addition, a higher level of extraversion may bring more benefits to poor people in negating the negative impacts of poverty (Chapman et al., Citation2010).

The present study carries several limitations. First, the findings from this study cannot be generalized to other population due to the adoption of a non-probability sample, even other Hong Kong Chinese older adults with different demographic characteristics. The respondents of this study were members of an active aging organization and therefore they tend to be relatively young and educated. Moreover, the sample consists of a much larger proportion of female participants which may also compromise the generalizability of this study. Second, the cross-sectional nature of this study indicates that the relationship found in this study cannot be interpreted as causational. Individuals’ personality may also go through changes under some life experiences, and such environmental changes may accumulate across the life span (Kandler, Citation2012). Therefore, in the present study, there is a possibility that older adults’ personality can be in reverse influenced by their quality of life. Third, the used of self-reported measure of financial status in this study, which may not fully reflect the true living conditions due to potentially different reference by the participants. Therefore, the moderating effect of financial status should be interpreted with caution. Fourth, the study consisted of a relatively small number of control variables and there is a risk of that some variables such as chronic illness and actual coping behaviors during adverse events was not included in this study.

Despite the limitations, this study has some strengths and important implications for researchers, practitioners and policymakers. This study took a pioneer effort to test the mediatory effects of resilience in the personality-HRQoL relationship, specifically among the older population. Echoing some previous studies among Chinese population, it noted that neuroticism is an important feature that can be used to identify the risky group (Chapman et al., Citation2007). An earlier study of Hong Kong Chinese older adults found that suicidal older adults tend to be more neurotic and less extraverted (Yip et al., Citation2002). Another study among Chinese aging population in the US found that a high level of neuroticism was associated with a higher likelihood of being lonely (Dong & Zhang, Citation2016). Therefore, health professionals and social work practitioners may put an extra attention to older clients with “at risk” personality, such as those who score high in neuroticism. More focus should be paid to those in financial hardship, because they may face the clustering vulnerabilities of social disadvantage and “at risk” personalities.

Author contributions

D. W. L. Lai was responsible for the conceptualization and research design, organizing data collection, providing directions for data analysis, drafting, critically review and amending the final version of the paper. J Li was responsible for data collection, data analysis, drafting, critically review, and amending the final version of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Adler, N. E., & Newman, K. (2002). Socioeconomic disparities in health: Pathways and policies. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 21(2), 60–76.

- Barlow, D. H., Ellard, K. K., Sauer-Zavala, S., Bullis, J. R., & Carl, J. R. (2014). The origins of neuroticism. Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 9(5), 481–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691614544528

- Bennett, K. M., Reyes-Rodriguez, M. F., Altamar, P., & Soulsby, L. K. (2016). Resilience amongst older Colombians living in poverty: An ecological approach. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 31(4), 385–407. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-016-9303-3

- Butkovic, A., Brkovic, I., & Bratko, D. (2012). Predicting well-being from personality in adolescents and older adults. Journal of Happiness Studies, 13(3), 455–467. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-011-9273-7

- Census and Statistics Department (2018). Hong Kong poverty situation report, 2017. Technical report, Hong Kong. https://www.povertyrelief.gov.hk/eng/pdf/Hong_Kong_Poverty_Situation_Report_2017(2018.11.19).pdf

- Chang, E. S., & Dong, X. (2014). Personality traits among community-dwelling Chinese older adults in the Greater Chicago area. AIMS Medical Science, 1(2), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.3934/Medsci.2014.2.73

- Chapman, B. P., Duberstein, P. R., So ¨Rensen, S., &., & Lyness, J. M. (2006). Personality and perceived health in older adults: The five factor model in primary care. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(6), 362–365.

- Chapman, B. P., Fiscella, K., Kawachi, I., & Duberstein, P. R. (2010). Personality, socioeconomic status, and all-cause mortality in the United States. American Journal of Epidemiology, 171(1), 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwp323

- Chapman, B. P., Roberts, B., & Duberstein, P. (2011). Personality and longevity: Knowns, unknowns, and implications for public health and personalized medicine. Journal of Aging Research, 2011, 759170. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/759170

- Chapman, B., Duberstein, P., & Lyness, J. M. (2007). Personality traits, education, and health-related quality of life among older adult primary care patients. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 62(6), P343–P352. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/62.6.p343

- Cheng, Y. H., Chi, I., Boey, K. W., Ko, L. S. F., & Chou, K. L. (2002). Self-rated economic condition and the health of elderly persons in Hong Kong. Social Science & Medicine, 55(8), 1415–1424. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00271-4

- Connor, K. M., & Davidson, J. R. (2003). Development of a new resilience scale: The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC). Depression and Anxiety, 18(2), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.10113

- Cosco, T. D., Cooper, R., Kuh, D., & Stafford, M. (2018). Socioeconomic inequalities in resilience and vulnerability among older adults: A population-based birth cohort analysis. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(5), 695–703. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217002198

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 403–425.

- Dong, X., & Zhang, M. (2016). Gender difference in the expectation and receipt of filial piety among US Chinese older adults. Journal of Social Science Studies, 2(2), 240. https://doi.org/10.5296/jsss.v2i2.7827

- Duberstein, P. R., Sörensen, S., Lyness, J. M., King, D. A., Conwell, Y., Seidlitz, L., & Caine, E. D. (2003). Personality is associated with perceived health and functional status in older primary care patients. Psychology and Aging, 18(1), 25–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.18.1.25

- Eley, D. S., Cloninger, C. R., Walters, L., Laurence, C., Synnott, R., & Wilkinson, D. (2013). The relationship between resilience and personality traits in doctors: Implications for enhancing well-being. PeerJ, 1, e216. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.216

- Etxeberria, I., Urdaneta, E., & Galdona, N. (2019). Factors associated with health-related quality of life (HRQoL): differential patterns depending on age. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 28(8), 2221–2231.

- Feng, L., Ng, X.-T., Yap, P., Li, J., Lee, T.-S., Håkansson, K., Kua, E.-H., & Ng, T.-P. (2014). Marital status and cognitive impairment among community-dwelling Chinese older adults: The role of gender and social engagement. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra, 4(3), 375–384.

- Ferguson, E. (2013). Personality is of central concern to understand health: Towards a theoretical model for health psychology. Health Psychology Review, 7(Suppl 1), S32–S70. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2010.547985

- Friborg, O., Barlaug, D., Martinussen, M., Rosenvinge, J. H., & Hjemdal, O. (2005). Resilience in relation to personality and intelligence. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 14(1), 29–42. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.15

- Gale, C. R., Booth, T., Mõttus, R., Kuh, D., & Deary, I. J. (2013). Neuroticism and Extraversion in youth predict mental wellbeing and life satisfaction 40 years later. Journal of Research in Personality, 47(6), 687–697. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2013.06.005

- Gallacher, J., Mitchell, C., Heslop, L., & Christopher, G. (2012). Resilience to health related adversity in older people. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 13(3), 197–204. https://doi.org/10.1108/14717791211264188

- Gomez, V., Allemand, M., & Grob, A. (2012). Neuroticism, extraversion, goals, and subjective well-being: Exploring the relations in young, middle-aged, and older adults. Journal of Research in Personality, 46(3), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.03.001

- Gooding, P. A., Hurst, A., Johnson, J., & Tarrier, N. (2012). Psychological resilience in young and older adults. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(3), 262–270. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2712

- Huang, I. C., Lee, J. L., Ketheeswaran, P., Jones, C. M., Revicki, D. A., & Wu, A. W. (2017). Does personality affect health-related quality of life? A systematic review. PloS One, 12(3), e0173806 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173806

- Jaconelli, A., Stephan, Y., Canada, B., & Chapman, B. P. (2013). Personality and physical functioning among older adults: The moderating role of education. Journal Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 68(4), 553–557. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbs094

- John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research. (2nd ed., pp.102–138). The Guilfotd Press.

- Kale, H. P., & Carroll, N. V. (2016). Self-reported financial burden of cancer care and its effect on physical and mental health-related quality of life among US cancer survivors. Cancer, 122(8), 283–289. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.29808

- Kandler, C. (2012). Nature and nurture in personality development: The case of neuroticism and extraversion. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21(5), 290–296. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721412452557

- Lago, S., Cantarero, D., Rivera, B., Pascual, M., Blázquez-Fernández, C., Casal, B., & Reyes, F. (2018). Socioeconomic status, health inequalities and non-communicable diseases: A systematic review. Zeitschrift Fur Gesundheitswissenschaften = Journal of Public Health, 26(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-017-0850-z

- Lai, D. W., & Qin, N. (2018). Extraversion personality, perceived health and activity participation among community-dwelling aging adults in Hong Kong. PloS One, 13(12), e0209154. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0209154

- Lai, E. T., Yu, R., & Woo, J. (2020). The associations of income, education and income inequality and subjective well-being among elderly in Hong Kong—A multilevel analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1271. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17041271

- Lamond, A. J., Depp, C. A., Allison, M., Langer, R., Reichstadt, J., Moore, D. J., Golshan, S., Ganiats, T., & Jeste, D. V. (2008). Measurement and predictors of resilience among community-dwelling older women. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(2), 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.03.007

- Lau, S. Y. Z., Guerra, R. O., de Souza Barbosa, J. F., & Phillips, S. P. (2018). Impact of resilience on health in older adults: A cross-sectional analysis from the International Mobility in Aging Study (IMIAS). BMJ Open, 8(11), e023779. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023779

- Li, J., & Zhou, X. (2021). Internet use and Chinese older adults’ subjective well-being (SWB): The role of parent–child contact and relationship. Computers in Human Behavior, 119, 106725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106725

- Li, J., Theng, Y. L., & Foo, S. (2015). Does psychological resilience mediate the impact of social support on geriatric depression? An exploratory study among Chinese older adults in Singapore. Asian Journal of Psychiatry, 14, 22–27.

- Lü, W., Wang, Z., Liu, Y., & Zhang, H. (2014). Resilience as a mediator between extraversion, neuroticism and happiness, PA and NA. Personality and Individual Differences, 63, 128–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.015

- Luthar, S. S., Cicchetti, D., & Becker, B. (2000). The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development, 71(3), 543–562.

- MacLeod, S., Musich, S., Hawkins, K., Alsgaard, K., & Wicker, E. R. (2016). The impact of resilience among older adults. Geriatric Nursing, 37(4), 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gerinurse.2016.02.014

- McHugh, J. E., & Lawlor, B. A. (2012). Social support differentially moderates the impact of neuroticism and extraversion on mental wellbeing among community-dwelling older adults. Journal of Mental Health (Abingdon, England), 21(5), 448–458.

- Ong, A. D., Bergeman, C. S., & Boker, S. M. (2009). Resilience comes of age: Defining features in later adulthood. Journal of Personality, 77(6), 1777–1804. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2009.00600.x

- Oshio, A., Taku, K., Hirano, M., & Saeed, G. (2018). Resilience and Big Five personality traits: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 127, 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.01.048

- Pampel, F. C., Krueger, P. M., & Denney, J. T. (2010). Socioeconomic disparities in health behaviors. Annual Review of Sociology, 36, 349–370.

- Ranatunga, R. V. S. P. K., Priyanath, H. M. S., & Megama, R. G. N. (2020). Methods and rules-of-thumb in the determination of minimum sample size when applying structural equation modelling: A review. Journal of Social Science Research, 15(2), 102–109.

- Shi, M., Liu, L., Wang, Z. Y., & Wang, L. (2015a). The mediating role of resilience in the relationship between big five personality and anxiety among Chinese medical students: A cross-sectional study. PloS One, 10(3), e0119916 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119916

- Shi, M., Liu, L., Yang, Y. L., & Wang, L. (2015b). The mediating role of self-esteem in the relationship between big five personality traits and depressive symptoms among Chinese undergraduate medical students. Personality and Individual Differences, 83, 55–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.050

- Smillie, L. D., Wilt, J., Kabbani, R., Garratt, C., & Revelle, W. (2015). Quality of social experience explains the relation between extraversion and positive affect. Emotion (Washington, D.C.), 15(3), 339–349.

- Smith, T. W. (2006). Personality as risk and resilience in physical health. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 15(5), 227–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2006.00441.x

- Stephens, C., Breheny, M., & Mansvelt, J. (2015). Healthy ageing from the perspective of older people: A capability approach to resilience. Psychology & Health, 30(6), 715–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2014.904862

- Su, H., Cao, J., Zhou, Y., Wang, L., & Xing, L. (2018). The mediating effect of coping style on personality and mental health among elderly Chinese empty-nester: A cross-sectional study. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 75, 197–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2018.01.004

- Suls, J., & Martin, R. (2005). The daily life of the garden-variety neurotic: reactivity, stressor exposure, mood spillover, and maladaptive coping. Journal of personality. 73(6), 1485–1509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2005.00356.x

- Thompson, W. W., Zack, M. M., Krahn, G. L., Andresen, E. M., & Barile, J. P. (2012). Health-related quality of life among older adults with and without functional limitations. American Journal of Public Health, 102(3), 496–502. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300500

- Vyas, D., & Dillahunt, T. (2017). Everyday resilience: Supporting resilient strategies among low socioeconomic status communities. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 1(CSCW), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1145/3134740

- Wang, L., Shi, Z., Zhang, Y., & Zhang, Z. (2010). Psychometric properties of the 10‐item Connor–Davidson Resilience Scale in Chinese earthquake victims. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 64(5), 499–504. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2010.02130.x

- Wiebe, D. J., Song, A., & Loyola, M. D. R. (2018). What Mechanisms Explain the Links Between Personality and Health? In Personality and Disease (pp. 223–245). Academic Press, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-805300-3.00012-8

- Wilson, R. S., Krueger, K. R., Gu, L., Bienias, J. L., de Leon, C. F. M., & Evans, D. A. (2005). Neuroticism, extraversion, and mortality in a defined population of older persons. Psychosomatic Medicine, 67(6), 841–845. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000190615.20656.83

- Wu, M., Yang, Y., Zhang, D., Zhao, X., Sun, Y., Xie, H., Jia, J., Su, Y., & Li, Y. (2018). Association between social support and health-related quality of life among Chinese rural elders in nursing homes: The mediating role of resilience. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 27(3), 783–792. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1730-2

- Yazdi-Ravandi, S., Taslimi, Z., Saberi, H., Shams, J., Osanlo, S., Nori, G., & Haghparast, A. (2013). The role of resilience and age on quality of life in patients with pain disorders. Basic and Clinical Neuroscience, 4(1), 24.

- Yiengprugsawan, V., Kelly, M., & Tawatsupa, B. (2014). SF-8TM Health Survey. In: Michalos A.C. (eds) Encyclopedia of quality of life and well-being research. Springer.

- Yip, P. S., Chi, I., Chiu, H. (2002). A multi-disciplinary study on the causes of elderly suicide in Hong Kong. Health, Welfare and Food Bureau. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.530.4488&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Yu, X-n., Lau, J. T. F., Mak, W. W. S., Zhang, J., Lui, W. W. S., & Zhang, J. (2011). Factor structure and psychometric properties of the Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale among Chinese adolescents. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52(2), 218–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.05.010

- Zafar, S. Y., McNeil, R. B., Thomas, C. M., Lathan, C. S., Ayanian, J. Z., & Provenzale, D. (2015). Population-based assessment of cancer survivors’ financial burden and quality of life: A prospective cohort study. Journal of Oncology Practice, 11(2), 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1200/JOP.2014.001542