Abstract

In health care, well-being is considered to be composed of multiple interacting dimensions and to regard the subjective (affective and cognitive) evaluation of these dimensions. These dimensions are often referred to as physical, psychological, and social domains of life. Although there are various disease-specific and group-specific conceptual approaches, starting from a universal perspective provides a more inclusive approach to well-being. Indeed, universal approaches to well-being have striking overlaps with dementia-specific approaches. Although many initiatives have been launched to promote person-centered care and attention for well-being in recent decades, the current COVID pandemic showed that the primary focus in (Dutch) long-term care was still on physical health. However, a well-being perspective can be a central base of care: it is a means to include positive aspects, and it can be applied when addressing problems such as challenging behavior in the sense that both are about needs. Furthermore, providing care from this perspective is not only about the well-being of frail people and their loved ones but also about the well-being and needs of the involved professionals. Increasingly, research shows the importance of the quality of the resident-carer relationship, the carer’s behavior, and their well-being for improving the well-being of residents. Applying the care approaches ‘attentiveness in care’ and relationship-centered care can contribute to the well-being of all involved stakeholders as these uphold the reciprocity of care relationships and take the values and attitudes, but also the vulnerability of those involved, into account.

Introduction

Quality of life (QoL) has become a central focus of institutional long-term care (de Boer et al., Citation2011; Moniz-Cook et al., Citation2008). However, genuinely contributing to the QoL of a frail person is complex. People needing long-term care have lost personal resources for maintaining QoL and often, for instance, in dementia, increasingly need help from others to maintain QoL. This requires carers to consider individual needs and preferences of frail persons that may change over time and vary between specific situations. Moreover, they need to balance efforts to support possibly diminished self-management with efforts to compensate for functional decline. This is a complex task, not in the least because the issues of what QoL means for individuals, how it can be optimally supported, and how increasing cognitive impairments affect its meaning are still open to debate (Haraldstad et al., 2019).

A universal approach to well-being

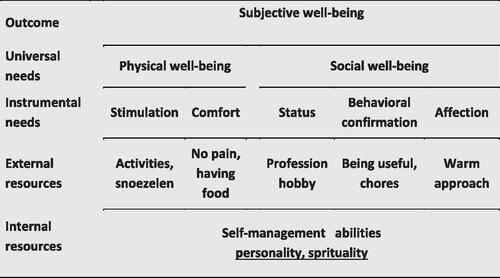

In care, well-being is commonly considered to be composed of multiple interacting dimensions and to regard the subjective (affective and cognitive) evaluation of these dimensions (Gerritsen & Steverink, Citation2017). The dimensions often represent physical, psychological, and social domains of life. Although there are various group-specific conceptual approaches to QoL or well-being (see Brod et al., Citation1999; Logsdon et al., Citation2002), the necessity and usefulness of a specific approach for people needing long term care are questionable (Gerritsen et al., Citation2004). Specific approaches focus on dimensions that may be affected by a specific condition, on dimensions that reflect specific needs of a target group, and/or needs that are associated with that condition. However, in a way, a specific approach reduces a person to their condition. It may result in excluding aspects of well-being that might not be affected by a condition, for instance, having children, but may be highly relevant for the well-being of that person and may function as a source for optimizing well-being. Furthermore, specific approaches may result in a lack of attention for unique characteristics of individuals within the group because when selecting the specific domains considered relevant, the focus is often on the domains that are relevant for the entire group, considering their condition (Gerritsen & Steverink, Citation2017). Conversely, a universal perspective provides a more inclusive approach to well-being (Gerritsen, Citation2017). Indeed, universal, inclusive approaches do not have to be that different from specific approaches. To exemplify, one of the most important approaches to the needs of and care for people with dementia is the social-psychological theory of care in dementia proposed by Kitwood and Bredin (Kitwood & Bredin, Citation1992). They formulated five central needs of people with dementia: comfort, occupation, attachment, inclusion, and identity (Kitwood, Citation1997). Although the description and content of the domains are dementia-specific, these needs have a striking overlap with the central universal needs as formulated in the companion theories of Social Production Functions (SPF; Steverink & Lindenberg, Citation2006) and Self-Management-of-Wellbeing (SMW; Steverink, Citation2014). SPF-SMW theory proposes five basic human social- and physical well-being needs. The two physical well-being needs are comfort and stimulation. Comfort is about basic physical needs such as eating, shelter, and the absence of pain. Stimulation regards a pleasant level of physical and mental activation and the absence of boredom. The three needs for social well-being are affection, behavioral confirmation and status. Affection is about the need to give and receive love and affection. Behavioral confirmation is the need to receive endorsement and to belong to a group with which one shares norms and values. Status is about the need to positively stand out for unique characteristics or accomplishments. These needs can be considered the domains of well-being. If fulfilled, an individual will experience physical and social well-being, and consequently, subjective (or psychological) well-being (see ).

SPF-SMW theory also explains how an individual’s internal and external resources can be applied when fulfilling needs and thus accomplishing well-being. This theory of behavior poses that people pursue well-being, consciously and/or subconsciously, and in doing so apply various personal resources. This makes the theory especially useful as a basis for interventions aimed at improving well-being, because it can guide the operationalization of these resources and their incorporation as working mechanisms of interventions (Gerritsen et al., Citation2004).

The internal resources that are specified in the theory are termed ‘self-management abilities’ (Steverink, Citation2014) and are jointly responsible for adequately managing resources. Examples of internal resources are self-efficacy and taking initiative. External resources include friends, money, healthcare, religion. Every person needs other people to fulfill their needs, for example, for giving the person affection or behavioral affirmation. If a person’s external resources or self-management abilities are at stake, others can contribute to that person’s well-being by compensating for lost resources, by supporting internal resources, or by providing or facilitating external resources. In long-term care, in addition to professional carers, family members may have an important role in clarifying a person’s capabilities and identity, shaping individual behavioral confirmation and status, and making explicit how others can contribute to the well-being of a particular nursing home resident.

Applying SPF-SMW theory to long-term care, it is noticeable that the physical well-being needs of ‘comfort’ and ‘stimulation’ have traditionally been the focus of nursing home care. Providing comfort has always been the core business of care. Moreover, various interventions have existed for decades that aim to improve well-being by stimulation; e.g. through exercise programs (Windle et al., Citation2010), through conversation interventions using memories (Woods et al., Citation2018), and through methods for pleasant activities (Teri & Logsdon, Citation1991). Furthermore, long-term care, at least for people with dementia, has long included the need for ‘affection’ to some extent. However, supposing well-being is universal, social well-being needs deserve more attention, especially ‘behavioral affirmation’ and ‘status’. Nursing home residents also have the need to feel useful, to contribute to their environment, and to be seen as a unique person with unique characteristics (van Corven et al., Citation2021; Vernooij-Dassen et al., Citation2011).

Covid-19

Unfortunately, although many initiatives have been launched to promote person-centered care, to involve family members in care, and to increase attention for well-being in recent years, the current COVID pandemic showed that, at least in the Netherlands, the primary focus in long term care was still on physical well-being. Starting 20 March 2020, a visitor ban came into force in all nursing homes (Verbeek et al., Citation2020). Family members were kept away to protect residents and healthcare professionals, and also themselves. Initially, most professionals considered it terrible but necessary, as was the case for many family members (Gerritsen & Oude Voshaar, Citation2020). However, within a few weeks, many residents became lonely or sad, showed more challenging behavior, and dreadful dilemmas arose (Leontjevas et al., Citation2020; Sizoo et al., Citation2020). Applying an SPF-SMW theory’s perspective, the focus was on physical well-being, predominantly on comfort in a physical sense, survival, and medical necessity. Attention for stimulation also remained. In fact, our research into challenging behavior during the COVID crisis suggests that stimulation was better tailored to the needs of, in particular, residents with dementia: there were fewer appointments and a more tranquil atmosphere, and many residents appeared to benefit (Leontjevas et al., Citation2020). However, despite the admirable efforts of professional carers, the basic social needs for affection, behavioral affirmation, and status suffered considerably by cutting off a crucial source of that social well-being: the residents’ social network. The strict ban showed that, implicitly, social well-being was not considered a basic need, and people were not able to live according to their social wishes and preferences. However, a well-being perspective can be a central base of care: it is a means to include positive aspects (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2000), and it can be applied when addressing problems such as challenging behavior (Cohen-Mansfield, Citation2000).

Challenging behavior from a well-being perspective

Challenging behavior is the behavior of a frail person that is accompanied by suffering or danger for the person themselves or for people in their environment (Zuidema et al., Citation2018). Around 80% of residents with dementia show challenging behavior (Selbaek, Engedal, & Bergh, Citation2013), but it also occurs among other groups in long-term care (e.g. van den Brink et al., Citation2020). The causes of challenging behavior may be internal or external. Internal causes may be biological (e.g. brain damage) or psychological (e.g. being anxious). External causes may regard the physical environment (e.g. too many loud noises) and the social environment (e.g. a loved one not understanding the resident’s message). Usually, a resident’s behavior is the result of interactions between internal and external causes. Trying to establish the causes of challenging behavior is often the key to its treatment, and an extensive functional analysis may guide the application of one or more of the various interventions that have been developed (Moniz Cook et al., Citation2012; Zwijsen et al., Citation2016).

Cohen-Mansfield (Cohen-Mansfield, Citation2000) provided an important basis for understanding challenging behavior with her unmet needs approach, considering three causes for such behavior: (1) behavior signals an unmet need, e.g. a resident becomes agitated in a busy environment as a result of overstimulation; (2) behavior is a way to fulfill needs, e.g. trying to resolve one’s disorientation to place by constantly asking for directions or continuously shouting to feel, ‘I’m here’; (3) behavior is an expression of frustration about an unmet need. For example, hitting a wall because a carer does not understand what the resident wants (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2017).

Given that challenging behavior is often about needs (Cohen-Mansfield, Citation2000) and needs are about well-being (Steverink, Citation2014), challenging behavior can also be linked to well-being. From a well-being perspective, a fourth possible cause of challenging behavior might be added. In the abovementioned causes of challenging behavior, the resident is involved in her well-being and tries to increase it. The fourth possible cause proposed here is that challenging behavior may be a sign that the universal pursuit of well-being is no longer active or is obstructed. For instance, the lack of purposeful behavior in apathy may indicate that a resident is no longer able to take action to fulfill their needs and is therefore not acquiring well-being (cf. Baber et al., Citation2021). If the apathy results from brain damage, this could mean that it cannot be treated, which implies that others should help with needs fulfillment (Chang et al., Citation2021). This fourth possible cause of challenging behavior may also help to explain depressive symptoms, which have been shown to be negatively associated with well-being (Smalbrugge et al., Citation2006). Depressive symptoms may not only express unmet needs, they may also be a signal that the well-being process is ‘broken’: that someone may no longer be trying to increase their well-being, may not be using their resources adequately, or that fulfillment of needs no longer leads to a positive experience. Consequently, these different possible explanations of challenging behavior require different ways of managing it.

Research into the relationship between challenging behavior and well-being has produced inconsistent results. Among people with dementia, challenging behavior has repeatedly been found to be associated with reduced well-being (e.g. van der Wolf et al., Citation2021; Winzelberg et al., Citation2005), but not always (e.g. Ballard et al., Citation2001). In addition, this relationship was mainly found using proxy measurements for well-being. Using self-report, no association was found repeatedly (Yap et al., Citation2008; Zimmerman et al., Citation2005). The relationship between challenging behavior and well-being being dependent on the cause of that behavior may possibly explain these different results. If the behavior itself fulfills needs, such as the example of continuous shouting to feel that one is alive, there may be a positive relationship between that behavior and well-being.

The described causes of behavior point towards a high involvement of the resident’s social environment (loved ones, professionals, other residents). First, the social environment may contribute to the cause or continuance of challenging behavior, for instance, because they do not understand a resident’s message resulting in frustration in that resident, or because they realize too late that the resident is over-stimulated. Second, challenging behavior poses a significant threat to achieving well-being given that the people who are needed for the provision of status, behavioral confirmation, and affection may be less inclined to give a hug or a compliment to a resident having behavior that disconcerts them. Accordingly, challenging behavior may lead to a downward spiral for the resident. Third, a resident’s challenging behavior may also imply that the well-being of their social environment is threatened. Challenging behavior can be stressful for carers (Hazelhof et al., Citation2016), which may, for instance, result in them feeling over-stimulated or sad. In turn, this may have an impact on the resident.

Shared management

When people become frail, external sources may disappear, and they may lose skills or no longer be able to use them properly. SPF-SMW theory’s substitution principle (Steverink, Citation2014) explains what happens to well-being when losses occur: If losses occur with one need, meeting the other needs may compensate to some extent. A person may still experience physical or social well-being. However, the way in which a person needs others changes when frailty surpasses a certain threshold, and the social environment must act from that new situation. In doing so, the social environment faces the question of how they can support a person, and to what extent, before they actually take over matters in pursuing well-being.

Several studies among elderly people empirically support SPF and SMW (e.g. Elzen et al., Citation2007; Steverink & Lindenberg, Citation2008). However, the question is how to apply the theory’s notion of self-management, a concept that is receiving increasing attention in long-term care (Quinn et al., Citation2016), to this population, especially residents with dementia. Apart from being a conceptual challenge, this is a relevant practical and ethical issue: given their dependence on others, the well-being of a very frail person becomes the result of several active agents, i.e. of ‘shared management’. Shaping shared management in daily practice is not self-evident and may evoke dilemmas for the people involved, for example, when efforts to self-manage by an individual with (severe) cognitive impairment are perceived as burdening for their social environment. Herein, SPF-SMW might benefit from insights into the care approaches relationship-centered care (McCormack et al., Citation2012) and attentiveness in care (Klaver & Baart, Citation2011). Applying these approaches can contribute to the well-being of all involved stakeholders as these uphold the reciprocity of care relationships and consider the values and attitudes but also the vulnerability of those involved, as will be discussed in the following section.

Relationship centered care

In the last decade, support for the importance of the quality of the relationship and the behavior of carers for resident well-being has increased (McGilton et al., Citation2012; Willemse et al., Citation2015). The attitude (Boumans, van Boekel, Baan, & Luijkx, 2019), positive behavior (van Weert et al., Citation2005), and person-centered behavior (Gilmore-Bykovskyi et al., Citation2015) of carers appear to be associated with a reduction in challenging behavior. Focusing on the capabilities of residents may improve their well-being (Norbergh et al., Citation2006), and a more hopeful attitude of carers was found to be associated with improved social well-being and less challenging behavior of residents with dementia (Gerritsen et al., Citation2019).

‘Attentiveness in care’ means attuning to the other person and their needs, skills, and preferences (Klaver & Baart, Citation2011). Indeed, these aspects are important for managing challenging behavior according to healthcare professionals (Mallon et al., Citation2019) and have been shown to be important for their job satisfaction (Edvardsson et al., Citation2011). ‘Being attentive’ requires good communication skills when interacting with the resident and their loved ones and as professionals mutually (Spector et al., Citation2013). It also means investing emotionally as professionals (McCarty & Drebing, Citation2003) and creating meaningful interaction by including the professionals’ own needs and uncertainties (Timmermann, Citation2010). This is the case, for example, if a carer tells the resident how their behavior affects them and then strives for improvement together with that resident. It is not only about ‘being there’ as representatives of a discipline but about being there as a person. This resonates with relationship-centered care and with the belief that good care originates in the reciprocal relationships of those involved, that all bring their own values and beliefs (Nolan et al., Citation2004; Westerhof et al., Citation2014). Relationship-centered care is not only about the resident, family, and one professional but about all professionals and residents involved, all with their own well-being needs (Nolan et al., Citation2004).

Although the behavior of those involved may cause or maintain challenging behavior in a resident, it can also be an important source of status, behavioral affirmation, and affection – and thus of well-being. For others to contribute to the well-being of a resident requires insight into one’s own behavior and personal leadership, daring to critically examine oneself and others, and one’s role, communication, and attitude. It also includes daring to discuss one’s thoughts and insecurities and taking each other to task (Berg et al., Citation1998; Younas et al., Citation2020). For registered nurses, doctors and psychologists, this self-awareness is an important competence that they are taught (Rasheed et al., Citation2019), but this should also be the case for all nursing staff members. Working from a relationship-centered care perspective may also help to continuously improve care. Continuously learning and innovating takes courage, and people often become insecure when asked to change their ways or when doing things for the first time (Nilsen et al., Citation2019). And in doing so, care professionals and managers alike will have to show their doubts and considerations. Leadership, be it management or personal leadership as a professional, requires courage and vulnerability.

In conclusion, an inclusive, universal approach to well-being that addresses residents, their loved ones and professionals is crucial in long-term care. Such an approach may contribute to focusing on positive aspects of life, to attentiveness in care, and also to addressing difficulties in care such as challenging behavior. In this way, the well-being of all stakeholders can be increased. The COVID pandemic has shown that long-term care requires more commitment to individual well-being and may benefit from a well-being perspective. Changing the paradigm of institutional long-term care towards a well-being perspective and shaping this according to relationship-centered care requires research into the content of well-being and into how well-being works, into how one can best support well-being in a way that suits relationship-centered care, and into how vulnerability and personal leadership can be put into practice in long-term care. Participative research designs involving the residents themselves, professionals, and institutions for education and training are necessary to do this in a way that is relevant to daily practice. By involving stakeholders in defining a problem, designing and testing potential solutions (e.g. interventions, implementation strategies) and performing effect studies, research results become more applicable and thus more likely to change and improve daily practice (Day et al., Citation2016; Nomura et al., Citation2009). If all people involved are committed to continuously improving and learning together, this will provide the means for optimal care for long-term care residents (Zorginstituut, Citation2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Baber, W., Chang, C. Y. M., Yates, J., & Dening, T. (2021). The experience of apathy in dementia: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(6), 3325. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063325

- Ballard, C., O’Brien, J., James, I., Mynt, P., Lana, M., Potkins, D., Reichelt, K., Lee, L., Swann, A., & Fossey, J. (2001). Quality of life for people with dementia living in residential and nursing home care: The impact of performance on activities of daily living, behavioral and psychological symptoms, language skills, and psychotropic drugs. International Psychogeriatrics, 13(1), 93–106. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610201007499

- Berg, A., Hallberg, I. R., & Norberg, A. (1998). Nurses’ reflections about dementia care, the patients, the care and themselves in their daily caregiving. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 35(5), 271–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7489(98)00040-6

- Brod, M., Stewart, A. L., Sands, L., & Walton, P. (1999). Conceptualization and measurement of quality of life in dementia: The dementia quality of life instrument (DQoL). The Gerontologist, 39(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/39.1.25

- Chang, C. Y. M., Baber, W., Dening, T., & Yates, J. (2021). ‘He just doesn’t want to get out of the chair and do it’: The impact of apahty in people with dementia on their carers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6317. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126317

- Cohen-Mansfield. (2000). Theoretical frameworks for behavioral problems in dementia. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly, 1(4), 8–21.

- Cohen-Mansfield, J., Golander, H., & Cohen, R. (2017). Rethinking psychosis in dementia: An analysis of antecedents and explanations. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 32(5), 265–271. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317517703478

- Day, K., Kenealy, T. W., & Sheridan, N. F. (2016). Should we embed randomized controlled trials within action research: Arguing from a case study of telemonitoring. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16, 70. 10.1186/s12874-016-0175-6

- de Boer, M. E., Droes, R. M., Jonker, C., Eefsting, J. A., & Hertogh, C. M. (2011). Advance directives for euthanasia in dementia: How do they affect resident care in Dutch nursing homes? Experiences of physicians and relatives. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 59(6), 989–996. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03414.x

- Edvardsson, D., Fetherstonhaugh, D., McAuliffe, L., Nay, R., & Chenco, C. (2011). Job satisfaction amongst aged care staff: Exploring the influence of person-centered care provision. International Psychogeriatrics, 23(8), 1205–1212. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610211000159

- Elzen, H., Slaets, J. P., Snijders, T. A., & Steverink, N. (2007). Evaluation of the chronic disease self-management program (CDSMP) among chronically ill older people in The Netherlands. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 64(9), 1832–1841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.02.008

- Gerritsen, D. L. (2017). Mensen zoals wij. Tijdschrift Voor Gerontologie en Geriatrie, 48(3), 97–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12439-017-0219-3

- Gerritsen, D. L., & Oude Voshaar, R. C. (2020). The effects of the COVID-19 virus on mental healthcare for older people in The Netherlands. Int Psychogeriatr, 32(Special Issue 11), 1352-1356. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220001040

- Gerritsen, D. L., & Steverink, N. (2017). Quality of life. In M. Vink, M. Kuin, G. Westerhof, S. Lamers & A. M. Pot (Eds.), Handbook of Geropsychology (2 ed.). de Tijdstroom.

- Gerritsen, D. L., Steverink, N., Ooms, M. E., & Ribbe, M. W. (2004). Finding a useful conceptual basis for enhancing the quality of life of nursing home residents. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 13(3), 611–624. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:QURE.0000021314.17605.40

- Gerritsen, D. L., van Beek, A. P. A., & Woods, R. T. (2019). Relationship of care staff attitudes with social well-being and challenging behavior of nursing home residents with dementia: A cross sectional study. Aging & Mental Health, 23(11), 1517–1523. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1506737

- Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A. L., Roberts, T. J., Bowers, B. J., & Brown, R. L. (2015). Caregiver person-centeredness and behavioral symptoms in nursing home residents with dementia: A timed-event sequential analysis. The Gerontologist, 55(Suppl 1), S61–S66. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu164

- Haraldstad, K., Wahl, A., Andenaes, R., Andersen, J. R., Andersen, M. H., Beisland, E., Borge, C. R., Engebretsen, E., Eisemann, M., Halvorsrud, L., Hanssen, T. A., Haugstvedt, A., Haugland, T., Johansen, V. A., Larsen, M. H., Løvereide, L., Løyland, B., Kvarme, L. G., Moons, P., … Helseth, S, on behalf of the LIVSFORSK network. (2019). A systematic review of quality of life research in medicine and health sciences. Quality of Life Research: An International Journal of Quality of Life Aspects of Treatment, Care and Rehabilitation, 28(10), 2641–2650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-019-02214-9

- Hazelhof, T. J., Schoonhoven, L., van Gaal, B. G., Koopmans, R. T., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2016). Nursing staff stress from challenging behaviour of residents with dementia: A concept analysis. International Nursing Review, 63(3), 507–516. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12293

- Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered, the person comes first. Open University Press.

- Kitwood, T., & Bredin, K. (1992). Towards a theory of dementia care: Personhood and well-being. Ageing and Society, 12, 269–287. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0144686x0000502x

- Klaver, K., & Baart, A. (2011). Attentiveness in care: Towards a theoretical framework. Nursing Ethics, 18(5), 686–693. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733011408052

- Leontjevas, R., Knippenberg, I. A. H., Smalbrugge, M., Plouvier, A. O A., Teunisse, S., Bakker, C., Koopmans, R. T. C. M., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2020). Challenging behavior of nursing home residents during COVID-19 measures in the Netherlands. Aging & Mental Health, 9, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1857695. Online ahead of print.

- Logsdon, R. G., Gibbons, L. E., McCurry, S. M., & Teri, L. (2002). Assessing quality of life in older adults with cognitive impairment. Psychosomatic Medicine, 64(3), 510–519[PMC][. 12021425

- Mallon, C., Krska, J., & Gammie, S. (2019). Views and experiences of care home staff on managing behaviours that challenge in dementia: A national survey in England. Aging & Mental Health, 23(6), 698–705. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1452898

- McCarty, E. F., & Drebing, C. (2003). Exploring professional caregivers’ perceptions. Balancing self-care with care for patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 29(9), 42–48. https://doi.org/10.3928/0098-9134-20030901-08

- McCormack, B., Roberts, T., Meyer, J., Morgan, D., & Boscart, V. (2012). Appreciating the ‘person’ in long-term care. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 7(4), 284–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-3743.2012.00342.x

- McGilton, K. S., Sidani, S., Boscart, V. M., Guruge, S., & Brown, M. (2012). The relationship between care providers’ relational behaviors and residents mood and behavior in long-term care settings. Aging & Mental Health, 16(4), 507–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2011.628980

- Moniz-Cook, E., Vernooij-Dassen, M., Woods, R., Verhey, F., Chattat, R., De Vugt, M., Mountain, G., O’Connell, M., Harrison, J., Vasse, E., Dröes, R. M., & Orrell, M, INTERDEM group. (2008). A European consensus on outcome measures for psychosocial intervention research in dementia care. Aging & Mental Health, 12(1), 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860801919850

- Moniz Cook, E. D., Swift, K., James, I., Malouf, R., De Vugt, M., & Verhey, F. (2012). Functional analysis-based interventions for challenging behaviour in dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Review, 2, CD006929. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006929.

- Nilsen, P., Schildmeijer, K., Ericsson, C., Seing, I., & Birken, S. (2019). Implementation of change in health care in Sweden: A qualitative study of professionals’ change responses. Implementation Science: IS, 14(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-019-0902-6

- Nolan, M. R., Davies, S., Brown, J., Keady, J., & Nolan, J. (2004). Beyond person-centred care: A new vision for gerontological nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13(3a), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.00926.x

- Nomura, M., Makimoto, K., Kato, M., Shiba, T., Matsuura, C., Shigenobu, K., Ishikawa, T., Matsumoto, N., & Ikeda, M. (2009). Empowering older people with early dementia and family caregivers: A participatory action research study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(4), 431–441. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.09.009

- Norbergh, K. G., Helin, Y., Dahl, A., Hellzen, O., & Asplund, K. (2006). Nurses’ attitudes towards people with dementia: The semantic differential technique. Nursing Ethics, 13(3), 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1191/0969733006ne863oa

- Quinn, C., Toms, G., Anderson, D., & Clare, L. (2016). A review of self-management interventions for people with dementia and mild cognitive impairment. Journal of Applied Gerontology: The Official Journal of the Southern Gerontological Society, 35(11), 1154–1188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0733464814566852

- Rasheed, S. P., Younas, A., & Sundus, A. (2019). Self-awareness in nursing: A scoping review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(5–6), 762–774. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14708

- Selbaek, G., Engedal, K., & Bergh, S. (2013). The prevalence and course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home patients with dementia: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 14(3), 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2012.09.027

- Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology. An introduction. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

- Sizoo, E. M., Monnier, A. A., Bloemen, M., Hertogh, C., & Smalbrugge, M. (2020). Dilemmas with restrictive visiting policies in dutch nursing homes during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative analysis of an open-ended questionnaire with elderly care physicians. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(12), 1774–1781.e1772. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.10.024

- Smalbrugge, M., Pot, A. M., Jongenelis, L., Gundy, C. M., Beekman, A. T., & Eefsting, J. A. (2006). The impact of depression and anxiety on well being, disability and use of health care services in nursing home patients. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(4), 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.1466

- Spector, A., Orrell, M., & Goyder, J. (2013). A systematic review of staff training interventions to reduce the behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. Ageing Research Reviews, 12(1), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2012.06.005

- Steverink, N. (2014). Successful development and ageing: Theory and intervention. The Oxford handbook of clinical geropsychology (pp. 84–103). Oxford University Press.

- Steverink, N., & Lindenberg, S. (2006). Which social needs are important for subjective well-being? What happens to them with aging? Psychology and Aging, 21(2), 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.21.2.281

- Steverink, N., & Lindenberg, S. (2008). Do good self-managers have less physical and social resource deficits and more well-being in later life? European Journal of Ageing, 5(3), 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-008-0089-1

- Teri, L., & Logsdon, R. G. (1991). Identifying pleasant activities for Alzheimer’s disease patients: The pleasant events schedule-AD. The Gerontologist, 31(1), 124–127. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/31.1.124

- Timmermann, M. (2010). Relationele afstemming. Presentieverrijkte verpleeghuiszorg voor mensen met dementie. Tilburg University.

- van Corven, C. T. M., Bielderman, A., Wijnen, M., Leontjevas, R., Lucassen, P., Graff, M. J. L., & Gerritsen, D. L. (2021). Defining empowerment for older people living with dementia from multiple perspectives: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 114, 103823. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103823

- van den Brink, A., Gerritsen, D. L., de Valk, M. M. H., Oude Voshaar, R., & Koopmans, R. (2020). Natural course of neuropsychiatric symptoms in nursing home patients with mental-physical multimorbidity in the first eight months after admission. Aging & Mental Health, 24(1), 155–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1531384

- van der Wolf, E., van Hooren, S. A. H., Waterink, W., & Lechner, L. (2021). Psychiatric and behavioral problems and well-being in gerontopsychiatric nursing home residents. Aging & Mental Health, 25(2), 277-285. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1695738

- van Weert, J. C., van Dulmen, A. M., Spreeuwenberg, P. M., Ribbe, M. W., & Bensing, J. M. (2005). Effects of snoezelen, integrated in 24 h dementia care, on nurse-patient communication during morning care. Patient Education and Counseling, 58(3), 312–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2004.07.013

- Verbeek, H., Gerritsen, D. L., Backhaus, R., de Boer, B. S., Koopmans, R., & Hamers, J. P. H. (2020). Allowing visitors back in the nursing home during the COVID-19 crisis: A Dutch national study into first experiences and impact on well-being. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 21(7), 900–904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.020

- Vernooij-Dassen, M., Leatherman, S., & Rikkert, M. O. (2011). Quality of care in frail older people: The fragile balance between receiving and giving. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 342, d403. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.d403

- Westerhof, G. J., van Vuuren, M., Brummans, B. H., & Custers, A. F. (2014). A Buberian approach to the co-construction of relationships between professional caregivers and residents in nursing homes. The Gerontologist, 54(3), 354–362. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt064

- Willemse, B. M., Downs, M., Arnold, L., Smit, D., de Lange, J., & Pot, A. M. (2015). Staff-resident interactions in long-term care for people with dementia: The role of meeting psychological needs in achieving residents’ well-being. Aging & Mental Health, 19(5), 444–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.944088

- Windle, G., Hughes, D., Linck, P., Russell, I., & Woods, B. (2010). Is exercise effective in promoting mental well-being in older age? A systematic review. Aging & Mental Health, 14(6), 652–669. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607861003713232

- Winzelberg, G. S., Williams, C. S., Preisser, J. S., Zimmerman, S., & Sloane, P. D. (2005). Factors associated with nursing assistant quality-of-life ratings for residents with dementia in long-term care facilities. The Gerontologist, 45(1), 106–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.106

- Woods, B., O’Philbin, L., Farrell, E. M., Spector, A. E., & Orrell, M. (2018). Reminiscence therapy for dementia. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3, CD001120. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001120.pub3

- Yap, P. L. K., Goh, J. Y. N., Henderson, L. M., Han, P. M., Ong, K. S., Kwek, S. S. L., Ong, E. Y. H., & Loh, D. P. K. (2008). How do Chinese patients with dementia rate their own quality of life? International Psychogeriatrics, 20(03), 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610207006096

- Younas, A., Rasheed, S. P., Sundus, A., & Inayat, S. (2020). Nurses’ perspectives of self-awareness in nursing practice: A descriptive qualitative study. Nursing and Health Sciences, 22(2), 398–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12671

- Zimmerman, S., Sloane, P. D., Williams, C. S., Reed, P. S., Preisser, J. S., Eckert, J. K., Boustani, M., & Dobbs, D. (2005). Dementia care and quality of life in assisted living and nursing homes. The Gerontologist, 45(1), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.133

- Zorginstituut. (2021). Kwaliteitskader Verpleeghuiszorg: Samen leren en ontwikkelen. Zorginstituut.

- Zuidema, S. U., Smalbrugge, M., Bil, W. M. E., Geelen, R., Kok, R. M., Luijendijk, H. J., van der Stelt, I., van Strien, A. M., Vink, M.T., & Vreeken, H. L. (2018). Multidisciplinary Guideline problem behaviour in dementia. Utrecht.

- Zwijsen, S. A., van der Ploeg, E., & Hertogh, C. M. (2016). Understanding the world of dementia. How do people with dementia experience the world? International Psychogeriatrics, 28(7), 1067–1077. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216000351