Abstract

Objectives

More than 60% of people with dementia live at home, where assistance is usually provided by informal caregivers. Research on the experiences of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) caregivers is limited. This scoping review of the literature synthesizes international evidence on support provision for the population of LGBT caregivers.

Methods

Eight electronic databases and Google Scholar were searched using terms including ‘Dementia’, ‘LGBT’ and ‘Caregiver’ for all types of articles, including empirical studies, grey literature and sources from charity/third sector/lobbying organisations. Article selection was performed by two raters. Data were analysed through deductive thematic analysis, and three themes were established a priori: Distinct experiences of LGBT caregivers; current barriers to support; strategies to overcome the current challenges.

Results

Twenty articles were included. Distinct experiences of LGBT caregivers included a loss of LGBT identity, the impact of historical events, families of choice, and disclosing LGBT identities. Current barriers to support included poor representation of LGBT caregivers in support services, negative attitudes of staff and reluctance of caregivers to seek support. Strategies to overcome the current challenges included staff awareness training and kite-marking inclusion.

Conclusion

Limited cultural competency of staff and a subsequent reluctance to seek help have an impact on use of support services among LGBT caregivers. Implications for practice include the development of cost-effective, feasible, and acceptable inclusiveness training for services. Implications for policy include implementation in organisations of top-down agendas supporting staff to understand sexuality and non-heteronormative relationships in older age.

Introduction

Over 50 million people worldwide are living with dementia in 2020, predicted to reach 82 million in 2030 (Alzheimer’s Disease International, Citation2020). More than 60% of people living with dementia live at home, where assistance is usually provided by informal caregivers (Alzheimer’s Society, Citation2020). Currently, 700,000 caregivers in the United Kingdom (UK) care for someone living with dementia (Dementia Caregivers Count, Citation2020), including people from the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) community. LGBT caregivers are diverse, and the size of the LGBT community is unclear (Falkingham et al., Citation2010; Benoit et al., Citation2005). Conservative estimates conclude that up to 10% of the total population identifies as LGBT (Aspinall, Citation2009; Coffman et al., Citation2017); thus, up to 70,000 LGBT people in the UK may support someone living with dementia.

The logistical, financial, physical, and emotional demands of dementia on caregivers’ wellbeing are enormous (Di Lorito et al., Citation2021), and social support and access to appropriate resources are crucial (Alzheimer’s Association, Citation2012; Alzheimer’s Society, Citation2012). Because LGBT identities serve as a separate culture, LGBT caregivers often have distinct experiences (e.g. the loss of identity as an LGBT couple, as the memory of the person living with dementia deteriorates), expectations (e.g. that service providers might discriminate against them), and needs (e.g. to know that services are LGBT-inclusive), which mediate service access and the use of support (Coon & Zeiss, Citation2003). Meeting the needs of the growing population of LGBT caregivers is not only an economic issue, because of the costs of dementia care (Alzheimer’s Society, Citation2020; Dementia Caregivers Count, Citation2020), but also a matter of social justice, as LGBT caregivers should have equal rights of access to care and services (McGovern, Citation2014).

The UK Government caregivers’ strategy in 2008 identified LGBT caregivers as a neglected group (HM Government, Citation2008), and in 2010 stated that any support ‘fit for the twenty-first Century’ must be consider caregivers’ diversity, including sexuality and gender identity (HM Government, Citation2010). These documents pledged to address the diversity of caregivers by collaborating and commission support services to third sector organisations, recognising their vital role in supporting caregivers from underserved groups, and by enabling the workforce to adopt culture-sensitive approaches to care (HM Government, Citation2008, Citation2010). Over ten years later, it remains unclear how well LGBT caregivers of people living with dementia are supported, or if they have a voice in developing services. A recent qualitative systematic review reported that dementia research reflecting the experiences of the LGBT caregivers remains urgently needed (Macdonald et al., Citation2020).

In response to this call, this paper analyses up-to-date evidence on support provision for the population of LGBT caregivers. The guiding research questions are: What are the experiences and needs of LGBT caregivers of LGBT people living with dementia? What are the current barriers to providing the type of support that address their needs? What can be done to improve service preparedness to meet their needs?

Methods and materials

This is a scoping review of the literature on support for LGBT caregivers of LGBT people living with dementia. This type of review seeks to give a high-level summary of unexplored topic areas (Grant & Booth, Citation2009). It complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist (Tricco et al., Citation2018).

Search strategy

Our search strategy (Appendix 1) was based on the PICO (Patient, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) framework (Haynes et al., Citation1997). Literature searches were conducted between March 2020 and May 2021 on eight electronic databases: PsycInfo, Medline, Embase, International Bibliography of Social Sciences, Web of Science, CINAHL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, and Ethos.

To capture grey literature and sources from charity/third sector/lobbying organisations, the first ten screens of results (n = 130) were inspected from two Google Scholar searches using terms ‘LGBT’, ‘caregiver’ and ‘dementia’ for the first search, and ‘LGBT’, ‘carer’ and ‘dementia’ for the second. Searches were limited to the last ten years, given the ever-evolving horizon of policy and services for LGBT populations. Retrieved articles were subsequently cross-referenced to identify further literature.

Article selection

Titles and abstracts of the sources retrieved from searches underwent preliminary screening. This task was carried out by the first author (CDL) alone, as it aimed to only discard the sources that were evidently out of scope (e.g. drug trials). The full texts of the remaining sources were checked for eligibility against the inclusion criteria by two authors independently (CDL and AB). Disagreement on inclusion was resolved by discussion with a third author (RH) until consensus was reached.

Inclusion criteria:

Informal (i.e. unpaid) LGBT caregiver(s) of an LGBT person living with dementia (in any type of relationship with that person, e.g. partner, family, and/or friend).

Support is received from any statutory (public sector), commercial (private sector) or voluntary organisation.

Any type of support, including health and social care, emotional and mental health and social support.

Any type of article, including empirical studies, literature reviews, commentaries, book chapters, and grey literature.

No restrictions on publication language.

Published in the last ten years (i.e. from 2011 onward).

Exclusion criteria:

LGBT caregiver(s) of a person living with dementia who is not from the LGBT community.

Because of the scope of the review and the non-empirical nature of some included articles, no formal quality assessment was conducted. All articles fulfilling the inclusion criteria were included in the review.

Data extraction and analysis

Deductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) was used, with three main themes established a priori, based on the three research questions. A data extraction form (Appendix 2) was used independently by two authors (CDL and AB) to extrapolate relevant excerpts from articles and code them into the themes. Once grouped into three themes, the excerpts were transferred onto NVivo v.12 (QSR International, Citation2018). A within-theme identification of sub-themes was then carried out independently by CDL and AB. The two authors then re-grouped to agree on the sub-themes. During the process of extraction and coding, any disagreement was resolved by inclusion of a third author (TD). The results were then reported narratively by themes and subthemes.

Patient and public involvement (PPI)

This review was fully co-produced with a member of the public from the LGBT community with previous lived experience of caring for his partner who had dementia (NC). NC was recruited through liaison of the first author with the LGBT Foundation, a third sector organisation. NC participated as an active team member in discussion about the need for this work, establishing the research aims and objectives and as a co-author in the write-up of the paper. This ensured that this work reflects and promotes representation of PPI perspectives in research (Hickey et al., Citation2018).

Results

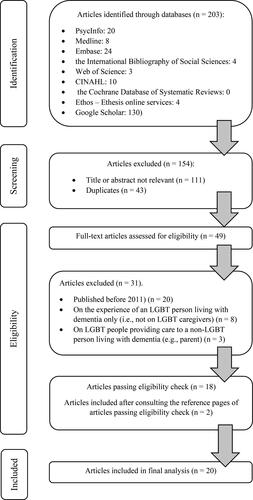

The selection process is reported in a PRISMA flow diagram () (Moher et al., Citation2009). The database search identified 203 articles. Of these, 154 records were excluded, because their title or abstract was not relevant (n = 111) or because of duplicates (n = 43). Full texts of the remaining articles (n = 49) were assessed for eligibility against the inclusion criteria, and 31 records were excluded. Two articles were further included after cross-referencing, obtaining a total of 20 articles for analysis.

Study characteristics are reported in . Thirteen studies were conducted in the UK, six in the United States of America (USA), and one in Australia. Six studies were (non-empirical) discussion papers, five were final reports from projects, three were empirical qualitative studies, three were literature reviews and three were personal essays based on lived experience.

Table 1. Study characteristics.

The three main themes were Distinct experiences of LGBT caregivers; current barriers to providing support to LGBT caregivers; what can be done to improve service preparedness to meet LGBT caregivers’ needs. Within each main theme, several sub-themes were identified ().

Table 2. Themes and sub-themes.

Distinct experiences of LGBT caregivers

The review identified four common sets of experiences that may be distinctive for LGBT caregivers: A loss of LGBT identity, the impact of LGBT historical events on help-seeking behaviour, the centrality of families of choice and social connectedness, and the challenge of disclosing an LGBT identity to support services.

A loss of an LGBT identity

Among couples, a particular concern is an erosion of their shared identity as an LGBT couple, resulting from the symptoms of the person living with dementia such as memory problems and cognitive decline. This translates into an inevitable loss of shared memories true to the caregiver’s LGBT identity (McGovern, Citation2014). The pain of this loss may even exceed the challenges of the partner’s loss of mental and physical capacity, independence, and financial stability (McGovern, Citation2014).

Impact of LGBT historical events on help-seeking behaviour

LGBT past experiences profoundly affected help-seeking behaviour. Some LGBT caregivers experienced legal discrimination and homophobia earlier in life, leading them to adopt and maintain a closeted existence and resist accessing support services (Harper, Citation2019). Other LGBT caregivers benefitted from the effects of transformational events like the Stonewall riots, Gay Rights movement, and legalisation of same-sex marriage (McGovern, Citation2014).

The AIDS pandemic generated unique barriers and facilitators. On the one hand, HIV-positive status is linked to higher risk of developing dementia, thus making LGBT caregivers more likely to be burdened with intensive and prolonged caring duties and in greater need for support (LGBT Health & Wellbeing, Citation2021). In contrast, the AIDS pandemic boosted the preparedness and resilience of the community to respond to crises, by relaxing, for example, rigid sex roles and divisions of labour in caregiving (Orel & Coon, Citation2016). An approach free of heteronormative expectations has resulted in positive emotions and feelings associated with the caregiving role, including a sense of purpose, providing spiritual and emotional nurturance, and increased connection to the LGBT community (Orel & Coon, Citation2016).

Family of choice and social connectedness

Historically, LGBT people are less likely to be able to access family support (LGBT Health & Wellbeing, Citation2021; The National Care Forum (NCF) and the Voluntary Organisations Disability Group (VODG), working with the National LGB&T Partnership, Citation2016). Consequently, many LGBT community members undertake caring roles for friends and other extended kin (Kimmel, Citation2014). In a study on LGBT older adults, almost one in three participants reported being a caregiver, suggesting that caregiving in the LGBT community is less partner centred (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2018).

This comes with certain advantages and challenges. Support systems alternative to the families of origin may facilitate resource sharing and information about effectively navigating dementia care when their potential is realised (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2018). They may also offer LGBT caregivers practical support, advocacy, advice, and freedom to express identity (Cousins et al., Citation2021), and provide a buffer against discrimination (Barrett et al., Citation2015). In the absence of support from families of origin, LGBT caregivers may become powerful and reliable advocates of the person they care for, which could strengthen the interdependency of the partnership (Barrett et al., Citation2015).

While friendships and support networks are crucial aspects of the LGBT community, however, dementia can make it harder for LGBT caregivers to maintain these connections when most needed (Adelman, Citation2016; Cousins et al., Citation2021), which may increase social isolation and loneliness (Dykewomon, Citation2018; National Dementia Action Alliance, Citation2017).

Disclosing identities

Decision to disclose an LGBT caring relationship is influenced by previous contacts with professionals (Price, Citation2012). LGBT caregivers may masquerade as heterosexuals to avoid discrimination by care staff who may hold conservative views (Barrett et al., Citation2015; Peel & McDaid, Citation2015). Some caregivers engage in active non-disclosure, including removing evidence of an LGBT identity when care staff visit (Cousins et al., Citation2021; Peel & McDaid, Citation2015) and pushing the person living with dementia to present themselves in a manner inconsistent with their LGBT identity (Adelman, Citation2016; Barrett et al., Citation2015; McGovern, Citation2014).

Sometimes, an effort not to disclose an LGBT identity might be inadvertently subverted by the cognitive changes of the person living with dementia (Newman, Citation2016). For example, dementia may reduce inhibition in expressing sexual orientation (Barrett et al., Citation2015). Decisions about caregiving and support may also force LGBT caregivers to disclose their personal lives (McGovern, Citation2014). Typically, issues around disclosure of sensitive matters may lead to considerable anxiety (Barrett et al., Citation2015), which may thwart their access to services.

Current barriers to providing support to LGBT caregivers

Several barriers frequently impact the quality of support offered to LGBT caregivers including their poor representation in services, negative attitudes of support care staff and a reluctance to seek support on the part of LGBT caregivers.

Poor representation in services

LGBT caregivers are poorly represented and not readily visible in support services (Adelman, Citation2016). Often, LGBT relationships are not identified because questions about sexuality are not asked during assessments (National Dementia Action Alliance, Citation2017). Because of the limited visibility in services, despite being the experts in the person’s wishes, LGBT caregivers may be excluded from important life-making legal decisions such as Advance Care Planning (ACP), Advanced Decision to Refuse Treatment (ADRT) and Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR) (Adelman, Citation2016; Cousins et al., Citation2021; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2018; Harper, Citation2019).

Even when the LGBT relationship is legally recognised, through marriage or civil union, some caregivers are challenged by original family members on the grounds of their same-sex relationship (Barrett et al., Citation2015).

Negative attitudes of care staff

Current service provision is characterised by heteronormativity (i.e. the assumption that heterosexuality – being sexually attracted solely to people of a different sex – is the preferred or normal mode of sexual orientation) and cis normativity (i.e. the assumption that cisgender – gender identity that match the person’s sex – is the norm). This is reflected in a lack of acknowledgement of LGBT relationships (National Dementia Action Alliance, Citation2017). Service providers report that they ‘treat everyone the same’, where sameness is ‘color blind’ to the rainbow flag.

An example of a heteronormative approach is when, in the absence of cultural awareness on the part of staff, activities using people’s memories and stories (reminiscence or storytelling) can become painfully uncomfortable for an LGBT partnership, who may feel pressured to conform and omit their most important life memories (Willis et al., Citation2011). Other manifestations of a heteronormative approach include lack of understanding and use of terminology which is appropriate with LGBT users; the application of stereotypes about LGBT partnerships; and non-awareness of the concept of the family of choice (Newman & Price, Citation2012).

If care providers operate from these normative frameworks, they may become discriminatory and prejudiced in their practice (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2018). For example, on occasions, care home staff have encouraged all residents to adhere to heteronormative standards by structuring programs of care around ‘male’ and ‘female’ roles (Cousins et al., Citation2021).

Negative attitudes may occur among General Practitioners (GPs). In a UK study, almost half of the participating GPs felt uncomfortable discussing non-heterosexual support networks with their LGBT patients (Westwood, Citation2016). Negative attitudes may be also common in care workers with more conservative/religious views (Westwood, Citation2016) and in suburban or rural areas. In a UK survey, care providers from the Scottish Highlands reported that attitudes towards LGBT people were particularly negative in their area (LGBT Health & Wellbeing, Citation2021).

LGBT caregivers’ reluctance to seek support

Staff unpreparedness to embrace diversity is mirrored by negative responses from LGBT caregivers. One in five LGBT caregivers expect to be treated worse than a heterosexual person if they need home care services (National Dementia Action Alliance, Citation2017). This may generate what Volicer (Citation2012) terms ‘rejection of care’, the tendency to resist care from providers who attempt to offer it (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2018). Barrett describes the scenario of a lesbian caregiver whose partner’s care needs had become unmanageable at home, but she resisted seeking help. Her partner had worked in services for older people and was worried about the quality of care she would receive, because of her sexual orientation, if institutionalised (Barrett et al., Citation2015).

Unfortunately, experiences of discrimination are often unreported and unaddressed (Willis et al., Citation2011). Already burdened by care duties, LGBT caregivers often feel unable to complain about non-inclusive practice (Willis et al., Citation2011).

How can services be improved to meet the needs of LGBT caregivers?

Several strategies can lessen the difficulties experienced by LGBT caregivers, including staff awareness training and kite-marking inclusion.

Staff awareness training

An important way to improve care and support services is increasing staff cultural competency and preparedness (McGovern, Citation2014). There is a need for adoption of an intelligible and malleable model of the family inclusive of polyamory, non-traditional relationships, independent financial arrangements between partners, and families of choice (Westwood, Citation2016). Staff should be able to provide tailored support that contextualises a person’s situation (Adelman, Citation2016), considering various factors, including gender, race, ethnicity, cultural background, as well as the person’s own history and the nature and extent of their dementia (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2018). Equipping staff with confidence to build their skills around inclusiveness, challenge discriminatory behaviour, and examine their own attitudes and beliefs, to combat the impact of personal biases, is also crucial (Cousins et al., Citation2021; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2018).

Several training elements have been empirically validated. Creating a safe learning space through open discussion and debate allows staff to ask questions and helps them challenge prejudice about LGBT relationships (LGBT Health & Wellbeing, Citation2021). Presentations by LGBT caregivers about the negative impacts of marginalisation from services can ‘put a face on the issues’ leading to an empathetic response from staff (Cousins et al., Citation2021; Dykewomon, Citation2018). Specialized courses can enhance awareness, but they should not be a ‘specialism’, and instead they should be embedded into all education curricula (Cousins et al., Citation2021). To promote LGBT-friendly care settings, institutions could train Diversity/Equality champions, to ensure fully inclusive support (Cousins et al., Citation2021; National Dementia Action Alliance, Citation2017). The contribution of ‘insights from the inside’ of staff who identify as LGBT can also boost staff preparedness and cultural competency (Switchboard, Citation2018).

Aside from dementia care and support services, LGBT organisations that serve older adults may benefit from training. These support organisations can reduce barriers to dementia services by offering dementia awareness training for staff, so that they can refer clients to LGBT-friendly dementia care (Adelman, Citation2016).

Concerted effort in delivering training for statutory, non-statutory and voluntary support services would increase opportunities for LGBT caregivers to access services and receive prompt support (Harper, Citation2019; McGovern, Citation2014). Therefore, friendliness (i.e. LGBT-friendly) should extend from the personal sphere of LGBT caregivers and become a principle engrained in dementia services. This would ensure, to quote Dykewomon (Citation2018), that ‘If someone gets to be 50 or 60 without any close friends, the friendliness of our institutions should be able to help’ promptly in difficult times or crises, to prevent a deteriorating situation or delay the institutionalisation of the person living with dementia (Adelman, Citation2016).

Kite-marking inclusion

Another important element to promote inclusive support services is kite-marking, which is displaying and publishing LGBT-affirming materials including images of same-sex couples on marketing materials or displaying the rainbow flag in public areas and staff badges (Cousins et al., Citation2021; Harper, Citation2019). Kite-marking (and a quality kite-marking monitoring system) can give assurances that prejudice is not tolerated and encourage LGBT people to seek help and support (Peel et al., Citation2016). Not showing such signs may send a message that their distinct needs are not considered (Newman & Price, Citation2012).

An awareness and correct use of preferred terms reflect a significant commitment to inclusion (McGovern, Citation2014). Asking ‘who are you closest to’? as opposed to ‘who is your next of kin’? may denote an inclusive approach (National Dementia Action Alliance, Citation2017). A challenge in using proper terminology is presented by the evolving use of language and by the different acceptance of language by different individuals. Therefore, it is important to use language that each individual LGBT person is comfortable with (Cousins et al., Citation2021).

Discussion

This scoping review presents up-to-date evidence on the distinct experiences of LGBT caregivers of LGBT people living with dementia, the barriers that exist in accessing appropriate services, and how provision may be improved. Because of limited cultural competency in services, LGBT caregivers currently do not receive the quality of support set out in UK legislations such as the CitationEquality Act (2010) and the Care Act (Citation2014). Heteronormative support also conflicts with the personalisation agenda in dementia care, which recognises each person’s unique needs (Carr, Citation2008). Through a personhood perspective, heteronormative provision is akin to ‘malignant psychology’ (Kitwood, Citation1997), because when attitudes and behaviours of service providers overlook a person’s needs, they perpetrate their invisibility. This low visibility has serious consequences. It prevents the development of an evidence-base around the needs of LGBT caregivers (Willis et al., Citation2011). It also makes it difficult for organisations to evidence if, and how, they provide inclusive service (Willis et al., Citation2011). Without visibility of LGBT partnerships, care providers may find it challenging to reduce stigma and improve attitudes (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2018).

This culminates in a call for action. There is a definite need for specific training for medical, nursing and care staff to raise awareness and boost professional competencies to provide care that is inclusive of LGBT communities. A classic illustration of the effects of cultural incompetency is offered by decompensation theory (Riggs & Treharne, Citation2017). An expansion of the minority stress model (Meyer, Citation2003), this theory suggests that culturally incompetent service provision generates such degrees of stress in LGBT caregivers that their protective resources (i.e. compensation strategies) may no longer work, resulting in compromised wellbeing. An example of a culturally incompetent behaviour is the use of inappropriate language. Linguistic research and social constructionist theories show that words have rhetorical but also literal effects (Burr, Citation2015). Non-inclusive language used by staff may represent an important decompensatory mechanism. In line with the theory of intersectionality and age (Calasanti & King, Citation2015), when multiple decompensatory mechanisms (including those identified in this review, such as loss of an LGBT identity and heterosexism) add up, LGBT caregivers may struggle to successfully deploy compensatory strategies, resulting in ill-health.

Levesque et al. (Citation2013) suggest that staff should display cultural competencies throughout the pathway of contact with services (i.e. from diagnosis to end-of-life care) in order to deliver health and social care for LGBT + older adults that is inclusive and person-centered. Cultural competency would enable tailoring of support, based on the distinct experiences and need of different sub-groups within the LGBT community. For example, women are more frequently affected by dementia, and it is expected that lesbians constitute a larger proportion of LGBT people living with dementia (BBC History Magazine, Citation2018). Furthermore, while male homosexuality was only legalised in the UK with the Sexual Offences Act 1967, lesbianism was never criminalised (Jones, Citation2016). Bisexual people have a unique set of needs, raising from the greater invisibility of this community (Marshall et al., Citation2015). Transgender individuals have experiences relating to their gender identity and transition that place them at greatest risk of discrimination and may generate added barriers of access to support services (Kattari et al., Citation2015). There are also important cohort trends to be considered when providing support. LGBT older adults typically have ‘social convoys’, supportive network through the life course (Antonucci et al., Citation2014; Centre for Policy on Ageing, Citation2016) and these are a unique resource that services should be aware of and effectively leverage on to support LGBT caregivers.

Cultural competency on LGBT issues should therefore be integrated into the academic curricula of all those professions (e.g. GPs) who have contact with caregivers at the different stages of the pathway (Gott et al., Citation2004). Three dimensions of competency have been identified, which promote inclusive practices towards LGBT older adults throughout the service pathway: Essential knowledge (about sexual orientation and gender identity), attitudes/soft skills (i.e. relational and human competencies) and hard skills (i.e. capacity to act inclusively) (Durand, Citation2015; Lecompte et al., Citation2020).

Training alone may be insufficient to facilitate a shift in professional attitudes and behaviours unless change occurs also at the organisational level. Individual practitioners alone have limited scope, outside of usually transient individual encounters, to make a substantial shift in culture, as they operate within set pathways and protocols. Change, therefore, needs to be supported also by a top-down agenda with clear organisational priorities (e.g. diversity and sexuality issues are addressed by policy/regulations implemented by organisations). A wide implementation in services of a sexual rights policy for older people, a good example of which is offered by the Riverdale Care Home in the USA (Dessel & Ramirez, Citation1995), would support staff to understand issues of sexuality and non-heteronormative relationships in older age (Barrett & Hinchliff, Citation2017). There is also a need for increased liaison and collaboration between statutory providers and charities/third sector organisationsorganisations. Encouraging knowledge exchange across multidisciplinary areas (dementia services and LGBT organisations) would add to the skillset and resource tools available to service providers.

It is important to acknowledge that some steps have been made towards providing better care quality for LGBT people with dementia. In the UK, the National Health Service Long Term Plan (LTP) (National Health Service (NHS), Citation2019) aims to tackle health inequalities, prevent illness, and meet unmet need for people and communities who have been left behind, including gender minorities. The Care Quality Commission (CQC), a body that inspects the quality of health and social care services, has made quality of services for older LGBT users a priority. The CQC has co-produced, with the charity Stonewall, a guide for inspectors (Care Quality Commission, Citation2017), and has cascaded several initiatives to promote good practice in the public sector, such as a toolkit for Health and Social Care Providers (LGBT Health & Wellbeing, Citation2021) offering guidance for staff, as well hints for self-reflection to identify required changes and steps to achieve them.

Efforts in the direction of more inclusive support services have also been made by LGBT and dementia third sector organisations. In the UK, the ‘Bring Dementia Out’ campaign aims to improve dementia support in the LGBT community by offering training on ‘seeing the person’, language, avoiding assumptions and understanding stigma (Cousins et al., Citation2021). Following increasing advocacy efforts for LGBT individuals affected by dementia, community programs have also been developed, offering safe and inclusive environments for LGBT families. An example of this type of initiative in the community is the Rainbow Memory Café offered by Opening Doors London (https://www.openingdoorslondon.org.uk/rainbow-memory-cafe-volunteers).

Several initiatives also exist in the USA. The Alzheimer’s Association has created marketing, websites, and specialized materials that aim to promote inclusivity using images of LGBT care partnerships (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., Citation2018). The Association has also developed specialized resource material for LGBT caregivers (https://www.alz.org/national/documents/brochure_lgbt_caregiver.pdf). In the San Francisco Bay Area, the charity Open-House offers psychological and social support to older LGBT people, as well as a three-hour LGBT cultural humility training for service providers. The course focuses on barriers to services, ageism, and use of appropriate language through practical group workshops and practical applications (https://www.openhousesf.org/training-and-transformation). While these initiatives are becoming more common in progressive countries, there is a need to systematically expand the existing strategies to ensure the reach out to communities who do not live-in metropolitan/liberal areas, and to campaign to replicate similar successful projects in other countries worldwide.

This review has certain strengths and limitations. It responds to the current call from the National Institute of Health Research for research that addresses the needs of people living with dementia in under-served groups (NIHR, Citation2021). One limitation is that the included articles did not report separately on different types on caregiver-care-receiver relationships, when caregiver-care-receiver relationships do play a prominent role in the nature and availability of care. A second limitation is that the included articles were almost all from the UK or the USA. In countries where civil partnership/marriage is not legal, or in the 71 countries that still criminalise homosexuality (Human Dignity Trust, Citation2021), the issues faced by LGBT caregivers will doubtless be dramatically greater than reported in this review.

Poor generalisability may also be due to the reluctance of LGBT people to participate in research (Callan, Citation2006; Erol et al., Citation2016; Ward et al., Citation2005). This review might only reflect the views and experiences of those who were more willing to take part in research. Also, the purely deductive approach of the data analysis might have prevented the identification of themes emerging from the data. Finally, the diverse set of identities, genders, and sexual orientations could not be differentiated, and in the articles, they were grouped together under the umbrella term LGBT (Newman & Price, Citation2012).

Because of these limitations, future research should disaggregate the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender (and beyond) communities to value the diversity of experiences, needs and practices, because gender (and gender identity) effects are too relevant not to merit some focussed attention. This requires a shift of culture in funders, which have traditionally neglected research with dispersed minority groups facing discrimination (Orel & Coon, Citation2016).

Conclusion

A lack of cultural competency may make services ill equipped to respond to the distinct needs of LGBT caregivers, who may become reluctant to seek help. Implications for practice include the development of reasonably cost-effective, feasible, and acceptable modes of inclusiveness training for dementia support services. This requires further research with LGBT caregivers to ensure that services design reflects their experiences and needs. Service design should be supplemented by the implementation in services of a sexual rights policy for older people, which would further support staff to understand issues of sexuality and non-heteronormative relationships in older age.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the LGBT Foundation and the York LGBT Forums for their support. This work was conducted in partnership with the LGBT Foundation and the York LGBT Forums.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Adelman, M. (2016). Overcoming barriers to care for LGBT elders with Alzheimer’s. Generations, 40(2), 38–40.

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2012). LGBT caregiver concerns. Alzheimer’s Association.

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2020). Numbers of people with dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International. https://www.alzint.org/about/dementia-facts-figures/dementia-statistics/

- Alzheimer’s Society. (2012). Factsheet 480. Alzheimer’s Society.

- Alzheimer’s Society. (2020). How many people have dementia and what is the cost of dementia care? Alzheimer’s Society. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-us/policy-and-influencing/dementia-scale-impact-numbers

- Antonucci, T. C., Ajrouch, K. J., & Birditt, K. S. (2014). The convoy model: Explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. The Gerontologist, 54(1), 82–92.

- Aspinall, P. J. (2009). Estimating the size and composition of the lesbian, gay and bisexual population in Britain [Research Report 37]. Equality and Human Rights Commission.

- Barrett, C., Crameri, P., Lambourne, S., Latham, J. R., & Whyte, C. (2015). Understanding the experiences and needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans Australians living with dementia, and their partners. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 34, 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12271

- Barrett, C., & Hinchliff, S. (Eds.). (2017). Addressing the sexual rights of older people: Theory, policy and practice. Routledge.

- BBC History Magazine. (2018, July 14). The 1967 sexual offences act: A landmark moment in the history of British homosexuality. BBC History Magazine.

- Benoit, C., Jansson, M., Millar, A., & Phillips, R. (2005). Community-academic research on hard-to-reach populations: Benefits and challenges. Qualitative Health Research, 15(2), 263–282. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732304267752

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Burr, V. (2015). Social constructionism. Routledge.

- Calasanti, T., & King, N. (2015). Intersectionality and age. In J. Twigg & W. Martin (Eds.), Routledge handbook of cultural gerontology (pp. 193–200). Routledge.

- Callan, M. R. (2006). Providing aged care services for the gay and lesbian community. Australian Nursing Journal, 14(4), 20.

- Care Act. (2014). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2014/23/contents

- Care Quality Commission. (2017). Meeting the needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people. Care Quality Commission. www.cqc.org.uk/news/stories/meetingneeds-lesbian-gay-bisexual-transgender-people

- Carr, S. (2008). Personalisation: A rough guide. SCIE Guide 47. Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE).

- Centre for Policy on Ageing. (2016). Diversity in older age – Older lesbian, gay and bi-sexual people and older transgender people. Centre for Policy on Ageing. http://www.cpa.org.uk/information/reviews/CPA-Rapid-Review-Diversity-in-Older-Age-LGBT.pdf

- Coffman, K. B., Coffman, L. C., & Ericson, K. M. M. (2017). The size of the LGBT population and the magnitude of antigay sentiment are substantially underestimated. Management Science, 63(10), 3168–3186. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2503

- Coon, D. W., & Zeiss, L. M. (2003). The families we choose: Intervention issues with LGBT caregivers. In D. W. Coon, D. Gallagher-Thompson, & L. W. Thompson (Eds.), Innovative interventions to reduce dementia caregiver distress: A clinical guide (pp. 267–295). Springer.

- Cousins, E., De Vries, K., & Dening, K. H. (2021). LGBTQ + people living with dementia: An under-served population. British Journal of Healthcare Assistants, 15(1), 26–35. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjha.2021.15.1.26

- Dementia Caregivers Count. (2020). Facts and figures. Dementia Caregivers Count. https://dementiacaregivers.org.uk/for-dementia-professionals/key-facts-figures/

- Dessel, R., & Ramirez, M. (1995). Policies and procedures concerning sexual expression at the Hebrew Home at Riverdale. Hebrew Home in Riverdale.

- Di Lorito, C., Bosco, A., Godfrey, M., Dunlop, M., Lock, J., Pollock, K., Harwood, R. H., Wardt, V. V. D. (2021). Mixed-methods study on caregiver strain, quality of life, and perceived health. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 80(2), 799–811.

- Durand, T. (2015). L’alchimie de la compétence. Revue Française de Gestion, 41(253), 267–295. https://doi.org/10.3166/RFG.160.261-292

- Dykewomon, E. (2018). The caregiver and her friends. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 22(1), 94–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2017.1301174

- Equality Act. (2010). https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents

- Erol, R., Brooker, D., & Peel, E. (2016). The impact of dementia on women internationally: An integrative review. Health Care for Women International, 37(12), 1320–1341.

- Falkingham, J., Evandrou, M., McGowan, T., Bell, D., & Bowes, A. (2010). Demographic issues, projections and trends: Older people with high support needs in the UK. ESRC Centre for Population Change.

- Fredriksen-Goldsen, K. I., Jen, S., Bryan, A. E., & Goldsen, J. (2018). Cognitive impairment, Alzheimer’s disease, and other dementias in the lives of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) older adults and their caregivers: Needs and competencies. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 37(5), 545–569.

- Gott, M., Hinchliff, S., & Galena, E. (2004). General practitioner attitudes to discussing sexual health issues with older people. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 58(11), 2093–2103.

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108.

- Harper, P. (2019). How healthcare professionals can support older LGBTQ + people living with dementia. Nursing Older People, 31(5), 16–21. https://doi.org/10.7748/nop.2019.e1115

- Haynes, R. B., Sackett, D. L., Richardson, W. S., Rosenberg, W., & Langley, G. R. (1997). Evidence-based medicine: How to practice & teach EBM. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 157(6), 788.

- Hickey, G., Brearley, S., & Coldham, T. (2018). Guidance on co-producing a research project. INVOLVE.

- HM Government. (2008). Caregivers at the heart of 21st century families and communities. HM Government. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_085345

- HM Government. (2010). Refreshing the national caregiver’s strategy – Call for evidence. HM Government. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Lettersandcirculars/Dearcolleagueletters/DH_117249

- Human Dignity Trust. (2021). Map of countries that criminalise LGBT people. Human Dignity Trust. https://www.humandignitytrust.org/lgbt-the-law/map-of-criminalisation/

- Jones, R. (2016). Sexual identity labels and their implications in later life: The case of bisexuality. In E. Peel & R. Harding (Eds.), Ageing & Sexualities: Interdisciplinary Perspectives (pp. 97–118). Routledge.

- Kattari, S. K., Walls, N. E., Whitfield, D. L., & Langenderfer-Magruder, L. (2015). Racial and ethnic differences in experiences of discrimination in accessing health services among transgender people in the United States. International Journal of Transgenderism, 16(2), 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2015.1064336

- Kimmel, D. (2014). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender aging concerns. Clinical Gerontologist, 37(1), 49–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2014.847310

- Kitwood, T. (1997). The concept of personhood and its relevance for a new culture of dementia care. Routledge.

- Lecompte, M., Ducharme, J., Beauchamp, J., & Couture, M. (2020). Inclusive Practices toward LGBT Older Adults in Healthcare and Social Services: A Scoping Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Evidence. Clinical Gerontologist, 44 1–12.

- Levesque, J. F., Harris, M. F., & Russell, G. (2013). Patient-centred access to health care: Conceptualising access at the interface of health systems and populations. International Journal for Equity in Health, 12(1), 18–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-9276-12-18

- LGBT Health & Wellbeing. (2021). Proud to care: LGBT dementia project. LGBT Health & Wellbeing. https://www.lgbthealth.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Dementia-Impact-Report.pdf

- Macdonald, M., Martin-Misener, R., Weeks, L., Helwig, M., Moody, E., & MacLean, H. (2020). Experiences and perceptions of spousal/partner caregivers providing care for community-dwelling adults with dementia: A qualitative systematic review. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(4), 647–703.

- Marshall, J., Cooper, M., & Rudnick, A. (2015). Gender dysphoria and dementia: A case report. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 19(1), 112–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2014.974475

- McGovern, J. (2014). The forgotten: Dementia and the aging LGBT community. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 57(8), 845–857. https://doi.org/10.1080/01634372.2014.900161

- Meyer, I. H. (2003). Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: Conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 129(5), 674–697. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G, & Prisma Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- National Dementia Action Alliance. (2017). Dementia and the LGBT + community: Roundtable notes. National Dementia Action Alliance. https://www.dementiaaction.org.uk/assets/0003/2614/LGBT__and_Dementia_-_DAA_briefing_paper.pdf

- National Health Service (NHS). (2019). The NHS long term plan. National Health Service (NHS). https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf

- Newman, R. (2016). The needs and rights of LGBT* carers of individuals with dementia. In S. Westwood & E. Price (Eds.), Lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans* individuals living with dementia: Concepts, practice and rights (pp. 190–202). Routledge.

- Newman, R., & Price, E. (2012). Meeting the needs of LGBT people affected by dementia. In R. Ward & M. Sutherland (Eds.), Lesbian, gay bisexual and transgender ageing: Biographical approaches for inclusive support and care (pp. 183–195). Jessica Kingsley.

- NIHR. (2021). NIHR highlight notice – Dementia. NIHR. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/nihr-highlight-notice-dementia/27316

- Orel, N. A., & Coon, D. W. (2016). The challenges of change: How can we meet the care needs of the ever-evolving LGBT family? Generations, 40(2), 41–45.

- Peel, E., Taylor, H., & Harding, R. (2016). Sociolegal and practice implications of caring for LGBT people with dementia. Nursing Older People, 28(10), 26–30.

- Peel, E., & McDaid, S. (2015). ‘Over the rainbow’: Lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans people and dementia project. Summary report. University of Worcester. http://dementiavoices.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Over-the-Rainbow-LGBTDementia-Report.pdf

- Price, E. (2012). Gay and lesbian carers: Ageing in the shadow of dementia. Ageing and Society, 32(3), 516–532. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X11000560

- QSR International. (2018). NVivo (Version 12). QSR International Pty Ltd.

- Riggs, D. W., & Treharne, G. J. (2017). Decompensation: A novel approach to accounting for stress arising from the effects of ideology and social norms. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(5), 592–605.

- Switchboard. (2018). LGBTQ + communities and dementia. Engagement report. Switchboard. https://www.switchboard.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/LGBTQ-Dementia-Report_Final.pdf

- The National Care Forum (NCF) and the Voluntary Organisations Disability Group (VODG), working with the National LGB&T Partnership. (2016). Dementia care and LGBT communities: A good practice paper. The National Care Forum (NCF) and the Voluntary Organisations Disability Group (VODG), working with the National LGB&T Partnership. https://nationallgbtpartnershipdotorg.files.wordpress.com/2016/04/dementia-and-lgbt-communities-good-practice-april-2016.pdf

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473.

- Volicer, L. (2012). Treatment of behavioural disorders. Pathy’s Principles and Practice of Geriatric Medicine, 1, 961–975.

- Ward, R., Vass, A. A., Aggarwal, N., Garfield, C., & Cybyk, B. (2005). A kiss is still a kiss? The construction of sexuality in dementia care. Dementia, 4(1), 49–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301205049190

- Westwood, S. (2016). Dementia, women and sexuality: How the intersection of ageing, gender and sexuality magnify dementia concerns among lesbian and bisexual women. Dementia, 15(6), 1494–1514. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214564446

- Willis, P., Ward, N., & Fish, J. (2011). Searching for LGBT carers: Mapping a research agenda in social work and social care. British Journal of Social Work, 41(7), 1304–1320. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcr114

Appendix

Search strategy

Exp lgbt/or (Gay or lesbian or LGBT* or homosexual or bisexual or transsex* or transgender* or trans or queer).ti,ab.

AND

exp Dementia/or exp Alzheimer’s disease/or (dement* or Alzheimer*).ti,ab.

AND

Exp caregiver or (Caregiver* or caregiver*).ti,ab.