Abstract

Objectives

Informal caregivers of dependants with dementia commence their bereavement experience long before the physical death of their dependant, a process referred to as “anticipatory grief”. This represents an ambiguous state that has been acknowledged as a measurable variable among informal caregivers. The use of assessment tools for the identification of anticipatory grief is important for timely intervention to promote well-being and positive bereavement experiences. The aim of this systematic review is to identify and examine existing tools for assessing anticipatory grief among caregivers of dependants with dementia

Methods

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychINFO, CINAHL and Web of Science were searched to July 2021. Studies focusing on the development/evaluation of instruments for measuring anticipatory grief in dementia caregivers were eligible. The quality of each measurement was graded as positive, fair, poor or no information based on defined criteria.

Results

100 studies were identified. 33 papers were selected for full-text assessment and 12 papers met the eligibility criteria. Seven assessment tools were identified for measurement of pre-death grief caregivers – the Anticipatory Grief Scale (AGS), Marwit-Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory (MM-CGI), MM-CGI-short-form (MM-CGI-SF), MM-CGI-brief (MM-CGI-BF), Prolonged Grief Scale (PG-12), Caregiver Grief Scale (CGS) and Caregiver Grief Questionnaire (CGQ). Based on content/construct validity, internal consistency and test-retest reliability the MM-CGI/MM-CGI-SF scored highest for quality followed by the CGS.

Conclusion

Anticipatory grief in dementia has multiple facets that can be measured using self-scoring questionnaires. Our findings provide support for different measures of anticipatory grief. Further research is needed for the evaluation of the responsiveness and interpretability of these instruments.

Background

As the world’s population ages and people live longer changes concerning the ageing brain, which include dementia, present substantial challenges to our society. The global prevalence of dementia has been estimated to be as high as 24 million and is predicted to double every 20 years until at least 2040 (Mayeux & Stern, Citation2012; Sleeman et al., Citation2019). Informal caregivers of dependants with dementia commence their experience of grief long before the physical death of the patient (Cheung et al., Citation2018). This process is referred to as “anticipatory grief” that often remains unrecognised to both caregivers and healthcare professionals (Coelho et al., Citation2018; Dempsey & Baago, Citation1998). The anticipatory grief specifically experienced by these informal caregivers refers to feelings of pre-death grief in response to compound serial losses in the dementia process (Cheung et al., Citation2018). These losses include loss of intimacy and companionship, personal freedom, social or occupational opportunities and role identity (Large & Slinger, Citation2015).

The long trajectory of dementia and its progressive nature associated with accumulated decline inevitably has negative consequences for informal caregivers. They may be overwhelmed, react emotionally and feel guilty (Chan et al., Citation2013). This may result in an additional burden to the caregivers beyond what is experienced among caregivers of other types of illnesses. In addition, attachment bonds are eroded slowly, incompletely and ambiguously (Dempsey & Baago, Citation1998). In an open-ended survey among 353 dementia caregivers, Frank observed that anticipatory grief and ambiguous loss, rather than their hands-on care, represented the major concerns experienced by caregivers of dependants with Alzheimer’s (Frank, Citation2008). Pre-death grief in dementia caregivers is a complex phenomenon since informal caregivers often experience many ongoing losses which invite a state of separation from the person with dementia and from an anticipated future (Blandin & Pepin, Citation2017; Chan et al., Citation2013). This makes a pre-death loss in dementia a distinctive type of grief, whereby the dependant or loved one is still physically ‘present’ but emotionally disconnected from the caregiver.

According to the recent studies, the prevalence of anticipatory grief among informal caregivers of dependants with dementia ranges between 47% and 80% (Chan et al., Citation2013; Liew, Yeap, et al., Citation2018b). It appears that pre-death grief reaction among informal caregivers of dependants with dementia is associated with caregiver burden (Chan et al., Citation2013; Holley & Mast, Citation2009; Liew et al., Citation2020) that is independent of other predictors of burden for example depressive symptoms, gender, age and behavioural problems (Holley & Mast, Citation2009; Liew et al., Citation2019a, Citation2019b). Caregiver burden is linked with undesirable outcomes for example premature care home placement and patients’ earlier mortality (Lwi et al., Citation2017; Toot et al., Citation2017). Although the link between carers’ anticipatory grief and undesirable outcomes (e.g. premature care home placement) has yet to be investigated, understanding anticipatory grief is potentially a key area for intervention to prevent caregivers from experiencing burden and depression (Ying et al., Citation2018). Therefore, it is vital to understand and detect pre-death grief in informal caregivers of dependants with dementia so that it can be effectively addressed promptly. On the same note, longitudinal studies in dementia caregivers have indicated that high levels of pre-death grief amplify the effect of caregivers’ burden on caregivers’ depression (Liew et al., Citation2019b). Therefore, it is important to identify potential candidates or cases of anticipatory grief among caregivers of dependants or loved ones with dementia using reliable and valid assessment tools to identify those most at risk. The consequences of not doing mean it is easy to miss pre-death grief since their grief is typically disenfranchised. Early detection of anticipatory grief may present a vital window of opportunity to improve caregivers’ quality of life (Liew et al., Citation2019b). Moreover, there is also evidence that grief-related interventions are only offered to those who are experiencing high levels of grief. Therefore there is a necessity to routinely measure anticipatory grief using an objective scale (Liew & Lee, Citation2019). To adequately and effectively screen for anticipatory grief, health professionals must be equipped with evidence of their validity, reliability and relative attributes. This review therefore aims to identify, describe and appraise existing tools for assessing anticipatory grief in informal caregivers of dependants with dementia. More specifically, the objectives of this review are

To identify and describe the tools used for assessing anticipatory grief in informal caregivers of dependants with dementia

To examine the structure and delivery of these assessment tools.

To examine the measurement properties (validity, reliability, responsiveness, acceptability and interpretability) of assessment tools.

To appraise the different methods of assessment of anticipatory grief.

To make recommendations for clinical care and future research.

Methods

This systematic review is reported in line with the PRISMA guideline (Moher et al., 2009) based on published literature examining the tools for assessment of anticipatory grief in dementia caregivers until July 2021.

Eligibility criteria

Participants: Studies included informal caregivers of dependants with dementia. For this review, a caregiver is defined as someone who regularly looks after a person with dementia e.g. spouse, sibling or adult children (Carduff et al., Citation2014). To augment the list, family proxies of patients with dementia were also included. No age or gender limit was considered as eligibility criteria in this review.

Assessment Tools: All assessment tools that have been tested for their validity and reliability to measure anticipatory or pre-death grief in dementia caregivers.

Study Design: Studies focusing on the development/evaluation of instruments (e.g. questionnaires) measuring anticipatory grief.

Report characteristics: All studies published or in-press available in the databases were included in this review. Studies that were not written in English were used if enough information could be obtained from the abstract or translation. Reviews and grey literature (e.g. dissertations) were excluded.

Information sources and study selection

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsychINFO, CINAHL and Web of Science from database inception to July 2021. Forwards and backwards citation tracking, as well as manual searching, were used to identify relevant papers. presents the free-text and subject heading terms that were combined in the search strategy. The structure of [dementia] AND [grief] AND [measurement] were used according to the following table. The table only presents MEDLINE’s subject headings. For other databases, the subject headings were adjusted to optimise the overall search strategy. The search was not limited to title or abstract. In addition, we conducted a hand search of three relevant key journals (Palliative Medicine, Journal of palliative Care and BMJ Supportive and Palliative Care) in the past five years to ensure no relevant paper is missed.

Table 1. Search terms used to identify papers related to dementia and anticipatory grief (MEDLINE).

Study selection

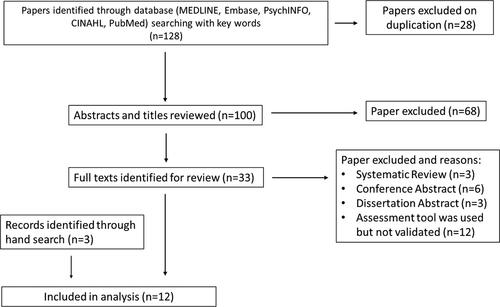

Titles and abstracts were screened using the above eligibility criteria. Review articles and studies where informal caregivers of individuals with dementia could not be separated from other patients (e.g. cancer) were excluded. After this initial screening, the full text of the papers was reviewed by two researchers [TD and Alireza Mani (AM)], and any discrepancies were discussed with JK to reach a consensus. All reasons for exclusion were noted and appear in the PRISMA study flowchart (). To aid data extraction and synthesis a form was generated and completed for each paper to address the specific objectives of this review.

Grading the quality of the studies

Evaluation of each study on validation of measurement tools was based on criteria developed by Terwee et al. (Citation2007) and Ellis-Smith et al. (2016). These criteria provide four ratings: ‘positive or high quality’ (strong measurement tool using adequate design and method), ‘intermediate or fair’ (some but not all aspects of the tool are positive, or there is doubt about design and method used), ‘negative or poor’ (assessment tool does not meet criteria despite adequate design and method), or ‘no information’. The following characteristics of the assessment tools were assessed in each study: content validity, construct validity, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, inter-rater reliability, acceptability, floor/ceiling effects, interpretability as described (Terwee et al., Citation2007). The quality of the papers was scrutinised by two researchers (TD and AM) and any discrepancies were discussed with JK to reach consensus.

Results

A total of 128 papers were identified of which 28 were duplicates and 68 were excluded since the title and abstract did not meet the inclusion criteria. Of the 32 eligible full-texts, 12 were excluded due to being either systematic reviews or dissertations. The full texts of the remaining papers were thoroughly examined to identify those papers where validation of assessment tools was reported. Twelve papers were subsequently excluded, as the assessment tools were not validated in their investigation. Three studies were included by hand-search (by journal content pages or cross-referencing) or recommendation from subject experts. Overall, 12 papers were identified where the assessment tools were validated for the evaluation of anticipatory grief in dementia caregivers. summarises the process of study selection.

Characteristics of selected studies

presents the characteristics of selected studies that were published between 1991 and 2021 in terms of study location, sample size, assessment tools for anticipatory grief, other outcome measures and quality appraisal of each study. The common themes of these studies are that assessment tools were validated for the evaluation of ‘pre-death grief’ among caregivers of people with dementia. Overall, seven assessment tools for measuring pre-death grief were identified in these studies. The earliest tool (1991) that was specifically developed for the assessment of pre-death grief in informal caregivers of dependants with dementia was the Anticipatory Grief Scale (AGS) (Theut et al., Citation1991) and the latest ones are the Caregiver Grief Scale (CGS) (Meichsner et al., 2016 ) and Caregiver Grief Questionnaire (CGQ) (Cheng et al., Citation2019). The most common tool used in research studies was the Marwit Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory (MM-CGI) (Marwit & Meuser, Citation2002). This instrument has also been used in its short form and is known as MM-CGI-SF (Marwit & Meuser, Citation2005). Recently, a brief form of MM-CGI has been developed and validated in 2020 (Liew & Yap, Citation2020). The original version of the Prolonged Grief Disorder Inventory (PG-12) was used in three studies for the assessment of pre-death grief in informal caregivers of dependants with dementia (Prigerson et al., 2009). This tool was not specifically designed for anticipatory grief informal caregivers of dependants with dementia (Prigerson et al., Citation1995). Others were specifically validated for the assessment of anticipatory grief in dementia caregivers.

Table 2. Characteristics of selected studies.

Six out of seven of the assessment tools were originally developed in English. The only exception is CGS that was developed and validated in Germany.

Structure and delivery of the assessment tools

Anticipatory Grief Scale (AGS): This tool was developed in 1991 by Theut et al., based on clinical experience and other instruments measuring grief, for example, the Texas Revised Inventory of Grief (TRIG) (Theut et al., Citation1991). This scale represents the first assessment for measuring pre-death grief in dementia caregivers. The scale has been extended (by modifying the words) to other contexts, for example, cancer and palliative care (Holm et al., Citation2019). The AGS scale comprises 27 items measuring anticipatory grief on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Eight out of 27 items are positive bearing questions and the remaining items are negative bearing questions. For all of the positive bearing questions (question 2, 5, 8, 11, 19, 22, 26, 27), the scoring is reversed (i.e. 1 → 5, 2 → 4, 3 → 3, 4 → 2, 5 → 1). For negative bearing items, scores remain the same. A summary score of the items ranges from 27-135, where a higher score is indicative of a higher level of anticipatory grief.

Marwit-Meuser Care Inventory (MM-CGI): In 2002, Marwit and Meuser developed a tool to measure pre-death grief among family caregivers of dependants with dementia and that was psychometrically sound (Marwit & Meuser, Citation2002) and was based on empirical data from 88 family caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease. Following factor analysis, 50 questions were selected and were converted to items with a 1–5 Likert scale. The correlation of these questions was also tested with other existing instruments for example the AGS, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS), the Caregiver Strain Index (CSI-15), the Caregiver Well-Being Scale (WBS-BN) and the Perceived Social Support-Family Questionnaire (PSSQ-Fa) (Marwit & Meuser, Citation2002). As a result, the 50 items were categorised into three domains (subscales):

Factor 1: Personal Sacrifice Burden

Factor 2: Heartfelt Sadness and Longing

Factor 3: Worry and Felt Isolation

The MM-CGI is a self-scoring questionnaire. To calculate the subscale score and total grief score the circled numbers should be added with exception of ‘C’ items with ‘r’ afterwards which must be firstly reversed (1 → 5, 2 → 4, 3 → 3, 4 → 2, 5 → 1) before calculating the scores. As a result, the MM-CGI provides a total grief level (sum A + B + C) in addition to subscale grief scores (sum of A only, sum of B only and sum of C only). These subscales are referred to as ‘factor 1′, ‘factor 2′ and ‘factor 3′ respectively. The questionnaire also gives a personal profile for each factor based on distributions of symptoms in informal caregivers of dependants with dementia. Marwit and Meuser proposed using one standard deviation above the normative mean of a population to indicate that they referred to as ‘high pre-death grief’ (Marwit & Meuser, Citation2002). Consequently, a high total score (above 175) indicates a need for formal intervention to support those who experience grief. The score of each subscale can also be used as an indicator for an intervention. For example, a score above 68 in Factor 1 (‘personal sacrifice burden’), 59 for Factor 2 (‘heartfelt sadness and longing’) and 52 for Factor 3 (‘worry and felt isolation’) can be used to indicate a caregiver in a potentially high-risk category. Low scores (scores below one standard deviation of the mean population) may indicate adaptive coping or even the presence of denial of grief reaction.

The authors’ initial validation of the MM-CGI identified that the total score subscale scores (factors1, 2 or 3) exhibit a statistically significant correlation with other existing assessment tools for example AGS, BDI and GDS. Furthermore, Cronbach’s α for the total score and the subscales range from 0.90 to 0.96 which indicates high internal consistency reliability (Marwit & Meuser, Citation2002).

The MM-CGI instrument has been used extensively and further validated by other groups (Gilsenan et al., Citation2022; Liew, Citation2016; Liew, Yeap, et al., Citation2018b). It has also been used for validation of other assessment tools of anticipatory grief such as MM-CGI-SF, PG-12 and CGS (Liew, Citation2016; Marwit & Meuser, Citation2005; Meichsner et al., Citation2016b). The Mandarin version of this inventory was validated in 394 family caregivers that indicated high internal consistency and validity as shown in . It is worth mentioning that there are some variations in the interpretation of MM-CGI subscales in different populations and the subscales of MM-CGI, therefore, need to be interpreted with caution across different cultures (Liew et al., Citation2018b ).

Table 3. Validity, reliability (test, re-test), internal consistency (Cronbach’s α) of different measurement scales of anticipatory grief in dementia caregivers. ICC: Interclass Correlation Coefficient.

Marwit-Meuser Care Inventory Short-Form (MM-CGI-SF): Soon after the development of the MM-CGI, Marwit and Meuser worked on a short-version of this assessment tool to make it clinically more applicable (Marwit & Meuser, Citation2005). MM-CGI-SF questionnaire is made of 18 items with a 1-5 Likert scale. Calculation of subscale and total scores are simpler in comparison with MM-CGI as the score of none of the items needs to be reversed. Each subscale consists of 6 questions. Similar to the original questionnaire, Marwit and Me er suggested that individuals whose scores were higher than one standard deviation from the mean might require intervention and support assistance to enhance their coping. As stated, the MM-CGI has 50 items in three subscales. In the short form, only 18 items are included based on an inter-correlation procedure. These items are those that best identify each subscale (factor). This modified questionnaire was subsequently validated in 292 participants (family caregivers of dependants with dementia) based on correlation with original MM-CGI, BDI, AGS, GDS-15, CSI, WBS-BN and PSSQ-Fa (Marwit & Meuser, Citation2005). The results showed that all three factors of MM-CGI-SF were significantly related to MM-CGI subscales. As expected, the same factors had the highest correlation coefficient (r ranged from 0.915 to 0.928). Furthermore, the MM-CGI-SF showed a significant statistical correlation with other existing scales including the AGS, BDI, GDS-15, CSI, WBS-BN and PSSQ-Fa. In terms of internal consistency, the items for each of the three factors displayed good reliability in the MM-CGI-SF (Cronbach’s α was between 0.80 and 0.85 for all three factors)( Gilsenan et al., Citation2022; Marwit & Meuser, Citation2005). The MM-CGI-SF is a self-scoring questionnaire and has been used in many studies since 2005 and has been validated by others in recent years (Liew, Yeap, et al., Citation2018b; Gilsenan et al., Citation2022). In a recent study, exploratory factor analysis was carried out in a large UK sample of dementia caregivers (n = 508) and the results showed that the MM-CGI-SF is better than the full version of the MM-CGI in terms of model fit. Overall, the MM-CGI-SF three-factor model demonstrates acceptable internal consistency and factor correlations with associated psychometric measures (Gilsenan et al., Citation2022).

Marwit-Meuser Care Inventory Brief (MM-CGI-BF): Recently, a new 6-item derivative of the MM-CGI has been developed by Liew and Yap (Citation2020) to make it more suitable for clinical use and reduce the overlap between the grief scale and burden/depression (Liew & Yap, Citation2020). Six items of the original MM-CGI were included in this new self-scoring questionnaire (i.e. items 2, 15, 27, 30, 36 and 43). Validating this brief pre-death grief scale on family caregivers of individuals with dementia (n = 394) identified that MM-CGI-BF can explain 84% of the variability in MM-CGI with acceptable construct validity, reliability and internal consistency. Apart from being brief, the most important advantage of this scale is that it has less overlap with caregivers’ burden and depression. Overall, MM-CGI-BF may potentially overcome the length issue of the original scale, while still allowing score mapping back to the MM-CGI and MM-CGI-SF.

Caregiver Grief Questionnaire (CGQ): Another brief version of MM-CGI has recently been developed by Cheng et al., in 2019. The main motivation behind the construction of this tool was to include only the core aspects of pre-death grief, namely relational deprivation and emotional pain (Cheng et al., Citation2019). From factor 2 of the MM-CGI scale (Heartfelt Sadness and Longing), seven items were selected. Then, three items from an established measure of relational deprivation (Pearlin et al., Citation1990) were added to construct an 11-item questionnaire. The reliability and validity of this brief questionnaire was assessed in 173 caregivers in Hong Kong. CGQ is a brief, yet multi-dimensional tool with two factors measuring relational deprivation and emotional pain. These factors focus on two core dimensions of pre-death grief while avoiding confounding with caregiver burden.

Prolonged Grief Disorder Inventory (PG-12 or PG-13): PG-12 is a psychometric method used for the assessment of Prolonged Grief Disorder among relatives of dependants with different underlying diseases. It was originally developed and validated by Prigerson et al., in 2009 based on interviews with 291 bereaved individuals (Prigerson et al., 2009). In their interviews, the researchers utilised “item response theory” to derive the most informative symptoms from structured interviews of caregivers who had recently experienced the death of a close family member. Their findings validated a set of unbiased symptoms for prolonged grief disorder that can be incorporated into DSM-V and ICD-11 (Prigerson et al., 2009). Although this method of assessment was originally intended for post-death grief it has recently been used in the detection of pre-death grief among caregivers of dependants with cancer (Coelho et al., Citation2017) as well as those with dementia (Kiely et al., Citation2008; Liew, Citation2016; Mulligan, Citation2010).

This assessment was initially developed with 12 questions that were subsequently modified to include an extra question (the modified version is known as PG-13). PG-13 has 11 items with a 5-point Likert scale and two “binary” (yes/no) questions.

Caregiver Grief Scale (CGS): In 2016, Meichsner et al. (Citation2016b) developed a new scale for the assessment of grief among dementia caregivers that was more specifically targeted to caregiver grief rather than grief-related factors. The authors argued that although MM-CGI represents a comprehensive measure of pre-death grief, only factor two (‘heartfelt sadness and longing)’ is related to what they believed to be true grief. To develop CGS, an initial pool of 21 questions was created through the selection of items from existing instruments as well as new items. These new items were generated based on statements suggested by informal caregivers (Meichsner & Wilz, Citation2018). Out of 21, eight items were adopted from MM-CGI (all from factor 2) with minor modification. Seven new items were developed. In addition questions from Inventory of Complicated Grief (ICG-R) and TRIG as well as Wurzburg Grief Inventory (WuGI) were adopted (Meichsner et al., Citation2016b). The factor analysis of this new instrument was conducted with 292 caregivers in Germany. The CGS comprises four following factors: (1) emotional pain, (2) relational loss, (3) absolute loss, and (4) acceptance of loss. The Total CGS score and scores for factors 1 and 4 were associated with a significant correlation with other psychometric tests including CES-D, HADS, WHOQoL-BREF and GBB-24. These correlations were not significant with factors 2 and 3. The total scale and subscales (factors) exhibited high internal consistency (assessed by Cronbach’s α). Overall, this method has high construct validity and reliability. In terms of responsiveness, a recent study by Meichsner and Wilz identified that the CGS could detect improved coping after CBT-based intervention (Meichsner & Wilz, Citation2018).

Validity and reliability of assessment tools

presents studies that have measured the validity and reliability of the assessment tools. Column 3 represents the construct validity of the questionnaires that were tested against other existing instruments. Evaluation of reliability was based on (a) test-retest reliability and (b) internal consistency which is represented as Cronbach’s α. summarises the quality assessment of each instrument in terms of content validity, construct validity, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, inter-rater reliability, responsiveness, floor/ceiling effect and interpretability each of that is appraised below.

Table 4. Summary of the assessment of the measurement properties of all questionnaires measuring anticipatory grief in dementia caregivers.

Content validity: A clear description of the measurement aim, target population and item selections were found in MM-CGI (in both original and short/brief forms), AGS, CGQ and CGS. The PG-12 questionnaire was originally validated in bereaved caregivers of people with cancer (Prigerson et al., 2009). Although this questionnaire was later used for the assessment of pre-death grief in informal caregivers of dependants with dementia (Kiely et al., Citation2008; Mulligan, Citation2010), the content has not been validated within this context. Therefore, the score for quality of content validity is poor. The quality of studies on construct validity is indicated in the second column of .

Construct Validity: During the development of all assessment tools, correlation with other relevant psychometric tests were considered and showed a significant result (hypothesis testing). Correlation Coefficients were reported for all assessment tools except the AGS. All assessment tools except the AGS exhibited positive scores in the quality of construct validity (column three in ).

Internal Consistency: The Cronbach’s α was calculated for all the screening tools as shown in . Most assessment tools exhibited acceptable internal consistency with Cronbach’s α greater than 0.81. CGS was the only assessment tool with lower reported Cronbach’s α (between 0.67 and 0.89) ().

Factor Analysis: Factor analysis was only performed for the MM-CGI, MM-CGI-SF, MM-CGI-BF, CGQ and CGS. No information is available on the factor analysis of AGS and PG-12 for dementia caregivers. MM-CGI-SF was developed based on the selection of items in the MM-CGI. Marwit and Meuser observed a significant correlation between the short-form and original questionnaires in each subscale (factors)(Marwit & Meuser, Citation2005). In addition, there are independent data on factor analysis of MM-CGI-SF per se which indicated adequate fit and utility for all three factors (Gilsenan et al., Citation2022).

Test-retest reliability: The Interclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) was calculated for five of the seven assessment tools, namely MM-CGI (original, short-form and brief form), CGQ and CGS ().

Inter-rater reliability: Since all questionnaires are self-scoring instruments, inter-rater reliability does not apply to these assessment tools (column six in ).

Responsiveness: No evidence was identified concerning the assessment of responsiveness for previously mentioned assessment tools in the literature. No studies presented in refer to data on responsiveness. However, two additional reports have identified changes in MM-CGI and CGS scores after behavioural interventions (Meichsner & Wilz, Citation2018; Paun et al., Citation2015). These reports provide evidence that the MM-CGI and CGS are responsive to clinically relevant interventions. However, no studies have been reported to measure the responsiveness of these assessment tools. Therefore, the method for the assessment of responsiveness remains in doubt.

Acceptability: The following categories summarise the barriers to the use of the questionnaires in clinical practice:

Measures that are too long for participants to answer: MM-CGI is the longest questionnaire among the 50 items. The authors developed a short-form in response to feedback from clinicians (Marwit & Meuser, Citation2002). A brief form with six items has also been developed by Liew and Yap (Citation2020).

Measures that require a long time for administration: As all assessment tools are self-scoring, they are appropriate for clinical practice in terms of administration.

Measures with a complicated scoring system: Calculation of scores for AGS and MM-CGI require reversing the scores in several items. This can be confusing and time consuming for the participants or the assessors. MM-CGI-SF, MM-CGI-BF, PG-12, CGQ and CGS have a simple and acceptable scoring system.

Additional cost: No evidence was identified in the literature regarding fee or copyright for any of the instruments. The original version of all assessment tools is available online in English except the CGS.

Floor/ceiling effects: No information was found about the number of respondents who achieve the lowest or highest possible score (quality score: zero for all questionnaires as shown in ).

Interpretability: As stated in the methods section, to achieve a positive score presentation of the mean and standard deviation in at least four relevant sub-groups of the patients as well as minimum important changes are required (Terwee et al., Citation2007). This information was not identified in any of the papers included in this systematic review. For both MM-CGI and MM-CGI-SF, the authors suggested an interpretation for the score based on mean and standard deviation (score above mean + SD = high personal grief, score below mean – SD = low personal grief)(Marwit & Meuser, Citation2002, Citation2005). The quality score for these two questionnaires was considered moderate (fair). No information was available for other assessment tools.

Discussion

This systematic review aimed to identify and critically examine, for the first time, available screening questionnaires that have been used for the identification of anticipatory grief among informal caregivers of dependants with dementia. The focus was on studies that specifically investigated validity, reliability and other measurement properties of questionnaires ().

Table 5. Comparison of assessment methods in reviewed studies.

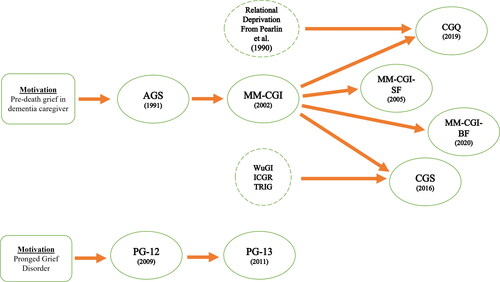

Seven assessment tools were identified in the literature for the assessment of pre-death grief in dementia caregivers and the time scale for the development of these methods is shown in . Six of these methods were specifically developed for the evaluation of pre-death grief in dementia caregivers. The first tool was AGS that was developed in 1991 and has been used to determine the construct validity of other methods. This method was followed by a multi-dimensional method in 2002 by Marwit and Meuser that resulted in the development of the MM-CGI. To enable this questionnaire to be more feasible in clinical practice two short forms of MM-CGI have subsequently been developed in 2005 and 2020 (MM-CGI-SF and MM-CGI-BF, respectively). Furthermore, selected items within the MM-CGI questionnaire in addition to other items from other psychometric tests were used as a basis for the development of new tools referred to as the CGS and CGQ. In parallel with the development of the above tools, the PG-12 was initially designed to measure prolonged grief in bereaved individuals.

Figure 2. The history of the development of assessment tools used for the evaluation of pre-death grief in dementia caregivers.

This review identified that well-designed methods were used during the development of the assessment tools. In terms of participants, nine of 12 studies recruited both spouses and adult children of dependants with dementia (). One study only recruited female spouses of those with dementia (Theut et al., Citation1991). Details of the recruited population were reported in the study by Kiely et al. (Kiely et al., Citation2008). Consequently, this review identifies the potential for selection bias in Theut et al. and Kiley et al’s studies (Kiely et al., Citation2008; Theut et al., Citation1991).

Five out of 12 studies were conducted in the USA, four in Singapore, one in Germany, one in Hong Kong and one in the UK (). Consequently, there may be a risk of bias associated with a limited spectrum of social and cultural mores associated with grief in each of the cultural settings in which they were set. To the best of our knowledge, no study was identified as being a validated assessment of pre-death grief in informal caregivers of dependants in Africa, the Middle East, India, Latin America or Eastern Europe. This indicates that the acceptability of these tools within the context of different cultures requires further examination. The only study that explicitly refers to culture was authored by Liew where the MM-CGI compared those in the USA and a multi-ethnic Asian population (Liew, Citation2016). The results indicate that ‘worries’ and ‘felt isolation’ were more pronounced during pre-death grief among the Asian population. Moreover, individuals from certain ethnicities (e.g. Malay) experienced more pre-death grief. Consequently, it is recommended that all assessment tools be validated in different ethnic or cultural groups to accurately determine their relative utility. This issue will have greater resonance as demographic ageing becomes more of a reality among minority ethnic communities where a consequence will be that dementia becomes more prevalent, and also in low to middle-income countries who are similarly going through important transitions concerning life-limiting conditions which include dementia.

Quality assessment of these questioners: As shown in , none of the studies on measurement properties could achieve a score of intermediate or higher methodological quality in all characteristics. Internal consistency, content validity and construct validity were widely assessed for the assessment tools in the papers. Cronbach’s α was calculated for all assessment tools in different papers. Test-retest reliability was only carried out in five papers (Cheng et al., 2019; Liew, Yap, et al., Citation2018a; Liew, Yeap, et al. Citation2018b; Liew & Yap, Citation2020; Meichsner et al., Citation2016b).

One of the concerns for the acceptability of the questionnaires in clinical settings was the length of the MM-CGI. In addition, AGS and MM-CGI have complicated calculations which might make them less acceptable for self-scoring. Moreover, no study referred to the concept of floor/ceiling effect.

Since all questionnaires are self-scoring instruments, inter-rater reliability was not applicable and was not studied in any of reviewed papers. None of the 12 papers formally analysed responsiveness. However, two papers were found where the effect of an intervention on pre-death grief assessment tools (MM-CGI and CGS) were studied (Meichsner & Wilz, Citation2018; Paun et al., Citation2015). These studies were not formally designed to measure responsiveness (minimum important change and smallest detectable change were not calculated), leading to scores of poor methodological quality. Interpretability was only discussed for MM-CGI and MM-CGI-SF.

Overall, among all instruments, MM-CGI has the highest quality score with four positive properties, one intermediate (interpretability) and one poor (responsiveness). The second-best quality score belongs to CGS with four positive quality scores and one poor quality measure for responsiveness.

Since there is no ‘gold standard’ for measurement of pre-death grief in dementia caregivers, the criterion validity could not have been assessed. This is a limitation of all studies included in this systematic review. There is a need to select a gold standard based on validity, reliability as well as consensus among the experts. MM-CGI seems to be a good candidate to serve as a gold standard. However, we were unable to find any published report regarding gold standard measure based on a consensus among specialists.

Agreement is another measurement property that reflects the reproducibility of an assessment tool (absolute measurement error). It is defined as the extent to which the scores on repeated measures are close to each other (Terwee et al., Citation2007). None of the reviewed articles had investigated agreement of the assessment tools. Therefore, our knowledge about absolute measurement error of all mentioned instruments (AGS, MM-CGI, MM-CGI-SF, MM-CGI-BF, PG-12, CGQ and CGS) is limited.

There are recent longitudinal studies that address the link between MM-CGI and caregiver burden and depression (Liew et al., Citation2019c). These studies are helpful and will pave the way to determine the usefulness of pre-death grief scoring on caregivers’ well-being. Furthermore, prospective longitudinal studies are required to determine the interpretability of MM-CGI and other pre-death grief measures in clinical practice. Specifically, studies of this nature will allow us to define clinically relevant subgroups of at-risk caregivers based on an assessment tool. Additionally, minimum important change can be calculated from prospective longitudinal studies. This is particularly important, as assessing pre-death grief in caregivers is useless without offering an effective intervention.

Implications for healthcare and future research

Clinical Practice: Anticipatory grief is an important component that contributes to caregiver burden (Collins & Kishita, Citation2020). However, assessment and screening for grief have not been considered in any clinical guidelines so far. As an example, the United Kingdom NICE guideline on dementia (Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers) published in 2018 did not mention pre-death grief or its assessment (NICE, Citation2018). Until now, the concept of pre-death grief among informal caregivers of dependants with dementia has remained an academic concept that has not been routinely incorporated in clinical practice. Its omission in clinical care has consequences for those affected but any future guidance developed must be grounded in robust evidence. This systematic review identified that the MM-CGI (and its short forms) and CGS represent accessible and relevant assessment tools that can be routinely adopted in clinical practice to screen for anticipatory grief and then offer support and bereavement intervention for those who stand to benefit (Meichsner et al., Citation2016a; Citation2019; Meichsner & Wilz, Citation2018). Moreover, this should be extended for those dependants with dementia who are cared for in, settings other than at home for example those in nursing and residential care homes. As suggested by Liew et al. (Citation2019c) in settings where routine use of pre-death grief assessment is difficult there may be a role of using demographic information (i.e. risk factors of high grief) as a means of quick screening to identify those who are more likely to have anticipatory grief-related issues and only then administer more detailed grief scale to this high-risk group. Thus, the presence of risk factors such as severe forms of dementia, behavioural problems in the person with dementia, spousal caregivers and daily caregiving can be used as a screening tool before more formal assessment of pre-death grief in dementia caregivers (Liew et al., Citation2019c).

The ultimate aim for the assessment of anticipatory grief should be supporting caregivers of dependants with dementia by offering early intervention. Although previous reports have outlined that the three dimensions in MM-CGI may potentially be useful to guide the focus of intervention this area awaits further research and clarifications (Chan et al., Citation2020; Sanders et al., Citation2007).

This systematic review has identified two approaches to assess grief among informal caregivers of dependants with dementia. The first identifies specific aspects of grief in informal caregivers that lend themselves to therapy approaches for example CBT. The second approach presents an instrument that measures the shared aspects of complicated grief in informal caregivers. The CGS and PG-12 have been developed using the former and the latter approaches respectively. Research that compares these two approaches will enable us to understand if interventions lead to positive outcomes.

Limitations: Although this systematic review made use of a wide range of search terms during scoping of literature, it is limited to academic journals and does not include the grey literature and governmental and institutional reports. Although we expect that most studies on validation of assessment tools are published in academic peer reviewed journals, future reviews can include an extended search of the literature.

Conclusions

It is an immutable fact that the number of people living with dementia in many societies across the world is increasing with a significant impact on their informal caregivers (Sleeman et al., Citation2019). Anticipatory grief among these caregivers may lead to long-term consequences for their physical and psychosocial well-being with concomitant implications for health providers (Coelho et al., Citation2018). However, pre-death grief has only recently been acknowledged as a measurable variable among these caregivers and warrants greater consideration with services to manage their concerns, so they remain surmountable. Since anticipatory grief is multi-faceted it is challenging to assess using a simple questionnaire. Nevertheless, existing tools such as the MM-CGI and CGS encapsulate different aspects of anticipatory grief and therefore have the potential for use in routine clinical practice. Future research could focus on measures of pre-death grief that predict long-term dysfunction and response to interventions in informal caregivers of dependants with dementia.

Declarations

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the development of the study question. TD performed the literature search, study selection, data extraction, quality assessment, data analysis and wrote the manuscript. JK participated in study selection. All authors reviewed earlier versions of the manuscript and read and approved the final manuscript.

Data management and sharing

Further information is available at request from the first author.

Ethical approval

As a systematic review, the study did not directly involve human participants and required no approval from an Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board.

Guarantor

First and last author

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr Alireza Mani (UCL) and Dr Lisa Brighton (King’s College London) on their views and contribution in the conduct of this review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Blandin, K., & Pepin, R. (2017). Dementia grief: A theoretical model of a unique grief experience. Dementia (London, England), 16(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301215581081

- Carduff, E., Finucane, A., Kendall, M., Jarvis, A., Harrison, N., Greenacre, J., & Murray, S. A. (2014). Understanding the barriers to identifying carers of people with advanced illness in primary care: Triangulating three data sources. BMC Family Practice, 15(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-48

- Chan, D., Livingston, G., Jones, L., & Sampson, E. L. (2013). Grief reactions in dementia carers: A systematic review. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.3795

- Chan, I., Yap, P., Wee, S. L., & Liew, T. M. (2020). The three dimensions of caregiver grief in dementia caregiving: Validity and utility of the subscales of the Marwit-Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 35(2), 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5238

- Cheng, S. T., Ma, D. Y., & Lam, L. C. W. (2019). A brief measure of predeath grief in dementia caregivers: The Caregiver Grief Questionnaire. International Psychogeriatrics, 31(8), 1099–1107. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610219000309

- Cheung, D. S. K., Ho, K. H. M., Cheung, T. F., Lam, S. C., & Tse, M. M. Y. (2018). Anticipatory grief of spousal and adult children caregivers of people with dementia 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1117 Public Health and Health Services 11 Medical and Health Sciences 1103 Clinical Sciences. BMC Palliative Care, 17(1), 124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0376-3

- Coelho, A., De Brito, M., & Barbosa, A. (2018). Caregiver anticipatory grief: Phenomenology, assessment and clinical interventions. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care, 12(1), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000321

- Coelho, A., Silva, C., & Barbosa, A. (2017). Portuguese validation of the Prolonged Grief Disorder Questionnaire-Predeath (PG-12): Psychometric properties and correlates. Palliative & Supportive Care, 15(5), 544–553. Cambridge University Press,https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951516001000

- Collins, R. N., & Kishita, N. (2020). Prevalence of depression and burden among informal care-givers of people with dementia: A meta-analysis. Ageing and Society, 40(11), 2355–2392. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X19000527

- Dempsey, M., & Baago, S. (1998). Latent grief: The unique and hidden grief of carers of loved ones with dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 13(2), 84–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/153331759801300206

- Ellis-Smith, C., Evans, C. J., Bone, A. E., Henson, L. A., Dzingina, M., Kane, P. M., Higginson, I. J., & Daveson, B. A., BuildCARE. (2016). Measures to assess commonly experienced symptoms for people with dementia in long-term care settings: A systematic review. BMC Medicine, 14(1), 38 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-016-0582-x

- Frank, J. B. (2008). Evidence for grief as the major barrier faced by Alzheimer caregivers: A qualitative analysis. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias, 22(6), 516–527. SAGE Publications Inc.,https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317507307787

- Gilsenan, J., Gorman, C., & Shevlin, M. (2022). Exploratory factor analysis of the caregiver grief inventory in a large UK sample of dementia carers. Aging & Mental Health, ), 26(2), 320-327. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1839856

- Holley, C. K., & Mast, B. T. (2009). The impact of anticipatory grief on caregiver burden in Dementia caregivers. The Gerontologist, 49(3), 388–396. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnp061

- Holm, M., Alvariza, A., Fürst, C.-J., Öhlen, J., & Årestedt, K. (2019). Psychometric evaluation of the anticipatory grief scale in a sample of family caregivers in the context of palliative care. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 17(1), 42 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-019-1110-4

- Kiely, D. K., Prigerson, H., & Mitchell, S. L. (2008). Health care proxy grief symptoms before the death of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 16(8), 664–673. https://doi.org/10.1097/JGP.0b013e3181784143

- Large, S., & Slinger, R. (2015). Grief in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia: a qualitative synthesis. Dementia (London, England), 14(2), 164–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301213494511

- Liew, T. M. (2016). Applicability of the pre-death grief concept to dementia family caregivers in Asia. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(7), 749–754. John Wiley and Sons Ltd,https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4387

- Liew, T. M., Yap, P., Luo, N., Hia, S. B., Koh, G. C.-H., & Tai, B. C. (2018a). Detecting pre-death grief in family caregivers of persons with dementia: Measurement equivalence of the Mandarin-Chinese version of Marwit-Meuser caregiver grief inventory. BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 114 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0804-5

- Liew, T. M., Yeap, B. I., Koh, G. C.-H., Gandhi, M., Tan, K. S., Luo, N., & Yap, P. (2018b). Detecting predeath grief in family caregivers of persons with dementia: Validity and utility of the marwit-meuser caregiver grief inventory in a multiethnic Asian population. The Gerontologist, 58(2), e150–e159. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx097

- Liew, T. M., & Lee, C. S. (2019). Reappraising the Efficacy and Acceptability of Multicomponent Interventions for Caregiver Depression in Dementia: The Utility of Network Meta-Analysis. The Gerontologist, 59(4), e380–e392. 16https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny061

- Liew, T. M., Tai, B. C., Yap, P., & Koh, G. C. (2019a). Contrasting the risk factors of grief and burden in caregivers of persons with dementia: Multivariate analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry, 34(2), 258–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5014

- Liew, T. M., Tai, B. C., Yap, P., & Koh, G. C. (2019b). Comparing the Effects of Grief and Burden on Caregiver Depression in Dementia Caregiving: A Longitudinal Path Analysis over 2.5 Years. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 20(8), 977–983.e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2018.11.016

- Liew, T. M., Tai, B. C., Yap, P., & Koh, G. C. (2019c). Development and validation of a simple screening tool for caregiver grief in dementia caregiving. BMC Geriatrics, 19(1), 54 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1070-x

- Liew, T. M., Tai, B. C., Wee, S. L., Koh, G. C., & Yap, P. (2020). The Longitudinal Effects of Caregiver Grief in Dementia and the Modifying Effects of Social Services: A Prospective Cohort Study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(10), 2348–2353. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16717

- Liew, T. M., & Yap, P. (2020). A Brief, 6-Item Scale for Caregiver Grief in Dementia Caregiving. The Gerontologist, 60(1), e1–e10. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gny161 PMID: 30544229.

- Lwi, S. J., Ford, B. Q., Casey, J. J., Miller, B. L., & Levenson, R. W. (2017). Poor caregiver mental health predicts mortality of patients with neurodegenerative disease. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 114(28), 7319–7324. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1701597114

- Marwit, S. J., & Meuser, T. M. (2002). Development and initial validation of an inventory to assess grief in caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease. The Gerontologist, 42(6), 751–765. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/42.6.751

- Marwit, S. J., & Meuser, T. M. (2005). Development of a short form inventory to assess grief in caregivers of dementia patients. Death Studies, 29(3), 191–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180590916335

- Mayeux, R., & Stern, Y. (2012). Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine, 2(8), a006239–a006239. https://doi.org/10.1101/cshperspect.a006239

- Meichsner, F., Köhler, S., & Wilz, G. (2019). Moving through predeath grief: Psychological support for family caregivers of people with dementia. Dementia (London, England), 18(7-8), 2474–2493. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217748504

- Meichsner, F., Schinköthe, D., & Wilz, G. (2016a). Managing Loss and Change: Grief Interventions for Dementia Caregivers in a CBT-Based Trial. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 31(3), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317515602085

- Meichsner, F., Schinköthe, D., & Wilz, G. (2016b). The Caregiver Grief Scale: Development, Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis, and Validation. Clinical Gerontologist, 39(4), 342–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2015.1121947

- Meichsner, F., & Wilz, G. (2018). Dementia caregivers’ coping with pre-death grief: effects of a CBT-based intervention. Aging & Mental Health, 22(2), 218–225. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2016.1247428

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G., The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Mulligan, E. A. (2010). Measuring predeath grief among dementia caregivers. Alzheimer’s & Dementia, Elsevier BV, 6(4), S314. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2010.05.1026

- NICE. (2018). ‘Recommendations | Dementia: Assessment, management and support for people living with dementia and their carers | Guidance | NICE’, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. NICE, p. 1. Retrieved December 11, 2019, from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng97/chapter/Recommendations#interventions-to-promote-cognition-independence-and-wellbeing.

- Paun, O., Farran, C. J., Fogg, L., Loukissa, D., Thomas, P. E., & Hoyem, R. (2015). A Chronic Grief Intervention for Dementia Family Caregivers in Long-Term Care. Western Journal of Nursing Research, 37(1), 6–27. SAGE Publications Inc.,https://doi.org/10.1177/0193945914521040

- Pearlin, L. I., Mullan, J. T., Semple, S. J., & Skaff, M. M. (1990). Caregiving and the stress process: An overview of concepts and their measures. The Gerontologist, 30(5), 583–594. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/30.5.583

- Prigerson, H. G., Horowitz, M. J., Jacobs, S. C., Parkes, C. M., Aslan, M., Goodkin, K., Raphael, B., Marwit, S. J., Wortman, C., Neimeyer, R. A., Bonanno, G. A., Bonanno, G., Block, S. D., Kissane, D., Boelen, P., Maercker, A., Litz, B. T., Johnson, J. G., First, M. B., & Maciejewski, P. K. (2009). Prolonged Grief Disorder: Psychometric Validation of Criteria Proposed for DSM-V and ICD-11 . PLoS Medicine, 6(8), e1000121 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000121

- Prigerson, H. G., Maciejewski, P. K., Reynolds, C. F., Bierhals, A. J., Newsom, J. T., Fasiczka, A., Frank, E., Doman, J., & Miller, M. (1995). Inventory of complicated grief: A scale to measure maladaptive symptoms of loss. Psychiatry Research, 59(1-2), 65–79. Elsevier, https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-1781(95)02757-2

- Sanders, S., Marwit, S. J., Meuser, T. M., & Harrington, P. (2007). Caregiver grief in end-stage dementia:using the Marwit and Meuser Caregiver Grief Inventory for assessment and intervention in social work practice . Soc Work Health Care, 46(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1300/J010v46n01_04

- Sleeman, K. E., de Brito, M., Etkind, S., Nkhoma, K., Guo, P., Higginson, I. J., Gomes, B., & Harding, R. (2019). The escalating global burden of serious health-related suffering: Projections to 2060 by world regions, age groups, and health conditions. The Lancet Global Health, 7(7), e883–e892. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(19)30172-X

- Terwee, C. B., Bot, S. D. M., de Boer, M. R., van der Windt, D. A. W. M., Knol, D. L., Dekker, J., Bouter, L. M., & de Vet, H. C. W. (2007). Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 60(1), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012

- Theut, S. K., Jordan, L., Ross, L. A., & Deutsch, S. I. (1991). Caregiver’s anticipatory grief in dementia: a pilot study. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 33(2), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.2190/4KYG-J2E1-5KEM-LEBA

- Toot, S., Swinson, T., Devine, M., Challis, D., & Orrell, M. (2017). Causes of nursing home placement for older people with dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Psychogeriatrics, 29(2), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216001654

- Ying, J., Yap, P., Gandhi, M., & Liew, T. M. (2018). Iterating a framework for the prevention of caregiver depression in dementia: A multi-method approach. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(8), 1119–1130. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610217002629