Abstract

Objectives

With a lack of existing comprehensive reviews, the aim of this mixed-method systematic review was to synthesise the evidence on the early impacts of the pandemic on unpaid dementia carers across the globe.

Methods

This review was registered on PROSPERO [CDR42021248050]. PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, Scopus and Web of Science were searched from 2020 to July 2021. Studies were included if they reported on the different impacts of the pandemic on unpaid dementia carers aged 18+, with papers published in English, German, Polish, or Spanish. A number of research team members were involved in the selection of studies following PRISMA guidance.

Results

Thirty-six studies (43 papers) from 18 countries reported on the early impact of the pandemic on unpaid dementia carers. Impacts were noted on accessing care and support; carer burden; and well-being. Studies found that carers had limited access to care and support services, increased workload, enhanced feelings of social isolation, and reduced wellbeing. Specifically, reductions in access to care and support increased carer’s unpaid caring tasks, removing any opportunities for temporary respite, and thus further increasing carer burden and reducing mental well-being in many.

Conclusions

The needs of unpaid dementia carers appear to have increased during the pandemic, without adequate support provided. Policy initiatives need to enable better mental health support and formal care provision for unpaid carers and their relatives with dementia, whilst future research needs to explore the long-term implications of carer needs in light of care home restrictions and care delivery.

Of the estimated 55 million people living with dementia worldwide (World Health Organisation (WHO), Citation2021), many receive support from family members or friends, who are providing free and unpaid care to their relatives with dementia. Based on 2015 estimates, this contribution of unpaid care globally was equated to 82 billion hours, each year (ADI, Citation2018). Whilst providing a great deal of support for their relatives, unpaid carers are often overlooked in receiving support themselves (Clemmensen et al., Citation2021). Already before the COVID-19 pandemic, many unpaid carers experienced high levels of burden and poor mental well-being as a result (Sutcliffe et al., Citation2017). This increases as dementia advances, due to higher care needs of the person with dementia, and can often be a contributor for people with the condition to utilise more formal care including entering a care home (Kerpershoek et al., 2020).

People living with dementia have been particularly vulnerable and susceptible to the COVID-19 in this ongoing pandemic, due to their predominantly increased age (Banerjee et al., 2020) and frequent lack of understanding public health restrictions (Giebel et al., Citation2021a; Tuijt et al., Citation2021a). This has not only affected the person living with the condition, but also their support network which tries to keep them safe.

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided new care challenges and additional care needs for people with dementia, with social care and social support services primarily closed or operating at reduced levels (Giebel et al., Citation2021b). As a longitudinal survey into dementia social care service delivery across the UK has shown, the vast majority of all types of services immediately closed down from March 2020 onwards, and recovered only minimally in the first six months of the pandemic (Giebel et al., Citation2021b). Early evidence seems to indicate that these reductions in external care support have led unpaid carers to take on additional care roles, on top of their previous caring roles (Rising et al., Citation2022; Sriram et al., Citation2021). Additional caring duties and hours without any reprise appear to be linked to poorer mental health and well-being in carers, with a growing body of evidence reporting on the wider exacerbated mental health needs of unpaid carers since the pandemic (Rainero et al., Citation2020; Vaitheswaran et al., Citation2020). This link between lack of support and poorer mental health has been supported by pre-COVID-19 research into unmet needs. Growing evidence has highlighted the myriad of unmet needs experienced by unpaid dementia carers (Black et al., Citation2013; Janssen et al., Citation2019; Zwingmann et al., Citation2019) – Zwingmann et al. (Citation2019) for example reported three quarters of an unpaid dementia carer sample in Germany to experience unmet needs in regards to their caring role, with many having experienced multiple unmet needs. These could easily be met by more adequate social care and social support services, which are often too difficult to be accessed by carers.

Despite a bourgeoning evidence base into the impacts of the pandemic on unpaid dementia carers, to date, it appears that no single systematic review has evaluated and synthesised the existing literature on the wider impacts of the pandemic on these unpaid carers. Instead, a rapid systematic review from early 2021 has looked at the psychological impact only, reporting negative effects of the pandemic on unpaid carers’ mental health, including depression and anxiety (Hughes et al., Citation2021). The review did not explore the wider impacts of the pandemic, however, on carers’ access to care, which may be linked to reductions in health and well-being. Other systematic reviews on COVID-19 and dementia have solely focused on people with dementia and specific outcomes, such as cognition and mental health (Suarez-Gonzalez et al., Citation2021), or included editorials or letters, as opposed to primary research, very early in the pandemic (Bacsu et al., Citation2021), providing little insights into the wider impacts on unpaid carers.

Therefore, the aim of this mixed-method systematic review was to understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on unpaid dementia carers, focusing on carers’ health and well-being as well as health and social care access in the early stages of the pandemic. There is a continued need for understanding how the pandemic is impacting on unpaid carers, not just for dementia, but also for other conditions. COVID-19 is still affecting people’s lives, so that knowledge from the early stages of the pandemic can help shaping care and support from Governments and care services to meet the needs of the unpaid workforce of some of the most vulnerable populations of our societies during the current pandemic as well as moving forward.

Methods

The protocol of this systematic review was registered on PROSPERO [ID: CRD42021248050]. Two unpaid carers (HT, JC) advised on the development of this review, were interpreting the findings jointly with other team members, read through drafts of the manuscript, and provided feedback. Due to the high number of included studies, the results are presented in two parts: Part I focusing on people living with dementia and Part II focusing on unpaid carers.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Quantitative (observational, survey and neuropsychological assessment studies, as well as RCTs) and qualitative studies (interview and focus group studies) were included in this mixed-method review. Study inclusion involved: people living with dementia aged 18+ either living in the community or living in a care home; unpaid carers of people living with dementia aged 18 and older. Studies were excluded if people cared for had no diagnosis of dementia; carers had a formal and paid caring role for someone living with dementia; were aged 17 and younger. Only empirical studies were included in this review (i.e. literature reviews were not included). No limits were placed on the type or stage of dementia.

Search strategy

We searched the following databases from 2020 (when literature first started to be published on the COVID-19 pandemic) to July 2021: PubMed, CINAHL, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science. Restrictions were applied to specify studies written in English, German, Polish, or Spanish language. The search terms included Covid-19 and a combination of MeSH Terms and search terms relating to dementia (e.g. dementia, Alzheimer, cognitive impairment). The syntax was customized for individual databases according to each database specific conventions. The search terms were developed in consultation with an experienced librarian and piloted before being used: ‘Covid-19 AND (“dementia”[MeSH Terms] OR “dement*”[All Fields] OR “alzheimer*”[All Fields] OR “neurocognitive disorders”[MeSH Terms] OR “cognitive impairment” [All Fields] OR “lewy bod*”[All Fields] OR “Creutzfeldt-Jakob”[All Fields] OR “Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration”[All Fields] OR “Huntington*”[All Fields]’).

Data extraction

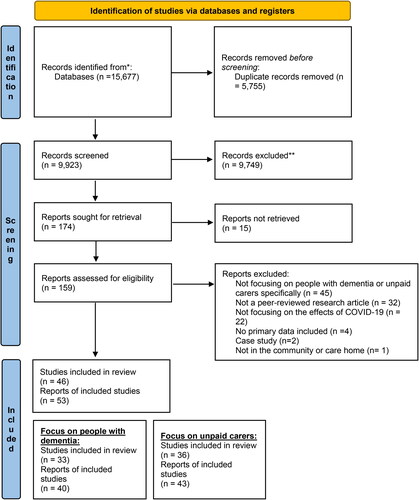

Citations were merged in Endnote and transferred into Excel after all duplicates were removed. All titles and abstracts of all papers were screened, with the task split across three reviewers due to the large number of search results, involving one reviewer screening 60% of results (EW), and two reviewers each screening 20% of results respectively (JRT, KL). Ten percent of the sample were screened by an independent additional reviewer (KHL), and any discrepancies about included papers were discussed between the reviewers until consensus was achieved. Following Stage 1 screening, each full paper was read by two reviewers overall, with the task split among four reviewers (CVT, JRT) screening 50% of the full papers. Again, this was based on the large number of Stage 1 inclusions (also see for PRISMA flowchart of citations and included studies). Similar to Stage 1, any discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached. All papers which belonged to one study were included, if they were showing up in our searches, as each paper reported on different angles of the findings from a study.

Figure 1. PRISMA flowchart.

From: Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021;372:n71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n71

One researcher (EW) extracted the following data, which was checked by another researcher (CG): Country, population, focus (which of the 5 impacts), design, measures, qualitative themes OR quantitative outcomes, setting, and time period of data collection.

Quality assessment

Study quality was assessed using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields (QualSyst) (Kmet et al., Citation2004) by two researchers independently. QualSyst has 14 criteria to assess the criteria of quantitative studies, and 10 criteria for qualitative studies. Each criterion can be scored from ‘0′ (not addressed) to ‘2′ (fully addressed), with an additional option of ‘not applicable’. The criteria are outlined in . A total percentage score was provided, with 100% indicating good quality, and a score of 75% the threshold for a paper to meet good quality. Any discrepancies between ratings were discussed jointly, with a third researcher being consulted in cases which were unclear. Quality ratings did not influence study selection, but were used to inform discussions of findings.

Table 1. Overview of included studies.

Data synthesis

Data were synthesised by two researchers (EW, CG), with extracted data focusing on country, population, type of study, outcome measures (for quantitative studies only), and focus. In discussion with all team members, studies were then categorised into three different outcomes based on discussion amongst the entire research team.

Results

Overview of included studies and data selection

159 full texts were read through for inclusion for the overarching review (Part I and II), with 36 studies reported in 43 papers specifically reporting on the impact of the pandemic on unpaid dementia carers. Studies were conducted across 18 countries, including Greece, Italy, Singapore, India, Poland, and the UK. Six studies were from low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Azevedo et al., Citation2021; Borelli et al., Citation2021; Cohen et al., 2021a, 2021Citationb; Rajagopalan et al., Citation2022; Vaitheswaran et al., 2021). The majority of studies (n = 25) were quantitative, including retrospective surveys enquiring about changes since the pandemic (Carpinelli Mazzi et al., Citation2020; Pongan et al., Citation2021) and assessments of mental health and carer burden (i.e. Hwang et al., Citation2021; Losada et al., Citation2021). Qualitative studies (n = 8) reported on remote interviews with unpaid carers about their experiences of providing care during the pandemic and their concerns (i.e. Rising et al., Citation2022; Sriram et al., Citation2021). Three mixed-method studies reported on different impacts, including carer burden and access to care (Dassel et al., Citation2021; Rajagopalan et al., Citation2022; Savla et al., Citation2021). All studies focused on unpaid carers of community-residing people living with dementia, with Borg et al. (Citation2021) focusing on both community and care homes.

Synthesis of results

The 36 studies were categorised into three outcomes: Impact on access to care and support; Impact on carer burden; and Impact on well-being (which was sub-categorised into mental well-being and social health). Studies were not single categorised, with many covering multiple impacts.

Impact on access to care and support

The impact of the pandemic on access to health or social care was reported in 14 studies, all of which identified reductions in access for unpaid carers, leaving many people without access to vital support. The availability of support services also appeared to be location-dependent, with level of support services varying greatly between areas, based on UK reports (Giebel et al., 2021a; West et al., Citation2021). Carers reported reduced access to all areas of support services, including local day centres, memory cafes, support groups and respite care worldwide (Carpinelle-Mazi et al., 2021a; Cohen et al., 2021a; Giebel et al., Citation2021e; Rajagopalan et al., Citation2022). Most of those support the person with dementia directly and the unpaid carer indirectly, whilst peer support groups can support either (e.g. Giebel et al., Citation2020; Sriram et al., Citation2021). Following up with carers at two subsequent time points, Giebel et al. (Citation2021b) identified a small upward trend in access to social support services again in the months following the first nationwide lockdown in the UK, with access to paid carers being the least affected by the pandemic. Paid home care may have been the least impacted service because of the difficult decisions carers needed to make during the pandemic, whereby some carers suspended paid care visits due to fears of transmitting COVID-19, while others felt they could not cope without paid care and were fearful of reobtaining it post-pandemic (Giebel et al., Citation2020). Similar findings in access to care during the pandemic were reported in other studies (e.g. Cohen et al., Citation2020a; Dassel et al., Citation2021; Rajagopalan et al., Citation2022; Sriram et al., Citation2021; Tuijt et al., Citation2021b). However, there were some reports of local area agencies on ageing checking in on carers more frequently than before COVID-19 and nutrition services delivering extra meals (e.g. Savla et al., 2020).

Difficulties with accessing care homes due to the increased care needs of the care-recipient was reported in one study (Giebel et al., Citation2021c). In this UK study, carers expressed that finding care home places was challenging due to inflated fees and care home closures, with some carers opting for a care home place far away.

Access to healthcare services was explored in some studies. In Israel, Werner et al. (Citation2021) found that 50% of the carers who needed to see a GP or specialist had forgone at least one of these services. In Argentina, carers reported to have discontinued all sorts of cognitive and physical therapies (Cohen et al., Citation2020a). Similarly, in an interview study by Tuijt et al. (Citation2021b), carers reported avoiding healthcare settings and services due to the risk of coronavirus transmission and fears of overburdening the NHS. However, they also reported proactive care on the onset of COVID-19, whereby a variety of healthcare professionals would telephone to enquire how the person living with dementia and their family were managing, although this was not the case for all participants.

Some studies reported that few care services had adapted by providing remote support during the early stages of the pandemic. However, even when remote support was provided, carers felt it was not a direct replacement for the in-person contact and care that was offered and utilised pre-pandemic (Giebel et al., Citation2021d; Sriram et al., Citation2021). Similar issues were reported for remote healthcare consultations, which were often organised and handled by the carer (Tuijt et al., Citation2021b). There were also reports of digital barriers or exclusion from accessing remote healthcare and support services (e.g. Giebel et al., Citation2021d; Tuijt et al., Citation2021b).

Impact on carer burden

Twenty-eight studies documented the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on carer burden, with many noting increases in caring responsibilities or time dedicated to care (e.g. Borges-Machado et al., Citation2020; Tam et al., Citation2021; Tsapanou et al., Citation2021). A range of tools were used to measure carer burden in quantitative studies (n = 20); however, most relied on self-reports rather than validated measures (e.g. Boutoleau-Bretonnière et al., 2020; Cohen et al., 2021; Helvaci Yilmaz et al., Citation2021; Tsapanou et al., Citation2021). Two studies utilised the Zarit Burden Interview (Borelli et al., Citation2021; Borg et al., Citation2021). These studies reported high levels of burden, with Borg et al. (Citation2021) noting 32.4% of carers’ scores indicated severe burden. Two studies used the Caregiver Burden Inventory (CBI; Altieri & Santangelo, Citation2020; Penerai et al., 2020). In a pre-post study on the impact of confinement during the pandemic on carers in Italy, Penerai et al. (2020) found statistically significant changes in CBI scores pre- and during lockdown, with an increase of approximately 10% of carers at risk for burning out. Large effect sizes were reported for total CBI scores and physical burden, and a medium effect size in time dependence and developmental burden. One study used the Care-related Quality of Life Instrument, reporting significant increases in subjective burden (Borges-Machado et al., Citation2020).

Impacts on carer burden have been associated with stage of dementia across quantitative studies, with Cohen et al. (2021a) noting levels of carer burden being particularly high for carers of people with advanced dementia after four weeks of quarantine. Significant differences in the influence of diagnostic type of dementia on levels of burden have not been observed (Altieri et al., 2021; Boutoleau-Bretonnière et al., 2020). However, Boutoleau-Bretonnière et al. (2020) did report that increases in burden occurred among carers of people living with behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia regardless of changes in neuropsychiatric symptoms, whereas increases in burden among carers of people living with Alzheimer’s disease was related to changes in neuropsychiatric symptoms.

Findings from qualitative (n = 5) and mixed-method (n = 1) studies show that carers attributed increases in burden to the suspension of care services, a lack of usual support from other family members, heightened feelings of responsibility and a need to take extra precautions to avoid infection (Rajagopalan et al., Citation2022; Rising et al., Citation2022; Sriram et al., Citation2021; Tuijt et al., Citation2021; Vaitheswaran et al., Citation2020; West et al., Citation2021). Some quantitative studies reported that carer burden was amplified by changes in the care needs of the person living with dementia due to symptom advancement during lockdown periods (see Part I). In Brazil, Borelli et al. (Citation2021) found carers of people living with dementia whose cognition had worsened since March 2020 reporting significantly increased burden.

The ongoing nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and possibility of future lockdown periods have implications for carer burden. In Greece, Tsapanou et al. (Citation2021) reported high levels of physical and psychological burden, which increased significantly from an initial lockdown to a second prolonged lockdown period.

Impact on well-being

Twenty-six studies reported on the impact of the pandemic on the wellbeing of carers, focusing specifically upon mental well-being and social wellbeing.

Impact on mental wellbeing

All 26 studies described the negative impact of the pandemic on carers’ mental well-being. In a survey in Italy, Rainero et al. (2020) found 45.9% of carers reported increases in anxiety and 18.6% reported increases in depression since quarantine. Similarly, in France, Borg et al. (Citation2021) found half of carers exhibited poor mental health, including depression, anxiety, or self-reported stress. Studies typically focused upon anxiety, depression and stress among carers (e.g. Altieri & Santangelo, Citation2021; Carpinelli Mazzi et al., Citation2020; Giebel et al., 2021f; Hwang et al., Citation2021; Rainero et al., 2020; Zucca et al., 2021); however, some studies also reported negative effects upon sleep and eating disorders during home confinement (e.g. Carcavilla et al., Citation2021; Cohen et al., Citation2020b). Validated measures of depression and anxiety included the GAD-7 (Alexopoulos et al., Citation2021; Hwang et al., Citation2021; Pongan et al., Citation2021), Italian version of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Altieri & Santangelo, Citation2021), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Hwang et al., Citation2021), Zung’s depression and anxiety assessment scales (ZDAAS; Carpinelli Mazzi et al., Citation2020). Stress was primarily measured using the Perceived Stress Scale (Carpinelli Mazzi et al., Citation2020; Rusowicz et al., Citation2021).

The negative impact of the pandemic on carer’s wellbeing and mental health was also noticed in qualitative (n = 4) and mixed-method studies (n = 1). Many studies reported on the increased anxiety, fear, depression or stress levels (e.g. Rajagopalan et al., Citation2022; Rising et al., Citation2022; Sriram et al., Citation2021; West et al., Citation2021). Most commonly the anxiety/fear was related to becoming infected with COVID-19 and/or infecting of a person with dementia (e.g. Rising et al., Citation2022; Sriram et al., Citation2021). The increased anxiety of carers was related to managing following the restrictions by person with dementia or other member of family/society (e.g. Sriram et al., Citation2021); worry about the condition of the person with dementia after pandemic (Giebel et al., Citation2021d) or ongoing fear for future (Hanna et al., Citation2021). In the UK, some carers have reported feeling of being strained and losing their freedom (West et al., Citation2021) or loss of hope (Hanna et al., Citation2021) and loss of control feelings (Giebel et al., Citation2021d). Carers from India have been also reporting increased negative feelings, including feeling lost (Rajagopalan et al., Citation2022). Carers in the USA reported putting their own needs on hold due to the increased demands of caregiving (Rising et al., Citation2022).

Several studies have also reported on coping with providing care during the pandemic, used strategies and self-protective factors. Losada et al. (Citation2021) study presented that majority of carers considered that they coped well whereas Salva et al. (2021) reported that active coping strategies were used by 57% of carers. The frequently used coping strategies were related to self-care or described, i.e. by taking up some new or creative activities (e.g. Tulloch et al., Citation2021; West et al., Citation2021); reading, doing house chores (e.g. Rising et al., Citation2022), maintaining social connections or being able to get out (Tuijt et al., Citation2021). Factors including effective communication during pandemic, existing support networks, coping mechanisms and lifestyle factors including exercises or access to green spaces were reported as factors contributing to resilience of carers by Hanna et al. (Citation2022).

A few studies focussed on positive aspects of providing care during the pandemic. In an Australian study, carers noted that providing care during the pandemic revealed their inner strength as well as their priorities and values having changed, whilst the relationship between them and care recipients deepened (Tulloch et al., Citation2021). Being close and spending more time with loved ones was also presented in other studies (Rising et al., Citation2022; Sriram et al., Citation2021). Similarly, some carers in the Losada et al. (Citation2021) study reported an increase in positive emotions such as hope and happiness during the pandemic. The pandemic has also offered an opportunity to rest to some carers (West et al., Citation2021).

Impact on social health

The impact of the pandemic on social health was reported in six studies. These studies reported enhanced levels of social isolation and loneliness among carers during the pandemic. In a survey of 395 carers in Canada, Tam et al. (Citation2021) found that most carers felt isolated, left out, and lacking companionship some of the time or often, with 89% also feeling more or somewhat more isolated since the pandemic. A sense of isolation and abandonment was also reported in an Italian study, but less frequently than other symptoms of stress (Zucca et al., 2021). There was a notable lack of studies using validated measures of social health.

Social isolation and loneliness were also documented in qualitative studies. In the USA, participants reported that the inability to socialise with their community, travel for leisure, and see family members were primary issues (Rising et al., Citation2022). In an interview study in the UK, carers expressed feelings of loneliness during a period of lockdown which they attributed to their main social contact being the person living with dementia whom they cared for (Hanna et al., Citation2021). Research with carers from minority ethnic backgrounds in the UK indicated that social interaction was also widely reduced, often due to fears of contracting COVID-19 and transmitting it to loved ones (West et al., Citation2021). These carers also discussed being unable to attend communal culturally relevant events as a negative impact of the pandemic, such as church or temple.

In one study, the majority of carers reported turning to technology to connect with others (Tam et al., Citation2021). However, only 19% of carers reported that using technology to connect with others felt the same as interacting with them in-person.

Quality ratings

All but three studies were of good quality (see and ), with scores ranging from 0.65 to 1.00.

Table 2. Quality assessment ratings for quantitative studies.

Table 3. Quality assessment ratings for qualitative studies.

Discussion

This appears to be the first comprehensive systematic review on the early impacts of the pandemic on unpaid dementia carers. Whilst a previous systematic review has explored the impacts on health only (Hughes et al., Citation2021), this review purposefully synthesised the evidence into different aspects of the lives of unpaid carers, including mental health and well-being, as well as access to care for themselves and their relatives, and the impacts this in turn had on their health and mental health. Substantial evidence generated in the early stages of the pandemic has shown the negative effects of the pandemic on accessing dementia-related care and support (Dassel et al., Citation2021; Werner et al., Citation2021), which led to increased caring duties for family members and friends (Giebel et al., Citation2020), subsequently perniciously affecting carers’ mental health and well-being (Carpinelli Mazzi et al., Citation2020; Tam et al., Citation2021).

Accessing care and support is not only vital for the person living with the condition, but also for the unpaid carer – both of whom have experienced increased barriers in doing so since the pandemic (also see Part I). The majority of research has highlighted social care and social support reductions since the pandemic, primarily focusing on community care, with some research indicating early care home access issues (Giebel et al., Citation2021c) and health care utilisation barriers (Tuijt et al., Citation2021). Being unable to access care, either for themselves via peer support groups for example, or predominantly for their relative with dementia to gain some temporary respite from caring duties (Tretteteig et al., Citation2017), has wide-ranging implications for the carer. Without any respite or time off from caring, carers have been found to be more likely to be burned out (Cohen et al., 2021b). Whilst evidence reported in this review has already highlighted increased burden for many early on, the continuing nature of the pandemic is likely having long-term repercussions on carers leading to burnout. Since the beginning of the pandemic, some services have started to resume face-to-face care delivery, whilst this remains highly varied and patchy across countries, as well as regions and local areas, with some people being too cautious to resume face-to-face meetings and support again after an extensive period of restrictions. Future research needs to follow up carers and explore the long-term effects, however, early evidence from this review strongly indicates a greater need to adequately and equitably support unpaid carers in their roles, and as individuals themselves.

These effects have not only been noted regarding carer burden, but also more widely for mental well-being. All studies but one (Tulloch et al., Citation2021) noted at least some aspects of negative impacts on the mental and social health of unpaid carers, particularly focusing on depression, anxiety, and stress, as well as social isolation and loneliness. Tulloch et al. (Citation2021) purposefully only analysed positive experiences however, clearly producing biased findings. For many carers, engaging with the person with dementia was their only point of face-to-face social contact during the pandemic, generating feelings of loneliness (Hanna et al., Citation2021; Tam et al., Citation2021). This can particularly be the case for older spousal carers living with their relative with dementia, which can add to potential feelings of burnout and lack of respite from their caring duties. Considering the wider restrictions impacting on everyone, across the globe, it is unclear to what extent heightened levels of caring duties and lack of respite from caring contributed to poorer mental well-being, and to what extent generally living through an unknown and novel pandemic contributed. Longitudinal survey data has evidenced reductions in mental health across the general UK population in the early stages of the pandemic compared to prior (Pierce et al., Citation2020). On top of these impacts, evidence from this review illustrates the significant impact that informal caring duty and formal care access changes have had on unpaid carers (Dassel et al., Citation2021; Rajagopalan et al., Citation2022). Whilst more research is needed on the long-lasting mental health needs of unpaid dementia carers, and unpaid carers in general, findings from this review clearly highlight a need for improved access to mental health support, something that should be in place anyways considering the gravity of experiencing the diagnosis of a loved one and living through the diagnosis providing care and support.

One way for carers to try and stay connected with people other than the person with dementia was via digital technology. Whilst care services were not adapted to provide digital support at the beginning of the pandemic, some services very slowly adapted to providing care remotely, particularly peer support groups (i.e. Giebel et al., Citation2021c). Connecting with peers remotely to bypass the growing sense of social isolation and loneliness was also a solution for carers as reported by Tam et al. (Citation2021), although less than a fifth of carers felt that digital social connectivity was as beneficial as face-to-face contact and a number of barriers have been identified. Recent research has highlighted how carer age also matters when connecting digitally with dementia services during the pandemic, as younger carers (adult children) appeared to be better equipped, highlighting the digital divide (Arighi et al., Citation2021). Whilst more research is required into the digital dementia care experiences since the pandemic, emerging research illustrates how digital connectivity can provide some benefits when lacking face-to-face engagement. Even when connecting remotely with peers and services, the unpaid carer still has to be with the person with dementia though to access care, and cannot engage in their own activities. Therefore, care should be provided face-to-face again in safe formats as soon as possible, whilst some long-term benefits may be drawn from digitally adapted services for people living in more rural communities – a frequent previous barrier to engaging with support services (Innes et al., Citation2006).

The mix of lack of support and access to care, poor mental well-being, and increased carer burden are all likely to contribute to people with dementia entering a care home earlier, at least compared to non-pandemic circumstances. In pre-pandemic times, when unpaid carers were unable to care for their relative at home any longer, due to increased carer burden or too many care needs, people with dementia would normally enter a care home (Sutcliffe et al., 2017). In the best case scenario, this would have been planned in advance to provide care home entry at the right time. Since the pandemic, people with dementia also appear to have deteriorated faster and received less care support in the community, as Part I of this interlinked systematic review has shown (Giebel et al., submitted) has shown, confirming earlier reported results (Suarez-Gonzalez et al., Citation2021). Thus, it is likely that people with dementia have entered a care home faster since the pandemic, based on the negative impacts of COVID-19 on community-residing people with dementia and carers, as evidenced in this review. However, care homes have faced different levels of restrictions, which are ongoing, often not allowing unpaid carers to visit their relative (Backhaus et al., Citation2021) and making it difficult to plan in advance. This may lead to further increases in carer burden, as well as guilt, if carers are unable to care for their relative at home but delay care home entry due to those restrictions, whilst others may see no alternative but to have their relative admitted. Very early indications about faster care home entry, and the ensuing guilt experienced by unpaid carers, has been reported in one of the included studies here in summer 2020 in the UK for example (Giebel et al., Citation2021c). However, more long-term research is required after two years of pandemic restrictions to explore the impact on carer well-being and burden on care home entry during the pandemic.

In order to avoid unnecessary care home entry, but also to tackle the raised issues of lack of carer support and increased mental health problems, findings from this 2-part systematic review indicate a need for clear policy guidance to support unpaid carer better in the long-term. This is particularly the case for the ongoing pandemic, with different levels of restrictions in place in different countries. To avoid such detrimental impacts in any future pandemics, and to tackle persistent and systemic issues in social and mental health care provision for unpaid dementia carers, policy guidance needs to be introduced now.

Limitations

This mixed-method systematic review benefitted from searching numerous databases and producing a timely report of the impact of the pandemic on unpaid carers. However, due to the nature of the research and a continuously growing evidence base, it was not feasible to update the searches. This review already included a large number of studies after exclusion criteria were applied, and thus provides a timely and time-period specific synthesis of the evidence base to inform future research and policy making.

In terms of the research included, some studies were limited in providing retrospective accounts of for example mental health prior to the pandemic and changes noticed, as opposed to pre and post assessments using validated measures. However, mental health or burden is in general assessed largely by asking the person affected. The recall bias needs to be taken into account. However, a state-of the art pre-pandemic assessment was not presented for obvious reasons. Therefore, these data provide suitable evidence. Whilst grey literature was not included, there was no scope to include this and no further benefit to it considering the large amount of included primary and peer-reviewed research in this systematic review already. One wider limitation, but also advantage, of this review is that it considered studies from 18 countries. Restrictions differed between countries and even between regions making it difficult to relate a type or severity of measure to an outcome. However, even considering this heterogeneity the studies identified a comparable impact on carers. All reported negative impacts on the support system, well-being and mental health of unpaid carers (except one study which purposefully explored positive experiences from interviews and was therefore biased – Tulloch et al., Citation2021). However, there were limitations in findings from lower- and middle-income countries (LMICs), with only two studies reporting on India and Brazil (Azevedo et al., 2021; Rajagopalan et al., Citation2022). Impacts are likely to differ across high-impact countries and LMICs, indicating a need for more research into the impacts in LMICs.

Conclusions

Unpaid carers, similar to people with dementia, have been harmfully affected during the pandemic from access to adequate care and support to increased levels of carer burden and poor mental health. Findings in this review from across the globe thus illustrate how unpaid carers urgently need to be supported better in not only their caring role, but also as an individual, taking into account their own personal needs. Whilst restrictions may ease in certain countries and many, albeit not all, societies benefit from protection offered from vaccinations, the early impacts of the pandemic are likely going to have long-lasting effects on the mental and physical health of unpaid carers. This is particularly important as many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have reduced vaccination availability, rendering the virus more harmful for longer and thus creating more long-lasting restrictions than in some high-income countries, such as the UK. Future research ought to explore the long-lasting impacts of COVID-19 on this group, especially in light of care recipients entering care homes.

Author’s contributions

CG led the systematic review, drafted the protocol and manuscript, and scored citations for Stage 1 and 2. ASG generated the search strategy. RT, KL, CT, KHL, EW scored citations for inclusion in the review. EW extracted all data from included studies and quality rated all studies. RT, CT, ASG, KHL, KL, EW, JC, HT discussed the findings jointly, placed them into context, and read through drafts of the manuscripts before approving the final draft.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of Adel Afin in running and documenting the literature search.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexopoulos, P., Soldatos, R., Kontogianni, E., Frouda, M., loanna Aligianni, S., Skondra, M., Passa, M., Konstantopoulou, G., Stamouli, E., Katirtzoglou, E., Politis, A., Economou, P., Alexaki, M., Siarkos, K., & Politis, A. (2021). COVID-19 crisis effects on caregiver distress in neurocognitive disorder. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 79(1), 459–466. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200991

- Altieri, M., & Santangelo, G. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown on caregivers of people with dementia. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(1), 27–34.

- Alzheimer’s Disease International (2018). The state-of-the-art dementia research: New Frontiers. Alzheimer’s Disease International.

- Arighi, A., Fumagalli, G. G., Carandini, T., Pietroboni, A. M., De Riz, M. A., Galimberti, D., & Scarpini, E. (2021). Facing the digital divide into a dementia clinic during COVID-19 pandemic: Caregiver age matters. Neurological Sciences, 42(4), 1247–1251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10072-020-05009-w

- Azevedo, L. V. D. S., Calandri, I. L., Slachevsky, A., Graviotto, H. G., Vieira, M. C. S., Andrade, C. B. d., Rossetti, A. P., Generoso, A. B., Carmona, K. C., Pinto, L. A. C., Sorbara, M., Pinto, A., Guajardo, T., Olavarria, L., Thumala, D., Crivelli, L., Vivas, L., Allegri, R. F., Barbosa, M. T., … Caramelli, P. (2021). Impact of social isolation on people with dementia and their family caregivers. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 81(2), 607–617. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-201580

- Backhaus, R., Verbeek, H., de Boer, B., et al. (2021). From wave to wave: a Dutch national study on the long-term impact of COVID-19 on well-being and family visitation in nursing homes. BMC Geriatrics 21, 588. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02530-1

- Bacsu, J.-D R., O’Connell, M. E., Webster, C., Poole, L., Wighton, M. B., & Sivananthan, S. (2021). A scoping review of COVID-19 experiences of people living with dementia. Canadian Journal of Public Health = Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique, 112(3), 400–411. https://doi.org/10.17269/s41997-021-00500-z

- Bianchetti, A., Rozzini, R., & Guerini, F. (2020). Clinical presentation of COVID-19 in dementia patients. Journal of Nutrition, Health & Ageing, 24, 560–562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1389-1

- Black, B. S., Johnston, D., Rabins, P. V., et al. (2013). Unmet needs of community-residing persons with dementia and their informal caregivers: Findings from the maximizing independence at home study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 61(12), 2087–2095. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12549

- Borelli, W. V., Augustin, M. C., de Oliveira, P. B. F., Reggiani, L. C., Bandeira-de-Mello, R. G., Schumacher-Schuh, A. F., Chaves, M. L. F., & Castilhos, R. M. (2021). Neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia associated with increased psychological distress in caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 80(4), 1705–1712. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-201513

- Borg, C., Rouch, I., Pongan, E., Getenet, J. C., Bachelet, R., Herrmann, M., Bohec, A.-L., Laurent, B., Rey, R., & Dorey, J.-M. (2021). Mental health of people with dementia during COVID-19 pandemic: What have we learned from the first wave? Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 82(4), 1531–1541. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-210079

- Borges-Machado, F., Barros, D., Ribeiro, O., & Carvalho, J. (2020). The effects of COVID-19 home confinement in dementia care: Physical and cognitive decline, severe neuropsychiatric symptoms and increased caregiving burden. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 35, 1533317520976720.

- Boutoleau-Bretonnière, C., Pouclet-Courtemanche, H., Gillet, A., Bernard, A., Deruet, A.-L., Gouraud, I., Lamy, E., Mazoué, A., Rocher, L., Bretonnière, C., & El Haj, M. (2020). Impact of confinement on the burden of caregivers of patients with the behavioral variant of frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease during the COVID-19 crisis in France. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra, 10(3), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1159/000511416

- Carcavilla, N., Pozo, A. S., Gonzalez, B., Moral-Cuesta, D., Roldan, J. J., Erice, V., & Remirez, A. G. (2021). Needs of dementia family caregivers in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 80(2), 533–537.

- Carpinelli Mazzi, M., Iavarone, A., Musella, C., De Luca, M., de Vita, D., Branciforte, S., Coppola, A., Scarpa, R., Raimondo, S., Sorrentino, S., Lualdi, F., & Postiglione, A. (2020). Time of isolation, education and gender influence the psychological outcome during COVID-19 lockdown in caregivers of patients with dementia. European Geriatric Medicine, 11(6), 1095–1098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-020-00413-z

- Clemmensen, T. H., Lauridsen, H. H., Andersen-Ranberg, K., & Kristensen, H. K. (2021). ‘I know his needs better than my own’ – carers’ support needs when caring for a person with dementia. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 35(2), 586–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12875

- Cohen, G., Russo, M. J., Campos, J. A., & Allegri, R. F. (2020a). COVID-19 Epidemic in Argentina: Worsening of behavioral symptoms in elderly subjects with dementia living in the community. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 866. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00866

- Cohen, G., Russo, M. J., Campos, J. A., & Allegri, R. F. (2020b). Living with dementia: Increased level of caregiver stress in times of COVID-19. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(11), 1377–1381. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220001593

- Dassel, K. B., Towsley, G. L., Utz, R. L., Ellington, L., Terrill, A., Scammon, D., Bristol, A. A., Thompson, A., & Mickens, M. (2021). A limited opportunity: COVID-19 and promotion of advance care planning. Palliative Medicine Reports, 2(1), 194–198. https://doi.org/10.1089/pmr.2021.0013

- Giebel, C., Hanna, K., Cannon, J., Eley, R., Tetlow, H., Gaughan, A., Komuravelli, A., Shenton, J., Rogers, C., Butchard, S., Callaghan, S., Limbert, S., Rajagopal, M., Ward, K., Shaw, L., Whittington, R., Hughes, M., & Gabbay, M. (2020). Decision-making for receiving paid home care for dementia in the time of COVID-19: A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 333. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01719-0

- Giebel, C., Hanna, K., Rajagopal, M., Komuravelli, A., Cannon, J., Shenton, J., Eley, R., Gaughan, A., Callaghan, S., Tetlow, H., Limbert, S., Whittington, R., Rogers, C., Ward, K., Shaw, L., Butchard, S., & Gabbay, M. (2021a). The potential dangers of not understanding COVID-19 public health restrictions in dementia: “It’s a groundhog day – every single day she does not understand why she can’t go out for a walk”. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 762. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10815-8

- Giebel, C., Pulford, D., Cooper, C., Lord, K., Shenton, J., Cannon, J., Shaw, L., Tetlow, H., Limbert, S., Callaghan, S., Whittington, R., Rogers, C., Komuravelli, A., Rajagopal, M., Eley, R., Downs, M., Reilly, S., Ward, K., Gaughan, A., … Gabbay, M. (2021b). COVID-19-related social support service closures and mental well-being in older adults and those affected by dementia: A UK longitudinal survey. BMJ Open, 11(1), e045889. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045889

- Giebel, C., Hanna, K., Callaghan, S., Cannon, J., Butchard, S., Shenton, J., Komuravelli, A., Limbert, S., Tetlow, H., Rogers, C., Eley, R., Rajagopal, M., Ward, K., & Gabbay, M. (2021c). Navigating the new normal: Accessing community and institutionalised care for dementia during COVID-19. Aging Ment Health, 26, 905–910. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2021.1914545

- Giebel, C., Cannon, J., Hanna, K., Butchard, S., Eley, R., Gaughan, A., Komuravelli, A., Shenton, J., Callaghan, S., Tetlow, H., Limbert, S., Whittington, R., Rogers, C., Rajagopal, M., Ward, K., Shaw, L., Corcoran, R., Bennett, K., & Gabbay, M. (2021d). Impact of COVID-19 related social support service closures on people with dementia and unpaid carers: A qualitative study. Aging & Mental Health, 25(7), 1281–1288. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1822292

- Giebel, C., Sutcliffe, C., Darlington-Pollock, F., Green, M. A., Akpan, A., Dickinson, J., Watson, J., & Gabbay, M. (2021e). Health inequities in the care pathways for people living with young- and late-onset dementia: From pre-COVID-19 to early pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 686.

- Giebel, C., Lord, K., Cooper, C., Shenton, J., Cannon, J., Pulford, D., Shaw, L., Gaughan, A., Tetlow, H., Butchard, S., Limbert, S., Callaghan, S., Whittington, R., Rogers, C., Komuravelli, A., Rajagopal, M., Eley, R., Watkins, C., Downs, M., … Gabbay, M. (2021f). A UK survey of COVID-19 related social support closures and their effects on older people, people with dementia, and carers. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 36(3), 393–402. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5434

- Hanna, K., Giebel, C., Butchard, S., Tetlow, H., Ward, K., Shenton, J., Cannon, J., Komuravelli, A., Gaughan, A., Eley, R., Rogers, C., Rajagopal, M., Limbert, S., Callaghan, S., Whittington, R., Shaw, L., Donnellan, W., & Gabbay, M. (2022). Resilience and supporting people living with dementia during the time of COVID-19; A qualitative study. Dementia (London), 21(1), 250–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012211036601

- Hanna, K., Giebel, C., Tetlow, H., Ward, K., Shenton, J., Cannon, J., Komuravelli, A., Gaughan, A., Eley, R., Rogers, C., Rajagopal, M., Limbert, S., Callaghan, S., Whittington, R., Butchard, S., Shaw, L., & Gabbay, M. (2021). Emotional and mental wellbeing following COVID-19 public health measures on people living with dementia and carers. Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry and Neurology, 35(3), 344–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891988721996816

- Hariyanto, T. I., Putri, C., Arisa, J., Situmeang, R. F. V., & Kurniawan, A. (2021). Dementia and outcomes from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 93, 104299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2020.104299

- Helvaci Yilmaz, N., Polat, B., Ermis, A., & Hanoglu, L. (2021). Clinical deterioration of Alzheimer’s disease patients during the Covid-19 pandemic and caregiver burden. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Medicine, 38(3), 255–259. https://doi.org/10.52142/omujecm.38.3.9

- Hughes, M. C., Liu, Y., & Baumbach, A. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on the health and well-being of informal caregivers of people with dementia: A rapid systematic review. Gerontology & Geriatric Medicine, 7, 23337214211020164. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F64

- Hwang, Y., Connell, L. M., Rajpara, A. R., & Hodgson, N. A. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on dementia caregivers and factors associated with their anxiety symptoms. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 36, 15333175211008768.

- Innes, A., Cox, S., Smith, A., & Mason, A. (2006). Service provision for people with dementia in rural Scotland: Difficulties and innovations. Dementia, 5(2), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301206062253

- Janssen, N., Handels, R. L., Koehler, S., et al. (2019). Profiles of met and unmet needs in people with dementia according to caregivers’ perspective: Results from a European multicenter study. JAMDA 21(11), 1609–1616.

- Kmet, L. M., Lee, R. C., & Cook, L. S. (2004). Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields. Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. AHFMR.

- Kostyál, L., Széman, Z., Almási, V., Fabbietti, P., Quattrini, S., Socci, M., Lamura, G., & Gagliardi, C. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on family carers of older people living with dementia in Italy and Hungary. Sustainability, 13(13), 7107. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13137107

- Losada, A., Vara-Garcia, C., Romero-Moreno, R., Barrera-Caballero, S., Pedroso-Chaparro, M. D. S., Jimenez-Gonzalo, L., Fernandes-Pires, J., Cabrera, I., Gallego-Alberto, L., Huertas-Domingo, C., Mérida-Herrera, L., Olazarán-Rodríguez, J., & Marquez-Gonzalez, M. (2021). Caring for relatives with dementia in times of COVID-19: Impact on caregivers and care-recipients. Clinical Gerontologist, 45, 71–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2021.1928356

- Ng, K. P., Chiew, H. J., Hameed, S., Ting, S. K. S., Ng, A., Soo, S. A., Wong, B. Y. X., Lim, L., Yong, A. C. W., Mok, V. C. T., Rosa-Neto, P., Dominguez, J., Kim, S. Y., Hsiung, G. Y. R., Ikeda, M., Miller, B. L., Gauthier, S., & Kandiah, N. (2020). Frontotemporal dementia and COVID-19: Hypothesis generation and roadmap for future research. Alzheimers Dement (N Y), 6(1), e12085.

- Orellana, K., Manthorpe, J., & Tinker, A. (2020). Day centres for older people – attendance characteristics, access routes and outcomes of regular attendance: Findings of exploratory mixed methods case study research. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 158. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01529-4

- Panerai, S., Prestianni, G., Musso, S., Muratore, S., Tasca, D., Musso, S., Catania, V., Ruggeri, F., Raggi, A., Gelardi, D., Ferri, R. (2016). The impact of COVID-19 confinement on the neurobehavioral manifestations of people with Major Neurocognitive Disorder and on the level of burden of their caregivers. Life Span and Disability, 23(2), 303–320. http://www.lifespanjournal.it/client/abstract/ENG371_6.%20Panerai.pdf

- Panerai, S., Tasca, D., Musso, S., Catania, V., Ruggeri, F., Raggi, A., & Ferri, R. (2016). The impact of COVID-19 confinement on the neurobehavioral manifestations of people with major neurocognitive disorder and on the level of burden of their carers. Life Span and Disability (2), 303–320.

- Parveen, S., Peltier, C., & Oyebode, J. R. (2017). Perceptions of dementia and use of services in minority ethnic communities: A scoping exercise. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(2), 734–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12363

- Pierce, M., Hope, H., Ford, T., Hatch, S., Hotopf, M., John, A., Kontopantelis, E., Webb, R., Wessely, S., McManus, S., & Abel, K. M. (2020). Mental health before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: A longitudinal probability sample survey of the UK population. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 7(10), 883–892. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30308-4

- Pongan, E., Dorey, J.-M., Borg, C., Getenet, J. C., Bachelet, R., Lourioux, C., Laurent, B., Rey, R., & Rouch, I. (2021). COVID-19: Association between increase of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia during lockdown and caregivers’ poor mental health. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 80(4), 1713–1721. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-201396

- Rainero, I., Bruni, A. C., Marra, C., Cagnin, A., Bonanni, L., Cupidi, C., Laganà, V., Rubino, E., Vacca, A., Di Lorenzo, R., Provero, P., Isella, V., Vanacore, N., Agosta, F., Appollonio, I., Caffarra, P., Bussè, C., Sambati, R., Quaranta, D., Ferrarese, C., & Group, S. I. C.-S. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 quarantine on patients with dementia and family caregivers: A nation-wide survey. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 12, 625781. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2020.625781

- Rainero, I., Bruni, A. C., Marra, C., et al. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 quarantine on patients with dementia and family carers: A nation-wide survey. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 12, 625781.

- Rajagopalan, J., Arshad, F., Hoskeri, R. M., Nair, V. S., Hurzuk, S., Annam, H., Varghese, F., Br, R., Dhiren, S. R., Ganeshbhai, P. V., Kammammettu, C., Komaravolu, S., Thomas, P. T., Comas-Herrera, A., & Alladi, S. (2022). Experiences of people with dementia and their caregivers during the COVID-19 pandemic in India: A mixed-methods study. Dementia (London), 21(1), 214–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012211035371

- Rising, K. L., Salcedo, V. J., Amadio, G., Casten, R., Chang, A., Gentsch, A., O’Hayer, C. V., Sarpoulaki, N., Worster, B., & Gerolamo, A. M. (2022). Living through the pandemic: The voices of persons with dementia and their caregivers. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(1), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/07334648211036399

- Rusowicz, J., Pezdek, K., & Szczepańska-Gieracha, J. (2021). Needs of Alzheimer’s charges’ caregivers in Poland in the covid-19 pandemic-an observational study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(9), 4493. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18094493

- Savla, J., Roberto, K. A., Blieszner, R., McCann, B. R., Hoyt, E., & Knight, A. L. (2021). Dementia caregiving during the "stay-at-home" phase of COVID-19 pandemic. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(4), e241–e245. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa129

- Sriram, V., Jenkinson, C., & Peters, M. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 restrictions on carers of persons with dementia in the UK: A qualitative study. Age and Ageing, 50(6), 1876–1885. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab156

- Suarez-Gonzalez, A., Rajagopalan, J., Livingston, G., & Alladi, S. (2021). The effect of COVID-19 isolation measures on the cognition and mental health of people living with dementia: A rapid systematic review of one year of quantitative evidence. Eclinical Medicine, 39, 101047. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.101047

- Sutcliffe C, Giebel C, Bleijlevens M, et al. (2017). Caring for a person with dementia on the margins of long-term care: a perspective on burden from 8 European countries. JAMDA 18(11), 967–973. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.06.004

- Talbot, C. V., & Briggs, P. (2021). ‘Getting back to normality seems as big of a step as going into lockdown’: the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with early to middle stage dementia. Age and Ageing, 50(3), 657–663. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab012

- Tam, M. T., Dosso, J. A., & Robillard, J. M. (2021). The impact of a global pandemic on people living with dementia and their care partners: Analysis of 417 lived experience reports. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 80(2), 865–875.

- Tretteteig, S., Vatne, S., & Rokstad, A. M. M. (2017). The influence of day care centres designed for people with dementia on family caregivers – A qualitative study. BMC Geriatrics, 17(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0403-2

- Tsapanou, A., Zoi, P., Kalligerou, F., Blekou, P., & Sakka, P. (2021). The effect of prolonged lockdown due to COVID-19 on Greek demented patients of different stages and on their caregivers. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 83(2), 907–913. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-210702

- Tuijt, R., Frost, R., Wilcock, J., Robinson, L., Manthorpe, J., Rait, G., & Walters, K. (2021a). Life under lockdown and social restrictions – the experiences of people living with dementia and their carers during the COVID-19 pandemic in England. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 301. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02257-z

- Tuijt, R., Rait, G., Frost, R., Wilcock, J., Manthorpe, J., & Walters, K. (2021b). Remote primary care consultations for people living with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences of people living with dementia and their carers. The British Journal of General Practice, 71(709), e574–e582. https://doi.org/10.3399/BJGP.2020.1094

- Tuijt, R., Frost, R., Wilcock, J., Robinson, L., Manthorpe, J., Rait, G., & Walters, K. (2021). Life under lockdown and social restrictions - The experiences of people living with dementia and their during the COVID-19 pandemic in England. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 301.

- Tuijt, R., Rait, G., Frost, R., Wilcock, J., Manthorpe, J., & Walters, K. (2021). Remote primary care consultations for people living with dementia during the COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences of people living with dementia and their. British Journal of General Practice, 71(709), e574–e582.

- Tulloch, K., McCaul, T., & Scott, T. L. (2021). Positive aspects of dementia caregiving during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical Gerontologist, 45(1), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2021.1929630

- Vaitheswaran, S., Lakshminarayanan, M., Ramanujam, V., Sargunan, S., & Venkatesan, S. (2020). Experiences and needs of caregivers of persons with dementia in India during the COVID-19 pandemic – A qualitative study. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(11), 1185–1194.

- Werner, P., Tur-Sinai, A., & AboJabel, H. (2021). Examining dementia family caregivers’ forgone care for general practitioners and medical specialists during a COVID-19 lockdown. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3688.

- West, E., Nair, P., Barrado-Martin, Y., Walters, K. R., Kupeli, N., Sampson, E. L., & Davies, N. (2021). Exploration of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on people with dementia and carers from black and minority ethnic groups. BMJ Open, 11(5), e050066. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050066

- World Health Organisation (WHO). (2021). Dementia – Factsheet. Geneva. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia.

- Zucca, M., Isella, V., Lorenzo, R. D., Marra, C., Cagnin, A., Cupidi, C., Bonanni, L., Laganà, V., Rubino, E., Vanacore, N., Agosta, F., Caffarra, P., Sambati, R., Quaranta, D., Guglielmi, V., Appollonio, I. M., Logroscino, G., Filippi, M., Tedeschi, G., Bruni, A. C.,& SINdem COVID-19 Study Group. (2021). Being the family caregiver of a patient with dementia during the coronavirus disease 2019 lockdown. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 13, 653533. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.653533

- Zuin, M., Guasti, P., Roncon, L., Cervellati, C., & Zuliani, G. (2020). Dementia and the risk of death in elderly patients with COVID-19 infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 36(5), 697–703. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5468

- Zwingmann I, Michalowsky B, Esser A, et al. (2019). Identifying unmet needs of family dementia caregivers: Results of the baseline assessment of a cluster-randomized controlled intervention trial. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, 67(2), 527–539. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-180244