Abstract

Objectives

With sociodemographic changes, men are increasingly taking responsibility for spousal caregiving. Previous studies have described gender differences in the psychological outcomes of caregiving; however, few have focused exclusively on husband caregivers. This study investigates the influence of starting spousal caregiving on the psychological well-being of older husbands in rural areas and examines whether living arrangements can moderate this relationship.

Methods

A total of 1,167 baseline non-caregiver husbands aged 60 and above in rural areas were taken from the 2011–2015 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). The generalized estimating equation (GEE) was employed to examine the effects of spousal caregiving transitions and living arrangement changes on depressive symptoms over four years.

Results

Compared with rural husbands who remained non-caregivers, those transitioning into activities of daily living (ADL) caregiving reported higher depressive symptoms at follow-up (B = 1.67, p < 0.05). Moreover, the increase in depressive symptoms when transitioning into ADL caregiving was significantly lower among participants who changed from living with spouse alone to living with spouse and other family members together (B = − 5.37, p < 0.05).

Conclusion

There was an association between transitioning into ADL caregiving and an elevated level of depression over four years among older husbands, which could be alleviated by living with family members. Co-residence with family members could serve as a natural support resource, buffering adverse mental health outcomes when older husbands start a demanding caregiving role.

Introduction

The rapid trend of population aging has posed great challenges for elder care around the world. With increased age, people become vulnerable to health problems and functional decline (Clarke et al., Citation2021; Verbrugge et al., Citation2017), which creates challenges for societies to satisfy the care needs of the older population. Once older individuals are at the onset of functional impairments, their spouses have the highest probability of taking the primary caregiver role (Gruijters, Citation2017; Li & Dai, Citation2019). Moreover, low fertility and high migration rates have resulted in smaller families, leaving more older people to care for their spouses (Bai et al., Citation2018).

Although women typically assume the caregiver role, there has been a rising proportion of male caregivers in recent years (Mott et al., Citation2019; Sharma et al., Citation2016). In China, a typically patriarchal society, family caregiving remains an activity predominantly performed by women; however, husbands are increasingly involved in elder care due to the aging population, increased female employment rate, and transformation of family structures. More importantly, rural-to-urban migration in the past decades has resulted in a large number of older people left behind in rural areas (Yuan, Citation2019), leaving older men to be primary caregivers once their wives develop difficulties in daily life (Song, Citation2017). According to population census data, empty-nested families accounted for nearly 30.77% of households in rural China, consisting of approximately 16 million elders (Yuan, Citation2019).

Husband caregivers may encounter gender role conflict between what they perceive as their traditional “masculine” role and their new “feminine” caregiving role (O’Neil, Citation1981). Given that the traditional intra-household labor division in Chinese culture, especially in rural areas, involves men acting as the breadwinners and women performing the housework obligations, husbands may face great challenges when transitioning into roles as spousal caregivers. Therefore, it is meaningful to examine whether assuming the spousal caregiver role could influence husband caregivers’ psychological well-being in rural China.

Spousal caregiving and gender differences

Among a large number of studies on the influence of spousal caregiving on caregivers’ mental health, many of them confirmed the adverse outcomes by comparing caregiving and non-caregiving spouses cross-sectionally (Mausbach et al., Citation2013; Wagner & Brandt, Citation2018). Other studies considered spousal caregiving as a dynamic process and revealed that newly assuming a spousal caregiver role may cause mental health deterioration (Choi & Marks, Citation2006; Dunkle et al., Citation2014; Kaufman et al., Citation2019; Zhao et al., Citation2021). In addition, the impact of caregiving may vary with caregiving tasks, as caregivers performing activities of daily living (ADL) caregiving reported more mental or physical outcomes than those providing instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) caregiving or the non-caregivers (Liu & Lou, Citation2019; Lyons et al., Citation2015; Zhao et al., Citation2021).

Previous studies have also examined gender differences in the mental health outcomes of caregiving. However, their findings were inconsistent. The majority of them revealed that female caregivers reported higher levels of burden (Conde-Sala et al., Citation2010; Swinkels et al., Citation2019) or depression (Gibbons et al., Citation2014; Ketcher et al., Citation2020; Sugiura et al., Citation2009). For instance, a study on spousal caregivers in Canada found that wife caregivers reported a higher level of burden (Gibbons et al., Citation2014), and a study in Japan showed that wife caregivers had a higher level of depression than husband caregivers (Sugiura et al., Citation2009). However, some studies did not show significant gender differences regarding the mental health outcomes of caregiving (Kaufman et al., Citation2019; Zarit et al., Citation1986), and one study in Germany found a larger detrimental effect on mental health for husband caregivers (Hajek & König, Citation2016). The inconsistent findings from different studies might be attributed to differences in study design, sample composition, and situation of care recipients. A meta-analysis of 229 studies found higher levels of burden and depression in female caregivers; however, the gender differences were of much smaller magnitude than expected (Pinquart & Sörensen, Citation2006). Caregiving might also be a stressful experience for male caregivers.

Male caregivers and gender role conflict

Although there is an increasing proportion of males assuming the caregiving role, in recent years, male caregivers have been overlooked in research on informal caregivers. Among the limited studies focusing on husband caregivers, most of them investigated caregivers’ perception of strain in caregiving (Baker et al., Citation2010; Ducharme et al., Citation2006; CitationFigueiredo et al., 2016) or the influence of caregiving on psychological well-being (Ducharme et al., Citation2007; Kramer, Citation2000; Lévesque et al., Citation2008). They concluded that several subjective stressors were predictive of psychological distress, including role overload, role captivity, and relational deprivation, whereas self-efficacy had a mediating role.

According to traditional gender role norms, doing housework, raising children, and caring for sick family members are female undertakings, while males are usually socialized to work outside (Graham, Citation1983). Becoming a caregiver would be an unfamiliar and even anormal role for males. Male caregivers might feel more uncomfortable with hands-on personal care than female caregivers, as many of them have not been involved in childrearing tasks such as giving baths and changing diapers. Meanwhile, there is gender role conflict between male caregivers’ internalized “masculine” role and the “feminine” caregiving role, would make them reluctant to disclose feelings of distress (Baker et al., Citation2010; Sanders, Citation2007) and ambivalent to seek outside help (Wisch et al., Citation1995). A recent study in Hong Kong revealed that gender role conflict was related to a high caregiving burden among 204 male caregivers (Bai et al., Citation2018). Traditional gender role norms are deep-rooted in rural China, a typically patriarchal society. It is of interest to investigate the male caregivers there. Given the limited knowledge about husband caregivers, there is a dearth of research on whether caregiving could influence rural male caregivers’ well-being, and what could buffer possible adverse outcomes for the group who are reluctant to seek help.

Living arrangements as supporting resources for caregivers

It has been regarded that psychosocial resources can exert a protective role against the adverse outcomes of caregiving (Pearlin & Bierman, Citation2013). Existing evidence also supported that eldercare services such as day care centers could reduce caregivers’ burden (Tretteteig et al., Citation2016). However, there is huge urban-rural inequality in social resources for eldercare (Wolff & Kasper, Citation2006; Zhao et al., Citation2022). According to the Statistical Bulletin of Social Service Development released by the Ministry of Civil Affairs of China (Citation2018), the coverage rate of community service centers in urban areas was much higher than that in rural areas (78.6% vs. 15.3%) by the end of 2017. We have conducted a preliminary analysis on the Community Survey of the 2011 China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey (CHARLS). It showed that among all 152 urban communities, 38 (25.0%) had a community-based eldercare center; in comparison, among 308 rural villages, only 8 (2.6%) had a family-based eldercare center. As caregivers in rural areas have less accessibility to eldercare services (such as respite care or assistive services), support from family is essentially expected (Ng et al., Citation2002). In this sense, when spousal caregivers in rural areas encounter challenges, their family members who can provide adequate emotional and practical support become the most available resource.

Traditionally, the multigenerational household has been the most desirable living arrangement in Chinese societies (Lam et al., Citation1998). However, because of rapid industrialization and urbanization in recent decades in China, traditional extended households have been decreasing, and more older adults are living with spouse only (Gruijters, Citation2017). Even in rural areas, rural-to-urban migration of the young workforce leads to a large number of “empty-nest” older people. The role of living arrangements in older adults’ mental health has attracted increasing research interest and the findings vary across societies, cultures, and households (Oh et al., Citation2015). For instance, a study in Shanghai city of China found that living with children was associated with better mental health for elder people (Ye & Chen, Citation2014). However, Ren and Treiman (Citation2015) used data from the China Family Panel Study and found that co-residence with grown children was associated with decreased psychological well-being compared with living independently with spouse. This might be because individual modernization increases older adults’ independence (Guo & Zhang, Citation2021) and living in multigenerational households might produce conflicts among family members (Oh et al., Citation2015). In terms of research focused on older people in rural areas, most revealed that living in single-generation households had detrimental effects on their mental health (Silverstein et al., Citation2006; Yue & Ma, Citation2017), which may be further compounded by living in impoverished communities (Song, Citation2017). If taking older adults’ functional status into account, previous research found that living with adult children could contribute to psychological well-being for older adults with functional disabilities (Xu, Citation2018). However, it is still unknown whether living arrangements could influence the mental health of spousal caregivers.

Objectives

Although previous studies have examined gender differences in spousal caregiving, most of them were cross-sectional, offering comparisons of psychological well-being between husbands and wives. Few studies have exclusively focused on husband caregivers. It is unknown whether transitioning to a caregiving role might influence older husbands’ well-being in a typical patriarchal society such as rural China. Given the underdeveloped social services in rural areas, living with family members may be a support resource for caregivers. Based on the existing literature, the following hypotheses were addressed:

Hypothesis 1: Compared with participants who had not provided spousal caregiving, participants who transitioned to IADL or ADL caregiving roles will report a higher degree of depressive symptoms at follow-up.

Hypothesis 2: Compared with participants who remained living with spouse only, those who changed from living with spouse only to living with family members together when transitioning into spousal caregiving will have a lower level of depressive symptoms.

Methods

Data and participants

We obtained data from the first three waves (2011, 2013, and 2015) of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Survey (CHARLS), a national, longitudinal survey of community-dwelling individuals aged 45 and over (and their spouses) in China. CHARLS used face-to-face and computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) administered by trained interviewers to collect information. Because of strict adherence to stratified probability proportional to size (PPS) random sampling principles and rigorous quality control in all phases of the survey, the weighted population characteristics of CHARLS closely matched the 2010 census, indicating that the data could be representative of middle-aged and older adults in China (Zhao et al., Citation2014). The 2011 baseline CHARLS sample consisted of 17,708 individuals, of which a total of 13,557 individuals completed both the 2013 and 2015 follow-up surveys. For this study, 1,167 individuals were included according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) aged 60 years or above in 2011; (2) married males living in rural areas; (3) took part in all three waves of CHARLS; (4) provided data on household living arrangement; (5) both the individual and their spouse provided information on questions about whether they had any difficulty with ADL or IADL and whether they had received any ADL/IADL help from their spouse (the information was used for coding whether the participants were providing spousal care); and (6) did not provide any spousal care in 2011 (as the potential spousal caregivers after 2011).

Measurements

Depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CESD) (Andresen et al., Citation1994). The scores range from 0 to 30, with a higher score indicating a higher level of depressive symptoms. The Cronbach’s α was 0.767 and 0.764 in 2011 and 2015, respectively.

Transitions in spousal caregiving intensity

The CHARLS surveys asked participants who had difficulties in IADL (including doing housework, preparing meals, shopping, making telephone calls, managing money, and taking medication) or ADL (including dressing, bathing, eating, getting into/out of bed, using the toilet, and controlling urination and defecation) to report the individuals who helped them in these difficulties. If a participant answered his or her spouse was the primary caregiver, then his or her spouse was identified as the spousal caregiver. First, referring to previous research (Burton et al., Citation2003; Liu & Lou, Citation2019; Zhao et al., Citation2021), the caregiving intensity in each wave was categorized into three levels: (1) no-caregiving (did not provide any ADL/IADL assistance to the spouse); (2) IADL caregiving (provided at least one form of IADL assistance but no ADL assistance to the spouse); and (3) ADL caregiving (provided at least one form of ADL assistance to the spouse). As providing ADL help has been regarded as more demanding than providing IADL help (Feld et al., Citation2010; Johnson & Wolinsky, Citation1993) and existing studies showed that individuals who newly assumed ADL caregiving role reported worse physical or psychological health than those who started IADL caregiving (Burton et al., Citation2003; Liu & Lou, Citation2019; Wong & Hsieh, Citation2019), we adopted this approach that distinguished ADL caregiving from IADL caregiving. Second, we combined the information about caregiving intensity at the three waves and classified the participants into three transition groups: (1) never-caregiving (remained non-caregiving throughout the three waves); (2) new IADL caregiving (from non-caregiving at baseline to IADL caregiving at follow-up waves); and (3) new ADL caregiving (from non-caregiving at baseline to ADL caregiving at follow-up waves).

Changes in living arrangements

Living arrangements of the participants were coded as (1) living with spouse only (S) and (2) living with spouse and other family members (such as adult children, siblings, etc.) together (F). The changes in living arrangements were divided into four groups: (1) SS (remaining living with spouse only); (2) SF (changing from living with spouse only at baseline to living with spouse and other family members); (3) FS (changing from living with spouse and other family members at baseline to living with spouse only); and (4) FF (remaining living with spouse and other family members together).

Covariates

Sociodemographic control variables at baseline included age (years, a continuous variable), education group (1 = no formal education, 2 = primary school, 3 = middle school, and 4 = high school or above), any pension scheme, and self-rated health (a five-point scale from 1 = very poor to 5 = very good). In addition, the wife’s IADL difficulty change and ADL difficulty change were also involved as control variables. The IADL/ADL change was categorized into three groups: worse (from no IADL/ADL difficulty to at least one IADL/ADL difficulty), no change, and better (from at least one IADL/ADL difficulty to no IADL/ADL difficulty).

Analysis strategy

We conducted descriptive and comparative analyses to characterize the sample characteristics, stratified by three caregiving transition groups. The generalized estimating equation (GEE) was employed to examine the impact of spousal caregiving transitions on older husbands’ depressive symptoms. To test Hypothesis 1, Model 1 was specified, with depressive symptoms in 2015 with respect to caregiving intensity transitions as a categorical variable (with never-caregiving as the reference group), adjusting for the set of baseline covariates. To identify whether living arrangements could moderate the impact of transitioning into spousal caregiving on depression (Hypothesis 2), we added interaction terms between caregiving intensity transitions and living arrangement changes into Model 2.

Results

Sample characteristics

summarizes the characteristics of all participants, stratified by the three caregiving transition categories. The distribution of the three groups was never caregivers (n = 690, 59.1%), new IADL caregivers (n = 398, 34.1%) and new ADL caregivers (n = 79, 6.8%). Participants in the SS, SF, FS, and FF living arrangement transition groups accounted for 36.7%, 9.0%, 25.4%, and 29.0%, respectively. No significant differences were found between the three groups concerning living arrangement changes (p = 0.127). Wives of the participants in the new ADL caregiving group had higher odds of worse ADL functions from baseline to follow-up than those whose husbands were non-caregivers or new IADL caregivers (p < 0.001). Wives of the participants who were new IADL/ADL caregivers had higher odds of worse IADL status from baseline to follow-up than those whose husband were non-caregivers (p < 0.001). There were significant differences in depressive symptoms in 2015 between the three groups: the older husbands who newly became ADL and IADL caregivers reported a higher degree of depressive symptoms (M = 9.32, SD = 6.92; M = 7.80, SD = 5.87, respectively) than the non-caregivers (M = 7.50, SD = 6.09) (p < 0.05). No significant differences were found between the care transition categories regarding age, education, pension scheme, and baseline depressive symptoms.

Table 1. Characteristics of the sample by caregiving intensity transition groups (N = 1,167).

Caregiving intensity transitions and depressive symptoms among rural husband caregivers

shows the impact of spousal caregiving transition and living arrangement changes on depressive symptoms over four years. As shown by Model 1 in , Hypothesis 1 was partially supported. Participants who transitioned into ADL caregiving had a significantly higher degree of depressive symptoms at follow-up than their counterparts who remained non-caregivers (B = 1.67, p < 0.05), after controlling for depressive symptoms at baseline, wives’ functional difficulty at follow-up, and other covariates. However, participants who transitioned into IADL caregiving did not differ in their depressive symptoms from those who remained non-caregivers (p > 0.1).

Table 2. Regression coefficients for the effects of care transitions and changes in live arrangement on rural husbands’ depressive symptoms over a 4-year period (N = 1,087).

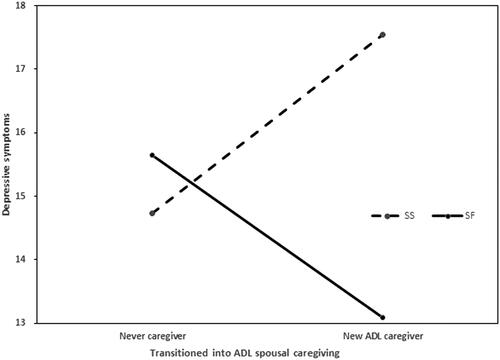

Changing to living with adult children as a protective factor

To test Hypothesis 2, the interactions of caregiving intensity transitions and living arrangement changes were entered into Model 2 (). As shown by the results, Hypothesis 3 was partially supported. The influence of transitioning into ADL caregiving on depressive symptoms was significantly lower among participants who changed from living with spouse only to living with spouse and family members together (B = − 5.37, p < 0.05) compared to those who remained living with spouse only during this period, even after controlling for a set of covariates. As displayed in , for participants who transitioned from non-caregivers to ADL caregivers, the effect of changing from living with a spouse to living with family members was evidenced as coupling with a substantial decrease in the value of depressive symptoms. However, the influence of transitioning into IADL caregiving on depressive symptoms was not moderated by living arrangement changes (p > 0.1).

Figure 1. Predicted scores of depressive symptoms for participants who differed as to whether they transitioned into ADL caregiving and changed from living with spouse only to living with family over four years.

Note: SS = living with spouse only during the period, SF = from living with spouse only to living with family.

Sensitivity analysis

First, all the analyses described above were repeated by using the sample of older wives (age ≥ 60) in rural areas, participated in three waves of CHARLS, and did not provide care in 2011 (as potential caregivers after 2011). The regression model showed that among the older wives in rural areas, transitioning into ADL caregivers (p < 0.05) and IADL caregivers (p < 0.05) was related to a higher level of depression at follow-up. However, inconsistent with the finding from husband samples, the interaction of care transition and living arrangements changes was not significantly related to depressive symptoms (p > 0.1), indicating that living arrangements changes did not moderate the relationship between care transitions and depression among wives in rural areas (see ). Second, considering the small proportion of respondents in the new ADL group, we combined the new ADL group and new IADL group into one group (i.e. new caregiver group) and repeated the regression analysis among husband samples. We also found that rural husbands who newly started caregiver roles and changed from living with spouse only to living with family members reported lower levels of depression (p < 0.05) (see ). Third, we conducted a supplementary analysis to investigated the effect of care transition and changes in other helpers on husband caregivers’ depressive symptoms. The changes in other helpers were classified into four groups: (1) NN = no other helper during the four-year period, (2) NH = from no other helpers to having other helpers, (3) HN = from having other helper to no other helpers, (4) HH = having other helpers during the period. The results showed that for husbands who became ADL caregivers, those in the NH group (p < 0.05) and the HN group (p < 0.01) reported higher levels of depression than those in the NN group, while those in the HH group did not show significant difference in levels of depressive symptoms compared with those in the NN group (p > 0.1) (see Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

This study provided new evidence on husband caregivers by investigating the influence of newly assuming spousal caregiving on older males’ depressive symptoms and identifying whether living arrangements can moderate these effects. The findings confirmed that older husbands who newly assumed the role of ADL caregivers reported an elevated level of depression compared to those who remained non-caregivers during the four-year period. Moreover, changes in living arrangements seemed to moderate this relationship. The mental health deterioration resulting from transitions into ADL caregiving was significantly lower for those who changed from living with spouse only to with family members than for those who remained living with spouse only.

Firstly, the present study identified that older men who entered into ADL caregiving had a higher level of depressive symptoms compared to their never-caregiving counterparts; however, those who transitioned to IADL caregiving did not report significantly higher depressive symptoms. These findings partially support Hypothesis 1 and could enrich the evidence that assuming spousal caregiving responsibility leads to adverse mental health outcomes (Dunkle et al., Citation2014; Lyons et al., Citation2015; Zhao et al., Citation2021) by focusing exclusively on husband caregivers. One the one hand, we found that participants who started IADL caregiving did not report significantly higher depressive symptoms than the never-caregivers did. Similarly, prior research demonstrated that the association between wives’ IADL limitations and husbands’ depression could even be alleviated when husbands providing IADL care (Han et al., Citation2021). This might be because males have been socialized as more task-oriented and took less emotional responsibilities than females (Lutzky & Knight, Citation1994). IADL caregiving in our study consisted of less daunting tasks, such as assisting housework, shopping, and taking medication. In particular, males might be good at some “masculine” tasks, such as managing money (Allen et al., Citation1999). Male caregivers can use task-oriented methods to cope with the transition to IADL caregivers (Robinson et al., Citation2014). Their sense of accomplishment would increase by completing IADL tasks that are relatively easy to master (Han et al., Citation2021). On the other hand, the present study revealed that husbands who entered into ADL caregiving reported higher depression than the never-caregivers did. It was similar to the findings from previous research, because ADL caregiving requires extraordinary efforts from caregivers (Burton et al., Citation2003; Lyons et al., Citation2015). As an outcome of gender role socialization, males are often socialized to purse a livelihood outside, and they are less competent in caregiving than their female counterparts (Allen et al., Citation1999). The ADL caregiving in our study involved personal and demanding tasks such as assisting with toileting and bathing, which may pose an unexpected challenge for male caregivers, who have seldom performed these tasks before (Sanders & Power, Citation2009).

Furthermore, this study revealed that a change in living arrangements from living with spouse only to living with family members could alleviate the negative effect of ADL caregiving on husband caregivers’ mental health. While the supplementary analyses on rural wives did not show significant effects of living arrangements changes on the relationship between caregiving transition and depression. These findings extended existing research on the influence of living arrangements on rural elders’ mental health by adding new evidence from older husband caregivers. Newly assuming the responsibility of ADL caregiving is challenging for males who are unfamiliar with activities they may consider to be “feminine” (Baker et al., Citation2010). The transition into spousal caregiver may be difficult for husbands in rural China, where the traditional concept of men working outside the home and women taking responsibility for housework is deep-rooted. Male caregivers’ perception of their masculine role makes them feel embarrassed to seek outside help (Sanders, Citation2007; Wisch et al., Citation1995). However, changing from co-residence with a spouse only to co-residence with family members enables husband caregivers to have a secondary helper, who may provide assistance in personal care or be a temporary substitute in demand. Prior research supported that the availability of secondary caregivers could alleviate caregivers’ burden and depression, regardless of gender (Sugiura et al., Citation2009). Moreover, male caregivers may also feel isolated and desire to have a small informal support network (Finn & Boland, Citation2021). However, gender role conflict makes male caregivers hold a negative attitude to seeking emotional help (Hill & Donatelle, Citation2004). Living with family members can increase the opportunities for them to receive emotional comfort. In addition, when husband caregivers took on personal care tasks that they might not have done in their earlier married life, they would acquire more praise from coresident family members, thus enhancing their self-efficacy (Lin et al., Citation2012). Moreover, given that the social services for elder care (such as eldercare centers) in rural China are quite limited (Zhao et al., Citation2022), the traditional extended family still plays an essential role in providing instrumental and emotional support to caregivers. Living with family members could be considered as an important protective resource against elevated depression during the transition into ADL spousal caregiving.

Limitations

Several limitations should be noted in interpreting our findings. Firstly, although national representative data has been adopted, there may be selection bias due to our longitudinal design, given that respondents who had not completed follow-up surveys were dropped. Those excluded due to loss at follow-up may differ from the participants included in this study, leading to potential bias and limiting the generalizability of our findings. Secondly, we did not know the reasons why participants remained or changed their caregiving roles or living arrangements, as well as the exact time points when transitions occurred. We were unable to recognize whether care receivers had dementia or not, as surveys did not include questions to identify dementia or asked about dementia caregiving. Therefore, some potential confounders might be overlooked. Thirdly, our findings were based on older husbands in rural China and should be carefully interpreted in different settings.

Conclusion

Based on a nationally representative sample of older Chinese people, this longitudinal study shed light on the impact of taking on the spousal caregiver role on rural husbands’ depressive symptoms and how living arrangements modify this relationship. The study identified transitioning into ADL caregiving as a risk factor for an elevated level of depression over time in husbands. One unique finding of this study is that the disadvantageous effects of becoming a husband caregiver providing ADL assistance can be moderated by changes in living arrangement, specifically, from living with a spouse only to living with family members. Given the insufficient elder care services, such as daycare centers in rural China, co-residence with family members can serve as an important practical and emotional support resource, which may help older husbands deal with gender role conflict in ADL caregiving and alleviate adverse mental health outcomes. Meanwhile, we should also note that large-scale rural-to-urban migration makes many older adults in rural areas empty-nested and cannot receive their children’s assistance in person. Therefore, it is necessary to improve eldercare services in rural areas. Meanwhile, gender-sensitive and collaborative support services are suggested to be provided for male caregivers (Finn & Boland, Citation2021).

Ethical approval

The CHARLS was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Peking University. All participants provided informed consent.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30.2 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, S. M., Goldscheider, F., & Ciambrone, D. A. (1999). Gender roles, marital intimacy, and nomination of spouse as primary caregiver. The Gerontologist, 39(2), 150–158.

- Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B., & Patrick, D. L. (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10(2), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0749-3797(18)30622-6

- Bai, X., Liu, C., Baladon, L., & Rubio-Valera, M. (2018). Multidimensional determinants of the caregiving burden among Chinese male caregivers of older family members in Hong Kong. Aging & Mental Health, 22(8), 986–995. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1330872

- Baker, K. L., Robertson, N., & Connelly, D. (2010). Men caring for wives or partners with dementia: Masculinity, strain and gain. Aging & Mental Health, 14(3), 319–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860903228788

- Burton, L. C., Zdaniuk, B., Schulz, R., Jackson, S., & Hirsch, C. (2003). Transitions in spousal caregiving. The Gerontologist, 43(2), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/43.2.230

- Choi, H., & Marks, N. F. (2006). Transition to caregiving, marital disagreement, and psychological well-being: A prospective US national study. Journal of Family Issues, 27(12), 1701–1722. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X06291523

- Clarke, P., Twardzik, E., D’Souza, C., & Meade, M. (2021). Aging with a disability. In D. J. Lollar, W. Horner-Johnson, & K. Froehlich-Grobe (Eds.), Public health perspectives on disability: Science, social justice, ethics, and beyond (pp. 225–250). Springer US.

- Conde-Sala, J. L., Garre-Olmo, J., Turró-Garriga, O., Vilalta-Franch, J., & López-Pousa, S. (2010). Differential features of burden between spouse and adult-child caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease: An exploratory comparative design. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 47(10), 1262–1273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2010.03.001

- Ducharme, F., Lévesque, L., Lachance, L., Zarit, S., Vézina, J., Gangbè, M., & Caron, C. D. (2006). Older husbands as caregivers of their wives: A descriptive study of the context and relational aspects of care. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43(5), 567–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.07.007

- Ducharme, F., Lévesque, L., Zarit, S. H., Lachance, L., & Giroux, F. (2007). Changes in health outcomes among older husband caregivers: A one-year longitudinal study. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 65(1), 73–96. https://doi.org/10.2190/9754-21rh-5148-8025

- Dunkle, R. E., Feld, S., Lehning, A. J., Kim, H., Shen, H.-W., & Kim, M. H. (2014). Does becoming an ADL spousal caregiver increase the caregiver’s depressive symptoms? Research on Aging, 36(6), 655–682. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027513516152

- Feld, S., Dunkle, R. E., Schroepfer, T., & Shen, H.-W. (2010). Does gender moderate factors associated with whether spouses are the sole providers of IADL care to their partners? Research on Aging, 32(4), 499–526. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027510361461

- Figueiredo, D., Jácome, C., Gabriel, R., & Marques, A. (2016). Family care in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: What happens when the carer is a man? Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 30(4), 721–730. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12298

- Finn, C., & Boland, P. (2021). Male family carers’ experiences of formal support - a meta-ethnography. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 35(4), 1027–1037. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12919

- Gibbons, C., Creese, J., Tran, M., Brazil, K., Chambers, L., Weaver, B., & Bédard, M. (2014). The psychological and health consequences of caring for a spouse with dementia: A critical comparison of husbands and wives. Journal of Women & Aging, 26(1), 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2014.854571

- Graham, H. (1983). Caring: A labour of love. In J. Finch & D. Groves (Eds.), A labour of love: Women, work, and caring (pp. 13–30). Routledge and Kehan Paul.

- Gruijters, R. J. (2017). Family care-giving and living arrangements of functionally impaired elders in rural China. Ageing and Society, 37(3), 633–655. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X15001397

- Guo, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2021). New perspective on intergenerational relations, social pensions, and elderly care in urban China. Sociological Studies, 36(2), 160–180.

- Hajek, A., & König, H.-H. (2016). The effect of intra- and intergenerational caregiving on subjective well-being-evidence of a population based longitudinal study among older adults in Germany. PloS One, 11(2), e0148916. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148916

- Han, S. H., Kim, K., & Burr, J. A. (2021). Take a sad song and make it better: Spousal activity limitations, caregiving, and depressive symptoms among couples. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 281, 114081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114081

- Hill, W. G., & Donatelle, R. J. (2004). The impact of gender role conflict on multidimensional social support in older men. International Journal of Men’s Health, 4(3), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.3149/jmh.0403.267

- Johnson, R. J., & Wolinsky, F. D. (1993). The structure of health status among older adults: Disease, disability, functional limitation, and perceived health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 34(2), 105–121. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137238

- Kaufman, J. E., Lee, Y., Vaughon, W., Unuigbe, A., & Gallo, W. T. (2019). Depression associated with transitions into and out of spousal caregiving. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 88(2), 127–149. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091415018754310

- Ketcher, D., Trettevik, R., Vadaparampil, S. T., Heyman, R. E., Ellington, L., & Reblin, M. (2020). Caring for a spouse with advanced cancer: Similarities and differences for male and female caregivers. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 43(5), 817–812. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00128-y

- Kramer, B. J. (2000). Husbands caring for wives with dementia: A longitudinal study of continuity and change. Health & Social Work, 25(2), 97–107. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/25.2.97

- Lam, T-p., Chi, I., Piterman, L., Lam, C., & Lauder, I. (1998). Community attitudes toward living arrangements between the elderly and their adult children in Hong Kong. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 13(3), 215–228. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006517226595

- Lévesque, L., Ducharme, F., Zarit, S. H., Lachance, L., & Giroux, F. (2008). Predicting longitudinal patterns of psychological distress in older husband caregivers: Further analysis of existing data. Aging & Mental Health, 12(3), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860801933414

- Li, M., & Dai, H. (2019). Determining the primary caregiver for disabled older adults in Mainland China: Spouse priority and living arrangements. Journal of Family Therapy, 41(1), 126–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12213

- Lin, I.-F., Fee, H. R., & Wu, H.-S. (2012). Negative and positive caregiving experiences: A closer look at the intersection of gender and relatioships. Family Relations, 61(2), 343–358. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2011.00692.x

- Liu, H., & Lou, V. W. Q. (2019). Transitioning into spousal caregiving: Contribution of caregiving intensity and caregivers’ multiple chronic conditions to functional health. Age and Ageing, 48(1), 108–114. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy098

- Lutzky, S. M., & Knight, B. G. (1994). Explaining gender differences in caregiver distress: The roles of emotional attentiveness and coping styles. Psychology and Aging, 9(4), 513–519. https://doi.org/10.1037//0882-7974.9.4.513

- Lyons, J. G., Cauley, J. A., & Fredman, L. (2015). The effect of transitions in caregiving status and intensity on perceived stress among 992 female caregivers and noncaregivers. The Journals of Gerontology Series A: Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences, 70(8), 1018–1023. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/glv001

- Mausbach, B. T., Chattillion, E. A., Roepke, S. K., Patterson, T. L., & Grant, I. (2013). A comparison of psychosocial outcomes in elderly Alzheimer caregivers and noncaregivers. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2012.10.001

- Ministry of Civil Affairs of China. (2018). Statistical bulletin of the development of social servceis 2017. http://www.mca.gov.cn/article/sj/tjgb/2017/201708021607.pdf

- Mott, J., Schmidt, B., & MacWilliams, B. (2019). Male caregivers: Shifting roles among family caregivers. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 23(1), E17–E24. https://doi.org/10.1188/19.CJON.E17-E24

- Ng, A. C. Y., Phillips, D. R., & Lee, W. K-m. (2002). Persistence and challenges to filial piety and informal support of older persons in a modern Chinese society: A case study in Tuen Mun, Hong Kong. Journal of Aging Studies, 16(2), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0890-4065(02)00040-3

- O’Neil, J. M. (1981). Patterns of gender role conflict and strain: Sexism and fear of femininity in men’s. Lives, 60(4), 203–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2164-4918.1981.tb00282.x

- Oh, D. H., Park, J. H., Lee, H. Y., Kim, S. A., Choi, B. Y., & Nam, J. H. (2015). Association between living arrangements and depressive symptoms among older women and men in South Korea. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 50(1), 133–141.

- Pearlin, L. I., & Bierman, A. (2013). Current issues and future directions in research into the stress process. In C. S. Aneshensel, J. C. Phelan, & A. Bierman (Eds.), Handbook of the sociology of mental health (pp. 325–340). Springer Netherlands.

- Pinquart, M., & Sörensen, S. (2006). Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: An updated meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(1), P33–P45. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.1.P33

- Ren, Q., & Treiman, D. J. (2015). Living arrangements of the elderly in China and consequences for their emotional well-being. Chinese Sociological Review, 47(3), 255–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/21620555.2015.1032162

- Robinson, C. A., Bottorff, J. L., Pesut, B., Oliffe, J. L., & Tomlinson, J. (2014). The male face of caregiving: A scoping review of men caring for a person with dementia. American Journal of Men’s Health, 8(5), 409–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988313519671

- Sanders, S. (2007). Experiences of rural male caregivers of older adults with their informal support networks. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 49(4), 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1300/J083v49n04_06

- Sanders, S., & Power, J. (2009). Roles, responsibilities, and relationships among older husbands caring for wives with progressive dementia and other chronic conditions. Health & Social Work, 34(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/34.1.41

- Sharma, N., Chakrabarti, S., & Grover, S. (2016). Gender differences in caregiving among family - caregivers of people with mental illnesses. World Journal of Psychiatry, 6(1), 7–17. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v6.i1.7

- Silverstein, M., Cong, Z., & Li, S. (2006). Intergenerational transfers and living arrangements of older people in rural China: Consequences for psychological well-being. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(5), S256–S266. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.5.s256

- Song, Q. (2017). Facing “Double Jeopardy”? Depressive symptoms in left-behind elderly in rural China. Journal of Aging and Health, 29(7), 1182–1213. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264316659964

- Sugiura, K., Ito, M., Kutsumi, M., & Mikami, H. (2009). Gender differences in spousal caregiving in Japan. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 64(1), 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbn005

- Swinkels, J., Tilburg, T. v., Verbakel, E., & Broese van Groenou, M. (2019). Explaining the gender gap in the caregiving burden of partner caregivers. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74(2), 309–317. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx036

- Tretteteig, S., Vatne, S., & Rokstad, A. M. M. (2016). The influence of day care centres for people with dementia on family caregivers: An integrative review of the literature. Aging & Mental Health, 20(5), 450–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2015.1023765

- Verbrugge, L. M., Latham, K., & Clarke, P. J. (2017). Aging with disability for midlife and older adults. Research on Aging, 39(6), 741–777. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027516681051

- Wagner, M., & Brandt, M. (2018). Long-term care provision and the well-being of spousal caregivers: An analysis of 138 European regions. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73(4), e24–e34. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx133

- Wisch, A. F., Mahalik, J. R., Hayes, J. A., & Nutt, E. A. (1995). The impact of gender role conflict and counseling technique on psychological help seeking in men. Sex Roles, 33(1–2), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01547936

- Wolff, J. L., & Kasper, J. D. (2006). Caregivers of frail elders: Updating a national profile. The Gerontologist, 46(3), 344–356. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/46.3.344

- Wong, J. S., & Hsieh, N. (2019). Functional status, cognition, and social relationships in dyadic perspective. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 74(4), 703–714. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx024

- Xu, Q. (2018). The impact of living arrangement on the depressive symptoms of the Chinese elderly—Evidence from CHARLS. Sociological Review of China, 6(04), 47–63.

- Ye, M., & Chen, Y. (2014). The influence of domestic living arrangement and neighborhood identity on mental health among urban Chinese elders. Aging & Mental Health, 18(1), 40–50.

- Yuan, X. (2019). The current situation of empty-nested elderly in rural China. People’s Tribune, (28), 69–71. doi:CNKI:SUN:RMLT.0.2019-28-028

- Yue, Z., & Ma, J. (2017). The impact of living arrangement on the mental health of rural elderly in China. Journal of Hunan Agricultural University(Social Science), 18(06), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.13331/j.cnki.jhau(ss).2017.06.011

- Zarit, S. H., Todd, P. A., & Zarit, J. M. (1986). Subjective burden of husbands and wives as caregivers: A longitudinal study. The Gerontologist, 26(3), 260–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/26.3.260

- Zhao, Y., Hu, Y., Smith, J. P., Strauss, J., & Yang, G. (2014). Cohort profile: The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). International Journal of Epidemiology, 43(1), 61–68. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dys203

- Zhao, X., Liu, H., Fang, B., Zhang, Q., Ding, H., & Li, T. (2021). Continuous participation in social activities as a protective factor against depressive symptoms among older adults who started high-intensity spousal caregiving: Findings from the China health and retirement longitudinal survey. Aging & Mental Health, 25(10), 1821–1829. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1822283

- Zhao, X., Li, D., Zhang, Q., & Liu, H. (2022). Spousal concordance in frailty predicting mental and functional health decline: A four-year follow-up study of older couples in urban and rural China. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 31(5–6), 679–688. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15927