Abstract

Objectives

Short breaks support the wellbeing of people living with dementia (PLWD) and their unpaid carers. However, little is known about the benefits of community-based short breaks. The objective of this study was to conduct interviews with stakeholders of a Shared Lives (SL) day support service to explore mechanisms and outcomes for the service. The aim of the study was to refine a logic model for a SL day support service for PLWD, their unpaid carers, and paid carers. This logic model shall form the basis for a Social Return on Investment evaluation to identify the social value contributed by the service.

Methods

Thirteen interviews were conducted with service stakeholders including PLWD, unpaid carers and paid carers. Framework analysis assisted in the synthesis of the findings into a logic model.

Results

The logic model refined through the interviews, detailed service mechanisms (inputs, activities, outputs) and outcomes. An overarching theme from the interviews concerned the importance of triadic caring relationships, which conferred benefits for those involved in the service.

Conclusion

SL day support fosters triadic caring relationships, and interview data suggests that these relationships are associated with meaningful outcomes for PLWD, their unpaid carers, and paid carers. We highlight the implications for policy, practice, and future research.

SUBJECT CLASSIFICATION CODES:

Background

Dementia brings social, economic and health costs and is a global priority with an increasing number of people living with the condition (Pickett & Brayne, Citation2019). People living with dementia (PLWD) can feel socially isolated, stigmatised, and marginalised, which may affect their confidence and decrease their willingness to participate in community activities (Bhatt et al., Citation2019; Rochira, Citation2018). Many PLWD wish to remain in their own home (Rapaport et al., Citation2020) supported through the help of friends, neighbours, and relatives (hereafter called unpaid carers). In the UK, approximately two thirds of PLWD reside in the community supported by unpaid carers (Alzheimer’s Society, Citation2015). Unpaid carers can find aspects of caring positive, for example, experiencing personal accomplishment (Lindeza et al., Citation2020; Tulloch et al., Citation2022). However, they can also report negative mental and physical health impacts (Alzheimer’s Society, Citation2020a; Carers UK, Citation2020; Ruiz-Fernández et al., Citation2019; Tulek et al., Citation2020). Providing care can impact on the relationship between the unpaid carer and the PLWD, as their respective roles and responsibilities change (Carers Trust, Citation2020; Clark et al., Citation2019; Fletcher, Citation2020; Van Bruggen et al., Citation2016).

The Coronavirus pandemic exacerbated the challenges faced by PLWD and unpaid carers (Savla et al., Citation2021). Many PLWD experienced greater unmet care needs due to the reduction in support from health and social care services (Masterson-Algar et al., Citation2022). This resulted in unpaid carers providing more care (Alzheimer’s Society, Citation2020b), finding it difficult to access breaks from their caring role (Carers UK, Citation2020) and contributing to an increase in unpaid carer reported anxiety and depression (Truskinovsky et al., Citation2022).

The purpose of a short break is to support the caring relationship and promote the health and wellbeing of the unpaid carer, supported person, and other family members affected by the caring situation (Shared Care Scotland, Citation2017). PLWD can engage in meaningful activities leading to improved mental, physical, and psychosocial wellbeing (Kirk & Kagan, Citation2015; Rochira, Citation2018) and unpaid carers can experience respite, and a life alongside caring (Carers Trust, Citation2020; Welsh Government, Citation2021). Most short breaks research explores day centre care and residential respite services (Seddon et al., Citation2021). Whilst these services can provide good support (O’Shea et al., Citation2020), they may not be the preferred choice for PLWD or unpaid carers (Allen et al., Citation2020; de Bruin et al., Citation2019; O’Shea et al., Citation2019; Phillipson et al., Citation2013). Alternative types of short breaks might support personalised outcome focused care for those who do not want to access day services (Welsh Government, Citation2014). Whilst there are recommendations to invest in these alternatives (Welsh Government, Citation2014, Citation2021) there is little research to inform their planning, commissioning, and delivery (Kirk & Kagan, Citation2015; Shared Care Scotland, Citation2020).

One alternative short break option is Shared Lives (SL), an internationally recognised model of support which integrates people into their local community (Shared Lives Plus, Citation2014, Citation2020):

There is a matching process whereby paid SL carers and people with support needs are connected based on shared interests and dispositions

The SL carer provides support in their own home, and they include the person with support needs in their family and community life

The SL carer provides individualised care, supporting only a few people at any one time.

TRIO is a SL day support service for people living with mild to moderate dementia and their unpaid carers, based in a semi-rural part of Wales. When PLWD (called citizens by the service and hereafter) are referred (or self-refer), they are matched with a SL carer (called a companion) and two or three citizens who share similar interests. This group then meets for six-hours each week. Companions are self-employed and work semi-autonomously (Person Shaped Support (PSS), n.d.). All SL schemes are regulated and monitored, and companions are approved and registered with the Care Inspectorate Wales (CIW) according to the Regulation and Inspection of Social Care Act (Wales), 2016 (Shared Lives Plus, Citation2014; Citation2020).

Aims

This study explores TRIO as an exemplar community-based short break option. It forms part of a three phase Social Return on Investment (SROI) evaluation. SROI is a form of economic analysis that explores the added social value of an intervention (Nicholls et al., Citation2012):

Phase 1, a rapid evidence review of the wider SL literature (under peer review) identified potential stakeholder groups, mechanisms and outcomes to inform a draft TRIO logic model

Phase 2 refined the logic model for TRIO through stakeholder interviews, following the guidance on evaluating complex interventions (MRC, Citation2015) and best SROI practice (Nicholls et al., Citation2012)

Phase 3 will see the completion of the SROI evaluation, resulting in an estimate of the social value that TRIO generates for every £1 invested in it.

This paper reports on Phase 2 of the study.

Methods

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Bangor University Healthcare Sciences (Post-reg) Ethics and Research Committee (reference; 2020-16793). Approval was obtained from the Health Research Authority Research Ethics Committee [IRAS ID: 297965] to approach staff at local memory clinics. Concordant with the Welsh Language Standards Regulations (Welsh Government, Citation2018) all study information was provided in English and Welsh, and participants could partake in an interview in Welsh. The researcher conducting the interviews met with the citizen twice online to discuss the study, and what taking part would entail. This helped establish the citizen was able to understand, sufficiently retain and consider the study information. It also established that they were able to communicate their wish to participate.

Sampling and participants

Informed by the stakeholder groups identified in the rapid evidence review, purposive sampling reached out to:

Citizens

Unpaid carers, including those whose relatives/friends were no longer attending TRIO

Companions

Wider community and professional stakeholders

Procedure

Inclusion criteria were that the individual was a TRIO stakeholder (i.e. a citizen, unpaid carer, companion, professional or community member), with capacity to provide informed consent. People unable to provide informed consent and people who were not TRIO stakeholders were ineligible for the study. Citizens, unpaid carers, and companions were approached by the service, who ensured there were no contraindications to their involvement. Contraindications could include a known lack of capacity, or personal circumstances that made it inappropriate to approach the individual. For instance, this could be due to a recent bereavement, safeguarding concerns or a situation that could put the researcher at risk. Interested individuals then contacted the research team directly or the service contacted the research team on their behalf if requested. Once eligibility was checked a mutually convenient interview time and date were arranged.

Community and professional stakeholders were contacted through publicly available email addresses, adverts sent to relevant mailing lists and emails from the service. Recruited individuals were asked to share information about the study with their associates.

Interviews took place between May and October 2021. Due to the enforcement of the Health Protection (Coronavirus Restrictions) (Wales) Regulations (Welsh Government, Citation2020) interviews were conducted via telephone or online. All interviews were audio-recorded and verbal consent was received at the start of each interview. To provide additional support we sent participants a copy of the interview questions in advance. Interviews could take place over several calls if required and were conducted by a researcher experienced in qualitative research and working with potentially vulnerable client groups.

Interviews

Interview questions (see Supplementary File 1 for the interview topic guides) were developed with input from the study Project Advisory Group (PAG), which included citizen, unpaid carer, and companion members. We engaged citizens and unpaid carers in Biographic Narrative Interpretive Method interviews. This method is useful when exploring applied research areas (Wengraf, Citation2004; Citation2008) and uses an initial generative question (in this instance, to explore the importance of short breaks). After probing for further details about key points, questions informed by the draft TRIO logic model were asked. Other stakeholders were engaged in semi-structured interviews to collect their experiences and perceptions (De Jonckheere & Vaughn, Citation2019) with questions again informed by the draft TRIO logic model.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed, checked for accuracy, and anonymised. We used Framework Analysis due to its transparency, clarity, and suitability for use in applied research (Ritchie & Spencer, Citation1994, Citation2002). It is also appropriate when working with an a-priori plan for data extraction (Pope et al., Citation2000; Srivastava & Thomson, Citation2009). The analysis retains thick data description and enables comparisons within and between respondent groups (Gale et al., Citation2013; Pope et al., Citation2000). Five steps were followed:

Familiarisation: the researcher read and re-read the interviews

Identification of a thematic framework: the framework comprised the logic model components (inputs, outputs, activities, outcomes, assumptions, and context)

Indexing: relevant text was identified and marked with a suitable label

Charting: indexed text was collated into tables in Microsoft Word according to the framework components

Mapping and interpretation: the findings were compared to the draft TRIO logic model developed following the rapid evidence review. The refined logic model was sense-checked by the PAG.

Results

Interviews were conducted with:

6 unpaid carers (2 unpaid carer’s relatives had recently left TRIO at the point of the interview)

5 companions

1 citizen

1 dementia support worker

All participants were female. Interviews lasted between 40 and 80 min. Data saturation was evident for companions and unpaid carers, with no new themes arising from the final two companion and unpaid carer interviews.

Overview

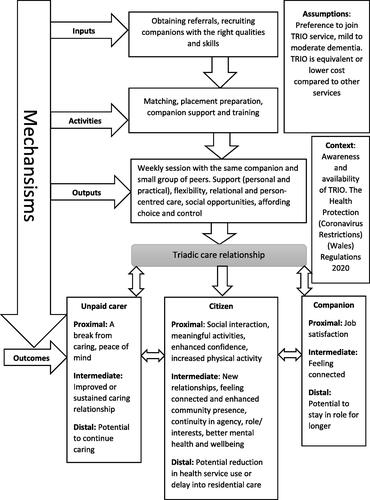

Respondents identified key components of the TRIO logic model, as summarised in . This enabled us to refine our initial logic model to make it specific to TRIO, as some themes identified in the wider Shared Lives literature did not resonate with the learning gained from TRIO stakeholders. For example, rather than reporting ‘improved contact with their own family’, stakeholders talked about the service maintaining and improving caring relationships. As we refined the logic model, an overarching theme emerged concerning triadic caring relationships between citizens, unpaid carers, and companions. In brief, companions fostered trust and confidence with citizens and unpaid carers through shared decision making and shared interests. Citizens enjoyed meaningful activities and were able to continue valued roles and agency. Unpaid carers experienced a break with peace of mind. Companions felt satisfied in their role and enjoyed their relationships with citizens and unpaid carers. Below we describe in more detail the factors that contributed to this relationship and its outcomes.

‘A friend and not a carer’

Unpaid carers (and the citizen) referred to their companion as a friend, or member of their extended family, signifying that a personal rather than transactional relationship had been established. Unpaid carers and companions suggested this friendship was important if citizens were to engage with TRIO, as many citizens could be reluctant to accept support that had connotations of receiving ‘care’. One companion reflected this was a ‘personal journey’ taken with the citizen. Companions explained that they did not wear a uniform or badge and could be mistaken for a relative or friend when out with the citizen. Companions also formed a strong emotional bond with the citizen, who had become part of their home life and family. Using their house as a base contributed to the ‘normality’ of their relationship:

If you’ve got a personal friend, they would knock on your door and come into your house, wouldn’t they? It’s just such a lovely thing to do and if you were to go to your friend’s house you would be welcomed (Companion 4)

Companion qualities and the matching process

Unpaid carers described companions as ‘kind-hearted’, ‘caring’ and ‘approachable’. The skilled work of the companions ensured there were opportunities for reciprocity, meaning that the citizen could contribute to the relationship:

The people I was supporting with dementia it would make them feel almost like they were helping me do a job (Companion 4)

Mum was a little bit hesitant at first, but when she met the companion, the carer at the time – didn’t look back, didn’t look back at all – it was such a lightbulb moment to see that engagement back in her – actually wanting to do something (Unpaid carer 1)

On paper you think, well these two people will work really well, but personality doesn’t work like that, and because of the disease, because of the illness, that changes personalities as well (Unpaid carer 1)

Consistency and flexibility

The consistency with which the citizen, companion and unpaid carer interacted allowed relationships to develop and evolve naturally. For unpaid carers, the consistency of their relationship with the companion helped to mitigate the inherent uncertainties of caring for someone living with dementia, likened to ‘shifting sands’ by one unpaid carer, whereby ‘you get one solution in, then something else crops up’. At the same time companions had the autonomy to be flexible and tailor support to suit the citizen and unpaid carer:

Any appointments that mum had, didn’t want to go out, or didn’t feel particularly well, then the carer would work around that with mum, and with the other lady as well (Unpaid carer 1)

I did feel comfortable asking them – next week could you do half nine or next week instead of dropping [name] off at three (Unpaid carer 2)

If it wasn’t for [Companion] mum wouldn’t have heard from anyone apart from us, so I think during COVID-19, having her as that constant source had been a link to the outside world as well (Unpaid carer 3)

Choice and control

In the triadic caring relationship, all partners believed they had some choice and control, especially in decision-making. This was central to citizens feeling they were in a ‘normal’ relationship, rather than being supervised or ‘cared for’, and contributed to their experience of autonomy:

She takes me where I want to go, she asks – where do you want to go today? You choose (Citizen)

I think my husband felt very included as he felt he was having a say what the activity would be, what the plan was with the day and it wasn’t like he was supervised, it didn’t feel like he was in a supervised environment and being directed and told what to do – there was still autonomy […] there was still a veneer of independence for him which I think was very, very, good for him (Unpaid carer 2)

She said I don’t want to sit round singing songs and doing unmeaningful things I want to be living my life as best I can. […] To be locked in somewhere and not to be able to do things that she wanted to do and be told when you are having something to eat, this is what you are having, it doesn’t work for everybody (Unpaid carer 1)

It’s just that checking in with me, they don’t need to do it so much now cos we all know how each other works they have my trust […] I say they are classed as more like family – that’s how I see them. I knew she was being looked after and I knew if there was a problem, I would get a phone call straight away (Unpaid carer 3)

As long as you use your initiative and don’t be too laissez-faire. You know your limits, basically. As long as you know your limits then it’s a lovely way of working. It really is […] you’ve still got to use that sort of initiative to think, hang on a minute. Stop. I’m not allowed to do this as part of the policies and procedures (Companion 3)

Citizens: Continuity in role and interests

The presence of the companion, and oftentimes another citizen could help re-build citizen’s confidence to engage in community activities and social exchanges.

Encouraged and supported by the companion, they had opportunities to re-integrate into the community visiting shops, cafes, and other activities of their choosing. In immersing themselves in these ‘normal’ roles and interests, the citizen could metaphorically ‘leave the dementia at home’:

So, I think it’s more about communication, and friendship, and just feel involved with everyday community and society, really (Companion 3)

It’s really good cos it enables them to get out and about in the community and leave the dementia at home (Companion 2)

Unpaid carers: A break from caring with peace of mind

Unpaid carers described using the time their relative was with their companion to meet their own needs, including having time to themselves. Contributing to their break was a peace of mind, as they trusted their relative was safe and enjoying their time. This assuaged any feelings of guilt about temporarily passing their ‘responsibility’ to someone else, and the break signified relief and release:

When you’re looking after somebody like that 24/7, it’s very hard work. It’s frustrating. It can get very depressing, and just to know that he’s out and I can do what I want to do. To me, it’s just great. […] Knowing that he’s out, at least, getting some fresh air and, hopefully, enjoying his outing. It’s just peace of mind (Unpaid carer 7)

Citizens and unpaid carers: Sustained and/or improved relationships

Dynamics change when people enter a triadic relationship. The interviews suggested these shifts could improve and sustain the caring relationship between citizens and unpaid carers. Several factors contributed to this. The regular breaks helped unpaid carers to ‘recharge their batteries’:

If you don’t have that break, I think your relationship would just completely break down, completely […] I think it does him good to get away from me for a bit, as well. I think it works both ways, really (Unpaid carer 7)

Can’t wait for her to come in the morning when I wake up, I ask is it [name] day…is it [name] day? Yes or no. If no, it’s a miserable day […] I’m quite excited when she’s coming (Citizen)

He wouldn’t always completely remember everything they did but he did know very clearly that he’d been out for the day […]. It was obviously better for me as I wasn’t having to deal with a grumpy churlish stroppy teenager as that’s unfortunately how it was manifesting itself in that sort of behaviour, so I kind of got an evening of a pleasant person, it was good (Unpaid carer 2)

Companions: rewarding and satisfying work

Companions derived satisfaction from their work in part due to the flexibility and autonomy they were afforded:

I wanted time to spend with the older generation and not worry about the clock or what I had to do […] there’s no time watching, no clock and I said, I said, well that sounds like a lovely job (Companion 2)

I think that’s what I love doing, as well, raising awareness of the stigma attached out there and trying to show the community that there are hidden disabilities out there and they shouldn’t be judgmental (Companion 3)

To see them interacting with other people and to have positive feedback from themselves and their family, you know, they’ve had a nice day and are we coming next week, and you know, then I think that we are doing a good job (Companion 1)

They are part of your family now, so it’s just like – someone wouldn’t invite you and not invite your children would they […] they become like, good friends you know, almost like your nan, aunt or uncle and you ring them up and say, how are you doing? (Companion 4)

It’s sad to watch them going, but knowing that you gave them that time, the past few years, that they’ve actually enjoyed themselves, they still stayed within community, being part of everyday life, it’s pretty amazing (Companion 5)

Tensions: balancing a paid role and relational care

Despite the benefits of the triadic caring relationships, companions implied that there were some tensions. Companions were in the invidious position of balancing a ‘paid role’ with relational care. They recognised some constraints on their role arising from a working context. For instance, their need to respond to citizen and unpaid carer needs within their paid hours of employment. This could feel uncomfortable psychologically:

It can be very difficult because I’m not one of these persons that will say, ‘Right, I’m contracted to that many hours. I’m sorry, I can’t come and see you. You’ve had a fall, but fine, I can’t come until next week’, but with this employment, that’s the way it is. […] So, through COVID, and still now, I’m doing a lot more hours than I should be because of crisis situations (Companion 3)

If I’m looking after someone and it’s a nice day we’ll be out on the beach and a towel in my bag and, well you know, you’re constantly doing risk assessments (Companion 4)

Discussion

The interviews expand our understanding of what matters to people involved in community-based short breaks. The findings challenge traditional ideas about what short breaks involve, and how and where they are provided.

Our study illustrates the importance of recognising the caregiving triad, involving the citizen, unpaid carers, and paid carers (Sims-Gould & Martin-Matthews, Citation2007). Our findings are consistent with other research exploring triadic caring relationships and we highlight contributory factors and outcomes. For instance, good communication between triad members facilitates the acceptance and subsequent support by PLWD and their unpaid carers (O’Shea et al., Citation2019; Tuijt et al., Citation2021). When the wellbeing of PLWD is supported, then so is the wellbeing of the unpaid carer (Rochira, Citation2018). Nolan et al. (Citation2004) have highlighted the importance of mutual and reciprocal relationships between those involved in the dementia care triad. They referred to the outcomes of these care triads as ‘senses’ namely, belonging, continuity, purpose, security, significance and achievement. These senses resonate with the outcomes reported here.

The importance of placing the individual and their needs at the centre of their care and support is highlighted in national and international social care policy. For instance, this is a key principle set out within the Social Services and Wellbeing Act in Wales (Welsh Government, Citation2014). In Sweden, the Social Services Act (Citation2001) mandates personalised breaks for unpaid carers, and in Australia person-centred, relational support is encouraged through the Integrated Carer Support Service Model (Australian Government, Citation2019).

The SL model provides person-centred care through relational support, underpinned by a matching process, which is seen as key to its success (Brookes & Callaghan, Citation2013; Sims-Gould & Martin-Matthews, Citation2007). In other SL services, successful matches have resulted in SL carers being recognised as a friend, or part of the family (Brookes et al., Citation2016; Callaghan et al., Citation2017). A matching process and placement preparation enable the paid carer to have a wider understanding of the PLWD: their proclivities and life history. It is well established that person-centred and relational support helps maintain the interests and identity of PLWD (Kitwood, Citation1993; Citation1997) and can confer opportunities for PLWD to engage in meaningful activities (Genoe & Dupuis, Citation2011; Greenwood et al., Citation2001).

The companions also engaged in ‘positive risk taking’ with the citizen, to identify and provide opportunities meaningful to them. This strength-based approach is also recognised as important in maintaining the wellbeing of PLWD (Dickins at al., 2018; Morgan, Citation1996; Morgan & Williamson, Citation2014; Rahman & Swaffer, Citation2018). Nonetheless, managing risk in dementia care can be a difficult balance (Clarke & Mantle, Citation2016; Dickins et al., Citation2018), and companions acknowledged that they needed to engage in constant evaluation and assessment.

The companion’s relationship with citizens and their unpaid carer could be described as ‘fictive kinship’: companions are not related, but accept the obligation, affection, and duties to become more like family (Karner, Citation1998). As reflected in our findings, this relationship contributed to the companion’s job satisfaction (Ben-Arie & Iecovich, Citation2014; Karner, Citation1998; Pollock et al., Citation2021), which perhaps promoted consistency of care (Edvardsson et al., Citation2014). However, as companions noted, maintaining flexible, consistent, and relational support sometimes required working outside of paid hours, for example, making phone calls in their own time to the citizen and unpaid carer. Turner et al. (Citation2020) have similarly reported on homecare workers going ‘the extra mile’; using their own time and money to undertake affective voluntary labour. Pollock et al. (Citation2021) in their study with unpaid carers acknowledge there is an ambiguity in relationships between homecare workers, regarded as ‘fictive kin’, in providing support in a commercial arrangement. Supportive working conditions seem essential to help paid carers navigate these ambiguities (Manthorpe et al., Citation2017; Turner et al., Citation2020).

Strengths and limitations of the study

Most short break research focusses on dyadic caring relationships between individuals with support needs and unpaid carers (Tuijt et al., Citation2021), or paid staff (Koster & Nies, Citation2022). These interviews have instead explored triadic caring relationships.

Small sample sizes do not preclude valuable insights in qualitative research (Crouch & McKenzie, Citation2006) and the interviews provided detailed, rich accounts, with data saturation achieved for companions and unpaid carers. Further, as respondents expressed challenging as well as positive experiences it is unlikely that people withheld opinions due to fear of repercussions or negative impacts on their service or employment.

Nonetheless, we acknowledge that with only one citizen participant, our understanding of citizen outcomes was primarily based on companions and unpaid carers’ reports. Citizens might have been reluctant to engage because interviews needed to be online or by telephone: digital literacy can be a challenge for some older people (Hargittai et al., Citation2019). Our sample could not adequately capture the views of wider community and professional stakeholders. It is probable that these individuals were unable to participate due to the pressures of responding to the Coronavirus pandemic (Carers UK, Citation2021). These limitations must be considered when interpreting the study findings.

Areas for further research

Our sample was all female reflecting the gender imbalance in care (Alzheimer’s Society, Citation2020a) and it would be interesting to purposefully seek the views of male paid and unpaid carers. It would also be useful to seek out partners in triadic caring relationships that had not been successful, to investigate what factors undermined the relationship and the impacts on outcomes. This is especially relevant considering the paucity of research exploring the experiences of short breaks from the perspectives of the multiple stakeholders involved (Seddon et al., Citation2021). Further, the data presented in this study is cross-sectional, whereas longitudinal data could provide insights about how triadic caring relationships evolve over time. It is important to note that people working as SL carers may not be representative of the wider care workforce. Companions in this study needed to have a suitable home and living situation to join the service. To understand the transferability of this model of working it will be important to explore the sociodemographic details of SL carers in future research.

Recommendations for policy and practice

The interview findings illustrate how community-based day support can support wellbeing outcomes for PLWD, unpaid and paid carers suggesting that further investment in these forms of short breaks is merited. SL based short breaks appear a good fit with the international policy agenda for person-centred, relational care.

Commissioning short break models that support relational (and when appropriate and feasible) triadic caring relationships may help PLWD and unpaid carers achieve wellbeing outcomes. Such short breaks may also benefit the paid carers involved, and lead to wider community benefits: raising public awareness of dementia, challenging stigma, and promoting inclusivity.

Although longer-term outcomes were not discussed by respondents, it is known that if wellbeing needs are met, there is a reduced risk of unpaid carers reaching crisis point. This preventative approach can delay the need for more intensive support interventions, such as care home admission (Banerjee et al., Citation2003).

Reviewing commissioning models will be important as these forms of short break need consistent paid carers and time for undertaking matching processes. Different ways of working should be explored in short break services as companions found their relative autonomy facilitated triadic caring relationships. The interviews also highlighted how providers need to carefully consider these alternative ways of working. Mechanisms need to be in place to effectively support paid carers who are working more autonomously, to feel ‘safe’ in positive risk management and to help them reconcile the needs of relational care with the restrictions inherent in a paid role.

Conclusion

This research has highlighted triadic caring relationships as a pivotal mechanism in delivering wellbeing outcomes for PLWD, unpaid and paid carers through community-based short breaks. This challenges traditional notions about what helps unpaid carers derive wellbeing outcomes from short breaks, who short breaks involve, and where and how short breaks can be delivered. With increasing demand for unpaid carer short breaks, community-based options that foster and support triadic caring relationships may present a valuable addition to traditional respite services.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.2 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank our research partners PSS (UK) Ltd. and Shared Lives Plus. We also thank members of our Project Advisory Group for their feedback and support on interpreting the interview findings and informing this paper. We additionally extend thanks to the Southeast Wales Shared Lives scheme for helping us to find Project Advisory Group members.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allen, K., Malone-Lee, M., Preston, O., Smith, L., Hart, N., Mattu, A., & Redfearn, T. (2020). The fog of support. An inquiry into the provision of respite care and carers assessments for people affected by dementia. Alzheimer’s Society.

- Alzheimer’s Society. (2020b). Worst hit: Dementia during coronavirus. Alzheimer’s Society.

- Alzheimer’s Society. (2015). Dementia 2015: Aiming higher to transform lives. Alzheimer’s.

- Alzheimer’s Society. (2020a). Alzheimer’s Society Women’s unpaid dementia care and the impact on employment. London.

- Australian Government. (2019). Integrated carer support service model.

- Banerjee, S., Murray, J., Foley, B., Atkins, L., Schneider, J., & Mann, A. (2003). Predictors of institutionalisation in people with dementia. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 74(9), 1315–1316. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.74.9.1315

- Ben-Arie, A., & Iecovich, E. (2014). Factors explaining the job satisfaction of home care workers who left their older care recipients in Israel. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 33(4), 211–228.

- Bhatt, J., Comas Herrera, A., Amico, F., Farina, N., Wong, J., Orange, J. B., Gaber, S., Knapp, M., Salcher-Konrad, M., Stevens, M., & Australia, D. (2019). The World Alzheimer report 2019: Attitudes to dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International.

- Brookes, N., & Callaghan, L. (2013). What next for Shared Lives? Family-based support as a potential option for older people. Journal of Care Services Management, 7(3), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1179/1750168714Y.0000000029

- Brookes, N., Palmer, S., & Callaghan, L. (2016). I live with other people and not alone: A survey of the views and experiences of older people using Shared Lives (adult placement). Working with Older People, 20(3), 179–186. https://doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-03-2016-0005

- Callaghan, L., Brookes, N., & Palmer, S. (2017). Older people receiving family-based support in the community: A survey of quality of life among users of ‘Shared Lives’ in England. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(5), 1655–1666.

- Carers Trust. (2020). Caring for someone with dementia. A guide for family and friends who look after a person with dementia. Carers Trust.

- Carers UK. (2020). Unseen and undervalued. The value of unpaid care provided to date during the COVID-19 pandemic. Carers UK.

- Carers UK. (2021). State of caring. Carers UK.

- Clark, S., Prescott, T., & Murphy, G. (2019). The lived experiences of dementia in married couple relationships. Dementia (London, England), 18(5), 1727–1739. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217722034

- Clarke, C., & Mantle, R. (2016). Using risk management to promote person-centred dementia care. Nursing Standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain): 1987), 30(28), 41–46. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.30.28.41.s47

- Crouch, M., & McKenzie, H. (2006). The logic of small samples in interview-based qualitative research. Social Science Information, 45(4), 483–499. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018406069584

- de Bruin, S. R., Buist, Y., Hassink, J., & Vaandrager, L. (2019). I want to make myself useful’: The value of nature-based adult day services in urban areas for people with dementia and their family carers. Ageing & Society, 1–23.

- De Jonckheere, M., & Vaughn, L. M. (2019). Semi structured interviewing in primary care research: A balance of relationship and rigour. Family Medicine and Community Health, 7(2), e000057–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000057

- Dickins, M., Goeman, D., O’Keefe, F., Iliffe, S., & Pond, D. (2018). Understanding the conceptualisation of risk in the context of community dementia care. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 208, 72–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.05.018

- Edvardsson, D., Varrailhon, P., & Edvardsson, K. (2014). Promoting person-centeredness in long-term care: An exploratory study. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 40(4), 46–53.

- Fletcher, J. R. (2020). Renegotiating relationships: Theorising shared experiences of dementia within the dyadic career. Dementia (London, England), 19(3), 708–720. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301218785511

- Gale, N. K., Heath, G., Cameron, E., Rashid, S., & Redwood, S. (2013). Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(117), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-117

- Genoe, M., & Dupuis, S. (2011). I’m just like I always was: A phenomenological exploration of leisure, identity and dementia. Leisure/Loisir, 35(4), 423–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/14927713.2011.649111

- Greenwood, D., Loewenthal, D., & Rose, T. (2001). A relational approach to providing care for a person suffering from dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 36(4), 583–590. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.02011.x

- Hargittai, E., Piper, A. M., & Morris, M. R. (2019). From internet access to internet skills: Digital inequality among older adults. Universal Access in the Information Society, 18(4), 881–890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10209-018-0617-5

- Karner, T. X. (1998). Professional caring: Homecare workers as fictive kin. Journal of Aging Studies, 12(1), 69–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0890-4065(98)90021-4

- Kirk, R. S., & Kagan, J. (2015). A research agenda for respite care. Deliberations of an expert panel of researchers, advocates and funders. ARCH National Respite Network and Resource Centre.

- Kitwood, T. (1993). Towards a theory of dementia care: The interpersonal process. Ageing and Society, 13(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X00000647

- Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first. Open University Press.

- Koster, L., & Nies, H. (2022). It takes three to tango: An ethnography of triadic involvement of residents, families and nurses in long-term dementia care. Health Expectations, 25(1), 80–90. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13224

- Lindeza, P., Rodrigues, M., Costa, J., Guerreiro, M., & Rosa, M. M. (2020). Impact of dementia on informal care: A systematic review of family caregivers’ perceptions. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, bmjspcare-2020-002242. bmjspcare-2020-002242. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002242

- Manthorpe, J., Harris, J., Samsi, K., & Moriarty, J. (2017). Doing, being and becoming a valued care worker: User and family carer views. Ethics and Social Welfare, 11(1), 79–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/17496535.2016.1247904

- Masterson-Algar, P., Allen, M. C., Hyde, M., Keating, N., & Windle, G. (2022). Exploring the impact of Covid-19 on the care and quality of life of people with dementia and their carers: A scoping review. Dementia, 21(2), 648–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/14713012211053971

- Morgan, S. (1996). Helping relationships in mental health. Chapman & Hall.

- Morgan, S., & Williamson, T. (2014). How can ‘positive risk-taking’ help build dementia -friendly communities’. Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

- MRC. (2015). Process evaluation of complex interventions Developing and evaluating complex interventions. Medical Research Council. https://www.ukri.org/publications/process-evaluation-of-complex-interventions/

- Nicholls, J., Lawlor, E., Neitzert, E., & Goodspeed, T. (2012). A guide to social return on investment social value lab (2nd ed.). Matter & Co.

- Nolan, M. R., Davies, S., Brown, J., Keady, J., & Nolan, J. (2004). Beyond person-centred care: A new vision for gerontological nursing. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13(3a), 45–53.

- O’Shea, E., Timmons, S., & Irving, K. (2020). The perspectives of people with dementia on day and respite services: A qualitative interview study. Ageing and Society, 40(10), 2215–2237.

- O’Shea, E., Timmons, S., O’Shea, E., Fox, S., & Irving, K. (2019). Respite in Dementia: An Evolutionary Concept Analysis. Dementia (London, England), 18(4), 1446–1465. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217715325

- Person Shaped Support (PSS). (n.d.). Social impact report shared lives and TRIO. https://psspeople.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Impact-Report_Shared-Lives-and-TRIO.pdf

- Phillipson, L., Magee, C., & Jones, S. C. (2013). Why carers of people with dementia do not utilise out-of-home respite services. Health & Social Care in the Community, 21(4), 411–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12030

- Pickett, J., & Brayne, C. (2019). The scale and profile of global dementia research funding. The Lancet, 394(10212), 1888–1889. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32599-1

- Pollock, K., Wilkinson, S., Perry-Young, L., Turner, N., & Schneider, J. (2021). What do family caregivers want from domiciliary care for relatives living with dementia? A qualitative study. Ageing and Society, 41(9), 2060–2073. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X20000185

- Pope, C., Ziebland, S., & Mays, N. (2000). Analyzing qualitative data. BMJ, 320(7227), 114–116. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114

- Rahman, S., & Swaffer, K. (2018). Assets-based approaches and dementia-friendly communities. Dementia (London, England), 17(2), 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301217751533

- Rapaport, P., Burton, A., Leverton, M., Herat-Gunaratne, R., Beresford-Dent, J., Lord, K., Downs, M., Boex, S., Horsley, R., Giebel, C., & Cooper, C. (2020). I just keep thinking that I don’t want to rely on people. A qualitative study of how people living with dementia achieve and maintain independence at home: Stakeholder perspectives. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-019-1406-6

- Ritchie, J., & Spencer, L. (1994). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Bryman, A., & Burgess, R. G. (Eds.), Analysing qualitative data (pp. 173–194). Routledge.

- Ritchie, J., & Spencer, L. (2002). Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Huberman, A. M.& Miles, M. B. (Eds.), The qualitative researcher’s companion (pp. 305–329). Sage.

- Rochira, S. (2018). Rethinking respite for people affected by dementia. Older Peoples’ Commissioner Office. http://www.olderpeoplewales.com/en/reviews/respite.aspx

- Ruiz-Fernández, M. D., Hernández-Padilla, J. M., Ortiz-Amo, R., Fernández-Sola, C., Fernández-Medina, I. M., & Granero-Molina, J. (2019). Predictor factors of perceived health in family caregivers of people diagnosed with mild or moderate Alzheimer’s disease. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3762. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16193762

- Savla, J., Roberto, K. A., Blieszner, R., McCann, B. R., Hoyt, E., & Knight, A. L. (2021). Dementia caregiving during the “Stay-at-Home” phase of COVID-19 pandemic. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(4), e241–245. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa129

- Seddon, D., Miller, E., Prendergast, L., Williamson, D. & Cavaye, J.E. (2021). Making personalised short breaks meaningful: a future research agenda to connect academia, policy and practice. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 22(2), 81–94. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAOA-10-2020-0050

- Shared Care Scotland. (2017). Short breaks definition https://www.sharedcarescotland.org.uk/resources/briefings/short-breaks-definition/

- Shared Care Scotland. (2020). Promoting variety: Shaping markets and facilitating choice in short breaks, https://www.sharedcarescotland.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/SCS-Promoting-Variety-2020-WEB.pdf

- Shared Lives Plus. (2014). The state of Shared Lives in England. Shared Lives Plus.

- Shared Lives Plus. (2020). State of the nation: Shared lives in Wales. Shared Lives Plus.

- Sims-Gould, J., & Martin-Matthews, A. (2007). Themes in family caregiving: Implications for social work practice with older adults. British Journal of Social Work, 38(8), 1572–1587. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcm073

- Social Services Act. (2001). Sweden. https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_isn=60673

- Srivastava, A., & Thomson, S. B. (2009). Framework analysis: a qualitative methodology for applied policy research. Journal of Administration & Governance, 4(2), 72–79.

- Truskinovsky, Y., Finlay, J. M., & Kobayashi, L. C. (2022). Caregiving in a pandemic: COVID-19 and the well-being of family caregivers 55+ in the United States. Medical Care Research and Review: MCRR, 10775587211062405. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775587211062405

- Tuijt, R., Rees, J., Frost, R., Wilcock, J., Manthorpe, J., Rait, G., & Walters, K. (2021). Exploring how triads of people living with dementia, carers and health care professionals’ function in dementia health care: A systematic qualitative review and thematic synthesis. Dementia (London, England), 20(3), 1080–1104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301220915068

- Tulek, Z., Baykal, D., Erturk, S., Bilgic, B., Hanagasi, H., & Gurvit, I. H. (2020). Caregiver burden, quality of life and related factors in family caregivers of dementia patients in Turkey. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 41(8), 741–749. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2019.1705945

- Tulloch, K., McCaul, T., & Scott, T. L. (2022). Positive aspects of dementia caregiving during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clinical Gerontologist, 45(1), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2021.1929630

- Turner, N., Schneider, J., Pollock, K., Travers, C., Perry-Young, L., & Wilkinson, S. (2020). Going the extra mile’ for older people with dementia: Exploring the voluntary labour of homecare workers. Dementia (London, England), 19(7), 2220–2233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301218817616

- Van Bruggen, S., Gussekloo, J., Bode, C., Touwen, D. P., Engberts, D. P., & Blom, J. W. (2016). Problems experienced by informal caregivers with older care recipients with and without cognitive impairment. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 35(1), 11–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621424.2016.1145166

- Welsh Government. (2014). Social services and well-being (Wales) Act (2014). Welsh Government.

- Welsh Government. (2018). The Welsh Government Standards (no. 7) regulations 2018. Welsh Government.

- Welsh Government. (2020). The Health Protection (Coronavirus Restrictions) (No. 2) Regulations 2020. Welsh Government.

- Welsh Government. (2021). Strategy for unpaid carers. Welsh Government.

- Wengraf, T. (2004). The biographic-narrative interpretative method (BNIM) – Short guide., v. 22. Middlesex University and University of East London.

- Wengraf, T. (2008). Short guide to BNIM. University of East London.