Abstract

Objectives: People with intellectual disability, particularly people with Down syndrome, are at an increased risk for early-onset dementia, in comparison to people without an intellectual disability. The aim of this review was to scope the current landscape of post-diagnostic dementia supports for people with intellectual disability.

Method: A systematic search of five electronic databases (CINAHL, Medline, PsycArticles, PsycInfo and Web of Science) was conducted for this scoping review. Results were screened independently by two reviewers, with a third reviewer for arbitration where necessary.

Results: Forty-two studies met the inclusion criteria, and relevant information was extracted. The articles included focussed on the experiences of people with intellectual disability and dementia, as well as the role of carers, family members and staff. Key themes included ageing in place, environmental supports for people with intellectual disability and dementia, dementia-specific interventions and therapies, as well as the feasibility of these interventions. Besides the studies that focussed on these themes, other studies focussed on staff training and family supports.

Conclusion: This review highlights the importance of implementing timely and appropriate post-diagnostic supports for people living with intellectual disability and dementia. More controlled trials are required on post-diagnostic dementia supports for people with intellectual disability.

Introduction

As people with intellectual disability are living to an older age (McCarron, Swinburne, et al., Citation2011), it has become more apparent that they are at increased risk for early-onset dementia, in comparison to people without an intellectual disability (Strydom et al., Citation2009). In particular, people with Down syndrome have a genetic vulnerability to Alzheimer’s disease due to having three copies of chromosome 21, such that virtually everyone with Down syndrome will have the neuropathology of Alzheimer’s disease by the age of 40 (Lott & Head, Citation2019).

The disparity between predicted prevalence of dementia in comparison to the actual number of dementia diagnoses among people with intellectual disability has been widely reported (Dawson et al., Citation2015; McCarron & Lawlor, Citation2003), with the timeline between the initial emergence of symptoms and a formal diagnosis averaging 3 years across the UK (Chrisp et al., Citation2011) with similar findings in Ireland and in the US (Jokinen et al., Citation2013; McCarron et al., Citation2017) which has broad implications for the provision of resources and supports. Many people with intellectual disability may struggle to obtain a diagnosis from appropriate specialist services, and where such a diagnosis is received, those diagnosed with dementia are also likely to require additional specialist advice and post-diagnostic support (McCarron et al., Citation2018).

For people with intellectual disability, the process to diagnose dementia can be challenging, due to pre-existing intellectual impairment, communication difficulties, staff turnover and impairment with daily activities (McCarron et al., Citation2018). It is critical to measure a change as compared to prior functioning to support clinical observation of significant decline (Strydom & Hassiotis, Citation2003); a baseline measurement of cognitive function and functional independence prior to any onset of decline allows for a clearer quantification of any subsequent decline. The availability of specialist expertise and training to facilitate diagnosis is essential, and once a diagnosis is established, a plan of care is needed.

A timely diagnosis offers the person living with dementia, as well as their families, appropriate time to plan for the future and to access appropriate supports while playing an active role in their own care planning (Robinson et al., Citation2010; Zeilig, Citation2015). Furthermore, there is significant demand for appropriate and inclusive dementia diagnostic pathways for people with young onset dementia, people with intellectual disabilities and minority populations (Chapman et al., Citation2018; Goeman et al., Citation2016; Parveen et al., Citation2017).

Post-diagnostic support has been defined in different ways in general population dementia support services (Dodd et al., Citation2018). Our working definition of post-diagnostic dementia support is taken from Gibb et al. (Citation2019, p. 3): ‘enabling and assisting people with dementia and their families to live a life of their choosing throughout the continuum of dementia’. Post-diagnostic support is essential to support quality of life, well-being, inclusion and social connectedness. The scope of post-diagnostic support is largely dependent upon individual needs and the progression of dementia. In recent years, dementia care for the general population has focussed on maintaining the abilities and capabilities of the person living with dementia, rather than on skill deterioration or skill loss.

For the general population, post-diagnostic dementia supports have focussed on the facilitation of psychoeducational programmes for people with dementia and care partners. The Irish Dementia Working Group identified peer support, cognitive rehabilitation therapies, social contact, sharing of accessible information, and having a purpose as key areas for appropriate support after a dementia diagnosis (Gibb et al., Citation2019). Unhelpful supports were identified as inappropriate referrals and suggestions that one should attend a day centre or social club. Learning about dementia, legal and financial planning, information regarding local supports and services, communication, physical activity and nutrition, and environmental interventions were further identified as focal areas for support (Gibb et al., Citation2019). The Five Pillars Model of post-diagnostic support identifies its key pillars as: supporting community connections; peer support; planning for future care; understanding the illness and managing symptoms; and planning for future decision-making and was developed to provide people living with dementia, their families and carers with tools, connections, resources and plans (Simmons, Citation2011). In their clinical guidelines, Jokinen et al. (Citation2013) confirmed the need for similar approaches for people with intellectual disabilities and dementia, but there is a need for more work on building the evidence base of responsive post-diagnostic interventions in this population. A systematic review by MacDonald and Summers (Citation2020) did find that behavioural, systemic and therapeutic interventions were helpful for individuals with intellectual disability and dementia. Dodd et al. (Citation2018) have also highlighted the importance of understanding non-cognitive symptoms of dementia in providing post-diagnostic support to people with intellectual disability. In the development and delivery of psychosocial interventions that are both person-centred and fit for purpose, the perspectives of people with intellectual disability and dementia must be included.

Although some progress has been made in studying post-diagnostic dementia supports for people with intellectual disability, currently less is known about such supports in this cohort compared to the general population. The aim of the current scoping review was to systematically search the existing literature for research evidence on post-diagnostic dementia supports for people with intellectual disability.

Methods

The scoping review methodology is based on the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005), including the amendments proposed by Levac et al. (Citation2010). The Arksey and O’Malley framework consists of six stages:

Identifying the research question

Identifying relevant studies

Study selection

Charting the data

Collating, summarising and reporting results

Consultation.

The stages are discussed in more detail below.

Stage 1: Identifying the research question

The review addressed the following questions.

What post-diagnostic supports are currently available for people with intellectual disability and dementia, nationally and internationally?

What does the current research landscape of post-diagnostic dementia support services for people with intellectual disability look like, in terms of key areas of support under in vestigation?

Stage 2: Identifying relevant studies

An exploratory online search of five electronic databases (CINAHL, Medline, PsycAtricles, PsycInfo and Web of Science) was conducted during June and July 2021. This search identified articles, grey literature, preliminary studies, conference papers and reports related to the area of post-diagnostic dementia supports for people with intellectual disability. The search strategy may be found in the Appendix. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in .

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the review.

Stage 3: Study selection

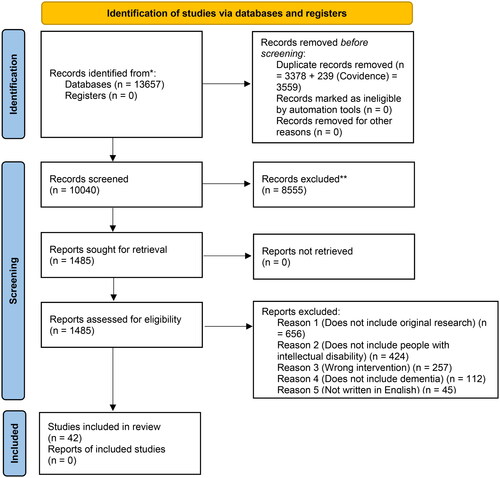

Duplicate studies from the different databases were excluded. The remaining studies were exported to Covidence, where study titles and abstracts were screened against the inclusion/exclusion criteria with reasons for exclusion identified and full texts obtained for included articles. Title and abstract screening, and full text screening, were performed by the same two independent reviewers. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. A total of 42 studies met our inclusion criteria and were included in the review. A flow diagram of study selection is presented in .

Figure 1. PRISMA flow diagram.

Source: Page et al. (Citation2021).

Stage 4: Charting the data

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers, using the data extraction template which was developed by both reviewers on Covidence. This reduced bias and ensured reliability while charting the data. Any discrepancies with data extraction were resolved by consensus. The extracted data is presented under the following headings: Author(s), year, title, location, aim(s), study design, setting, sampling, participant characteristics, inclusion and exclusion criteria, methodology and results.

Stage 5: Collating, summarising and reporting results

Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 report the preliminary findings which includes key data from the included studies. Supplementary Table 1 summarises key information from studies employing qualitative or mixed methods methodology, while Supplementary Table 2 summarises relevant information from quantitative studies. Potential gaps in the existing literature on post-diagnostic dementia supports for people with intellectual disability were identified, as were areas for further research. The first author devised a narrative summary of the findings of the literature under key themes (see Results section), which were agreed with the research team.

Table 2. Quality assessment of qualitative and mixed methods publications.

Stage 6: Consultation

The authors presented the findings of the review to an expert advisory panel, comprised of experts at a national and international level. The authors also prepared an accessible version of the scoping review methods and results. This was completed with a research assistant with intellectual disability, in order to ensure that this summary would be accessible.

Quality appraisal

As the identified research papers were most commonly either qualitative or mixed methods, we assessed the quality of these full research articles using the CASP instrument (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, Citation2022). Using an approach similar to Vandemeulebroucke et al. (Citation2018), two researchers independently assessed the full-text publications. The two researchers compared assessments after they had assessed five each until all research articles had been assessed (see ).

Results

A total of 10,040 article titles and abstracts were screened, with 8,555 articles excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Then 1,485 full text articles were screened with 42 articles identified as meeting the inclusion criteria (see ). The 42 articles focussed on (1) the challenges associated with ageing in place for people with intellectual disability living with dementia, (2) interventions/therapies, (3) staff supports and training, (4) the role of family, (5) environmental supports and (6) end of life care. Greater detail on the studies included is provided in Supplementary Table 1 (which provides information on the qualitative/mixed methods studies) and Supplementary Table 2 (which provides information on the quantitative studies).

Ageing in place

Ageing in place involves keeping people within their communities, in familiar surroundings, and close to family, friends, and long-term care staff for as long as possible (e.g. Dixon, Citation2007), and is well supported as an optimal approach to post-diagnostic support (e.g. McCarron et al., Citation2014). Research findings indicate that many people with intellectual disability who develop dementia experience changes or disruption to their accommodation, moving from independent or group homes to larger/more congregated/institutional residential settings (e.g. generic nursing homes), or a different location within their existing service, due to the absence of community-based care responding to progression of the condition (Cleary & Doody, Citation2017; Manji & Dunn, Citation2010; Sheth, Citation2019; Watchman, Citation2008). This is unfortunate, given evidence that, for example, group homes can not only adhere to the principles of dementia care (Janicki et al., Citation2005) but can also provide conditions associated with better quality of life and, additionally, operate with lower staffing costs due to the non-utilization of medical staff (Chaput, Citation2003). Agencies can also adapt their existing services to provide dementia capable housing in the community (Janicki et al., Citation2003).

The negative implications associated with such disruption are evidenced by a lack of facilitation for ageing in place and a lack of consideration for the person’s wishes and interests (Cleary & Doody, Citation2017; Iacono et al., Citation2014). A retrospective study found that adults with Down syndrome experience more relocations than adults across the general populations, and are also more likely to receive end of life care in a nursing home (Patti et al., Citation2010). Effective ageing in place is reported to require appropriate environmental supports, as well as staff training embedded in person-centred dementia care (Cleary & Doody, Citation2017). A 5-year pilot programme provided collaborative support services for people with intellectual disability living with dementia (Dixon, Citation2007). The programme was structured around the ‘ageing in place’ model, and promoted independence and improvement of quality of life. As a result of the pilot programme, over 30% of participants showed improvements in activities of daily living, but there is no data on ageing in place (Dixon, Citation2007).

The research thus demonstrates that, despite evident benefits of post-diagnostic supports that support ageing in place, there are substantial challenges in realising this goal, and many people with intellectual disability and dementia will not experience ageing in place.

Interventions/therapies

Existing knowledge regarding the effectiveness and feasibility of interventions has been informed by reports from workers and practitioners as well as researchers (Dodd et al., Citation2015). Positive effects have previously been reported for cognitive stimulation therapy (in a mixed methods study by Ali et al., Citation2022), music therapy (in a qualitative study by Bevins et al., Citation2015), life stories (in case series by Crook et al., Citation2016) and dementia care mapping (in qualitative research by Finnamore & Lord, Citation2007; Jaycock et al., Citation2006; Schaap, Dijkstra, et al., 2018; Schaap, Fokkens, et al., 2018; and mixed methods research by Schaap et al., Citation2021).

Watchman et al. (Citation2021) used individualised goal-setting theory to identify the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions in social care settings. This participatory action study also explored the use of photovoice methodology. Findings reported the overall effects of the interventions as 80% in cycle one and 81% in cycle two, which demonstrated a positive ‘in the moment’ effect. In cycle 1, 32% of goals were either met and 43% exceeded expectations. In cycle 2, 35% of goals were met and 37% exceeded expectations (Watchman et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, the adapted photovoice methodology facilitated a developing discourse around dementia (Watchman et al., Citation2021). Findings from a randomised controlled trial by De Vreese et al. (Citation2012) reported that enrolment in a dementia-capable programme, which facilitated daily practice of residents’ residual skills and abilities, contributed to activity and skill maintenance.

When considering access to activities, people with Down syndrome identified choice, agency, and schedules and routines as important factors in supporting participation in paid employment, physical activity, leisure, music, home management, shopping, religious practices, community outings, and participation in holidays and celebrations with family and friends (Sheth, Citation2019).

In terms of guidance that can be used in informing the development of supports, the International Summit on Intellectual Disability and Dementia offered a seven key area working model of post-diagnostic support for intellectual disability settings: post-diagnostic counselling, psychological and medical surveillance, periodic reviews and adjustments to care plans, early identification of non-cognitive symptoms, review of care practices and supports, staff training and supports, as well as evaluation of quality of life for the individual (Dodd et al., Citation2018). The summit also identified dementia care mapping as an effective tool for evaluating quality of life and quality of care of people with intellectual disability and dementia.

Overall, there are many different interventions that can be employed with people with intellectual disability and dementia, and although these often require adaptation compared to general population approaches, such modifications need not always be extensive. There has been some initial RCT-based research in this area (Ali et al., Citation2022), although most research has employed qualitative or mixed-methods methodologies.

Staff supports and training

Research which explored outcomes for individuals with dementia and intellectual disability, largely tended to assess outcomes from the perspective of staff, rather than including the voice of the individual (see qualitative studies by Chapman et al., Citation2018; Cleary & Doody, Citation2017; Herron et al., Citation2020; Iacono et al., Citation2014; McLaughlin & Jones, Citation2010; Perera & Standen, Citation2014; and case series by Wilkinson et al., Citation2005). Indeed, a number of studies have been more focussed on staff/carer burden (McCallion, Nickle, et al., Citation2005; McCallion, McCarron, et al., Citation2005) and time spent caregiving (McCarron et al., Citation2002).

Staff training and supports to carers and staff, made available throughout specialist and mainstream services, are reported as central to ensuring appropriate care and support. However, qualitative findings indicate that carers and staff may not necessarily have access to specific education or training in the provision of appropriate care for individuals with a diagnosis of dementia and intellectual disability (Fahey-McCarthy et al., 2009; Herron et al., Citation2020).

Other findings confirm that it is critical that staff are educated on the different stages of dementia, and the outcomes to be achieved for the person (see qualitative research by Davies et al., Citation2002; Furniss et al., Citation2012; McKenzie et al., Citation2020). Sheth (Citation2019) highlighted the importance of training that supports the development of skills in accessible communication, meaningful one-on-one interactions and adjusting to changing care needs. Lifshitz and Klein (Citation2011) offered a case report on the use of Mediational Intervention for Sensitizing Caregivers, although they suggested more research is needed.

Herron et al. (Citation2020) emphasized the importance of understanding dementia and intellectual disability in providing appropriate support to the person living with dementia as well as early identification of non-cognitive symptoms of dementia. Non-cognitive symptoms can include agitation, anxiety, disinhibition, as well as sleep and appetite changes, and increased awareness and understanding of these symptoms may enhance the quality of care provided to the individual (Dodd et al., Citation2018).

In summary, although the current research on staff supports and training indicates a need for specialist training on post-diagnostic dementia supports for people with intellectual disability, staff may not have such resources easily available to them, or perhaps may not know where to find such resources.

The role of the family

There are qualitative findings within the literature that there is a need to develop long-term services and supports as well as educational resources which accommodate family carers, including siblings (Coyle et al., Citation2014). A particular target in interventions is the reduction of caregiver burden (Perera & Standen, Citation2014); decreasing caregiver burden will not only benefit caregivers themselves but also contribute to increased quality of life among those receiving care. Perera and Standen outline ‘strategy toolboxes’ that carers use for reducing stress and supporting people with intellectual disability and dementia. Perera and Standen raise concerns that some family carers respond from a sense of obligation to become a carer, and their burden interacts with traditional, religious and cultural expectations.

A case series by Carling-Jenkins et al. (Citation2012) reported that families experience stress and confusion as they negotiate care pathways and services. They reported that these pathways and services were poorly equipped to meet their needs, and that professionals were more focussed on longstanding disability than the recent diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. McCarron, McCallion, et al. (Citation2011) reported qualitative findings that even though family members may have a limited relationship with the person living with dementia and may not necessarily understand their needs and wishes, they are still likely to be asked to make end of life and other decisions on behalf of the individual with dementia.

In summary, family members, like staff carers, require guidance or training in this specialist area of support. Family members may be particularly vulnerable to carer stress and burden, and any model of post-diagnostic support needs to address this.

Environmental supports

Clinical guidelines have indicated that an important consideration for people with dementia and intellectual disability is their safety from falls or injuries. Dementia inclusive design may result in decreases in falls and stress, and may lead to a reduction in the use of anti-psychotics and need for sedation (Jokinen et al., Citation2013). Other environmental supports identified included access to adaptive equipment, considerations for lighting, visual cues and auditory stimulation (Jokinen et al., Citation2013). Findings from Sheth (Citation2019) identified physical accessibility as a specific challenge, especially as individual mobility needs change.

Hawkes et al. (Citation2019) sought to identify areas of improvement regarding person-centred care, staff interactions, and the environment utilising the Person, Interaction and Environment (PIE) programme, which is a tool for enriching and strengthening person-centred care for teams who work with people living with dementia. Findings from their mixed-method study indicated that the PIE programme is an ongoing process and is a means of embedding an engagement-orientated culture of care in residential settings. In a cross-sectional study, Raj et al. (Citation2020) identified the home environment and activities of daily living as areas frequently assessed by occupational therapists for people with intellectual disability living with dementia. Common interventions included compensatory strategies and environmental modifications. However, it was reported that this was less likely to occur for informal caregivers, for whom management of manual handling was more likely targeted.

The research on post-diagnostic environmental supports for people with intellectual disability and dementia has placed an emphasis on personal safety and avoiding falls. The person and their interaction with the environment has been considered, but approaches may differ between staff and family caregivers.

End-of-life/palliative care

Dementia is a life-limiting condition, and end-of-life and palliative care are an integral part of the overall picture of post-diagnostic dementia support. Issues surrounding increased relocation for people with intellectual disability and dementia throughout end-of-life and palliative care as well as the need for the individual to be more involved in planning for their own end of-life care were highlighted in the findings of a retrospective study (Patti et al., Citation2010) and qualitative research (Watchman, Citation2005). Key elements of end-of-life and palliative care identified included collaboration of specialist services and co-ordination of care, pain and symptom management, and supporting the person through death (McCarron, McCallion, et al., Citation2011).

A lack of equity of access for people with intellectual disability and advanced dementia to palliative and end-of-life care is a major concern (Tuffrey-Wijne et al., Citation2016), but is unlikely to be remedied without recognition of differing communication needs and alertness to signs of end of life/dying, support for family members, peers and carers, and including them in symptom management as well as education and training, and hospice care with a focus on comfort and quality of life (McCallion et al., Citation2017). A further area of concern is evidence from an audit study that found a lack of documented evidence for arrangement for the death of people with intellectual disability and dementia (Tromans et al., Citation2019).

In conclusion, ageing in place is likely to be more challenging during palliative and end-of-life care. Broader coordination between services and greater training and education are required to deliver a higher standard of post-diagnostic dementia support to people with intellectual disability up until death.

Quality assessment

The quality of the studies, as appraised using the CASP criteria, is summarised in . Quality was generally categorised as moderate to high. The criterion from the CASP which the most studies were not found to fulfil was a critical appraisal of the role of the researcher, and their relationship with the participant, in the research process.

Discussion

Post-diagnostic dementia supports incorporate many different elements, and are integral for maintaining the quality of life of people with intellectual disability and dementia. It is evident that any approach to providing post-diagnostic dementia supports for people with intellectual disability needs to be adaptable to both the stage of dementia and the changing needs of the person, including end-of-life care. It is particularly important that a wide range of interventions and approaches be utilised (Dodd et al., Citation2018). Although most of the studies identified in this review were either qualitative or mixed methods (see Supplementary Table 1), there have been some studies employing a more quantitative approach (see Supplementary Table 2).

Literature regarding the efficacy of interventions for people with intellectual disability and dementia is limited, and approaches adopted within the general population are typically similar to those adopted for people with intellectual disability. However, for people with intellectual disability, post-diagnostic supports provided are usually linked to existing service providers, with supports adapted to dementia-specific needs (Dodd et al., Citation2018). One such support, cited by Dodd et al. (Citation2018), is post-diagnostic counselling, involving the provision of support and education for the individual, as well as carers, families or staff, which aims to provide the person and their carers with skills to deal with a dementia diagnosis, and to understand the implications of a diagnosis and the trajectory of the condition, in ways which promote the well-being of the individual. Nevertheless, most interventions noted are targeted at staff, while few interventions are reported for use either by families supporting individuals with intellectual disabilities and dementia, or by people with intellectual disabilities themselves, who are able and interested in being partners in their care.

There are many challenges associated with the delivery of person-centred dementia care, and person-centred approaches are not always accessible for people with intellectual disability as dementia presents and worsens (Cleary & Doody, Citation2017). Carers can feel unprepared to provide person-centred dementia support across the stages of dementia without dementia-specific training (McCarron, McCallion, Fahey-McCarthy, Connaire, & Dunn-Lane, Citation2010), often leading to reactive, rather than planned care (Iacono et al., Citation2014). Interventions consequently need to more comprehensively address all of the partners in care, and that may also include peers with intellectual disabilities.

It is well supported that ageing in place is optimal (Jokinen et al., Citation2013; McCarron et al., Citation2014); however, services and family homes are not always dementia capable and do not have the appropriate resources to prolong ageing in place of people with intellectual disability who are living with dementia (Dunne et al., Citation2014; Janicki, Citation2006). How ageing in place can be resourced and supported and the specific services and supports needed to ensure ageing in place both in services and in family situations needs further investigation (Jokinen et al., Citation2013; McCallion et al., Citation2017).

There were some potential limitations to this review. We did not complete a meta-analysis on previous data. However, the research was predominantly qualitative in nature, and the quantitative research was quite heterogenous in terms of outcomes and assessments. Family support was an important point arising in the literature, and including ‘family support’ as a specific search term would have been best, although family supports were captured in the articles identified in our literature search.

As people with intellectual disability age, with high risk of dementia at an earlier age for people with Down syndrome in particular, it is urgent that families, services and communities plan ahead for how to support those who will be living with dementia. The absence of agreed guidelines, demonstrated programmes and a willingness to resource supports must all be addressed. Future research in this area should do more to address implementation issues for post-diagnostic supports, and employ approaches such as more controlled trials to evaluate the efficacy of interventions. Using the same outcome measures more consistently across different trials will also help to further the progress of the field. Furthermore, although a number of articles did include participants with intellectual disability and dementia, this is something that should be explored in more depth in future work; it has been noted that delivering person-centred support requires that care staff have a good understanding of what it means for an individual with an intellectual disability to have dementia (e.g. Dodd et al., Citation2015).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ali, A., Brown, E., Tsang, W., Spector, A., Aguirre, E., Hoare, S., & Hassiotis, A. (2022). Individual cognitive stimulation therapy (iCST) for people with intellectual disability and dementia: A feasibility randomised controlled trial. Aging & Mental Health, 26(4), 698–708. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1869180

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Bevins, S., Dawes, S., Kenshole, A., & Gaussen, K. (2015). Staff views of a music therapy group for people with intellectual disabilities and dementia: A pilot study. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 9(1), 40–48. https://doi.org/10.1108/AMHID-04-2014-0005

- Carling-Jenkins, R., Torr, J., Iacono, T., & Bigby, C. (2012). Experiences of supporting people with Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease in aged care and family environments. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 37(1), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2011.645473

- Chapman, M., Lacey, H., & Jervis, N. (2018). Improving services for people with learning disabilities and dementia: Findings from a service evaluation exploring the perspectives of health and social care professionals. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 46(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/bld.12210

- Chaput, J. L. (2003). Adults with Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease: Comparison of services received in group homes and in special care units. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 38(1–2), 197–211. https://doi.org/10.1300/J083v38n01_05

- Chrisp, T. A., Thomas, B. D., Goddard, W. A., & Owens, A. (2011). Dementia timeline: Journeys, delays and decisions on the pathway to an early diagnosis. Dementia, 10(4), 555–570. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301211409375

- Cleary, J., & Doody, O. (2017). Nurses’ experience of caring for people with intellectual disability and dementia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(5–6), 620–631. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13431

- Coyle, C. E., Kramer, J., & Mutchler, J. E. (2014). Aging together: Sibling carers of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 11(4), 302–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12094

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2022, July 03). CASP qualitative checklist. https://casp-uk.b-cdn.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf

- Crook, N., Adams, M., Shorten, N., & Langdon, P. E. (2016). Does the well-being of individuals with Down syndrome and dementia improve when using life story books and rummage boxes? A randomized single case series experiment. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 29(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12151

- Davies, M., McGlade, A., & Bickerstaff, D. (2002). A needs assessment of people in the Eastern Health and Social Services Board (Northern Ireland) with intellectual disability and dementia. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 6(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/146900470200600102

- Dawson, A., Bowes, A., Kelly, F., Velzke, K., & Ward, R. (2015). Evidence of what works to support and sustain care at home for people with dementia: A literature review with a systematic approach. BMC Geriatrics, 15(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-015-0053-9

- De Vreese, L. P., Mantesso, U., De Bastiani, E., Weger, E., Marangoni, A. C., & Gomiero, T. (2012). Impact of dementia-derived nonpharmacological intervention procedures on cognition and behavior in older adults with intellectual disabilities: A 3-year follow-up study. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 9(2), 92–102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2012.00344.x

- Dixon, B. K. (2007). AD program enriches life despite disabilities. Caring for the Ages, 8(12), 11–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1526-4114(07)60292-3

- Dodd, K., Bush, A., & Livesey, A. (2015). Developing and piloting the QOMID–Quality outcome measure for individuals with intellectual disabilities and dementia. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 9(6), 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1108/AMHID-12-2014-0041

- Dodd, K., Watchman, K., Janicki, M. P., Coppus, A., Gaertner, C., Fortea, J., Santos, F. H., Keller, S. M., & Strydom, A. (2018). Consensus statement of the international summit on intellectual disability and dementia related to post-diagnostic support. Aging & Mental Health, 22(11), 1406–1415. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1373065

- Dodd, K. D. (2015). Care considerations for dementia in people with Down’s syndrome: A management perspective. Neurodegenerative Disease Management, 5(4), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.2217/nmt.15.28

- Dunne, P., Reilly, E., & McCarron, M. (2014). When ageing in place is no longer viable: Transitions to a higher support home for persons with an intellectual disability and dementia. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(4), 370.

- Fahey-McCarthy, E., McCarron, M., Connaire, K., & McCallion, P. (2009). Developing an education intervention for staff supporting persons with an intellectual disability and advanced dementia. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 6(4), 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2009.00231.x

- Finnamore, T., & Lord, S. (2007). The use of dementia care mapping in people with a learning disability and dementia. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 11(2), 157–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629507076929

- Forbat, L., & Wilkinson, H. (2008). Where should people with dementia live? Using the views of service users to inform models of care. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 36(1), 6–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2007.00473.x

- Furniss, K. A., Loverseed, A., Lippold, T., & Dodd, K. (2012). The views of people who care for adults with Down’s syndrome and dementia: A service evaluation. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 40(4), 318–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2011.00714.x

- Gibb, M., O’Caheny, D., Craig, C., & Begley, E. (2019). 198 The next steps: The development of dementia post-diagnostic psychoeducational support guidance. Age & Ageing, 48, 17–65. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afz103.117

- Goeman, D., King, J., & Koch, S. (2016). Development of a model of dementia support and pathway for culturally and linguistically diverse communities using co-creation and participatory action research. BMJ Open, 6(12), e013064. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013064

- Hawkes, T., Luff, T., & Gee, S. B. (2019). Supporting person-centred dementia care for people with intellectual disabilities using the person, interaction, environment programme. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 66(1), 12–18.

- Herron, D. L., Priest, H. M., & Read, S. (2020). Supporting people with an intellectual disability and dementia: A constructivist grounded theory study exploring care providers’ views and experiences in the UK. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(6), 1405–1417. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12768

- Iacono, T., Bigby, C., Carling-Jenkins, R., & Torr, J. (2014). Taking each day as it comes: Staff experiences of supporting people with Down syndrome and Alzheimer’s disease in group homes. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 58(6), 521–533. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12048

- Janicki, M. (2006). Exploring dementia-related community care for adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 19(3), 251.

- Janicki, M. P., Dalton, A. J., McCallion, P., Baxley, D. D., & Zendell, A. (2005). Group home care for adults with intellectual disabilities and Alzheimer’s disease. Dementia, 4(3), 361–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301205055028

- Janicki, M. P., McCallion, P., & Dalton, A. J. (2003). Dementia-related care decision-making in group homes for persons with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 38(1–2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1300/J083v38n01_04

- Jaycock, S., Persaud, M., & Johnson, R. (2006). The effectiveness of dementia care mapping in intellectual disability residential services: A follow-up study. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 10(4), 365–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629506072870

- Jokinen, N., Janicki, M., P., Keller, S., McCallion, P., & Force, L. T.; National Task Group on Intellectual Disabilities and Dementia Practices. (2013). Guidelines for structuring community care and supports for people with intellectual disabilities affected by dementia. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 10(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12016

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69–69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Lifshitz, H., & Klein, P. S. (2011). Mediation between staff and elderly persons with intellectual disability with Alzheimer disease as a means of enhancing their daily functioning. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 46(1), 106–115.

- Lott, I. T., & Head, E. (2019). Dementia in Down syndrome: Unique insights for Alzheimer disease research. Nature Reviews Neurology, 15(3), 135–147. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-018-0132-6

- MacDonald, S., & Summers, S. J. (2020). Psychosocial interventions for people with intellectual disabilities and dementia: A systematic review. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 33(5), 839–855. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12722

- Manji, S., & Dunn, P. (2010). Supported empowerment for individuals with developmental disabilities and dementia. Journal on Developmental Disabilities, 16(1), 44–52.

- McCallion, P., Hogan, M., Santos, F. H., McCarron, M., Service, K., Stemp, S., Keller, S., Fortea, J., Bishop, K., Watchman, K., & Janicki, M. P. (2017). Consensus statement of the international summit on intellectual disability and dementia related to end-of-life care in advanced dementia. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 30(6), 1160–1164. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12349

- McCallion, P., McCarron, M., & Force, L. T. (2005). A measure of subjective burden for dementia care: The Caregiving Difficulty Scale – Intellectual Disability. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 49(Pt 5), 365–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2005.00670.x

- McCallion, P., Nickle, T., & McCarron, M. (2005). A comparison of reports of caregiver burden between foster family care providers and staff caregivers in other settings: A pilot study. Dementia, 4(3), 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301205055034

- McCarron, M., Gill, M., Lawlor, B., & Begley, C. (2002). Time spent caregiving for persons with the dual disability of Down’s syndrome and Alzheimer’s dementia: Preliminary findings. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 6(3), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469004702006003036

- McCarron, M., & Lawlor, B. A. (2003). Responding to the challenges of ageing and dementia in intellectual disability in Ireland. Aging & Mental Health, 7(6), 413–417. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860310001594655

- McCarron, M., McCallion, P., Coppus, A., Fortea, J., Stemp, S., Janicki, M., & Watchman, K. (2018). Supporting advanced dementia in people with Down syndrome and other intellectual disability: Consensus statement of the International Summit on Intellectual Disability and Dementia. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 62(7), 617–624. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12500

- McCarron, M., McCallion, P., Fahey-McCarthy, E., & Connaire, K. (2010). Staff perceptions of essential prerequisites underpinning end-of-life care for persons with intellectual disability and advanced dementia. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 7(2), 143–152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2010.00257.x

- McCarron, M., McCallion, P., Fahey-McCarthy, E., & Connaire, K. (2011). The role and timing of palliative care in supporting persons with intellectual disability and advanced dementia. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 24(3), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2010.00592.x

- McCarron, M., McCallion, P., Fahey-McCarthy, E., Connaire, K., & Dunn-Lane, J. (2010). Supporting persons with Down syndrome and advanced dementia: Challenges and care concerns. Dementia, 9(2), 285–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301209354025

- McCarron, M., McCallion, P., Reilly, E., Dunne, P., Carroll, R., & Mulryan, N. (2017). A prospective 20-year longitudinal follow-up of dementia in persons with Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 61(9), 843–852. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12390

- McCarron, M., McCallion, P., Reilly, E., & Mulryan, N. (2014). Responding to the challenges of service development to address dementia needs for people with an intellectual disability and their caregivers. In K. Watchman (Ed.), Intellectual disability and dementia: Research into practice (pp. 241–269). Jessica Kingsley.

- McCarron, M., Swinburne, J., Burke, E., McGlinchey, E., Mulryan, N., Andrews, V., & McCallion, P. (2011). Growing older with an intellectual disability in Ireland 2011: Results from the intellectual disability supplement of the Irish longitudinal study on ageing. School of Nursing and Midwifery.

- McKenzie, K., Metcalfe, D., Michie, A., & Murray, G. (2020). Service provision in Scotland for people with an intellectual disability who have, or are at risk of developing, dementia. Dementia (London, England), 19(3), 736–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301218785795

- McLaughlin, K., & Jones, D. A. (2010). ‘It’s all changed’: Carers’ experiences of caring for adults who have Down’s syndrome and dementia. British Journal of Learning Disabilities, 39(1), 57–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3156.2010.00618.x

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 372, 71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Parveen, S., Peltier, C., & Oyebode, J. R. (2017). Perceptions of dementia and use of services in minority ethnic communities: A scoping exercise. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(2), 734–742. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12363

- Patti, P., Amble, K., & Flory, M. (2010). Placement, relocation and end of life issues in aging adults with and without Down’s syndrome: A retrospective study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 54(6), 538–546. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2788.2010.01279.x

- Perera, B. D., & Standen, P. J. (2014). Exploring coping strategies of carers looking after people with intellectual disabilities and dementia. Advances in Mental Health and Intellectual Disabilities, 8(5), 292–301. https://doi.org/10.1108/AMHID-05-2013-0034

- Raj, S., Stanley, M., Mackintosh, S., & Fryer, C. (2020). Scope of occupational therapy practice for adults with both Down syndrome and dementia: A cross-sectional survey. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 67(3), 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12645

- Robinson, L., Iliffe, S., Brayne, C., Goodman, C., Rait, G., Manthorpe, J., Ashley, P., & Moniz-Cook, E. & DeNDRoN Primary Care Clinical Studies Group. (2010). Primary care and dementia: 2. Long-term care at home: Psychosocial interventions, information provision, carer support and case management. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 25(7), 657–664. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.2405

- Schaap, F. D., Dijkstra, G. J., Finnema, E. J., & Reijneveld, S. A. (2018). The first use of dementia care mapping in the care for older people with intellectual disability: A process analysis according to the RE-AIM framework. Aging & Mental Health, 22(7), 912–919. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1401582

- Schaap, F. D., Dijkstra, G. J., Reijneveld, S. A., & Finnema, E. J. (2021). Use of dementia care mapping in the care for older people with intellectual disabilities: A mixed-method study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 34(1), 149–163. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12794

- Schaap, F. D., Fokkens, A. S., Dijkstra, G. J., Reijneveld, S. A., & Finnema, E. J. (2018). Dementia care mapping to support staff in the care of people with intellectual disability and dementia: A feasibility study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 31(6), 1071–1082. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12464

- Sheth, A. J. (2019). Intellectual disability and dementia: Perspectives on environmental influences. Quality in Ageing and Older Adults, 20(4), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1108/QAOA-11-2018-0060

- Simmons, H. (2011). Getting post-diagnostic support right for people with dementia. Alzheimer Scotland. https://www.alzscot.org/sites/default/files/2019-07/110716_-_Updated_Getting_PDS_Right.pdf

- Strydom, A., & Hassiotis, A. (2003). Diagnostic instruments for dementia in older people with intellectual disability in clinical practice. Aging & Mental Health, 7(6), 431–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607860310001594682

- Strydom, A., Hassiotis, A., King, M., & Livingston, G. (2009). The relationship of dementia prevalence in older adults with intellectual disability (ID) to age and severity of ID. Psychological Medicine, 39(1), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291708003334

- Tromans, S., Andrews, H., Wani, A., & Ganghadaran, S. (2019). The ELCIDD project: An audit of end-of-life care in persons with intellectual disabilities and dementia. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 16(1), 88–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12286

- Tuffrey-Wijne, I., Wicki, M., Heslop, P., McCarron, M., Todd, S., Oliver, D., de Veer, A., Ahlström, G., Schäper, S., Hynes, G., O'Farrell, J., Adler, J., Riese, F., & Curfs, L. (2016). Developing research priorities for palliative care of people with intellectual disabilities in Europe: A consultation process using nominal group technique. BMC Palliative Care, 15(1), 36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0108-5.

- Vandemeulebroucke, T., de Casterlé, B. D., & Gastmans, C. (2018). How do older adults experience and perceive socially assistive robots in aged care: A systematic review of qualitative evidence. Aging & Mental Health, 22(2), 149–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2017.1286455

- Watchman, K. (2005). Practitioner-raised issues and end-of-life care for adults with Down syndrome and dementia. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 2(2), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2005.00026.x

- Watchman, K. (2008). Changes in accommodation experienced by people with Down syndrome and dementia in the first five years after diagnosis. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 5(1), 65–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2007.00140.x

- Watchman, K., Mattheys, K., McKernon, M., Strachan, H., Andreis, F., & Murdoch, J. (2021). A person-centred approach to implementation of psychosocial interventions with people who have an intellectual disability and dementia: A participatory action study. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 34(1), 164–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/jar.12795

- Wilkinson, H., Kerr, D., & Cunningham, C. (2005). Equipping staff to support people with an intellectual disability and dementia in care home settings. Dementia, 4(3), 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301205055029

- Zeilig, H. (2015). What do we mean when we talk about dementia? Exploring cultural representations of “dementia”. Working with Older People, 19(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/WWOP-10-2014-0032

Appendix

Search strategy

Concept 1: Disability

Medline: (MH "Intellectual Disability+") OR (MH "Learning Disabilities+") OR (MH "Disabled Persons+") OR (MH "Developmental Disabilities")

CINAHL: (MH "Intellectual Disability+") OR (MH "Attitude to Disability") OR (MH "Nurses, Disabled") OR (MH "Developmental Disabilities") OR (MH "Disability Management") OR (MH "Health Services for Persons with Disabilities") OR (MH "Severity of Disability")

PsycArticles: disability

PsycInfo: disability

Web of Science: No index terms in this database, searches run on title and topic

Keywords:

Medline or CINAHL: “intellectual disabilit*” OR “developmental disabilit*” OR “learning disabilit*” OR “disabled person*” OR “disabled patient*” OR “assessment disabilit*” OR “chronic disabilit*” OR “disability* assessment” OR “disabilit* evaluation” OR “disablement” OR “disablement evaluation” OR “evaluation disability*” OR “handicap”

Concept 2: Dementia

Medline: (MH "Dementia+") OR (MH "Frontotemporal Dementia+") OR (MH "Dementia, Vascular+") OR (MH "Dementia, Multi-Infarct") OR (MH "Alzheimer Disease") OR (MH "Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis") OR (MH "Lewy Body Disease") OR (MH "Prion Diseases+") OR (MH "Nootropic Agents")

CINAHL: (MH "Dementia+") OR (MH "Frontotemporal Dementia+") OR (MH "Dementia, Vascular+") OR (MH "Delirium, Dementia, Amnestic, Cognitive Disorders+") OR (MH "Dementia, Multi-Infarct") OR (MH "Lewy Body Disease") OR (MH "Dementia, Senile+") OR (MH "Dementia, Presenile+") OR (MH "Dementia Patients")

PsycArticles: dementia

PsycInfo: dementia

Web of Science: No index terms in this database, searches run on title and topic

Keywords:

Medline or CINAHL: “dementia” OR “Alzheimer*” OR “cognitive decline” OR “brain health” OR “amentia” OR “demention”

Concept 3: Support

Medline: (MH "Social Support+") OR (MH "Training Support") OR (MH "Financial Support+") OR (MH "Nutritional Support+") OR (MH "Psychosocial Support Systems") OR (MH "Decision Support Techniques+") OR (MH "Life Support Systems") OR (MH "Health Planning Support") OR (MH "Research Support as Topic") OR (MH "Life Support Care+")

CINAHL: (MH "Support, Psychosocial+") OR (MH "Nutritional Support Team") OR (MH "Home Nutritional Support") OR (MH "Decision Support Techniques+") OR (MH "Nutritional Support+") OR (MH "Training Support, Financial") OR (MH "Support Groups") OR (MH "Emotional Support (Saba CCC)") OR (MH "Coping Support (Saba CCC)")

PsycArticles: support

PsycInfo: support

Web of Science: No index terms in this database, searches run on title and topic

Keywords:

Medline or CINAHL: “support*” OR “post-diagnostic support*” OR “memory clinic” OR “therap*” OR “respite” OR “companion” OR “support” OR “support group*” OR “day program*” OR “mental health” OR “dementia practice coorindat*” OR “community” OR “planning” OR “dementia care” “cognitive stimulation” OR “environmental stimulation” OR “behavioral symptom*” OR “psychological symptom*”