?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objectives

Older adults contribute vast amounts of care to society, yet it remains unclear how unpaid productive activities relate to loneliness. The objective of this systematic review is to synthesise the evidence for associations between midlife and older people’s unpaid productive activities (i.e., spousal and grandparental caregiving, volunteering) and loneliness.

Methods

Peer-reviewed observational articles that investigated the association between loneliness and caregiving or volunteering in later life (>50 years) were searched on electronic databases (Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, PsychInfo and Global Health) from inception until July 2021. Studies were analysed using narrative synthesis and assessed for methodological quality applying the Newcastle Ottawa Scale.

Results

A total of 28 articles from 21 countries with 191,652 participants were included (52.5% women). Results were separately discussed for the type of unpaid productive activity, namely, general caregiving (N = 10), spousal caregiving (N = 7), grandparental caregiving (N = 7), and volunteering (N = 6). Risk of bias assessments revealed a moderate to high quality of included studies. Loneliness was positively associated with spousal caregiving but negatively associated with caregiving to grandchildren and volunteering.

Conclusions

Grandparental caregiving and volunteering may be promising avenues for reducing loneliness in older age. Future studies will need to distinguish between different types of caregiving and volunteering and explore more complex longitudinal designs with diverse samples to investigate causal relationships with loneliness.

KEY-POINTS

Spousal caregiving is associated with more loneliness

Grandparental caregiving and volunteering are associated with less loneliness

There is a lack of longitudinal evidence from lower- and middle-income countries

With advanced age and the realisation that life will not continue for unlimited time, people set a new focus on meaningful social relationships and activity engagement (Carstensen, Citation1993, Citation2006). According to the Socioemotional Selectivity Theory, older adults select their goals to be more emotion-related, opposed to knowledge-related (Carstensen, Citation2006). The motive to contribute meaningfully is specific to the developmental stage of middle-aged and older adults, a motive commonly referred to as generativity (Erikson, Citation1982). Generativity can be realised through a diverse range of activities, including volunteering, caregiving, and sharing life advice (Grossman & Gruenewald, Citation2017; Moieni et al., Citation2021). Given the importance of meaningful engagement and the various motives to provide care in the second half of life, it lies at hand that fulfilling generativity through these activities may have positive outcomes for psychological well-being. Indeed, a recent study showed that a generativity intervention reduced older women’s loneliness (Moieni et al., Citation2021). Likewise, when older people cannot fulfil their motive to engage in meaningful activities (e.g. due to impaired health), this unfulfilled motive may lead to increased loneliness (Smith, Citation2012). The pathways between meaningful contributions and loneliness can be better understood by looking at the conceptual definition of loneliness, described as the discrepancy between the expected and actual social relationships (Peplau & Perlman, Citation1982). Analogously, according to the Social Relationship Expectations Framework, if the age-specific expectation of generativity cannot be met, people may perceive a gap between their expectations and reality, and consequently, feel lonely (Akhter-Khan et al., Citation2022).

In this study, we focus on contributions of people in midlife and older age that are informal and unpaid, and thus, not sufficiently valued and accounted for in economic indices (Akhter-Khan, Citation2021; Sun, Citation2013). These activities provided by adults over 50 years old, that accounted for £226 billion in one year in the UK alone (Iparraguirre, Citation2017), have previously been described as unpaid productive activities and include caregiving, grandparenting, and volunteering (Grünwald et al., Citation2021). Caring, as defined by Fisher and Tronto (Citation1990), is an ‘activity that includes everything that we do to maintain, continue, and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible’ (p. 40). In the present study, we operationalise caregiving as any informal activity that includes helping with (independent) activities of daily living ((I)ADL), providing emotional and functional support, as well as (grand)childcare. Volunteering encompasses any number of hours of volunteer engagement in the past year, such as (but not limited to) environmental, educational, or religious organisations and informal activities. Both volunteering and caregiving (to spouse, grandchildren, and others) have been shown to promote and fulfil generativity through meaningful engagement (Grossman & Gruenewald, Citation2017; Gruenewald et al., Citation2016; Moieni et al., Citation2021; Rubinstein et al., Citation2015).

To date, the association between meaningful contributions and loneliness in midlife and older age remains unclear. While unpaid productive activities may have an underlying commonality (i.e. targeting generativity), there may be differences regarding the diverse social and opportunity contexts that may affect loneliness in different ways. For example, caring for a spouse may be an isolating experience with limited opportunities for social engagement and intergenerational contact (Greenwood et al., Citation2019; Milligan & Morbey, Citation2016), whereas caring for grandchildren or volunteering may lead to an increased social network and more diverse daily activities (Onyx & Warburton, Citation2003; Quirke et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, differences in age and gender may be important mediators in the association between unpaid productive activities and loneliness. For centuries, older women have played an evolutionary important role as care providers, which anthropologists regard as essential for human survival (Hawkes, Citation2003; Hrdy & & others, Citation2009). Today, the cultural expectation to provide grandparental care may still be stronger for women than for men, and therefore, the fulfilment of the expectation may have gendered effects on reducing loneliness (Quirke et al., Citation2021). Additionally, the negative effects of caregiving in the absence of sufficient support (e.g., loneliness, social isolation, exercise habits, and alcohol consumption) may be particularly pronounced for caregivers in midlife (Ysseldyk et al., Citation2019), whereas the situation may be different for older people. Older adults not only have the skills and knowledge that midlife adults have; they also often have more time during retirement.

The different contexts associated with various unpaid productive activities may partly explain why caregiving has been previously associated with both adverse as well as positive physical and psychological health outcomes. On the one hand, caregiving has been associated with adverse effects on the care providers’ well-being. For instance, cancer caregivers experience loneliness and hopelessness, lower self-efficacy, and a withdrawal from social engagement (Gray et al., Citation2020). Intense caregiving activities can also lead to a caregiving burden among care providers. Common risk factors for experiencing a caregiving burden include being a woman, co-residence with the care recipient, higher caregiving intensity, financial insecurity, and lack of choice of being a caregiver (Adelman et al., Citation2014). On the other hand, by contributing meaningfully, older adults may not only meet their age-specific expectation for generativity, but also feel important, valued, and have more opportunities to be integrated in society and lead an active lifestyle. Indeed, longitudinal studies reveal better health status (Di Gessa et al., Citation2016), psychological outcomes (Jongenelis et al., Citation2022), and decreased mortality rates (Hilbrand et al., Citation2017; O’Reilly, Rosato, Ferry, et al., Citation2017; O’Reilly, Rosato, Moriarty, et al., Citation2017) among volunteers and caregivers, compared to non-contributing older adults.

Given the conflicting findings in the literature on the association between loneliness and generativity-promoting activities, as well as the pressing need to find solutions to prevent and reduce loneliness, this systematic review addresses the potential protective role of people’s unpaid productive activities for loneliness. Specifically, the objective of this systematic review is to assess the global evidence base of the links between people’s different caregiving types (e.g., spousal and grandparental caregiving) and volunteering with their levels of loneliness in midlife and older age. Addressing this gap may help to identify new opportunities for older people to realise generativity (e.g., by promoting volunteer engagement) and at the same time reduce loneliness (e.g., by valuing and supporting older caregivers).

Materials and methods

This review was written in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 statement (Page et al., Citation2021; Supplementary Table S2) and registered in PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews; protocol number: CRD42021267912).

Search strategy and selection criteria

After initial scoping searches, the following databases were searched for peer-reviewed journal articles meeting our eligibility criteria from inception to July 2021: Ovid MEDLINE, Embase, PsychInfo and Global Health. Search terms included (loneliness) AND (older adults) AND (caregiving OR volunteering OR contributions OR grandparenting) as well as synonyms and subject headings (the complete search strategy can be found in Supplementary Text S1). Additional literature was identified by citation chaining using forward- and backward-searches. First, titles and abstracts of all articles were independently screened by two reviewers (SA and MW) using Rayyan, a free web-tool for collaborative research (Ouzzani et al., Citation2016). Then, the relevance of each full-text article was independently assessed (SA and VH). A third reviewer (MP) was consulted in the cases of disagreements.

Studies were included if they: (i) had a cross-sectional or longitudinal observational design, (ii) reported quantitative results on loneliness of participants aged 50 years and older who provided care or volunteered and (iii) compared such participants with other same-aged adults who were not involved in these activities or did not report loneliness. The age cut-off of 50 years was chosen as we were interested in potential differential effects of unpaid productive activities on loneliness in midlife versus older age. Loneliness was defined as the self-reported subjective discrepancy between desired and actual social relationships, which is distinct from objective social isolation (Peplau & Perlman, Citation1982). Self-reported items and validated scales measuring loneliness were included. There was no restriction on the recipient of the care provision (e.g., care recipients who had an illness, were family-members, or non-kin) or the type of volunteering activity (e.g., at religious, educational, health-related, or other charitable organizations). Providing financial support was not regarded as caregiving. Studies were included if the setting was community-based or in long-term care (LTC). No language restriction was applied.

We excluded studies when (i) the study was not an original study published in a peer-reviewed journal, the design was not observational, or the study did not report quantitative results, (ii) the average age of participants was <50 years, or the study did not report results with stratified analyses by age, (iii) the reported outcome was objective social isolation or depression (if loneliness was not separately reported), (iv) the comparison group had low levels of caregiving or loneliness (instead of no caregiving/loneliness) and (v) the study was in a clinical setting or involved older caregivers or volunteers with an illness.

Data extraction

The data extracted from each study included the year of data collection, geographical setting, sample size, participants’ characteristics, definition and measurement of the outcome (i.e., loneliness) and the exposure (i.e., caregiving, volunteering), data collection method, statistical analyses and covariates, results (e.g., odds ratios) unadjusted and adjusted for covariates, as well as missing data. Data was extracted by the first author (SA) using Excel and cross-checked by an independent reviewer (VH).

Quality assessment

To assess risk of bias in individual studies, the Newcastle Ottawa Scale (NOS) was applied (Wells et al., Citation2014). Three versions of the NOS were used: one modified for cross-sectional studies (Herzog et al., Citation2013) and the two NOS versions for cohort and case-control studies. Because caregiving or volunteering is commonly measured as self-report, studies were awarded one star on all scale versions for ‘ascertainment of exposure’. For loneliness, validated scales (including modifications) and single items were awarded one star; no star was given for other assessments. This adapts the cross-sectional version to have the same stars per category as the other versions. Two reviewers (SA and VH) independently assessed the quality of each included study and then compared and discussed the assessments with a third reviewer (MP).

Synthesis of results

Study findings were summarised in a narrative synthesis. All adjusted and unadjusted associations between unpaid productive activities and loneliness were tabulated, indicating whether the association was significantly positive, significantly negative, or non-significant. For unadjusted associations, p-values (<0.05) are presented in the tables; for adjusted associations, standardised (ß) or unstandardised (B) regression coefficients, odds ratios (OR), or incident rate ratios (IRR) are presented. Older adults’ unpaid productive activities were classified into four categories: (i) general caregiving, (ii) caregiving to grandchild/non-kin child, (iii) caregiving to spouse and (iv) volunteering, as we were interested how the relation between caregiving, volunteering, and loneliness may differ depending on the care recipient or activity. Differences in age, gender, and time were also described.

Results

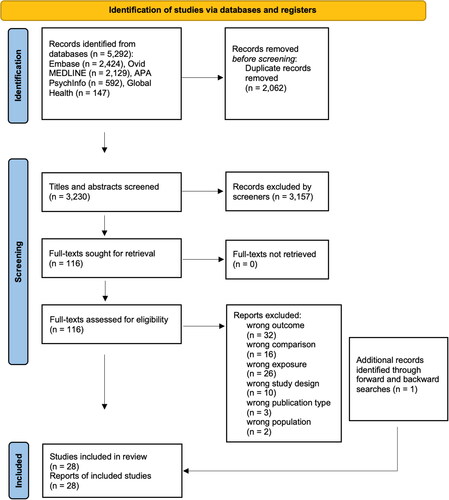

Electronic searches identified a total number of 3230 citations after duplicates were removed. Following eligibility assessment, 116 articles were selected for full-text screening. 89 studies were excluded; 32 reported an outcome other than loneliness (e.g., lonely dissatisfaction, Chang et al., Citation2020), 16 did not have a ‘no activity’ comparison group, 26 did not examine the appropriate exposure, ten had a wrong study design, two included participants with a mean age of <50 years, one was a conference abstract and two were dissertations. Additional searches from forward- and backward-chaining identified one eligible study (Lakomý, Citation2020). In sum, 28 full-text articles were included in the narrative synthesis of this review ().

Figure 1. PRISMA flow-diagram of study selection.

This figure shows a PRISMA flow diagram of included and excluded studies. Of the 5,929 articles identified by the search strategy, 2,062 duplicate records were removed, resulting in 3,230 titles and abstracts being screened by two independent reviewers. 116 full texts were assessed for inclusion, according to the eligibility criteria. In total, 27 were selected and one additional study was identified by forward- and backward-citation searches.

Across the 28 studies, there were 191,652 participants (52.5% women), with sample sizes ranging from 101 to 40,748 participants (). Baseline mean ages ranged from 54.1 to 83.6 years; across the 15 longitudinal studies, follow-up time ranged from 2 to 14 years. In the following section, as only one study reported participants with an average age of <60 years (De Jong Gierveld & Dykstra, Citation2008), we refer to all participants as older adults. The articles represent studies from 21 countries: Germany (7), the United States (7), the United Kingdom (3), the Netherlands (3), Taiwan (2), New Zealand (2), Sweden (2), Norway (2), Italy (2), Austria (2), Belgium (2), Czech Republic (2), Denmark (2), Estonia (2), France (2), Luxembourg (2), Spain (2), Switzerland (2), Slovenia (1), Ireland (1) and China (1). One study only analysed a sub-sample of men (Neville et al., Citation2018).

Table 1. Characteristics of included articles (N = 28) and study participants (N = 191,652).

Table 2. Results of articles assessing the association between loneliness and caregiving (general, grandchild, and spousal) (N = 24).

Among the 28 studies, 23 used validated scales to assess loneliness, such as the De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale (10) and the UCLA Loneliness Scale (9). Among the non-validated measures were three studies that assessed loneliness as a single item from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (Adams, Citation2008; Tsai, Citation2016; Tsai et al., Citation2013) and two studies that used other measures (Ekwall et al., Citation2004; Lakomý, Citation2020). Although a single item cannot assess different dimensions of loneliness (e.g., social versus emotional loneliness), this measure still contributes valuable information across diverse contexts (Newmyer et al., Citation2021), which is why we decided to include these studies.

Caregiving or volunteering was assessed by a single item in 19 studies and only one study used a scale (Neville et al., Citation2018). Other studies asked about the intensity of contributions (i.e., number of hours (6) and activities (2)) and one study distinguished between formal and informal volunteering (Matthews & Nazroo, Citation2021). The time periods that unpaid productive activities were assessed as ranged from weekly (5) to yearly (4). Of the 28 studies, 10 studies asked the participants whether they provided care to someone with ill health, someone with (I)ADL needs, or with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) or dementia, including five (out of seven) studies that assessed spousal caregiving.

Loneliness and caregiving

Results are presented separately for general, spousal, and grandchild caregiving () as well as stratified for age, gender, and time.

General caregiving

General caregiving referred to studies that did not define the care recipient (N = 8) or included parents and family members other than spouses and grandchildren as care recipients (N = 2) (De Jong Gierveld & Dykstra, Citation2008; Hansen et al., Citation2013). Out of ten studies that assessed general caregiving, five studies reported no significant associations with loneliness (Curvers et al., Citation2018; Fokkema & Naderi, Citation2013; Hajek & König, Citation2019; Hansen et al., Citation2013; Zwar et al., Citation2020), three studies reported negative associations (Ekwall et al., Citation2004; Lakomý, Citation2020; Smith et al., Citation2020), one study reported a positive association (Drennan et al., Citation2008), and one study reported mixed results (De Jong Gierveld & Dykstra, Citation2008). Although two studies that investigated support or care provision to parents (and in-laws) found no significant associations with loneliness (De Jong Gierveld & Dykstra, Citation2008; Hansen et al., Citation2013), providing social support to siblings was associated with lower loneliness, and providing support to adult age children was associated with higher loneliness (De Jong Gierveld & Dykstra, Citation2008). Although Smith et al. (Citation2020) reported that people who cared for someone with (I)ADL needs were 74% less likely to feel lonely at baseline, loneliness levels among caregivers increased over an eight-year period, while perceived control and autonomy both decreased over time.

Caregiving to grandchild

Caregiving to grandchildren or non-kin children was associated with lower loneliness in six out of seven studies (). Three studies reported bivariate negative associations between loneliness and grandparental caregiving (Szabó et al., Citation2021; Tang et al., Citation2016; Tsai, Citation2016). Adults aged 60 and older who were spending a weekly average of 12 h on grandparental childcare were 60% less likely to feel lonely than non-caregivers, one study found (Tang et al., Citation2016); a longitudinal study from Taiwan showed similar results (Tsai et al., Citation2013). Szabó et al. (Citation2021) found grandparental caregiving to only be associated with lower social loneliness, not emotional loneliness. Furthermore, this study showed that grandchild caregiving was more strongly linked to lower social loneliness than non-kin childcare, whereas Quirke et al. (Citation2019) reported similar effects for loneliness among grandchild versus non-kin childcare.

Caregiving to spouse

Providing care to a partner or spouse was consistently associated with higher loneliness (). Six out of seven studies included in this review reported positive associations in both unadjusted (Beeson, Citation2003; Robinson-Whelen et al., Citation2001) and adjusted analyses (Adams, Citation2008; Hansen & Slagsvold, Citation2013; Saadi et al., Citation2021; Wagner & Brandt, Citation2018). One study including eleven European countries found that taking care of a partner in the same household led to loneliness scores 0.20 higher than for non-caregivers on the three-item UCLA loneliness scale; this relationship was even stronger for areas with lower LTC service availability (Wagner & Brandt, Citation2018). The remaining studies specifically investigated caregiving to a spouse with an illness, such as AD (Adams, Citation2008; Beeson, Citation2003), dementia (Robinson-Whelen et al., Citation2001; Saadi et al., Citation2021), or other disabilities (Hansen & Slagsvold, Citation2013). Saadi et al. (Citation2021) found that loneliness partially mediated the effect from caregiving to depression when the spouse had dementia, whereas this was not the case for spouses with other conditions. Only one study did not find a significant association with loneliness in the main analysis, yet, when excluding adults who provided care to someone other than their spouse, caregiving wives experienced significantly more loneliness than non-caregiving wives (Hawkley et al., Citation2020).

Caregiving stratified by age, gender, and time

Of all included studies assessing caregiving and loneliness, only seventeen included the mean age of caregivers. On average, caregivers were 67.8 years old. Among the studies with middle aged and younger older adults (54–64), only one study reported that caregiving (to children) was associated with increased loneliness (De Jong Gierveld & Dykstra, Citation2008), while most studies showed a negative association (Fokkema & Naderi, Citation2013; Smith et al., Citation2020; Szabó et al., Citation2021) and several studies showed mixed results. Studies including adults with a higher average age (70–84) reported caregiving to be associated with higher loneliness in three studies (Adams, Citation2008; Beeson, Citation2003; Drennan et al., Citation2008) and lower loneliness in two studies (Ekwall et al., Citation2004; Tang et al., Citation2016). No study stratified the analysis for age.

Seven out of 28 studies investigated differential associations between loneliness and caregiving among women and men. In an unadjusted analysis, the average loneliness scores were significantly higher among spousal caregivers who were women, compared to men (Beeson, Citation2003). Conversely, in the adjusted analyses, three studies reported that caregiving was associated with higher loneliness only among men, not among women (Hansen & Slagsvold, Citation2013; Quirke et al., Citation2021; Zwar et al., Citation2020). Three studies reported no significant differences in loneliness between women and men (Hajek & König, Citation2019; Hansen et al., Citation2013; Hawkley et al., Citation2020).

Five studies assessed the time spent caregiving in the analysis. Fokkema and Naderi (Citation2013) found a dose-response relationship in the intensity of caregiving to grandchildren and loneliness: German and Turkish older adults living in Germany who provided care to grandchildren were less likely to feel lonely when they took care on a weekly basis, followed by monthly, and less than monthly. Moreover, Lakomý (Citation2020) found that caregiving on a weekly basis was significantly associated with lower loneliness, opposed to caregiving on a daily basis. This result is in line with a Swedish study of adults aged 75 and older (Ekwall et al., Citation2004). On the contrary, two studies did not find an association between loneliness and the time, pressure, difficulties, and duration of the caregiving activity (Robinson-Whelen et al., Citation2001; Tang et al., Citation2016). Still, caregiving burden was associated with a 10% higher rate of loneliness for grandparents (Tang et al., Citation2016).

Loneliness and volunteering

Four out of six studies reported volunteering to be associated with lower levels of loneliness (Curvers et al., Citation2018; Kim et al., Citation2020; Matthews & Nazroo, Citation2021; Yang et al., Citation2018); one study reported a significant association only among recent widowers (Carr et al., Citation2018), and one study that included only men did not reach significance (Neville et al., Citation2018; ). Matthews and Nazroo (Citation2021)—the only study to report bivariate associations—found monthly volunteering to mitigate loneliness over a two-year period. However, when controlling for demographics and socio-economic status (SES), the association only reached significance when the older adults participated in two or more activities of informal volunteering (compared to 1 activity). Similarly, two longitudinal studies only found significant associations with lower loneliness when older adults volunteered over 100 h per year (Carr et al., Citation2018; Kim et al., Citation2020). When fully adjusted, Curvers et al. (Citation2018) found that the likelihood to feel severely lonely decreased by 0.7 fold for older adults who volunteered, compared to people who did not volunteer. Yet, volunteering was not significantly associated with moderate loneliness. One study further stratified the total sample by young old (60-79 years) and old old (>80 years), finding that volunteering was only associated with lower loneliness among the young old (Yang et al., Citation2018).

Table 3. Results of articles assessing the association between loneliness and volunteering (N = 6).

Risk of bias of included studies

Of the 28 studies, two demonstrated a high risk of bias (Beeson, Citation2003; Ekwall et al., Citation2004), 4 studies a moderate (Fokkema & Naderi, Citation2013; Hansen et al., Citation2013; Hansen & Slagsvold, Citation2013; Smith et al., Citation2020), and 22 studies a low risk of bias (). Most studies controlled for essential confounders (e.g., demographics, SES, and self-reported health) and had large, representative sample sizes. However, four out of six case-control studies did not report the history of outcome and non-response rates. Similarly, half of the cohort studies did not demonstrate that the outcome was not present before baseline assessments. Approximately a third of included studies did not report the average age of participants, limiting our ability to investigate the relationship between loneliness and unpaid productive activities in different age groups.

Table 4. Detailed quality assessment of all included articles using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review assessing the associations between midlife and older adults’ caregiving, volunteering, and loneliness. Whereas other systematic reviews have assessed the evidence of informal caregiving and loneliness (Hajek et al., Citation2021), or general health and mortality outcomes of volunteering (Jenkinson et al., Citation2013), no review has focused specifically on older people’s contributions, distinguished between different types of care recipients, and their association with loneliness. Across studies, providing care to a partner with health impairments, specifically with dementia or AD, was related to higher levels of loneliness, whereas proving care to grandchildren or non-kin children as well as volunteering were associated with lower levels of loneliness. Studies that did not differentiate between care recipients showed mixed results. Given the overall high quality of included studies, results from this review can be interpreted as low risk of bias. However, although this review included studies from 21 countries, most of the studies were from higher-income contexts, with 59% from Europe. This fact limits generalising this review’s findings to global contexts.

Consistently, providing care to spouses or partners was associated with higher levels of loneliness. This finding is in line with a review assessing informal care, loneliness, and social isolation across the lifespan (Hajek et al., Citation2021). For one, spousal caregiving may be an isolating experience when there is an absence of support from other people or organisations. As loneliness is a feeling of disappointment in social relationships (Peplau & Perlman, Citation1982), loneliness may occur when the care receiving partner is not able to reciprocate this care provision, which may lead to paternalistic care dynamics. This disappointment may also be experienced with mutual friends (Milligan & Morbey, Citation2016). Moreover, the caregiving older adult may not have a choice to provide care or not and is confronted with ill health, degeneration, and death. Thus, spousal caregiving may be a preparation to transitioning into widowhood, with widowhood being one of the strongest predictors for loneliness among older adults (Cohen-Mansfield et al., Citation2016). In fact, a history of spousal caregiving has been shown to pose a challenge to psychological resilience following bereavement (Bennett et al., Citation2020).

Given that generativity is an important value to older adults (Moieni et al., Citation2021), it is not surprising that older adults feel more lonely when investing time and energy into caregiving for a partner with ill health, as opposed to caregiving for someone who is integrated in social opportunity structures that may fulfil the expectation for generativity (e.g., grandchildren). The finding that grandparenting was associated with reduced loneliness among both genders was also supported by a longitudinal study published after the inclusion period of this review (Zhang et al., Citation2022). In fact, caregiving is something that makes us fully human, argued Kleinman (Citation2009); it is a moral practice that deepens our sense of meaning in the experience of our world. Caring is often a labour of love—something that caregivers find deep enjoyment and fulfilment in performing (Fisher & Tronto, Citation1990). While caregiving for grandchildren may include some of the same time-intensive activities as caregiving for an older adult (e.g. bathing and feeding), children are integrated in a care network that usually involves parents, allo-parents, and institutions (e.g. schools) (Hrdy, Citation2009). Thus, the caregiving grandparent is likely able to share caring responsibilities with other caregivers and participate in social events. The beneficial effect of grandparental care on well-being may be even more pronounced among non-co-residing grandparents (Danielsbacka et al., Citation2022). Caregiving for grandchildren, independent of them being kin or non-kin, may stimulate older people’s brains (e.g. by active engagement in diverse activities, constant learning experiences from a younger generation) (Chang et al., Citation2020; Danielsbacka et al., Citation2022; Lee et al., Citation2021), make them feel more integrated in society, and give them opportunities to share their life experiences and feel needed (Moieni et al., Citation2020, Citation2021). Indeed, cognitive functioning has been closely associated with loneliness in a bidirectional pathway (Yin et al., Citation2019). This finding supports the promotion of loneliness interventions that focus on sustainable intergenerational programs and policies (Kuehne & Melville, Citation2014; Radford et al., Citation2018).

The stark contrast between these two realities of care—between care as a costly, burdensome activity and care as a rewarding, meaningful activity—may also be due to the ability factors identified by Fisher and Tronto (Citation1990). Caring activities depend on certain preconditions—or ability factors—such as time, material resources, knowledge, and skill (Fisher & Tronto, Citation1990). When these are lacking, caring can become an exhausting responsibility rather than a rewarding activity. This may also explain why studies that assessed general caregiving, without distinguishing between the frequency, type, or recipient of care, showed mixed results in the association with loneliness in this review.

Another important ability factor may be the health status of the caregiver. An older care provider with impaired health may feel less autonomy and perceived control, thus, feel overwhelmed. This is supported by studies reporting that perceived control and the availability of LTC services mediated the relationship between caregiving and loneliness (Smith et al., Citation2020; Wagner & Brandt, Citation2018). Factors such as perceived control, health status of caregiver, and duration of caregiving may also contribute to the stronger negative association between caregiving and loneliness among men compared to women. Despite the fact that women have longer life expectancies, they tend to spend longer periods with disability and dependency in older age, which may lead to older male caregivers caring for their spouses for longer durations (Prina et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, although women have a higher caregiving burden (Pinquart & Sorensen, Citation2006), men may be less familiar with physically demanding caregiving activities and stereotypically gendered caregiving roles, which may pose challenges to their masculinity and contribute to feelings of loneliness (Milligan & Morbey, Citation2016). Thus, older male caregivers may potentially benefit from continuing with paid employment while providing care at home (Cheng et al., Citation2021), as this arrangement would allow them to keep up two separate roles, one of which involves engagement that is valued in economic indices and in line with traditional ideas of male provision in society. Future programs will need to individually assess the caregivers’ needs to provide the optimal support and promote ageing in place.

Finally, volunteering was associated with lower loneliness across studies, with the association being stronger in recently widowed and younger older adults as well as when volunteer intensity was higher (i.e. >100 h/year). Notably, volunteering may be particularly beneficial for older adults with severe loneliness (Curvers et al., Citation2018). Yet, the only cross-sectional study that assessed volunteering among men with a 12-item scale found no significant association with loneliness (Neville et al., Citation2018), raising questions for the general validity of volunteer assessments. We identified a lack of studies investigating the effect of different types of volunteering (Jongenelis et al., Citation2022) on loneliness, as well as analysing the combined effect of volunteering and caregiving on loneliness, which has previously been shown to have beneficial effects on health and mortality outcomes (Crittenden et al., Citation2022; O’Reilly, Rosato, Ferry, et al., Citation2017). Future studies will need to examine whether the mere amount (e.g. hours per year) and persistency of volunteering, the reasons for engaging in this activity, the type of volunteering (e.g. environmental volunteering), or the level of responsibility, mastery, and decision making during these activities have the potential to reduce loneliness.

Limitations and outlook

Several factors limit drawing causal conclusions from our review. Firstly, none of the studies looked at the differential effects of spousal versus grandparental care on loneliness in the same study sample. Although studies were generally of high quality, few longitudinal studies excluded participants who were lonely prior to baseline, leaving room for reverse causality. Still, longitudinal studies that were assessed as low risk of bias and controlled for loneliness at baseline showed consistent results concerning the negative association between loneliness, grandchild caregiving, and volunteering (Kim et al., Citation2020; Matthews & Nazroo, Citation2021; Tsai et al., Citation2013). Whether loneliness reductions were clinically significant will need to be assessed in future studies using measures such as the Reliable Change Index (Jacobson et al., Citation1999). Even though articles were searched and screened by independent reviewers, and the search strategy yielded a larger number of articles than other recent reviews on loneliness and caregiving (Gray et al., Citation2020; Hajek et al., Citation2021), it is possible that we missed eligible articles. Another limitation is the heterogeneity of the operationalisation of exposure and outcome. Dichotomizing the loneliness response limits the assessment of potential differential effects of caregiving on social versus emotional loneliness. Future studies would benefit from including validated, multidimensional measures of loneliness (De Jong Gierveld & Van Tilburg, Citation2010). The intensity, frequency, duration, type of care provision, and care recipient were not assessed in all studies. Qualitative studies, which were not included in this review, investigating the needs of older caregivers as well as the barriers, opportunities, and fulfilment of engaging in meaningful activities could shed further light on the optimal ‘dose’ of volunteering and caregiving. Furthermore, all studies included in this review were conducted before Covid-19. It will be an important question for future studies to account for environmental circumstances—such as global pandemics, lockdowns, conflict settings, and climate change—when investigating the association between people’s unpaid productive activities and loneliness, and how these may differ between midlife and older adults. Finally, the wide age ranges across studies (and lack of consistent reporting of means and ranges) did not allow us to analyse differential effects of age beyond descriptive comparisons. Assessing both loneliness and unpaid productive activities longitudinally would allow future studies to determine the optimal timing of a potential intervention, ideally before loneliness becomes a chronic condition.

Author contributions

SA, MP, and RM conceptualised this systematic review. SA, VH, and MW contributed to data collection; SA, VH, and MP contributed to data interpretation. All authors had access to the data reported in this review and contributed to drafting, revising, and approving the submitted manuscript.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (30 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Leon Li (Duke University) for comments on an earlier draft of this review.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, K. B. (2008). Specific effects of caring for a spouse with dementia: Differences in depressive symptoms between caregiver and non-caregiver spouses. International Psychogeriatrics, 20(03), 508–520. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610207006278

- Adelman, R. D., Tmanova, L. L., Delgado, D., Dion, S., & Lachs, M. S. (2014). Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA, 311(10), 1052–1060. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.304

- Akhter-Khan, S. C. (2021). Providing care is self-care: Towards valuing older people’s care provision in global economies. The Gerontologist, 61(5), 631–639. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa079

- Akhter-Khan, S. C., Prina, M., Wong, G. H.-Y., Mayston, R., & Li, L. (2022). Understanding and addressing older adults’ loneliness: The Social Relationship Expectations (SRE) framework. Perspectives on Psychological Science. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916221127218

- Beeson, R. A. (2003). Loneliness and depression in spousal caregivers of those with Alzheimer’s disease versus non-caregiving spouses. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 17(3), 135–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9417(03)00057-8

- Bennett, K. M., Morselli, D., Spahni, S., & Perrig-Chiello, P. (2020). Trajectories of resilience among widows: A latent transition model. Aging & Mental Health, 24(12), 2014–2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1647129

- Carr, D. C., Kail, B. L., Matz-Costa, C., & Shavit, Y. Z. (2018). Does becoming a volunteer attenuate loneliness among recently widowed older adults? The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73(3), 501–510. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx092

- Carstensen, L. L. (1993). Motivation for social contact across the life span: A theory of socioemotional selectivity. In J. E. Jacobs (Ed.), Nebraska Symposium on Motivation, 1992: Developmental perspectives on motivation (pp. 209–254). University of Nebraska Press.

- Carstensen, L. L. (2006). The influence of a sense of time on human development. Science, 312(5782), 1913–1915. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1127488

- Chang, Y., Li, Y., & Zhang, X. (2020). Benefits of grandparental caregiving in Chinese older adults: Reduced lonely dissatisfaction as a mediator. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1719. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01719

- Cheng, G. H.-L., Chan, A., Østbye, T., & Malhotra, R. (2021). Productive engagement patterns and their association with depressive symptomatology, loneliness, and cognitive function among older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 25(2), 332–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2019.1686458

- Cohen-Mansfield, J., Hazan, H., Lerman, Y., & Shalom, V. (2016). Correlates and predictors of loneliness in older-adults: A review of quantitative results informed by qualitative insights. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(4), 557–576. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610215001532

- Crittenden, J. A., Coleman, R. L., & Butler, S. S. (2022). “It helps me find balance”: Older adult perspectives on the intersection of caregiving and volunteering. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 41(4), 291–309. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621424.2022.2034700

- Curvers, N., Pavlova, M., Hajema, K., Groot, W., & Angeli, F. (2018). Social participation among older adults (55+): Results of a survey in the region of South Limburg in the Netherlands. Health & Social Care in the Community, 26(1), e85–e93. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12480

- Danielsbacka, M., Křenková, L., & Tanskanen, A. O. (2022). Grandparenting, health, and well-being: A systematic literature review. European Journal of Ageing, 19(3), 341–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-021-00674-y

- De Jong Gierveld, J., & Dykstra, P. A. (2008). Virtue is its own reward? Support-giving in the family and loneliness in middle and old age. Ageing and Society, 28(2), 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X07006629

- De Jong Gierveld, J., & Van Tilburg, T. (2010). The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: Tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. European Journal of Ageing, 7(2), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-010-0144-6

- Di Gessa, G., Glaser, K., & Tinker, A. (2016). The impact of caring for grandchildren on the health of grandparents in Europe: A life course approach. Social Science & Medicine, 152, 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.01.041

- Drennan, J., Treacy, M., Butler, M., Byrne, A., Fealy, G., Frazer, K., & Irving, K. (2008). The experience of social and emotional loneliness among older people in Ireland. Ageing and Society, 28(8), 1113–1132. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X08007526

- Ekwall, A. K., Sivberg, B., & Hallberg, I. R. (2004). Loneliness as a predictor of quality of life among older caregivers. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03260.x

- Erikson, E. H. (1982). The life cycle completed: A review. W. W. Norton & Company.

- Fisher, B., & Tronto, J. (1990). Toward a feminist theory of caring. In E. Abel and M. Nelson (Eds.), Circles of care (pp. 35–62) State University of New York Press.

- Fokkema, T., & Naderi, R. (2013). Differences in late-life loneliness: A comparison between Turkish and native-born older adults in Germany. European Journal of Ageing, 10(4), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-013-0267-7

- Gray, T. F., Azizoddin, D. R., & Nersesian, P. V. (2020). Loneliness among cancer caregivers: A narrative review. Palliative & Supportive Care, 18(3), 359–367. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951519000804

- Greenwood, N., Pound, C., Smith, R., & Brearley, S. (2019). Experiences and support needs of older carers: A focus group study of perceptions from the voluntary and statutory sectors. Maturitas, 123, 40–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2019.02.003

- Grossman, M. R., & Gruenewald, T. L. (2017). Caregiving and perceived generativity: A positive and protective aspect of providing care? Clinical Gerontologist, 40(5), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2017.1317686

- Gruenewald, T. L., Tanner, E. K., Fried, L. P., Carlson, M. C., Xue, Q.-L., Parisi, J. M., Rebok, G. W., Yarnell, L. M., & Seeman, T. E. (2016). The Baltimore Experience Corps Trial: Enhancing generativity via intergenerational activity engagement in later life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71(4), 661–670. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbv005

- Grünwald, O., Damman, M., & Henkens, K. (2021). The differential impact of retirement on informal caregiving, volunteering, and grandparenting: Results of a 3-year panel study. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(3), 607–619. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa221

- Hajek, A., & König, H.-H. (2019). Impact of informal caregiving on loneliness and satisfaction with leisure-time activities. Findings of a population-based longitudinal study in Germany. Aging & Mental Health, 23(11), 1539–1545. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2018.1506739

- Hajek, A., Kretzler, B., & König, H.-H. (2021). Informal caregiving, loneliness and social isolation: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 12101. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182212101

- Hansen, T., & Slagsvold, B. (2013). The psychological effects of providing personal care to a partner: A multidimensional perspective. Health Psychology Research, 1(2), e25.

- Hansen, T., Slagsvold, B., & Ingebretsen, R. (2013). The strains and gains of caregiving: An examination of the effects of providing personal care to a parent on a range of indicators of psychological well-being. Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 323–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0148-z

- Hawkes, K. (2003). Grandmothers and the evolution of human longevity. American Journal of Human Biology, 15(3), 380–400. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.10156

- Hawkley, L., Zheng, B., Hedberg, E. C., Huisingh-Scheetz, M., & Waite, L. (2020). Cognitive limitations in older adults receiving care reduces well-being among spouse caregivers. Psychology and Aging, 35(1), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000406

- Herzog, R., Álvarez-Pasquin, M. J., Díaz, C., Del Barrio, J. L., Estrada, J. M., & Gil, Á. (2013). Are healthcare workers’ intentions to vaccinate related to their knowledge, beliefs and attitudes? A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 154. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-154

- Hilbrand, S., Coall, D. A., Gerstorf, D., & Hertwig, R. (2017). Caregiving within and beyond the family is associated with lower mortality for the caregiver: A prospective study. Evolution and Human Behavior, 38(3), 397–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.11.010

- Hrdy, S. B. (2009). Mothers and others: The evolutionary origins of mutual understanding. Harvard University Press.

- Iparraguirre, J. (2017). The economic contribution of older people in the United Kingdom—An update to 2017. Age UK. https://www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/activecommunities/the_economic_contribution_of_older_-people_-update_-to_-2017.pdf

- Jacobson, N. S., Roberts, L. J., Berns, S. B., & McGlinchey, J. B. (1999). Methods for defining and determining the clinical significance of treatment effects: Description, application, and alternatives. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 67(3), 300–307.

- Jenkinson, C. E., Dickens, A. P., Jones, K., Thompson-Coon, J., Taylor, R. S., Rogers, M., Bambra, C. L., Lang, I., & Richards, S. H. (2013). Is volunteering a public health intervention? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the health and survival of volunteers. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 773. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-773

- Jongenelis, M. I., Jackson, B., Warburton, J., Newton, R. U., & Pettigrew, S. (2022). Aspects of formal volunteering that contribute to favourable psychological outcomes in older adults. European Journal of Ageing, 19(1), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-021-00618-6

- Kim, E. S., Whillans, A. V., Lee, M. T., Chen, Y., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2020). Volunteering and subsequent health and well-being in older adults: An outcome-wide longitudinal approach. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 59(2), 176–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.03.004

- Kleinman, A. (2009). Caregiving: The odyssey of becoming more human. The Lancet, 373(9660), 292–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60087-8

- Kuehne, V. S., & Melville, J. (2014). The state of our art: A review of theories used in Intergenerational Program Research (2003–2014) and ways forward. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 12(4), 317–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2014.958969

- Lakomý, M. (2020). Is providing informal care a path to meaningful and satisfying ageing? European Societies, 22(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2018.1547838

- Lee, S., Charles, S. T., & Almeida, D. M. (2021). Change is good for the brain: Activity diversity and cognitive functioning across adulthood. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(6), 1036–1048. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa020

- Matthews, K., & Nazroo, J. (2021). The impact of volunteering and its characteristics on well-being after state pension age: Longitudinal evidence from The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(3), 632–641. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa146

- Milligan, C., & Morbey, H. (2016). Care, coping and identity: Older men’s experiences of spousal care-giving. Journal of Aging Studies, 38, 105–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2016.05.002

- Moieni, M., Irwin, M. R., Seeman, T. E., Robles, T. F., Lieberman, M. D., Breen, E. C., Okimoto, S., Lengacher, C., Arevalo, J. M. G., Olmstead, R., Cole, S. W., & Eisenberger, N. I. (2020). Feeling needed: Effects of a randomized generativity intervention on well-being and inflammation in older women. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 84, 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2019.11.014

- Moieni, M., Seeman, T. E., Robles, T. F., Lieberman, M. D., Okimoto, S., Lengacher, C., Irwin, M. R., & Eisenberger, N. I. (2021). Generativity and social well-being in older women: Expectations regarding aging matter. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 76(2), 289–294. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa022

- Neville, S., Adams, J., Montayre, J., Larmer, P., Garrett, N., Stephens, C., & Alpass, F. (2018). Loneliness in men 60 years and over: The association with purpose in life. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(4), 730–739. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988318758807

- Newmyer, L., Verdery, A. M., Margolis, R., & Pessin, L. (2021). Measuring older adult loneliness across countries. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 76(7), 1408–1414. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbaa109

- Onyx, J., & Warburton, J. (2003). Volunteering and health among older people: A review. Australasian Journal on Ageing, 22(2), 65–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2003.tb00468.x

- O’Reilly, D., Rosato, M., Ferry, F., Moriarty, J., & Leavy, G. (2017). Caregiving, volunteering or both? Comparing effects on health and mortality using census-based records from almost 250,000 people aged 65 and over. Age and Ageing, 46(5), 821–826. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afx017

- O’Reilly, D., Rosato, M., Moriarty, J., & Leavey, G. (2017). Volunteering and mortality risk: A partner-controlled quasi-experimental design. International Journal of Epidemiology, 46(4), 1295–1302. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyx037

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—A web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1), 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Peplau, L. A., & Perlman, D. (1982). Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research and therapy. John Wiley and Sons.

- Pinquart, M., & Sorensen, S. (2006). Gender differences in caregiver stressors, social resources, and health: An updated meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 61(1), P33–P45. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/61.1.P33

- Prina, A. M., Wu, Y.-T., Kralj, C., Acosta, D., Acosta, I., Guerra, M., Huang, Y., Jotheeswaran, A. T., Jimenez-Velazquez, I. Z., Liu, Z., Llibre Rodriguez, J. J., Salas, A., Sosa, A. L., & Prince, M. (2020). Dependence- and disability-free life expectancy across eight low- and middle-income countries: A 10/66 study. Journal of Aging and Health, 32(5-6), 401–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264319825767

- Quirke, E., König, H.-H., & Hajek, A. (2019). Association between caring for grandchildren and feelings of loneliness, social isolation and social network size: A cross-sectional study of community dwelling adults in Germany. BMJ Open, 9(12), e029605. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-029605

- Quirke, E., König, H.-H., & Hajek, A. (2021). What are the social consequences of beginning or ceasing to care for grandchildren? Evidence from an asymmetric fixed effects analysis of community dwelling adults in Germany. Aging & Mental Health, 25(5), 969–975. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1727846

- Radford, K., Gould, R., Vecchio, N., & Fitzgerald, A. (2018). Unpacking intergenerational (IG) programs for policy implications: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Intergenerational Relationships, 16(3), 302–329. https://doi.org/10.1080/15350770.2018.1477650

- Robinson-Whelen, S., Tada, Y., MacCallum, R. C., McGuire, L., & Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K. (2001). Long-term caregiving: What happens when it ends? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110(4), 573–584. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.110.4.573

- Rubinstein, R. L., Girling, L. M., de Medeiros, K., Brazda, M., & Hannum, S. (2015). Extending the framework of generativity theory through research: A qualitative study. The Gerontologist, 55(4), 548–559. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnu009

- Saadi, J. P., Carr, E., Fleischmann, M., Murray, E., Head, J., Steptoe, A., Hackett, R. A., Xue, B., & Cadar, D. (2021). The role of loneliness in the development of depressive symptoms among partnered dementia caregivers: Evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Aging. European Psychiatry, 64(1), e28. https://doi.org/10.1192/j.eurpsy.2021.20

- Smith, J. M. (2012). Toward a better understanding of loneliness in community-dwelling older adults. The Journal of Psychology, 146(3), 293–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2011.602132

- Smith, T., Saunders, A., & Heard, J. (2020). Trajectory of psychosocial measures amongst informal caregivers: Case-controlled study of 1375 informal caregivers from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Geriatrics, 5(2), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics5020026

- Sun, J. (2013). Chinese older adults taking care of grandchildren: Practices and policies for productive aging. Ageing International, 38(1), 58–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-012-9161-4

- Szabó, Á., Neely, E., & Stephens, C. (2021). The psychosocial benefits of providing non-kin childcare in older adults: A longitudinal study with older New Zealanders. Journal of Health Psychology, 26(11), 1926–1938. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105319893011

- Tang, F., Xu, L., Chi, I., & Dong, X. (2016). Psychological well-being of older Chinese-American grandparents caring for grandchildren. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 64(11), 2356–2361. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14455

- Tsai, F.-J. (2016). The maintaining and improving effect of grandchild care provision on elders’ mental health—Evidence from longitudinal study in Taiwan. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics, 64, 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.archger.2016.01.009

- Tsai, F.-J., Motamed, S., & Rougemont, A. (2013). The protective effect of taking care of grandchildren on elders’ mental health? Associations between changing patterns of intergenerational exchanges and the reduction of elders’ loneliness and depression between 1993 and 2007 in Taiwan. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 567. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-567

- Wagner, M., & Brandt, M. (2018). Long-term care provision and the well-being of spousal caregivers: An analysis of 138 European regions. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 73(4), e24–e34. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx133

- Wells, G., Shea, B., O’Connell, D., Peterson, J., Welch, V., Losos, M., & Tugwell, P. (2014). Newcastle-Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale Cohort Studies. University of Ottawa.

- Yang, F., Zhang, J., & Wang, J. (2018). Correlates of loneliness in older adults in Shanghai, China: Does age matter? BMC Geriatrics, 18(1), 300. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-018-0994-x

- Yin, J., Lassale, C., Steptoe, A., & Cadar, D. (2019). Exploring the bidirectional associations between loneliness and cognitive functioning over 10 years: The English longitudinal study of ageing. International Journal of Epidemiology, 48(6), 1937–1948. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz085

- Ysseldyk, R., Kuran, N., Powell, S., & Villeneuve, P. J. (2019). Self-reported health impacts of caregiving by age and income among participants of the Canadian 2012 General Social Survey. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, 39(5), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.39.5.01

- Zhang, J., Fokkema, T., & Arpino, B. (2022). Loneliness among Chinese older adults: The role of grandparenthood and grandparental childcare by gender. Journal of Family Issues, 43(11), 3078–3099. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X211041992

- Zwar, L., König, H.-H., & Hajek, A. (2020). Psychosocial consequences of transitioning into informal caregiving in male and female caregivers: Findings from a population-based panel study. Social Science & Medicine, 264, 113281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113281